Abstract

Meiotic recombination requires the action of several gene products in both Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Drosophila melanogaster. Genetic studies in D. melanogaster have shown that the mei-W68 gene is required for all meiotic gene conversion and crossing-over. We cloned mei-W68 using a new genetic mapping method in which P elements are used to promote crossing-over at their insertion sites. This resulted in the high-resolution mapping of mei-W68 to a <18-kb region that contains a homolog of the S. cerevisiae spo11 gene. Molecular analysis of several mutants confirmed that mei-W68 encodes an spo11 homolog. Spo11 and MEI-W68 are members of a family of proteins similar to a novel type II topoisomerase. On the basis of this and other lines of evidence, Spo11 has been proposed to be the enzymatic activity that creates the double-strand breaks needed to initiate meiotic recombination. This raises the possibility that recombination in Drosophila is also initiated by double-strand breaks. Although these homologous genes are required absolutely for recombination in both species, their roles differ in other respects. In contrast to spo11, mei-W68 is not required for synaptonemal complex formation and does have a mitotic role.

Keywords: Meiotic recombination, synaptonemal complex, Drosophila, meiosis, double-strand break

Meiotic recombination events result when a break in the DNA is repaired using the homolog as a template. Part of this reaction occurs between homologs that are paired tightly and held together by a structure known as the synaptonemal complex. In addition, most evidence is consistent with the idea that meiotic recombination is mediated by an organelle associated with the synaptonemal complex known as the recombination nodule (Carpenter 1987). In most organisms, the majority of events resolve as gene conversions, with 20% or less becoming crossovers (Carpenter 1987; Hilliker et al. 1988). Only the small percentage of events that become crossovers mature into chiasmata. As chiasmata direct segregation by linking and orienting homologous chromosomes on the developing spindle so that they segregate to opposite poles at anaphase (Hawley 1988), it is easy to see why crossovers are central to the progression of meiosis. Without crossovers and, therefore, chiasmata, the proper segregation of homologous chromosomes could not be ensured.

With the notable exception of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, nothing is known about how meiotic recombination is initiated. Two models incorporating the Holliday junction have dominated thinking about meiotic recombination. In the first, Meselson and Radding (1975) proposed that a Holliday junction was initiated with a single-strand break on one homolog. In the second model, Szostak et al. (1983) proposed that a double Holliday junction was initiated with a double-strand break in one homolog. In S. cerevisiae, there is abundant physical evidence that double-strand breaks are involved in meiotic recombination. Double-strand breaks are induced early in meiotic prophase and are resolved eventually as recombinants (for review, see Lichten and Goldman 1995). Often these breaks occur at hot spots, which tend to be regions of open chromatin within promoters (Wu and Lichten 1994). Additional support for the double-strand break model came from the physical identification and analysis of joint molecules and double Holliday junctions in meiotic prophase (Schwacha and Kleckner 1995). These results have not, however, been extended to any other organism.

To characterize the initiation of meiotic recombination in Drosophila melanogaster, we have been studying mutants in which meiotic gene conversion is reduced or eliminated. Our rationale is that if gene conversion is eliminated, it is possible that the defect is a failure to initiate recombination. This assay differentiates these mutants from those that reduce crossing over but have no effect on gene conversion (Carpenter 1984). Previous work described mutants in two genes, mei-W68 and mei-P22, that meet these criteria (McKim et al. 1998). In this paper we report the cloning of mei-W68 and show that it encodes a homolog of Spo11, known previously to be required for double-strand break formation in S. cerevisiae (Cao et al. 1990). The homology to spo11 gives strong support to our conclusion that mei-W68 is required for the initiation of meiotic recombination. A surprising aspect of the mei-W68 mutant phenotype is that it affects somatic as well as meiotic cells. In S. cerevisiae, the expression of spo11 and the mutant phenotypes are meiosis-specific (Atcheson et al. 1987). Conversely, mei-W68 is transcribed in many somatic cell types and mei-W68 mutants exhibit defects during the mitotic cell cycle (Baker et al. 1978; Lutken and Baker 1979).

Results

Genetic mapping of mei-W68 by a new method using P element-mediated crossing-over

mei-W68 was cloned based on its genetic map position. Preliminary mapping experiments placed mei-W68 between 56C1–2 and 56F5 (Fig. 1 and Materials and Methods). Higher resolution mapping was accomplished using P-element insertion mutations in the 56C–56F region from the Drosophila Genome Project (Spradling et al. 1995). This approach facilitated the cloning of the gene for two reasons: First, there were insertions present at a relatively high density, and second, the DNA flanking each P element could be isolated by inverse PCR and then used as a probe to determine the location of the insertion on the physical map.

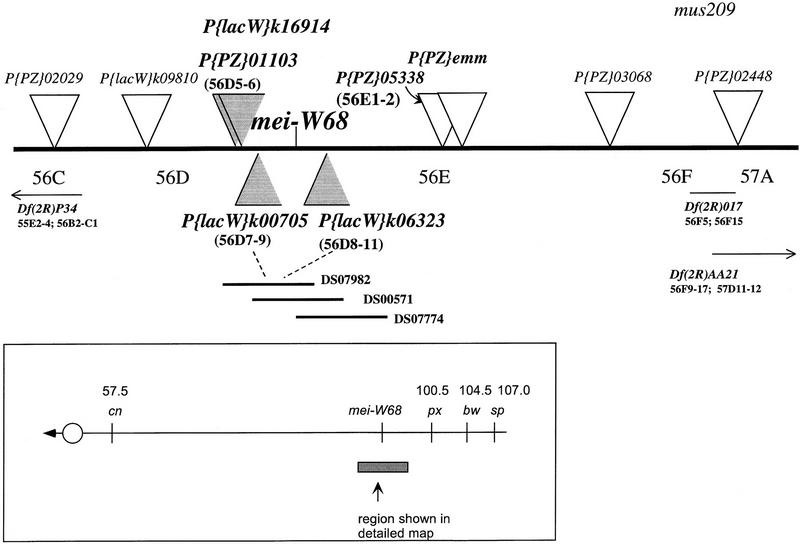

Figure 1.

Genetic map of the mei-W68 region. mei-W68 was mapped relative to the P-element insertions (triangles). The P-element insertions flanking the mei-W68 locus that were inserted within the overlap of P1 clones DS07982 and DS00571 are shaded. Deficiencies that complemented mei-W68 are shown with their cytogenetic breakpoints. The P{PZ}05338 insertion is an allele of smooth (Lage et al. 1997). P{PZ}01103 is inserted at the hts locus (Berkeley Drosphila Genome Project).

The major problem in high-resolution mapping of mei-W68 (or any gene) relative to closely linked P elements is the difficulty in generating useful recombinants. We have used two features of P-element biology to collect recombinants efficiently that are informative for the mapping of genes (see Chen et al. 1998). First, crossing-over is stimulated by the simultaneous presence of P elements and transposase (Hiraizumi 1971; Kidwell and Kidwell 1976). Second, by doing the experiment in Drosophila males, in which meiotic crossing-over does not occur, most of the crossover events are located at the P element (Preston et al. 1996). By controlling where the crossover event will be, each event is expected to be informative for mapping purposes (Fig. 2). Using this technique, mei-W68 was mapped relative to six P-element insertions (Table 1) and, all of the crossover events did appear to be at the P element. On the basis of the cytological positions of the six inserts, mei-W68 was localized to cytological interval 56D7–56D11 (Fig. 1); the closest proximal insert was P{lacW}l(2)k00705 (to be abbreviated 705) and the closest distal insert was P{lacW}l(2)k06323 (to be abbreviated 6323).

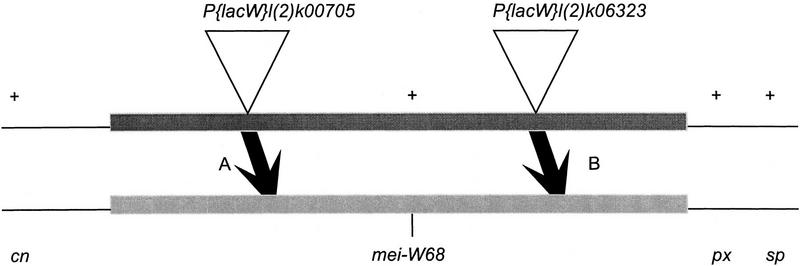

Figure 2.

The types of recombinants recovered from P element-mediated male crossing-over. This schematic map shows the markers used in most of the mapping experiments. It is not drawn to scale as the two insertions are much closer together relative to the flanking markers cn, px, and sp. If the P element was to the left (distal) of mei-W68, the + px sp crossovers (A) also carried the mei-W68 mutation. Conversely, if the insertion was to the right (proximal) of mei-W68, then the + px sp cross overs (B) did not carry the mei-W68 mutation. Shown is the direction of only one of the two crossover classes that was recovered from each experiment. Relative to the + px sp crossovers, the cn + + crossovers had the opposite linkage arrangement with mei-W68.

Table 1.

Mapping mei-W68 by P element-mediated male crossing-over

| Insertiona

|

cn+

|

+sp

|

Totalb

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Cross A | |||

| P{PZ}l(2)01103 | 7 (7/7 mei-W68−) | 10 (10/10 mei-W68+) | 3300 |

| P{PZ}l(2)05338 | 9 (9/9 mei-W68+) | 9 (9/9 mei-W68−) | 4100 |

| P{PZ}emm | 5 (2/2 mei-W68+) | 3 (2/2 mei-W68−) | 3300 |

| Cross B | |||

| P{lacW}l(2)k06323 | 1 (1/1 mei-W68−) | 3 (3/3 mei-W68+) | N.D. |

| P{lacW}l(2)k00705 | 1 (1/1 mei-W68+) | 2 (2/2 mei-W68−) | N.D. |

| P{lacW}l(2)k16914 | 1 (1/1 mei-W68+) | 4 (4/4 mei-W68−) | N.D. |

(Cross A) cn P{PZ} px sp/mei-W68 +; Δ2-3, Sb/ry males crossed to cn bw sp/SM6, cn sp; ry females. (Cross B) P{lacW} /cn mei-W68 px sp +; Δ2-3, Sb/ry males crossed to cn bw sp/SM6, cn sp; ry females.

(N.D.) Not determined.

We constructed yw/yw; 705 mei-W68 +/+ + 6323 females in an attempt to measure the genetic distance between the two inserts. No white− crossovers were recovered in ∼13,000 progeny. Thus, these two insertions were estimated to be <.02 cM apart. This result emphasizes the advantage of using transposase-induced male crossing-over to map genes. During female meiosis, a very large number of progeny would have had to have been screened to get a crossover within the small distance between one of the inserts and mei-W68.

Localization of mei-W68 to a region of genomic DNA containing a spo11 homolog

The region to which mei-W68 was mapped is covered by a contig of P1 clones, DS00433 (56D7–56E1), from the Drosophila Genome Project (Hartl et al. 1994; Kimmerly et al. 1996). We used inverse PCR to amplify the DNA adjacent to seven P-element insertions near mei-W68 (Materials and Methods). This DNA was labeled and used to probe Southern blots containing DNA from a series of P1 clones representing DS00433. In combination with the genetic mapping, these data showed that the mei-W68 coding region was located within the overlap of P1 clones DS07982 and DS00571 (Fig. 1). Our restriction map of the region shows the distance between the distal marker 6323 and the proximal marker 705 to be < 18 kb (Fig. 3). DS07982 has also been sequenced by the Drosophila Genome Project (AC004299; Berkeley Drosphila Genome Project, unpubl.) and the two maps are in agreement. Subsequent to this work, sequence from the insertion site of each P element was obtained by the genome project, which showed that the distance between 6323 and 705 is 12.3 kb. The sequence also revealed a candidate for mei-W68; an open reading frame (ORF) was identified in a BLAST search using the protein sequence of either spo11 from S. cerevisiae or its Caenorhabditis elegans homolog (see below).

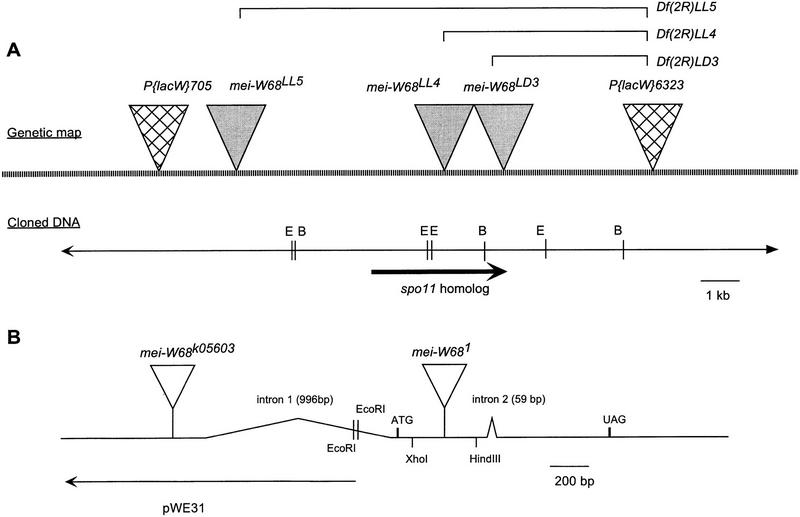

Figure 3.

Physical map of the mei-W68 region. (A) The restriction map came from two sources: our own restriction mapping of DS00571, and the Genome Project sequencing of the overlapping P1 DS07982. The molecular structures of three mei-W68 deletion mutants are shown. The brackets above the genetic map are to indicate that the LL4, LL5, and LD3 chromosomes are deletions with one endpoint at the original P{lacW}l(2)k06323 insertion site. (B) Depiction of the mei-W68 transcript showing the intron/exon structure and the location of the insertions in mei-W681 and mei-W68k05603. To show that the mei-W681 insertion was not in the first or second introns, we probed HindIII and XhoI digests with labeled EcoRI fragment pWE31 (B). The appearance of the larger insertion band in the HindIII digest and the wild-type bands in the XhoI digest (data not shown) showed that the insertion site was between the first and second introns. The position of the k05603 insertion was determined from sequence obtained by the genome project off the 5′ end of the P element (Berkeley Drosphila Genome Project).

Isolation and molecular analysis of mei-W68 mutants

We mobilized P-element insertions to induce new mutations of mei-W68 that would provide physical markers identifying the coding region. We hoped to isolate new insertion mutations of mei-W68 using closely linked P elements, which, in the presence of transposase, tend to move to new locations near the original site, so-called ‘local hops’ (Tower et al. 1993). Excision events were collected simultaneously, with the hope of isolating deletions that resulted from imprecise excision of the P element. Both types of events were screened for a failure to complement mei-W681.

Extensive experiments using either 705 or P{PZ}01103 (Fig. 1) failed to produce new mei-W68 mutants (see Materials and Methods). From the mobilization of the 6323 insertion we recovered 267 excision chromosomes, seven of which failed to complement mei-W68, and 216 local hop chromosomes, 11 of which failed to complement mei-W68. The excision events were assumed to be deletions because they failed to complement two loci, mei-W68 and the lethality of the parental 6323 chromosome. The phenotype of the local hops was surprising for two reasons. First, all 11 of the local hops were homozygous lethal and failed to complement the lethality of the parental 6323 chromosome and, therefore, were imprecise excisions of the 6323 element. Second, they had a strong nondisjunction phenotype in trans to mei-W681 (data not shown), which is unusual because P elements frequently cause weak mutations because they insert preferentially into promoter regions or introns.

Molecular analysis of three local-hop mutations showed that they were associated with deletions (Fig. 3). Inverse PCR was used to isolate the genomic DNA flanking the local-hop insertion sites. Probes were made from the DNA on either the 5′ or 3′ end of two mutants, local lighthop 4 (LL4) and LL5, and used to probe blots containing P1 clone-derived restriction fragments of the region. The probes from the 5′ end of each LL mutant hybridized to a new fragment, whereas the probes from the 3′ end hybridized to the original fragment that contained 6323. It is likely that in each case, the P element made a ‘half-jump’. The 5′ end (left in Fig. 3) excised and inserted at a new location within or on the other side of mei-W68, whereas the 3′ end (right in Fig. 3) did not excise and thus remained at the same site as 6323. This event resulted in the deletion of the intervening DNA. A third mutant, local darkhop 3 (LD3), was analyzed by Southern blot and probably is also a deletion. The half-jump model may be a general mechanism for P-element induced deletions because events of this nature have been recovered before (for review, see Preston et al. 1996). The molecular and genetic analysis shows that the local-hop mei-W68 mutants are deletions, and their lethal phenotype can be explained by mutation of the 6323 locus. The mei-W681/Df females were as viable and fertile as the mei-W681/mei-W681 females. Thus, there is no evidence that the mei-W68 gene product is required for normal viability.

The above analysis showed that three mei-W68 deletions also affected the spo11 homolog, consistent with the idea that it is the mei-W68 gene (Fig. 3). For direct evidence we analyzed the spo11-coding region of the strong mei-W681 mutant. Southern blot and PCR analysis has shown that there is a ∼5 kb insertion within the second exon of the mei-W68 transcript (Fig. 3B). The Drosophila Genome Project has also isolated a P-element insertion allele of mei-W68, known previously as P{lacW}l(2)k05603, that is inserted in the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) of mei-W68 (Fig. 3B). Whereas this mutant was classified originally as a lethal, we found the P-element insertion homozygotes to be viable. We have renamed this mutation mei-W68k05603 because it fails to complement the X chromosome nondisjunction phenotype of mei-W681 and Df(2R)LL5. The analysis of mei-W681 and mei-W68k05603 demonstrates that mei-W68 encodes an Spo11 homolog.

cDNA and protein sequence

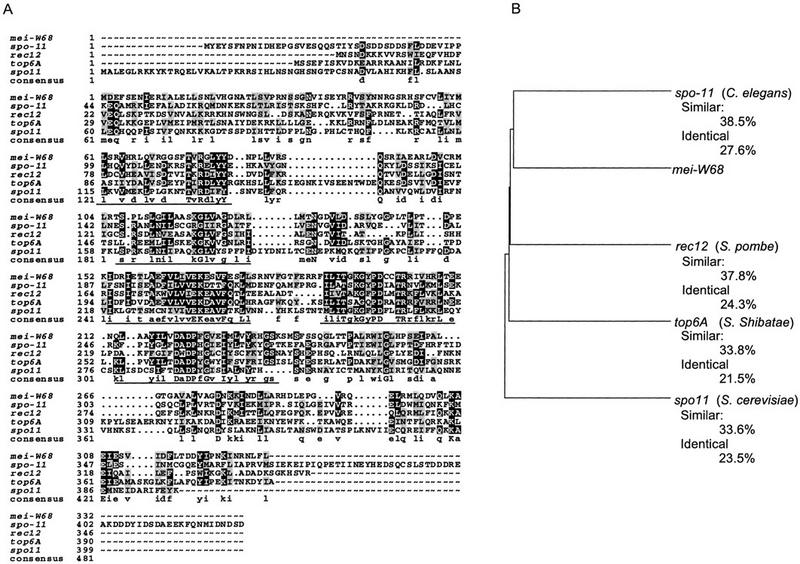

Several clones were isolated from a germarium cDNA library (see Fig. 5, below) using a genomic fragment containing the spo11 homolog as a probe (see Materials and Methods). The largest clones were 2.3 kb and most likely full length because they had a similar size to the predominant transcript seen on a Northern blot (see below and Fig. 3B). An unusual feature of the transcript is the relatively large first intron (996 bp) just before the predicted initiator methionine codon. The transcript also has a large 5′ UTR (861 bp), which suggests that mei-W68 might be regulated at the translational level. The multiple sequence alignment of the predicted mei-W68 protein to other spo11 homologs (Fig. 4) shows that the nematode and fly genes have the least divergence, whereas the S. cerevisiae gene is the most diverged. In describing this gene family, Bergerat et al. (1997) defined five homologous domains, and mei-W68 has high similarity in all of them. In the first domain, mei-W68 has the tyrosine (position 81) which is believed to make a covalent bond to DNA. All of the homologs except spo11 have two tyrosines at this position. Nonetheless, the overall similarity of the proteins is quite low (21%–28% identity, 34%–38% similarity; Fig. 4B).

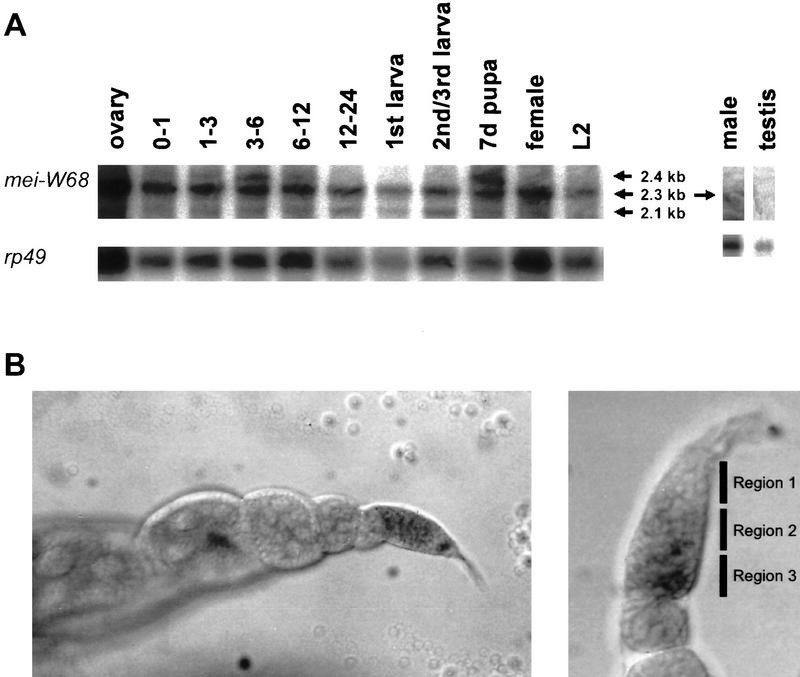

Figure 5.

Developmental Northern blot using a mei-W68 antisense RNA probe. The ribosomal protein gene RP49 was used as a standard for the amount of mRNA loaded on the gel. (A) There are three transcripts of 2.4, 2.3, and 2.1 kb. The 2.3-kb transcript is seen through all developmental stages. The largest transcript (2.4 kb) is detected in the first 12 hr of embryogenesis and in the pupal stage. The 2.1-kb transcript is seen in all stages but is clear at 12–24 hr embryo stage and larval stages. A transcript was difficult to detect in males but was detected by RT–PCR (see text). The numbers for lanes 2–6 indicate the hours of embryonic development. (7d) The pupal stage at day 7 of development. (B) Two examples of an in situ hybridization to whole ovaries using an RNA probe made from the mei-W68 full-length cDNA. (Left) The transcript was detectable in the latter half of the germarium, which corresponds to regions 2 and 3, but there was little or no transcript was detectable in later stages. (Right) Another germarium at higher magnification. The transcript was not detected in region 1, where the premeiotic mitotic divisions occur.

Figure 4.

mei-W68 is a homolog of spo11 and the topo6A type II topoisomerase. (A) Protein sequence alignment spo11 homologs from S. cerevisiae Spo11 (Atcheson et al. 1987), Schizosaccharomyces pombe Rec12 (Lin and Smith 1994), Sulfolobus shibatae topo6A (Bergerat et al. 1997), and the predicted C. elegans gene from cosmid T05E11.4 (Wilson et al. 1994; Dernburg et al. 1998). (B) Dendogram comparing the extent of similarity between the different proteins. The percentages of similar and identical amino acids are relative to MEI-W68.

mei-W68 is expressed in a variety of tissues and developmental stages

The mei-W68 transcript is expressed in a variety of developmental stages, including embryos, larvae, and pupae (Fig. 5A). In all stages two transcripts are visible. There is a predominant 2.3-kb transcript, which is consistent with the size of the cDNA clones, and also a smaller 2.1-kb transcript. There is also a larger 2.4-kb transcript in embryos and pupae. The function and structure of the 2.1- and 2.4-kb transcripts are not known. The presence of the 2.3-kb transcript in most developmental stages suggests that mei-W68 has a function in somatic cells. The transcript was difficult to detect in males on a Northern blot, but RT–PCR experiments confirmed that mei-W68 is transcribed in the testis at a low level (data not shown and P.J. Romanienko, B. Oliver, and R.D. Camerini-Otero, pers. comm.). The difference in mei-W68 RNA levels between males and females can be attributed to the relatively high level of expression in the ovaries. Thus, there is little or no transcript in adult somatic tissue. For the ovary, we also used in situ hybridization and detected the mei-W68 transcript at a low level in the germarium, which is where meiotic prophase occurs. It was not detected in later stages of ovary development (Fig. 5B).

Discussion

mei-W68 encodes a topoisomerase II-like protein homologous to Spo11

mei-W68 is required for all meiotic recombination but not for normal synaptonemal complex between homologs (McKim et al. 1998). Whereas the simplest hypothesis is that mei-W68 is required for initiating meiotic recombination, supporting molecular evidence has been lacking as the gene was not cloned. Here we have shown that the MEI-W68 protein has sequence homology to Spo11 from S. cerevisiae. Like mei-W68, in spo11 mutants both gene conversion and crossing over are eliminated (Cao et al. 1990; McKim et al. 1998). In addition, spo11 is required for meiotic double-strand break formation in S. cerevisiae. In Drosophila, therefore, it is likely that double-strand breaks are the event that initiate meiotic recombination, and that mei-W68 has a vital role in their generation. The connection is further strengthened by two observations that support the hypothesis that Spo11 is the enzymatic factor that makes double-strand breaks. First, the predicted amino acid sequence of Spo11 shows that it is a member of a new family of proteins with sequence similarity to the topo6A gene product from the archaea Sulfolobus shibatae (Bergerat et al. 1997). In S. shibatae, a dimer consisting of topo6A and topo6B is a novel type II topoisomerase (Bergerat et al. 1994). Second, several authors found that a protein is linked covalently to unprocessed double-strand breaks from meiotic cells of yeast rad50S mutants (de Massy et al. 1995; Keeney and Kleckner 1995; Liu et al. 1995; Bergerat et al. 1997). Keeney et al. (1997) identified this protein as Spo11. Whereas the suggestion is that Spo11 is a type II topoisomerase, it should be emphasized that the biochemical activity of Spo11 has yet to be described. If Spo11 makes the meiotic double-strand break, then it does not act strictly as a type II topoisomerase because the double-strand break is not rejoined.

Further experiments will be required to determine whether processing of the double-strand break differs in yeast and flies. The generation of crossovers requires different genes in these two organisms. Two genes in Drosophila, mei-9, and mei-218, that are required for 95% of crossing-over (but not gene conversion) have been cloned. The mei-9 gene is a homolog of RAD1 from S. cerevisiae (Sekelsky et al. 1995). Surprisingly, RAD1 is not required for meiotic crossing over. A homolog of the Drosophila mei-218 gene is not found in the S. cerevisiae genome (McKim et al. 1996).

Meiotic chromosome pairing and synapsis without double-strand breaks

The similar sequence and phenotypes of spo11 and mei-W68 suggests that they play analogous roles in the generation of meiotic double-strand breaks. On the other hand, spo11 and mei-W68 mutants have different effects on synaptonemal complex formation. Meiotic recombination is eliminated in mei-W68 homozygotes, but normal synaptonemal complex forms between the homologs (McKim et al. 1998). In S. cerevisiae, however, spo11 and other similar rec− mutants do not form synaptonemal complex (see Klapholz et al. 1985; Giroux et al. 1989; for review, see Roeder 1997), and analysis of the zip1 mutant lent support to a model in which synaptonemal complex formation initiates at the sites of meiotic recombination events (Rockmill et al. 1995). The difference in flies, therefore, is that synaptonemal complex can form in the absence of meiotic recombination. With the finding that mei-W68 is a spo11 homolog, the most likely scenario for Drosophila meiosis is that double-strand breaks initiate meiotic recombination, but they are not needed for the homologs to form synaptonemal complex. These results confirm our earlier conclusion (McKim et al. 1998) that yeast and Drosophila have different controls on synaptonemal complex formation. Furthermore, the phenotype of mutants in the C. elegans spo11 homolog is almost identical to mei-W68 with respect to meiotic recombination and synaptonemal complex formation (Dernburg et al. 1998). Thus, our conclusions concerning the relationship of double-strand breaks to meiotic recombination and synaptonemal complex formation may apply to a variety of metazoans.

Pairing between homologs prior to the initiation of recombination has been implied in studies involving a variety of organisms. Presynaptic alignment, which is when homologs pair at a distance prior to synaptonemal complex formation, probably occurs before the initiation of meiotic recombination (Giroux 1988; Loidl 1990). In S. cerevisiae, there is significant alignment or pairing of homologs prior to double-strand break formation (Weiner and Kleckner 1994), as well as in mutants that fail to make double-strand breaks (Loidl et al. 1994; Nag et al. 1995). The mechanisms for presynaptic alignment of homologs are understood poorly, but there are various models that fall into two major types. First, specialized regions, or pairing sites, could mediate homolog pairing (Hawley 1980; McKim et al. 1993; Zetka and Rose 1995). Second, a homology search could involve unstable interactions between intact DNA molecules (Weiner and Kleckner 1994; Kleckner 1996). The two models are not, however, mutually exclusive, since the pairing sites might be specialized regions of the chromosome that are capable of interacting at the DNA level without breaks. These models can account for the observations of synaptonemal complex formation without double-strand breaks in Drosophila and C. elegans. Perhaps the main difference between yeast and the metazoans is the extent to which double-strand break independent pairing can stimulate synaptonemal complex between homologs.

MEI-W68 has a somatic function

S. cerevisiae spo11 is expressed only during meiosis (Atcheson et al. 1987; but see Bruschi and Esposito 1983), but mei-W68 has a role in somatic cells. Baker et al. (1978) found that in mei-W68 mutants the frequency of somatic clones in the abdomen (but not in the wing) was increased three times over wild type. Most of this increase was attributed to an increase in mitotic recombination. The unusual features of the clones, however, such as their tissue specificity and large size, caused these investigators to suggest that the majority of mei-W68-induced clones occurred in nondividing cells. Similarly, Lutken and Baker (1979) showed that mitotic crossing-over in the germ-line of mei-W68 males was increased 10 times over wild type (there is no meiotic crossing-over in Drosophila males). Finally, and as predicted by the genetic studies, we have found that the mei-W68 transcript is expressed in many somatic cell types. mei-W68 is even found at a low level in male testis, in which meiotic recombination does not normally occur. Whereas it is possible that mei-W68 may be required for an aspect of DNA repair, we do not favor this hypothesis because mei-W68 mutants are not mutagen sensitive (K.S. McKim, unpubl.). Unfortunately, our limited understanding of mei-W68 function does not allow us to resolve the paradox that during meiosis the mutant eliminates recombination, whereas in mitosis it increases recombination. A similar situation occurs in two S. cerevisiae genes, RAD50 and XRS2. Mutations in these two genes eliminate all meiotic recombination, yet have a hyper-recombination phenotype in mitotic cells (Malone et al. 1990; Ivanov et al. 1992).

These data have the implication that many eukaryotes may have two type II topoisomerase enzymes. In addition to the MEI-W68 enzyme, Drosophila has a typical type II topoisomerase enzyme (Heller et al. 1986; Whalen et al. 1991). The meiotic-specificity of Spo11 suggests that metazoans might have a requirement for these proteins that is not present in yeast. A problem with this interpretation is the uncertainty regarding the biochemical activity of the Spo11-like proteins. During meiosis, Spo11 does not act like a type II topoisomerase since the double-strand breaks are not resealed. Thus, the eukaryotic Spo11 proteins may have lost the second part of the typical type II function. In this case, during mitosis MEI-W68 might behave as an endonuclease, a function consistent with a role in DNA repair (see above). Having only part of the type II enzymatic activity could be caused by the absence in all of the Spo11 homologs of an ATPase domain. Canonical type II enzymes lacking their ATPase domain can still cut DNA, but the other activities are compromised (Berger et al. 1996). In S. shibatae the topo6B protein contains the ATPase domain, but so far no subunit that interacts with a eukaryotic Spo11 has been identified.

As topoisomerase activity of top6A is dependent on a subunit, the activity of MEI-W68 could be altered in meiosis and mitosis by interacting with different sets of proteins. In S. cerevisiae and Drosophila, several gene products are required for creating double-strand breaks. For example, nine yeast genes have been identified that are required for double-strand break formation, six of which are meiosis specific, including spo11 (Roeder 1995). In Drosophila, the mei-P22 gene has the same mutant phenotype as mei-W68 and is therefore also required for the initiation of meiotic recombination and likely for the generation of double-strand breaks (McKim et al. 1998). During meiosis, several proteins, including MEI-P22, might interact with MEI-W68 to prevent it from sealing the double-strand break. In mitosis, however, a different set of interacting proteins would allow MEI-W68 to have a more typical type II activity.

Materials and methods

Genetic techniques

All crosses were carried out at 25°C. Some stocks used in this study were received from the Bloomington Stock Center or Todd Laverty of the Drosophila Genome Project at the University of California at Berkley. The P-element insertion lines used in this study are described by Spradling et al. (1995). There were two alleles of mei-W68 isolated prior to this study (Lindsley and Zimm 1992). The first allele is mei-W681, which is a strong allele showing 38.7% X chromosome nondisjunction (McKim et al. 1998). The second allele is mei-W68L1, which is weaker and has only 3.6% X chromosome nondisjunction (K.S. McKim, unpubl.). mei-W681 appeared during a screen for X-linked meiotic mutants (A.T.C. Carpenter and B.S. Baker, pers. comm.; Baker and Carpenter 1972). Because in that screen the mutagenized second chromosomes were eliminated in the crosses to isolate the X-linked mutants, mei-W681 was not ethyl methane sulfonate (EMS) induced but arose spontaneously. The mei-W68k05603 allele was identified because sequence off the end of the P element (Berkeley Drosphila Genome Project, unpubl.) showed that it was inserted into the 5′ UTR.

mei-W68 was mapped originally to genetic position 94, which corresponds to cytological position 57B (Lindsley and Zimm 1992). None of the available deficiencies in the region failed to complement mei-W68. These deficiencies covered the entire division 57, making it likely that mei-W68 was in division 56 or 58. We mapped mei-W68 to division 56 in a standard three-factor mapping experiment using a P-element insertion at 56C1-2 P{PZ}l(2)02029} and the px mutation at 58F (Fig. 1). From cn P{PZ}l(2)02029 + px sp/+ + mei-W68 ++; ry females, 23 ry px sp crossovers and 85 ry+ px+ sp+ crossovers were picked and tested for the mei-W68 phenotype of elevated X-chromosome nondisjunction: 21 of the ry px sp crossovers were mei-W68 and two were mei-W68+, 80 of the ry+ px+ sp+ crossovers were mei-W68+, and 5 were mei-W68. These data placed mei-W68 close to the right of P{PZ}l(2)02029.

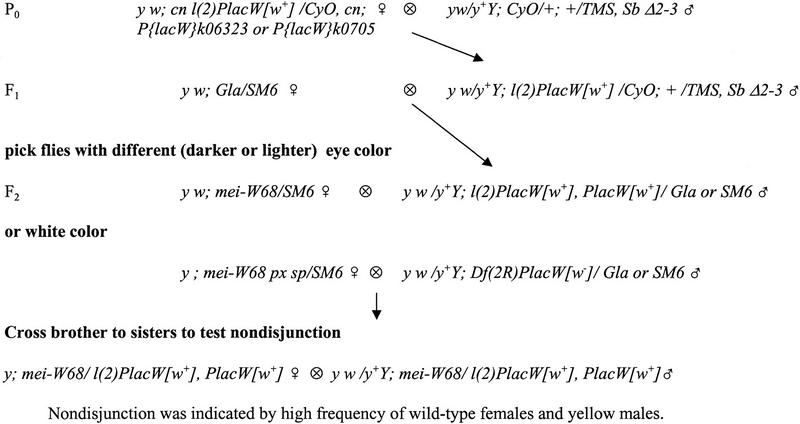

The mei-W68 nondisjunction phenotype was assayed by crossing females to C(1;Y), v f B; C(4)RM, eyR ci males. From this cross, the regular progeny were Bar females and wild-type males. Progeny resulting from X chromosome nondisjunction in the mother appeared as wild-type females and Bar males. Alternatively (i.e., the screen for mei-W68 mutations; Fig. 6), X-chromosome disjunction was tested in the cross of y/y females to y/y+Y males. The regular progeny were yellow females and wild-type males, whereas the nondisjunctional progeny were wild-type females and yellow males.

Figure 6.

Genetic crosses to generate P element-induced local-hop insertions and deletions of the mei-W68 gene. CyO and SM6 are second chromosome balancers carrying the dominant Cy maker; TMS is a third chromosome balancer carrying the source of P-element transposase, Δ2-3 and the dominant Sb marker. In the F1 generation, the P elements are exposed to transposase, and any mobilization events are detected in the F2 by a change in eye color. These exceptional flies were picked and mated separately to establish stocks and test for nondisjunction (Materials and Methods).

When mapping mei-W68 relative to P-element insertions, the crosses to generate P element-induced crossovers are shown in Table 1. To generate these males, y w/ y+Y; mei-W68/CyO; Δ2-3, Sb/+ males were crossed to yw; P{lacW}/CyO or y; P{PZ}/CyO females. The recombinant males were crossed to mei-W68/SM6 females and the recombinant/mei-W68 female progeny were then tested for nondisjunction by one of the crosses described above.

Insertion mutations by local hopping were isolated by picking second chromosomes carrying a P{lacW} insertion that expressed a different eye color than the original chromosome (Fig. 6). The new insertions can be distinguished from the original element by a change in eye color because expression of w+ is very sensitive to dosage and position effects. Stocks expressing less eye pigment were referred to as LL, whereas stocks expressing more eye pigment were referred to as LD. LL mutants were expected to be cases in which there was both an insertion and precise excision of the original P element. LD mutants could also have been from this type of event, but they could also have arisen from a case in which the new insertion and original P element were present. In the same screen we isolated excision events by picking second chromosomes lacking the P{lacW} insertion, that is flies with white eye color. Whereas mobilization of 6323 produced new mei-W68 mutants (see Results), similar attempts with the two elements to the left of mei-W68 failed to yield mutants. We screened 73 excision and 47 local hop chromosomes of 705 and none failed to complement mei-W68. We screened 250 excision chromosomes of P{PZ}l(2)01103 (Fig. 1), but none failed to complement mei-W68. This failure was not caused by a haploinsufficient locus between 705 and mei-W68. Df(2R)LL5 fails to complement both 705 and 6323, and thus spans the region between them, but has excellent viability as a heterozygote. Another possibility is that deletions induced by P-element activity might be directional, and in the case of 705 and 1103 any deletions that were induced went in the wrong direction.

Genomic DNA cloning

Standard molecular techniques were as described previously (Sambrook et al. 1989). The source of the cloned genomic DNA was from a contig of P1 clones, DS00433, mapped previously to the mei-W68 region (56D7–56E1) (Hartl et al. 1994; Kimmerly et al. 1996). We used inverse PCR to amplify the DNA adjacent to seven P-element insertions in the region. In addition, the genome project had established already that the P{PZ}l(2)01103 insertion site anchored the left end of DS00433 to the cytological (56D5–6) and genetic maps. Probes from l(2)01103, l(2)k00705, l(2)k16914, and l(2)k06323 each hybridized to the same two P1 clones, DS07982 and DS00571. Probes from l(2)k09810, emm, and l(2)05338 did not hybridize; thus, these insertions were farther away from mei-W68. The P1 clone DS00571 was restriction mapped in two steps. First, we subcloned most of the EcoRI, BamHI, and PstI fragments. Second, restriction and Southern blot analysis was used to order the subclones. Southern blots of genomic and clone DNA were probed with random prime labeled DNA using nonradioactive protocols from the Boeringher Mannheim Genius system.

Genomic DNA flanking a P-element insertion was obtained by inverse PCR. Genomic DNA was isolated from stocks carrying a P-element insertion and digested with either HinPI or MspI. Approximately three flies worth was added to a 100-ul ligation reaction. This reaction was precipitated and dissolved in 20 ul of 10 mm Tris (pH 8.0). For the PCR reaction, 2.5 μl of this was used as a template in a 25-ul reaction containing 2 mm NTPs, 50 pm each primer, 5% glycerol, 2.5 mm MgCl2, 2 units of Taq, and 1× Perkin-Elmer PCR buffer. The typical PCR conditions were 1 min at 95°C, 1 min at 55°C, and 2 min at 72°C for 30–35 cycles. The products were run on a 1.5% agarose gel and the bands cut out of the gel. In some cases the amplification was poor, so the excised band was amplified again in a second round of PCR. The DNA extracted from the gel slices was labeled for Southern hybridization.

Isolation of cDNA clones and DNA sequencing

We found initially the Spo11 homolog in a search of the genomic DNA sequence from the Berkely Drosophila Genome Project (clone DS07982). To isolate cDNA clones, we used PCR to amplify 0.5-kb and 0.7-kb fragments using the primer pairs AH36–AH38 and AH37–AH39, respectively, and as template a germanium cDNA library in the Lambda ZapII vector (gift of D. Thompson-Stewart, Carnegie Institute of Washington). The PCR products were digested and cloned into Bluescript SK+. The plasmid pAH68 contains 1.0 kb of mei-W68-coding region and was made by ligating together the 0.5- and 0.7-kb PCR products at an internal BamHI site. The PCR primers used were 5′-GACTAGTCATGGATGAATTTTCGGAG-3′ (AH36), 5′-AGGCCTTCTACAAAAACAAGTTCCG-3′(AH37), 5′-TCTTCTCGGGATCCGTGG-3′(AH38), and 5′-TCCCCCCTAAGCTTGGGC-3′ (AH39). The 0.7-kb PCR fragment was used to screen the cDNA library. A total of 19 positive clones were isolated from screening 5 × 105 phage. The cDNA phage clones were converted to plasmids by the Exassist/SOLR excision system (Stratagene) and then three of the clones were sequenced by Research Genetics. pAH69 is one of these clones and contains a putative full-length (2.3 kb) cDNA. The sequence was analyzed using the GCG package (Devereux et al. 1984) or DNA Strider. Genbank database searches were done with the BLAST program (Altschul et al. 1990).

Northern blot hybridization and in situ hybridization to ovaries

RNA was isolated as described previously (Kerrebrock et al. 1995). The poly(A)+ RNA from several developmental stages was loaded on an agarose gel and transferred to Hybond-N(Amasham). After UV cross-linking, the membrane was hybridized using an antisense RNA probe generated by digesting pAH68 with SpeI and was using it as a template for [32P]CTP-labeled transcripts synthesized by T7 RNA polymerase. A probe for the ribosomal protein RP49 transcript (O’Connell and Rosbash 1984) was used as loading control.

Ovaries were dissected, fixed, and hybridized as described previously (Tautz and Pfeifle 1989). DIG-labeled RNA probes were made from linearized pAH69 using the Boehringer Mannheim RNA-labeling kit.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Abby Dernburg for pointing out initially that mei-W68 could be a spo11 homolog, to A.T.C. Carpenter, Terry Orr-Weaver, Jeff Sekelsky, and Scott Hawley for insightful discussions and comments on the manuscript, and to Scott Keeney for technical assistance. We also thank Jim Graham and Janet Jang for technical support and critical reading of the manuscript. Part of this work was conducted in the laboratory of Terry Orr-Weaver. Work in the laboratory of K.M. was supported by grant MCB-9723330 from the National Science Foundation. The GenBank accession no. for the cDNA sequence of mei-W68 is AF085276.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked ‘advertisement’ in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL mckim@rci.rutgers.edu; FAX (732) 445-5735.

References

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Meyers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atcheson CL, DiDomenico B, Frackman S, Esposito RE, Elder RT. Isolation, DNA sequence, and regulation of a meiosis-specific eukaryotic recombination gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1987;84:8035–8039. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.22.8035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker BS, Carpenter ATC. Genetic analysis of sex chromosomal meiotic mutants in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1972;71:255–286. doi: 10.1093/genetics/71.2.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker BS, Carpenter ATC, Ripoll P. The utilization during mitotic cell division of loci controlling meiotic recombination in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1978;90:531–578. doi: 10.1093/genetics/90.3.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger JM, Gamblin SJ, Harrison SC, Wang JC. Structure and mechanism of DNA topoisomerase II. Nature. 1996;379:225–232. doi: 10.1038/379225a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergerat A, Gadelle D, Forterre P. Purification of DNA topoisomerase II from the hyperthermophilic archeon Sulfobolus shibatae. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:27663–27669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergerat A, de Massy B, Gadelle D, Varoutas P, Nicolas A, Forterre P. An atypical topoisomerase II from archaea with implications for meiotic recombination. Nature. 1997;386:414–417. doi: 10.1038/386414a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruschi CV, Esposito MS. Enhancement of spontaneous mitotic recombination by the meiotic mutant spo11-1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1983;80:7566–7570. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.24.7566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao L, Alani E, Kleckner N. A pathway for generation and processing of double-strand breaks during meiotic recombination in S. cerevisiae. Cell. 1990;61:1089–1101. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90072-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter ATC. Meiotic roles of crossing-over and of gene conversion. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1984;49:23–29. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1984.049.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter ATC. Gene conversion, recombination nodules, and the initiation of meiotic synapsis. BioEssays. 1987;6:232–236. doi: 10.1002/bies.950060510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Chu T, Harms E, Gergen JP, Strickland S. Mapping of Drosophila mutations using site-specific male recombination. Genetics. 1998;149:157–163. doi: 10.1093/genetics/149.1.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Massy B, Rocco V, Nicolas A. The nucleotide mapping of DNA double-strand breaks at the CYS3 initiation site of meiotic recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1995;14:4589–4598. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00138.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dernburg AF, McDonald K, Moulder G, Barstead R, Dresser M, Villeneuve AM. Meiotic recombination in C. elegans initiates by a conserved mechanism and is dispensable for homologous chromosome synapsis. Cell. 1998;94:387–398. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81481-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devereux J, Haeberli P, Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giroux CN. Chromosome synapsis and meiotic recombination. In: Kucherlapati R, Smith G, editors. Genetic recombination. Washington, D.C.: American Society of Microbiology; 1988. pp. 465–496. [Google Scholar]

- Giroux CN, Dresser ME, Tiano HF. Genetic control of chromosome synapsis in yeast meiosis. Genome. 1989;31:88–94. doi: 10.1139/g89-017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartl DL, Nurminsky DI, Jones RW, Lozovskaya ER. Genome structure and evolution in Drosophila: Applications of the framework P1 map. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1994;91:6824–6829. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.6824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley RS. Chromosomal sites necessary for normal levels of meiotic recombination in Drosophila melanogaster. I. Evidence for and mapping of the sites. Genetics. 1980;94:625–646. doi: 10.1093/genetics/94.3.625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley RS. Exchange and chromosomal segregation in eucaryotes. In: Kucherlapati R, Smith G, editors. Genetic recombination. Washington, D.C.: American Society of Microbiology; 1988. pp. 497–527. [Google Scholar]

- Heller RA, Shelton ER, Dietrich V, Elgin SCR, Brutlag DL. Multiple forms and cellular localization of Drosophila topoisomerase II. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:8063–8069. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilliker AJ, Clark SH, Chovnick A. Genetic analysis of intragenic recombination in Drosophila. In: Low KB, editor. The recombination of genetic material. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1988. pp. 73–90. [Google Scholar]

- Hiraizumi Y. Spontaneous recombination in Drosophila melanogaster males. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1971;68:268–270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.2.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov EL, Korolev VG, Fabre F. XRS2, a DNA repair gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, is needed for meiotic recombination. Genetics. 1992;132:651–664. doi: 10.1093/genetics/132.3.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeney S, Kleckner N. Covalent protein–DNA complexes at the 5′ strand termini of meiosis-specific double-strand breaks in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1995;92:11274–11278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.11274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeney S, Giroux CN, Kleckner N. Meiosis-specific DNA double-strand breaks are catalyzed by Spo11, a member of a widely conserved protein family. Cell. 1997;88:375–384. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81876-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerrebrock AW, Moore DP, Wu JS, Orr-Weaver TL. Mei-S332, a Drosophila protein required for sister-chromatid cohesion, can localize to meiotic centromere regions. Cell. 1995;83:247–256. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90166-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidwell MG, Kidwell JF. Selection for male recombination in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1976;84:333–351. doi: 10.1093/genetics/84.2.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmerly W, Stultz K, Lewis S, Lewis K, Lustre V, Shirley R, Martin C. A P1-based physical map of the Drosophila euchromatic genome. Genome Res. 1996;6:414–430. doi: 10.1101/gr.6.5.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klapholz S, Waddell CS, Esposito RE. The role of the SPO11 gene in meiotic recombination in yeast. Genetics. 1985;110:187–216. doi: 10.1093/genetics/110.2.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleckner N. Meiosis: How could it work? Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1996;93:8167–8174. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lage PZ, Shrimpton AD, Flavell AJ, MacKay TFC, Leigh Brown AJ. Genetic and molecular analysis of smooth, a quantitative trait locus affecting bristle number in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1997;146:607–618. doi: 10.1093/genetics/146.2.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichten M, Goldman A. Meiotic recombination hotspots. Annu Rev Genet. 1995;29:423–444. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.29.120195.002231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, Smith GR. Transient, meiosis induced expression of the rec6 and rec12 genes of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genetics. 1994;136:769–779. doi: 10.1093/genetics/136.3.769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsley DL, Zimm GG. The genome of Drosophila melanogaster. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Wu T, Lichten M. The location and structure or double-strand DNA breaks induced during yeast meiosis: Evidence for a covalently linked DNA–protein intermediate. EMBO J. 1995;14:4599–4608. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00139.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loidl J. The initiation of meiotic chromosome pairing:The cytological view. Genome. 1990;33:759–778. doi: 10.1139/g90-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loidl J, Klein F, Scherthan H. Homologous pairing is reduced but not abolished in asynaptic mutants in yeast. J Cell Biol. 1994;125:1191–1200. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.6.1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutken T, Baker BS. The effects of recombination defective meiotic mutants in Drosophila melanogaster on gonial recombination in males. Mut Res. 1979;61:221–227. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(79)90129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone RE, Ward T, Lin S, Waring J. The RAD50 gene, a member of the double strand break repair epistasis group, is not required for spontaneous mitotic recombination in yeast. Curr Genet. 1990;18:111–116. doi: 10.1007/BF00312598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKim KS, Peters K, Rose AM. Two types of sites required for meiotic chromosome pairing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1993;134:749–768. doi: 10.1093/genetics/134.3.749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKim KS, Dahmus JB, Hawley RS. Cloning of the Drosophila melanogaster meiotic recombination gene mei-218: A genetic and molecular analysis of interval 15E. Genetics. 1996;144:215–228. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.1.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKim KS, Green-Marroquin BL, Sekelsky JJ, Chin G, Steinberg C, Khodosh R, Hawley RS. Meiotic synapsis in the absence of recombination. Science. 1998;279:876–878. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5352.876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meselson M, Radding CM. A general model for genetic recombination. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1975;72:358–261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.1.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nag DK, Scherthan H, Rockmill B, Bhargava J, Roeder GS. Heteroduplex DNA formation and homolog pairing in yeast meiotic mutants. Genetics. 1995;141:75–86. doi: 10.1093/genetics/141.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell PO, Rosbash M. Sequence, structure, and codon preference of the Drosophila ribosomal protein 49 gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:5495–5513. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.13.5495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston CR, Sved JA, Engels WR. Flanking duplications and deletions associated with P-induced male recombination in Drosophila. Genetics. 1996;144:1623–1638. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.4.1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockmill B, Sym M, Scherthan H, Roeder GS. Roles for two RecA homologs in promoting chromosome synapsis. Genes & Dev. 1995;9:2684–2695. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.21.2684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeder GS. Sex and the single cell: Meiosis in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1995;92:10450–10456. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeder GS. Meiotic chromosomes: It takes two to tango. Genes & Dev. 1997;11:2600–2621. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.20.2600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: A laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Schwacha A, Kleckner N. Identification of double Holliday junctions as intermediates in meiotic recombination. Cell. 1995;83:783–791. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90191-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekelsky JJ, McKim KS, Chin GM, Hawley RS. The Drosophila meiotic recombination gene mei-9 encodes a homologue of the yeast excision repair protein Rad1. Genetics. 1995;141:619–627. doi: 10.1093/genetics/141.2.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spradling AC, Stern DM, Kiss I, Roote J, Laverty T, Rubin GM. Gene disruptions using P transposable elements: An integral component of the Drosophila genome project. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1995;92:10824–10830. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.10824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szostak JW, Orr-Weaver TL, Rothstein RJ, Stahl FW. The double-strand-break repair model for recombination. Cell. 1983;33:25–35. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90331-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tautz D, Pfeifle C. A non-radioactive in situ hybridization method for the localization of specific RNAs in Drosophila embryos reveals translational control of the segmentation gene hunchback. Chromosoma. 1989;98:81–85. doi: 10.1007/BF00291041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tower J, Karpen GH, Craig NL, Spradling AC. Preferential transposition of Drosophila P elements to nearby chromosomal sites. Genetics. 1993;133:347–359. doi: 10.1093/genetics/133.2.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner B, Kleckner N. Chromosome pairing via multiple interstitial interactions before and during meiosis yeast. Cell. 1994;77:977–991. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90438-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whalen AM, McConnell M, Fisher PA. Developmental regulation of Drosophila DNA topoisomerase II. J Cell Biol. 1991;112:203–213. doi: 10.1083/jcb.112.2.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson R, Ainscough R, Anderson KV, Baynes C, Berks M, Bonfield J, Burton J, Connell M, Copsey T, Cooper J, et al. 2.2 Mb of contiguous nucleotide sequence from chromosome III of C. elegans. Nature. 1994;368:32–38. doi: 10.1038/368032a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T-C, Lichten M. Meiosis-induced double-strand break sites determined by yeast chromatin structure. Science. 1994;263:515–518. doi: 10.1126/science.8290959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zetka M, Rose A. The genetics of meiosis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Trends Genet. 1995;11:27–31. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)88983-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]