Abstract

The effects of incubation delays on the accuracy of the QuantiFERON-TB gold in-tube assay (QFT-GIT) were measured. Compared to immediate incubation, 6- and 12-hour delays resulted in positive-to-negative reversion rates of 19% (5/26) and 22% (5/23), respectively. These findings underscore the need for standardizing QFT-GIT preanalytical practices.

TEXT

The identification and treatment of individuals with latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) is an effective strategy for the prevention of future reactivation and transmissions (13). Accurate diagnosis of infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis is particularly important in populations undergoing serial testing, such as health care workers, as false-negative results can lead to nosocomial outbreaks and false positives can result in excessive treatment (15). Since 1907, the tuberculin skin test (TST) has been the primary screening tool for diagnosis of LTBI. More recently, gamma interferon (IFN-γ) release assays (IGRAs) have been developed as attractive alternatives to TST (16). IGRAs are functional T-cell assays that measure an increase in IFN-γ release when T cells in whole blood or in peripheral blood mononuclear cells are stimulated with purified M. tuberculosis-specific antigens, such as early secretory antigen 6 (ESAT-6) and the culture filtrate protein 10 complex (CFP-10) (2). The absence of these proteins in all Mycobacterium bovis BCG strains and most environmental mycobacteria prevents nonspecific cross-reactivity (1). Other advantages of IGRAs include direct measurement of T-cell responses, absence of immune boosting, and the need for only one patient visit.

Since their conception, numerous studies have evaluated the performance of IGRAs for diagnosis of LTBI. In the absence of a gold standard for LTBI, most studies have used a surrogate for latent infection. Overall, the sensitivity of IGRAs has varied between studies; the sensitivity of IGRAs in culture-positive cases has ranged from 65% to 100% (5, 6, 14). Similarly, the sensitivity of IGRAs in patients that progressed to active tuberculosis has ranged from 51% to 100% (11). The reason for such broad interstudy variations is not fully understood, but they are attributed in part to the TB incidence of the setting under study. Another possible contributing factor includes the lack of standardized preanalytical practices, such as the time lapse between blood collection and sample processing and/or incubation of cells at 37°C. Prior studies using ELISpot and whole-blood IGRAs have shown that delays in processing and incubation of blood samples before stimulation with M. tuberculosis antigens result in a lower number of detectable IFN-producing T cells (7, 10, 20). Recently, we demonstrated in a study of 26 volunteers that a delay in incubation of up to 12 h (well within the manufacturer's maximum delay of 16 h) increased the number of indeterminate QuantiFERON-TB gold in-tube (QFT-GIT) results (12). In some cases, the delay in incubation changed the final interpretation of the test as either positive or negative. However, due to the limited number of volunteers in the initial study, we were unable to assess the full impact of incubation delay on the accuracy of QFT-GIT. In this study, we assess the effects of incubation delays on the accuracy of the test and the implications for choosing a testing procedure that will provide the most sensitive and specific diagnosis.

Between July and August of 2010, 128 health care workers were recruited and consented to participate in this study. This study was approved by the Stanford University IRB. Except for 12 subjects who were recruited for being TST and QFT-GIT positive, the volunteers were recruited consecutively during their annual screening visit to occupational health. Each volunteer was asked to complete a standardized questionnaire to assess risk factors for LTBI. The self-questionnaire collected information on age, gender, ethnicity, country of birth, countries visited for at least 6 months, BCG vaccination history, prior TST and QFT results, exposure to M. tuberculosis, chest X-ray results, and immune status. The QFT-GIT result was confirmed in the laboratory information system, and quantitative results were extracted. The demographic data and prior results are presented in Table 1. Each volunteer underwent triplicate QFT-GIT testing, with 3 sets of blood collection tubes drawn at the same time. One set was immediately incubated at 37°C. The second and third sets were held for 6 and 12 h, respectively, at room temperature before they were shaken and incubated at 37°C. All remaining downstream procedures were done in an identical way for the three QFT-GIT tests. In a randomly selected group of subjects with mitogen values of >0.5 IU/ml, plasmas from all three incubations were serially diluted in saline to determine the exact mitogen value. Differences in means were compared using the Student t test. The agreement of results obtained with different incubation delays was measured with Cohen's kappa coefficient.

Table 1.

Demographic data and LTBI risk factors for the study volunteers

| Parametera | No. (%) of volunteers |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 44 (34) |

| Female | 84 (66) |

| Age | 39 ± 12b |

| Ethnicity | |

| White | 72 (56) |

| Asian | 22 (17) |

| Black | 6 (5) |

| Pacific Islander | 19 (15) |

| Indian | 8 (6) |

| NA | 1 (1) |

| Place of birth | |

| USA | 24 (19) |

| Foreign country | 104 (81) |

| TST result | |

| Negative | 85 (66) |

| Positive | 39 (31) |

| NA | 4 (3) |

| QFT-GIT result | |

| Negative | 89 (69) |

| Positive | 37 (29) |

| NA | 2 (2) |

NA, data not available.

Value for age (in years) is mean ± standard deviation.

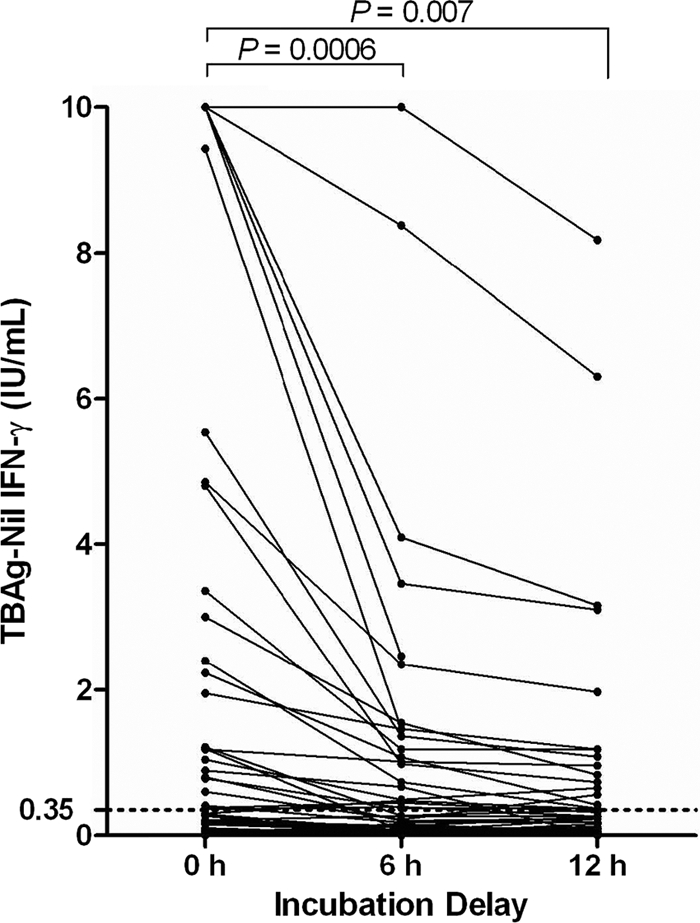

Results were available for 126/128 volunteers with all three times of incubation. In two subjects, the 12-hour-delay results were excluded from the analysis due to overincubation of the tubes at 37°C. Overall, significant declines in tuberculosis antigen (TB Ag)-nil values were observed after 6- and 12-hour delays (Fig. 1). On average, the IFN-γ concentration declined from 0.77 IU/ml with immediate incubation to 0.35 IU/ml with the 6-hour delay (P = 0.0006) and 0.19 IU/ml with the 12-hour delay (P = 0.007).

Fig. 1.

QFT-GIT TB Ag-nil values for 128 volunteers tested with immediate and delayed incubations. The cutoff for positive results (TB Ag-nil value of ≥0.35 IU/ml) is marked with a dashed line. TB Ag-nil values of <0 IU/ml are shown as 0 IU/ml. Two 12-hour-delay results were excluded due to overincubation. The Student t test was used to compare differences in means.

To determine the effects of incubation delays on the accuracy of QFT-GIT results, the quantitative results obtained with immediate and delayed incubations were interpreted using the assay cutoff provided by the manufacturer. Overall, 102 (80%) volunteers tested negative with all three incubations and 26 (20%) volunteers tested positive with one or more incubation delays. One volunteer had an indeterminate result with the 12-hour delay. Ten volunteers (8%) with negative results had a history of positive QFT-GIT result and thus represented reversions. In 93% (119/128) of volunteers, the qualitative results remained congruent between immediate and delayed incubations (kappa = 0.75). The agreement was 95% (122/128) between immediate incubation and the 6-hour delay (kappa = 0.84), 94% (119/126) between immediate incubation and the 12-hour delay (kappa = 0.8), and 95% (120/126) between the 6- and 12-hour delays (kappa = 0.81) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of QFT-GIT results for immediate and delayed incubations

| Result with 0-h delay | No. with result after: |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6-h delay |

12-h delay |

|||||

| Positive | Negative | IDTa | Positive | Negative | IDT | |

| Pos | 20 | 5 | 0 | 17 | 5 | 1 |

| Neg | 1 | 102 | 0 | 1 | 102 | 0 |

IDT, indeterminate.

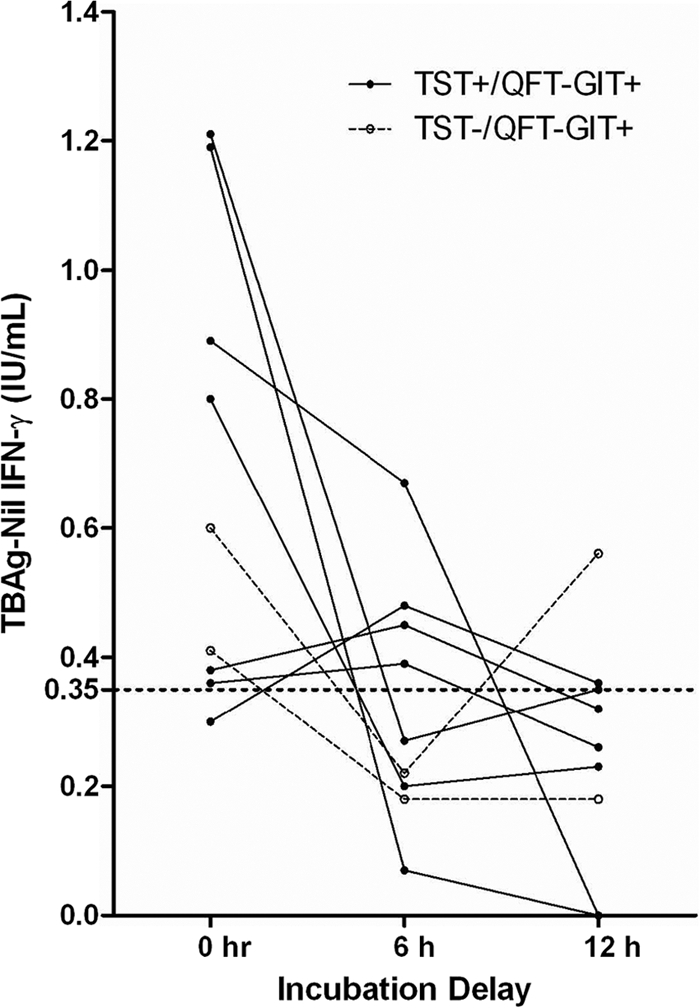

Altogether, 9 individuals yielded discrepant results with different incubation delays. The qualitative and quantitative results for subjects with discrepancies are shown in Table 3 and Fig. 2, respectively. Six discrepancies occurred between immediate incubation and the 6-hour delay, and 7 discrepancies occurred between immediate incubation and the 12-hour delay (Table 3). Excluding the one indeterminate result with the 12-hour delay, with both the 6- and 12-hour delay, 5/6 (83%) discrepancies were due to reversion from positive to negative results. This resulted in overall positive-to-negative reversion rates of 19% (5/26) and 22% (5/23) with the 6- and 12-hour delay, respectively. The LTBI risk factors of the 9 individuals with discrepant results are shown in Table 3. All but one individual had risk factors for exposure to M. tuberculosis. The volunteer without an exposure history had two prior positive QFT-GIT results with TB Ag-nil values of 2.25 and 1.43 IU/ml, respectively.

Table 3.

Risk factors for latent tuberculosis infection in volunteers with discrepant results between immediate and delayed incubation

| Volunteer identification code (0-, 6-, 12-h result)a | Country of birth | TB exposure | Prior TSTb | Prior QFT-GIT | Chest X-ray |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 003 (pos/neg/neg) | USA | Pos | Neg | Pos | Neg |

| 008 (pos/pos/neg) | Philippines | Neg | Pos | Pos | Neg |

| 090 (pos/neg/pos) | Mexico | Pos | Pos | Pos | Neg |

| 093 (pos/pos/neg) | Philippines | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos |

| 103 (pos/neg/pos) | USA | Neg | Neg | Pos | Neg |

| 106 (neg/pos/pos) | Philippines | Pos | Pos | Pos | Neg |

| 122 (pos/pos/neg) | Philippines | Neg | Pos | Pos | Neg |

| 132 (pos/neg/IDT) | China | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos |

| 134 (pos/neg/neg) | Hungary | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos |

Pos, positive; neg, negative; IDT, indeterminate.

TST cutoff, ≥10 mm.

Fig. 2.

QFT-GIT TB Ag-nil values for 9 volunteers with discordant results between immediate and delayed incubations. The cutoff for positive results (TB Ag-nil value of ≥0.35 IU/ml) is marked with a dashed line. TB Ag-nil values of <0 IU/ml are shown as 0 IU/ml. Prior TST and QFT-GIT results are shown.

Since reversion and conversions are more likely to occur when the TB Ag-nil value is close to the assay cutoff (18), the TB Ag-nil values for the group with discrepant results between immediate and delayed incubations was compared to the values for the group with congruent results. The mean TB Ag-nil concentrations were 5.3 and 0.68 IU/ml (P = 0.01) for the congruent and discrepant groups, respectively, with immediate incubation, 2.5 and 0.33 IU/ml (P = 0.03), respectively, with the 6-hour delay, and 2.0 and −0.57 IU/ml (P = 0.02), respectively, with the 12-hour delay.

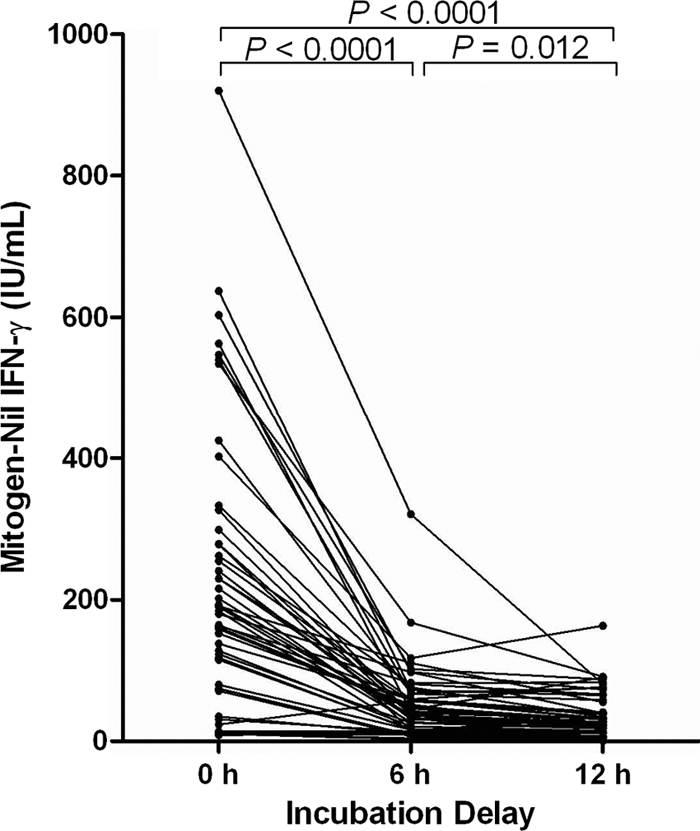

To determine the effect of incubation delay on the mitogen value, plasma from 55 randomly selected subjects was serially diluted (when necessary) and values were compared. There was an overall decline in mitogen-nil values with delayed incubation (Fig. 3). The mean mitogen-nil value declined significantly, from 210.1 IU/ml with immediate incubation to 47.3 IU/ml with the 6-hour delay (P < 0.0001) and 34.2 IU/ml with the 12-hour delay (P < 0.0001). The mitogen-nil value also declined significantly between the 6-hour and the 12-hour delay (P = 0.01). The incubation delay resulted in one indeterminate result in a subject tested with the 12-hour incubation delay.

Fig. 3.

QFT-GIT mitogen-nil values for volunteers tested with immediate and delayed incubations. The Student t test was used to compare differences in means.

Our results demonstrate a consistent and significant decline in IFN-γ levels when 37°C incubation of QFT-GIT blood samples is delayed by 6 or 12 h. These findings are consistent with previous studies showing that a delay of 1 to 4 h in processing and incubation of blood samples resulted in a significantly lower number of IFN-γ-producing cells (7, 10, 20). In our study, the decline in the TB Ag-nil value with 6- and 12-hour incubation delays resulted in positive-to-negative reversions in 19% (5/36) and 21% (5/23), respectively, of individuals with positive QFT-GIT results. All of the subjects with reversions had risk factors for LTBI and, therefore, negative results with incubation delay likely represented false-negative results. Compared to subjects whose results remained positive with incubation delay, the individuals with discrepancies demonstrated a significantly lower mean TB Ag-nil value. Thus, the delay in incubation caused lowering of the TB Ag-nil values in all subjects but was more likely to cause a false reversion when the quantitative result was close to the assay cutoff of 0.35 IU/ml.

Reversions and conversions of IGRA results have been reported in 12% to 50% of cohorts undergoing serial testing (4, 9, 17). Reproducibility of IGRAs is particularly important in populations undergoing serialized testing, such as health care workers. The occurrence of conversion and reversion in the absence of M. tuberculosis exposure or therapy, respectively, poses a major challenge to the medical practitioner and the patient. Our findings suggest that nonstandardized time-to-incubation practices could represent an important contributing factor in the reversions and conversions observed in prior studies.

Furthermore, the sensitivity of an IGRA is critical for accurate identification and treatment of individuals exposed to M. tuberculosis. There is substantial heterogeneity in the reported sensitivities of IGRAs for the diagnosis of active or latent tuberculosis (5, 6, 14). Our findings suggest that differences in incubation delay could also be contributing to disparities in the sensitivities observed with various studies. Prospective studies in patients with culture-positive TB and longitudinal contact investigation studies are needed to determine whether immediate incubation could increase the sensitivity of QFT-GIT. The benefit of immediate incubation may be particularly important in children and adults with immature and compromised immune systems, respectively, where IGRAs have yielded the lowest sensitivities (3).

In this study we demonstrated that immediate incubation of QFT-GIT tubes is essential for detecting T-cell responses in individuals with risk factors for LTBI. Immediate incubation also has a positive impact on the IFN-γ levels in the mitogen control tube and, thus, reduces indeterminate results (12, 19). Standardization of IGRA preanalytical practices is therefore critical for maximizing assay sensitivities and minimizing the rates of indeterminate results. Although the placement of incubators at the collection site is a simple solution to achieving immediate incubation, this approach may not always be feasible, particularly when blood samples have to be drawn in the field and transported to a centralized laboratory. In such settings, it may be possible to use portable incubators. The effectiveness of an electricity-free PortaTherm portable incubator for incubation of QFT-GIT whole blood samples in remote settings was recently demonstrated (8). Although the exact mechanism by which incubation delay perturbs IGRAs is not known (10), some investigators have also validated the use of a T-cell stabilizer for extended storage (up to 32 h) of blood samples at room temperature before testing with the T-SPOT.TB assay (21). Thus, for settings where immediate incubation is not an option, it may be possible to store blood samples in an appropriate preservative until they reach a laboratory with an incubator.

In summary, we show that delays in incubation of QFT-GIT blood samples cause false-negative results in a significant fraction of subjects with risk factors for LTBI. These findings have important implications for the reproducibility and accuracy of IGRAs and underscore the need for standardizing IGRA preanalytical practices.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mary Spangler and the staff at Stanford Hospital Occupational Health for assisting with recruitment of volunteers.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 June 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Behr M. A., et al. 1999. Comparative genomics of BCG vaccines by whole-genome DNA microarray. Science 284:1520–1523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Berthet F. X., Rasmussen P. B., Rosenkrands I., Andersen P., Gicquel B. 1998. A Mycobacterium tuberculosis operon encoding ESAT-6 and a novel low-molecular-mass culture filtrate protein (CFP-10). Microbiology 144:3195–3203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Connell T. G., Tebruegge M., Ritz N., Bryant P., Curtis N. 2011. The potential danger of a solely interferon-γ release assay-based approach to testing for latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in children. Thorax 66:263–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Detjen A. K., et al. 2009. Short-term reproducibility of a commercial interferon gamma release assay. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 16:1170–1175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Diel R., et al. 2011. Interferon-{gamma} release assays for the diagnosis of latent M. tuberculosis infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Respir. J. 37:88–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Diel R., Loddenkemper R., Nienhaus A. 2010. Evidence-based comparison of commercial interferon-gamma release assays for detecting active TB: a metaanalysis. Chest 137:952–968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Doherty T. M., et al. 2005. Effect of sample handling on analysis of cytokine responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis in clinical samples using ELISA, ELISPOT and quantitative PCR. J. Immunol. Methods 298:129–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dominguez M., et al. 2010. The MIT D-lab electricity-free PortaTherm incubator for remote testing with the QuantiFERON(R)-TB Gold In-Tube assay. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 14:1468–1474 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ewer K., et al. 2006. Dynamic antigen-specific T-cell responses after point-source exposure to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 174:831–839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hanekom W. A., et al. 2004. Novel application of a whole blood intracellular cytokine detection assay to quantitate specific T-cell frequency in field studies. J. Immunol. Methods 291:185–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Herrera V., Perry S., Parsonnet J., Banaei N. 2011. Clinical application and limitations of interferon-{gamma} release assays for the diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 52:1031–1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Herrera V., Yeh E., Murphy K., Parsonnet J., Banaei N. 2010. Immediate incubation reduces indeterminate results for QuantiFERON-TB Gold in-tube assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48:2672–2676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Maartens G., Wilkinson R. J. 2007. Tuberculosis. Lancet 370:2030–2043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mazurek G. H., et al. 2010. Updated guidelines for using interferon gamma release assays to detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection—United States, 2010. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 59(RR-5):1–25 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Menzies D., Joshi R., Pai M. 2007. Risk of tuberculosis infection and disease associated with work in health care settings. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 11:593–605 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Menzies D., Pai M., Comstock G. 2007. Meta-analysis: new tests for the diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection: areas of uncertainty and recommendations for research. Ann. Intern. Med. 146:340–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pai M., et al. 2009. T-cell assay conversions and reversions among household contacts of tuberculosis patients in rural India. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 13:84–92 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Perry S., et al. 2008. Reproducibility of QuantiFERON-TB gold in-tube assay. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 15:425–432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shanaube K., et al. 2010. Intra-assay reliability and robustness of QuantiFERON(R)-TB Gold In-Tube test in Zambia. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 14:828–833 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Smith S. G., et al. 2009. Identification of major factors influencing ELISpot-based monitoring of cellular responses to antigens from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS One 4:e7972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang S. H., et al. 2010. Evaluation of a modified interferon-gamma release assay for the diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection in adult and paediatric populations that enables delayed processing. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 42:845–850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]