Abstract

The Patient Informatics Consult Service (PICS) at the Eskind Biomedical Library at Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC) provides patients with consumer-friendly information by using an information prescription mechanism. Clinicians refer patients to the PICS by completing the prescription and noting the patient's condition and any relevant factors. In response, PICS librarians critically appraise and summarize consumer-friendly materials into a targeted information report. Copies of the report are given to both patient and clinician, thus facilitating doctor-patient communication and closing the clinician-librarian feedback loop. Moreover, the prescription form also circumvents many of the usual barriers for patients in locating information, namely, patients' unfamiliarity with medical terminology and lack of knowledge of authoritative sources. PICS librarians capture the time and expertise put into these reports by creating Web-based pathfinders on prescription topics. Pathfinders contain librarian-created disease overviews and links to authoritative resources and seek to minimize the consumer's exposure to unreliable information. Pathfinders also adhere to strict guidelines that act as a model for locating, appraising, and summarizing information for consumers. These mechanisms—the information prescription, research reports, and pathfinders—serve as steps toward the long-term goal of full integration of consumer health information into patient care at VUMC.

INTRODUCTION

Patients who are well informed about their medical conditions and treatment plans fare better than those who are not. The literature suggests that knowledge-empowered patients are able to participate in health care decisions and in their own treatment, thereby improving their health outcome. Greenfield et al. [1] and Beisecker and Beisecker [2], for example, find that diabetic patients with active involvement in decisions regarding their medical treatment demonstrate improved control of their conditions.

Health care practitioners also benefit from having well-informed patients. Notkin [3] suggests that when patients are provided with information about their care and treatment, physicians' tort liability may be limited, because many malpractice suits arise due to patients' misunderstanding of recommended courses of treatment. In a survey of cost-benefit studies for patient education in managed care and other settings, Bartlett reports that an average of three to four dollars is saved for each dollar spent on patient education [4]. Savings are attributed to the confidence with which patients manage their own symptoms, thereby experiencing complications or exacerbations less frequently.

Recognition of the benefits that accrue when consumers are well informed about their medical care, as well as the increasing public interest in health care information, has prompted the development of patient- or consumer-oriented health information centers throughout the United States. Hospitals are forming resource centers for their patients; medical centers are opening their libraries' doors to patients [5, 6]; and consumer health organizations are developing health resource centers [7].

In addition to physical centers for health information, the quantity of health information available and the number of people accessing it via the Web has exploded. Tyson, for example, notes that eighteen million adults used the Web in 1998 to search for medical information [8]. Web-based information stems from a wide variety of sources, including not only academic medical centers [9] but government information sources such as the National Library of Medicine's MEDLINEplus and PubMed systems. In fact, 30% of searches of the PubMed MEDLINE database are performed by the general public [10].

Availability, however, does not ensure that those most in need of patient-oriented medical information actually receive it. Because many patients who need information about a disease or treatment are suffering from a life-threatening or chronic illness, emotional and psychological factors may constitute a barrier to accessing information. Frequently, patients are provided with so much new information, often of a traumatic nature, that they find it almost impossible to recall or understand more than a small amount [11]. To such patients, making the decision to search for information may be very difficult. Even if patients locate a library, they may not be able to transmit accurate information about their specific condition to librarians, who then cannot make appropriate information recommendations. In addition, depending upon the setting, the librarian may have limited knowledge of appropriate resources for what may be a very rare or specific disorder. Although a wealth of information is available through the Internet, many patients lack the physical resources or the knowledge necessary to obtain materials through this route.

The provision of accurate, specific, and timely information to all members of the clinical care team, as well as to the patients themselves, is essential to providing optimum patient care. The Clinical Informatics Consult Service (CICS)* at the Annette and Irwin Eskind Biomedical Library (EBL) has arranged this provision in the clinical setting by placing librarians directly with the team on rounds where they provide critically evaluated, just-in-time information [12, 13]. Drawing on the successful CICS experience, and in keeping with Vanderbilt University Medical Center's (VUMC) effort to improve service to patients and their families, the EBL has embarked on a program to improve access to information using an information prescription mechanism that effectively and efficiently links patients and families with vital medical information.

THE PATIENT INFORMATICS CONSULT SERVICE (PICS)

The EBL has developed a unique and effective program for bringing patients together with the information that they need to become active participants in their own health management. The Patient Informatics Consult Service (PICS), the EBL's consumer health information service, involves the patients' health care providers, specially trained librarians, and a patient-oriented health care information section of the library in an integrated program designed to improve patient care through access to information. Linking the three components is a written referral from the clinician to the library in the form of an “information prescription.”

The information prescription

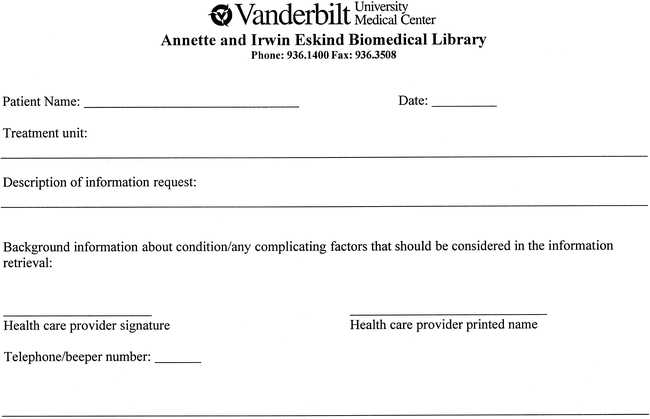

We developed a specialized information prescription form (Figure 1) corresponding to that used for medications. Clinicians use this form to recommend that patients consult with PICS librarians for tailored information packets. The information prescription includes the medical concerns of the patient, together with any additional factors such as co-morbid conditions, medications, treatment options, and personal considerations such as literacy status and religious affiliation when pertinent.

Figure 1.

Patient prescription for information

Several significant problems for patients in obtaining information are reduced by the prescription mechanism. One concern often voiced by clinicians is the ocean of inappropriate or overtly false information available via the Internet. Given that almost anyone can set up a Website, this issue certainly becomes a significant consideration in patient information. The PICS program circumvents this difficulty in two ways. First, librarians select high-quality, authoritative information resources for patients. Secondly, PICS librarians work with patients to help them learn to evaluate information sources independently. Consequently, patients not only receive appropriate and accurate information at the time of need, but they also learn how to identify it in the future, increasing the chance that they will be well-informed and active participants in their own health care. Another obviated problem is that posed by the difficulty patients have in remembering accurately specific terms concerning medical conditions, treatments, or medications; unfamiliar terms overheard in the rush of a doctor's visit may be easily forgotten. In fact, studies by Scheitel et al. [14] and Ley [15] report as much as 68% loss of information following a visit with a clinician. Patient recall is not an issue when a prescription written by the nurse or physician transmits medical terms directly to the librarian, facilitating the retrieval of appropriate information.

PICS information packets

Information prescriptions link patients, clinicians, and information and facilitate the PICS librarians' creation of targeted, individualized information packets. These packets usually consist of information culled from lay-literature sources, medical literature, and authoritative information from the Web, including information from sources such as health organizations (e.g., the American Cancer Society) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH). PICS librarians seek to provide the entire spectrum of authoritative literature written on a topic. Where different opinions are found in the literature, all viewpoints are represented in the information provided to the patient.

PICS librarians make every attempt to provide information at a level appropriate for the patient, focusing on consumer-friendly resources while using additional literature as needed and providing any necessary explanations. As in the CICS program [16], rather than simply selecting resources, the librarian also highlights relevant sections and provides a brief summary for each item. Packets are tailored as much as possible to the patient's situation, making each packet a personalized report rather than a generic compilation of information. The topics for packet requests vary widely, from broad requests for information about head and spinal cord injuries (ranging from prognosis to rehabilitative approaches) to specific queries about therapeutic options for small lymphocytic lymphoma with cutaneous presentation.

An important feature of the PICS service is the dialogue that it promotes among the health care provider, the patient, and the librarian. When information packets are prepared for patients, librarians forward a copy to the referring clinicians with the patients' knowledge. The prescription pad serves to legitimize the role of the librarian in providing information to patients, and providing a packet to both patient and clinician facilitates doctor-patient communication and closes the clinician-librarian feedback loop. As in the CICS, information needs are met in an individualized and timely manner through cooperation of the entire patient care team.

The PICS also addresses the legal considerations inherent in providing patient information. The patient must be informed that the information provided is not medical advice and should not be used as a substitute for consultation with the health care provider. To this end, each packet is accompanied by a disclaimer created with the assistance of university lawyers.

The PICS information service is limited to VUMC patients and their families; PICS staff forward outside inquiries to the EBL's fee-based research service. To meet patient needs, completed packages are delivered to the treatment unit, mailed to the patient's home (if outpatient or after discharge), or picked up at the library by patients, family members, or clinical staff.

Pathfinder development

We have also developed a mechanism to reuse the information provided in patient packets. This mechanism, the Pathfinder Database,† is an introductory resource for finding lay-level information on a specific medical subject. A pathfinder provides pointers to authoritative sources of information on various topics. It seeks to minimize the consumer's exposure to questionable or unreliable information by pointing only to authoritative, respected sources, thus providing a secure avenue for independent information seeking. Pathfinders link to authoritative Websites, EBL-owned books and videos, local organizations and resources, and librarian-created MEDLINE searches and synopses of relevant journal articles. This variety of resources allows for a “stepped” or scaled approach to providing information, allowing the patient or family member to move smoothly from a general description to other patient-friendly materials and to basic medical literature, if desired. This resource also allows for provision of a core information source for patients while leveraging on PICS librarian time and expertise. By including pathfinders on topics for which librarians have “filled” information prescriptions, pathfinders optimize librarian time already spent investigating a particular topic.

Leveraging also on our CICS experience, in which librarians critically appraise the medical literature and indicate the salient points and drawbacks of studies provided in answer to clinical questions, pathfinders contain disease overviews created by librarians. These consumer-friendly overviews describe the disease and its etiology, signs, and symptoms and indicate disease demographics, diagnostic and therapeutic modalities, and prognosis. This practice of authoring brief disease overviews hones PICS librarians' analyzing, filtering, and summarizing skills and allows them to gain experience in presenting medical information to lay people. Adhering to detailed guidelines (Appendix) that address pathfinder creation at both editorial and task-based levels, pathfinder authors cite all statistics and figures, and the resources the librarian consulted in writing the overview are included in a references section. Explicit guidelines promote consistency in a resource with multiple authors, and the guidelines act as a recipe for locating, evaluating, and summarizing consumer health information. Pathfinder authors continually monitor the literature, updating content as new information becomes available. In addition, reminders are sent to authors via email.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

To date, the PICS program has provided information to more than one hundred patients, with considerable positive anecdotal feedback. Formal evaluation of the program is currently underway using a survey form developed to collect information anonymously from clients. This evaluation, included in the information packet with a return envelope and located on the PICS Website,‡ asks questions regarding how understandable, timely, and useful clients consider the information provided. A similar evaluation form is provided to clinicians with the copy of the information packet. Questions are intended to provide feedback to improve the services offered as well as provide some formal marketing data on the value of the service. Evaluations returned have been positive; however, additional data are necessary to estimate quantitatively the value and impact of the service.

Responses from both patient and health care professionals to date indicate that the Patient Informatics Consult Service is an effective and useful service that supports the Vanderbilt University Medical Center mission of excellent patient care. Patients are using the service heavily, and returned evaluations indicate high levels of satisfaction. Despite the early stage of the evaluation process, feedback thus far is positive and encouraging. Not only have patients commented on their appreciation for the service, but clinicians, in addition to providing affirmative feedback, continue to refer many of their patients to us for additional information, often on life-threatening or chronic conditions.

While data on patient satisfaction remains anecdotal at this time, we feel that this represents an excellent potential marketing opportunity as we plan to continue and expand the Patient Informatics Consult Service. Many medical centers now recognize the eagerness of patients to learn about their conditions, and patient satisfaction with received information may come to play a significant role in choice of medical care facility. Medical centers that provide an information service may be favorably considered over those whose patients must seek information through other means.

The PICS' effective “prescription-for-information” mechanism, as well as services including pathfinders and a growing collection of lay-level materials coupled with the information expertise of PICS librarians, positions the EBL to make valuable contributions to patient care. The EBL looks forward to meeting the consumer health information challenge by building on the foundation set in the initial stages of this project. By regular reviews of the service, and continual attention to the comments received through our various feedback mechanisms, the PICS team will constantly seek new ways to create a service that answers the needs of the community of patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Marcia Epelbaum and Antoinette Nelson for their contributions to the PICS program and Shirley Hercules for her writing assistance. We would also like to acknowledge the Vanderbilt Medical Group (VMG) for the initial sponsorship of this service.

Pathfinder Database: editorial guidelines

This document is intended to provide direction for selecting and publishing information in the Patient Informatics Consult Service (PICS) Pathfinder Database. This document will provide the general guiding principles for adding content to the database. Specific instructions on data entry may be found in the Database Instructions document.

Purpose

The Pathfinder Database is intended to be an introductory resource for finding lay-level information on a specific medical subject. At this point, the pathfinder records do not contain any original medical information and do not purport to offer medical advice. The expected use for this database is as an initial introduction into the consumer health literature written about a specific subject.

Intention

The Pathfinder Database does not offer information about a topic as much as it offers instruction on where information can be found. The Pathfinder Database seeks to minimize the consumer's exposure to questionable or unreliable information by pointing only to authoritative and respected sources on the specific topics. Therefore, information professional review of consumer health information, be it Web-based or printed, is the primary intention underlying the creation of this database.

Scope

Topics chosen for inclusion in the Pathfinder Database are chosen because of the universal interest in them. The topics are typically “hot topics” that appeal to a general audience. Topics are also included that reflect the specific audience of VUMC patients. The PICS team selects topics after completing a statistical analysis of PICS research services statistics (i.e., analysis of research requests). Information within each pathfinder record should concentrate on consumer-level resources and only utilize technical or professional resources when the former cannot be found.

Audience and level of information

The intended audience of this database is Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC) patients and their families. All pathfinder records should be written for a nonmedical or nontechnical audience.§ Information written specifically for the consumer should be the focus of the database with medical and nursing literature used as a supplement. Consumer-level information may not be available for all topics, specifically for rare disorders. In this case, technical information will be acceptable. Nursing literature and medical literature from major general practice publications is the preferred alternative to consumer literature. General medical publications such as JAMA should be selected over specialty publications.

Authority and resource selection

Information presented in the database must meet strict criteria. Because the target audience of this database is consumers with no or limited medical knowledge, the database must deliver only authoritative, respected, and accepted information. Generally, this condition requires that information found in each record should come from established health resources such as those sponsored by government and academic medical institutions.

Selection of print and audiovisual material

As a general rule, all resources found in the Patient Education Collection in the Eskind Biomedical Library (EBL) are suitable for inclusion in the database. The selection of this material has been carefully reviewed by PICS staff, therefore, authors may be confident that this information is proven to be authoritative and reliable. However, authors should be sensitive to the age of the information presented in print literature. In a fast-moving area of medicine, the research and practice may prove current print resources to be out-of-date. Therefore, authors should carefully review this material in light of the present day practice standards.

Selection of Web resources

The selection of Web resources is problematic and requires an advanced knowledge of the subject area and the sources of information within a topic area. Generally, information gleaned from U.S. government sources—such as the National Library of Medicine, the National Science Foundation, and the National Cancer Institute—and major academic research centers, for example, are authoritative, and authors can rely on the information found on these Websites. However, even within the safe boundaries of such Websites, authors must still be aware that controversial treatments or diagnostic theories may be presented. Therefore, authors must be sensitive to the many treatment, diagnostic, or other debates within the medical community and must make every effort to represent all viewpoints.

Resource selection and thoroughness of the presented information is particularly important as this database should not be seen as prescribing any direction to the patient as to treatment or other options. A good rule of thumb for authors to follow is to read textbook literature, consumer health literature, and relevant journal articles from respected sources, then judge all Websites based upon what they have learned about the condition.

Only after careful review should a private individual's Web page about a condition be referenced in a pathfinder record. The information on these sites is not held up to the same standards of review (or any standards for that matter) as information that is found on organizational, institutional, or governmental Websites, so authors should carefully appraise the site's content.

Legality

The purpose of the PICS Pathfinder Database is to aid VUMC patients and their families with their initial foray into the world of consumer health literature. Therefore, this database is about pointing to subject-specific resources, not about practicing medicine. Nowhere in the database is there a place for dispensing medical advice or suggesting treatment options. The database is simply exposing the layperson to the authoritative and reliable information available on a specific topic. To ensure that the database is not seen as suggesting one viewpoint over another (where multiple viewpoints exist), authors should be meticulous in their representation of all viewpoints.

Copyright

The information provided in the description in the Overview should be an original summary of the information used to research the topic. Authors should never directly copy text from a Website, book, video, or any other published resource. When statements are made that directly refer to a published material the author must cite these statements. Procedures for citing references may be found in the Database Instructions document. If statements are not cited, the database editors will refuse to “publish” the pathfinder, and authors will not be credited with having done the work.

Currency

All information contained in the Pathfinder Database must be as current as possible. Pathfinder authors agree to maintain their topics by checking that all links to resources are working and that the information contained in the overview is correct and reflects the current views as stated in the medical literature. Authors will receive an automatically generated email reminder every six months to update the pathfinder. All authors are expected to update their topic more frequently as dictated by current research and practice.

Pathfinder Database: instructions for authors

This document is provided to all PICS pathfinder authors and is intended to outline the directions for adding entries to the PICS Pathfinder Database. These instructions represent a formatting standard that will enable a consistency of quality throughout the database.

Note

Required fields are in bold. If these fields are left blank, the following error message will appear:

“Error: [No value entered for specific field. Please select “Back” in your browser and correct this problem before continuing].”

VUMC Pathfinder: administration page

Add a Pathfinder: Enter the name of your new pathfinder topic and click on the Add button.

Edit a Pathfinder: Click on the down arrow to find and select your pathfinder. Click on the Edit button to go to the main editing page. Only authors of the pathfinders (or the PICS editors) should make changes to the document. If you see an inconsistency or something that needs to be changed in another pathfinder, please contact the author or the persons listed at the beginning of this document.

Delete a Pathfinder: Click on the down arrow to select a pathfinder to be deleted. Click on the Delete button to delete the highlighted pathfinder. Pathfinders will be deleted by the PICS editors if the information in the document is out-of-date or is found to be incorrect. Only authors of the pathfinders and PICS editors are permitted to delete a pathfinder. If you see an inconsistency or something that needs to be changed in another pathfinder, please contact the authors or PICS personnel.

Administration page: main editing page

This page provides links to all the fields within the Pathfinder Database record. Click on the linked sections to edit the section of the pathfinder that needs updating. The fields included in the database are:

General information

Overview references

Local resources

Journal articles

VUMC library books

VUMC library videos

Databases

Web links

General information

This section serves as an introduction to the topic for the reader. It also provides administrative information about the database record. All fields are required.

Pathfinder Title: Enter the title of the Pathfinder topic. Please use the common name associated with the condition.

Web Status: This field indicates whether the pathfinder is active and viewable on the PICS Pathfinder Web page or inactive and not accessible through the database. Offline is the default. All pathfinders should be set to Offline and will be listed as Active by the editors once the editors have reviewed the record.

Owner: Owner refers to the EBL staff member who authored the pathfinder. Click on the down arrow to select your name from the list.

Include in list of “Most Popular” Pathfinders: Popular pathfinders should be ones with a widespread appeal or ones that are written about common disorders. In general, Most Popular Pathfinders will be disease topics. Pathfinders that are not Most Popular would be narrower classifications of a condition or tests or treatments for a condition. Whether a pathfinder is deemed Popular is subject to the editors' discretion, and this status will be changed if necessary. If you are in doubt as to what to do, leave the default button enabled.

- Description: This field should contain a description of the topic. Please write your overview in paragraph form. Do not include headings such as “symptoms,” “treatment,” etc. This overview should provide the reader with some knowledge and understanding of the topic so as to understand the information that will be presented within the remainder of the pathfinder record. Content of the overview should address, but is not limited to, the following areas: a thorough but concise definition, the etiology, the disease function (i.e., how the disease manifests itself and what it does to make you sick), demographics (i.e., what groups of people generally contract the disease or condition), the symptoms associated with the disease, tests and other diagnostic tools and factors, options for therapy (i.e., drugs or surgery, etc.), and the prognosis for the average patient with this disease. If statistics are mentioned or cited, it is mandatory that these be referenced within the overview. Reference material by including an in-text parenthetical citation after the reference. This citation should refer to a reference listed in the Overview References Section, which is discussed in more detail below. The in-text parenthetical citation should look like the following example:The incidence of XYZ disease is growing with 90% of the adult male population aged between twenty-three and thirty exhibiting signs of an outbreak (National XYZ Disease Council, 2000).

Search Keywords: Enter words that will help someone searching the Pathfinder Database to find your pathfinder. Include various keywords strongly identified with the disease as well as partial terms and common misspellings. Remember that this database will be used by patients and other laypeople so do not choose only technical terms that would not be used by patients (i.e., MeSH or technical medical jargon). For example, keywords for breast cancer should include both breast cancer and breast neoplasms.

Referral Directory Keywords: You can search this database to find terms under which appropriate physicians and VUMC clinical centers are indexed.

PubMed Search Query String: Enter the query string you used to find articles on PubMed. This will link directly to PubMed and will provide the reader with an up-to-date citation list on the topic. Please make sure you limit to human and English as well as any other variables for your specific condition. To enter the uniform resource locator (URL), simply do your search in PubMed, click Details from the top bar on the results page, click URL, copy the URL from the navigation bar on your browser, and paste into this text box.

Overview references

Enter the bibliographic information for the sources you used to write the Description in the General Information section. Click the Edit button to make changes to existing references. Click the Delete button to delete an existing reference. Please revise your bibliographic information when you revise your description.

Title: Title of the source.

Authors: Enter the author's last name first and first two initials (i.e., Doe, JL).

Source: The complete bibliographic information including page numbers, chapter numbers, Web location, and library call number and location, if applicable.

Local resources

Provide information about local support groups, clinics, and organizations related to the topic. Examples of appropriate resources are VUMC clinics and local chapters of national organizations (i.e., the American Heart Association). Information about these resources may be found in the VUMC Directory, the VUMC Web pages, the Nashville Telephone Book, organization Web pages, and the Encyclopedia of Associations (located in the EBL Reference Collection).

Name: Group, clinic, or organization name.

URL: Web address or email contact if available.

Street 1: Street address.

Street 2: Any other additional addressing information such as building and room number, P.O. Box, etc.

City:

State:

Zip:

Phone 1: Office number of contact person.

Phone 2: Other necessary contact telephone or fax number.

Description: Brief description of the resource. Include the type of resource and the services offered. List any important details such as office hours, etc.

Journal articles

Enter citations for a few articles that have particularly good descriptions of the topic. If possible, these articles should represent the consumer health literature as well as the nursing and medical literature. Where good review articles exist in the general nursing and medical literature, choose these articles as the information is often more accessible than the information found in a specialty journal. To edit an existing article entry, click on the Edit button. To delete an existing article entry, click on the Delete button.

Article Title: Title.

Authors: Enter the author's last name first and first two initials (i.e., Doe JL). If there are more than three authors please use the et al. convention (i.e., Robbins T, Sarandon S, et al.).

Journal Name: Enter the title in full (i.e., New England Journal of Medicine).

Year of Publication: Enter the full year (i.e., 1999).

Citation: Enter the citation as it appears (or would appear) in MEDLINE.

Summary: Summarize the parts of the article that you think are particularly useful for the understanding of the topic.

VUMC library books

Search the library catalog and enter books that are pertinent to the topic. Please limit to books found only within EBL. If possible, choose books from the Patient Education Collection and supplement with books from the medical and nursing collection if necessary. If an encyclopedic or textbook work is listed here, please list the chapter number and the author of the chapter in addition to the book title. To edit an existing book entry, click on the Edit button. To delete an existing book entry, click on the Delete button.

Title: Full title of the book.

Authors: Enter the author's last name first and first two initials (i.e., Doe, JL).

Category: Books is the default. Change to Dictionary, Encyclopedia, or Handbook if one of these better describes the format of the work.

Publisher:

Year of Publication: Enter the full year (i.e., 1999).

Chapter Number and Title: If the information is in a chapter within a larger, multi-topic volume, please list the chapter number or title, author, and page numbers.

Call Number: Location within the EBL collection.

Location: Enter the location as found in the catalog record (i.e., Reference, Patient-Ed, Books-3dFl.).

VUMC library videos

Search the library catalog to find videos relevant to the topic. If possible, choose only videos from the PICS collection and supplement with others if necessary. To edit an existing video entry, click on the Edit button. To delete an existing video, click on the Delete button.

Title: Full title of video.

Extra description: Use this field to note special location or topic information such as a Grand Rounds tape number. If the video is part of a series, enter the series title here.

Authors: Enter the author's last name first and first two initials (i.e., Doe, JL, or the production company if no author is credited).

Publisher:

Year of Publication: Enter the full year (i.e., 1999).

Call Number: Location within the EBL collection.

Location: Enter the location as found in the catalog record.

Databases

List databases that contain information about the topic. Choose databases specific to the condition as well as general databases (i.e., MEDLINEplus). Information in this field lists possible places for a patient to look for information beyond the Pathfinder Database. Include consumer databases as well as medical or technical databases. To edit an existing database entry click on the Edit button. To delete an existing database entry click on the Delete button.

Web links

List Websites specifically related to the topic. General sites that contain information about the topic should also be included here. A short description about the Website including the sponsoring organization and what services and tools are available on the site should be entered. To edit an existing Website entry, click on the Edit button. To delete an existing Website entry, click on the Delete button.

Title: Title of the Website and the sponsoring organization.

URL: Enter the full Web address (i.e., http://…).

Category: Select the category that best represents the type of site. Choose from Information/Organization, Clinical Trials, and Clinical Guidelines.

Description: Enter a few sentences regarding the type of information and the sponsoring organization (i.e., university medical center, AHRQ, etc.). For organization information, please also list a contact name, number, or address in this field.

Updates

All pathfinders must be updated no less frequently than every six months. The database will automatically email each author six months after the last modification of the pathfinder. At that time, authors must review the content of the pathfinder and verify or update the content as appropriate. In the event that the information does not change, authors must still click on the Edit button to certify that the content has been reviewed. At that time, the Information Last Modified field will change to the current date. If new information about the topic comes to light more frequently than six months, authors are expected to update the pathfinder to keep the information accurate and up-to-date.

Footnotes

* See also the article by Jerome et al. on pages 178 to 185 of this issue of the Bulletin of the Medical Library Association.

† The Pathfinder Database may be viewed via the PICS Website at http://www.mc.vanderbilt.edu/biolib/pics/.

‡ The survey may be viewed at http://www.mc.vanderbilt.edu/biolib/services/pics/survey.html.

§ Although special cases may arise where patients or family members are interested in information beyond the consumer level, these cases are not typical and will not be covered by this database. In this situation, it is expected that the PICS staff members will direct the patron to appropriate, existing resources.

REFERENCES

- Greenfield S, Kaplan SH, Ware JE, Yano EM, and Frank HJ. Patients' participation in medical care: effects on blood sugar control and quality of life in diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 1988 Sep–Oct; 3(5):448–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beisecker AE, Beisecker TD. Patient information-seeking behaviors when communicating with doctors. Med Care. 1990 Jan; 28(1):19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notkin H. How a consumer health library can help streamline your practice. West J Med. 1994 Aug; 161(2):184–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett EE. Cost-benefit analysis of patient education. Patient Educ Couns. 1995 Sep; 26(1-3):87–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earl M. Caring for consumers: empowering the individual. American Libraries. 1998 Nov; 29(10):44–6. [Google Scholar]

- Humphries AW, Kochi JK. Providing consumer health information through institutional collaboration. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1994 Jan; 82(1):52–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove TL. Planetree health information services: public access to the health information people want. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1994 Jan; 82(1):57–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyson TR. The Internet: tomorrow's portal to non-traditional health care services. J Ambulatory Care Manage. 2000 Apr; 23(2):1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris TA, Guard JR, Marine SA, Schick L, Haag D, Tsipis G, Kaya B, and Shoemaker S. Approaching equity in consumer health information delivery: NetWellness. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1997 Jan–Feb; 4(1):6–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Library of Medicine. NLM Newsline. [Web Document]. Bethesda, MD: The Library, 1998. [rev. 14 Feb 2000; cited 17 Aug 2000]. <http://www.nlm.nih.gov/pubs/nlmnews/janmar98.html#Online>. [Google Scholar]

- McLellan F. “Like hunger, like thirst:” patients, journals, and the Internet. Lancet. 1998 SII: 39–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuse NB. Advancing the practice of clinical medical librarianship [editorial]. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1997 Oct; 85(4):437–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuse NB, Kafantaris SR, Miller MD, Wilder KS, Martin SL, Sathe NA, and Campbell JD. Clinical medical librarianship: the Vanderbilt experience. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1998 Jul; 86(3):412–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheitel SM, Boland BJ, Wollan PC, and Silverstein MD. Patient-physician agreement about medical diagnoses and cardiovascular risk factors in the ambulatory general medical examination. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996 Dec; 71(12):1131–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley P. Giving information to patients. In: Eisner JR, ed. Social psychology and behavioral science. New York, NY: John Wiley, 1982 339–65. [Google Scholar]

- Giuse NB, Kafantaris SR, Miller MD, Wilder KS, Martin SL, Sathe NA, and Campbell JD. Clinical medical librarianship: the Vanderbilt experience. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1998 Jul; 86(3):414. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]