Abstract

Elucidating the properties of the heme Fe-CuB binuclear center and the dynamics of the protein response in cytochrome c oxidase is crucial to understanding not only the dioxygen activation and bond cleavage by the enzyme but also the events related to the release of the produced water molecules. The time-resolved step-scan FTIR difference spectra show the ν7a(CO) of the protonated form of Tyr residues at 1247 cm−1 and that of the deprotonated form at 1301 cm−1. By monitoring the intensity changes of the 1247 and 1301 cm−1 modes as a function of pH, we measured a pKa of 7.8 for the observed tyrosine. The FTIR spectral changes associated with the tyrosine do not belong to Tyr-237 but are attributed to the highly conserved in heme-copper oxidases Tyr-136 and/or Tyr-133 residue (Koutsoupakis, K., Stavrakis, S., Pinakoulaki, E., Soulimane, T., and Varotsis, C. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 32860–32866). The oxygenation of CO by the mixed-valence form of the enzyme revealed the formation of the ∼607 nm P (Fe(IV)=O) species in the pH 6–9 range and the return to the oxidized form without the formation of the 580 nm F form. The data indicate that Tyr-237 is not involved in the proton transfer pathway in the oxygenation of CO by the mixed-valence form of the enzyme. The implication of these results with respect to the role of Tyr-136 and Tyr-133 in proton transfer/gating along with heme a3 ring D propionate-H2O-ring A propionate-Asp-372 site to the exit/output proton channel (H2O pool) is discussed.

Keywords: Bioenergetics, Biophysics, Cytochrome Oxidase, Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR), Metalloenzymes, Protein Structure, Time-resolved Fourier Transform Infrared

Introduction

Cytochrome ba3 oxidase is a member of the heme-copper oxidase family and, in addition to activating O2 and conserving the energy of O2 reduction for subsequent ATP synthesis, is able to catalyze the reduction of NO to N2O under reducing anaerobic conditions (1–5). The crystal structure of the protein indicates that subunit I consists of a low-spin heme b and a high-spin heme a3-CuB binuclear center where the dioxygen and nitric oxide reactions take place (1). Two proton pathways have been identified in ba3 oxidase and correspond to the putative so-called K and D pathways found in Paracoccus denitrificans and bovine oxidase despite the fact that most of the residues belonging to these pathways are not conserved (1). Glu-278 (residue of P. denitrificans), which is highly conserved in heme-copper oxidases and is involved in redox-induced proton transfer reactions, is replaced by Ile in ba3 oxidase (1, 6, 7). The highly conserved, covalently ring-linked His-Tyr species that has been determined by the crystal structures of bovine, P. denitrificans, and Thermus thermophilus heme-copper oxidases and by protein chemical analysis is a unique peptide (1, 6, 7). It is located in the immediate vicinity of the binuclear center, within hydrogen-bonding distance of heme a3-ligated O2, and is capable of modulating the redox potential and the pKa of Tyr-O-His as occurs for the redox-active, covalently cross-linked tyrosine residue in galactose oxidase (8). On the basis of the crystal structure of the bovine enzyme, Yoshikawa et al. (6) proposed a proton transfer mechanism from this tyrosine to ferric peroxide to generate a hydroperoxo adduct. Recently, the reaction of ba3 oxidase with O2 was investigated by time-resolved optical spectroscopy, and the results indicated the formation of oxygenated intermediate species (9). The molecular mechanisms of the ba3 oxidase are expected to be similar to those of other distantly related heme-copper oxidases with respect to the oxygen chemistry and the oxygenation of CO to form the 607 nm P intermediate ferryl-oxo species (6–11). The latter reaction was first reported in the oxygen-dependent oxidation of carbon monoxide in mammalian tissue (12). Mammalian cytochrome c oxidase was demonstrated to catalyze the monooxygenation of CO to CO2 when reductively activated in the presence of oxygen (13).

In the O2 cycle of oxidases, it has been suggested that the O–O bond cleavage proceeds by concerted hydrogen atom transfer from the cross-linked His-Tyr species to produce the Fe(IV)=O/Cu(II)B-H-Y· species (14). This raises important issues as to the means by which the electron transfer to these transient species is regulated for conformational transitions that are required for any pumping mechanism to occur (6, 7, 9, 10). In the oxidase/peroxide reaction at high pH, it has been demonstrated that the addition of stoichiometric amounts of H2O2 to oxidized enzyme leads to the formation of the 607 nm form having the proposed Fe(IV)=O … HO-Cu(II)B-His-Tyr• structure (15). Furthermore, single protonation of the former species results in the formation of the 580 nm form with a proposed Fe(IV)=O Cu(II)B-His-Tyr• structure (15). However, no definite spectroscopic evidence has yet been observed for the formation of Tyr• in the binuclear center of heme-copper oxidases. It has been suggested that the additional electron needed to produce the 607 nm P (Fe(IV)=O) species is provided by Tyr-167 or Trp-272 (P. denitrificans sequence), which are near the binuclear heme Fe-CuB center and highly conserved in heme-copper oxidases (Tyr-136 and Trp-229 in T. thermophilus) (16, 17). Determining the properties of the residue(s) responsible for the formation of the 607 nm P (Fe(IV)=O) species will resolve controversial aspects of the oxygen activation and O–O cleavage mechanisms.

FTIR spectroscopy has proven to be a very powerful technique in studying changes at the level of individual amino acids during protein action (18, 19). FTIR studies of a His-Tyr-OH model compound, 2-imidazol-1-yl-4-methylphenol, have demonstrated that the ν7a(CO) and δ(COH) modes in the deprotonated form of His-Tyr-O− shift from 1268 cm−1 (protonated) to 1301 cm−1 (18). In addition, the oxidized-minus-reduced FTIR spectra of aa3 oxidase from P. denitrificans showed signals at 1270 cm−1 that were attributed to ν7a(CO) and δ(COH) of a protonated tyrosine (18). The observed reduced intensity of these signals in the Y280H mutant allowed Hellwig et al. (18) to assign this mode to ν7a(CO) and δ(COH) of the protonated cross-linked Tyr-237 residue (Tyr-280 in P. denitrificans). With the purpose of identifying His-Tyr-OH modes in cytochrome bo3 oxidase, Woodruff and co-workers (19) applied low-temperature FTIR difference spectroscopy to the enzyme and FTIR spectroscopy to the His-Tyr-OH model compound. They detected the fundamental His Nϵ-Cϵ Tyr mode and its combination at 1549 and 3033 cm−1, respectively (19).

In addition to the dioxygen activation and reduction and the oxygenation of CO mechanisms, it is crucial to determine the intermediate protein structures subsequent to ligand binding/release and discrimination (20). Extensive time-resolved step-scan FTIR (TRS2-FTIR)2 studies of ba3 oxidase-CO have revealed the dynamics of the binuclear center and showed protein conformational changes near the heme a3 propionates (4, 5, 21, 22). In addition, the ligand delivery channel at the CuB site and the presence of a docking site near the heme a3 propionates were identified (21, 22). Cytochrome ba3 has preexisting cavities that are only modestly perturbed by the photodissociated CO from heme a3, and previous work revealed such a docking site that is responsible for the kinetic control of both ligand motion/binding and escape (21). Those results, in conjunction with the reported protonic connectivity between the propionates of heme a3, Asp-372, and H2O, led to the identification of a proton exit channel (22). A pathway connecting the docking and binding sites was presented to explain how this pathway may lead to the escape of translocated protons and catalytically formed H2O molecules. Of note, both protonated and deprotonated forms of the ring A of heme a3 were detected in the TRS2-FTIR data (22).

The identification of ionizable groups whose pKa values are near physiological pH is extremely useful because the conformational transition that is associated with such protonation/deprotonation events is crucial in our understanding of the proton motion in heme-copper oxidases. TRS2-FTIR spectroscopy has been applied to the carbonmonoxy derivatives of heme-copper oxidases to probe the protein dynamics subsequent to CO photolysis (22). The TRS2-FTIR spectra are the result of the perturbation induced by the photodissociation of CO from the heme iron and its subsequent binding to CuB to structures near heme iron and CuB. In the work presented here, we continued our TRS2-FTIR approach with heme-copper oxidases at room temperature, and in conjunction with the assignment of ν7a(CO) and δ(COH) in the aa3-type oxidase from P. denitrificans, we detected the protonated and deprotonated forms of tyrosine residue(s) near the induced perturbation, i.e. the heme a3-CuB binuclear center of cytochrome ba3 from T. thermophilus (4, 5, 17, 18, 23, 24). Our TRS2-FTIR difference spectra show that ν7a(CO) and δ(COH) in the protonated form of Tyr are located at 1247 cm−1 and in the deprotonated form at 1301 cm−1. By monitoring the intensity changes of the 1247 and 1301 cm−1 modes as a function of pH, we measured a pKa of 7.8 for the observed Tyr residue. On the basis of the tentative assignments of the 1247 and 1301 cm−1 modes, the data indicate that Tyr-133 and/or Tyr-136 (both of which are located near the binuclear center) serves as a proton gating/transfer ionizable group. Mixed-valence ba3 oxidase is a two-electron reduced form of the enzyme (heme a32+-CuB1+) that carries out O2 reduction only to the controversial peroxy oxidation level. Upon direct mixing of O2 with the mixed-valence CO-bound enzyme (MV-CO) under alkaline and acidic conditions, the ∼607 nm P (Fe(IV)=O) species is formed. This intermediate is linked to the proton pump function of heme-copper oxidases (6, 7, 15). Our data obtained under both acidic and alkaline conditions do not favor the cross-linked Tyr-237 residue (whose protonation state is not altered between pH/pD 5.5 and 9.7), as the residue associated with the FTIR spectral changes, but other tyrosine residues with labile protons. We postulate that Tyr-133 and/or Tyr-136 (both of which are the only Tyr residues with labile protons near the vicinity of the heme Fe-CuB binuclear center) plays a role in either the dioxygen chemistry or proton gating during the enzymatic reactions.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cytochrome ba3 was isolated from T. thermophilus HB8 cells according to previously published procedures (2). The samples used for the FTIR measurements had an enzyme concentration of ∼1 mm and were placed in the desired buffer (pH 5.5–6.5, MES; pH 7.5, HEPES; or pH 8.5–9.5, CHES). Dithionite-reduced samples were exposed to 1 atm CO (1 mm) in an anaerobic cell to prepare the carbonmonoxy adduct and transferred to a tightly sealed FTIR cell under anaerobic conditions (l = 15 μm). CO gas was obtained from Messer. The 532-nm pulse from a Continuum Nd:YAG laser (7-ns width, 3 Hz) was used as a pump light (4 mJ/pulse) to photolyze the ba3-CO oxidase. FTIR measurements were performed on a Bruker Equinox IFS 55 spectrometer equipped with the step-scan option. For the time-resolved experiments, a TTL (transistor-transistor logic) pulse provided by a digital delay pulse generator (Quantum Composers 9314T) triggers, in order, the flashlamps, Q-switch, and FTIR spectrometer. Pretriggering the FTIR spectrometer to begin data collection before the laser fires allows 11 fixed reference points to be collected at each mirror position, which are used as the reference spectrum in the calculation of the difference spectra. Changes in intensity were recorded with an MCT (mercury-cadmium-telluride) detector (Graseby Infra-Red D316, response limit of 600 cm−1) amplified in the DC-coupled mode and digitized with a 200-kHz 16-bit analog-to-digital converter. A broadband interference optical filter (Optical Coating Laboratory, Santa Rosa, CA) with a short wavelength cutoff at 2.67 μm was used to limit the free spectral range from 2.67 to 8 μm. This leads to a spectral range of 3949.5 cm−1, which is equal to an undersampling ratio of 4. Single-sided spectra were collected at 8 cm−1 spectral resolution, 5-μs time resolution, and 10 co-additions per data point. The total accumulation time for each measurement was 62 min, and two to three measurements were collected and averaged. A Blackman-Harris three-term apodization function with 32 cm−1 phase resolution and the Mertz phase correction algorithm were used. Difference spectra were calculated by substracting the reference spectrum, recorded before the laser firing, from those after the photodissociation of CO from heme a3.

The MV-CO enzyme was prepared by exposing an anaerobic solution of the resting enzyme to CO for 10 h at 20 °C. The 610 nm species was obtained by introducing O2 to the MV-CO enzyme. Optical absorption spectra were recorded with a Perkin-Elmer Lambda UV-visible spectrometer before and after the FTIR measurements to ensure the formation and stability of the CO adducts.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

pKa of the Tyrosine Residue

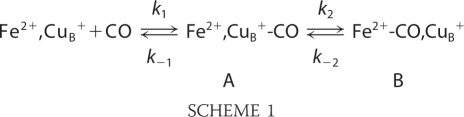

Intensity changes and frequency shifts of side chains and backbone structures have been observed in the FTIR difference spectra of heme-copper oxidases as the result of an electrochemical perturbation (oxidized minus reduced) of the metal centers at room temperature or of the perturbation induced by the photodissociation of CO bound to the heme at 80 K, at which the CO binds irreversibly to CuB (18, 19, 23, 24). In the latter case, the perturbation induced by the photodissociated CO exerts its main effect on the environment of the binuclear center. The kinetics data on the photodissociation of CO and its rebinding to heme a3 have shown that the CO ligation/release mechanism in cytochrome ba3 follows that found in other heme-copper oxidases and proceeds according to Scheme 1.

|

In contrast to the bovine aa3 oxidase, CuB of cytochrome ba3 has a relatively high affinity for CO (K1 > 104), whereas the transfer of CO to heme a32+ is characterized by a small k2 = 8 s−1 and by k−2 = 0.8 s−1, which is 30-fold greater than that of bovine aa3 oxidase (25). Therefore, it is possible to take advantage of the long life-time of the CuB1+-CO complex and collect TRS2-FTIR difference spectra at room temperature, in which maximum conformational changes and possible proton transfer reactions can take place. It should be noted that small conformational changes of the protein are expected at low temperatures, and thus, it is unlikely that proton transfer reactions can take place. In our room temperature TRS2-FTIR difference spectra, the positive bands are associated with the CuB1+-CO state, and the negative bands are due the heme a3 Fe2+-CO state.

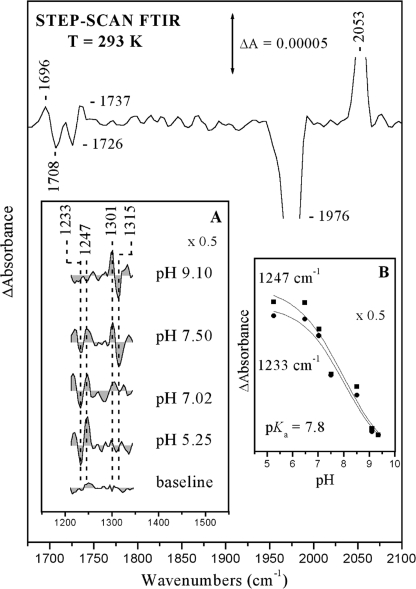

Fig. 1 shows the TRS2-FTIR difference spectrum (the co-averaged first 200 μs after photodissociation of CO) at pH 7.5. In this time scale, the photodissociated CO from the heme a3 iron (ν(CO) = 1976 cm−1) is bound to CuB (ν(CO) = 2053 cm−1). The data show that photodissociation of CO from heme a3 produces the same transient photoproduct as that obtained at pD 8.5 and without changes in the intensity ratio of the 1976/2053 cm−1 modes (4, 5). In addition, the C=O mode of the protonated heme a3 propionates is seen as a derivative shape feature with a trough/peak at 1708/1696 cm−1; the negative band located at 1726 cm−1 is the C=O stretch of Asp-372. ν7a(CO) and δ(COH) of the protonated and deprotonated forms of tyrosine residues are expected in the 1200–1300 cm−1 region (18). A close inspection of the data indicates that such features exist in the TRS2-FTIR difference spectrum (td = 0–200 μs) at pH 7.5 and appear as two pairs of peaks/troughs at 1247/1233 and 1301/1315 cm−1. The pH dependence of both pairs of the peaks/troughs is depicted in Fig. 1 (inset A). The TRS2-FTIR difference spectrum obtained at pH 9.1 indicates that the 1233/1247 cm−1 pair observed in the pH 5.5–7.5 range has vanished and that the 1301/1315 cm−1 pair has gained intensity relative to that observed at pH 7.5. On the basis of the similarity in the frequencies of the ν7a(CO) and δ(COH) modes in the model compound and in the aa3 oxidase from P. denitrificans, we assign the 1247 and 1301 cm−1 vibrations to the protonated and deprotonated forms of a tyrosine residue, respectively (18). The relative intensities (peak area) of the peak/trough pair at 1247/1233 cm−1 are shown in Fig. 1 (inset B) as a function of pH. An apparent pKa of 7.8 was calculated from the titration curve. The pKa value we have measured is in excellent agreement with that predicted at 7.6 from calculations but lower than that reported at 8.6 and 9.2 for the model compound 2-imidazol-1-yl-4-methylphenol (26–28). The model compound studies have also demonstrated that the linked imidazole group causes lowering of the pKa of the phenolic OH by 1.5 pKa units compared with that of the isolated p-cresol OH value (10.2). Although these studies did not include the influence of CuB on the phenol pKa, the observed lowering of pKa to 7.8 in the protein can be explained in terms of electron-withdrawing effects from CuB and therefore does not rule out the cross-linked Tyr-237 as being the residue responsible for the observed spectral changes (see below). The latter effect will be minimized due to dπ-pπ back-bonding and the weak coordination ability expected for His-233. The observed shift of the pKa value from 8.6 to 9.2 in the model to 7.8 in the enzyme indicates a rather extended delocalization/stabilization of the Tyr anion involving either the Tyr-His-CuB structure or another group able to accept the negative charge. In the best scenario, this group could be the heme a3 and not just Tyr-His or a similar dipeptide (29).

FIGURE 1.

TRS2-FTIR difference spectrum (1675–2100 cm−1 spectral region) of the CO-bound form of fully reduced cytochrome ba3 oxidase at pH 7.5 and 293 K. The spectrum is the average of 40 individual spectra from 0 to 200 μs. The spectral resolution was 8 cm−1, the time resolution was 5 μs, and 10 co-additions were collected per data point. The photolysis wavelength was 532 nm (4 mJ/pulse), and three measurements were recorded and averaged. Inset A, TRS2-FTIR difference spectra (1200–1350 cm−1 spectral region) of the ba3 oxidase-CO complex subsequent to CO photolysis at the indicated pH values. The experimental conditions were the same as described above. Inset B, plot of the 1247 cm−1 (■) and 1233 cm−1 (●) modes versus pH. ΔA values of the 1233 and 1247 cm−1 modes were measured from the peaks area, and the curves are three-parameter sigmoidal fits to the experimental data.

Protonation/Deprotonation State of Tyr Residues

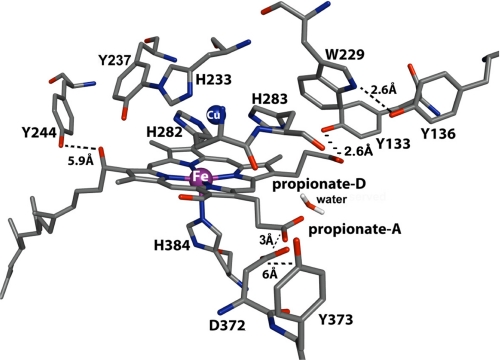

In an attempt to determine which tyrosine is responsible for the spectral changes shown in Fig. 1, we examined the available crystal structure of cytochrome ba3 (Protein Data Bank code 1EHK) (1). Subunit I contains 24 tyrosine residues, six of which are in a distance of <7 Å from the active center, whereas subunit II contains eight tyrosine residues and subunit IIa contains one, none of which are in close proximity to the heme Fe-CuB center. Fig. 3 shows the five tyrosine residues closest to the binuclear center of ba3 oxidase, which appear to be the most possible candidates for the transient protonation/deprotonation events described above.

FIGURE 3.

Representation of the binuclear center of cytochrome ba3 oxidase from T. thermophilus (Protein Data Bank code 1EHK). The five tyrosine residues nearest the heme a3-CuB center are also included. The figure was prepared with PyMOL (36).

Tyr-237 is cross-linked to His-233, one of the CuB ligands, and is the closest tyrosine residue to the heme a3 iron atom (5.63 Å). However, we do not favor Tyr-237 as the most possible candidate because its transient protonation/deprotonation would have a clear effect on the frequency of the transient CuB1+-CO complex (4). The frequency of the transient CuB1+-CO mode is at 2053 cm−1, the same as in the equilibrium complex, and remained unchanged in the pH/pD 5.5–9.7 range. It has been clearly demonstrated that a change in the protonation state of one of the CuB imidazole ligands has a significant effect on the back-donation of electron density and therefore the vibrational frequencies with a calculated shift of 20–43 cm−1, whereas deprotonation of the phenol unit strengthens the Cu–C bond and weakens the C–O bond, leading to a frequency shift of 11 cm−1 (30). On the basis of the experimental and theoretical studies, we concluded that the protonation state of Tyr-237 remains unchanged. Tyr-244 is ∼7 Å from the heme OH group and CuB ligand His-283, respectively. Although Tyr-244 has been proposed to participate in one of the proton translocation channels, its position relative to the binuclear center does not support its involvement in the protonation/deprotonation events because, as shown in previous work, the effect of the CO photolysis is focused mainly in the region between heme a3 iron, CuB, and heme propionates (4). Of the three remaining tyrosine residues, Tyr-373 is almost 7 Å from the COO group of Asp-372, a residue shown to be in hydrogen-bonding distance with the ring A heme a3 propionate. Although the heme propionate-Asp-372 moiety is strongly involved in the CO photolysis event, the relatively long distance of Tyr-373 from the heme propionate (∼10 Å) minimizes its possibility as a candidate for the observed changes we observed (4).

The last two tyrosine residues near the binuclear center are Tyr-133, whose hydroxyl oxygen atom is 2.67 Å from the ring D heme a3 propionate, and Tyr-136, which is hydrogen-bonded to Trp-229 and proposed to be involved in a direct CuA-to-CuB electron transfer process (1). Trp-229 and Tyr-136 are near CuB and have been proposed to be involved in the formation of the 607 nm P (Fe(IV)=O) species in P. denitrificans (16, 17). For Tyr-133, the distance between the hydroxyl oxygen atom and the ring D heme a3 propionate means that Tyr-133 and the COO propionate group are strongly hydrogen-bonded, and also, this tyrosine residue appears in a site proved to play significant role in the events after CO photolysis (4, 21, 22). In previous work, we showed that CO photolysis triggers conformational changes in the ring A heme a3 propionate-Asp-372 moiety, which is also strongly hydrogen-bonded (21). We also showed that, upon dissociation, the photolyzed CO becomes trapped within a ligand-docking site located in the same region above heme a3 (21). In this work, we present evidence for transient deprotonation of tyrosine residue(s), and we propose that Tyr-133, which is in hydrogen-bonding distance with the ring D heme a3 propionate, forms an analogous bond with the ring A heme a3 propionate-Asp-372 moiety and/or Tyr-136, which is near the CuB unit. These two tyrosine residues are likely to be subjected to the same conformational changes after CO photolysis and may serve as the entry/exit gate for the translocated protons during the catalytic function of the enzyme.

Formation of the 607 nm Ferryl-oxo Species

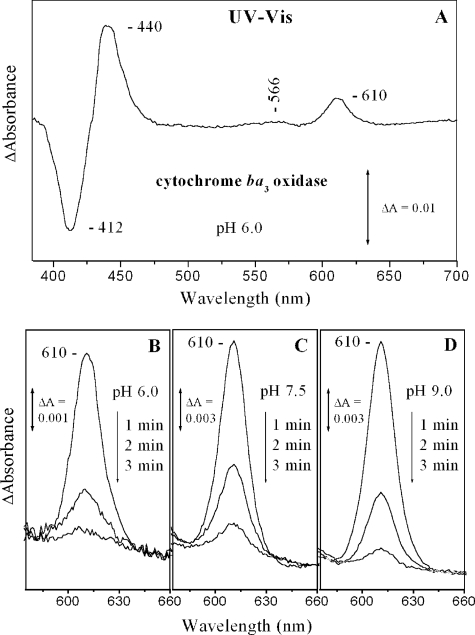

The ∼607 nm (Fe(IV)=O) species that is formed after the decay of the oxy intermediate in the MV/O2 reaction may be generated either by direct mixing of O2 with the MV-CO oxidase or by aerobic incubation of the enzyme with CO and O2 (11, 31–35). Both approaches produce the ∼607 nm species (P). We have applied the former procedure to both the wild-type and MV-Y280H aa3 oxidases from P. denitrificans and demonstrated that the ∼607 nm species can be formed in both the wild-type and Y280H enzymes (32). When O2 was introduced to the MV-CO ba3 enzyme at pH 6.0, the absorption difference spectrum (MV-CO/O2 minus oxidized) shown in Fig. 2A was obtained. The maxima observed at 440, 566, and 610 nm and the minimum at 412 nm are in agreement with those reported previously for aa3-type oxidases (31–33). Fig. 2 (B–D) shows the pH and time dependence of the 610 nm form at pH 6.0, 7.5, and 9. The 610 nm species was more populated above pH 7.5 (Fig. 2, C and D) and decayed faster as the pH was lowered (Fig. 2B). It should be noted that the formation of the 610 nm species persisted up to pH 12 (data not shown). The data indicate that O2 spontaneously replaces CO, and the decay of the 610 nm species to the pulsed and subsequently to the resting form occurs on a time scale of tens of seconds, in agreement with previous results on the aa3-type heme-copper oxidases (32, 33). For the sake of comparison with earlier work, in the following discussion, we ascribe the 610 nm species we detected in the MV/O2 cytochrome ba3 reaction to the species referred to in the literature as having 607 nm absorbance.

FIGURE 2.

Optical absorption difference spectra of the CO-MV cytochrome ba3/O2 reaction minus the resting form of the enzyme at 1, 2, and 3 min subsequent to mixing at pH 6.0 (A and B), pH 7.5 (C), and pH 9.0 (D). The concentration of the enzyme was 10 μm, and the path length of the cell was 1 cm.

It has been proposed that the formation of the 607 nm species (P) is accompanied by the generation of a CuB-His-Tyr• species, which is the result of a concerted hydrogen atom abstraction from Tyr by the iron-bound oxygen atom to promote O–O bond cleavage and formation of the P ferryl-oxo (Fe(IV)=O) species with a characteristic frequency at 804 cm−1 (14). Most recently, the 607 nm and 804 cm−1 ferryl-oxo species were detected at alkaline conditions (11). Tryptophan and tyrosine radicals have been also observed in the aa3/H2O2 reaction forming the 607 nm species, and an analogous species has been observed in both the Y280H/H2O2 and MV-Y280H-CO/O2 reactions (16, 17, 34). The data presented in Figs. 2 and 3 demonstrate that the 607 nm species (P) persists under alkaline conditions in the oxygenation reaction of the ba3 oxidase-CO complex, in which the observed tyrosine(s) are deprotonated. If the pKa of Tyr-237 is modulated by the ligand binding to heme a3 (CO versus O2), then we cannot exclude the possibility that Tyr-237 is the source of the third electron to produce the 607 nm species.

Combining the above results with the earlier optical and time-resolved resonance Raman results and with those reported recently on the formation of the 607 nm species in the MV/O2 reaction (11, 31–35), the following points emerge. It has been conclusively demonstrated by this work that the incubation of oxidized ba3 with CO forms the MV species, which reacts with O2 to generate the P intermediate appearing in the physiological reaction of all heme-copper oxidase, but it does not yield the F intermediate (580 nm species). The rate of decay of the 607 nm species is faster under acidic conditions, indicating that, when Tyr-136/Tyr-133 is protonated, the ferryl-oxo species decays faster to the pulsed and subsequently to the resting form of the enzyme. Under alkaline conditions, Tyr-136/Tyr-133 is deprotonated, and O2 binding to heme a3 is followed by oxidation of an amino acid residue. In the latter case, the O–O scission occurs by electron transfer, forming only one highly oxidizing species (607 nm species). The slow rate of decay of the 607 nm species under alkaline conditions indicates that the protonation state of Tyr-136/Tyr-133 is coupled to its decay to the pulsed/oxidized form. We propose that uptake of a proton from the bulk solution is accompanied by the protonation of Tyr-136 and/or Tyr-133. In this way, protons are transferred to the ring D propionate-H2O-ring A propionate-Asp-372 site. All residues involved in the proposed proton transfer mechanism are highly conserved among the structurally known heme-copper oxidases and form functionally operating residues that are part of an exit/output proton channel. The sequential or concerted hydrogen-bonded connectivity between the operating residues has an activation for proton motion. The exchangeable protons play a vital role in the biological function of the enzyme, and the first step in locating protein (in this case, tyrosine(s)) residues near the binuclear center as possible sites for proton motion has been demonstrated in this work. The data presented here, coupled with those reported recently by Chang et al. (37), who demonstrated that ba3 oxidase utilizes only one proton input channel analogous to the A-family K-channel, support the idea that a common active structure is responsible for the function of cytochrome oxidase. The labile protons could be either redox-linked or perturbed by ligand motion, including H2O molecules. Experiments are in progress to answer these questions.

This work was supported by research funds from the Cyprus University of Technology (to C. V.) and the Science Foundation Ireland Grant BICF865 (to T. S.).

- TRS2-FTIR

- time-resolved step-scan FTIR

- MV-CO

- mixed-valence CO-bound

- CHES

- 2-(cyclohexylamino)ethanesulfonic acid.

REFERENCES

- 1. Soulimane T., Buse G., Bourenkov G. P., Bartunik H. D., Huber R., Than M. E. (2000) EMBO J. 19, 1766–1776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Buse G., Soulimane T., Dewor M., Meyer H. E., Blüggel M. (1999) Protein Sci. 8, 985–990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Giuffrè A., Stubauer G., Sarti P., Brunori M., Zumft W. G., Buse G., Soulimane T. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 14718–14723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Koutsoupakis K., Stavrakis S., Pinakoulaki E., Soulimane T., Varotsis C. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 32860–32866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Koutsoupakis K., Stavrakis S., Soulimane T., Varotsis C. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 14893–14896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yoshikawa S., Shinzawa-Itoh K., Nakashima R., Yaono R., Yamashita E., Inoue N., Yao M., Fei M. J., Libeu C. P., Mizushima T., Yamaguchi H., Tomizaki T., Tsukihara T. (1998) Science 280, 1723–1729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Iwata S., Ostermeier C., Ludwig B., Michel H. (1995) Nature 376, 660–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Klinman J. P. (1996) Chem. Rev. 96, 2541–2562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Smirnova I. A., Zaslavsky D., Fee J. A., Gennis R. B., Brzezinski P. (2008) J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 40, 281–287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Szundi I., Funatogawa C., Fee J. A., Soulimane T., Einarsdóttir O. (2010) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 21010–21015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kim Y., Shinzawa-Itoh K., Yoshikawa S., Kitagawa T. (2001) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 757–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fern W. O. (1932) Am. J. Physiol. 102, 379–392 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Young L. J., Caughey W. S. (1986) Biochemistry 25, 152–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Proshlyakov D. A., Pressler M. A., Babcock G. T. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 8020–8025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Michel H. (1999) Biochemistry 38, 15129–15140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Budiman K., Kannt A., Lyubenova S., Richter O. M., Ludwig B., Michel H., MacMillan F. (2004) Biochemistry 43, 11709–11716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wiertz F. G., Richter O. M., Cherepanov A. V., MacMillan F., Ludwig B., de Vries S. (2004) FEBS Lett. 575, 127–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hellwig P., Pfitzner U., Behr J., Rost B., Pesavento R. P., Donk W. V., Gennis R. B., Michel H., Ludwig B., Mäntele W. (2002) Biochemistry 41, 9116–9125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tomson F., Bailey J. A., Gennis R. B., Unkefer C. J., Li Z., Silks L. A., Martinez R. A., Donohoe R. J., Dyer R. B., Woodruff W. H. (2002) Biochemistry 41, 14383–14390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Luna V. M., Chen Y., Fee J. A., Stout C. D. (2008) Biochemistry 47, 4657–4665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Koutsoupakis C., Soulimane T., Varotsis C. (2003) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 14728–14732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Koutsoupakis C., Soulimane T., Varotsis C. (2004) Biophys. J. 86, 2438–2444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stavrakis S., Koutsoupakis K., Pinakoulaki E., Urbani A., Saraste M., Varotsis C. (2002) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 3814–3815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pinakoulaki E., Soulimane T., Varotsis C. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 32867–32874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Woodruff W. H. (1993) J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 25, 177–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kannt A., Lancaster C. R., Michel H. (1998) Biophys. J. 74, 708–721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McCauley K. M., Vrtis J. M., Dupont J., van der Donk W. A. (2000) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 2403–2404 [Google Scholar]

- 28. Aki M., Ogura T., Naruta Y., Le T. H., Sato T., Kitagawa T. (2002) J. Phys. Chem. A 106, 3436–3444 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cappuccio J. A., Ayala I., Elliott G. I., Szundi I., Lewis J., Konopelski J. P., Barry B. A, Einarsdóttir O. (2002) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 1750–1760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Daskalakis V., Pinakoulaki E., Stavrakis S., Varotsis C. (2007) J. Phys. Chem. B 111, 10502–10509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Morgan J. E., Verkhovsky M. I., Palmer G., Wikström M. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 6882–6892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pinakoulaki E., Pfitzner U., Ludwig B., Varotsis C. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 13563–13568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Han S., Ching Y. C., Rousseau D. L. (1990) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 112, 9445–9451 [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pinakoulaki E., Pfitzner U., Ludwig B., Varotsis C. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 18761–18766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Varotsis C., Woodruff W. H., Babcock G. T. (1990) J. Biol. Chem. 265, 11131–11136 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Delano W. L. (2010) The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.3, Schrödinger, LLC, New York [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chang H. Y., Hemp J., Chen Y., Fee J. A., Gennis R. B. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 16169–16173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]