Abstract

The nature of water’s interaction with biomolecules such as proteins has been difficult to examine in detail at atomic resolution. Solution NMR spectroscopy is potentially a powerful method for characterizing both the structural and temporal aspects of protein hydration but has been plagued by artifacts. Encapsulation of the protein of interest within the aqueous core of a reverse micelle particle results in a general slowing of water dynamics, significant reduction in hydrogen exchange chemistry and elimination of contributions from bulk water thereby enabling the use of nuclear Overhauser effects to quantify interactions between the protein surface and hydration water. Here we extend this approach to allow use of dipolar interactions between hydration water and hydrogens bonded to protein carbon atoms. By manipulating the molecular reorientation time of the reverse micelle particle through use of low viscosity liquid propane, the T1ρ relaxation time constants of 1H bonded to 13C were sufficiently lengthened to allow high quality rotating frame nuclear Overhauser effects to be obtained. These data supplement previous results obtained from dipolar interactions between the protein and hydrogens bonded to nitrogen and in aggregate cover the majority of the molecular surface of the protein. A wide range of hydration dynamics is observed. Clustering of hydration dynamics on the molecular surface is also seen. Regions of long-lived hydration water correspond with regions of the protein that participate in molecular recognition of binding partners implying that the contribution of the solvent entropy to the entropy of binding has been maximized through evolution.

Keywords: protein hydration, water dynamics, NMR spectroscopy, hydrophobic effect, protein-protein interaction, protein thermodynamics, protein encapsulation, reverse micelles

Since the seminal works of Tanford,1 Kauzmann2 and their contemporaries, the nature of water as a biological solvent has been a topic of deep interest and remains so today.3,4 Nevertheless, the present view of water behavior near macromolecular surfaces comes largely from analyses of molecular dynamics and related simulations that have been difficult to validate experimentally. There are a host of detailed technical issues that have prevented experimental characterization of macromolecular hydration in solution but they generally arise from two fundamental qualities of aqueous solutions: water molecules are incredibly numerous and they move very fast. These two factors have conspired to create problems in both temporal and spatial resolution of measurements in aqueous solution such that the experimental insight into protein solvation is surprisingly limited.

The collection of one to two layers of water surrounding macromolecules is generally referred to as the hydration layer and is now commonly termed ‘hydration water’5 or ‘biological water’.6 Measurements using magnetic relaxation dispersion,5 time-resolved optical spectroscopy,6 and other methods7,8 have demonstrated that hydration waters are dynamically slowed relative to bulk water, though the estimated degree of retardation varies from 2-fold to 2 orders of magnitude,9 and that this dynamic slowing extends, on average, one to two water layers outward from the protein surface. Though this general picture is now largely accepted, the range of motion within the hydration layer and the mechanism by which the macromolecular surface influences motion of hydration water remain poorly understood. Nevertheless, it is well known that specific interactions between biomolecules are often mediated by water molecules, and that water has a variety of important direct catalytic roles in biochemical processes.3 Perhaps most importantly, whether a given biomolecular interfacial interaction is wet or dry, it is clearly affected by the energetics of desolvating the interacting surfaces during the binding process. The orientations and motions of hydration water molecules directly determine the degree to which such desolvation is favorable or unfavorable.10,11 Thus a complete description of binding energetics requires a better understanding of hydration on the atomic scale.

Experimental access to a site-resolved view of hydration has relied upon fluorescence6,12–14 and EPR15 based methods. Both approaches require mutation of the protein of interest such that probes are moved, one site at a time, throughout the molecule. In principle, solution NMR could provide comprehensive access to site-resolved measurement of protein-water interactions via dipolar magnetization exchange between protein hydrogens and water hydrogens.16 Though this approach has provided extensive insight into the residence time and location of internal water molecules integral to protein structure (i.e. “structural” water), three severe technical limitations have prevented its use for detection of hydration water.17 Despite the slowing of the of waters in the hydration layer, they still move too fast to allow efficient build up of dipolar magnetization exchange.17 In addition, interpretation of such signals is clouded by contributions from hydrogen exchange between water and labile protein hydrogens. Dipolar exchange and chemical exchange can be distinguished by comparison of both the laboratory-frame nuclear Overhauser effect (NOE) and the rotating-frame NOE (ROE).17 In the slow tumbling limit, the NOE and ROE are of opposite sign while hydrogen exchange produces NOE and ROE of identical sign. Unfortunately, ambiguity arises when a protein hydrogen HA is exchanged with a hydrogen derived from a water molecule and is then followed by intramolecular dipolar exchange between protein hydrogens HA and HB. This mechanism results in NOE and ROE intensity of opposite sign between the remote protein hydrogen HB resonance and the water resonance, producing a signal which is indistinguishable from direct dipolar magnetization exchange between hydrogen HB and water. A further complication to measurements of protein-water NOEs in aqueous solution comes from the potential for long-range dipolar coupling with hydrogens of bulk solvent.18–20 It has been argued that the usual r−6 dependence associated with the intramolecular NOE and ROE can be effectively reduced to r−1 rendering the entire approach useless.5,21

Encapsulation of a protein of interest within a reverse micelle largely overcomes these limitations.22 Reverse micelles have been used to encapsulate a wide range of soluble proteins as well as integral membrane and peripheral membrane proteins with high structural and functional fidelity, making the full arsenal of high-resolution multi-dimensional NMR experiments accessible.23–28 In the present case, several novel qualities of the reverse micelle provide a means to surmount the aforementioned difficulties in using solution NMR methods to characterize protein hydration. The nanometer scale water pool has significantly slowed water dynamics; the effective rate of hydrogen exchange is slowed by at least two orders of magnitude; and the vast majority of solvent water present in a normal aqueous sample is absent in a reverse micelle preparation. These features have enabled use of the NOE and ROE to provide comprehensive site resolved information about protein hydration.22

We have previously used this approach for measurement of protein-water interactions using 15N-resolved NOESY and ROESY spectra.22 This provides information about solvation at or near amide hydrogens in the protein. Using the 76 amino acid protein ubiquitin as a test case, we showed that the protein has a highly variable range of dynamics and that clustering of regions of hydration water dynamics is apparent. Here, we extend the previous studies using 13C-resolved measurements. Unfortunately the reverse micelle particle containing a single ubiquitin molecule and a well-defined amount of water is a large particle that tumbles with an effective rotational correlation time on the order of 10 ns in pentane. In pentane, where the previous 15N-resolved studies were done, this results in 1H{−13C} T1ρ values that are too short to allow high S/N 13C-resolved ROESY spectra to be obtained. To increase the 1H T1ρ values, solutions of encapsulated ubiquitin were prepared in liquid propane, which has a bulk viscosity slightly less than one half that of pentane at the encapsulation pressures used. The effective rotational correlation time of the encapsulated protein is reduced to ~5 ns providing a concomitant reduction in 1H T1ρ relaxation rates (Table S1). Three-dimensional 13C-resolved NOESY and ROESY spectra were collected on uniformly 15N,13C-ubiquitin in AOT reverse micelles dissolved in liquid propane using a mixing time of 35 ms, which is within the linear build-up regime for the NOE but not for the ROE. The ROE was corrected using the measured 1H T1ρ values as described by Macura & Ernst.29

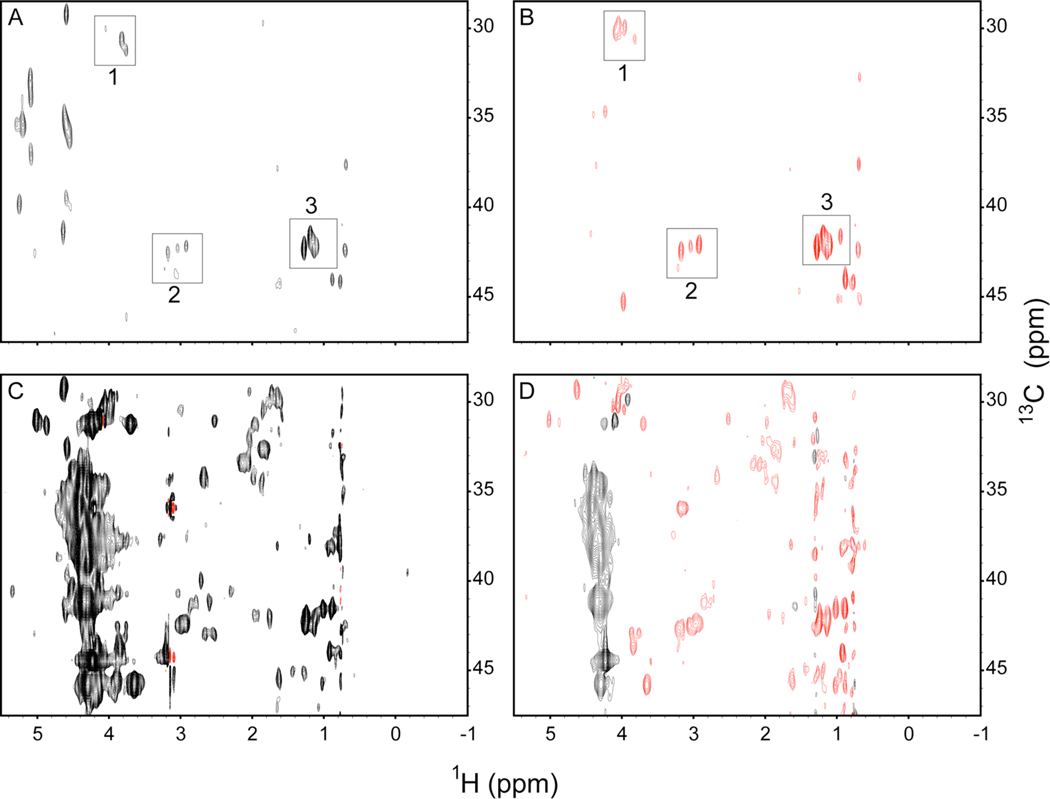

The indirect 1H planes at the water resonance of these experiments are shown in Figure 1. Also shown are the water planes of identical measurements on aqueous ubiquitin. The aqueous ubiquitin spectra show only a handful of peaks centered at the water resonance, all of which come from sites that are within NOE distance (~3.3 Å in this case) of labile side chain hydroxyl or amine hydrogens and are likely the result of artifactual hydrogen-exchange mediated indirect magnetization transfer pathways.21 The reverse micelle spectra, however, show dozens of cross peaks centered at the water resonance which are resolved from Hα cross peaks. The opposite phase of the ROE and NOE peaks indicate that these cross peaks arise from direct dipolar exchange between protein hydrogens and solvating water.17 There is ample evidence from these spectra that the rate of hydrogen exchange is significantly slowed. For example, intramolecular NOE cross peaks to most of the exchangeable Thr OH were observed indicating that they remain in slow exchange on the chemical shift time scale (kex << 10 s−1). A detailed example is provided in Figure S1. A likely explanation for the effective slowing of hydrogen exchange is that the dissociation of water is slow enough30 to make collision of reverse micelles and exchange of their aqueous cores rate limiting for the availability of hydroxide ion catalyst.31 The slowed dynamics of water may also contribute. Regardless, the protein-water cross peaks seen in the reverse micelle spectra in Figure 1 are clearly the result of direct protein-water dipolar exchange. Only the hydroxyl of the lone Tyr residue presents a potential complication. Importantly, there are no NOEs (ROEs) to water from probes not within NOE distance of the surface, which indicates the selectivity of the method and absence of water within in the core of the protein. Finally, we note that long-range coupling to water is minimal in reverse micelles due simply to the lack of bulk water created by the nature of the sample. It is interesting to note that 1H-1H projections of 15N-resolved NOESY experiments of encapsulated 15N, 2H-ubiquitin dissolved in either 98% deuterated pentane or 10% deuterated pentane are indistinguishable indicating an absence of significant long-range coupling between the protein and bulk alkane solvent in the reverse micelle system (Figure S2).

Figure 1.

Protein-water NOE and ROE measurements. Indirect 1H planes of 13C-resolved NOESY (A, C) and ROESY (B, D) spectra of uniformly 15N,13C-ubiquitin in aqueous solution (A, B: indirect 1H plane at 4.9 p.p.m.) or in AOT reverse micelles with a water loading (W0) of 9 dissolved in liquid propane (C, D: indirect 1H plane at 4.35 p.p.m.) are shown. An NOE (ROE) mixing time of 35 ms was used. Dipolar cross peaks are indicated by positive (black) NOE and negative (red) ROE. The cross peaks centered at the water resonance of the aqueous solution spectrum are boxed in panels A and B. Crosspeaks appearing between 4 and 5 p.p.m. corresponds to the edges of auto-peaks while the unboxed peaks near 1 p.p.m. are intramolecular NOEs from methyl hydrogens to Hαs and are not centered at the water resonance. In aqueous solution, the cross peaks centered at the water resonance are due to sites within detectable NOE distance (≤ 3.3 Å in this case) of labile hydrogens (1 - Thr Hβs, 2 – Ser Hβs and Lys Hεs, 3 – Thr Hγs). In contrast, the corresponding spectra of ubiquitin encapsulated with a reverse micelle show a multitude of cross peaks from a wide variety of sites, each of which shows a negative ROE indicating direct dipolar exchange between a protein site and water.

The ratio of cross relaxation rates of the NOE (σNOE) to the ROE (σROE) can be used as a quantitative measure of protein-water interactions. Ratios of the NOE to ROE peak intensities obtained at a mixing time of 35 ms were used to calculate σNOE/σROE for the 37 13C-resolved NOE/ROE that could be quantitatively interpreted (Table S1). This almost doubles the number of hydration probes and increases the surface area coverage by nearly 50% relative to the 15N-resolved data reported previously.22 The σNOE/σROE ratios range from 0 to −0.5. A σNOE/σROE ratio of −0.5 corresponds to an interaction with water which is in the slow tumbling limit and is dictated by the rotational correlation time of the protein.17 In the absence of hydrogen-exchange mediated indirect magnetization transfer, which is the case here, σNOE/σROE ratios between −0.5 and 0 are indicative of interaction times shorter than the rotational correlation time of the protein.16,17,32 At the magnetic field strength used here, the NOE approaches zero at an effective correlation time of ~300 ps.17 It should be emphasized that the dynamical effects have both a distance and angular dependence leading to potentially complicated detailed origins for the scaling of obtained σNOE/σROE ratios from the slow tumbling limit.32

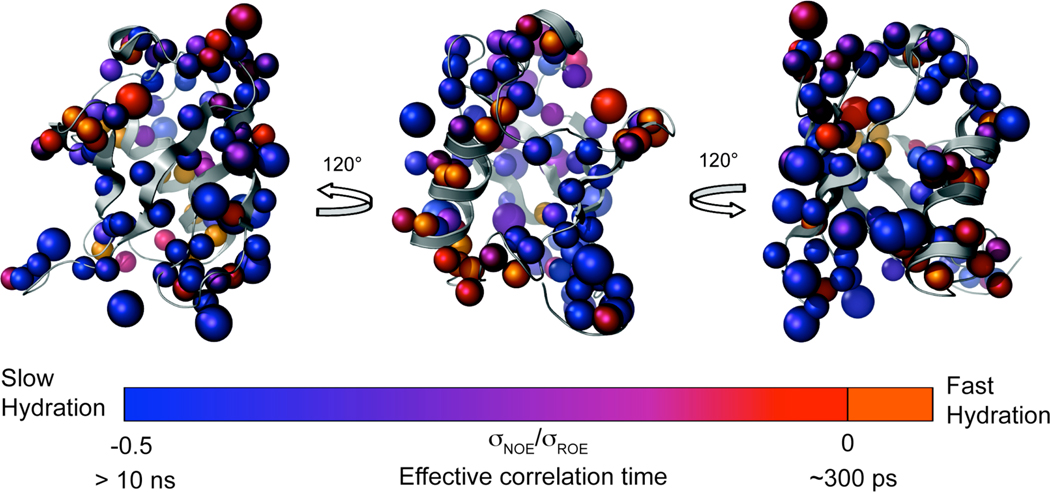

The σNOE/σROE ratios are given in Supplementary Table S1 and are mapped onto the structure of ubiquitin in Figure 2. As was seen in the previous analysis of 15N-bonded hydrogens22, a minority of 13C-bonded hydrogens show σNOE/σROE ratios at the slow tumbling limit of a rigid interaction and the entire dynamic range of σNOE/σROE ratios is sampled. The present 13C-resolved data were combined with previously obtained 15N-resolved measurements to more completely delineate the nature of the hydration surface of the protein. The previous 15N-resolved measurements were undertaken in liquid pentane in which the encapsulated ubiquitin has an approximately two-fold longer molecular reorientation time. Similar experiments carried out in liquid propane resulted in σNOE/σROE ratios that were within experimental error of those obtained in liquid pentane. It is also important to point out that the present measurements were performed using 15N, 13C-ubiquitin whereas the previous work was performed using 15N,2H-ubiquitin. As a result the resolution of water cross peaks from Hα cross peaks was far superior in the earlier work, hence the use of this earlier data in assembling the map of ubiquitin hydration dynamics in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Hydration dynamics at the surface ubiquitin. A ribbon representation of the structure encapsulated human ubiquitin (PDB code 1G6J, conformer 25)24 is shown. Hydration probes sites are represented as spheres. Probe sites with unique hydrogen chemical shifts are shown as small spheres at the location of the probe hydrogen. Probe sites that are degenerate, such as the hydrogens of a methyl group whose chemical shifts are averaged, are shown as large spheres at the location of the carbon to which the probe hydrogens are bonded. The spheres are colored according to the probe σNOE/σROE values. σNOE/σROE ratios near −0.5 indicate the slowest hydration dynamics while values near 0 are the regions of fast hydration dynamics. Backbone amide hydrogens which are solvent-exposed but showed no cross peaks to solvent22 are colored orange. These sites are interpreted as the locations of fastest hydration dynamics. The carbon-resolved hydration dynamic data corresponds well with the 15N-resolved measurements. Sites in the rigid limit have residence times and surface dynamics slower than 10 ns. Sites showing no NOE but a detectable ROE have effective correlation times on the order of 300 ps. Intermediate σNOE/σROE values potentially arise from a complicated scaling due to both the time scale of motion and its geometric details.32

In addition to the obvious clustering of the fast hydration dynamic sites, there is also clear grouping of sites where interactions with water are quite long-lived. The cluster of dark blue sites along the outer surface of the mixed β-sheet and along the interface of the β-sheet and α-helix indicates regions of protein surface with greatly slowed hydration dynamics. Intermediate hydration dynamic clusters (purple) are also evident, particularly around the 310 helix. The apparent clustering of hydration dynamics evident in Figure 2 is most intriguing and is more fully visualized in Figure 3. The wide coverage and range of these data represent the most extensive measurements of hydration dynamic behavior to date.

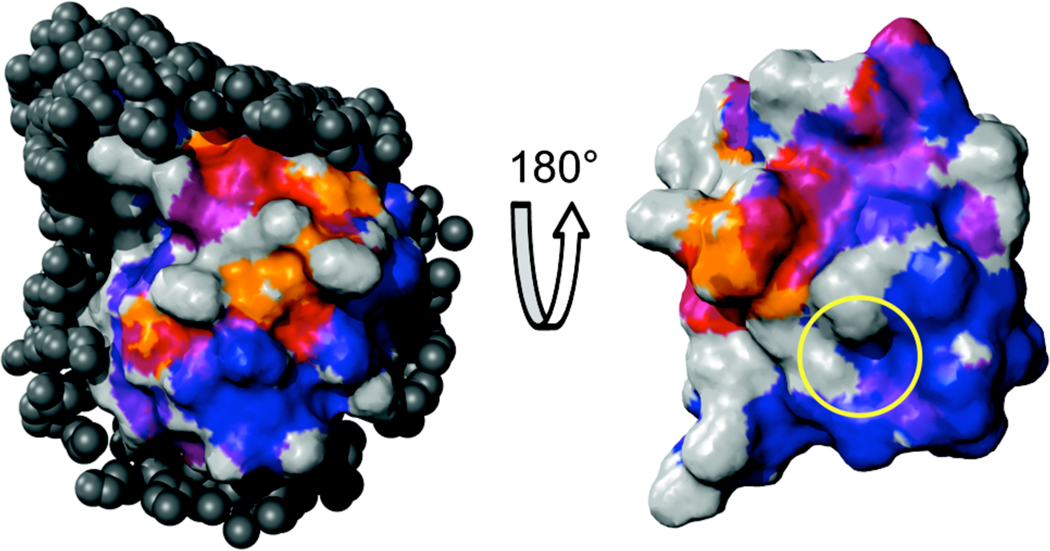

Figure 3.

The ubquitin hydration surface and comparison to its protein-protein interaction surface. Two views of the molecular surface of ubiquitin are shown. The surface is color-coded according to the average σNOE/σROE values of all probes within NOE detection distance from −0.5 (blue) to 0 (red). σNOE/σROE ratios near −0.5 indicate the slowest hydration dynamics while values near 0 are the regions of fast hydration dynamics. Surface points which are within NOE distance of solvent-exposed backbone amide sites but did not show cross peaks to water in the previously-obtained 15N-resolved hydration experiments22 and were not within NOE distance of any other hydration probes are colored orange. These sites are interpreted as the locations of fastest hydration dynamics. Surface points not within NOE distance of any usable hydration dynamics probe site are colored gray. Patches of tightly bound hydration water and of intermediate hydration dynamics are readily evident. Hydration dynamics are mapped for approximately 70% of the ubiquitin surface. Eighteen crystal structures of ubiquitin (details and references given in Supplementary Information) in macromolecular complexes were aligned with the structure24 of encapsulated ubiquitin (PDB ID 1G6J). All non-ubiquitin heavy atoms within 6 Å of ubiquitin in the various complexes are shown as dark gray spheres (left panel). The regions of ubiquitin with the most dynamic hydration behavior are excluded from the protein-protein interface in all of these complexes. A rotated view of the hydration surface with the atoms of the ubiquitin binding partners removed is also shown to illustrate the hydration dynamics of the interfacial surface of ubiquitin (right panel). The hydrophobic patch,36 which is involved in a host of ubiquitin binding interactions, is indicated with a yellow circle.

The large patches of similar hydration dynamics speak to persistent questions about the potential role of water in protein structure-function relationships and molecular evolution.3,4,11,17,33,34 Ubiquitin is involved in a host of critical protein-protein interactions that regulate protein degradation pathways.35 Many ubiquitin binding interactions are mediated by the hydrophobic patch formed by the side chains of Ile-44, Leu-8, and Val-70.36 A recent analysis37 compared the ms-µs motions within ubiquitin with a series of crystal structures of ubiquitin in complex with various binding partners and found correlations between binding and protein motion. This motivated comparison of the hydration dynamics surface with the same series of 18 complexes (see Table S2). We aligned ubiquitin in each of the 18 crystal structures with the structure of encapsulated ubiquitin and examined whether specific portions of the protein’s surface were excluded from the complex interfaces. The protein-protein interfaces center on the hydrophobic patch indicated with a yellow circle in Figure 3. The outer surface of the α- helix is generally excluded from these protein-protein binding interactions (Figure 3, left panel). This portion of the ubiquitin surface contains the largest patch of fast hydration dynamics seen in the present measurements (colored orange, purple and red). Conversely, the opposite face of the protein, which is heavily involved in protein-protein contacts, is composed mostly of sites with restricted hydration dynamics (Figure 3, right panel).

The correlation of a fast hydration dynamic portion of protein surface being seemingly excluded from a wide variety of ubiquitin’s protein-protein interactions as well as the generally slowed hydration surface being buried in these complexes suggests a potential functional or evolutionary relevance. This correlation is easily rationalized if we consider the nature of desolvation in protein-protein interactions.38,39 The hydrophobic effect1,2,40 predicts that burial of hydrophobic surface produces an entropic advantage to the free energy of a given interaction and comes from the liberation of interfacial water molecules. As the entropy of bulk water should be essentially constant, the difference in the desolvation entropy of one region of protein surface versus another will primarily be determined by the difference in the entropy of the local hydration layer. The entropy of the hydration layer should be directly related to the degree of motional restriction imposed by these regions of protein surface on the solvating water. If the protein surface imposes considerable motional restriction on the local hydration water molecules while another imposes relatively little, then it follows41 that the more restrictive site will provide a more favorable entropic gain when desolvated. The present analysis suggests that such differential desolvation may play an important role in the binding of ubiquitin to its various targets and the methods used here would offer a new window into this previously underappreciated aspect of molecular recognition and evolution.38,39 More systems will need to be examined to determine if the variation of the residual translation-rotational entropy of hydration water is generally involved in the thermodynamics of protein-protein interactions but the initial observation here is undoubtedly provocative.

Related to this is the issue of so-called cold denaturation of proteins. The observed large positive change in heat capacity upon unfolding demands that proteins exhibit both thermal and cold-induced unfolding.42 In addition, a statistical thermodynamic view of the cooperative substructure of proteins suggests that cold denaturation should be non-cooperative in many cases, particularly in situations where interactions within units of cooperative substructure are qualitatively distinct from those between units of cooperative substructure.43 This is in sharp contrast to the highly cooperative apparently two-state high temperature unfolding that is predicted by the same theory and is generally observed experimentally.44 Taking advantage of the fact that the water core of reverse micelles resists freezing, we have used encapsulated proteins to examine this issue and observed the predicted multi-state nature of protein cold denaturation.43 These results have been challenged on a variety of technical grounds45 that have largely been answered46 but a recent study47 has raised an apparent paradox that is resolved by the observations presented here. Using emulsions with cavities on the micron length-scale, Halle and coworkers failed to detect magnetic relaxation dispersion of the water pool that would be indicative of cold induced unfolding of ubiquitin.47 As they emphasize, technical issues aside, cold denaturation is principally driven by the hydrophobic effect, which finds its roots in the entropy of water. The results presented here establish that the water within the reverse micelle, both free and protein-associated, has significantly reduced entropy relative to the essentially bulk water of the micron scale emulsion cavities. This would raise the temperature at which cold-induced unfolding occurs in the reverse micelle but not in the micron scale emulsion and thereby resolves the apparent paradox.

In conclusion, use of 13C-resolved NOESY and ROESY experiments in combination with the technical advantages offered by reverse micelle encapsulation has significantly expanded the characterization of the hydration dynamics at the surface of ubiquitin. Clustering of reduced motion of the hydration water correlates with surface that forms interfaces of protein-protein complexes while the opposite is true for regions that do not contribute to protein-protein complex formation. This suggests that the protein surface has evolved to maximize the entropy gain arising from exclusion of hydration water to form a dry protein-protein interface.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Sabrina Bèdard, Kathleen Valentine, John Gledhill and Veronica Moorman for helpful discussions and technical assistance. We are indebted to Professor Bertil Halle for extensive and valuable discussion. A.J.W. declares a competing financial interest as a Member of Daedalus Innovations, LLC, a manufacturer of high pressure and reverse micelle NMR apparatus.

Funding Sources

Supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation (MCB-0842814) and a NIH postdoctoral fellowship (GM 087099) to N.V.N.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information. A summary of sample preparation, NMR spectroscopy, analytical methods, illustration of slowed hydrogen exchange and absence of long-range NOEs to alkane solvent. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.”

Supporting Information Placeholder

REFERENCES

- 1.Tanford C. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979;76:4175. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kauzmann W. Adv Protein Chem. 1959;14:1. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60608-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ball P. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:74. doi: 10.1021/cr068037a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chandler D. Nature. 2005;437:640. doi: 10.1038/nature04162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halle B. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London, Ser. B. 2004;359:1207. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pal SK, Zewail AH. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:2099. doi: 10.1021/cr020689l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wernet P, Nordlund D, Bergmann U, Cavalleri M, Odelius M, Ogasawara H, Naslund LA, Hirsch TK, Ojamae L, Glatzel P, Pettersson LGM, Nilsson A. Science. 2004;304:995. doi: 10.1126/science.1096205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zaccai G. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London, Ser. B. 2004;359:1269. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raschke TM. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 2006;16:152. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Timasheff SN. Biochemistry. 2002;41:13473. doi: 10.1021/bi020316e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Plumridge TH, Waigh RD. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 2002;54:1155. doi: 10.1211/002235702320402008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qiu WH, Kao YT, Zhang LY, Yang Y, Wang LJ, Stites WE, Zhong DP, Zewail AH. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:13979. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606235103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stevens JA, Link JJ, Kao YT, Zang C, Wang LJ, Zhong DP. Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2010;114:1498. doi: 10.1021/jp910013f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang LY, Yang Y, Kao YT, Wang LJ, Zhong DP. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2009;131:10677. doi: 10.1021/ja902918p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Armstrong BD, Choi J, Lopez C, Wesener DA, Hubbell W, Cavagnero S, Han S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:5987. doi: 10.1021/ja111515s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Otting G, Liepinsh E, Wuthrich K. Science. 1991;254:974. doi: 10.1126/science.1948083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Otting G. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 1997;31:259. doi: 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frezzato D, Rastrelli F, Bagno A. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006;110:5676. doi: 10.1021/jp0560157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Halle B. J. Chem. Phys. 2003;119:12372. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jeener J, Vlassenbroek A, Broekaert P. J. Chem. Phys. 1995;103:1309. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Modig K, Liepinsh E, Otting G, Halle B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:102. doi: 10.1021/ja038325d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nucci NV, Pometun MS, Wand A. J. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011 doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wand AJ, Ehrhardt MR, Flynn PF. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998;95:15299. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Babu CR, Flynn PF, Wand AJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:2691. doi: 10.1021/ja005766d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kielec JM, Valentine KG, Babu CR, Wand AJ. Structure. 2009;17:345. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lefebvre BG, Liu W, Peterson RW, Valentine KG, Wand AJ. J Magn Reson. 2005;175:158. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peterson RW, Anbalagan K, Tommos C, Wand AJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:9498. doi: 10.1021/ja047900q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Valentine KG, Peterson RW, Saad JS, Summers MF, Xu X, Ames JB, Wand AJ. Structure. 2010;18:9. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Macura S, Huang Y, Suter D, Ernst RR. Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 1981;43:259. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eigen M. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1964;3:1. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carlström G, Halle B. Mol. Phys. 1988;64:659. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brüschweiler R, Wright PE. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1994;229:75. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bagchi B. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:3197. doi: 10.1021/cr020661+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chandler D. Nature. 2002;417:491. doi: 10.1038/417491a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hershko A, Ciechanover A. Ann. Rev. Biochem. 1998;67:425. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peters J-M, Harris JR, Finley D. Ubiquitin and the biology of the cell. New York: Plenum Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lange OF, Lakomek NA, Fares C, Schroder GF, Walter KFA, Becker S, Meiler J, Grubmuller H, Griesinger C, de Groot BL. Science. 2008;320:1471. doi: 10.1126/science.1157092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wei BQ, Baase WA, Weaver LH, Matthews BW, Shoichet BK. J Mol Biol. 2002;322:339. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00777-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolfenden R. Biophys Chem. 2003;105:559. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(03)00066-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tanford C. Protein Sci. 1997;6:1358. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steinberg IZ, Scheraga HA. J. Biol. Chem. 1963;238:172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Privalov PL, Gill SJ. Adv. Protein. Chem. 1988;39:191. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60377-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Babu CR, Hilser VJ, Wand AJ. Nature Struct.Mol. Biol. 2004;11:352. doi: 10.1038/nsmb739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hilser VJ, Garcia-Moreno EB, Oas TG, Kapp G, Whitten ST. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:1545. doi: 10.1021/cr040423+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van Horn WD, Simorellis AK, Flynn PF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:13553. doi: 10.1021/ja052805i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pometun MS, Peterson RW, Babu CR, Wand AJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:10652. doi: 10.1021/ja0628654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Davidovic M, Mattea C, Qvist J, Halle B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:1025. doi: 10.1021/ja8056419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.