Abstract

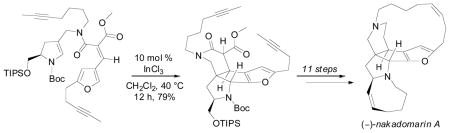

A concise diastereoselective total synthesis of (–)-nakadomarin A has been completed in 21 steps from D-pyroglutamic acid. Key steps include an enecarbamate Michael addition/furan-N-acyliminium ion cascade cyclization to provide the tetracyclic core, and ring-closing alkyne and alkene metatheses to construct the 15- and 8-membered azacycles, respectively.

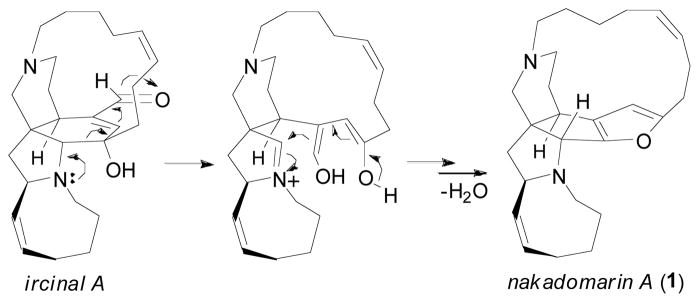

The manzamines are a class of architecturally fascinating, biologically active marine alkaloids.1 Perhaps the most structurally intriguing member is nakadomarin A (1), isolated by Kobayashi2a from an Okinawan sponge Amphimedon sp. Its structure consists of an unprecedented 6/5/5/5/8/15 hexacyclic ring system and is the only manzamine alkaloid that embodies a furan ring. A biosynthetic pathway from ircinal A has been proposed by Kobayashi2b (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Proposed biosynthesis of nakadomarin A.

This limited availability, coupled with an inspiring structure have made nakadomarin A the target of a number of synthetic groups.3 Nishida and co-workers have reported pioneering, though lengthy, total syntheses of both 14a and ent-14b (36 and 38 steps, respectively). Young and Kerr completed the total synthesis of ent-15 in 29 steps from D–mannitol. Most recently, the Dixon group reported the shortest synthesis of 1 to date, requiring only 16 total steps.6 A strategy common to each of these syntheses is the utilization of ring-closing alkene metathesis to construct the 15-membered macrocycle. While attractive in its efficiency, this approach yielded a mixture of configurational isomers in each case, often favoring the undesired E-isomer.7

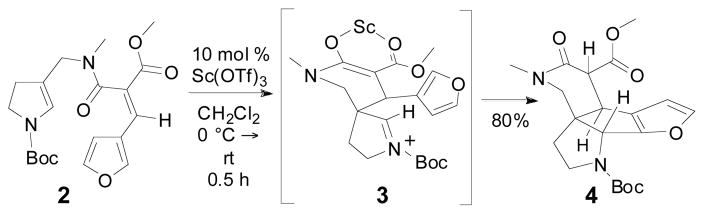

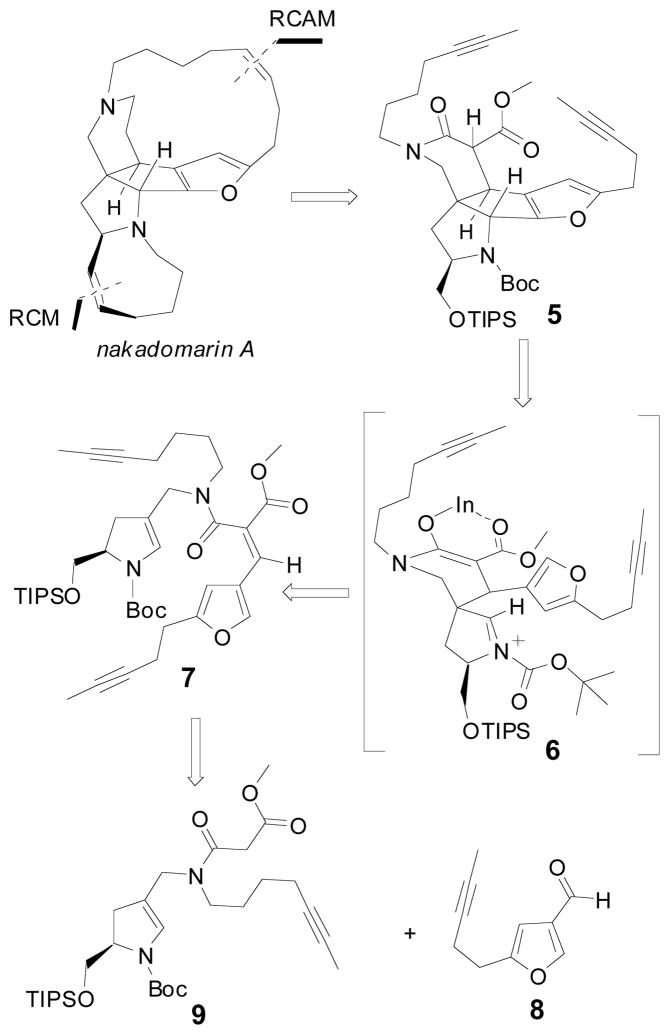

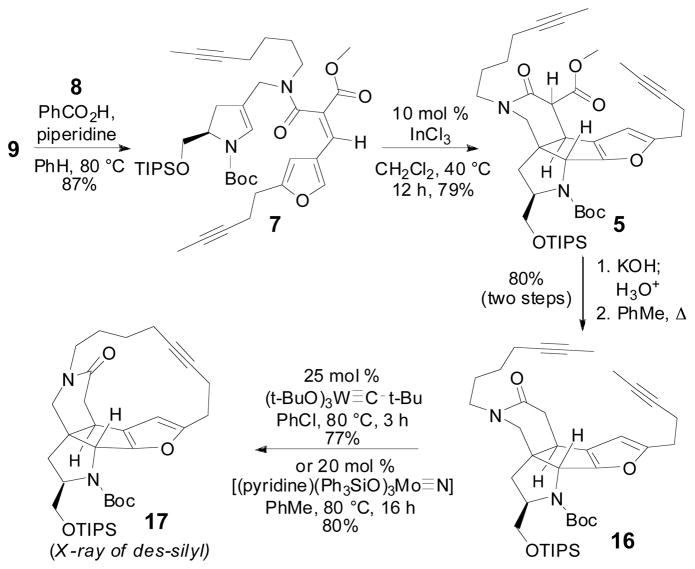

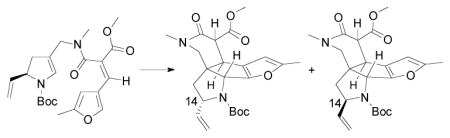

We recently reported our strategy for the rapid construction of the tetracyclic core of nakadomarin A.3h In the key step, enecarbamate 2 underwent a stereoselective intramolecular Lewis acid-catalyzed Michael addition, and the resulting N-acyliminium ion8 3 was trapped with the proximate furan to provide tetracycle 4 (Scheme 2). Based on the success of the model system study, we directed our efforts toward the preparation of a tetracycle analogous to 4 that would be fully functionalized for the completion of the total synthesis. Our retrosynthetic analysis is outlined in Scheme 3. Based on precedents from the previous total syntheses, ring-closing metathesis (RCM) could provide the eight- and fifteen-membered azacycles. We hoped to circumvent the E/Z selectivity problem in the construction of the macrocycle by utilizing a ring-closing alkyne metathesis (RCAM)9/semi-hydrogenation strategy to deliver the Z-cycloalkene as a single configurational isomer. The viability of this strategy was documented by Fürstner and co-workers in their synthesis of the macrocyclic perimeter of nakadomarin A.3b The key cyclization of enecarbamate 7 to the tetracycle 5 should follow the conjectured pathway in our model system. In this case, it was hoped that the Lewis acid-activated conjugated double bond would approach the enecarbamate from the face away from the bulky TIPS group10 through an anti conformer to provide the N-acyliminium ion 6 that would subsequently undergo closure with the now more electron rich furan substituent to deliver lactam 5. The key cyclization substrate 7 could be obtained as the thermodynamic product of Knoevenagel condensation of furaldehyde 8 with β– amido ester 9 (vida infra).

Scheme 2.

Model study of the construction of the core of 1.

Scheme 3.

Retrosynthetic analysis of (–)-nakadomarin A (1).

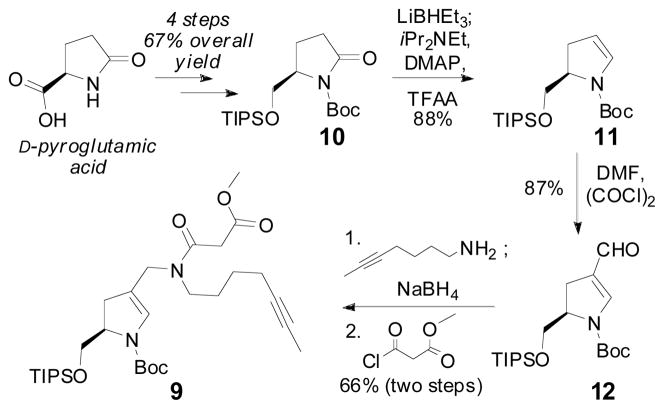

The preparation of amide 9 proceeded in a straightforward fashion (Scheme 4). Enecarbamate 11 was prepared from optically pure imide 1011 using the one-pot method recently reported by Yu.12 Vilsmeier- Haack formylation of enecarbamate 11 followed by reductive amination of the resultant vinylogous imide 12 with 5-heptynylamine provided the corresponding secondary amine. N-acylation with methyl malonyl chloride gave amide 9.

Scheme 4.

Preparation of amide 9.

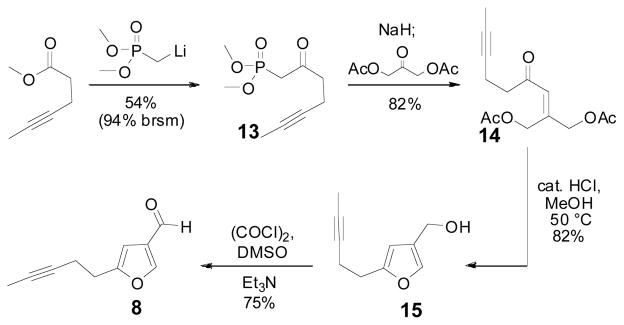

The preparation of furaldehyde 8 took advantage of Maldonado’s methodology for the synthesis of 2,4- disubstituted furans from γ, γ′-diacetoxyenones.13 Thus, metalation of dimethyl methyl phosphonate followed by treatment with methyl 4-hexynoate gave β– ketophosphonate 13 (Scheme 5). Horner-Wadsworth- Emmons reaction between phosphonate 13 and 1,3- diacetoxyacetone provided γ, γ ′-diacetoxyenone 14. This enone underwent smooth, acid-catalyzed cyclization in methanol at 50 °C to furanmethanol 15 in 82% yield. Finally, Swern oxidation of alcohol 15 furnished the desired furaldehyde 8.

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of furaldehyde 8.

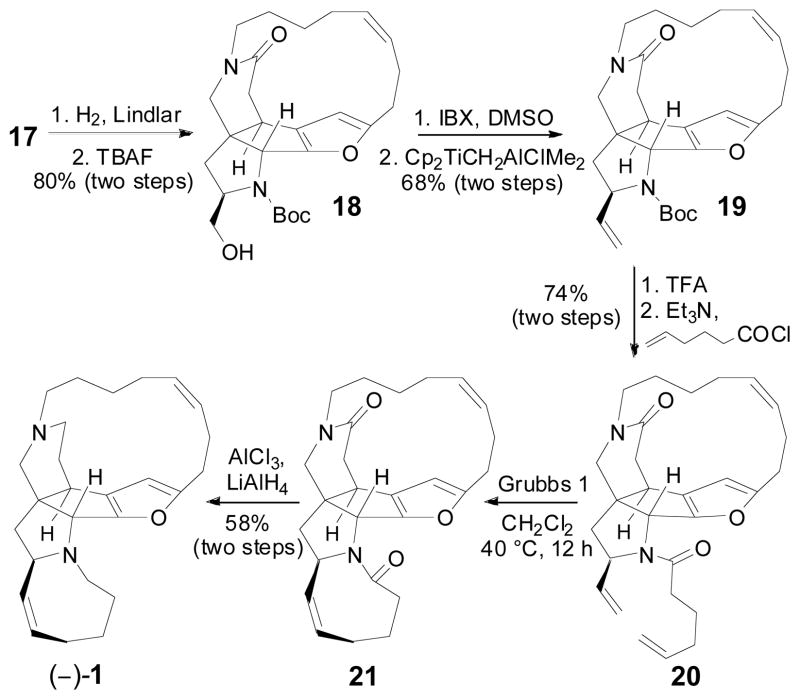

Based on observations made during our model system study, we anticipated that Knoevenagel condensation between amide 9 and furaldehyde 8 would provide unsaturated amide 7, possessing the requisite E-geometry for the cyclization to tetracycle 5. This thermodynamic control has been previously observed in related systems14 and can be rationalized by better overlap of the ester and adjacent double bond in E-amide 7, in contrast to the carbonyls of the corresponding Z-amide, both of which would be twisted out of conjugation. Much to our delight, heating amide 9 and furaldehyde 8 in benzene in the presence of benzoic acid and piperidine delivered the E-configurational isomer 7 as the sole product in 87% yield (Scheme 6). Subjection of enecarbamate 7 to our standard cyclization conditions (10 mol % Sc(OTf)3, CH2Cl2, rt) resulted in cyclization to the desired tetracycle. However, these reaction conditions also caused partial cleavage of the silyl ether, resulting in the isolation of a mixture of tetracyclic silyl ether 5 and the corresponding alcohol. This minor setback could be avoided altogether if InCl3 was employed as the catalyst and the reaction was run at reflux, providing tetracycle 5 in 79% yield. Saponification of ester 5 followed by thermally-promoted decarboxylation gave the lactam 16. The diyne functionality of lactam 16 was subjected to several different alkyne metathesis systems with varying levels of success. Grela’s optimized conditions15 of the Mortreux alkyne metathesis system16 (Mo(CO)6, 2- fluorophenol, 3-hexyne, 1,2-diphenoxyethane in chlorobenzene at 140 °C, 3 h) gave cycloalkyne 17 in 41% yield (54% brsm). The Schrock carbyne catalyst17 in chlorobenzene (25 mol %, 80 °C, 3 h) proved more effective, allowing cyclization to 17 in 77% yield on a gram scale. It should be noted the air-stable molybdenum nitride complex [(pyridine)(Ph3SiO)3Mo≡N] recently developed by Fürstner18a gave comparable results with a slightly lower catalyst loading (20 mol %, toluene at 80 °C, 16 h, 80% yield). The cis double bond of 15- membered ring was then introduced by straightforward Lindlar reduction of cycloalkyne 17 and unaccompanied by the E-olefin stereoisomer (Scheme 7).

Scheme 6.

Construction of the pentacyclic core of 1.

Scheme 7.

Completion of the total synthesis of 1.

Synthetic efforts were then directed to the construction of the azocine ring and completion of the total synthesis (Scheme 7). Deprotection of the TIPS ether 17 furnished alcohol 18. Oxidation of alcohol 18 with IBX in DMSO followed by Tebbe olefination (Wittig, Peterson and Nysted protocols were ineffective) proceeded uneventfully to yield vinyl pyrrolidine 19. Deprotection of the Boc carbamate with TFA and N-acylation with 5-hexenoyl chloride gave alkene metathesis substrate 20. Ring-closing metathesis of diene 20 to azocine 21 proved problematic. The best yield was obtained when diene 20 was treated with an equimolar amount of Grubbs 1st-generation catalyst in refluxing methylene chloride. Reduction of the resultant bis-lactam 21 with alane provided (–)-nakadomarin A in 58% overall yield from diene 20. Spectral data (NMR, IR, MS) was identical to that of natural 1. The optical rotation confirmed its absolute configuration ([α]D = −72.7 (c = 0.12, MeOH), lit.4a [α]D = −73.0 (c = 0.08, MeOH)).

In conclusion, we have completed a concise total synthesis of (–)-nakadomarin A in 21 steps from D– pyroglutamic acid. Our previously reported strategy for the rapid assembly of the tetracyclic core, which features a tandem enecarbamate Michael addition/furan-N-acyliminium ion cyclization, has now been modified to incorporate functionality for the completion of a completely diastereoselective total synthesis. Moreover, a sequential ring-closing alkyne metathesis/semi-hydrogenation strategy was utilized to obtain the 15- membered azacycle as a single configurational isomer. The flexibility of this route allows for the preparation of nakadomarin A structural analogs. Indeed, the cyclization of a pyrrole analogous to furan 2 was successful. These studies are currently underway and will be reported in due course.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the financial support provided by the National Institutes of Health (GM28663).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Spectroscopic data and experimental details for the preparation of all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Nishida A, Nagata T, Nakadawa M. Top Heterocyc Chem. 2006;5:255. and references therein. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Kobayashi J, Watanabe D, Kawasaki N, Tsuda M. J Org Chem. 1997;62:9236. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kobayashi J, Tsuda M, Ishibashi M. Pure Appl Chem. 1999;71:1123. [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Fürstner A, Guth O, Rumbo A, Seidel G. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:11108. [Google Scholar]; (b) Fürstner A, Guth O, Duffels A, Seidel G, Liebl M, Gabor B, Mynott R. Chem-Eur J. 2001;7:4811. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20011119)7:22<4811::aid-chem4811>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Nagata T, Nishida A, Nakagawa M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:8345. [Google Scholar]; (d) Magnus P, Fielding MR, Wells C, Lynch V. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:947. [Google Scholar]; (e) Leclerc E, Tius MA. Org Lett. 2003;5:1171. doi: 10.1021/ol034110x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Ahrendt KA, Williams RM. Org Lett. 2004;6:4539. doi: 10.1021/ol048126e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Young IS, Williams JL, Kerr MA. Org Lett. 2005;7:953. doi: 10.1021/ol0501018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Nilson MG, Funk RL. Org Lett. 2006;8:3833. doi: 10.1021/ol061463y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Deng H, Yang X, Tong Z, Li Z, Zhai H. Org Lett. 2008;10:1791. doi: 10.1021/ol800579j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Inagaki F, Kinebuchi M, Miyakoshi N, Mukai C. Org Lett. 2010;12:1800. doi: 10.1021/ol100412f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Nagata T, Nakagawa M, Nishida A. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:7484. doi: 10.1021/ja034464j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ono K, Nakagawa M, Nishida A. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2004;42:2020. doi: 10.1002/anie.200453673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Young IS, Kerr MA. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:1465. doi: 10.1021/ja068047t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jakubec P, Cockfield DM, Dixon DJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:16632. doi: 10.1021/ja908399s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nishida and Kerr obtained a 1:1.5 and 1:1.7 ratio of Z:E isomers, respectively. Dixon however obtained a favorable 1.7:1 Z:E ratio by including an excess of either enantiomer of camphorsulfonic acid in the metathesis reaction mixture.

- 8.For a review of N-acyliminium ion cyclizations, see: Maryanoff BE, Zhang HC, Cohen JH, Turchi TJ, Maryanoff CA. Chem Rev. 2004;104:1431. doi: 10.1021/cr0306182.

- 9.For reviews, see: Zhang W, Moore J. Adv Synth Catal. 2007;349:93.Fürstner A, Davies PW. Chem Commun. 2005;18:2307. doi: 10.1039/b419143a.

-

10.A vinyl group was initially investigated, but its steric influence was found to be insufficient, as a 1:1 mixture of diastereomers was obtained from the cyclization to the corresponding tetracycle. These stereoisomers are presumably epimeric at C14:

- 11.Prepared in four steps from D-pyroglutamic acid in 67% overall yield. For details, see Supporting Information.

- 12.Yu J, Truc V, Riebel P, Hierl E, Mudryk B. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005;46:4011. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Díaz-Cortés R, Silva AL, Maldonado LA. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:2207. [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Brown JM, Guiry PJ, Laing JCP, Hursthouse MB, Malik KMA. Tetrahedron. 1995;51:7423. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hamper BC, Kolodziej SA, Scates AM. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:2047. [Google Scholar]; (c) Tietze LF, Schünke C. Eur J Org Chem. 1998:2089. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sashuk V, Ignatowska J, Grela K. J Org Chem. 2004;69:7748. doi: 10.1021/jo049158i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Mortreux A, Blanchard M. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1974:786. [Google Scholar]; (b) Mortreux A, Dy N, Blanchard M. J Mol Catal. 1975/1976;1:101. [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Schrock RR, Clark DN, Sancho J, Wengrovius JH, Rocklage SM, Pedersen SF. Organometallics. 1982;1:1645. [Google Scholar]; (b) Schrock RR. Polyhedron. 1995;14:3177. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bindl M, Stade R, Heilmann EK, Picot A, Goddard R, Fürstner A. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:9468. doi: 10.1021/ja903259g.Another catalyst has been recently reported, but was not investigated. See: Heppekausen J, Stade R, Goddard R, Fürstner A. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:11045. doi: 10.1021/ja104800w.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.