Abstract

A proportional balance between αβ and γδ T cell subsets in the periphery is exceedingly well maintained via a homeostatic mechanism. However, a cellular mechanism underlying the regulation remains undefined. We recently reported that a subset of developing γδ T cells spontaneously acquire IL-17-producing capacity even within naïve animals via a TGFβ1-dependent mechanism, thus considered ‘einnate’ IL-17-producing cells. Here we report that γδ T cells generated within αβ T cell (or CD4 T cell)-deficient environments displayed altered cytokine profiles; particularly, ‘einnate’ IL-17 expression was significantly impaired compared to those in wild type mice. Impaired IL-17 production in γδ T cells was directly related to the CD4 T cell deficiency, because depletion of CD4 T cells in wild type mice diminished and adoptive CD4 T cell transfer into TCRβ−/− mice restored IL-17 expression in γδ T cells. CD4 T cell-mediated IL-17 expression required TGFβ1. Moreover, Th17 but not Th1 or Th2 effector CD4 T cells were highly efficient in enhancing γδ T cell IL-17 expression. Taken together, our results highlight a novel CD4 T cell-dependent mechanism that shapes the generation of IL-17+ γδ T cells in naïve settings.

Keywords: CD4 T cells, γδ T cells, IL-17, TGFβ1

Introduction

γδ T cells constitute less than 5% of the total peripheral T cells in mice and human, and our understanding of these rare lymphocytes is poor. We and others recently reported that a subset of γδ T cells in naïve animals spontaneously acquire a capacity to express proinflammatory cytokines, IL-17 or IFNγ, which is in good contrast to CD4 T cells in which the expression is induced only after an antigen-mediated activation/differentiation process 1–5. Interesting is that IL-17 expression in γδ T cells is acquired during thymic development via a TGFβ1-dependent mechanism 6. In the periphery, IL-17+ γδ T cells are maintained at a constant level, although a mechanism that governs the maintenance remains uncertain. γδ T cells have been implicated to play critical roles in protecting hosts from bacterial infection by recruiting neutrophils 7–9. Recently it was also shown that γδ T cells are capable of amplifying the generation of autoreactive Th17 CD4 T cells, thus exacerbating Th17-dependent autoimmunity,10, 11. Therefore, understanding how cytokine production in γδ T cells is regulated and maintained is of crucial importance.

Despite obvious disparities between γδ and αβ T cells, they seem to cooperate (and/or counter-regulate) their development and functions in many ways. It was shown that αβ T cell progenitors (CD4+CD8+ double positive thymocytes) play key roles in generating γδ T cells in the thymus via a mechanism involving lymphotoxin (LT) β 12, 13. Functionally, γδ cells developed in the absence of DP thymocytes (i.e., TCRβ−/−) displayed altered gene expression profiles, with impaired proliferation and IFNγ production following in vitro stimulation 12, 13. Inversely, γδ T cells were also shown to regulate the development of IL-17+ CD4 (Th17) cells 10, 11. However, whether αβ T cells contribute to the generation of IL-17+ γδ T cells has not been examined.

In this study we investigated the development and the cytokine profiles of γδ T cells from various T cell-deficient animals to examine a potential cross-regulation mechanism between the T cell subsets and uncovered a novel CD4-dependent mechanism that shapes the generation of IL-17+ γδ T cell subsets in naive settings.

Results

Generation of γδ T cells is enhanced without αβ T cells

Consistent with previous reports 14, 10~50-fold more γδ T cells were found in the secondary lymphoid tissues of TCRβ−/− mice than in wild type mice; ~10-fold increase in the spleen and ~50-fold increase in the LNs (Fig. 1A). The increase was already noticeable in the thymus (Fig. 1A). The expression of active cell cycle marker, Ki-67, was substantially higher in γδ T cells of TCRβ−/− compared to those cells of wild type mice (Fig. S1). Similar results were also observed in another αβ T cell-deficient TCRα−/− mice (data not shown). Such an increase in γδ T cell generation was not found in mice deficient in either CD4 or CD8 T cells, MHC II−/− and β2m−/− mice, respectively. As shown in Fig. 1B, the total numbers of γδ T cells in the lymphoid tissues remained unchanged in wild type, MHC II−/−, and β2m−/− mice, suggesting that γδ T cell development and expansion is only enhanced when both αβ T cell subsets are absent. When either CD4 or CD8 T cells are present, γδ T cell generation is controlled as seen in wild type mice. Consistent with this result, homeostatic proliferation of γδ T cells was induced only in the absence of both αβ and γδ T cells 15. In γδ T cell-deficient TCRδ−/− mice, adoptively transferred γδ T cells failed to undergo homeostatic proliferation, suggesting that αβ T cells of the recipients are capable of inhibiting the proliferation. Notwithstanding the significant elevation of γδ T cell cellularity in TCRβ−/− mice, the overall profiles of Vγ repertoire remained relatively similar between wild type and TCRβ−/− mice, although the proportion of Vγ1 and Vγ7 γδ T cells seemed altered in TCRβ−/− mice (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1. γδ T cells in various T cell-deficient mice.

(A) Groups of wild type (filled symbol) and TCRβ−/− (open symbol) mice were sacrificed and the total numbers of γδ T cells in the indicated lymphoid tissues (SPL, spleen; pLN, peripheral LN; mLN, mesenteric LN, and thymus) were enumerated by FACS analysis. Each symbol represents individual mouse. (B) Total numbers of γδ T cells in WT, MHC II−/−, and β2m−/− mice were calculated by FACS analysis. Each symbol represents individually tested mouse. (C) Peripheral LN cells were stained for γδ TCR plus indicated Vγ chains. The mean ± SD was calculated from four individually tested mice.

Cytokine profiles of γδ T cells in TCRβ−/− mice

Some γδ T cells in naïve animals produce effector cytokines including IFNγ and IL-17 following stimulation 1, 3, 16. A previous study reported impaired γδ T cell IFNγ production when γδ T cells from TCRβ−/− mice were stimulated with anti-CD3 Ab in vitro 13. However, we noticed that IFNγ expression was significantly enhanced when γδ T cells isolated from TCRβ−/− mice were ex vivo stimulated (Fig. 2A). Enhanced γδ T cell IFNγ expression was similarly found in other T cell-deficient TCRα−/− and CD4−/− mice (data not shown). Interestingly, IL-17 expression by γδ T cells was significantly reduced in TCRβ−/− compared to wild type mice (Fig. 2A). Likewise, reduced IL-17 expression was also noticed in other T cell-deficient TCRα−/− and CD4−/− mice (data not shown). Interestingly, it was previously shown that the lack of DP thymocytes impairs normal development of γδ T cells in TCRβ−/−, a defect not found in TCRα−/− mice 13. However, we reproducibly found that the total numbers of IFNγ- and IL-17- producing γδ T cells in TCRβ−/− and TCRα−/− mice were similar (Fig. 2B), suggesting that DP thymocytes do not affect the development of cytokine producing γδ T cells. Additional studies on the γδ T cell development in various conditions will be needed to clarify the discrepancy. Notably, we found no difference in IL-17+ γδ T cells in the gut associated tissues (intraepithelial cells and lamina propria γδ T cells), suggesting that the defect of IL-17+ γδ T cells in TCRβ−/− mice could not be attributed to different homing pattern of γδ T cells (Fig. S2). Consistent with the FACS results, peripheral LN γδ T cells purified from TCRβ−/− mice expressed less il17a and more ifng mRNA (Fig. 2C). Thus, altered cytokine profile seen in TCRβ−/−γδ T cells is not an artifact of ex vivo restimulation.

Figure 2. Cytokine and proliferation profiles of γδ T cells.

(A) IFNγ and IL-17 production from the indicated lymphoid tissues of wild type and TCRβ−/− mice was measured after in vitro stimulation with PMA plus ionomycin as described in the Materials and Methods. Representative FACS dot plots of intracellular IL-17- and IFNγ-expression of γδ T cell gated population the indicated tissues are shown. The mean ± SD was calculated from three to ten independent experiments. **, p<0.01. (B) Absolute numbers of cytokine producing γδ T cells of the indicated tissues were calculated. (C) mRNA expression of IL-17 and IFNγ in pLN γδ T cells FACS sorted from wild type or TCRβ−/− mice was examined by real time PCR. (D) CFSE labeled γδ T cells (from wild type or TCRβ−/− mice) were transferred into Rag1−/− recipients. CFSE dilution was determined 7 days post transfer. CFSE profiles shown are representative from two independent experiments.

Nevertheless, we observed that the proliferation of γδ T cells was not affected. This conclusion was made from experiments in which FACS sorted γδ T cells were transferred into lymphopenic Rag1−/− recipients and examined for homeostatic proliferation 15, 17. Both γδ T cells isolated from wild type and TCRβ−/− mice underwent equivalent homeostatic proliferation in Rag1−/− recipients (Fig. 2D). Although it was previously reported that the proliferation of TCRβ−/− γδ T cells was impaired when stimulated with anti-CD3 in vitro 13, no defects were found in proliferation in vivo. Consistent with this finding, French et al. recently reported an efficient homeostatic proliferation of γδ T cells isolated from TCRβ−/− mice 18.

γδ T cell cytokine expression from animals of different age

Because some TCRβ−/− mice are known to spontaneously develop inflammation in the intestine beginning at ~4–6 months of age 19, we examined if altered cytokine profiles seen above are the result of inflammation that might have developed in the intestine. Notably, all TCRβ−/− mice used in this study were ~2 months of age, and did not show any signs of disease at the time of experiments. We measured cytokine expression in mice of different ages. As shown in Figs. 3A and S3, thymic expression of IL-17 in γδ thymocytes was similarly regulated in both wild type and TCRβ−/− mice, although the proportion of IL-17+ γδ T cells in the periphery was higher in wild type mice. Interestingly, γδ T cell IFNγ expression in the periphery was similar prior to the 3 weeks of age; however, it became greater in TCRβ−/− mice starting at 4 weeks of age (Fig. 3A and S3). Thymic IFNγ expression in γδ T cells was relatively low; however, slightly higher expression was consistently found in TCRβ−/− mice (Fig. 3A and S3). Therefore, the altered cytokine profiles seen in TCRβ−/− γδ T cells are not the consequence of dysregulated inflammation in vivo. In terms of absolute numbers of cytokine-expressing γδ T cells, however, significantly higher levels of IFNγ-/IL-17-expressing γδ T cells were consistently found in TCRβ−/− mice regardless of their age, supporting an earlier finding of elevated expansion of γδ T cells without αβ T cells (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3. Profiles of cytokine producing γδ T cells.

(A) Cytokine expression of γδ T cells from mice of different age. Cells from the indicated lymphoid tissues (thymus or pLN) of wild type and TCRβ−/− mice of the indicated age were in vitro stimulated with PMA plus ionomycin. The proportion of as well as the absolute numbers of IFNγ and IL-17 production was determined by intracellular cytokine staining. The mean ± SD of cytokine expressing γδ T cells from 4–5 individually tested mice are shown. (B) Surface phenotypes of IFNγ- and IL-17- producing γδ T cells. Cells from the indicated lymphoid tissues of wild type, TCRβ−/−, and TCRα−/− mice were in vitro stimulated with PMA plus ionomycin and stained for CD27 and cytokines. Data shown are representative from 2–3 individually tested mice. Similar results were obtained from another independent experiment. N.D., not done.

Surface phenotypes of IFNγ- and IL-17-producing γδ T cells

It was recently reported that CD27 and CCR6 expression in γδ T cells marks IFNγ- and IL-17 production in γδ T cell subsets, respectively 2, 16. Indeed, IFNγ-producing γδ T cells were CD27+ CCR6-, while IL-17-producing γδ T cells were CD27- CCR6+ (Fig. S4). Phenotypes of IFNγ- and IL-17- producing γδ T cells were thus examined in different strains of mice. In all mice tested (wild type, TCRβ−/− and TCRα−/−), IFNγ-producing γδ T cells were CD27+ and IL-17-producing γδ T cells were CD27- (Fig. 3B). The proportion of CD27+ IFNγ+ γδ T cells was significantly higher, while the proportion of IL-17+ CD27-γδ T cells was substantially lower in TCRβ−/− and TCRα−/− mice (Fig. 3B). Therefore, surface phenotypes of IFNγ- and IL-17-producing γδ T cells are not different in wild type and T cell-deficient mice.

γδ T cells in the absence of CD4 and CD8 T cells

While the absence of αβ TCR+ cells alters both the development and the cytokine expression of γδ T cells (Fig. 1A), the lack of either αβ T cell subset does not affect γδ T cell development (Fig. 1B). We thus examined γδ T cell cytokine profiles in MHC II−/− and β2m−/− mice. Interestingly, the level of IL-17+ pLN γδ T cells was significantly reduced in MHC II−/− mice (Fig. 4A). Because similar defect was also found in CD4−/− mice (data not shown), this finding suggests that CD4 T cell deficiency may specifically affect IL-17 expression in γδ T cells. On the contrary, MHC II deficiency did not affect IFNγ expression in γδ T cells. Instead, in β2m−/− mice γδ T cell IFNγ production was significantly elevated, while the frequency of IL-17+ γδ T cells remained unchanged (Fig. 4A). Since it was recently shown that β2m negatively controls the homeostatic proliferation of γδ T cells 18, it is possible that β2m rather than CD8 T cell deficiency may enhance IFNγ expression. Of note, the total numbers of IL-17- and IFNγ-expressing γδ T cells should mirror the frequency of those cells, since the total numbers of γδ T cells in those mice are relatively similar (Fig. 1B). The lack of T cells in TCRβ−/− mice could alter NK cell homeostasis 20, which then suggests that γδ T cells may be exposed to a relatively increased proportion of NK cells and possibly to a increased load of NK cell-derived IFNγ. Depletion of NK cells in TCRβ−/− mice did not affect IL-17-producing γδ T cells. Because IFNγ can suppress IL-17 expression 21, unchanged IL-17 expression following NK cell depletion strongly suggests a minimal contribution of NK cells in γδ T cell activity (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4. γδ T cell cytokine expression from MHCI and MHCII deficient mice.

(A) Cells from the indicated tissues of MHC II−/− and β2m−/− mice were stimulated with PMA plus ionomycin and cytokine expression was determined by intracellular cytokine staining as described above. The mean ± SD was calculated from 7–10 individually tested mice. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01. (B) Groups of TCRβ−/− mice (n=3) were injected with anti-NK1.1 or control Ab every 3 days. IL-17 production by γδ T cells were determined as described above.

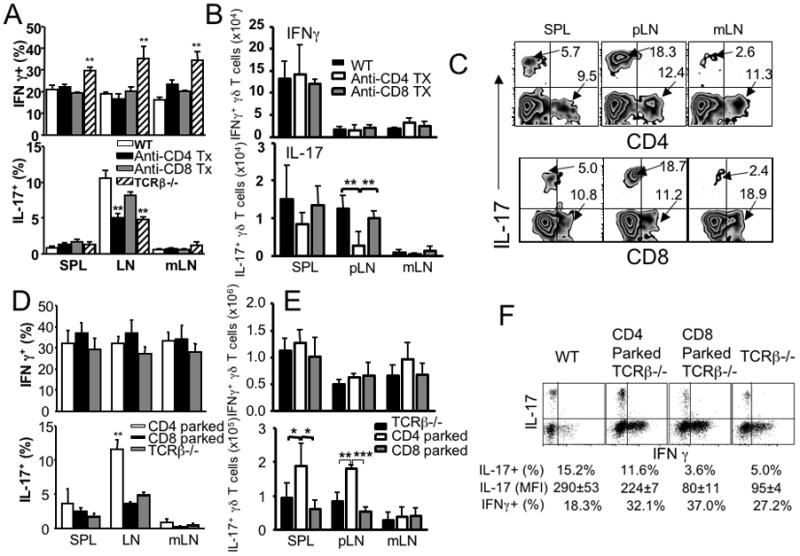

To directly examine the role of CD4 T cells in γδ T cell IL-17 expression, we depleted CD4 T cells in wild type mice and compared γδ T cell cytokine expression. CD4 T cell depletion significantly diminished IL-17 expression in γδ T cells, to a level similar to that seen in TCRβ−/− mice; however, CD4 T cell depletion did not change IFNγ expression in γδ T cells (Fig. 5A). When CD8 T cells were depleted instead, γδ T cell IL-17 expression was only slightly reduced, and no effect on the γδ T cell IFNγ expression was found (Fig. 5A), further supporting the β2m-mediated downregulation of γδ T cell activity 18. Moreover, the total numbers of IL-17+ γδ T cells within the all tested tissues of wild type mice dramatically decreased following CD4 T cell depletion (Fig. 5B). Given the fact that the number of IFNγ+ γδ T cells remained unaltered by T cell depletion, the survival of IL-17+ γδ T cell subsets might depend upon CD4 T cells. Of note, some γδ T cells express CD4 or CD8 surface markers 22. Therefore, anti-CD4 or anti-CD8 Ab treatment might deplete those cells as well. However, we found that IL-17-producing γδ T cells expressed neither CD4 nor CD8 (Fig. 5C). Therefore, anti-CD4 Ab induced reduction in IL-17+ γδ T cells cannot be attributed to depletion of those cells.

Figure 5. γδ T cell IL-17 expression altered by CD4 T cells.

(A) Groups of B6 mice received anti-CD4 or anti-CD8 Ab (250μg per injection) every 3 days. At day 21, mice were sacrificed and γδ T cell cytokine expression was determined as described above. Untreated wild type and TCRβ−/− mice were included as control groups. **, p<0.01. (B) The total numbers of IL-17+ and IFNγ+ γδ T cells were calculated in WT mice that were injected with anti-CD4 or anti-CD8 Abs as described above. **, p<0.01. (C) Representative FACS plots of IL-17, CD4, and CD8 expression of γδ T cells are shown. Experiments were repeated three times and similar results were observed. (D) Groups of TCRβ−/− mice were transferred with FACS sorted CD44low naïve CD4 or CD8 T cells (3 × 106 cells per recipient). At day 21, mice were sacrificed and γδ T cell cytokine expression was determined. The mean ± SD was calculated from 4–6 individually tested mice. **, p<0.01. (E) The total numbers of IL-17+ and IFNγ+ γδ T cells were calculated in TCRβ−/− mice that received CD4 or CD8 T cells as described above. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001. (F) γδ T cell IL-17 production increases by CD4 T cells on a per cell basis. FACS sorted CD44low naïve CD4 and CD8 T cells (3 × 106 cells per recipient) were transferred into groups of TCRβ−/− mice. At day 21, mice were sacrificed and IL-17 expression by γδ T cells was determined. Dot plots of IL-17/IFNγ expression of γδ T cells in different settings are shown. The mean fluorescent intensity (mean ± SD) of IL-17 determined by FACS analysis is shown. The percentile shown represents the proportion of IL-17+ and IFNγ+ γδ T cells. Similar data was observed from 5–9 individually tested mice in 2–3 independent experiments.

The finding that IL-17 expression in γδ T cells is CD4-dependent was further confirmed by adoptive transfer experiments. Transfer of CD4 T cells into TCRβ−/− recipients significantly increased IL-17 expression of γδ T cells, while γδ T cell IFNγ expression remained unaltered (Fig. 5D). Of note, γδ T cell IFNγ (and IL-17) expression remained unchanged after adoptive transfer of CD8 T cells (Fig. 5D). Consistently, CD4 transfer dramatically increased the total numbers of IL-17+ γδ T cells in TCRβ−/− recipients, while CD8 T cell transfer did not alter those cells (Fig. 5E). IFNγ+ γδ T cell numbers remained constant regardless of T cells transferred (Fig. 5E).

To examine the mechanism of CD4 T cell dependent γδ T cell IL-17 production, pLN γδ T cells were FACS sorted and in vitro stimulated with IL-1 plus IL-23, which was recently shown to activate IL-17 production in γδ T cells 10. WT γδ T cells (100,000 cells per well) produced ~3ng/ml of IL-17 within 12 hours following stimulation, while γδ T cells from TCRβ−/− mice produced <1ng/ml of IL-17 under the same condition (Fig. S5). It is important to point out that the frequency of IL-17+ γδ T cells in these mice are at least 3~4-fold different (Fig. 2A); i.e., 15,000~20,000 out of the total 100,000 wild type γδ T cells per well are expected to produce IL-17, while only <5000 out of the total 100,000 TCRβ−/− γδ T cells per well are expected to produce IL-17 under the same condition. In order to compare IL-17 expression on a per cell basis, we examined the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of IL-17 expression in γδ T cells. As shown in Fig. 5F, the MFI of wild type γδ IL-17 staining was significantly higher than that of TCRβ−/− γδ T cells (290 ± 53 for wild type vs. 95 ± 4 for TCRβ−/−). γδ T cells from TCRβ−/− mice that received CD4 T cells showed a significant increase of the IL-17 MFI (224 ± 7 after CD4 transfer), while CD8 T cell transfer into TCRβ−/− mice failed to exert such an enhancing effect (Figs. 5D, 5E, and 5F). Therefore, these results strongly support that CD4 T cells augment IL-17 production by γδ T cells on a per cell basis.

TGFβ1 is required for CD4 T cell-mediated γδ T cell IL-17 expression

Because we recently reported that TGFβ1 plays an irreplaceable role in inducing IL-17 expression in γδ T cells 3, we tested whether TGFβ1 is also involved in CD4-mediated γδ T cell IL-17 production. CD4 T cells were adoptively transferred into TCRβ−/− recipients and neutralizing anti-TGFβ1 or control rat Ab was injected into the recipients. TCRβ−/− recipients of CD4 T cells injected with control rat IgG had significantly increased IL-17 expression in pLN γδ T cells (Fig. 6A). However, anti-TGFβ1 Ab completely abrogated the effect (Fig. 6A). Anti-TGFβ1 Ab treatment slightly increased IFNγ production by pLN γδ T cells; however, the increase was relatively small (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, the increase in the total numbers of IL-17+ γδ T cells by CD4 T cell transfer was abolished by TGFβ1 neutralization (Fig. 6B). Therefore, CD4 T cell-mediated increase in γδ T cell IL-17 production is TGFβ1-dependent. CD25+ Treg cells are known to exert regulatory functions by producing TGFβ1 23. Therefore, we tested if Tregs might be the source of TGFβ1 to control γδ T cell IL-17 expression. To test this possibility, CD25- naïve CD4 T cells were transferred into TCRβ−/− mice. As shown in Fig. S6, non-Treg CD4 T cells were capable of enhancing γδ T cell IL-17 expression, suggesting that TGFβ1 required for the effect is not necessarily derived from Tregs.

Figure 6. CD4-mediated increase in γδ T cell IL-17 expression is TGFβ1-dependent.

Groups of TCRβ−/− mice were transferred with FACS sorted naïve CD4 T cells (3 × 106 cells per recipient). The mice were i.p. injected with 500μg anti-TGFβ1 or rat IgG every 3 days. The mice were sacrificed 3 weeks post T cell transfer, and indicated lymphoid tissue cells were stimulated as described above. The proportion (A) and the total numbers (B) of IL-17+ and IFNγ+ γδ T cells were calculated as described above. The mean ± SD was calculated from 3 individually tested mice. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001.

Th17 phenotype effector CD4 T cells are highly efficient in enhancing IL-17 expression of γδ T cells

To further examine if CD4-mediated increase in γδ T cell IL-17 expression is regulated by cytokines produced by activated T cells, we generated Th1, Th2, and Th17 effector CD4 T cells in vitro, and adoptively transferred into TCRβ−/− recipients. Prior to transfer, CD4 T cell cytokine profiles were determined to ensure differentiation status (Fig. 7A). γδ T cell cytokine expression was subsequently examined. As shown in Fig. 7B, IL-17 expression in γδ T cells was significantly elevated only after Th17 CD4 T cell transfer. Both Th1 and Th2 effector CD4 T cells were unable to do so. On the other hand, IFNγ expression in γδ T cells was not affected by CD4 T cells regardless of their differentiation phenotypes, consistent with the earlier findings (Fig. 5). Since naïve CD4 T cells transferred into lymphopenic mice are expected to differentiated into IL-17-producing Th17 type cells, which may contribute to the development of intestinal inflammation, our results strongly suggest that Th17 effector cells generated during in vivo proliferation may enhance γδ T cell IL-17 expression.

Figure 7. Th17 CD4 T cell mediated increase in γδ T cell IL-17 expression.

CD4 T cells were in vitro stimulated with soluble anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28 Ab as described in Materials and Methods. Th1, Th2, and Th17 phenotype effector CD4 T cells were generated. (A) Prior to transfer, differentiation status of the resulting effector cells was examined by measuring IFNγ, IL-4, and IL-17 expression. (B) 3 × 106 CD4 T cells were adoptively transferred into TCRβ−/− recipients, and γδ T cell cytokine expression was determined 2 weeks post transfer. FACS dot plots shown are representative of cytokine expression of γδ T cells from three individually tested recipients.

Discussion

Unlike αβ T cells, the majority of γδ T cells from naïve animals display phenotypes of effector/memory cells and are capable of producing effector cytokines such as IFNγ and IL-17 upon stimulation 24. However, a mechanism underlying the generation and maintenance of the cytokine-producing γδ T cells in vivo remains obscure. Our data unveils a novel regulatory mechanism in which CD4 T cells maintain IL-17-producing γδ T cell subsets via a TGFβ1-dependent manner in vivo. The fact that depleting CD4 (but not CD8) T cells in wild type mice dramatically reduced the proportion as well as the total numbers of IL-17+ γδ T cells in the periphery strongly suggests that the CD4-mediated control is an active process during which γδ T cell survival may improve. In support of this notion, CD4 T cells transferred into TCRβ−/− mice dramatically increased the IL-17-producing γδ T cell subsets. It is important to point out that CD4 T cell proliferation that occurs within TCRβ−/− mice as a homeostatic mechanism is not a requirement for the CD4-mediated effect because: 1) a similar effect is also seen in wild type mice and 2) CD8 T cell transferred into TCRβ−/− mice fail to do so despite their proliferation. Interestingly, the proportion (and the kinetics of development) of IL-17+ γδ T cells within the thymus of TCRβ−/− mice was similar to that seen in the thymus of wild type mice. Thus, CD4-dependent maintenance of IL-17+ γδ T cells may operate primarily in the periphery and that the thymic differentiation and peripheral maintenance of IL-17+ γδ T cells may be regulated by a separate mechanism that has yet to be identified. CD4 T cell-mediated effects in IL-17+ γδ T cell maintenance required TGFβ1, a major cytokine produced by CD25+ Tregs 23. However, adoptive transfer of non-Tregs was highly efficient in elevating IL-17+ γδ T cells in the periphery, suggesting that Tregs are not responsible for the maintenance. Instead, we found that in vitro differentiated IL-17-producing Th17 effector CD4 T cells were highly efficient in enhancing IL-17 expression in γδ T cells compared to Th1 or Th2 phenotype effector T cells, although whether IL-17 produced by these cells directly mediates the effect remains to be determined. Whether Th17 CD4 T cells are the source of TGFβ1, or whether Th17 CD4 T cells induce TGFβ1 from other sources needs to be identified. Alternatively, TGFβ1 may act on CD4 T cells, which then may promote Th17 differentiation and enhance IL-17 production in γδ T cells. Importantly, the ‘basal’ level IL-17+ γδ T cells found in TCRβ−/− mice was not affected by TGFβ1 neutralization. TGFβ2/β3, unknown factors, or both may be involved in this process.

Unexpectedly, IFNγ expression in γδ T cells was significantly elevated in TCRβ−/− mice. It was previously shown that the absence of αβ T cell progenitors (DP thymocytes) in TCRβ−/− mice impairs γδ T cell development and functions via a LTβ-dependent ‘trans-conditioning’ mechanism 13. On the contrary, we reproducibly observed that γδ T cell IFNγ expression was equivalent or higher in T cell-deficient (TCRβ−/− or TCRα−/−) mice. In fact, we compared IFNγ intracellular expression between wild type and TCRβ−/− γδ T cells in more than ten independent experiments and obtained the similar results. Moreover, no difference in IFNγ expression as well as in the total numbers of IFNγ-/IL-17-producing γδ T cells was noticed between γδ T cells from TCRβ−/− and TCRα−/− mice. A mechanism underlying the discrepancy is unclear. It was previously shown that γδ T cells isolated from TCRβ−/− and wild type mice displayed identical cytokine production pattern under Th1 and Th2 polarization conditions 25. T-bet expression in γδ T cells (isolated from TCRβ−/− mice) was shown to enhance IFNγ production, which was not counterbalanced by GATA-3 expression, suggesting the default synthesis of IFNγ by γδ T cells 26. More rigorous study to identify cellular and molecular mechanism underlying αβ T cell-dependent γδ T cell activation, if any, will be needed to account for this discrepancy.

From the standpoint of T cell homeostasis, it is interesting to see that the total numbers of developing (and peripheral) γδ T cells are substantially elevated in the absence of αβ T cells, which suggests that the observed altered frequency of IFNγ- and IL-17-producing γδ T cells may reflect a unique requirements for homeostatic expansion of these T cell subsets. Since the lack of either CD4 or CD8 T cell subset did not alter γδ T cell homeostasis, either T cell subset is fully capable of controlling over-expansion of γδ T cells, possibly via cytokines 15. Nevertheless, a regulatory mechanism between IL-17-producing γδ and CD4 T cells identified from the current study is still in place. Whether such requirements for γδ T cell expansion differ based on the cytokine profiles will require further examination.

The lack of T cells in TCRβ−/− mice could alter NK cell activity, which then might influence γδ T cell cytokine production. However, it was previously shown that NK cell activity is not controlled by T cells including regulatory Treg cells 20. Consistent with this, depletion of NK cells using anti-NK1.1 Ab did not alter IL-17 production by γδ T cells. We are aware that some IFNγ+ γδ T cells express NK1.1 2. However, it should be noted that the proportion of those cells was only ~5% 2, suggesting a minimal contribution. Alternatively, γδ T cells in TCRβ−/− mice may be exposed to increased level of APC interactions (primarily due to lack of T cells), which may result in an altered state of differentiation status of γδ T cells.

αβ and γδ T cells have been found to counter-regulate each other in many ways. γδ T cells can downregulate αβ T cell activity because αβ T cells isolated from mice injected with anti-γδ TCR (GL3) Ab undergo robust proliferation as well as produce elevated effector cytokines upon in vitro stimulation 27. γδ T cells were also shown to amplify the generation of IL-17+ CD4 T cells in autoimmune settings 10. Foxp3+ CD4 Treg cells were recently shown to suppress proliferation and cytokine production of γδ T cells 28. Consistent with the results reported here, Cui et al. recently reported that the presence of αβ T cells dramatically increases IL-17 production of γδ T cells in vitro and that this effect is mediated by cell-to-cell contact 11. In human, CD27- Vγ9Vδ2 T cells were shown to be absent in immunocompromised hosts 29. It will be important to test how such counter-regulation influences immune responses.

Collectively, our results reveal an important regulatory mechanism that balances γδ T cell subset homeostasis by CD4 T cells; αβ (specifically CD4) T cells not only maintain the size of peripheral γδ T cells but also optimize the development of IL-17+ γδ T cell subsets. γδ T cell-derived IL-17 plays critical roles in clearing certain microbes through neutrophil mobilization 9, 30, 31. Therefore, understanding in vivo cross-regulation between these two T cell subsets will be of great importance to define a homeostatic mechanism that equips proper ‘innate’ effector cells such as IL-17+ γδ T cells prior to antigenic challenge.

Materials and Methods

Animals

C57BL/6, TCRβ−/−, TCRα−/−, MHC II−/−, β2m−/−, and Rag1−/− mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). All experimental procedures were conducted according to the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Cleveland Clinic Foundation.

Ex vivo stimulation

Spleen, pLN (axillary and cervical LN) and mesenteric LN (mLN) cells were separately harvested and ex vivo stimulated with PMA (10ng/ml) and Ionomycin (1 μM) for 4 hrs in the presence of 2 μM monensin (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) during the last 2 hrs. Cells were immediately fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized, and stained with fluorescence conjugated antibodies. In some experiment, IL-17 production by γδ T cells was examined by ELISA. Both coating and detection anti-IL-17A mAbs were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA).

Flow cytometry

The following antibodies were used: biotinylated anti-γδ TCR (GL3), PE-anti-γδ TCR (GL3), PE-anti-IFNγ (XMG1.2), PE-anti-IL-17 (ebio17B7), PE-anti-CD27 (LG.7F9), APC-anti-IL-17 (ebio17B7), APC-anti-CCR6 (R35–95), FITC-anti-Human Ki-67, and FITC-anti-IFNγ (XMG1.2) Abs. All antibodies were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA) or PharMingen (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA). FITC-anti-Vγ1 (clone 2.11, ref 32), FITC-anti-Vγ4 (clone UC3, ref 33), biotinylated-anti-Vγ5 (clone 536, ref 34), and FITC-anti-Vg7 (clone UC1, ref 35) Abs were prepared by the O’Brien laboratory using standard method as previously described 11, 36. In some experiments, γδ T cells from the lymphoid tissues were sorted using a FACSAria cell sorter (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Sorted γδ T cells were labeled with carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE, Molecular Probe, Carlsbad, CA) and subsequently i.v. transferred into Rag1−/− recipients. Recipients were sacrificed 7 days post transfer, and CFSE profiles of the γδ T cells were examined. In some experiments, naïve CD4 or CD8 T cells were FACS sorted and i.v. transferred into TCRβ−/− recipients (3 × 106 cells per recipient). γδ T cell cytokine expression was determined 2 weeks post transfer. Cells were acquired using a FACSCalibur or LSRII cytometer (Becton Dickinson), and the data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Treestar, Ashland, OR).

T cell differentiation in vitro

Naïve CD4 T cells were cocultured with T-depleted splenocytes in the presence of soluble anti-CD3 (1μg/ml) and anti-CD28 (1μg/ml) Abs. For Th1 differentiation, IL-12 (10ng/ml) and anti-IL-4 Ab (10μg/ml) were added. For Th2 differentiation, IL-4 (1000U/ml), anti-IFNγ Ab (10μg/ml), and anti-IL-12 Ab (10μg/ml) were added. For Th17 differentiation, TGFβ1 (5ng/ml), IL-6 (10ng/ml), anti-IFNγ Ab (10μg/ml), and anti-IL-4 Ab (10μg/ml) were added. CD4 T cells were reisolated from the culture and adoptively transferred into TCRβ−/− recipients (3 × 106 cells per recipient). γδ T cell cytokine production was determined 2 weeks post transfer.

qRT-PCR

γδ T cells were FACS sorted from wild type or TCRβ−/− mice. Total RNA was extracted using an RNeasy column (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). cDNA was subsequently obtained using a SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Real time PCR was performed using the ifng- and il17a-specific primers and probe sets (Applied Biosystem, Foster City, CA) and ABI 7500 PCR machine (Applied Biosystem).

Data analysis

Statistical significance was determined by the Student’s t-test using the Prism 4 software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA). p<0.05 was considered to indicate a significant difference.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ms. Jennifer Powers for cell sorting, Drs. Stephen Stohlman and Rob Fairchild for providing anti-TGFβ1 and anti-CD4/anti-CD8 Abs, respectively. This study was supported by NIH grants AI074932 (to B.M.).

Footnotes

Supplementary information is available at Immunology and Cell Biology’s website (http://www.nature.com/icb).

References

- 1.Shibata K, Yamada H, Nakamura R, Sun X, Itsumi M, Yoshikai Y. Identification of CD25+ gamma delta T cells as fetal thymus-derived naturally occurring IL-17 producers. J Immunol. 2008;181(9):5940–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.5940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haas JD, Gonzalez FH, Schmitz S, Chennupati V, Fohse L, Kremmer E, et al. CCR6 and NK1.1 distinguish between IL-17A and IFN-gamma-producing gammadelta effector T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39(12):3488–97. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Do JS, Fink PJ, Li L, Spolski R, Robinson J, Leonard WJ, et al. Cutting Edge: Spontaneous Development of IL-17-Producing {gamma}{delta} T Cells in the Thymus Occurs via a TGF-{beta}1-Dependent Mechanism. J Immunol. 184(4):1675–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kisielow J, Kopf M, Karjalainen K. SCART scavenger receptors identify a novel subset of adult gammadelta T cells. J Immunol. 2008;181(3):1710–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.3.1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhu J, Yamane H, Paul WE. Differentiation of effector CD4 T cell populations (*) Annu Rev Immunol. 28:445–89. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Do JS, Fink PJ, Li L, Spolski R, Robinson J, Leonard WJ, et al. Cutting edge: spontaneous development of IL-17-producing gamma delta T cells in the thymus occurs via a TGF-beta 1-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 184(4):1675–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Brien RL, Roark CL, Born WK. IL-17-producing gammadelta T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39(3):662–6. doi: 10.1002/eji.200839120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andrew EM, Newton DJ, Dalton JE, Egan CE, Goodwin SJ, Tramonti D, et al. Delineation of the function of a major gamma delta T cell subset during infection. J Immunol. 2005;175(3):1741–50. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shibata K, Yamada H, Hara H, Kishihara K, Yoshikai Y. Resident Vdelta1+ gammadelta T cells control early infiltration of neutrophils after Escherichia coli infection via IL-17 production. J Immunol. 2007;178(7):4466–72. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sutton CE, Lalor SJ, Sweeney CM, Brereton CF, Lavelle EC, Mills KH. Interleukin-1 and IL-23 induce innate IL-17 production from gammadelta T cells, amplifying Th17 responses and autoimmunity. Immunity. 2009;31(2):331–41. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cui Y, Shao H, Lan C, Nian H, O’Brien RL, Born WK, et al. Major role of gamma delta T cells in the generation of IL-17+ uveitogenic T cells. J Immunol. 2009;183(1):560–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silva-Santos B, Pennington DJ, Hayday AC. Lymphotoxin-mediated regulation of gammadelta cell differentiation by alphabeta T cell progenitors. Science. 2005;307(5711):925–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1103978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pennington DJ, Silva-Santos B, Shires J, Theodoridis E, Pollitt C, Wise EL, et al. The inter-relatedness and interdependence of mouse T cell receptor gammadelta+ and alphabeta+ cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4(10):991–8. doi: 10.1038/ni979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corthay A, Johansson A, Vestberg M, Holmdahl R. Collagen-induced arthritis development requires alpha beta T cells but not gamma delta T cells: studies with T cell-deficient (TCR mutant) mice. Int Immunol. 1999;11(7):1065–73. doi: 10.1093/intimm/11.7.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.French JD, Roark CL, Born WK, O’Brien RL. {gamma}{delta} T cell homeostasis is established in competition with {alpha}{beta} T cells and NK cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(41):14741–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507520102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ribot JC, deBarros A, Pang DJ, Neves JF, Peperzak V, Roberts SJ, et al. CD27 is a thymic determinant of the balance between interferon-gamma- and interleukin 17-producing gammadelta T cell subsets. Nat Immunol. 2009;10(4):427–36. doi: 10.1038/ni.1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baccala R, Witherden D, Gonzalez-Quintial R, Dummer W, Surh CD, Havran WL, et al. Gamma delta T cell homeostasis is controlled by IL-7 and IL-15 together with subset-specific factors. J Immunol. 2005;174(8):4606–12. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.4606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.French JD, Roark CL, Born WK, O’Brien RL. Gammadelta T lymphocyte homeostasis is negatively regulated by beta2-microglobulin. J Immunol. 2009;182(4):1892–900. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mombaerts P, Clarke AR, Rudnicki MA, Iacomini J, Itohara S, Lafaille JJ, et al. Mutations in T-cell antigen receptor genes alpha and beta block thymocyte development at different stages. Nature. 1992;360(6401):225–31. doi: 10.1038/360225a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joncker NT, Raulet DH. Regulation of NK cell responsiveness to achieve self-tolerance and maximal responses to diseased target cells. Immunol Rev. 2008;224:85–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00658.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jain R, Tartar DM, Gregg RK, Divekar RD, Bell JJ, Lee HH, et al. Innocuous IFNgamma induced by adjuvant-free antigen restores normoglycemia in NOD mice through inhibition of IL-17 production. J Exp Med. 2008;205(1):207–18. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Felices M, Yin CC, Kosaka Y, Kang J, Berg LJ. Tec kinase Itk in gammadeltaT cells is pivotal for controlling IgE production in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(20):8308–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808459106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bommireddy R, Doetschman T. TGFbeta1 and Treg cells: alliance for tolerance. Trends Mol Med. 2007;13(11):492–501. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bonneville M, O’Brien RL, Born WK. Gammadelta T cell effector functions: a blend of innate programming and acquired plasticity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10 (7):467–78. doi: 10.1038/nri2781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yin Z, Zhang DH, Welte T, Bahtiyar G, Jung S, Liu L, et al. Dominance of IL-12 over IL-4 in gamma delta T cell differentiation leads to default production of IFN-gamma: failure to down-regulate IL-12 receptor beta 2-chain expression. J Immunol. 2000;164(6):3056–64. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.6.3056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yin Z, Chen C, Szabo SJ, Glimcher LH, Ray A, Craft J. T-Bet expression and failure of GATA-3 cross-regulation lead to default production of IFN-gamma by gammadelta T cells. J Immunol. 2002;168(4):1566–71. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.4.1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaufmann SH, Blum C, Yamamoto S. Crosstalk between alpha/beta T cells and gamma/delta T cells in vivo: activation of alpha/beta T-cell responses after gamma/delta T-cell modulation with the monoclonal antibody GL3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90(20):9620–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goncalves-Sousa N, Ribot JC, deBarros A, Correia DV, Caramalho I, Silva-Santos B. Inhibition of murine gammadelta lymphocyte expansion and effector function by regulatory alphabeta T cells is cell-contact-dependent and sensitive to GITR modulation. Eur J Immunol. 40(1):61–70. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gioia C, Agrati C, Casetti R, Cairo C, Borsellino G, Battistini L, et al. Lack of CD27-CD45RA-V gamma 9V delta 2+ T cell effectors in immunocompromised hosts and during active pulmonary tuberculosis. J Immunol. 2002;168(3):1484–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.3.1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schulz SM, Kohler G, Holscher C, Iwakura Y, Alber G. IL-17A is produced by Th17, gammadelta T cells and other CD4- lymphocytes during infection with Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis and has a mild effect in bacterial clearance. Int Immunol. 2008;20(9):1129–38. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxn069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Umemura M, Yahagi A, Hamada S, Begum MD, Watanabe H, Kawakami K, et al. IL-17-mediated regulation of innate and acquired immune response against pulmonary Mycobacterium bovis bacille Calmette-Guerin infection. J Immunol. 2007;178(6):3786–96. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.6.3786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pereira P, Gerber D, Huang SY, Tonegawa S. Ontogenic development and tissue distribution of V gamma 1-expressing gamma/delta T lymphocytes in normal mice. J Exp Med. 1995;182(6):1921–30. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.6.1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dent AL, Matis LA, Hooshmand F, Widacki SM, Bluestone JA, Hedrick SM. Self-reactive gamma delta T cells are eliminated in the thymus. Nature. 1990;343(6260):714–9. doi: 10.1038/343714a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Havran WL, Grell S, Duwe G, Kimura J, Wilson A, Kruisbeek AM, et al. Limited diversity of T-cell receptor gamma-chain expression of murine Thy-1+ dendritic epidermal cells revealed by V gamma 3-specific monoclonal antibody. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86(11):4185–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.11.4185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goodman T, LeCorre R, Lefrancois L. A T-cell receptor gamma delta-specific monoclonal antibody detects a V gamma 5 region polymorphism. Immunogenetics. 1992;35(1):65–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00216631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pereira P, Lafaille JJ, Gerber D, Tonegawa S. The T cell receptor repertoire of intestinal intraepithelial gammadelta T lymphocytes is influenced by genes linked to the major histocompatibility complex and to the T cell receptor loci. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(11):5761–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.11.5761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.