Abstract

Serum- and glucocorticoid-regulated kinase 1 (sgk1) participates in diverse biological processes, including cell growth, apoptosis, and sodium homeostasis. In the cortical collecting duct of the kidney, sgk1 regulates sodium transport by stimulating the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC). Control of subcellular localization of sgk1 may be an important mechanism for modulating specificity of sgk1 function; however, which subcellular locations are required for sgk1-regulated ENaC activity in collecting duct cells has yet to be established. Using cell surface biotinylation studies, we detected endogenous sgk1 at the apical cell membrane of aldosterone-stimulated mpkCCDc14 collecting duct cells. The association of sgk1 with the cell membrane was enhanced when ENaC was co-transfected with sgk1 in kidney cells, suggesting that ENaC brings sgk1 to the cell surface. Furthermore, association of endogenous sgk1 with the apical cell membrane of mpkCCDc14 cells could be modulated by treatments that increase or decrease ENaC expression at the apical membrane; forskolin increased the association of sgk1 with the apical surface, whereas methyl-β-cyclodextrin decreased the association of sgk1 with the apical surface. Single channel recordings of excised inside-out patches from the apical membrane of aldosterone-stimulated A6 collecting duct cells revealed that the open probability of ENaC was sensitive to the sgk1 inhibitor GSK650394, indicating that endogenous sgk1 is functionally active at the apical cell membrane. We propose that the association of sgk1 with the apical cell membrane, where it interacts with ENaC, is a novel means by which sgk1 specifically enhances ENaC activity in aldosterone-stimulated collecting duct cells.

Keywords: Cell Surface, ENaC, Ion Channels, Kidney, Serine/Threonine Protein Kinase, Aldosterone, Cortical Collecting Duct, Serum- and Glucocorticoid-regulated Kinase 1 (sgk1), Sodium Transport

Introduction

Serum- and glucocorticoid-regulated kinase 1 (sgk1) is a key regulatory kinase that controls a wide range of biological processes, including cell proliferation, cell survival, and sodium (Na+) homeostasis. Moreover, sgk1 is in a position to integrate a diverse set of environmental cues and enable cells to respond appropriately within a specific physiological context. For example, in kidney collecting duct cells, the mineralocorticoid hormone aldosterone rapidly (within 15–30 min) induces sgk1 gene transcription and increases sgk1 protein levels (1, 2). Growth factors activate the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling pathway, which initiates a phosphorylation cascade that stimulates sgk1 catalytic activity (3, 4). sgk1 thus transduces information from steroid hormone and growth factor pathways to downstream effectors ensuring appropriate timing and context of physiological responses.

One of the best characterized downstream targets of sgk1 in collecting duct cells is the epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC),2 an ion channel that is the rate-limiting step for Na+ absorption in the kidney collecting duct and plays a critical role in regulating Na+ balance and blood pressure. One important mechanism by which sgk1 increases ENaC activity involves modulating Nedd4-2 (5, 6), an E3 ubiquitin ligase that, in the absence of sgk1, regulates cell surface expression of ENaC by channel ubiquitination. At sufficient levels, sgk1 phosphorylates Nedd4-2, promoting interaction of Nedd-4-2 with 14-3-3 proteins (7–9), thus decreasing the interaction of Nedd-4-2 with ENaC and enhancing ENaC expression and activity at the cell surface.

A less well recognized mechanism underlying the stimulatory effect of sgk1 on ENaC activity involves direct activation of ENaC at the plasma membrane. In outside-out membrane patches from Xenopus laevis oocytes expressing ENaC, recombinant sgk1 stimulates ENaC activity; introduction of an S621A mutation within the sgk1 consensus phosphorylation motif of the COOH-terminal tail of α-ENaC abolishes this stimulatory effect (10). Depletion of cholesterol from the cell membrane through methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD) treatment of ENaC-expressing oocytes also abolishes sgk1 stimulation of ENaC, suggesting that a cholesterol-rich lipid microenvironment surrounding ENaC helps to recruit or organize regulatory proteins for functional interactions at the plasma membrane (11). For sgk1 to directly stimulate ENaC, the kinase presumably would localize near the ion channel at the plasma membrane, a finding that has yet to be documented.

Indeed, one likely determinant for selectivity of sgk1 action involves its subcellular localization, which could dictate how sgk1 can activate specific substrates. In this regard, sgk1 has been found in the endoplasmic reticulum (12, 13), mitochondria (14, 15), cytosol (3, 16–20), nucleus (18, 19, 21), and plasma membrane (17, 22). However, which subcellular locations are required for sgk1-regulated ENaC activity in collecting duct cells has yet to be established. This has been a major obstacle for understanding how sgk1 can respond appropriately to environmental cues to specifically stimulate ENaC activity in kidney cells.

In this study, we hypothesized that sgk1, an intracellular protein kinase, associates with the apical cell membrane through protein-protein interactions with ENaC. We show in mpkCCDc14 cells, a well characterized model system for the principal cells of the cortical collecting duct of mammalian kidney (23), that a fraction of aldosterone-inducible sgk1 associates with the apical membrane. We also demonstrate that sgk1 interacts with ENaC in kidney cells and that this interaction enhances sgk1 association with the cell membrane. In aldosterone-stimulated mpkCCDc14 cells, endogenous sgk1 expression in the apical surface fraction can be modulated by treatments that increase or decrease ENaC expression at the apical membrane. Finally, in single channel recordings of excised inside-out patches from the apical membrane of aldosterone-stimulated A6 collecting duct cells, we show that inhibition of endogenous sgk1 activity in these patches decreases ENaC activity by inhibiting ENaC open probability (Po). We conclude that the apical membrane of collecting duct cells is an important site for sgk1-mediated regulation of ENaC.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture

Immortalized mouse kidney cortical collecting duct (mpkCCDc14) cells, kindly provided by Dr. Alain Vandewalle, and human embryonic kidney (HEK293T) cells were maintained as described previously (7, 24). mpkCCDc14 cells were subcultured onto 24-mm permeable supports (0.4 μm pore size, Costar, Cambridge, MA) and grown in defined medium until transepithelial resistance (Rte) reached values between 800 and 1200 Ω·cm2, as measured with an EVOM “chopstick” voltmeter (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL). Cells were then switched to supplement and serum-free media for 48 h before treatment with aldosterone (1 μm) for varying periods to induce endogenous sgk1 expression.

Subcellular Fractionation in mpkCCDc14 Cells

Polarized mpkCCDc14 cells were treated with vehicle control or aldosterone, scraped from permeable supports into lysis buffer ((in mm): 10 HEPES, 10 KCl, 0.1 EDTA, 1 DTT, 0.4% Nonidet P-40), and centrifuged at 10,000 × g. The pellets were resuspended in nuclear extraction buffer ((in mm): 20 HEPES, 400 NaCl, 1 EDTA and 1 DTT), centrifuged at 24,000 × g, and isolated as nuclear fractions. Supernatant fractions from the 10,000 × g spin were further spun at 100,000 × g for 1 h to separate the membrane fraction (pellet) that was then resuspended in lysis buffer, although the cytosolic fraction remained in the supernatant.

Cell Surface Biotinylation Assay

Surface biotinylation studies were performed on polarized mpkCCDc14 cells or on transfected HEK293T cells. Confluent cells were washed three times with ice-cold PBS-CM ((in mm): PBS with 1 CaCl2 and 1 MgCl2, pH 7.4). The apical membrane was biotinylated with 1 mg/ml sulfo-NHS-biotin (ThermoFisher Scientific, Rockford, IL) in PBS-CM on ice; the basolateral side of cell monolayers remained in serum-containing media. After quenching free biotin on the apical side with 100 mm glycine in PBS-CM, both sides of cell monolayers were washed with ice cold PBS-CM, and cells were lysed in Nonidet P-40 lysis buffer ((in mm): 0.4% sodium deoxycholate, 1% Nonidet P-40, 63 EDTA, 50 Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, containing protease inhibitors (ThermoFisher Scientific)). Biotinylated proteins were isolated by incubating cell lysates with immobilized NeutrAvidin-coated beads (ThermoFisher Scientific) overnight at 4 °C. Precipitated proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, and biotinylated sgk1 was probed by immunoblotting either with anti-sgk1 antibody (1:1000, Sigma) for detection of endogenous sgk1 or with anti-FLAG antibody (1:25,000, Sigma) for detection of heterologously expressed sgk1. Immunoblots were also probed with a pan-cadherin antibody (1:5000, Sigma) to confirm that equal amounts of cell surface-associated proteins were present in the NeutrAvidin pulldowns. Blots were also probed with an antibody against α-tubulin (1:5000, Sigma) or histone (1:200, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) to confirm that intracellular proteins were not generally being pulled down.

To estimate the portion of sgk1 that associates with the apical surface fraction of aldosterone-stimulated mpkCCDc14 cells, different amounts of biotinylated protein were first precipitated overnight with NeutrAvidin-coated beads. On the 2nd day, the beads were recovered, and the supernatants were re-precipitated overnight with a new batch of NeutrAvidin-coated beads. This second precipitation step was done to confirm that cell surface-associated sgk1 was completely recovered from the first precipitation step. Precipitated proteins from both days were run on SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with an anti-sgk1 antibody (supplemental Fig. S1). The percentage of sgk1 associated with the apical surface fraction was estimated by using densitometry analysis to compare the intensities of immunoreactive sgk1 bands in the NeutrAvidin pulldown (from whole cell lysates containing 0.5 mg of input protein) to the intensities of sgk1 bands in whole cell lysates containing 0.5 mg of input protein.

To determine whether sgk1 co-precipitates with cell surface proteins, lysates from biotinylated mpkCCDc14 cells were either left untreated or boiled at 95 °C for 5 min in 2% SDS to disrupt association of sgk1 with integral membrane proteins. All cell lysates were then re-diluted with lysis buffer containing 1% Triton X-100, and equal amounts of biotinylated proteins were isolated with NeutrAvidin-coated beads.

To determine whether increasing or decreasing ENaC at the apical membrane affects association of sgk1 with the apical cell surface fraction, forskolin (10 μm) or MβCD (10–20 mm, Sigma) was added to the basal or apical side of polarized, aldosterone-stimulated mpkCCDc14 cells, respectively, for various times, prior to conducting surface biotinylation assays.

Immunocytochemistry

Aldosterone-stimulated mpkCCDc14 cells grown on permeable supports were washed twice with ice-cold PBS, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, rinsed, and incubated in blocking solution (PBS, 3% BSA, 10% donkey serum) for 1 h. Cells were then incubated with anti-sgk1 antibody (1:100, Sigma) or normal rabbit IgG (at a concentration of IgG equivalent to the anti-sgk1 antibody concentration) at 4 °C overnight. After washing with PBS, cells were incubated in AlexaFluor 488-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (1:800, Invitrogen). Following PBS washes, cells were incubated with Texas Red-labeled phalloidin (1:50, Invitrogen). After further PBS washes, cells were mounted in Vectashield containing DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Cells were imaged on a Carl Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope using LSM Image Browser software (Carl Zeiss International, Thornwood, NJ).

Immunohistochemistry

Adult 129 mice were maintained on a regular chow diet. All procedures were in accordance with the Committees on Animal Research at Stanford University and the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. Mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium. Kidneys were fixed with 2.5% paraformaldehyde in PBS, removed, and post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4 °C for 4 h. After washing with PBS at 4 °C overnight, the tissues were then frozen in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound, and 4-μm sections were cut. Frozen kidney sections were washed with PBS and treated with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 5–10 min. Sections were incubated with blocking solution (PBS, 3% BSA, 10% donkey serum) for 40 min and then incubated with rabbit anti-sgk1 antibody (1:100, Sigma) and goat anti-aquaporin-2 (1:50, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibodies at 4 °C overnight. After washing with PBS, sections were incubated with AlexaFluor 546-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (1:800, Invitrogen) and AlexaFluor 633-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG (1:800, Invitrogen). Sections were washed with PBS, mounted, and then imaged as above.

Transient Transfection of HEK293T Cells

HEK293T cells were cultured on 10-cm dishes in DMEM containing 10% FBS and penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) with plasmid DNA encoding mouse sgk1-FLAG (2 μg) and differentially COOH-terminal epitope-tagged mouse ENaC subunits (α-HA, β-V5, and γ-myc, 1 μg each) or expression vector control (pMO, 3 μg). In some experiments, mouse sgk1-HA was transfected instead of sgk1-FLAG. The subcloning of mouse sgk1 into pMO expression vectors has been described previously (24). In some experiments, cells were also treated with MG132 (10 μm, Sigma) for 2 h to limit proteasomal degradation of sgk1 prior to biotinylation and lysis of cells.

Co-immunoprecipitation Experiments

Transfected HEK293Tcells were harvested in Nonidet P-40 lysis buffer. Immunoprecipitation was performed using antibodies against sgk1 (anti-FLAG). Samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with antibodies against α-ENaC (anti-HA, 1:10,000) or sgk1 (anti-FLAG, 1:25,000).

Ussing Chamber Measurements

Polarized mpkCCDc14 cell monolayers were mounted between the Lucite half-chambers of the Ussing chamber apparatus (Physiological Instruments, San Diego) for electrophysiological experiments, as described previously (25, 26). To determine sgk1-inhibitable short circuit current (Isc), cells were treated with vehicle control or aldosterone (1 μm); base-line Isc was allowed to stabilize, and then GSK650394 (6 μm, Tocris, Ellisville, MO), an inhibitor of sgk1, was added to both sides of the cell monolayers. Twenty minutes after the addition of GSK650394, amiloride (10 μm, Sigma), an inhibitor of ENaC, was added to the apical side of cell monolayers to evaluate residual ENaC-mediated Isc (supplemental Fig. S2).

Single Channel Electrophysiological Recordings

A6 cells were maintained in tissue culture flasks at 27 °C in a humidified incubator with 4% CO2 in culture medium consisting of three parts F-12 and seven parts Leibovitz's medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1.5 μm aldosterone. Cells were plated onto collagen-coated plastic rings that were mounted onto a recording chamber of an inverted microscope for single channel measurements. In the cell-attached configuration, the pipette and bath solutions contained the following (in mm): 96 NaCl, 3.4 KCl, 0.8 CaCl2, 0.8 MgCl2, and 10 HEPES, pH 7.4 (titrated with 10 n NaOH). Inside-out patches were obtained from cell-attached patches following exchange of the apical bath solution into high K+ solution ((in mm): 3 NaCl, 85.4 KCl, 4 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, and 5 EGTA, pH 7.4 (titrated with 10 n NaOH)). To sustain ENaC activity in excised patches, the high K+ solution was supplemented with 30 μm PIP2 and 100 μm GTP, as described previously (27).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses for comparisons between different treatment groups of mpkCCDc14 and A6 cells were performed using paired or unpaired two-tailed Student's t tests. Differences were considered to be significant at p values <0.05. Sigma Plot (Systat Software) was used to perform nonlinear regression and sigmoidal fitting of the GSK650394 dose response in A6 cells.

RESULTS

Aldosterone Increases sgk1 Protein Expression in the Membrane Fraction of mpkCCDc14 Cells

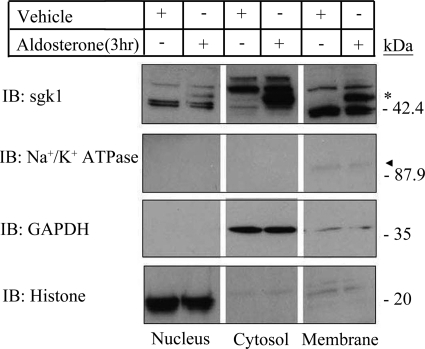

We first examined the subcellular localization of endogenous sgk1 in a mammalian kidney collecting duct model system. We treated polarized mpkCCDc14 cells with aldosterone (1 μm) and isolated nuclear, cytosolic, and membrane fractions by centrifugation at peak levels of sgk1 expression (3 h of aldosterone treatment (28)). Recent work has identified the existence of multiple sgk1 isoforms. In addition to canonical sgk1, which is responsive to aldosterone stimulation and regulates ENaC activity (1, 2), there are different splice variants and translational isoforms of sgk1 (29–31). Some of these variants are also capable of stimulating ENaC (31), although the physiological relevance of these variants is not clear.

We focused on protein expression of canonical sgk1, which is distinguished by being the only isoform with aldosterone-inducible expression. Western blotting with a previously characterized anti-sgk1 antibody (28) demonstrated that aldosterone-inducible sgk1 appeared as two immunoreactive bands clustering around 49 kDa and localized primarily to cytosolic and membrane fractions of mpkCCDc14 cells (Fig. 1). These two bands are likely different phosphorylation variants of canonical sgk1, which have been previously identified (28). There were two additional immunoreactive bands clustering at 42–45 kDa, which were enriched in nuclear and membrane fractions. These smaller immunoreactive bands could represent shorter sgk1 variants, which do not stimulate ENaC activity and have been detected in the nucleus of transfected Chinese hamster ovary cells (29).

FIGURE 1.

sgk1 associates with the membrane fraction of aldosterone-stimulated mpkCCDc14 cells. Representative Western blot is shown of nuclear, cytosolic, and membrane fractions from polarized mpkCCDc14 cells treated with vehicle or aldosterone (1 μm) for 3 h (3 hr). Equal amounts of proteins from each fraction were immunoblotted (IB) with antibodies directed against sgk1, as well as markers for cell membrane (Na+/K+-ATPase), cytosol (GAPDH), and nucleus (histone). * denotes aldosterone-regulated isoform of sgk1 detectable at 49 kDa. Triangle denotes Na+/K+-ATPase immunoreactivity in the membrane fraction, which was more apparent at longer exposure times.

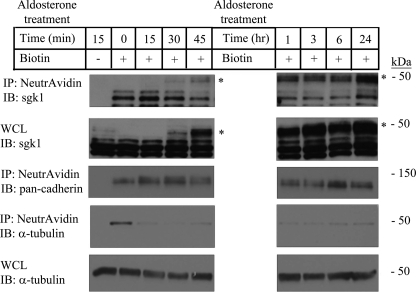

Aldosterone Increases sgk1 Protein Expression in the Apical Cell Surface Fraction of mpkCCDc14 Cells

Given that a portion of sgk1 localized to the membrane fraction of mpkCCDc14 cells, we next examined whether sgk1 associates with the apical plasma membrane, where it might regulate ENaC. We treated polarized mpkCCDc14 cells with aldosterone (1 μm) for various times and assessed sgk1 expression in the apical surface fraction. Although sgk1 expression in whole cell lysates became detectable within 30 min of aldosterone induction and quickly reached saturation by 45 min, expression of sgk1 at the apical membrane gradually rose over the course of 24 h of aldosterone treatment (Fig. 2). We estimated that 5–7% of aldosterone-inducible sgk1 associated with the apical cell surface fraction at peak levels of sgk1 expression (supplemental Fig. S1).

FIGURE 2.

sgk1 associates with the apical cell surface fraction of aldosterone-stimulated mpkCCDc14 cells. Surface biotinylation assays that show sgk1 expression in the apical surface fraction from polarized mpkCCDc14 cells treated with vehicle or aldosterone (1 μm) for various times are indicated in minutes (min) or hours (hr). NeutrAvidin-precipitated proteins (IP) and whole cell lysates (WCL) were immunoblotted (IB) with an anti-sgk1 antibody. * denotes aldosterone-regulated isoform of sgk1. Immunoblots were stripped and re-probed with antibodies directed against pan-cadherin and α-tubulin as loading controls.

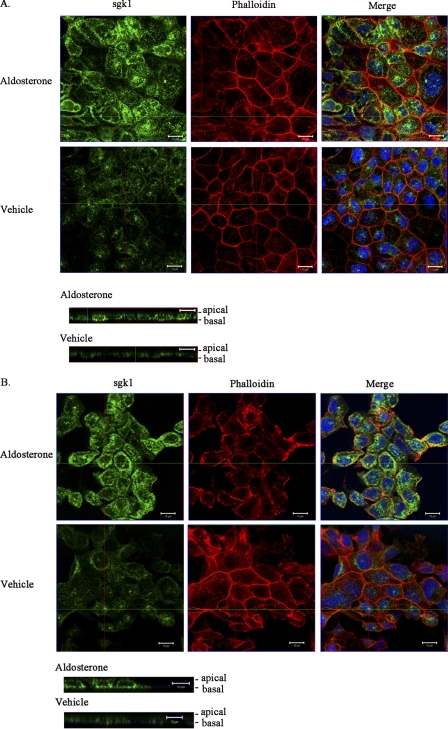

Subcellular Localization of sgk1 in Collecting Duct Cells

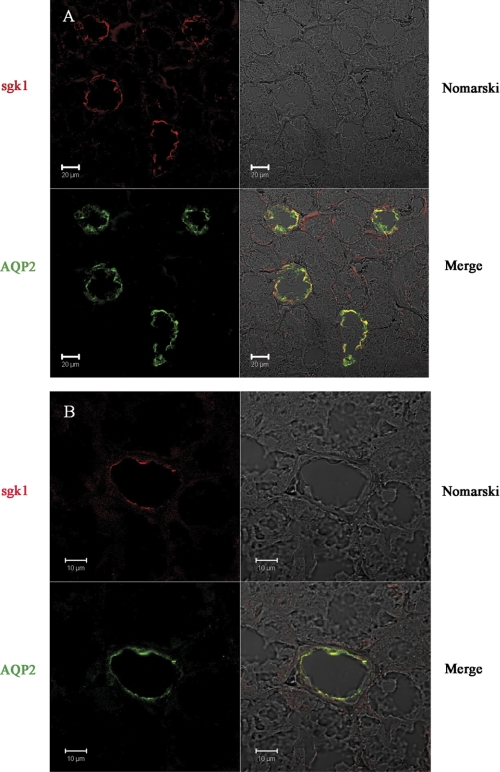

We next used immunofluorescence confocal microscopy to investigate the subcellular localization of endogenous sgk1 in mpkCCDc14 cells. Polarized cells treated with vehicle or aldosterone (1 μm) for 3 h were fixed and stained with an anti-sgk1 antibody. Aldosterone-inducible sgk1 immunoreactivity was detectable in the cytosol and plasma membrane (Fig. 3A); in x-y images taken near the apical pole of cell sheets, aldosterone-inducible sgk1 closely associated with the plasma membrane and co-localized with phalloidin staining of actin filaments (Fig. 3B). We also examined the distribution of sgk1 protein in mouse kidneys. We labeled kidney sections with antibodies directed against sgk1 and aquaporin-2, an established marker of the principal cells of the cortical collecting duct. sgk1 immunoreactivity primarily localized toward the apical surface in aquaporin-2-positive cells, indicating that a fraction of endogenous sgk1 associates with the apical membrane of mouse kidney collecting duct cells (Fig. 4).

FIGURE 3.

sgk1 localizes near the cell membrane of aldosterone-stimulated mpkCCDc14 cells. Confocal immunofluorescence staining of sgk1 in polarized mpkCCDc14 treated with aldosterone (1 μm) or vehicle for 3 h is shown. A, x-y image near the basal pole of cells stained with the following, as indicated: anti-sgk1 antibody with AlexaFluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody (green); Texas Red-conjugated phalloidin, a toxin that binds to F-actin filaments below the plasma membrane (red); merged image of sgk1 immunoreactivity with phalloidin and DAPI staining (blue nuclei). Bottom images are corresponding x-z reconstructions of confocal image stacks of cells labeled with anti-sgk1 antibody (green). B, x-y image near the apical pole of cells stained with the following, as indicated: anti-sgk1 antibody with AlexaFluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody (green); Texas Red-conjugated phalloidin (red); merged image of sgk1 immunoreactivity with phalloidin and DAPI staining (blue nuclei). Bottom images are corresponding x-z reconstructions of confocal image stacks of cells labeled with anti-sgk1 antibody (green). Scale bar, 10 μm.

FIGURE 4.

sgk1 localizes to the apical cell membrane of mouse kidney cortical collecting duct. Confocal immunofluorescence staining of sgk1 and AQP2 in representative kidney sections from 129 mice. Sections were fixed and labeled with anti-sgk1 (red) and anti-AQP2 (green) antibodies and are shown at low (A) or high (B) magnifications. sgk1 immunoreactivity is localized at or near the apical membrane, where AQP2 immunoreactivity is also apparent. Scale bars at 10 or 20 μm, as indicated.

sgk1 Associates with ENaC at the Cell Membrane of Kidney Cells

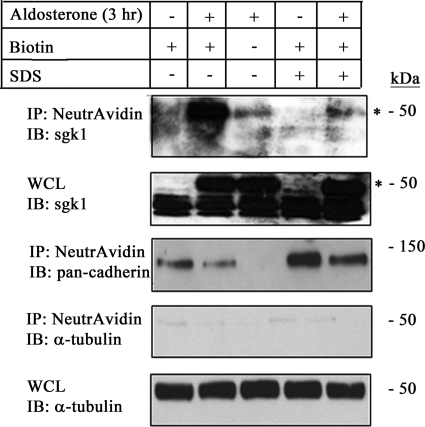

We hypothesized that sgk1, an intracellular protein kinase, associates with the apical membrane of collecting duct cells through protein-protein interactions with transmembrane proteins such as ENaC. To confirm that sgk1 associates with the apical membrane through protein-protein interactions, we first biotinylated the apical surface of control and aldosterone-stimulated mpkCCDc14 cells and then lysed cells with control buffer or buffer containing 2% SDS. The lysates containing 2% SDS were boiled at 95 °C to disrupt protein-protein interactions. Western blotting of biotinylated proteins showed that sgk1 associated with the apical surface of mpkCCDc14 cells in the absence of 2% SDS (Fig. 5, 2nd lane), but this association was disrupted when lysates were boiled in 2% SDS prior to incubation with NeutrAvidin-coated beads (Fig. 5, 5th lane). This finding demonstrates that sgk1 associates with the apical membrane through interactions with integral membrane proteins.

FIGURE 5.

Association of sgk1 with the apical cell surface fraction is disrupted by boiling mpkCCDc14 cell lysates in 2% SDS. Surface biotinylation assays showing sgk1 expression in the apical surface fraction of polarized mpkCCDc14 cells were treated with aldosterone (1 μm) for 3 h (3 hr). Whole cell lysates were boiled in 2% SDS or left untreated, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” NeutrAvidin-precipitated proteins (IP) or whole cell lysates (WCL) were immunoblotted (IB) with antibodies directed against sgk1, pan-cadherin, and α-tubulin, as indicated. * denotes aldosterone-regulated isoform of sgk1.

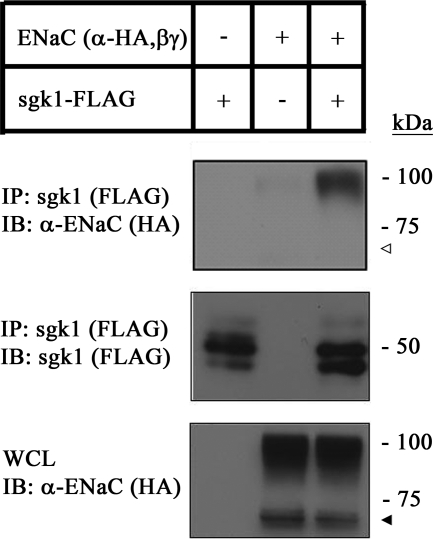

One previous report has demonstrated that sgk1 physically interacts with the COOH-terminal tails of α- and β-ENaC subunits in a GST pulldown assay (32). We postulated that ENaC may be one integral membrane protein that can bring sgk1 to the cell membrane. To confirm whether this interaction takes place in kidney cells, we performed co-immunoprecipitation experiments with HEK293T cell lysates co-expressing HA-labeled α-ENaC, β-ENaC, γ-ENaC, and FLAG-labeled sgk1 and found that α-ENaC co-immunoprecipitated with sgk1 (Fig. 6), confirming that sgk1 associates with α-ENaC in kidney cells. Interestingly, although both uncleaved and cleaved forms of α-ENaC were expressed (33–35), the uncleaved form of α-ENaC predominantly associated with sgk1.

FIGURE 6.

sgk1 interacts with α-ENaC in transfected HEK293T cells. Co-immunoprecipitation of sgk1 and ENaC in HEK293T cells transfected with sgk1-FLAG, HA-α-ENaC, V5-β-ENaC, and myc-γ-ENaC. sgk1 was immunoprecipitated (IP) (anti-FLAG) and immunoblotted (IB) with antibodies against α-ENaC (anti-HA) or sgk1 (anti-FLAG). Whole cell lysates (WCL) were probed for α-ENaC. sgk1 expression was not detectable in whole cell lysate samples (data not shown). Closed triangle indicates presence of cleaved form of α-ENaC in whole cell lysate fraction, and open triangle indicates relative absence of cleaved form of α-ENaC in sgk1 immunoprecipitated fraction.

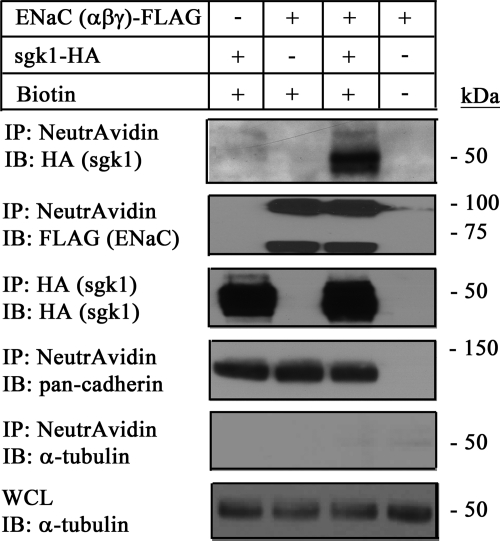

Given that sgk1 interacts with ENaC and associates with the apical membrane in kidney cells, we asked whether the sgk1-ENaC interaction enhances the association of sgk1 with the cell membrane. We co-expressed FLAG-labeled ENaC (α-, β-, and γ-) and HA-labeled sgk1 in HEK293T cells, biotinylated cell surface proteins, and then isolated them with NeutrAvidin-coated beads. Western analysis of the biotinylated fraction showed that although a small amount of sgk1 associated with the plasma membrane (Fig. 7, 1st lane), this association was markedly enhanced in cells expressing cell surface ENaC (Fig. 7, 3rd lane). Together, these results suggest that ENaC interacts with and brings sgk1 to the cell membrane.

FIGURE 7.

sgk1 interacts with ENaC at the cell surface of HEK293T cells. Surface biotinylation assays showing sgk1 expression in the cell surface fraction of HEK293T cells co-expressing sgk1-HA alone or in combination with FLAG-tagged α-ENaC, β-ENaC, and γ-ENaC. NeutrAvidin-precipitated proteins (IP) were immunoblotted (IB) with antibodies directed against sgk1 (anti-HA), ENaC (anti-FLAG), pan-cadherin, and histone, as indicated. sgk1 expression in the cell surface fraction was enhanced with cell surface ENaC expression. sgk1 expression was not detectable in whole cell lysate samples (data not shown), but it was detectable in the immunoprecipitated samples (IP: HA and IB: HA).

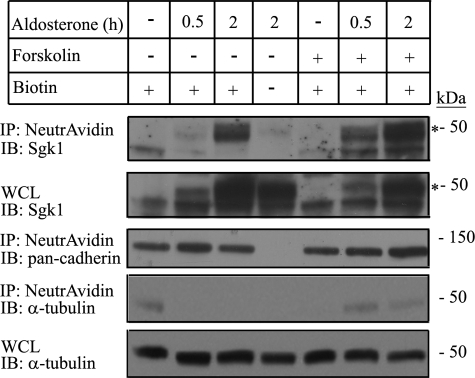

Forskolin Treatment Increases sgk1 Expression in the Apical Cell Surface Fraction of mpkCCDc14 Cells

To test whether endogenous sgk1 expression in the apical cell surface fraction increases under conditions associated with enhanced apical membrane ENaC expression, we treated polarized, aldosterone-stimulated mpkCCDc14 cells with forskolin for various times and then biotinylated cell surface proteins on the apical membrane. Forskolin enhances intracellular cAMP concentration and acutely increases the number of ENaC channels at the apical membrane in several collecting duct model systems (36–38), including in mpkCCDc14 cells (39). We found that when mpkCCDc14 cells were treated with both forskolin and aldosterone, there was an increase in sgk1 expression in the apical cell surface fraction (Fig. 8, 6th and 7th lanes) compared with what was observed at similar time points in cells treated with aldosterone alone (Fig. 8, 2nd and 3rd lanes).

FIGURE 8.

Association of sgk1 with the apical cell surface fraction of aldosterone-stimulated mpkCCDc14 cells is increased by basal addition of forskolin. Surface biotinylation assays showing sgk1 expression in the apical surface fraction of polarized mpkCCDc14 cells treated as indicated: aldosterone (1 μm) for 0, 0.5, or 2 h (h); aldosterone (1 μm) for 0, 0.5, or 2 h; and concurrent treatment with forskolin (10 μm) for 0.5 h. NeutrAvidin-precipitated proteins (IP) or whole cell lysates (WCL) were immunoblotted (IB) with antibodies against sgk1, pan-cadherin, and α-tubulin, as indicated. * denotes aldosterone-regulated isoform of sgk1.

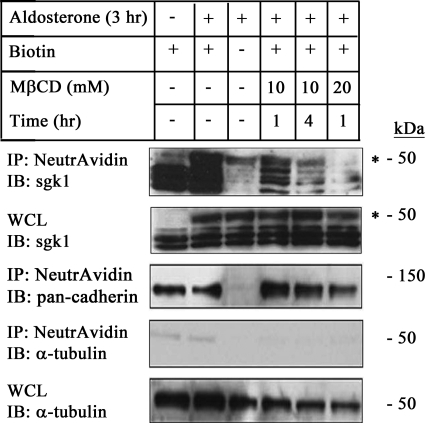

MβCD Treatment Decreases sgk1 Expression in the Apical Cell Surface Fraction of mpkCCDc14 Cells

ENaC is present in lipid raft fractions at the apical membrane of collecting duct cells. Treatment of cells with the cholesterol-depleting agent MβCD decreases ENaC expression in this fraction (40, 41). We therefore used MβCD treatment as a means to decrease the number of ENaC channels in the apical membrane and asked whether there was a corresponding decrease in the association of sgk1 with the apical cell surface. We incubated the apical side of polarized, aldosterone-stimulated mpkCCDc14 cells with MβCD at various concentrations and incubation times, and we isolated the apical cell surface fraction. Immunoblotting showed that sgk1 expression in this fraction decreased with MβCD treatment in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 9, 4th to 6th lanes).

FIGURE 9.

Association of sgk1 with the apical cell surface fraction of aldosterone-stimulated mpkCCDc14 cells is decreased by apical addition of MβCD. Surface biotinylation assays showing sgk1 expression in the apical surface fraction of polarized mpkCCDc14 cells as indicated: aldosterone (1 μm) for 3 h (3 h); aldosterone (1 μm) for 3 h, and concurrent treatment with MβCD (10 or 20 mm) for 1 or 4 h (hr), as described under “Experimental Procedures.” NeutrAvidin-precipitated proteins (IP) or whole cell lysates (WCL) were immunoblotted (IB) with antibodies against sgk1, pan-cadherin, and α-tubulin, as indicated. * denotes aldosterone-regulated isoform of sgk1.

MβCD Treatment Decreases the Stimulatory Effect of sgk1 on ENaC Currents in mpkCCDc14 Cells

Given that direct activation of ENaC by recombinant sgk1 in excised membrane patches from X. laevis oocytes expressing ENaC is disrupted when cholesterol is depleted from the cell membrane (11), we evaluated whether MβCD treatment attenuates the stimulatory effect of sgk1 on ENaC activity in mpkCCDc14 cells. We used GSK650394 (42), a recently developed, highly selective inhibitor of sgk1, to assess the effect of sgk1 on basal and aldosterone-stimulated Isc in mpkCCDc14 cells. We then used amiloride to measure the amount of ENaC current remaining after GSK650394 treatment. Addition of GSK650394 to both sides of control cell monolayers inhibited Isc by 1.48 ± 0.29 μA/cm2 (38% of amiloride-sensitive Isc), whereas addition of GSK650394 to aldosterone-stimulated cell monolayers inhibited Isc by 5.48 ± 0.45 μA/cm2 (67% of amiloride-sensitive Isc) (Fig. 10B and supplemental Fig. S2).

FIGURE 10.

MβCD treatment attenuates GSK650394-inhibitable short circuit current (Isc) in aldosterone-stimulated mpkCCDc14 cells. A, representative traces of Isc recordings from mpkCCDc14 cells treated as indicated: vehicle control for 4 h; vehicle control for 4 h with 10 mm MβCD for 2 h; 1 μm aldosterone for 4 h; and 1 μm aldosterone for 4 h with 10 mm MβCD for 2 h. B, average percent of amiloride-sensitive Isc attributable to GSK650394 inhibition in cells exposed to treatment conditions, as indicated. *, p < 0.05. n = 21–24 cell monolayers per group. (GSK, GSK650394; Am, amiloride; Aldo, aldosterone).

We next examined the effect of MβCD treatment on GSK650394-inhibitable Isc in mpkCCDc14 cells. Addition of MβCD to the apical side of cell monolayers did not influence Rte in control or aldosterone-stimulated mpkCCDc14 cells, indicating that MβCD does not have a generalized toxic effect (data not shown). Addition of MβCD attenuated GSK650394-inhibitable activity, which was particularly apparent in aldosterone-stimulated cells (Fig. 10A). In aldosterone-stimulated cells, GSK650394 inhibited amiloride-sensitive Isc by 67%, but in the presence of MβCD, GSK650394 inhibited amiloride-sensitive Isc by 57% (Fig. 10B). Together, these findings suggest that the association of sgk1 with the apical membrane involves interactions with membrane cholesterol and that these interactions are important for the regulation of ENaC activity.

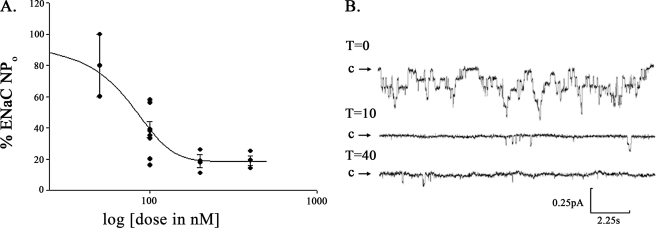

sgk1 Inhibitor GSK650394 Decreases ENaC Activity in Excised Inside-out Patches from the Apical Membrane of A6 Cells

We next used GSK650394 to evaluate whether there is a fraction of sgk1 that is functionally active at the apical cell membrane of A6 cells, a collecting duct-like cell line derived from X. laevis kidney. We performed single channel analysis in the cell-attached configuration of patches from the apical membrane of aldosterone-stimulated A6 cells treated with GSK650394, and we calculated that the IC50 value for the inhibitory effect of GSK650394 on ENaC activity was 71 nm. Approximately 18% of ENaC activity remained following a 10-min treatment with GSK650394 (400 nm) (Fig. 11).

FIGURE 11.

GSK650394 inhibits ENaC activity in cell-attached, single channel recordings of the apical membrane of aldosterone-stimulated A6 cells. A, GSK650394 inhibited ENaC activity with an IC50 of 71 nm in A6 cells. Cells were treated for 10 min with 50, 100, 200, and 400 nm GSK650394, expressed as log [dose] on the x axis. Single channel recordings were obtained in the cell-attached configuration, and the percentage (%) of ENaC activity is expressed on the y axis as the product of the number and open probability of ENaC channels (NPo). B, representative cell-attached patch clamp recording showing significant inhibition of ENaC current following sgk1 inhibition. During the recording period for the control (T = 0), 7 levels of channel activity could be detected; following 400 nm GSK650394 treatment for 10–40 min (T = 10, T = 40), ENaC NPo significantly decreased, and only two levels of channel activity were observed. Downward deflections from closed arrow (c) represent inward Na+ current. (pA, picoamperes; s, seconds).

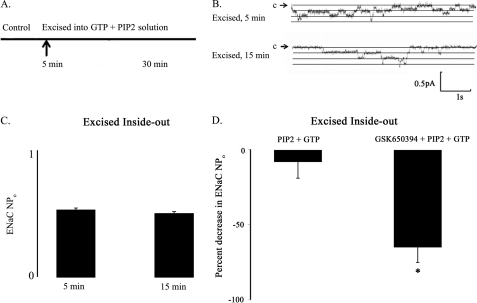

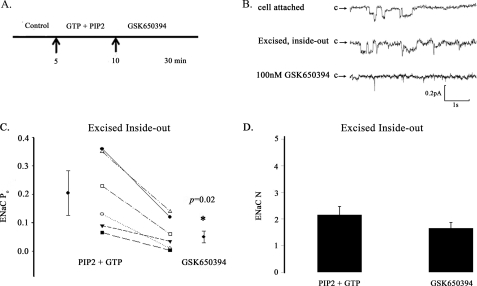

We reasoned that if active sgk1 associates with the apical cell membrane, then ENaC activity in excised inside-out membrane patches should still remain sensitive to GSK650394 inhibition. To test this hypothesis, we first excised cell-attached patches into a bath solution containing high K+ concentration, PIP2, and GTP to prevent channel run down (27). Fig. 12, A–C, shows that a bath solution containing 30 μm PIP2 and 100 μm GTP maintained ENaC channel activity and prevented channel run down for the duration of our experiments (up to 30 min). Importantly, excised patches from the apical membrane of aldosterone-stimulated A6 cells in a bath solution containing GSK650394, PIP2, and GTP showed significantly decreased ENaC activity (NPo) compared with patches in a bath solution containing PIP2 and GTP alone (Fig. 12D). In a series of independent cell-excised patches, we compared single channel recordings of inside-out patches from the apical membrane of aldosterone-stimulated A6 cells prior to and following treatment with GSK650394 (Fig. 13). We observed that GSK650394 significantly decreased the average ENaC Po from 0.20 ± 0.05 to 0.08 ± 0.02, p = 0.02 (Fig. 13C), without influencing the apparent number (N) of ENaC channels (Fig. 13D). These data indicate that active sgk1 resides in the inner surface of the apical membrane of aldosterone-stimulated collecting duct cells, where it may enhance ENaC Po.

FIGURE 12.

PIP2, GTP, and sgk1 activity maintain ENaC activity in excised inside-out patches from the apical membrane of aldosterone-stimulated A6 cells. A, cell-attached patches were excised (5 min after the control period) into high K+ solution supplemented with PIP2 and GTP to prevent channel rundown for up to 30 min. B, representative single channel recordings showing that incubation of excised membrane patches in a bath solution containing PIP2 and GTP prevents channel run down at 5 or 15 min after excision. Downward deflections from closed arrow (c) represent inward Na+ current. (pA, picoamperes; s, seconds). C, ENaC activity is expressed on the y axis as the product of number × open probability of ENaC channels (NPo) from excised patches (n = 4 patches per group). D, comparison of the percent decrease in ENaC NPo values from patches that were excised into a bath solution containing PIP2 and GTP versus a bath solution containing GSK650394, PIP2, and GTP. Single channel recordings were analyzed at similar time points 15–20 min following excision (n = 4 patches per group).

FIGURE 13.

GSK650394 inhibits ENaC open probability (Po) in excised inside-out patches from the apical membrane of aldosterone-stimulated A6 cells. A, cell-attached patches were excised (5 min after the control period) into high K+ solution supplemented with PIP2 and GTP to prevent channel run down for up to 30 min. 100 nm GSK650394 was added to the bath solution 5 min following membrane excision (10 min into the experiment). B, representative single channel recordings of the following conditions: cell-attached configuration (top trace); within 5 min of excising membrane into GTP + PIP2 solution (middle trace); and within 15–20 min of GSK650394 treatment (bottom trace). Downward deflections from closed arrow (c) represent inward Na+ current. (pA, picoamperes; s, seconds). C, GSK650394 decreases ENaC Po values in a cell-free system (inside-out patch clamp configuration) (n = 6 patches per group). D, GSK650394 does not influence ENaC number (N) values (inside-out patch clamp configuration) (n = 6 patches per group).

DISCUSSION

sgk1 has been localized to several subcellular compartments in a variety of cultured cells and tissues, perhaps a reflection of its role in regulating multiple cellular functions. Many of these localization studies, however, were performed in heterologous expression systems or in non-kidney cells or tissues. As a first step toward characterizing endogenous sgk1 function in kidney cells, we examined sgk1 subcellular localization in aldosterone-stimulated mpkCCDc14 cells. We found that up to 7% of the total pool of aldosterone-inducible sgk1 associated with the apical cell membrane of mpkCCDc14 cells, and this association was also observed in the principal cells of the cortical collecting duct of mouse kidney. In mpkCCDc14 cells, the association between sgk1 and the apical membrane could be disrupted by boiling in 2% SDS, suggesting that protein-protein interactions serve to bring sgk1 to the apical membrane. We found that sgk1 interacted with ENaC in kidney cells and that this interaction enhanced the association of sgk1 with the cell membrane. Additionally, when aldosterone-stimulated mpkCCDc14 cells were incubated with forskolin, a treatment known to enhance insertion of ENaC in the apical cell membrane, there was a corresponding increase in sgk1 expression in the apical surface fraction; conversely, when cells were treated with MβCD, a compound that disrupts insertion of ENaC channels in the apical membrane, there was a corresponding decrease in sgk1 expression in the apical surface fraction and a decrease in sgk1-dependent ENaC current. These experiments suggest that sgk1 is not only present in the apical surface fraction, but that expression of sgk1 there can be modulated by treatments known to alter ENaC expression at the apical cell membrane.

Although we have focused on an aldosterone-inducible form of sgk1 that associates with the apical membrane, it is important to note that aldosterone-inducible sgk1 is also present in the cytosol (Fig. 1) and at the basolateral membrane (Fig. 3). Indeed, a study by Canessa and co-workers (22) has previously documented localization of sgk1 to the basolateral membrane of rat kidney tubules, although the context under which sgk1 localizes to the basolateral membrane remains unclear. Some factors that could account for why sgk1 has been observed to be present in different subcellular locations by different groups are as follows: differences in the rodent species under study (rat versus mouse), differences in model systems under study (cultured cells versus whole animal), and differences in the antibodies used to probe for sgk1. Given that sgk1 is known to regulate ion transport in many different nephron segments (43), it is plausible that sgk1, in addition to being at the apical membrane, localizes to the basolateral membrane of collecting duct cells, where it could enhance Na+/K+-ATPase activity and thus increase transcellular Na+ transport (44–46).

A major goal of this study was to identify which subcellular locations of sgk1 are required for sgk1 regulation of ENaC activity in collecting duct cells. We hypothesized that, although sgk1 may not exclusively localize to the apical membrane, the association of sgk1 with the apical membrane could be an important determinant of sgk1 function in regulating ENaC activity. To test this, we excised inside-out membrane patches from the apical membrane of aldosterone-stimulated A6 collecting duct cells and found that specifically inhibiting membrane-associated sgk1 activity decreased ENaC Po. Although prior studies have demonstrated that recombinant sgk1 can stimulate ENaC activity in excised membrane patches (10, 11), to our knowledge ours is the first study to demonstrate that endogenous sgk1, localized to the apical cell membrane, is required to enhance ENaC Po in aldosterone-stimulated collecting duct cells.

Our data also indicate that depletion of membrane cholesterol by MβCD treatment disrupts the association of sgk1 with the apical membrane in mpkCCDc14 cells. Cholesterol and lipid rafts may be important for ENaC function in collecting duct cells (40, 41), possibly by direct insertion of ENaC in the apical cell membrane or by organizing a signaling platform to support functional interactions of ENaC with regulatory proteins such as sgk1. We found that MβCD treatment of aldosterone-stimulated mpkCCDc14 cells not only limited the association of sgk1 with the apical membrane but also decreased the stimulatory effect of sgk1 on ENaC activity. MβCD treatment, which has been shown to decrease cell surface ENaC expression in mpkCCDc14 cells (41), could limit the quantity of sgk1 that is brought to the apical membrane by decreasing the number of ENaC channels available at the cell surface to interact with sgk1. Whether the association of ENaC with pre-formed lipid rafts is required for sgk1 targeting to the cell surface, and whether sgk1 itself is found in lipid raft fractions will be the subject of future investigations.

Our findings suggest two models for sgk1 action at the apical cell membrane of collecting duct cells. These are not mutually exclusive and may involve sgk1 action at two different steps of ENaC regulation. In the first model, ENaC, possibly with cholesterol, recruits proteins into a signaling complex for regulating the ubiquitination and subsequent endocytosis of ENaC. In support of this, Nedd-4-2 has been demonstrated to associate with the cell surface only when ENaC is co-expressed (47), as we have found for co-expression of sgk1 and ENaC. Additionally, Nedd-4-2 has been localized together with caveolin-1 in lipid rafts, where it may down-regulate ENaC (48). Although the interaction of Nedd-4-2 and sgk1 at the plasma membrane remains to be investigated, the implication of such an interaction would be that ENaC could serve to bring specific proteins together at the cell surface to regulate ubiquitination and internalization of cell surface ENaC. Soundararajan et al. (49) have recently proposed that an ENaC regulatory complex containing Nedd-4-2, Raf-1, GILZ, and sgk1 exists in transfected HEK293T cells. A similar ENaC regulatory complex containing Nedd-4-2, Raf-1, and GILZ was observed in mpkCCDc14 cells, but the investigators did not examine whether sgk1 was also part of this complex or whether this complex was present at the apical membrane.

The second model involves interaction of sgk1 with ENaC, possibly in a different signaling complex, which could function to activate electrically silent channels at the plasma membrane or to increase channel insertion (10). Because this model does not involve the retrieval of ENaC from the cell membrane, a mechanism of ENaC regulation that has been ascribed to Nedd-4-2 function, this model does not require Nedd-4-2. Indeed, in the absence of heterologous expression of Nedd-4-2, sgk1 has been shown to stimulate ENaC activity by activating silent channels already present at the plasma membrane or by enhancing delivery of ENaC to the plasma membrane (50). We found that local inhibition of endogenous sgk1 in excised membrane patches acutely decreased the Po of ENaC, suggesting that sgk1 can regulate ENaC without necessarily influencing the number of ion channels at the cell surface. We propose that the association of sgk1 with ENaC at the plasma membrane represents a Nedd-4-2-independent mechanism for sgk1 regulation of ENaC, in which sgk1 interacts with ENaC to activate ENaC channels or to stimulate delivery of active ENaC channels to the apical surface of collecting duct cells. This proposed mechanism would be in line with studies in cell-based systems (10, 50–52) and mouse models (53–55) that support the notion that aldosterone, and possibly sgk1, can regulate ENaC activity through Nedd-4-2-independent pathways. Whether cholesterol also influences sgk1-mediated regulation of ENaC remains to be determined, but there is evidence that cholesterol-rich domains or lipid rafts are involved in the delivery of ENaC to the cell surface (41) and that cholesterol is required for direct activation of ENaC by sgk1 at the plasma membrane (11).

In conclusion, our data demonstrate that sgk1 associates with the apical membrane through interactions with ENaC and that the association of sgk1 with the cell membrane is functionally important. The involvement of ENaC and the plasma membrane as a site for sgk1 action suggests two separate mechanisms for regulating ENaC, one involving retrieval of ENaC from the apical membrane by a complex of regulatory proteins, including Nedd-4-2, and the other involving activation of ENaC at the apical membrane through a process that may be independent of Nedd-4-2. These two mechanisms are not mutually exclusive and may operate at two different steps in the pathway of ENaC regulation. In both models, the interaction between sgk1 and ENaC is the primary determinant for the specificity of sgk1 action in enhancing ENaC-mediated Na+ transport in aldosterone-stimulated collecting duct cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Alain Vandewalle (INSERM) for providing mpkCCDc14 cells for our experiments. We thank Dr. Tom Kleyman (University of Pittsburgh) for the ENaC subunit expression vectors. We acknowledge the technical assistance of Preston Goodson (Emory University). We also thank Dr. Vivek Bhalla (Stanford University), Dr. Michael B. Butterworth (University of Pittsburgh), and Dr. Orson W. Moe (University of Texas, Southwestern Medical Center) for valuable discussions.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants K08-DK-073487 (to A. C. P.), R00-HL-09222601 (to M. N. H.), P30-DK-079328 (to J. Z.), and T32-DK07357-26A1 (to P. P. K.). This work was also supported by Stanford University Dean's Fellowship award (to S. V. T.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1 and S2.

- ENaC

- epithelial sodium channel

- MβCD

- methyl-β-cyclodextrin

- PIP2

- phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate.

REFERENCES

- 1. Chen S. Y., Bhargava A., Mastroberardino L., Meijer O. C., Wang J., Buse P., Firestone G. L., Verrey F., Pearce D. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 2514–2519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Náray-Fejes-Tóth A., Canessa C., Cleaveland E. S., Aldrich G., Fejes-Tóth G. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 16973–16978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Park J., Leong M. L., Buse P., Maiyar A. C., Firestone G. L., Hemmings B. A. (1999) EMBO J. 18, 3024–3033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kobayashi T., Cohen P. (1999) Biochem. J. 339, 319–328 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Debonneville C., Flores S. Y., Kamynina E., Plant P. J., Tauxe C., Thomas M. A., Münster C., Chraïbi A., Pratt J. H., Horisberger J. D., Pearce D., Loffing J., Staub O. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 7052–7059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Snyder P. M., Olson D. R., Thomas B. C. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 5–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bhalla V., Daidié D., Li H., Pao A. C., LaGrange L. P., Wang J., Vandewalle A., Stockand J. D., Staub O., Pearce D. (2005) Mol. Endocrinol. 19, 3073–3084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ichimura T., Yamamura H., Sasamoto K., Tominaga Y., Taoka M., Kakiuchi K., Shinkawa T., Takahashi N., Shimada S., Isobe T. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 13187–13194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Liang X., Peters K. W., Butterworth M. B., Frizzell R. A. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 16323–16332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Diakov A., Korbmacher C. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 38134–38142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Krueger B., Haerteis S., Yang L., Hartner A., Rauh R., Korbmacher C., Diakov A. (2009) Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 24, 605–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Arteaga M. F., Wang L., Ravid T., Hochstrasser M., Canessa C. M. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 11178–11183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bogusz A. M., Brickley D. R., Pew T., Conzen S. D. (2006) FEBS J. 273, 2913–2928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cordas E., Náray-Fejes-Tóth A., Fejes-Tóth G. (2007) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 292, C1971–C1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Engelsberg A., Kobelt F., Kuhl D. (2006) Biochem. J. 399, 69–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Loffing J., Zecevic M., Féraille E., Kaissling B., Asher C., Rossier B. C., Firestone G. L., Pearce D., Verrey F. (2001) Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 280, F675–F682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brickley D. R., Mikosz C. A., Hagan C. R., Conzen S. D. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 43064–43070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Leong M. L., Maiyar A. C., Kim B., O'Keeffe B. A., Firestone G. L. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 5871–5882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Maiyar A. C., Leong M. L., Firestone G. L. (2003) Mol. Biol. Cell 14, 1221–1239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Náray-Fejes-Tóth A., Helms M. N., Stokes J. B., Fejes-Tóth G. (2004) Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 217, 197–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Buse P., Tran S. H., Luther E., Phu P. T., Aponte G. W., Firestone G. L. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 7253–7263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Alvarez de la Rosa D., Coric T., Todorovic N., Shao D., Wang T., Canessa C. M. (2003) J. Physiol. 551, 455–466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bens M., Vallet V., Cluzeaud F., Pascual-Letallec L., Kahn A., Rafestin-Oblin M. E., Rossier B. C., Vandewalle A. (1999) J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 10, 923–934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pao A. C., McCormick J. A., Li H., Siu J., Govaerts C., Bhalla V., Soundararajan R., Pearce D. (2007) Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 292, F1741–F1750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rajagopal M., Pao A. C. (2010) Hypertension 55, 1123–1128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rajagopal M., Kathpalia P. P., Thomas S. V., Pao A. C. (2011) Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol., in press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yue G., Malik B., Yue G., Eaton D. C. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 11965–11969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Flores S. Y., Loffing-Cueni D., Kamynina E., Daidié D., Gerbex C., Chabanel S., Dudler J., Loffing J., Staub O. (2005) J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 16, 2279–2287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Arteaga M. F., Alvarez de la Rosa D., Alvarez J. A., Canessa C. M. (2007) Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 2072–2080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Arteaga M. F., Coric T., Straub C., Canessa C. M. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 4459–4464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Raikwar N. S., Snyder P. M., Thomas C. P. (2008) Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 295, F1440–F1448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang J., Barbry P., Maiyar A. C., Rozansky D. J., Bhargava A., Leong M., Firestone G. L., Pearce D. (2001) Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 280, F303–F313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hughey R. P., Bruns J. B., Kinlough C. L., Harkleroad K. L., Tong Q., Carattino M. D., Johnson J. P., Stockand J. D., Kleyman T. R. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 18111–18114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hughey R. P., Bruns J. B., Kinlough C. L., Kleyman T. R. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 48491–48494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hughey R. P., Mueller G. M., Bruns J. B., Kinlough C. L., Poland P. A., Harkleroad K. L., Carattino M. D., Kleyman T. R. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 37073–37082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lu C., Pribanic S., Debonneville A., Jiang C., Rotin D. (2007) Traffic 8, 1246–1264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Morris R. G., Schafer J. A. (2002) J. Gen. Physiol. 120, 71–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Snyder P. M. (2000) J. Clin. Invest. 105, 45–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Butterworth M. B., Edinger R. S., Johnson J. P., Frizzell R. A. (2005) J. Gen. Physiol. 125, 81–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hill W. G., An B., Johnson J. P. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 33541–33544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hill W. G., Butterworth M. B., Wang H., Edinger R. S., Lebowitz J., Peters K. W., Frizzell R. A., Johnson J. P. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 37402–37411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sherk A. B., Frigo D. E., Schnackenberg C. G., Bray J. D., Laping N. J., Trizna W., Hammond M., Patterson J. R., Thompson S. K., Kazmin D., Norris J. D., McDonnell D. P. (2008) Cancer Res. 68, 7475–7483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lang F., Böhmer C., Palmada M., Seebohm G., Strutz-Seebohm N., Vallon V. (2006) Physiol. Rev. 86, 1151–1178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Alvarez de la Rosa D., Gimenez I., Forbush B., Canessa C. M. (2006) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 290, C492–C498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Setiawan I., Henke G., Feng Y., Böhmer C., Vasilets L. A., Schwarz W., Lang F. (2002) Pflugers Arch. 444, 426–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zecevic M., Heitzmann D., Camargo S. M., Verrey F. (2004) Pflugers Arch. 448, 29–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zhou R., Patel S. V., Snyder P. M. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 20207–20212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lee I. H., Campbell C. R., Song S. H., Day M. L., Kumar S., Cook D. I., Dinudom A. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 12663–12669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Soundararajan R., Melters D., Shih I. C., Wang J., Pearce D. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 7804–7809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Alvarez de la Rosa D., Zhang P., Náray-Fejes-Tóth A., Fejes-Tóth G., Canessa C. M. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 37834–37839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Shigaev A., Asher C., Latter H., Garty H., Reuveny E. (2000) Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 278, F613–F619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Auberson M., Hoffmann-Pochon N., Vandewalle A., Kellenberger S., Schild L. (2003) Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 285, F459–F471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Dahlmann A., Pradervand S., Hummler E., Rossier B. C., Frindt G., Palmer L. G. (2003) Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 285, F310–F318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bertog M., Cuffe J. E., Pradervand S., Hummler E., Hartner A., Porst M., Hilgers K. F., Rossier B. C., Korbmacher C. (2008) J. Physiol. 586, 459–475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Pradervand S., Vandewalle A., Bens M., Gautschi I., Loffing J., Hummler E., Schild L., Rossier B. C. (2003) J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 14, 2219–2228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.