Abstract

Objective To evaluate the association of chocolate consumption with the risk of developing cardiometabolic disorders.

Design Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials and observational studies.

Data sources Medline, Embase, Cochrane Library, PubMed, CINAHL, IPA, Web of Science, Scopus, Pascal, reference lists of relevant studies to October 2010, and email contact with authors.

Study selection Randomised trials and cohort, case-control, and cross sectional studies carried out in human adults, in which the association between chocolate consumption and the risk of outcomes related to cardiometabolic disorders were reported.

Data extraction Data were extracted by two independent investigators, and a consensus was reached with the involvement of a third. The primary outcome was cardiometabolic disorders, including cardiovascular disease (coronary heart disease and stroke), diabetes, and metabolic syndrome. A meta-analysis assessed the risk of developing cardiometabolic disorders by comparing the highest and lowest level of chocolate consumption.

Results From 4576 references seven studies met the inclusion criteria (including 114 009 participants). None of the studies was a randomised trial, six were cohort studies, and one a cross sectional study. Large variation was observed between these seven studies for measurement of chocolate consumption, methods, and outcomes evaluated. Five of the seven studies reported a beneficial association between higher levels of chocolate consumption and the risk of cardiometabolic disorders. The highest levels of chocolate consumption were associated with a 37% reduction in cardiovascular disease (relative risk 0.63 (95% confidence interval 0.44 to 0.90)) and a 29% reduction in stroke compared with the lowest levels.

Conclusions Based on observational evidence, levels of chocolate consumption seem to be associated with a substantial reduction in the risk of cardiometabolic disorders. Further experimental studies are required to confirm a potentially beneficial effect of chocolate consumption.

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization, by 2030 nearly 23.6 million people will die from cardiovascular disorders.1 2 Furthermore, about a fifth of the world’s adult population are thought to have metabolic syndrome, a cluster of factors associated with an increased risk of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.3 4 This increase in cardiometabolic disorders exerts a great burden on people, healthcare organisations, and society in general. However, cardiometabolic disorders are largely preventable, and a better understanding of the factors associated in their physiopathogenesis and implementation of interventions to modify these factors will be critical in tackling the current epidemic.

Diet is one of the key lifestyle factors involved in the genesis, prevention, and control of cardiometabolic disorders. Cocoa products containing flavonol have been shown to have an encouraging potential to help prevent cardiometabolic disorders.5 Recent studies (both experimental and observational) have suggested that chocolate consumption has a positive influence on human health, with antioxidant, antihypertensive, anti-inflammatory, anti-atherogenic, and anti-thrombotic effects as well as influence on insulin sensitivity, vascular endothelial function, and activation of nitric oxide.6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 These beneficial effects have been confirmed in recent reviews and meta-analyses, supporting the positive role of cacao and cocoa products on cardiovascular risk factors such as blood pressure, cholesterol levels, atherosclerosis, and insulin resistance.17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 However, most of the existing evidence is on intermediate factors of cardiovascular disorders, and it remains unclear whether chocolate consumption is related to reductions in hard cardiovascular outcomes (such as myocardial infarction and stroke).

We carried out a systematic review and meta-analysis of the scientific literature to evaluate the association between chocolate intake and the risk of developing cardiometabolic disorders, including cardiovascular disease (stroke, heart failure, and myocardial infarction), diabetes, and metabolic syndrome. We also evaluated whether this association would differ by type of cardiometabolic disorder, sex, and study characteristics.

Methods

We carried out a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies that evaluated the association between chocolate consumption and cardiometabolic disorders in adults. Between June 2010 and 5 October 2010 (last date searched) we searched Medline (1950 to present), Embase (1980 to present), the Cochrane Library (1960 to present), Scopus (1996 to present), Scielo (1997 to present), Web of knowledge (1970 to present), AMED (1985 to present), and CINHAL (1981 to present).

We used combinations of text words and thesaurus terms that included cacao[Mesh], cacao[Title/Abstract]*, chocolate, chocolate*[Title/Abstract], cocoa, cocoa*[Title/Abstract], cardiovascular diseases [Mesh], cardiovascular disease, cardiovascular, coronary artery disease [Mesh], atherosclerosis [Mesh], coronary disease [Mesh], coronary heart disease, coronary, myocardial, ischaemic heart disease, ischaemic heart disease*[Title/Abstract], ischemic heart disease, ischemic heart disease*[Title/Abstract], Heart Failure[Mesh], myocardial infarction [Mesh], myocardial ischemia [Mesh], stroke, stroke [Mesh], cerebral stroke, stroke, brain vascular accident, cerebrovascular stroke, cerebrovascular accident, cerebral vascular, cerebral vascular accident, cerebrovascular CVA, metabolic syndrome X [Mesh], metabolic syndrome, metabolic cardiovascular syndrome*[title/abstract], diabetes type 2, diabeti, diabete, diabet*[title/abstract], diabetes mellitus [Mesh], diabetes mellitus, type 2 [Mesh].

Studies were included if they were randomised controlled trials or cohort, case-control, or cross sectional studies; carried out in adults (≥18 years old); studied the effects of levels of chocolate consumption; the outcomes of interest were related to cardiometabolic disorders (cardiovascular disease, myocardial infarction, stroke, ischaemic heart disease, heart failure, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome); and had no language restriction (if necessary, local scientists fluent in the original language helped with translation). We excluded studies including only pregnant participants; letters, abstracts, systematic reviews, meta-analysis, ecological studies, and conference proceedings; and studies carried out in non-humans.

Two independent reviewers working in pairs (AB-L and OHF, JS, LJ, or SW) screened the titles and abstracts of the initially identified studies to determine if they satisfied the selection criteria. Any disagreements were resolved through consensus or consultation with a third reviewer. Full text articles were retrieved for the selected titles. Reference lists of the retrieved articles were searched for additional publications. We also contacted the authors of the retrieved papers directly for any additional and unpublished studies. The retrieved studies were assessed again by two independent authors (AB-L and OHF) to ensure that they satisfied the inclusion criteria.

Data extraction

We designed a data collection form before the implementation of the search strategy. Two independent reviewers used this form to extract the relevant information from the selected studies (AB-L and OHF). The data collection form included questions on qualitative aspects of the studies (such as date of publication, design, geographical origin and setting, funding source, selection criteria, patient samplings, and location of research group), participant characteristics (such number included in the analysis, age range, mean age, sex, ethnicity, recruitment procedures, residential region, socioeconomic status, comorbidities, and drug treatment), characteristics of the exposure or intervention evaluated (such as type, method used to measure), and information on the reported outcomes (such as measure of disease association, type of outcome, outcome assessment method, type of statistical analysis, adjustment variables).

Quality evaluation

Two independent reviewers (AB-L and OHF) evaluated the quality of the studies included using a modified scoring system that was created on the basis of a recently used system (designed with reference to MOOSE, QUATSO, and STROBE) that allowed a total score of 0–6 points (6 reflecting the highest quality).26 The system allocates one point each for (a) any justification given for the cohort; (b) appropriate inclusion and exclusion criteria were used; (c) diagnosis of cardiometabolic disorders was not solely based on self reporting; (d) participants’ usual chocolate consumption was assessed with a validated tool; (e) adjustments were made for age, sex, body mass index, and smoking status; and (f) any other adjustments were done (such as for physical activity, dietary factors).

Statistical analysis

We evaluated the differences between low and high chocolate consumption on outcomes such as diabetes, incidence of cardiovascular disease, cardiovascular mortality, coronary heart disease, incidence of stroke, and deaths from stroke. We pooled results using a random effects model, and we did tests for heterogeneity and publication bias. Results were expressed as pooled relative risks with 95% confidence intervals.

For each study, we compared the group with highest chocolate consumption against the group with the lowest consumption. Hazard ratios, relative risks, and odds ratios were assumed to approximate the same measure of relative risk. By pooling the study-specific estimates using a random effects model that included between-study heterogeneity (parallel analyses used fixed effect models), we calculated summary relative risks. We carried out a cumulative meta-analysis by outcome in which the pooled estimate of the association reported was updated each time the results of a new study were included. Possible sources of heterogeneity of relative risks were examined using the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test for the null hypothesis of no effect (relative risk=1), and the Mantel-Haenszel common relative risk estimate.27 The I2 (which quantifies the percentage of variation attributable to heterogeneity) was reported as a measure of consistency across the studies.

Finally, we assessed publication bias by using a funnel plot and Begg’s test to find out whether there was a bias towards publication of studies with positive results among studies with a smaller sample size.28

Subgroup analysis

To test the robustness of our findings, we repeated the meta-analysis by different outcomes (any cardiovascular disease, diabetes, heart failure, and stroke), sex, and types of chocolate (dark, milk, white).

Results

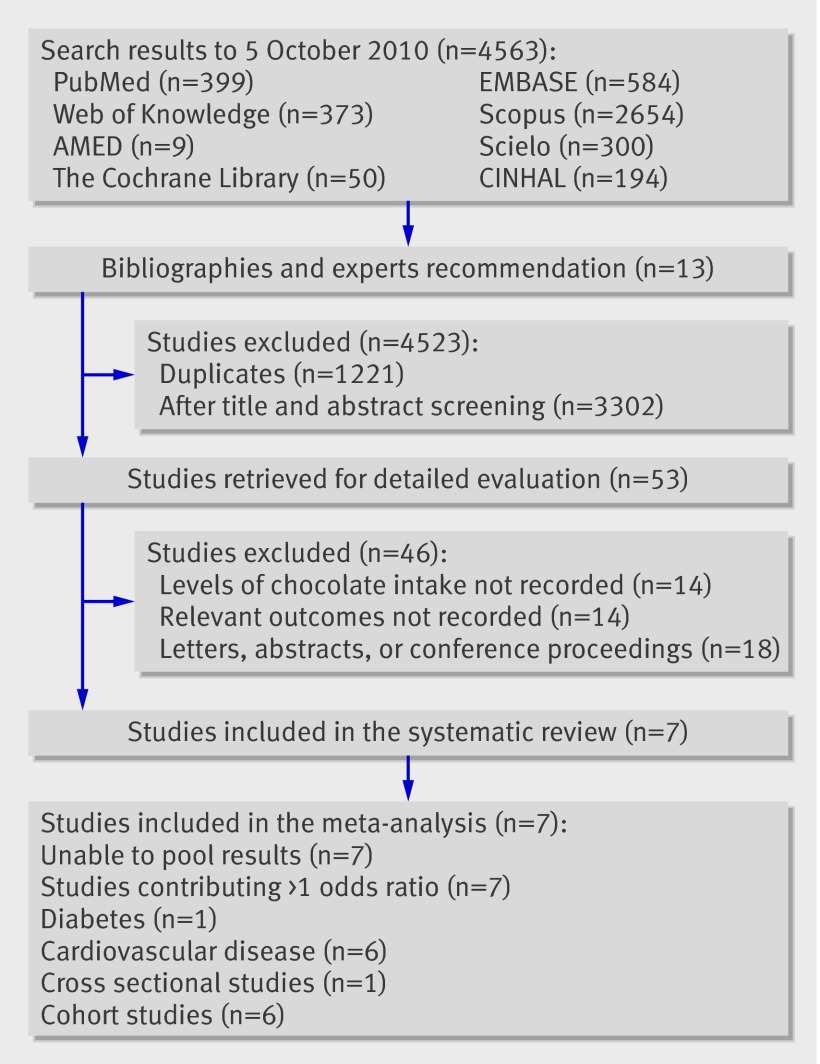

Overall, 4576 references were initially identified: 4563 from electronic databases and 13 from bibliographies and experts (fig 1). Among the databases most of the studies came from Scopus (n=2654) and Embase (n=584). Of the 4576 references, 1221 were duplicates (identified using reference manager and manual checks) and were excluded. After the initial screening of the title and abstract, a further 3302 citations were excluded, leaving 53 articles for retrieval. Full text assessment of these articles resulted in seven eligible studies that were included in our analyses. Of the 46 excluded, 14 did not report levels of chocolate consumption, 14 did not record the effects of chocolate intake on outcomes related to our study,11 12 17 20 21 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 and the remaining 18 were letters, abstracts, or conference proceedings.

Fig 1 Flow diagram for selection of studies

Characteristics of included studies

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the seven selected studies, which included 114 009 participants.7 9 10 13 14 15 16 One was a cross sectional study carried out in the United States. The other six were cohort studies carried out in Europe (Germany, Netherlands, and Sweden), Asia (Japan), and North America. Six studies were carried out in the community and one in hospital inpatients. Participants’ age ranged from 25 to 93 years. Although most of the participants were white, one study also included Hispanic and African-American people, and one studied an Asian population. Four studies included men and women, two included only women, and one included only men. In three studies, participants were taking drug treatment, including hormone replacement therapy and drugs for cardiovascular disease (calcium channel blockers, β blockers, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, diuretics, digitalis, nitrates, and aspirin). No study reported the effect of chocolate consumption on metabolic syndrome, and the outcomes reported included myocardial infarction, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, coronary heart disease, heart failure, and stroke (table 2). More than one outcome was measured in four studies, and for these the measure of association for each outcome was included in the analysis.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in meta-analysis of association of chocolate consumption with risk of cardiometabolic disorders

| Study (setting) | Intervention measures | Study design | Quality score* | Participants | Follow-up (years) | Outcome measures | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No in analysis | Characteristics | ||||||

| Oba et al 201016 (Japan) | Consumption of coffee, tea, chocolate snacks, and caffeine content | Cohort | 5 | 13 540 | Asian men and women | 10 | Incidence of diabetes |

| Mink et al 200714 (USA) | Flavonoid intake | Cohort | 5 | 34 489 | White postmenopausal women | 16 | Coronary heart disease, stroke, cardiovascular mortality |

| Janszky et al 200913 (Sweden) | Chocolate consumption | Cohort | 4 | 1169 | White men and women who had had an acute myocardial infarction | 8 | Cardiovascular mortality, recurrent myocardial infarction, stroke, congestive heart failure |

| Buijsse et al 20067 (Netherlands) | Cocoa intake | Cohort | 5 | 470 | White men | 15 | Blood pressure, cardiovascular mortality |

| Mostofsky et al 201015 (Sweden) | Chocolate intake | Cohort | 5 | 31 823 | Middle aged and elderly white women | 9 | Incidence of heart failure |

| Buijsse et al 20109 (Germany) | Chocolate consumption | Cohort | 5 | 19 357 | White men and women | 10 | Blood pressure, myocardial infarction, incident cardiovascular disease, stroke |

| Djousse et al 201010 (USA) | Chocolate consumption | Cross sectional | 5 | 4970 | Men and women of mixed ethnicity | NA | Coronary heart disease |

*Score 0-6, with 6 representing high quality.

Table 2.

Measures of disease association and adjustments to outcomes in studies of association of chocolate consumption with risk of cardiometabolic disorders

| Study | Outcome measures | Adjustments | Measures of association (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oba et al 201016 | Incidence of diabetes | Age, smoking status, body mass index, physical activity, education (years), alcohol intake, total energy intake, fat intake, menopausal status (in women) | Hazard ratios 0.65 (0.43 to 0.97) men, 0.73 (0.48 to 1.93) women |

| Mink et al 200714 | Coronary heart disease mortality, stroke mortality | Age, energy consumption, marital status, education, blood pressure, diabetes, body mass index, waist to hip ratio, physical activity, smoking, oestrogen use | Rate ratios 0.98 (0.88 to 1.10), 0.85 (0.70 to 1.03) |

| Janszky et al 200913 | Congestive heart failure, cardiovascular disease mortality, recurrent myocardial infarction, stroke | Age, sex, smoking status, obesity, physical inactivity, alcohol consumption (g/day), filtered coffee intake (cups/day), educational attainment, sweet score | Hazard ratios 0.78 (0.52 to 1.16), 0.34 (0.17 to 0.70), 0.86 (0.54 to 1.37), 0.62 (0.33 to 1.16) |

| Buijsse et al 20067 | Cardiovascular disease mortality | Age; body mass index; smoking status; alcohol consumption; physical activity; aspirin use; anticoagulant use; diet prescription (Y/N); consumption of: vegetables, fruit, low and medium fat dairy, meat, sugar confectionery other than chocolate, cookies, savoury foods, nuts, and coffee; and total calorie intake | Relative risk 0.50 (0.32 to 0.78) |

| Mostofsky et al 201015 | Heart failure | Age, education, body mass index, physical activity, smoking status, living alone, HRT intake, alcohol intake, family history of myocardial infarction before 60 years, self reported history of hypertension, and cholesterol level | Rate ratio 1.23 (0.73 to 2.08) |

| Buijsse et al 20109 | Myocardial infarction, stroke | Age, sex, alcohol intake, employment status, body mass index, waist circumference, smoking status, occupational physical activity, sports cycling, education, and total energy intake | Relative risks 0.73 (0.47 to 1.18), 0.52 (0.30 to 0.89) |

| Djousse et al 201010 | Coronary heart disease | Age, sex, dietary linoleic acid intake, education, exercise, smoking status, alcohol intake, fruit and vegetables intake, energy intake, non-chocolate candy intake | Odds ratio 0.43 (0.27 to 0.68) |

HRT=hormone replacement therapy

All of the studies reported overall chocolate consumption as the exposure (not reported separately whether dark or white chocolate), and one reported cocoa consumption.7 Six studies applied food frequency questionnaires to measure the exposure, with some minor modifications from original questionnaires using a single item from the food frequency questionnaire that asked about consumption of chocolate bars, snacks, or pieces. The remaining paper used estimates of chocolate consumption in patient diaries cross checked with dietary history adapted from populations.

Levels of chocolate consumption included the consumption of chocolate bars, chocolate drinks, and chocolate snacks (including confectionery, biscuits, desserts, nutritional supplements, and candy bars). All the studies reported chocolate consumption in a different manner: three categories (never, once a month to less than once a week, and once a week or more)16; two categories (less than once a week, once a week or more)14; four categories (never, less than once a month to less than once a week, once a week, and more than once a week)13; thirds of cacao intake7; five categories (none, 1–3/month, 1–2/week, 3–6/week, and >1/day)15; fourths of chocolate consumption (ranging from 1.7 g/day to 7.5 g/day)9; and four categories (none, 1–3/month, 1–4/week, and >5/week).10 Considering the heterogeneity in reporting and measuring chocolate consumption, we decided to use the lowest and highest categories to measure the association of chocolate consumption with cardiometabolic disorders.7 9 10 13 14 15 16

The range of time to follow-up for the cohort studies was between eight and 16 years. All studies were funded by public institutions, with no industry funding reported in the acknowledgements sections. Although no study scored the highest level of quality (maximum 6), overall the level was adequate, with six of the seven studies scoring 5 and one scoring 4 (table 1).

Association of chocolate consumption with cardiometabolic disorders by outcome

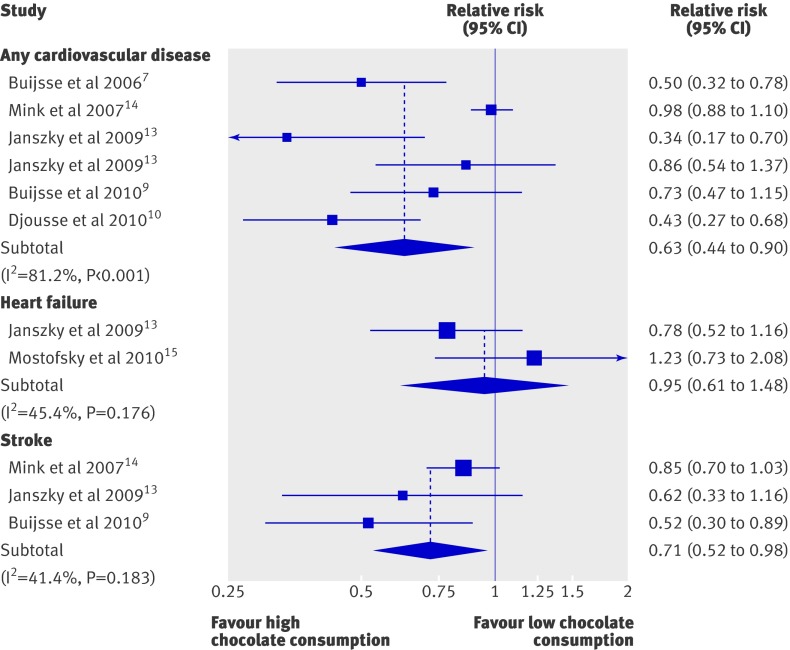

Of the seven included studies, five (14 875 participants with a high level of chocolate consumption) reported a significant inverse association between chocolate intake and cardiometabolic disorders (table 2, fig 2). Of the 13 measures of association used, 12 (92%) reported a beneficial association of higher chocolate consumption (compared with lowest consumption level) on the prevention of cardiometabolic disorders. The remaining measure was the association of chocolate consumption with heart failure (relative risk 1.23 (95% confidence interval 0.73 to 2.08)). All the measures of association reported were adjusted for age and multiple additional variables, including sex, body mass index, physical activity, smoking, dietary factors (including coffee consumption), and education. Some were also adjusted for drug use (table 2).

Fig 2 Relative risks for cardiovascular disease, heart failure, and stroke in adults with higher levels of chocolate consumption compared with lower levels

On pooling the retrieved measures of association, we found that high chocolate consumption was associated with about a third decrease in the risk of cardiometabolic disorders—37% in the case of any cardiovascular disease (relative risk 0.63 (95% confidence interval 0.44 to 0.90)) and 29% in the case of stroke prevention (0.71 (0.52 to 0.98)) (see fig 2). No significant association was observed in relation to heart failure (relative risk 0.95 (0.61 to 1.48)).

Only one study evaluated the association between chocolate consumption and diabetes, and it reported a beneficial association in Japanese men and women (hazard ratios 0.65 (0.43 to 0.97) and 0.73 (0.48 to 1.13) respectively).

Publication bias

Funnel plot analysis showed no evidence of significant publication bias (see extra figure on bmj.com).

Discussion

Higher levels of chocolate consumption were associated with a reduction of about a third in the risk of cardiometabolic disorders in our meta-analysis. This beneficial association was significant for any cardiovascular disease (37% reduction), diabetes (31% reduction, based on one publication), and stroke (29% reduction), but no significant association was found in relation to heart failure.

Five of the seven studies included in this meta-analysis reported a significant reduction in the risk of developing cardiometabolic disorders associated with higher levels of chocolate intake (one on cocoa intake), even after adjustment for potential confounders, including age, physical activity, body mass index, smoking status, dietary factors, education, and drug use. Although we did not find any experimental studies (randomised controlled trials) evaluating the effect of chocolate on hard cardiometabolic outcomes, our findings corroborate those of previous meta-analyses of experimental and observational studies in different populations related to risk factors for cardiometabolic disorders.18 19 23 24 25 These favourable effects seem mainly mediated by the high content of polyphenols present in cocoa products and probably accrued through increasing the bioavailability of nitric oxide, which subsequently might lead to improvements in endothelial function, reductions in platelet function, and additional beneficial effects on blood pressure, insulin resistance, and blood lipids.5

Necessary cautions

Beyond the caution needed in interpretation of data from observational studies, one must also consider other aspects associated with chocolate consumption. For instance, the high energy density of commercially available chocolate (about 2100 kJ (500 kcal)/100 g) means excessive consumption will probably induce weight gain, a risk factor for hypertension, dyslipidaemia, diabetes, and cardiometabolic disorders in general.5 Hence the high sugar and fat content of commercially available chocolate should be considered, and initiatives to reduce it might permit an improved exposure to the beneficial effect of chocolate. However, the articles included in our analysis did not provide the information needed to evaluate any potential differences between different types of chocolate in the associations with cardiometabolic disorders.

Exploration of heterogeneity

Although our studies included populations with and without prior cardiovascular disease, the small numbers meant we could not evaluate whether the associations found would differ in terms of primary or secondary prevention. Nevertheless, data from previous meta-analyses evaluating the effect of chocolate intake on intermediate factors suggest that the beneficial effects might be similarly beneficial among those with existing cardiovascular disease as it is for those without these conditions.19 23 24 Further studies are required to confirm this.

We found no papers studying the relation between chocolate consumption and the risk of developing metabolic syndrome, and we identified only one study showing the relation between diabetes and chocolate intake (a positive association, especially in men).16 Although we aimed to evaluate the potential sex differences in the association of chocolate intake with cardiometabolic disorders, the lack of studies reporting stratified results by sex prevented this.

Only two of the studies included evaluated the potential association of chocolate intake with the risk of heart failure. Both studies found no significant effect.13 15 This could be related to the nature of the development of heart failure, as it generally occurs towards the end of the spectrum of cardiovascular disorders in terms of natural course and severity of disease. Eventually, this result may need to be examined by further studies.

Strengths and limitations of the review

Previous studies have evaluated the effect of chocolate intake on cardiovascular risk factors and prevention of cardiovascular disorders,18 19 22 23 24 25 but our systematic review is the first attempt to pull together the different existing studies that evaluated the associations of chocolate consumption with cardiometabolic events. One of the reasons for this is that the available literature on this topic is limited and novel, with all studies published in the past four years and with more than half of the included studies published in 2010. We expect further studies will be done to confirm or refute the results of our analyses. Of special importance, experimental evidence will be needed before any level of causality can be inferred from the existing findings, and residual confounding could be considered as a potential explanation for the associations observed.

Considering the limited data available, any conclusions should be cautious. Nevertheless, the current evidence on hard and intermediate outcomes suggests that chocolate might be a viable instrument in the prevention of cardiometabolic disorders if consumed in moderation and if efforts are made to reduce the sugar and fat content of currently available products. Beyond this, considering the acceptability and popularity of chocolate, the applicability of its consumption as a recommendation might suit multiple populations. This would be particularly relevant in developing countries, where most of the cacao plantations and production sites are located (the top producers of cacao include African countries such as the Ivory Coast, Asian countries such as Indonesia, and South American countries such as Brazil) but where the processed form might not be easily available. Chocolate could therefore provide a natural, convenient, and generally welcome prophylactic against the growing epidemics of cardiometabolic disorders in developing countries.

Generalisation of our findings is hampered by the geographical origin of the included studies, as they were mainly carried out in Europe and the United States. Future studies should provide detailed information about different populations or different ethnic groups in other geographical locations and from different socioeconomic levels. Moreover, it is important to assess the effect of different types of chocolate, as well as the measurement and amounts. Given the considerable heterogeneity in the information from the original studies, it was not possible for us to establish a clear dose-response relation between chocolate intake and the risk of cardiometabolic disorders. Furthermore, although most of the included studies adjusted for relevant factors that could confound the association between chocolate consumption and cardiometabolic disorders, the potential confounding effect of these factors might still be prevalent. Chocolate intake is likely to be underestimated by consumers, and may be underestimated to a larger extent by those with a higher body mass index. As people with a higher body mass index are also more likely to have a cardiovascular disease outcome, then the underestimation of their chocolate intake may induce an artificial inverse association between chocolate and risk of cardiovascular disease.

Other factors that might hamper the quality of recording chocolate consumption also need consideration. These include the potential effect of recall bias and the challenges of recording snacks (which might include chocolate) as these are generally under-reported compared with meals.

Conclusions

Cocoa products and chocolate have been consumed and enjoyed by humans for centuries. Although over-consumption can have harmful effects, the existing studies generally agree on a potential beneficial association of chocolate consumption with a lower risk of cardiometabolic disorders. Our findings confirm this, and we found that higher levels of chocolate consumption might be associated with a one third reduction in the risk of developing cardiovascular disease. Corroboration is now required from further studies, especially experimental studies to test causation rather than just association.

What is already known on this topic

The prevalence of cardiometabolic disorders is increasing worldwide

Cocoa and chocolate have been suggested to have antihypertensive, anti-inflammatory, anti-atherogenic, and anti-thrombotic effects

What this study adds

This meta-analysis of six cohort studies and one cross sectional study showed increased chocolate intake was significantly associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease

This beneficial association was significant for any cardiovascular disease (37% reduction), diabetes (31%), and stroke (29%), but no significant association was found in relation to heart failure

We thank Isla Kuhn (medical library, University of Cambridge) for her advice and support with the search strategy, Nadeem Sarwar for his valuable comments, and Jorge Daza (Fundacion Universitaria de Ciencias de la Salud, Hospital de San Jose Library) for his constant support.

Contributors: OHF conceived the study. AB-L, OHF, and EDA did the analyses. AB-L, JS, LJ, SW, AW, and OHF searched the literature and extracted the data. AB-L and OHF wrote the manuscript. JS, LJ, SW, AW, and EDA contributed to the initial revision of the manuscript. LJ contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript before publication. OHF is the guarantor.

Funding: This study received no specific funding.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2011;343:d4488

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author: Funnel plot test for publication bias

References

- 1.American Heart Association. Heart disease and stroke statistics 2010 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2010;121:e46-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Cardiovascular diseases. Fact sheet No 317. 2011. www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs317/fr/index.html.

- 3.Ogbera AO. Prevalence and gender distribution of the metabolic syndrome. Diabetol Metab Syndr 2010;2:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. 2008-2013 action plan for the global strategy for the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases. 2000. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2009/9789241597418_eng.pdf.

- 5.Corti R, Flammer AJ, Hollenberg NK, Luscher TF. Cocoa and cardiovascular health. Circulation 2009;119:1433-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balzer J, Heiss C, Schroeter H, Brouzos P, Kleinbongard P, Matern S, et al. Flavanols and cardiovascular health: effects on the circulating NO pool in humans. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2006;47(suppl 2):S122-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buijsse B, Feskens EJM, Kok FJ, Kromhout D. Cocoa intake, blood pressure, and cardiovascular mortality: the Zutphen Elderly Study. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:411-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buijsse B, Feskens EJ, Kok FJ, Kromhout D. Cocoa intake in relation to blood pressure and cardiovascular mortality in elderly men. Circulation 2006;113:303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buijsse B, Weikert C, Drogan D, Bergmann M, Boeing H. Chocolate consumption in relation to blood pressure and risk of cardiovascular disease in German adults. Eur Heart J 2010;31:1616-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Djousse L, Hopkins PN, Arnett DK, Pankow JS, Borecki I, North KE, et al. Chocolate consumption is inversely associated with calcified atherosclerotic plaque in the coronary arteries: the NHLBI Family Heart Study. Clin Nutr 2011;30:182-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Faridi Z, Njike VY, Dutta S, Ali A, Katz DL. Acute dark chocolate and cocoa ingestion and endothelial function: a randomized controlled crossover trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2008;88:58-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grassi D, Desideri G, Necozione S, Lippi C, Casale R, Properzi G, et al. Blood pressure is reduced and insulin sensitivity increased in glucose-intolerant, hypertensive subjects after 15 days of consuming high-polyphenol dark chocolate. J Nutr 2008;138:1671-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janszky I, Mukamal KJ, Ljung R, Ahnve S, Ahlbom A, Hallqvist J. Chocolate consumption and mortality following a first acute myocardial infarction: the Stockholm Heart Epidemiology Program. J Intern Med 2009;266:248-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mink PJ, Scrafford CG, Barraj LM, Harnack L, Hong CP, Nettleton JA, et al. Flavonoid intake and cardiovascular disease mortality: a prospective study in postmenopausal women. Am J Clin Nutr 2007;85:895-909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mostofsky E, Levitan EB, Wolk A, Mittleman MA. Chocolate intake and incidence of heart failure: a population-based, prospective study of middle-aged and elderly women. Circ Heart Fail 2010;3:612-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oba S, Nagata C, Nakamura K, Fujii K, Kawachi T, Takatsuka N, et al. Consumption of coffee, green tea, oolong tea, black tea, chocolate snacks and the caffeine content in relation to risk of diabetes in Japanese men and women. Br J Nutr 2010;103:453-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Allen RR, Carson L, Kwik UC, Evans EM, Erdman JW. Daily consumption of a dark chocolate containing flavanols and added sterol esters affects cardiovascular risk factors in a normotensive population with elevated cholesterol. J Nutr 2008;138:725-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Desch S, Schmidt J, Kobler D, Sonnabend M, Eitel I, Sareban M, et al. Effect of cocoa products on blood pressure: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Hypertens 2010;23:97-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ding EL, Hutfless SM, Ding X, Girotra S. Chocolate and prevention of cardiovascular disease: a systematic review. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2006;3:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grassi D, Lippi C, Necozione S, Desideri G, Ferri C. Short-term administration of dark chocolate is followed by a significant increase in insulin sensitivity and a decrease in blood pressure in healthy persons. Am J Clin Nutr 2005;81:611-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grassi D, Necozione S, Lippi C, Croce G, Valeri L, Pasqualetti P, et al. Cocoa reduces blood pressure and insulin resistance and improves endothelium-dependent vasodilation in hypertensives. Hypertension 2005;46:398-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hooper L, Kroon PA, Rimm EB, Cohn JS, Harvey I, Le Cornu KA, et al. Flavonoids, flavonoid-rich foods, and cardiovascular risk: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr 2008;88:38-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jia L, Liu X, Bai YY, Li SH, Sun K, He C, et al. Short-term effect of cocoa product consumption on lipid profile: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr 2010;92:218-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ried K, Sullivan T, Fakler P, Frank OR, Stocks NP. Does chocolate reduce blood pressure? A meta-analysis. BMC Med 2010;8:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taubert D, Roesen R, Schoemig E. Effect of cocoa and tea intake on blood pressure—a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:626-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carter P, Gray LJ, Troughton J, Khunti K, Davies MJ. Fruit and vegetable intake and incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2010;341:c4229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mantel N, Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst 1959;22:719-48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Irwig L, Macaskill P, Berry G, Glasziou P. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Graphical test is itself biased. BMJ 1998;316:470-1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Allen R, Carson LA, Kwik-Uribe C, Evans EM, Erdman JW. Daily consumption of flavanol rich dark chocolate bar with added sterol esters improves cardiovascular markers in a population with elevated cholesterol. FASEB J 2007;21:A338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Balzer J, Rassaf T, Heiss C, Kleinbongard P, Lauer T, Merx M, et al. Sustained benefits in vascular function through flavanol-containing cocoa in medicated diabetic patients a double-masked, randomized, controlled trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;51:2141-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crews WD Jr, Harrison DW, Wright JW. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial of the effects of dark chocolate and cocoa on variables associated with neuropsychological functioning and cardiovascular health: clinical findings from a sample of healthy, cognitively intact older adults. Am J Clin Nutr 2008;87:872-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davison K, Coates AM, Buckley JD, Howe PR. Effect of cocoa flavanols and exercise on cardiometabolic risk factors in overweight and obese subjects. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32:1289-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Farouque HM, Leung M, Hope SA, Baldi M, Schechter C, Cameron JD, et al. Acute and chronic effects of flavanol-rich cocoa on vascular function in subjects with coronary artery disease: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. Clin Sci (Lond) 2006;111:71-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heiss C, Jahn S, Taylor M, Real WM, Angeli FS, Wong ML, et al. Improvement of endothelial function with dietary flavanols is associated with mobilization of circulating angiogenic cells in patients with coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;56:218-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hermann F, Spieker LE, Ruschitzka F, Sudano I, Hermann M, Binggeli C, et al. Dark chocolate improves endothelial and platelet function. Heart 2006;92:119-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kurlandsky SB, Stote KS. Cardioprotective effects of chocolate and almond consumption in healthy women. Nutr Res 2006;26:509-16. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Monagas M, Khan N, Andres-Lacueva C, Casas R, Urpi-Sarda M, Llorach R, et al. Effect of cocoa powder on the modulation of inflammatory biomarkers in patients at high risk of cardiovascular disease. Am J Clin Nutr 2009;90:1144-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.