Abstract

The Caenorhabditis elegans tra-3 gene promotes female development in XX hermaphrodites and encodes an atypical calpain regulatory protease lacking calcium-binding EF hands. We report that despite the absence of EF hands, TRA-3 has calcium-dependent proteolytic activity and its proteolytic domain is essential for in vivo function. We show that the membrane protein TRA-2A, which promotes XX female development by repressing the masculinizing protein FEM-3, is a TRA-3 substrate. Cleavage of TRA-2A by TRA-3 generates a peptide predicted to have feminizing activity. These results indicate that proteolysis regulated by calcium may control some aspects of sexual cell fate in C. elegans.

Keywords: Calpain, protease, sex determination, C2 domain, signal transduction, calcium

Proteolysis is an essential feature of all living cells and is responsible for eliminating proteins during normal degradative turnover and also when their activities are no longer required during processes such as cell cycle regulation and apoptosis (Nunez et al. 1998; Koepp et al. 1999). There is increasing evidence indicating that regulated or specialized proteolysis plays an important role in controlling gene expression, cell fate, and cytoskeletal architecture during development. For example, proteolysis allows an intracellular region of the Notch/LIN-12 receptor to translocate to the nucleus and to activate transcription (Kimble et al. 1998). In addition, during the establishment of segment polarity in Drosophila, the transcriptional regulator Ci is activated in response to Hedgehog signaling, and is proteolytically inactivated when signaling is repressed (Aza-Blanc and Kornberg 1999). We became interested in understanding how the activities of one family of regulatory proteases, the calpains, modulate cell fate when the Caenorhabditis elegans tra-3 sex-determining gene was shown to encode a member of this family (Barnes and Hodgkin 1996).

The calpains are calcium-regulated thiol-proteases that selectively cleave proteins to modulate their activities, and are found universally in eukaryotes (Sorimachi et al. 1997; Mykles 1998). Typical mammalian calpains are heterodimeric, consisting of a large catalytic and a small regulatory subunit, and are ubiquitous in expression. Mammalian μ-, m-, and muscle-specific p94 calpains represent the most extensively studied large subunit isoforms. The large subunit has been divided into four domains (D-I–D-IV). D-II contains the catalytic triad of Cys, His, and Asn. D-IV contains four calmodulin-like calcium-binding EF hand motifs, which confer calcium dependence on proteolytic activity, and a fifth EF hand that may dimerize with the small subunit (Blanchard et al. 1997; Lin et al. 1997). The recently solved crystal structure of m-calpain indicates that D-III forms a C2-like fold that may bind calcium (Hosfield et al. 1999). The genome of C. elegans encodes many atypical calpains, but a small regulatory subunit has not yet been found (Consortium 1998).

The importance of calpains is emphasized by the finding that a defective p94 gene leads to human limb–girdle muscular dystrophy 2A (Richard et al. 1995). However, substrates for p94 are unknown, and in general, little is certain about the physiological activities of calpains, although they affect cell division, apoptosis, and cytoskeletal remodeling (Sorimachi et al. 1997). Alterations in calpain activity are also associated with degenerative pathologies such as Alzheimer disease, cataract, and arthritis (Wang and Yuen 1999). Therefore, the finding that tra-3 encodes a predicted calpain protease provided an excellent opportunity to adopt a genetic strategy for investigating calpain activity. Moreover, TRA-3 is the founding member of a new calpain subfamily that includes human and mouse homologs (Dear et al. 1997; Mugita et al. 1997); therefore, our studies should also provide insights about these vertebrate homologs.

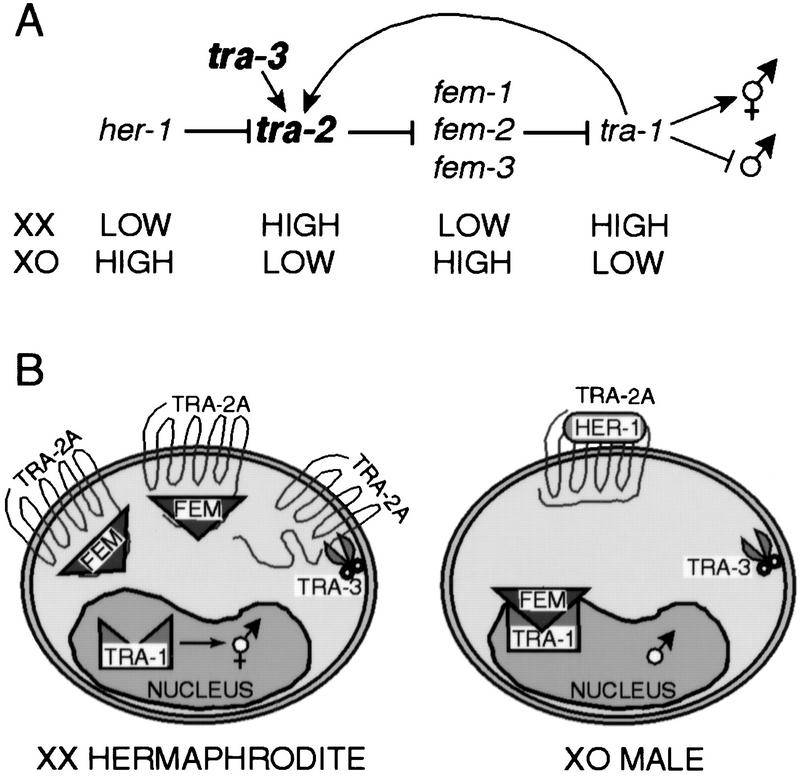

The genetic basis of sex determination has been analyzed extensively in the nematode C. elegans, which has two naturally occurring sexes, an XX hermaphrodite and an XO male (Meyer 1997; Kuwabara 1999; and references therein). The genes controlling sexual fate decisions have been ordered in a hierarchical pathway involving negative regulation (Fig. 1A). Somatic sex is determined by tra-1: High tra-1 activity leads to female development and low tra-1 activity leads to male development. At the molecular level, protein–protein interactions control many aspects of somatic sex determination (Fig. 1B). During XX hermaphrodite development, it is postulated that the membrane protein TRA-2A inactivates one or more of the FEM proteins. It was shown that a cytoplasmic carboxy-terminal region of TRA-2A binds FEM-3 and inhibits its ability to promote male development (Mehra et al. 1999; Fig. 1B, left). In turn, the transcriptional regulator TRA-1 promotes female development. During XO male development, TRA-2A is inactivated by its repressive ligand HER-1, thus allowing the FEM proteins to inactivate TRA-1 (Fig. 1B, right).

Figure 1.

Regulation of sexual fate in C. elegans focusing on the role of tra-3. (A) Simplified genetic pathway of somatic sex determination (Meyer 1997; Kuwabara 1999; and references therein). Wild-type XX diploids are hermaphrodites, which are self-fertile females that produce first sperm, then oocytes, and XO diploids are males. The pathway consists of a cascade of negative regulatory interactions, whereby an upstream gene inhibits the activity of its downstream neighbor. The state of each gene (high/low) during XX or XO development is indicated. The decision to adopt a male or female somatic fate is determined by tra-1. The pathway has been modified to indicate that tra-2 is epistatic to tra-3 (this work). (B) Molecular model of the signal transduction pathway underlying the genetic pathway of somatic sex-determination. In XX hermaphrodites, TRA-2A is depicted as a multipass membrane protein that binds and represses FEM-3 through its carboxyl terminus, possibly by sequestration. We propose that TRA-3 is a protease that cleaves and potentiates the activity of TRA-2A (this work); however, the fate of the carboxy-terminal TRA-2A peptide is unknown. TRA-3 is present in both sexes (S. Sokol and P. Kuwabara, unpubl.).

The tra-3 gene promotes female development in XX hermaphrodites (Hodgkin 1986). The absence of tra-3 transforms XX hermaphrodites into pseudomales, but has no effect on XO male development. The predicted TRA-3 protein was shown to share sequence similarity with members of the calpain protease family (Barnes and Hodgkin 1996); however, it was unknown whether TRA-3 had proteolytic activity or whether any of the sex-determining proteins were TRA-3 substrates. In this study, we have established that the C. elegans TRA-3 protein functions as a protease. We have found that TRA-3 undergoes calcium-dependent autolysis, and that its proteolytic domain is essential for in vivo function. We have also shown that TRA-2A is a substrate for TRA-3 and that the feminizing activity of tra-3 is dependent on tra-2 in vivo.

Results and Discussion

TRA-3 requires an intact proteolytic active site to promote female sexual development

The C. elegans sex-determining gene tra-3 encodes a predicted atypical calpain protease; TRA-3 lacks the calcium-binding EF hands found in ubiquitous calpains and instead carries an unrelated domain T (Fig. 2A) (Barnes and Hodgkin 1996). In general, little is known about the regulation of atypical calpains or their physiological roles in development (Sorimachi et al. 1997). Thus, it was not clear that TRA-3 would display calcium-dependent proteolytic activity. As a first step toward understanding the role of TRA-3 in C. elegans sex determination, we showed that a full-length tra-3 cDNA driven by the heat shock promoter (HS–TRA-3) rescued all aspects of the XX tra-3 mutant phenotype; 25/30 XX tra-3; crEx10 animals expressing HS–TRA-3 developed as fertile hermaphrodites and not as pseudomales.

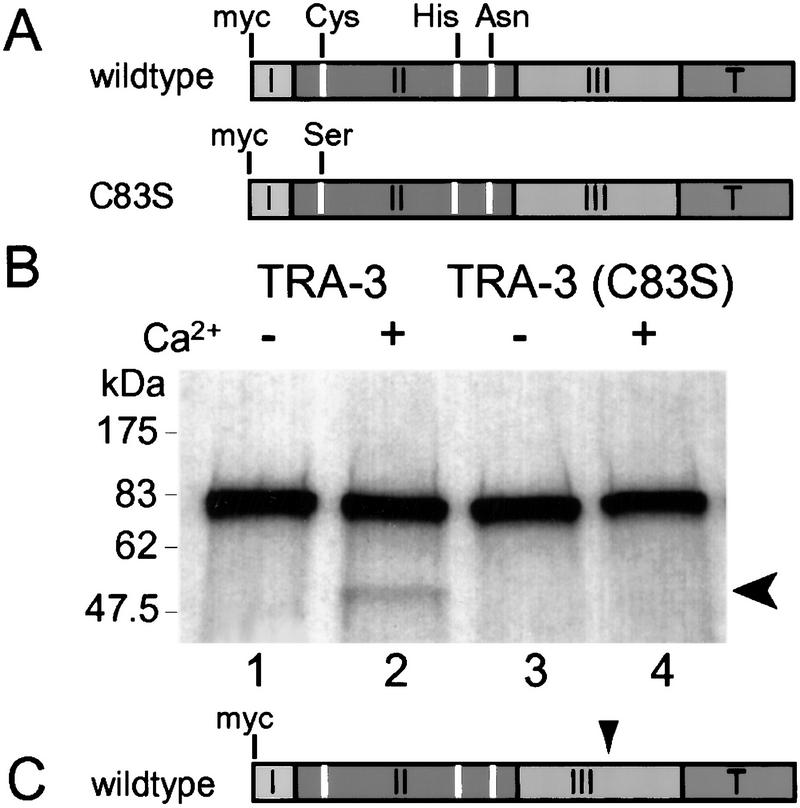

Figure 2.

The C. elegans sex-determining protein TRA-3 catalyzes calcium-dependent autolysis in vitro. (A) Schematic representation of amino-terminally myc-tagged wild-type TRA-3 and catalytically inactive TRA-3(C83S) expressed in vitro. The catalytic triad of Cys, His, and Asn is marked in white. The four domains of TRA-3 are labeled I–III, and T. (B) Wild-type TRA-3 incubated in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 5 mm calcium (lanes 1,2); catalytically inactive TRA-3(C83S) incubated in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 5 mm calcium (lanes 3,4). Full-length TRA-3 (∼76 kD); (arrow) TRA-3 cleavage product (∼50 kD). (C) Predicted site of TRA-3 autolysis based on sizes of wild-type and truncated TRA-3 cleavage products (S. Sokol and P. Kuwabara, unpubl.).

To test the role of the predicted catalytic domain, we mutated the catalytic cysteine to serine (C83S) and attempted to rescue XX tra-3 mutant animals with HS–TRA-3(C83S). However, we failed to detect any fertile XX tra-3; crEx58 hermaphrodites after heat shock (n = 55). This experiment was repeated using the native tra-3 promoter because we had obtained evidence that some forms of TRA-3 might be less stable when induced by heat shock than when expressed from the native promoter (S. Sokol and P. Kuwabara, unpubl.). However, the TRA-3(C83S) construct driven from the native tra-3 promoter was again unable to rescue the fertility of XX tra-3; crEx66 or crEx67 mutants (n = 35 and n = 55), indicating that an intact active site is required for TRA-3 activity.

The C. elegans sex-determining TRA-3 protein is a protease

To test more directly whether TRA-3 has proteolytic activity, we asked whether TRA-3 was capable of autolysis (Goll et al. 1992; Mykles 1998). This was achieved by programming calcium-depleted rabbit reticulocyte lysates to synthesize 35S-labeled TRA-3 (Fig. 2A). In the absence of exogenous calcium, only full-length wild-type TRA-3 was detected (76 kD) (Fig. 2B, lane 1). However, after adding calcium, a TRA-3 cleavage product (∼50 kD) was also detected (Fig. 2B, lane 2); this cleavage was consistently observed using independent batches of lysate. The generation of this cleavage product was dependent on active TRA-3. The addition of calcium failed to produce a cleavage product from a catalytically inactive TRA-3(C83S) (Fig. 2B, lanes 3,4), although wild-type and inactive TRA-3 were expressed at comparable levels (Fig. 2B, lanes 1,3).

How do we explain the basis for this calcium-dependent autolysis when TRA-3 is known to lack calmodulin-like EF hands? The recently solved crystal structure of m-calpain provides a possible explanation. This structure reveals that D-III unexpectedly possesses a C2-like fold (Hosfield et al. 1999). C2 domains participate variously in calcium binding, phospholipid binding, and in mediating protein–protein interactions (Nalefski and Falke 1996). Sequence similarities between the D-III regions of m-calpain and TRA-3 suggest that TRA-3 may also contain a C2 domain. We have also detected by sequence analysis a second C2 site in domain T of TRA-3. Because most known C2 domains bind calcium, these C2 domains may be responsible for the calcium dependence of TRA-3 activity, and perhaps for localizing TRA-3 to the membrane. However, because TRA-3 can promote female development when domain T is absent (Barnes and Hodgkin 1996), this indicates that the C2 domain associated with D-III is primarily responsible for the calcium dependence of TRA-3. Therefore, we further suggest that D-III also participates in the calcium-mediated regulation of other calpains. The purpose of the calcium-dependent autolysis of TRA-3 is unclear. Although some studies indicate that limited amino-terminal autolysis of calpains can lower the calcium concentration required to reach maximal proteolytic activation (Goll et al. 1992; Mykles 1998), the autolysis of TRA-3 observed by us is not similarly amino-terminal (Fig. 2C). Therefore, we speculate that autolysis probably inactivates TRA-3 and may serve to limit its activity.

C. elegans sex-determining proteins are stably expressed and properly localized in Sf9 cells

Physiological substrates for calpain proteases have yet to be identified. However, potential TRA-3 substrates are probably confined in function to sex determination and are unlikely to be involved in any essential cellular processes because the absence of TRA-3 does not affect XO male development. On the basis of our knowledge of the pathway controlling sex determination (Fig. 1), potential TRA-3 targets include TRA-2A, the FEM proteins, and the not yet cloned laf-1 product (Goodwin et al. 1997). However, we concentrated on evaluating the transmembrane TRA-2A protein as a candidate substrate for three reasons. First, it had been suggested that tra-3 might act as a positive cofactor for tra-2 because it displayed a weaker loss-of-function phenotype than tra-2 and because strong hypermorphic tra-2 dominant alleles could partially suppress the requirement for tra-3 activity (Doniach 1986; Hodgkin 1986). Second, the activity and substrate specificity of calpains may be promoted by their localization to the membrane (Suzuki and Sorimachi 1998), which is also the location of TRA-2A. Third, TRA-2A has a number of carboxy-terminal PEST sequences, which sometimes target proteins for proteolysis (Kuwabara et al. 1992; Shumway et al. 1999).

To initiate these studies, we used a baculovirus system to express TRA-3 and TRA-2A, because a C. elegans tissue culture cell line does not exist and because this system is suited to the expression of integral membrane proteins (Tate and Grisshammer 1996). We first established that a TRA-3 protein carrying both myc and 6xHis tags could be stably expressed in Sf9 cells without requiring exogenous cofactors, such as a small regulatory subunit, although we could not eliminate the possibility that such factors might be present in Sf9 cells (Fig. 3A,B, lane 1). As a control, we expressed an inactive, but otherwise identical, TRA-3(C83S) (Fig. 3A,B, lane 2). We found that both wild-type TRA-3 and TRA-3(C83S) were robustly expressed, migrating with a mobility of 76 kD. To demonstrate that the addition of myc and 6xHis tags did not affect wild-type TRA-3 activity, we showed that an equivalent epitope-tagged TRA-3 construct driven from the C. elegans heat shock promoter retained the ability to rescue completely tra-3 mutants (data not shown).

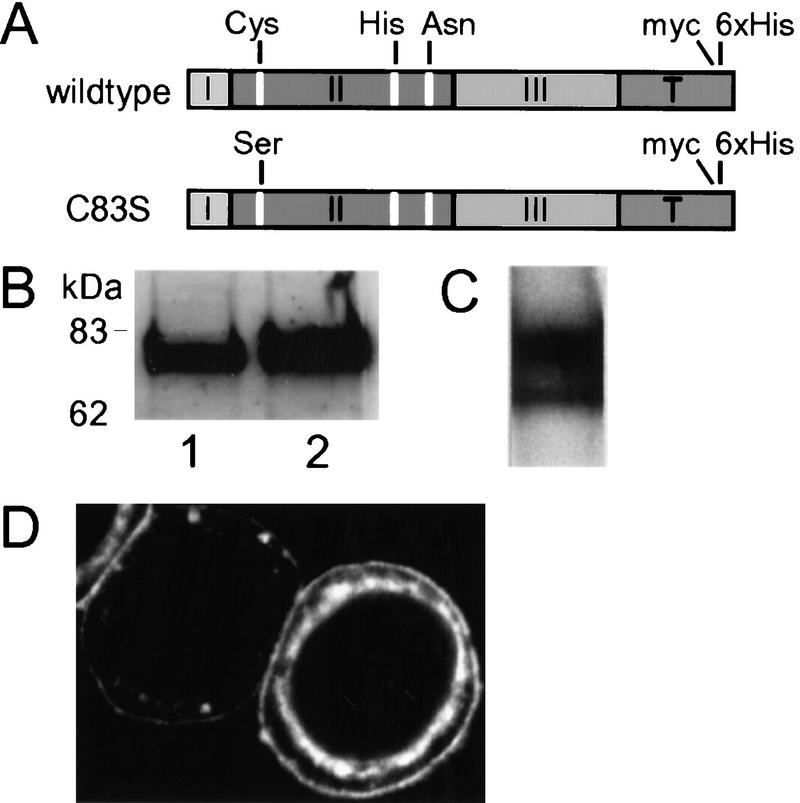

Figure 3.

Expression and immunological detection of myc-tagged TRA-3 and TRA-2A in Sf9 cells. (A) Schematic representation of wild-type TRA-3 and catalytically inactive TRA-3(C83S) proteins expressed in Sf9 cells (see legend to Fig. 2A). (B) Immunoblot of Sf9 extracts expressing TRA-3 or TRA-3(C83S) probed with anti-myc (lanes 1,2). (C) Immunoblot of membrane-enriched Sf9 extracts expressing myc-tagged TRA-2A probed with anti-TRA-2. (D) Localization of TRA-2A to the plasma membrane of Sf9 cells using anti-TRA-2. Note that cell at right expresses TRA-2A more strongly than cell at left because of variability in infection efficiency.

We next expressed the C. elegans sex-determining TRA-2A protein carrying a carboxy-terminal myc-tag in Sf9 cells. As shown by the immunoblot probed with anti-TRA-2 (C-term), TRA-2A is present in membrane-enriched extracts, and migrates as a doublet with a relative molecular mass of 170 kD (Fig. 3C). Only the upper band of the doublet is consistently detected with anti-myc or anti-TRA-2A (N-term, data not shown), suggesting that the lower band represents a partially degraded TRA-2A. Immunofluorescence analysis of infected Sf9 cells using anti-TRA-2 (C-term) verified that TRA-2A is associated with the plasma membrane and also with a perinuclear compartment that may be the endoplasmic reticulum (Fig. 3D). An identical pattern of fluorescence was also observed using anti-myc (data not shown). We also found that the ability to detect TRA-2A with anti-TRA-2 (C-term) or anti-myc was dependent first on permeabilizing the cell membrane with detergent, supporting the prediction that the carboxyl terminus of TRA-2A is cytoplasmic (Kuwabara et al. 1992; Mehra et al. 1999). Given that we could detect robust expression of TRA-3 and TRA-2A in Sf9 cells, and that the cellular localization and topology of TRA-2A appeared to be correct, we next tested whether TRA-2A might be a proteolytic substrate for TRA-3.

The C. elegans sex-determining protein TRA-2A is a substrate for TRA-3 calpain

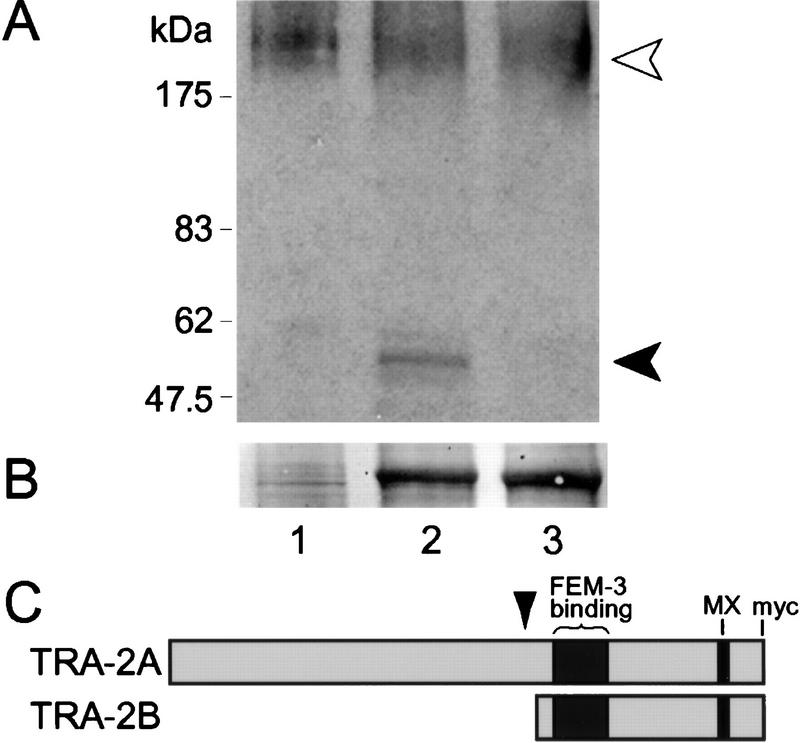

As shown by the immunoblot probed with anti-TRA-2, coexpression of TRA-2A and TRA-3 in Sf9 cells led to the production of a doublet corresponding to full-length TRA-2A and a smaller 55-kD carboxy-terminal TRA-2A band. (Fig. 4A, lane 2). Because the antibodies are directed against the carboxyl terminus of TRA-2A and detect a discrete 55-kD band, we suggest that the 55-kD band results from endoproteolytic cleavage (Fig. 4C). We further found that the 55-kD TRA-2A peptide was only present when TRA-2A was coexpressed with TRA-3; we did not detect the 55-kD TRA-2A peptide when TRA-2A was expressed alone (Fig. 4A, lane 1) or when it was coexpressed with a catalytically inactive TRA-3(C83S) (Fig. 4A, lane 3). Expression levels of TRA-3 and TRA-3(C83S) were comparable on the basis of Ponceau S staining (Fig. 4B); the identity of these bands as TRA-3 was confirmed by Western analysis using anti-TRA-3 (data not shown). These data strongly indicate that TRA-3 can cleave TRA-2A to generate a carboxy-terminal TRA-2A peptide; hence, TRA-2A is a TRA-3 substrate.

Figure 4.

Proteolytic cleavage of TRA-2A by TRA-3. (A) Immunoblot probed with anti-TRA-2 of Sf9 cell extracts expressing TRA-2A alone (lane 1), coexpressing TRA-2A and wild-type TRA-3 (lane 2), or coexpressing TRA-2A and catalytically inactive TRA-3(C83S) (lane 3). (Open arrowhead) Full-length TRA-2A (∼170 kD); (solid arrowhead) carboxy-terminal TRA-2A proteolytic peptide (∼55 kD). (B) Immunoblot from A stained with Ponceau S to show that wild-type and inactive TRA-3 are comparably expressed. (C) Proposed relationship between TRA-2A/B and TRA-2A cleavage peptide. Predicted site of TRA-2A cleavage by TRA-3 is indicated by arrowhead.

The in vivo activity of tra-3 is dependent on tra-2

If TRA-2A is a substrate for TRA-3 in vivo, then we would predict that the ability of tra-3 to promote female development should be dependent on wild-type tra-2. To test this hypothesis, we generated the transgenic array crEx65, which expresses both HS–TRA-3 and a vit-2::gfp reporter. The vit-2::gfp reporter was included in this array because it is a sensitive indicator of feminization: normally vit-2::gfp expression is only detected in the intestine of XX hermaphrodites (Yi and Zarkower 1999). As expected, GFP was expressed in the intestines of all XX him-8; crEx65 hermaphrodites (n = 34), but never in the XO males (n = 36) (Fig. 5A,B). However, after applying multiple heat shocks to provide additional TRA-3 activity, we found that many (18/44) XO him-8; crEx65 males were partially feminized because they expressed GFP in their intestines (Fig. 5C,D). These results show that excess TRA-3 can feminize XO males. We next asked whether excess TRA-3 could still feminize when wild-type tra-2 was absent. For this experiment, we expressed the crEx65 transgene in XX tra-2 pseudomales; pseudomales might be expected to be more readily feminized than XO males, if feminization by tra-3 is not tra-2 dependent. After providing multiple heat shocks, no GFP fluorescence or other signs of feminization were detected in XX tra-2; crEx65 pseudomales (n = 60). These results show that (1) tra-3 overexpression causes limited XO intestinal feminization, (2) wild-type tra-2 is required for tra-3 function, and (3) tra-2 is epistatic to tra-3 in the sex determination pathway.

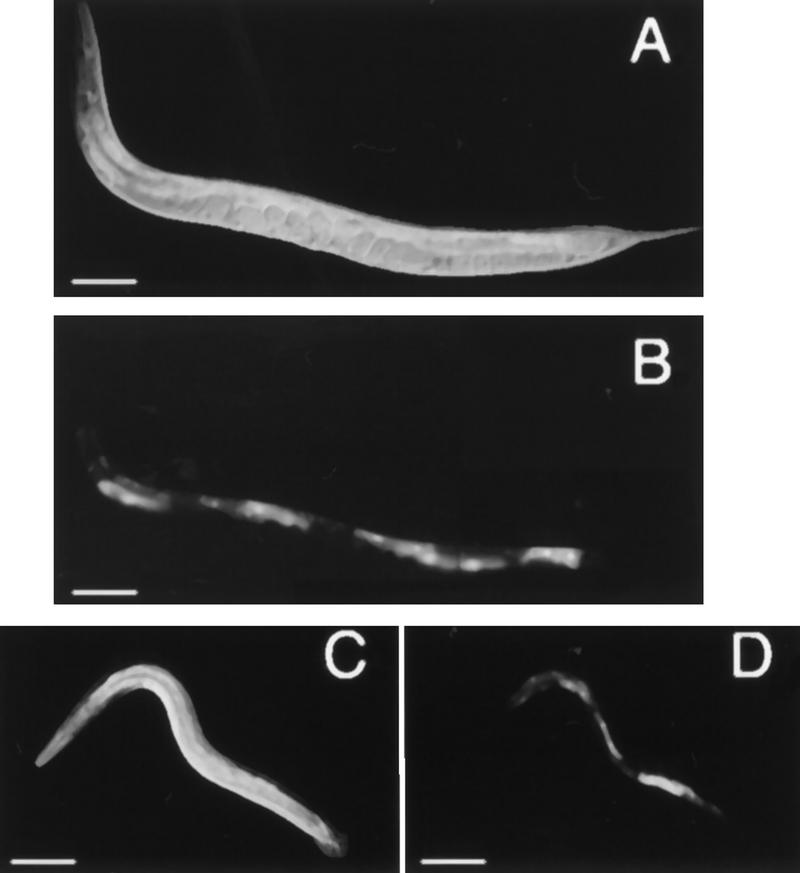

Figure 5.

Detection of somatic feminization in XX and XO animals using a vit-2::gfp reporter. (A) Nomarski DIC photomicrograph of an adult XX him-8; crEx65 hermaphrodite. (B) The same animal in A examined by epifluorescence to reveal intestinal GFP expression. (C) Nomarski DIC photomicrograph of an adult XO him-8; crEx65 male following heat shock. (D) The same animal in C examined by epifluorescence to reveal ectopic intestinal GFP fluorescence, which is indicative of somatic feminization. In all panels: anterior, left; ventral, down. Scale bar, 10 μm.

The role of TRA-3 and proteolysis in controlling sexual cell fate in C. elegans

How might cleavage of TRA-2A affect sex determination? First, we propose that the TRA-2A carboxy-terminal cleavage peptide has feminizing potential, because it is likely to encompass at least part of the region of TRA-2A shown previously to promote feminization, and may be comparable in sequence to the germ-line-specific TRA-2B (Fig. 4C) (Kuwabara and Kimble 1995; Kuwabara et al. 1998; Mehra et al. 1999). Because TRA-2B is identical in sequence to a predicted carboxy-terminal intracellular feminizing domain of TRA-2A, it was proposed that TRA-2A/B would be subject to the same shared regulatory controls (Kuwabara et al. 1998). We now extend this logic to include the TRA-2A cleavage peptide; more specifically, we propose that TRA-2A/B and the TRA-2A cleavage peptide share two regulatory sites, the FEM-3-binding region and the MX region.

The FEM-3-binding region was defined by the ability of non-membrane-bound TRA-2A peptides to bind FEM-3 and to feminize XO males (Kuwabara and Kimble 1995; Mehra et al. 1999). The balance between the activities of TRA-2A and FEM-3 influences the decision to adopt either a female or male fate. The MX region was identified by analyzing self-sterile tra-2(mx) mutants that failed to make sperm (Doniach 1986). It was proposed that the sites of these mutations delineated a binding domain for a potential tra-2 germ-line repressor that helped to promote hermaphrodite spermatogenesis by inhibiting tra-2. Subsequently, the germ-line-specific TRA-2B might titrate such a repressor to promote the switch from spermatogenesis to oogenesis (Kuwabara et al. 1998). Therefore, the TRA-2A cleavage peptide has the potential to promote female development by binding and inactivating FEM-3, as discussed previously (Kuwabara and Kimble 1995; Mehra et al. 1999), or perhaps to carry out functions similar to those ascribed to the germ-line-specific TRA-2B (Kuwabara et al. 1998).

Second, we propose that the TRA-2A peptide generated by TRA-3 may potentiate the activity of TRA-2A, but not replace the need for full-length TRA-2A. It was shown previously that overexpression of TRA-2A completely transformed an XO animal from male to hermaphrodite. Under similar conditions, the carboxy-terminal region of TRA-2A partially feminized the intestine and tail of XO animals (Kuwabara and Kimble 1995), similar in effect to HS–TRA-3 overexpression in XO animals. In conclusion, TRA-3 probably acts as a potentiator of tra-2 by proteolytically cleaving TRA-2A to generate a feminizing fragment.

Materials and methods

Nematode strains and handling

Standard methods for culturing and genetic manipulation of nematodes have been described (Sulston and Hodgkin 1988). Because tra-3 has a maternal effect, all rescue experiments refer to tra-3(m-z-) animals. Genes referred to in this manuscript: tra-3(e1767)IV; him-8(e1489)IV; unc-4(e120)II; and tra-2(e1095)II. tra-3 homozygotes were generated from the strain tra-3/nT1(dm). him-8 increases the frequency of XO male progeny from 0.2% to 37%. unc-4 is closely linked to tra-2 and displays a recessive uncoordinated phenotype, which facilitates identification of tra-2 unc-4 homozygotes. tra-2 strains were maintained as tra-2unc-4/mnC1.

Plasmid construction

Transgenic expression plasmids, pPK247 carries an RT–PCR-generated full-length tra-3 cDNA cloned in pBluescript KSII (Stratagene) and verified by sequencing. pPK251 encodes HS–TRA-3 and carries the insert from pPK247 cloned in pPD49.83 (A. Fire, Carnegie Institute, Baltimore, MD). pSS23 encodes HS–TRA-3(C83S) and was derived from pPK251. pPK297 encodes HS–TRA-3 with carboxy-terminal myc and 6xHis tags and was derived from pPK251. pSS41 carries the native tra-3 promoter (S. Sokol and P. Kuwabara, unpubl.) fused to the insert from pSS23. Plasmids for in vitro transcription/translation, pSS65 encodes TRA-3 and carries the insert from pPK247 cloned in pT7TAG, which carries the T7 promoter, β-globin 5′ UTR, and encodes an amino-terminal myc tag. pSS67 encodes TRA-3(C83S) and was derived from pSS65. Baculoviral expression constructs, pPK296 encodes TRA-3 with carboxy-terminal myc and 6xHis tags and was derived by cloning the insert from pPK247 into pBlueBac4 (Invitrogen) and ligating a sequence carrying the myc and 6xHis tags into a unique KpnI site of tra-3. pSS62 encodes TRA-3(C83S) and was derived from pPK296. pPK198 encodes the myc-tagged C. elegans sex-determining TRA-2A protein, and was constructed by ligating a 4.7-kb tra-2 cDNA with a carboxy-terminal myc-tag into the baculovirus transfer vector pVL1392 (Invitrogen). For details regarding plasmid constructions, contact author.

Generation of transgenic animals and heat shock experiments

Transgenic nematodes were generated by standard methods (Mello and Fire 1995) and carry a dominant Rol marker, rol-6(su1006) (pRF4 or pCes1943). pCR2 carries the vit-2::gfp reporter (Yi and Zarkower 1999). Extrachromosomal arrays were verified by PCR and are described below: crEx10, HS–TRA-3 (pPK251 + pRF4); crEx58, HS–TRA-3(C83S) (pSS23 + pRF4); crEx65, HS–TRA-3(myc,6xHis) + vit-2::gfp (pPK297 + pCR2 +pCes1943); crEx66, crEx67 tra-3::TRA-3(C83S) (pSS41 + pCes1943).Heat shock experiments consisted of incubating animals of the appropriate genotype daily for 1 hr at 33°C in an incubator or for 20–40 min in a 33°C water bath. XX tra-3(m-z-) pseudomales are variably masculinized, but are rarely self-fertile except when raised at 15°C (Hodgkin 1986). Because of this variability in somatic phenotype, we scored a transgenic construct as capable of rescuing tra-3 mutants only if it restored self-fertility.

Expression and detection of in vitro-synthesized TRA-3

pSS65 and pSS67 were used as templates to synthesize 35S-labeled TRA-3 and TRA-3(C83S) proteins in the reticulocyte TnT Quick system (Promega); samples were prepared in duplicate. After translation, one sample was adjusted to a CaCl2 concentration of 5 mm then all samples were incubated for 1 hr at 30°C. Samples were separated on a 10%–20% gradient polyacrylamide gel and processed for autoradiography.

Insect cell culture and production of recombinant baculovirus

Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf9) cells were grown in TNM-FH medium (Sigma) with 10% FCS, 50 μg/ml gentamycin and lipids (GIBCO BRL), at 27°C, with shaking at 150 rpm. Recombinant Autographica californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus (AcMNPV) was generated with either the Max Bac or Bac-n-Blue system (Invitrogen) and propagated as instructed.

Immunofluorescence

Recombinant protein was obtained from bacteria expressing the carboxy-terminal 343 amino acids common to TRA-2A and TRA-2B (Kuwabara et al. 1998) and used to raise antisera in rats.

Sf9 cells were grown on sterile ring slides for 24–36 hr at 27°C. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, washed with PBS and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100, then incubated overnight at 4°C with rat anti-TRA-2 serum (1:100). After washing, cells were incubated for 30 min with FITC-conjugated anti-rat IgG (Sigma; 1:200). Slides were mounted for microscopy using a medium containing DABCO.

Immunoblot detection of recombinant proteins

Recombinant TRA-3 proteins were prepared for immunoblot analysis as follows. Sf9 cells were harvested, washed with PBS, and solubilized in buffer A (10 mm HEPES at pH 7.9, 2 mm EDTA, 2% Triton X-100, 2 mm DTT, 100 μm PMSF, 5 μm pepstatin, 10 μg/ml aprotinin) for 1 hr on ice. Extracts were electrophoresed under denaturing conditions and the proteins transferred to nitrocellulose; the efficiency of transfer was assessed by Ponceau S staining. Blots were probed with either 9E10 (anti-myc; 1:50) or anti-TRA-2 (1:5000) and visualized using ECL (Amersham). Membrane-enriched extracts were prepared by homogenizing Sf9 cells in buffer A, removing nuclei by centrifugation at 2K for 15 min at 4°C and pelleting membranes by centrifugation at 55K for 1 hr at 4°C. The membrane pellet was resuspended on ice in 25 mm HEPES (pH 7.9), 0.1 m NaCl, 2 mm DTT, 2 mm EDTA, 100 μm PMSF, 5 μm pepstatin, and 1% Triton X-100.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Hodgkin for support and advice throughout the course of these studies. We thank Z. Jia for sharing data prior to publication, A. Fire, P. MacMorris, and D. Zarkower for providing DNA clones, and members of the calpain and C. elegans communities for discussion. S.B.S. was supported by a Fulbright-Cambridge Research Scholarship administered by the Cambridge Overseas Trust on behalf of the US-UK Fulbright Commission.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL pek@sanger.ac.uk; FAX 44 (1223) 494919.

References

- Aza-Blanc P, Kornberg TB. Ci: A complex transducer of the hedgehog signal. Trends Genet. 1999;15:458–462. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01869-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes TM, Hodgkin J. The tra-3 sex determination gene of Caenorhabditis elegans encodes a member of the calpain regulatory protease family. EMBO J. 1996;15:4477–4484. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard H, Grochulski P, Li Y, Arthur JS, Davies PL, Elce JS, Cygler M. Structure of a calpain Ca2+-binding domain reveals a novel EF-hand and Ca2+-induced conformational changes. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:532–538. doi: 10.1038/nsb0797-532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The C. elegans Sequencing Consortium (Consortium) Genome sequence of the nematode C. elegans: A platform for investigating biology. Science. 1998;282:2012–2018. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dear N, Matena K, Vingron M, Boehm T. A new subfamily of vertebrate calpains lacking a calmodulin-like domain: Implications for calpain regulation and evolution. Genomics. 1997;45:175–184. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doniach T. Activity of the sex-determining gene tra-2 is modulated to allow spermatogenesis in the C. elegans hermaphrodite. Genetics. 1986;114:53–76. doi: 10.1093/genetics/114.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goll DE, Thompson VF, Taylor RG, Zalewska T. Is calpain activity regulated by membranes and autolysis or by calcium and calpastatin? BioEssays. 1992;14:549–556. doi: 10.1002/bies.950140810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin EB, Hofstra K, Hurney CA, Mango S, Kimble J. A genetic pathway for regulation of tra-2 translation. Development. 1997;124:749–758. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.3.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkin J. Sex determination in the nematode C. elegans: Analysis of tra-3 suppressors and characterization of fem genes. Genetics. 1986;114:15–52. doi: 10.1093/genetics/114.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosfield CM, Elce JS, Davies PL, Jia Z. Crystal structure of calpain reveals the structural basis for Ca2+-dependent protease activity and a novel mode of enzyme activation. EMBO J. 1999;18:6880–6889. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.24.6880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimble J, Henderson S, Crittenden S. Notch/LIN-12 signaling: Transduction by regulated protein slicing. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23:353–357. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01263-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koepp DM, Harper JW, Elledge SJ. How the cyclin became a cyclin: Regulated proteolysis in the cell cycle. Cell. 1999;97:431–434. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80753-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwabara PE. Developmental genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans sex determination. Curr Top Dev Biol. 1999;41:99–132. doi: 10.1016/s0070-2153(08)60271-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwabara PE, Kimble J. A predicted membrane protein, TRA-2A, directs hermaphrodite development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development. 1995;121:2995–3004. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.9.2995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwabara PE, Okkema PG, Kimble J. tra-2 encodes a membrane protein and may mediate cell communication in the Caenorhabditis elegans sex determination pathway. Mol Biol Cell. 1992;3:461–473. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.4.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwabara PE, Okkema PG, Kimble J. Germ-line regulation of the Caenorhabditis elegans sex-determining gene tra-2. Dev Biol. 1998;204:251–262. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin GD, Chattopadhyay D, Maki M, Wang KK, Carson M, Jin L, Yuen PW, Takano E, Hatanaka M, DeLucas LJ, Narayana SV. Crystal structure of calcium bound domain VI of calpain at 1.9 A resolution and its role in enzyme assembly, regulation, and inhibitor binding. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:539–547. doi: 10.1038/nsb0797-539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehra A, Gaudet J, Heck L, Kuwabara PE, Spence AM. Negative regulation of male development in Caenorhabditis elegans by a protein–protein interaction between TRA-2A and FEM-3. Genes & Dev. 1999;13:1453–1463. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.11.1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello C, Fire A. DNA transformation. Methods Cell Biol. 1995;48:451–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer BJ. Sex determination and X chromosome dosage compensation. In: Riddle DL, Blumenthal T, Meyer BJ, Priess JR, editors. C. elegans II. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. pp. 209–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugita N, Kimura Y, Ogawa M, Saya H, Nakao M. Identification of a novel, tissue-specific calpain htra-3; a human homologue of the Caenorhabditis elegans sex determination gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;239:845–850. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mykles DL. Intracellular proteinases of invertebrates: Calcium-dependent and proteasome/ubiquitin-dependent systems. Int Rev Cytol. 1998;184:157–289. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)62181-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalefski EA, Falke JJ. The C2 domain calcium-binding motif: Structural and functional diversity. Protein Sci. 1996;5:2375–2390. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560051201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunez G, Benedict MA, Hu Y, Inohara N. Caspases: The proteases of the apoptotic pathway. Oncogene. 1998;17:3237–3245. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard I, Broux O, Allamand V, Fougerousse F, Chiannilkulchai N, Bourg N, Brenguier L, Devaud C, Pasturaud P, Roudaut C, et al. Mutations in the proteolytic enzyme calpain 3 cause limb-girdle muscular dystrophy type 2A. Cell. 1995;81:27–40. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90368-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shumway SD, Maki M, Miyamoto S. The PEST domain of IκBα is necessary and sufficient for in vitro degradation by μ-calpain. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:30874–30881. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.43.30874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorimachi H, Ishiura S, Suzuki K. Structure and physiological function of calpains. Biochem J. 1997;328:721–732. doi: 10.1042/bj3280721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulston J, Hodgkin J. Methods. In: Wood WB, editor. The nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1988. pp. 587–606. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki K, Sorimachi H. A novel aspect of calpain activation. FEBS Lett. 1998;433:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00856-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tate C G, Grisshammer R. Heterologous expression of G-protein-coupled receptors. Trends Biotechnol. 1996;14:426–430. doi: 10.1016/0167-7799(96)10059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang KKW, Yuen P-W. Calpains: Pharmacology and toxicology of a cellular protease. Washington, D.C.: Taylor & Francis Inc.; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Yi W, Zarkower D. Similarity of DNA binding and transcriptional regulation by Caenorhabditis elegans MAB-3 and Drosophila melanogaster DSX suggests conservation of sex determining mechanisms. Development. 1999;126:873–881. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.5.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]