Abstract

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), caused by mutations in the dystrophin gene, is a common and lethal form of muscular dystrophy. With progressive disease, most patients succumb to death from respiratory and/or heart failure. However, the mechanisms, especially those governing cardiac inflammation and fibrosis in DMD, remain less well understood. Matrix metalloproteinase (MMPs) are a group of extracellular matrix proteases involved in tissue remodelling in both physiological and pathophysiological conditions. Previous studies have shown that MMP-9 exacerbates myopathy in dystrophin-deficient mdx mice. However, the role and the mechanisms of action of MMP-9 in cardiac tissue and the biochemical mechanisms leading to increased levels of MMP-9 in mdx mice remain unknown. Our results demonstrate that the levels of MMP-9 are increased in heart of mdx mice. Genetic ablation of MMP-9 attenuated cardiac injury, left ventricle dilation, and fibrosis in one-year old mdx mice. Echocardiography measurements showed improved heart function in Mmp9-deficient mdx mice. Deletion of Mmp9 gene diminished the activation of extracellular-regulated kinase ½ and Akt kinase in heart of mdx mice. Ablation of MMP-9 also suppressed the expression of MMP-3 and MMP-12 in heart of mdx mice. Finally, our experiments have revealed that osteopontin, an important immunomodulator, contributes to the increased amounts of MMP-9 in cardiac and skeletal muscle of mdx mice. This study provides a novel mechanism for development of cardiac dysfunction and suggests that MMP-9 and OPN are important therapeutic targets to mitigating cardiac abnormalities in DMD patients.

INTRODUCTION

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a lethal inherited disease of skeletal muscle resulting from mutation in the dystrophin gene. A vast majority of DMD patients also develop cardiomyopathy and 10–15% of patients die due to cardiac failure (1). Furthermore, more than 90% of patients with the milder Becker muscular dystrophy and female DMD carriers show cardiac involvement (2–5). A murine model of DMD, the mdx mouse, also lacks dystrophin due to a nonsense point mutation in exon 23 of the dystrophin gene (6). Hearts of mdx mice share many features of the DMD cardiomyopathy (7–9). Similar to DMD patients, mdx mice experience a progressive development of cardiac defects, although the pathology is milder at the young age. However, by the age 42 weeks, mdx mice display several features of cardiomyopathy such as echocardiogram abnormalities, impaired conduction, arrhythmias, autonomic dysfunction, and reduced left ventricular function (8, 10, 11). In addition, mdx hearts experience progressive accumulation of connective tissues suggesting that fibrosis may also be responsible for some features of cardiomyopathy in these mice (9). However, the pathophysiological mechanisms leading to cardiac dysfunction and fibrosis in DMD remain poorly understood.

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are a family of zinc-containing, calcium-dependent proteases that play an important role in extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling, inflammation, fibrosis, and activation of various latent cytokines and cell adhesion molecules in both physiological and pathological conditions (12). MMPs are synthesized as secreted or transmembrane proenzymes and processed to an active enzyme by the removal of an amino-terminal propeptide (12, 13). The proteolytic activity of MMPs is tightly controlled by their interaction with endogenous tissue inhibitors of MMPs (TIMPs), which inhibit enzymatic activity of MMPs (12–14). There are four known TIMPs (i.e. TIMP1-4), each of which binds at different rate of interaction and affinity to a target MMP (13). The balance between MMPs and TIMPs plays an important role in preserving tissue integrity (12). Disruption of this balance has been found to cause tissue degradation in many diseased states such as chronic wounds, cardiomyopathy, rheumatic arthritis, fibrotic lung disease, asthma, gastric ulcer, central nervous system diseases, multiple sclerosis, and cancer (12, 15–19).

Recent reports suggest that the expression and activity of several MMPs are dysregulated in dystrophic muscle of mdx (a mouse model of DMD) mice (20–22). Our prior work has described that inhibition of MMP-9 (also known as gelatinase B) reduces several features of skeletal muscle pathology in mdx mice (23). Similar to MMP-9, the levels of MMP-2 (gelatinase A) have also been found to be significantly up-regulated in myofibers of mdx mice (23, 24). Miyazaki et al have recently reported that genetic deletion of MMP-2 inhibits fiber growth and angiogenesis in skeletal muscle of mdx mice suggesting that MMP-2 is a positive regulator of regenerating fibers growth in mdx mice (22). However, how the expression of various MMPs is affected in cardiac muscle of mdx mice remains unknown. Since loss of dystrophin influences skeletal muscle regeneration and cardiac function with only partially overlapping mechanisms (25), it is essential to investigate the role of various dysregulated MMPs in both cardiac and skeletal muscle in dystrophic models. Furthermore, the biochemical mechanisms leading to altered expression of various MMPs in models of DMD remain to be investigated.

Osteopontin (OPN), also known as early T-cell activation-1, was originally discovered as an inducible marker of transformation of epithelial cells. It is a secreted, integrin-binding matrix phosphorylated glycoprotein involved in a number of cell functions including cell adhesion and migration, inflammation, angiogenesis, tissue remodeling and tumor development (26). Published reports suggest that OPN can induce the expression of number of inflammatory molecules including MMP-9 in some cell types (27, 28). A recent study has demonstrated that protein levels of OPN are significantly increased in circulation and dystrophic muscle of mdx mice (29). More importantly, genetic ablation of OPN in mdx mice significantly attenuated fibrosis in skeletal and cardiac muscle of mdx mice (29). Interestingly, both OPN and MMP-9 have been found to be the major mediators of heart failure in several other conditions (30). We hypothesized that increased levels of OPN causes inducible expression of MMP-9 leading to cardiac fibrosis and dysfunction in mdx mice.

In this study, using genetic mouse models, we have investigated the role of MMP-9 in age-related cardiac dysfunction in mdx mice. Our experiments demonstrate that the levels of MMP-9 are increased in the heart of mdx mice. Genetic deletion of MMP-9 significantly reduced several features of cardiomyopathy including fibrosis and led to improvement in heart function in mdx mice. Our study also demonstrates that elevated levels of osteopontin, a recently identified mediator of fibrosis in mdx mice (29), contribute significantly to the increased expression of MMP-9 in both skeletal and cardiac muscle of mdx mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Mdx (strain: C57BL/10ScSn DMDmdx) and Mmp9-knockout (strain: FVB.Cg-Mmp9tm1Tvu) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Mmp9-knockout mice were first crossed with C57BL10/ScSn mice for seven generations and then with mdx mice to generate littermate wild-type (WT), mdx/Mmp9+/+ and mdx/Mmp9−/−. All genotypes were determined by PCR analysis from tail DNA as described (23). Mice were housed under conventional conditions with constant temperature and humidity and fed a standard diet. To study the effects of osteopontin (OPN) on expression of MMP-9, 3-week old WT mice were given a single retro-orbital injection of recombinant mouse OPN protein (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) at a dosage of 100 μg/kg body weight. Mice were euthanized after 12h. To investigate the role of OPN in expression of MMP-9, 3-week old mdx mice were treated with intraperitoneal injections of either 200 μg/mouse anti-OPN (R&D Systems) or 200 μg/ml isotype control (BioLegend, San Diego, CA) every third day for 10 days (total of three injections). After 24h of final injection, the mice were euthanized, and heart and skeletal muscle were isolated for biochemical analysis. All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of University of Louisville and conformed to the American Physiological Society’s Guiding Principles in the Care and Use of Animals.

Histological and Immunohistochemical Analyses

Cardiac tissues were removed, frozen in isopentane cooled in liquid nitrogen, and sectioned in a microtome cryostat. For the assessment of tissue morphology, 5 μm-thick transverse sections of each muscle were stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E), and staining was visualized on a microscope (Eclipse TE 2000-U), a digital camera (Digital Sight DS-Fi1), and NIS Elements BR 3.00 software (all from Nikon). The images were stored as JPEG files, and image levels were equally adjusted using Photoshop CS2 software (Adobe). The extent of fibrosis in transverse cryosections of heart was determined using Mason’s Trichrome staining kit following a protocol suggested by the manufacturer (Richard-Allan Scientific). Area under fibrosis or necrosis in cardiac section was quantified using MetaMorph Image analysis software (version 4.5). For detection of macrophages in heart cryosections, anti-F4/80 (dilution 1:100; clone CI:A3-1, AbD Serotec) was used in conjunction with the VECSTAIN ABC staining kit (Vector) with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) substrate according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Number of F4/80-positive cells was measured using a method as previously described (23). Necrotic/injured area in transverse cryosections of heart was identified by immunostaining with Cy3-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (1:3000, Invitrogen) as described (23).

Gelatin Zymography

To determine MMP-9 activity, we performed zymography using a similar protocol as described previously (23). Briefly, cardiac (left ventricle) muscle extracts were prepared in non-reducing lysis buffer [50 mm Tris-Cl (pH 8.0), 200 mm NaCl, 50 mm NaF, 0.3% IGPAL CA-630 and protease inhibitor cocktail]. Equal amount of protein (80 μg/sample) was separated on 8% SDS–PAGE containing 1 mg/ml gelatin B (Fisher Scientific) under non-reducing conditions. Gels were washed in 2.5% Triton X-100 for 1 h at room temperature followed by incubation in reaction buffer [50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mm NaCl, 5 mm CaCl2 and 0.02% sodium azide] for 48 h at 37°C. To visualize gelatinolytic bands, gels were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue dye at room temperature followed by extensive washing in destaining buffer (10% methanol and 10% acetic acid in distilled water). The gels were photographed for determination of gelatinolytic activity.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR (QRT-PCR)

QRT-PCR for individual genes was performed using an ABI Prism 7300 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems) using a method as previously described (31). Briefly, the first-strand cDNA reaction (0.5 μl) was subjected to real-time PCR amplification using gene-specific primers. The primers were designed according to ABI primer express instructions using Vector NTI software and were purchased from Sigma-Genosys (Spring, TX). The sequences of the primers used are as follows: MMP-2: 5′-ACA GCC AGA GAC CTC AGG GT-3′ (forward) and 5′-CAG CAC AGG ACG CAG AGA AC-3′ (reverse); MMP-3: 5′-GTG TGT GGT TGT GTG CTC ATC CTA -3′ (forward) and 5′-CCC GAG GAA CTT CTG CAT TTC T-3′ (reverse); MMP-10: 5′-GCA TTC AAT CCC TGT ATG GAG C-3′ (forward) and 5′-TTC AGG CTC GGG ATT CCA AT-3′ (reverse); MMP-14: 5′-ATT TGC TGA GGG TTT CCA CG-3′ (forward) and 5′-TCG GCA GAA TCA AAG TGG GT-3′ (reverse); Col1a1: 5′-TCA AGA TGG TCG CCC TGG AC-3′ (forward) and 5′-CCT TTC CAG GTT CTC CAG CG-3 (reverse); Col3a1: 5′-GTG AAC GTG GCT CTA ATG GCA T-3′ (forward) and 5′-AAT AGG ACC TGG ATG CCC ACT T-3′ (reverse); TIMP-1, 5′-TTG CAT CTC TGG CAT CTG GCA T-3′ (forward) and 5′-GAT ATC TGC GGC ATT TCC CAC A-3′ (reverse); TIMP-2: 5′-GTG ACT TCA TTG TGC CCT GGG-3′ (forward) and 5′-TGG GAC AGC GAG TGA TCT TGC-3′ (reverse); TIMP-3: 5′-CAG ATG AAG ATG TAC CGA GGC TTC-3′ (forward) and 5′-AAC CCA GGT GGT AGC GGT AAT T-3′ (reverse); CD68: 5′-TTA CTC TCC TGC CAT CCT TCA CGA-3′ (forward), and 5′-CCA TTT GTG GTG GGA GAA ACT GTG-3′ (reverse); IL-1β: 5′-CTC CAT GAG CTT TGT ACA AGG-3′ (forward) and 5′-TGC TGA TGT ACC AGT TGG GG-3′ (reverse); TNF-α, 5′-GCA TGA TCC GCG ACG TGG AA-3′ (forward) and 5′-AGA TCC ATG CCG TTG GCC AG-3′ (reverse); β-actin, 5′-CAG GCA TTG CTG ACA GGA TG-3′ (forward) and 5′-TGC TGA TCC ACA TCT GCT GG-3′ (reverse).

Real-time PCR assays were performed in approximately 25-μl reactions, consisting of 2X (12.5 μl) Brilliant SYBR Green QPCR Master Mix (Stratagene), 400 nmol/L primers (0.5 μl each from the stock), 11 μl of water, and 0.5 μl of template. The thermal conditions consisted of an initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 minutes followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 seconds, annealing and extension at 60°C for 1 minute, and, for a final step, a melting curve of 95°C for 15 seconds, 60°C for 15 seconds, and 95°C for 15 seconds. All reactions were performed in triplicate to reduce variation. The data were analyzed using SDS software version 2.0, and the results were exported to Microsoft Excel for further analysis. Data normalization was accomplished using β-actin as endogenous control and the normalized values were subjected to a 2−ΔΔCt formula to calculate the fold change between the control and experimental groups. The formula and its derivations were obtained from the ABI Prism 7900 sequence detection system user guide.

Western Blot

Hearts were isolated from mice, washed extensively with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and left ventricle (LV) muscle was homogenized in lysis buffer A [50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0), 200 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM dithiotheritol, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 0.3% IGEPAL, and protease inhibitor cocktail]. Approximately, 100 μg protein was resolved on each lane on 8–12% SDS-PAGE, electrotransferred onto nitrocellulose membrane and probed using anti-MMP-9 (0.1 μg/ml; catalog # AF909; R&D Systems), anti-phospho p44/p42 (dilution 1:1000; catalog # 9101; Cell Signaling, Inc), anti-p44/p42 (dilution 1:1000, catalog # 9102, Cell Signaling, Inc), anti-phospho-JNK1/2 (dilution 1:1000, catalog # 9251; Cell signaling, Inc), anti- JNK1/2 (0.2 μg/ml; catalog # sc-474; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-phospho p38 (dilution 1:1000; catalog # 9216; Cell Signaling, Inc), anti-p38 (dilution 1:1000; catalog # 9212; Cell Signaling, Inc.), anti-phospho Akt (dilution 1:1000; catalog # 9271; Cell Signaling, Inc), anti-Akt (dilution 1:1000; catalog # 9272; Cell Signaling, Inc), and anti-tubulin (dilution 1:3000; catalog # 2144; Cell Signaling, Inc.) and detected by chemiluminescence. Gel Images were quantified using ImageJ software from National Institute of Health.

Echocardiography

Transthoracic echocardiography was performed on mice as previously described (32, 33). Briefly, a Hewlett-Packard Sonos 7770 echocardiographic system equipped with a 15-MHz shallow-focus 15-6L phased-array transducer was used for measurements of LV function. The mice were sedated with 2,2,2 tribromoethanol (TBE, Sigma T48 402; 240 mg/kg of body weight) and the chest was shaved. The transducer probe was placed on the left hemithorax of the mice in the partial left decubitus position. Two-dimensionally targeted M-mode echocardiograms were obtained from a short-axis view of the LV at or just below the tip of the mitral-valve leaflet. LV size and the thickness of LV wall were measured. Only M-mode echocardiography with well-defined continuous interfaces of the septum and posterior wall were collected. For quantification of left ventricular (LV) dimensions and wall thickness, LV short- and long-axis loops and LV 2-D echocardiography image-guided M-mode traces at the level that yielded the largest diastolic dimension were digitally recorded. LV dimensions at diastole and systole (LVDd and LVDs, respectively) were measured and averaged. Fractional shortening (FS) was calculated as [(LVDd−LVDs)/LVDd] × 100%.

Statistical Analyses

Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis used Student’s t-test or ANOVA to compare quantitative data populations with normal distribution and equal variance. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant unless otherwise specified.

RESULTS

MMP-9 levels are increased in hearts of 12-month old mdx mice

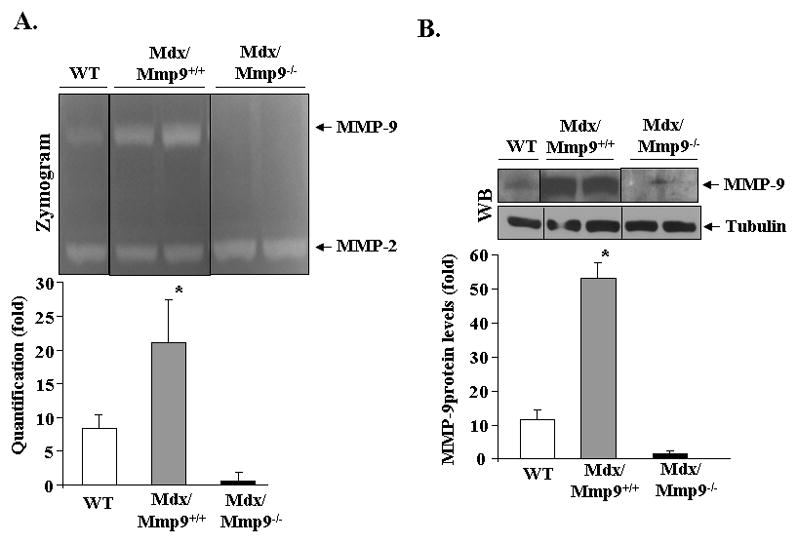

Since mdx mice develop significant cardiomyopathy by the age of 1 year (8), we first measured the levels of MMP-2 and MMP-9 protein in left ventricle (LV) muscle of 1-year old mdx mice using gelatin zymography and Western blot techniques. As shown in Figure 1A, the levels of MMP-9 were dramatically increased in LV of mdx mice compared to WT mice. On the contrary, there was no significant difference in the levels of MMP-2 between WT and mdx mice (Figure 1A). Since we were interested in investigating the role of MMP-9 in cardiac pathology in mdx mice, in the same experiment, we also evaluated the levels of MMP-9 protein in LV of mdx/Mmp9−/− mice. As depicted in Figure 1A, MMP-9 was undetectable in mdx/Mmp9−/− mice confirming ablation of MMP-9 in these mice. Deletion of Mmp9 gene did not have any major affect on MMP-2 activity in hearts of mdx/Mmp9−/− mice (Figure 1A). Western blotting of protein extracts further confirmed increased levels of MMP-9 in heart of mdx/Mmp9+/+ mice compared to WT mice and MMP-9 was undetectable in mdx/Mmp9−/− mice (Figure 1B).

FIGURE 1. Expression of MMP-9 in left ventricle (LV) of mdx mice.

LV muscle from 12-month old wild-type, mdx/Mmp9+/+, and mdx/Mmp9−/− mice was isolated and processed to study the level of MMP-9 protein. A) Gelatin zymography gel and quantification of MMP-9 bands in zymograms, and B) Western blot along with densitometric quantification presented here demonstrate that the levels of MMP-9 protein are increased in LV of mdx mice. MMP-9 protein was undetectable in heart of mdx/Mmp9−/− mice and the levels of an unrelated protein tubulin remained comparable between WT, mdx/Mmp9+/+, and mdx/Mmp9−/− mice. Black line indicates that intervening lanes have been spliced out. N=3 in each group. *p<0.01, values significantly different from WT mice.

Genetic ablation of MMP-9 reduces cardiac injury in mdx mice

To understand the role of MMP-9 in cardiac abnormalities, we first performed Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining on transverse cryosections of cardiac tissues isolated from one-year old littermate WT, mdx/Mmp9+/+, and mdx/Mmp9−/− mice. Examination of H&E-stained sections revealed presence of patches of necrotic area containing cellular infiltrates in left ventricle muscle of mdx/Mmp9+/+ mice (Figure 2A). In contrast, hearts of mdx/Mmp9−/− mice showed significantly reduced necrotic area and cellular infiltrate in LV (Figure 2A and Figure 2B). Cardiomyocyte injury can be assessed by the leakage of intracellular contents into the serum and the influx of serum components into the cytoplasm of cells through leaky/damaged membrane (34). To evaluate membrane damage, we analyzed the leakage of IgG from serum into the cytoplasm of cardiomyocytes in LV sections of WT, mdx/Mmp9+/+, and mdx/Mmp9−/− mice. Staining with Cy3-labelled goat anti-mouse IgG showed areas containing cardiomyocytes stained positive in mdx/Mmp9+/+ mice but not in wild-type mice (Figure 2C). Heart sections from mdx/Mmp9−/− mice showed considerably reduced area that stained positive for IgG suggesting that the inhibition of MMP-9 reduces cardiomyocyte membrane damage in mdx mice (Figure 2C).

FIGURE 2. Ablation of MMP-9 reduces cardiac injury in mdx mice.

A). Frozen cross-sections made from heart (at the center of ventricles) of 1 year old wild-type (WT), mdx/Mmp9+/+ and mdx/Mmp9−/− mice were stained with H&E and photomicrograph. Data presented here demonstrate that the deletion of Mmp9 gene in mdx mice improves cardiac structure. Arrows point to damaged/necrotic area. Scale bar: 50 μm. B). Quantification of necrotic area in H&E-stained images. *p<0.01, values significantly different from WT mice. #p<0.01, values significantly different from mdx/Mmp9+/+ mice. C). Representative photomicrographs of cardiac sections stained with Cy3-labelled goat anti-mouse IgG demonstrating that cardiac injury is considerably reduced in mdx/Mmp9−/− mice compared with mdx/Mmp9+/+ mice. Scale bar: 50 μm. N=6 in each group.

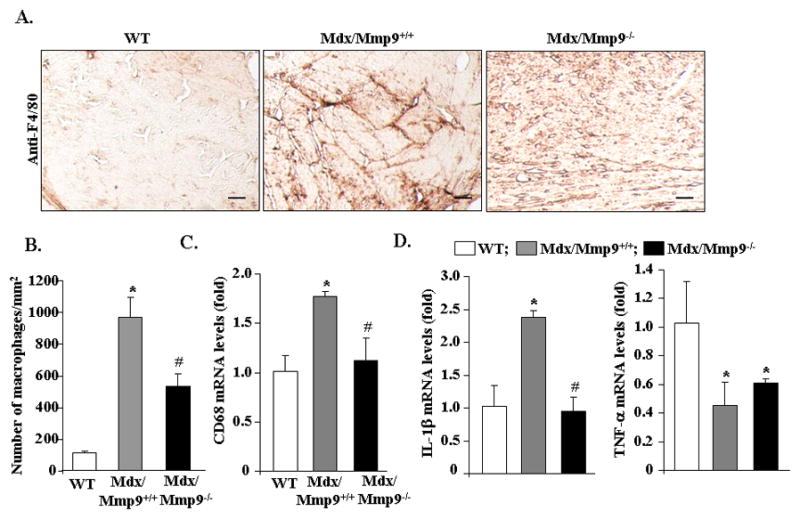

Ablation of MMP-9 inhibits accretion of macrophages and expression of inflammatory cytokines in cardiac muscle of mdx mice

Accumulating evidence indicates that inflammation contributes significantly to the striated muscle pathogenesis in both DMD patient and mdx mice (35). Since MMP-9 is a major mediator of ECM breakdown and inflammatory response (12), we investigated whether the inhibition of MMP-9 affects the infiltration of macrophages and the expression of proinflammatory cytokines in cardiac muscle of mdx mice. Immunostaining of cardiac section with anti-F4/80 (a marker for macrophages) showed that the concentration of macrophages was considerably higher in mdx/Mmp9+/+ mice compared to wild-type mice (Figure 3A, 3B). However, the number of macrophages was considerably reduced in cardiac muscle of mdx/Mmp9−/− mice compared to mdx/Mmp9+/+ mice (Figure 3A, 3B). Furthermore, mRNA level of CD68, a cell surface marker for macrophages, was significantly lower in left ventricle wall of mdx/Mmp9−/− mice compared to mdx/Mmp9+/+ mice (Figure 3C) further suggesting that the inhibition of MMP-9 reduces the accretion of macrophages in heart of mdx mice.

FIGURE 3. Role of MMP-9 in accumulation of macrophages and expression of inflammatory cytokines in heart of mdx mice.

A). Frozen heart sections prepared from 1-year old wild-type (WT), mdx/Mmp9+/+, and mdx/Mmp9−/− mice were immunostained with anti-F4/80 using a method as described in “Materials and Methods”. Representative photomicrographs presented here demonstrate that inhibition of MMP-9 reduces the concentration of macrophages in cardiac muscle of mdx mice. Scale bar: 50 μm. B). Quantification of number of F4/80-positive cells in heart sections. C). The mRNA levels of CD68 in heart of WT, mdx/Mmp9+/+, and mdx/Mmp9−/− mice measured by QRT-PCR assay. D). Fold changes in mRNA levels of TNF-α and IL-1β in heart of WT, mdx/Mmp9+/+, and mdx/Mmp9−/− mice. N=6 in each group. *p<0.01, values significantly different from WT mice. #p<0.01, values significantly different from mdx/Mmp9+/+ mice.

Increased amounts of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β have been previously reported in dystrophic muscle of mdx mice (36). We next investigated whether MMP-9 affects the expression of TNF-α and IL-1β in cardiac muscle of mdx mice. As shown in Figure 3D, mRNA levels of IL-1β were significantly higher in heart of mdx/Mmp9+/+ mice compared to wild-type littermates. However, the mRNA levels of IL-1β were found to be significantly reduced in cardiac muscle of mdx/Mmp9−/− compared to mdx/Mmp9+/+ mice (Figure 3D). Interestingly, we noticed that the mRNA levels of TNF-α were significantly reduced in heart of mdx/Mmp9+/+ mice compared to wild-type mice and there was no significant difference between mdx/Mmp9+/+ and mdx/Mmp9−/− mice at the age of 12 months (Figure 3D). These results suggest that the expression of IL-1β and TNF-α is differentially affected in heart of mdx mice and MMP-9 causes increased expression of only IL-1β.

Genetic deletion of MMP-9 attenuates age-related collagen deposition in heart of mdx mice

Cardiac fibrosis, defined as the excessive accumulation of extracellular matrix (ECM) such as collagens, is a major pathological feature of DMD patients causing systolic and diastolic dysfunctions and conduction defects in the heart (37). Since MMP-9 has been found to exacerbate fibrosis in many disease states (12, 38–40), we next examined whether the inhibition of MMP-9 can reduce cardiac fibrosis in mdx mice. Staining of cardiac muscle sections with Masson’s Trichrome staining showed that the level of collagens (blue coloured) was significantly reduced in 1-year old mdx/Mmp9−/− compared with littermate mdx/Mmp9+/+ mice (Figure 4A). Reduced fibrosis in heart of mdx/Mmp9−/− mice was also confirmed by quantification of area stained positive for collagens in multiple sections (Figure 4B). We also measured mRNA levels of collagen I and III by QRT-PCR technique. As shown in Figure 4C, transcript levels of collagen III (i.e. Col3a1) were significantly reduced in the cardiac muscle of mdx/Mmp9−/− mice compared to mdx/Mmp9+/+ mice. The mRNA levels of collagen I (i.e. Col1a1) were also reduced in mdx/Mmp9−/− but they were not statistically different from mdx/Mmp9+/+ mice (Figure 4C). These results indicate that MMP-9 mediates the fibrotic response in heart of mdx mice.

FIGURE 4. Deletion of Mmp9 gene diminishes fibrosis in cardiac muscle of mdx mice.

A). Hearts isolated from 1-year old wild-type (WT), mdx/Mmp9+/+ and mdx/Mmp9−/− mice were sectioned transversely at 5 μm thickness and Masson’s Trichrome staining was performed. Representative photomicrographs presented here demonstrate that the levels of collagen (blue colored) is considerably reduced in mdx/Mmp9−/− mice compared to littermate mdx/Mmp9+/+. B). Quantification of area under fibrosis in heart sections of WT, mdx/Mmp9+/+, and mdx/Mmp9−/− mice. N=6 in each group. C). Left ventricle muscle from 1-year old WT, mdx/Mmp9+/+ and mdx/Mmp9−/− were analyzed for the expression of Col1a1 and Col3a1 by QRT-PCR. *p<0.01, values significantly different from mdx/Mmp9+/+ mice.

Ablation of MMP-9 improves left ventricular function in 12-month old mdx mice

Because inhibition of MMP-9 reduced cardiac injury and fibrosis, we next sought to determine whether deletion of MMP-9 can also improve heart function in mdx mice. Left ventricular (LV) function was assessed by echocardiography in littermate wild-type, mdx/Mmp9+/+, and mdx/Mmp9−/− mice at the age of 12 months. Cardiac parameters were normal in wild-type mice (Figure 5). However, in mdx mice, an increase in left ventricle internal diameter during diastole (LVIDd) and left ventricular posterior wall thickness during diastole (LVPWd) with concomitant decrease in fractional shortening (FS), the typical features of age-related cardiomyopathy in mdx mouse model (8), were noticeable (Figure 5B, 5C, and 5D). Interestingly, LVIDd and LVPWd were found to be significantly reduced in mdx/Mmp9−/− mice (Figure 5B and 5C). Furthermore, ablation of MMP-9 significantly improved FS in mdx mice (Figure 5D). Collectively, these results suggest that MMP-9 is involved in cardiac dysfunction in mdx mice.

FIGURE 5. Effects of ablation of MMP-9 on cardiac function in mdx mice.

(A). M- mode echocardiograms of 1-year old wild-type, mdx/Mmp9+/+ and Mdx/Mmp9−/− mice obtained with two-dimensional echocardiography from short-axis midventricle view of hearts. Arrows represent LVPWd. Fold change in B). LVIDd, and C). LVPWd values between WT, mdx/Mmp9+/+ and Mdx/Mmp9−/− mice. D) Fractional shortening (FS) gave higher values for mdx/Mmp9−/− mice compared to littermate mdx/Mmp9+/+ providing an evidence of improvement in heart function after inhibition of MMP-9 in mdx mice. N=6 in each group. *p<0.01, values significantly different from WT mice. #p<0.01, values significantly different from mdx/Mmp9+/+ mice.

Effect of deletion of MMP-9 on the expression of other MMPs and TIMPs in hearts of mdx mice

Accumulating evidence suggests that there is a cooperative interaction between various MMPs to promote effective tissue degradation in various conditions including muscular dystrophy (12, 41). On the other hand, the activity of MMPs can be affected by the levels of TIMPs, which directly bind and inhibit MMPs (12). We investigated whether the ablation of MMP-9 affects the expression levels of other MMPs and/or TIMPs in left ventricle muscle of mdx mice. QRT-PCR analysis showed that the mRNA levels of MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-10, MMP-12, TIMP-2, and TIMP-3 were significantly higher in heart of mdx/Mmp9+/+ mice compared to wild-type littermates (Figure 6). Interestingly, the mRNA levels of MMP-3 and MMP-12 (but not MMP-2, MMP-10, TIMP-2, or TIMP-3) were found to be significantly reduced in heart of mdx/Mmp9−/− mice compared to mdx/Mmp9+/+ mice (Figure 6). In contrast, there was no significant difference in mRNA levels of MMP-14 or TIMP-1 between wild-type, mdx/Mmp9+/+, and mdx/Mmp9−/− mice (data not shown). These results suggest that in addition to MMP-9, the expression of several other MMPs is dysregulated in heart of mdx and MMP-9 contributes to the increased expression of at least MMP-3 and MMP-12.

FIGURE 6. Role of MMP-9 on the expression of various MMPs and TIMPs in heart of one-year old mdx mice.

Total mRNA was isolated from heart of one year old WT, mdx/Mmp9+/+, and mdx/Mmp9−/− mice and the mRNA levels of various MMPs and TIMPs were measured by QRT-PCR. N=4 in each group. *p<0.01, values significantly different from wild-type mice. #p<0.01, values significantly different from mdx/Mmp9+/+ mice.

Ablation of MMP-9 reduces the phosphorylation of extracellular-signal regulated kinase ½ (ERK1/2) and Akt in hearts of mdx mice

Published reports suggest that loss of dystrophin leads to several signaling defects in skeletal and cardiac muscle of mdx mice (42). We investigated whether MMP-9 affects the activation of specific mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) and Akt kinase in cardiac muscle of mdx mice. Protein extracts prepared from left ventricle of 1-year old littermate WT, mdx/Mmp9+/+, and mdx/Mmp9−/− mice were immunoblotted using antibody that detects phosphorylated or total forms of various MAPKs or Akt. As shown in Figure 7A, the phosphorylation (but not total protein levels) of ERK1/2 and Akt kinase were found to be considerably increased in LV of mdx/Mmp9+/+ mice compared to wild-type. Interestingly, ablation of MMP-9 significantly reduced phosphorylation of both ERK1/2 and Akt in hearts of mdx mice (Figures 7A and 7B). In contrast, there was no significant difference in the total or phosphorylated forms of c-Jun N-terminal kinase ½ (JNK1/2) and p38 MAPK between WT, mdx/Mmp9+/+ and mdx/Mmp9−/− mice (Figure 7A).

FIGURE 7. Effect of ablation of MMP-9 on the activation of MAPKs and Akt in heart of 1-year old mdx mice.

A) Protein extracts prepared from heart of 1-year old WT, mdx/Mmp9+/+, and mdx/Mmp9−/− mice, were immunoblotted using antibody against phosphorylated or total ERK1/2, JNK1/2, p38MAPK, and Akt protein. Representative immunoblots presented here demonstrate that the level of phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and Akt was reduced in LV of mdx/mmp9−/− mice compared to mdx/Mmp9+/+ mice. B). Densitometric quantification of immunoblots. N=4 in each group. *p<0.05, values significantly different from mdx/Mmp9+/+ mice. #p<0.05, values significantly different from mdx/Mmp9+/+ mice.

Osteopontin (OPN) augments the levels of MMP-9 in cardiac and skeletal muscle of mdx mice

Since OPN levels are increased in serum of mdx mice (29) and OPN is known to stimulate the expression of MMP-9 (27, 28), we next sought to determine whether OPN contributes to the increased levels of MMP-9 in skeletal and cardiac muscle of mdx mice. For this, we performed two sets of experiments. In the first set, 3-week old wild-type mice were given retro-orbital injection of recombinant OPN protein or saline alone. After 12h, skeletal and cardiac muscles were isolated and used to measure the levels of MMP-9 protein. Interestingly, treatment with OPN considerably increased the protein levels of MMP-9 in both heart (Figure 8A) and TA muscle (Figure 8B). In the second set of experiments, mdx (4-week old) mice were given chronic intraperitoneal injection of OPN-neutralizing antibody for 10 days. The mice were then sacrificed and amounts of MMP-9 protein in cardiac and skeletal muscle were determined by Western blot. Interestingly, treatment with OPN-neutralizing antibody significantly reduced the levels of MMP-9 in both TA (Figure 8C) and cardiac (Figure 8D) muscle of mdx mice. Taken together, these results suggest that the increased levels of OPN contribute to the expression of MMP-9 in striated muscle of mdx mice.

FIGURE 8. Involvement of OPN in expression of MMP-9 in heart and skeletal muscle of mdx mice.

3-week old wild-type mice were given a single retro-orbital injection of OPN protein (100 μg/kg body weight). After 12h, the levels of MMP-9 protein in left ventricle (LV) and tibial anterior (TA) muscle were measured by Western blot. Representative immunoblots and quantification of bands (bar diagrams) presented here demonstrate that OPN increases the levels of MMP-9 protein in (A) Heart and (B) TA muscle of mice. *p<0.05, values significantly different from mice treated with PBS alone. 3–4 week old mdx mice were given three intraperitoneal injections of anti-OPN or isotype control every 3rd day for a total of 10 days. LV and TA muscle isolated were used to measure the level of MMP-9 protein by Western blot. Data presented here demonstrate that treatment with OPN-neutralizing antibody significantly reduces the levels of MMP-9 protein in both (C) Heart and (D) TA muscle. N=3 in each group. #p<0.05, values significantly different from mdx mice treated with isotype control.

Discussion

Cardiomyopathy, a major pathological feature in DMD, refers to a condition in which the heart is abnormally enlarged and/or dilated, thickened and/or stiffened (43, 44). As a result, the heart’s ability to pump blood is weakened. It is now increasing clear that cytoskeletal defects produce cardiomyopathy through the combination of both structural and biochemical mechanisms (43, 45, 46). In DMD patients, loss of functional dystrophin protein results in several pathological changes including myocyte necrosis, inflammation, fibrosis, tachycardia, and impaired contractile properties leading to heart failure and mortality (2–5). However, the biochemical mechanisms leading to cardiomyopathy in DMD remains poorly understood.

MMPs play a critical role in extracellular matrix turnover in both physiological and pathological remodeling. (12, 41, 47). MMP-9 is one of the major MMPs expressed in the heart of both humans and animal models. Increased myocardial expression and activity of MMP-9 have been observed in a variety of experimental myocardial injuries such as the permanent coronary artery occlusion model in rodents (48, 49) and the reperfusion injury model in porcine (50, 51). Elevated levels of MMP-9 have also been observed in failing human heart suggesting a possible role of MMP-9 in cardiomyopathy (52, 53). Moreover, targeted deletion of MMP-9 in mice has been found to attenuate coronary artery ligation-induced left ventricle enlargement and accumulation of collagens further implicating a role for MMP-9 in cardiac remodeling after ischemic injury(54). Our present study provides experimental evidence that the levels of MMP-9 are also elevated in the mdx model of DMD and that MMP-9 contributes to cardiac abnormalities in mdx mice.

Inflammatory response that includes accretion of immune cells such as macrophages and neutrophils, contributes significantly to the disease progression in DMD patients (46, 55–57). While the major function of these cells is to remove the damaged tissue through phagocytosis, persistent activation of these phagocytes also causes striated muscle necrosis in DMD models (58, 59). These cells are also the major source of a variety of inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, cell adhesion molecules, and matrix degrading enzymes, the increased expression of which lead to cardiac dysfunction. Indeed, depletion of inflammatory immune cells has been found to ameliorate the pathogenesis in models of DMD (59–62). The role of inflammation in DMD pathology is also evident by the findings that prednisone, which has therapeutic value in DMD, functions by reducing inflammation (35). Importantly, MMP-9 is one of the major mediators of inflammatory response, degradation of extracellular matrix, and fibrosis (12, 15–19). Furthermore, MMP-9 is also known to cause proteolytic processing of a number of inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and cell adhesion molecules (12). More recently, it was reported that MMP-9 can directly cleave OPN in biologically active fragments (63). Among others, transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) is one of the most important molecules, which gets activated by MMP-9 (64). Elevated levels of TGF-β have been observed in circulation of DMD patients and animal models, which positively correlate with interstitial fibrosis in skeletal and cardiac muscle (12, 64). Indeed, we have previously reported that the inhibition of MMP-9 reduces the levels of active TGF-β in dystrophic muscle of mdx mice (23). Therefore, one of the potential mechanisms by which elevated levels of MMP-9 cause cardiac fibrosis in mdx mice could be through proteolytic activation of TGF-β. Moreover, our results demonstrating that the ablation of MMP-9 reduces the accretion of macrophages and expression of inflammatory cytokines (Figure 3) are consistent with other published reports suggesting an important role of MMP-9 in regulation of these responses in other pathological conditions (12, 15–19).

Accumulating evidence suggests that there is a cooperative interaction between various MMPs and many tissue degenerative conditions involve the increased expression and activation of multiple MMPs (23). The members of the MMPs family often activate each other, for example, membrane type 1 MMP (MT1-MMP) activates MMP-2 or MMP-13 and MMP-3 activates MMP-9 (12, 13, 65). In contrast, the activity of MMPs can be inhibited by increased expression of various TIMPs. We have found that the transcript levels of several other MMPs and TIMPs are also significantly up-regulated in the heart of mdx mice (Figure 6). Moreover, we noticed that the ablation of MMP-9 significantly reduced the mRNA levels of MMP-3 and MMP-12 in heart of mdx mice (Figure 6). Interestingly, increased expression of MMP-3 has been suggested as an independent predictor of cardiac failure and death in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy (66). Similarly, MMP-12 is a positive regulator of vascular smooth cells proliferation and atherosclerotic plaque development (67–69). These findings indicate that MMP-9 might also be exacerbating cardiomyopathy in mdx mice through augmenting the expression/activation of other MMPs.

In addition to mechanical instability, loss of dystrophin protein leads to the aberrant activation of a number of cell signaling pathways in skeletal and cardiac muscle (42). Previously studies including from us have reported the increased activation of many signaling proteins (e.g. ERK1/2, JNK1, p38MAPK, and Akt kinase) and transcription factors (e.g. NF-κB and AP-1) in skeletal and/or cardiac muscle of dystrophic mice (36, 42, 70–75). More recent studies have shown that proper regulation of some of these signaling pathways has enormous potential to attenuate disease progression in DMD (42, 76). Furthermore, it is also now evident that different signaling proteins are activated at different stages of disease progression in cardiac and skeletal muscle of mdx and other models of muscular dystrophy (reviewed in (42)). Our experiments have shown that MMP-9 causes the activation of ERK1/2 and Akt in heart of 1-year old mdx mice (Figure 7). Although the physiological significance of activation of ERK1/2 and Akt kinase remain unknown, previous studies have shown that increased activation of these signaling proteins can cause muscle hypertrophy (77). It is thus possible that MMP-9 causes cardiac hypertrophy in mdx mice through the activation of these signaling proteins. Our results are also in agreement with a previously published report demonstrating that genetic ablation of MMP-9 prevents cardiac hypertrophy in a model of heart failure (54). Intriguingly, ERK1/2 and Akt kinase are also involved in inducible expression of MMP-9 in response to specific stimuli (78, 79) suggesting that there may be a positive feed-back loop in which ERK1/2 and Akt promote MMP-9 expression and vice-versa in heart of mdx mice. However, it is also possible that the reduced activation of ERK1/2 and Akt is a result of reduced cardiomyopathy in Mmp9-deficient mdx mice.

While the role of MMP-9 in dystrophinopathy is increasingly clear, the mechanisms leading to the increased levels of MMP-9 remain less-well understood. It was recently reported that muscle biopsies of DMD patients and dystrophic muscle of mdx mice have elevated levels of OPN (29). Since the deletion of either OPN (29) or MMP-9 (Figure 4) considerably reduced fibrosis in cardiac muscle, we tested the hypothesis that OPN might be one of the potential stimuli to augment the expression of MMP-9 in cardiac and skeletal muscle of mdx mice. Our experiments demonstrating that the administration of OPN enhance the expression of MMP-9 in normal mice (Figure 8A, 8B) and anti-OPN reduces the levels of MMP-9 in mdx mice (Figure 8C, 8D) suggesting a potential link between these two molecules in pathogenesis of mdx mice. It is also noteworthy that while the inhibition of MMP-9 has been found to reduce the severity of disease progression in animal models of many tissue degenerative disorders, there is still no clinically approved drug that specifically blocks the activity of MMP-9. Broad spectrum MMP inhibitory drugs developed earlier failed in various clinical trials due to a musculoskeletal syndrome (41). Whereas more specific inhibitors of MMPs are under development in various pharmaceutical companies for clinical use, a potential alternative approach to inhibiting MMP-9 activity could be via targeting the molecules, such as OPN, which induces the expression of MMP-9 in particular disease states.

In summary, the present study demonstrating the efficacy of MMP-9 inhibition to improve cardiomyopathy in mdx mice suggests that MMP-9 can serve as an important molecular target for treatment of cardiomyopathy in DMD patients. Certainly, more investigations are required to evaluate the effects of inhibition of MMP-9 by multiple approaches and in higher model organisms before considering MMP-9 as a therapeutic target for DMD patients.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funding from the Muscular Dystrophy Association (to A.K.) and National Institutes of Health Grants AG029623 (to A.K.), AR059810 (to A.K.), and HL088012 (to S.C.T.).

ABBREVIATIONS

- DMD

Duchenne muscular dystrophy

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- ERK1/2

extracellular signal-regulated kinase ½

- H&E

Hematoxylin and Eosin

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- LV

left ventricle

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinases

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- OPN

osteopontin

- QRT-PCR

quantitative real-time PCR

- TA

tibial anterior

- TIMP

tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinases

- WT

wild-type

References

- 1.Cox GF, Kunkel LM. Dystrophies and heart disease. Curr Opin Cardiol. 1997;12:329–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frankel KA, Rosser RJ. The pathology of the heart in progressive muscular dystrophy: epimyocardial fibrosis. Hum Pathol. 1976;7:375–386. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(76)80053-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nigro G, Comi LI, Politano L, Bain RJ. The incidence and evolution of cardiomyopathy in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Int J Cardiol. 1990;26:271–277. doi: 10.1016/0167-5273(90)90082-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Melacini P, Fanin M, Duggan DJ, Freda MP, Berardinelli A, Danieli GA, Barchitta A, Hoffman EP, Dalla Volta S, Angelini C. Heart involvement in muscular dystrophies due to sarcoglycan gene mutations. Muscle Nerve. 1999;22:473–479. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(199904)22:4<473::aid-mus8>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Melacini P, Gambino A, Caforio A, Barchitta A, Valente ML, Angelini A, Fanin M, Thiene G, Angelini C, Casarotto D, Danieli GA, Dalla-Volta S. Heart transplantation in patients with inherited myopathies associated with end-stage cardiomyopathy: molecular and biochemical defects on cardiac and skeletal muscle. Transplant Proc. 2001;33:1596–1599. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(00)02607-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sicinski P, Geng Y, Ryder-Cook AS, Barnard EA, Darlison MG, Barnard PJ. The molecular basis of muscular dystrophy in the mdx mouse: a point mutation. Science. 1989;244:1578–1580. doi: 10.1126/science.2662404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emery AE. The muscular dystrophies. Lancet. 2002;359:687–695. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07815-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quinlan JG, Hahn HS, Wong BL, Lorenz JN, Wenisch AS, Levin LS. Evolution of the mdx mouse cardiomyopathy: physiological and morphological findings. Neuromuscul Disord. 2004;14:491–496. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wehling-Henricks M, Jordan MC, Roos KP, Deng B, Tidball JG. Cardiomyopathy in dystrophin-deficient hearts is prevented by expression of a neuronal nitric oxide synthase transgene in the myocardium. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:1921–1933. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bia BL, Cassidy PJ, Young ME, Rafael JA, Leighton B, Davies KE, Radda GK, Clarke K. Decreased myocardial nNOS, increased iNOS and abnormal ECGs in mouse models of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1999;31:1857–1862. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1999.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilding JR, Schneider JE, Sang AE, Davies KE, Neubauer S, Clarke K. Dystrophin- and MLP-deficient mouse hearts: marked differences in morphology and function, but similar accumulation of cytoskeletal proteins. FASEB J. 2005;19:79–81. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1731fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Page-McCaw A, Ewald AJ, Werb Z. Matrix metalloproteinases and the regulation of tissue remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:221–233. doi: 10.1038/nrm2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vu TH, Werb Z. Matrix metalloproteinases: effectors of development and normal physiology. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2123–2133. doi: 10.1101/gad.815400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mott JD, Werb Z. Regulation of matrix biology by matrix metalloproteinases. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2004;16:558–564. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chandler S, Miller KM, Clements JM, Lury J, Corkill D, Anthony DC, Adams SE, Gearing AJ. Matrix metalloproteinases, tumor necrosis factor and multiple sclerosis: an overview. J Neuroimmunol. 1997;72:155–161. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(96)00179-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu J, Van den Steen PE, Sang QX, Opdenakker G. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors as therapy for inflammatory and vascular diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:480–498. doi: 10.1038/nrd2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waubant E, Goodkin DE, Gee L, Bacchetti P, Sloan R, Stewart T, Andersson PB, Stabler G, Miller K. Serum MMP-9 and TIMP-1 levels are related to MRI activity in relapsing multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 1999;53:1397–1401. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.7.1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoyhtya M, Hujanen E, Turpeenniemi-Hujanen T, Thorgeirsson U, Liotta LA, Tryggvason K. Modulation of type-IV collagenase activity and invasive behavior of metastatic human melanoma (A2058) cells in vitro by monoclonal antibodies to type-IV collagenase. Int J Cancer. 1990;46:282–286. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910460224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turpeenniemi-Hujanen T, Thorgeirsson UP, Hart IR, Grant SS, Liotta LA. Expression of collagenase IV (basement membrane collagenase) activity in murine tumor cell hybrids that differ in metastatic potential. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1985;75:99–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar A, Bhatnagar S, Kumar A. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor batimastat alleviates pathology and improves skeletal muscle function in dystrophin-deficient mdx mice. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:248–260. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.091176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kherif S, Dehaupas M, Lafuma C, Fardeau M, Alameddine HS. Matrix metalloproteinases MMP-2 and MMP-9 in denervated muscle and injured nerve. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1998;24:309–319. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2990.1998.00118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miyazaki D, Nakamura A, Fukushima K, Yoshida K, Takeda S, Ikeda SI. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 ablation in dystrophin-deficient mdx muscle reduces angiogenesis resulting in impaired growth of regenerated muscle fibers. Hum Mol Genet. 2011 Feb;2011:2028. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr062. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li H, Mittal A, Makonchuk DY, Bhatnagar S, Kumar A. Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 Inhibition Ameliorates Pathogenesis and Improves Skeletal Muscle Regeneration in Muscular Dystrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:2584–2598. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kherif S, Lafuma C, Dehaupas M, Lachkar S, Fournier JG, Verdiere-Sahuque M, Fardeau M, Alameddine HS. Expression of matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 in regenerating skeletal muscle: a study in experimentally injured and mdx muscles. Dev Biol. 1999;205:158–170. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beggs AH. Dystrophinopathy, the expanding phenotype. Dystrophin abnormalities in X-linked dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1997;95:2344–2347. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.10.2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang KX, Denhardt DT. Osteopontin: role in immune regulation and stress responses. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2008;19:333–345. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen YJ, Wei YY, Chen HT, Fong YC, Hsu CJ, Tsai CH, Hsu HC, Liu SH, Tang CH. Osteopontin increases migration and MMP-9 up-regulation via alphavbeta3 integrin, FAK, ERK, and NF-kappaB-dependent pathway in human chondrosarcoma cells. J Cell Physiol. 2009;221:98–108. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rangaswami H, Bulbule A, Kundu GC. Nuclear factor-inducing kinase plays a crucial role in osteopontin-induced MAPK/IkappaBalpha kinase-dependent nuclear factor kappaB-mediated promatrix metalloproteinase-9 activation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:38921–38935. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404674200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vetrone SA, Montecino-Rodriguez E, Kudryashova E, Kramerova I, Hoffman EP, Liu SD, Miceli MC, Spencer MJ. Osteopontin promotes fibrosis in dystrophic mouse muscle by modulating immune cell subsets and intramuscular TGF-beta. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1583–1594. doi: 10.1172/JCI37662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Waller AH, Sanchez-Ross M, Kaluski E, Klapholz M. Osteopontin in cardiovascular disease: a potential therapeutic target. Cardiol Rev. 2010;18:125–131. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0b013e3181cfb646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kumar A, Bhatnagar S, Kumar A. Matrix Metalloproteinase Inhibitor Batimastat Alleviates Pathology and Improves Skeletal Muscle Function in Dystrophin-Deficient mdx Mice. Am J Pathol. 2010 doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.091176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mishra PK, Givvimani S, Metreveli N, Tyagi SC. Attenuation of beta2-adrenergic receptors and homocysteine metabolic enzymes cause diabetic cardiomyopathy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;401:175–181. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qipshidze N, Tyagi N, Sen U, Givvimani S, Metreveli N, Lominadze D, Tyagi SC. Folic acid mitigated cardiac dysfunction by normalizing the levels of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase and homocysteine-metabolizing enzymes postmyocardial infarction in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;299:H1484–1493. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00577.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Straub V, Rafael JA, Chamberlain JS, Campbell KP. Animal models for muscular dystrophy show different patterns of sarcolemmal disruption. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:375–385. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.2.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khurana TS, Davies KE. Pharmacological strategies for muscular dystrophy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2:379–390. doi: 10.1038/nrd1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kumar A, Boriek AM. Mechanical stress activates the nuclear factor-kappaB pathway in skeletal muscle fibers: a possible role in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. FASEB J. 2003;17:386–396. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0542com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miner EC, Miller WL. A look between the cardiomyocytes: the extracellular matrix in heart failure. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81:71–76. doi: 10.4065/81.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCawley LJ, Matrisian LM. Matrix metalloproteinases: they’re not just for matrix anymore! Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001;13:534–540. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00248-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nagase H, Woessner JF., Jr Matrix metalloproteinases. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:21491–21494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li YY, Feldman AM. Matrix metalloproteinases in the progression of heart failure: potential therapeutic implications. Drugs. 2001;61:1239–1252. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200161090-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fingleton B. Matrix metalloproteinases as valid clinical targets. Curr Pharm Des. 2007;13:333–346. doi: 10.2174/138161207779313551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bhatnagar S, Kumar A. Therapeutic targeting of signaling pathways in muscular dystrophy. J Mol Med. 2010;88:155–166. doi: 10.1007/s00109-009-0550-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lapidos KA, Kakkar R, McNally EM. The dystrophin glycoprotein complex: signaling strength and integrity for the sarcolemma. Circ Res. 2004;94:1023–1031. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000126574.61061.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Towbin JA, Bowles KR, Bowles NE. Etiologies of cardiomyopathy and heart failure. Nat Med. 1999;5:266–267. doi: 10.1038/6474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McNally E, Allikian M, Wheeler MT, Mislow JM, Heydemann A. Cytoskeletal defects in cardiomyopathy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2003;35:231–241. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(03)00018-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rando TA. The dystrophin-glycoprotein complex, cellular signaling, and the regulation of cell survival in the muscular dystrophies. Muscle Nerve. 2001;24:1575–1594. doi: 10.1002/mus.1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fingleton B. MMPs as therapeutic targets--still a viable option? Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2008;19:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mann DL, Spinale FG. Activation of matrix metalloproteinases in the failing human heart: breaking the tie that binds. Circulation. 1998;98:1699–1702. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.17.1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Romanic AM, Burns-Kurtis CL, Gout B, Berrebi-Bertrand I, Ohlstein EH. Matrix metalloproteinase expression in cardiac myocytes following myocardial infarction in the rabbit. Life Sci. 2001;68:799–814. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(00)00982-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Danielsen CC, Wiggers H, Andersen HR. Increased amounts of collagenase and gelatinase in porcine myocardium following ischemia and reperfusion. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1998;30:1431–1442. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1998.0711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lu L, Gunja-Smith Z, Woessner JF, Ursell PC, Nissen T, Galardy RE, Xu Y, Zhu P, Schwartz GG. Matrix metalloproteinases and collagen ultrastructure in moderate myocardial ischemia and reperfusion in vivo. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279:H601–609. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.2.H601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li YY, Feldman AM, Sun Y, McTiernan CF. Differential expression of tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases in the failing human heart. Circulation. 1998;98:1728–1734. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.17.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tyagi SC, Kumar SG, Haas SJ, Reddy HK, Voelker DJ, Hayden MR, Demmy TL, Schmaltz RA, Curtis JJ. Post-transcriptional regulation of extracellular matrix metalloproteinase in human heart end-stage failure secondary to ischemic cardiomyopathy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1996;28:1415–1428. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1996.0132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ducharme A, Frantz S, Aikawa M, Rabkin E, Lindsey M, Rohde LE, Schoen FJ, Kelly RA, Werb Z, Libby P, Lee RT. Targeted deletion of matrix metalloproteinase-9 attenuates left ventricular enlargement and collagen accumulation after experimental myocardial infarction. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:55–62. doi: 10.1172/JCI8768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tidball JG, Wehling-Henricks M. Damage and inflammation in muscular dystrophy: potential implications and relationships with autoimmune myositis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2005;17:707–713. doi: 10.1097/01.bor.0000179948.65895.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Engvall E, Wewer UM. The new frontier in muscular dystrophy research: booster genes. FASEB J. 2003;17:1579–1584. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1215rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Khurana TS, Davies KE. Pharmacological strategies for muscular dystrophy. 2003;2:379–390. doi: 10.1038/nrd1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Spencer MJ, Tidball JG. Do immune cells promote the pathology of dystrophin-deficient myopathies? Neuromuscul Disord. 2001;11:556–564. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(01)00198-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Spencer MJ, Walsh CM, Dorshkind KA, Rodriguez EM, Tidball JG. Myonuclear apoptosis in dystrophic mdx muscle occurs by perforin-mediated cytotoxicity. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:2745–2751. doi: 10.1172/JCI119464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Spencer MJ, Montecino-Rodriguez E, Dorshkind K, Tidball JG. Helper (CD4(+)) and cytotoxic (CD8(+)) T cells promote the pathology of dystrophin-deficient muscle. Clin Immunol. 2001;98:235–243. doi: 10.1006/clim.2000.4966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wehling-Henricks M, Sokolow S, Lee JJ, Myung KH, Villalta SA, Tidball JG. Major basic protein-1 promotes fibrosis of dystrophic muscle and attenuates the cellular immune response in muscular dystrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:2280–2292. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Morrison J, Palmer DB, Cobbold S, Partridge T, Bou-Gharios G. Effects of T-lymphocyte depletion on muscle fibrosis in the mdx mouse. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:1701–1710. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62480-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Takafuji V, Forgues M, Unsworth E, Goldsmith P, Wang XW. An osteopontin fragment is essential for tumor cell invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene. 2007;26:6361–6371. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yu Q, Stamenkovic I. Cell surface-localized matrix metalloproteinase-9 proteolytically activates TGF-beta and promotes tumor invasion and angiogenesis. Genes Dev. 2000;14:163–176. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Raffetto JD, Khalil RA. Matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in vascular remodeling and vascular disease. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;75:346–359. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ohtsuka T, Nishimura K, Kurata A, Ogimoto A, Okayama H, Higaki J. Serum matrix metalloproteinase-3 as a novel marker for risk stratification of patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. J Card Fail. 2007;13:752–758. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.06.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dwivedi A, Slater SC, George SJ. MMP-9 and -12 cause N-cadherin shedding and thereby beta-catenin signalling and vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;81:178–186. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Johnson JL, Devel L, Czarny B, George SJ, Jackson CL, Rogakos V, Beau F, Yiotakis A, Newby AC, Dive V. A selective matrix metalloproteinase-12 inhibitor retards atherosclerotic plaque development in apolipoprotein E-knockout mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:528–535. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.219147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Johnson JL, George SJ, Newby AC, Jackson CL. Divergent effects of matrix metalloproteinases 3, 7, 9, and 12 on atherosclerotic plaque stability in mouse brachiocephalic arteries. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15575–15580. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506201102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dogra C, Changotra H, Wergedal JE, Kumar A. Regulation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt and nuclear factor-kappa B signaling pathways in dystrophin-deficient skeletal muscle in response to mechanical stretch. J Cell Physiol. 2006;208:575–585. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kumar A, Khandelwal N, Malya R, Reid MB, Boriek AM. Loss of dystrophin causes aberrant mechanotransduction in skeletal muscle fibers. FASEB J. 2004;18:102–113. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0453com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kolodziejczyk SM, Walsh GS, Balazsi K, Seale P, Sandoz J, Hierlihy AM, Rudnicki MA, Chamberlain JS, Miller FD, Megeney LA. Activation of JNK1 contributes to dystrophic muscle pathogenesis. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1278–1282. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00397-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hnia K, Gayraud J, Hugon G, Ramonatxo M, De La Porte S, Matecki S, Mornet D. L-arginine decreases inflammation and modulates the nuclear factor-kappaB/matrix metalloproteinase cascade in mdx muscle fibers. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:1509–1519. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.071009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nakamura A, Yoshida K, Takeda S, Dohi N, Ikeda S. Progression of dystrophic features and activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases and calcineurin by physical exercise, in hearts of mdx mice. FEBS Lett. 2002;520:18–24. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02739-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nakamura A, Harrod GV, Davies KE. Activation of calcineurin and stress activated protein kinase/p38-mitogen activated protein kinase in hearts of utrophin-dystrophin knockout mice. Neuromuscul Disord. 2001;11:251–259. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(00)00201-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Acharyya S, Villalta SA, Bakkar N, Bupha-Intr T, Janssen PM, Carathers M, Li ZW, Beg AA, Ghosh S, Sahenk Z, Weinstein M, Gardner KL, Rafael-Fortney JA, Karin M, Tidball JG, Baldwin AS, Guttridge DC. Interplay of IKK/NF-kappaB signaling in macrophages and myofibers promotes muscle degeneration in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:889–901. doi: 10.1172/JCI30556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Evans-Anderson HJ, Alfieri CM, Yutzey KE. Regulation of cardiomyocyte proliferation and myocardial growth during development by FOXO transcription factors. Circ Res. 2008;102:686–694. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.163428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kumar M, Makonchuk DY, Li H, Mittal A, Kumar A. TNF-like weak inducer of apoptosis (TWEAK) activates proinflammatory signaling pathways and gene expression through the activation of TGF-beta-activated kinase 1. J Immunol. 2009;182:2439–2448. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Li H, Mittal A, Paul PK, Kumar M, Srivastava DS, Tyagi SC, Kumar A. Tumor necrosis factor-related weak inducer of apoptosis augments matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) production in skeletal muscle through the activation of nuclear factor-kappaB-inducing kinase and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase: a potential role of MMP-9 in myopathy. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:4439–4450. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805546200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]