Abstract

The 5.5 protein (T7p32) of coliphage T7 (5.5T7) was shown to bind and inhibit gene silencing by the nucleoid-associated protein H-NS, but the mechanism by which it acts was not understood. The 5.5T7 protein is insoluble when expressed in Escherichia coli, but we find that 5.5T7 can be isolated in a soluble form when coexpressed with a truncated version of H-NS followed by subsequent disruption of the complex during anion-exchange chromatography. Association studies reveal that 5.5T7 binds a region of H-NS (residues 60 to 80) recently found to contain a distinct domain necessary for higher-order H-NS oligomerization. Accordingly, we find that purified 5.5T7 can disrupt higher-order H-NS-DNA complexes in vitro but does not abolish DNA binding by H-NS per se. Homologues of the 5.5T7 protein are found exclusively among members of the Autographivirinae that infect enteric bacteria, and despite fairly low sequence conservation, the H-NS binding properties of these proteins are largely conserved. Unexpectedly, we find that the 5.5T7 protein copurifies with heterogeneous low-molecular-weight RNA, likely tRNA, through several chromatography steps and that this interaction does not require the DNA binding domain of H-NS. The 5.5 proteins utilize a previously undescribed mechanism of H-NS antagonism that further highlights the critical importance that higher-order oligomerization plays in H-NS-mediated gene repression.

INTRODUCTION

Bacteria employ an array of diverse strategies to control infection by phages, which are met by an equally diverse array of phage countermeasures. Frequent changes in the cell surface, restriction enzymes, spacer sequences within clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR) elements, and toxin-antitoxin systems maintain immune diversity that prevent any phage lineages from gaining an overwhelming advantage over their bacterial hosts (26, 27, 32). One factor that could play a role in bacterial protection from phage infection is the nucleoid-associated protein H-NS. H-NS has been shown to play a major role in silencing transcription from sequences that are more AT-rich than the host genome, a characteristic of many genes that have been obtained via horizontal (lateral) gene transfer (15, 20, 45). The silencing of such sequences by H-NS, termed xenogeneic silencing, is thought to allow bacteria to safely acquire new genetic material without compromising their genomic and regulatory integrity (45). Although H-NS plays a clear role in mitigating the negative consequences presented by horizontally acquired genetic material, the role of H-NS in phage biology has remained largely unexplored.

A feature that is critical for H-NS function is its ability to multimerize to form higher-order nucleoprotein complexes (3, 60). The 80 N-terminal amino acids of H-NS contain two distinct dimerization domains that form an extended “superhelical scaffold” via head-to-head/tail-to-tail interactions (2). These H-NS scaffolds can bridge adjacent DNA segments in vitro that may organize the nucleoid into discrete loops and allow the molecule to constrain supercoiling within isolated domains (11, 12, 24, 48). Loops in DNA formed by H-NS may either trap RNA polymerase within the promoter region of a target gene or occlude the RNA polymerase from accessing the promoter sequence, preventing its active transcription (12, 56, 57). The ability of H-NS to constrain supercoils may also enable it to control promoters that are sensitive to supercoiling (24, 25, 43). Quite recently, studies have found that under certain conditions (e.g., low concentrations of magnesium in vitro), H-NS can coat DNA in a mode of binding distinct from bridging known as “stiffening,” which could also lead to repression of target genes by a mechanism that is not yet understood (37, 67). Which of these two modes of binding predominates under physiologically relevant conditions is currently unclear.

Many antiphage systems are also encoded on mobile genetic elements, including plasmids and lysogenized phages, and presumably, by encoding such functions, these elements gain a territorial advantage by prolonging the survival of their hosts (18). Phage lambda, for example, encodes the rexAB genes that function to abort lytic growth by competing phages (53). Phage T4 rII mutants fail to infect rexAB+ lambda lysogens, a finding that was exploited to dissect fundamental gene structure, indicating that a subset of phages have effective countermeasures to lambda restriction (5). Growth of wild-type coliphage T7 in Escherichia coli is restricted by a number of mobile genetic elements, including Col1B and F-plasmids (17, 19, 44). It is notable that H-NS paralogs are frequently encoded on genomic islands and mobile genetic elements, including conjugative plasmids and, as recently identified, on phages (58). The plasmid-encoded H-NS paralog, Sfh, prevents disruption of regulatory networks likely caused by titration of endogenous H-NS by AT-rich plasmid sequences (14, 16). Whether H-NS paralogs play additional roles, such as protection against other foreign elements, including phages, has not been tested.

The 5.5 gene of coliphage T7 was originally identified during a random screen of highly mutagenized T7 phages for changes in protein expression (62). The product of the 5.5 gene (the 5.5T7 protein or gp5.5T7) contributes to T7 growth on E. coli lysogens of phage lambda, and a mutant allele of the 5.5 gene renders T7 unable to infect E. coli that is lysogenized with phage lambda (the restricted by lambda, or rbl, phenotype) (35, 52). The allele that leads to the rbl phenotype has been mapped to a change in a single nucleotide that converts a leucine at position 30 of gp5.5T7 to a proline (35). Whether or not the primary function of gp5.5T7 is to enable T7 to avoid restriction by lambda-like phages is less clear. The rbl phenotype has only thus far been demonstrated for the L30P allele, here referred to as gp5.5T7(rbl). T7 phages containing a mutation of L30 to threonine or a premature amber codon in the 5.5 gene display normal growth on lambda lysogens (35). In a separate study, Liu and Richardson reported that gp5.5T7 but not gp5.5T7(rbl) tightly associates with H-NS and demonstrated that it could antagonize silencing of the proU operon and T7 promoters by H-NS (36). The relationships between gp5.5T7, H-NS, and genes carried on the lambda lysogen that restrict T7 mutants remain entirely unclear.

Phage T7 therefore serves as an attractive system to study the interaction of a phage with H-NS. The 5.5T7 protein bears no sequence homology to any other known protein, and the mechanism by which it interacts with H-NS to inhibit its function has not been explored. Here, we describe our initial work to characterize the gp5.5T7/H-NS interaction and the mechanism by which gp5.5T7 blocks H-NS-mediated gene repression. Phylogenetic analysis reveals that proteins related to 5.5T7 are found exclusively in T7-like viruses (Autographivirinae) that infect enterobacteria. Although gp5.5T7 is insoluble when expressed by itself, we have developed a method of purifying stable and soluble 5.5T7 protein through coexpression with a truncated H-NS fragment that is subsequently removed. We find that the 5.5T7 protein interacts with a recently identified central dimerization domain within H-NS to disrupt higher-order nucleoprotein complexes without perturbing DNA binding per se. We also unexpectedly find that gp5.5T7 copurifies a heterogeneous mix of tRNA. H-NS antagonism through interference with the second oligomerization domain supports the role of this domain in formation of a proper nucleoprotein structure that is essential for H-NS-mediated gene silencing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction.

Information about oligonucleotides, strains, and plasmids used in this study is summarized in Tables 1 and 2. The Salmonella hns locus was amplified from genomic DNA of strain LT2 using primers SSA1 and SSA2. The hns fragment was digested with NdeI and XhoI and ligated to the corresponding sites of pET-21b. The resulting plasmid, pSSA2, was used for production of the H-NS protein with a histidine tag at its C terminus. The H-NS truncation mutants were constructed by amplifying fragments from plasmid pSSA2 with the following primers: SSA1 and SSA4 for hns1-46, SSA1 and SSA5 for hns1-64, SSA1 and SSA105 for hns1-80, SSA6 and SSA2 for hns60-137, and SSA7 and SSA2 for hns90-137. All the H-NS truncation fragments were cloned into pET-21b using the restriction sites NdeI and XhoI to incorporate a histidine tag at the C termini of the mutants.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotides used in this studya

| Name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| JMS bglGf | CTGCTGGCGGGGAAAGATAGCGACAAATAATTCACC |

| JMS bglGr | CGCGTTTTTGAAAGCCAATTCCGCGCCCCAT |

| blgG RT 5′ | ACTGGCAATGGTCAGTTAGCGAGA |

| blgG RT 3′ | TTCCTCTTGAGGTGATGGCAACCT |

| gyrB RT 5′ | CACTTTCACGGAAACGACCGCAAT |

| gyrB RT 3′ | TTACCAACAACATTCCGCAGCGTG |

| proV RT 5′ | AATATTTGGCGAGCATCCACAGCG |

| proV RT 3′ | TTTACCCGAGCCGGATAATCCCAT |

| SSA1 | AAAACATATGAGCGAAGCACTTAAAATTCTGAACAACATCC |

| SSA2 | AAAACTCGAGTTCCTTGATCAGGAAATCTTCCAGTTGCTTACC |

| SSA4 | AAAACTCGAGAGCGCTTTCTTCTTCACGACGCTCATTAACG |

| SSA5 | AAAACTCGAGCATTTCACGATACTGTTGCAGTTTACGAGTGCG |

| SSA6 | AAAACATATGCAGTATCGTGAAATGTTAATTGCCGACGGCA |

| SSA7 | AAAACATATGGCAGCTCGTCCGGCTAAATATAGCTATGTT |

| SSA24 | AAAACCATGGCTATGACAAAGAAATTTAAAGTGTCCTTCGACG |

| SSA26 | AAAACCATGGCTATCACTAAGAAATTTAAAGTGTCCTTTGATGTTACC |

| SSA27 | AAAACTCGAGAAGCAGTAATTTCCCAAGCGCCAC |

| SSA30A | GGCAATCTTAGAGAAAGATATGCCGCATCTATGTAAGCAGGTCGG |

| SSA30B | CCGACCTGCTTACATAGATGCGGCATATCTTTCTCTAAGATTGCC |

| SSA105 | AAAACTCGAGAGCCATGCTATTCAGCAGTTCATTCGGGT |

| SSA141 | AAAACTCGAGTCAGAACACCTCCCGTACTGTTGC |

| SSA151 | AAAACCATGGGTATTAACAAACAGTTTCGCG |

| SSA152 | AAAACTCGAGTCACTTAGTCACCCTCACGGTTG |

| SSA153 | AAAACATGTCTAAGATGACCGTTAACGTAAAAG |

| SSA154 | TTTTCTCGAGTTAGCGGAACGTTACCAGAGCC |

| SSA158 | AAAACTCGAGTCATTTGAACACCTCTCGCACAGT |

| SSA159 | AAAACCATGGCTATTACTAAACGTTTTAAAGTATCATTC |

| SSA160 | AAAACTCGAGTTACTTCACCTCACGAATAGTTGCTGG |

| SSA162 | AAAACCATGGCTATTACTAAACGTTTTAAAGTATCATTTG |

| SSA163 | AAAACTCGAGTTACTTCACCTCACGGATAGTTGCTG |

| SSA165 | AAAACACCCATGGCAATGACCAAACAC |

Sequences are oriented from 5′ to 3′. Restriction sites are underlined.

Table 2.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Vector | Description or use | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| pSSA2 | pET21b | Expression of H-NS6His | This study |

| pSSA5 | pET21b | Expression of H-NS1-466His | This study |

| pSSA6 | pET21b | Expression of H-NS1-646His | This study |

| pSSA7 | pET21b | Expression of H-NS60-1376His | This study |

| pSSA8 | pET21b | Expression of H-NS91-1376His | This study |

| pSSA20 | pCDF1b | Expression of T3 5.5 | This study |

| pSSA22 | pET21b | Expression of H-NS1-806His | This study |

| pSSA23 | pCDF1b | Expression of T7 5.5 | This study |

| pSSA26 | pCDF1b | Expression of T7 5.5rbl | This study |

| pSSA27 | pCDF1b | Expression of K11 5.5 | This study |

| pSSA29 | pCDF1b | Expression of Mmp1 5.5 | This study |

| pSSA30 | pCDF1b | Expression of Yersinia phage Berlin 5.5 | This study |

| pSSA31 | pCDF1b | Expression of Kvp1 5.5 | This study |

| pSSA32 | pCDF1b | Expression of φSGJL2 5.5 | This study |

| pWN426 | pHSG576 | Complementation with HA-tagged H-NS | 47 |

To clone the 5.5 gene from phage T7, its coding sequence was amplified from a T7 lysate using primers SSA24 and SSA141. The resulting product was digested with NcoI and XhoI and ligated into the corresponding sites of vector pCDF-1b. Restriction digest with NcoI and XhoI eliminates the histidine tag from the cloning site of pCDF-1b. The plasmid generated, pSSA23, encoded an untagged version of the 5.5 gene, allowing for overexpression of native 5.5T7 protein. The pCDF-1b vector is compatible with pET-expression vectors, facilitating coexpression of 5.5T7 with the histidine-tagged H-NS constructs. Likewise, the 5.5 gene from a bacteriophage T3 lysate was cloned into pCDF-1b vector with primers SSA26 and SSA27. The coding sequences of 5.5 gene homologues from phages φSGJl2 (accession no. gi:189085873), Kvp1 (gi:212671404), Yersinia Berlin (gi:119637767), K11 (gi:194100440), and Mmp1 (gi:194473825) were ordered from GenScript in the vector pUC57 and subcloned into pCDF-1b using the primer pairs SSA158 and SSA165, SSA162 and SSA163, SSA159 and SSA160, SSA151 and SSA152, and SSA153 and SSA154, respectively (Table 1).

Site-directed mutagenesis.

To recreate the previously described (36) 5.5 rbl mutation (leucine at position 30 to proline), site-directed mutagenesis was performed for plasmid pSSA23 using oligonucleotides SSA30A and SSA30B. Plasmid pSSA23 was amplified by PCR with Pfu Ultra Fusion II polymerase (Stratagene) and primers SSA30A and SSA30B. The PCR product was treated with DpnI endonuclease in New England BioLabs buffer 4 for 1 h at 37°C to eliminate the PCR template. The restriction digest was purified using a Qiagen PCR cleanup column, and the resulting plasmid encoding 5.5 with the rbl mutation was transformed into E. coli DH5α. The presence of the rbl mutation was confirmed through DNA sequencing.

ChIP assay.

For chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays, a BL21(DE3) hns mutant strain was generated by P1 transduction from the previously constructed E. coli WN582 strain. Cultures of the BL21(DE3) Δhns mutant harboring plasmids pWN426 (hemagglutinin [HA]-tagged H-NS) and pSSA23 (5.5T7) and the BL21(DE3) Δhns mutant harboring plasmids pWN426 and pSSA26 [5.5T7(rbl)] were grown to mid-logarithmic phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600], 0.4 to 0.6) and induced with 0.1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 1 h. Before and after IPTG induction, samples were treated with 1% formaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature. A small sample was also taken for RNA analysis prior to formaldehyde treatment (see below). The cross-linking reaction was then quenched with 1.25 mM glycine for 10 min. Cells were washed twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and sonicated to generate DNA fragments of ∼500 bp. Cell lysates were precipitated with an anti-HA antibody (Sigma catalog number H3663) using agarose protein G beads (Calbiochem). Real-time quantitative PCR (Q-PCR) analyses of H-NS-interacting DNA samples were performed using Sybr green mix from Bio-Rad according to the manufacturer's instructions. Work with each primer set was done in triplicate.

Reverse transcriptase quantitative PCR.

The induced bacterial cultures (0.5 ml) used for ChIP analysis described above were mixed with 1 ml of RNAprotect bacterial reagent (Qiagen) and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. Subsequent RNA preparations were performed using an Aurum Total RNA minikit (Bio-Rad). Reverse transcription was performed using an iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad) with random hexamer primers. The cDNA generated was used for quantitative real-time PCR analysis as described above. The transcripts of the proV, bglG, and gyrB genes were analyzed by using the primers listed in Table 1 according to gene name. The transcript of the gyrB gene, which is not regulated by H-NS, was used as an internal standard for normalization.

Microarray.

BL21(DE3) harboring a plasmid for expression of gp5.5T7 or a plasmid for expression of H-NS1-64 and BL21(DE3) cultures harboring empty vector controls pCDF-1b and pET-21b were grown to mid-logarithmic phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600], 0.4 to 0.6) and induced with 0.1 mM IPTG for 1 h. Two microliters of induced culture was added to 4 ml of RNAprotect bacterial reagent (Qiagen) and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. Production of labeled cDNA was performed essentially as described previously (10). Briefly, RNA preparations were performed using an Aurum Total RNA minikit (Bio-Rad), and cDNA was synthesized using 25 μg total RNA, 25 μg random nonamer primers, and 400 units of Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). Aminoallyl-dUTP was incorporated into the cDNA by including a 3:2 ratio of aminoallyl-dUTP to dTTP in the reverse transcription reaction. The RNA was hydrolyzed by treatment with NaOH, and the cDNA was purified using Qiagen PCR purification columns. Purified cDNA was reduced to a volume of 3.5 μl in a centrifugal evaporator and labeled with Cy3 and Cy5 monoreactive dye packs from Amersham in a 7-μl reaction mixture. cDNA (2 μg) from BL21(DE3) cultures expressing gp5.5T7 and H-NS1-64 was labeled with Cy5, and cDNA from BL21(DE3) harboring the empty vector controls pCDF-1b and pET-21b was labeled with Cy3. Labeling reactions were quenched with 3.5 μl of 4 M hydroxylamine, and cDNA was purified with a Qiagen PCR purification kit. Cy3- and Cy5-labeled cDNA was reduced to ∼5 μl, and samples were mixed in the following combinations: cDNA from BL21(DE3) cultures expressing gp5.5T7 (Cy5 labeled) with cDNA from BL21(DE3) harboring the pCDF-1b plasmid (Cy3-labeled), and cDNA from BL21(DE3) cultures expressing H-NS1-64 (Cy5 labeled) with cDNA from BL21(DE3) harboring pET21b plasmid (Cy3 labeled). Thirty microliters of 2× GEx Hyb buffer and 4 μl of blocking buffer from the Agilent gene expression hybridization kit were added to the combined cDNA samples. A total of 40 μl of labeled probe/hybridization mixture was hybridized to Agilent's E. coli 8x15k microarrays (Agilent design identification number 020097). The arrays were scanned using a Genepix Professional 4200A scanner. Intensity ratios were acquired using Imagene version 7.5 (Biodiscovery) and Lowess normalized using the R software package from Bioconductor (http://www.bioconductor.org). Significance analysis of microarrays (SAM) (65) was performed for results of three independent experiments using a 1% false-discovery rate (FDR).

Coexpression and purification of gp5.5 homologues with H-NS and H-NS truncation mutants.

All coexpression studies were performed as follows. Plasmids encoding the T7 5.5 protein (pSSA23) and H-NS (pSSA2) were cotransformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) (63). Transformants were selected on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar plates supplemented with 100 μg/ml ampicillin and 50 μg/ml streptomycin. The resulting BL21(DE3) strain carrying plasmids pSSA23 and pSSA2 was cultured at 37°C until an optical density at 600 nm of 0.6 was reached. H-NS and 5.5 expression was induced with 0.1 mM IPTG overnight at 18°C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in cell lysis buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate, 300 mM sodium chloride, 10 mM imidazole, 10 μM β-mercaptoethanol, 5% glycerol [pH 7.0]) and sonicated. The cell lysate was centrifuged at 8,900 rpm in a FiberLite F-13 rotor for 45 min. The supernatant was incubated with Qiagen Ni2+ resin (pre-equilibrated in lysis buffer) for 15 min at 4°C. The Ni2+ resin/cell lysate mixture was applied to a gravity flow column and washed twice with 25 ml ice-cold wash buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate, 300 mM sodium chloride, 30 mM imidazole, 10 μM β-mercaptoethanol, 5% glycerol [pH 7.0]). H-NS and associated 5.5 proteins were then eluted from the column with 5 ml of elution buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate, 300 mM sodium chloride, 250 mM imidazole, 10 μM β-mercaptoethanol, 5% glycerol [pH 7.0]). Fractions were analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

Overexpression and purification of H-NS.

H-NS6His was expressed and nickel column purified from E. coli BL21(DE3) as described above for the coexpression studies, with the exception that the following buffers were used: cell lysis buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate, 300 mM sodium chloride, 10 mM imidazole, 10 μM β-mercaptoethanol, 5% glycerol [pH 8.0]), wash buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate, 300 mM sodium chloride, 30 mM imidazole, 10 μM β-mercaptoethanol, 5% glycerol [pH 8.0]), and elution buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate, 300 mM sodium chloride, 250 mM imidazole, 10 μM β-mercaptoethanol, 5% glycerol [pH 7.0]). The nickel column eluate was treated with DNase I for 30 min at room temperature, diluted 5-fold, and loaded onto a Hi-trapQ (GE Healthcare) anion-exchange column for a secondary purification step. The anion-exchange column was initially equilibrated with buffer A (10 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]), and H-NS was eluted by applying a gradient of 0 to 100% buffer B (10 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 1 M NaCl, 1 mM DTT). H-NS-containing fractions were pooled and buffer exchanged to 10 mM Tris, 50 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT, 5% glycerol, and 2.5 mM EDTA (pH 8.0). The concentration of H-NS was determined by the Bradford method relative to a standard curve for bovine serum albumin (BSA).

Separating 5.5 from H-NS60-137.

Plasmids encoding H-NS60-137 (pSSA7) and gp5.5T7 (pSSA23) were coexpressed and purified by nickel chromatography as described above. SDS-PAGE analysis of the nickel resin purification confirmed that H-NS60-137(6His) copurified with untagged 5.5T7 protein. The elution fraction (containing both H-NS60-137 and gp5.5T7) was concentrated in a centrifugal filter unit (Millipore) to a final volume of 1 ml. The concentrated protein solution was loaded on a Superdex S200 gel filtration column pre-equilibrated with 10 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, and 5% glycerol (pH 7.0). H-NS60-137 and 5.5 coeluted in a single peak at an estimated molecular mass of 90 kDa. Protein-containing fractions from the S200 column were pooled for a third purification step of anion-exchange chromatography. The H-NS60-137/5.5T7 complex was loaded onto a HiTrapQ column in the presence of binding buffer (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.0], 1 mM DTT), and the concentration of the 5.5T7 protein eluted in the absence of H-NS60-137 when the sodium chloride concentration was increased to 700 to 800 mM.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays.

The promoter region of the bglG gene was amplified by PCR from E. coli BL21(DE3) chromosomal DNA with the primer pair JMS bglGf and JMS bglGr. Purified H-NS and 5.5 proteins were combined with 40 ng of gel-purified bglG promoter DNA and binding buffer (15 mM HEPES [pH 8.0], 40 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM DTT, 5% glycerol) in a 20-μl total reaction volume. The mobility shift reaction mixtures were incubated at room temperature for 30 min and combined with 4 μl of Fermentas 6× DNA loading dye. The DNA-protein complexes were separated on a 6% native polyacrylamide gel in the presence of 1× TAE (40 mM Tris acetate, 1 mM EDTA). Electrophoresis was carried out at 70 V for 2 h and 45 min at 4°C. The gels were stained with Sybr green for 20 min at room temperature and visualized with a Typhoon imager.

Gel filtration chromatography.

Purified H-NS, gp5.5T7, and H-NS/gp5.5T7 complex were applied to a Tricorn Superdex 200 10/300 GL column at concentrations of 100 μM, 60 μM, and 100 μM, respectively. All proteins were buffer exchanged into running buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.0], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 5% glycerol) using a HiTrap desalting column (GE Healthcare) prior to loading. The column was equilibrated in running buffer and calibrated by running molecular mass standards that covered the range of 18.2 to 440 kDa.

End-labeling RNA.

To isolate the RNA that copurified with gp5.5T7, a sample of purified 5.5T7 protein was phenol-chloroform extracted, and the aqueous phase (contains nucleic acids) was ethanol precipitated. [32P]pCp 3′ end labeling was carried out in a 20-μl reaction volume with 50 μCi [32P]pCp, 5 μM ethanol-precipitated RNA, 40 units of T4 ligase, and 2 μl of 10× ligase buffer (New England BioLabs). [γ-32P]ATP 5′ end labeling was also carried out in a 20 μl reaction volume with 50 μCi [γ-32P]ATP, 5 μM ethanol-precipitated RNA, 20 units of T4 polynucleotide kinase, and 2 μl of 10× kinase buffer (New England BioLabs). The labeled RNA was separated on an 8% polyacrylamide–8 M urea sequencing gel and exposed to a phosphorimaging screen.

RESULTS

Effects of 5.5 on H-NS/DNA binding and host gene expression in vivo.

H-NS binds more than 400 regions in E. coli to control the expression of more than 500 operons (23, 28, 51). The previous study by Liu and Richardson demonstrated that overexpression of gp5.5T7 tagged with maltose binding protein (MBP) increased expression of the H-NS-repressed osmoregulated proU promoter in vivo, although to levels significantly lower than those observed when wild-type E. coli is placed under conditions of high osmolarity.

To expand upon Liu and Richardson's findings and to determine if gp5.5T7 can displace H-NS from the E. coli chromosome in vivo, we performed ChIP assays followed by quantitative PCR. Genes encoding 5.5T7 or 5.5T7(rbl) were cloned into a pCDF-1b expression vector under the control of a T7 RNA polymerase promoter. The 5.5 proteins encoded on these plasmids were expressed by IPTG induction in an E. coli BL21(DE3) hns mutant harboring a low-copy-number plasmid expressing C-terminally HA epitope-tagged H-NS under the control of its native promoter. Cells were fixed with formaldehyde and sonicated to shear DNA into 500-bp fragments. DNA associated with H-NS was precipitated with an anti-HA antibody. Immunoprecipitation efficiencies (percent recovery after immunoprecipitation compared to initial input) of the bglG and proV genes, which were previously shown to be H-NS regulated, were measured by Q-PCR (Fig. 1 A). As a negative control, the ChIP efficiencies were also measured for the phnE gene, which was previously shown to not bind or be regulated by H-NS.

Fig. 1.

Expression of gp5.5T7 depletes H-NS binding in vivo and induces expression of H-NS-regulated genes. (A) ChIP experiments were performed with the BL21(DE3) Δhns mutant harboring pWN426 (HA-tagged H-NS) and plasmids encoding either gp5.5T7 (dark gray) or gp5.5T7(rbl) (light gray) under the control of an IPTG-inducible promoter. Enrichment of genes previously shown to be regulated by H-NS (the proV and bglG genes) and not regulated by H-NS (the phnE gene) were analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR before (−) and 1 h after IPTG induction of gp5.5T7 expression (+). (B) Transcript levels of the same cultures used for ChIP analysis were determined by reverse transcriptase Q-PCR and normalized to a control transcript (the gyrB gene; see Materials and Methods). Error bars indicate standard deviations, and the numbers above each bar correspond to the values on the y axis (ChIP efficiency or RNA transcript levels).

The ChIP Q-PCR experiments reveal that expression of gp5.5T7 results in the partial but not complete dissociation of H-NS from the bglG and proV promoter sequences. Immunoprecipitation efficiencies for the proV and bglG genes were reduced approximately 2-fold and 3-fold, respectively, in strains expressing gp5.5T7 compared to that from the gp5.5T7(rbl) strain. The immunoprecipitation efficiency of the phnE gene was over 150-fold less than that observed for the proV gene, indicating this sequence was largely not bound by H-NS. It is notable that the enrichment of proV and bglG DNA after expression of gp5.5T7 exceeds that of the phnE gene 200-fold and 50-fold, respectively. We conclude that expression of gp5.5T7 leads to a significant (2- to 3-fold), but not complete, loss of H-NS from the bglG and proV promoter sequences.

Samples from the same cultures used in the ChIP assay were also analyzed for the effects of 5.5 on gene expression using reverse transcriptase Q-PCR (Fig. 1B). Total RNA was purified from strains expressing 5.5T7 and 5.5T7(rbl) and reverse transcribed using random hexamer primers. The cDNA generated was used for Q-PCR analysis with proV- and bglG-specific primers. The gyrB gene, which is unaffected by H-NS, served as an internal control for normalization. proV and bglG transcript levels increased over 2-fold and 5-fold, respectively, in strains expressing gp5.5T7 compared to that for the gp5.5T7(rbl) negative-control strain. These findings are consistent with the ChIP results and indicate that induction of gp5.5T7 expression leads to decreased H-NS binding and increased expression of the H-NS-regulated proV and bglG genes.

It is possible that the effects of gp5.5T7 on the host cell would extend beyond its ability to interact with H-NS and such effects would be missed by a biased sampling of a limited number of genes. To determine the global effects of gp5.5T7 expression on the E. coli transcriptome in an unbiased manner, we employed microarray analysis of E. coli strain BL21(DE3) overexpressing either gp5.5T7 or the H-NS1-64 protein. The latter construct, which contains the N-terminal dimerization domain of H-NS, has been shown to act in a dominant-negative fashion to interfere with H-NS-mediated silencing when overexpressed (66, 68). As such, this construct served as a positive control for antagonism of H-NS activity. RNA isolated 1 h after IPTG induction was labeled and hybridized to a commercial E. coli microarray containing oligonucleotides corresponding to most open reading frames (ORFs). Data were analyzed using a set false-discovery rate (FDR) of 1%, and transcripts were considered affected if they displayed 3-fold or greater changes compared to the plasmid-only control (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

The data indicate that the effects observed by overexpression of the 5.5T7 protein largely parallel the effects observed by overexpression of H-NS1-64. Expression of gp5.5T7 increased steady-state levels of transcripts corresponding to 239 ORFs, including many previously characterized H-NS-repressed loci, such as the gadX (38), bglG (56), csgAB (50), ompF (64), hlyE (70), hdeA and hdeD (71), cadCBA (31), and leuO (30) loci. Two-thirds (159) of the ORFs upregulated by gp5.5T7 were also upregulated in cells overexpressing H-NS1-64. Several of the transcripts that were not categorized as also upregulated by H-NS1-64 were excluded only because of the stringency of our threshold for inclusion. Surprisingly, only seven transcripts were downregulated by expression of gp5.5T7, most of which had relatively mild changes in expression (less than 4-fold). Some of these, including DnaK, DnaJ, and GroES, play a role in protein folding. The reason these genes were expressed is unclear and may be indirect rather than due to the effect of gp5.5T7 on H-NS. Overexpression of H-NS1-64 triggered a broader set of transcriptional changes than that observed with gp5.5T7, with increased levels of transcripts corresponding to 310 ORFs. There were also a larger set of genes (39 total) that displayed lower levels of expression after H-NS1-64 induction, including previously known genes involved in motility. None of these genes corresponded to the genes showing lower expression in the gp5.5T7 data set.

Of the subset of transcripts that were upregulated by gp5.5T7 and that were not affected by H-NS1-64, several were involved in metabolism, including subunits of the F1F0 ATPase (atpEFGH) and NADH dehydrogenase (nuoAB) genes. The mechanism by which several of these genes could be affected by gp5.5T7 expression is unclear and may be indirect. There is some indication that gp5.5T7 expression causes a mild degree of cell stress that is not observed with H-NS1-64. Our microarray analysis revealed that gp5.5T7 induced the upregulated expression of the sulA, minD, and minE genes, which inhibit cell division, and IS1 and IS30, whereas H-NS1-64 did not. There was also mild induction of genes encoded on the DE3 prophage, including the cII protein. Upregulation of the sulE gene is usually driven by the SOS response; however, few other SOS-induced loci were upregulated, indicating that DNA damage is likely not the source of stress caused by gp5.5T7 overexpression. In summary, we conclude that the 5.5T7 protein indeed acts to counter H-NS-mediated repression on a global scale.

5.5 is soluble when coexpressed with H-NS.

Liu and Richardson reported that purification of gp5.5 from coliphage T7 as a soluble protein was difficult and that adequate concentrations of pure protein were only achievable by fusing maltose binding protein (MBP) to the N terminus of the gp5.5T7 coding sequence. In our attempts to isolate pure and soluble 5.5T7 protein, we also found that neither native nor hexahistidine-tagged gp5.5T7 could be expressed as a soluble protein in E. coli under standard expression conditions, including growing the producing strain at a lower temperature. Small quantities of soluble 5.5T7 protein could be obtained when the coding sequence was fused to large N-terminal tags, including SUMO and MBP (data not shown).

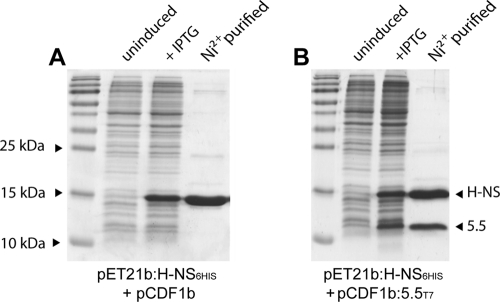

Difficult-to-express proteins are often stabilized when coexpressed with interacting partner proteins. This is true, for example, of the Hha protein, which is largely insoluble unless coexpressed with H-NS (55). We employed a coexpression strategy by cloning the 5.5T7 gene and Salmonella hns genes into the compatible expression vectors pCDF-1b and pET-21b, respectively. The C-terminal end of H-NS was tagged with six-histidyl residues for purification by chromatography over nickel resin, a location for the tag that we have found does not affect the ability of H-NS to bind DNA or functionally complement an hns mutation in vivo (22, 47). Using this approach, we were able to obtain high yields of a soluble gp5.5T7/H-NS complex with an approximate stoichiometry of 1:1, as indicated by Coomassie staining (Fig. 2). Coexpression of the untagged 5.5T7(rbl) protein with H-NS confirmed that no association between the two proteins could be detected and, further, that the 5.5T7(rbl) protein was insoluble while the H-NS protein remained soluble (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

The 5.5T7 protein forms a soluble complex when coexpressed with H-NS containing a C-terminal six-histidyl tag. Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gels of H-NS6His expressed from vector pET-21b purified over nickel resin after coexpression with a control pCDF-1b vector (A) or with gp5.5T7 (B). The lanes include total bacterial protein prior to addition of IPTG (uninduced) and after addition of IPTG (+IPTG) and the eluate after passing cell extracts over nickel column and eluting in the presence of imidazole (Ni2+ purified).

5.5 proteins from several T7-like phages bind H-NS.

Coliphage T7 is a member of the Autographivirinae family of viruses; short-tailed, double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) phages that encode an RNA polymerase necessary for the transcription of phage genes involved in DNA metabolism and phage morphogenesis (2). BLAST and PSI-BLAST (1) searches revealed that gp5.5T7 homologues are found exclusively in the subset of Autographivirinae that infect bacteria of the family Enterobacteriaceae (i.e., the 5.5 gene is absent in those phages that infect Vibrio and Pseudomonas). In all cases, the genomic location of the gp5.5 homologue was highly conserved, residing between the 5 gene, encoding the phage DNA polymerase, and the 6 gene, encoding an exonuclease that liberates deoxynucleotides through degradation of host DNA and suppresses the accidental packaging of host DNA. All 5.5 genes are found immediately upstream of a T7 5.7 gene homologue, often with overlapping start/stop codons. Autographivirinae that do not infect enterobacteria, such as vibriophages VP4 and N4 and Pseudomonas phage gh-1, encode a 5.7 protein without an associated 5.5 gene. The function of the 5.7 gene remains unknown. The 5.5 proteins show an unusually high degree of sequence divergence with only 7 of the approximately 100 residues that are absolutely conserved among the 16 orthologs analyzed. Pairwise alignments of each gp5.5 homologue to all of the others reveals that they share, on average, only 47% identity (range, 95% to 24%). In contrast, the products of the nearby 5, 5.7, and 6 genes are also highly conserved, with an average amino acid identity between homologues of 77%, 84%, and 69%, respectively, similar to the conservation among most proteins that are common to all Autographivirinae.

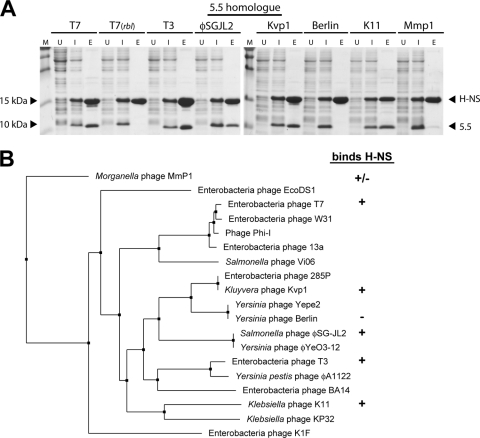

Given the large sequence divergence observed for 5.5 proteins, it was of interest to determine if the ability to bind H-NS is a conserved feature of these proteins. Toward this end, the coexpression/interaction assay described previously was employed to measure the interactions between H-NS and the 5.5 proteins of a number of Autographivirinae, including coliphage T3, Salmonella phage φSG-JL2, Kluyvera phage Kvp1, Yersinia phage Berlin, Klebsiella phage K11, and Morganella phage Mmp1 (Fig. 3 A). These gp5.5 orthologs were selected to obtain a diverse sample set of 5.5 proteins that each varied significantly in sequence from one another according to our phylogenetic analysis (Fig. 3B). With the exception of gp5.5 from Yersinia phage Berlin, all of the proteins tested copurified with Salmonella H-NS. The 5.5 protein from Morganella phage Mmp1 (Mmp1_gp28), which is highly divergent from 5.5T7, interacted with H-NS only weakly. Control experiments in which the 5.5 homologues were expressed in the absence of H-NS demonstrated that these proteins have no affinity for nickel resin and, to various degrees, are insoluble in the absence of H-NS. These experiments indicate that despite the fairly low degree of conservation, the ability to interact with H-NS is a property widely conserved among the 5.5 proteins.

Fig. 3.

Diverse 5.5 proteins from various Autographivirinae bind H-NS. (A) Full-length H-NS6His was coexpressed in strains of E. coli BL21(DE3), each containing a plasmid with a gp5.5 homologue as indicated on top. The ability of the two proteins to interact was assessed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie after copurification using nickel chromatography. Lane labels: M, molecular mass marker; U, uninduced, cell lysate prior to induction with IPTG; I, induced, cell lysate after induction of protein synthesis by IPTG; E, eluate after nickel chromatography. (B) Results of the interaction assay in panel A are shown next to a nearest-neighbor tree of the various gp5.5 homologues. Symbols indicate whether the indicated gp5.5 homologue binds (+), does not bind (−), or displays strongly diminished binding (+/−) to H-NS.

The 5.5T7 protein interacts with the central linker domain of H-NS.

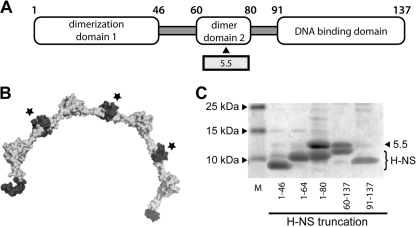

The H-NS protein is 137 amino acid residues long and contains three functional domains (59, 66). The N-terminal domain contains a large coiled-coil region responsible for dimerization and interaction with the Hha and YdgT corepressor proteins (Fig. 4 A). The C-terminal domain from amino acids 91 to 137 contains the DNA binding activity. The central region, located between residues 46 and 90, was thought to be a “flexible linker” important for association of H-NS molecules into higher-order oligomeric states. A recent structural study has revealed that the linker region harbors a second dimerization domain contained within residues 60 and 80 that enables H-NS to multimerize in a head-to-head/tail-to-tail fashion to generate an extended helical scaffold for DNA binding (Fig. 4B) (2). To determine the region of H-NS that interacts with the 5.5T7 protein, gp5.5T7 was coexpressed with a series of H-NS deletion mutants, each of which were tagged at the C terminus with six-histidine residues. gp5.5T7/H-NS complex formation was assessed by the ability of the 5.5T7 protein to copurify with the various H-NS6His truncations during purification over nickel resin (Fig. 4C). No significant association of the 5.5T7 protein was observed with either the N-terminal dimerization domain (residues 1 to 46 or 1 to 64) or the C-terminal DNA binding domain (residues 91 to 137). In contrast, the 5.5T7 protein associated tightly with constructs containing residues 60 to 137 and 1 to 80 of H-NS. The results indicate that gp5.5T7 associates with a region of H-NS contained between residues 60 and 80, corresponding to the recently identified central dimerization domain.

Fig. 4.

5.5T7 protein binds the central H-NS dimerization domain contained within residues 60 to 80. (A) Diagram of the H-NS molecule showing the approximate boundaries of each distinct domain within H-NS. (B) Structure of H-NS helical multimer (8 H-NS monomers) as recently solved by Arold et al. (2). The central dimerization domains that interact with gp5.5T7 are shown in dark gray and indicated with a star. (C) Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE of the interaction between gp5.5T7 and various H-NS6His truncations after coexpression and purification over nickel resin. The positions of gp5.5T7 and various H-NS truncations are indicated.

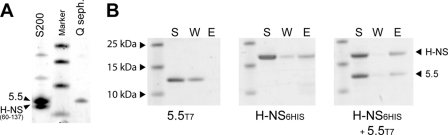

Isolation of pure 5.5 as a soluble and functional protein from H-NS60-137.

Purification of H-NS6His alone or with gp5.5T7 over nickel resin yields partially pure preparations that were contaminated with small amounts of other proteins and DNA. A multistep purification protocol was developed that would consistently yield substantial quantities of the gp5.5T7/H-NS complex that were sufficiently pure to use in downstream studies. This procedure included DNase treatment of cleared cell lysates, purification of complex over nickel resin, a second round of chromatography over Q-Sepharose, and a final purification/buffer exchange by gel filtration. During the purification of gp5.5T7 in complex with various truncation mutants, we serendipitously found that the 5.5T7 protein would dissociate from H-NS60-137 in a soluble form during chromatography over Q-Sepharose when concentrations of NaCl reached approximately 700 mM (Fig. 5 A). The identity of the purified protein band observed on SDS-PAGE as 5.5T7 was verified by N-terminal protein sequencing by Edman degradation.

Fig. 5.

Purification of gp5.5T7 as a soluble and active protein by dissociation from H-NS60-137. (A) SDS-PAGE of eluted fractions of coexpressed gp5.5T7 after gel filtration chromatography on a Hiload 16-60 Superdex S200 prep grade column and after ion-exchange chromatography over a HitrapQ fast flow column (Q Sepharose.). (B) Purified gp5.5T7 was applied to nickel resin either in the absence (left panel) or presence (right panel) of H-NS6His and association was assessed. The central panel shows H-NS6His in association with nickel resin in the absence of gp5.5T7. Lanes: S, supernatant, sample prior to loading onto nickel resin; W, wash fraction; E, eluate after nickel chromatography.

To determine if the soluble 5.5T7 protein was functional and retained its ability to bind H-NS, we employed an on-column association assay (Fig. 5B). Pure 5.5T7 protein was mixed with purified H-NS6His prior to chromatography over nickel resin. Purified 5.5T7 protein alone was unable to associate with the nickel resin and eluted off the resin during the wash step. When gp5.5T7 and tagged H-NS6His were mixed together, the 5.5T7 protein was retained on the column but coeluted with the H-NS protein upon the addition of imidazole. This result indicated that the purified 5.5T7 protein retained its ability to interact with the H-NS protein after isolation through this procedure.

The 5.5 protein disrupts higher-order H-NS-DNA complexes.

The effects of the soluble 5.5T7 protein on the ability of H-NS to interact with DNA in vitro were assessed using an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) (Fig. 6). Several independent laboratories have observed that H-NS exhibits strongly cooperative binding behavior, in which multiple sites on target DNA are occupied over a very narrow range, resulting in a low-mobility H-NS/DNA complex. Purified H-NS protein was mixed with PCR-generated DNA fragments containing the promoter of the bglG gene, previously demonstrated to be regulated by H-NS. Consistent with previous reports, the addition of 500 μM protein H-NS led to complete shifting of this DNA fragment into a low-mobility protein/DNA complex. Addition of purified gp5.5T7 at increasing ratios with H-NS, ranging from 1:1 to 10:1, caused decreased shifting of the DNA-H-NS complex. However, at no concentration was complete displacement of H-NS from the DNA observed. No effect on DNA mobility was observed by the addition of gp5.5T7 in the absence of H-NS.

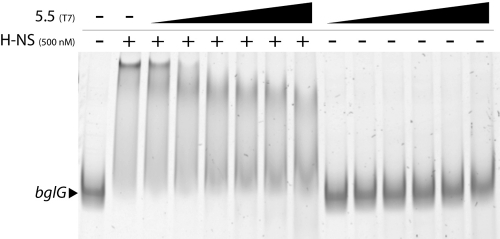

Fig. 6.

Purified 5.5T7 protein disrupts higher-order H-NS/DNA complexes in vitro. A 423-bp fragment of the bglG promoter region was incubated with 500 nM H-NS and increasing concentrations of gp5.5T7 (500 nM, 1,000 nM, 1,500 nM, 2,000 nM, 2,500 nM, and 5,000 nM). The amount of bglG DNA in each reaction was 10 nM. 5.5T7 was incubated with bglG DNA in the absence of H-NS at 500 nM, 1,000 nM, 1,500 nM, 2,000 nM, 2,500 nM, and 5,000 nM. Reactions were then separated on 6% acrylamide gels which were run at 4°C. + and − represent the presence and absence, respectively, of the indicated protein.

H-NS is known to form higher-order oligomers spontaneously in solution at sufficiently high concentrations that can be observed by changes in the elution profile during gel filtration chromatography (3). The apparent masses of H-NS, gp5.5T7, and the gp5.5T7/H-NS complex were tested using a Sephacryl S200 column that was calibrated with a set of globular proteins of known sizes (Table 3). At a concentration of 100 μM, H-NS (monomer mass, ∼15.5 kDa) elutes from the column with an apparent mass of 132 kDa, indicative of an octomer or nonamer. The average oligomer size is likely to be lower, however, given the elongated structure of H-NS oligomers. H-NS copurified with gp5.5T7 as a complex, when adjusted to a concentration of 100 μM, displayed an apparent mass of 163 kDa, which was larger than that of H-NS alone. Isolated gp5.5T7 protein, which has a predicted monomer mass of 11 kDa, elutes with an apparent mass of 146 kDa, which indicates that it may also exist as a higher-order multimer. The order of the oligomerization state of gp5.5T7 is confounded by its association with RNA (see below).

Table 3.

Gel filtration of H-NS, gp5.5T7, and the H-NS/gp5.5T7 complex

| Protein | Elution profilea |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Concn (μM) | Monomer wt (kDa) | Calculated mass (kDa) | |

| H-NS | 100 | 15.5 | 132 |

| H-NS/gp5.5 | 100 | 163 | |

| gp5.5 | 60 | 11 | 146 |

Calculated mass from Tricorn Superdex 200 10/300 GL that was calibrated immediately prior to use with ribonulease (13.7 kDa), ovalbumin (43 kDa), conalbumin (75 kDa), aldolase (158 kDa), and ferritin (440 kDa), a set of globular proteins with elution profiles that correlate well with mass.

The EMSA results are consistent with what we observed with ChIP analysis in vivo and support a model whereby gp5.5T7 binding results in an alteration in the structure of oligomerized H-NS but does not directly interfere with the ability of H-NS to bind DNA. The results by gel filtration also suggest that the 5.5T7 protein does not trigger dissociation of multimers into monomers or dimers, although these results are inconclusive. The observed smearing pattern of the protein-DNA complex is likely caused by decreased stability of the H-NS/DNA during electrophoresis due to a disruption in cooperative binding. A similar smearing pattern has been observed with EMSAs using oligomerization-defective mutants of a Pseudomonas H-NS analog, MvaT (8).

The 5.5 protein copurifies with tRNA.

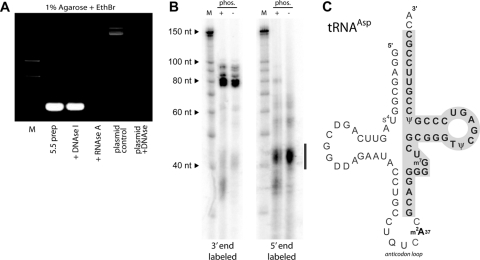

During the purification of gp5.5T7 and subsequent attempts to characterize its stoichiometry, we noted that the molecule displayed very strong absorbance at 260 nm. During EMSA experiments, we noted the presence of a low-molecular-weight nucleic acid species, running near the dye front, that was present only in lanes to which the purified 5.5T7 protein had been added. Further analysis revealed that the small nucleic acid was copurifying with gp5.5T7 through multiple chromatographic steps, including nickel chromatography (in complex with H-NS), Q-Sepharose (at which point the H-NS protein dissociates from gp5.5T7), and two rounds of gel filtration. The copurifying nucleic acid was also observed when gp5.5T7 was coexpressed with the H-NS1-80 construct that lacks the DNA binding domain, indicating that the nucleic acid was not copurifying due to an interaction with the DNA binding domain of H-NS (data not shown). The copurifying nucleic acid was extracted from gp5.5T7 with phenol and subjected to digestion with DNase I or RNaseA (Fig. 7 A). The results demonstrate that the nucleic acid copurifying with gp5.5T7 is RNA and not DNA. Attempts to remove this RNA from the 5.5T7 protein by treatment with RNase caused rapid aggregation of the 5.5T7 protein, suggesting that the RNA was critical to maintain gp5.5T7 solubility (data not shown).

Fig. 7.

The 5.5 protein copurifies with tRNA. (A) After purification by gel filtration chromatography, associated nucleic acid was removed by phenol-choloroform extraction (5.5 preparation) and subsequently treated with DNase I or RNaseA as indicated. The plasmid control shown in the final two lanes demonstrates the activity of the DNase I used in the assay. (B) End labeling of isolated RNA reveals that it is heterogeneous and labels poorly at its 5′ end. Copurifying low-molecular-weight RNA was end labeled at the 3′ end with [32P]pCp and RNA ligase or at the 5′ end with [γ-32P]ATP using T4 polynucleotide kinase. The bar adjacent to the autoradiogram indicates the low-abundance (as determined by Sybr stain), presumably degraded, RNA that was efficiently labeled by PNK. (C) Diagram of tRNAAsp showing, boxed and in bold, the segment obtained by cloning after reverse transcription of in vitro-polyadenylated RNA. Similar truncated clones were obtained from tRNAAla and tRNAThr. EthBr, ethidium bromide; nt, nucleotides.

A sequencing resolution acrylamide gel of the 3′-radiolabeled copurifying RNA indicated it was heterogeneous and composed of at least four major species with sizes ranging from approximately 75 to 95 nucleotides (Fig. 7B). The two most prominent species corresponded to approximately 77 and 82 nucleotides in length. Additional species present in smaller amounts were approximately 86 to 95 nucleotides in length. Multiple attempts using various linker-ligation cloning strategies were made to identify the sequences of the copurifying RNA, but no clones were obtained. Subsequent analysis of the copurifying RNA revealed that it was poorly amenable to radiolabeling at the 5′ end by T4 polynucleotide kinase (PNK) but that the 3′ ends could be labeled readily with [32P]pCp using T4 RNA ligase. We correspondingly altered the cloning strategy by extending the 3′ end with a poly(A) tail using poly(A) polymerase followed by reverse transcription an oligo(dT) primer and ligation of the resulting product with an adaptor prior to cloning. By using this method, multiple clones containing fragments corresponding to 34 to 38 nucleotides of the 3′ ends of tRNAAla (encoded by the alaX gene), tRNAThr (thrW), and tRNAAsp (aspT, aspU, or aspV) were isolated. Less abundant RNAs, presumably degradation products, were much more readily labeled with T4 PNK (Fig. 7B).

Taken together, the data indicate that the predominant copurifying nucleic acids are a heterogeneous mix of mature tRNAs and less abundant larger precursor forms prior to processing by host RNAses. The sizes of the various RNA molecules are similar to those expected of tRNA (76 to 77 nucleotides) or tRNA precursors. The difficulties encountered in obtaining full-length clones are most likely due to strong secondary structure and the presence of modified nucleotides in tRNA that hindered ligation of linkers to the 5′ end and blocked primer extension steps by DNA/RNA polymerases. The poor radiolabeling of the 5′ end of the full-length RNA molecule by T4 PNK is entirely consistent with previous observations regarding the poor equilibrium constants observed when tRNA is labeled with this enzyme (33, 34). The clones that were obtained were likely derived from incomplete reverse transcription that was blocked by modified nucleotides contained within the anticodon loop (e.g., m2A37 in tRNAAsp) (Fig. 7C).

DISCUSSION

Since the discovery in 1993 that the 5.5T7 protein copurified with H-NS, the mechanism by which these two proteins interact and the effects of the interaction on phage infection have remained unexplored. Here, we extend the previous observations and find that 5.5 proteins of several T7-like phages interact with H-NS despite their fairly large sequence divergence. We further find that gp5.5T7 targets the recently described central dimerization domain of H-NS contained within residues 60 to 80. We have developed a method of purification of soluble 5.5 protein that retains H-NS binding activity that has enabled us to analyze its effects on H-NS DNA binding in vitro. The EMSA and gel filtration results support a role of 5.5 in disrupting proper nucleoprotein structure without perturbing DNA binding. This is entirely consistent with our finding that gp5.5T7 interacts with the domain involved in higher-order structuring but not with the DNA binding or primary dimerization domain. The EMSA results are also in agreement with chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments showing limited depletion of H-NS caused by gp5.5T7 overexpression at bglG and proV promoters in vivo. It is of note that our EMSA results differ from the previous observations of Liu and Richardson, who paradoxically observed increased shifting (i.e., supershifting) of H-NS/DNA complexes upon the addition of MBP-5.5T7. This may be due to the fact that the protein used in those studies contained a very large N-terminal addition that altered mobility or failed to fully disrupt the H-NS/DNA complex in vitro under the conditions used.

H-NS silences gene expression primarily through promoter occlusion, polymerase trapping, and constraining supercoils, although the relative contributions of each can vary at different promoters (46). Accordingly, there are a large number of mechanisms described by which H-NS-mediated silencing can be relieved to enable gene expression (45, 61). These include direct competition for binding sites by sequence-specific DNA binding proteins and reorganization of the nucleoid structure in response to temperature such that H-NS fails to halt transcription. Apart from gp5.5T7, only one other molecule, H-NST, found on pathogenicity islands encoded near the serU gene of some pathogenic strains of E. coli, is known to antagonize H-NS by interfering with multimerization (4, 69). H-NST is highly homologous to the first 80 amino acids of H-NS and acts in a dominant-negative fashion, presumably through interactions with both the N-terminal and central dimerization domains. The critical role that the fine higher-order structure of the H-NS-DNA complex plays in gene silencing is further highlighted by recent findings that Ler, an H-NS like protein that activates rather than represses gene expression, adopts a nucleoprotein structure distinct from the elongated filaments formed by H-NS (41, 42). One notable aspect of our microarray study is that expression of gp5.5T7 and H-NS1-64 triggered gene expression changes that correlated strongly but not perfectly. Differences observed in gene expression between the two constructs employed may be due to differences in levels of expression or activity (i.e., we did not obtain equivalent levels of H-NS inhibition, which is difficult to calibrate under the experimental setup used in these studies). It is also likely that the mechanism by which gp5.5T7 and H-NS1-64 antagonize H-NS are not identical and, therefore, that these proteins affect different promoters to different degrees. This notion is consistent with previous findings that alterations in higher-order structure have a greater effect on the expression of some promoters than others. For example, several mutations in H-NS that relieve silencing of the proV gene but that have no effect on the expression of the bglG gene have been identified (66). For most alleles, the underlying reason for the observed differences remains unclear. For example, it was shown that a truncated H-NS molecule lacking a DNA binding domain required an association with the H-NS paralog StpA for repression of the bglG gene. However, this association was insufficient to repress the proV gene and was only relevant when the truncated H-NS was expressed at low levels (21).

The phylogenetic distribution of gp5.5T7 orthologs revealed that these proteins are exclusively found in Autographivirinae that infect enterobacteria. Homologues of gp5.5T7 are notably absent in the few members of this family that infect Vibrio and Pseudomonas. This may well correlate to the fact that members of the family Pseudomonadaceae harbor xenogeneic silencing proteins, MvaT and MvaU, that bear no similarity to H-NS (9). The H-NS molecules of Vibrio spp. are also quite distinct from those of the enteric bacteria, most notably with regard to their mechanism of oligomerization, and they possess almost no similarity to enteric H-NS in the region corresponding to the central oligomerization domain (49). The second dimerization domain of Yersinia H-NS differs by three residues from that of Salmonella and E. coli, and this may account for the inability of gp5.5 from Yersinia phage Berlin to bind H-NS from Salmonella. For these reasons, analogs of the 5.5 protein present in Autographivirinae from nonenteric bacteria, if they exist, might have diverged extensively from the 5.5 proteins to the point where they cannot be identified by sequence similarity.

Despite the fact that 5.5T7 protein is believed to accumulate to very high levels during the course of infection, phage T7 5.5rbl mutants have no phenotype in most E. coli wild-type laboratory strains, and the role of this factor in the phage life cycle remains unclear (62). Genes present in phage genomes are usually clustered according to function, and one clue with regard to the 5.5 protein may be its invariant genetic linkage with the 5, 5.7 and 6 genes. These genes are transcribed by the T7 RNA polymerase within 6 min of infection and are clustered with genes involved in replication and packaging of phage DNA. A speculative model proposed by Liu and Richardson, that release of H-NS during degradation of the host genome is detrimental to phage replication, seems unlikely, since T7 5.5rbl mutants grow normally in strains of E. coli that have intact H-NS (35). Furthermore, the T7 genome is not notably AT-rich except in the proximity of the late promoters that direct T7 RNAP to transcribe genes involved in phage morphogenesis. It is possible that a primary role of the gp5.5/H-NS complex is to enable T7 growth on lambda lysogens, but the fact that the 5.5T7 amber mutant does not display an rbl phenotype indicates that the mechanism may be complex.

The association of gp5.5T7 with heterogeneous tRNA after multiple chromatography steps was unexpected and points to a possible avenue of investigation regarding its role during phage infection. gp5.5T7 carries an overall positive charge (pI, ∼7.9) and it remains possible that the association of the protein with RNA is not specific. However, we have also observed that gp5.5T3 also copurifies with low-molecular-weight RNA despite low conservation of sequence and a net negative charge (pI, ∼5.4; data not shown). It has previously been demonstrated that during phage T4 infection, tRNALys is cleaved by a host-encoded anticodon nuclease, PrrC, in an effort to block phage replication by shutting down translation (29, 40, 54). Wild-type T4, however, encodes a polynucleotide kinase and tRNA ligase that repairs the cleaved tRNA, tipping control of translation back in favor of the phage. In this light, it is possible that the interaction of gp5.5T7 with tRNA is in some way related to gaining control of the host translational apparatus to the advantage of the phage and that this phenotype occurs only in certain strains of E. coli. It is also possible that tRNA is not the physiologically relevant RNA substrate during phage infection and that it adventitiously copurified with gp5.5T7 due to its high abundance in the cell. Other potential RNA substrates that have strong secondary structure that would be relevant to phage infection include CRISPR-associated RNAs and recently identified antiviral RNA components of some toxin-antitoxin systems (6, 7, 13, 39). Determining the relevance of H-NS and, possibly, RNA in the function of the 5.5T7 protein will require a better understanding of the conditions under which gp5.5T7 is important for the phage life cycle. Our future efforts will be focused in that direction.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Alan Davidson, Karen Maxwell, and Rick Collins for helpful discussions and technical support. We are grateful to Blair Gordon and Harm Van Bakel for assistance with the microarray studies. We thank Robin Imperial for the generation of the 5.5 expression construct. Phage T7 and T3 were obtained from the Félix d'Hérelle Reference Center for Bacterial Viruses (http://www.phage.ulaval.ca).

The Navarre laboratory is supported by an Operating Grant and New Investigator Award from the Canada Institutes for Health Research (MOP-86683 and MSH-87729) and a Discovery Grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (RGPIN 386286-10). S.S.A. is supported by a graduate fellowship from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 15 July 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Altschul S. F., et al. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arold S. T., Leonard P. G., Parkinson G. N., Ladbury J. E. 2010. H-NS forms a superhelical protein scaffold for DNA condensation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:15728–15732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Badaut C., et al. 2002. The degree of oligomerization of the H-NS nucleoid structuring protein is related to specific binding to DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 277:41657–41666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baños R. C., Pons J. I., Madrid C., Juárez A. 2008. A global modulatory role for the Yersinia enterocolitica H-NS protein. Microbiology 154:1281–1289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Benzer S. 1955. Fine structure of a genetic region in bacteriophage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 41:344–354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Blower T., et al. 2009. Mutagenesis and functional characterization of the RNA and protein components of the toxIN abortive infection and toxin-antitoxin locus of Erwinia. J. Bacteriol. 191:6029–6039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Blower T. R., et al. 2011. A processed noncoding RNA regulates an altruistic bacterial antiviral system. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 18:185–190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Castang S., Dove S. L. 2010. High-order oligomerization is required for the function of the H-NS family member MvaT in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 78:916–931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Castang S., McManus H. R., Turner K. H., Dove S. L. 2008. H-NS family members function coordinately in an opportunistic pathogen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:18947–18952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Charity J. C., et al. 2007. Twin RNA polymerase-associated proteins control virulence gene expression in Francisella tularensis. PLoS Pathog. 3:e84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dame R. T., et al. 2005. DNA bridging: a property shared among H-NS-like proteins. J. Bacteriol. 187:1845–1848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dame R. T., Wyman C., Wurm R., Wagner R., Goosen N. 2002. Structural basis for H-NS-mediated trapping of RNA polymerase in the open initiation complex at the rrnB P1. J. Biol. Chem. 277:2146–2150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Deltcheva E., et al. 2011. CRISPR RNA maturation by trans-encoded small RNA and host factor RNase III. Nature 471:602–607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dillon S. C., et al. 2010. Genome-wide analysis of the H-NS and Sfh regulatory networks in Salmonella Typhimurium identifies a plasmid-encoded transcription silencing mechanism. Mol. Microbiol. 76:1250–1265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dorman C. J. 2007. H-NS, the genome sentinel. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5:157–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Doyle M., et al. 2007. An H-NS-like stealth protein aids horizontal DNA transmission in bacteria. Science 315:251–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Duckworth D. H., Garrity R. R., McCorquodale D. J., Pinkerton T. C. 1983. Inhibition of T7 bacteriophage replication by a colicin Ib plasmid gene. Virology 131:259–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Duckworth D. H., Glenn J., McCorquodale D. J. 1981. Inhibition of bacteriophage replication by extrachromosomal genetic elements. Microbiol. Rev. 45:52–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Duckworth D. H., Pinkerton T. C. 1988. ColIb plasmid genes that inhibit the replication of T5 and T7 bacteriophage. Plasmid 20:182–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fang F. C., Rimsky S. 2008. New insights into transcriptional regulation by H-NS. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 11:113–120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Free A., Porter M. E., Deighan P., Dorman C. J. 2001. Requirement for the molecular adapter function of StpA at the Escherichia coli bgl promoter depends upon the level of truncated H-NS protein. Mol. Microbiol. 42:903–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gordon B. R., Imperial R., Wang L., Navarre W. W., Liu J. 2008. Lsr2 of Mycobacterium represents a novel class of H-NS-like proteins. J. Bacteriol. 190:7052–7059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Grainger D. C., Hurd D., Goldberg M. D., Busby S. J. 2006. Association of nucleoid proteins with coding and non-coding segments of the Escherichia coli genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 34:4642–4652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hardy C. D., Cozzarelli N. R. 2005. A genetic selection for supercoiling mutants of Escherichia coli reveals proteins implicated in chromosome structure. Mol. Microbiol. 57:1636–1652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Higgins C. F., et al. 1990. Protein H1: a role for chromatin structure in the regulation of bacterial gene expression and virulence? Mol. Microbiol. 4:2007–2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hoskisson P. A., Smith M. C. M. 2007. Hypervariation and phase variation in the bacteriophage ‘resistome.’ Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 10:396–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hyman P., Abedon S. T. 2010. Bacteriophage host range and bacterial resistance. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 70:217–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kahramanoglou C., et al. 2011. Direct and indirect effects of H-NS and Fis on global gene expression control in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 39:2073–2091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kaufmann G. 2000. Anticodon nucleases. Trends Biochem. Sci. 25:70–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Klauck E., Böhringer J., Hengge-Aronis R. 1997. The LysR-like regulator LeuO in Escherichia coli is involved in the translational regulation of rpoS by affecting the expression of the small regulatory DsrA-RNA. Mol. Microbiol. 25:559–569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kuper C., Jung K. 2005. CadC-mediated activation of the cadBA promoter in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 10:26–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Labrie S. J., Samson J. E., Moineau S. 2010. Bacteriophage resistance mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8:317–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lillehaug J. R., Kleppe K. 1975. Kinetics and specificity of T4 polynucleotide kinase. Biochemistry 14:1221–1225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lillehaug J. R., Kleppe K. 1977. Phosphorylation of tRNA by T4 polynucleotide kinase. Nucleic Acids Res. 4:373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lin L. 1992. Study of bacteriophage T7 gene 5.9 and gene 5.5. Ph.D. thesis. State University of New York at Stony Brook, Stony Brook, NY [Google Scholar]

- 36. Liu Q., Richardson C. C. 1993. Gene 5.5 protein of bacteriophage T7 inhibits the nucleoid protein H-NS of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 90:1761–1765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Liu Y., Chen H., Kenney L. J., Yan J. 2010. A divalent switch drives H-NS/DNA-binding conformations between stiffening and bridging modes. Genes Dev. 24:339–344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ma Z., Richard H., Tucker D. L., Conway T., Foster J. W. 2002. Collaborative regulation of Escherichia coli glutamate-dependent acid resistance by two AraC-like regulators, GadX and GadW (YhiW). J. Bacteriol. 184:7001–7012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Marraffini L. A., Sontheimer E. J. 2010. CRISPR interference: RNA-directed adaptive immunity in bacteria and archaea. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11:181–190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Masaki H., Ogawa T. 2002. The modes of action of colicins E5 and D, and related cytotoxic tRNases. Biochimie 84:433–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mellies J. L., et al. 2011. Ler of pathogenic Escherichia coli forms toroidal protein-DNA complexes. Microbiology 157:1123–1133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mellies J. L., et al. 2008. Ler interdomain linker is essential for anti-silencing activity in enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Microbiology 154:3624–3638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mojica F. J., Higgins C. F. 1997. In vivo supercoiling of plasmid and chromosomal DNA in an Escherichia coli hns mutant. J. Bacteriol. 179:3528–3533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Molineux I. J., Schmitt C. K., Condreay J. P. 1989. Mutants of bacteriophage T7 that escape F restriction. J. Mol. Biol. 207:563–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Navarre W., McClelland M., Libby S., Fang F. 2007. Silencing of xenogeneic DNA by H-NS-facilitation of lateral gene transfer in bacteria by a defense system that recognizes foreign DNA. Genes Dev. 21:1456–1471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Navarre W. W. 2010. H-NS as a defence system, p. 251–322 In Dame R. T., Dorman C. J. (ed.), Bacterial chromatin. Springer Verlag, Heidelberg, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 47. Navarre W. W., et al. 2006. Selective silencing of foreign DNA with low GC content by the H-NS protein in Salmonella. Science 313:236–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Noom M. C., Navarre W. W., Oshima T., Wuite G. J. L., Dame R. T. 2007. H-NS promotes looped domain formation in the bacterial chromosome. Curr. Biol. 17:R913–R914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nye M. B., Taylor R. K. 2003. Vibrio cholerae H-NS domain structure and function with respect to transcriptional repression of ToxR regulon genes reveals differences among H-NS family members. Mol. Microbiol. 50:427–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Olsén A., Arnqvist A., Hammar M., Sukupolvi S., Normark S. 1993. The RpoS sigma factor relieves H-NS-mediated transcriptional repression of csgA, the subunit gene of fibronectin-binding curli in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 7:523–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Oshima T., Ishikawa S., Kurokawa K., Aiba H., Ogasawara N. 2006. Escherichia coli histone-like protein H-NS preferentially binds to horizontally acquired DNA in association with RNA polymerase. DNA Res. 13:141–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Pao C. C., Speyer J. F. 1975. Mutants of T7 bacteriophage inhibited by lambda prophage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 72:3642–3646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Parma D. H., et al. 1992. The Rex system of bacteriophage lambda: tolerance and altruistic cell death. Genes Dev. 6:497–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Penner M., Morad I., Snyder L., Kaufmann G. 1995. Phage T4-coded Stp: double-edged effector of coupled DNA and tRNA-restriction systems. J. Mol. Biol. 249:857–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Pons J. I., Rodriguez S., Madrid C., Juarez A., Nieto J. M. 2004. In vivo increase of solubility of overexpressed Hha protein by tandem expression with interacting protein H-NS. Protein Expr. Purif. 35:293–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Schnetz K. 1995. Silencing of Escherichia coli bgl promoter by flanking sequence elements. EMBO J. 14:2545–2550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Schroder O., Wagner R. 2000. The bacterial DNA-binding protein H-NS represses rRNA transcription by trapping RNA polymerase in the initiation complex. J. Mol. Biol. 298:737–748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Skennerton C. T., et al. 2011. Phage encoded H-NS: a potential Achilles heel in the bacterial defence system. PLoS One 6:e20095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Smyth C. P., et al. 2000. Oligomerization of the chromatin-structuring protein H-NS. Mol. Microbiol. 36:962–972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Stella S., Spurio R., Falconi M., Pon C. L., Gualerzi C. O. 2005. Nature and mechanism of the in vivo oligomerization of nucleoid protein H-NS. EMBO J. 24:2896–2905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Stoebel D. M., Free A., Dorman C. J. 2008. Anti-silencing: overcoming H-NS-mediated repression of transcription in Gram-negative enteric bacteria. Microbiology 154:2533–2545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Studier F. W. 1981. Identification and mapping of five new genes in bacteriophage T7. J. Mol. Biol. 153:493–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Studier F. W., Rosenberg A. H., Dunn J. J., Dubendorff J. W. 1990. Use of T7 RNA polymerase to direct expression of cloned genes. Methods Enzymol. 185:60–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Suzuki T., Ueguchi C., Mizuno T. 1996. H-NS regulates OmpF expression through micF antisense RNA in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 178:3650–3653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Tusher V. G., Tibshirani R., Chu G. 2001. Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:5116–5121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ueguchi C., Suzuki T., Yoshida T., Tanaka K., Mizuno T. 1996. Systematic mutational analysis revealing the functional domain organization of Escherichia coli nucleoid protein H-NS. J. Mol. Biol. 263:149–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Walthers D., et al. 2011. Salmonella enterica response regulator SsrB relieves H-NS silencing by displacing H-NS bound in polymerization mode and directly activates transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 286:1895–1902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Williams R. M., Rimsky S., Buc H. 1996. Probing the structure, function, and interactions of the Escherichia coli H-NS and StpA proteins by using dominant negative derivatives. J. Bacteriol. 178:4335–4343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Williamson H. S., Free A. 2005. A truncated H-NS-like protein from enteropathogenic Escherichia coli acts as an H-NS antagonist. Mol. Microbiol. 55:808–827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Wyborn N. R., et al. 2004. Regulation of Escherichia coli hemolysin E expression by H-NS and Salmonella SlyA. J. Bacteriol. 186:1620–1628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Yoshida T., Ueguchi C., Mizuno T. 1993. Physical map location of a set of Escherichia coli genes (hde) whose expression is affected by the nucleoid protein H-NS. J. Bacteriol. 175:7747–7748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.