Abstract

The development of solid state nanopores1–7, inspired by their biological counterparts8–15, shows great potential for the study of single macromolecules16–21. Applications such as DNA sequencing6,22,23 and exploration of protein folding6 will require understanding and control of the dynamics of a molecule’s interaction with the pore, but DNA capture by a solid state nanopore is not well understood24–26. By recapturing individual molecules soon after they pass through a nanopore, we reveal the mechanism by which double stranded DNA enters the pore. Observed recapture rates and times agree with solutions of a drift-diffusion model. Electric forces draw DNA to the pore over micron distances, and, upon arrival at the pore, molecules begin translocation almost immediately. Repeated translocation of the same molecule improves measurement accuracy, offers a way to probe chemical transformations and internal dynamics of macromolecules on sub-millisecond time and sub-micron length scales, and demonstrates the ability to trap, study, and manipulate individual macromolecules in solution.

In this letter, we present a detailed view of the dynamics of single molecule capture by a solid state nanopore on millisecond time scales and sub-micron length scales. We monitor the current through a nanopore and detect blockages in the current when DNA passes the pore, partially obstructing the current path. After translocating a solid state nanopore, a single DNA molecule is allowed to continue to move under the influence of the pore’s proximal electric field and diffusive forces for a preset time duration. The electric force is then reversed to bring the same molecule back to, and then through, the nanopore. Both passages are detected by a blockage of the ionic current through the pore. In previous work with solid state nanopores 16,17,19–21,25,27, the capture dynamics could not be studied directly because the location of a molecule was unknown until it entered the nanopore. Here, the molecule is known to be inside the pore at both ends of a measured time interval, the length of which directly reveals the essential characteristics of the molecular motions involved.

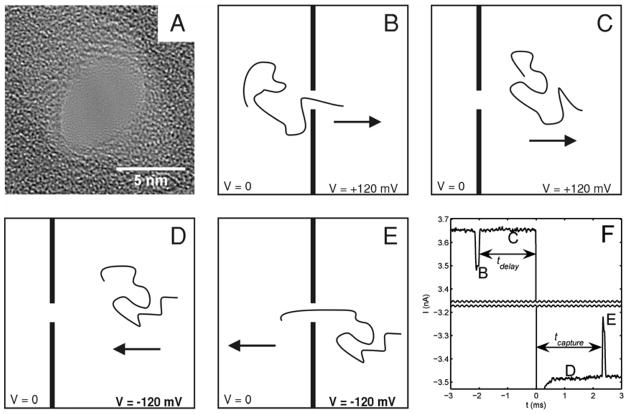

A 5 by 7 nm nanopore in a ~20 nm thick SiN membrane (Fig. 1a) joined 2 reservoirs of aqueous 1 M KCl maintained at pH 8 by 10 mM TE buffer. Electrical contact to the reservoirs was made with Ag/AgCl electrodes. An equimolar mixture of 6 and 4 kilobase-pair (kbp) double stranded DNA fragments was added to the reservoir contacted by the ground electrode. The other reservoir was biased at +120mV. Ionic current blockages were monitored to detect the passage of DNA through the pore16. To probe the dynamics of molecules near the pore, after a molecule was detected passing through the pore (Fig. 1b), the bias voltage was maintained at 120 mV for a programmed time, tdelay, between 2 and 32 ms (Fig. 1c), then reversed to −120 mV for 500 ms (Figs. 1d and 1e). After 500 ms, the voltage was returned to +120 mV, regardless of when or if a molecule translocated in the reverse direction28. Bates and coworkers have previously used fast voltage switching to probe escape of ssDNA from a protein pore13.

Figure 1.

Overview of the recapture experiment. A) TEM of the SiN nanopore used. B–E) Schematic representation of the experiment. The arrow represents the direction of the electric force on the DNA molecule. B) A single DNA molecule passes through the nanopore in the forward direction. C) After passing through the pore, the molecule moves away from the pore under the influence of the electric field for a fixed delay time. D) The field is reversed, and the molecule moves towards the pore. E) The molecule passes through the pore in the reverse direction. F) A representative current trace for an experiment with a 2 ms delay before voltage reversal. A gap of 6.6 nA is omitted from the middle of the trace. The letters mark the correspondence between the current trace and the schematic illustrations of molecular motion. Molecules cannot be detected passing the pore during the first 300 μs after voltage reversal while the capacitance of the nanopore/flow cell system charges.

Figure 1f shows a representative current trace. A molecule is detected translocating the pore in the forward direction by an ionic current blockage (B), 2 ms are allowed to elapse (C), the voltage is reversed (D), and the molecule is then seen to translocate the pore in the reverse direction by a second current blockage (E). Immediately after translocating the pore and prior to the voltage reversal, the molecule is driven away from the pore by the near-pore electric field and random thermal forces. We vary tdelay, the time between the first translocation and the voltage reversal, and measure tcapture, the time until the molecule reenters the pore after voltage reversal, to probe the behavior of the molecules at different distances from the nanopore. These times are indicated in Figure 1f.

All electronic signals due to forward and reverse passages of the molecule through the pore are analyzed individually. They show a characteristic blockage current and unfolded translocation time that scales appropriately with the length of the molecules16. Based on the structure of these signals (discussed in detail in the supporting material online), we discriminate between 4 kbp and 6 kbp molecules16,21. Within the limits imposed on length discrimination by the statistical spread in translocation times and the sticking of molecules to the pore during translocation, we verify that if a 4 kbp molecule passes the pore in the forward direction, the recaptured molecule is also 4 kbp, and likewise for 6 kbp molecules.

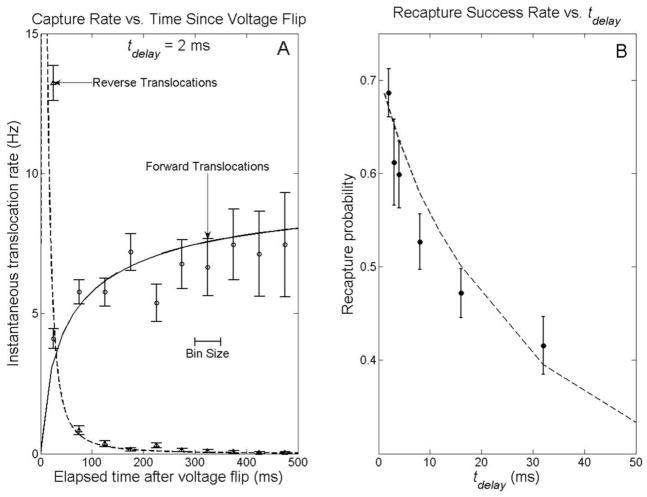

Figure 2a shows the rate at which molecules are captured by the pore vs. time after voltage bias reversal for tdelay = 2 ms. In the forward direction, the capture rate of molecules is suppressed just after the voltage bias is switched from negative to positive because the molecules near the pore have been repelled by the reversed voltage for the previous 500 ms. By contrast, in the reverse direction, 87% of returning molecules arrive within 50 ms after the bias is turned negative. The high recapture rate just after the voltage is reversed is due to the return of the molecule that previously passed the pore in the forward direction and triggered the voltage reversal. Molecules that pass through the pore and are not rapidly recaptured form a background recapture rate two orders of magnitude lower than the rates discussed above.

Figure 2.

Capture rates and recapture probabilities. A) Instantaneous capture rates for the 2 ms delay experiment. Each point represents the average rate at which molecules entered the pore in the surrounding 50 ms time interval (e.g. the point at 25 ms represents the rate between 0 and 50 ms after the voltage flip). The solid (forward-biased capture) and dashed (recapture) lines represent the predictions of the drift-diffusion model discussed in the text. B) Fraction of molecules recaptured within 500 ms of voltage reversal, as a function of time delay between forward translocation detection and voltage reversal. The dashed line represents the prediction of the drift-diffusion model discussed in the text.

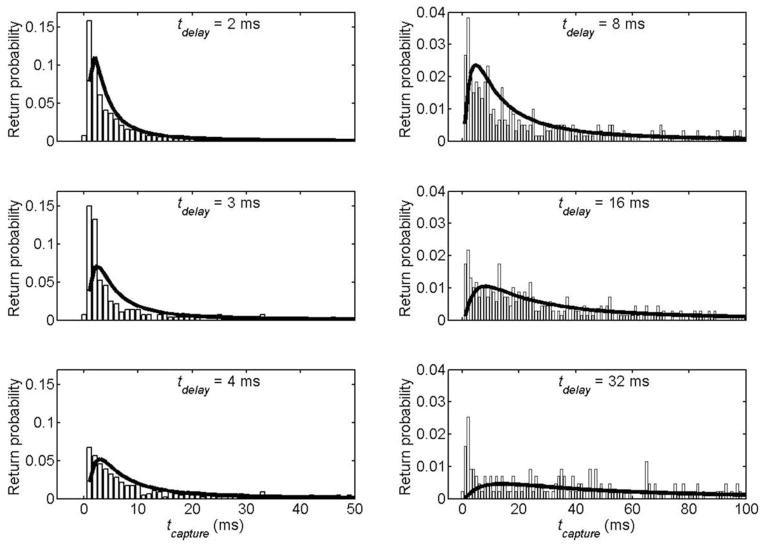

Figure 2b shows the recapture success rate, the fraction of forward translocations followed by a reverse translocation at any tcapture within the 500 ms voltage reversal window, as a function of tdelay. Figure 3 shows histograms of tcapture for each tdelay collected for many events. For tdelay < 4 ms, most molecules arrive at the pore and are translocated through in less than 10 ms. Both the distribution of return times and the overall recapture success rate depend strongly on the delay before reversal.

Figure 3.

Capture time histograms for returning molecules for different delays prior to voltage reversal. Each bar represents the fraction of forward translocated molecules recaptured in the 1 ms interval centered about the corresponding time. Note the axes have different scales for the left and right histograms. The bold lines represents the predictions of the drift-diffusion model discussed in the text.

We compare our observations with a theoretical model in which the DNA’s motion is determined by an electric force on the charged phosphate backbone and random thermal forces due to collisions with water molecules. Competition between thermal and electrical forces leads to a characteristic length beyond which the latter dominates the former.

On average, diffusion drives a molecule away from the pore, located at r = 0. We can define the radial “diffusion velocity,” vd (R,t), as , the expected value of the rate of change of a diffusing molecule’s distance from the pore,

| (1) |

where

| (2) |

so,

| (3) |

where D is the DNA’s diffusion constant.

An electrical current density J results from an electric field E, given by Ohm’s law, J = σ E, where σ is the electrical conductivity of the ionic solution. At distances much greater than the diameter of the pore, the current density and electric field will be (hemi)spherically symmetric, and related to the experimentally observed current, I, through the biased nanopore by .

DNA in free solution is known to move with a constant electrophoretic mobility μ29,30. If we ignore the conformational degrees of freedom of the DNA molecule and assume its charge is distributed symmetrically about its center of mass, located at r, the radial “electrophoretic velocity,” ve (r,t) is given by .

Comparing ve to vd, we see there is a characteristic distance, , beyond which the average velocity away from the pore due to diffusion is greater than the electrophoretic velocity31. For our experimental conditions, this length is 940 nm for 4kbp dsDNA and 1.2 μm for 6kbp dsDNA32.

Assuming a (hemi)spherically symmetric distribution of non-interacting dsDNA molecules, the volume concentration, c(r,t) of DNA obeys the drift-diffusion transport equation

| (4) |

where the minus sign is used when the electrical force is directed away from the pore and the plus sign when this force is towards it. This equation can be solved numerically, with appropriate boundary and initial conditions, to model the voltage reversal experiment (see supporting online text). With no free parameters, this drift-diffusion model predicts the correct ratios between recapture success rates at different tdelay (Fig. 2b) and the relative distributions of tcapture for all tdelay (Fig. 3), but overstates the actual number of molecules recaptured at all tcapture and tdelay. A single parameter fit, which scales the number of recaptures predicted by an overall factor of 70% for all tcapture and tdelay, makes a good match to the observed recapture success rates and capture time distributions. The dashed lines in figures 2 and 3 represent this fit, with no other free parameters. In the forward direction, the same equation models the capture of molecules initially driven into the bulk by an electric force directed away from the pore. The solid line in figure 2a is a single parameter (the steady state flux of molecules through the pore) fit of the drift diffusion model to the observed forward capture rates.

Approximations made in the model, including assuming a spherically symmetric electrical field on all length scales33 and ignoring the possibility of nonspecific binding of the DNA to the membrane surface, could account for the missing 30% of returning molecules. At long tdelay, we see a higher return rate at short times than predicted by the model. This could be due either to molecules that stick briefly to the membrane surface and are not driven as far away, or to extended configurations of molecules that leave parts of them far closer to the pore than their centers of mass. We have disregarded effects of electroosmotic flow, which, due to the negatively charged surface of the pore, would oppose the DNA’s electrophoretic motion.

Numerical analysis of the drift-diffusion equation shows that, of the molecules that return to the pore from distances less than the characteristic distance L, discussed above, most do so within a time L2/2D. (Here, 220 ms for the 4kb DNA and 450 ms for the 6kb.) A molecule that starts at 0.4L (400–500 nm) has an 85% chance (neglecting the overall 70% prefactor) of translocation in this time. (See supplemental information for further details of the calculations.)

We also probe the time required for DNA to enter the nanopore. tcapture consists of treturn, the time it takes a molecule to arrive at the pore and tent, the time it takes a molecule to enter after arriving. treturn is predicted by the drift diffusion model discussed above; its distribution depends strongly on tdelay. tent is not included in the drift-diffusion model and does not depend on tdelay, as it involves the behavior of the molecule after it has already reached the pore. The histograms of tcapture presented in figure 4 depend strongly on tdelay in the same manner as the drift-diffusion calculations of treturn, which indicates the recapture time is determined mainly by treturn. The recapture rate is also highest immediately after the voltage is reversed, which is inconsistent with the notion24,34 that the molecule requires a significant amount of time post arrival to enter the pore. Hence, upon arriving at the pore, the typical molecule in this experiment translocates in less than a millisecond.

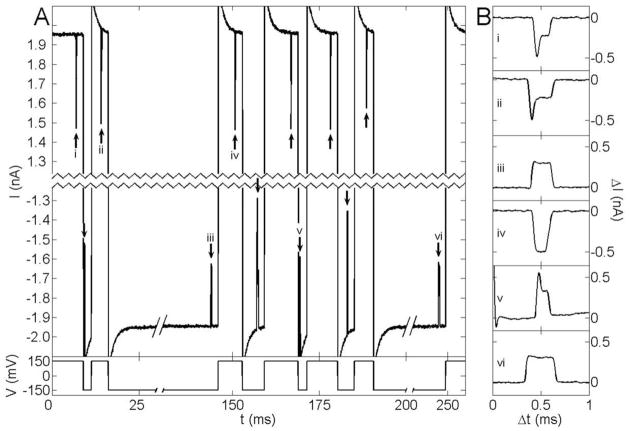

Figure 4.

Current vs. time traces from a single molecule trapping experiment. A) A single 10 kbp dsDNA molecule passes the pore twelve times over 250 ms. The main panel shows the current through the pore vs. time. For clarity, 2.4 nA are excised from the center of the current axis, and the time axis has also been compressed. The short pulses (marked with arrows) show current being blocked as the molecule passes through the pore. 2 ms after each passage, the voltage bias (plotted below the current) is reversed. As in Figure 1, the molecule is initially captured at positive voltage bias. The exponential settling at the beginning of each transition results from charging of the membrane capacitance. B) Expanded current traces resulting from separate passages of the molecule through the pore. Each is labeled by a Roman numeral that identifies the portion of the current trace in A from which it was taken.

Besides exploring molecular dynamics, there are other advantages and applications to recapturing molecules that have passed the pore in the forward direction, including convincing evidence that an electronic signal corresponds to a molecule translocating the pore. This provides a way to distinguish molecular signals from background noise on a single molecule basis and is valid even for polydisperse samples and analytes17,18 for which no sensitive assay like PCR exists. Recapturing the molecule would also allow one to measure changes in molecules (e.g. hybridization changes, changes in protein conformation, stripping of binding proteins) induced by passage through the nanopore. Immediate voltage reversal can also be used to study the conformational dynamics of a polymer. The Zimm relaxation time35 for 4kb dsDNA is 300 μs and 610 μs for 6kb dsDNA; in this experiment the configuration of the molecule during the reverse translocation was not influenced by the previous translocation. However, with an increase in viscosity20 and/or molecule length, the relaxation time can be extended sufficiently to enable us to probe and possibly manipulate the non equilibrium conformation induced in the molecule by passage through the nanopore and to explore the influence of a molecule’s initial conformation on translocation through the pore.

Extending the single recapture experiments presented so far to repeatedly recapture the same molecule realizes a new kind of single molecule trap based on nanopore technology. Figure 4 presents the electronic signals from such a trap (details of the setup are available in the online supplement). In this particular experiment (in a new nanopore), a single 10 kbp dsDNA molecule from a mixture of 5.4 and 10 kbp molecules is passed back and forth twelve times over a period of 250 ms. (Single molecules have so far been trapped for as many as 22 passes over 500 ms.) Current blockage induced by the passage of the molecule through the nanopore reveals information about the molecule (length, conformation, and interaction with the pore16) and, with triggered voltage reversals, provides the feedback mechanism to maintain the trap. Thus, biologically interesting molecules can be trapped, detected, and analyzed in free solution without any labels or chemical modifications. Repeated electronic interrogation of a single molecule potentially provides a means for greatly enhancing the accuracy with which each molecule can be characterized by a nanopore and allows measurement over time of dynamical properties such as the molecule’s conformation and chemical state.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work as supported by NIH/NGRI grant # 5 R01 HG003703. Some fabrication was done at Harvard University’s Center for Nanoscale Systems, with the assistance of Drs. David Bell, Yuan Lu, and J.D. Deng. We thank Eric Brandin for preparing the molecules for the trapping experiment, Stan Coutreau and Paul Testa for machining assistance, Prof. Jiali Li, Prof. Daniel Branton, Prof. Sergey Bezrukov, David Hoogerheide, and Dimitar Vlassarev for useful discussions, and Dr. Michael Biercuk for valuable suggestions on the manuscript.

References

- 1.Li J, et al. Ion-beam sculpting at nanometre length scales. Nature. 2001;412:166–169. doi: 10.1038/35084037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Storm AJ, Chen JH, Ling XS, Zandbergen HW, Dekker C. Electron-beam-induced deformations of SiO2 nanostructures. Journal of Applied Physics. 2005;98 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu MY, Krapf D, Zandbergen M, Zandbergen H, Batson PE. Formation of nanopores in a SiN/SiO2 membrane with an electron beam. Applied Physics Letters. 2005;87 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen P, et al. Atomic layer deposition to fine-tune the surface properties and diameters of fabricated nanopores. Nano Letters. 2004;4:1333–1337. doi: 10.1021/nl0494001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lo CJ, Aref T, Bezryadin A. Fabrication of symmetric sub-5 nm nanopores using focused ion and electron beams. Nanotechnology. 2006;17:3264–3267. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dekker C. Solid-state nanopores. Nature Nanotechnology. 2007;2:209–215. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin CR, Siwy ZS. CHEMISTRY: Learning Nature’s Way: Biosensing with Synthetic Nanopores. Science. 2007;317:331–332. doi: 10.1126/science.1146126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bezrukov SM, Vodyanoy I, Parsegian VA. Counting Polymers Moving through a Single-Ion Channel. Nature. 1994;370:279–281. doi: 10.1038/370279a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kasianowicz JJ, Brandin E, Branton D, Deamer DW. Characterization of individual polynucleotide molecules using a membrane channel. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93:13770–13773. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gu LQ, Braha O, Conlan S, Cheley S, Bayley H. Stochastic sensing of organic analytes by a pore-forming protein containing a molecular adapter. Nature. 1999;398:686–690. doi: 10.1038/19491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bayley H, Cremer PS. Stochastic sensors inspired by biology. Nature. 2001;413:226–230. doi: 10.1038/35093038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meller A, Nivon L, Branton D. Voltage-driven DNA translocations through a nanopore. Physical Review Letters. 2001;86:3435–3438. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.86.3435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bates M, Burns M, Meller A. Dynamics of DNA molecules in a membrane channel probed by active control techniques. Biophysical Journal. 2003;84:2366–2372. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)75042-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ambjornsson T, Apell SP, Konkoli Z, Di Marzio EA, Kasianowicz JJ. Charged polymer membrane translocation. Journal of Chemical Physics. 2002;117:4063–4073. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henrickson SE, Misakian M, Robertson B, Kasianowicz JJ. Driven DNA transport into an asymmetric nanometer-scale pore. Physical Review Letters. 2000;85:3057–3060. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.3057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li JL, Gershow M, Stein D, Brandin E, Golovchenko JA. DNA molecules and configurations in a solid-state nanopore microscope. Nature Materials. 2003;2:611–615. doi: 10.1038/nmat965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han AP, et al. Sensing protein molecules using nanofabricated poresn. Applied Physics Letters. 2006;88 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fologea D, Ledden B, McNabb DS, Li J. Electrical characterization of protein molecules by a solid-state nanopore. Applied Physics Letters. 2007;91:053901–3. doi: 10.1063/1.2767206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fologea D, et al. Detecting single stranded DNA with a solid state nanopore. Nano Letters. 2005;5:1905–1909. doi: 10.1021/nl051199m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fologea D, Uplinger J, Thomas B, McNabb DS, Li JL. Slowing DNA translocation in a solid-state nanopore. Nano Letters. 2005;5:1734–1737. doi: 10.1021/nl051063o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Storm AJ, et al. Fast DNA translocation through a solid-state nanopore. Nano Letters. 2005;5:1193–1197. doi: 10.1021/nl048030d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rhee M, Burns MA. Nanopore sequencing technology: research trends and applications. Trends in Biotechnology. 2006;24:580–586. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lagerqvist J, Zwolak M, Di Ventra M. Fast DNA sequencing via transverse electronic transport. Nano Letters. 2006;6:779–782. doi: 10.1021/nl0601076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muthukumar M. Polymer translocation through a hole. Journl of Chemical Physics. 1999;111:10371–10374. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen P, et al. Probing single DNA molecule transport using fabricated nanopores. Nano Letters. 2004;4:2293–2298. doi: 10.1021/nl048654j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keyser UF, et al. Direct force measurements on DNA in a solid-state nanopore. Nature Physics. 2006;2:473–477. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Storm AJ, Chen JH, Zandbergen HW, Dekker C. Translocation of double-strand DNA through a silicon oxide nanopore. Physical Review E. 2005;71 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.71.051903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Materials and methods are available in the supporting material online.

- 29.Nkodo AE, et al. Diffusion coefficient of DNA molecules during free solution electrophoresis. Electrophoresis. 2001;22:2424–2432. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(200107)22:12<2424::AID-ELPS2424>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stellwagen NC, Gelfi C, Righetti PG. The free solution mobility of DNA. Biopolymers. 1997;42:687–703. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(199711)42:6<687::AID-BIP7>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jonathan Nakane MA, Marziali Andre. Evaluation of nanopores as candidates for electronic analyte detection. ELECTROPHORESIS. 2002;23:2592–2601. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(200208)23:16<2592::AID-ELPS2592>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.In contrast, for 100 bp ssDNA and a (e.g. protein) pore with 100 pA of current, this length is less than one nanometer, and we do not expect recapture of recently translocated molecules by voltage reversal would be possible,

- 33.Hall JE. Access Resistance of a Small Circular Pore. Journal of General Physiology. 1975;66:531–532. doi: 10.1085/jgp.66.4.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Panwar AS, Kumar S. Time scales in polymer electrophoresis through narrow constrictions: A Brownian dynamics study. Macromolecules. 2006;39:1279–1289. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grosberg AY, Khokhlov AR. Statistical Physics of Macromolecules. AIP Press; Woodbury, NY: 1994. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.