Abstract

Photosynthesis is the biological process that converts solar energy to biomass, bio-products, and biofuel. It is the only major natural solar energy storage mechanism on Earth. To satisfy the increased demand for sustainable energy sources and identify the mechanism of photosynthetic carbon assimilation, which is one of the bottlenecks in photosynthesis, it is essential to understand the process of solar energy storage and associated carbon metabolism in photosynthetic organisms. Researchers have employed physiological studies, microbiological chemistry, enzyme assays, genome sequencing, transcriptomics, and 13C-based metabolomics/fluxomics to investigate central carbon metabolism and enzymes that operate in phototrophs. In this report, we review diverse CO2 assimilation pathways, acetate assimilation, carbohydrate catabolism, the tricarboxylic acid cycle and some key, and/or unconventional enzymes in central carbon metabolism of phototrophic microorganisms. We also discuss the reducing equivalent flow during photoautotrophic and photoheterotrophic growth, evolutionary links in the central carbon metabolic network, and correlations between photosynthetic and non-photosynthetic organisms. Considering the metabolic versatility in these fascinating and diverse photosynthetic bacteria, many essential questions in their central carbon metabolism still remain to be addressed.

Keywords: acetate assimilation, autotrophic and anaplerotic CO2 assimilation, biomass and biofuel, 13C-based metabolomics, citrate metabolism, photosynthesis, unconventional pathways and enzymes

Introduction

Phototrophic bacteria use light as the energy source to produce phosphate bond energy (ATP) and reductants [e.g., NAD(P)H and reduced ferredoxin] through photosynthetic electron transport. Oxygenic phototrophic bacteria, known as cyanobacteria, share similar electron transport pathways with other oxygenic phototrophs (e.g., plants and algae). Photosynthetic electron transport in cyanobacteria proceeds from oxidation of H2O in the oxygen evolving complex of Photosystem II (or H2O: plastoquinone oxidoreductase) through the cytochrome b6f complex to NADP+ in Photosystem I (plastocyanin: ferredoxin oxidoreductase; Blankenship, 2002). This non-cyclic electron transport is represented in the Z-scheme of photosynthesis. A cyclic electron transport pathway also operates in oxygenic phototrophs during phototrophic growth and synthesizes ATP instead of NADPH (Iwai et al., 2010). Photosynthetic electron transport pathways are different in anoxygenic (non-oxygen evolving) phototrophs, all of which contain either a type II (quinone type) or a type I (Fe-S type) reaction center (RC). Five out of six phyla of photosynthetic bacteria are anoxygenic phototrophs: proteobacteria [anaerobic anoxygenic phototrophic Proteobacteria (AnAPs) and aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic Proteobacteria (AAPs)], green sulfur bacteria (GSBs), filamentous anoxygenic phototrophs (FAPs; or green non-sulfur/gliding bacteria), heliobacteria, and the recently discovered chloroacidobacteria (Blankenship, 2002; Bryant and Frigaard, 2006; Bryant et al., 2007). AAPs, AnAPs, and FAPs contain a type II RC, and GSBs, heliobacteria and chloroacidobacteria have a type I RC. Bacteria with a type II RC operate cyclic electron transport to generate ATP and reverse electron transport to produce NAD(P)H. GSBs operate both cyclic and non-cyclic electron transport to make NAD(P)H and ATP, and heliobacteria have been suggested to employ cyclic electron transport (Kramer et al., 1997).

The energy and reducing equivalents generated from light-induced electron transport drive diverse carbon metabolic pathways for producing cellular material, bioactive products and biofuel. Additionally, numerous photosynthetic bacteria play essential roles in global carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur cycles, as many of them are known to assimilate nitrogen and/or oxidize sulfide in conjunction with their central carbon and energy metabolisms. Inorganic and organic carbon sources are used for building cellular building blocks of photoautotrophic and photoheterotrophic bacteria, respectively. Cyanobacteria, AnAPs, FAPs, and GSBs can grow autotrophically via a variety of autotrophic CO2 assimilation pathways, while AAPs and heliobacteria are obligate photoheterotrophs. AAPs have been discovered in some ocean surface waters (Kolber et al., 2001) and certain (extreme) ecosystems (Yurkov and Csotonyi, 2009), and may play important roles in global carbon regulation (Kolber et al., 2001). Heliobacteria are the most recently discovered anaerobic anoxygenic phototrophs. Compared to other phototrophic bacteria, heliobacteria have the simplest photosystem (Heinnickel and Golbeck, 2007; Sattley and Blankenship, 2010) and some unique features: they are the only Gram-positive phototrophic bacteria in the bacterial phylum Firmicutes (and form heat resistant endospores), and are the only obligate anaerobic photoheterotrophs. All known heliobacteria are active nitrogen fixers and hydrogen producers (Madigan, 2006).

The evolution of eukaryotes has been suggested to have occurred through endosymbiosis (Margulis, 1968; Doolittle, 1998). It has been proposed that the ancestral eukaryotes were anaerobes, and that aerobic α-Proteobacteria, which include many AAPs, were the origins of mitochondria of eukaryotes and cyanobacteria were the forerunners of the chloroplast of higher plant cells (Margulis, 1968; Hohmann-Marriott and Blankenship, 2011).

While photosynthetic bacteria have simplified, and sometimes unique, photosystems compared to higher plants and green algae (Blankenship, 2002), their carbon metabolism pathways are rather complex (Figure 1). Previous studies on central carbon metabolism of photosynthetic organisms have suggested that some phototrophic and non-phototrophic organisms use some distinct carbon assimilation and carbon metabolic pathways (Hugler et al., 2011). In this report, we review the studies of key central carbon metabolic pathways, including CO2 and acetate assimilations, carbohydrate catabolism and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, and also highlight several essential and/or unconventional enzymes contributing to the critical metabolic pathways in phototrophic bacteria. Some related metabolic pathways and enzymes distributed in non-phototrophic organisms are also discussed. General approaches to investigate the carbon metabolism of phototrophs are presented in Appendix and Table A1 for readers who are interested in further information. Overall, experimental evidence indicates that phototrophic bacteria containing the same type of RC often have distinct central carbon metabolism pathways, suggesting horizontal/lateral gene transfers and late adaptation during the evolution of photosynthesis.

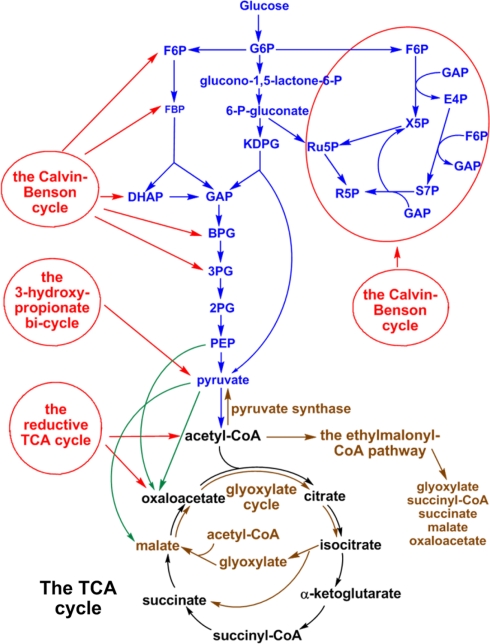

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of central carbon metabolism in phototrophic bacteria. The metabolic pathways of autotrophic CO2 fixation (red lines), anaplerotic CO2 assimilation (green lines), carbohydrate metabolism (blue lines), acetate assimilation (brown lines), and the TCA cycle (black lines) in phototrophic bacteria are shown. Some metabolic pathways are employed only in phototrophic bacteria, and others are distributed in phototrophic and non-phototrophic microbes.

Results and Discussions

Overview: The light and dark reactions in phototrophic bacteria

No two phyla of phototrophic bacteria have the same metabolic pathways, while some ecological and metabolic features of phototrophic bacteria are correlated with the type of RC employed. Only the five most characterized phyla of phototrophic bacteria are discussed here. Bacteria with a type II (quinone type) RC (e.g., Proteobacteria and FAPs) are facultative phototrophs (can grow with or without light) and are metabolically versatile (can grow aerobically and anaerobically). Since various types of quinone molecules in the type II RC can freely transport electrons in the membrane, several type II RC bacteria have an active TCA cycle and can perform respiration. Some ancient aerobic α-Proteobacteria may have been the ancestors of the mitochondria of modern eukaryotes (Margulis, 1968; Doolittle, 1998).

Bacteria with only a type I (Fe-S type) RC (e.g., GSBs and heliobacteria) are strict anaerobes and metabolic specialists. GSBs direct these reducing equivalents through light-induced electron transport to the reductive (reverse) TCA (RTCA) cycle, which is basically the reversal of the oxidative (forward) TCA (OTCA) cycle, for fixing CO2 and producing biomass (Evans et al., 1966a). Heliobacteria have an incomplete RTCA cycle, and can utilize a limited set of carbon sources. Reduced ferredoxins that are electron donors to pyruvate synthase and α-ketoglutarate synthase in the RTCA cycle are oxygen-sensitive, which may correlate with GSBs and heliobacteria being strict anaerobes.

Most cyanobacteria utilize the Calvin–Benson cycle for autotrophic CO2 assimilation and can grow photoautotrophically, photomixotrophically, and/or photoheterotrophically. Fermentative growth of cyanobacteria with carbohydrates has also been reported (Stal and Moezelaar, 1997). One group of nitrogen-fixing marine cyanobacteria, which do not have Photosystem II, autotrophic carbon assimilation pathways and the TCA cycle, are suggested to be obligate photoheterotrophs (Zehr et al., 2008; Tripp et al., 2010). Anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria are either photoautotrophs or photoheterotrophs. Anoxygenic photoautotrophs operate at least three different autotrophic CO2 fixation pathways, including the Calvin–Benson cycle. As molecular oxygen is a substrate for RuBisCO (ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase) that competes with CO2 in the Calvin–Benson cycle, giving rise to photorespiration. Oxygenic phototrophs contain CO2 concentrating mechanisms and carboxysomes to elevate CO2 concentration at the RuBisCO active site (Kaplan and Reinhold, 1999). Note that some chemolithoautotrophs, such as Thiomicrospira crunogena (Dobrinski et al., 2005) and Thiobacillus neopolitanus (Holthuijzen et al., 1986), contain carboxysomes and appear to employ a carbon concentrating mechanism, so that these adaptations are not exclusively by phototrophic organisms. No such mechanisms have been identified in anoxygenic phototrophs. In response to the intrinsic problem of RuBisCO and carbon fixation via the Calvin–Benson cycle, most anoxygenic bacteria may have either retreated to low oxygen environments and/or adopted different CO2 assimilation pathways (autotrophic or anaplerotic) and various carboxylases for carbon metabolism. Thus, various autotrophic CO2 fixation cycles, as well as some unconventional carbon metabolic pathways, operating in anoxygenic phototrophs are possibly correlated with their special ecological niches, such as high sulfide and low oxygen environments.

Central carbon metabolism pathways

Figure 1 presents a general scheme of central carbon metabolism pathways, including CO2 and acetate assimilation pathways, carbohydrate metabolism and the TCA cycle. Detailed information for each metabolic pathway in five phyla of phototrophic bacteria [e.g., the Proteobacteria (AnAPs and AAPs), GSBs, FAPs, cyanobacteria, and heliobacteria] is elaborated below.

Autotrophic CO2 fixation pathways

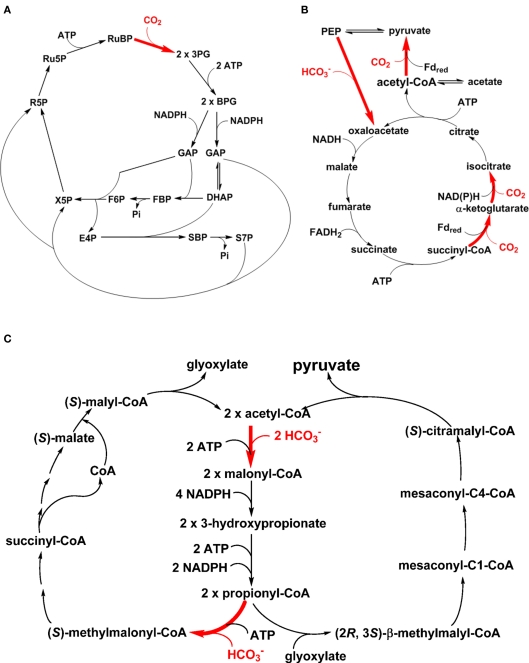

One of the landmarks of photosynthesis is assimilating CO2 autotrophically into cellular material with light, and the most well-known CO2 assimilation pathway is the reductive pentose phosphate (PP) pathway (the Calvin–Benson cycle; Figure 2A; Calvin and Benson, 1948; Bassham et al., 1950; Calvin, 1989). Note that some chemolithoautotrophs also use the Calvin–Benson cycle for carbon fixation (Kusian and Bowien, 1997; Sorokin et al., 2007). Moreover, a complete Calvin–Benson cycle has been found in the genomes of several heterotrophic bacteria (McKinlay and Harwood, 2010), and the roles of key gene products in these bacteria remain to be investigated. In addition to the Calvin–Benson cycle, five other autotrophic carbon fixation pathways have also been identified (Ensign, 2006; Thauer, 2007; Raven, 2009; Berg et al., 2010; Hugler and Sievert, 2011), including the RTCA cycle (the Arnon–Buchanan–Evans cycle; Figure 2B), the 3-hydroxypropionate (3HOP) bi-cycle (Figure 2C), the 3-hydroxypropionate/4-hydroxybutyrate (3HOP/4HOB) cycle, the dicarboxylate/4HOB cycle, and the reductive acetyl-CoA pathway (the Wood–Ljungdahl pathway). The 3HOP/4HOB cycle (Berg et al., 2007), which is similar to the 3HOP bi-cycle and uses the same carbon assimilation enzymes (e.g., acetyl-CoA carboxylase and propionyl-CoA carboxylase), the dicarboxylate/4HOB cycle (Huber et al., 2008), and the reductive acetyl-CoA pathway (Ljungdahl, 1986; Wood, 1991) have not yet been reported in phototrophs and are not discussed further here.

Figure 2.

Autotrophic CO2 fixation pathways in phototrophic organisms. The CO2 assimilation steps in the Calvin–Benson cycle (A), reductive TCA (RTCA) cycle (B) and 3-hydroxypropionate bi-cycle (C) are shown in bold and colored red. Reactions catalyzed by PEP carboxylase (i.e., the enzyme for anaplerotic CO2 assimilation) and pyruvate synthase are included in the RTCA cycle (B). Participations or consumption of ATP and reducing equivalents are shown.

Among these autotrophic carbon fixation pathways, cyanobacteria and AnAPs use the Calvin–Benson cycle (Tabita, 1995; Blankenship, 2002). GSBs use the RTCA cycle (Evans et al., 1966a,b; Buchanan and Arnon, 1990) and the FAP bacterium Chloroflexus aurantiacus utilizes the 3HOP bi-cycle (Holo, 1989; Strauss and Fuchs, 1993; Herter et al., 2002; Zarzycki et al., 2009). Several Oscillochloridaceae strains in FAPs have been reported to use the Calvin–Benson cycle, instead of the 3HOP bi-cycle, and those strains also have a branched TCA cycle (Berg et al., 2005; Table 1). The RTCA cycle is also distributed in many non-phototrophic bacteria (Hugler and Sievert, 2011), including Hydrogenobacter thermophilus (Shiba et al., 1985) and some members of the ε-Proteobacteria (Hugler et al., 2005, 2007; Takai et al., 2005). While biochemical analyses indicate that certain enzymes in the RTCA cycle are oxygen-sensitive, several autotrophic microbes (such as H. thermophilus and Aquifex aeolicus) that employ the RTCA cycle are not strict anaerobes and can grow well aerobically (Kawasumi et al., 1984; Pandelia et al., 2011). The Calvin–Benson cycle and the 3HOP bi-cycle can operate in both aerobic and anaerobic conditions, although oxygen is the substrate for RuBisCO that competes with CO2 in the Calvin–Benson cycle.

Table 1.

The carbon assimilation pathways reported in phototrophic bacteria.

| AnAPs | AAPs | FAPs | GSBs | Heliobacteria | Cyanobacteria | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUTOTROPHIC CO2 fixation pathways and anaplerotic CO2 assimilations | ||||||

| The Calvin–Benson cycle | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| The reductive TCA cycle | ✓ | ✓(incomplete) | ||||

| The 3-hydroxypropionate bi-cycle | ✓ | |||||

| Anaplerotic CO2 assimilations | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| ACETATE ASSIMILATION PATHWAYS | ||||||

| The (oxidative) glyoxylate cycle | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Pyruvate synthase | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| The ethylmalonyl-CoA pathway | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

AnAPs, anaerobic anoxygenic phototrophic Proteobacteria; AAPs, aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic Proteobacteria; FAPs, filamentous anoxygenic phototrophs; GSBs, green sulfur bacteria.

No autotrophic carbon assimilation pathways have been reported in AAPs (Yurkov and Beatty, 1998; Fuchs et al., 2007; Swingley et al., 2007), heliobacteria (Madigan, 2006), and the genus Roseiflexus in FAPs (Hanada et al., 2002). The genus Roseiflexus in FAPs has been suggested to be photoheterotrophic and not photoautotrophic (Hanada et al., 2002), although genes encoding the 3HOP bi-cycle have been found in the genome (Klatt et al., 2007). Further, preliminary studies indicate that the most recently identified photosynthetic bacterium Candidatus Chloracidobacterium (Cab.) thermophilum (Bryant et al., 2007), which is a member of the sixth photosynthetic bacteria phylum the Acidobacteria, is perhaps also a photoheterotroph, due to the lack of evidence supporting autotrophic carbon assimilation and growth.

Many metabolites, intermediates or products produced by these autotrophic carbon fixation pathways are essential for building cellular material. The Calvin–Benson cycle synthesizes 3-phosphoglycerate (3PG) and sugar phosphates (including triose-, tetrose-, pentose-, hexose-, and heptose phosphates), and all of the other autotrophic carbon fixation pathways produce or regenerate acetyl-CoA, and several of them also generate pyruvate, phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP), oxaloacetate (OAA), glyoxylate, succinyl-CoA, and/or α-ketoglutarate (Table 2). All of these metabolites are essential for the central carbon metabolism of microorganisms.

Table 2.

Metabolites generated from CO2 and acetate assimilation pathways for producing cellular material in phototrophic organisms.

| Pathways | 3PG, triose and sugar phosphate | Acetyl-CoA | Pyruvate | PEP | OAA | malate | Glyoxylate | Succinyl-CoA/ succinate | α-KG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUTOTROPHIC CO2 FIXATION PATHWAYS AND ANAPLEROTIC CO2 ASSIMILATIONS | |||||||||

| The Calvin–Benson cycle | ✓ | ||||||||

| The reductive TCA cycle | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| The 3-hydroxypropionate bi-cycle | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Anaplerotic CO2 assimilations | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| ACETATE ASSIMILATION PATHWAYS | |||||||||

| The (oxidative) glyoxylate cycle | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Pyruvate synthase | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| The ethylmalonyl-CoA pathway | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

3PG, 3-phosphoglycerate; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; OAA, oxaloacetate; and α-KG, α-ketoglutarate.

Acetate assimilation

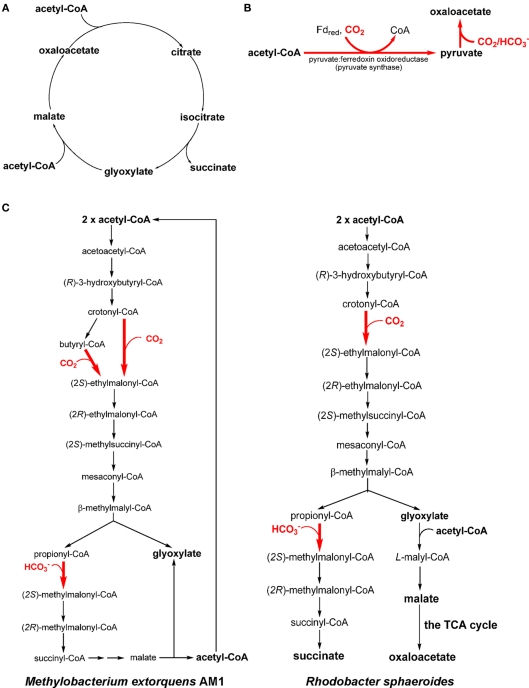

Many AAPs, AnAPs, FAPs, GSBs, and heliobacteria have been reported to grow heterotrophically or mixotrophically (in the presence of CO2) on acetate with three acetate assimilation mechanisms: the (oxidative) glyoxylate cycle (Figure 3A), pyruvate synthase (Figure 3B), and the ethylmalonyl-CoA pathway (Figure 3C). The (oxidative) glyoxylate cycle and the ethylmalonyl-CoA pathway can replenish the metabolites in the TCA cycle. Pyruvate synthase and the ethylmalonyl-CoA pathway assimilate both acetate and inorganic carbon . Distributions of the acetate assimilation pathways in phototrophic bacteria are listed in Table 1.

Figure 3.

Acetate assimilation pathways. Three acetate assimilation pathways, the (oxidative) glyoxylate cycle (A), the reaction catalyzed by pyruvate synthase (B) and the ethylmalonyl-CoA pathway (C), are shown. All of the acetate assimilation pathways may directly or indirectly synthesize oxaloacetate. The CO2 assimilation steps in the pathway/cycle are shown in bold and colored red. Different ethylmalonyl-CoA pathways have been reported in Methylobacterium extorquens AM1 [(C), left] and Rhodobacter sphaeroides [(C), right].

The (oxidative) glyoxylate cycle

The (oxidative) glyoxylate cycle, discovered more than 50 years ago by Kornberg and Krebs (1957), produces four-carbon units (malate, OAA, and succinate) by assembling two acetyl-CoA molecules (Figure 3A). It is essential not only to convert acetate, lipids and some amino acids to carbohydrates, but also to other central biosynthetic precursors in the TCA cycle (anaplerotic function). The glyoxylate cycle has also been found in plants, some (non-phototrophic) bacteria, archaea, protists, fungi, and nematodes. The glyoxylate cycle is active and has been suggested to channel excess carbon flow away from the branched TCA cycle during mixotrophic and heterotrophic, but not autotrophic, growth of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (Yang et al., 2002; Shastri and Morgan, 2005).

Some AnAPs either operate an active glyoxylate cycle (e.g., Rps. palustris; McKinlay and Harwood, 2011) or have genes in the pathway identified (e.g., Rhodospirillum centenum, Rps. palustris and Rba. capsulatus; Oda et al., 2008; Lu et al., 2010; Strnad et al., 2010), whereas other AnAPs apparently lack essential genes/enzymes in the pathway (e.g., Rubrivivax gelatinosus, Rba. Sphaeroides, and Rhodospirillum rubrum; Albers and Gottschalk, 1976; Lim et al., 2009). Genes in the glyoxylate cycle have also been identified in the genome of several FAPs (Cfl. aurantiacus, Cfl. aggregans, Chloroflexus sp. Y-400-fl, Roseiflexus castenholzii and Roseiflexus sp. RS-1; Tang et al., 2011). GSBs, AAPs, and heliobacteria do not have an active glyoxylate cycle, and use alternative acetate assimilation pathways (discussed below).

Pyruvate synthase

With no active glyoxylate cycle reported, GSBs and heliobacteria use pyruvate synthase (or pyruvate: ferredoxin oxidoreductase) for acetate assimilation. Pyruvate synthase converts acetyl-CoA to pyruvate and can assimilate both acetate (i.e., acetyl-CoA) and CO2 (Figure 3B). The catalysis requires reduced ferredoxin and thus only anaerobic anoxygenic bacteria operate pyruvate synthase. Pyruvate synthase synthesizes pyruvate from acetyl-CoA produced through acetate uptake and the RTCA cycle during mixotrophic growth of GSBs (Evans et al., 1966a; Feng et al., 2010b; Tang and Blankenship, 2010). CO2 is required for the growth of heliobacteria in the medium containing acetate as the only organic carbon source (Madigan, 2006; Tang et al., 2010b), and the supplemented CO2 is required not only for anaplerotic CO2 assimilation, but also the generation of pyruvate catalyzed by pyruvate synthase (Pickett et al., 1994; Tang et al., 2010a,b).

The ethylmalonyl-CoA pathway

The ethylmalonyl-CoA pathway is responsible for producing glyoxylate in some (chemotrophic) methylotrophs (e.g., Methylobacterium extorquens AM1; Korotkova et al., 2002; Peyraud et al., 2009; Smejkalova et al., 2010; Figure 3C, left; net reaction: acetyl-CoA + 2 CO2 → 2 glyoxylate + CoA + H+), and has also been proposed in some actinobacteria (Erb et al., 2009). The produced glyoxylate can be further converted to PEP via the serine pathway, which assimilates one carbon unit through N5, N10-methylene-tetrahydrofolate (Erb et al., 2007). The ethylmalonyl-CoA pathway has also been identified in the AnAP bacterium Rhodobacter sphaeroides (Alber et al., 2006; Erb et al., 2007) and is proposed in several AnAPs (Albers and Gottschalk, 1976; Ivanovsky et al., 1997; Alber et al., 2006; Erb et al., 2009). In contrast to the ethylmalonyl-CoA pathway reported in M. extorquens AM1, Rba. sphaeroides condenses glyoxylate with acetyl-CoA to produce malyl-CoA, which is further hydrolyzed to malate and CoA (Figure 3C, right).

Acetate can support the phototrophic and chemotrophic (in darkness) growth of several AAPs (Shiba and Simidu, 1982; Shiba and Harashima, 1986; Shiba, 1991; Yurkov et al., 1996; Koblizek et al., 2003; Biebl et al., 2005, 2006). The mechanism of acetate assimilation remains to be understood in these organisms because some AAPs do not have an active glyoxylate cycle and no AAPs have pyruvate synthase identified. Thus, acetate-grown AAPs require alternative pathways to produce OAA, which is required for producing biomass and building blocks of cells. Note that the ethylmalonyl-CoA pathway has been recently suggested to be employed by AAPs (Alber et al., 2006). It is of interest to verify if the proposed ethylmalonyl-CoA pathway is active in AAPs, and whether it plays an important role in CO2 assimilation by AAPs.

Reducing equivalent flow in photoautotrophs and photoheterotrophs

Photosynthesis generates reducing equivalents through light-induced electron transport. In photoautotrophic bacteria, channeling reducing equivalents to autotrophic CO2 fixation pathways is essential when phototrophs cannot respire. For example, GSBs are obligate photoautotrophs and cannot grow heterotrophically and in darkness. The reducing equivalents generated from photosynthetic electron transport in the type I (Fe-S type) RC of GSBs can be utilized for CO2 assimilation (via the RTCA cycle) and other types of cellular metabolism during phototrophic growth. A similar scenario can be found in chloroplasts in photosynthetic eukaryotes, NADPH produced from non-cyclic electron transport is employed for assimilating CO2 via the Calvin–Benson cycle. Alternatively, heliobacteria, the other anaerobic anoxygenic bacteria with a type I RC, do not have an autotrophic CO2 fixation mechanism. The reducing equivalents generated from their photosynthetic electron transport are utilized to reduce organic and inorganic molecules in cells, and all known heliobacterial species are active nitrogen fixers and hydrogen producers (Madigan, 2006).

In contrast to GSBs and heliobacteria, AnAPs can grow both photoautotrophically and photoheterotrophically. Unlike the wild-type, RuBisCO-, and phosphoribulokinase (PRK)-knockout Rba. sphaeroides mutants require dimethyl sulfoxide as an alternative external electron recipient to accept (excess) reducing equivalents produced during photoheterotrophic growth (Hallenbeck et al., 1990a,b; Falcone and Tabita, 1991). Also, RuBisCO-knockout Rsp. rubrum and Rba. sphaeroides can grow photoheterotrophically under nitrogen fixation conditions (Joshi and Tabita, 1996) and produce abundant H2 presumably from utilizing excess reducing equivalents. Recent metabolic flux analyses on the AnAP bacterium Rhodopseudomonas palustris also suggest that the Calvin–Benson cycle is not only assimilating CO2 and producing biomass during photoautotrophic growth, but is also accepting reducing equivalents during photoheterotrophic growth (e.g., when the Calvin–Benson cycle becomes expendable; McKinlay and Harwood, 2010). Furthermore, the choice of the pathway for assimilating organic compounds during photoheterotrophic growth is also important (Laguna et al., 2011). During photoheterotrophic growth, Rps. palustris uses reducing equivalents to produce hydrogen rather than assimilate carbon (McKinlay and Harwood, 2011) and Rba. sphaeroides directs most of the reducing equivalents to assimilate acetate using the ethylmalonyl-CoA pathway and therefore hydrogen production decreases (Laguna et al., 2011). These studies are consistent with observations that RuBisCO-knockout Rba. sphaeroides can grow photolithoautotrophically using thiosulfate or sulfide, which is not as a potent reductant as H2, as the electron source and thus consuming the excess reducing equivalents produced by photosynthesis is less essential (Wang et al., 1993), although the pathway for assimilating CO2 in these experiments is not clear. Alternative pathways for removing excess reducing equivalents are utilized by certain AAPs during photoheterotrophic growth; for example, nitrate reduction to ammonium by Roseobacter denitrificans (Shiba, 1991; Tang et al., 2009a).

Several heterocystous and non-heterocystous cyanobacteria are known to be active nitrogen fixers and hydrogen producers (Summers et al., 1995; Chen et al., 1998; Bandyopadhyay et al., 2010; Li et al., 2010). The non-heterocystous cyanobacterium Cyanothece sp. ATCC 51142, which can produce hydrogen aerobically (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2010), guides reducing equivalents to reduce nitrate to ammonium during photoheterotrophic growth with glycerol (Feng et al., 2010a).

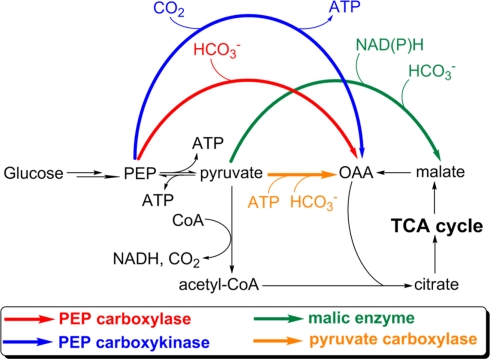

Anaplerotic CO2 assimilations

Anaplerotic reactions replenish the intermediates in a metabolic pathway. Anaplerotic CO2 assimilations are those that replenish OAA or malate for replenishing the TCA cycle, and are important to synthesize cellular building blocks. Anaplerotic CO2 assimilations cannot serve as an autotrophic CO2 fixation pathway because they require organic substrates that are not subsequently produced from the incorporation of CO2. Four enzymes catalyzing anaplerotic CO2 assimilation have been reported: pyruvate carboxylase, phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) carboxylase, PEP carboxykinase, and malic enzyme (Figure 4). Anaplerotic CO2 assimilations have been reported in all types of phototrophic bacteria. Among these, AnAPs, AAPs have an active complete OTCA cycle and can regenerate OAA, and can also replenish OAA via anaplerotic CO2 assimilations (Yurkov and Beatty, 1998; Furch et al., 2009; Tang et al., 2009a) and the glyoxylate cycle and/or the ethylmalonyl-CoA pathway (Albers and Gottschalk, 1976; Alber et al., 2006; Erb et al., 2007) to produce OAA. Alternatively, anaplerotic CO2 assimilations are essential for the growth of heliobacteria, cyanobacteria, and GSBs, all of which can only use anaplerotic CO2 assimilations to replenish OAA.

Figure 4.

Anaplerotic CO2 assimilation reactions. The CO2-anaplerotic reactions catalyzed by pyruvate carboxylase, PEP carboxylase, PEP carboxykinase, and malic enzyme are shown. Participations or consumption of ATP and reducing equivalents are presented. Abbreviation: PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; OAA, oxaloacetate.

Heliobacteria

The activity of PEP carboxykinase has been reported in heliobacteria (Pickett et al., 1994; Tang et al., 2010b). In contrast to AnAPs, AAPs, and FAPs, heliobacteria have an incomplete OTCA cycle (Tang et al., 2010a), which cannot regenerate OAA, and do not have the glyoxylate cycle and ethylmalonyl-CoA pathway (Table 1). As a result, the anaplerotic CO2 assimilation is the only approach to synthesize OAA and is essential for the growth of heliobacteria, consistent with high flux in the anaplerotic CO2 assimilation in heliobacteria (Tang et al., 2010a).

Cyanobacteria and GSBs

Active anaplerotic CO2 assimilations have been identified in GSBs (Evans et al., 1966a; Sirevag, 1995; Feng et al., 2010b; Tang and Blankenship, 2010) and cyanobacteria (Neuera and Bothe, 1983; Owttrim and Colman, 1988; Zhang et al., 2004; Stockel et al., 2011). Cyanobacteria have a branched TCA cycle (enzymes that catalyze the interconversion of α-ketoglutarate and succinate are absent) and cannot regenerate OAA (Stanier and Cohen-Bazire, 1977). An active glyoxylate cycle in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 has been reported (Yang et al., 2002; Shastri and Morgan, 2005), although key genes in the glyoxylate cycle are absent in the genomes of most cyanobacteria. GSBs require OAA to initiate the RTCA cycle and do not have the glyoxylate cycle and ethylmalonyl-CoA pathway. Although GSBs can produce OAA via ATP citrate lyase (ACL) in the RTCA cycle (see Enzymes that dissimilate citrate), OAA needs to be replenished by anaplerotic CO2 assimilations if large amounts of α-ketoglutarate and other metabolites are pulled out of the cycle for nitrogen assimilation and other cellular metabolism. As a result, cyanobacteria (if the glyoxylate cycle is absent) and GSBs can only replenish OAA through anaplerotic CO2 assimilations. It has been shown that malic enzyme is essential for optimal photoautotrophic growth of cyanobacteria (Bricker et al., 2004).

Altogether, active anaplerotic reactions are essential not only for photoheterotrophs (heliobacteria), but are also for the photoautotrophs (cyanobacteria and GSBs). Even though anaplerotic CO2 assimilations cannot support phototrophic growth in the way that the autotrophic carbon fixation pathways support photoautotrophic growth because they require pre-existing/endogenous organic compounds that are not produced by the pathway, anaplerotic CO2 assimilations are nonetheless crucial for the cell growth of phototrophic organisms.

Carbohydrate metabolism

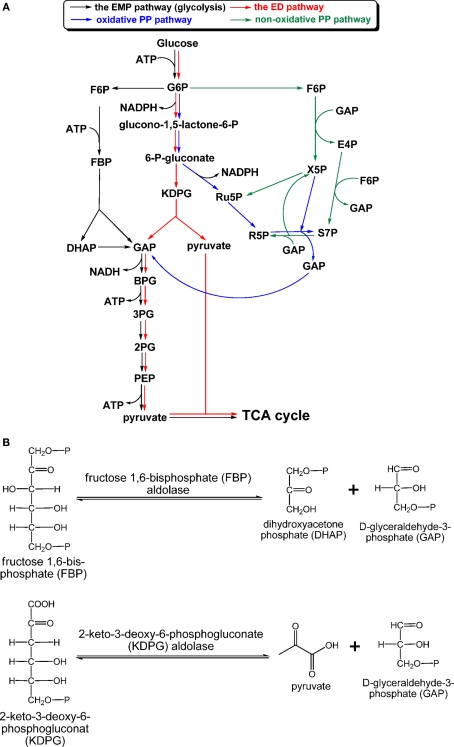

Most chemoheterotrophic organisms use carbohydrates as carbon sources to build up cellular material and provide reductants. GSBs are the only group of phototrophic bacteria that do not apparently grow on carbohydrates as sole carbon sources (Table 3). Three carbohydrate catabolic pathways in photosynthetic organisms are known: the Emden–Meyerhof–Parnas (EMP) pathway (glycolysis), Entner–Doudoroff (ED) pathway, and PP pathway (also called the phosphogluconate pathway), which includes the oxidative PP (OPP) and non-OPP pathways (Figure 5A). The EMP pathway and the ED pathway convert one molecule of glucose into two molecules of pyruvate, although different courses are employed by these two pathways. Regulation of these two pathways provides flexibility for energy generation and bypasses bottlenecks for glucose oxidation (Selig et al., 1997). For instance, glucose oxidation through the ED pathway can avoid the phosphofructokinase reaction [fructose 6-phosphate (F6P) → fructose 2,6-bisphosphate (FBP)], which is one of the irreversible and rate-determining steps in the EMP pathway (Nelson and Cox, 2008). Only the OPP pathway, not the non-OPP pathway, can produce reducing equivalents. Note that the non-OPP pathway is not the same as the reductive PP pathway (or the Calvin–Benson cycle). R5P produced via the PP pathway is a precursor for the biosynthesis of nucleic acids, ATP, histidine, and coenzymes. Net energy output and reductant production for the three glucose catabolic pathways are: 2 ATP and 2 NADH via the EMP pathway, 2 NADPH via the (oxidative) PP pathway, and 1 NADPH (the reaction that generates the first NADPH in the OPP pathway is part of the ED pathway), 1 ATP and 1 NADH via the ED pathway. Moreover, ATP can be also generated in the oxidative pentose phosphate pathway. depending on the flux mode considered (Kruger and von Schaewen, 2003).

Table 3.

The carbohydrate catabolic pathways reported in phototrophic bacteria.

| The EMP pathway | The ED pathway | The oxidative pentose phosphate pathway | The non-oxidative pentose phosphate pathwaya | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AnAPs | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ |

| AAPs | – | ✓ | – | ✓ |

| FAPs | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ |

| GSBs | – | – | – | ✓ |

| Heliobacteria | ✓ | – | – | ✓ |

| Cyanobacteria | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ |

Figure 5.

Carbohydrate catabolism. The “classical” EMP, ED, and PP pathways, which have been found in phototrophic bacteria, are shown in (A), and aldol condensation reactions catalyzed by FBP aldolase in the EMP/gluconeogenic pathway and KDPG aldolase in the ED pathway are shown in (B). Abbreviation: EMP, Emden–Meyerhof–Parnas; ED, Entner–Doudoroff; KDPG, 2-keto-3-dehydro-6-phosphogluconate.

Anaerobic anoxygenic phototrophic Proteobacteria and aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic Proteobacteria

Anaerobic anoxygenic phototrophic Proteobacteria are the most metabolically versatile among photosynthetic bacteria. Some AnAPs are known to employ either the EMP or ED pathway, depending on growth conditions and nutrients, for carbohydrate catabolism, whereas the OPP pathway has not been reported to be active in AnAPs. Employing activity assays, sugar consumption, analysis of labeled amino acids using 14C-labeled sugar in wild-type and Glc-6-phosphate dehydrogenase-deficient mutant, previous studies indicate that Rba. capsulatus and Rba. sphaeroides utilize the EMP (or the ED) pathway to oxidize fructose during phototrophic (or chemotrophic) growth, and operate the ED pathway to dissimilate glucose during both phototrophic and chemotrophic (dark) growth (Conrad and Schlegel, 1977, 1978; Fuhrer et al., 2005). Consistent with the experimental data, all of the genes in the ED pathway have been identified in the genome of Rba. capsulatus and Rba. sphaeroides. Other AnAPs are missing either the gene encoding 6-phosphogluconate dehydratase (such as Bradyrhizobium sp. BTAi1) or all of the genes (i.e., Rsp. centenum, Rsp. Rubrum, and all of the strains of Rps. palustris) in the ED pathway.

Genes in the ED pathway are present in the genomes of AAPs (Tang et al., 2009a), and an active ED pathway has been suggested in several AAPs (Yurkov and Beatty, 1998). Moreover, recent 13C-based metabolomics/fluxomics studies, transcriptomics, and activity assays indicate that two members of the AAPs, R. denitrificans OCh114 and Dinoroseobacter shibae DFL12, exclusively or mainly use the ED pathway to oxidize glucose. Both AAPs have an inactive EMP pathway (Furch et al., 2009; Tang et al., 2009a), even though all of the genes in the EMP pathway have been identified in the D. shibae genome (Furch et al., 2009). Like AnAPs, an active OPP pathway has also not been reported in AAPs (Yurkov and Beatty, 1998).

All of the marine Roseobacter species that have been sequenced have genes in the ED pathway in their genome (Moran et al., 2007; Brinkhoff et al., 2008). Many marine Roseobacter species are non-phototrophs, some of which have been shown to operate an active ED pathway (Yurkov and Beatty, 1998; Furch et al., 2009). Thus, both phototrophic and non-phototrophic Roseobacters utilize the ED pathway. Note that many strains of AAPs and AnAPs that use the ED pathway do not have the pgd gene (encoding 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase) in the OPP pathway (Lim et al., 2009; Strnad et al., 2010) and/or the pfk gene (encoding 6-phosphofructokinase) in the EMP pathway (Swingley et al., 2007; Tang et al., 2009a). The selective evolutionary advantages of losing the pfk gene and/or the pgd gene, and having an inactive EMP pathway or/and the OPP pathway (Furch et al., 2009; Tang et al., 2009a), remain unclear.

Heliobacteria

d-Fructose and d-glucose can support phototrophic growth of Heliobacterium gestii, one of the heliobacteria discovered in tropical paddy soil (Madigan, 2006). Hbt. modesticaldum is closely related to Hbt. gestii in phylogeny (Bryantseva et al., 1999). All of the genes in the EMP pathway are present in the Hbt. modesticaldum genome. Consistent with genomic annotation and phylogenetic analyses, recent studies demonstrate that d-glucose, d-fructose, and d-ribose can support the phototrophic growth of Hbt. modesticaldum with a trace amount of yeast extract supplied (Tang et al., 2010b). Because Hbt. modesticaldum has a complete EMP pathway, but does not have key genes in the OPP and ED pathways (Sattley et al., 2008), it is likely that Hbt. modesticaldum employs the EMP pathway for carbohydrate catabolism and hydrogen production as suggested in certain thermophilic microbes (de Vrije et al., 2007). An active ED pathway has not been reported in any heliobacteria, consistent with the fact that very few Gram-(+) bacteria employ the ED pathway.

Filamentous anoxygenic phototrophs

Most of the reports of carbohydrate metabolism of FAPs have focused on Cfl. aurantiacus, which is the most investigated FAP bacterium (or green non-sulfur/gliding bacterium). Cfl. aurantiacus has been reported to grow well on glucose and a number of other sugars during aerobic respiration (Madigan et al., 1974), and it uses the EMP pathway for carbohydrate catabolism (Krasilnikova et al., 1986). An active ED pathway has not been identified in FAPs. Gene annotation in Cfl. aurantiacus indicates that the PP pathway is complete (Tang et al., 2011), consistent with the activities reported for Glc-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH) and 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (6PGDH), two essential enzymes in the OPP pathway (Krasilnikova et al., 1986). Note that the fbaA gene encoding FBP aldolase in the EMP/gluconeogenic pathway is missing in the genome of Chloroflexi species (e.g., Cfl. aurantiacus, Chloroflexus sp. Y-400-fl, and Cfl. aggregans; Tang et al., 2011). If Cfl. aurantiacus were unable to synthesize FBP aldolase, an active OPP pathway would be employed for the interconversion of d-Glc-6-phosphate and GAP, so sugars can be converted to pyruvate and other energy-rich species, and vice versa. However, higher activities of phosphofructokinase and fructose 1,6-bisphosphate (FBP) aldolase have been found in Cfl. aurantiacus grown with glucose than with acetate (Krasilnikova and Kondrateva, 1987; Kondratieva et al., 1992; Hanada and Pierson, 2006). Thus, Cfl. aurantiacus and other Chloroflexi species may employ a novel FBP aldolase. Note that Roseiflexi species (Roseiflexus sp. RS-1 and Roseiflexus castenholzii), which are closely related to Chloroflexi species, have a putative a bifunctional FBP aldolase/phosphatase gene identified (Say and Fuchs, 2010). Genes encoding various types of aldolase are present in the Cfl. aurantiacus genome (Tang et al., 2011). Further work is needed to clarify this picture.

Cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria can use the OPP pathway and the EMP pathway for carbohydrate dissimilation (Smith, 1982). Some cyanobacteria, such as Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803, can assimilate glucose during mixotrophic growth (Astier et al., 1984), and other species can grow on fructose (Wolk, 1973). Further, genes in the EMP pathway and the PP pathway have been identified in the genome of cyanobacteria. Fermentative growth of cyanobacteria with carbohydrates has been reported (Stal and Moezelaar, 1997), and the OPP pathway has been recognized to be the main route for oxidizing glucose (Carr, 1973; Smith, 1982) and providing the reducing equivalents to nitrogenase in diazotrophic cyanobacteria (Summers et al., 1995; Bergman et al., 1997). The importance of G6PDH and 6PGDH in the OPP pathway for the growth of cyanobacteria has been demonstrated (Scanlan et al., 1995; Hagen and Meeks, 2001; Knowles and Plaxton, 2003), and the reaction of G6PDH in cyanobacteria is also known to be regulated by thioredoxin (Cossar et al., 1984; Lindahl and Florencio, 2003). In addition, the EMP pathway in cyanobacteria is also suggested to be active. Other than glucose, some cyanobacteria, such as Cyanothece, can grow on glycerol (Feng et al., 2010a). Glycerol is a precursor for biosynthesis of triacylglycerols, and can be also converted to GAP in the EMP/gluconeogenic pathway.

Aldolases employed in the EMP and ED pathways

Figure 5B shows the reactions catalyzed by fructose 1,6-bisphosphate (FBP) aldolase (EC 4.1.2.13) and 2-keto-3-deoxy-6-phosphogluconate (KDPG) aldolase (EC 4.1.2.14). The reactions catalyzed by both aldolases are reversible. FBP aldolase, catalyzing the interconversion of FBP and d-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (GAP)/dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP), is widely distributed in phototrophs due to being employed by both the EMP pathway and gluconeogenesis.

FBP aldolase

Different classes of FBP aldolases have been identified in archaea, bacteria, and eukaryotes (Say and Fuchs, 2010), and some FBP aldolases are also responsible for additional biological functions (Grochowski and White, 2008). All of the phototrophic bacteria, except FAPs, have the class II FBP aldolase (encoded by the fbaA gene), which has been mainly found in bacteria and fungi. The fbaB gene encoding the class I FBP aldolase, mainly found in eukaryotes, can also be identified in the genomes of AnAPs, AAPs, cyanobacteria, and heliobacteria. Further, a bifunctional FBP aldolase/phosphatase enzyme, which has no sequence homology with the classical FBP aldolases, was recently identified in some archaea. The bifunctional enzyme has been suggested to be an ancestral enzyme in gluconeogenesis (Say and Fuchs, 2010). Genes encoding the bifunctional FBP aldolase/phosphatase have also been found in the genomes of phototrophs Roseiflexi species (Say and Fuchs, 2010).

KDPG aldolase

KDPG aldolase, which catalyzes the interconversion of KDPG and GAP/pyruvate (Figure 5B), is one of the two enzymes specific for the ED pathway, and the other specific enzyme is 6-phosphogluconate dehydratase. While KDPG aldolase is required in the ED pathway, KDPG aldolase is not specific to the ED pathway and is also responsible for Arg, Pro, glyoxylate, and dicarboxylase metabolism (Conway, 1992). KDPG aldolase has been identified in AnAPs (Conrad and Schlegel, 1977, 1978; Conway, 1992) and AAPs (Yurkov et al., 1991; Furch et al., 2009; Tang et al., 2009a) that use the ED pathway for carbohydrate oxidation. The ED pathway has not been reported in cyanobacteria, while the eda gene encoding KDPG aldolase has been found in the genome of many cyanobacterial strains. Although no detailed studies of KDPG aldolases from phototrophs have been reported, sequence alignments suggest that all of the phototrophic bacterial KDPG aldolases are the class I KDPG aldolases, which form an internal active site lysine-substrate aldimine for catalysis (Fullerton et al., 2006).

The structure-function relationships and reaction mechanism of the class I KDPG aldolase in non-phototrophs have been investigated intensively (Allard et al., 2001; Ahmed et al., 2005; Fullerton et al., 2006). These studies indicate that the class I KDPG aldolase in the phosphorylative, semi-phosphorylative and non-phosphorylative ED pathways has promiscuous substrate specificities, and can interact with phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated substrates, i.e., KDPG, 2-keto-3-deoxy-gluconate (KDG), GAP, and d-glyceraldehyde, pyruvate and its analogs, and a wide range of aldehyde components (Griffiths et al., 2002; Ahmed et al., 2005). Further, the enzyme from the aerobic thermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus, and perhaps Thermoplasma acidophilum, and other thermoacidophilic Archaea, also has high relative activity with 2-keto-3-deoxygalactonate (KDGal; Lamble et al., 2003). Directed evolution and site-directed mutagenesis have also been employed to further broaden the substrate specificities of the class I KDPG aldolase (Franke et al., 2004; Cheriyan et al., 2007).

The tricarboxylic acid cycle

Forward, reverse, and branched TCA cycles

Many metabolites in the TCA cycle are the precursors of amino acids and biomass. At least three forms of the TCA cycle have been identified in phototrophic bacteria: the forward TCA cycle (or the OTCA cycle), the reverse TCA cycle (or the RTCA cycle), and the branched (or incomplete) TCA cycle. The OTCA cycle or the Krebs cycle, discovered by Sir Hans Krebs more than seven decades ago (Krebs and Johnson, 1937), produces reducing equivalents and ATP, and is one of the most important, if not the most essential, central carbon and energy metabolic pathway in phototrophs and non-phototrophs. AnAPs (Imhoff et al., 2005; Madigan and Jung, 2009) and AAPs (Yurkov and Beatty, 1998; Furch et al., 2009; Tang et al., 2009a) employ an active OTCA cycle, like most non-phototrophic organisms. Cfl. aurantiacus operates the OTCA cycle under either aerobic (in darkness) or anaerobic (in the light) growth conditions (Sirevag and Castenholtz, 1979), whereas the family Oscillochloridaceae in FAPs have a partial RTCA cycle (Berg et al., 2005). GSBs channel the reducing equivalents generated via photosynthetic electron transport to the RTCA cycle, which functions as an autotrophic CO2 assimilation pathway for producing cellular material (Evans et al., 1966a; Sirevag, 1995). GSBs also operate the incomplete OTCA cycle (from citrate to α-ketoglutarate) during mixotrophic growth with acetate (Feng et al., 2010b; Tang and Blankenship, 2010). Cyanobacteria have a branched TCA cycle and do not have enzymes catalyzing interconversion of α-ketoglutarate and succinate (Stanier and Cohen-Bazire, 1977). The carbon flux via the branched TCA cycle is very low during photoautotrophic growth of cyanobacteria. In this case, cyanobacteria use the branched TCA cycle for synthesizing biomass rather than producing ATP and reducing equivalents (Shastri and Morgan, 2005).

Compared to the energy-producing OTCA cycle, metabolic flux in the RTCA cycle is energetically unfavorable. While several reactions in the TCA cycle are reversible, the reductive carboxylation of succinyl-CoA to α-ketoglutarate (catalyzed by α-ketoglutarate synthase) and of acetyl-CoA to pyruvate (catalyzed by pyruvate synthase) in the RTCA cycle are not thermodynamically favorable. The standard Gibbs free energy change of the decarboxylation of pyruvate in pyruvate synthase is estimated to be −4.6 kcal/mol (Thauer et al., 1977). Thus, GSBs and other organisms using the RTCA cycle recruit strong reductants, such as reduced ferredoxin, to operate the carboxylation reactions catalyzed by pyruvate synthase and α-ketoglutarate synthase and to proceed the RTCA cycle efficiently.

Compared to other phototrophic bacteria, the carbon flow of heliobacteria has not been understood until recently. The enzyme activity of ATP citrate lyase, the key enzyme in the RTCA cycle, and (Si)-citrate synthase, the common enzyme for synthesizing citrate to initiate the OTCA cycle (see below), have not been detected in heliobacteria (Pickett et al., 1994; Tang et al., 2010a). Genes encoding ATP citrate lyase and (Si)-citrate synthase have not been found in heliobacteria, whereas all other genes in the RTCA cycle have been found in Hbt. modesticaldum genome (Sattley et al., 2008). Feeding the cultures with [2-13C]acetate and probing the 13C-labeling patterns of Glu, Kelly, and coworkers suggested that Heliobacterium strain HY-3 uses the OTCA cycle to synthesize α-ketoglutarate (Pickett et al., 1994). However, the authors cannot explain these observations with the lack of the (Si)-citrate synthase. Our recent studies indicate that Hbt. modesticaldum uses (Re)-citrate synthase to initiate the incomplete OTCA cycle (from citrate to α-ketoglutarate) to synthesize Glu, and that carbon flux is mostly carried out through the incomplete OTCA cycle (Tang et al., 2010b).

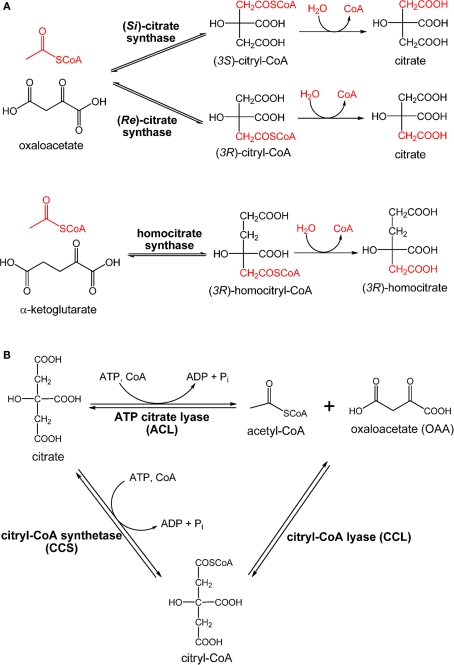

Enzymes operating in citrate metabolism

Enzymes that synthesize citrate

Citrate synthase is required for producing citrate through assimilating acetyl-CoA and OAA to initiate the OTCA cycle that generates reducing equivalents. The citrate synthase reported in current textbooks and most of the literature is (Si)-citrate synthase [(Si)-CS; EC 2.3.3.1]. The majority of organisms, including four types of photosynthetic microbes: AAPs, AnAPs, FAPs, and cyanobacteria, use (Si)-CS to synthesize citrate from acetyl-CoA and OAA for initiating the OTCA cycle. The gltA gene encoding (Si)-CS has also been identified in the genome of GSBs (Eisen et al., 2002; Davenport et al., 2010). Alternatively, the activity of (Si)-CS has not been detected in heliobacteria (Pickett et al., 1994; Tang et al., 2010b), and the gltA gene is absent in the Hbt. modesticaldum genome (Sattley et al., 2008). However, when performing the enzyme assays under anaerobic conditions, product turnover has been detected in cell-free extracts of Hbt. modesticaldum with the addition of acetyl-CoA, OAA, and Mn2+ metal ions (Tang et al., 2010a). Further, the fifth carbon position of Glu has been found to be 13C-labeled using [1-13C]pyruvate, also suggesting that Hbt. modesticaldum synthesizes citrate via (Re)-citrate synthase [(Re)-CS; EC 2.3.3.3; Tang et al., 2010a]. If citrate is synthesized via (Si)-CS, the first carbon position of Glu is expected to be labeled using [1-13C]pyruvate. Differences in the labeling patterns of Glu result from whether (Si)-CS or (Re)-CS attaches the acetyl group at the pro-S or pro-R arm of OAA, respectively. The final product of (Re)-CS versus (Si)-CS is the same, since citrate is a symmetric molecule, while the intermediate, (3R)-citryl-CoA versus (3S)-citryl-CoA, is different (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

Enzymes involved in citrate metabolism and central carbon metabolism. Claisen condensation catalyzed by (Re)-citrate synthase, (Si)-citrate synthase, and homocitrate synthase (A) and retro-aldol reactions catalyzed by ATP citrate lyase (ACL) and citryl-CoA synthetase (CCS)/citryl-CoA lyase (CCL) (B) are shown.

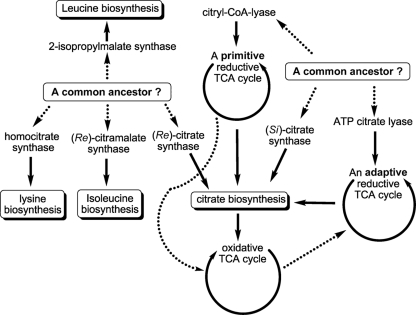

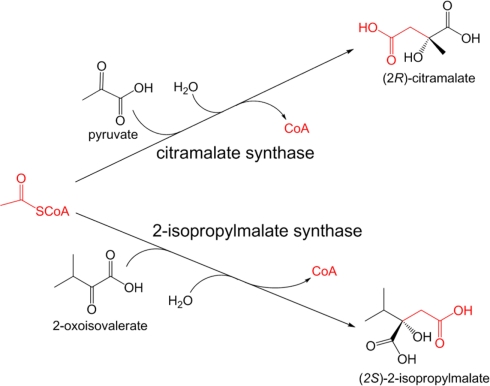

Compared to (Si)-CS, (Re)-CS is an unconventional enzyme for citrate biosynthesis, and is phylogenetically related to homocitrate synthase (EC 2.3.3.14) and 2-isopropylmalate synthase (Li et al., 2007). Homocitrate synthase catalyzes the formation of (3R)-homocitrate via the Claisen condensation of acetyl-CoA and α-ketoglutarate (Tucci and Ceci, 1972; Wulandari et al., 2002; Figure 6A). Similar sequences and active site structures between 2-isopropylmalate synthase and homocitrate synthase have also been suggested (Qian et al., 2008). Also, bacteria with the activity of (Re)-CS reported often employ citramalate synthase for isoleucine synthesis (Feng et al., 2009; Tang et al., 2009b, 2010a). Together, (Re)-CS, homocitrate synthase (Figure 6A), 2-isopropylmalate synthase, and citramalate synthase (Figure A1 in Appendix) catalyze Claisen condensation type reactions with similar α-ketoacid substrates, and may have evolved from the same ancestor (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Proposed evolutionary perspectives of some central carbon metabolic pathways. Previous studies suggested that 2-isopropylmalate synthase, homocitrate synthase, citramalate synthase, and (Re)-citrate synthase may have evolved from a common ancestor, and that (Si)-citrate synthase, ATP citrate lyase and citryl-CoA lyase may have evolved from another common ancestor. The oxidative TCA cycle was thought to have evolved from the primitive reductive TCA cycle, whereas the reductive TCA cycle operated in the GSBs has been proposed to be an adaptive form that may have evolved from the OTCA cycle. The proposed evolutionary links are shown in dashed lines.

Sequence comparisons between (Re)-CS and (Si)-CS also suggest that these two types of CS are phylogenetically distinct (Li et al., 2007). As indicated by other enzyme pairs that catalyze the formation of stereroisomers (Lamzin et al., 1995), dissimilar active site structures between (Re)-CS and (Si)-CS are expected to generate different citrate isomers. Moreover, unlike the potent inhibition of aconitase by (−)-erythro-2-F-citrate, previous studies have suggested that (+)-erythro-2-F-citrate, synthesized from 2-fluoroacetate, and OAA by (Re)-CS, is not an inhibitor of aconitase (Lauble et al., 1996; Tang et al., 2010a).

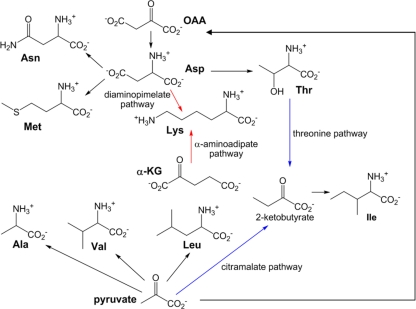

While Hbt. modesticaldum does not have the gene encoding (Re)-CS, two genes encoding putative homocitrate synthases have been identified in the Hbt. modesticaldum genome (Sattley et al., 2008). Homocitrate has only one known task in cells: serving as the precursor for lysine biosynthesis via the α-aminoadipate pathway. However, except for genes encoding putative homocitrate synthase, other genes in the α-aminoadipate pathway (Figure A2 in Appendix) have not been identified in the Hbt. modesticaldum genome, so the function of the putative homocitrate synthases remains to be verified. Whether one of the putative homocitrate synthases or another gene product functions as (Re)-CS in heliobacteria should be investigated.

Enzymes that dissimilate citrate

Cleavage of citrate through the RTCA cycle produces acetyl-CoA and OAA for building cellular material. Citrate cleavage in biological organisms can be accomplished by three enzymes: citrate lyase (EC 4.1.3.6), ATP citrate lyase (ACL; EC 4.1.3.8), or citryl-CoA synthetase (CCS; or so called citryl-CoA ligase) followed by citry-CoA lyase (CCL; Aoshima et al., 2004b; Hugler et al., 2007). The reaction of citrate lyase, which cleaves citrate into acetate and oxaloacetate (OAA), is distinct from ACL and CCS/CCL, which catalyze ATP-dependent cleavage of citrate to OAA and acetyl-CoA (Figure 6B). The phototrophic GSBs and some anaerobic bacteria use ACL to dissimilate citrate produced via the RTCA cycle into acetyl-CoA and OAA (Evans et al., 1966a; Wahlund and Tabita, 1997; Kanao et al., 2001; Kim and Tabita, 2006; Hugler et al., 2007; Voordeckers et al., 2008). The reaction catalyzed by the Cba. tepidum ACL in vivo has been suggested to be reversible (Tang and Blankenship, 2010), and ACL is also responsible for the citrate synthesis for acetate oxidation in the OTCA cycle in some anaerobic chemotrophic bacteria (Thauer et al., 1989). Moreover, ACL is also responsible for producing cytoplasmic acetyl-CoA for many biological processes in eukaryotic cells, such as histone acetylation, lipid production, a signal for activating glucose catabolism and apoptosis (Rathmell and Newgard, 2009; Wellen et al., 2009; Chu et al., 2010; Morrish et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2010; Zhao et al., 2010).

Different isoforms of ACLs have been identified. While a metazoan ACL (mACL) consists of a single polypeptide (Sun et al., 2010), ACL from other organisms, including other eukaryotic cells (fungi, yeast, and plants) and microorganisms, including GSBs (Wahlund and Tabita, 1997; Kim and Tabita, 2006), has two subunits (encoded by aclA and aclB). Sequence comparisons between the one-subunit ACL (mACL) and the two-subunit ACL (non-mACL) suggest the one-subunit ACL is a gene fusion product of the two-subunit ACL. Also, a second type of ACL (the type II ACL) has also been reported recently in the magnetotactic α-Proteobacterium Magnetococcus sp. MC-1, which uses the RTCA cycle for autotrophic CO2 fixation (Williams et al., 2006), and has also been proposed in several proteobacterial genomes (Hugler and Sievert, 2011). The function of the type II ACL has not been biochemically confirmed.

While eukaryotes and most prokaryotes operate ACL, certain non-photosynthetic bacteria use CCL and CCS, instead of ACL, for citrate cleavage (Figure 6B). An obligately chemolithoautotrophic bacterium H. thermophilus (Aoshima et al., 2004a,b) and some members of the family Aquificaceae (Hugler et al., 2007) have been reported recently to use CCS and CCL to cleave citrate. Further, the iron-oxidizing bacterium Leptospirillum ferriphilum has genes encoding CCL and CCS, but not ACL, identified in the genome (Levican et al., 2008).

Citrate metabolism and the TCA cycle: evolution or adaptation?

Citrate metabolism operates in every living cell. Citrate biosynthesis is required for initiating the OTCA cycle, and oxidation of citrate through the OTCA cycle creates reducing equivalents and energy. ATP-dependent citrate cleavage produces acetyl-CoA and OAA to build cellular material. (Re)-CS and (Si)-CS catalyze citrate biosynthesis and start the OTCA cycle, and ACL and CCS/CCL operate ATP-dependent citrate cleavage via the RTCA cycle. Sequence alignments suggest that (Si)-CS and CCL are phylogenetically relevant, and that ACL is likely a gene fusion product of (Si)-CS (or CCL) and succinyl-CoA synthetase. Sequences of CCS and succinyl-CoA synthetase are also similar (Aoshima et al., 2004a). Additionally, slight CCL activity has been reported in (Si)-CS (Srere, 1963) and low (Si)-CS activity has also been found in the H. thermophilus CCL (Aoshima et al., 2004b). Based on the sequence homology of enzymes involved in citrate metabolism, (Si)-CS may have evolved from CCL and ACL may have evolved from CCL [or (Si)-CS), CCS and succinyl-CoA synthetase (Aoshima et al., 2004b]. Note that some species in the Aquificae phylum use CCL/CCS and others operate ACL for citrate cleavage (Hugler et al., 2007), suggesting that ACL and CCL/CCS may share some evolutionary history. ACL, (Si)-CS, and CCL may have evolved from a common ancestor (Figure 7).

The OTCA cycle has been suggested to have evolved from the RTCA cycle (Wachtershauser, 1990). GSBs, which use ACL for citrate cleavage, may operate the RTCA cycle through an adaptation and horizontal gene transfer in response to environmental changes. Note that genes encoding (Si)-CS (gltA) and ACL (aclBA) are present in the genomes of GSBs (Eisen et al., 2002; Davenport et al., 2010). The sequence information suggests that ACL may have evolved from (Si)-CS and succinyl-CoA synthetase (Aoshima et al., 2004b). In addition to the RTCA cycle, GSBs also operate a partial OTCA cycle during mixotrophic growth (Tang and Blankenship, 2010). Phylogenetic analyses with 16S rRNA genes of photosynthetic bacteria (Woese, 1987; Pace, 1997) suggest that GSBs evolved later than FAPs, which have an active OTCA cycle. Taken together, the RTCA cycle in GSBs may have evolved from the OTCA cycle. The proposed evolutionary lineages of citrate metabolism and the TCA cycle in the central carbon metabolic network are illustrated in Figure 7.

Evolutionary perspectives of central carbon metabolism

Understanding the evolution of photosynthesis is an important objective in a deeper understanding of the origin and development of photosynthetic diversity. Lateral and horizontal transfers of photosynthetic genes among phototrophic bacteria have been proposed during the evolution of photosynthesis (Nagashima et al., 1997; Raymond et al., 2002; Raymond and Blankenship, 2004), although it has not been generally accepted which bacteria were donors and which bacteria were recipients during gene transfers. The photosystems of photosynthetic bacteria have been well studied. Proteobacteria (AnAPs and AAPs) and FAPs have a type II (quinone type) RC, and GSBs, chloroacidobacteria and heliobacteria have a type I (Fe-S type) RC (Blankenship, 2002). Phototrophic bacteria containing the same type (or different types) of RCs have been known to use distinct (or similar) light-harvesting antenna complexes. For example, chlorosomes are present in Chloroflexi species (FAPs), GSBs, and chloroacidobacteria but absent in Proteobacteria, the Roseiflexi species (FAPs), and heliobacteria. Also, GSB, chloroacidobacteria and heliobacteria have a type I RC, while heliobacteria have no light-harvesting complexes other than antenna pigments that are part of the RC core complex. This is distinct from GSB and chloroacidobacteria, both of which contain chlorosomes and the Fenna–Matthews–Olson (FMO) complex. So there seems to be little correlation between the RC types and the light-harvesting antenna complexes in anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria. These features suggest horizontal gene transfers of RC or light-harvesting complexes among phototrophic bacteria. Moreover, some features in the carbon metabolism of phototrophic bacteria suggested below also suggest horizontal gene transfers between phototrophic and non-phototrophic bacteria.

Central carbon metabolism of heliobacteria versus non-phototrophic Firmicutes

Among GSBs, chloroacidobacteria, and heliobacteria, only GSBs are known to be photoautotrophs. Heliobacteria, the only Gram-(+) phototrophic bacteria, use (Re)-CS to produce citrate possibly via the (3R)-citryl-CoA intermediate, and GSBs contain the gene encoding (Si)-CS and use ACL and/or (Si)-CS to synthesize (Si)-CS. Previous studies indicate that several Clostridia species exclusively use (Re)-CS to synthesize citrate (Li et al., 2007). Additionally, two types of phosphoglycerate mutase (PGM) have been reported to catalyze the interconversion of 2-phosphoglycerate and 3-phosphoglycerate in carbohydrate metabolism: the cofactor-dependent PGM (dPGM) and cofactor-independent PGM (iPGM). It has been suggested that dPGM may be evolutionarily related to a family of acid phosphatases and to fructose 2,6-bisphosphatase (Schneider et al., 1993), and that iPGM has been derived from the family of alkaline phosphatase and sulfatases (Galperin et al., 1998). Heliobacteria have the gpmI gene (encoding iPGM; Sattley et al., 2008) and GSBs have the gpmA gene (encoding dPGM). Likewise, members of the Gram-(+) bacteria, including spore-forming Firmicutes (Bacillus and Clostridium), use iPGM, whereas most of the Gram-(−) bacteria employ dPGM. Moreover, although both GSBs and heliobacteria have pyruvate synthase/α-ketoglutarate synthase instead of pyruvate dehydrogenase/α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase, their carbon flow patterns in the TCA cycle are entirely different (Feng et al., 2010b; Tang and Blankenship, 2010; Tang et al., 2010a). Together, gene/enzyme pairs in citrate biosynthesis and sugar metabolism, and carbon flow in the TCA cycle of heliobacteria versus GSBs clearly indicate that their carbon metabolism correlates with the 16S rRNA-based phylogeny of the group (Firmicutes), rather than with the presence of the photosynthetic RC. According to many similarities in carbon metabolism between heliobacteria and non-phototrophic Firmicutes, either genes encoding carbon metabolism in non-phototrophic Firmicutes may have been transferred from or to heliobacteria, or genes encoding photosystems in heliobacteria may have been transferred from other photosynthetic bacteria. The latter hypothesis is consistent with the fact that heliobacteria have the simplest photosystem among phototrophic bacteria (Madigan, 2006; Heinnickel and Golbeck, 2007; Sattley et al., 2008; Sattley and Blankenship, 2010).

Conclusion

All life on Earth requires carbon sources and energy. Phototrophic bacteria use light as the energy source for autotrophic, mixotrophic and also heterotrophic growth. The carbon metabolism in photosynthetic bacteria is not only essential for constructing cellular material, but also providing reducing equivalents for photosynthetic electron transport during photoheterotrophic growth. The central carbon metabolism of photosynthetic bacteria has received more attention recently, mainly due to their metabolic versatility and/or uniqueness as well as the information acquired from systematic analyses. This review illustrates that photosynthetic bacteria employ many unconventional central carbon metabolic pathways and novel enzymes in response to their ecological niches, whereas certain carbon assimilation pathways remain to be understood. Further, both evolutionary origin and late adaptation have been suggested for several of the central metabolic enzymes and pathways. Together, the rich knowledge accumulated for central carbon metabolism, along with the information obtained from the genes of 16S rRNA, various enzymes and photosynthetic components, is expected to shed more light on the origin and evolution of photosynthesis.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Exobiology Program of NASA Grant NNX08AP62G (Robert Eugene Blankenship) and National Science Foundation Career Grant MCB0954016 (Yinjie J. Tang).

Appendix

Approaches for investigating carbon metabolism of phototrophs

Prior to the availability of genomic information, the carbon metabolism of phototrophic organisms was investigated by activity assays, together with stable isotope-labeling (Strauss et al., 1992; Pickett et al., 1994) or radioactive isotopic-labeling experiments (Bassham et al., 1950; Evans et al., 1966b; Conrad and Schlegel, 1977). Recently, functional characterization of phototrophic organisms has been accelerated because: (1) The instruments and data analyses of GC-/LC-MS (gas/liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry) and NMR (nuclear magnetic resonance) have been significantly improved; (2) high-throughput sequencing methods have determined complete genomes of photosynthetic organisms and many of their genomes have been fully annotated; and (3) more systematic approaches (i.e., “omics”), such as transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and fluxomics (Sauer, 2006; Peyraud et al., 2009; Singh et al., 2009; Stitt et al., 2010; Tripp et al., 2010), have been developed. Among these metabolomics approaches, 13C-based metabolic analysis and 13C-flux analysis have been recognized as powerful tools to probe active carbon metabolic pathways in vivo via feeding cells with a 13C-labeled carbon source and tracing 13C-labeling patterns in biomass and metabolites. Table A1 in Appendix illustrates several carbon metabolic pathways in phototrophic bacteria probed by 13C-labeled protein-based amino acids (Pickett et al., 1994; Furch et al., 2009; Peyraud et al., 2009; Tang et al., 2009a, 2010a; Feng et al., 2010a,b; Wu et al., 2010). In cooperation with in vivo physiological studies (or so called “physiomics”; Sanford et al., 2002), activity assays, and in vitro biochemical characterizations (Alber et al., 2006; Berg et al., 2007; Zarzycki et al., 2009), more knowledge and new insights into carbon metabolism of photosynthetic and non-photosynthetic microbes have been revealed.

Citramalate synthase and 2-isopropylmalate synthase

Citramalate synthase (EC 2.3.1.182), catalyzing the formation of (2R)-citramalate via the Claisen condensation of acetyl-CoA and pyruvate, is the first and the only specific enzyme employed in the citramalate pathway, which directly converts pyruvate to 2-ketobutyrate for isoleucine biosynthesis (Figure A2 in Appendix). All of the other enzymes in the citramalate pathway are also engaged in leucine biosynthesis (Xu et al., 2004). While citramalate synthase can only be identified in organisms that operate the citramalate pathway (Howell et al., 1999), 2-isopropylmalate synthase (EC 2.3.3.13), catalyzing the formation of (2S)-2-isopropylmalate via the Claisen condensation of 2-oxoisovalerate and acetyl-CoA, is universally required for leucine biosynthesis. 2-oxoisovalerate is also the precursor of valine. High sequence homology (∼50% identity and ∼70% similarity) between citramalate synthase and 2-isopropylmalate synthase has been reported (Howell et al., 1999; Xu et al., 2004; Risso et al., 2008), in agreement with similar substrates for these two enzymes (Figure A1 in Appendix).

Figure A1.

Reactions catalyzed by citramalate synthase and 2-isopropylmalate synthase.

Figure A2.

Amino acids biosynthesis in phototrophic and non-phototrophic bacteria. Biosynthesis of amino acids directly and indirectly employing pyruvate and oxaloacetate (OAA) as precursors is shown. The pathways for isoleucine and lysine biosynthesis are shown in blue and red, respectively. Phototrophic bacteria have not yet been known to synthesize lysine via the α-aminoadipate pathway.

Table A1.

The 13C-isotopomer labeling patterns of protein-based amino acids in central metabolic pathways of phototrophic bacteria using 13C-labeled carbon sourcesa,b,c.

| Pathways and enzymes | 13C-carbon sources | Biomarkersa | Featuresb,c | Phototrophic bacteria | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Entner–Doudoroff (ED) pathway | [1-13C]Glc or [6-13C]Glc | Ser, Ala | Notably lower (with [1-13C]Glc) or higher (with [6-13C]Glc) labeling in GAP than in pyruvate | AAP, AnAPs | Furch et al. (2009), Tang et al. (2009a) |

| The reductive TCA cycle | Non-labeled inorganic carbon and [3-13C]- pyruvate | Ala, Asp, Glu | Notably lower labeling in OAA/α-KG than pyruvate due to assimilating non-labeled inorganic carbon | GSBs, heliobacteria (incomplete) | Feng et al. (2010b) |

| The branched TCA cycle | [3-13C]pyruvate or [2-13C]- glycerol | Asp, Glu | Different labeling patterns in OAA versus in α-KG because labeled carbons are not scrambled in α-KG and OAA | Cyanobacteria | Feng et al. (2010a) |

| Citrate synthesized by (Re)-citrate synthase (via the OTCA cycle) | [1-13C]pyruvate | Glu | C5 position of α-KG labeled (versus C1 position of α-KG labeled with (Si)-citrate synthase) | Heliobacteria | Tang et al. (2010a) |

| The citramalate pathway in isoleucine biosynthesis | [2-13C]pyruvate or [1-13C]acetate | Leu, Ile | Identical labeling patterns in Leu and Ile because both amino acids are synthesized from acetyl-CoA and pyruvate | AAPs, GSBs, heliobacteria, cyanobacteria | Feng et al. (2010a),Feng et al. (2010b), Pickett et al. (1994), Tang et al. (2009a), Tang et al. (2010a), Wu et al. (2010) |

| The Calvin–Benson cycle | Non-labeled CO2 and [2-13C]- glycerol | His, Ser | Significantly low labeling in GAP and R5P due to assimilating non-labeled inorganic carbon | AnAPs, cyanobacteria, some FAPs | Feng et al. (2010a) |

| The oxidative PP pathway | [1-13C]Glc | Ala | 13C-labeling in Glc released as 13CO2 in the OPP pathway leads to non-labeled pyruvate >60% | FAPs, cyanobacteria | Feng et al. (2010a) |

| The CO2-anaplerotic pathways | 13C-bicarbonate or non-labeled inorganic carbon with [1-13C]- pyruvate | Asp | Enriched labeling in OAA | All of the photosynthetic bacteria | Feng et al. (2010a), Feng et al. (2010b), Pickett et al. (1994), Tang et al. (2009a), Tang et al. (2010a) |

| The ethylmalonyl-CoA pathway | [1-13C]acetyl-CoA and 13C-bicarbonate | Not applicable | Analysis of the intermediates and metabolites in the pathway | AnAPs (e.g., Rba. sphaeroides) and possibly AAPs | Peyraud et al. (2009) – studies on non-phototrophs |

aThe13C-labeling patterns of protein-based amino acids serve as biomarkers for probing metabolic pathways.

bAbbreviations: GAP, d-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate; Glc, glucose, α-KG, α-ketoglutarate; OAA, oxaloacetate; R5P, ribose-5-phosphate.

cPrecursors → Amino acids: GAP → Ser. OAA → Asp, pyruvate → → Ala, α-KG → Glu, and R5P → His.

Abbreviations

Abbreviations of phototrophic bacteria. Three-letter abbreviation for the generic name of phototrophic bacteria follows the information listed on LPSN (List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature) (http://www.bacterio.cict.fr/index.html). Other abbreviations. AAPs, aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic Proteobacteria; ACL, ATP citrate lyase; AnAPs, anaerobic anoxygenic phototrophic Proteobacteria; CCL, citryl-CoA lyase; CCS, citryl-CoA synthetase; (Re)/(Si)-CS, (Re)/(Si)-citrate synthase; ED, Entner–Doudoroff; EMP, Emden–Meyerhof–Parnas; FAPs, filamentous anoxygenic phototrophs; FBP, fructose 1,6-bisphosphate; Fd, ferredoxin; GAP, d-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate; Glc, glucose; GSBs, green sulfur bacteria; 3HOP, 3-hydroxypropionate; KDPG, 2-keto-3-deoxy-6-phosphogluconate; α-KG, α-ketoglutarate; OAA, oxaloacetate; OPP pathway, oxidative pentose phosphate pathway; OTCA/RTCA cycle, oxidative/reductive tricarboxylic acid cycle; PGM, phosphoglycerate mutase; RC, reaction center; R5P, ribose-5-phosphate; RuBisCO, ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase.

References

- Ahmed H., Ettema T. J., Tjaden B., Geerling A. C., van der Oost J., Siebers B. (2005). The semi-phosphorylative Entner-Doudoroff pathway in hyperthermophilic archaea: a re-evaluation. Biochem. J. 390, 529–540 10.1042/BJ20041711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alber B. E., Spanheimer R., Ebenau-Jehle C., Fuchs G. (2006). Study of an alternate glyoxylate cycle for acetate assimilation by Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Mol. Microbiol. 61, 297–309 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05238.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albers H., Gottschalk G. (1976). Acetate metabolism in Rhodopseudomonas gelatinosa and several other Rhodospirillaceae. Arch. Microbiol. 111, 45–49 10.1007/BF00446548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allard J., Grochulski P., Sygusch J. (2001). Covalent intermediate trapped in 2-keto-3-deoxy-6- phosphogluconate (KDPG) aldolase structure at 1.95-A resolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 3679–3684 10.1073/pnas.071380898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoshima M., Ishii M., Igarashi Y. (2004a). A novel enzyme, citryl-CoA synthetase, catalysing the first step of the citrate cleavage reaction in Hydrogenobacter thermophilus TK-6. Mol. Microbiol. 52, 751–761 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04009.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoshima M., Ishii M., Igarashi Y. (2004b). A novel enzyme, citryl-CoA lyase, catalysing the second step of the citrate cleavage reaction in Hydrogenobacter thermophilus TK-6. Mol. Microbiol. 52, 763–770 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04009.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astier C., Elmorjani K., Meyer I., Joset F., Herdman M. (1984). Photosynthetic mutants of the cyanobacteria Synechocystis sp. strains PCC 6714 and PCC 6803: sodium p-hydroxymercuribenzoate as a selective agent. J. Bacteriol. 158, 659–664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandyopadhyay A., Stockel J., Min H., Sherman L. A., Pakrasi H. B. (2010). High rates of photobiological H2 production by a cyanobacterium under aerobic conditions. Nat. Commun. 1, 139. 10.1038/ncomms1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassham J. A., Benson A. A., Calvin M. (1950). The path of carbon in photosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 185, 781–787 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg I. A., Keppen O. I., Krasil’nikova E. N., Ugol’kova N. V., Ivanovskii R. N. (2005). Carbon metabolism of filamentous anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria of the family Oscillochloridaceae. Microbiology 74, 258–264 10.1007/s11021-005-0060-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg I. A., Kockelkorn D., Buckel W., Fuchs G. (2007). A 3-hydroxypropionate/4-hydroxybutyrate autotrophic carbon dioxide assimilation pathway in archaea. Science 318, 1782–1786 10.1126/science.1152989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg I. A., Kockelkorn D., Ramos-Vera W. H., Say R. F., Zarzycki J., Hugler M., Alber B. E., Fuchs G. (2010). Autotrophic carbon fixation in archaea. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8, 447–460 10.1038/nrmicro2365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman B., Gallon J. R., Rai A. N., Sta L. J. (1997). N2 fixation by non-heterocystous cyanobacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 19, 139–185 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1997.tb00296.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Biebl H., Allgaier M., Tindall B. J., Koblizek M., Lunsdorf H., Pukall R., Wagner-Dobler I. (2005). Dinoroseobacter shibae gen. nov., sp. nov., a new aerobic phototrophic bacterium isolated from dinoflagellates. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 55, 1089–1096 10.1099/ijs.0.63832-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biebl H., Tindall B. J., Pukall R., Lunsdorf H., Allgaier M., Wagner-Dobler I. (2006). Hoeflea phototrophica sp. nov., a novel marine aerobic alphaproteobacterium that forms bacteriochlorophyll a. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 56, 821–826 10.1099/ijs.0.63958-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blankenship R. E. (2002). Molecular Mechanisms of Photosynthesis. Oxford: Blackwell Science Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Bricker T. M., Zhang S., Laborde S. M., Mayer P. R., III, Frankel L. K., Moroney J. V. (2004). The malic enzyme is required for optimal photoautotrophic growth of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 under continuous light but not under a diurnal light regimen. J. Bacteriol. 186, 8144–8148 10.1128/JB.186.23.8144-8148.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkhoff T., Giebel H. A., Simon M. (2008). Diversity, ecology, and genomics of the Roseobacter clade: a short overview. Arch. Microbiol. 189, 531–539 10.1007/s00203-008-0353-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant D. A., Costas A. M., Maresca J. A., Chew A. G., Klatt C. G., Bateson M. M., Tallon L. J., Hostetler J., Nelson W. C., Heidelberg J. F., Ward D. M. (2007). Candidatus Chloracidobacterium thermophilum: an aerobic phototrophic Acidobacterium. Science 317, 523–526 10.1126/science.1143236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant D. A., Frigaard N. U. (2006). Prokaryotic photosynthesis and phototrophy illuminated. Trends Microbiol. 14, 488–496 10.1016/j.tim.2006.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryantseva I. A., Gorlenko V. M., Kompantseva E. I., Achenbach L. A., Madigan M. T. (1999). Heliorestis daurensis, gen. nov. sp.nov., an alkaliphilic rod-to-coiled-shaped phototrophic heliobacterium from a siberian soda lake. Arch Microbiol 172, 167–174 10.1007/s002030050756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan B. B., Arnon D. I. (1990). A reverse KREBS cycle in photosynthesis: consensus at last. Photosyn. Res. 24, 47–53 10.1007/BF00032643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvin M. (1989). 40 years of photosynthesis and related activities. Photosyn. Res. 21, 3–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvin M., Benson A. A. (1948). The path of carbon in photosynthesis. Science 107, 476–480 10.1126/science.107.2784.476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]