Abstract

The biogenesis of isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP) is accomplished by the methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway in plants, bacteria and parasites, making it a potential target for the development of anti-infective agents and herbicides. The biosynthetic enzymes comprising this pathway catalyze intriguing chemical transformations on diphosphate scaffolds, offering an opportunity to generate novel analogs in this synthetically challenging compound class. Such a biosynthetic approach to generating new diphosphate analogs may involve transformation through discrete diphosphate species, presenting unique challenges in structure determination and characterization of unnatural enzyme-generated diphosphate products produced in tandem. We have developed 1H–31P–31P correlation NMR spectroscopy techniques for the direct characterization of crude MEP pathway enzyme products at low concentrations (200 μM to 5 mM) on a room temperature (non-cryogenic) NMR probe. Coupling the 100% natural abundance of the 31P nucleus with the high intrinsic sensitivity of proton NMR, 1H–31P–31P correlation spectroscopy is particularly useful for characterization of unnatural diphosphate enzyme products in the MEP pathway. As proof of principle, we demonstrate the rapid characterization of natural enzyme products of the enzymes IspD, E and F in tandem enzyme incubations. In addition, we have characterized several unnatural enzyme products using this technique, including new products of cytidyltransferase IspD bearing erythritol, glycerol and ribose components. The results of this study indicate that IspD may be a useful biocatalyst and highlight 1H–31P–31P correlation spectroscopy as a valuable tool for the characterization of other unnatural products in non-mammalian isoprenoid biosynthesis.

Introduction

Isoprenoids comprise the most structurally diverse class of natural products, and play important roles in all living organisms. A distinct methylerythritol phosphate (MEP)¶ pathway in plants, bacteria and parasites (Scheme 1) leads to the production of the essential isoprenoid bioprecursors IPP and DMAPP.1–3 The unique catalysis exhibited by the MEP pathway and its wide distribution in human pathogens underscore its value as a potential target for the development of anti-infective agents. These intriguing biosynthetic enzymes catalyze transformations on synthetically challenging diphosphate scaffolds and may be equally valuable as biocatalysts for the generation of novel diphosphate analogs which are otherwise difficult to access. Employing the MEP pathway enzymes themselves for the biosynthesis of diphosphate analogs presents itself as an attractive approach for the generation of diverse mechanistic probes of downstream enzymes. To explore these biosynthetic enzymes as biocatalysts, we have sought a technique that permits the direct characterization of novel enzyme products of single or multistep biosyntheses using the MEP pathway enzymes IspD, E and F.

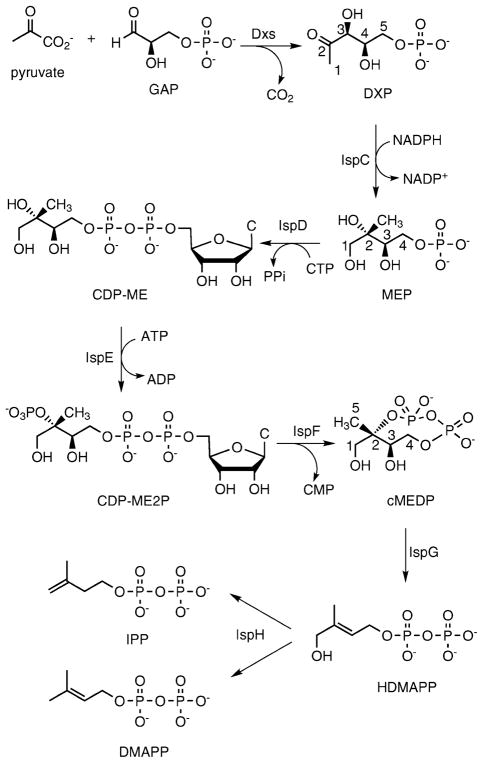

Scheme 1.

Methylerythritol phosphate pathway to produce IPP and DMAPP.

The existing method for structural characterization of MEP pathway intermediates utilizes a combination of 13C and 31P NMR.4–6 Rohdich and colleagues have employed multistep enzyme-assisted syntheses for the preparation of labeled MEP pathway intermediates to characterize enzyme products of each biosynthetic step to IPP and DMAPP. In this method, structural characterization of labeled enzyme products was accomplished following purification in each case. However, studies to further explore the capacity of MEP pathway enzymes to process alternative substrates demand a method that is flexible enough to accommodate characterization of structurally diverse enzyme products and to preclude the need for isotopic labeling or enrichment. Principal modifications to the methylerythritol scaffold which are achieved by MEP pathway biosynthetic enzymes involve phosphorylation or alteration of the phosphorylation pattern. Thus, the 31P nuclei are central for identifying and characterizing these compounds. The unique phosphorylation chemistry catalyzed by the MEP pathway coupled with a 100% natural abundance of the 31P nucleus makes 31P NMR an especially useful tool to study novel enzyme products.

One-dimensional 31P{1H} NMR provides structural information for phosphorylated compounds such that mono-and diphosphate species may be distinguished by noting the presence or absence of scalar 31P–31P coupling (JPP) and in some cases scalar 1H–31P coupling. However, 1D 31P{1H} NMR techniques are limited by the need for high millimolar concentrations of phosphorylated species, and detailed structural information to discriminate between linear and cyclic diphosphate species cannot be obtained. Developments in NMR spectroscopy have afforded sensitive polarization transfer experiments in which proton nuclei with vicinal scalar coupling to 31P nuclei are selectively observed in two-dimensional 1H–{31P} “inverse-detection” NMR spectroscopy experiments.7–14 Building upon the sensitivity of 1H–{31P} coupling experiments, we have developed 1H–31P–31P correlation spectroscopy for the direct characterization of H–P–P–H J-coupling networks. This method provides detailed structural information that leads to the facile distinction of linear from cyclic diphosphate analogs in the MEP pathway without the need for 13C-enrichment or purification of enzyme products. Herein, we report 1H–31P–31P correlation NMR spectroscopy for the characterization of crude natural and unnatural MEP pathway enzyme intermediates generated in tandem incubations at biochemically relevant concentrations. We have further applied the 1H–31P–31P COSY techniques for the direct characterization of novel enzyme products bearing glycerol and ribose components in a preliminary substrate usage study of cytidyltransferase IspD. The identification of these products by 1H–31P–31P COSY was accomplished from low micromolar to low millimolar concentrations, even on a non-cryogenic room temperature, inverse (1H) detection NMR probe at 500 MHz (1H). These studies reveal that IspD is capable of catalyzing cytidyl transfer to alternative monophosphate substrates, an important first step to the enzymatic synthesis of structurally diverse diphosphates using MEP pathway enzymes.

Results

1H–31P HSQC and 1H–31P–31P COSY analysis of authentic cMEDP

As a starting point, we demonstrate 1H–31P–31P COSY techniques to characterize the substrate of IspG, cMEDP (Scheme 1). IspF catalyzes the unusual cyclization reaction to form cMEDP (Scheme 1) and will be a key enzymatic step for the generation of new cyclic diphosphate analogs to study downstream MEP pathway enzymes. The change in phosphorylation status in the conversion of CDP-ME2P to cMEDP constitutes a unique challenge in structure determination as the presence of diphosphate-type linkages persists, but connectivity to the diphosphate through the erythritol scaffold is altered. The potential complexities of tracking cyclization led us to develop the 1H–31P HSQC and 1H–31P–31P COSY techniques on a purified sample of synthetically prepared cMEDP.15 Here we present a detailed 1H–31P–31P COSY analysis of cMEDP which provides a basis for extending 1H–31P–31P COSY techniques to characterize new enzyme products throughout the MEP pathway.

Details of the pulse sequences used and data acquisition parameters are elaborated in the ESI‡. In this work 1H–31P HSQC spectra consist of cross-peaks (referred to as “auto” peaks in this work) between 1H and 31P nuclei correlated by an nJHP coupling constant, where n is the number of intervening covalent bonds. Fig. 1 shows a high-resolution 1H–31P HSQC spectrum of a 5 mM sample of purified cMEDP in D2O at 19 °C. The spectrum in Fig. 1a consists of two sets of “auto” peaks, correlating the diastereotopic protons H4 and H4′with PA (3JH4PA) and the CH3 protons (H5) with PB (4JH5PB). As expected, each auto peak (Fig. 1a) is split into a doublet(2JPP ≈ 20–25 Hz) in the 31P dimension, which is typical of P–O–P diphosphate linkages in this class of compounds,16 establishing that PA and PB are individually coupled to a second 31P nucleus in cMEDP. Fig. 1b shows a constant-time version of the HSQC spectrum.17,18 By setting the period TC (ESI‡, Fig. S2) to 1/JPP (41 ms), the 31P doublets are effectively “homo-decoupled” and “collapse” into singlets in the 31P dimension (Fig. 1b). Constant-time experiments offer two major advantages, particularly when signal loss due to 31P relaxation during TC is minimal (observed in all systems studied here): (1) improved resolution of closely spaced peaks in the 31P dimension due to the homo-decoupling effect (the spectrum in Fig. 1b was acquired in about one-third the time as the spectrum in Fig. 1a, but shows the same level of resolution), and (2) rapid distinction between mono- and polyphosphorylated species, because mono- and polyphosphorylated species appear with opposite phases.

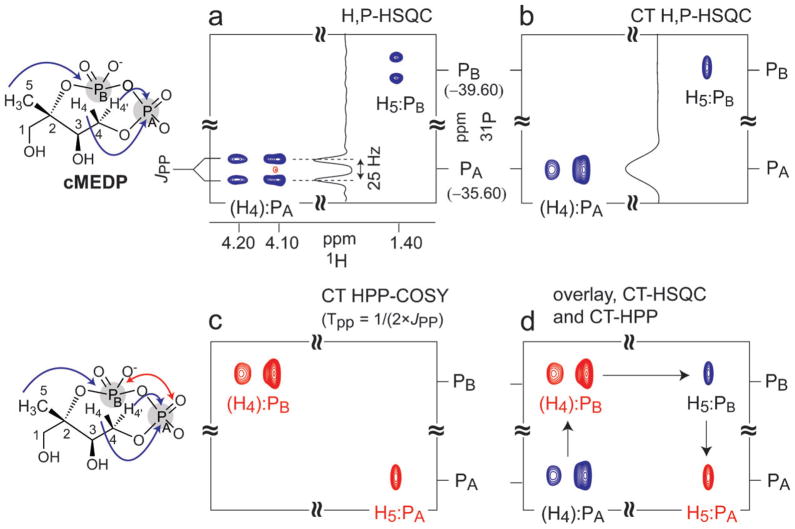

Fig. 1.

Regions of 1H–31P HSQC and CT 1H–31P–31P COSY spectra of a 5 mM sample of authentic cMEDP recorded at 19 °C, in D2O. H4 and H4′protons are abbreviated as (H4). Magnetization transfer pathways are indicated by blue (1H → 31P) and red (31P → 31P) arrows on the molecular structure. (a) High-resolution 1H–31P HSQC (thp = 100 ms), showing (H4, H4′):PA and H5:PB correlations and splittings due to 2JPAPB coupling constants (~20–25 Hz) in the 31P dimension. (b) Constant-time 1H–31P HSQC with TC = 1/JPP (40 ms) showing the collapse of the 31P doublet in the 31P dimension. (c) CT 1H–31P–31P COSY spectrum acquired with the same parameters as in (b) and tpp = 10.0 ms (TPP=1/(2 × JPP)), for complete magnetization transfer between PA and PB. (d) Overlay of the spectra in (b) and (c) to demonstrate the complete (H4, H4′)–PA–PB–H5 connectivity (indicated by arrows). All spectra were folded in the 31P dimension to obtain high-resolution in 31P in a short time period.

To unambiguously establish that PA and PB are indeed coupled to each other, an “out-and-back” H–31P–31P COSY spectrum was acquired which exhibits correlations between PA and PB along the 31P dimension. A CT-version of the experiment was used for reasons cited above. Acquiring the 1H–31P–31P COSY spectrum with TPP = 1/(2 × JPP) (ESI‡, Fig. S2) results in complete magnetization transfer from one 31P nucleus to its coupled partner (PA:PB) and produces a “cosy cross-peak only” spectrum (Fig. 1c) with complete phase inversion relative to the HSQC spectrum (Fig. 1b). This is evident from the presence of H4:PB and H5:PA cosy peaks in Fig. 1c. A superimposition or comparison of HSQC and 1H–31P–31P spectra illustrates the complete HA–PA–PB–HB connectivity for the H4–PA–PB–H5 network (Fig. 1d).

The 1H–31P–31P COSY experiments carried out on cMEDP clearly establish PA:PB coupling and result in complete characterization of the H4–PA–PB–H5 network. Importantly, we not only establish the identity of the PA–PB connectivity but also anchor these 31P nuclei to appropriate protons in the molecule for a more accurate characterization.

1H–31P HSQC and 1H–31P–31P COSY for direct characterization of MEP pathway intermediates

The successful characterization of cMEDP motivated us to undertake the challenge of applying the 1H–31P–31P COSY technique to detect and distinguish other MEP pathway intermediates in crude enzyme reactions as a prelude to studies probing alternative substrate usage by these biosynthetic enzymes. Thus, the 1H–31P–31P COSY experiment was applied to three biosynthetic steps of the MEP pathway which catalyze phosphorylation or alter the phosphorylation pattern of biosynthetic intermediates. Enzymatic transformations in this series of experiments were performed at low millimolar substrate concentration (generally 5 mM) using recombinant enzymes IspD, E and F. The overall conversion of MEP to cMEDP was accomplished by the tandem action of IspD, E and F, and accumulation of the corresponding enzyme intermediates was monitored by HPLC to ensure complete conversion of substrate to product at each step. Enzyme products at each step were then characterized by 1H–31P HSQC and 1H–31P–31P COSY. Due to the simplicity of spectra, only CT 1H–31P HSQC and CT 1H–31P–31P COSY data are presented in this report. An artificial color coding scheme for peaks has been used, as described below; however, it must be noted that all CT 1H–31P HSQC peaks corresponding to diphosphate moieties are opposite in phase relative to monophosphate peaks.

The entire reaction sequence is presented in Fig. 2, and the details of the analysis are presented below. Incorporation of a diphosphate linkage to form CDP-ME upon addition of IspD and CTP to MEP is evident by the appearance of new 1H–31P correlation peaks ((H5′, H5″):PC) and a downfield chemical shift in the proton dimension of the diastereotopic (H4, H4′):PA correlation peaks relative to MEP (Fig. 2b). Full characterization of the H4–PA–PC–H5′ network in CDP-ME was accomplished using the CT 1H–31P–31P COSY experiment with full magnetization transfer between 31P nuclei. A superimposition of the CT 1H–31P HSQC and CT 1H–31P–31P COSY spectra is shown in Fig. 2c to illustrate the H4–PA–PC–H5′ connectivity.

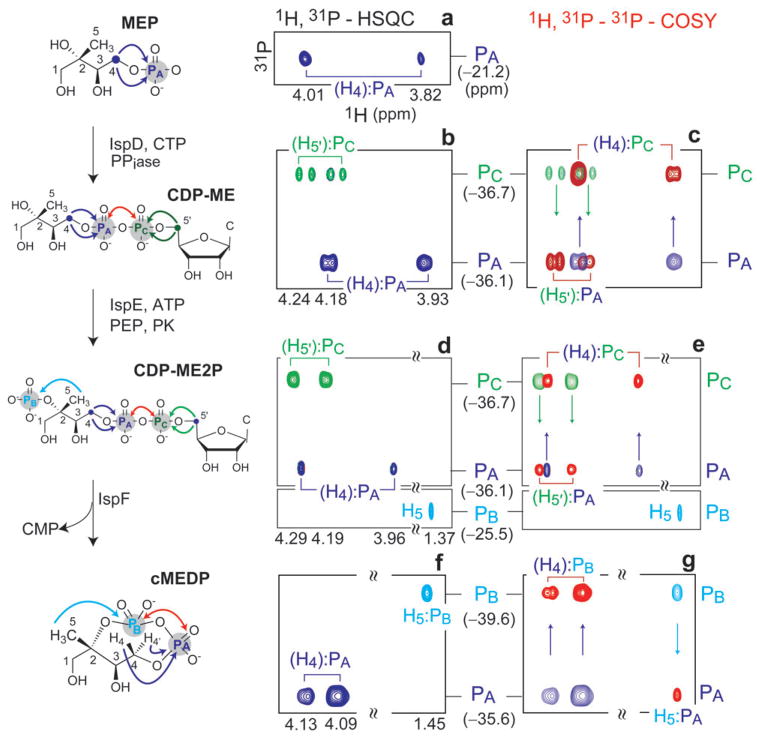

Fig. 2.

1H–31P-HSQC, CT 1H–31P-HSQC and CT 1H–31P–31P COSY spectra of intermediates generated in tandem using IspD, E and F. Diastereotopic protons (Hn, Hn′) or (Hn′, Hn″) have been abbreviated as (Hn). IspD substrate (MEP) and enzyme intermediates are shown on the left, with arrows indicating magnetization transfer pathways (1H→31P in blue, green or cyan, and 31P→31P in red). 1H:31P auto and 1H–31P–31P cosy peaks have been color coded accordingly. COSY connectivities are indicated by arrows in HPP spectra. (a) HP-HSQC of MEP showing correlations between the diastereotopic H4 and H4′protons and PA. (b) CT-HP-HSQC of CDP-ME showing (H4, H4′):PA (blue) and (H5′, H5″):PC (green) correlations from the methylerythritol and cytidyl moieties, respectively. (c) Overlay of the spectrum in (b) and a CT-HPP spectrum of CDP-ME exhibiting (H4, H4′):PC and (H5′, H5″):PA cosy correlations, to establish the (H4, H4′)–PA–PC–(H5′, H5″) diphosphate linkage. (d) CT-HSQC of CDP-ME2P showing (H4, H4′):PA (blue) and (H5′, H5″):PC (green) correlations from the diphosphate linkage and the H5:PB correlation (cyan, lower panel) from the monophosphate. (e) Overlay of (d) and a CT-HPP spectrum of CDP-ME2P, exhibiting (H4, H4′):PC and (H5′, H5″):PA (cosy), and H5:PB (auto) correlation (cyan). (f) CT-HSQC of cMEDP showing (H4, H4′):PA (green) and H5:PB (cyan) auto correlations. (g) Overlay of (f) and a CT-HPP spectrum of cMEDP exhibiting (H4, H4′):PB and H5:PA cosy correlations to establish the (H4, H4′)–PA–PB–(H5) diphosphate connectivity.

The structural similarity of CDP-ME and CDP-ME2P (Scheme 1) through the diphosphate linkage is evident in the CT 1H–31P HSQC spectrum in which the same set of correlations were observed in CDP-ME2P for the diphosphate group (H4:PA and H5′:PC) as for CDP-ME (Fig. 2d), with minor chemical shift and sensitivity perturbations. Identification of the newly incorporated 2-phosphate moiety (PB) unique to the IspE enzyme product was accomplished by detection of the H5:PB correlation. Consistent with a previous report,5 4JH5PB coupling of the H5 resonance could not be discerned from a high-resolution 1D proton spectrum, indicating that 4JH5PB is likely less than 0.75 Hz, the observed linewidth of the H5 proton resonance in our sample. However, we were able to observe the H5:PB auto peak (Fig. 2d, lower panel colored cyan) with a maximum intensity at thp = 125 ms (see NMR experiments and analysis). The observation of such a weak signal at low millimolar concentration is evidence of the high intrinsic sensitivity of these experiments. As expected, the phase of the H5:PB correlation remains unchanged in the CT 1H–31P–31P COSY spectrum (Fig. 2e), consistent with monophosphate behavior. Correlation of H3 with both mono- and diphosphate 31P nuclei would provide even more compelling evidence that CDP-ME2P incorporates all three 31P nuclei PA, PB and PC; however, we were unable to observe this correlation in 1H–31P HSQC experiments. Notably, the C3 carbon has a large (~7 Hz) coupling to both PB and PA,5,19 making possible the acquisition of a 1H–13C–31P correlated spectrum at natural abundance 13C (ESI‡, Fig. S3).

The final enzymatic step in the tandem incubation produced cMEDP upon the addition of IspF. Spectra acquired on crude enzyme product from this reaction (Fig. 2f and g) were identical to those shown for the authentic cMEDP in Fig. 1c and d. Thus, detection and complete characterization of the changing phosphorylation pattern is accomplished through the IspD, E, F tandem enzyme sequence and provides a basis for the characterization of novel enzyme products using 1H–31P–31P correlation spectroscopy.

1H–31P HSQC and 1H–31P–31P COSY for direct characterization of unnatural MEP pathway intermediates

We expect the 1H–31P–31P COSY experiments described here will be valuable for the detection and characterization of unnatural MEP pathway intermediates. Below, we report the enzymatic synthesis of several unnatural products of these biosynthetic enzymes and characterization using 1H–31P–31P correlation spectroscopy. First, we have prepared erythritol phosphate (EP), the desmethyl IspD substrate analog, and subjected it to the IspD, E, F tandem enzyme sequence as described above. Second, we report the enzymatic synthesis and 1H–31P–31P COSY characterization of two new IspD products bearing ribose and glycerol components.

Chemoenzymatic synthesis of CDP-E, CDP-E2P and cEDP from erythritol phosphate

CDP-E, CDP-E2P and cEDP were generated in tandem from EP by the action of IspD, E and F, respectively. 1H–31P–31P NMR analyses were carried out as described above, and the constant-time data for the entire reaction sequence are shown in Fig. 3. The data are presented as overlays of the CT-HSQC and CT 1H–31P–31P COSY spectra in each case. Overall, the profile for transformation of EP (IspD substrate) to cEDP (IspF product) closely resembles that of the natural tandem reaction scheme (Fig. 2). The major distinguishing feature is the presence of H2:PB correlations observed in CDP-E2P (IspE product, Fig. 3b) and H2:PB auto and H2:PA cross-peaks observed in the CT-HSQC and CT 1H–31P–31P COSY spectra for the corresponding IspF product, cEDP (Fig. 3c). In contrast to the H5:PB correlation observed in CDP-ME2P (Fig. 2d,e), the H2:PB correlation is significantly more intense, indicating a larger 3JH2PB coupling (~13 Hz), as would be expected. Thus, complete characterization of the changing phosphorylation pattern of EP to cEDP is accomplished by 1H–31P–31P NMR.

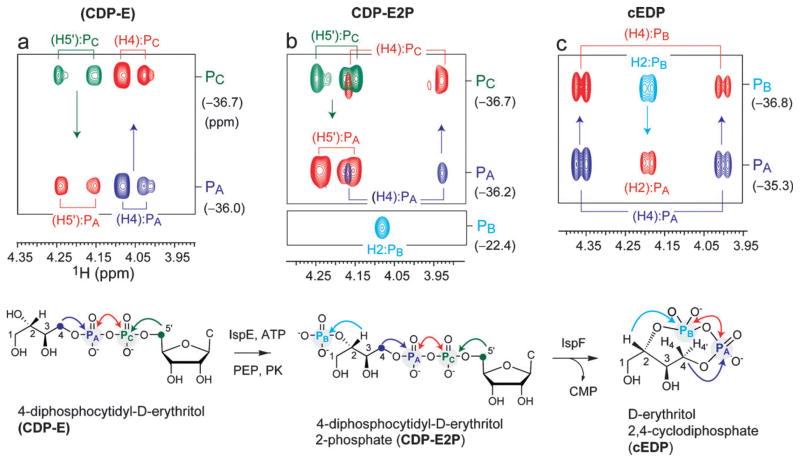

Fig. 3.

Overlays of CT 1H–31P-HSQC and CT 1H–31P–31P COSY spectra of intermediates generated from the tandem action of IspD, E and F on the unnatural substrate erythritol phosphate (EP). Diastereotopic protons (Hn, Hn′) or (Hn′, Hn″) have been abbreviated (Hn). Molecular structures of intermediates are shown below each spectrum. Color coding of arrows indicating magnetization transfer pathways and peaks in the spectrum follows the scheme used in Fig. 2. COSY connectivities are indicated by arrows in the HPP spectra. (a) Overlay spectra of CDP-E, showing (H4, H4′):PA (blue) and (H5′, H5″):PC (green) “auto” peaks from CT-HSQC and (H4, H4′):PC and (H5′, H5″):PA “cosy” peaks from CT-HPP COSY, to identify the (H4, H4′)–PA–PC–(H5′, H5″) diphosphate linkage. (b) Overlay spectra of CDP-E2P, identifying the terminal monophosphate linkage via the H2:PB correlation (cyan, lower panel). The (H4, H4′)–PA–PC–(H5′, H5″) diphosphate linkage is identified analogous to CDP-E in (b), via (H4, H4′):PA (blue) and (H5′, H5″):PC “auto” peaks (green) and (H4, H4′):PC and (H5′, H5″):PA “cosy” peaks. (c) Overlay spectra of cEDP, showing (H4, H4′):PA (blue) and H2:PB (cyan) “auto” peaks and (H4, H4′):PB and H2:PA “cosy” peaks, which establish the formation of the rearranged (H4, H4′)–PA–PB–H2 linkage.

Studying substrate usage of IspD using 1H–31P–31P COSY

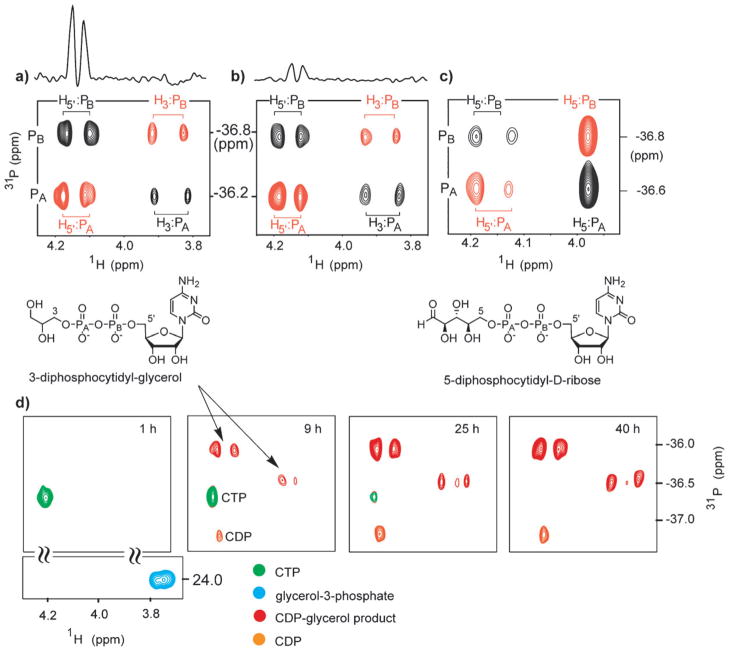

The 1H–31P–31P NMR experiments described above for the direct characterization of products in crude, tandem enzyme incubations highlights this technique as a useful tool to identify unnatural enzyme products in the MEP pathway. Thus, we have used 1H–31P–31P NMR in a preliminary study to probe substrate usage of IspD. As noted above, IspD incorporates the cytidyl group as an important binding element in the CDP-ME scaffold (Scheme 1). The enzyme is known to accept erythritol 4-phosphate as substrate,20 but its substrate specificity has not been examined further. Some structural similarity of IspD to bacterial CTP–glycerol-3- phosphate cytidyltransferase (GCT) has been noted.21 Here we demonstrate that IspD is capable of catalyzing a similar reaction to form 3-diphosphocytidyl-glycerol (CDP-glycerol) in the presence of glycerol 3-phosphate and CTP. In addition, we demonstrate the IspD-catalyzed formation of 5-diphosphocytidyl- D-ribose.

The formation of ribose- and glycerol-containing products of IspD was accomplished in the presence of 7 μM IspD. Enzyme inhibition by CTP was previously reported.22 Therefore, for experiments described here using unnatural monophosphate substrates, the concentration of CTP was kept below 750 μM. Reactions were monitored by HPLC for the disappearance of CTP and the appearance of product peaks bearing the cytidine chromophore. The conversion of glycerol-3-phosphate to a new species in the presence of CTP and IspD was observed by HPLC, and the product formed was characterized by 1H–31P–31P NMR. In addition, the conversion of ribose-1-phosphate to a new species in the presence of CTP and IspD was observed by HPLC, and the product formed was similarly characterized by NMR. Fig. 4a and c show overlays of CT-HSCQ and 1H–31P–31P COSY spectra for 3-diphosphocytidyl-glycerol and 3-diphosphocytidyl- D-ribose, respectively. The structural similarities of these unnatural IspD products to CDP-ME (Fig. 2) are evident. The diastereotopic H5′:PB correlation peaks in each product closely resemble those observed in CDP-ME, with minor perturbations in chemical shift. 3-Diphosphocytidyl-glycerol exhibits diastereotopic H3:PA correlation peaks as well (Fig. 4a). In contrast, only one ribose H5:PA correlation peak is visible, consistent with this correlation in the ribose-5- phosphate substrate (data not shown). As in previous experiments, the H3–PA–PB–H5′and H5–PA–PB–H5′networks in 3-diphosphocytidyl-glycerol and 5-diphosphocytidyl-D-ribose, respectively, are established in the 1H–31P–31P COSY experiment. The characterization of these products by 1H–31P NMR confirms the formation of unnatural products 3-diphosphocytidyl- glycerol and 5-diphosphocytidyl-ribose by the action of cytidyltransferase IspD. Importantly, these results offer early evidence that this catalyst will tolerate both the removal of the hydroxymethyl substituent in MEP as well as lengthening of the carbon chain of the monophosphate substrate.

Fig. 4.

Cytidyltransferase IspD catalyzes formation of two new diphosphate species. (a) Characterization of 3-diphosphocytidyl-glycerol (765 μM) following reaction of glycerol-3-phosphate with CTP in the presence of IspD. The data are shown as an overlay of CT-HSQC and CT-HPP COSY to illustrate the H3–PA–PB–H5′network. (b) Characterization of 3-diphosphocytidyl-glycerol at 200 μM following serial dilutions into reaction buffer, shown as an overlay of CT-HSQC and CT-HPP COSY as in (a). Above the (a) and (b) panels are shown cross sections parallel to the 1H axis, taken through the H5′:PB cross-peak in the CT-HSQC spectrum, to indicate signal-to-noise quality in the spectrum. (c) Characterization of 5-diphosphocytidyl-D-ribose (325 μM) following reaction of ribose-5-phosphate with CTP in the presence of IspD. A 1H–31P HSQC/1H–31P–31P COSY overlay illustrates the H5–PA–PB–H5′network. (d) 1H–31P CT-HSQC snapshots over time showing enzymatic 3-diphosphocytidyl-glycerol formation concomitant with the disappearance of CTP and appearance of CDP degradation product. The different species have been artificially color coded according to the key. The glycerol-3-(mono) phosphate correlation (shown only in the first panel) is always of opposite phase relative to all other species (di- or triphosphates). Each spectrum in (d) was acquired in about 6 minutes.

In the experiment described above, detection of 3-diphosphocytidyl- glycerol and 5-diphosphocytidyl-ribose was accomplished at product concentrations well below 5 mM. To further examine the limits of detection, we carried out 1H–31P–31P COSY analysis on serially diluted samples of the 3-diphosphocytidyl-glycerol IspD product. In this experiment, the starting product concentration was 765 μM, and dilutions were made into enzyme reaction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 5 mM MgCl2, 10% v/v D2O). The successful characterization of 3-diphosphocytidyl-glycerol was accomplished on a dilute product sample in the mid-micromolar range (200 μM) on a non-cryogenic probe (Fig. 4b), demonstrating the intrinsic sensitivity of 1H–31P–31P correlation spectroscopy for characterization of new enzyme products. Presumably the use of a cryogenic probe would offer an additional 2- to 4-fold increase in sensitivity.

Time course analysis of enzymatic 3-diphosphocytidyl-glycerol formation using 1H–31P HSQC

The high sensitivity of these experiments suggests that it is possible to directly monitor these enzyme reactions continuously using the 1H–31P correlation spectroscopy techniques developed here. Here, we demonstrate continuous detection of 3-diphosphocytidyl-glycerol product formation using 1H–31P CT-HSQC (Fig. 4d). In this experiment, glycerol-3-phosphate (3 mM) was incubated with CTP (750 μM), IspD (7 μM) and inorganic pyrophosphatase (5U) in enzyme buffer at 37 °C. The enhanced resolution of closely spaced 31P resonances as well as the facile distinction between mono- and diphosphates in CT-HSQC experiments permits data acquisition to give high information content within 5 to 10 minutes at each time point. The relatively large 2JPP coupling constants (20 to 25 Hz) permitted the use of short constant time periods (~40 ms), resulting in high sensitivity with minimal signal loss due to 31P relaxation. Here, product is observable within 4 hours with concomitant formation of CDP, presumably via degradation of CTP. On the basis of the sensitivity experiments described above for the formation of 3-diphosphocytidyl-glycerol, we estimate that product formation here is detectable at a concentration of ~0.5 mM in a 5 to 10 minute data acquisition time, representing about 65% conversion of CTP to the corresponding CDP-glycerol product. Longer acquisition times would yield higher sensitivity and allow earlier detection of product. Importantly, this experiment demonstrates that we are able to easily distinguish substrates from products in potentially complex mixtures of polyphosphorylated species.

Discussion

Assessing the capacity of MEP pathway enzymes to process alternative substrates is essential for developing chemoenzymatic approaches to generate new, synthetically challenging diphosphate analogs. The technique reported here allows the direct characterization of new enzyme products of single or multistep biosyntheses in which the intermediates produced are distinguished by a change in phosphorylation status. Importantly, these 1H–31P–31P COSY techniques make possible the direct characterization of crude enzyme products at low concentration (200 μM to 5 mM) and obviate any need for 13C-enrichment or purification procedures. Thus, 1H–31P–31P COSY not only offers flexibility for the characterization of new compounds in this system, but also will complement existing techniques for the study of catalysis in the MEP pathway.

These experiments take advantage of the high sensitivity of 1H NMR and multiple-bond nJHP scalar couplings to reveal the distinctive 1H–31P and 1H–31P–31P–1H connectivities that distinguish the various intermediates of the MEP pathway. Rigorous distinction between monophosphate and dissimilar diphosphate linkages is feasible in the 1H–31P–31P COSY experiment, in which magnetization is transferred from one 31P nucleus to a neighboring coupled 31P nucleus and reported on appropriate J-coupled protons. The relatively large 31P–31P coupling constants (~20–25 Hz) in the compounds studied here permits the use of constant-time versions of these experiments with high sensitivity, resulting in apparent “homo-decoupling” in the 31P dimension and associated enhancement in resolution.

A particular challenge in the characterization of MEP pathway intermediates was detection of the C5 methyl correlation to PB in both natural IspE and IspF enzyme products (Fig. 2). The observation of the very weak vicinal coupling between the C5 methyl protons and PB emphasizes the high intrinsic sensitivity of these experiments. As expected, a notable improvement in sensitivity was observed for characterization of the H–P–P–H networks in unnatural enzyme products CDP-EP and cEDP (Fig. 3) where the appropriate 3JHP was at least an order of magnitude larger.

Finally, we have highlighted the utility of 1H–31P–31P COSY for characterization of unnatural enzyme products in a preliminary study of IspD substrate usage. We reported here the characterization of unnatural IspD products containing erythritol, glycerol and ribose components. We have further established the intrinsic sensitivity of these experiments for direct detection of the glycerol-containing IspD product at mid-micromolar concentration (Fig. 4), and demonstrated the feasibility of monitoring product formation continuously by 1H–31P HSQC. These results suggest that IspD is reasonably flexible toward monophosphate substrates and may be a useful catalyst in the enzymatic synthesis of new diphosphate analogs. Furthermore, these results underscore 1H–31P–31P correlation spectroscopy as a valuable tool for the characterization of other unnatural products in non-mammalian isoprenoid biosynthesis.

Conclusion

The 1H–31P–31P COSY techniques reported here tackle the particularly challenging issue in biochemistry of detecting changes in phosphorylation patterns at low concentration. The unique phosphorylation chemistry catalyzed by MEP pathway enzymes presents interesting challenges in structure determination, especially for new compounds that may be generated chemoenzymatically using these enzymes. The versatile method described here overcomes these challenges and offers new avenues for compound characterization in the MEP pathway and for other phosphorylated species of biological interest. Lastly, the discovery of new cytidyltransferase catalytic activities merits further examination of IspD not only as a drug target, but also as a biocatalyst.

Experimental

Instrumentation

HPLC analysis of enzyme mixtures was carried out on a Beckman 32 Karat HPLC equipped with a photodiode array detector and autosampler. 1H–31P NMR spectra were acquired on a Varian INOVA spectrometer operating at 500 MHz (1H frequency), on a pentaprobe equipped with z-axis pulsed-field gradient coils. It should be noted that all experiments described here may also be performed on a standard, “inverse-detection” H-X probe. 3-Diphosphocytidyl-glycerol and 5-diphosphocytidyl-5-D-ribose spectra were acquired at 35 °C. The time course analysis of 3-diphosphocytidyl- glycerol formation was carried out at 37 °C. All other spectra were acquired at 19 °C. Data were processed and analyzed using nmrPipe23 and visualized using nmrDraw software.

Enzymatic synthesis of natural IspD, E and F products

The enzymes IspD, IspE and IspF were overexpressed and purified from Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) cells harboring recombinant plasmids ispD-pET37b, ispE-pET16b and ispF-pET28b, respectively. Enzyme reactions to form natural MEP pathway intermediates were carried out in tandem and analyzed by HPLC to observe complete conversion of CTP to time-dependent and enzyme-dependent product peaks. Tandem enzyme incubations were initiated by addition of IspD (1 μM) to MEP (5 mM) and CTP (5 mM) in 100 mM Tris hydrochloride, pH 8.0, MgCl2 (5 mM) and dithiothreitol (5 mM). Inorganic pyrophosphatase (5 U) was added to drive the reaction to completion.19 The enzyme mixture was incubated at 37 °C and monitored by HPLC using the following procedure: 25 μL aliquots were quenched in 25 μL cold methanol. The quenched mixtures were incubated at 4 °C for 20 min, and the supernatants were analyzed by HPLC (ESI‡, Fig. S1). Under these reaction conditions, the disappearance of CTP to form CDP-ME was complete within 10 min.

Conversion of CDP-ME to CDP-ME2P was accomplished by addition of 10 mol% ATP (0.5 mM) and IspE (1 μM) to the IspD reaction mixture. Phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP, 7 mM) and pyruvate kinase (PK, 3.5 U) were added to recycle ADP to ATP.19 The mixture was incubated at 37 °C and analyzed by HPLC using the method described above. Complete conversion of CDP-ME to CDP-ME2P was observed within 15 min. The product of IspE was then converted in tandem to cMEDP and CMP by the addition of IspF (1 μM). Disappearance of CDP-ME2P to form CMP was complete within 30 min.

Enzymatic synthesis of unnatural erythritol-containing IspD, E and F products

Enzyme reactions to form the unnatural erythritol enzyme products were carried out as described above.

Enzymatic synthesis of 3-diphosphocytidyl-glycerol via the action of IspD

The enzyme reaction to form 3-diphosphocytidyl-glycerol was analyzed by HPLC to observe depletion of CTP and formation of a new time-dependent and enzyme-dependent product peak. The reaction was initiated by addition of IspD (7 μM) to DL-glycerol-3-phosphate (3 mM) and CTP (300 μM) in 50 mM Tris hydrochloride, pH 8.0 and MgCl2 (5 mM). Inorganic pyrophosphatase (5 U) was added to drive the reaction to completion as described above. The enzyme mixture was incubated at 37 °C and monitored by HPLC using the procedure described above for the natural IspD product. Under these reaction conditions, the disappearance of CTP was accompanied by the appearance of a new product peak assumed to be 3-diphosphocytidyl-glycerol. The reaction had proceeded to 50% completion within 5 h. Additional CTP was added (500 μM), and the reaction was incubated for an additional 3 h at 37 °C. HPLC analysis indicated a 35:65 product–CTP mixture with a final product concentration of 280 μM at the time 1H–31P COSY analysis was initiated. Further conversion during NMR analysis was noted.

For experiments to test the detection limits of 1H–31P–31P COSY, this reaction was allowed to run to completion, and serial dilutions were made into reaction buffer (5mM MgCl2, 50 mM Tris, pH 8, 10% D2O). The initial 3-diphosphocytidyl-glycerol concentration was 765 μM, and the final concentration was 100 μM. Reasonable signal-to-noise at a sample concentration of 200 μM is shown in Fig. 4.

For continuous monitoring of 3-diphosphocytidyl-glycerol formation using 1H–31P HSQC, glycerol-3-phosphate (3 mM) was reacted in the presence of 750 μM CTP and 1 mg mL−1 BSA in a total reaction volume of 300 μL. The reaction was initiated as described above.

Enzymatic synthesis of 5-diphosphocytidyl-D-ribose via the action of IspD

The enzyme reaction to form 5-diphosphocytidyl-D-ribose was carried out as described for the formation of 3-diphosphocytidyl- glycerol using 500 μM CTP. About 65% conversion to a new product peak by HPLC was observed within 5 h. HPLC analysis indicated a 65:35 product–CTP mixture with a final product concentration of 325 μM at the time of H,P-NMR analysis.

NMR sample preparation

NMR experiments were carried out on 300–600 μL of enzyme reaction mixture containing 10% v/v D2O in buffered solution (described above). Each reaction mixture containing 200 μM–5 mM substrate or product was subjected to NMR analysis following incubation with the appropriate enzyme as described above. Initial characterization of cMEDP was carried out on the purified compound.15 In all other cases, NMR data were collected on crude enzyme mixtures and did not require purification. No precautions were taken to remove contaminating paramagnetic Ni2+.

NMR experiments and analysis

Pulse-sequences for 1H–31P HSQC, 1H–31P–31P COSY experiments and their constant-time (CT) versions are shown in the ESI‡ (Fig. S2), and the experiments are described below. 1H–31P HSQC spectra consist of cross-peaks (referred to as “auto” peaks in this work) between 1H and 31P nuclei correlated by an nJHP coupling constant, n being the number of intervening covalent bonds. The auto peak intensity was optimized by the 1H → 31P magnetization transfer delay, thp, typically around 40 ms, based on geometry dependent variations of the JHP coupling constant. In specific cases, thp values as short as 5 ms and as long as 150 ms were observed.

In HSQC spectra acquired with high resolution in the 31P dimension, diphosphate resonances are split into doublets due to the 2JPP coupling constant (~20–25 Hz for all compounds studied here). In constant-time (CT) HSQC experiments, the 31P–31P doublets collapse into singlets, resulting in “homo-decoupled” spectra. When the constant time period delay (TC) is set to 1/JPP (40 to 50 ms), mono- and diphosphate auto peaks exhibit opposite phases, which may be used to distinguish between these species rapidly.

1H–31PA–31PB COSY spectra consist of additional 31PA→31PB magnetization transfer steps, leading to the observation of 31P–31P “cosy” peaks in diphosphate species. The phase of the cosy peak is opposite to that of the auto peak and its intensity is based on the magnetization transfer delay TPP. In all data presented here, optimal spectra were obtained by adjusting TPP to 1/(2 × JPP) (20 to 25 ms) resulting in a fully phase inverted spectrum consisting of only the HA:PB cosy peak. Constant-time (CT) H–P–P spectra with TC = 1/JPP yield homo-decoupled spectra analogous to CT-HSQC experiments with phase characteristics as described above. A superposition or comparison of HSQC and 1H–31P–31P spectra provides the complete HA–PA–PB–HB connectivity for the diphosphate linkage. All data were acquired as CT 1H–31P–31P spectra. All spectra in this study were acquired as CT-HSQC (TC=1/JPP) and CT-HPP (TPP=1/(2 × JPP)).

Data acquisition parameters for the two-dimensional spectra presented in this work are presented in the ESI‡ (Tables S1–S3). Wherever possible, 2D spectra were folded in the 31P dimension in order to obtain high-resolution data sets in a minimum interval of time. Data acquisition times were typically 20–30 min for CT-HSQC and CT 1H–31P–31P COSY spectra and ~1 h for high-resolution HSQC and 1H–31P–31P COSY spectra. Spectra were referenced w.r.t. TSP in the 1H dimension and external TPPO in the 31P dimension.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the gift of purified cMEDP provided by Professor Robert Coates from the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. We thank Leighanne Brammer for generating a CDP-ME sample used for constant-time experiments. We thank James Stivers, Philip Cole and Albert Mildvan for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by funding from the NIH (T32 CA009243 for M.S. and Johns Hopkins Malaria Research Institute Pilot Grant for J.K.B. and M.H.L.).

Footnotes

This article is part of the 2009 Molecular BioSystems ‘Emerging Investigators’ issue: highlighting the work of outstanding young scientists at the chemical- and systems-biology interfaces.

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available: Includes synthesis of MEP and EP, HPLC analysis of enzyme reactions, description of pulse sequences used, H-C-P COSY analysis of CDP-ME2P, data acquisition parameters. See DOI: 10.1039/b903513c

Abbreviations: ADP, adenine diphosphate; ATP, adenine triphosphate; CDP-E, 4-diphosphocytidyl-D-erythritol; CDP-E2P, 4-diphosphocytidyl- D-erythritol-2-phosphate; CDP-ME, 4-diphosphocytidyl-D-2C-methylerythritol; CDP-ME2P, 4-diphosphocytidyl-D-2C-methylerythritol-2- phosphate; cEDP, D-ethylerythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate; cMEDP, D-2C-methylerythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate; CMP, cytidine monophosphate; COSY, correlation spectroscopy; CT, constant time; CTP, cytidine triphosphate; DMAPP, dimethylallyl pyrophosphate; EP, D-erythritol 4-phosphate; HSQC, heteronuclear single quantum coherence; IPP, isopentenyl pyrophosphate; MEP, D-2C-methylerythritol phosphate; thp, magnetization transfer delay; TPPO, triphenylphosphine oxide; TSP, trimethylsilyl-2,2,3,3-tetradeuteropropionic acid.

Contributor Information

Ananya Majumdar, Email: ananya@jhu.edu.

Caren L. Freel Meyers, Email: cmeyers@jhmi.edu.

References

- 1.Eisenreich W, Bacher A, Arigoni D, Rohdich F. Biosynthesis of isoprenoids via the non-mevalonate pathway. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2004;61(12):1401–1426. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-3381-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodriguez-Concepcion M, Boronat A. Elucidation of the methylerythritol phosphate pathway for isoprenoid biosynthesis in bacteria and plastids. A metabolic milestone achieved through genomics. Plant Physiol. 2002;130(3):1079–1089. doi: 10.1104/pp.007138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rohdich F, Bacher A, Eisenreich W. Isoprenoid biosynthetic pathways as anti-infective drug targets. Biochem Soc Trans. 2005;33(Pt 4):785–791. doi: 10.1042/BST0330785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herz S, Wungsintaweekul J, Schuhr CA, Hecht S, Luttgen H, Sagner S, Fellermeier M, Eisenreich W, Zenk MH, Bacher A, Rohdich F. Biosynthesis of terpenoids: YgbB protein converts 4-diphosphocytidyl-2C-methyl-D-erythritol 2-phosphate to 2C-methyl-D-erythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(6):2486–2490. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040554697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luttgen H, Rohdich F, Herz S, Wungsintaweekul J, Hecht S, Schuhr CA, Fellermeier M, Sagner S, Zenk MH, Bacher A, Eisenreich W. Biosynthesis of terpenoids: YchB protein of Escherichia coli phosphorylates the 2-hydroxy group of 4-diphosphocytidyl- 2C-methyl-D-erythritol. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(3):1062–1067. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rohdich F, Wungsintaweekul J, Fellermeier M, Sagner S, Herz S, Kis K, Eisenreich W, Bacher A, Zenk MH. Cytidine 5′-triphosphate-dependent biosynthesis of isoprenoids: YgbP protein of Escherichia coli catalyzes the formation of 4-diphosphocytidyl-2-C-methylerythritol. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(21):11758–11763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.11758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Albaret C, Loeillet D, Auge P, Pierre-Louis F. Application of two-dimensional 1H–31P inverse NMR spectroscopy to the detection of trace amounts of organophosphorus compounds related to the chemical weapons convention. Anal Chem. 1997;69:2694–2700. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohn M, Hughes TR., Jr Phosphorus magnetic resonance spectra of adenosine di- and triphosphate. I. Effect of pH. J Biol Chem. 1960;235:3250–3253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garnier M, Dufourc EJ, Larijani B. Characterisation of lipids in cell signalling and membrane dynamics by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy and mass spectrometry. Signal Transduction. 2006;6:133–143. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gradwell MJ, Fan TW, Lane AN. Analysis of phosphorylated metabolites in crayfish extracts by two-dimensional 1H-31P NMR heteronuclear total correlation spectroscopy (heteroTOCSY) Anal Biochem. 1998;263(2):139–149. doi: 10.1006/abio.1998.2789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Larijani B, Poccia DL, Dickinson LC. Phospholipid identification and quantification of membrane vesicle subfractions by 31P-1H two-dimensional nuclear magnetic resonance. Lipids. 2000;35(11):1289–1297. doi: 10.1007/s11745-000-0645-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ojha RP, Dhingra MM, Sarma MH, Shibata M, Farrar M, Turner CJ, Sarma RH. DNA bending and sequence-dependent backbone conformation NMR and computer experiments. Eur J Biochem. 1999;265(1):35–53. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rastogi VK. 31P-1H correlation and resonance assignments along the DNA backbone: three-dimensional implementation of heteronuclear long-range correlation experiment. Magn Reson Chem. 2000;38:288–292. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teleman A, Richard P, Toivari M, Penttila M. Identification and quantitation of phosphorus metabolites in yeast neutral pH extracts by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Anal Biochem. 1999;272(1):71–79. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Urbansky M, Davis CE, Surjan JD, Coates RM. Synthesis of enantiopure 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate and 2,4-cyclodiphosphate from D-arabitol. Org Lett. 2004;6(1):135–138. doi: 10.1021/ol0362562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cavanagh J, Fairbrother WJ, Palmer AG, III, Skelton NJ. Protein NMR Spectroscopy: Principles and Practice. Academic Press; San Diego: 1996. pp. 468–473. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Santoro J, King GC. A constant-time 2D Overbodenhausen experiment for inverse correlation of isotopically enriched species. J Magn Reson. 1992;97:202–207. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vuister GW, Bax A. Resolution enhancement and spectral editing of uniformly carbon-13-enriched proteins by homonuclear broadband carbon-13 decoupling. J Magn Reson. 1992;98:428–435. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Illarionova V, Kaiser J, Ostrozhenkova E, Bacher A, Fischer M, Eisenreich W, Rohdich F. Nonmevalonate terpene biosynthesis enzymes as antiinfective drug targets: substrate synthesis and high-throughput screening methods. J Org Chem. 2006;71(23):8824–8834. doi: 10.1021/jo061466o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lillo AM, Tetzlaff CN, Sangari FJ, Cane DE. Functional expression and characterization of EryA, the erythritol kinase of Brucella abortus, and enzymatic synthesis of L-erythritol-4-phosphate. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2003;13(4):737–739. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(02)01032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richard SB, Bowman ME, Kwiatkowski W, Kang I, Chow C, Lillo AM, Cane DE, Noel JP. Structure of 4-diphosphocytidyl-2-C-methylerythritol synthetase involved in mevalonate-independent isoprenoid biosynthesis. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8(7):641–648. doi: 10.1038/89691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richard SB, Lillo AM, Tetzlaff CN, Bowman ME, Noel JP, Cane DE. Kinetic analysis of Escherichia coli 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol-4-phosphate cytidyltransferase, wild type and mutants, reveals roles of active site amino acids. Biochemistry. 2004;43(38):12189–12197. doi: 10.1021/bi0487241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6(3):277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.