Abstract

In adaptation biology the discovery of intracellular osmolyte molecules that in some cases reach molar levels, raises questions of how they influence protein thermodynamics. We’ve addressed such questions using the premise that from atomic coordinates, the transfer free energy of a native protein (ΔGtr,N) can be predicted by summing measured water-to-osmolyte transfer free energies of the protein’s solvent exposed side chain and backbone component parts. ΔGtr,D is predicted using a self avoiding random coil model for the protein, and ΔGtr,D − ΔGtr,N, predicts the m-value, a quantity that measures the osmolyte effect on the N ⇌ D transition. Using literature and newly measured m-values we show 1:1 correspondence between predicted and measured m-values covering a range of 12 kcal/mol/M in protein stability for 46 proteins and 9 different osmolytes. Osmolytes present a range of side chain and backbone effects on N and D solubility and protein stability key to their biological roles.

Keywords: osmolyte, folding, protein stability, m-value, solubility, urea

1. Introduction

The Gibbs Conference began with the goals of promoting thermodynamics as a powerful discipline in molecular biophysics, and as a means to develop the careers of junior colleagues whose research continues to broaden the scope and application of thermodynamics to the solution of biological problems. Throughout the past 25 years the Gibbs Conference played an important role in the education and career development of graduate and postdoctoral students from our laboratory, and it served as a stimulating proving ground and clearing house for ideas and concept development so essential to progress. It is difficult to imagine how this laboratory would have progressed without the advantage of the high-level discussions experienced at the Gibbs Conference. In fact, the research to be described here has its origins in discussions that began at an early Conference. As the following report illustrates, thermodynamics is built upon solid foundations laid by early practitioners whose clarity of thought and ideas have a life of their own. Sometimes it takes unexpected events and findings and viewing the problem from a very different angle to rejuvenate the original idea and bring it to the point of realization. Such is the case with protein folding/unfolding and osmolytes.

The biology of adaptation has many facets [1], but none are so fascinating to solution biophysicists as organic osmolytes. The signature role of these small organic molecules is to manage cell volume regulation under water-stress conditions that may include extremes of temperatures, extremes of pressure, changes in extracellular osmotic conditions, desiccation, or even the intracellular presence of the protein denaturing osmolyte, urea [2–5]. Such water-stress conditions are commonly encountered in the biosphere and threaten cell volume maintenance either through the removal or increase of cellular water. To maintain cell volume, the loss or gain in cell water is mitigated by cellular control mechanisms that increase or decrease intracellular concentrations of small organic molecules, which act osmotically to return the cell volume toward normal[1]. Accordingly, these physiologically important compounds are called osmolytes, and their action as osmoticants is the principal osmolyte property of note.

But action as an osmoticant is not the only property of an osmolyte that can help cell systems or organisms cope with the particular water stress imposed [1]. In addition to osmotic stress, many of the water stresses listed above also cause protein denaturation, so osmolytes that have the property of protecting proteins against denaturation provide additional protection to the organism or cellular system [6–11]. In addition, varying intracellular concentrations of small organic molecules can potentially affect intracellular protein solubility by means of their osmophobic effect [12–14], so particular organic osmolytes with properties useful in obviating protein solubility problems also help the organism or cellular system cope with specific water stress situations. ”Osmophobicity” [14] and how it is modulated is discussed in detail below for various types of osmolytes. In essence, there are three major chemical classes of osmolytes that protect organisms of the plant, animal, and archaea kingdoms [3]; polyols and sugars, methyl amines, and certain amino acids. In addition, there is one denaturing osmolyte, urea, that presents a unique set of issues in urea-rich cells [2, 15]. Our long-range objective has been to uncover those osmolyte properties that enable these four classes of osmolytes to deal with the particular water-stress, and provide physiological roles related to protein solubility and protein stability. This is the subject of this report.

The strategy we adopted is to determine the free energy of interactions between various osmolyte solutions and solvent-exposed protein groups that comprise the protein structure. This strategy is based on the hypothesis that it is possible to successfully model protein free energy on transfer to osmolyte solutions if both the free energy of each chemical type of surface element (backbone and the various side-chain types), and the degree of exposure of each element is known. To test this hypothesis, the task is then threefold, viz.

measure the energetics of appropriate model compounds that mimic protein chemical components,

calculate the overall transfer free energy of a protein species by weighting each chemical component’s free energy (from point 1) with the degree of its solvent exposure, and

compare the results with experimental data on these proteins.

The experimental approach to point 1 has its roots in the early work of Edwin Cohn and John Edsall, essential elements of which appeared in one of the earliest monographs on biophysical chemistry, ”Amino Acids, Peptides, and Proteins” [16]. Lewis & Randall [17] presented the principle that at the solubility limits of a crystalline organic compound in water and in a second solution (e.g. osmolyte solution), the chemical potential of the compound is equivalent in the two solutions (see note added in proof). From this, Cohn and Edsall developed a simple method for determining the transfer free energy of the organic compound from water to the second solution. Much later, Tanford used this method to determine transfer free energies of amino acids from water to urea (and other) solutions [18]. Tanford subtracted the transfer free energy of glycine from all other amino acids, and the resulting free energy differences were taken to represent the water to urea transfer free energies of each of the amino acid side-chains. We adapted his methods for use in the studies presented here, and we significantly extended the number of investigated osmolytes [7, 19, 20] in addition to resolving some issues with the backbone models that Tanford used [20–23].

To calculate the transfer free energy of a protein (point 2 in the list above), it is necessary to weight the contribution of each protein surface element (represented by model compound energetics) to the extent that the groups are exposed in protein native and denatured states. This procedure necessitates knowledge of the structure of the protein. Since we are dealing with transitions, such as unfolding, both native and denatured state solvent accessibilities must be known. For the native state, we use atomic coordinates from crystal structures. The denatured state is represented by the average exposures obtained in a self-avoiding random coil [24–27]. In terms of transfer free energy, this model is half way between a random coil in a good solvent and the compact denatured state defined by Creamer, Srinivasan and Rose [25, 27]. The details of calculating native and denatured state transfer free energies are given briefly in the supplement and are extensively described elsewhere [21–23].

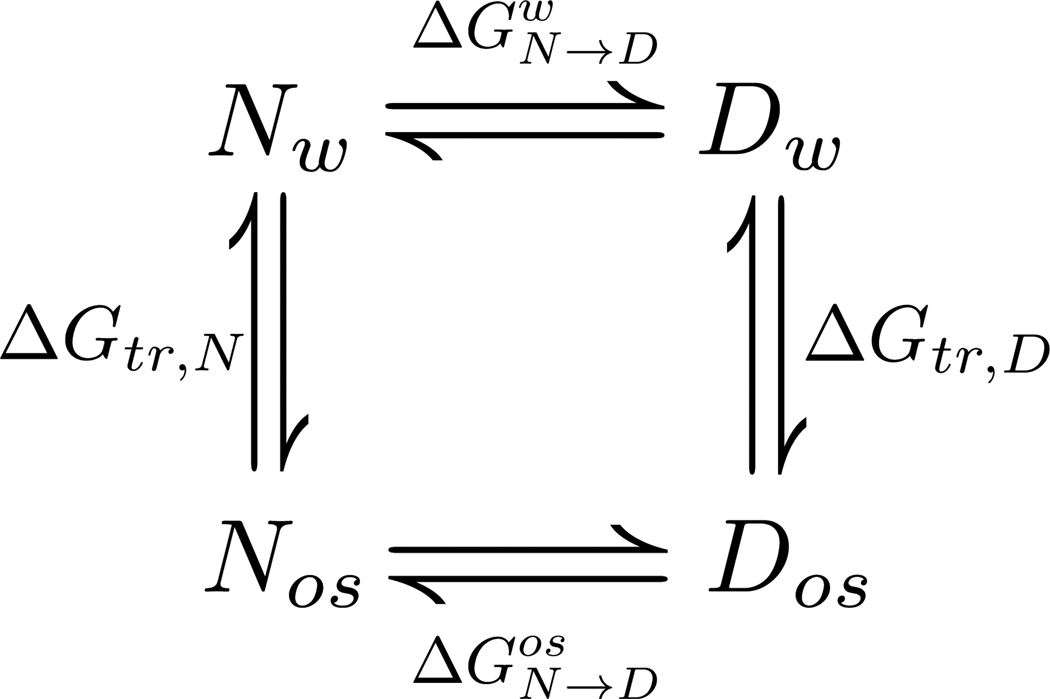

Subsequent comparison of these calculations with experiment (point 3) involves the application of Tanford’s transfer model [28], which is shown in Figure 1. It is a thermodynamic strategy for evaluating the free energy change of the overall folding or unfolding transition of proteins in terms of the residue specific participants. What is typically obtained in an experiment is the stability of a protein. The free energy change in the transition from native to denatured in water alone is at the top of the thermodynamic cycle (Figure 1), while the corresponding equilibrium below it occurs in the presence of 1M osmolyte. The free energy difference, can be obtained readily from various experimental approaches, such as urea induced denaturation in the absence or presence of other osmolytes, thermal unfolding in presence of osmolytes, or forced folding of intrinsically unstructured proteins by protecting osmolytes [13, 29–33]. ΔΔG is equal to the slope (m-value) of the osmolyte dependent protein stability; it has units of kcal/mol/M and is a measure of the efficacy of a given osmolyte to either force proteins to fold (protecting osmolytes) or to unfold (denaturing osmolyte, urea). The m-value is a free energy quantity and because we want its sign to express whether the N ⇌ D transition is favorable or unfavorable, we use eq. 1 which differs in sign from that traditionally used [29].

| (1) |

Figure 1. Transfer Model.

Shown is a thermodynamic cycle involving (un)folding transitions between native and denatured protein in water (Nw and Dw) or osmolyte solution (Nos and Dos), as well as the transfer of native or denatured protein from water to the osmolyte solution.

The vertical equilibria in Figure 1 represent the free energy change upon transfer of native and denatured states from water to 1M osmolyte ΔGtr,N and ΔGtr,D; and these are the free energies obtained from the calculations (point 2). The transfer free energies of N and D complete the thermodynamic cycle, resulting in the relationship, . The right hand side of this equation represents the predicted transfer free energy difference between native and denatured states, whereas the left hand side represents the experimental m-value.

Thus this equality provides a means to test the transfer model in terms of the premise that one should be able to predict experimentally determined m-values provided that 1) accurate transfer free energies of the backbone unit and amino acid side-chains are known for any given osmolyte solution, 2) the native state structure of a protein is known, 3) the solvent accessible surface area model used for the denatured state is appropriate, and 4) most importantly, the assumption of additivity holds. These four conditions are essential for successful implementation of the transfer model. Only when all of the conditions are fulfilled are the predictions expected to be successful for a broad range of proteins. The results presented below indicate that these conditions are indeed fulfilled. Moreover, because the thermodynamics are constructed from residue specific contributions of protein groups at the amino-acid level, a successful prediction provides unprecedented detail of the driving forces responsible for protein folding/unfolding [21, 23] as well as protein solubility [34] in the presence of osmolytes. This provides the basis for our detailed discussion below of the significant role of amino acid side-chains in the case of some osmolytes.

2. Results

2.1. Test of the transfer model through m-value predictions

Over the course of osmolyte studies in our lab, we have collected complete sets of backbone and side-chain transfer free energies determined at 25°C for nine naturally occurring osmolytes, including the protecting osmolytes, trimethylamine-oxide (TMAO), sarcosine (N-methylglycine), glycine betaine (N,N,N-trimethylglycine), proline, glycerol, sorbitol, sucrose, trehalose and the denaturing osmolyte, urea [7, 12, 19–23, 35]. During this time, we and others have thoroughly investigated the effects of these osmolytes on protein transitions. After collecting experimentally determined m-values from the literature and from our own studies, we generated a database of 48 proteins (see Supplemental Table S1) for which to test the transfer model prediction. These proteins for which atomic coordinates are available are monomeric, without ligands, and are reported to undergo reversible two-state unfolding. A number of methods [33] have been used here to obtain m-values for these proteins, including urea denaturation of structurally stable proteins in the presence and absence of protecting osmolytes, thermal unfolding of structurally stable proteins in the presence of osmolytes, and osmolyte-induced forced folding of intrinsically unstructured proteins.

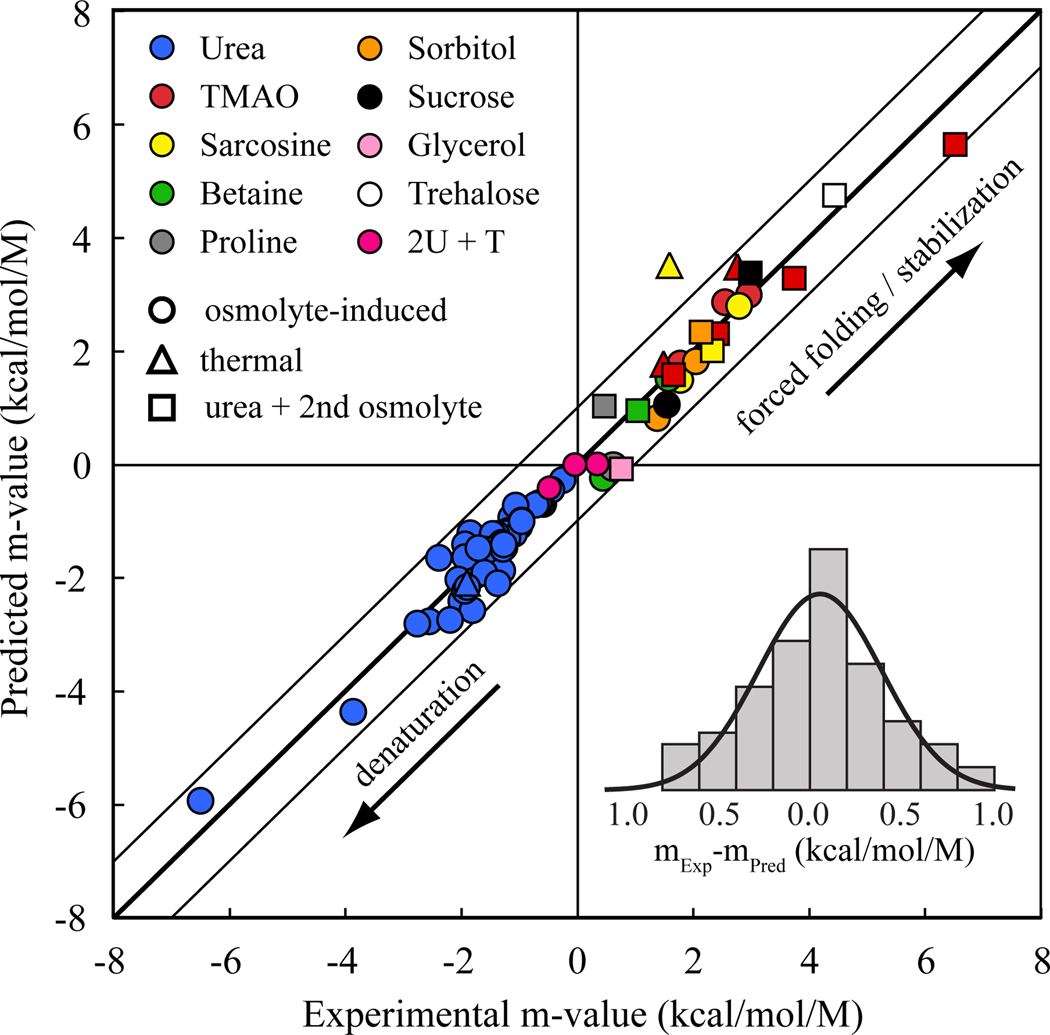

Using the transfer model, we calculated the m-values of these proteins for the transfer from water to 1M osmolyte and Figure 2 compares the predicted m-values (ordinate) with the experimental m-values (abscissa) for each of these nine osmolytes. In total, there are 73 data points plotted, since several proteins have been studied in the presence of several osmolytes. The experimental protein m-values range up to ~ +6 kcal/mol/M for protecting osmolytes (upper right quadrant) and down to ~ −6 kcal/mol/M for the denaturing osmolyte, urea (lower left quadrant), resulting in a complete range of ~ 12 kcal/mol/M. The constraint for a perfect prediction is that all data fall on the identity line of unity slope with an intercept of zero.

Figure 2. Comparison of predicted m-values with experimental m-values.

73 experimental data points of m-values calculated from pdb files are plotted versus their experimental values. Some experimental data were taken from the literature, and some measured using the methods described in Methods (see also supplementary Table S1). The m-values span a range of about 12 kcal/mol/M. The best fit of a straight line to the data is statistically indistinguishable from the identity line (thick diagonal line). The thin diagonal lines serve as a guide to the eye, representing deviations of ± 1 kcal/mol/M from the identity line. Almost all data fall within this limit. The distribution of the data around the identity line is shown as a histogram, with an overlaid gaussian distribution. Key: Colors indicate the osmolyte, while the symbol shapes indicate the method of determining the m-value.

The inset of Figure 2 shows a histogram of the difference between experimental and predicted m-values with the corresponding probability distribution function. The gaussian distribution is centered on approximately zero, corresponding to the identity line, with a mean = 0.055 ± 0.022 kcal/mol/M and standard deviation = 0.336 kcal/mol/M. Thus, 68% of the data fall within ±0.34 kcal/mol/M of the identity line and 95% of the data fall within ±0.68 kcal/mol/M of the identity line. These standard deviations are, in many cases, comparable to the error associated with the experimentally determined m-values. However, it is evident that m-values of some proteins deviate from the identity line, and this could result from a variety of factors including deviation from two-state behavior, deviation of the denatured state from the self-avoiding random coil model, some degree of non-additivity and inaccuracies in the group transfer free energies or in experimental m-values. Lack of additivity from surface patches of net charge that could interfere with group independence does not seem to be a major factor [36, 37]. Potential inaccuracies in the group transfer free energies have been addressed for urea by proper data treatment [23] and are in general agreement with conclusions regarding urea-backbone interactions drawn by others [38, 39]. However, the principal cause for the scatter of the data around the identity line is likely to be the denatured state structure. It is known that the compactness of the denatured state depends both on the osmolyte used [12, 40], and on the type of protein [41].

Despite the observed deviations between prediction and measurement, the exceptional one-to-one agreement over a 12 kcal/mol/M range in stability for nine different osmolytes ensures that the transfer model is robust and predictive. On the strength of the agreement in Figure 2, we assessed the relative roles of backbone and side-chains of proteins in solutions of the various osmolytes.

2.2. Residue specific contributions to the stability and the solubility of protein native and denatured states

Rather than a ”top-down” approach, which derives average thermodynamic properties from the study of whole proteins, the transfer model is ”bottom-up” in that it is predictive of a thermodynamic property of proteins based solely on the physical chemical properties of amino acids and peptides in solution. As such, its predictive success provides a unique opportunity to identify residue specific properties of osmolyte interactions with protein native and denatured states that comprise the overall effect on protein stability and solubility. In fact, the transfer model has its historic roots in the principle of solubility where an increase in the solubility of an amino acid or peptide upon transfer from water to osmolyte solution defines a favorable interaction (−Δgtr) between the solute and osmolyte and a decrease in solubility upon transfer corresponds to an unfavorable interaction (+Δgtr). When these group contributions are summed for protein native and denatured states, a net favorable interaction will increase protein solubility and a net unfavorable interaction will decrease solubility.

In terms of the stability and solubility of proteins we first consider the effects of two counteracting osmolytes commonly found in sharks and rays: urea, which forces proteins to unfold [42], and TMAO, which forces proteins to fold [2, 13]. Afterward, we examine the effects of glycine betaine, proline and glycerol whose roles in biology do not require strong effects on protein stability. Instead, they serve primarily as osmoticants and preserve protein function, stability and solubility in response to the osmotic stress [10]. To consider how different osmolytes affect transfer free energies of N and D states as a function of amino acid composition and protein molecular weight, we predict ΔGtr,N, ΔGtr,D, and m-values for a multitude of proteins from the Protein Databank.

The Urea - TMAO Counteraction Paradigm

For purposes of illustration, we examine the effects of these osmolytes on Nank4 − 7*, a segment of notch ankyrin protein containing the tandem repeats 4 to 7 of the Drosophila Notch Receptor with two internal cysteines replaced with serines [30]. This particular protein is special in that at 34°C and pH 7 it is poised at the midpoint of the native to denatured transition, allowing evaluation of the m-values of counteracting osmolytes alone or in combination. The experimental and calculated m-values for the effects of the osmolytes, TMAO, sarcosine, glycine betaine, urea, and the combination of are given in Table 1 for Nank4 − 7* as well as Nank1 − 7* and Barnase. As expected, there is good agreement between the predicted and experimentally determined m-values for the pure osmolyte solutions. The mixture of two parts urea to one part TMAO, such that the total osmolyte concentration is 1M, represents an important facet of the urea-TMAO counteraction paradigm with respect to protein stability. The rationale for using the 2:1 ratio is that it is found in elasmobranchs [2, 43]. Here, we have calculated from the experimental m-values the ΔΔG stability change of these proteins in the presence of by using eq. 2 (see Methods). Similarly, from the predicted m-values derived from transfer free energies, we have taken one-third of the value for urea and two-thirds of the value for TMAO. The results of the comparison, show that 1) the urea:TMAO mixture has very little effect on the stability of these proteins and 2) the transfer model illustrates that TMAO completely counteracts the effects of urea on protein stability at the 2:1 urea:TMAO ratio found in sharks and Rays. This is not surprising because it is well established that the efficacy of urea-induced protein unfolding is independent of the presence or absence of protecting osmolyte, and vice versa [6, 30, 32]. That is, the effects of urea:protecting osmolyte mixtures on protein stability are additive.

Table 1. Experimental and predicted m-values for three example proteins.

Various methods were employed: urea-induced denaturation (UD), urea-induced denaturation in the presence of added osmolyte (UD+O), and thermal unfolding in the presence of added osmolyte (TU)

| Protein | Osmolyte |

mExperim. |

mPredicted |

Experimental Method |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nank4 − 7* | Sarcosine | 2.73 | 2.80 | UD + O | [32] |

| Betaine | 1.49 | 1.52 | TU | This work | |

| TMAO | 3.74 | 3.28 | UD + O | [30] | |

| Urea | −1.94 | −1.64 | UD | [32] | |

| 2:1 Urea:TMAO | −0.045 | 0.001 | (mTMAO +2mUrea)/3 | [30] | |

| Nank1 − 7* | TMAO | 6.52 | 5.64 | UD + O | [30] |

| Urea | −2.75 | −2.81 | UD | [30] | |

| 2:1 Urea:TMAO | 0.34 | 0.007 | (mTMAO +2mUrea)/3 | [30] | |

| Barnase | TMAO | 1.66 | 1.59 | UD + O | [30] |

| Urea | −1.55 | −1.41 | UD | [30] | |

| 2:1 Urea:TMAO | −0.48 | −0.41 | (mTMAO +2mUrea)/3 | [30] | |

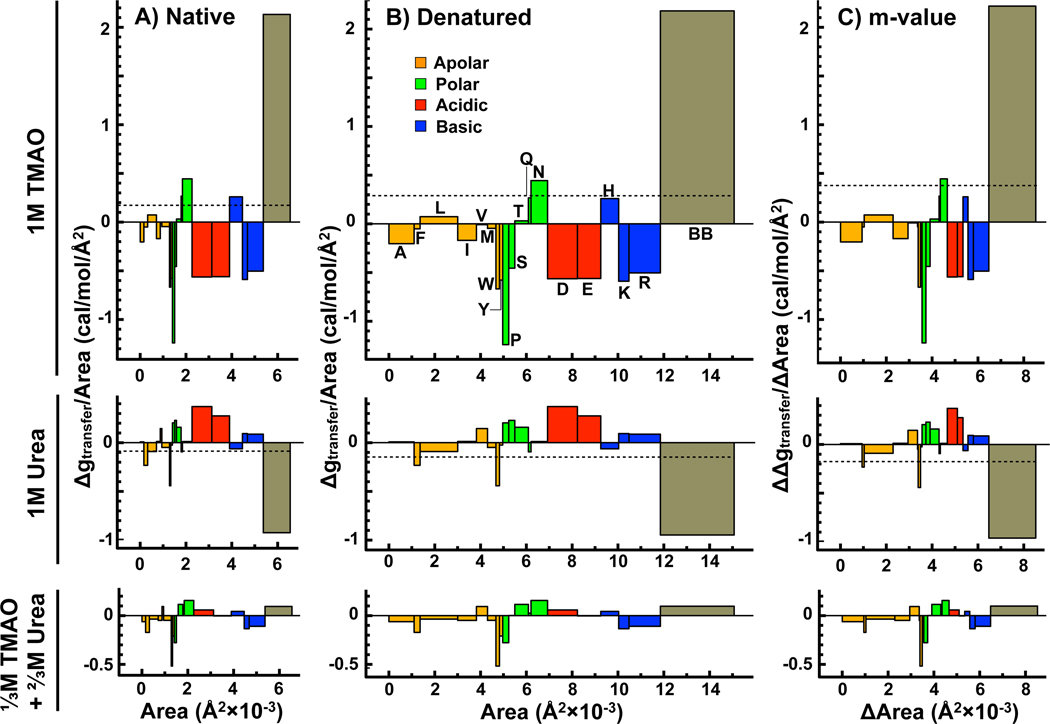

A detailed perspective of the urea-TMAO counteraction is obtained from a residue-level accounting of the backbone and side-chain free energy contributions to the native and denatured states of Nank4 − 7* and the m-value for transfer to 1M TMAO, 1M urea, and the 2:1 mixture of Urea:TMAO. Figure 3A and B shows transfer free energies per protein surface area, Δgtr/Area, versus the exposed surface area of native and denatured states. These group-wise free energy contributions are illustrated as blocks of different areas for each of the side-chains and the backbone. The area of each block represents the free energy contribution of the indicated protein group. The algebraic sum over all block areas given by the dashed lines represent the net transfer free energy per Å2 of the native and denatured states. Figure 3C illustrates the group-wise free energy contributions to the m-value (ΔΔgtr/ΔArea) as a function of the surface area that becomes buried upon folding or exposed upon unfolding (ΔArea) and the algebraic sum of these contributions is the m-value (ΔGtr,D − ΔGtr,N).

Figure 3.

Side-chain and backbone contributions to ΔGtr,N (panel A), ΔGtr,D (panel B) and the m-value (panel C) of Nank4 − 7* from buffer to 1M TMAO (top), 1M urea (middle) and the 2:1 mixture of urea to TMAO equal to unit molarity (bottom). Side-chain and backbone transfer free energy contributions divided by the corresponding surface areas exposed in the native and denatured state (Δgtr/Area) are plotted as a function of those solvent exposed surface areas. Side-chain and backbone contributions to the m-value divided by their respective contributions to ΔArea as a function of total surface area newly buried upon forced folding or exposed upon unfolding. The net transfer free energy per Å2 for native, denatured and overall m-value are shown as dashed lines. Amino acid side-chain contributions are labeled according to their single letter abbreviation and colored by class as indicated in panel B (top) and their order on the abscissa is preserved in all panels of this figure. For ease of comparison, the scale of both the ordinate and abscissa in all panels are equal. (Colors: Web only)

In the case of TMAO, the side-chain contributions to the transfer of N and D and to the m-value vary according to side-chain type, exhibiting different magnitudes and signs; however, collectively they are favorable to transfer (a net −Δgtr). In contrast, the large unfavorable interaction between backbone and TMAO dominates the collectively favorable side-chain transfer free energies of N and D states from water to 1M TMAO. This raises the free energy of both the N and D states and results in a net positive m-value. It is clear that in the presence of TMAO, the protein will be forced to fold, driven by the unfavorable interaction with backbone. In addition, the net unfavorable interactions between N and D states and TMAO, the osmophobic effect, will necessarily decrease the solubilities of these species in the presence of TMAO relative to that of water.

Upon transfer to urea solution the free energies of protein component parts are opposite in sign from that observed with TMAO. The side-chain contributions are both positive and negative, but collectively they are unfavorable to transfer from water to 1M urea. The large favorable interaction between backbone and urea dominates the (collective) unfavorable side-chain interactions with urea, lowering the free energy of both the N and D states, and resulting in a net negative m-value. So, the favorable interactions with the backbone are the reason that the protein will denature in the presence of urea. [7, 23, 38, 39, 44]. Also, the net favorable interactions between N and D states and urea will necessarily increase the solubilities of these species in the presence of urea relative to that of water.

In the case of the 2:1 urea:TMAO mixture, the net contribution of both side-chains and backbone are small. As a result, the m-value is also close to zero, showing that urea and TMAO completely counteract one another under these conditions. Because the net transfer free energies of N and D states from water to the 2:1 mixture are both close to zero, the N and D states in the mixture will have about the same solubility they would have in buffer alone.

A similarity in the pattern of effects by these two opposing osmolytes is that in both cases, side-chains oppose the shift in N to D equilibrium induced by the osmolyte; that shift is driven by the sign and magnitude of the free energy effect of the osmolyte on the peptide backbone. Quantitatively, on a per Å2 basis, the unfavorable TMAO-backbone interaction is approximately twice the magnitude of the favorable urea-backbone interaction [20] and because the opposing side-chain contributions are relatively small by comparison, the counteracting effects of a 2:1 molar ratio of urea to TMAO on protein stability is in large part due to the backbone.

Betaine, Proline and Glycerol

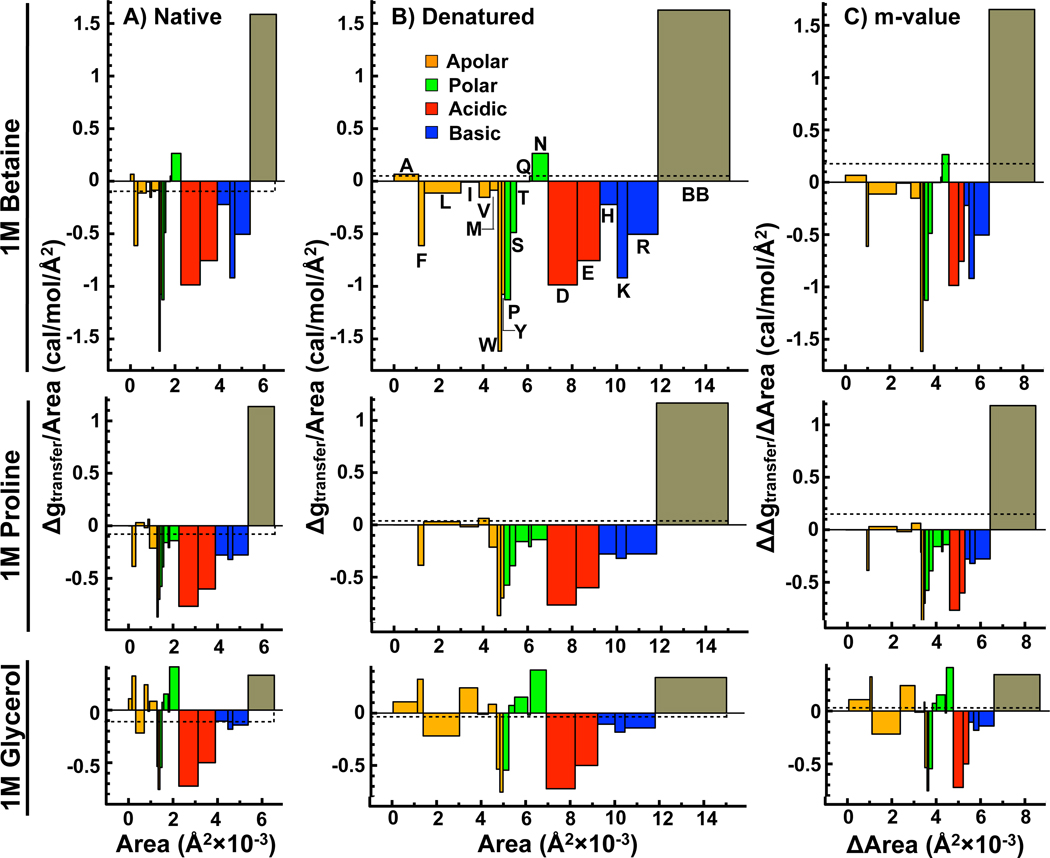

For glycine betaine, proline and glycerol, the contributions of the side-chains rival those of the backbone, which is in marked contrast to both urea and TMAO. Figure 4 illustrates the competing interactions of side-chain and backbone with these osmolytes using the block plots of the group-wise free energy contributions in Nank4 − 7*.

Figure 4.

Side-chain and backbone contributions to ΔGtr,N (panel A), ΔGtr,D (panel B) and the m-value (panel C) of Nank4 − 7* from buffer to 1M glycine betaine (top), 1M proline (middle) and 1M glycerol (bottom). See Figure 3 for details. (Colors: Web only)

In the case of glycine betaine, the backbone contribution is still quite large and unfavorable, but the net favorable contributions of the side-chains slightly dominate in the native state. As a result, glycine betaine lowers the free energy of the native state of Nank4 − 7* by ~ −600 cal/mol/M (a solubilizing effect). In contrast, this osmolyte raises the free energy of the denatured state by ~ 900 cal/mol/M due to a slight dominance of the backbone over side-chains. As a result of the opposite effects of glycine betaine on the N and D states, the native state is favored in the presence of glycine betaine with an m-value equal to ~ 1500 cal/mol/M. Proline also behaves similarly to glycine betaine with nearly equivalent opposing favorable side-chain and unfavorable backbone contributions, only the magnitudes of these contributions are smaller than for glycine betaine. Lowering the free energy of the N state through favorable interactions with side-chains while increasing the free energy of the D state through unfavorable interactions with the backbone has the dual benefit of solubilizing the protein native state while at the same time conferring stability to the protein.

The interaction of glycerol with Nank4 − 7* is different from either glycine betaine or proline. While the backbone contribution is unfavorable, it is weak, and collectively the stronger favorable contributions of the side-chains out-compete the backbone. This results in a nearly equivalent reduction in the free energies of both the N and D states and an m-value close to zero. Lowering the free energy of both the N and D states by an equal amount will necessarily increase the solubility of both these species in the presence of glycerol relative to water.

2.3. Average effects of osmolytes on protein stability and solubility

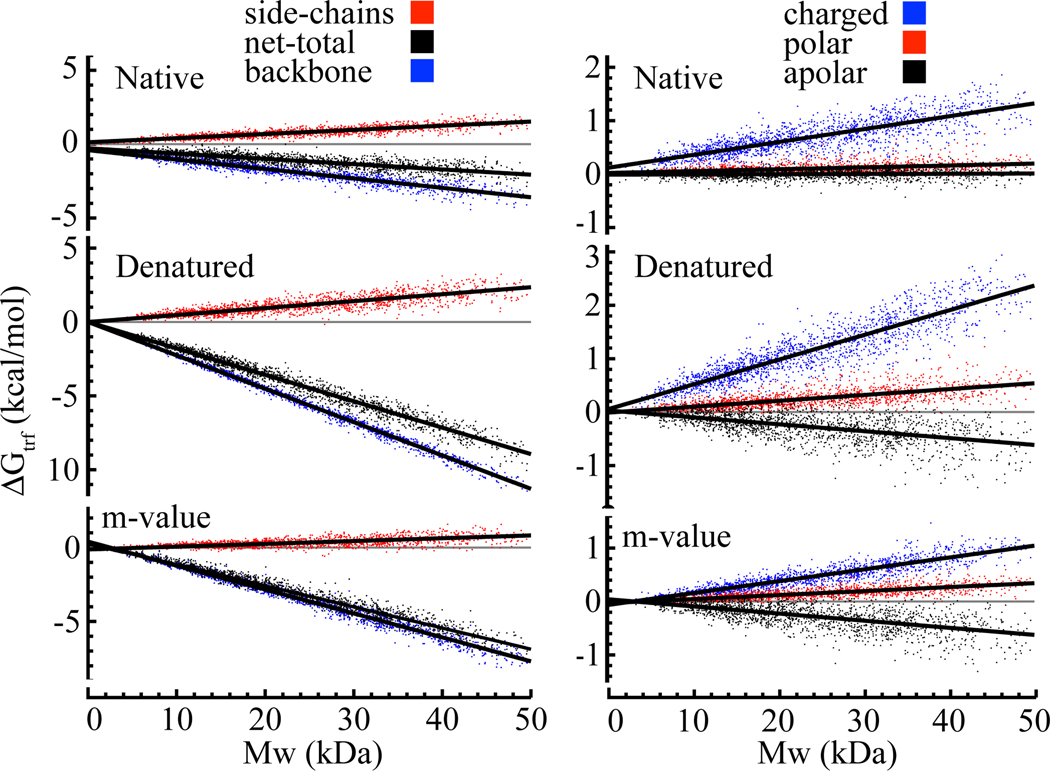

Up to this point, Nank4 − 7* is used as a specific example to assess the residue specific contributions to stability and solubility of native and denatured states. The question is how general these conclusions are with respect to other proteins. To address this issue, we extracted ~ 1800 structures from the Protein Databank ranging up to 50 kD in molecular weight according to the criteria stated in the methods and calculated the transfer free energies of the N and D states and the m-value. (A 50 kD protein is about the maximum size for which an accurate m-value can be determined experimentally.) The data generated from these proteins were plotted as a function of molecular weight and fit to a linear regression. Plots of the backbone, side-chain, and net total transfer free energies of the native and denatured states and the m-value along with a breakdown of the side-chain contributions into charged, polar and apolar classes as a function of the molecular weight of the protein are given in Figure 5 for urea. Plots for other osmolytes are provided as Supplemental Figures S1–S9. These proteins may or may not undergo two-state unfolding, electron density for parts of some proteins may be missing, and they may not all be globular proteins. However, even with these uncertainties that undoubtedly contribute to data scatter, it is possible to consider the overall effects on protein stability and solubility. In order to distill the information contained in these supplemental figures succinctly, we have taken the slope ∂ΔGtr/∂MW of these plots as a metric for establishing generalizations concerning the average effects of osmolytes on the stability and solubility of proteins.

Figure 5. Calculated transfer free energy of proteins of various size to 1M Urea.

Left: Contribution of backbone and side-chains to the total transfer free energy of the native state (top), denatured state (middle) and the m-value (bottom) as a function of molecular weight. Right: Contribution of charged, polar and apolar side-chains to the total side-chain transfer free energy of the native state (top), denatured state (middle) and the m-value (bottom) as a function of molecular weight. The order of labels in the keys is the same as the order of the curves in all panels below each key. (Colors: web only)

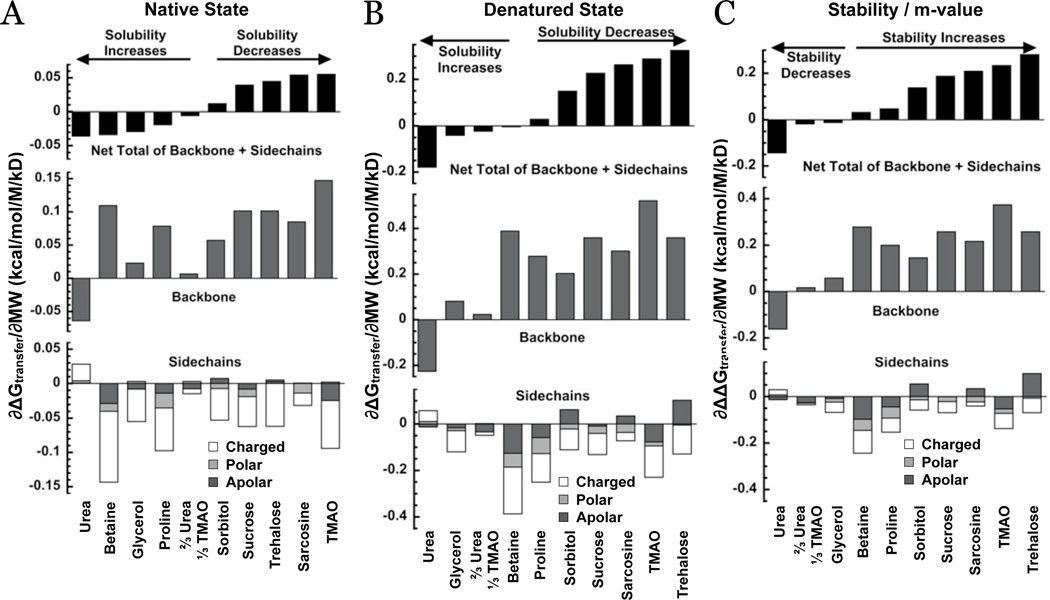

The parameters, ∂ΔGtr/∂MW, are plotted in Figure 6, for the native and denatured states and the m-value, respectively. In each of the panels, the net total ΔGtr is plotted in the top panel, backbone contributions in the middle panel and side-chain contributions on the bottom panel. The purpose of Figure 6 is to show trends. For clarity errors are not shown but they are significant and care should be taken in comparing proteins of the same molecular weight but with widely different amino acid compositions. The osmolytes are ranked in each figure according to the net total transfer free energy.

Figure 6.

The slope of ΔGtr with respect to protein molecular weight for the native state (panel A), denatured state (panel B) and m-value (panel C). The total transfer free energy contributions are given at the (top), the total backbone contribution (middle) and the total contribution of side-chains (bottom). The total side-chain contributions are further split into their charged, polar and apolar classes. Osmolytes are ranked according to the net total.

Upon inspection of Figures 5 and 6 and the Supplemental Figures S1–S9, several generalizations become immediately apparent that enable the classification of osmolytes.

Generalizations

The net transfer free energy of proteins is a delicate balance between backbone and side-chain contributions. Taken separately, these contributions can vary considerably in both sign and magnitude of the free energy among the various osmolytes.

The transfer free energy of the peptide backbone from water to protecting osmolytes is unfavorable and is favorable for transfer to urea.

Regardless of the net transfer free energy of N, D or the m-value for any given osmolyte, the collective contributions of the side-chains always oppose the contribution of the backbone. With some osmolytes, the collective side-chain ΔGtr contributions can be indifferent with a net zero contribution.

When segregated by class into charged, polar and apolar amino acid side-chain types, the charged ones make up the majority of the side-chain transfer free energy contribution that opposes the backbone. Net polar side-chain contributions are generally smaller, and for some osmolytes they are indifferent with a net zero contribution. Apolar side-chain contributions, when opposing the backbone, are also generally lower than the charged side-chain contributions, but collectively they can also be indifferent. For some osmolytes they have the same sign of the transfer free energy as the backbone.

Results in Figure 6 represent averages and individual proteins may vary from the average as evident in Figures S1–9. Accordingly, the rank order of osmolyte m-values may differ for proteins that have significantly different amino acid compositions.

Classifications

Osmolytes that stabilize proteins, raising the free energy of both the native and denatured states - The osmolytes that fall within this class (TMAO, sarcosine, sorbitol, sucrose and trehalose; see Figures S 5, 1, 2, 3, 4 resp.) have an unfavorable interaction with the peptide backbone that outcompetes the favorable interaction with the side-chains, which collectively oppose folding. For these osmolytes, the solubilities of N and D states will necessarily be reduced relative to water. The charged class of side-chains generally have favorable interactions with these osmolytes as do the polar class of side-chains. However, for TMAO and trehalose, polar side-chain free energy contributions are typically indifferent, with a net zero contribution. The transfer of apolar side-chains to 1M TMAO is favorable and to 1M Sucrose indifferent. In the case of sarcosine, sorbitol and trehalose, the apolar side-chain contributions are unfavorable to transfer.

Osmolytes that only moderately change protein stability - The osmolytes that fall within this class (glycine betaine, proline, and glycerol; see Figures S 7, 8 & 9 resp.) generally have nearly equivalent but opposing contributions of unfavorable backbone interactions and favorable side-chain interactions. For these osmolytes, the solubilities of N and D states will either increase due to slightly dominant favorable interactions with the side-chains or remain unchanged relative to water. All classes of amino acid side-chains interact favorably with these osmolytes with the exception of glycerol in which the polar and apolar side-chains are generally indifferent with a net zero free energy contribution (see also Figure 6).

Denaturing osmolytes - Urea denatures proteins predominantly through its favorable interaction with the peptide backbone (Figure 5). This favorable interaction outcompetes the collective unfavorable interactions with the side-chains that oppose denaturation. The contribution of charged residue side-chains account for the majority of the unfavorable interaction, with the polar side-chains remaining indifferent and the apolar side-chains favorable for both the native and denatured states of proteins. The solubilities of N and D both increase in urea solutions.

Counteracting osmolytes - In the 2:1 mixture of urea to TMAO, found in sharks and rays, TMAO more than offsets the opposing backbone contributions from urea (see Figure 3), but to a lesser degree the opposing side-chain contributions are also offset (Figure S6). The net effect of this mixed osmolyte system is such that the cumulative and favorable side-chain contributions slightly outweigh the unfavorable contribution of the backbone. As a result, the solubilities of N and D states in the mixture will be enhanced relative to water. The transfer of charged and apolar side-chains make up the collectively favorable side-chain interactions with the polar side-chains remaining indifferent.

3. Discussion

With reference to the biology of adaptation, the principles revealed from the application of the Transfer Model are compatible with and highlight the particular roles that osmolytes play in biology. While the mechanisms of adaptation to extreme environments can involve adjustments in the macromolecular components of the cell that give rise to alterations in both the quantitative and qualitative properties of the macromolecules themselves, a strategic and advantageous mechanism involves adjustments in the cellular solvent system within which macromolecules function [11]. The use of specific small molecules as biochemical protectants by organisms and cellular systems in essentially all taxa serves multiple roles, one of which is to preserve the structural integrity of macromolecules and macromolecular ensembles for function in environments that would normally be detrimental to the organisms’ survival [1]. Because the primary role of osmolytes is cell-volume regulation, attention to other needs imposed by the cellular microenvironment affords organisms and cellular systems the ability to more fully respond to changes in water stress. Be it extremes of temperature, desiccation, osmotic imbalance, or the presence of intracellular urea, osmolytes provide protection to macromolecules by enhancing stability and/or solubility over a significant range of water stress. The use of the Transfer Model for the study of a variety of osmolytes from each of the major classes, methylamines, polyols and sugars, and certain amino acids, reveals a delicate balance between opposing interactions of osmolytes with the backbone and the side-chains, and the relative magnitude of these contributions determines an osmolyte’s efficacy at stabilization and solubilization of proteins.

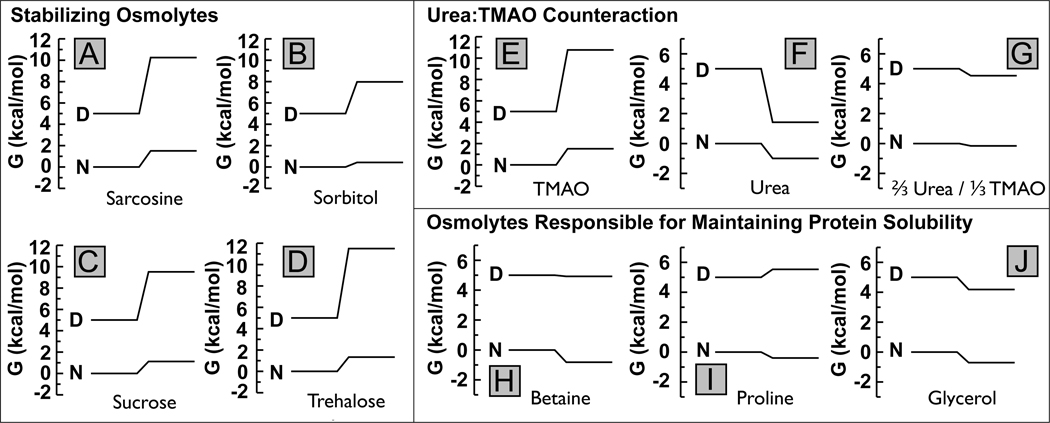

Several observations of osmolyte accumulation in nature make sense in light of the average protein behavior depicted in Figure 7. For example, proline accumulates in halophytes in response to salt stress [45], and it is beneficial for certain plants to increase the concentration of this osmolyte to counter a primarily osmotic challenge. In these cases the primary threats to the organisms are osmotic and the risk of precipitating proteins as a result of high intracellular proline concentration. Protein stability is not threatened so the modest ability of proline to stabilize proteins is not needed, but its ability to increase the solubility of native proteins is essential for its role (Figure 7-I). This solubilizing action of proline (and also glycine betaine) is well known from in vitro experiments [46–49], and even in cells [50].

Figure 7.

Free energy diagrams for each of the osmolytes indicated based on an average protein of molecular weight = 20kD calculated from Supplemental Figures S1–S9; diagrams of individual proteins may vary somewhat from the average. Initial stability in the absence of osmolyte is set at 5 kcal/mol. In each diagram, the left side represents 0M osmolyte, and the right side 1M. A decrease of the absolute value means an increase in solubility, and vice versa. An increase in the gap between native and denatured gibbs free energy translates to an increase in stability.

Intracellular accumulation of a strongly stabilizing osmolyte can threaten to precipitate protein, as deduced from the increasing gibbs free energy of the native state, and even more of the denatured state Figure 7-A–E. TMAO would tend to precipitate proteins in sharks, rays and other elasmobranch fish were it not for the accumulation of urea to prevent such cellular catastrophe. These animals have an intracellular concentration of urea that is two-fold greater than that of TMAO [3]. As a result, the combination of these osmolytes, on average, affects neither the stability nor the solubility of proteins much (see Figure 7-G and S6), and the mixture provides an effective osmotic balance against seawater. The classical 2:1 mixture of urea:TMAO found in sharks and rays has its counterpart in mammalian kidney with the mixtures of urea with glycerophosphocholine [51, 52]. While we do not have transfer free energy data available on this latter osmolyte, it is significant that in kidney a solubilizer (glycine betaine) accumulates in countering the osmotic stress (primarily due to salt) that occurs along side the high urea concentrations [51, 52].

Trehalose has been found to protect yeast against thermal stress by stabilizing proteins [53, 54]. This is reflected again in Figure 7-D by the big increase of the gap between the free energies of N and D states upon addition of trehalose. However, it is also obvious that this stabilization comes at a price: The solubility of N, and especially of D, strongly decreases in trehalose (increased free energies in Figure 7-D). An apparent paradox is posed by the observation that the presence of trehalose may actually decrease protein aggregation in yeast under conditions of heat stress [9], even though the solubilities of both native and denatured states are predicted to decrease (Figure 7-D). To resolve this paradox, it is important to realize that proteins tend to unfold and precipitate at elevated temperatures. Trehalose provides the driving force to shift the folding equilibrium back towards the native state, thus reducing the population of the more aggregation prone denatured state. Even though in the presence of trehalose ΔGtr,N predicts the native state to be less soluble than in its absence (Figure 7-D & S 4), it is still considerably more soluble than the denatured proteins that would accumulate without trehalose.

Our previous work [14, 19–21] has demonstrated that the transfer free energy of the backbone dominates over side chains in urea and in strongly stabilizing osmolytes, which in a natural setting are designed to counteract protein denaturing stresses. This governing role of the backbone results in the strong ability of protecting osmolytes and the non-protecting osmolyte, urea, to affect protein stability. However, as illustrated above, osmolytes do play roles in biology in which protein stability is not the primary issue, and, in these cases, the transfer free energy of the side chains play a key role. We cited proline and glycine betaine as examples of osmolytes that function primarily to increase the intracellular osmotic pressure, in order to balance the increased external osmotic pressure due to elevated salt concentrations. According to the solubilizing properties of proline and glycine betaine, we see an additional protecting role of keeping the intracellular proteins soluble is essential for protecting the organism. In these instances protein stability takes a back seat to the issue of keeping intracellular proteins soluble, and so does the backbone relative to the side-chains.

In summary, it is important to recognize that the manifestation of these principles would not have been possible without the predictive success of the Transfer Model as illustrated in Figure 2. More than 40 years ago, Tanford proposed the hypothesis that knowledge of the transfer free energies of protein backbone and side-chain groups from water to aqueous solutions of urea could quantitatively account for the thermodynamics of urea denaturation of proteins. The criteria for m-value prediction presented in the introduction are stringent, and the fact that the prediction holds over a 12 kcal/mol/M range, covering a variety of osmolytes and a large number of proteins demonstrates the validity of the approach by Cohn, Edsall and Tanford [16, 18].

4. Methods

4.1. Determination of experimental m-values

Many of the urea denaturation m-values were taken from the literature (see Supplemental Table 1). Far fewer m-values are available for the effect of other osmolytes on proteins. Thus we have measured additional m-values using various methods described below. Generally, the m-value of a stable protein with respect to a protecting osmolyte is measured at 25°C by evaluating the ability of the osmolyte to offset urea-induced denaturation [30, 32]. In other studies m-values for protecting osmolytes are determined by evaluating their stabilization against thermal denaturation (see below), and in still other cases proteins in buffer were destabilized by point mutations and m-values measured using protecting osmolytes to force the destabilized proteins to fold [13].

4.1.1. Forced folding of unstable Proteins

Nank4 − 7* (with at Tm of 34°C) was forced to fold at 50°C by titrating with sorbitol and glycine betaine, while monitoring the circular dichroism of the samples at 228 nm in a Jasco J-720 spectropolarimeter. The protein concentration was 0.18 mg/mL, and the details of preparing the samples with two osmolytes are described elsewhere [32, 33].

The CD signal was fit to the usual expression [55], and extended to global fits [33]. The stability equation in our case is [33]

| (2) |

where ΔG°(0, 0) is the protein’s stability in the absence of osmolyte, cs and cb are the concentrations of sorbitol and glycine betaine, and ms and mb are the m-values for sorbitol and glycine betaine.

4.1.2. Thermal Unfolding of Stable Proteins in the Presence of Osmolytes

Thermal melts were performed both with regular Jasco J-720 CD spectropolarimeter (as described previously [32]) and in a high-throughput Johnson & Johnson Thermofluor instrument [56, 57]. Samples were prepared in 384-well PCR plates, at 5µM concentration of the C77S mutant of E. coli Adenylate Kinase [58]. The buffer contained 10mM PIPES (pH 7.7), 0.1mM EDTA, and 0.15 M NaCl. Gradients of osmolyte concentrations were separately prepared on 96-well plates, transferred to the 384-well plates, and samples were mixed by mild sonication using a Misonix Sonicator (Cole Parmer) equipped with a microplate horn. Samples were overlaid with silicone oil to prevent evaporation during the thermal scans. The heating rate was 1K/min. Detection of the degree of unfolding was through fluorescence of ANS (50µM), added to the protein solution to monitor the appearance of denatured protein, and the thermal transitions were found to match the results from CD spectroscopic measurements [59].

The thermal unfolding data were fit to obtain the transition midpoint temperature Tm and the enthalpy of the transition ΔH° as described previously [33]. These parameters were used to calculate m-values using the relation [31]

| (3) |

where c is the concentration of the osmolyte used. The m-value at Tm could in principle be different from the one at room temperature. However, its temperature dependence is generally small [33]. This view is supported by the overall good agreement between prediction and measurement for the m-values that were determined through thermal unfolding.

4.2. Predicting the m-value

Transfer free energies were calculated using the procedure described previously in detail [20, 22]. We modified the approach for one protein. In E. Coli Adenylate Kinase, the lid domain has been found to be less stable than the rest of the protein [59]. We performed thermal scans with this protein, and accordingly, we assume in the m-value calculation that this domain (residues 110–164) is unfolded at the midpoint temperature of denaturation.

We have developed a website for general use in calculating m-values for proteins. The m-value calculator is located at http://sbl.utmb.edu/mvalue.html, and requires uploading the atomic coordinate file of a protein of interest, which may be obtained from the Protein Databank. The computation is instantaneous, and the output is a tab-delimited plain text file with m-values for each of the nine osmolytes along with protein solvent accessible surface areas, transfer free energies of native and denatured states, and residue-specific group contributions to both the transfer free energy and to the surface areas.

4.3. Classification of the general properties of osmolyte effects on protein native and denatured states and protein m-values

A database of proteins was generated from the Protein Data Bank (http://www.rcsb.org/) using the ”Advanced Search” feature and the following criteria. 1) Number of Chains in the Asymetric Unit = 1. 2) Number of Chains in the Biological Assembly = 1. 3) Molecular Weight Structure = (0–50) kiloDaltons. 4) Experimental Method = X-Ray. 5) X-Ray Resolution = Between 1 and 2 Ångstrøms. 6) Macromolecule Type - Contains Protein = Yes, Contains DNA = No, Contains RNA = No, Contains RNA/DNA Hybrid = No. 7) Number of Entities - Entity Type = Protein, Between 1 and 1. 8) Has Modified Residues = No. 9) Remove Similar Sequences at 95% Identity which effectively removes multiple structures of the same protein (e.g. multiple mutations) leaving a single representative structure for each protein.

The results of these search criteria produced 2904 structures. Our transfer free energy calculator further condensed this structure set to 1798 structures by eliminating structures with missing residues, structures containing only backbone traces (i.e. no side-chains) and PDB structure files with sequentially listed residues having the same residue number.

The output of our transfer free energy calculator produced the molecular weight and the cumulative side-chain, backbone and total transfer free energies for the native (crystal structure) and denatured states and the m-value of the proteins. In addition, it segregated sidechain transfer free energies into charged (Asp, Glu, His, Lys, and Arg), polar (Ser, Thr, Pro, Gln, Asn), and nonpolar (Ala, Phe, Leu, Ile, Val, Met, Trp, Tyr) classes. These specific group contributions were plotted as a function of the molecular weight of the protein, and this dependence was fit to a linear regression to generalize the average transfer free energies of proteins. These plots for all osmolytes (TMAO, sarcosine, glycine betaine, proline, glycerol, sorbitol, sucrose, trehalose, urea and a mixture of 2/3M Urea with 1/3M TMAO) are provided in the Supplement.

For the purpose of computing m-values we strongly recommend use of the online calculator at http://sbl.utmb.edu/mvalue.html, rather than the average energetics obtained through the general classification. It is clear from the scatter of the data in the supplementary figures that the general classification provides good general trends but may lead to skewed results for specific proteins. In fact, the rank order of osmolyte m-values may differ for proteins of significantly different amino acid compositions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We dedicate this paper to the memory of Prof. Stanley J. Gill, one of the original founders of the Gibbs Conference. His contributions and belief in the Conference were instrumental in launching and sustaining the meeting in its early years. The authors gratefully acknowledge support by NIH through grant GM049760 to JR, and by DoD through DURIP grant W911NF-06-1-0131 to UTMB.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Note added in proof

Prof. R.L. Baldwin has noted that Gibbs expounded the principle in 1871, long before Lewis and Randall. ("The Collected Works of J. Willard Gibbs,Volume I. Thermodynamics" Chapter III, On the equilibrium of heterogeneous substances, pages 55 – 349. Yale Univ. Press, 1948. New Haven.)

References

- 1.Hochachka P, Somero G. Mechanism and Process in Physiological Evolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2002. Biochemical Adaptation. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yancey PH, Somero G. Counteraction of urea destabilization of protein structure by methylamine osmoregulatory compounds of elasmobranch fishes. Biochem. J. 1979;183(2):317–323. doi: 10.1042/bj1830317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yancey P, Clark M, Hand S, Bowlus R, Somero G. Living with water stress: Evolution of osmolyte systems. Science. 1982;217(4566):1214–1222. doi: 10.1126/science.7112124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Somero G. Protons, osmolytes, and fitness of internal milieu for protein function. Am. J. Physiol. 1986;251(2 Pt 2):R197–R213. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1986.251.2.R197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gillett MB, Suko JR, Santoso FO, Yancey PH. Elevated levels of trimethylamine oxide in muscles of deep-sea gadiform teleosts: A high-pressure adaptation? J. Exp. Zool. 1997;279:386–391. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin TY, Timasheff SN. Why do some organisms use a urea-methylamine mixture as osmolyte - thermodynamic compensation of urea and trimethylamine n-oxide interactions with protein. Biochemistry. 1994;33(42):12695–12701. doi: 10.1021/bi00208a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang A, Bolen D. A naturally occurring protective system in urea-rich cells: Mechanism of osmolyte protection of proteins against urea denaturation. Biochemistry. 1997;36(30):9101–9108. doi: 10.1021/bi970247h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singer M, Lindquist S. Multiple effects of trehalose on protein folding in vitro and in vivo. Mol Cell. 1998;1(5):639–648. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singer M, Lindquist S. Thermotolerance in saccharomyces cerevisiae: The yin and yang of trehalose. Trends Biotechnol. 1998;16(11):460–468. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(98)01251-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yancey PH. Organic osmolytes as compatible, metabolic and counteracting cytoprotectants in high osmolarity and other stresses. J. Exp. Biol. 2005;208(Pt 15):2819–2830. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Somero GN. Protein adaptations to temperature and pressure: Complementary roles of adaptive changes in amino acid sequence and internal milieu. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. 2003;136:577–591. doi: 10.1016/s1096-4959(03)00215-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qu Y, Bolen C, Bolen D. Osmolyte-driven contraction of a random coil protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998;95(16):9268–9273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baskakov I, Bolen DW. Forcing thermodynamically unfolded proteins to fold. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273(9):4831–4834. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.9.4831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bolen D, Baskakov I. The osmophobic effect: Natural selection of a thermodynamic force in protein folding. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;310(5):955–963. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garcia-Perez A, Burg MB. Renal medullary organic osmolytes. Physiol Rev. 1991;71(4):1081–1115. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1991.71.4.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohn E, Edsall J. Proteins, Amino Acids, and Peptides as Ions and Dipolar Ions. New York: Reinhold Publishing Corp.; 1943. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lewis G, Randall M. Thermodynamics and the free energy of chemical substances. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1923. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nozaki Y, Tanford C. The solubility of amino acids and related compounds in aqueous urea solutions. J. Biol. Chem. 1963;238(12):4074–4081. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Y, Bolen D. The peptide backbone plays a dominant role in protein stabilization by naturally occurring osmolytes. Biochemistry. 1995;34(39):12884–12891. doi: 10.1021/bi00039a051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Auton M, Bolen D. Additive transfer free energies of the peptide backbone unit that are independent of the model compound and the choice of concentration scale. Biochemistry. 2004;43(5):1329–1342. doi: 10.1021/bi035908r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Auton M, Bolen DW. Predicting the energetics of osmolyte-induced protein folding/unfolding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102(42):15065–15068. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507053102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Auton M, Bolen DW. Application of the transfer model to understand how naturally occurring osmolytes affect protein stability. Methods Enzymol. 2007;428:397–418. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)28023-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Auton M, Holthauzen L, Bolen D. Anatomy of energetic changes accompanying urea-induced protein denaturation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104(39):15317–15322. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706251104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schellman J. Protein stability in mixed solvents: A balance of contact interaction and excluded volume. Biophys. J. 2003;85(1):108–125. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74459-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldenberg D. Computational simulation of the statistical properties of unfolded proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;326(5):1615–1633. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gong H, Rose G. Assessing the solvent-dependent surface area of unfolded proteins using an ensemble model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105(9):3321–3326. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712240105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Creamer T, Srinivasan R, Rose GD. Modeling unfolded states of proteins and peptides. ii. backbone solvent accessibility. Biochemistry. 1997;36(10):2832–2835. doi: 10.1021/bi962819o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tanford C. Isothermal unfolding of globular proteins in aqueous urea solutions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1964;86(10):2050–2059. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greene RJ, Pace C. Urea and guanidine hydrochloride denaturation of ribonuclease, lysozyme, alpha-chymotrypsin, and beta-lactoglobulin. J. Biol. Chem. 1974;249(17):5388–5393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mello C, Barrick D. Measuring the stability of partly folded proteins using tmao. Protein Sci. 2003;12(7):1522–1529. doi: 10.1110/ps.0372903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferreon AC, Ferreon JC, Bolen DW, Röosgen J. Protein phase diagrams ii: Non-ideal behavior of biochemical reactions in the presence of osmolytes. Biophys. J. 2007;92(1):245–256. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.092262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holthauzen LM, Bolen DW. Mixed osmolytes: The degree to which one osmolyte affects the protein stabilizing ability of another. Protein Sci. 2007;16(2):293–298. doi: 10.1110/ps.062610407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holthauzen L, Auton M, Sinev M, Röosgen J. Protein stability in the presence of cosolutes. Methods Enzymol. 2011;492C:61–125. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-381268-1.00015-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bolen D. Effects of naturally occurring osmolytes on protein stability and solubility: Issues important in protein crystallization. Methods. 2004;34(3):312–322. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2004.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Auton M, Bolen D, Röosgen J. Structural thermodynamics of protein preferential solvation: Osmolyte solvation of proteins, aminoacids, and peptides. Proteins. 2008;73(4):802–813. doi: 10.1002/prot.22103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Felitsky D, Cannon JG, Capp M, Hong J, Van Wynsberghe AW, Anderson C, Record MJ. The exclusion of glycine betaine from anionic biopolymer surface: Why glycine betaine is an effective osmoprotectant but also a compatible solute. Biochemistry. 2004;43(46):14732–14743. doi: 10.1021/bi049115w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin B, Pettitt B. Note: On the universality of proximal radial distribution functions of proteins. J. Chem. Phys. 2011;134(10):106101. doi: 10.1063/1.3565035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scholtz J, Barrick D, York E, Stewart J, Baldwin R. Urea unfolding of peptide helices as a model for interpreting protein unfolding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1995;92(1):185–189. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.1.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cannon JG, Anderson C, Record MJ. Urea-amide preferential interactions in water: Quantitative comparison of model compound data with biopolymer results using water accessible surface areas. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111(32):9675–9685. doi: 10.1021/jp072037c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holthauzen L, Röosgen J, Bolen D. Hydrogen bonding progressively strengthens upon transfer of the protein urea-denatured state to water and protecting osmolytes. Biochemistry. 2010;49(6):1310–1318. doi: 10.1021/bi9015499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pace CN, Huyghues-Despointes BM, Fu H, Takano K, Scholtz J, Grimsley G. Urea denatured state ensembles contain extensive secondary structure that is increased in hydrophobic proteins. Protein Sci. 2010;19(5):929–943. doi: 10.1002/pro.370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hopkins FG. Denaturation of proteins by urea and related substances. Nature. 1930;3175(126):328–330. 383–384. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith H. The retention and physiological role of urea in the elasmobranchii. Biol Rev Camb Philos. 1936;11(1):49–82. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robinson D, Jencks W. Effect of denaturing agents of the urea-guanidinium class on the solubility of acetyltetraglycine ethyl ester and related compounds. J. Biol. Chem. 1963;238:1558–1560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stewart G, Lee J. Role of proline accumulation in halophytes. Planta. 1974;120(3):279–289. doi: 10.1007/BF00390296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schobert B, Tschesche H. Unusual solution properties of proline and its interaction with proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1978;541(2):270–277. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(78)90400-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Paleg L, Stewart G, Bradbeer J. Proline and glycine betaine inuence protein solvation. Plant Physiol. 1984;75(4):974–978. doi: 10.1104/pp.75.4.974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kumar T, Samuel D, Jayaraman G, Srimathi T, Yu C. The role of proline in the prevention of aggregation during protein folding in vitro. Biochem Mol Biol Int. 1998;46(3):509–517. doi: 10.1080/15216549800204032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Samuel D, Kumar T, Ganesh G, Jayaraman G, Yang P, Chang M, Trivedi V, Wang S, Hwang K, Chang D, Yu C. Proline inhibits aggregation during protein refolding. Protein Sci. 2000;9(2):344–352. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.2.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ignatova Z, Gierasch L. Monitoring protein stability and aggregation in vivo by real-time fluorescent labeling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101(2):523–528. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0304533101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yancey PH, Burg MB. Distribution of major organic osmolytes in rabbit kidneys in diuresis and antidiuresis. Am. J. Physiol. 1989;257(4 Pt 2):F602–F607. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1989.257.4.F602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Peterson DP, Murphy KM, Ursino R, Streeter K, Yancey PH. Effects of dietary protein and salt on rat renal osmolytes: Covariation in urea and gpc contents. Am. J. Physiol. 1992;263(4 Pt 2):F594–F600. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1992.263.4.F594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wiemken A. Trehalose in yeast, stress protectant rather than reserve carbohydrate. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 1990;58(3):209–217. doi: 10.1007/BF00548935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hottiger T, De Virgilio C, Hall M, Boller T, Wiemken A. The role of trehalose synthesis for the acquisition of thermotolerance in yeast. ii. physiological concentrations of trehalose increase the thermal stability of proteins in vitro. Eur. J. Biochem. 1994;219(1–2):187–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb19929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Santoro M, Bolen DW. Unfolding free energy changes determined by the linear extrapolation method. 1. unfolding of phenylmethanesulfonyl alpha-chymotrypsin using diffierent denaturants. Biochemistry. 1988;27(21):8063–8068. doi: 10.1021/bi00421a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Todd MJ, Salemme FR. Direct binding assays for pharma screening - assay tutorial: Thermouor miniaturized direct-binding assay for hts & secondary screening. Genetic Engineering News. 2003;23(3):28–29. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Matulis D, Kranz J, Salemme F, Todd M. Thermodynamic stability of carbonic anhydrase: Measurements of binding affinity and stoichiometry using thermouor. Biochemistry. 2005;44(13):5258–5266. doi: 10.1021/bi048135v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sinev MA, Sineva EV, Ittah V, Haas E. Domain closure in adenylate kinase. Biochemistry. 1996;35(20):6425–6437. doi: 10.1021/bi952687j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schrank T, Bolen D, Hilser V. Rational modulation of conformational uctuations in adenylate kinase reveals a local unfolding mechanism for allostery and functional adaptation in proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106(40):16984–16989. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906510106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.