Abstract

The mammalian bombesin (Bn)-receptor family[gastrin-releasing peptide-receptor(GRPR-receptor), neuromedin B-receptor(NMB-receptor)], their natural ligands,GRP/NMB, as well as the related orphan-receptor,BRS-3, are widely-distributed, and frequently overexpressed by tumors. There is increased interest in agonists for this receptor family to explore their roles in physiological/pathophysiological processes, and for receptor-imaging/cytotoxicity in tumors. However, there is minimal data on human pharmacology of Bn-receptor agonists and most results are based on nonhuman receptor studies, particular rodent-receptors, which with other receptors frequently differ from human-receptors. To address this issue we compared hNMB/GRP-receptor affinities and potencies/efficacies of cell-activation(assessing phospholipase C activity) for 24 putative Bn-agonists(12-natural,12-synthetic) in four different cells with these receptors, containing native-receptors or receptors expressed at physiological densities, and compared the results to native rat-GRP-receptor-containing cells-(AR42J–cells) or rat-NMB-receptor cells(C6-glioblastoma cells). There were close correlations(r=0.92–99,p<0.0001) between their affinities/potencies for the two hGRP- or hNMB-receptor cells. Twelve analogues had high affinities(≤ 1 nM) for hGRP-receptor with 15 selective for it(greatest=GRP,NMC), 8 had high affinity/potencies for hNMB-receptors and 4 were selective for it. Only synthetic Bn-analogues containing β−alanine11 had high affinity for hBRS-3, but t also had high affinities/potencies for all GRP-/hNMB-receptor cells. There was no correlation between affinities for human-GRP-receptors and rat-GRP-receptors(r=0.131,p=0.54), but hNMB-receptor results correlated with rat-NMB-receptor(r=0.71, p<0.0001). These results elucidate the human- and rat-GRP-receptor pharmacophore for agonists differ markedly,whereas they do not for NMB-receptors, therefore potential GRP-receptor agonists for human studies(such as Bn-receptor-imaging/cytotoxicity) must be assessed on human-Bn-receptors. The current study provides affinities/potencies on a large number of potential agonists that might be useful for human studies.

Keywords: Bombesin, neuromedin B, gastrin-releasing peptide, bombesin receptor, gastrin-releasing peptide receptor, BRS-3, neuromedin B receptor, satiety, peptide mediated cytotoxicity, tumor imaging, PRRT

1. Introduction

The mammalian bombesin (Bn) receptor family consists of three closely-related G protein-coupled receptors: the gastrin-releasing peptide receptor (GRP receptor) whose native ligand is the 27 amino acid peptide, GRP; the neuromedin B receptor (NMB receptor) mediating the action of the decapeptide, NMB, and the orphan receptor, BRS-3 which shares 47–51% protein homology with the GRP/NMB receptors, but whose native ligand is still unknown [7,12,19,29,41,95]. Each of these receptors as well as their ligands are widely distributed in both the central nervous system [CNS] and peripheral tissues [7,29,34,36,56,78].

Studies in animals suggest these receptors are involved in a broad range of physiological and pathophysiological processes [19,29,36,41,95]. The possible physiological effects include roles in regulation in the CNS/peripheral nervous system [thermoregulation, behavior, circadian rhythm, satiety, sensory nerve transmission], in the gastrointestinal tract [secretion, motility, growth], endocrine [energy homeostasis, secretion of numerous hormones/neurotransmitters, thyrotropin release], immunological [effects on leukocytes, lymphocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells], as well as effects in the respiratory system and urogenital system [19,29,36,41,95]. Important possible pathophysiological roles include proposed roles in lung injury/diseases, tumoral growth, thyroid disorders, human feeding disorders and disorders of energy homeostasis, pruritic responses, and various human CNS disorders [19,29,41,54,70,95]. Of these latter disorders, the one that has received the most attention is the prominent role that GRP and NMB have on growth and/or differentiation of various human tumors [lung, squamous cell tumors of head/neck, prostate, colon, CNS, neuroendocrine tumors, pancreatic, gynecologic tumors], which include in some cases functioning as an autocrine growth factor [19,29,36,41,54,95]. Furthermore, the GRP/NMB receptors are two of the G protein-coupled receptors that are most frequently overexpressed by various human neoplasms including cancers of the lung [small cell and nonsmall cell], pancreas, prostate, CNS (gliomas), head/neck (squamous cell tumors), breast, colon and various neuroendocrine tumors (bronchial, intestinal, thymic carcinoids) [19,29,31,54,67,95].

Recently there is an increased interest in the use of possible Bn receptor agonists and antagonists to further define the role of Bn receptors in both human pharmacology and pathophysiology [18,19,25,29,41,70]. This is particularly true for the marked interest in the possible use of Bn receptor agonists which could be preferentially internalized by Bn receptor-overexpressing human neoplasms, for use in localizing these neoplasms as well as for their treatment, by performing Bn receptor-mediated imaging or Bn receptor mediated cytotoxicity [5,29,55,67]. This has received considerable interest because of the marked clinical success of using radiolabeled somatostatin analogues to image neuroendocrine tumors either by nuclear medicine methods or by positron emission tomographic scanning and more recently the promising results with 111In-, 90Y-, or 177Lu- labeled somatostatin analogues for treatment of advanced malignant neuroendocrine tumors by peptide radioreceptor therapy [5,19,41,66]. This increased interest in Bn receptors has occurred, because the successful results with human tumors containing overexpression of somatostatin receptors raise the possibility that a similar approach may be successful with more common neoplasms, which do not overexpress somatostatin receptors, but do overexpress human Bn receptors [5,19,41,66].

Unfortunately, at present it can be difficult to select the appropriate Bn receptor agonist to use for these human Bn receptor imaging/cytotoxicity studies as well as for other Bn receptor studies in humans. This has occurred because in contrast to Bn receptor antagonists [9,18,24,29,91,92], there have been few systematic studies of human Bn receptor pharmacology or receptor activation, especially using cellular systems containing receptor expression densities that usually occur with native Bn receptors. This has led to a reliance on results from animal studies, particularly from rodents for optimum pharmacological design. This approach can lead to inaccurate conclusions, because with a number of different G protein coupled receptors, including Bn receptors, there are reports of important species differences, especially between human and rodent receptors, on agonist receptor interaction/activation [23,27,29,35,40,68,88,92,93]. Similarly, high densities of receptors, as frequently occur with transfected cell systems, including with Bn receptors [87], can have marked effects on agonist receptor activation/interaction, leading to conclusions which may not be applicable to native cells with lower Bn-receptor densities, as seen in vivo.

The present study was performed to attempt to address these issues by systematically studying the affinities and potency of cellular activation at human Bn receptors of 24 putative agonists (12 natural and 12 synthetic Bn analogues) that either themselves or their analogues are commonly used in studies of human Bn receptors. To insure the results were representative of native Bn receptor responses two different cell lines were used, including one containing either native receptors or cells with Bn receptors expressed at the density seen in native cells. Results using human Bn cells were compared to results with cells containing native rat Bn receptors under identical experimental conditions. There was a marked discordance between results with rat GRP receptors and human, showing that data from the rat could not be used for human ligand design for hGRP receptors. A number of high affinity agonist ligands for each Bn receptor subtype could be identified which could be useful for investigating the role of GRP/NMB receptors in human physiological/pathophysiological conditions.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

The following cells and materials were obtained from the sources indicated: Balb 3T3 (mouse fibroblast) cells, HuTu-80 (human duodenal cancer cell line), AR42J cells (rat pancreatic acinar cells) and C6 rat glioblastoma cells from the American Type Culture Collection, (Rockville, MD); NCI-H1299 (non-small cell lung cancer cells) were a gift from Herb Oie (National Cancer Institute-Navy Medical Oncology Branch, Naval Medical Center, Bethesda, MD; GENETICIN selective antibiotic (G418 Sulfate) from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA); Dulbecco’s minimum essential medium (DMEM), RPMI 1640, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fetal bovine serum (FBS) and trypsin/versene solution from Biosource International (Camarillo, CA); Na125I (2,200 Ci/mmol) from Amersham Biosciences (Piscataway, NJ); 1,3,4,6-tetrachloro-3,6-diphenylglycouril (IODO-GEN) and dithiothreitol (DTT) from Pierce Biotechnology, Inc. (Rockford, IL); myo-[2-3H]Inositol (20 Ci/mmol) from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Piscataway, NJ); formic acid, ammonium formate, disodium tetraborate, soybean trypsin inhibitor, bacitracin and AG 1-X8 resin from Bio-Rad (Richmond, CA); bovine serum albumin fraction V (BSA) and N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N-2-ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) from ICN Pharmaceutical, Inc. (Aurora, OH). All other chemicals were of the highest purity commercially available.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Preparation of peptides

The peptides were synthesized using standard solid-phase methods as described previously [18,46]. In brief, solid-phase syntheses of peptide amides were carried out using Boc chemistry on methylbenzhydrylamine resin (Advanced ChemTech, Louisville, KY) followed by hydrogen fluoride-cleavage of free peptide amides. The crude peptides were purified by preparative high-performance liquid chromatography on columns (2.5 × 50 cm) of Vydac C18 silica (10 µm), which was eluted, with linear gradients of acetonitrile in 0.1% (v/v) trifluoroacetic acid. Homogeneity of the peptides was assessed by analytical reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography, and the purity was usually 97% or higher. Amino acid analysis (only amino acids with primary amino acid groups were quantitated) gave the expected amino acid ratios. Peptide molecular masses were obtained by matrix-assisted laser desorption mass spectrometry (Thermo Bioanalysis Corp., Hemel, Helmstead, UK), and all corresponded well with calculated values.

2.2.2. Growth and maintenance of cells

HuTu-80 cells, which contain native hGRPR [18,98], were grown in DMEM. Balb 3T3 cells stably expressing human NMB receptors, human GRP receptors or NCI-H1299 cells stably expressing human NMB receptor were made as described previously [3,46,75] and grown in DMEM or RPMI 1640, respectively. NCI-H1299 cells expressing low levels of hNMBR were made as described previously [18] and grown in DMEM. C6 glioblastoma cells which contain native rat NMB receptor [91,94] and AR42J natively expressing rat GRP receptors [42] were grown in DMEM. All the receptor-transfected cells were grown in their respective propagation media supplemented with supplemented 10% FBS and 300 mg/liter of G418 sulfate and incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere.

2.2.3. Preparation of 125I-[Tyr4] Bn, 125I-[D-Tyr0]NMB and 125I-[D-Tyr6,β-Ala11,Phe13,Nle14]Bn-(6–14)

Preparation of 125I-[Tyr4]Bn, 125I-[D-Tyr0]NMB and 125I-[D-Tyr6,β-Ala11,Phe13,Nle14]Bn-(6–14) at a specific activity of 2,200 Ci/ mmol was prepared by a modification of methods described previously [18,43–45]. Briefly, 0.8 µg of IODO-GEN (in 0.01 µg/ml chloroform) was transferred to a vial, dried under a stream of nitrogen, and washed with 100 µl of KH2PO4 (pH 7.4). To the reaction vial, 20 µl of 0.5 M KH2PO4 (pH 7.4), 8 µg of peptide in 4 µL of water, and 2 mCi (20 µl) Na 125I were added, mixed gently, and incubated at room temperature for 6 min. The incubation was stopped by the addition of 100 µl of distilled water. Radiolabeled peptide was separated using a Sep-Pak (Waters Associates) and high-performance liquid chromatography as described previously [46,86]. Radioligand was stored with 0.5% BSA at −20 °C.

2.2.4. Whole cell radioligand binding assays

Binding studies were performed as previously described [18,46]. Briefly, cells were incubated for 1 h at 21 °C in 250 µl of binding buffer containing 24.5 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 98 mM NaCl, 6 mM KCl, 2.5 mM KH2PO4, 5 mM sodium pyruvate, 5 mM sodium fumarate, 5 mM sodium glutamate, 2 mM glutamine, 11.5 mM glucose, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 1.0 mM MgCl2, 0.01% (w/v) soybean trypsin inhibitor, 0.2 % (v/v) amino acid mixture, 0.2% (w/v) BSA, and 0.05% (w/v) bacitracin with 50 pM 125I-[Tyr4]Bn, 125I-[D-Tyr0]NMB or 125I-[D-Tyr6, β-Ala11, Phe13, Nle14]Bn-(6–14) (2,200 Ci/mmol), respectively, in the presence of the indicated concentration of unlabeled peptides. Binding studies to C6 glioblastoma cells were performed using 50 pM 125I-[D-Tyr0]NMB as described previously [94]. Binding was performed to native GRP receptors on AR42J cell using 50 pM 125I-[Tyr4]Bn as described previously [42]. Although receptor expression over the ranges for cells used in this study [87] has been shown not to alter receptor affinity or potency under the experimental conditions used in this study, as an added precaution to correct for any differences in ligand bound by different cell line, binding results with each receptor were compared only to results with receptor containing cells binding similar amounts of ligand. This was accomplished as described previously [17,18] by varying the cell concentration between 0.05 – 2 ×106 cells/ml for each receptor so that <20% of the total added radioactive ligand was bound during the incubation and the results compared to cells transfected with native receptor adjusted in concentration to bind a similar amount of ligand. After the incubation, 100 µl aliquot were added to 400 µl microfuge tubes (PGC Scientific, Frederick, MD), which contained 100 µl of binding buffer to determine the total radioactivity. The bound tracer was separated from unbound tracer by pelleting the cells through the binding buffer by centrifugation at 10,000xg in a Microfuge E (Beckman, Fullerton, CA) for 3 min. The supernatant was aspirated and the pelleted cells were rinsed twice with a washing buffer which contained 1% (w/v) BSA in PBS. The amount of radioactivity bound to the cells was measured in a Cobra II Gamma counter (Packard Instruments, Meriden, CT). Binding was expressed as the percentage of total radioactivity that was associated with the cell pellet. All binding values represented saturable binding (i.e., total binding minus nonsaturable binding). Nonsaturable binding was defined as the amount of binding that occurred with 1 µM Bn, 1 µM NMB or 1 µM [D-Tyr6, β-Ala11, Phe13, Nle14]Bn-(6–14) in the incubation solution. Nonsaturable binding was <15% of the total binding in all experiments. Receptor density on the single colonies and the HuTu-80 cell line were determined using 0.75 nM 125I-[D-Tyr6, β-Ala11, Phe13, Nle14]Bn- (6–14). Total saturable binding was determined using 1 µM Bn and using the ligand specific activity, the cell number or the protein present to determine the receptor densities present. The results of the binding experiments were expressed as fmoles of 125I-[D-Tyr6,β-Ala11,Phe13,Nle14]Bn-(6–14) bound per 106 of cells or as fmoles bound/mg protein. Native hGRP receptor containing HuTu-80 cells had a receptor density of 1.68 ± 0.08 fmoles/106 cells (8.13 ± 0.39 fmoles/mg protein) and the hGRPR transfected Balb 3T3 cells had a receptor density of 15.16 ± 0.21 fmoles/106 cells (43.17 ± 1.0 fmoles/mg protein). The hNMBR transfected Balb 3T3 cells had a receptor density of 77 ± 6 fmoles/106 cells (162.0 ± 13.4 fmoles/mg protein) and NCI-H1299 transfected with hNMBR had a receptor density of 2.11 ± 0.20 fmoles/106 cells (4.65 ± 0.40 fmoles/mg protein).

2.2.5. Measurement of Inositol Phosphates

Changes in total [3H]inositol phosphates ([3H]IP) were measured as described previously [3,4,71,74]. Briefly, hGRPR-, hNMBR- or hBRS-3, transfected Balb 3T3, hNMBR-transfected NCI-H1299, HuTu-80 AR42J or C6 glioblastoma cells were subcultured into 24-well plates (5.0 × 104 cells/well) in regular propagation media and then incubated for 24 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. The cells were then incubated with 3 µCi/ml of myo- [2-3H] inositol in growth media supplemented with 2% FBS for an additional 24 hr. Before assay, the 24-well plates were washed by incubating for 30 min at 37°C with 1 ml/well of PBS (pH 7.0) containing 20 mM lithium chloride. The wash buffer was aspirated and replaced with 500 µl of IP assay buffer containing 135 mM sodium chloride, 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 2 mM calcium chloride, 1.2 mM magnesium sulfate, 1 mM EGTA, 20 mM lithium chloride, 11.1 mM glucose, 0.05% BSA (w/v) and incubated with or without any of the peptides studied. After 60 min of incubation at 37°C, the experiments were terminated by the addition of 1 ml of ice cold 1% (v/v) hydrochloric acid in methanol. Total [3H]IP was isolated by anion exchange chromatography as described previously [2,4,17,74]. Briefly, samples were loaded onto Dowex AG1-X8 anion exchange resin columns, washed with 5 ml of distilled water to remove free [3H]inositol, then washed with 2 ml of 5 mM disodium tetraborate/60 mM sodium formate solution to remove [3H]glycerophosphorylinositol. Two ml of 1 mM ammonium formate/100 mM formic acid solution were added to the columns to elute total [3H]IP. Each eluate was mixed with scintillation cocktail and measured for radioactivity in a scintillation counter.

2.2.6. Comparison of affinities of various peptides for human GRP and NMB receptors to rat GRP (rGRP receptors) and rat NMB receptors (rNMB receptors)

To allow a direct comparison under identical assay conditions of the affinities of these different agonists for Bn receptors on rat and human tissues, their affinities for native rGRP receptors on the rat pancreatic acinar cell line, AR42J cells [42,72] and for native rNMB receptors on the rat glioblastoma cell line, C6 glioma cells [72,91,94] was determined. The affinities were compared using regression analysis of the affinity constants as described in the statistics below.

2.2.7. Statistics

All data is expressed as means ± SEM. Each point was measured in duplicate, and each experiment was replicated at least four times. Calculation of affinities from binding studies (IC50’s) and potencies (EC50’s) from phospholipase C activation studies were performed by determining the IC50 or EC50 using the curve-fitting program KaleidaGraph (Synergy Software). The Mann Whitney U test was used to determine the statistical significance of differences. Regression analysis and calculation of the correlation coefficients and their significance was performed using a least-squares analysis and the statistical program, Statview (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

3. Results

3.1. Human Bn receptor affinities-natural occurring peptides. Affinities for same hBn receptor

In this study, we have compared the ability of a number of naturally occurring peptides as well as synthetic Bn-related peptide ligands (Table 1) that are reported to function as Bn receptor agonists in either human studies or in other species, to interact with and activate human Bn receptors [hGRPR, hNMBR, hBRS-3] and compared their affinities to those for Bn receptors of rat, a commonly used laboratory animal in various Bn receptor studies (rGRPR, rNMBR) (Tables 1–3)[3,11,29,33,38,47,52,58,69,81,97]. The different compounds could be classified in two groups; 12 have a natural origin and 12 were synthetic (Table 1). Natural peptides could be divided into Bn-related (Bn, GRP, Alytesin and NMC), NMB-related (NMB, NMB30, Rohdei-litorin, Litorin, Ranatensin and PG-L) and Phyllolitorin-related (PLL, LeuPLL) (Table 1). The synthetic peptides are various Bn and Bn(6–14) analogues (Table 1).

Table 1.

Structure of Bombesin-related peptides used in this study.

| Structure (Position relative to Bn) |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide Name/# |

Bombesin Analogue | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| Natural Peptides | |||||||||||||||

| Bombesin-related | |||||||||||||||

| Bn | Bombesin | pGlu | Gln | Arg | Leu | Gly | Asn | Gln | Trp | Ala | Val | Gly | His | Leu | Met-NH2 |

| GRP(1) | Gastrin-releasing peptide (14–27) | Met | Tyr | Pro | Arg | -(2) | - | His | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Aly | Alytesin | Gly | - | - | - | Thr | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| NMC | Neuromedin C | - | - | His | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Neuromedin B-related | |||||||||||||||

| NMB | Neuromedin B | - | - | Leu | - | - | Thr | - | - | Phe | - | ||||

| NMB30(3) | Neuromedin B (1–30) | Val | His | - | Arg | - | - | Leu | - | - | Thr | - | - | Phe | - |

| Roh-Lit | Rohdei-litorin | Glp | Leu | - | - | Thr | - | - | Phe | - | |||||

| Lit | Litorin | pGlu | - | - | - | - | - | - | Phe | - | |||||

| Ran | Ranatensin | pGlu | Val | Pro | - | - | - | - | - | - | Phe | - | |||

| PG-L | Pseudophryne güntheri litorin-like peptide | pGlu | Gly | Gly | - | Pro | - | - | - | - | - | - | Phe | - | |

| Phyllolitorin-related | |||||||||||||||

| PLL | Phyllolitorin | pGlu | Leu | - | - | - | - | Ser | Phe | - | |||||

| LeuPLL | [Leu8]phyllolitorin | pGlu | Leu | - | - | - | - | Ser | - | - | |||||

| Synthetic | |||||||||||||||

| #1 | [Leu14]Bn | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Leu-NH2 |

| #2 | [Tyr4,Nleu14]Bn | - | - | - | Tyr | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Nleu-NH2 |

| #3 | [D-Trp8,Leu14]Bn | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | D-Trp | - | - | D-Ala | - | - | Leu-NH2 |

| #4 | [D-Ala11]Bn | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | D-Ala | - | - | - |

| #5 | [N-3-Pentanyl,D-Phe6,D-Ala11,Leu14]Bn(6–14) | N-3-Pentanyl-D-Phe | - | - | - | - | D-Ala | - | - | Leu-NH2 | |||||

| #6 | [D-Phe6,D-Ala11,Leu14]Bn(6–14) | D-Phe | - | - | - | - | D-Ala | - | - | Leu-NH2 | |||||

| #7 | [D-Phe6]Bn(6–14) | D-Phe | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||||

| #8 | [D-Cys6,D-Ala11,Cys14]Bn(6–14) | D-Cys | - | - | - | - | D-Ala | - | - | Cys | |||||

| #9 | [D-Tyr6,βAla11,Phe13,Nle14]Bn(6–14) | D-Tyr | - | - | - | - | βAla | - | Phe | Nleu-NH2 | |||||

| #10 | [D-Phe6, βAla11,Phe13,Nle14]Bn(6–14) | D-Phe | - | - | - | - | βAla | - | Phe | Nleu-NH2 | |||||

| #11 | [D-Tyr6,Asn7, βAla11,Phe13, Nle14]Bn(6–14) | D-Tyr | Asn | - | - | - | βAla | - | Phe | Nleu-NH2 | |||||

| #12 | [D-Ser-Ser-D-Ser-D-Tyr6,Asn7, βAla11, Phe13, Nle14]Bn(6–14) | D-Ser- | Ser- | D-Ser- | D-Tyr | Asn | - | - | - | βAla | - | Phe | Nleu-NH2 | ||

Only GRP (14–27) structure is shown (the biologically active COOH terminus) [29,49]. However, in our experiments GRP was used [i.e. GRP (1–27)].

Indicates the amino acid in this position is the same as in Bn.

Only NMB (17–30) structure is shown (the biologically active COOH terminus). However, in our experiments both NMB and NMB30 [52] were used [i.e. NMB (1–30)].

Abbreviations: Bn, Bombesin [10]; GRP, Gastrin-releasing peptide (14–27) [49]; Aly, Alytesin; NMC, Neuromedin C; NMB, Neuromedin B [51]; Roh-Lit, Rohdei-litorin [1]; Lit, Litorin [10]; Ran, Ranatensin [10]; PG-L, Pseudophryne güntheri litorin-like peptide [81]; PLL, Phyllolitorin [58]; LeuPLL, [Leu8]phyllolitorin [58]; Nleu, Norleucine; pGlu, pyroglutamic acid; βAla, βAlanine.

Table 3.

Ability of agonists to stimulate [3H]IP generation in hGRPR Balb-3T3, HuTu-80, hNMBR Balb-3T3 and NCI-H1299 cell lines.

| EC50 (nM) |

EC50 (nM) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bombesin Analogue | Peptide Name/# |

HuTu-80 | hGRPR Balb-3T3 |

hNMBR NCI-H1299 |

hNMBR Balb-3T3 |

| Natural Peptides | |||||

| Bombesin-related | |||||

| Bombesin | Bn | 0.34 ± 0.01 | 0.72 ± 0.02 | 1.47 ± 0.07 | 0.53 ± 0.02 |

| Gastrin-releasing peptide (14–27) | GRP | 3.16 ± 0.13 | 4.79 ± 0.19 | 75.9 ± 3.11 | 56.2 ± 2.4 |

| Alytesin | Aly | 0.47 ± 0.02 | 0.52 ± 0.01 | 1.74 ± 0.04 | 0.18 ± 0.01 |

| Neuromedin C | NMC | 1.51 ± 0.10 | 4.90 ± 0.10 | 117 ± 2 | 35.5 ± 2.5 |

| Neuromedin B-related | |||||

| Neuromedin B | NMB | 354 ± 5 | 257 ± 8 | 0.63 ± 0.02 | 0.98 ± 0.06 |

| NMB30 | NMB30 | 117 ± 3 | 223 ± 1 | 2.42 ± 0.08 | 22.39 ± 0.47 |

| Rohdei-litorin | Roh-Lit | 7.08 ± 0.05 | 9.77 ± 0.29 | 1.58 ± 0.05 | 0.09 ± 0.03 |

| Litorin | Lit | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 0.44 ± 0.02 | 0.20 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.01 |

| Ranatensin | Ran | 0.23 ± 0.01 | 1.05 ± 0.02 | 1.95 ± 0.06 | 0.26 ± 0.01 |

| P-GL | PG-L | 0.19 ± 0.01 | 0.62 ± 0.03 | 1.74 ± 0.04 | 0.26 ± 0.01 |

| Phyllolitorin-related | |||||

| Phyllolitorin | PLL | 288 ± 15 | 331 ± 23 | 6.92 ± 0.19 | 0.54 ± 0.02 |

| [Leu8]phyllolitorin | LeuPLL | 89.1 ± 2.7 | 67.6 ± 2.03 | 12.6 ± 0.34 | 15.1 ± 0.70 |

| Synthetic | |||||

| [Leu14]Bn | #1 | 1.95 ± 0.09 | 1.44 ± 0.08 | 95.5 ± 3.1 | 26.3 ± 1.69 |

| [Tyr4,Nleu14]Bn | #2 | 0.43 ± 0.03 | 1.35 ± 0.02 | 11.5 ± 0.50 | 5.24 ± 0.21 |

| [D-Trp8,Leu14]Bn | #3 | 245 ± 8 | 417 ± 8 | > 1,000 | > 1,000 |

| [D-Ala11]Bn | #4 | 1.20 ± 0.08 | 1.00 ± 0.03 | 7.41 ± 0.20 | 4.89 ± 0.18 |

| [N-3-Pentanyl,D-Phe6,D-Ala11,Leu14]Bn(6–14) | #5 | 17.0 ± 1.0 | 27.5 ± 1.3 | 912 ± 22 | 933 ± 14 |

| [D-Phe6,D-Ala11,Leu14]Bn(6–14) | #6 | 1.54 ± 0.09 | 3.02 ± 0.10 | 398 ± 17 | 331 ± 14 |

| [D-Phe6]Bn(6–14) | #7 | 1.54 ± 0.12 | 0.60 ± 0.02 | 2.82 ± 0.15 | 1.44 ± 0.09 |

| [D-Cys6,D-Ala11,Cys14]Bn(6–14) | #8 | 100 ± 5 | 194 ± 11 | 1000 ± 12 | 912 ± 45 |

| [D-Tyr6,βAla11,Phe13,Nle14]Bn(6–14) | #9 | 0.26 ± 0.01 | 0.45 ± 0.02 | 1.09 ± 0.03 | 0.10 ± 0.01 |

| [D-Phe6, βAla11,Phe13,Nle14]Bn(6–14) | #10 | 0.36 ± 0.01 | 0.58 ± 0.02 | 1.20 ± 0.03 | 0.15 ± 0.01 |

| [D-Tyr6,Asn7,βAla11,Phe13, Nle14]Bn(6–14) | #11 | 0.69 ± 0.02 | 0.85 ± 0.02 | 4.57 ± 0.13 | 1.62 ± 0.03 |

| [D-Ser-Ser-D-Ser-D-Tyr6,Asn7, βAla11, Phe13, Nle14]Bn(6–14) | #12 | 2.04 ± 0.06 | 1.99 ± 0.09 | 3.16 ± 0.13 | 1.82 ± 0.06 |

Ability of different compounds to stimulate increases in [3H]IP formation in hGRP-R-transfected Balb-3T3, HuTu-80, hNMB-R-transfected Balb-3T3 cells and NCI-H1299. The cells (5.0×104 cells/well) were loaded with myo-[2–3H]inositol as described under Materials and Methods, washed, and incubated with the indicated concentrations of compounds for 45 min at 37°C. Values are expressed as the peptide concentration causing a half-maximal increase (EC50) in the total [3H]IP release stimulated by 1 µM GRP or NMB. Results are the means ± S.E.M. from at least 3 experiments, and each point was determined in duplicate.

Abbreviations: GRP, gastrin-releasing peptide; Bn, Bombesin; remainder abbreviations see Table 1.

Similar to described in other studies of interaction of the natural ligands with their preferred Bn receptor subtype, the natural ligand for the GRP receptor, GRP, had a high affinity for human GRP receptors on both cell lines (i.e. 0.17–0.19 nM), >650-fold higher affinity than for hNMB receptors and >15,000-fold higher than hBRS-3 [2,4,29,85] (Table 2, Fig. 1–2). Similarly, as reported in human and nonhuman tissues containing NMB receptors, NMB had a high affinity for both hNMBR containing cell lines (i.e. 0.052–0.054 nM), which was >650-fold higher than for hGRP receptors and >20,000 higher than for hBRS-3 (Table 2, Fig. 1–Fig. 2)[3,4,29,57,90,94]. The two novel synthetic ligands, [D-Tyr6, βAla11, Phe13, Nle14]Bn(6–14)[#9, Table 2] and [D-Phe6, βAla11, Phe13, Nle14] Bn(6–14) [#10, Table 2] had very high affinity (i.e. 0.048–0.8 nM) for all human Bn receptor subtypes, including hBRS-3 (Table 2, Fig. 3–4) which is consistent with previous studies [17,29,44,46,67,75].

Table 2.

Affinities of agonists for hGRPR and hNMBR in Balb-3T3, HuTu-80, NCI-H1299 cells and hBRS-3 Balb-3T3 cells.

| IC50 (nM) |

IC50 (nM) |

IC50 (nM) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bombesin Analogue | Peptide Name/# |

HuTu-80 | hGRPR Balb-3T3 |

hNMBR NCI-H1299 |

hNMBR Balb-3T3 |

hBRS-3 Balb-3T3 |

| Natural Peptides | ||||||

| Bombesin-related | ||||||

| Bombesin | Bn | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 3.7 ± 0.2 | 1.77 ± 0.04 | > 3,000 |

| Gastrin-releasing peptide (14–27) | GRP | 0.19 ± 0.01 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 123 ± 16 | 148 ± 8 | > 3,000 |

| Alytesin | Aly | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 0.56 ± 0.03 | 1.86 ± 0.07 | 1.17 ± 0.04 | > 3,000 |

| Neuromedin C | NMC | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 75.9 ± 3.9 | 37.2 ± 0.9 | > 3,000 |

| Neuromedin B-related | ||||||

| Neuromedin B | NMB | 35.08 ± 0.88 | 50.1 ± 2.5 | 0.054 ± 0.002 | 0.052 ± 0.003 | > 3,000 |

| NMB30 | NMB30 | 15.31 ± 0.26 | 18.2 ± 0.4 | 0.304 ± 0.018 | 0.198 ± 0.010 | > 3,000 |

| Rohdei-litorin | Roh-Lit | 190 ± 10 | 110 ± 6 | 0.26 ± 0.12 | 0.178 ± 0.009 | > 3,000 |

| Litorin | Lit | 2.69 ± 0.13 | 0.54 ± 0.03 | 0.56 ± 0.03 | 0.158 ± 0.004 | > 3,000 |

| Ranatensin | Ran | 2.24 ± 0.11 | 3.16 ± 0.16 | 4.47 ± 0.16 | 1.48 ± 0.01 | > 3,000 |

| P-GL | PG-L | 0.68 ± 0.03 | 0.83 ± 0.04 | 0.89 ± 0.05 | 0.66 ± 0.01 | > 3,000 |

| Phyllolitorin-related | ||||||

| Phyllolitorin | PLL | > 3,000 | > 3,000 | 2.34 ± 0.07 | 2.30 ± 0.1 | > 3,000 |

| [Leu8]phyllolitorin | LeuPLL | 524 ± 26 | 372 ± 19 | 295 ± 17 | 309 ± 13 | > 3,000 |

| Synthetic | ||||||

| [Leu14]Bn | #1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.32 ± 0.04 | 295 ± 11 | 269 ± 3 | > 3,000 |

| [Tyr4,Nleu14]Bn | #2 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.30 ± 0.01 | 41.7 ± 1.8 | 21.3 ± 0.9 | > 3,000 |

| [D-Trp8,Leu14]Bn | #3 | 417 ± 16 | 710 ± 30 | > 3,000 | > 3,000 | > 3,000 |

| [D-Ala11]Bn | #4 | 0.54 ± 0.04 | 0.71 ± 0.04 | 190 ± 14 | 42.7 ± 0.9 | > 3,000 |

| [N-3-Pentanyl,D-Phe6,D-Ala11,Leu14]Bn(6–14) | #5 | 16.6 ± 0.7 | 11.7 ± 0.5 | > 3,000 | 1070 ± 27 | > 3,000 |

| [D-Phe6,D-Ala11,Leu14]Bn(6–14) | #6 | 10.0 ± 0.8 | 12.6 ± 0.5 | 1,000 ± 20 | 794 ± 33 | > 3,000 |

| [D-Phe6]Bn(6–14) | #7 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 2.14 ± 0.06 | 1.26 ± 0.04 | > 3,000 |

| [D-Cys6,D-Ala11,Cys14]Bn(6–14) | #8 | 437 ± 22 | 575 ± 29 | > 3,000 | > 3,000 | > 3,000 |

| [D-Tyr6,βAla11,Phe13,Nle14]Bn(6–14) | #9 | 0.027 ± 0.002 | 0.074 ± 0.002 | 0.76 ± 0.03 | 0.316 ± 0.005 | 0.45 ± 0.04 |

| [D-Phe6, βAla11,Phe13,Nle14]Bn(6–14) | #10 | 0.048 ± 0.005 | 0.085 ± 0.001 | 0.32 ± 0.02 | 0.21 ± 0.01 | 1.30 ± 0.10 |

| [D-Tyr6,Asn7,βAla11,Phe13, Nle14]Bn(6–14) | #11 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.35 ± 0.04 | 31.6 ± 1.1 | 9.55 ± 0.31 | 25.7 ± 0.33 |

| [D-Ser-Ser-D-Ser-D-Tyr6,Asn7, βAla11, Phe13, Nle14]Bn(6–14) | #12 | 6.8 ± 0.2 | 9.3 ± 0.2 | 11.2 ± 0.7 | 5.37 ± 0.22 | 433 ± 33 |

HuTu-80 (1.5×106 cells/ml) and hGRPR-Balb-3T3 transfected (0.5×106 cells/ml) were incubated with 50pM 125I-[Tyr4]Bn, hNMBR-NCI-H1299 transfected (1×106 cells/ml), hNMBR-Balb-3T3 transfected (0.05×106 cells/ml) and (1.0×106 cells/ml) with 125I-[D-Tyr0]NMB and hBRS-3-Balb-3T3 transfected (0.8×106 cells/ml) with 50 pM 125I-[D-Tyr6,β-Ala11,Phe13,Nle14]Bn-(6–14) for 1 h at 22°C. Increasing concentrations of unlabeled peptide were added, and dose-response curves were analyzed using KaleidaGraph. Results are expressed as the peptide concentration causing half-maximal inhibition (IC50) of saturable binding. Values are mean ± S.E. from at least 4 experiments. >3,000 means the affinity was greater than 3,000 nM.

Abbreviations: GRP, gastrin-releasing peptide; Bn, Bombesin; remainder abbreviations see Table 1.

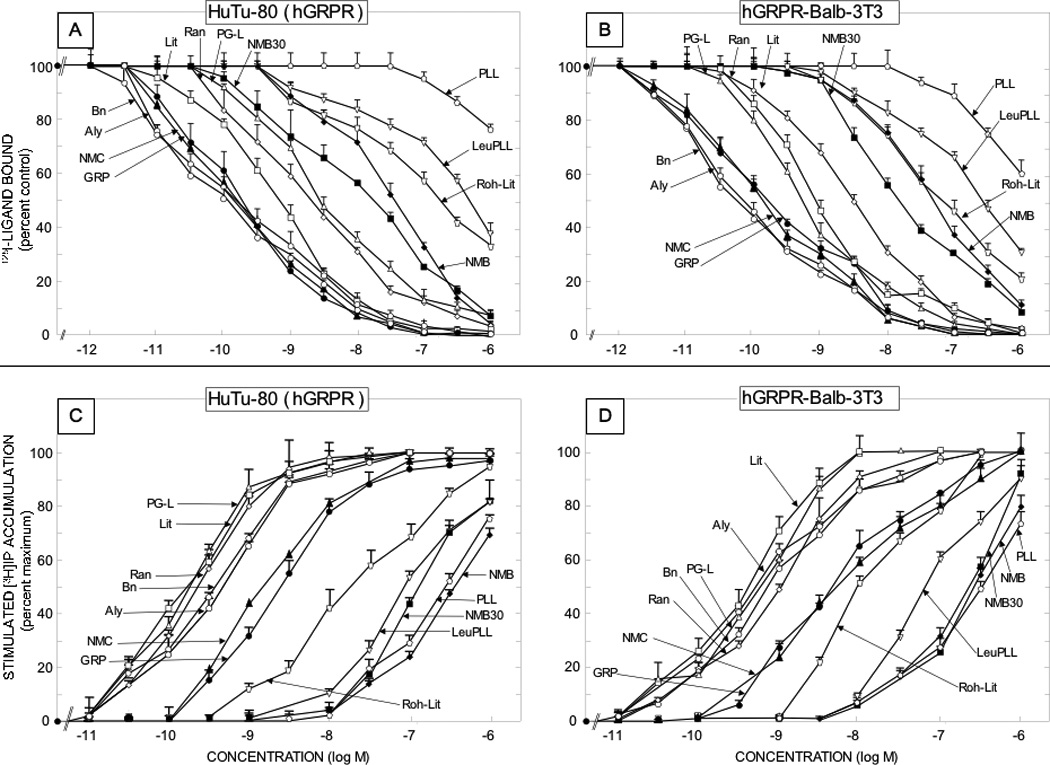

Figure 1.

Comparison of affinities for binding and potencies for activation of various natural Bn related peptide agonists for native human GRP receptors on the HuTu-80 cell line [left panels] and Balb 3T3 cells transfected with hGRPR [right panels]. The upper panels [Panels A and B] show the affinities from binding studies using 50 pM 125I-[Tyr4] Bn as the ligand. The lower panels [panels C and D] show their potencies for activating phospholipase C and stimulating changes in total cellular [3H]inositol phosphates ([3H]IP). The experimental conditions were as outlined in the legend to Table 2 and as described under Materials and Methods. Values are mean ± S.E.M. from at least four experiments. Full names of peptide abbreviations are shown in Table 1.

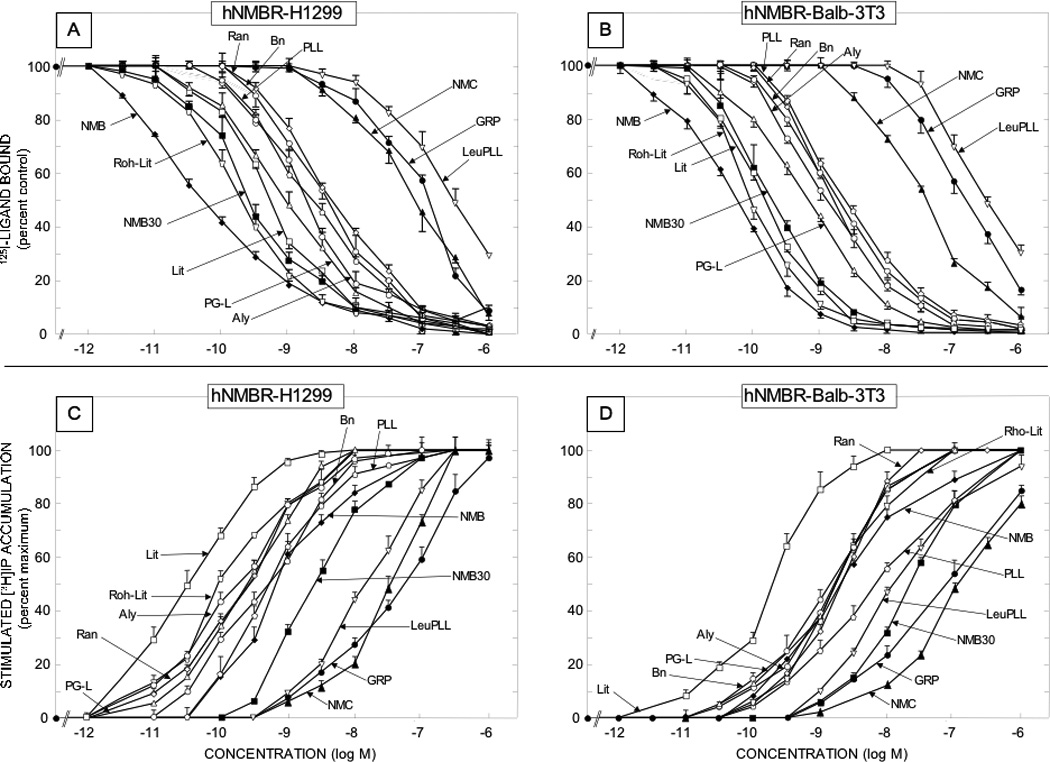

Figure 2.

Comparison of affinities for binding and potencies for activation of various natural Bn related peptide agonists for human NMB receptors overexpressed in low density on NCI-H1299 lung cancer cells [left panels] or in Balb 3T3 cells transfected with hNMBR [right panels] The upper panels [Panels A and B] show the affinities from binding studies using 50 pM 125I-[D-Tyr0]NMB as the ligand. The lower panels [panels C and D] show their potencies for activating phospholipase C and stimulating changes in total cellular [3H]inositol phosphates ([3H]IP). The experimental conditions were as outlined in the legend to Table 2 and as described under Materials and Methods. Values are mean ± S.E.M. from at least four experiments. Full names of peptide abbreviations are shown in Table 1.

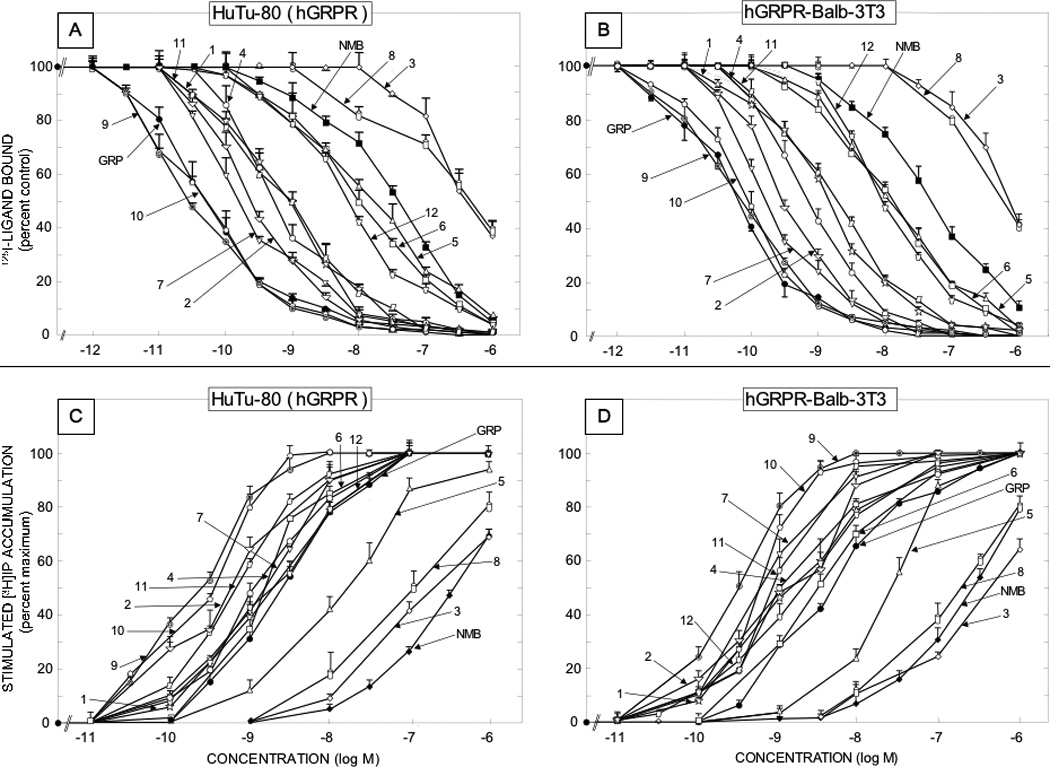

Figure 3.

Comparison of affinities for binding and potencies for activation of various synthetic Bn related peptide agonists for native human GRP receptors on the HuTu-80 cell line [left panels] and Balb 3T3 cells transfected with hGRPR [right panels]. The upper panels [Panels A and B] show the affinities from binding studies using 50 pM 125I-[Tyr4]Bn as the ligand. The lower panels [panels C and D] show their potencies for activating phospholipase C and stimulating changes in total cellular [3H]inositol phosphates ([3H]IP). The experimental conditions were as outlined in the legend to Table 2 and as described under Materials and Methods. Values are mean ± S.E.M. from at least four experiments. Numbers refer to the peptide number in Table 1.

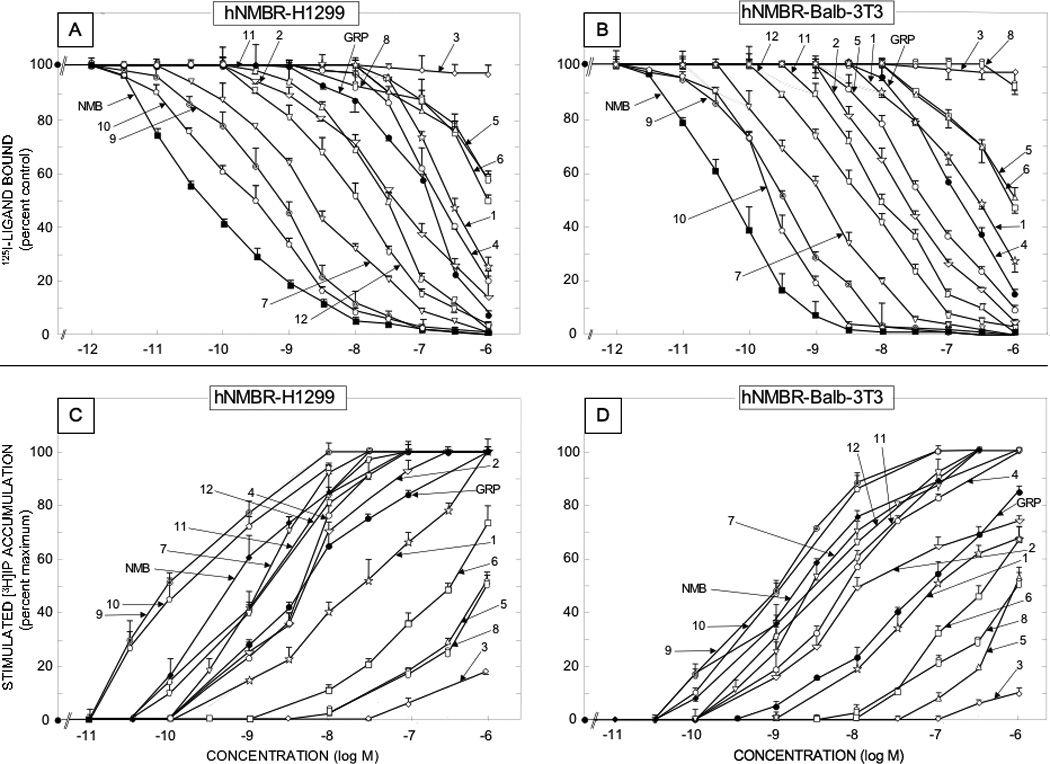

Figure 4.

Comparison of affinities for binding and potencies for activation of various synthetic Bn related peptide agonists for human NMB receptors overexpressed in low density on NCI-H1299 lung cancer cells [left panels] or in Balb 3T3 cells transfected with hNMBR [right panels] The upper panels [Panels A and B] show the affinities from binding studies using 50 pM 125I-[D-Tyr0]NMB as the ligand. The lower panels [panels C and D] show their potencies for activating phospholipase C and stimulating changes in total cellular [3H]inositol phosphates ([3H]IP). The experimental conditions were as outlined in the legend to Table 2 and as described under Materials and Methods. Values are mean ± S.E.M. from at least four experiments. Numbers refer to the peptide number in Table 1.

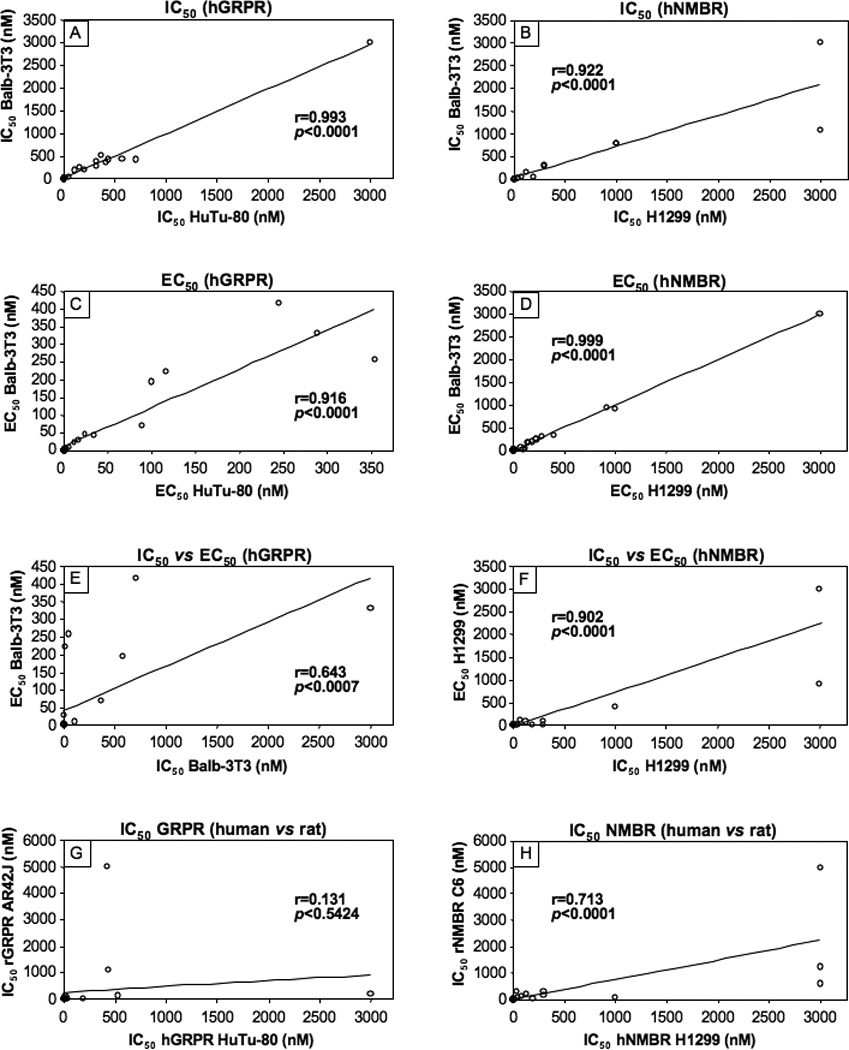

The 12 naturally occurring peptides could be divided into three chemical groups (Tables 1) including four GRP-related peptides, six NMB-related and two phyllolitorin-related peptides (Table 1). There was a close correlation of the affinities of the natural and synthetic Bn-related analogues for hGRP receptors on Balb 3T3 cells and HuTu-80-cells (Table 2; Fig. 5, Panel A) (r=0.99, p<0.0001). In general, for the hGRP receptor in hGRPR-transfected Balb 3T3 cells and native hGRP receptors in HuTu-80 cells the relative affinities were: very high affinity (IC50 <1 nM) for all four GRP-related peptides (Bn, GRP, alytesin, NMC) and two NMB-related peptides (litorin, PG-L); high affinity (IC50 2–3 nM) for one NMB-related peptide (ranatensin); intermediate affinity (IC50 15–50 nM) for two NMB-related peptide (NMB, NMB-30); low affinity (IC50 =110–500 nM) for two NMB-, PLL- related peptides (rohdei-litorin, Leu PLL) and very low affinity (IC50 > 1 uM) for one PLL-related peptide (PLL)(Table 2, Fig. 1–2). Similar to the two hGRP-receptor containing cells, the natural and synthetic Bn-related peptides showed a close correlation between their affinities for the two hNMB-containing receptor cell lines (Table 2; Fig. 5, Panel B)(r=0.92, p<0.0001). However, in contrast to the GRP receptor containing cell lines, in terms of their relative affinities for hNMBR expressing BALB 3T3 cells and NCI-H1299 cells, the 12 natural occurring peptides had the following relative affinities; very high (IC50 < 1 nM) for five NMB-related peptides (NMB, NMB-30, PG-L, rohdei-litorin, litorin); high affinity (IC50 1–3 nM) for four Bn-, PLL- and NMB-related peptides (Bn, alytesin, ranatensin, PLL); intermediate affinity (37–75 nM) for one Bn-related peptide (NMC) and low affinity (IC50 = 300 nM) for one PLL-related peptide (Leu PLL) and for GRP (123–148 nM)(Table 2, Fig. 1). NMB had an extremely high affinity for the hNMB receptor on both cell lines (IC50-0.052–0.054 nM), which was >3-fold higher that the other four peptides (NMB-30, PG-L, rohdeilitorin, litorin) with very high affinities (i.e.>1 nM) for the hNMBR (Table 2, Fig. 2). All of the 12 naturally occurring Bn peptides had very low affinities (IC50 >1000 nM) for the hBRS-3 receptor (Table 2).

Figure 5.

Correlations of the affinities and potencies of the various natural occurring Bn-related peptides and synthetic peptides for the different human Bn receptor cells and for both rat GRP receptors and rat NMB receptors on AR42J cells or rat C6 glioblastoma cells, respectively. Each point represents data from a single Bn analogue shown in Table 1–4. In all graphs there are 27 points, although in most graphs <27 points are seen because the majority are clustered near the origin and superimposed on each other. Correlation coefficients were calculated using a least-squares analysis from the data shown in Fig. 1–4, and Tables 2–4 as described in Materials and Methods.

3.2. Human Bn receptor affinities-natural occurring peptides-relative affinities for different hBn receptors

In terms of their relative affinities to the natural ligand for the human GRP receptor, GRP [29,49], these results demonstrate that Bn, GRP, alytesin and NMC have approximately equal affinity, which is 5-fold higher than PG-L, 15-fold higher than litorin or ranatensin, 211–700- fold higher than NMB and >3000 fold greater than PLL, Leu PLL (Table 2, Fig. 1). For the human NMB receptor, the natural ligand, NMB [29,51] has a 3–10 fold higher affinity than litorin, rohdei-litorin; 15–70 fold higher than PG-L, Bn, alytesin; 40–80 fold greater than ranatensin or PLL and >700-fold higher than either NMC or Leu PLL (Table 2, Fig. 2).

3.3. Human Bn receptor affinities-synthetic Bn-related peptides- Affinities for same hBn receptor

The 12 synthetic Bn agonists consisted of a range of different Bn analogues that either they or closely related Bn analogues have been used in various studies [29,47,59,69]. These included four Bn analogues containing a Leu14 substitution (Table 1; peptides #1,3,5,6); four Bn analogues containing a Nle14 substitution (Table 1, peptides #2,9, 10,11); four Bn analogues containing a D-Ala11 substitution (Table 1, peptides #4–6,8); one cyclic Bn agonist (Table 1, peptide #8)[8]; eight truncated Bn (6–14) analogues (Table 1, peptides # 5–12), and four β-Alanine11 substituted Bn analogues (Table 1, peptides # 9–12)[46,55,62,67,77,96]. The affinities of the 12 synthetic Bn analogues (Table 2), which were all analogues of either Bn or Bn (6–14), the minimal COOH fragment required for full affinity and biological activity [6,29,38,48], varied over a 10,000 fold range in their affinities for hGRPR containing cells (Table 2, Fig. 3). Four substituted Bn analogues retained very high affinities (IC50 −0.027–0.4 nM) approximately equal to Bn’s for hGRP receptors on either cell line (Table 2, peptides # 2,7,9,10); three peptides retained high affinity (IC50 −0.7–1.3 nM), but it was decreased 3- to 15-fold compared to Bn (Table 2, peptides # 1, 4, 11); three peptides showed an intermediate affinity (IC50 −7–16.6 nM) with a decrease from 40- to 160-fold compared to Bn (Table 2, peptides # 5,6,12); and one had a low affinity (IC50 −417–750 nM) with a >2500-fold decrease compared with Bn (Table 2, peptides # 3)(Table 2, Fig. 3). The 12 synthetic analogues also varied markedly (range, 10,000-fold) in their affinities for the hNMB receptor bearing cells (Table 2, Fig. 4). None of the synthetic analogues retained the very high affinity of NMB (IC50 −0.052–0.54 nM) (Table 2, Fig. 4). Three Bn substituted analogues (Table 2, peptides # 7,9,10) retained high affinity (IC50 −0.21–2.1 nM) for the hNMB receptor containing cells, however their affinities were reduced 4- to 40- fold compared to NMB (Table 2, Fig. 4). Three synthetic peptides (Table 2, peptides # 2,11,12) showed an intermediate affinity (IC50 −5.4–42 nM) for the NMB receptor containing cells which represented a 100- to 800-fold decrease compared to NMB; two Bn analogues (Table 2, peptides #1, 4) showed low affinities (IC50 45–295 nM) which were 800- to 500-fold lower than NMB’s and four peptides showed very low affinities (IC50 794- to >3000 nM) which were >10,000- fold lower than NMB’s (Table 2, Fig. 4).

3.4. Human Bn receptor affinities-synthetic Bn-related peptides-relative affinities for different hBn receptors

In terms of their selectivity for hGRP or hNMB receptors on the different cells, the twelve natural Bn-related peptides (i.e. varied 1.2–1200-fold), as well as the twelve synthetic Bn-related peptides (i.e. varied 1–350-fold), showed a wide variation (Table 2, Fig. 1–4). The naturally occurring peptides could be divided into two general groups: four [litorin, ranatensin, PG-L, LeuPLL) that were non-selective for human GRP or NMB receptor containing cells (affinities varied <5-fold) and the remaining eight peptides, which showed some selectivity (>5 fold preferring) (Table 2, Fig. 1,2). For the eight selective natural peptides, four were selective for the hGRP receptor containing cells (GRP, NMC, Bn, Alytesin), with two having minimal selectivity (5–20-fold)[Bn, Alytesin] and two having high selectivity (>200-fold)[GRP, NMC](Table 2, Fig. 1,2). In contrast, four peptides (NMB, NMB-30, rohdei-litorin, PLL) were selective for hNMB receptor cells, with one (NMB-30) having moderate selectivity (50–90-fold) and the other three (NMB, rohdei-litorin, PLL) having high selectivity for NMB receptor (Table 2, Fig. 1,2). For the twelve synthetic Bn analogues, only one peptide, [peptide #12,Table 2, D-Ser-Ser-D-Ser-D-Tyr6,Asn7, βAla11]Bn(6–14)] was nonselective for hGRP or hNMB receptor cells, whereas the remaining eleven synthetic Bn analogues showed some selectivity for the hGRP receptor (Table 2, Fig. 3). Five of the eleven Bn synthetic peptides [Table 2,peptides #3,7–11] showed minimal selectivity (5–20-fold) for the hGRP receptor; three peptides [Table 2, peptides #2,5,6] had moderate selectivity (20–200) and two peptides [Table 2, peptides #1,4], high selectivity (>200-fold) for the hGRP receptor (Table 2, Fig. 3).

3.5. Human Bn receptor potencies of activation-natural and synthetic Bn-related peptides

To determine whether the putative Bn agonist’s can activate hGRP and hNMB receptors and their potencies and efficacies of activation, the ability of each to stimulate phospholipase C resulting in the generation of inositol phosphates ([3H]IP) was determined (Fig. 1–4). Activation of phospholipase C was assessed because for both the native and transfected hGRP receptor [2,3,14,15,29,98] as well as with hNMB receptors [3,4,29,91], stimulation of phospholipase C is one of the principal signaling cascades seen with receptor activation.

Each of the twelve putative natural Bn-related peptides as well as the twelve synthetic Bn peptides studied functioned as an agonist, and if sufficiently high concentrations could be used to assess maximal efficacy (i.e. up to 3 µM), all peptides were fully efficacious with either GRP at the hGRP receptor or NMB at the hNMB receptor (Fig. 1–4). The natural and synthetic Bn-related peptides demonstrated a close correlation between their potencies at activating the hGRP receptor in the two hGRP receptor containing cell lines (r=0.92, p<0.0001)(Table 3; Fig. 5, Panel C). A similar close correlation was found for their potencies in activating the hNMB receptor in the two different hNMB receptor cells lines (r=0.99, p<0.0001) (Table 3; Fig. 5, Panel D). In general, there was a close correlation between the potencies of natural and synthetic Bn-related analogues to activate either hNMB or hGRP receptors on the different cell lines and their affinities from binding studies (Tables 2,3; Fig. 5, Panels E, F). Specifically, for hNMB receptors on NCI-H1299 cells the different Bn-related peptide’s potencies for activation showed a correlation coefficient of r=0.90 (p<0.0001)(Fig. 5, Panel F) with their binding affinities; with hNMB Balb 3T3 cells the correlation between potencies and affinities was r=0.87, (p<0.0001); and for both hGRP receptor containing Balb 3T3 cells and HuTu-80 cells, the correlation coefficients were r=0.64, and 0.6, respectively (p<0.0007) (compare Table 2,3 and Figures 1–4, Fig. 5, Panel E).

3.6. Comparison of affinities of the various natural occurring and synthetic Bn peptides for human and rat GRP and NMB receptors

In contrast to the close correlation between the affinities of the different peptides for hGRP receptors on the two different hGRPR cell lines (r=0.99, p<0.0001, Fig. 5), there was no significant correlation between their affinities for native rat GRP receptors on the rat pancreatic acinar cancer cell line, AR42J and native hGRP receptors on the human HuTu cell line (r=0.131, p=0.54, Table 4; Fig. 5, Panel G), or hGRP receptors in Balb 3T3 cells (r=0.233, p=0.27) (Table 2 and 4). In contrast, there was a significant correlation between the affinities of the various peptides for NMB receptors on the rat glioblastoma cell line, C6 and hNMB receptors expressed in low levels in NCI-H1299 cells (r=0.71, p<0.0001) (Table 4; Fig. 5, Panel H) or hNMB receptors expressed in Balb 3T3 cells (r=0.76, p<0.0001) (Table 2 and 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of affinities of various natural and synthetic agonists for GRP-receptors and NMB-receptors in human and rat.

| IC50 (nM) |

IC50 (nM) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bombesin Analogue | Peptide Name/# |

HuTu-80 (hGRPR) |

AR42J (rGRPR) |

NCI-H1299 (hNMBR) |

C6 (rNMBR) |

| Natural Peptides | |||||

| Bombesin-related | |||||

| Bombesin | Bn | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 0.691 ± 0.08 | 3.7 ± 0.2 | 21 ± 7 |

| Gastrin-releasing peptide (14–27) | GRP | 0.19 ± 0.01 | 0.407 ± 0.08 | 123 ± 16 | 230 ± 16 |

| Alytesin | Aly | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 0.309 ± 0.008 | 1.86 ± 0.07 | 3.16 ± 0.17 |

| Neuromedin C | NMC | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.490 ± 0.027 | 75.9 ± 3.9 | 117 ± 8 |

| Neuromedin B-related | |||||

| Neuromedin B | NMB | 35.08 ± 0.88 | 35.7 ± 1.1 | 0.054 ± 0.002 | 0.398 ± 0.02 |

| NMB30 | NMB30 | 15.31 ± 0.26 | 21.18 ± 0.15 | 0.304 ± 0.018 | 0.448 ± 0.009 |

| Rohdei-litorin | Roh-Lit | 190 ± 10 | 23.2 ± 0.75 | 0.26 ± 0.12 | 1.02 ± 0.07 |

| Litorin | Lit | 2.69 ± 0.13 | 1.66 ± 0.083 | 0.56 ± 0.03 | 0.891 ± 0.05 |

| Ranatensin | Ran | 2.24 ± 0.11 | 1.08 ± 0.032 | 4.47 ± 0.16 | 5.63 ± 0.24 |

| P-GL | PG-L | 0.68 ± 0.03 | 0.490 ± 0.027 | 0.89 ± 0.05 | 3.09 ± 0.10 |

| Phyllolitorin-related | |||||

| Phyllolitorin | PLL | > 3,000 | 190 ± 14 | 2.34 ± 0.07 | 20.4 ±1.33 |

| [Leu8]phyllolitorin | LeuPLL | 524 ± 26 | 120 ± 8 | 295 ± 17 | 145 ± 10 |

| Synthetic | |||||

| [Leu14]Bn | #1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 24.8 ± 0.9 | 295 ± 11 | 324 ± 20 |

| [Tyr4,Nleu14]Bn | #2 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 1.36 ± 0.10 | 41.7 ± 1.8 | 74.1 ± 5.9 |

| [D-Trp8,Leu14]Bn | #3 | 417 ± 16 | > 3,000 | > 3,000 | > 3,000 |

| [D-Ala11]Bn | #4 | 0.54 ± 0.04 | 3.55 ± 0.15 | 190 ± 14 | 43.7 ± 1.6 |

| [N-3-Pentanyl,D-Phe6,D-Ala11,Leu14]Bn(6–14) | #5 | 16.6 ± 0.7 | 81.3 ± 3.4 | > 3,000 | 1230 ± 59 |

| [D-Phe6,D-Ala11,Leu14]Bn(6–14) | #6 | 10.0 ± 0.8 | 33.1 ± 1.7 | 1,000 ± 20 | 55 ± 4 |

| [D-Phe6]Bn(6–14) | #7 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 0.98 ± 0.04 | 2.14 ± 0.06 | 5.9 ± 0.3 |

| [D-Cys6,D-Ala11,Cys14]Bn(6–14) | #8 | 437 ± 22 | 1096 ± 81 | > 3,000 | 589 ± 13 |

| [D-Tyr6,βAla11,Phe13,Nle14]Bn(6–14) | #9 | 0.027 ± 0.002 | 0.020 ± 0.001 | 0.76 ± 0.03 | 0.977 ± 0.059 |

| [D-Phe6, βAla11,Phe13,Nle14]Bn(6–14) | #10 | 0.048 ± 0.005 | 0.033 ± 0.002 | 0.32 ± 0.02 | 1.29 ± 0.053 |

| [D-Tyr6,Asn7,βAla11,Phe13, Nle14]Bn(6–14) | #11 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.20 ± 0.03 | 31.6 ± 1.1 | 324 ± 29 |

| [D-Ser-Ser-D-Ser-D-Tyr6,Asn7, βAla11, Phe13, Nle14]Bn(6–14) | #12 | 6.8 ± 0.2 | 4.19 ± 0.17 | 11.2 ± 0.7 | 31.6 ± 2.0 |

HuTu-80 (1.5×106 cells/ml) and AR42J (1.0×106 cells/ml) were incubated with 50pM 125I-[Tyr4]Bn, hNMBR-NCI-H1299 transfected (1×106 cells/ml) and C6 (1.0×106 cells/ml) with 125I-[D-Tyr0]NMB for 1 h at 22°C. Increasing concentrations of unlabeled peptide were added, and dose-response curves were analyzed using KaleidaGraph. Results are expressed as the peptide concentration causing a half-maximal decrease (IC50) in saturable binding. Values are mean ± S.E. from at least 4 experiments. >3,000 means the affinity was greater than 3,000 nM.

Abbreviations: GRP, gastrin-releasing peptide; Bn, Bombesin; remainder abbreviations see Table 1.

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to assess the abilities of various naturally occurring Bn-related and synthetic Bn agonist analogues, which are increasingly used in human studies [19,41,59,95], to interact with and activate human bombesin receptors [29,47,59,69]. This study was performed because most of the pharmacology of Bn receptors has been performed on nonhuman cells, particularly rat tissues [6,11,22,29,33,47,69,90,97] and the results generally extrapolated to human pharmacology. This has occurred because few human tumor cell lines possess only one subtype of human Bn receptor when they are present; expressed human Bn receptors on various cells can have different pharmacology/cell signaling than native receptors, and until recently there was minimal interest in human Bn receptor studies [7,29,33]. Recently this has changed with the widespread interest in taking advantage of Bn receptor overexpression in various human tumors for Bn receptor-mediated imaging and/or cytotoxicity, using primarily Bn receptor agonists [66,67,95]. However, the extrapolation of pharmacological/signaling results from nonhuman studies to human tissues may be problematic, because a number of studies have shown with Bn receptors, as well as a number of other peptide G protein-coupled receptors [VPAC, tachykinins, melanocortin, vasopressin, endothelin], important differences may exist in pharmacology/cell signaling between these receptors on humans and nonhuman tissues, as well as on cells from different animal species [3,13,23,27,35,40,68,79,88,92,93]. With a number of these receptors there are especially important differences between human and rodent species (rat, mouse), which are the most widely used laboratory animals and whose receptors are frequently characterized pharmacologically, such as with Bn receptors [23,27–29,35,40,68,79,88,92,93].

Work with various G-protein coupled receptors have shown that the pharmacological results including receptor affinity and/or ability to activate the receptor (potency, efficacy) can be effected by the receptor expression level as well as the cell in which the receptor is expressed in [16,50,65,84,87,89,99]. In our study, a number of precautions were taken to be certain that the results obtained are reflective of the natural human Bn receptor responses. First, the hGRPR, hNMBR and hBRS-3 were stably expressed in Balb 3T3 cells, a cell type in which the expressed Bn receptors have been shown to pharmacologically mirror the wild type receptors and also show cell signaling behavior that mirrors the wild type GRPR and NMBR [2–4]. Secondly, studies of hGRPR pharmacology/activation were performed using the duodenal cancer cell line, HuTu-80, which natively expresses hGRPR [18,98]. Third, because a human cell line expressing only native NMBR was not available, hNMBR was minimally over-expressed in NCI-H1299 cells, which natively have a very low density of hNMBR [7,46], to a receptor density in the same range as native hGRPR in human HuTu-80 cells (HuTu-80 GRP receptor density was 1.68 ± 0.08 fmoles/106 cells vs. a hNMBR receptor density on NCI-H1299 transfected cells of 2.11 ± 0.20 fmoles/106 cells). Fourth, for comparative studies to the Bn receptor’s pharmacology in rats, AR42J pancreatic acinar tumor cells were used which natively express the rat GRP receptor [42] and rat C6 glioblastoma cells, which contain native rat NMB receptor [91,94] and assays were performed under identical conditions to human studies.

The human GRP receptor is now receiving the most attention of the three human Bn receptor subtypes (hGRPR, hNMBR, hBRS-3), because it is the most frequently overexpressed in human neoplasms, has important roles in growth regulation of a number of tumors and is important in a number of pathophysiological processes of clinical interest [19,29,31,41,77,95]. In our study of the 24 peptides examined (12-natural, 12-synthetic), there was very close agreement for both binding affinities (r=0.993, p<0.0001) and potencies for activation (r=0.92, p<0. 0001) for the different peptides in the two different cell lines, supporting the approach used. Three of the Bn-structurally related peptides (Bn, alytesin, NMC) studied and two NMB-related peptides (litorin, PG-L) had very high affinity (<1 nM), which was similar to that of the native ligand, GRP, for the hGRP receptor, in addition to four synthetic Bn analogues (Table 2, peptides #2,7,9,10). The relative and absolute affinities/potencies of these 24 peptides in many cases vary significantly from what is reported in a number of nonhuman tissues [2,6,11,22,29,30,32,38,46,47,69,90,97]. Particularly important is the case of Bn and GRP, which we find, are equipotent at hGRP receptors, which is consistent with two other studies of human GRPR containing tissues [63,64], but differs from the case of the mouse and rat GRP receptor, where Bn is reported to have a 2–5 fold higher affinity in some studies, but not others [2,33,46,63,64,82,85,97]. The possible marked difference in the rat GRP receptor pharmacophore compared to that for the human GRPR for these different agonists which is suggested by comparison to the literature values, was confirmed in the present study by the direct comparison under identical experimental conditions of the affinities of these 24 peptides for native rGRPR and hGRPR on the rat pancreatic cell line, AR42J and human HuTu-80 tumor cells, respectively. Our results demonstrated that there was no correlation (r=0.131, p<0.54) between the affinities of these 24 peptides for GRP receptors on these two different cell lines, demonstrating that pharmacological results from studies on rat GRP receptors cannot be extrapolated to what might be expected with human GRP receptors. However, the hGRP receptor’s pharmacophore had a number of important features in common with that described in nonhuman Bn receptor studies. With both hGRP and nonhuman GRP receptors, in Bn’s COOH terminus, norluecine14, but not leucine14, can be substituted with full retention of affinity, for methionine14 (Met27 in GRP), which helps prevent oxidization and loss of biological activity; the trytophan in position 8 of Bn (Trp21 GRP) is essential for biologic activity, and the replacement of glycine11 in Bn by βalanine results in a high affinity GRP receptor agonist, which also functions also as a high affinity agonist at the NMB receptor [6,29,38,46,47,62,69,76]. These results have a number of practical consequences. First, they suggest that for studies requiring high affinity interaction with the human GRP receptor, one of the above high affinity/potency peptides or its analogues, should be used. For example, in a recent study [40] examining the ability of Bn receptor ligands to either image hGRPR overexpressing tumors or for GRP receptor-mediated tumoral cytotoxicity [77], it was found that the ability of xenografted, Bn-containing tumors to take up injected radiolabeled Bn-ligands, correlated with the ligand’s receptor affinities [40]. More than forty different Bn receptor ligands have been proposed in various studies for this purpose in the literature [77], many without detailed pharmacologic characterization, raising the possibility that their low uptakes in some cases are likely related to their lower affinities for the human GRP receptor because a low affinity ligand was selected. Second, in many studies, synthetic analogues of Bn (7–14) or [D-Ala11] Bn analogues are used as agonists for hGRP receptor studies such as for tumor imaging/cytotoxicity, based primarily on studies in nonhuman tissues [77]. In these nonhuman cell studies, it was reported the COOH terminus of GRP is the biologically active portion, with the COOH octapeptide retaining full potency, as well as a Bn analogue with a D-Ala11 replacement for Gly11 for greater stability [6,38,47,47,69]. Our results demonstrate that various Bn D-Phe6 substituted octapeptide analogues do have equal high affinity to GRP, equal potency and are fully biologically active, therefore COOH truncated octapeptide analogues of either BN/GRP can be used without loss of affinity/potency for human studies. However, we found, in contrast to nonhuman study results [6,38,47,47,69], the substitution of D-Ala11 in Bn([D-Ala24]GRP) analogues resulted in a 4–10-fold decrease in affinity/potency compared to native Bn/GRP for the hGRP receptor and therefore is not recommended for human GRP receptor agonist studies where high affinity receptor interaction may be needed.

The human NMB receptor has not received as much attention as the hGRP receptor, however it is also receiving increased interest, because it is overexpressed in a number of human neoplasms; has potent growth effects on some tumors and can be altered in various clinical conditions, especially related to thyroid function/dysfunction [19,29,31,41,53,61,95]. In our study of the 24 peptides examined (12-natural, 12-synthetic), there was very close agreement for both hNMBR binding affinities (r=0.92, p<0.0001) and potencies for activation (r=0.999, p<0. 0001) for the different peptides in the two different cell lines, showing the results were not cell specific. We found that only NMB and three other natural NMB related peptides (NMB30, litorin, Rohdei-litorin) had very high affinities (i.e. <1 nM) and high potencies for activating the human NMB receptor. Although there is limited data in the literature on the NMB receptor in other species, our human data are consistent with studies in rat tissues [4,37,46]. NMB is reported also to have a very high affinity (IC50-0.4 nM) for the rNMBR in rat esophageal muscle [90] or rNMBR transfected Balb cells [20] and in most, but not all studies to be equipotent to litorin and >50 fold more potent than Bn and >200 times more potent than GRP [4,37,46]. For the 12 synthetic Bn analogues only peptide #10 [Tables 1–3, D-Phe6, βAla11, Phe13, Nle14] Bn(6–14)] and its D-Tyr6 analogue (peptide #9, Tables 1–3) had very high affinity (<1 nM) for the hNMB receptor which is similar to data reported for the rat NMB receptor [46,55,62]. The comparison of our data to the literature suggested, that in contrast to the GRP receptors, there appeared to be a close correlation between human NMBR affinities for the 24 peptides studied and for what was reported with rat NMB receptor. To investigate this directly, the affinities of the 24 Bn analogues were compared between native rat NMB receptors on C6 glioblastoma cells and hNMB receptors expressed at physiological levels in NCI-H1299 cells. In contrast to the case with the GRP receptors, we found a highly significant correlation (r=0.71, p<0.0001) between the affinities of rat and human NMB receptors for the different Bn analogues, supporting the conclusion that the rat pharmacologic data for NMB receptors generally was predictive for hNMB receptor pharmacology. It is well reported, even with Bn receptors, that various antagonists can show marked species differences with a given Bn receptor subtype [9,92,93]. Our results demonstrate this can also occurs with Bn receptor agonists because we found that species correlations may differ markedly with two closely related receptors (60% amino acid homology for GRPR and NMBR), with a close correlation existed between rat and human for 27 agonists for the NMB receptor, but not for the GRP receptor. Previous studies show that a similar result occurs with the Bn receptor agonist, [D-Phe6, βAla11, Phe13, Nle14] Bn(6–14)(peptide #10, Table 1,2), which has a high affinity/potency for activation for all human Bn receptors (hGRPR, hNMBR, hBRS-3); for GRPR and NMBR in all species tested (rat, mouse, monkey, human), but not for rat and mouse BRS-3 [39,46,62,74,75]. A subsequent study showed that this difference between the rat and human BRS-3 receptor affinity for [D-Phe6, βAla11, Phe13, Nle14] Bn(6–14) was due to differences in amino acids in the third extracellular domains of the two receptors [39]. Similar data has been reported previous for agonist affinities for melanocortin receptors (MC) with rat and human MC receptors showing no difference, while there were marked differences for the rat and human MC4 receptor, as well as the MC1 and MC5 receptors [79]. Similarly with the three subtypes of vasopressin receptors (V1a, V1b, and V2) the degree of correlation between the rat and human receptor subtypes for vasopressin agonists differed markedly [23]. These results support the conclusion that with a family of receptor subtypes, one cannot assume a given subtype’s pharmacology will correlate between rat and human, even though, with a closely related subtype in the same family, there is a close correlation.

The BRS-3 receptor, which is classified in the Bn receptor family because of its high homology (47–51% amino acids) with GRP and NMB receptors, remains an orphan receptor because its native ligand is still unknown [12,19,29,41,95]. It nevertheless, is receiving increased attention because of increasing evidence it is involved in energy and glucose metabolism, regulation of obesity and in recent studies also has growth effects in normal and neoplastic tissues [19,21,26,29,41,60,83,95]. None of 12 natural Bn related peptides examined in this study had high affinity for human BRS-3, similar to reported in other studies with various natural occurring Bn analogues [46,74,75] and of the 12 synthetic Bn analogues, only [D-Phe6, βAla11, Phe13, Nle14] Bn (6–14)(peptide #10, Table 1,2) and its D-Tyr6 analogue (Peptide #9, tables 1,2) had high affinity for hBRS-3. These two analogues have the disadvantage, that they are the only known agonists with high affinity for all human Bn receptors and therefore lack any specificity for the hBRS-3. However, this has the potential advance in making them universal agonist ligands that interact with all human Bn receptors and because various tumors often overexpress multiple subtypes [31], these ligands could interact with each subtype and therefore potentially have greater sensitivity for imaging and/or receptor-mediated cytotoxicity.

In our study each of the 24 Bn related agonists demonstrated an efficacy of activation of phospholipase C in hGRP or hNMB receptor cells equal to GRP or NMB, respectively, if sufficient high agonist concentrations could be used, showing that none of these Bn analogues functioned as a partial agonist at any of the three human Bn receptor subtypes. This is in contrast to a number of other groups of synthetic Bn receptor ligands including various desMet14Bn amides, desMet14Bn alkylamides, desMet14Bn esters and various ϕ13−14 Bn pseudopeptides, that can function as antagonist at the GRP receptor in some species, but function as a partial agonist in others [92,93] or that function as antagonist at the hGRP receptor but function as partial agonists at hNMBR receptors [18,73]. Because agonists that function as full agonists are rapidly internalized by Bn receptor-containing cells [29,55,80] the potent agonists described in this study with full efficacy for activating the receptor, should be especially useful for studies that require internalizations of the ligand, such as receptor mediated cytotoxicity studies [77].

In conclusion, a group of 24 putative Bn receptor ligands (12-natural, 12, synthetic) that are widely used in various nonhuman studies, are systematically investigated for their abilities to interact with each of the three subtypes of human Bn receptors [hGRPR, hNMBR, hBRS-3] and for their abilities to activate human GRP and NMB receptors on two different cell lines and the results compared to those from rat GRP and NMB receptors. A number of Bn analogues that function as potent, fully efficacious and selective agonist ligands for the hGRP and hNMB receptors are identified. Furthermore, the pharmacophore of the human GRP receptor for the 24 Bn analogues is shown to have no correlation with that of the rat GRP receptor, whereas there is a close correlation between the pharmacophore of these peptides for rat and human NMB receptor. These results demonstrate that it is not possible to predict either the affinity or the potency of various Bn agonist analogues for human GRP receptors from studies in rat, and detailed studies on human tissues are required.

Acknowledgment

This work was partial supported by intramural funds of the NIDDK, NIH.

Abbreviations

- βAla

βalanine

- Bn

bombesin

- BRS-3

bombesin receptor subtype 3

- BSA

bovine serum albumin fraction V

- CNS

central nervous system

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s minimum essential medium

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- GI

gastrointestinal

- GRP

gastrin-releasing peptide

- GRPR

gastrin-releasing peptide receptor

- IP

inositol-phosphates

- NMB

neuromedin B

- NMBR

neuromedin B receptor

- NMC

Neuromedin C

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PG-L

Pseudophryne güntheri litorin-like peptide

- PLL

phyllolitorin

References

- 1.Barra D, Erspamer Falconieri G, Simmaco M, Bossa F, Melchiorri P, Erspamer V. Rohdeilitorin: a new peptide from the skin of Phyllomedusa rohdei. FEBS Lett. 1985;182:53–56. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(85)81152-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benya RV, Fathi Z, Pradhan T, Battey JF, Kusui T, Jensen RT. Gastrin-releasing peptide receptor-induced internalization, down-regulation, desensitization and growth: Possible role of cAMP. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;46(2):235–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benya RV, Kusui T, Pradhan TK, Battey JF, Jensen RT. Expression and characterization of cloned human bombesin receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 1995;47:10–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benya RV, Wada E, Battey JF, Fathi Z, Wang LH, Mantey SA, et al. Neuromedin B receptors retain functional expression when transfected into BALB 3T3 fibroblasts: analysis of binding, kinetics, stoichiometry, modulation by guanine nucleotide-binding proteins, and signal transduction and comparison with natively expressed receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 1992;42(6):1058–1068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breeman WA, Kwekkeboom DJ, de Blois E, de Jong M, Visser TJ, Krenning EP. Radiolabelled regulatory peptides for imaging and therapy. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2007;7:345–357. doi: 10.2174/187152007780618171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Broccardo M, Erspamer GF, Melchiorri P, Negri L, DeCastiglione R. Relative potency of bombesin-like peptides. Br J Pharmacol. 1976;55:221–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1975.tb07631.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corjay MH, Dobrzanski DJ, Way JM, Viallet J, Shapira H, Worland P, et al. Two distinct bombesin receptor subtypes are expressed and functional in human lung carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:18771–18779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coy DH, Jiang NY, Kim SH, Moreau JP, Lin JT, Frucht H, et al. Covalently cyclized agonist and antagonist analogues of bombesin and related peptides. J Biol Chem. 1991;266(25):16441–16447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coy DH, Taylor JE, Jiang NY, Kim SH, Wang LH, Huang SC, et al. Short-chain pseudopeptide bombesin receptor antagonists with enhanced binding affinities for pancreatic acinar and Swiss 3T3 cells display strong antimitotic activity. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:14691–14697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Erspamer V, Melchiorri P. Active polypeptides of the amphibian skin and their synethetic analogues. Pure Appl Chem. 1973;35:463–494. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Falconieri Erspamer G, Severini C, Erspamer V, Melchiorri P, Delle Fave G, Nakajima T. Parallel bioassay of 27 bombesin-like peptides on 9 smooth muscle preparations, structure-activity relationships and bombesin receptor subtypes. Regul Pept. 1988;21:1–11. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(88)90085-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fathi Z, Corjay MH, Shapira H, Wada E, Benya R, Jensen R, et al. BRS-3: novel bombesin receptor subtype selectively expressed in testis and lung carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(8):5979–5984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fleischmann A, Laderach U, Friess H, Buechler MW, Reubi JC. Bombesin receptors in distinct tissue compartments of human pancreatic diseases. Lab Invest. 2000;80:1807–1817. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frucht H, Gazdar AF, Park JA, Oie H, Jensen RT. Characterization of functional receptors for gastrointestinal hormones on human colon cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1992;52:1114–1122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garcia LJ, Pradhan TK, Weber HC, Moody TW, Jensen RT. The gastrin-releasing peptide receptor is differentially coupled to adenylate cyclase and phospholipase C in different tissues. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1356:343–354. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(97)00007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.George ST, Berrios M, Hadcock JR, Wang HY, Malbon CC. Receptor density and cAMP accumulation: analysis in CHO cells exhibiting stable expression of a cDNA that encodes the beta2-adrenergic receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1988;150:665–672. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(88)90443-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gonzalez N, Hocart SJ, Portal-Nunez S, Mantey SA, Nakagawa T, Zudaire E, et al. Molecular basis for agonist selectivity and activation of the orphan bombesin receptor subtype 3 receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;324:463–474. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.132332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gonzalez N, Mantey SA, Pradhan TK, Sancho V, Moody TW, Coy DH, et al. Characterization of putative GRP- and NMB-receptor antagonist's interaction with human receptors. Peptides. 2009;30:1473–1486. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gonzalez N, Moody TW, Igarashi H, Ito T, Jensen RT. Bombesin-related peptides and their receptors: recent advances in their role in physiology and disease states. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2008;15:58–64. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e3282f3709b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gonzalez N, Nakagawa T, Mantey SA, Sancho V, Uehara H, Katsuno T, et al. Molecular basis for the selectivity of the mammalian bombesin peptide, neuromedin B, for its receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;331:265–276. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.154245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guan XM, Metzger JM, Yang L, Raustad KA, Wang SP, Spann SK, et al. Antiobesity effect of MK-5046, a novel bombesin receptor subtype-3 agonist. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;336:356–364. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.174763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guard S, Watling KJ, Howson W. Structure-activity requirements of bombesin for gastrin-releasing peptide- and neuromedin B-preferring bombesin receptors in rat brain. Eur J Pharmacol. 1993;240:177–184. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90896-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guillon G, Pena A, Murat B, Derick S, Trueba M, Ventura MA, et al. Position 4 analogues of [deamino-Cys(1)] arginine vasopressin exhibit striking species differences for human and rat V(2)/V(1b) receptor selectivity. J Pept Sci. 2006;12:190–198. doi: 10.1002/psc.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heinz-Erian P, Coy DH, Tamura M, Jones SW, Gardner JD, Jensen RT. [D-Phe12]bombesin analogues: a new class of bombesin receptor antagonists. Am J Physiol. 1987;252:G439–G442. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1987.252.3.G439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hildebrand P, Lehmann FS, Ketterer S, Christ AD, Stingelin T, Beltinger J, et al. Regulation of gastric function by endogenous gastrin releasing peptide in humans: studies with a specific gastrin releasing peptide receptor antagonist. Gut. 2001;49:23–28. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hou X, Wei L, Harada A, Tatamoto K. Activation of bombesin receptor subtype-3 stimulates adhesion of lung cancer cells. Lung Cancer. 2006;54:143–148. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Igarashi H, Ito T, Hou W, Mantey SA, Pradhan TK, Ulrich CD, II, et al. Elucidation of vasoactive intestinal peptide pharmacophore for VPAC1 receptors in human, rat and guinea pig. JPET. 2002;301:37–50. doi: 10.1124/jpet.301.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Igarashi H, Ito T, Pradhan TK, Mantey SA, Hou W, Coy DH, et al. Elucidation of the vasoactive intestinal peptide pharmacophore for VPAC2 receptors in human and rat, and comparison to the phrmacophore for VPAC1 receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;302:445–460. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.038075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jensen RT, Battey JF, Spindel ER, Benya RV. International Union of Pharmacology. LVIII. Mammalian Bombesin Receptors: Nomenclature, distribution, pharmacology, signaling and functions in normal and disease states. Pharmacol Rev. 2008;60:1–42. doi: 10.1124/pr.107.07108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jensen RT, Coy DH, Saeed ZA, Heinz-Erian P, Mantey S, Gardner JD. Interaction of bombesin and related peptides with receptors on pancreatic acini. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1988;547:138–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1988.tb23882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jensen RT, Moody TW. Bombesin-related peptides and neurotensin: effects on cancer growth/proliferation and cellular signaling in cancer. In: Kastin AJ, editor. Handbook of Biologically active peptides. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2006. pp. 429–434. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katsuno T, Pradhan TK, Ryan RR, Mantey SA, Hou W, Donohue PJ, et al. Pharmacology and cell biology of the bombesin receptor subtype 4 (BB4-R) Biochemistry (Mosc) 1999;38:7307–7320. doi: 10.1021/bi990204w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ladenheim EE, Jensen RT, Mantey SA, McHugh PR, Moran TH. Receptor heterogeneity for bombesin-like peptides in the rat central nervous system. Brain Res. 1990;537:233–240. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90363-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ladenheim EE, Jensen RT, Mantey SA, McHugh PR, Moran TH. Distinct distributions of bombesin receptor subtypes in the rat central nervous system. Brain Res. 1992;593:168–178. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91305-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leffler A, Ahlstedt I, Engberg S, Svensson A, Billger M, Oberg L, et al. Characterization of species-related differences in the pharmacology of tachykinin NK receptors 1, 2 and 3. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;77:1522–1530. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lehmann FS, Beglinger C. Gastrin-releasing peptide. In: Kastin AJ, editor. Handbook of Biologically active peptides. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2006. pp. 1047–1055. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin JT, Coy DH, Mantey SA, Jensen RT. Peptide structural requirements for antagonism differ between the two mammalian bombesin receptor subtypes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;275:285–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin JT, Coy DH, Mantey SA, Jensen RT. Comparison of the peptide structural requirements for high affinity interaction with bombesin receptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;294:55–69. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00510-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu J, Lao ZJ, Zhang J, Schaeffer MT, Jiang MM, Guan XM, et al. Molecular basis of the pharmacological difference between rat and human bombesin receptor subtype-3 (BRS-3) Biochemistry (Mosc) 2002;41:8954–8960. doi: 10.1021/bi0202777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maina T, Nock BA, Zhang H, Nikolopoulou A, Waser B, Reubi JC, et al. Species differences of bombesin analog interactions with GRP-R define the choice of animal models in the development of GRP-R-targeting drugs. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:823–830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Majumdar ID, Weber HC. Biology of mammalian bombesin-like peptides and their receptors. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2011;18:68–74. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e328340ff93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mantey S, Frucht H, Coy DH, Jensen RT. Characterization of bombesin receptors using a novel, potent, radiolabeled antagonist that distinguishes bombesin receptor subtypes. Mol Pharmacol. 1993;45:762–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mantey SA, Coy DH, Entsuah LK, Jensen RT. Development of bombesin analogs with conformationally restricted amino acid substitutions with enhanced selectivity for the orphan receptor human bombesin receptor subtype 3. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;310:1161–1170. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.066761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mantey SA, Coy DH, Pradhan TK, Igarashi H, Rizo IM, Shen L, et al. Rational design of a peptide agonist that interacts selectively with the orphan receptor, bombesin receptor subtype 3. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:9219–9229. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008737200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mantey SA, Gonzalez N, Schumann M, Pradhan TK, Shen L, Coy DH, et al. Identification of bombesin receptor subtype-specific ligands: effect of N-methyl scanning, truncation, substitution, and evaluation of putative reported selective ligands. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;319:980–989. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.107011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mantey SA, Weber HC, Sainz E, Akeson M, Ryan RR, Pradhan TK, et al. Discovery of a high affinity radioligand for the human orphan receptor, bombesin receptor subtype 3, which demonstrates it has a unique pharmacology compared to other mammalian bombesin receptors. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(41):26062–26071. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.26062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]