Abstract

The recent demonstration that the carbene cluster [Fe4S4(Pri2NHCMe2)4] (9) is an accurate structural and electronic analogue of the fully reduced cluster of the iron protein of A. vinelandii nitrogenase, including a common S = 4 ground state, raises the issue of the existence and magnetism of other [M4S4L4]z clusters, none of which are known with transition metals other than iron. The system CoCl2/Pri3P/(Me3Si)2S/THF assembles [Co4S4(PPri3)4] (3) which is converted to [Co4S4(Pri2NHCMe2)4] (5) upon reaction with carbene. The clusters support the redox series [3]1−/0/1+ and [5]0/1+/2+; monocations (4, 6) have been isolated by chemical oxidation. Redox potentials and substitution reactions indicate that the carbene is the more effective electron donor to tetrahedral FeII and CoII sites. Clusters 3–6 have the same overall cubane-type geometry as 9. Neutral clusters 3 and 5 have an S = 3 ground state. As with the S = 4 state of 9 with local spins SFe = 2, the septet spin state can be described in terms of the coupling of three parallel and one antiparallel spins SCo = 3/2. The octanuclear clusters [Co8S8(PPri3)6]0,1+ were isolated as minor byproducts of the formation and chemical oxidation of 3. The clusters exhibit a rhomb-bridged noncubane (RBNC) structure, whereas clusters with the Fe8S8 core possess the edge-bridged double-cubane (EBDC) stereochemistry. There are two structural solutions for the M8S8 core in the form of topological isomers whose stability may depend on valence electron count. A conceptual model for the RBNC ← EBDC interconversion is presented. (Pri2NHCMe2 = C11H20N2 = 1,3-diisopropyl-4,5-dimethylimidazol-2-ylidene)

Introduction

The cubane-type core unit Fe4(μ3-S)4 is prominently represented within the vast array of structures of iron-sulfur clusters with weak field1–3 and strong field4 terminal ligands. Our interest in weak field clusters derives from their well-known role as accurate structural and electronic analogues of protein-bound clusters {Fe4S4(SCys)3L] in which ligand L is cysteinate, another amino acid side chain, or hydroxide/water.2 In such clusters the core oxidation states [Fe4S4]3+,2+,1+ are common and all have been isolated in synthetic clusters.2 The demonstration of the all-ferrous oxidation state [Fe4S4]0 in the iron protein of A. vinelandii (Av) nitrogenase,5–8, and more recently in a dehydratase activator protein from A. fermentans,9 upon reduction of the proteins with Ti(III) citrate provided an imperative for the synthesis and full characterization of heretofore unknown synthetic analogues of this state. The first all-ferrous clusters produced were the phosphine species [Fe4S4(PR3)4] (R = Pri, But, C6H11), but all attempts to isolate these compounds in substance resulted in core aggregation accompanying phosphine dissociation to afford the dicubanes [Fe8S8(PR3)6] and tetracubanes [Fe16S16(PR3)8].10,11 More recently, fully reduced clusters have been isolated in the form of [Fe4S4(CN)4]4− 12 and [Fe4S4(Pri2NHCMe2)4] with the N-heterocyclic carbene ligand 1,3-diisopropyl-4,5-dimethylimidazol-2-ylidene.13 The more stable carbene cluster has been shown to be a meaningful representation of the all-ferrous cluster in proteins.13,14 In particular, a detailed analysis of its Mössbauer and EPR spectra has established an St = 4 ground state,15 which amongst all biological clusters has been found only in those of the Av iron protein7 and the activator protein.9

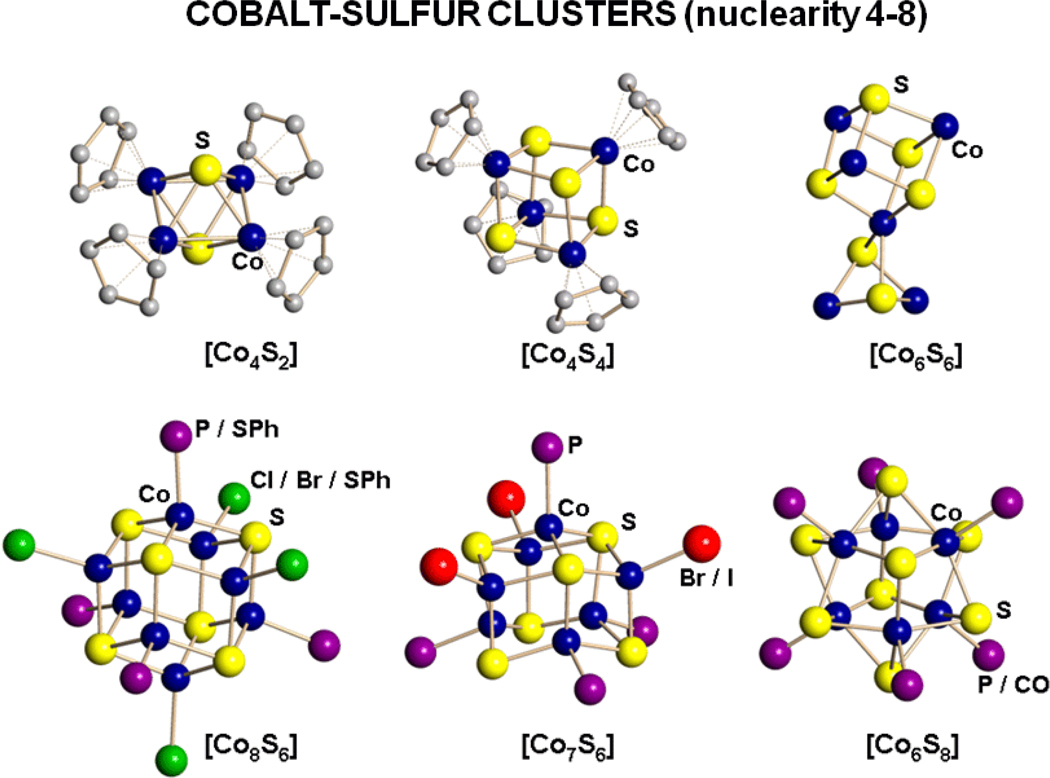

The foregoing results support the proposition that the exchange coupling leading to the observed ground state is intrinsic to the [Fe4S4]0 core and is not significantly influenced by the terminal ligands. An associated issue is the ground spin states in other fully reduced cubane-type [M4S4]0 clusters with variable M. The corresponding core units are unknown with other metals that manifest a tetrahedral stereochemical preference, necessitating synthesis of a new family of clusters. Cobalt(II) commonly exhibits this preference. However, we note that in the brief structural survey of Co-S clusters in Figure 1, which includes nuclearities n = 4,16,17 6,18–22 7,23,24 and 8,25 tetrahedral coordination is found only with n = 7 and 8, the large majority of the clusters are mixed-valence, and cubane stereochemistry is limited to a single example with CoIII ([Cp4Co4S4]17). If Co-Se clusters are considered, different examples emerge which include the cubane [Co4Se4(PPh3)4]26 and [Co8Se8(PPh3)6]0,1+,27 with a composition analogous to [Fe8S8(PR3)6]. In this investigation, we have prepared and structurally characterized the cubane-type clusters [Co4S4(Pri2NHCMe2)4] and [Co4S4(PPri3)4], examined their redox chemistry, and determined magnetic ground states. As will be seen, these clusters exhibit an exchange coupling pattern and a highly paramagnetic ground state consonant with the properties of [Fe4S4]0 clusters.

Figure 1.

Structures of Co-S clusters with nuclearities of four to eight showing the exclusive or usual terminal ligand atoms associated with each. The five η5-C5Me5 ligands of Co6S6 are omitted for clarity.

Experimental Section

Preparation of Compounds

All reactions and manipulations were performed under a pure dinitrogen atmosphere using either Schlenk techniques or an inert atmosphere box. Solvents were passed through an Innovative Technology or MBraun solvent purification system prior to use. Solvent removal steps were performed in vacuo. Selected compounds were analyzed (H.Kolbe, Mulheim, Germany). All compounds except [Co(PriNHCMe2)2Cl2] were identified by X-ray structural determinations.

[Co(Pri2NHCMe2)2(SBut)2]

To a suspension of CoCl2 (0.13 g, 1.0 mmol) in THF (10 mL) was added a solution of Pri2NHCMe2 (1,3-diisopropyl-4,5-dimethylimidazol-2-ylidene,28 0.36 g, 2.0 mmol) in THF (5 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred for 4 h. Addition of a solution of ButSNa (0.22 g, 2.0 mmol) in THF (10 mL) resulted in formation of a green suspension. The mixture was stirred for 2 d and filtered. Vapor diffusion of n-hexane into the filtrate afforded the product as a green crystalline solid (0.43 g, 72%). Absorption spectrum (benzene): λmax (εM) 344 (6820), 406 (2490), 456 (1460), 564 (353), 652 (1280), 717 (1144) nm. 1H NMR (C6D6): δ 18.87 (12), 6.80 (9); (THF-d8): δ 18.04 (12), 7.54 (9).

[Co(Pri2NHCMe2)2Cl2]

To a suspension of CoCl2 (0.13 g, 1.0 mmol) in benzene (30 mL) was added a solution of Pri2NHCMe2 (0.36 g, 2.0 mmol) in THF (3 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred for 2 d. The blue suspension was filtered and the solid was washed with ether (2 × 5 mL) and dried in vacuo. The product was obtained as a blue powder (0.44 g, 90%). Absorption spectrum (benzene): λmax (εM) 312 (828), 597 (440), 640 (920) nm. 1H NMR (C6D6): δ 14.63 (1), 8.78 (2).

[Co4S4(PPri3)4]

Method A of the preparation of [Co4S4(Pri2NHCMe2)4] (see below) was followed to the point of the brown oily residue, which was dissolved in THF (5 mL) and the solution was filtered. Layering acetonitrile (20 mL) on the filtrate caused separation of the product as black crystalline blocks (0.34 g, 70%). 1H NMR (C6D6): δ 14.71 (1), 1.80 (6). Anal. Calcd. C, 43.03; H, 8.43; Co, 23.46; P, 12.33; S, 12.76. Found: C, 42.94; H, 8.39; Co, 23.49; P, 12.38; S, 12.77. A very small quantity of platelike black crystals was separated from the bulk product and shown to be [Co8S8(PPri3)6] by an X-ray structure determination.

[Co4S4(PPri3)4](BF4)

To a solution of [Co4S4(PPri3)4] (0.19 g, 0.20 mmol) in THF (5 mL) was added [Cp2Fe](BF4) (0.055 g, 0.20 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred overnight. Solvent was removed, the deep brown residue was dissolved in acetonitrile (2 mL), and the solution was filtered. Vapor diffusion of ether into the brown filtrate afforded the product as deep brown block-like crystals (0.15 g, 70%). Absorption spectrum (THF): λmax (εM) 370 (sh, 13900) nm. 1H NMR (CD3CN): δ 2.65 (6), 2.32 (1). Anal. Calcd. for C36H84BCo4F4P4S4: C, 39.60; H, 7.76; Co, 21.59; P, 11.35; S, 11.75. Found: C, 39.41; H, 7.49; Co, 22.19; P, 11.44. An accurate sulfur analysis was not obtained. A small amount of brown platelike crystals was also obtained from the bulk sample and shown by an X-ray structure determination to [Co8S8(PPri3)6](BF4).

[Co4S4(Pri2NHCMe2)4]

Method A

To a suspension of CoCl2 (0.26 g, 2.0 mmol) and PPri3 (0.64 g, 4.00 mmol)29 in THF (10 mL) was added a solution of (Me3Si)2S (0.43 g, 2.4 mmol) in THF (10 mL). The mixture was stirred for 2 d, solvent was removed, and deep brown oily residue was dissolved in THF (10 mL). The solution was filtered. The filtrate was treated with a solution of Pri2NHCMe2 (0.72 g, 4.0 mmol) in THF (10 mL), resulting in a brown suspension, which was stirred for 7 d. The reaction mixture was filtered. Vapor diffusion of n–hexane into the brown filtrate afforded the product as a brown crystalline solid (0.28 g, 50%). 1H NMR (C6D6): δ 7.37 (1), 5.38 (2), −11.6 (br). Anal. Calcd. for C44H80Co4N8S4: C, 48.70; H, 7.43; Co, 21.71; N, 10.33; S, 11.82. Found: C, 47.61; H, 7.29; Co, 21.23; N, 10.07; S, 11.53.

Method B

A solution of [Co4S4(PPri3)4] (0.20 g, 0.20 mmol) in THF (5 mL) was treated with a solution of Pri2NHCMe2 (0.16 g, 0.90 mmol) in THF (5 mL). The reaction mixture was refluxed overnight and filtered. Solvent was removed from the filtrate, the deep brown oily residue was dissolved in benzene (5 mL), and the solution was filtered. Vapor diffusion of hexanes into the brown filtrate yielded the product as deep brown crystals (0.17 g, 80%). The 1H NMR spectrum of this material was identical with that of the product from Method A.

[Co4S4(Pri2NHCMe2)4](PF6)

To a solution of [Co4S4(Pri2NHCMe2)4] (0.11 g, 0.10 mmol) in THF (5 mL) was added (C7H7)(PF6) (0.024 g, 0.10 mmol). The mixture was stirred overnight. Solvent was removed, the deep brown residue was dissolved in THF (2 mL), and the solution was filtered. Vapor diffusion of n-hexane into the brown filtrate yielded the product as brown crystals (0.055 g, 40%). 1H NMR (CD3CN): δ 11.75 (1), 9.53 (2).

[Co4S4(Pri2NHCMe2)4](BPh4)

This compound was prepared on the same scale by the previous procedure but with use of NaBPh4 (0.034 g, 0.10 mmol) in 5 mL of acetonitrile. It was obtained as brown crystals (0.097 g, 70%) with an identical 1H NMR spectrum of the cation. Absorption spectrum (THF): λmax (εM) 374 (sh, 14100) nm.

In the sections that follow, compounds are referred to by the designations in the Chart.

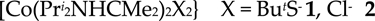

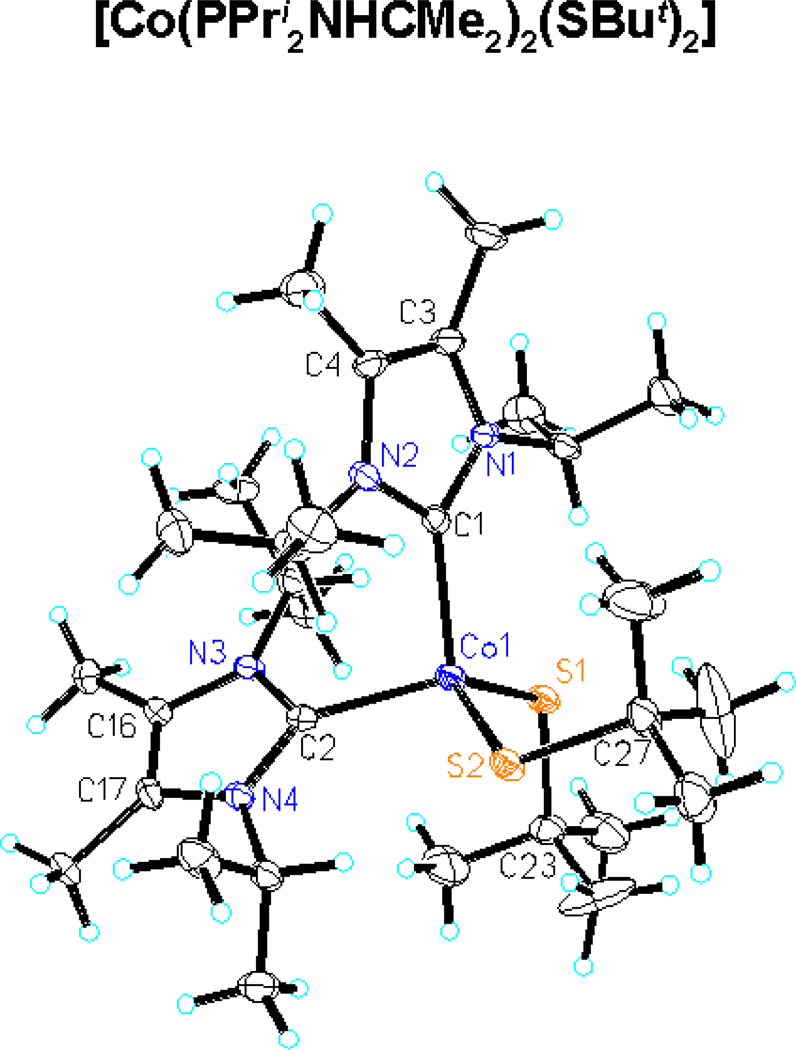

Chart.

Designation of Compounds

X-ray Structure Determinations

The structures of the seven compounds in supplemental Table S-1 were determined. Diffraction-quality crystals were obtained as follows: 3 and 7, THF/acetonitrile; 5, benzene/hexane; [4](BF4) and [8](BF4), acetonitrile/ether; 1, [6](BPh4), THF/hexane. Crystallizations were performed at room temperature. Crystals were coated with Paratone-N oil and mounted on a Bruker APEX CCD-based diffractometer equipped with an Oxford low-temperature apparatus. Data were collected with scans of 0.3 s/frame for 30 s. Cell parameters were retrieved with SMART software and refined using SAINT software on all reflections. Data integration was performed with SAINT, which corrects for Lorentz polarization and decay. Absorption corrections were applied using SADABS. Space groups were assigned unambiguously by analysis of symmetry and systematic absences determined by XPREP. All structures were solved and refined using SHELXTL. Metal and first coordination sphere atoms were located from direct-methods E-maps; other non-hydrogen atoms were found in alternating difference Fourier synthesis and least-squares refinement cycles and during final cycles were refined anisotropically. Hydrogen atoms were placed in calculated positions employing a riding model. Final crystal parameters and agreement factors are reported in Table S-1.30 Three of the four PPri3 ligands of 3 are each disordered over two positions with equal occupancies such that the two Co-P vectors are each site form angles of 19.1(1)°, 23.8(1)°, and 24.4(1)°.

Other Physical Measurements

All measurements were performed under anaerobic conditions. Absorption spectra were recorded with a Varian Cary 50 Bio spectrophotometer. 1H NMR spectra were obtained with a Varian AM-400 spectrometer. Cyclic voltammetry measurements were made with a BioAnalytical Systems Epsilon potentiostat/galvanostat in THF solutions using a sweep rate of 100 mV/s, a glassy carbon working electrode, 0.1 M (Bu4N)(PF6) supporting electrolyte, and an SCE reference electrode. Under these conditions, E½ = 0.55 V for the [Cp2Fe]0,1+ couple.

Magnetic susceptibility data were obtained with powder samples at 2–300 K using a SQUID susceptometer with a field of 1.0 T (MPMS-7, Quantum Design, calibrated with a palladium reference sample, error <2%). Multiple-field variable-temperature measurements were done at 1 T, 4 T, and 7 T also at 2–300 K with the magnetization sampled in equidistant steps on a 1/T temperature scale. The data were corrected for diamagnetic contributions by using Pascal's constants,31 as well as for temperature-independent paramagnetism. The susceptibility and magnetization data for the cluster compounds were simulated using the usual spin-Hamiltonian operator 1 for a system of four high spin Co(II) sites with local spin Si = 3/2. Here Ji,j are the isotropic coupling constants for the exchange interaction between the individual cobalt ions (i = 1, 4), gi are the average electronic g-values, and Di and E/Di are the average zero-field splitting and rhombicity parameters for the ions. Alternatively, the data for the cluster compounds were also simulated using the total spin St of the ground state only in conjunction with the usual Hamiltonian operator 2 for a single spin S where S was set to St and g = gt, D = Dt, and E/D = (E/D)t. For mononuclear complexes, the usual spin-Hamiltonian operator 2 for S = 3/2 was used. Simulations were done with our own package julX for exchange-coupled systems.32 The values were summed over a 16-point Lebedev grid33,34 to account for the powder distribution with respect to the field. For some samples, intramolecular interactions were taken into account in the simulations by using a Weiss temperature ΘW as a perturbation of the temperature scale, kT’ = k(T - ΘW).

| (1) |

| (2) |

Results and Discussion

Mononuclear Complexes

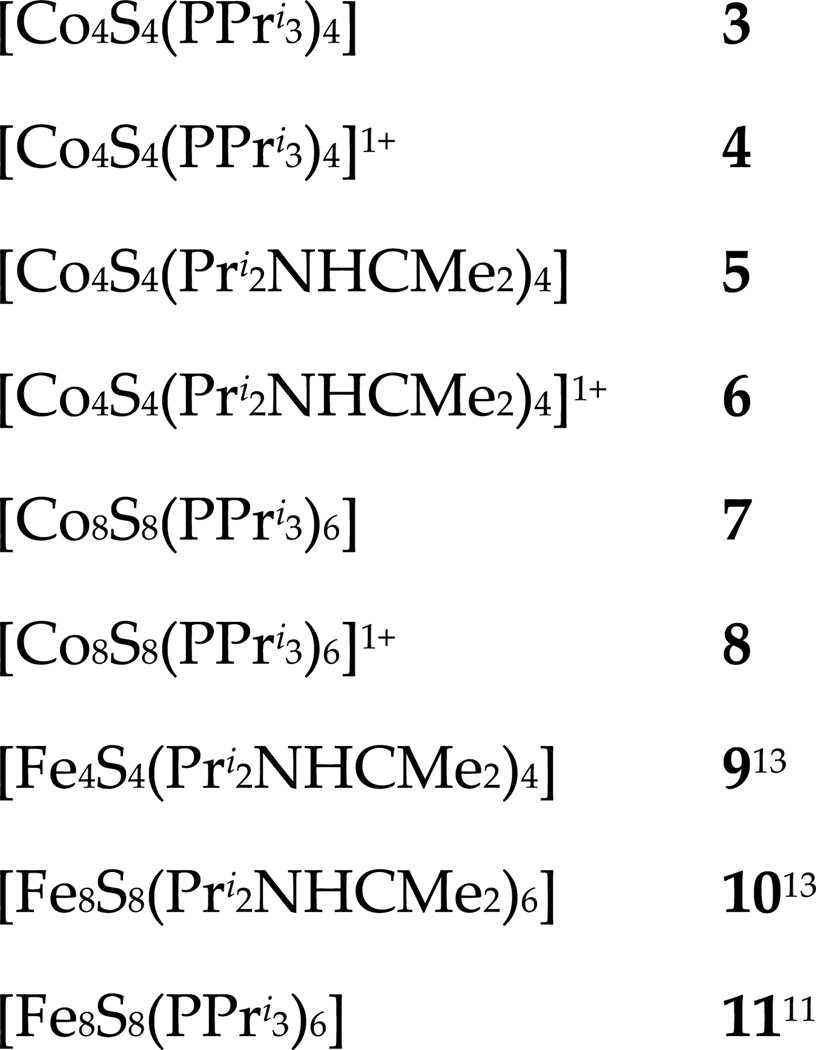

In seeking clusters with the cubane-type [Co4S4] core unit, we note stabilization of [Co4Se4] species by tertiary phosphines26 as well as reduced [Fe4S4]0,1+ clusters by phosphine10,11 and N-heterocyclic carbene13 terminal ligation. Anionic ligands such as thiolate increase cluster negative charge and promote oxidative instability. Mononuclear Co(II) phosphine complexes, many of the tetrahedral type [Co(PR3)2L2], abound. While carbene complexes of the divalent ions FeII, NiII, PdII, and PtII have been extensively investigated in this decade, 35–37 recent work on CoII carbenes has largely utilized tripodal ligands favoring tetrahedral stereochemistry.38,39 We wished to ascertain whether carbenes would be effective in stabilizing unconstrained high-spin tetrahedral CoII resembling sites in a cubane-type cluster. The complexes [Co(Pri2NHCMe2)2(SBut)2] and [Co(Pri2NHCMe2)2Cl2] are readily prepared. The structure of 1, shown in Figure 2, reveals tetrahedral stereochemistry with bond angles in the range 106–117°, normal Co-S bond lengths when compared to other tetrahedral [Co(SR)2L2] complexes (2.24–2.27 A),40,41 and Co-C bond lengths the same as or at most ca. 0.05 A longer than those in other tetrahedral CoII carbenes.38,39 In benzene solution, the complexes exhibit visible ligand field bands of tetrahedral (4A2g→4T1g(P)) parentage at energies similar to those observed for [Co(SR)2L2] species.41

Figure 2.

Structure of [Co(Pri2NHCMe2)2(SBut)2] showing 50% probability ellipsoids and the atom labeling scheme. Selected values: Co-C 2.085[1] A, Co-S 2.287[1] A, S1-Co-S2 116.66(6)°, C1-Co-C2 103.1(2)°, C1-Co-S1 112.1(2)°, C1-Co-S2 106.5(2)°, C2-Co-S1 106.0(2)°, C2-Co-S2 111.7(2)°.

The temperature dependencies of the magnetic moments of complexes 1 and 2 were determined at 2–300 K. Above 150 K, both exhibit constant moments of ca. 4.2 μB, which is close to the spin-only value of 3.87 μB (g = 2) for S = 3/2. Below 150 K, magnetic moments of both compounds increase and reach maxima near 10 K, a behavior typical of intermolecular ferromagnetic spin coupling. The full temperature dependencies could be reasonably well simulated with S = 3/2, g = 2.180 and ΘW = +0.8 K for 1, and g = 2.186 and ΘW = +1.2 K for 2.30 Reliable values for zero-field splitting parameters, however, could not be determined because of the effects of intermolecular interactions. A rough upper limit of |D| < 5 cm−1 could be estimated from systematic variations of D and ΘW in the simulations. These results show that when paired with conventional ligands the carbene, like phosphines, behaves as a normal weak field ligand that stabilizes tetrahedral CoII in the absence of any ligand-imposed structural preference. Both ligand types were utilized in cluster synthesis.

Cubane-type Clusters

(a) Neutral Clusters

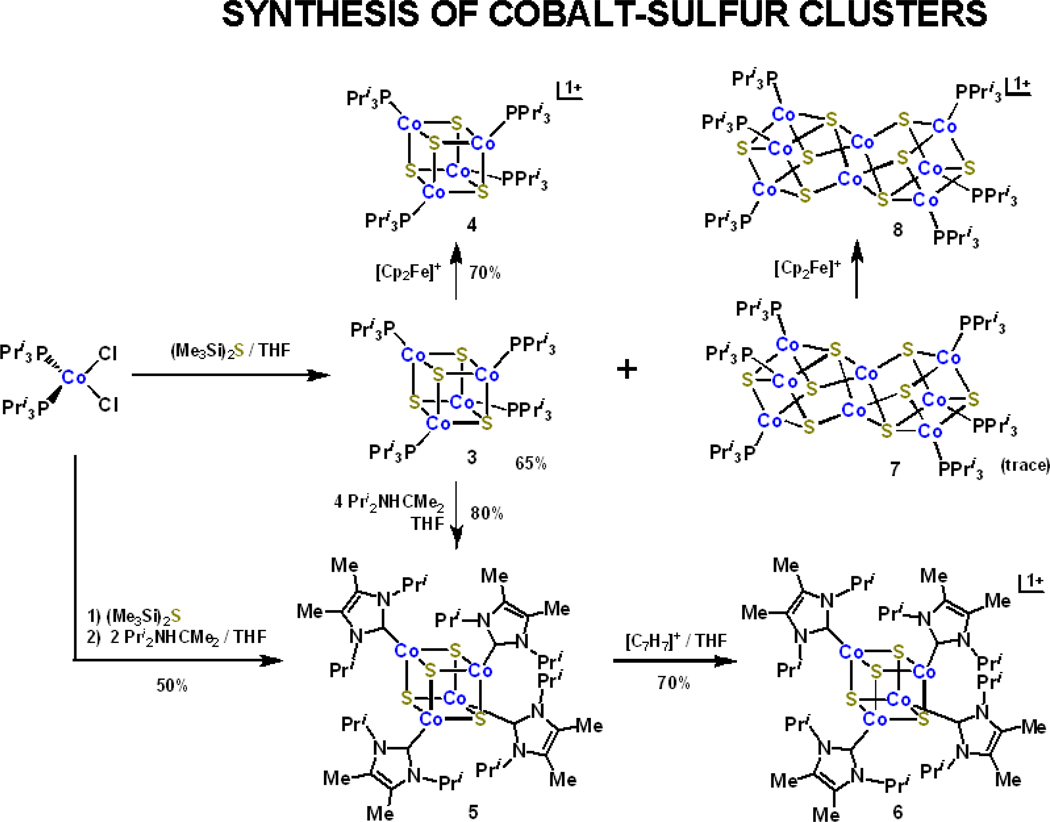

Synthetic methods are summarized in Figure 3. Phosphine cluster 3 is obtained by self-assembly reaction 3. Carbene cluster 5 is also prepared by self- assembly. In that system, 3 is first formed and subjected in situ to ligand displacement reaction 4 by the addition of excess Pri2NHCMe2. Alternatively, preisolated 3 is treated with a small excess of carbene to afford 5. Both methods lead to essentially the same yield of isolated product (ca. 50–60%). Analogous iron-sulfur carbene cluster 9 is also prepared by in a similar self-assembly system but with the intermediate formation of edge-bridged double cubane 1013 (see below). No intermediate was encountered in the preparation of 5 by self-assembly. However, in the preparation of 3 by reaction 3, a very small amount of a black crystalline byproduct was obtained. Its composition was established as [Co8S8(PPri3)6], comparative to 11, by an X-ray structure determination. As will be seen, the structures of clusters 7 and 11 are not the same. Reactions 4 and 513 provide a clear demonstration of the stronger binding affinity of a carbene vs. trialkylphosphine toward a common site, here tetrahedral FeII or CoII

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

Figure 3.

Scheme for the preparation of phosphine clusters 3, 4, 7, and 8 and carbene clusters 5 and 6. Clusters 7 and 8 were obtained in low yields as reaction by-products.

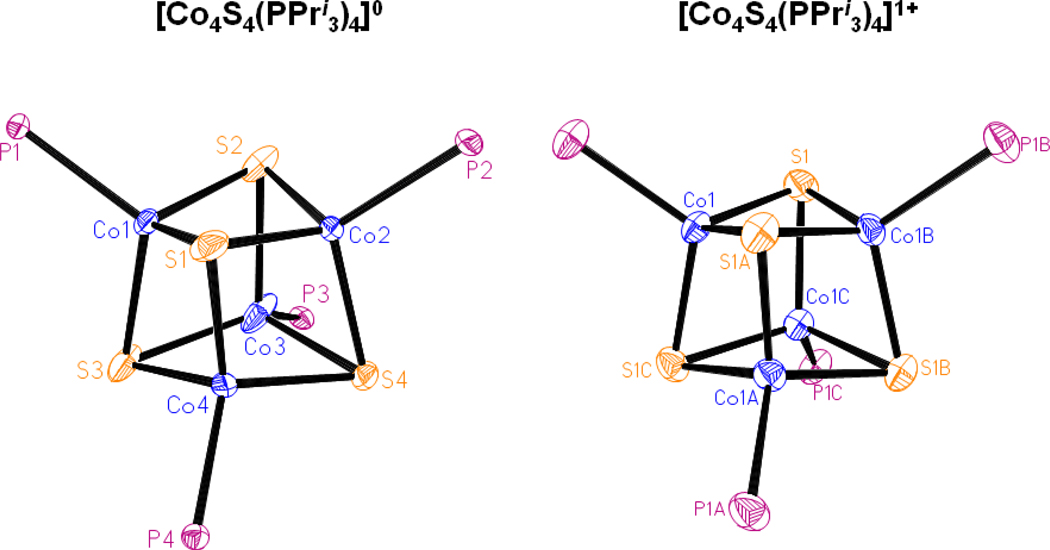

The structures of 3 and 5, set out in Figures 4 and 5, respectively, reveal the desired cubane-type stereochemistry with similar core dimensions as evident from the metric information in Table S-2. The CoII sites have trigonally distorted tetrahedral stereochemistry. In cluster 5, the mean Co-C bond lengths are ca. 0.1 A longer than in mononuclear 1, owing to steric interactions with the bulky carbene and thiolate ligands.

Figure 4.

Structures of [Co4S4(PPri3)4]0,1+ showing 30% probability ellipsoids and the atom numbering schemes. Ligands P(1,3,4)Pri3 of the neutral cluster are disordered over two positions (not shown). The cation has crystallo-graphically imposed Td symmetry. Isopropyl groups are omitted for clarity.

Figure 5.

Structures of [Co4S4(Pri2NHCMe2)4]0,1+ showing 30% probability ellipsoids and the atom numbering schemes.

The Co4S4 cores approach Td symmetry; no systematic deviations from that symmetry are evident. The structural similarity between 3 and 5 and their close relationship to iron-sulfur cluster 9 is emphasized by the comparisons of mean distances and volumes calculated from atomic coordinates42 in Table 1. The cause of the 0.09 A longer mean Co-Co distance and correspondingly larger Co4 and Co4S4 volumes in 3 compared to 5 is unclear. The longer mean Fe-S bond length and larger S4 and Fe4S4 volumes in 9 vs. the cobalt clusters arises from the difference of 0.05 A in Shannon radii43 between tetrahedral FeII and CoII.

Table 1.

Summary of Core Structural Comparisons of Cubane-type Clusters [M4S4L4]0,1+(M = Co, Fe; L = PPri3, Pri2NHCMe2)

| cluster | M-S (A)a | M-M (A)a | V(M4) (A3)b | V(S4) (A3) | V(M4S4) (A3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Co4S4(PPri3)4]c | 2.223[8] | 2.603[9] | 2.08 | 5.26 | 8.50 |

| [Co4S4(Pri2NHCMe2)4]d | 2.25[1] | 2.69[2] | 2.30 | 5.33 | 9.12 |

| [Fe4S4(Pri2NHCMe2)4]e,f | 2.33[2] | 2.68[1] | 2.26 | 6.14 | 9.47 |

| [Co4S4(PPri3)4]1+ f | 2.206(1) | 2.607(1) | 2.10 | 5.06 | 8.44 |

| [Co4S4(Pri2NHCMe2)4]1+ g | 2.22[1] | 2.66[2] | 2.22 | 5.06 | 8.77 |

(b) Redox Series and Oxidized Clusters

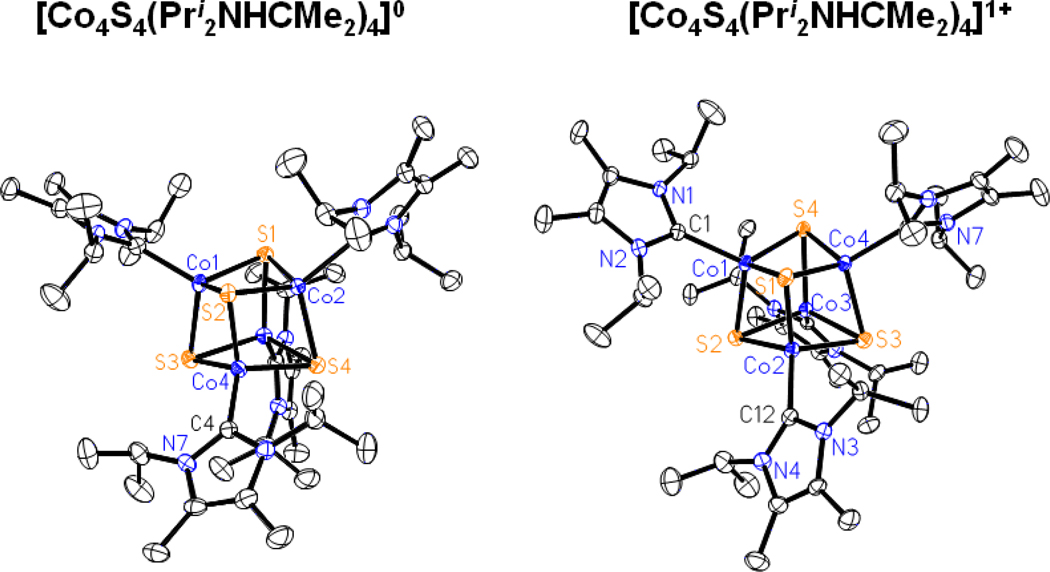

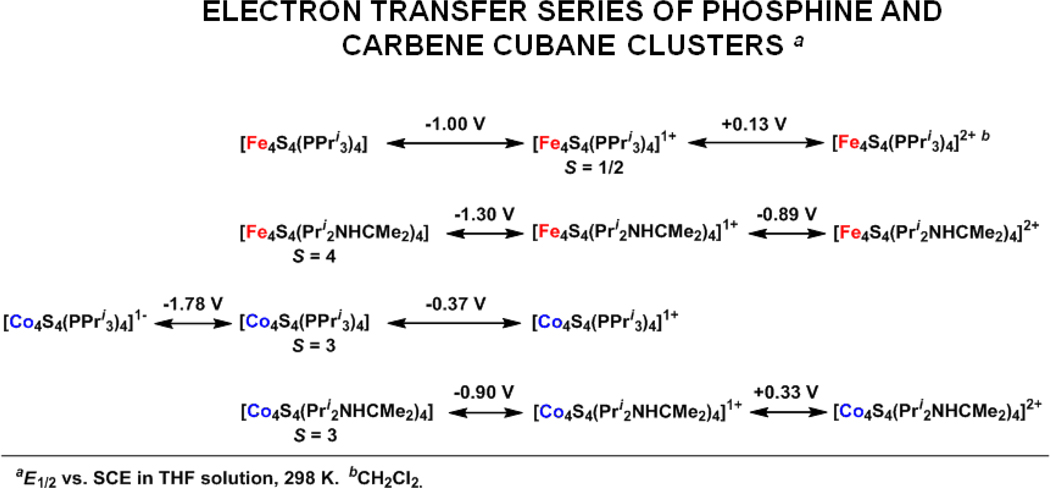

Voltammograms of THF solutions prepared from the two neutral clusters are presented in Figure 6. Each supports two quasireversible processes, a reduction and oxidation for 3 and two oxidations for 5. The latter showed no reduction out to −2.0 V. The data are summarized and compared with the behavior of iron cluster 913 and [Fe4S4(PPri3)]1+ 11 in Figure 7. Two trends in the redox couples are defined by decisively large potential differences: EFe 0/1+ < ECo0/1+ at constant ligand and Ecarbene0/1+;1+/2+ < Ephosphine0/1+;1+/2+ at constant metal. The first trend has one precedent with cubane (Fe4S4, CoFe3S4) clusters.44 The second and more significant trend implies that carbene is a more effective σ-donor to the core, resulting in a greater ease of electron loss. This statement is consistent with previous evidence that carbenes are more effective electron donors than the more basic phosphine ligands,45–47 We are unaware of other quantitative data bearing on the comparative redox potentials of carbene and phosphine ligation.

Figure 6.

Cyclic voltammograms (100 mV/s) of ca. 3 mM THF solutions prepared from [Co4S4(PPri3)4] (upper) and [Co4S4(Pri2NHCMe2)4] (lower). Peak potentials vs. SCE are indicated.

Figure 7.

Summary of redox reactions of [M4S4(PPri3)4] and [M4S4(Pri2NHCMe2)4] (M = Fe, Co) in THF solutions showing E½ values vs. SCE. The potential of the top reaction refers to dichloromethane solution.

Clusters 3 and 5 are readily oxidized to monocations 4 and 6 by ferrocenium and tropylium ions, respectively, and isolated as crystalline salts. Their structures retain the cubane-type geometry (Figures 4 and 5) with dimensions similar to those of the neutral clusters. While these reactions lead to formal mixed-valence (3CoII + CoIII) cores, the metric parameters in Table S-330 provide no distinction in metal sites and thus suggest electron delocalization in the [Co4S4]1+ core or disorder. The small decreases in S4 and Co4S4 volumes imply (but not proved) removal of an electron from an antibonding orbital with substantial sulfur character.

(c) Magnetic Ground States

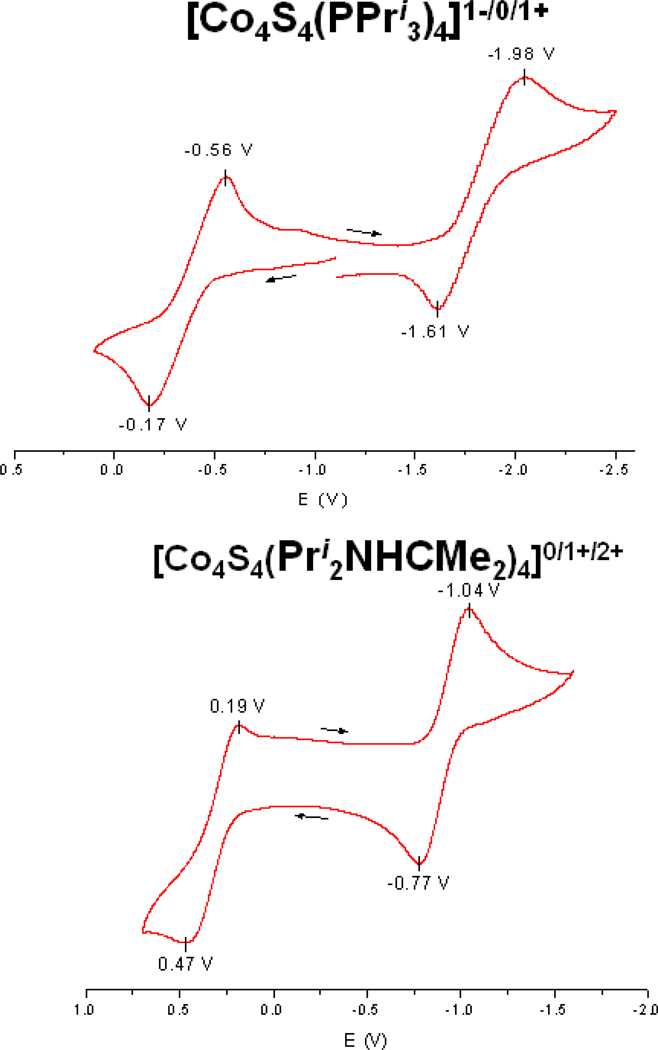

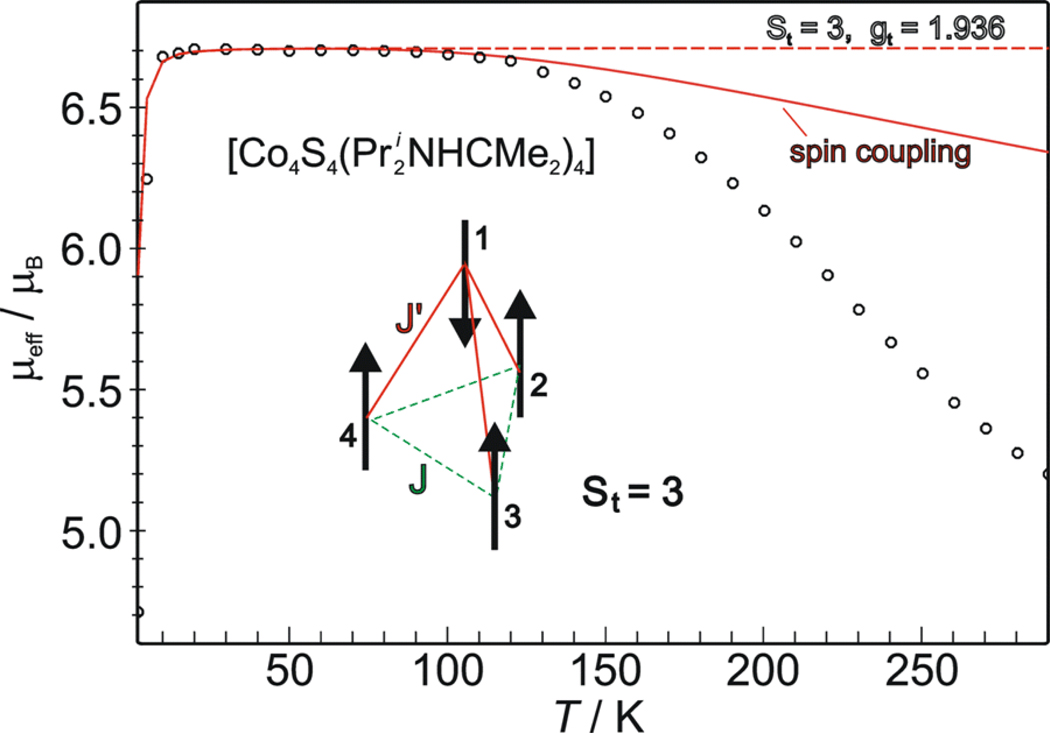

The temperature dependence of the effective magnetic moment of carbene cluster 5, depicted in Figure 8, steeply increases from 4.7 μB at 2 K to 6.7 μB at 10 K, which persists up to about 100 K. The moment then decreases, reaching 5.2 μB at 300 K. These large magnetic moments are not necessarily expected because a simple analysis of a symmetic [Co4S4]0 core with equal exchange couplings between metal sites predicts a diamagnetic ground state (St = 0). In contrast, the value observed for 5 at 10–100 K is close to the spin-only value μso = 2(3·4)½ = 6.93 μB for S = 3. Accordingly, a preliminary simulation with St = 3 and gt = 1.936 (dashed line) provides a good approximation to the experimental data up to about 100 K, including the decline of μeff below 10 K where the effect appears to be due to field saturation. Above 120 K the simple model fails, apparently because manifolds with St < 3 become populated. The low average g-value used in the approximate treatment is remarkable because CoII, with a more than half-filled d-shell (3d7), should have g > 2. This matter is discussed below.

Figure 8.

Temperature dependence of the effective magnetic moment of solid [Co4S4(Pri2NHCMe2)4] measured at applied field B = 1 T. The dashed line is a preliminary simulation with S = 3, g = 1.936, and D = 0. The solid line represents a generic spin Hamiltonian simulation with four spins: Si = 3/2, i = 1–4, arranged in pyramidal topology with one unique site (spin 1) and two different exchange coupling constants J = −420 cm−1 for the interactions (1–2), (1–3), and (1–4), and J' = −100 cm−1 for (2–3), (3–4), and (4–2). Other parameters are g1 = 2.17, g234 = 2.0, and Di = 0. Inset: spin-coupling scheme for the St = 3 ground state.

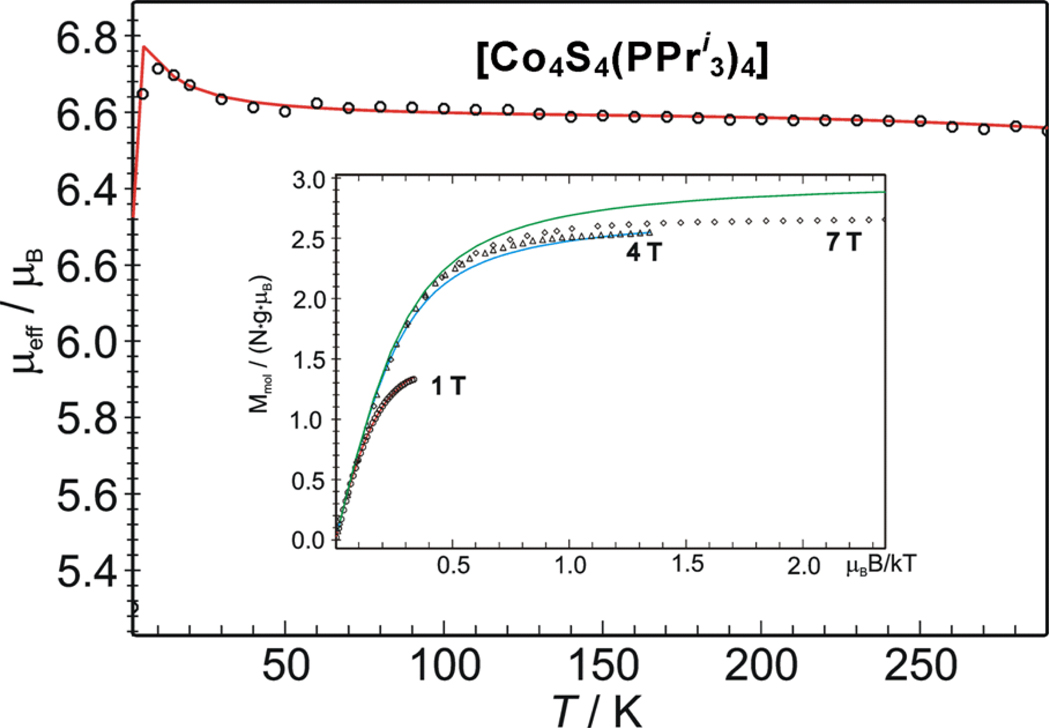

The magnetic data for phosphine cluster 3 in Figure 9 reveals μeff ≈6.6 μB at 10–100 K, similar to the behavior of 5. The maximum at lower temperatures is indicative of intermolecular interactions, and the values above 100 K decrease much less than those of 5. The latter behavior indicates a different extent of spin coupling for the two clusters and a higher separation of excited spin states for 3. The ground state spin St = 3 was corroborated by multifield magnetization measurements and data fits. Nesting of the isofield magnetization curves at B = 1, 4, and 7 T is consistent only with a spin septet with weak zero-field splitting, although it proved difficult to simulate accurately the entire data set because of intermolecular interactions. The data at 4 T and 7 T approach saturation close to Mmol/NgμB = 3, expected forSt = 3 with g = 2. The deviation suggests a lower g-value for the ground state, as found in simulations.

Figure 9.

Temperature dependence of the effective magnetic moment of solid [Co4S4(PPri3)4] measured at applied field B = 1 T. The solid line represents a generic spin Hamiltonian simulation with four spins: Si = 3/2, i = 1–4, arranged in pyramidal topology with one unique site (spin 1) and two different exchange coupling constants J = −600 cm−1 for the interactions (1–2), (1–3), and (1–4), and J' = −100 cm−1 for (2–3), (3–4), and (4–2). Other parameters are g1 = 2.27, g234 = 2.0, Di = 0, ΘW = 0.7 K. Inset: multi-field variable-temperature measurement of magnetization. The solid lines represent spin Hamiltonian simulations obtained with St = 3, gt = 1.90, Di = −1.95, E/Di = 0.2, ΘW = 0.7 K.

The paramagnetism of 3 and 5 is reminiscent of the situation with [Fe4S4]0 clusters of the iron protein of Av nitrogenase,7 the dehydratase activator protein,9 and synthetic cluster 9.13–15 The four FeII sites are exchange-coupled via four μ3-S bridges such that the local spins SFe = 2 yield St = 3·2 -2 = 4 for the cluster ground state. It has been observed that the all-ferrous clusters must have lower than cubic symmetry and the distortion appears to stabilize the highly reduced system.14,15 Spectroscopic asymmetry first became evident in the Mössbauer spectrum of the Av iron protein, which showed two resolved quadrupole doublets in the 3:1 intensity ratio with distinct quadrupole and magnetic hyperfine couplings.5 The spin of one FeII site is aligned opposite to those of the other three sites. The same 3:1 pattern is found with the activator protein and synthetic cluster.

Although we do not have positive indication of a 3:1 site core geometric distortion in 3 and 5, and hyperfine measurements are elusive for these integer spin systems, we assume the same spin topology.48 The 3:1 spin-coupling scheme readily rationalizes the ground state of [Co4S4]0 cores with SCo = 3/2: St = 3(3/2) - 3/2 = 3. Corresponding spin Hamiltonian simulations yield convincing results for the low temperature magnetic data of 5 (Figure 8). Two independent coupling constants have been used to model in the antiferromagnetic interaction of three similar and one different metal site. The observed spin arises from the antiparallel orientation of site (1) relative to sites (2–4) when J-coupling exceeds J’-coupling.

While the magnetic data firmly establish the St = 3 ground state for clusters 3 and 5, certain limitations in the analyses presented in Figures 8 and 9 are noted. The specified coupling constants are not unique. Many other J/J’ combinations yield virtually the same result including the decrease in moment of 5 above 120 K. Apparently, we cannot observe or resolve a sufficient number of excited states to arrive at a unique fit. The lower part of the spin energy spectrum computed using the parameters for the spin Hamiltonian simulation for 5 consists of a sequence of septet, quintet, triplet and singlet states (Figure S-3A).30 The corresponding Boltzman population of the lowest manifolds (Figure S-3B) qualitatively explains the decrease in μeff above 120 K as the onset of thermal population of the first excited spin quintet. However, we were unable to find satisfactory combinations of coupling constants Jij that would shift the triplet and singlet states sufficiently close to the ground state to improve the fit. The virtually constant moment of 3 at 10–300 K indicates exclusive population of the spin septet state over than temperature interval. While this behavior constrains the possible J/J’ values, a unique solution is not possible. The values give for J and J’ (Figure 9) exemplify those required for a satisfactory fit.49

In the context of the spin coupling scheme, the low g-values of the St = 3 ground state derive mainly from the negative contribution of the unique site (1) with respect to the other three if g1 > 2 supersedes the positive contributions g234 to gt from the other sites. Because S1 is oriented antiparallel to the total spin, the basic spin projection scheme of the fictitioius intermediate spin S234 = 9/2 formed by the parallel arrangement of S2, S3, and S4 and the unique site S1 yields for the resulting total spin gt = −3/8 g1 + 11/8 g234. Here g234 is the same as the g-value of each CoII at sites 2, 3, and 4. In the simulation for 5, we obtained the correct (observed) value gt = 1.936 with g1 = 2.17 and g234 = 2, and for 3 gt = 1.90 with g1 = 2.27 and g234 = 2. Again, the choice of values is not unique, but those given demonstrate that the experimental data are consistent with the site values gCo > 2.

Octanuclear Clusters

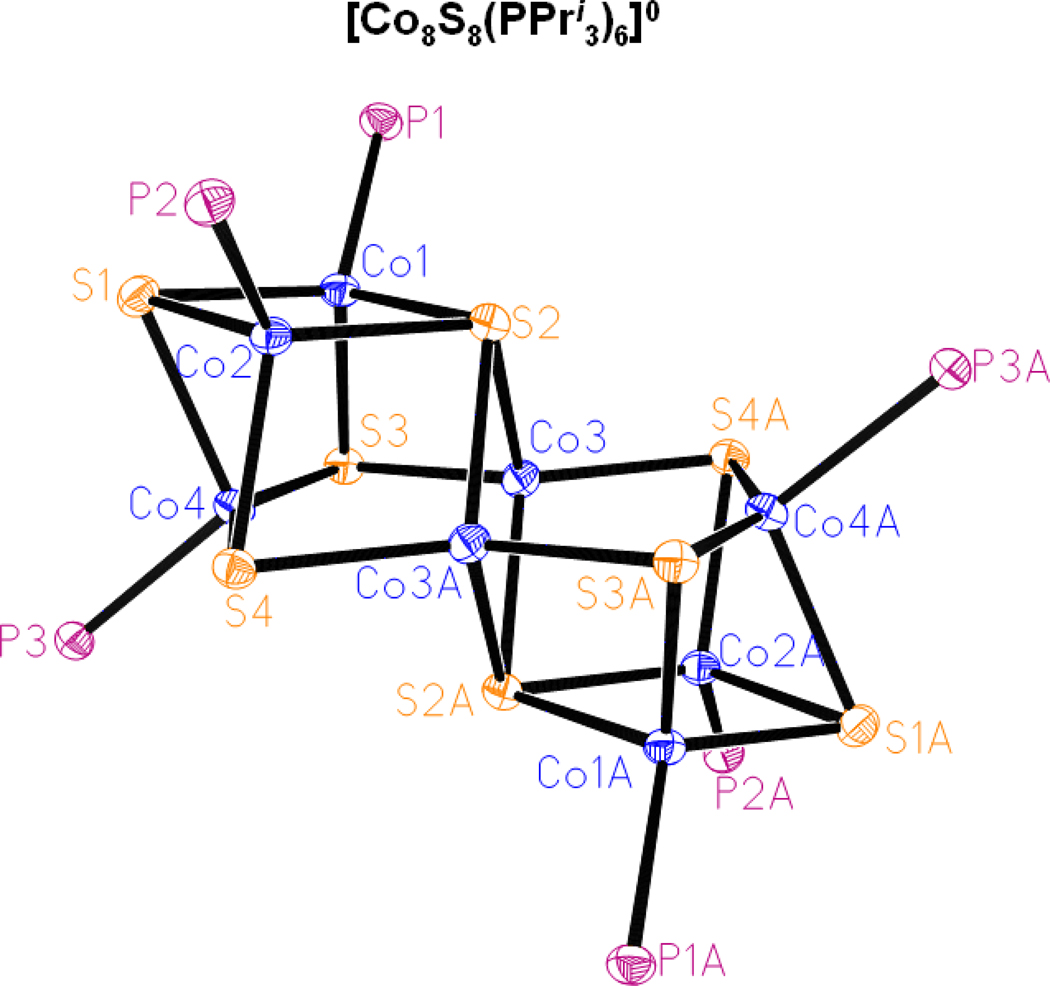

As noted above, phosphine cluster 7 was separated manually in small amounts in the synthesis of 3 by self-assembly. Its structure, which has imposed centrosymmetry, is provided in Figure 10. The [Co8(μ3-S)6(μ4-S)2] core is not built of cubane units. Two Co3S3 fragments (Co(1,2,4)S(1,3,4) and its symmetry equivalent) are bridged by a total of four Co-(μ4-S) and four Co-(μ3-S) interactions to an interior Co(3,3A)S(2,2A) rhomb with dimensions Co-S 2.250[3] A, Co-Co 2.575(1) A, S-Co-S 69.81(3)°, and Co-S-Co 110.19(3)°. The Co8 part of the structure may be visualized as two Co5 square pyramids sharing an edge (Co3-Co3A)with two apical Co atoms (Co4,4A) on opposite sites of the two basal planes which are themselves coplanar. Also identifiable are two Co4S square pyramids with the same common edge and oppositely placed apical μ4-S(2,2A) atoms. All Co sites are four-coordinate and approach tetrahedral stereochemistry. Atoms Co(3,3A) show the most pronounced deviation, with one large angle S3-Co3-S4A = 133.87(3)°; other angles at these atoms are the 100.6–110.2° range.

Figure 10.

Structure of [Co8S8(PPr i3)6] showing 30% probability ellipsoids and the atom numbering scheme. The cluster has crystallographically imposed centrosymmetry. Isopropyl groups are omitted for clarity. Selected interatomic distances (A) and angles (deg): Co-(μ3-S) 2.21[4], Co-(μ4-S) 2.24[1], Co-Co 2.59[7], Co3–Co4 2.952(1), Co3A–Co4 2.913(1), Co-P 2.24[1], S2-Co3-S2A 110.19(3), Co3-S2-Co3A 69.81(3).

Similarly, in the preparation of cation cluster 4, the compound [8](BF4) was obtained as a byproduct in minor amounts. The structure of the cation (not shown) is nearly indistinguishable from that of 7, and there is no evidence of a discrete CoIII site. Further structural details on 7 and 8 are available.30 These structures are precedented only by the compounds [Co8Se8(PPh3)6][CoCl3(PPh3)] and [Co8Se8(PPh3)6][Co6Se8(PPh3)6] originating from the reaction of [CoCl3(PPh3)]1− and (Me3Si)2Se.27

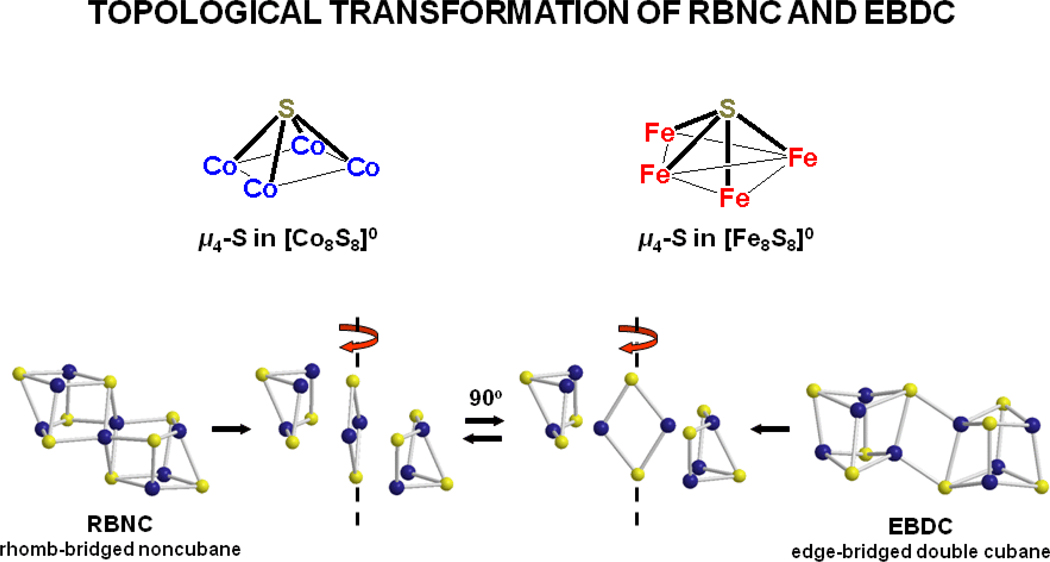

Although we have not been able to devise a synthetic method for which 7 is the principal product, we present this cluster here because of our interest in and utilization of Fe8S8 double cubane clusters in the preparation of other high-nuclearity clusters. Evidently, for [M8S8] cores with tetrahedral sites there are at least two structural solutions, the edge-bridged double cubane (EBDC) and the rhomb-bridged non-cubane (RBNC). The present examples of these structures are topological isomers. When considered in terms of core valence electron count, stable homometallic structures are currently restricted to 119–120 e− for RBNC (7, 8) and 110–112 e− for EBDC (10, 11, [Fe8S8(PPri3)4(SSiPh3)2]11).50 This observation suggests that the two structures might be of competitive energy somewhere in between these limits. We note the conceptual least-motion RBNC ← EBDC interconversion of Figure 11. Proceeding from RBNC, cluster deconstruction affords two M3S3 fragments and the interior rhomb. Rhomb rotation by 90° around the S-S axis and recombination with the trinuclear fragments generates the EBDC. The process in effect converts two square pyramidal M4S entities in the original structure to two trigonal bipyramidal M4S substructures The cluster core [Fe4Co4S8], if synthetically accessible with tolerably small dimensional differences (Table 1), is one candidate with which to address the issue of relative stability of these two structures.

Figure 11.

Conceptual topological transformation between a rhomb-bridged noncubane (RBNC) and edge-bridged double cubane (EBDC) structures of clusters with [M8S8] cores.

Summary

The following are the principal results and conclusions of this investigation.

The assembly system CoCl2/Pri3P/(Me3Si)2S in THF affords the cluster [Co4S4(PPri3)4], which upon reaction with the carbene Pri2NHCMe2 yields [Co4S4(Pri2NHCMe2)4]. These compounds can be oxidized to monocations by reactions with ferrocenium or tropylium. These species are the first examples of [M4S4L4]z clusters with cubane-type stereochemistry, tetrahedral M sites, and a transition metal other than iron.

The clusters in (1) are essentially isostructural with one another and with [Fe4S4(Pri2NHCMe2)4]. Small dimensional differences between the cobalt and iron carbene cluster are mainly due to differences in MII radii. Structures of mixed-valence cation clusters do not reveal electronically localized sites.

Ligand substitution of phosphine by carbene in (1) and with iron clusters13 and lower redox potentials for the 0/1+ and 1+/2+ couples of carbene vs. phosphine clusters at constant metal are consistent with carbene being the better electron donor, at least to tetrahedral CoII and FeII.

[Co4S4(PPri3)4] and [Co4S4(Pri2NHCMe2)4] have St = 3 ground states,51 which may be rationalized in terms of coupling amongst three parallel and one antiparallel S = 3/2 spins of the CoII sites. This 3:1 pattern of spin-coupling applies also to [Fe4S4(Pri2NHCMe2)4], whose St = 4 ground state motivated this investigation. A theoretical model of the origin of the spin-coupling scheme for the cobalt clusters is not yet available. A model based on spontaneous distortions of [Fe4S4]0 core has been recently described.15

The [Co8S8]0 core of [Co8S8(PPri3)6], obtained as a minor biproduct in the synthesis of [Co4S4(PPri3)4], is compositionally analogous to but structurally different from the [Fe8S8]0 core of known clusters. The clusters are topological isomers. The cobalt cluster is a rhomb-bridged noncubane (RBNC) and the iron cluster an edge-bridged double cubane (EBDC). Core relative stabilility may be related to valence electron count. A conceptual model for the RBNC ← EBDC interconversion is presented. The EBDC structure is populated by homometallic Fe8S8 and heterometallic M2Fe6S8 cluster whereas the RBNC structure is currently known only for Co8Q8 (Q = S, Se) clusters.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This research was supported at Harvard University by NIH Grant GM 28856.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. X-ray crystallographic files in CIF format for the seven compounds in Table S-1, bond angles and distances, selected interatomic distances and angles of 3–6, magnetic data for compounds 1 and 2, calculated spin manifold energies, and structural depictions of clusters 7 and 8.

References and Notes

- 1.Holm RH. Iron-Sulfur Clusters. In: Que L Jr., Tolman WA, editors. Bio-coordination Chemistry. Oxford: Elsevier; 2004. pp. 61–90. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rao PV, Holm RH. Chem.Rev. 2004;104:527–559. doi: 10.1021/cr020615+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koay MS, Antonkine ML, Gärtner W, Lubitz W. Chem.Biodiversity. 2008;5:1571–1587. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200890145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogino H, Inomata S, Tobita H. Chem.Rev. 1998;98:2093–2121. doi: 10.1021/cr940081f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Angove HC, Yoo SJ, Burgess BK, Münck E. J.Am.Chem.Soc. 1997;1997:8730–8731. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Angove HC, Yoo SJ, Münck E, Burgess BK. J.Biol.Chem. 1998;273:26330–26337. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.41.26330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoo SJ, Angove HC, Burgess BK, Hendrich MP, Münck E. J.Am.Chem.Soc. 1999;121:2534–2545. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strop P, Takahara PM, Chiu H-J, Angove HC, Burgess BK, Rees DC. Biochemistry. 2001;40:651–656. doi: 10.1021/bi0016467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hans M, Buckel W, Bill E. J.Biol.Inorg.Chem. 2008;13:568–579. doi: 10.1007/s00775-008-0345-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goh C, Segal BM, Huang J, Long JR, Holm RH. J.Am.Chem.Soc. 1996;118:11844–11853. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou H-C, Holm RH. Inorg.Chem. 2003;42:11–21. doi: 10.1021/ic020464t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scott TA, Berlinguette CP, Holm RH, Zhou H-C. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.USA. 2005;102:9741–9744. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504258102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deng L, Holm RH. J.Am.Chem.Soc. 2008;130:9878–9886. doi: 10.1021/ja802111w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Münck E, Bominaar EL. Science. 2008;321:1452–1453. doi: 10.1126/science.1163868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chakrabarti M, Deng L, Holm RH, Münck E, Bominaar EL. Inorg.Chem. 2009;48:2735–2747. doi: 10.1021/ic802192w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang F, Lei X, Huang Z, Hong M, Kang B, Wu D, Liu H. J.Chem.Soc., Chem.Commun. 1990:1655–1656. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simon GL, Dahl LF. J.Am.Chem.Soc. 1973;95:2164–2174. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo S, Hauptmann R, Losi S, Zanello P, Schneider JJ. J.Cluster Sci. 2007;18:237–251. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cecconi F, Ghilardi CA, Midollini S, Orlandini A. Polyhedron. 1986;5:2021–2031. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hong M, Huang Z, Lei X, Wei G, Kang B, Liu H. Polyhedron. 1991;10:927–934. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diana E, Gervasio G, Rossetti R, Valdemarin F, Bor G, Stanghellini PL. Inorg.Chem. 1991;30:294–299. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bencini A, Ghilardi CA, Orlandini A, Midollini S, Zanchini C. J.Am.Chem.Soc. 1992;114:9898–9908. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cecconi F, Ghilardi CA, Midollini S, Orlandini A. Inorg.Chim.Acta. 1991;184:141–145. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang F, Huang L, Lei X, Liu H, Kang B, Huang Z, Hong M. Polyhedron. 1992;11:361–363. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Christou G, Hagen KS, Bashkin JK, Holm RH. Inorg.Chem. 1985;24:1010–1018. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fenske D, Ohmer J, Hachgenei J. Angew.Chem.Int.Ed.Engl. 1985;24:993–995. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fenske D, Ohmer J, Merzweiler KZ. Naturforsch. 1987;42b:803–809. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuhn N, Kratz T. Synthesis. 1993:561562. [Google Scholar]

- 29.The compound [Co(PPri3)2Cl2] has been previously isolated: Allen EA, Del Gaudio J.Chem.Soc., Dalton Trans. 1975:1356–1360.

- 30.See paragraph at the end of this article for Supporting Information available.

- 31.O'Connor CJ. Prog.Inorg.Chem. 1982;29:203–283. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Available through http://ewww/mpi-muelheim.mpg.de/bac/logins/bill/julX_en.php

- 33.Lebedev VI, Laikov DN. Dokl. Math. 1999;59:477–481. [Google Scholar]

- 34.A Fortran code to generate Lebedev grids up to order L = 131 is available at http//:server.ccl.net/cca/software/SOURCES/

- 35.Herrmann WA. Angew.Chem.Int.Ed. 2002;41:1290–1309. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020415)41:8<1290::aid-anie1290>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crudden CM, Allen DP. Coord.Chem.Rev. 2004;248:2247–2273. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hahn FE, Jahnke MC. Angew.Chem.Int.Ed. 2008;47:3122–3172. doi: 10.1002/anie.200703883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hu X, Castro-Rodriguez I, Meyer K. J.Am.Chem.Soc. 2004;126:13464–13473. doi: 10.1021/ja046048k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cowley RE, Bontchev RP, Duesler EN, Smith JM. Inorg.Chem. 2006;45:9771–9779. doi: 10.1021/ic061299a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Corwin DT, Jr., Gruff ES, Koch SA. J.Chem.Soc., Chem.Commun. 1987:966–967. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Corwin DT, Jr., Fikar R, Koch SA. Inorg.Chem. 1987;26:3080–3082. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaspar JS, Lonsdale K. International Tables for X-Ray Crystallography. Birmingham, U. K.: Kynoch; 1967. pp. 36–49. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shannon RD. Acta Crystallogr. 1976;A32:751–767. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhou J, Raebiger JW, Crawford CA, Holm RH. J.Am.Chem.Soc. 1997;119:6242–6250. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huang J, Schanz H-J, Stevens ED, Nolan SP. Organometallics. 1999;18:2370–2375. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Perrin L, Clot E, Eisenstein O, Loch J, Crabtree RH. Inorg.Chem. 2001;40:5806–5811. doi: 10.1021/ic0105258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chianese AR, Li X, Janzen MC, Faller JW, Crabtree RH. Organometallics. 2003;22:1663–1667. [Google Scholar]

- 48.In view of the magneto-elastic coupling found for all-ferrous 9,15 we assume that the dependencies of the exchange coupling constants and symmetry-breaking deformations ((dJ/dr)Δr) may be stronger for the cobalt than iron clusters, such that small deformations already afford sizeable changes in exchange energy. Additionally, the unique spin site (1 in Figure 8) may be disordered in the crystalline state

- 49.The slight slope in the data above 50 K results from intermolecular interactions described by ΘW = −0.7 K to account for the low temperature maximum in the fit and not from thermal population of an excited state

- 50.Given the existence of [Mo2Fe6S8]4+ and [V2Fe6S8]2+ clusters, the lower limit for the EBDC structure when isolated heterometallic clusters are included is presently 104 e− Osterloh F, Segal BM, Achim C, Holm RH. Inorg. Chem. 2000;39:980–989. doi: 10.1021/ic991016x. Hauser C, Bill E, Holm RH. Inorg. Chem. 2002;41:1615–1624. doi: 10.1021/ic011011b.

- 51.Theses results suggest a reexamination of the magnetism of [Co4Se4(PPh3)4], which is reported to be diamagnetic.26

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.