Abstract

WNK [with no lysine (k)] kinase is a serine/threonine kinase subfamily. Mutations in two of the WNK kinases result in pseudohypoaldosteronism type II (PHA II) characterized by hypertension, hyperkalemia, and metabolic acidosis. Recent studies showed that both WNK1 and WNK4 inhibit ROMK activity. However, little is known about the effect of WNK kinases on Maxi K, a large-conductance Ca2+ and voltage-activated potassium (K) channel. Here, we report that WNK4 wild-type (WT) significantly inhibits Maxi K channel activity in HEK αBK stable cell lines compared with the control group. However, a WNK4 dead-kinase mutant, D321A, has no inhibitory effect on Maxi K activity. We further found that WNK4 inhibits total and cell surface protein expression of Maxi K equally compared with control groups. A dominant-negative dynamin mutant, K44A, did not alter the WNK4-mediated inhibitory effect on Maxi K surface expression. Treatment with bafilomycin A1 (a proton pump inhibitor) and leupeptin (a lysosomal inhibitor) reversed WNK4 WT-mediated inhibition of Maxi K total protein expression. These findings suggest that WNK4 WT inhibits Maxi K activity by reducing Maxi K protein at the membrane, but that the inhibition is not due to an increase in clathrin-mediated endocytosis of Maxi K, but likely due to enhancing its lysosomal degradation. Also, WNK4's inhibitory effect on Maxi K activity is dependent on its kinase activity.

Keywords: protein expression, lysosomal degradation

wnk [with no lysine (k)] kinase belongs to a subfamily of serine/threonine kinases (55). Mutations in two members of this family, WNK1 and WNK4, result in pseudohypoaldosteronism type II (PHA II). PHA II, also referred to as Gordon's syndrome, is an autosomal dominant disorder, characterized by hypertension, hyperkalemia, and metabolic acidosis (51). This clinical phenotype suggests that WNK kinases might regulate renal potassium (K) channels, such as renal outer medullary potassium channel (ROMK) or Maxi K channels (BK channels) that are responsible for K handling by the distal nephron. A number of studies indicate that WNK kinases constitute a novel signaling pathway that is involved in the regulation of different ion transporters and channels controlling sodium and K homeostasis (23). In kidney tissue, there are two types of apical K channels identified in the distal nephron by patch-clamp analysis (38). One type of K channel is a low-conductance secretory K (SK) channel that has high open probability at resting membrane potential and mediates K+ secretion under basal conditions. The properties of the SK channel are consistent with those of ROMK. The other type of K channel has a high single-channel conductance (>100 pS) and channel kinetics similar to Maxi K channels (34). Although it is generally accepted that ROMK is the K+ secretory channel in the mammalian distal nephron, recent in vitro and in vivo studies have provided evidence that Maxi K can also serves as a K+ secretory channel in renal tubules (37) and that it plays an important role in K+ secretion in ROMK knockout mice and mice on a high-K diet (3).

As suggested by the clinical phenotype, recent studies have found that WNK1, WNK3, and WNK4 modulate ROMK activity in Xenopus laevis oocytes (13, 22, 26). WNK4 inhibits ROMK channel activity and its surface expression (58), whereas a WNK4 disease mutant enhanced inhibition of ROMK activity (22). WNK1 was also shown to inhibit ROMK activity, whereas a kidney-specific form of WNK1 reverses the WNK1 inhibition of ROMK (25, 47). These results suggest that both WNK1 and WNK4 inhibit ROMK activity. However, little is known about the effect of WNK kinases on Maxi K channel activity, the other major K channel in the distal nephron (50).

Maxi K, also referred to as the BK channel or slo1, is a large-conductance Ca2+ and voltage-activated K channel (150–250 pS) (50), which is sensitive to changes in both voltage and intracellular Ca2+. Maxi K is encoded by the gene slo1 (8) and widely distributed in many different tissues (21). Maxi K channels are composed of two subunits, a pore-forming α-subunit and a modulatory β-subunit (45). The α-subunit of Maxi K channels is modulated by many protein kinases, including cAMP-dependent PKA (28, 44, 60), PKC (4, 28, 54, 60), cGMP-dependent PKG (4, 17), and cSrc (1). It is also regulated extensively by alternative splicing (24), phosphorylation and dephosphorylation (11), and associated regulatory proteins such as β-subunits (7). The β-subunits alter the apparent Ca2+ and voltage sensitivity of the α-subunit, modify channel kinetics, and alter the pharmacological properties of the channel (5). The downregulation of the β1-subunit is involved in the development of vascular dysfunction during genetically induced hypertension (2). Maxi K is shown to be expressed in various renal tubular segments including medullary and cortical thick ascending limbs (43), distal convoluted tubule (DCT) (6), connecting tubule (16), principal cells (PC), and intercalated cells (IC) of the cortical collecting duct (CCD) (38). Maxi K is also involved in K handling in the kidney since it is well established that high distal tubular flow stimulates net K+ secretion and urinary K+ excretion in the distal nephron and CCD (53). A recent study showed that endogenous PKA and PKC modulate Maxi K activity in CCD cells (28). In addition, MAPK has been reported to inhibit Maxi K channel activity in rat principal cells (27). WNK4 enhances the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and p38 in response to both hypertonicity and EGF (40). Whether WNK4 directly modulates Maxi K activity or indirectly phosphorylates other protein kinases, such as MAPK, and ultimately affects Maxi K activity, remains unclear. Therefore, we investigated the effect of WNK4 kinase on Maxi K activity in HEK 293 cells stably expressing the α-subunit of the Maxi K channel and Cos-7 cells transiently transfected with the Maxi K channel.

Our results show that WNK4 inhibits Maxi K channel activity and its surface expression and that the inhibition is not due to an increase in clathrin-mediated endocytosis of Maxi K, but likely due to an increase in lysosomal degradation of Maxi K. The inhibitory effect of WNK4 on Maxi K activity is kinase dependent.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids and constructs.

Human wild-type (WT) WNK4 was amplified by PCR using a human kidney cDNA library and an expressed sequence tag clone from Incyte (Wilmington, DE) as the template. The PCR product matched the human WNK4 sequence (GenBank accession no. AF390018). The N-terminal myc-tagged and heme agglutinin (HA)-tagged WNK4 WT construct were generated by subcloning the WNK4 cDNA into a pCMV-Taq 3B vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and pCMV vector (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA). A WNK4 dead-kinase mutant, D321A, was generated using a Quickchange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) as shown in Fig. 1. Myc-tagged WT rabbit Maxi K plasmid was a gift from Dr. William Guggino (Johns Hopkins University). All constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing. These constructs have been successfully expressed in an African green monkey kidney cell (Cos-7) as confirmed by both Western blot analysis and immunofluorescence microscopy.

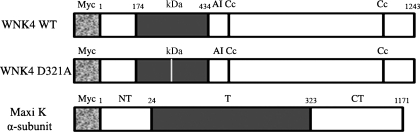

Fig. 1.

Human with no lysine (k; WNK) 4 wild-type (WT), its dead-kinase mutant D321A, and rabbit α-subunit of the Maxi K channel with their predicted domains. Shown is myc-tagged WNK4 WT with predicted domains KD, AI, and Cc, which indicate kinase domain, autoinhibitory domain, and coiled-coil domain, respectively. WNK4 D321A is a mutant lacking kinase activity. Myc-tagged rabbit Maxi K WT with extracellular amino terminus (NT), intracellular carboxyl terminus (CT), and transmembrane domain (T) is shown. The constructs for the molecules are not drawn to scale. The numbers above the constructs indicate the amino acid position.

Cell culture and transfection.

Cos-7 cells obtained from American Type Tissue Culture (ATCC) (Manassas, VA) were maintained in DMEM, supplemented with 10% FCS, l-glutamine (2 mM), penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). An HEK293 Maxi K α-subunit stable cell line was generated in our laboratory and maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS, l-glutamine (2 mM), penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), and geneticin (1 mg/ml). All other media and components were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Cells were transiently transfected using LipofectAMINE 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were used for Western blot analysis, immunoprecipitation, or immunostaining.

Single-channel recording.

All experiments in this study were carried out using the cell-attached configuration of the patch-clamp technique (19) in the HEK Maxi K α-subunit stable cell line cotransfected with or without pIRES-green fluorescent protein (GFP) WNK4, after which GFP fluorescence was used to identify the transfected cell for all relevant experiments. Electrodes were fabricated from Corning 7052 glass (Garner Glass, Fullerton, CA) in two steps on a Narishige PP-83 electrode puller (Narishige, Tokyo, Japan). The bath and pipette solutions used in the cell-attached mode contained (in mM) 140 NaCl, 1 CaCl2, 5 KCl, and 10 HEPES, pH adjusted to 7.4 with 2 N NaOH. Recordings were performed at room temperature. After formation of a high-resistance (5 GΩ) seal, the channel currents were filtered at 1 kHz, recorded with an Axopatch 1-D amplifier (Molecular Devices), and sampled at 5 kHz with or without ionomycin (1 μM) added to the bath solution. Ionomycin was used to increase intracellular Ca2+ to activate Maxi K channel activity. Channel activity (NPo) was calculated from pClampfit 9.2 data-analysis software (Molecular Devices). Channel number (N) was determined from the maximal number of transitions during 10–20 min of recording, and channel open probability (Po) was calculated as the ratio of NPo to N.

Western blot analysis and cell surface biotinylation.

Cos-7 cells were harvested and processed as described previously, and Western blotting was then performed (9). Briefly, cells transiently transfected with various DNA constructs as indicated were lysed in lysis buffer containing 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 120 mM NaCl, 5.0 mM EDTA, 1.0% Triton X-100, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 1.0 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and Complete protease inhibitor (1 tablet/50-ml solution, Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). The lysates were spun at 6,000 g for 5 min to pellet the insoluble material, and the proteins from the supernatant were quantified using a Pierce BCA Protein Assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). After being mixed in Laemmli buffer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and incubating at 37°C for 30 min, the protein sample was separated by SDS-PAGE and electrophoretically transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) for Western blotting. The probing with specific antibodies and subsequent detection with the ECL plus system (Amersham Biosciences) or Super signal (Pierce) were performed according to standard procedures as described previously. Cell surface biotinylation was performed as described previously with some modifications (9) In brief, 48 h after transfection, the cell surface proteins were labeled with membrane-impermeable sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin for 30 min at 4°C. After incubation with glycine (100 mM) and washing with PBS, the cells were lysed in lysis buffer. Lysates were incubated with immobilized NeutrAvidin beads (Pierce) overnight at 4°C, and bound proteins were eluted with 2× Laemmli sample buffer supplemented with 100 μM dithiothreitol at 42°C for 30 min. The eluted proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. The surface portion of Maxi K was detected by Western blotting using a myc antibody. Total lysate Maxi K, WNK4, or dynamin was detected by Western blotting using the respective antibodies.

Immunoprecipitation and coimmunoprecipitation.

Immunoprecipitation and coimmunoprecipitation were preformed as previously described (9). In brief, Cos-7 cells were transfected with plasmids as indicated. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were lysed. The cell lysates were incubated with primary antibodies for 2 h, then protein G/A Sepharose beads were added, and the lysates were further mixed and incubated overnight at 4°C. After washing with lysis buffer twice and PBS once, the beads were then eluted with Laemmli buffer (Bio-Rad). The eluted proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred onto PVDF membrane, and probed with appropriate antibodies. For coimmunoprecipitation experiments, blots were first probed with an antibody to the first binding partner. The PVDF membranes were then stripped and reprobed with an antibody to the second binding partner. Reciprocal immunoprecipitation was also performed with respective antibodies.

Immunostaining and confocal microscopy.

Immunostaining and confocal microscopy were performed as previously described (9). In brief, for immunostaining experiments the transfected HEK 293 cells were fixed and blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in PBS for 1 h, then incubated with primary antibodies for 30 min at 37°C. Cells were then washed with PBS three times followed by 30 min of incubation at 37°C with appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated to either FITC or isothiocyanate, Cy3 fluorescent dye (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA). After staining, the coverslips were washed thoroughly with PBS three times, mounted with antiquenching medium (Vector Lab, Burlingame, CA), and sealed. The slides were examined using a confocal laser-scanning microscope (model LSM510, Zeiss). The images were acquired using the manufacturer's software and prepared for publication with Adobe Photoshop. The colocalization analyses were performed using the manufacturer's software (Zen, Zeiss).

Statistical analysis.

The data are presented as means ± SE. Statistical significance was determined using either a Student's t-test when two groups were compared or by a one-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni's or Holm-Sidak's post hoc tests when multiple groups were compared. We assigned significance at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Effect of WNK4 WT and its dead kinase mutant D321A on Maxi K channel activity.

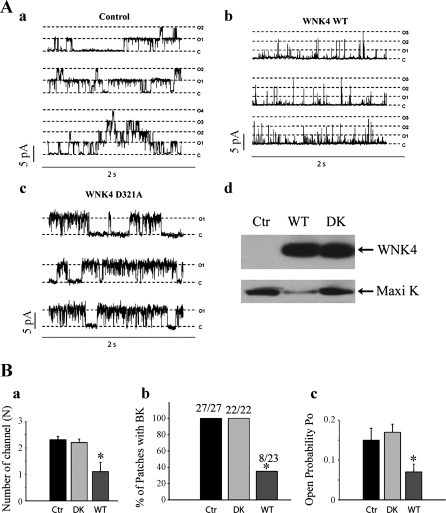

To determine whether WNK4 affects the regulation of Maxi K channels, we used HEK 293 cells that had been stably transfected with the α-subunit of mSlo (αMaxi K, accession no. NP_034740). In HEK 293 αMaxi K cells transfected with either WNK4 WT or its dead kinase mutant D321A (Fig. 2), we recorded single channels using the cell-attached patch-clamp technique to ensure that WNK4 signaling pathways were intact (57). Since Maxi K is a Ca2+- and voltage-activated K channel, we first treated cells with the calcium-permeable ionophore ionomycin (1 μM) to increase intracellular calcium and activate Maxi K channels. We found that WNK4 WT significantly inhibits Maxi K channel activity measured as NPo. As shown in Fig. 2, in HEK 293 αMaxi K cells in the absence of WNK4 expression (control group), the average number of channels per patch (N) was 2.3 ± 0.133, NPo was 0.11 ± 0.024, and Po was 0.15 ± 0.0295 at +40 mV (−Vpipette). With WNK4 expression, the average N was 1.09 ± 0.360, NPo was 0.060 4 ± 0.0156, and Po was 0.0678 ± 0.0159 at +40 mV. The density of functional channels (N) appeared to be reduced since the number of measurable current levels was greatly reduced compared with the control group (P < 0.01) (Fig. 2). On the other hand, the dead kinase mutant WNK4 D321A does not inhibit Maxi K activity (Fig. 2) (N was 2.2 ± 0.130, NPo was 0.166 ± 0.0156, and Po was 0.166 ± 0.0209 at +40 mV). As an indication of functional channel density, we also examined the frequency with which we observed Maxi K channels in patches. The number of patches with measurable Maxi K channel activity was significantly lower in cells transfected with WNK4 WT (8 active patches of 23 total patches) than either the control group (27/27; P < 0.0013) or the D321A group (22/22; P < 0.0037) (Fig. 2B). These two types of experiments suggested that WNK4 reduced the density of functional channels per unit area of membrane, but it also appeared from cursory analysis that WNK4 might also be reducing Maxi K channel Po (Fig. 2). However, in our experiments, we did notice a rightward shift with no change in the slope of the current-voltage (I-V) relationships for cells that had been transfected with WNK4 WT (Fig. 3A). Since we were recording in cell-attached mode and there was no change in the slope of the I-V relationship implying no change in Maxi K conductance (126 pS), then the rightward shift implies that there is a change in membrane potential with the WNK4-transfected cells being 19 ± 4 mV more hyperpolarized. Another way to consider this effect is to remember that the unit current, iBK, through a single channel is given by

| (1) |

where γBK is the unit conductance of a Maxi K channel (slope of the I-V relationship), Vm is the membrane potential of the HEK cells, Vpipette is the potential of the pipette (usually −40 mV in most experiments), and EBK is the reversal potential of a Maxi K channel (very near EK and relatively negative). Since at every pipette potential of the I-V relationship, the current in the WNK WT-transfected cells is less than in the untreated cells, then Vm must be closer to EK (i.e., smaller driving force or more hyperpolarized).

Fig. 2.

Effect of WNK4 WT and WNK4 D321A on Maxi K activity in HEK 293 αMaxi K cells pretreated with ionomycin. HEK 293 αMaxiK stable cell lines were transiently transfected with either WNK4 WT or its mutant D321A. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were pretreated with ionomycin, after which the single-channel recordings were performed. A: representative single channel recording of Maxi K activity in the control (a), WNK WT (b), and its dead-kinase mutant D321A (DK) (c) groups. A representative Western blot shows total WNK4 and Maxi K protein expression in these cell lines (d). B: summary of the quantitative data shows the total number of channels (N; a), frequency (%) of active channel in each patch (b), and channel open probability (Po; c). *P < 0.01, WNK4 WT group compared with WNK4 DK and control groups.

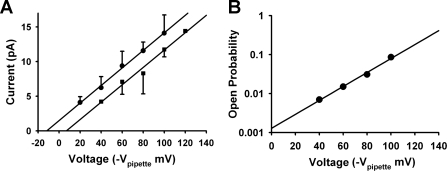

Fig. 3.

Effect of WNK4 on Maxi K channel current-voltage (I-V) relationships. A: current-voltage relationships for BK channels in untreated cells (●) and WNK4-transfected cells (■) show that transfection with WNK4 produces a rightward shift with no change in the slope of the I-V relationships, indicating no change in Maxi K conductance. The rightward shift implies that there is a change in membrane potential with the WNK4-treated cells being 19 ± 4 mV more hyperpolarized. B: to determine the voltage dependence of the Po, we measured the voltage dependence of the Maxi K channel Po and determined from the slope of log (Po) vs. V relationship that a 56-mV change produces a 10 ± 0.57-fold change in Po. This implies that the 19-mV hyperpolarization seen in A would reduce the Po by ∼2.2-fold.

Since the Po of Maxi K channels is strongly dependent on voltage, we would expect the hyperpolarization to reduce the Po of the channels in the WNK4-transfected cells. To determine approximately how much we would expect Po to change, we measured the voltage dependence of the Maxi K channel Po (Fig. 3B) and determined from the slope of log (Po) vs. V relationship that a 56-mV change produces a 10 ± 0.57-fold change in Po. This implies that 19-mV hyperpolarization would reduce the Po by ∼2.2-fold. If the Po of the WNK4-transfected cells is corrected for the change in Vm, then the Po of the WNK4-transfected cells would be ∼0.149 or almost identical to the untransfected cells (control group). Why WNK4-transfected cells should hyperpolarize is an interesting, but separate question (see discussion). Therefore, our data suggest that the WNK4-induced reduction in Maxi K channel activity is mainly due to a reduction of channel number on the cell surface membrane and that WNK4's inhibitory effect on Maxi K channel activity is kinase dependent.

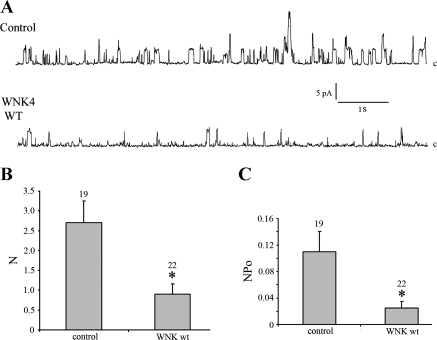

We next investigated whether WNK4 WT affects Maxi K channel activity in HEK 293 αMaxi K cells without ionomycin treatment. As shown in Fig. 4, in HEK 293 αMaxi K cells in the absence of WNK4 expression (control group), the N per patch was 2.7 ± 0.5 and NPo was 0.11 ± 0.03 at 40 mV. When HEK 293 αMaxi K cells were transfected with WNK4 WT, 12 of 22 cells had no detectable Maxi K currents. The N per patch was 0.95 ± 0.3 and NPo was 0.025 ± 0.01 at 40 mV. In these cells transfected with WNK4, there are significant reductions in N (P < 0.005) and NPo (P < 0.01) compared with the control group, an effect similar to changes in Maxi K activity in the presence of ionomycin treatment. These data suggest that WNK4 WT significantly inhibits Maxi K channel activity by reducing channel number and that this inhibition is independent of changes in intracellular Ca2+.

Fig. 4.

Effect of WNK4 on Maxi K activity in HEK 293 αMaxi K cells without ionomycin treatment. A: typical single-channel recording of Maxi K channel activity in HEK 293 αMaxiK cells. HEK 293 αMaxiK cells were either transfected with green fluorescent protein (GFP)+CD4 (control) or GFP+WNK WT. After 2–4 days of transfection, the patch-clamp technique was used to record single-channel activity in the cell-attached configuration. “c,” Channel-closed state. Upward deflections from the closed state are individual channel openings. Both continuous traces were recorded at a holding potential of 40 mV (−Vpipette). B and C: summary of the quantitative data shows the total number of channels (N; B) and channel activity (NPo; C). *P < 0.05, WNK4 WT compared with control group.

Effect of WNK4 WT and WNK4 D321A on Maxi K protein expression.

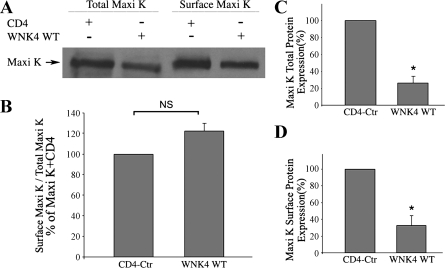

Since the inhibitory effect of WNK4 WT on Maxi K channel activity is mainly due to the reduction in Maxi K channel number on the cell surface, we further investigated whether WNK4 affects Maxi K total and cell surface protein expression. We found that WNK4 WT inhibits total Maxi K protein expression in a dose-dependent manner (data not shown), whereas WNK4 D321A does not inhibit Maxi K total expression (Fig. 2D). The cell surface and total expression of Maxi K protein were subsequently determined in the presence of WNK4 by cell surface biotinylation. As shown in Fig. 5, WNK4 significantly reduced total and surface Maxi K protein levels compared with control groups (74% reduction in total protein expression, P < 0.05, n = 3; and 68% reduction in surface expression P < 0.05, n = 3, respectively). However, there is no significant difference in the surface/total Maxi K expression ratio between the WNK4 WT group and the CD4 control group. These data suggest that the inhibitory effect of WNK4 WT on Maxi K surface expression is likely due to a reduction of total Maxi K protein expression.

Fig. 5.

Inhibitory effect of WNK4 WT on total and surface expression of Maxi K in Cos-7 cells. Cos-7 cells were cotransfected with myc-tagged Maxi K in combination with either CD4 (control) or WNK4 WT. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cell surface expression of Maxi K was determined by cell surface biotinylations (CSB) followed by Western blotting. A: representative Western blot of total and surface Maxi K protein expressions by CSB. The quantitative data show the total (C) and surface (D) Maxi K protein level and ratio of surface over total Maxi protein level (B). NS, not significant. *P < 0.05 (n = 3) compared with CD4-Ctr group.

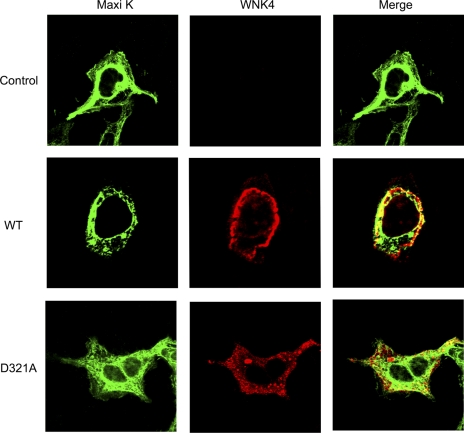

Effect of WNK4 WT and WNK4 D321A on Maxi K cellular distribution.

Using immunostaining and confocal microscopy, we further determined whether WNK4 affects Maxi K cellular distribution in HEK293 cells transfected with Maxi K and with either WNK4 WT or D321A. In the control group, HEK293 cells were only transfected with Maxi K. Maxi K in green appears to be expressed in both the cytosol and plasma membrane as seen in Fig. 6, top. In the presence of WNK4 WT (Fig. 6, middle), Maxi K is mainly distributed in the perinuclear region and its cell surface expression was remarkably reduced in HEK 293 cells, and the cell shapes were dramatically changed as well. In the presence of WNK4 D321A (Fig. 6, bottom), the Maxi K expression pattern appears to be similar to that in the control group. Total Maxi K protein expression in the presence of WNK4 WT appears to be reduced as well. In addition, both WNK4 WT and D321A appear to colocalize with Maxi K in the perinuclear region and cytosol (in yellow in the merged images).

Fig. 6.

WNK4 WT reduces the surface protein expression of Maxi K. HEK 293 cells were transiently transfected with either WNK4 WT or D321A along with myc-maxi K. Immunostaining and confocal microscopy were performed 48 h after transfection. In the control group without WNK4 expression, the Maxi K in green is expressed in both plasma membrane and cytoplasm as shown at the top. Middle: WNK4 WT expression is shown in red while both total and membrane Maxi K expressions (in green) are greatly reduced and the cell shape is changed as well. Bottom: WNK4 D321A expression is shown in red while Maxi K expression is shown in green. There is no difference in Maxi K expression between the control group and the D321A group.

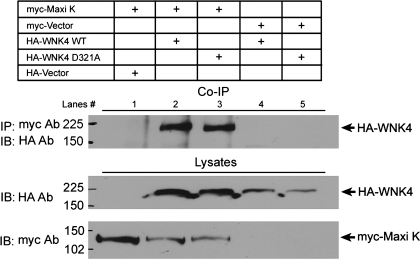

Both WNK4 WT and WNK4 D321A interact with Maxi K protein.

To find out whether WNK4 requires an interaction with Maxi K protein to modulate Maxi K activity, we performed coimmunoprecipitation experiments. As shown in Fig. 7, WNK4 WT interacts with Maxi K, but the WNK4 dead-kinase mutant D321A also interacts with Maxi K even though it no longer inhibits Maxi K activity. These data suggest that WNK4 forms a protein complex with Maxi K channels. However, it is unclear whether it is necessary for WNK4 to bind Maxi K to modulate Maxi K channel activity.

Fig. 7.

Both WNK4 WT and its dead-kinase mutant D321A interact with Maxi K. Cos-7 cells were cotransfected with heme agglutinin (HA)-WNK4 WT or WNK4 D321A in combination with myc-Maxi K as indicated. Forty-eight hours after transfection, coimmunoprecipitation (Co-IP) experiments were performed followed by Western blotting. Top: Co-IP results. Using myc antibody to IP, myc-Maxi K protein coimmunoprecipitated both WNK4 WT (lane 2) and WNK4 D321A (lane 3). Middle and bottom: WNK4 and Maxi K protein expression in cell lysates, respectively. IB, immunoblotting.

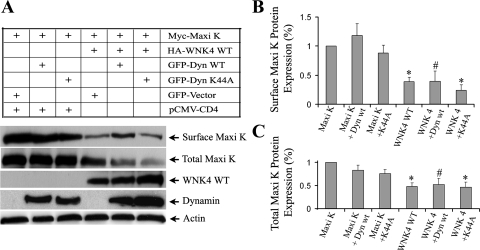

Inhibitory effect of WNK4 on Maxi K surface expression is not affected by dynamin.

Dynamin 2 WT (Dyn WT) controls the pinching-off of clathrin-coated endocytic vesicles from the plasma membrane and the budding of vesicles from the Golgi apparatus (12). A dominant-negative dynamin mutant, K44A (Dyn K44A), blocks clathrin-mediated endocytosis of many membrane proteins (31) and is also known to affect the integrity of the Golgi in some cell types (10). To further investigate whether WNK4 inhibition of Maxi K surface expression involves a dynamin-mediated pathway, we quantified Maxi K surface expression in the presence or absence of Dyn WT or Dyn K44A. As shown in Fig. 8, in the absence of WNK4 WT, Maxi K surface expression was not affected by either Dyn WT or Dyn K44A. When Cos-7 cells were cotransfected with myc-tagged Maxi K with either CD4 or WNK4 WT, Maxi K surface expression was significantly reduced in the WNK4 WT group compared with the CD4 control group (66% reduction compared with control, P < 0.001, n = 4). When Cos-7 cells were cotransfected with Maxi K and WNK4 WT in combination with either Dyn WT or Dyn K44A, the reduction of Maxi K surface expression by WNK4 WT was not further altered by the Dyn WT group (60% reduction in Dyn WT group) compared with the WNK4 WT group [66% reduction, n = 4, P = not significant (NS)] or Dyn K44A [79% reduction in Dyn K44A group compared with WNK4 WT group (66% reduction, n = 4, P = NS)]. In addition, Maxi K total protein expression was also significantly decreased in the presence of WNK4 WT. Dyn WT and Dyn K44A did not change the reduction of Maxi K total protein expression. These data suggest that the reduction of Maxi K surface expression by WNK4 is independent of the clathrin-mediated endocytosis pathway.

Fig. 8.

Inhibitory effect of WNK4 WT on Maxi K surface expression is not altered in the presence of dynamin WT or its dominant-negative mutant (K44A). A: Cos-7 cells were cotransfected with 1) either myc-tagged Maxi K and CD4 (as control) or 2) myc-tagged Maxi K and WNK4 WT, in combination with either pEGFP vector or GFP-tagged dynamin 2 wild-type (Dyn WT) or K44A (Dyn K44A), as indicated. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cell surface biotinylation was performed and followed by Western blot analysis. The protein expressions of Maxi K, WNK4 WT, dynamin, and actin were detected by a myc monoclonal antibody, GFP polyclonal antibody, and actin antibody as indicated. Actin is shown here as a protein loading control. The quantitative percent change in surface Maxi K protein expression and total Maxi K expression from the control group (Maxi K alone) are shown in B and C, respectively (n = 4). *P < 0.001 in Maxi K+WNK4 group or Maxi K+WNK4 + Dyn K44A group compared with Maxi K alone (control group), respectively. #P < 0.05 in Maxi K+WNK4+Dyn WT group compared with the control group.

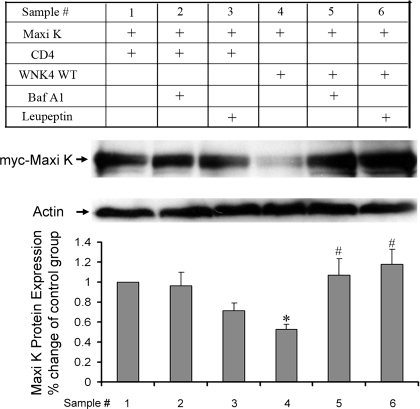

WNK4 inhibits Maxi K protein expression by enhancing the degradation of Maxi K protein through a lysosomal pathway.

Given that the inhibitory effect of WNK4 on Maxi K surface protein expression is mainly due to the reduction of total Maxi K protein expression, we further investigated whether WNK4 enhances the degradation of Maxi K protein through a lysosomal pathway. We determined the effect of V-type proton pump inhibition using bafilomycin A1 and leupeptin on Maxi K protein expression in Cos-7 cells. Bafilomycin A1 specifically inhibits the vacuolar-type H+-ATPase and thereby affects acidic proteases by disturbing the pH of endocytic organelles, including lysosomes, ultimately interfering with the lysosomal degradation pathway (14); leupeptin directly blocks most lysosomal proteases. As shown in Fig. 9, when Cos-7 cells were cotransfected with Maxi K and WNK4 WT, the steady-state protein expression of Maxi K was significantly reduced in the presence of WNK4 WT [42.3 ± 15.2% compared with control (100%), P < 0.05, n = 4]. However, in Cos-7 cells transfected with WNK4 and then pretreated with bafilomycin A1, total Maxi K protein level was significantly increased (104.5 ± 15.2%) compared with cells transfected with WNK4 WT group (47.5 ± 4.8%, P < 0.05, n = 4). In addition, leupeptin, another lysosomal inhibitor, reversed the WNK4-mediated reduction of total Maxi K expression (129.1 ± 17.4%, P < 0.05, n = 4). These data suggest that WNK4 inhibits Maxi K protein expression by enhancing the degradation of Maxi K protein through a lysosomal pathway.

Fig. 9.

Bafilomycin A1 and leupeptin reversed inhibitory effect of WNK4 WT on total Maxi K protein expression. Cos-7 cells were cotransfected with Myc-tagged Maxi K in combination with either CD4 (control) or WNK4 WT. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were treated with bafilomycin A1 (Baf A1; 0.5 μg) or leupeptin (30 μM). Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were lysed and Western blotting was then performed. A: representative Western blots of total Maxi K protein expression in the absence or presence of treatment. B: quantitative data show a total Maxi K protein level. *P < 0.05 (n = 4) compared with control (CD4) groups. #P < 0.05 (n = 4) compared with WNK4 WT group.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we report for the first time that WNK4 significantly inhibits Maxi K channel activity and its protein expression by a kinase-dependent mechanism. WNK4 inhibits Maxi K surface protein level via a mechanism that is not mediated by an increase in clathrin-dependent endocytosis, but rather by enhancing Maxi K degradation through the lysosomal pathway. This regulation of Maxi K demonstrates that WNK4 plays a broader role in the regulation of K homeostasis than just the regulation of ROMK.

The kidney plays an important role in maintaining K homeostasis. Renal K+ secretion takes place in the distal nephron, especially in CCD where both ROMK and Maxi K are expressed. ROMK is generally considered to be mainly responsible for K+ secretion during a normal-K diet (18), whereas both Maxi K and ROMK mediate K+ secretion during high K intake or when the tubular flow rate is high (3, 52). High K intake induces stimulation of renal K+ secretion. This process is mediated by both an aldosterone-dependent and an aldosterone-independent mechanism. High dietary K intake stimulates aldosterone release, which increases the activity of both Na-K-ATPase and epithelial sodium channels (ENaC) (35), ultimately leading to an increased driving force for K+ secretion in the CCD via ROMK and Maxi K channels. High dietary K intake also stimulates renal K+ secretion by an aldosterone-independent mechanism as seen in isolated, perfused CCDs from adrenalectomized rabbits (15) likely affecting Maxi K channel activity via stimulating the renal cytochrome P-450 (CYP)-epoxygenase pathway (42). Aldosterone also regulates sodium chloride cotransporter through an SGK1 and WNK4 signaling pathway (36). We now show that WNK4 modulates Maxi K activity. However, it is still unclear whether aldosterone is the upstream regulator of WNK4-mediated Maxi K regulation.

It is known that high distal tubular flow rates stimulate net K+ secretion in the distal nephron and CCD, and urinary K+ excretion (53). Maxi K channels mediate the flow-dependent K+ secretion in CCD (53). The Maxi K channel-mediated flow-dependent K+ excretion requires an increase in intracellular Ca2+ that is due to Ca2+ entry and internal store release (29). How a transient increase in intracellular Ca2+ induced by an increased tubular flow rate leads to an increase in net K+ excretion remains to be clarified. The activation of channel-mediated ion currents by a transient stimulation has been shown to be mediated by direct phosphorylation or dephosphorylation of the channels (30, 48); for example, Maxi K channel activity has been shown to be regulated by both PKA and PKC (28) as well as MAPK (27). On the other hand, members of the WNK kinase family were reported to phosphorylate various downstream kinases. WNK1 was shown to phosphorylate ERK5 via MEKK2/3 (56) and SPAK and OSR1 (46). WNK2 modulates MEK1 activity through the Rho GTPase pathway (33). WNK4 enhances the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and p38 in response to both hypertonicity and EGF (40). We also observed that WNK4 stimulates ERK1/2 phosphorylation which is involved in the response to hypertonic stimulation (data not shown). Our present data demonstrated that WNK4 WT inhibits Maxi K channel activity, whereas the WNK4 dead kinase D321A is unable to inhibit Maxi K activity, indicating that WNK4 modulates Maxi K activity via a kinase-dependent mechanism. Which downstream target(s) of the WNK4 signaling pathway regulates Maxi K channel activity is still unclear and will require further investigation.

The α-subunit of Maxi K channels contains seven transmembrane domains (from S0 to S6), a short extracellular N terminus, and a long intracellular C terminus (49). The C terminus of the Maxi K α-subunit contains four hydrophobic segments (32) and a calcium sensor which affects channel gating (39). WNK4 contains a kinase domain at its N terminus, two coiled-coil domains, and over a dozen PxxP motifs in the C terminus; the coiled-coil domains and PxxP motifs are known to be involved in protein-protein interaction. This evidence indicates that either the C termini of WNK4 or Maxi K might be the important binding sites for their interaction. Our data showed that both WNK4 WT and its dead-kinase mutant WNK4 D321A with mutated resides in the kinase domain interact with the α-subunit of Maxi K channels, suggesting that the interaction might take place between the C terminus of WNK4 and C terminus of Maxi K. However, the exact sites that are responsible for the interaction between WNK4 and Maxi K need to be further explored.

We showed that WNK4 inhibits Maxi K activity mainly due to the reduction of Maxi K channel number on the cell surface, and this reduction was observed at both a functional level with single-channel experiments and at a protein level by detecting cell-surface Maxi K protein. Under steady-state conditions, we showed that WNK4 reduced total and surface Maxi K protein expressions in an equal fashion. While reaching the new steady state, the Maxi K's insertion rate (exocytosis) to the plasma membrane should be equal to its retrieval rate (endocytosis) from the membrane. Thus this reduction of Maxi K level at the cell surface could result from the decreased total Maxi K protein abundance caused by WNK4. As shown in Fig. 8, in the presence of WNK4 WT Maxi K protein expression is reduced, but the dominant-negative dynamin mutant K44A does not further alter Maxi K protein levels. These data suggest that WNK4 inhibits Maxi K surface protein expression by a mechanism independent of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. In addition, in the absence of WNK4 WT, the dominant-negative dynamin mutant K44A does not alter the Maxi K steady-state protein abundance, suggesting the possibility that WNK4 could promote the endocytosis of Maxi K through a clathrin-independent pathway. We further found that with bafilomycin A1 and leupeptin treatments, the WNK4-induced reduction of Maxi K protein level is reversed, as shown in Fig. 9, suggesting that the reduced Maxi K abundance is likely due to increased degradation through the lysosomal pathway. WNK4 has been shown to inhibit NCC activity via enhancing the degradation of NCC through a lysosomal pathway (9, 41, 59). This evidence further supports the notion that WNK4 inhibits Maxi K activity by enhancing lysosomal degradation of Maxi K, by a mechanism similar to WNK4's inhibitory effect on NCC. How WNK4 promotes this increased degradation of Maxi K remains to be explored.

Although there was a highly significant reduction in channel density in the presence of WNK4, the question remains whether WNK4 might alter channel Po as well. A naive consideration of our results might conclude that there was an effect; however, more careful consideration calls the effect into doubt. We found that transfection with WNK4 shifts the I-V relationship of Maxi K channels to the right without a change in the slope of the I-V relationship. Since our experiments were performed on cell-attached patches, the shift implies a change in Vm. Since the Po of Maxi K channels is strongly voltage dependent, we would expect WNK4-induced hyperpolarization to reduce the Po of Maxi K channels in WNK4-treated cells. In fact, an examination of the voltage dependence of the Po in the HEK 293 αMaxi K cells suggests that, in the absence of any change in Vm, there would be little, if any, change in the Po of untreated vs. WNK4-treated cells. This reinforces the idea that the primary change induced by WNK4 is a reduction in channel number and that the reduction is dependent upon the kinase activity of WNK4. The question remains of how WNK4 hyperpolarizes the cell membrane. Since we know little about the complement of ion channels and transporters in the HEK 293 cells and even less about the ionic gradients across the cell membrane, we can only speculate about the source except to say that no previously unobserved channels appear in the WNK4-treated cells, implying that the change in potential is more likely due to a change in transporter or pump activity (such as Na-K-ATPase) rather than change in a channel activity.

In summary, our present study demonstrated that WNK4 plays an important role in the regulation of Maxi K channels that likely involves K+ secretion in the renal distal nephron.

GRANTS

This work is supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK068226 (H. Cai) and R37-DK-37963 (D. C. Eaton), National Science Foundation Grant IBN-0091964 (D. D. Denson) and National Nature Science Foundation of China Grant No. 30600108 (X. Zhang).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We greatly appreciate Dr. William B. Guggino's support in this work. We also thank Dr. Mitsi A. Blount for helpful suggestions and critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Alioua A, Mahajan A, Nishimaru K, Zarei MM, Stefani E, Toro L. Coupling of c-Src to large conductance voltage- and Ca2+-activated K+ channels as a new mechanism of agonist-induced vasoconstriction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 14560–14565, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Amberg GC, Santana LF. Downregulation of the BK channel beta1 subunit in genetic hypertension. Circ Res 93: 965–971, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bailey MA, Cantone A, Yan Q, MacGregor GG, Leng Q, Amorim JB, Wang T, Hebert SC, Giebisch G, Malnic G. Maxi-K channels contribute to urinary potassium excretion in the ROMK-deficient mouse model of Type II Bartter's syndrome and in adaptation to a high-K diet. Kidney Int 70: 51–59, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barman SA, Zhu S, White RE. PKC activates BKCa channels in rat pulmonary arterial smooth muscle via cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 286: L1275–L1281, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Behrens R, Nolting A, Reimann F, Schwarz M, Waldschutz R, Pongs O. hKCNMB3 and hKCNMB4, cloning and characterization of two members of the large-conductance calcium-activated potassium channel beta subunit family. FEBS Lett 474: 99–106, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Belfodil R, Barriere H, Rubera I, Tauc M, Poujeol C, Bidet M, Poujeol P. CFTR-dependent and -independent swelling-activated K+ currents in primary cultures of mouse nephron. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 284: F812–F828, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brenner R, Perez GJ, Bonev AD, Eckman DM, Kosek JC, Wiler SW, Patterson AJ, Nelson MT, Aldrich RW. Vasoregulation by the beta1 subunit of the calcium-activated potassium channel. Nature 407: 870–876, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Butler A, Tsunoda S, McCobb DP, Wei A, Salkoff L. mSlo, a complex mouse gene encoding “maxi” calcium-activated potassium channels. Science 261: 221–224, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cai H, Cebotaru V, Wang YH, Zhang XM, Cebotaru L, Guggino SE, Guggino WB. WNK4 kinase regulates surface expression of the human sodium chloride cotransporter in mammalian cells. Kidney Int 69: 2162–2170, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cao H, Thompson HM, Krueger EW, McNiven MA. Disruption of Golgi structure and function in mammalian cells expressing a mutant dynamin. J Cell Sci 113: 1993–2002, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chung SK, Reinhart PH, Martin BL, Brautigan D, Levitan IB. Protein kinase activity closely associated with a reconstituted calcium-activated potassium channel. Science 253: 560–562, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Conner SD, Schmid SL. Regulated portals of entry into the cell. Nature 422: 37–44, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cope G, Murthy M, Golbang AP, Hamad A, Liu CH, Cuthbert AW, O'Shaughnessy KM. WNK1 affects surface expression of the ROMK potassium channel independent of WNK4. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 1867–1874, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Drose S, Altendorf K. Bafilomycins and concanamycins as inhibitors of V-ATPases and P-ATPases. J Exp Biol 200: 1–8, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Frindt G, Palmer LG. Low-conductance K channels in apical membrane of rat cortical collecting tubule. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 256: F143–F151, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Frindt G, Palmer LG. Apical potassium channels in the rat connecting tubule. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 287: F1030–F1037, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hall SK, Armstrong DL. Conditional and unconditional inhibition of calcium-activated potassium channels by reversible protein phosphorylation. J Biol Chem 275: 3749–3754, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hebert SC, Desir G, Giebisch G, Wang W. Molecular diversity and regulation of renal potassium channels. Physiol Rev 85: 319–371, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Helms MN, Chen XJ, Ramosevac S, Eaton DC, Jain L. Dopamine regulation of amiloride-sensitive sodium channels in lung cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 290: L710–L722, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jones HM, Hamilton KL, Papworth GD, Syme CA, Watkins SC, Bradbury NA, Devor DC. Role of the NH2 terminus in the assembly and trafficking of the intermediate conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel hIK1. J Biol Chem 279: 15531–15540, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kaczorowski GJ, Knaus HG, Leonard RJ, McManus OB, Garcia ML. High-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels; structure, pharmacology, and function. J Bioenerg Biomembr 28: 255–267, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kahle KT, Wilson FH, Leng Q, Lalioti MD, O'Connell AD, Dong K, Rapson AK, MacGregor GG, Giebisch G, Hebert SC, Lifton RP. WNK4 regulates the balance between renal NaCl reabsorption and K+ secretion. Nat Genet 35: 372–376, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kahle KT, Wilson FH, Lifton RP. Regulation of diverse ion transport pathways by WNK4 kinase: a novel molecular switch. Trends Endocrinol Metab 16: 98–103, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lagrutta A, Shen KZ, North RA, Adelman JP. Functional differences among alternatively spliced variants of Slowpoke, a Drosophila calcium-activated potassium channel. J Biol Chem 269: 20347–20351, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lazrak A, Liu Z, Huang CL. Antagonistic regulation of ROMK by long and kidney-specific WNK1 isoforms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 1615–1620, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Leng Q, Kahle KT, Rinehart J, MacGregor GG, Wilson FH, Canessa CM, Lifton RP, Hebert SC. WNK3, a kinase related to genes mutated in hereditary hypertension with hyperkalaemia, regulates the K+ channel ROMK1 (Kir1.1) J Physiol 571: 275–286, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Li D, Wang Z, Sun P, Jin Y, Lin DH, Hebert SC, Giebisch G, Wang WH. Inhibition of MAPK stimulates the Ca2+-dependent big-conductance K channels in cortical collecting duct. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 19569–19574, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Liu W, Wei Y, Sun P, Wang WH, Kleyman TR, Satlin LM. Mechanoregulation of BK channel activity in the mammalian cortical collecting duct (CCD): role of protein kinases A and C. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297: F904–F915, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Liu W, Xu S, Woda C, Kim P, Weinbaum S, Satlin LM. Effect of flow and stretch on the [Ca2+]i response of principal and intercalated cells in cortical collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 285: F998–F1012, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lu R, Alioua A, Kumar Y, Eghbali M, Stefani E, Toro L. MaxiK channel partners: physiological impact. J Physiol 570: 65–72, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McNiven MA, Cao H, Pitts KR, Yoon Y. The dynamin family of mechanoenzymes: pinching in new places. Trends Biochem Sci 25: 115–120, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Meera P, Wallner M, Song M, Toro L. Large conductance voltage- and calcium-dependent K+ channel, a distinct member of voltage-dependent ion channels with seven N-terminal transmembrane segments (S0–S6), an extracellular N terminus, and an intracellular (S9–S10) C terminus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 14066–14071, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Moniz S, Matos P, Jordan P. WNK2 modulates MEK1 activity through the Rho GTPase pathway. Cell Signal 20: 1762–1768, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pacha J, Frindt G, Sackin H, Palmer LG. Apical maxi K channels in intercalated cells of CCT. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 261: F696–F705, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rossier BC, Canessa CM, Schild L, Horisberger JD. Epithelial sodium channels. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 3: 487–496, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rozansky DJ, Cornwall T, Subramanya AR, Rogers S, Yang YF, David LL, Zhu X, Yang CL, Ellison DH. Aldosterone mediates activation of the thiazide-sensitive Na-Cl cotransporter through an SGK1 and WNK4 signaling pathway. J Clin Invest 119: 2601–2612, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sansom SC. Reemergence of the maxi K+ as a K+ secretory channel. Kidney Int 71: 1322–1324, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Satlin LM, Palmer LG. Apical K+ conductance in maturing rabbit principal cell. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 272: F397–F404, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schreiber M, Salkoff L. A novel calcium-sensing domain in the BK channel. Biophys J 73: 1355–1363, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shaharabany M, Holtzman EJ, Mayan H, Hirschberg K, Seger R, Farfel Z. Distinct pathways for the involvement of WNK4 in the signaling of hypertonicity and EGF. FEBS J 275: 1631–1642, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Subramanya AR, Liu J, Ellison DH, Wade JB, Welling PA. WNK4 diverts the thiazide-sensitive NaCl cotransporter to the lysosome and stimulates AP-3 interaction. J Biol Chem 284: 18471–18480, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sun P, Liu W, Lin DH, Yue P, Kemp R, Satlin LM, Wang WH. Epoxyeicosatrienoic acid activates BK channels in the cortical collecting duct. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 513–523, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Taniguchi J, Guggino WB. Membrane stretch: a physiological stimulator of Ca2+-activated K+ channels in thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 257: F347–F352, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tian L, Duncan RR, Hammond MS, Coghill LS, Wen H, Rusinova R, Clark AG, Levitan IB, Shipston MJ. Alternative splicing switches potassium channel sensitivity to protein phosphorylation. J Biol Chem 276: 7717–7720, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Toro L, Wallner M, Meera P, Tanaka Y. Maxi-K(Ca), a unique member of the voltage-gated K channel superfamily. News Physiol Sci 13: 112–117, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Vitari AC, Deak M, Morrice NA, Alessi DR. The WNK1 and WNK4 protein kinases that are mutated in Gordon's hypertension syndrome phosphorylate and activate SPAK and OSR1 protein kinases. Biochem J 391: 17–24, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wade JB, Fang L, Liu J, Li D, Yang CL, Subramanya AR, Maouyo D, Mason A, Ellison DH, Welling PA. WNK1 kinase isoform switch regulates renal potassium excretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 8558–8563, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wang J, Zhou Y, Wen H, Levitan IB. Simultaneous binding of two protein kinases to a calcium-dependent potassium channel. J Neurosci 19: RC4, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wang SX, Ikeda M, Guggino WB. The cytoplasmic tail of large conductance, voltage- and Ca2+-activated K+ (MaxiK) channel is necessary for its cell surface expression. J Biol Chem 278: 2713–2722, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wang WH, Giebisch G. Regulation of potassium (K) handling in the renal collecting duct. Pflügers Arch 458: 157–168, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wilson FH, Disse-Nicodeme S, Choate KA, Ishikawa K, Nelson-Williams C, Desitter I, Gunel M, Milford DV, Lipkin GW, Achard JM, Feely MP, Dussol B, Berland Y, Unwin RJ, Mayan H, Simon DB, Farfel Z, Jeunemaitre X, Lifton RP. Human hypertension caused by mutations in WNK kinases. Science 293: 1107–1112, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Woda CB, Bragin A, Kleyman TR, Satlin LM. Flow-dependent K+ secretion in the cortical collecting duct is mediated by a maxi-K channel. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 280: F786–F793, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Woda CB, Miyawaki N, Ramalakshmi S, Ramkumar M, Rojas R, Zavilowitz B, Kleyman TR, Satlin LM. Ontogeny of flow-stimulated potassium secretion in rabbit cortical collecting duct: functional and molecular aspects. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 285: F629–F639, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wu SN, Wang YJ, Lin MW. Potent stimulation of large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels by rottlerin, an inhibitor of protein kinase C-delta, in pituitary tumor (GH3) cells and in cortical neuronal (HCN-1A) cells. J Cell Physiol 210: 655–666, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Xu B, English JM, Wilsbacher JL, Stippec S, Goldsmith EJ, Cobb MH. WNK1, a novel mammalian serine/threonine protein kinase lacking the catalytic lysine in subdomain II. J Biol Chem 275: 16795–16801, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Xu BE, Stippec S, Lenertz L, Lee BH, Zhang W, Lee YK, Cobb MH. WNK1 activates ERK5 by an MEKK2/3-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem 279: 7826–7831, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Yu L, Eaton DC, Helms MN. Effect of divalent heavy metals on epithelial Na+ channels in A6 cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F236–F244, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Yue P, Lin DH, Pan CY, Leng Q, Giebisch G, Lifton RP, Wang WH. Src family protein tyrosine kinase (PTK) modulates the effect of SGK1 and WNK4 on ROMK channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 15061–15066, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Zhou B, Zhuang J, Gu D, Wang H, Cebotaru L, Guggino WB, Cai H. WNK4 enhances the degradation of NCC through a sortilin-mediated lysosomal pathway. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 82–92, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Zhou XB, Arntz C, Kamm S, Motejlek K, Sausbier U, Wang GX, Ruth P, Korth M. A molecular switch for specific stimulation of the BKCa channel by cGMP and cAMP kinase. J Biol Chem 276: 43239–43245, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]