Abstract

Despite large cell-to-cell variations in the concentrations of individual signaling proteins, cells transmit signals correctly. This phenomenon raises the question of what signaling systems do to prevent a predicted high failure rate. Here we combine quantitative modeling, RNA interference, and targeted selective reaction monitoring (SRM) mass spectrometry, and we show for the ubiquitous and fundamental calcium signaling system that cells monitor cytosolic and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) Ca2+ levels and adjust in parallel the concentrations of the store-operated Ca2+ influx mediator stromal interaction molecule (STIM), the plasma membrane Ca2+ pump plasma membrane Ca–ATPase (PMCA), and the ER Ca2+ pump sarco/ER Ca2+–ATPase (SERCA). Model calculations show that this combined parallel regulation in protein expression levels effectively stabilizes basal cytosolic and ER Ca2+ levels and preserves receptor signaling. Our results demonstrate that, rather than directly controlling the relative level of signaling proteins in a forward regulation strategy, cells prevent transmission failure by sensing the state of the signaling pathway and using multiple parallel adaptive feedbacks.

Keywords: absolute quantification of calcium signaling proteins, targeted proteomics, compensation mechanisms in signal transduction networks, cell signaling, protein abundance profiling

Recent studies in mammalian cells and lower eukaryotes showed a significant variation in the expression level of individual proteins between genetically identical cells (1, 2). These variations—often exceeding a factor of 2—likely reflect noise in transcription, mRNA turnover, translation, and protein degradation. This cell-to-cell variability creates a fundamental problem for signal transduction because even small differences in the relative levels of signaling components along a pathway lead to a processive degradation of signal transmission and failed physiological responses. However, cells typically manage to transmit signals correctly, overcoming protein expression variations by unknown mechanisms.

Ca2+ signals regulate fundamental eukaryotic processes that range from secretion, muscle contraction, and memory formation to activation and differentiation of immune cells (3, 4). Our detailed knowledge of the Ca2+ signaling system makes this pathway ideally suited to address the puzzling question of how signal transmission processes can tolerate large variations in the expression level of the underlying signaling components. We hypothesized that additional control principles must exist to explain how the otherwise well-understood Ca2+ signaling system avoids failure and copes with large cell-to-cell variations in protein expression. To keep cells in a signaling-competent state, the Ca2+ signaling system employs a system of pumps and channels to tightly balance Ca2+ fluxes across the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and plasma membrane (PM). The highly coordinated regulation of calcium homeostasis raises the questions of whether the pumps and channels are always expressed at the correct numbers by using shared promoters or coupled protein stability in a forward regulation strategy or, alternatively, whether cells monitor the output of a pathway and use a feedback strategy to adjust the concentrations of individual signaling components.

Results and Discussion

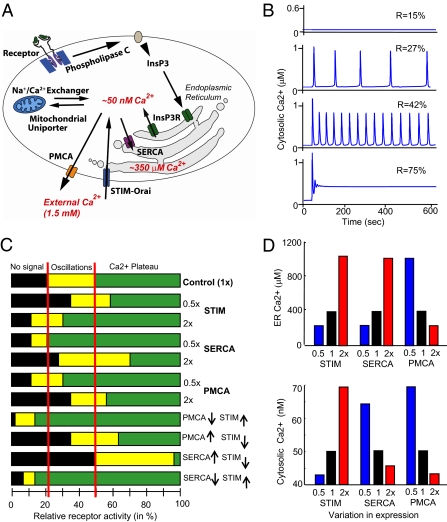

We first determined computationally how the currently known Ca2+ signaling system is affected by variations in protein expression. We used an established Ca2+ signaling model (5) with added terms reflecting the recently discovered stromal interaction molecule (STIM)–Orai Ca2+ influx pathway (Fig. 1A) (6). The model links receptor activation of phospholipase C and the production of the second messenger inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (InsP3) to the InsP3-induced opening of Ca2+ channels (InsP3R) in the ER (4). The resulting drop in ER Ca2+ level activates the ER Ca2+ sensor STIM, which translocates to ER–PM junctions, where it triggers Ca2+ influx into the cytosol through Orai channels (7, 8). PM Ca–ATPase (PMCA) Ca2+ pumps in the PM extrude Ca2+ out of the cells and establish a steep Ca2+ gradient from a basal level in the cytosol of 50 nM to a concentration of 1.5 mM outside the cell. Sarco/ER Ca2+–ATPase (SERCA) Ca2+ pumps in the ER membrane keep the ER filled to a basal Ca2+ level of 350 μM. The model includes positive feedbacks from cytosolic Ca2+ to the InsP3R and to phospholipase C, as well as delayed negative feedback from cytosolic Ca2+ to inhibit InsP3-gated Ca2+ release (5, 9, 10) that together generate receptor-triggered Ca2+ oscillations.

Fig. 1.

Model simulations show that the Ca2+ signaling system fails to function when signaling components are increased or decreased twofold. (A) Schematic of the Ca2+ signaling model. (B) Output of the model at different levels of receptor activation. (C) When STIM, SERCA, and PMCA concentrations were varied from 50% to 200% of their setpoint concentrations (by regulating the synthesis rates), the transition points where receptor activation triggered Ca2+ oscillations or induced the plateau phase varied significantly from the control. In the control, all proteins were expressed at their normal, 1× concentrations. (D) Significant changes in basal ER and cytosolic Ca2+ levels that may affect cell health occurred when twofold changes were made to the synthesis rates of PMCA, SERCA, and STIM.

To test for a role of mitochondrial calcium in regulating basal cytosolic and ER calcium in the Drosophila cells used in this study, we used RNA interference (RNAi) to knock down expression of MICU1, a protein that has been shown to be essential for mitochondrial calcium uptake (11). Consistent with the results in human HELA cells (11), we did not see a statistically significant effect of MICU1 knockdown on basal cytosolic or basal ER calcium levels (SI Appendix, Figs. S2 and S3). However, because mitochondrial calcium is known to modulate the pattern of calcium signals (12) and may regulate basal cytosolic and ER calcium levels in some cell types, the model does include terms describing the two known modes of Ca2+ uptake into mitochondria via a uniporter channel: uptake from the cytoplasm and a more direct transfer of Ca2+ from the ER to mitochondria at ER–mitochondria contact sites (13). Uptake into mitochondria leads to a clipping of Ca2+ transients when they start to exceed a critical level of cytosolic Ca2+. A main mitochondrial Ca2+ extrusion mechanism is likely mediated by a Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (14).

Model simulations showed that weak receptor stimuli have no effect on Ca2+ levels (Fig. 1B, top trace). A further increase in receptor stimulus intensity led to a dramatic phase transition whereby Ca2+ levels underwent a repetitive spiking (oscillation) behavior that increased in frequency as the receptor stimulus increased (middle traces). At even higher levels of receptor activation, the Ca2+ signal transitioned into a plateau phase, in which Ca2+ levels stayed elevated as long as the receptor remained engaged (bottom trace). These oscillation and plateau phases reflect the typical Ca2+ signaling responses observed in many eukaryotic cell types (15). In some cell systems, as well as in our model output, significantly more complex oscillation patterns can be observed than are shown in Fig. 1B—for example, oscillations on top of an elevated baseline or infrequent spikes of varying durations. However, to simplify the output classes, we placed the model outputs into just three categories: no signal, oscillations, and plateaus. If oscillations decayed into an elevated baseline, we considered this output to be in the plateau category. If, however, a plateau switched to and ended in an oscillatory pattern, we considered that output to be in the oscillatory category. Examples of how we categorized the model outputs are given in SI Appendix, Fig. S4. It should be noted that the model describes whole-cell changes in cytosolic, ER, and mitochondrial Ca2+ levels and does not include the effects of spatial distribution of Ca2+ signals or spatial distributions of relevant Ca2+ transport proteins, such as those described in ref. 16.

We introduced into the model twofold variations in the synthesis rates of STIM, SERCA, or PMCA. Markedly, the critical receptor activation levels where cells switched from eliciting no response to triggering oscillations and to inducing a plateau phase shifted significantly from the control case (Fig. 1C). The shifts became even larger and more disruptive as dual and higher-order perturbations were performed, as shown in the example in the lower part of Fig. 1C, with opposing twofold changes in STIM and PMCA or in STIM and SERCA. The need for lower or higher receptor stimuli, together with the reduced range of stimulus intensity over which oscillations occur, show that downstream processes controlled by oscillations, such as secretion or differentiation, would fail to be triggered in most cells if our current model were correct.

Of possibly more serious long-term concern for cell health, perturbations of even a single component caused significant changes in the levels of basal ER and cytosolic Ca2+ (Fig. 1D). This finding is problematic because changes in basal cytosolic Ca2+ can disrupt the normal activities of Ca2+-regulated proteases, phosphatases, and other effectors (17), and changes in basal ER Ca2+ levels lead to protein misfolding and trigger ER stress responses (18, 19) and apoptosis (20). Thus, twofold stochastic variations in the expression of signaling proteins between otherwise identical cells would wreak havoc in the performance of the Ca2+ signaling system as it is currently understood. This “factor-of-two resilience problem” is likely a fundamental challenge that all signaling systems have to resolve.

We considered three plausible hypotheses of how the Ca2+ signaling system could prevent failure. (i) In a “co-expression control hypothesis,” cells would rely on constant relative coexpression of Ca2+ signaling proteins. Coexpression control is often observed when two proteins bind to and stabilize each other. However, many signaling components are spatially separated and cannot effectively use this mechanism. (ii) In a “nodal point control hypothesis,” a single component in the Ca2+ system is targeted by feedback regulation and provides system stability. Nodal points with central importance have been described in many types of complex systems (21). Such a single feedback could, for example, monitor cytosolic Ca2+ and adjust the expression of the PMCA pump to stabilize the system. (iii) In a third “parallel adaptive control hypothesis,” multiple feedback loops would act in parallel. Cells could, for example, monitor cytosolic and ER Ca2+ levels and continuously make multiple but small adjustments to different signaling components to keep the system optimally tuned. However, this type of control mechanism may be challenging for a cell to implement because engineered systems with multiple feedbacks can have high failure rates (22).

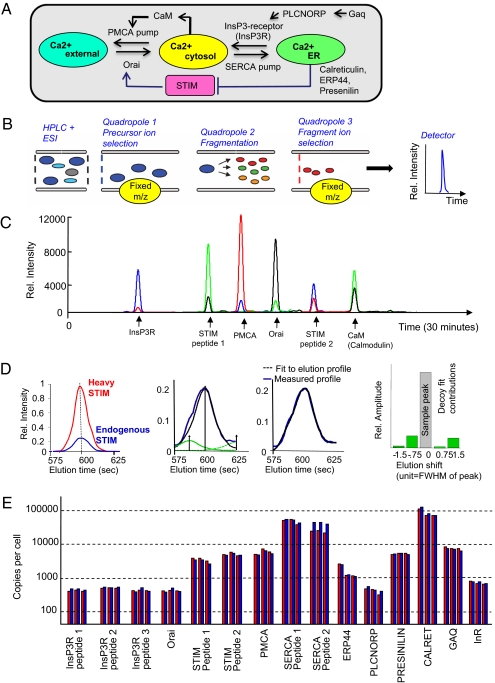

To determine which of these three hypotheses is correct, we investigated the Ca2+ signaling system in Drosophila S2R+ cells, which have the same Ca2+ signaling components as other animal cells (Fig. 2A). The analysis is facilitated in Drosophila, which has only single gene copies of these components compared with the multiple gene copies found in vertebrate cells (23). We quantitatively measured protein concentrations using selective reaction monitoring (SRM) mass spectrometry (Fig. 2 B and C; refs. 24–26) by identifying one or more proteotypic peptides for STIM, PMCA, and SERCA, as well as for a number of additional Ca2+ signaling components and control proteins used for normalization (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Table S1). Heavy isotopically labeled synthesized peptides (27) were added at a known concentration to quantify the corresponding endogenous peptide peak (Fig. 2D and SI Appendix, Table S2). An estimated copy number per cell was derived by fitting the heavy peak to the sample peak (a decoy peak analysis was used to reject noisy peptide transitions) (Fig. 2E and SI Appendix, SI Methods). The Ca2+ pumps PMCA and SERCA (∼8,000 and 80,000 copies, respectively) were significantly more abundant than the Ca2+ channels InsP3R and Orai, which were present at only ∼800 copies per cell. The higher level of SERCA compared with PMCA is consistent with the experimentally observed much higher pump rate into the ER compared with the pump rate out of cells. The ER Ca2+ sensor STIM was present at an almost 10-fold higher concentration than Orai, possibly indicating additional signaling roles or a role in the cooperative activation of Orai by multiple STIMs (28).

Fig. 2.

Selective reaction monitoring (SRM) mass spectrometry determination of copy numbers of important Ca2+ signaling components in Drosophila S2R+ cells. (A) Schematic of the targeted proteins and their regulatory connections. (B) SRM measurements were carried out by using a nano-HPLC and electrospray ionization source coupled to a triple-quadropole mass spectrometer. The transitions (precursor/fragment ion pairs) generated for each targeted peptide were read out as intensities by the detector. (C) A subset of transitions measured by SRM in a typical sample. (D) Fit of the peak of a heavy peptide to the light (endogenous) trace. Time-shifted decoy peaks were used in the fit to quantify background peptide activities. Four decoy shapes were generated by shifting the heavy peptide peak shape to the left and right, respectively. Decoy peaks significantly contributing to the fit indicated noise in the sample trace, and fragments were rejected. (E) Copy numbers of key Ca2+ signaling proteins per S2R+ cell measured in three biological replicates. The red and blue bars show quantitation of two different transitions for each peptide. Measurements of multiple independent peptides are shown for InsP3R, STIM, and SERCA.

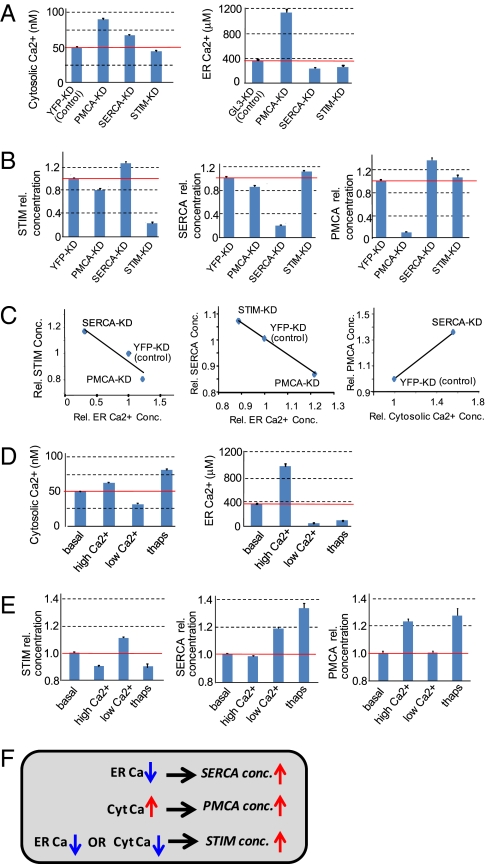

We next directly tested for adaptive mechanisms by using RNAi to knock down SERCA, PMCA, and STIM. Control experiments using SRM mass spectrometry showed that RNAi knockdowns typically led to 70–90% reductions of the targeted protein concentration for the conditions used (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). A reduction in the expression of the Ca2+ pump that transports Ca2+ out of the cell (PMCA) is predicted to directly increase cytosolic Ca2+ and to indirectly increase ER Ca2+. Indeed, knockdown of PMCA increased both cytosolic and ER Ca2+ concentrations (Fig. 3A). Also as expected, SERCA knockdown lowered ER Ca2+ levels by preventing the pumping of Ca2+ into the ER. Lowering ER Ca2+ levels induces store-operated Ca2+ influx into the cell (7), and thus SERCA knockdown also resulted in increased cytosolic Ca2+ levels. STIM knockdown reduced basal cytosolic and ER Ca2+ levels, consistent with STIM's role to enhance Ca2+ influx into cells.

Fig. 3.

Demonstration that multiple parallel adaptive feedback loops exist in the Ca2+ signaling system. The error bars in all plots show SE. (A and B) Effect of RNAi knockdown on cytosolic and ER Ca2+ levels (A) and protein levels (B). Knockdown of YFP or GL3, proteins that are not present in S2R+ cells, were used as controls. (C) The small changes in STIM and SERCA and PMCA protein concentration correlated with Ca2+ level changes, but data in B are not sufficient to determine whether the changes were regulated just by ER or just by cytosolic Ca2+. (D and E) Effect of treating cells for 24 h with low (2.5 mM EGTA plus 2.5 mM Mg2+) and high (10 mM Ca2+) external Ca2+ and thapsagargin addition (1 μM) on cytosolic and ER Ca2+ levels (D) and protein levels (E). (F) Summary of the three identified feedback loops.

Strikingly, knockdown of STIM, PMCA, and SERCA not only reduced the concentration of the targeted protein, but also significantly changed the concentration of the other two components not targeted by the dsRNA (Fig. 3B). STIM expression was reduced by knockdown of PMCA and increased by knockdown of SERCA in the opposite direction to the change in ER Ca2+ level, suggesting that STIM expression is inversely regulated by ER Ca2+ (Fig. 3C). A similar inverse regulation between ER Ca2+ levels and SERCA expression was also observed when STIM or PMCA was knocked down. For PMCA, a plausible interpretation of the data is that the increase in cytosolic Ca2+ mediated by SERCA knockdown increases its expression (Fig. 3C).

To directly determine whether it is the ER or the cytosol Ca2+ that controls PMCA, STIM, and SERCA expression, we exposed cells to high or low external Ca2+ to shift their basal cytosolic and ER Ca2+ levels. High external Ca2+ was expected to increase basal Ca2+ influx and to cause a corresponding increase in basal cytosolic and ER Ca2+ levels. Low external Ca2+ was expected to decrease basal Ca2+ influx and cytosolic and ER Ca2+ levels. We indeed observed these expected changes experimentally (Fig. 3D). To generate an opposing change in ER and cytosolic Ca2+ levels, we used the SERCA inhibitor thapsigargin, which is known to lower ER Ca2+ and thereby increase cytosolic Ca2+ by inducing STIM–Orai-mediated store-operated Ca2+ influx. It should be noted that changes in Ca2+ buffering in the cytosol or ER are likely less important for altering Ca2+ homeostasis because our model shows that such changes have only small effects compared with changes in the ratio between Ca2+ pump and flux rates.

We then used SRM mass spectrometry to measure the effect of direct changes in ER and cytosolic Ca2+ concentration on the protein levels (Fig. 3E). The inverse change in STIM concentration in response to high and low Ca2+ exposure further showed that ER Ca2+ inversely regulates STIM expression. The lowering in STIM concentration after thapsigargin treatment suggested that STIM is not only up-regulated by low ER Ca2+ but also likely suppressed by high cytosolic Ca2+ levels. SERCA expression was increased in low external Ca2+ as well as in the presence of thapsigargin, demonstrating that SERCA expression is directly regulated by the ER Ca2+ level rather than by cytosolic Ca2+. In contrast, PMCA expression changes were only consistent with a regulation whereby an increase in cytosolic Ca2+ enhanced PMCA expression. The three identified feedback loops are summarized in Fig. 3F. Thus, rather than solely relying on regulated coexpression (i) or on a feedback involving a single nodal point (ii), our third hypothesis is likely correct. Multiple parallel adaptive feedback loops sense ER and cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations and adjust the expression levels of STIM, SERCA, and PMCA.

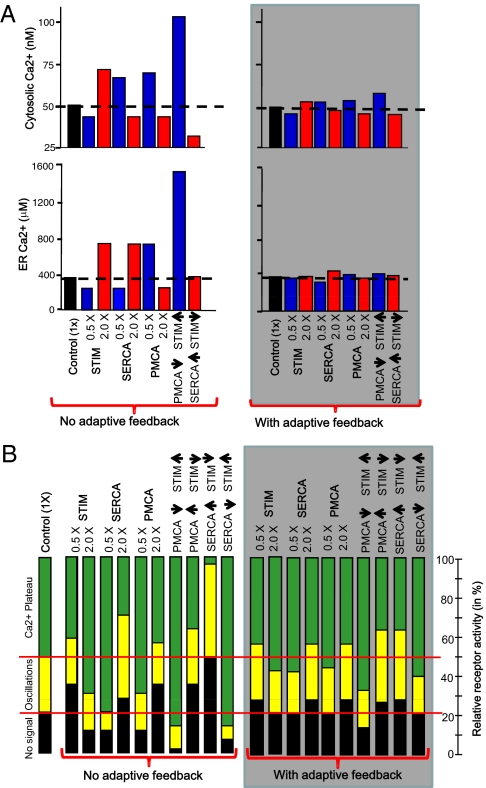

Given the complexity of the nonlinear terms and feedbacks in the Ca2+ signaling system, and the known difficulty in building fail-proof multifeedback systems (22), it was not obvious whether the parallel feedback loops we identified indeed improved the signaling performance. We tested this hypothesis computationally by replacing in the model from Fig. 1 fixed protein concentration parameters with regulated protein synthesis rates and constant degradation rates. We added a modulatory synthesis term that enhanced or reduced the expression rate of PMCA when the cytosolic Ca2+ level increased or decreased, respectively, from a setpoint Ca2+ level (50 nM). A similar term reduced or increased the expression rate of SERCA when the ER Ca2+ level increased or decreased, respectively, from the ER setpoint (350 μM Ca2+). Increases or decreases in either ER or cytosolic Ca2+ levels from the setpoints reduced or increased, respectively, the synthesis rate of STIM. The protein degradation time determined the equilibration time of this system and was assumed to be 10 h. This timescale is much slower than the only minute-long receptor-triggered induction of typical Ca2+ signals, and, thus, the concentration of signaling components did not significantly change during the signaling response itself.

Strikingly, the addition of these three expression feedback loops led to a marked reduction in the changes in basal cytosolic and ER Ca2+ levels when the respective protein synthesis rates were doubled or cut in half. Fig. 4A shows a comparison of the simulated data without adaptive feedback (from Fig. 1D) to the simulated data with adaptive feedback. The twofold perturbations in SERCA, STIM, and PMCA concentrations were then stabilized by the system so that the resulting change in cytosolic and ER Ca2+ levels were within 10% of the median basal level. The power of these adaptive feedback loops in preventing the cell from losing its control of basal cytosolic and ER Ca2+ levels became particularly apparent when multiple perturbations were applied to the system (Fig. 4A, two rightmost bars in each plot).

Fig. 4.

Simulations show that including the identified parallel adaptive feedback loops into the model markedly enhances the reliability of the Ca2+ signaling system in response to changes in the synthesis rates of signaling components. (A) Marked stabilization of both basal cytosolic and ER Ca2+ levels (gray box). (B) Parallel adaptive feedback is well suited to preserve the setpoints where receptor stimuli first triggered Ca2+ oscillations and first triggered a plateau phase. Instead of the marked reduction in the range over which oscillations occurred in the model without adaptive feedback (from Fig. 1C), the signaling system with adaptive feedback (gray box) now shows minimal changes in the responsiveness to receptor stimulation.

Furthermore, with adaptive feedback, the lowest receptor stimuli that triggered oscillations and plateau phases, respectively, now remained closer to those of control cells, preserving the range over which oscillations occurred (Fig. 4B). Thus, these multiple parallel and slow adaptive feedback processes allowed the Ca2+ signaling system to tolerate significant perturbations and to maintain stable basal ER and cytosolic Ca2+ levels, thereby preventing apoptosis. They also allowed receptor stimuli to trigger Ca2+ responses with much less cell-to-cell variability, preventing failure of signal transmission.

Together, our findings identify a unique adaptive principle in the Ca2+ signaling system whereby STIM, SERCA, PMCA, and possibly other signaling components are regulated by multiple, low-amplitude expression feedbacks so that increases or decreases in ER and cytosolic Ca2+ levels slowly adjust the concentrations of key signaling pathway components. Our model calculations showed that parallel adaptive feedback is a powerful means to stabilize basal cytosolic and ER Ca2+ levels and also to reduce the variability in the signaling response between cells. This control principle likely extends to other signaling systems and provides a general explanation of how cells reliably connect receptor inputs to cell function, despite large cell-to-cell variations in the expression of individual signaling components.

Materials and Methods

Information about cell culturing and transfection, preparation of dsRNA, measurement of intracellular free calcium concentrations, and mass spectrometry sample preparation can be found in SI Materials and Methods.

Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) Setups.

SRM analyses were performed by using two different LC-MS setups. One setup consisted of a hybrid triple quadropole/linear ion trap mass spectrometer (4000 QTRAP; Applied Biosystems/MDS Sciex). Chromatographic separations of peptides were performed on a Tempo nano LC system (Applied Biosystems) coupled to a 16-cm fused silica emitter, 75-μm diameter, packed with a Magic C18 AQ 5-mm resin (Michrom BioResources). Peptides (up to 3.5 μg of total protein digest) were separated with a linear gradient from 5% to 30% acetonitrile in 30 or 60 min, at a flow rate of 300 nL/min.

For the second setup, a Proxeon electrospray ionization source was used as an interface between an EASY-nLC Nano-HPLC system (Proxeon) and a TSQ Vantage triple quadrupole MS system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The peptide separation was carried out by using a 10-mm × 0.1-mm C18 trapping column (Proxeon C18; 5 μm, 120 Å) and a 21-cm × 75-μm diameter reverse-phase C18 capillary column (MICHROM; Magic C18; 5 μm, 200 Å). Peptides (up to 5 μg of total protein digest) were separated with a linear gradient from 0 to 45% acetonitrile in 71 min at a flow rate of 300 nL/min. The following mode and tuning parameters were used: polarity, positive; for scheduled SRM, max windows of 5 min and a cycle time of 1 min; Q1 and Q3 were set to 0.7 Th; scan time was set to 0.02s; scan width was set to 0.002 m/z; collision gas pressure was set to 1.5 mTorr; capillary was set to voltage of 2,400 V; temperature of the transfer capillary was set to 270 °C.

For all MS runs, blank runs were performed regularly, in which the same set of transitions was monitored as in the following (sample) run. Blank runs were performed until no signal was detected for all transition traces, in particular, before any measurement of low-abundance proteins.

Peptide and SRM Transition Selection.

Proteotypic peptides and transitions (precursor/fragment ion pairs) were selected primarily by following procedures outlined in ref. 26. We also used inexpensive, crude synthetic peptides from AnaSpec (San Jose, CA) to directly determine how the peptides eluted from the HPLC and how they fragmented to be able to find the peptides in SRM mode. For each peptide of interest, we chose the three transitions with the best signal-to-noise ratio and optimized critical MS parameters (e.g., collision energy, declustering potential) for best sensitivity. The validated and optimized SRM transitions were used to detect and/or quantify the proteins in cell lysates using scheduled SRM mode. By restricting the acquisition of each transition to 2.5 min around its elution time, the time-scheduling feature of the acquisition software enabled the analysis of the 130 transitions in a single run per sample with high sensitivity. SI Appendix, Table S1 shows the list of targeted peptides and transitions. Detailed information of how the peptides were quantified using SRM mass spectrometry can be found in SI Material and Methods.

SRM-Based Quantification.

For quantitative analysis, a heavy-labeled synthetic version of each peptide of interest was custom-ordered from Thermo Scientific. In each peptide, the C-terminal K or R residue was substituted with the corresponding heavy version, resulting in a mass shift of +8 or +10 Da, respectively. The heavy peptides were isotopically labeled, meaning that they coeluted exactly with the endogenous peptides, and the peak areas could be directly ratioed. A known amount of heavy peptides was added to the protein mixtures just before trypsinization (27). The peptide transitions in heavy and light versions were measured by using scheduled SRM. SRM traces were exported as text files out of the Analyst 1.4 or Xcalibur 2.0.7 SP1 software and analyzed by using custom-written MATLAB routines.

Peak areas for the transitions associated with the heavy and light peptides were quantified. Each transition for a given peptide was treated as an independent abundance measurement. Absolute quantification was obtained from the ratio between the light and heavy SRM peak areas, multiplied by the known amount of the added standard. The potential contamination of the heavy peptide preparations with the corresponding unlabeled peptides was tested by injecting the heavy peptides alone and monitoring the transitions for both the heavy and light peptide forms. At the concentration used for quantitative measurements, no signal was detectable in the light transitions.

To carry out relative quantification of each protein during the different siRNA and chemical perturbations, the ratio between the light and heavy SRM peak areas was calculated and normalized by a correction factor. To calculate the correction factor for each sample, the concentrations of 15 abundant proteins that remained constant during the different perturbation conditions were measured by using SRM and averaged. This average was divided by the average concentration of all of the spiked-in heavy peptides to yield a correction factor by which to divide the respective sample.

Results were calculated as the means of the different transitions/peptide, peptides/protein, and replicate cultures ± SE. For each SRM measurement shown in Fig. 3, 8–12 biological replicates were measured. Outlier transitions (e.g., shouldered transition traces or noisy transitions with S/n < 3) were not considered in the calculations.

Computational Model.

Two models were used to simulate basal and receptor-stimulated Ca2+ signaling. The model used in Fig. 1 (model 1) had no adaptive feedback, whereas the adaptive model used for Fig. 4 (model 2) had three slow adaptive feedback loops that monitored basal ER and cytosolic Ca2+ levels and made corresponding adjustments to the expression of SERCA, PMCA, and STIM/Orai.

The adaptive feedback loops for PMCA and SERCA expression included cooperativities of 4, a value that is typically observed for processes mediated by calmodulin and similar Ca2+ effectors. Because STIM is regulated by both ER and cytosolic Ca2+, we used a cooperativity of 2 for each process. In the unperturbed state (1× concentration of proteins), both models had the same starting parameters of 0.05 μM cytosolic Ca2+ and 350 μM ER Ca2+ (corresponding to 2 relative units). After perturbations were applied (twofold increases or decreases in the level of PMCA, SERCA, or STIM in model 1 and twofold increases or decreases in the rate constant of synthesis of PMCA, SERCA, or STIM in the adaptive model, model 2), both models were run in the basal state (R = 0) until the system approached equilibrium (∼300,000 s). This process led to changes in the steady-state ER and cytosolic Ca2+ levels as shown in Figs. 1D and 4A. After equilibration, R was increased to simulate receptor concentration. The model was then run for 300 s (Fig. 4B). The range over which a first spike, oscillations, and the plateau phase were observed were empirically tested by iterative change of the parameters.

MATLAB Simbiology was used to program and run the model simulations. All model equations and constants are presented and described in SI Appendix. The models presented in this manuscript, without and with adaptive feedback, have been uploaded to the European Molecular Biology Laboratory–European Bioinformatics Institute BioModels database (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/biomodels-main/).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Ruedi Aebersold Paola Picotti, Tobias Meyer, Markus Covert, James Ferrell, Sean Collins, and Sabrina Spencer for helpful discussions and careful reading of the manuscript; Drs. Roger Tsien and Amy Palmer for the ER-targeted (D1ER) and mitochondria-targeted (4mtD3cpv) FRET constructs; and Dr. Theodorus Gadella for the turquoise fluorescent construct. We gratefully acknowledge funding from Stanford University (to M.N.T.) and DFG AH 220/1-1 (to R.A.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

Data deposition: The models presented in this manuscript have been uploaded to the European Molecular Biology Laboratory–European Bioinformatics Institute BioModels database, http://www.ebi.ac.uk/biomodels-main/.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1018266108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Niepel M, Spencer SL, Sorger PK. Non-genetic cell-to-cell variability and the consequences for pharmacology. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2009;13:556–561. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raj A, van Oudenaarden A. Nature, nurture, or chance: Stochastic gene expression and its consequences. Cell. 2008;135:216–226. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clapham DE. Calcium signaling. Cell. 2007;131:1047–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berridge MJ. Inositol trisphosphate and calcium signalling mechanisms. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1793:933–940. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Politi A, Gaspers LD, Thomas AP, Höfer T. Models of IP3 and Ca2+ oscillations: Frequency encoding and identification of underlying feedbacks. Biophys J. 2006;90:3120–3133. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.072249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hogan PG, Lewis RS, Rao A. Molecular basis of calcium signaling in lymphocytes: STIM and ORAI. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:491–533. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liou J, et al. STIM is a Ca2+ sensor essential for Ca2+-store-depletion-triggered Ca2+ influx. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1235–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.05.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feske S, et al. A mutation in Orai1 causes immune deficiency by abrogating CRAC channel function. Nature. 2006;441:179–185. doi: 10.1038/nature04702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bezprozvanny I, Watras J, Ehrlich BE. Bell-shaped calcium-response curves of Ins(1,4,5)P3- and calcium-gated channels from endoplasmic reticulum of cerebellum. Nature. 1991;351:751–754. doi: 10.1038/351751a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meyer T, Stryer L. Molecular model for receptor-stimulated calcium spiking. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:5051–5055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.5051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perocchi F, et al. MICU1 encodes a mitochondrial EF hand protein required for Ca(2+) uptake. Nature. 2010;467:291–296. doi: 10.1038/nature09358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Contreras L, Drago I, Zampese E, Pozzan T. Mitochondria: The calcium connection. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1797:607–618. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rizzuto R, et al. Close contacts with the endoplasmic reticulum as determinants of mitochondrial Ca2+ responses. Science. 1998;280:1763–1766. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5370.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palty R, et al. NCLX is an essential component of mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+ exchange. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:436–441. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908099107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woods NM, Cuthbertson KS, Cobbold PH. Repetitive transient rises in cytoplasmic free calcium in hormone-stimulated hepatocytes. Nature. 1986;319:600–602. doi: 10.1038/319600a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petersen OH, Tepikin AV. Polarized calcium signaling in exocrine gland cells. Annu Rev Physiol. 2008;70:273–299. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Demarchi F, Schneider C. The calpain system as a modulator of stress/damage response. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:136–138. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.2.3759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tu H, et al. Presenilins form ER Ca2+ leak channels, a function disrupted by familial Alzheimer's disease-linked mutations. Cell. 2006;126:981–993. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ron D, Walter P. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:519–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pinton P, Giorgi C, Siviero R, Zecchini E, Rizzuto R. Calcium and apoptosis: ER-mitochondria Ca2+ transfer in the control of apoptosis. Oncogene. 2008;27:6407–6418. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barabasi AL, Albert R. Emergence of scaling in random networks. Science. 1999;286:509–512. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leboucher E, Micheau P, Berry A, L'Espérance A. A stability analysis of a decentralized adaptive feedback active control system of sinusoidal sound in free space. J Acoust Soc Am. 2002;111:189–199. doi: 10.1121/1.1427358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yeromin AV, Roos J, Stauderman KA, Cahalan MD. A store-operated calcium channel in Drosophila S2 cells. J Gen Physiol. 2004;123:167–182. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200308982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wolf-Yadlin A, Hautaniemi S, Lauffenburger DA, White FM. Multiple reaction monitoring for robust quantitative proteomic analysis of cellular signaling networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:5860–5865. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608638104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Picotti P, Bodenmiller B, Mueller LN, Domon B, Aebersold R. Full dynamic range proteome analysis of S. cerevisiae by targeted proteomics. Cell. 2009;138:795–806. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lange V, Picotti P, Domon B, Aebersold R. Selected reaction monitoring for quantitative proteomics: a tutorial. Mol Syst Biol. 2008;4:222. doi: 10.1038/msb.2008.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirkpatrick DS, Gerber SA, Gygi SP. The absolute quantification strategy: A general procedure for the quantification of proteins and post-translational modifications. Methods. 2005;35:265–273. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2004.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brandman O, Liou J, Park WS, Meyer T. STIM2 is a feedback regulator that stabilizes basal cytosolic and endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ levels. Cell. 2007;131:1327–1339. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palmer AE, Tsien RY. Measuring calcium signaling using genetically targetable fluorescent indicators. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:1057–1065. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goedhart J, et al. Bright cyan fluorescent protein variants identified by fluorescence lifetime screening. Nat Methods. 2010;7:137–139. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rudolf R, Magalhães PJ, Pozzan T. Direct in vivo monitoring of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ and cytosolic cAMP dynamics in mouse skeletal muscle. J Cell Biol. 2006;173:187–193. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200601160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.