Abstract

The size of red blood cells (RBC) is on the same order as the diameter of microvascular vessels. Therefore, blood should be regarded as a two-phase flow system of RBCs suspended in plasma rather than a continuous medium of microcirculation. It is of great physiological and pathological significance to investigate the effects of deformation and aggregation of RBCs on microcirculation. In this study, a visualization experiment was conducted to study the microcirculatory behavior of RBCs in suspension. Motion and deformation of RBCs in a microfluidic chip with straight, divergent, and convergent microchannel sections have been captured by microscope and high-speed camera. Meanwhile, deformation and movement of RBCs were investigated under different viscosity, hematocrit, and flow rate in this system. For low velocity and viscosity, RBCs behaved in their normal biconcave disc shape and their motion was found as a flipping motion: they not only deformed their shapes along the flow direction, but also rolled and rotated themselves. RBCs were also found to aggregate, forming rouleaux at very low flow rate and viscosity. However, for high velocity and viscosity, RBCs deformed obviously under the shear stress. They elongated along the flow direction and performed a tank-treading motion.

Keywords: Red blood cell, Microchannel, Microfluidic chip, Visualization

Introduction

Microcirculation refers to the blood flow in microvascular network between arterioles and venules. In microcirculation, oxygen and nutrient are delivered to living tissues and metabolic wastes are removed. Therefore, microcirculation plays an important role in the environmental regulation of living tissues and the maintenance of normal physiological functions of cells, tissues and organs.

Blood is a suspension comprising plasma and blood cells. The main content of blood is red blood cells (also called RBCs or erythrocytes), which accounts for 45% of blood volume, 95% of blood tangible composition, and more than 99% of the particulate matter in blood. In large vessels, RBC is negligibly small compared with vessel diameter and blood can be treated as a homogeneous Newtonian fluid because the flow rate of blood is high and whole blood viscosity approaches an asymptotic value with the increase of shear rate. However, blood should be regarded as a two-phase flow system of RBCs suspended in plasma for microcirculation since the size of RBC is of the same order as the capillary diameter in microcirculation and RBCs’ aggregation, as well as deformability, has a great influence on blood rheological properties, especially at low blood flow rate. Abnormal aggregation and deformability of RBCs will lead to a decrease of blood flow rate and increase of blood viscosity to improve the probability of microcirculation disturbance. Long-term microcirculation disturbance is implicated in many diseases, such as coronary heart disease, phlebitis, etc. In this sense, it is of great physiological and pathological significance to investigate the effects of deformation and aggregation of RBCs on microcirculation.

An RBC is biconcave in shape with a disk diameter of 6∼8 μm and a thickness of 2 μm. The RBCs’ responsibility is to carry oxygen to the tissues and remove waste carbon dioxide. Its unique biconcave shape gives small volume and large surface, and the induced large surface-to-volume ratio will allow the erythrocyte to contain more hemoglobin, which is helpful to increase the rate of diffusion O2 and CO2. Usually, a typical erythrocyte has a volume of 90 fL with a surface area of about 136 μm2, which gives a surface-to-volume ratio of about 1.5 μm − 1. Mature RBCs consists of membrane and cytoplasm without a nucleus. The RBC membrane consists of 52% protein, 40% lipid, and 8% carbohydrate [1], which is responsible for many of the physiological functions and mechanical properties of the cell. The RBC membrane consists of membrane skeleton and lipid bilayers. The former is a multi-protein complex formed by structural proteins. It interacts with the lipid bilayer and transmembrane proteins to provide the RBC with strength and plasticity [2]. The lipid bilayer is a thin membrane made of two layers of phospholipids molecules. These membranes are flat sheets that form a continuous barrier around cells. The lipid molecules’ good potential of lateral movement, rotating motion, fatty acid chain flexibility, and turnover movement make the RBC membrane have a strong fluidity, which ensures RBCs can deform plastically with blood flow and even pass through microvascular vessels with a smaller diameter than themselves. In microcirculation, an RBC can deform itself to a parachute, bullet, slipper shape, etc. The deformability of RBCs is an important factor affecting the high shear blood viscosity. Depressed RBC deformability will increase blood viscosity and flow resistance, which will lead to many cardio-cerebrovascular diseases, such as myocardial infarction and apoplexy [3].

Common methods to measure the deformability of RBCs include aspiration of cells into micropipettes, filtration of cells with microporous membranes, viscometry of cell suspensions, laser diffraction methods, deformation of cells under fluid shear stress, and so on [4]. Recently, microfluidics has been the subject of a vast body of researchers with the rapid development of micro-electro mechanical systems (MEMS). Detections and analysis with microfluidic technology have many advantages, such as low sample reagent cost, high processing control accuracy, and rapid response time. Based on the MEMS technology, a micro total analysis system (μTAS) can serve many useful applications in biological field such as cytological test and DNA analysis [5]. For blood rheology, many researchers have attempted to study the rheological properties of RBCs with silicon microchannels. Shevkoplyas et al. [6] designed and fabricated a microfluidic chip with a network of microchannels, and the flow of red and white blood cells in this network was visualized by high-speed camera. Parachute and bullet shapes, as well as rouleaux formation, of red blood cells were observed in their experiment. Shelby et al. [7] designed an apparatus to test single cell deformability in elastomeric straight microchannels with squared sections of 2 μm depth and various widths (between 2 and 8 μm). Drochon [8] obtained the relationship between the RBC velocity and deformed shape under different flow strengths, suspending medium viscosity and cell membrane elasticity using the cell transit analyzer. Kruchenok et al. [9] observed the orientation of individual RBCs in interference fringes and found that RBC rouleaux undergo disaggregation under the action of interference laser fields. Lima et al. [10] measured velocity distribution of RBC suspension flow in a microchannel with a 0.1 × 0.1 mm2 cross-section by confocal micro-PIV. They indicated that microchannels with dimensions on the order of 100 μm still obey macroscale flow theory. Korin et al. [11] studied the flow behavior of RBC suspension in a straight microchannel with a 0.05 × 1 mm2 rectangular cross-section. The influence of shear stress on RBC shape has been studied and good agreement was obtained between experimental measurement and numerical simulation. Their research revealed that RBCs’ deformability under high viscosity shear conditions is insensitive to the change of inner viscosity within the physiological range and is highly affected by RBC shear modulus. This conclusion indicated that the relationship between shear rate and RBC deformability index could be a useful tool to estimate membrane mechanical properties, which will help diagnose of blood disorders. Fujiwara et al. [12] measured individual trajectories of RBCs in a concentrated suspension of up to 20% hematocrit (Hct) through a stenosed microchannel using confocal micro-PTV. The microchannel had a square cross-section with a side length of 50 μm, and the stenosis was 35 μm high, 30 μm wide, and 50 μm in depth. Their results indicated that the trajectories of healthy RBCs became asymmetric before and after the stenosis and this asymmetry was greater in lower Hct.

So far, the experiments of RBC deformation have been mainly conducted in the straight or stenosed microchannels. In the present work, the flow behavior of RBC suspension will be visualized in a microfluidic chip, which consists of microchannels with straight, divergent, and convergent sections. High-quality images of RBC motion and deformation were recorded by microscope and high-speed camera. RBCs’ rheological properties are investigated under different viscosity, hematocrit, and flowrate.

Materials and methods

Experimental device

In this work, a microfluidic experimental system with functions of flow control, image capture and data acquisition is established to obtain high-resolution images of RBCs’ motion and deformation.

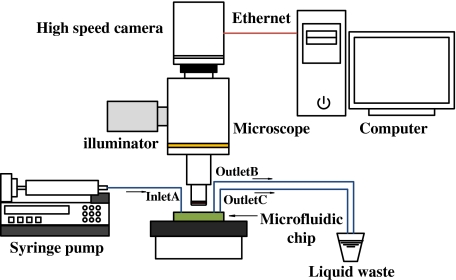

The schematic of the experiment setup is shown in Fig. 1. The RBC suspension was injected into the microchannel system as a pulseless steady flow by a Harvard PHD2000 syringe pump with a flow rate that can be controlled precisely (control precision is 0.35%). After passing though the microchannel, the suspension was discharged into a liquid waste. In the microchannel, the motion and deformation of RBCs are captured by a Leica DMI 500M microscope and recorded by a Redlake HG-100k high-speed camera with resolution of 1,506 × 1,506 pixels at 60∼200 fps. Images were transferred onto a computer by Ethernet and then analyzed by specialized image-processing software.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of the experimental setup

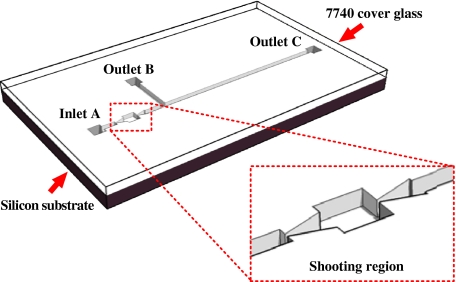

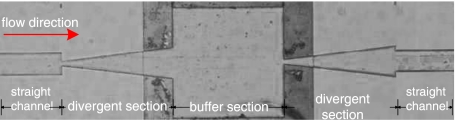

Figure 2 illustrates the structure of the microfluidic chip, which is fabricated by etching microchannels on the silicon substrate and then bonded with a 7740 glass cover. Compared to a traditional machining processing method, this MEMS technology can provide a smoother channel surface (surface roughness is less than 1 μm). The image of the test section photographed with a 5× objective lens is shown in Fig. 3. The shooting region consists of straight, divergent and buffer microchannels, which has a rectangular cross-section with depth of 40 μm. The width of straight channel was 200 μm and the narrowest width was 40 μm in the divergent and convergent sections. In our experiment, we mainly focused on RBCs’ motion in straight channel and RBCs’ movement from straight to convergent section. In this process, RBCs moved from low- to high-speed flow regions, and would deform remarkably.

Fig. 2.

Microfluidic chip

Fig. 3.

Test section of the microchannel

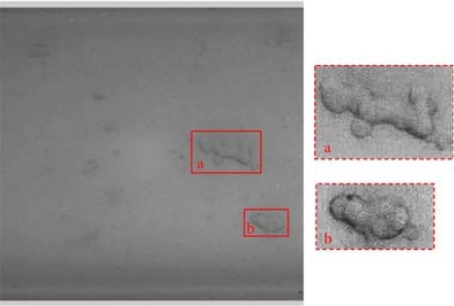

In our experiment, the narrowest part of the microchannel was liable to be contaminated and blocked by RBCs because of their aggregation and adhesion on the channel wall. As shown in Fig. 4a, once the channel was completely blocked, the problem could be solved by heating the microfluidic chip in a high-temperature water bath for half an hour, and then cleaning by high velocity absolute ethanol, which could reduce the surface viscosity of the channel wall and dissolve organic impurities.

Fig. 4.

Microchannel blocking and cleaning. a Channel blocking; b after cleaning

Before the experiment, we first washed the channel surface with a strong acid and alkali, such as aqua regia, sodium hydroxide, and an organic solvent like trichloroethylene to ensure no impurity adhered to the channel wall. Then, we flushed the microchannel with deionized water and phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Lastly, the microchannel was washed by 1% albumin solution which can precoat the channel wall to reduce the adhesion of cells to silicon substrate and cover glass [13].

Preparation of RBC suspension

Firstly, heparin was added into fresh blood obtained from healthy adult volunteers for anticoagulation. Afterwards, RBCs were separated from the sample by centrifugation and aspiration of the plasma as well as buffy coat. Then, the RBCs were washed three times in PBS, which is an isotonic salt solution to balance the osmotic pressure and maintain the ionic strength as well as pH value so as to keep a healthy physiological environment for RBCs. Finally, we suspended RBCs in PBS to obtain hematocrits of 0.4%, 1%, and 3%. After preparation, RBCs suspension was stored at 4°C and the experiment was performed at room temperature. To investigate the influence of viscosity on RBC deformability, polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) was added to individual samples by 8% (mass) to increase the viscosity of RBC suspension. Through the measurement by a double concentric cylinder rheometer (TA, US), it is found that the viscosity of the RBC suspension increased from 0.93 to 1.48 mPa s with the addition of PVP.

Results and discussions

Generally, plasma proteins in blood have the function of bridge-link to make RBCs aggregate and show rouleaux, reticular, and branchlike formations. In our experiment, RBC suspension (with PVP) was pumped into the channel with flow rate from 0.0046 ml/h to 0.1 ml/h after washing the microchannel with albumin solution. The corresponding flow velocities in the straight channel are 0.16 and 34.7 mm/s, respectively. As shown in Fig. 5, RBCs’ aggregation was observed at the right side of the image. At that moment, the mean velocity in the channel was 0.16 mm/s, which was lower than the normal blood flow velocity in microvascular vessels. Disaggregation of RBCs was found by gradually increasing flow rate. When the flow rate was higher than 0.1 ml/h, RBCs’ aggregation disappeared completely.

Fig. 5.

RBCs aggregation in the microchannel (hematocrit: 1%, flow rate: 0.0046 ml/h)

Deformation of RBC

In the experiment, we firstly compared RBC motion morphology under different shear stress. As shown in Fig. 6a, RBCs preserved a standard biconcave disc shape under low flow rate and low viscosity (without PVP). This shape has a high surface-to-volume ratio, which is helpful to RBCs’ plastic deformation and can provide a large gas-exchange area. Figure 6b shows RBCs' shape under high flow rate and high viscosity (with PVP). Cells were elongated by a higher shear stress and deformed into a flattened ellipsoidal shape. This motion morphology of RBC is usually described as tank-treading motion, which is caused by membrane’s rotation around the interior of the cell.

Fig. 6.

RBCs’ deformation under different flow rate and viscosity: a hematocrit 1%, flow rate 0.0046 ml/h, without PVP; b hematocrit 1%, flow rate 1.0 ml/h, with PVP

Figure 7 shows snapshots of RBCs passing though the divergent section of the channel; an RBC near the channel junction was marked out to analyze. It can be seen that flow velocity was very low near the wall in the straight channel, so RBC can maintained its biconcave disc shape (Fig. 7a). When it was moving into the divergent section from the straight channel, the flow velocity increased greatly because of the sudden convergence of the channel width. Thus, the RBC shape was elongated gradually (Fig. 7b) and finally turned into a flattened ellipsoidal shape (Fig. 7c) in the divergent section.

Fig. 7.

Deformation process of RBCs’ passing though the convergent section of the channel

Common motion form of RBC

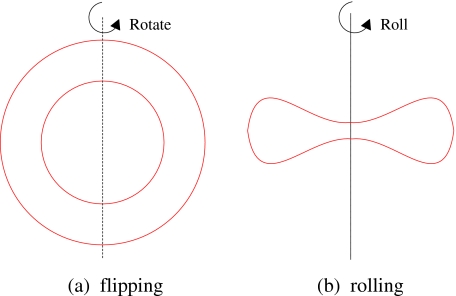

When suspended in a medium with lower viscosity than cytoplasm, RBC will perform a flipping motion [11]. It not only deforms toward its direction of motion, but also rotates and rolls. Figure 8 is a schematic diagram of RBC rotation and rolling. RBC rotation occurs around its arbitrary symmetric axis on the axisymmetric plane (Fig. 8a). Meanwhile, RBC also rolls around its axisymmetric axis, as shown in Fig. 8b.

Fig. 8.

Schematic diagram of RBCs’ rotation and rolling

Figure 9 shows the process of RBC rotation in our experiment. The two RBCs that are marked by red squares rotated in successive half cycles. The process of RBC rolling is presented in Fig. 10. RBCs were always observed to flip and roll simultaneously.

Fig. 9.

The rotation of RBC

Fig. 10.

The rolling motion of RBC

A problem worth pointing out is that the direction of the axis that RBCs rotate around are not uniform through the whole channel. In our experiment, we found that the flipping axes of most RBCs near the wall were toward the normal direction of their direction of motion (Fig. 11). For the RBCs near the centerline of the channel, the flipping axes were toward their direction of motion (Fig. 12). RBC rotation can be explained by the parabolic velocity distribution of RBC suspension. Velocity difference exerted on RBCs adjacent to the wall was higher, so the flipping of RBCs was more obvious. However, up to the present, no reasonable explanation has been advanced for RBC rolling [13].

Fig. 11.

RBCs rotation near the channel wall

Fig. 12.

RBCs rotation near centerline of the channel

Fahraeus–Lindqvis effect and RBCs axis concentrate

In 1931, Fahraeus and Lindqvis found that in narrow channels less than about 0.3 mm in diameter, the decrease of apparent viscosity of blood correlates with the decrease in channel diameter. This phenomenon is the so-called Fahraeus–Lindqvis effect [14, 15]. A common explanation for this phenomenon is the tubular pinch effect [16] or the plasma skimming effect [17, 18]. The tubular pinch effect is the phenomenon in which, during laminar flow of suspensions through a circular channel, particles will migrate into a concentric annular region with the width about 60% of the channel.

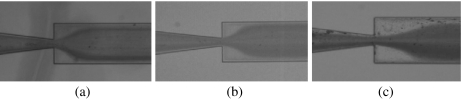

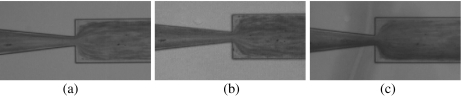

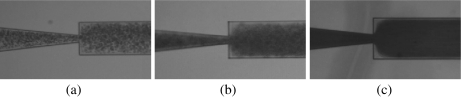

In the experiment, as shown in Fig. 13, this phenomenon was observed at pumping velocity of 1 ml/h. When RBCs moved into the straight channel from divergent section of the channel, they concentrated at the axis of the microchannel and a plasma layer with no RBCs was formed adjacent to the inner wall of the microchannel. This plasma layer can decrease the apparent viscosity of blood and have a lubricating effect on microcirculation. Figure 14 presents the RBC distribution at flow rate 0.15 ml/h. It can be seen that with the reduction of RBC flow rate, the aggregation at the channel axis was decreased and the plasma layer got thinner. When the flow rate reduced to 0.012 ml/h (Fig. 15), the tubular pinch effect almost disappeared. With decreasing flow rate, the velocity of RBCs decreased as well. More and more RBCs squeezed at the narrowest part of the channel, which led to the increase of local concentration and flow resistance at the divergent section and increase the possibility of channel blockage.

Fig. 13.

Tubular pinch effect of RBC at flow rate 1 ml/h: a hematocrit 8%, b hematocrit 10%, c hematocrit 15%

Fig. 14.

Tubular pinch effect of RBC at flow rate 0.15 ml/h: a hematocrit 8%, b hematocrit 10%, c hematocrit 15%

Fig. 15.

Tubular pinch effect of RBC at flow rate 0.012 ml/h: a hematocrit 8%, b hematocrit 10%, c hematocrit 15%

Conclusions

In this research, a microfluidic experiment setup was constructed to observe the flow behavior of RBCs in suspension in a microchannel by capturing images of RBC motion morphology. RBC aggregation and deformation were studied under different flow rate, hematocrit, and viscosity. The conclusions are as follows:

The aggregation of RBCs happens under condition of low flow rate (0.0046 ml/h) and high viscosity (with PVP). With flow velocity increasing, RBCs will disaggregate under high shear stress. When the flow rate is higher than 0.1 ml/h, RBC aggregation disappears completely.

Under low flow rate and viscosity condition, RBCs will maintain their biconcave disc shape, rotate and roll simultaneously with their motion.

Under high flow rate and viscosity condition, RBCs will perform flattened ellipsoidal shape and tank-treading motion.

Tubular pinch effect is observed: RBCs concentrate at the axis of the microvessel and a plasma layer with no RBCs is formed adjacent to the inner wall of microchannel. This effect can be weakened by decreasing the flow velocity. When the flow rate is lower than 0.012 ml/h, the tubular pinch effect disappears completely.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (50676079, 50821064) and the Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University (NCET-07-0661).

Contributor Information

Bin Chen, Phone: +86-29-82660876, FAX: +86-29-82669033, Email: chenbin@mail.xjtu.edu.cn.

Fang Guo, Email: ralphguo.1984@stu.xjtu.edu.cn.

Hao Xiang, Email: xianghao@stu.xjtu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Freitas, R.A. Jr.: Cell membrane. In: Freitas, R.A. Jr.(ed.) Nanomedicine, Vol. I: Basic Capabilities. Landes Bioscience, Georgetown (2006). Section 8.5.3.2

- 2.Pawlowski PH, Burzyn B, Zielenkiewicz P. Theoretical model of reticulocyte to erythrocyte shape transformation. J. Theor. Biol. 2006;243:24–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mi XQ, Chen JY, Zhou LW. Effect of low power laser irradiation on disconnecting the membrane-attached hemoglobin from erythrocyte membrane. J. Photochem. Photobiol., B. 2006;83:146–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2005.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Avishay B, Natanel K, Alexander L, et al. The rheologic properties of erythrocytes: a study using an automated rheoscope. Rheol. Acta. 2007;46:621–627. doi: 10.1007/s00397-006-0146-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burns MA, Johnson BN, Brahmasandra SN, et al. An integrated nanoliter DNA analysis device Science 1998282484–487.1998Sci...282..484B 10.1126/science.282.5388.484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shevkoplyas SS, Gifford SC, Yoshida T, et al. Prototype of an in vitro model of the microcirculation. Microvasc. Res. 2003;65:132–136. doi: 10.1016/S0026-2862(02)00034-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shelby JP, White J, Ganesan K, Rathod PK, Chiu DT.A microfluidic model for single-cell capillary obstruction by Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 200310014618–14622.2003PNAS..10014618S 10.1073/pnas.2433968100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drochon A. Use of cell transit analyser pulse height to study the deformation of erythrocytes in microchannels. Med. Eng. Phys. 2005;27:157–165. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2004.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kruchenok JV, Bushuk SB, Kurilo GI, Nemkovich NA, Rubinov AN. Orientation of red blood cells and rouleaux disaggregation in interference laser fields. J. Biol. Phys. 2005;31:73–85. doi: 10.1007/s10867-005-6732-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lima R, Shigeo W, Tsubota K, et al. Confocal micro-PIV measurements of three-dimensional profiles of cell suspension flow in a square microchannel Meas. Sci. Technol. 200617797–808.2006MeScT..17..797L 10.1088/0957-0233/17/4/026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korin N, Bransky A, Dinnar U. Theoretical model and experimental study of red blood cell (RBC) deformation in microchannels. J. Biomech. 2007;40:2088–2095. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujiwara H, Ishikawa T, Lima R, et al. Red blood cell motions in high-hematocrit blood flowing through a stenosed microchannel. J. Biomech. 2009;42:838–843. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang C, Wang X, Ye P. 3rd IEEE Int. Conf. on Nano/Micro Engineered and Molecular Systems. Sanya, China: IEEE Xplore; 2008. The transport and deformation of blood cells in microchannel; pp. 116–119. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fahraeus R, Lindqvist T. The viscosity of blood in narrow capillary tubes. Am. J. Physiol. 1931;96:562–568. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldsmith HL. Red cell motions and wall interactions in tube flow. Fed. Proc. 1971;30:1578–1590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aoki H, Kurosaki Y, Anzai H. Study on the tubular pinch effect in a pipe flow: I. Lateral migration of a single particle in laminar Poiseuille flow. Bulletin of JSME. 1979;22:206–212. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pries AR, Ley K, Gaehtgens P. Generalization of the fahraeus principle for microvessel networks. Am. J. Physiol. 1986;251:1324–1332. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1986.251.6.H1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmid-Schonbein GW, Skalak R, Usami S, Chien S. Cell distribution in capillary networks. Microvasc. Res. 1980;19:18–44. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(80)90082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]