Abstract

Objectives To use changes in heart disease mortality rates with age to investigate the plausibility of attributing women’s lower heart disease mortality than men to the protective effects of premenopausal sex hormones.

Design Modelling study of longitudinal mortality data with models assuming (i) a linear association between mortality rates and age (absolute mortality) or (ii) a logarithmic association (proportional mortality). We fitted models to age and sex specific mortality rates in the census years 1950 to 2000 for three birth cohorts (1916-25, 1926-35, and 1936-45).

Data sources UK Office for National Statistics and the US National Center for Health Statistics.

Main outcome measure(s) Fit of models to data for England and Wales and for the US.

Results For England-Wales data, proportional increases in ischaemic heart disease mortality fitted the data better than absolute increases (improvement in deviance statistics: women, 58 logarithmic units; men, 37). We identified a deceleration in male mortality after age 45 years (decreasing from 30.3% to 5.2% per age-year, P=0.042), although the corresponding difference in women was non-significant (P=0.43, overall trend 7.9% per age-year, P<0.001). By contrast, female breast cancer mortality decelerated significantly after age 45 years (decreasing from 19.3% to 2.6% per age-year, P<0.001). We found similar results in US data.

Conclusions Proportional age related changes in ischaemic heart disease mortality, suggesting a loss of reparative reserve, fit longitudinal mortality data from England, Wales, and the United States better than absolute age related changes in mortality. Acceleration in male heart disease mortality at younger ages could explain sex differences rather than any menopausal changes in women.

Introduction

The relative delay in the onset of ischaemic heart disease in women compared with men, on a population level, has been attributed largely to the putative protective effects of the premenopausal hormonal milieu, but little epidemiological or clinical evidence supports this.1 Circulating lipids have been shown to change levels during the menopausal transition,2 but interpretation of these changes is made complex by discrepant changes in the levels of cholesterol and apolipoprotein.3 Ischaemic heart disease mortality increases with age, but cross sectional analyses of age specific mortality have not shown any sudden proportional acceleration at the age of menopause in women, either in data from England and Wales,4 the United States,5 or Japan.6 By contrast, the proportional increase in breast cancer mortality with age abruptly decelerates at menopausal age among women.1 7

Two issues need resolution with respect to previous cross-sectional analyses. Firstly, it is not known why age related mortality should be examined on the proportional (or logarithmic) scale for ischaemic heart disease mortality, rather than an absolute age related increase in mortality, which accelerates throughout adult life in both men and women. By contrast, the accumulation of multiple injuries has been suggested as a mechanistic explanation for a proportional increase in cancer related mortality with age.7 Secondly, ischaemic heart disease has a long latency period before death, and in view of changing lifestyles and treatment environments over a person’s lifetime, it is difficult to interpret cross sectional associations between age and mortality.

The dual goal of this analysis was to challenge existing paradigms regarding causality attribution to menopause as it relates to the risk of ischaemic heart disease in women, by providing a mechanistic hypothesis for proportional increases in mortality, and applying it to longitudinal vital statistics data. To do this, we aimed to show that a proportional change in mortality is biologically and numerically meaningful, possibly representing a constant probability of the failure of tissue reparative cells across a lifetime.8 9 Indeed, the length of telomeres in circulating leucocytes, which can be taken as a proxy for other bone marrow cells that replenish the circulatory system, reduces linearly during adult life.10 Because telomere length shortens linearly with every cell division, the linear loss of telomere length over adult life10 indicates that, on average, cells divide at a constant rate over time. Loss of telomere length limits a cell’s capacity to replicate.11 Therefore, regeneration of bone marrow cells is limited in a linear fashion with increasing age. This explanation is a generalisation of the cancer specific process proposed by Pike and colleagues7 to all senescent chronic disease, and is based on age related heart disease mortality among birth cohorts (born 1916-45) in England and Wales12 and the United States.13

Methods

Mortality models as a function of age

Model 1 assumes a linear association between mortality rates and age (absolute mortality). Indeed, this model is implicit in the statement of the current hypothesis that the increase in absolute heart disease mortality accelerates at menopause. Such a model would suggest that the upward slope of absolute mortality versus age is roughly constant before menopause, and would change to a different slope around the time of menopause in women.

Mortality rate=β0+β1×age in years+β2×(time since menopause in years)

(where β0=intercept, β1=linear slope with respect to age, and β2=change in slope after menopause; if there is no change in slope at menopause, β2 estimate=0)

Model 2 assumes a proportional (or logarithmic) association between mortality and age. Survival of an organism results from an ongoing repair of tissue injury that is dependent on a pool of repair mechanisms (for example, regenerative repair cells). Ageing is thought to be a result of loss of this pool. If the probability of removal of these reparative cells due to cell division is constant over time, the reparative reserve is lost at a constant proportion with age. Using the derivation in web appendix 1, we obtained the following model:

log(mortality rate)=β0+β1×age in years+β2×(time since menopause in years)

(where β0=intercept, β1=linear slope with respect to age, and β2=change in slope after menopause; if there is no change in slope at menopause, β2 estimate=0)

Therefore, we can interpret modelling changes in proportional mortality in model 2, rather than absolute mortality as in model 1, as changes in reparative demands on a decreasing reserve of repair mechanisms (for example, stem cells).

We used the deviance metric (loge(likelihood2reference/likelihood2model)), with the naive model as the reference, to determine which model made the better fit to the data. For likelihood calculations to be comparable, we also specified the residuals from the models in the same manner—that is, on the absolute mortality rate scale.

Modelling of data from England, Wales, and the United States

We analysed data abstracted from the United Kingdom Office for National Statistics 20th century mortality data for England and Wales,12 US census and vital statistics databases, and the US National Center for Health Statistics.13 We used the age and sex specific mortality rates for the actual census years 1950 to 2000. We used the methods proposed by Frost14 to follow the mortality of three decade-long birth cohorts (1916-25, 1926-35, and 1936-45). We chose these birth cohorts because they included women who reached postmenopausal ages within the 20th century, and these cohorts were relatively unaffected by large scale immigration waves into the United States. We chose the same birth cohorts for the England-Wales data for comparability.

We followed US cohorts in time thus: the census counts and mortality rates for the 1936-45 cohort corresponded with the 5-14 year age group (cohort mid-age rounded to 10 years) in the 1950 census and vital statistics reports, and the 15-24 year age group (cohort mid-age 20 years) in the 1960 reports. We continued this method up to the 75-84 year age group (cohort mid-age 80 years) in the 2000 reports. Similarly, we traced the mortality rates for all three cohorts. We analysed all cause mortality and disease specific mortality rates for heart disease (in men and women) and breast cancer (only in women).

We abstracted mortality data for ischaemic heart disease and breast cancer for the England-Wales cohorts, using International Classification of Diseases codes (table 1). For the US data source,13 longitudinal mortality rates over the full analysis period were available for total heart disease rather than for ischaemic heart disease. The National Center for Health Statistics collected breast cancer mortality data only for women older than 25 years.13 We excluded death rates for individuals older than 85 years because the National Center for Health Statistics placed these deaths into a single group in these datasets. Therefore, we could not assign these individuals to any particular decadal birth cohort. Web appendix 2 shows the full abstracted dataset from the vital statistics sources used to graph and model the data.

Table 1.

International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes for ischaemic and total heart disease and female breast cancer

| Ischaemic heart disease (UK) | Total heart disease (United States) | Breast cancer (UK and United States) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICD-6 | 420.0 to 420.2 | 410 to 443 | 170 |

| ICD-7 | 420.0 to 420.2 | 400 to 402, 410 to 443 | 170 |

| ICD-8 | 410 to 414 | 390 to 398, 402, 404, 410 to 429 | 174 |

| ICD-9 | 410 to 414 | 390 to 398, 402, 404, 410 to 429 | 174 to 174.9 |

| ICD-10 | I20 to I25 | I00 to I09, I11, I13, I20 to I51 | C50 |

We analysed data separately for men and women. We used the cohort mid-age as the age variable for plotting and regression analysis. We regarded rates for women in cohorts when they aged to 45-54 years (cohort mid-age 50 years) and older to be postmenopausal. The vast majority of menopause occurs during the 45-54 year age period. We also compared the different age-mortality slopes before and after 45 years of age in models 1 and 2, to determine whether the age-mortality trend would change at menopause in women, and at a similar age in men.

We calculated the longitudinal death rates in the cohorts using generalised mixed models. For comparability of model fit between the linear age dependence and the log-linear age dependence, we calculated the explained variance in the mortality rate data on the original scale (Gaussian residual errors). Detailed model equations are presented in web appendix 1. If we saw a secular trend by calendar year, we would model such a trend as secondary analysis.

To compare the models, we tabulated deviance statistics and the difference in the Akaike information criterion15 with the naive linear model as the reference. We considered a reduction of at least four logarithmic units in the Akaike information criterion to be a significant improvement, and a reduction of at least 10 logarithmic units to be a highly significant improvement in model fit (simplified from Burnham and Anderson’s multiple level criteria16).

Model fitting was undertaken using the generalised linear latent and mixed models software implemented in Stata (version 10, StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Web appendix 1 also describes the sensitivity analysis.

Results

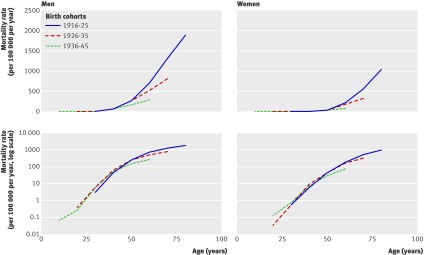

Table 2 shows the census counts of men and women of the three birth cohorts (1916-25, 1926-35, and 1936-45) for 1950 and 2000, by country. Figure 1 shows the ischaemic heart disease mortality of the three birth cohorts in England and Wales as they aged in the 20th century, either on the absolute scale or the logarithmic scale.

Table 2.

Populations of birth cohorts (in thousands) in census years 1950 and 2000

| Birth cohort | Census year | England and Wales | United States | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | Women | Men | |||

| 1916-25 | 1950 | 1681 | 1673 | 12 162 | 11 597 | |

| 2000 | 1050 | 741 | 7482 | 4879 | ||

| 1925-35 | 1950 | 1390 | 1346 | 11 181 | 10 918 | |

| 2000 | 1198 | 1100 | 10 088 | 8303 | ||

| 1935-45 | 1950 | 1501 | 1569 | 11 944 | 12 375 | |

| 2000 | 1455 | 1429 | 12 629 | 11 645 | ||

Fig 1 Ischaemic heart disease mortality in England and Wales by age plotted on absolute scale (top panels) and on logarithmic scale (bottom panels)

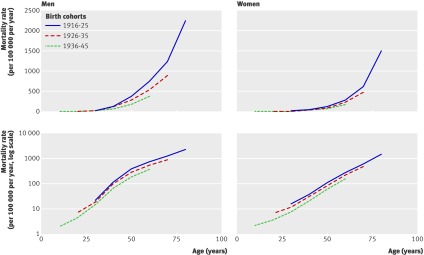

For the England-Wales birth cohorts, all absolute mortality curves showed an upward-bent profile, whereas the log-mortality curves did not show a prominent upward bend. Among women, none of the cohorts showed a substantial upward shift in slope in the log-mortality curves due to ischaemic heart disease around the time of menopause (45-55 years), and there was a log-linear increase in mortality throughout all ages. Among men, the log-linear increase in mortality was strongly blunted after age 45 years in all birth cohorts. For both men and women, we saw a reduction in the overall mortality of successive birth cohorts at advanced ages. US data for total heart disease mortality also showed the same pattern (fig 2).

Fig 2 Total heart disease mortality in the United States by age plotted on absolute scale (top panels) and on logarithmic scale (bottom panels)

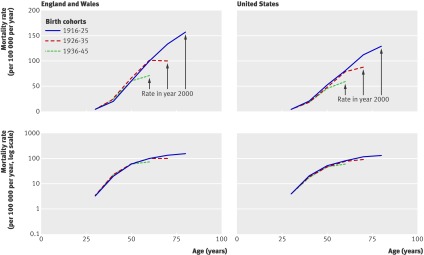

Figure 3 shows female breast cancer mortality on the absolute and logarithmic scales in the England-Wales and the US birth cohorts. As with previous cross sectional analyses,1 we observed a distinct difference in slope gradients before and after age 45 years in the log-mortality rate plots. We did not see any cohort-wide reductions in breast cancer mortality for later cohorts, especially at young ages. However, there is a suggestion that the log-mortality curves could have flattened in the 1990s for all cohorts (that is, at different ages for each of the cohorts). This finding could be a secular phenomenon related to the adoption of breast cancer screening programmes in the early 1990s.17 18 19

Fig 3 Female breast cancer mortality in England and Wales and the United States plotted on absolute scale (top panels) and on logarithmic scale (bottom panels)

Table 3 shows the association of mortality with age by longitudinal data analysis for the various models and their goodness of fit. For all cause mortality and heart disease mortality, the log-mortality models fit the data much better than the absolute mortality models. Interestingly, women showed a non-significant deceleration in the log-mortality curves after age 45 years, whereas men showed a significant deceleration after age 45 years. For breast cancer mortality in women, the log-mortality model showed the best fit, with a significant deceleration of age related increase in mortality after age 45 years. We also identified a strong secular trend for reduced breast cancer mortality after 1990 (fig 3). After adjusting for birth cohort and age, breast cancer mortality was 25% lower after 1990. Web appendix 3 shows similar results of the analyses of total heart disease and breast cancer mortality in US data.

Table 3.

Ischaemic heart disease mortality and female breast cancer mortality in England-Wales birth cohorts, by sex

| Model | Ischaemic heart disease | Breast cancer (women only) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | |||||||

| β, P* | Deviance, difference in AIC† | β, P* | Deviance, difference in AIC† | β, P* | Deviance, difference in AIC† | |||

| Linear (overall slope) | 22.4, P<0.001 | Reference | 10.3, P<0.001 | Reference | 2.5, P<0.001 | Reference | ||

| Log-linear (overall slope) | 5.8%, P<0.001 | −37 −37 |

7.9%, P<0.001 | −58 −58 |

4.2%, P<0.001 | −5 −5 |

||

| Linear with spline‡ | ||||||||

| Slope before age 45 years | −2.1, P=0.61 | −16 −14 |

−4.2, P=0.14 | −19 −17 |

1.4, P<0.001 | −5 −3 |

||

| Difference in slope after age 45 years | 48.9, P<0.001 | 29.0, P<0.001 | 2.1, P<0.001 | |||||

| Log-linear with spline‡ | ||||||||

| Slope before age 45 years | 30.3%, P=0.014 | −50 −48 |

39.3%, P=0.32 | −62 −60 |

19.3%, P<0.001 | −31 −29 |

||

| Difference in slope after age 45 years | −25.1%, P=0.042 | −31.6%, P=0.43 | −16.7%, P<0.001 | |||||

AIC=Akaike information criterion.

*β= slope or change in slope after age 45 years compared with the slope before age 45 years. P=probability for Wald test of significance of the null hypothesis that β equals 0. Linear slopes represent increase in deaths per 100 000 per age-year. Log-linear slopes represent percentage increase in mortality per age-year.

†A lower or more negative deviance indicates better model fit. The difference in AIC penalises the deviance metric for the addition of extra parameters in the interest of model parsimony.

‡Spline models included the variable “age-spline” was equal to 0 if cohort mid-age was under 50 years (that is, younger than the 45-54 year cohort), and equal to the cohort mid-age for older ages.

Discussion

We have shown that analysis using log-linear mortality rates is consistent with the plausible biological mechanism of reparative reserve. By using the most comprehensive and complete longitudinal mortality dataset available for England and Wales as well as for the United States, in the 20th century, we have shown that log-linear models fit the mortality data much better than a simple linear model.

Comparison with previous findings from cross sectional analyses

Our longitudinal cohort analysis confirms previously reported cross sectional age-mortality associations.4 5 However, our findings are more convincing than those of previous analyses, because age trends are best studied by following cohorts of individuals over their lifetime rather than comparing different individuals of the same and different ages in a cross section of the population.

Issues of unaccounted secular trends and cohort effects have clouded the interpretation of cross sectional mortality analyses, and are resolved by our longitudinal analysis. Cross sectional analyses would not have detected our finding that cohorts born later in the 20th century have lower cardiovascular mortality at higher ages than cohorts born earlier in the 20th century. In addition, our analysis showed a secular change in breast cancer mortality after the 1990s, which could not have been detected with cross sectional analysis.

We showed that there was no sharp increase in slope or step increase in ischaemic heart disease mortality among women at menopausal ages. The mortality steadily increased across all ages in adult women, whereas the corresponding increase was blunted at older ages in men. These observations also applied to three birth cohorts in different countries, presumably with varying secular life experiences in terms of lifestyle, knowledge of health risks (such as smoking), and disease and risk factor treatments. These data strengthen the conclusions of previous cross sectional analyses.5 In our longitudinal birth cohort analyses, the age effect is not confounded by the decreasing overall heart disease risk of successive birth cohorts. Therefore, the flattening of the curves at higher ages in men should be justifiably considered a biological phenomenon rather than an artefact of cross sectional analysis.

Potential explanations for age-mortality trends

The steady log-linear increase in age related heart disease mortality in men and women suggests cumulative effects of lifelong vascular injury and failure of repair mechanisms. However, this interpretation is based on mathematical derivation and published biological studies in small samples, and not measurements in these national cohorts.

Because both men and women in our study showed upward bent curves on the absolute mortality scale, the upward bend cannot be interpreted as being attributable to menopause. In fact, men showed a steeper age-mortality slope than women as young adults, which flattened into middle age. As previously suggested,1 the accelerated risk in men at younger ages compared with women at the same ages could indicate an accelerated failure of the reparative reserve in young men, rather than the relative protection of premenopause hormonal effects in young women. Because we analysed only vital statistics data (and therefore could not analyse individual cardiovascular risk factors or the individual timings of menopause in women), this biological explanation is speculative. However, our proposed mechanism is consistent with a study reporting that the rate of telomere loss per age-year was equal in adult men (0.038 kb/age-year) and women (0.036 kb/age-year) at all ages between 25 and 75 years.20 But in that study,20 age adjusted telomere lengths were substantially shorter, by 0.28 kb, in men than women. This difference is equivalent to the telomere shortening process being shifted 7.6 age-years in men, compared with women.

Although we did not see any proportional acceleration of heart disease mortality at menopause, the absolute mortality still increases at all ages in women, including the postmenopausal period. Thus the current concern about cardiovascular disease among women in the ageing US population is fully justified, but with the focus on lifetime risk rather than primarily at menopause.

Pike and colleagues discussed that carcinogenesis, being a multistage process, would be expected to have a log-linear age-mortality association, and they showed such an association for colorectal cancer mortality.7 From new cell biological insights,8 9 10 we generalised this paradigm to all chronic senescent processes, including the multistage accumulation of carcinogenic trauma, as well as vascular damage under the general concept of the failure of reparative reserve. Our models confirm the deceleration of breast cancer mortality around the age of menopause as previously shown.5 7 This finding is consistent with our biological model that non-communicable diseases could represent a failure of the reparative reserve. The cyclical hyperplasia and hypoplasia of breast tissue (evidence reviewed by Pike et al7) before menopause is expected to strain the reparative reserve for this organ more than after menopause. The demands on the reparative reserve could vary with age for different organ systems, and for the two sexes, modulating the rate of reduction in reparative reserve over age. Similarly, known cardiovascular risk factors such as smoking, hypercholesterolaemia, and hypertension might damage vascular tissue and therefore increase the demand for repair. This would consequently alter the rate of loss of reparative reserve. We recognise that a full explanation of the age association of cause specific mortality due to chronic senescent conditions would require modelling these factors. However, the log-linear mortality-age model had a much better fit than the simple linear model.

Census and mortality data

A major strength of this analysis is the comprehensive nature of the British and US census and mortality data. However, there are specific caveats. Although we examined ischaemic heart disease mortality in the British data, cause specific mortality data were not separately available for the disease in the US data source for periods before 1980.13 However, the findings were substantially similar in the two analyses. Ischaemic heart disease constituted most of the age adjusted total heart disease mortality in the United States for years when the data were separately available—for example, of total heart mortality in 2000, 75.4% in men and 69.5% in women were due to ischaemic heart disease. Thus the US and British data were similarly interpretable. Total heart disease mortality also includes deaths due to heart failure, which is a chronic senescent condition associated with the loss of progenitor cells,21 22 and our biological discussion applies to heart failure as well.

Another consideration is that the birth cohorts were open cohorts due to immigration and emigration. However, individuals who migrated to the United States as adults in the 1900-20 wave of immigration would not greatly affect the earliest birth cohort (1916-25) of this analysis. The recent major immigration wave of 1980-2000 included mostly young adults and added little to the population aged 45 years and older,23 and should not affect our latest birth cohort. In addition, the US and Britain have different migration experiences, yet we found similar results between the two datasets, suggesting that immigration patterns are unlikely to affect the conclusions and interpretation of our analysis.

Conclusions

We have shown that each successive birth cohort in England, Wales, and the United States in 1916-45 had lower total and heart disease mortality over their lifetimes. Heart disease mortality in women increased exponentially throughout all ages, with no special step increase at menopausal ages. This finding sharply contrasts with breast cancer mortality in women, which decelerated drastically at menopause. The increase in heart disease mortality due to age in men was greater during early adulthood than that in women, and the age related increase was blunted at advanced ages.

Efforts to improve cardiac health in women should focus on lifetime risk rather than risk only after menopause. Our proposed biological model showing that fatal events are a result of a loss of reparative reserve fitted the mortality data far better than a model of linear age related increases in absolute mortality rates. This finding should serve as a point of departure for more refined models of age related mortality.

What is already known on this topic

Although heart disease mortality increases with age, it is lower in women than in men

It has been suggested that this protective effect is due to female sex hormones, and the protection is therefore lost at menopause

What this study adds

Heart disease mortality in women increased exponentially with age, with no acceleration at menopause. In men, there was a rapid increase during young adulthood followed by reduced rates of increase

The early rapid acceleration in male heart disease mortality could explain these sex differences rather than menopausal changes in women

Efforts to improve cardiac health in women should focus on their lifetime risk rather than only after menopause

Contributors: DV designed the study, analysed data, drafted the manuscript, and is the data guarantor. DMB, VB, RAM, and PO critically edited the manuscript, and contributed to the interpretation of the analysis.

Funding: DV was supported by the National Center for Research Resources (grant No UL1 RR 025005), a component of the National Institutes of Health.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years, no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Data sharing: Analysis dataset appended, no additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2011;343:d5170

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Web appendix 1: Derivation of models of mortality rates as a function of age

Web appendix 2: Complete abstracted dataset from vital statistics sources

Web appendix 3: Associations between ischaemic heart disease mortality and female breast cancer mortality in US birth cohorts

References

- 1.Barrett-Connor E. Sex differences in coronary heart disease. Why are women so superior? The 1995 Ancel Keys Lecture. Circulation 1997;95:252-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matthews KA, Crawford SL, Chae CU, Everson-Rose SA, Sowers MF, Sternfeld B, et al. Are changes in cardiovascular disease risk factors in midlife women due to chronological aging or to the menopausal transition? J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;54:2366-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bittner V. Menopause, age, and cardiovascular risk: a complex relationship. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;54:2374-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tunstall-Pedoe H. Myth and paradox of coronary risk and the menopause. Lancet 1998;351:1425-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Furman RH. Are gonadal hormones (estrogens and androgens) of significance in the development of ischemic heart disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1968;149:822-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lawlor DA, Ebrahim S, Davey Smith G. Role of endogenous oestrogen in aetiology of coronary heart disease: analysis of age related trends in coronary heart disease and breast cancer in England and Wales and Japan. BMJ 2002;325:311-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pike MC, Spicer DV, Dahmoush L, Press MF. Estrogens, progestogens, normal breast cell proliferation, and breast cancer risk. Epidemiol Rev 1993;15:17-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rauscher FM, Goldschmidt-Clermont PJ, Davis BH, Wang T, Gregg D, Ramaswami P, et al. Aging, progenitor cell exhaustion, and atherosclerosis. Circulation 2003;108:457-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greider CW. Telomeres and senescence: the history, the experiment, the future. Curr Biol 1998;8:R178-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Samani NJ, van der Harst P. Biological ageing and cardiovascular disease. Heart 2008;94:537-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harley CB, Futcher AB, Greider CW. Telomeres shorten during ageing of human fibroblasts. Nature 1990;345:458-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Office for National Statistics. Century mortality (England & Wales 1901-2000) CD. Office for National Statistics, 2010.

- 13.National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2005: with chartbook on trends in the health of Americans. National Center for Health Statistics, 2005:171-95. [PubMed]

- 14.Frost WH. The age selection of mortality from tuberculosis in successive decades. 1939. Am J Epidemiol 1995;141:4-9, discussion 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akaike H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans Automat Contr 1974;19:716-23. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burnham KP, Anderson DR. Multimodel inference: understanding AIC and BIC in model selection. Sociol Methods Res 2004;33:261-304. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dodd GD. American Cancer Society guidelines on screening for breast cancer. An overview. Cancer 1992;69(suppl 7):1885-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Cancer Institute. Working guidelines for early cancer detection rationale and supporting evidence to decrease mortality. National Cancer Institute, 1987.

- 19.US Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to clinical preventive services: an assessment of the effectiveness of 169 interventions. Williams and Wilkins, 1989.

- 20.Benetos A, Okuda K, Lajemi M, Kimura M, Thomas F, Skurnick J, et al. Telomere length as an indicator of biological aging: the gender effect and relation with pulse pressure and pulse wave velocity. Hypertension 2001;37:381-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anversa P, Kajstura J, Leri A, Bolli R. Life and death of cardiac stem cells: a paradigm shift in cardiac biology. Circulation 2006;113:1451-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chimenti C, Kajstura J, Torella D, Urbanek K, Heleniak H, Colussi C, et al. Senescence and death of primitive cells and myocytes lead to premature cardiac aging and heart failure. Circ Res 2003;93:604-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hobbs F, Stoops N. Demographic trends in the 20th Century. US Census Bureau, 2002.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Web appendix 1: Derivation of models of mortality rates as a function of age

Web appendix 2: Complete abstracted dataset from vital statistics sources

Web appendix 3: Associations between ischaemic heart disease mortality and female breast cancer mortality in US birth cohorts