Abstract

Background

The majority (∼75%) of cow's milk-allergic children tolerate extensively heated-(baked-) milk products. Long-term effects of inclusion of dietary baked-milk have not been reported.

Objective

We report on the outcomes of children who incorporated baked-milk products into their diets.

Methods

Children evaluated for tolerance to baked-milk (muffin) underwent sequential food challenges to baked-cheese (pizza) followed by unheated-milk. Immunologic parameters were measured at challenge visits. The comparison group were matched to active subjects (using age, sex, and baseline milk-specific IgE) to evaluate the natural history of tolerance development.

Results

Over a median of 37 months (range 8-75 months), 88 children underwent challenges at varying intervals (range 6-54 months). Among 65 subjects initially tolerant to baked-milk, 39 (60%) now tolerate unheated-milk, 18 (28%) tolerate baked-milk/baked-cheese and 8 (12%) chose to avoid milk strictly. Among the baked-milk-reactive subgroup (n=23), 2 (9%) tolerate unheated-milk, 3 (13%) tolerate baked-milk/baked-cheese, while the majority (78%) avoid milk strictly. Subjects who were initially tolerant to baked-milk were 28 times more likely to become unheated-milk-tolerant compared to baked-milk-reactive subjects (P<.001). Subjects who incorporated dietary baked-milk were 16 times more likely than the comparison group to become unheated-milk-tolerant (P<.001). Median casein IgG4 levels in the baked-milk-tolerant group increased significantly (P<.001); median milk IgE values did not change significantly.

Conclusions

Tolerance of baked-milk is a marker of transient IgE-mediated cow's milk allergy whereas reactivity to baked-milk portends a more persistent phenotype. The addition of baked-milk to the diet of children tolerating such foods appears to accelerate development of unheated-milk tolerance compared to strict avoidance.

Clinical implications

Addition of dietary baked-milk is safe, convenient, and well-accepted by patients. Prescribing baked-milk products to milk-allergic children represents an important shift in the treatment paradigm for milk allergy.

Capsule summary

The majority of cow's milk-allergic children tolerate extensively baked-milk products, which is a marker of transient IgE-mediated cow's milk allergy. Dietary baked-milk appears to accelerate development of unheated-milk tolerance compared to strict avoidance.

Keywords: cow's milk allergy, milk allergy, tolerance, extensively heated, baked, immunotherapy, immunomodulation

Introduction

Cow's milk is the most common childhood food allergen, affecting approximately 1-3% of young children1,2 and is responsible for up to 13% of fatal food-induced anaphylaxis.3 Studies have differed in methodology, but tolerance appears to be slower to develop.4–10 Bishop et al7 prospectively followed 100 children with challenge-proven milk allergy. Findings were published in 1990; tolerance was achieved in 78% by age 6 years. By 2007, resolution was considerably delayed; tolerance was achieved in 79% of children in a specialty practice by age 16 years.10 The mechanism of tolerance induction remains unclear.

Individuals with transient milk allergy produce IgE-antibodies primarily directed at conformational epitopes (dependent on the protein's tertiary structure) whereas those with persistent allergy also produce IgE-antibodies against sequential epitopes, which are heat-stable.11–15 Greater IgE-epitope diversity and higher IgE affinity are associated with more severe milk allergy.16 Since high temperatures (baking) reduce allergenicity by destroying conformational epitopes of milk proteins, we hypothesized that children with transient milk allergy would tolerate baked-milk products. We found that the majority (75%) of children with milk allergy tolerate baked-milk products (e.g., muffins, waffles). 17 None of the baked-milk-tolerant children received epinephrine for reactions during unheated-milk challenges. In contrast, 35% of baked-milk-reactive children received epinephrine for anaphylaxis during baked-milk (muffin) challenges. Based on these observations, we proposed two phenotypes of IgE-mediated milk allergy. The mild phenotype was tolerant of baked-milk products but not unheated-milk whereas the more severe phenotype was baked-milk-reactive.

We subsequently hypothesized that children with the milder phenotype of milk allergy (baked-milk–tolerant) would be able to ingest baked-milk products daily, thus benefiting from improved nutrition and dietary variety without negative effects on tolerance development to unheated-milk.

Methods

Participants

Subjects were recruited from the Mount Sinai Pediatric Allergy clinics from June 2004 to October 2007. The study was approved by the Mount Sinai Institutional Review Board and informed consent obtained. Eligible individuals were ages 0.5-21 years, had positive skin prick tests (SPT) or detectable serum milk-specific IgE, and a history of an allergic reaction to milk within 6 months prior to study entry; or milk-specific IgE levels or SPT >95% predictive for clinical reactivity (if ≤2 years old, a level >5 kUA/L; if >2 years old, a level >15 kUA/L18–19; SPT wheal diameter ≥8 mm20,21). Exclusion criteria included negative SPT and undetectable milk-specific IgE; unstable asthma, allergic rhinitis or atopic dermatitis; previously diagnosed milk-induced eosinophilic gastroenteropathy; a recent reaction (within 6 months) to a baked-milk product; or pregnancy.

Design

Active Group

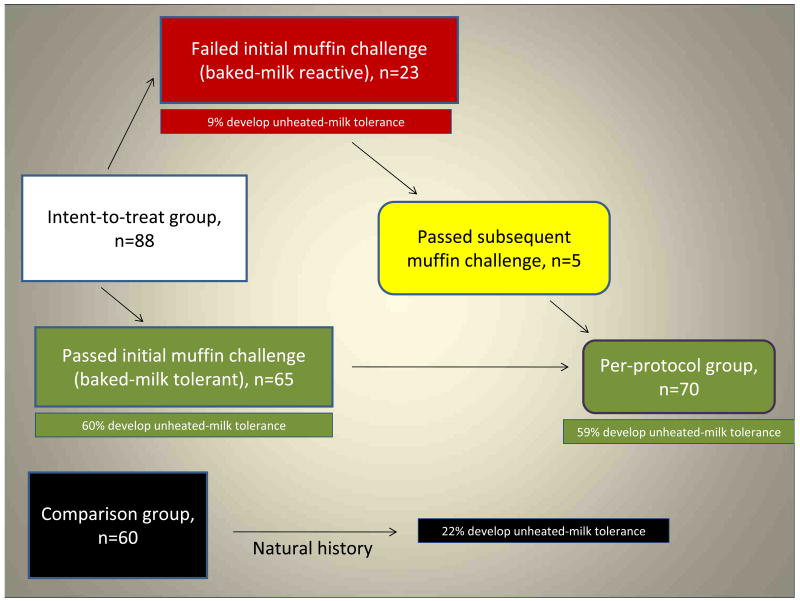

Based on the initial baked-milk oral challenge, subjects were categorized as baked-milk–reactive or baked-milk–tolerant17 (Fig 1). Baked-milk–reactive subjects were instructed to completely avoid all forms of milk but were offered a repeat challenge ≥6 months from the initial challenge. Baked-milk–tolerant subjects were instructed to incorporate baked-milk products daily into their diets and after ≥6 months were offered challenges to baked-cheese products. Similarly, after ≥6 months, baked-cheese-tolerant children were offered challenges to unheated-milk.

FIG 1. Flow diagram of study participants.

Baked-milk

Each muffin contained 1.3g milk protein (nonfat dry milk powder; Nestle Carnation, Glendale, CA). The muffin was baked at ≥350°F for 30 minutes. Baked-milk–tolerant subjects were instructed to ingest 1-3 servings per day of store-bought baked-milk products with milk listed as a minor ingredient or home-baked products with an equivalent amount of milk protein.

Baked-cheese

Amy's cheese pizza (Amy's Kitchen, Inc., Petaluma, CA), containing 4.6g of milk protein, was baked at 425°F for ≥13 minutes. Baked-cheese-tolerant subjects were instructed to eat any type of well-cooked pizza 4-7 times weekly, limited to one daily serving.

Unheated-milk

Challenges were performed with skim milk totaling 240mL (or other product containing 8-10g unheated milk protein, e.g. yogurt).

Comparison group

The original protocol was designed to have a prospective control group, such that all baked-milk-tolerant subjects would be randomly assigned to introduce dietary baked-milk or practice strict avoidance, but recruitment was unsuccessful, failing to enroll a single subject over one year. Therefore, a comparison group was retrospectively gathered consisting of subjects who fulfilled inclusion criteria but were not initially challenged to baked-milk products. This group reflects current “standard of care,” representing how children with cow's milk allergy are traditionally managed in the clinical setting.

Follow-up allergy evaluations

Serum samples were collected for the measurement of IgE and IgG4 antibodies to milk, casein, and β-lactoglobulin via UniCAP® (Phadia, Uppsala, Sweden). Unblinded food challenges were performed under physician supervision in the Clinical Research Unit. Muffin and pizza were administered in 4 equal portions over 1 hour. Unheated-milk was administered in gradually increasing doses. Subjects were monitored throughout and for 2-4 hours after completion of the challenge. Challenges were discontinued at the first objective sign of reaction, and treatment was initiated immediately. Anthropometric measurements (weight and height percentiles and Z-scores) and intestinal permeability (measured as a ratio of urinary excretion of lactulose and mannitol) were monitored for 12 months in the active group as previously described.17

Statistics

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS® 9.2 (Cary, NC, USA). Wilcoxon's signed rank test was used to compare medians of continuous measures while the two-sample Chi-Square test (and Fisher's exact test when the expected cell count was less than 5) was used to compare distributions of categorical measures between various patient groups. Regression models with discrete outcomes using a generalized logit link function were used to estimate odds ratios, corresponding 95% confidence intervals and p-values. Probabilities of unheated-milk tolerance were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier product limit method with comparison between groups evaluated by the Log-rank statistic. The Cox proportional hazards model was used to estimate hazard ratios, corresponding 95% confidence intervals and p-values. Immunologic responses over time were compared between various patient groups using mixed models with random intercepts and unstructured variance/covariance parameters. These mixed models were used to account for the correlation among immunologic response measures taken over time within a subject. An analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was performed to compare the change from baseline to last visit between patient groups while adjusting for baseline measures. For the mixed modeling, immunologic responses were natural log-transformed to render them normally distributed. For the ANCOVA modeling, the analysis was performed on the ranked data.

Intent to treat vs. per protocol analysis

The intent-to-treat analysis includes 88 subjects who underwent the initial baked-milk challenge, were available for follow-up, and either reacted to baked-milk, reacted to unheated-milk, or tolerated baked-milk but had immunologic indications of >95% risk of reaction to unheated-milk.18–21 The per-protocol analysis includes those subjects (n=70) who underwent ‘treatment,’ i.e. added dietary baked-milk (Fig 1).

Results

Unheated-milk tolerance within active group

Eighty-nine children (median age 6.6 years, range 2.1–17.3 years) were enrolled;17 one subject was not followed beyond baseline. Over a median of 37 months (range 8-75 months), 88 children were challenged to progressively less heated forms of milk at varying intervals (range 6-54 months). Among 88 “active” children, 41 (47%) now tolerate unheated-milk, 21 (24%) tolerate some form of baked-milk/baked-cheese in their diet, and 26 (30%) avoid all forms of milk (Table I, intent-to-treat).

TABLE I. Follow-up status of milk allergy.

| Final follow-up status | Initially baked-milk tolerant (n=65) | Initially baked-milk reactive (n=23) | Active Intent-to-treat (n=88) | Active Per-protocol (n=70) | Comparison (n=60) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unheated-milk tolerant | 39 (60%) | 2 (9%) | 41 (47%) | 41 (59%) | 13 (22%) |

| Baked-milk/cheese tolerant | 18 (28%) | 3 (13%) | 21 (24%) | 21 (30%) | 13 (22%) |

| Avoiding strictly | 8 (12%) | 18 (78%) | 26 (30%) | 8 (11%) | 34 (56%) |

Unheated-milk tolerance within active group stratified by initial baked-milk challenge outcome

Among 88 children, 65 (74%) tolerated their initial muffin challenge (Table I). Among this initially baked-milk-tolerant subgroup, the majority (60%) developed tolerance to unheated-milk over the 5-year follow-up period. Despite tolerating their initial baked-milk challenge, 8 subjects (12%) later chose to avoid all forms of milk for a variety of reasons. One subject's family reported it became ‘easier to avoid’ all milk products. Due to anxiety about possible reactions, another subject refused to incorporate baked-milk products into his diet. The remainder reported symptoms to lesser heated forms of milk products. Two failed unheated-milk challenges, one required epinephrine during a pizza challenge, and another (non-egg allergic) reacted to mozzarella in an omelet (throat ‘numb,’ vomiting within 5 minutes). Two others developed mild oral symptoms to undercooked waffle and pizza respectively. It is important to note that no subjects reacted to properly cooked foods previously tolerated during challenges. Repeat baked-milk challenges to re-establish non-reactivity were subsequently declined by these families.

Among the initially baked-milk-reactive subgroup (n=23), only 2 (9%) developed tolerance to unheated-milk, while 78% (n=18) continued strict milk avoidance (Table I). Of these 18, six failed subsequent baked-milk challenges performed 23-54 months after baseline. One subject failed a total of 4 muffin challenges over 5 years. Three subjects did not repeat baked-milk challenges due to anxiety; three others retained persistently high milk-specific IgE levels or large SPT wheal sizes and were not re-challenged. The remainder reported interim reactions to accidental ingestions.

Overall, baked-milk-tolerant subjects were 28 times more likely to become tolerant to unheated-milk (compared to subjects strictly avoiding) than baked-milk-reactive subjects (odds ratio 27.8, 95% confidence interval [4.8, 162.7], P<.001, Table II).

TABLE II. Table of odds ratios for tolerance, comparing baked-milk tolerant vs. baked-milk reactive groups.

| Final follow-up status | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Unheated-milk tolerant vs. avoiding strictly | 27.8 [4.8, 162.7] | <.001 |

| Baked-milk/cheese-tolerant vs. avoiding strictly | 8.7 [1.8, 43.5] | .008 |

Unheated-milk tolerance within comparison group

Sixty children were identified as age-, sex-, and baseline milk-specific IgE-matched controls. The median age of the comparison group was 5.4 years (range 2.2–17.0 years), not statistically different from the active group (data not shown). If unheated-milk challenges were offered, they were performed as part of their routine care. At follow-up (median 40 months, range 2-71 months), 13 (22%) tolerated unheated-milk, of whom 8 demonstrated non-reactivity to unheated-milk in an unblinded oral challenge at the Mount Sinai Pediatric Allergy clinic; the remainder reported at least weekly ingestion of cow's milk, yogurt, or ice cream. In addition, 13 (22%) tolerated baked-milk/baked-cheese, and 34 (56%) continued to avoid all milk (Table I). Those reporting tolerance to baked-milk/baked cheese introduced these foods after asymptomatic inadvertent ingestions.

Unheated-milk tolerance development in the per-protocol vs. comparison groups

Forty-one active subjects (59%) developed unheated-milk tolerance in contrast to 13 subjects (22%) in the comparison group (Table I). Subjects who underwent active treatment (per-protocol, which excludes those with persistent baked-milk reactivity) were 16 times more likely than the comparison group to become unheated-milk-tolerant (P<.001, Table III2), using those subjects practicing strict milk avoidance as a reference group. The significance is maintained even after inclusion of those who were unable to undergo treatment, P<.04 (intent-to-treat vs. comparison, Table III).

TABLE III. Table of odds ratios for Tolerance, comparing active vs. comparison groups.

| Final follow-up status | Per protocol vs. Comparison OR (95% CI) | P-value | Intent-to-treat vs. Comparison OR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unheated-milk tolerant vs. avoiding strictly | 16.2 [5.2, 50.5] | <.001 | 5.8 [2.3, 14.9] | <.001 |

| Baked-milk/cheese-tolerant vs. avoiding strictly | 7.9 [2.5, 24.7] | <.001 | 2.8 [1.1, 7.2] | .03 |

Per protocol group consists of children in active group who were or developed non-reactivity to baked-milk over the length of the study. Intent to treat group consists of all subjects enrolled in active arm of study, including baked-milk reactive subjects.

Intent-to-treat group consists of all subjects enrolled in active arm of study, including baked-milk reactive subjects.

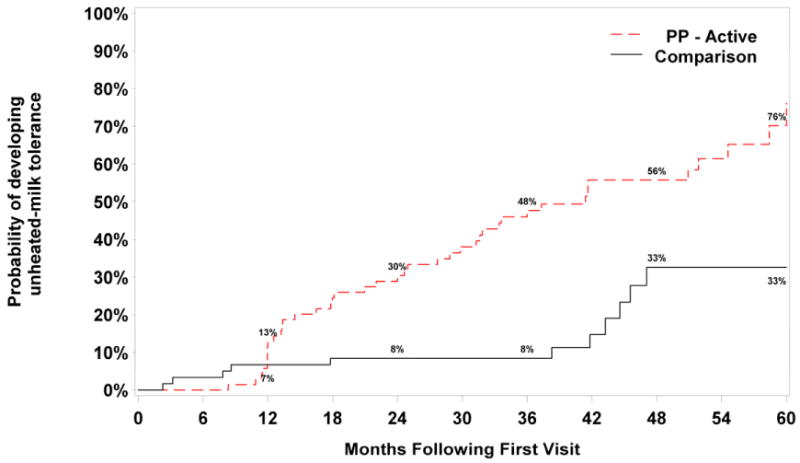

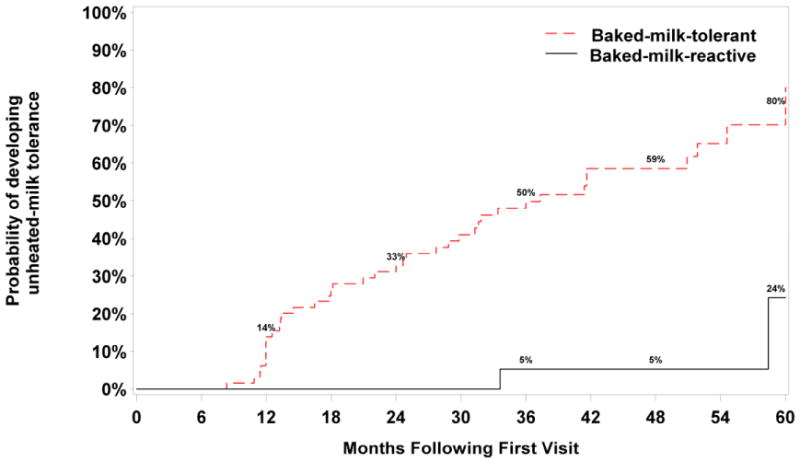

Time to tolerance of unheated-milk

In the per-protocol group (n= 70), the probability of developing unheated-milk tolerance within 60 months was 76%. In the comparison group (n=60), this probability was 33% (Fig 2). More striking, however, was the difference between the initially baked-milk-tolerant and initially baked-milk-reactive subjects. Among subjects initially tolerant to baked-milk (n=65), the probability of developing unheated-milk tolerance within 60 months was 80% (Fig 3). In contrast, this probability was only 24% among subjects initially baked-milk-reactive.

FIG 2. Development of tolerance: per-protocol vs. comparison groups.

Footnote: Log-rank p-value comparing survival between per-protocol vs. comparison groups is P<.001. Subjects in the per-protocol group were 3.6 times more likely to develop unheated-milk tolerance than subjects in the comparison group over the follow-up period; HR=3.57 [1.78, 7.16] P<.001, adjusted for sex, age at initial visit, and baseline milk-specific IgE. We present data graphically up to 60 months because beyond 60 months, the confidence intervals were very wide due to the large number of censored data.

FIG 3. Development of tolerance in active group stratified by initial baked-milk challenge: tolerant vs. reactive.

Footnote: Log-rank p-value comparing time to development of tolerance between the initially baked-milk-tolerant vs. initially baked-milk-reactive groups is P<.001. Subjects who were initially baked-milk-tolerant are 7.6 times more likely to develop unheated-milk tolerance than subjects who were initially baked-milk-reactive over the follow-up period; HR=7.62 [1.75, 33.14] P=.007, adjusted for sex, age at initial visit, and baseline milk-specific IgE. We present data graphically up to 60 months because beyond 60 months, the confidence intervals were very wide due to the large number of censored data.

Severity of symptoms during failed oral food challenges

During the follow-up period, 172 challenges were performed, only 10% of which were completed in subjects initially baked-milk-reactive. Among 172 subsequent challenges, epinephrine was administered during challenges at a higher rate among the baked-milk-reactive group than the baked-milk-tolerant group (17% vs. 3%, P=0.04, Table IV). Overall, 6 subjects developed mild-moderate anaphylaxis during 8 challenges, 2 subjects twice to the same food: one to muffin (54 months apart) and the other to pizza (9 months). Three different subjects developed anaphylaxis (wheeze and/or cough) after ingestion of 100% of the serving, which was pizza in all 3 cases.

TABLE IV. Follow-up oral challenge outcomes and treatment.

| Total (n=88) | Initially baked-milk tolerant (n=65) | Initially baked-milk reactive (n=23) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| # Challenges performed | 172 | 154 (90%) | 18 (10%) | <.001 |

| # Failed (%) | 58 (34%) | 47 (31%) | 11 (61%) | .009 |

| # Treated with epinephrine (%) | 8 (4.7%) | 5 (3.2%) | 3 (17%) | .04 |

Immunologic responses over time

After adjusting for baseline milk IgE, median milk-specific IgE levels from baseline to final visits (Table E1) were not significantly different between the per-protocol (2.6 to 1.5 kUA/L) and comparison (5.40 to 5.41 kUA/L) groups (P=.09). However, both casein IgE and β-lactoglobulin IgE values in the baked-milk-tolerant group decreased significantly over time (P<.001 and P=.02, respectively).

Median casein IgG4 values from baseline to final visits in the initially baked-milk-tolerant group increased significantly over time (0.6 to 1.3 mgA/L, P<.001, Table E2). In contrast, β-lactoglobulin IgG4 values in the baked-milk-tolerant group did not change significantly over time (P=.07).

Casein IgE/IgG4 and β-lactoglobulin IgE/IgG4 ratios in the baked-milk-tolerant group decreased significantly over time (P=.001 and P<.001, respectively).

Safety of dietary baked-milk

There was no increase in severity of chronic asthma, atopic dermatitis, or allergic rhinitis among baked-milk-tolerant children ingesting baked-milk products. The anthropometric parameters and intestinal permeability17 did not differ from baseline to 12 months (data not shown). Two male subjects (3.1%) in the active group developed eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). One was baked-milk-reactive and already strictly avoiding milk at the time of diagnosis. Another developed EoE after “passing” his unheated-milk challenge. Milk in all forms was removed for a period of time without improvement of EoE; thereafter he safely resumed ingesting unheated cow's milk products. Five (8.3%) subjects in the comparison group reported EoE, which developed while avoiding milk strictly.

Discussion

Cow's milk is the most common food allergen among children. Currently, there is no cure for food allergy. The standard of care focuses on strict dietary avoidance,1 which is extremely difficult but has been the cornerstone of food allergy therapy for decades. The advice is practical because the amount of allergen necessary to induce an allergic reaction varies22 and the severity of reactions is unpredictable.23 Additionally, there has been the theory that lack of exposure will result in deletion of immunologic memory.24 Thus, children diagnosed with milk allergy were often advised by physicians to stop ingestion of baked-milk products despite previous non-reactivity to repeated ingestions of such foods.

Our study demonstrates that (1) tolerance to baked-milk products is a marker of mild, transient IgE-mediated cow's milk allergy whereas baked-milk reactivity portends a more severe, persistent phenotype and (2) 60% of baked-milk-tolerant children ingesting baked-milk products will develop unheated-milk tolerance at a significantly accelerated rate compared to subjects prescribed strict milk avoidance. This is further supported by immunologic measures; casein IgG4 values in the baked-milk-tolerant group increased significantly, which is consistent with children spontaneously outgrowing milk allergy26–28 and children treated with milk oral immunotherapy (OIT).29–32 Moreover, diets inclusive of baked-milk products were easily implemented and had no adverse effects on growth or intestinal permeability.

There is a subset of milk-allergic patients in whom strict avoidance is clearly necessary, as approximately 25% of children were initially baked-milk-reactive. In addition, approximately 10% of our cohort who passed their initial muffin challenge later stopped treatment due to reactions to lesser cooked forms of milk, highlighting the challenges of strict adherence to proper food preparation. Still, the vast majority of baked-milk-tolerant subjects successfully introduced baked-milk products into their diets.

Non-reactivity to foods (“desensitization”) has been demonstrated in milk OIT,29–32 a treatment approach that includes gradually increasing, monitored administration of allergen over months to years. However, OIT's potential to induce permanent oral tolerance has not been established. 33 Moreover, adverse reactions are common. In a double-blind, placebo-controlled study of milk OIT, all active subjects experienced at least 1 adverse event, and 45% of active doses resulted in reactions.31 Thus, we propose that for 75% of children with milk allergy, ingestion of baked-milk products is a safer, more convenient, less costly, and less labor-intensive form of immunotherapy.

Over the past two decades, there has been an apparent increase in prevalence of food allergy and anaphylaxis2 as well as progressive delays in the development of tolerance in milk-allergic children. As suggested by this study, withdrawing small amounts of baked-milk from diets may play a role in delaying tolerance development. Moreover, strict milk avoidance can have negative effects on nutrition34, 35 and quality of life36–39 by vastly limiting the variety of food products in the diet. We have demonstrated that the addition of baked-milk products into the diet of baked-milk-tolerant subjects has a therapeutic role in accelerating tolerance development. Our findings also potentially impact children with egg allergy because similar effects of heating on egg allergenicity were described.11,40 The effect of heat on allergenicity, however, is variable and food-dependent; for peanut (dry-roasting)41 and shrimp (boiling),42 high temperatures appear to increase allergenicity.

In conclusion, tolerance of baked-milk products by children with IgE-mediated cow's milk allergy is a favorable prognostic indicator for tolerance development to unheated-milk. More importantly, the addition of baked-milk products to the diet appears to markedly accelerate the development of tolerance to unheated-milk compared to a strict avoidance diet, which currently is the “standard of care.” Moreover, addition of dietary baked-milk is safe, convenient, and well-accepted by patients. Prescribing baked-milk products to milk-allergic children represents an important shift in the treatment paradigm for milk allergy. Given the risk of anaphylaxis in children who react to baked-milk products, addition of such foods should be performed under the supervision of a physician with expertise in food allergy.

Supplementary Material

Table E1: Change in milk-specific IgE levels between initial and final visit: per-protocol vs. comparison groups

Footnote: Results of rank ANCOVA to compare baseline adjusted mean change in specific IgE (Final – Initial): P=.09

Table E2: Changes in milk-specific IgG4 levels between initial and final visit: baked-milk-tolerant vs. baked-milk-reactive groups

Footnote: Results of rank ANCOVA to compare baseline adjusted mean change in casein IgG4 (Final - Initial): P <.001

Clinical Implications.

Addition of dietary baked-milk is safe, convenient, and well-accepted by patients. Prescribing baked-milk products to milk-allergic children represents an important shift in the treatment paradigm for milk allergy.

Acknowledgments

We thank Beth Strong for research coordination; Marion Groetch, RD for dietary counseling; nursing staff of the Clinical Research Unit; Ramon Bencharitiwong and Michelle Mishoe for laboratory technical assistance; and Dr. Jim Godbold from Mount Sinai School of Medicine, Department of Biostatistics for assistance with statistical analysis. Lastly, we thank the participants and their families who have made this study possible.

Funding: The project was supported by AI 44236 from the NIAID and in part by Grant Number CTSA ULI RR 029887 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NCRR or NIH.

Abbreviations used

- CI

confidence interval

- EoE

eosinophilic esophagitis

- HR

hazard ratio

- OIT

oral immunotherapy

- OR

odds ratio

- SPT

skin prick test

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: All authors report no conflict of interest related to this study.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Boyce J, Assa'ad AH, Burks AW, et al. Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Food Allergy in the United States: Summary of the NIAID Sponsored Expert Panel Report. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:S1–S58. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Branum AM, Lukacs SL. Food Allergy Among Children in the United States. Pediatrics. 2009;124:1549–55. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bock SA, Muñoz-Furlong A, Sampson HA. Further fatalities caused by anaphylactic reactions to food, 2001-2006. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:1016–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.12.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sicherer SA, Sampson HA. Food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:S116–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Host A, Halken S. A prospective study of cow milk allergy in Danish infants during the first 3 years of life. Allergy. 1990;45:587–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1990.tb00944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Host A. Frequency of cow's milk allergy in childhood. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2002;89:33–7. doi: 10.1016/s1081-1206(10)62120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bishop JM, Hill DJ, Hosking CS. Natural history of cow milk allergy: clinical outcome. J Pediatr. 1990;116:862–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80641-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wood RA. The natural history of food allergy. Pediatrics. 2003;111:1631–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cantani A, Micera M. Natural history of cow's milk allergy: an eight-year follow-up study in 115 atopic children. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2004;8:153–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skripak JM, Matsui EC, Mudd K, Wood RA. The natural history of IgE-mediated cow's milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:1172–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooke SK, Sampson HA. Allergenic properties of ovomucoid in man. J Immunol. 1997;159:2026–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chatchatee P, Jarvinen KM, Bardina L, Vila L, Beyer B, Sampson HA. Identification of IgE and IgG binding epitopes on beta- and kappa-casein in cow's milk allergic patients. Clin Exp Allergy. 2001;31:1256–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2001.01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vila L, Beyer K, Jarvinen KM, Chatchatee P, Bardina L, Sampson HA. Role of conformational and linear epitopes in the achievement of tolerance in cow's milk allergy. Clin Exp Allergy. 2001;31:1599–1606. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2001.01218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jarvinen KM, Beyer K, Vila L, Chatchatee P, Busse PJ, Sampson HA. B-cell epitopes as a screening instrument for persistent cow's milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;110:293–7. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.126080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Busse PJ, Jarvinen KM, Vila L, Beyer B, Sampson HA. Identification of sequential IgE-binding epitopes on bovine alpha(s2)-casein in cow's milk allergic patients. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2002;129:93–6. doi: 10.1159/000065178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang J, Lin J, Bardina L, et al. Correlation of IgE/IgG4 milk epitopes and affinity of milk-specific IgE antibodies with different phenotypes of clinical milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:695–702. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Bloom KA, Sicherer SH, et al. Tolerance to extensively heated milk in children with cow's milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:342–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garcia-Ara C, Boyano-Martinez T, Diaz-Pena JM, Martin-Munoz F, Reche-Frutos M, Martin-Esteban M. Specific IgE levels in the diagnosis of immediate hypersensitivity to cows' milk protein in the infant. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107:185–90. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.111592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sampson HA. Utility of food-specific IgE concentrations in predicting symptomatic food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107:891–6. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.114708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hill DJ, Hosking CA, Reyes-Benito LV. Reducing the need for food allergen challenges in young children: a comparison of in vitro with in vivo tests. Clin Exp Allergy. 2001;31:1031–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2001.01113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sporik R, Hill DJ, Hosking CS. Specificity of allergen skin testing in predicting positive open food challenges to milk, egg and peanut in children. Clin Exp Allergy. 2000;30:1540–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2000.00928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flinterman AE, Pasmans SG, Hoekstra MO, et al. Determination of no-observed adverse-effect levels and eliciting doses in a representative group of peanut-sensitized children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:448–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bock SA, Munoz-Furlong A, Sampson HA. Further fatalities caused by anaphylactic reactions to food, 2001-2006. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:1016–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.12.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bock SA, Munoz-Furlong A, Sampson HA. Fatalities due to anaphylactic reactions to foods. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107:191–3. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.112031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim JS, Sicherer SH. Should food avoidance be strict in prevention and treatment of food allergy? Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;10:252–7. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e328337bd3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sicherer SH, Sampson HA. Cow's milk protein-specific IgE concentrations in two age groups of milk-allergic children and in children achieving clinical tolerance. Clin Exp Allergy. 1999;29:507–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.1999.00520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shek LP, Soderstrom L, Ahlstedt S, Beyer K, Sampson HA. Determination of food specific IgE levels over time can predict the development of tolerance in cow's milk and hen's egg allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:387–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Savilahti EM, Rantanen V, Lin JS, et al. Early recovery from cow's milk allergy is associated with decreasing IgE and increasing IgG4 binding to cow's milk epitopes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:1315–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Staden U, Rolinck-Werninghaus C, Brewe F, Wahn U, Niggemann B, Beyer K. Specific oral tolerance induction in food allergy in children: efficacy and clinical patterns of reaction. Allergy. 2007;62:1261–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Longo G, Barbi E, Berti I, et al. Specific oral tolerance induction in children with very severe cow's milk-induced reactions. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:343–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Skripak JM, Nash SD, Rowley H, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of milk oral immunotherapy for cow's milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:1154–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Narisety SD, Skripak JM, Steele P, et al. Open-label maintenance after milk oral immunotherapy for IgE-mediated cow's milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:610–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Sampson HA. Future therapies for food allergies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.12.1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Christie L, Hine RJ, Parker JG, Burks W. Food allergies in children affect nutrient intake and growth. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102:1648–51. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90351-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tiainen JM, Nuutinen OM, Kalavainen MP. Diet and nutritional status in children with cow's milk allergy. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1995;49:605–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Primeau M, Kagan R, Joseph L, et al. The psychological burden of peanut allergy as perceived by adults with peanut allergy and the parents of peanut-allergic children. Clin Exp Allergy. 2000;30:1135–43. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2000.00889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sicherer SH, Noone SA, Munoz-Furlong A. The impact of childhood food allergy on quality of life. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2001;87:461–4. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)62258-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Avery NJ, King RM, Knight S, Hourihane JO'B. Assessment of quality of life in children with peanut allergy. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2003;14:378–82. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3038.2003.00072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bollinger ME, Dahlquist LM, Mudd K, et al. The impact of food allergy on the daily activities of children and their families. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;96:415–21. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60908-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lemon-Mule H, Sampson HA, Sicherer HA, et al. Immunologic changes in children with egg allergy ingesting extensively heated egg. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:977–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beyer K, Morrow E, Li XM, et al. Effects of cooking methods on peanut allergenicity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107:1077–81. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.115480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carnés J, Ferrer A, Huertas AJ, Andreu C, Larramendi CH, Fernández-Caldas E. The use of raw or boiled crustacean extracts for the diagnosis of seafood allergic individuals. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007;98:349–54. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60881-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table E1: Change in milk-specific IgE levels between initial and final visit: per-protocol vs. comparison groups

Footnote: Results of rank ANCOVA to compare baseline adjusted mean change in specific IgE (Final – Initial): P=.09

Table E2: Changes in milk-specific IgG4 levels between initial and final visit: baked-milk-tolerant vs. baked-milk-reactive groups

Footnote: Results of rank ANCOVA to compare baseline adjusted mean change in casein IgG4 (Final - Initial): P <.001