Abstract

The monogamous prairie vole displays developmental sensitivity to early pharmacological manipulation in a number of species-typical social behaviors. The long-term consequences of altering the neonatal dopamine system are not well characterized. The present study examined whether early manipulation of the dopamine system, a known mediator of adult prairie vole social behavior, during neonatal development would affect adult aggressive and attachment behaviors. Eight-day-old pups were given a single treatment with either 1mg/kg SKF38393 (D1 agonist), quinpirole (D2 agonist), SCH23390 (D1 antagonist), eticlopride (D2 antagonist), or saline vehicle. As adults, subjects received tests for intrasexual aggression and partner preference. Activation of D1-like receptors in pups impaired partner preference formation but had no effect on aggression. Other neonatal treatments had no effect on their behavior as adults. To determine if D1 activation in pups induced changes in dopamine receptor expression, we performed autoradiography on striatal tissue from a second cohort of saline and SKF38393 treated animals. Although sex differences were observed, we found no treatment differences in D1 or D2 receptor binding in any striatal sub-region. This study shows that exposure to a single early pharmacological alteration of dopamine receptor activity may have long-term effects on the social behavior of prairie voles.

Keywords: prairie vole, monogamy, development, dopamine, nucleus accumbens

Introduction

The prairie vole displays a number of behaviors indicative of a monogamous social organization including pair-bonding and biparental care (Carter and Getz, 1993). Pair-bonding behaviors are reliably studied in the laboratory using a variety of behavioral assays including partner preference testing and tests for selective aggression (Getz et al., 1981; Williams et al., 1992; Williams et al., 1994). Although these social behaviors are characteristic of the general population they are sensitive to environmental manipulations experienced early in development. This has been demonstrated by studies using neonatal manipulations of neurotransmitter systems already known to modulate adult social interactions such as oxytocin (OT) and vasopressin (AVP; as reviewed in Carter et al., 2009). For example, a single neonatal injection of OT has long-lasting effects on partner preference formation in a dose-dependent and sex-specific manner (Carter, 2003; Bales and Carter, 2003b; Bales et al., 2007; Carter et al., 2008), with some effects on intrasexual aggression (Bales and Carter, 2003a). Moreover, repeated exposure to AVP over the first postnatal week leads to a dose dependent increase in intrasexual aggression in both sexes, without any alteration of partner preference formation (Stribley and Carter, 1999). These studies indicate that early life manipulations of neural systems known to regulate adult social behavior can have dramatic and lifelong impacts on future social behavior.

Another neural system known to play a critical role in the regulation pair bond behavior in adult prairie voles is the mesolimbic dopamine (DA) system (Wang et al., 1999; Gingrich et al., 2000; Liu and Wang, 2003; Aragona et al., 2003,, 2006). Specifically, partner preference formation is facilitated by D2-like receptor activation, and inhibited by D1-like receptor activation (Wang et al., 1999; Aragona et al., 2006), within the shell of the nucleus accumbens (NAc; Aragona et al., 2006). Further, Aragona et al., (2006) demonstrated that the striking shift from general affiliation to selective aggression toward novel conspecifics is at least in part mediated by an up-regulation of D1-like receptors within the nucleus accumbens. Taken together, these studies indicate that D2 receptors are involved in the induction of partner preference associated with the formation of the pair-bond, whereas activation of D1-like receptors inhibits partner preference formation and promote pair bond maintenance.

However, unlike OT and AVP, the effects of DA manipulations early in development on adult social behavior have received less attention. Previous research from our lab has found that infanticidal and anxiety-like behaviors are reduced in females neonatally exposed to the D2 antagonist eticlopride (Hostetler et al., 2010). There has been no study of developmental alterations of dopaminergic systems on either partner preference formation or adult-directed aggression in prairie voles. Here we look at the developmental consequences of a single neonatal pharmacological manipulation of DA receptors on adult social behaviors and DA receptor binding. We broadly hypothesized that, similar to the role of DA receptors on pair-bonding, neonatal exposure to a D2 agonist would increase affiliative behaviors while the D1 agonist would inhibit partner preference formation as well as increase aggression. To test these hypotheses, we administered two behavioral assays of sociality: partner preference test and intrasexual aggression test with a novel same-sex conspecific. We found that only activation of D1-like receptors early in development caused behavioral changes once voles were adults. To determine if these changes were mediated by long-term changes in DA receptors, we performed receptor autoradiography for striatal D1-like and D2-like receptor binding on adult brains in subjects that were administered DA drugs early in development.

Methods

Subjects

The prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster) used in Experiment I were from an outbred stock originally captured in Illinois and reared at the University of California, Davis. Colony rooms were maintained under controlled temperature, humidity, and light cycles (14L:10D). Food (Purina high-fiber rabbit diet) and water were freely available. All procedures were approved and annually reviewed by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of California, Davis.

The prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster) used in Experiment II were from an outbred stock at the University of Michigan originally obtained from a colony at Florida State University. All animals were maintained on a 14L:10D light cycle in temperature controlled rooms. Purina rabbit chow and water were freely available.

Experiment I: Effects of neonatal DA receptor manipulation on adult social behavior

Pups were sexed and toe-cliped for identification within 24 h of birth, then returned to their natal cage. Male and female pups were randomly assigned one of the following treatments: saline (vehicle control), or 1 mg/kg SKF38393 (D1 agonist), quinpirole (D2 agonist), SCH23390 (D1 antagonist), or eticlopride (D2 antagonist) in 25μl volume. Age of treatment, drugs, and dosage were based on previous work with prairie voles and neonatal rodent studies (as described in Hostetler et al., 2010). On postnatal day (P)8, pups were removed from their parents and treatment was administered i.p. with a gas-tight Hamilton syringe. Animals were weaned at 21 days of age and housed in same sex pairs in standard mouse cages (27 cm long × 16 cm wide × 13 cm high) until testing as adults.

As adults, all subjects received an elevated plus maze and alloparental care test (as reported in Hostetler et al., 2010), and a juvenile affiliation test (data not shown). At approximately P80, each subject was given a intrasexual aggression test, a partner preference test, and second intrasexual aggression test on three consecutive days. Sample sizes for each test varied, and are reported in the Results section.

Intrasexual Aggression Test I

Subjects were given a dyadic encounter test for intrasexual aggression (Winslow et al., 1993; Harper and Batzli, 1997; Bowler et al., 2002; Bales and Carter, 2003a). The test subject was placed in a novel cage with an unfamiliar stimulus animal of the same sex and approximate age and size. Stimulus animals were prescreened for aggression and only non-aggressive animals were used. The testing cage was novel for both the subject and stimulus animal. The test was videotaped for five minutes and scored using Behavior Tracker 1.0 (www.behaviortracker.com) software by an experimentally blind observer. All tests occurred between 0900h and 1200h.

Scored behaviors were divided into four categories: aggression, defensive behavior, social contact, and other behavior. Aggressive behaviors were lunges (frequency) and chases (frequency and duration). Defensive behavior was scored as the frequency and duration of upright rearing posture directed at the stimulus animal. Affiliative behaviors included physical contact (duration) and allogrooming (duration). Displacement behaviors scored included autogrooming (duration), and exploratory cage rearing (duration).

All data were analyzed using non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis tests. Sex differences in each behavior were examined for control animals only. Additionally, males and females were separately analyzed for treatment effects on each behavior. Significance was set at p<0.05.

Partner Preference Test

Within 24 h of the first intrasexual aggression test, subjects were housed in standard mouse cages with a novel opposite sex partner. Male subjects were housed with stimulus females for 24 h, and female subjects were housed with stimulus males for 6 h. These sex-specific pairing times are sufficient for partner preference formation in the absence of mating (DeVries and Carter, 1999). Pairing times occurred in the afternoon for males and mornings for females, with subsequent partner preference testing occurring between 1500h and 1900h. Mating was not expected, as female prairie voles are induced ovulators (Carter et al., 1980). Additionally, therefore stage of estrus was not a consideration. If mating occurred during testing (by either subjects or stimulus animals), the subject was removed from analysis. This resulted in two subjects being removed from analysis.

Following the cohabitation period, subjects were given a partner preference test. The partner preference test chamber consisted of a central cage (27 cm long × 16 cm wide × 13 cm high) joined by hollow tubes to two parallel identical cages, each housing a stimulus animal (Williams et al., 1992, 1994). The test subject was free to move throughout the apparatus, whereas stimulus animals were loosely tethered within each parallel cage and had no direct contact with each other. The familiar partner and an unfamiliar conspecific stranger of the opposite sex were used as stimulus animals. The test was videotaped for three hours using a time-lapse video recording system (5:1 compression) and scored using Behavior Tracker 1.0 software by an experimentally blind observer. Behaviors recorded were cage location and side-by-side contact with each stimulus animal.

A contact ratio was calculated as (Contact Time with Partner)/(Contact Time with Partner + Contact Time with Stranger). If the subject did not spend time in contact with either subject, the contact ratio was set as 0. We also looked at the total time spent in contact with either the partner or stranger, defined as: (Contact Time with Partner + Contact Time with Stranger). The contact ratio and total contact time were examined with mixed model ANOVA with treatment, sex, and a sex*treatment interaction as fixed factors, followed by Dunnett’s post hoc tests.

Intrasexual Aggression Test II

Following partner preference testing, subjects were housed alone with a cotton nestlet overnight. Access to bedding material such as a cotton nestlet has been shown to buffer corticosterone response to social isolation (Kim and Kirkpatrick, 1996). The morning (0900h to 1200h) following partner preference tests, each subject was given a second intrasexual aggression test with a novel same sex conspecific, as described above. This second aggression test, when compared to pre-partner preference aggression data, allows a comparison in changes in aggressive behavior following partner preference formation (Bales and Carter, 2003a). Accordingly, only subjects that were given partner preference tests were analyzed. Additionally, some data were lost due to loss of videotape data. Therefore, sample sizes for analysis of Test II are smaller than Test I.

To examine changes in behaviors between the first and second intrasexual aggression tests difference scores were calculated as (Time/Frequency of Behavior in Test II) − (Time/Frequency of Behavior in Test I). The resulting score would be positive if a given behavior increased in Test II, negative if the behavior decreased in Test II, and zero if there was no change in behavior. Treatment effects in the difference score were then analyzed separately for males and females via Kruskal-Wallis tests.

Experiment II: Effects of neonatal DA receptor manipulation on adult striatal DA receptors

Based on the behavioral results from Experiment I, we selected specific treatments for the collection of postmortem tissue. A second cohort was given pharmacological manipulations during development and tissue collected as adults. There were two treatment groups for each sex: 1 mg/kg SKF38393 or saline vehicle control. All neonatal procedures were performed as described in Experiment I and were performed by SLH, who had also performed the majority of neonatal manipulations for Experiment I while a student at UC-Davis. At 21 days of age, subjects were weaned and housed in same sex sibling pairs until 60 days of age at which they were sacrificed by live decapitation. Brains were removed, immediately frozen on dry ice, and stored at −80°C. All procedures were in accordance with the animal care guidelines set by the University of Michigan.

Receptor autoradiography

Brain tissue was sectioned at 15μm in thickness on a freezing cryostat and mounted onto glass slides at 90μm intervals. The slides were stored in moisture-resistant conditions at −80°C until the time of assay, with the exception of a 24h period when the slides were defrosted but not moisture contaminated.

For D1-like and D2-like receptor binding, slides were twice rinsed in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) for 10 minutes and then incubated in buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 120 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2 and [125I]-SCH23982 (D1 ligand) or [125I]-Idosulpride (D2 ligand; PerkinElmer, Waltham, Massachusets, USA). In addition, 50 nM ketanserin (RBI, Natick, Massachusetts, USA) was added to the D1 ligand solution to preclude binding to 5-HT2 receptors. Following an incubation period (150 minutes for D1-like receptors and 90 minutes for D2-like receptors) at room temperature, sections were fixed in fresh cold buffer containing 0.1% paraformaldyhyde, rinsed in cold buffer several times, dipped in ice cold ddH2O, and dried under a stream of cool air. Nonspecific binding was defined by incubating adjacent sections in SCH23390, the D1-like receptor antagonist, or raclopride, the D2-like receptor antagonist, which displaced specific binding. Slides were exposed to BioMax MR film (Kodak, Rochester, New York, USA) for 6 hrs.

The regions of interest (ROI) were the dorsal striatum (DS), NAc core, and NAc shell at 1.6 mm from bregma. This coronal region was chosen because it has previously been shown to be a site of dopaminergic regulation of pair bond behavior in prairie voles (Aragona et al., 2006). Moreover, because specific sub-regions of nucleus accumbens shell are known to differ anatomically as well as functionally the shell was separated into medial (mShell), ventral (vShell), and lateral (lShell) regions (Usuda et al., 1998; Voorn et al., 2004). An increase in D1-like receptor density was expected in the medial and ventral shell because these are known sites of action of pharmacological manipulation of D1-like receptors in prairie voles (Aragona et al., 2006). No change was expected in the lateral shell, which is anatomically and functionally more similar to the dorsal striatum (Usuda et al., 1998; Voorn et al., 2004), because D1-like receptor density does not differ in the dorsal striatum of sexually naïve and pair bonded prairie voles or between monogamous and non-monogamous vole species (Aragona et al., 2006). Optical density was measured for each ROI using the NIH ImageJ software and examined with mixed model ANOVA with treatment, sex, and a sex*treatment interaction as fixed factors.

Results

Independence of behavior in the partner preference and aggression tests

The three behavioral tests used in this experiment were specifically chosen to examine the effects of neonatal dopamine receptor treatments on different aspects of prairie vole behavior. Consistent with this assumption, the proportion of time spent in contact with the partner in the partner preference test was not significantly correlated with time spent engaging in any behavior during the first aggression test (n=96: max r = 0.11, NS) or duration difference scores following the second aggression test (n=83: r = 0.22, p=0.0504 for aggressive behavior; max r = 0.08, NS, for other behaviors). Although the correlation in difference score for aggressive behaviors approaches significance, the correlation accounts for less than 5% of the variance in contact ratio. As such, the behavioral tests performed in this study appear to represent independent, orthogonal measures without shared variance and were therefore analyzed without statistical correction for multiple measures.

Intrasexual Aggression Test I

Means, standard errors, and sample sizes for all recorded behaviors are presented for control animals in Table 1. The levels of behavior exhibited in the intrasexual aggression test were similar to those previously published (Getz, 1962; Harper and Batzli, 1997; Stribley and Carter, 1999; Bales and Carter, 2003a). Aggressive behavior (lunging and chasing) was low and did not differ between males and females. Defensive behavior (defensive rearing) was more frequent than aggressive behaviors, but were still displayed at low levels. Of the behaviors measured, the majority of time was spent engaging in displacement behaviors (autogrooming and exploratory cage rearing). Sex differences in behaviors were compared between saline controls only. There were no significant sex differences in any behaviors (see Table 1 for statistics).

Table 1.

Means (±standard errors) for the frequency and durations (in seconds) of behaviors during Intrasexual Aggression Test I. There were no sex differences in any behaviors measured (statistics and p-values listed in table).

| Treatment | males

|

females

|

Statistics and p-values (df=1) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| saline | eticlopride | quinpirole | SCH23390 | SKF38393 | saline | eticlopride | quinpirole | SCH23390 | SKF38393 | ||

| n | 14 | 13 | 12 | 12 | 10 | 13 | 9 | 11 | 11 | 9 | |

| Aggressive | |||||||||||

| frequency | 1.0 ± 0.46 | 2.77 ± 1.22 | 1.0 ± 0.41 | 2.42 ± 1.07 | 1.80 ± 0.98 | 1.31 ± 0.44 | 1.11 ± 0.89 | 4.36 ± 1.64 | 1.36 ± 0.82 | 2.22 ± 1.61 | U=0.69, p=0.41 |

| duration (s) | 0.50 ± 0.50 | 1.15 ± 0.80 | 0 ± 0 | 1.42 ± 0.69 | 1.70 ± 1.32 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 1.25 ± 1.25 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.33 ± 0.24 | U=0.93, p=0.34 |

| Defensive | |||||||||||

| frequency | 4.78 ± 1.14 | 3.77 ± 0.92 | 8.08 ± 2.39 | 4.0 ± 1.69 | 3.80 ± 1.94 | 4.54 ± 1.47 | 4.56 ± 1.34 | 4.25 ± 1.48 | 3.82 ± 1.03 | 3.78 ± 1.40 | U=0.12, p=0.73 |

| duration (s) | 2.35 ± 0.61 | 2.38 ± 0.87 | 5.83 ± 1.91 | 4.75 ± 3.26 | 4.20 ± 2.36 | 2.77 ± 1.05 | 2.67 ± 1.14 | 2.83 ± 1.53 | 1.73 ± 0.62 | 2.67 ± 1.50 | U=0.62, p=0.80 |

| Social | |||||||||||

| duration (s) | 11.7 ± 4.28 | 18.3 ± 9.28 | 16.33 ± 6.17 | 15.6 ± 8.39 | 28.6 ± 9.44 | 10.6 ± 3.19 | 17.0 ± 6.81 | 14.2 ± 7.17 | 4.36 ± 1.76 | 2.0 ± 0.83 | U=0.02, p=0.90 |

| Displacement | |||||||||||

| duration (s) | 64.9 ± 12.5 | 79.5 ± 11.0 | 53.3 ± 8.5 | 59.7 ± 11.6 | 59.9 ± 7.9 | 64.5 ± 11.3 | 58.7 ± 15.9 | 59.3 ± 8.96 | 82.1 ± 10.2 | 51.8 ± 8.19 | U=0.03, p=0.87 |

For analysis of treatment effects, sample size ranged from 9 to 14 subjects per group (each sex analyzed separately for treatment effects). There were no significant differences based on treatment for any behavior in either sex. Neither frequency (males: U=5.21, df=4, NS; females: U=0.32, df=4, NS) nor duration (males: U=6.56, df=4, NS; females: U=5.47, df=4, NS) of aggressive behaviors was affected by any neonatal treatment.

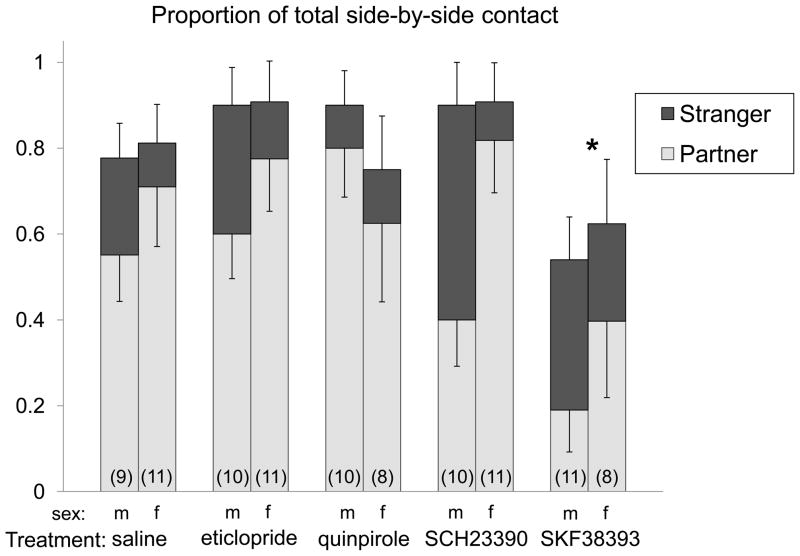

Partner Preference Test

Subjects given the D1 agonist SKF38393 as pups showed an inhibition of partner preference formation when they were tested as adults. Sample sizes are reported in Figure 1. There was a significant main effect of treatment on the contact ratio (time spent in side contact with the partner divided by total side contact; F4,94=2.71, p<0.05), with SKF38393 treated subjects spending proportionately less time in contact with the partner when compared to saline controls (p<0.05; Figure 1). There were no effects of any other treatment on the contact ratio. There was no difference in the time spent in total contact with either partner or stranger (F4,94=1.37, NS).

Figure 1.

Proportion of time spent in contact with the partner (light grey bars) or stranger (dark grey bars) relative to total contact time during Partner Preference Test, with males on the left and females on the right in each treatment pair. Sample sizes for each group are presented in parentheses. SKF treated subjects spent proportionately less time in contact with the partner when compared to saline controls. *Indicates significant effect of treatment on time spent with partner compared to saline controls, p<0.05.

Intrasexual Aggression Test II

Neonatal treatment did not affect behavior in the intrasexual aggression test following cohabitation and partner preference testing. Means, standard errors, and sample sizes for difference scores are presented for all animals in Table 2. Sample size ranged between 7 and 11 subjects for each group and are presented in Table 2 (each sex analyzed separately for treatment effects).

Table 2.

Means (±standard errors) for the Difference Scores of intrasexual aggression behaviors. Positive values of the Test II Difference Scores represent an increase in behavior from Test I to Test II, negative values indicate a decrease.

| Treatment | males

|

females

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| saline | eticlopride | quinpirole | SCH23390 | SKF38393 | saline | eticlopride | quinpirole | SCH23390 | SKF38393 | |

| n | 10 | 11 | 9 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 7 | 10 | 8 |

| Aggressive | ||||||||||

| frequency | 0.5 ± 0.58 | 2.82 ± 1.50 | 9.44 ± 5.65 | 2.50 ± 2.36 | −0.22 ± 1.09 | 0.87 ± 0.97 | 2.89 ± 1.31 | −1.71 ± 2.07 | 3.40 ± 1.78 | 2.37 ± 2.96 |

| duration (s) | −0.70 ± 0.70 | 0.91 ± 1.39 | 6.44 ± 4.89 | −0.90 ± 1.08 | −1.0 ± 0.67 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 1.22 ± 0.99 | −1.86 ± 2.21 | 1.20 ± 1.20 | 0.50 ± 0.96 |

| Defensive | ||||||||||

| frequency | −3.5 ± 1.33 | 2.18 ± 1.12 | −4.89 ± 2.90 | 0.80 ± 2.46 | 0.89 ± 3.24 | 2.0 ± 2.65 | −0.67 ± 2.10 | 1.43 ± 2.73 | 1.90 ± 1.48 | 4.0 ± 3.60 |

| duration (s) | −2.30 ± 0.92 | 0.45 ± 0.77 | −2.33 ± 1.53 | −3.30 ± 3.61 | −2.11 ± 3.26 | 0.50 ± 2.27 | −.89 ± 1.61 | 2.14 ± 2.60 | 6.0 ± 4.82 | 2.0 ± 2.78 |

| Social | ||||||||||

| duration (s) | −4.10 ± 5.77 | −17.0 ± 11.7 | −13.2 ± 8.52 | −12.3 ± 10.5 | −23.8 ± 9.38 | −3.75 ± 6.19 | −9.44 ± 9.03 | −4.57 ± 6.82 | −2.50 ± 2.24 | −1.88 ± 0.85 |

| Displacement | ||||||||||

| duration (s) | 17.9 ± 13.8 | −20.3 ± 15.8 | −7.89 ± 12.8 | −6.50 ± 14.2 | −9.67 ± 12.6 | 3.13 ± 17.1 | −24.2 ± 19.3 | 30.1 ± 19.9 | −38.7 ± 10.2 | 1.63 ± 13.2 |

There was an overall treatment effect in females only on the change in duration spent engaging in displacement behaviors (U=9.96, df=4, p<0.05), but there were no significant differences between saline control subjects and any of the treatment groups. There were no other significant effects of neonatal treatment on the change scores for any behavior, including aggression (male frequency: U=5.11, df=4, NS, duration: U=2.87, df=4, NS; female frequency: U=1.12, df=4, NS, duration: U=7.56, df=4, NS).

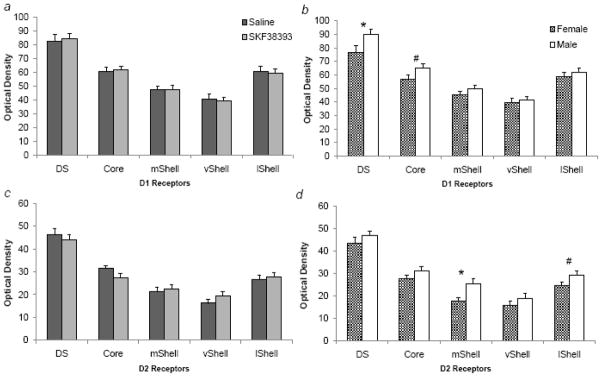

D1 and D2 receptor autoradiography

Sample sizes for autoradiography per saline and SKF38393 treatment, respectively, were: 11 and 8 (males), and 10 and 7 (females). Neonatal treatment with SKF38393 did not affect either D1-like or D2-like receptor binding in the striatum, although there were sex differences (Figure 2). For D1-like receptors, there were significant effects of sex in both the DS (F1,34=4.62, p<0.059) and NAc core (trend only: F1,34=3.89, p=0.057), with males showing higher receptor binding in both regions (Figure 2b). Males also had higher D2-like receptor binding in the medial (F1,34=8.73, p<0.01) and lateral (trend only: F1,34=3.29, p=0.078) divisions of the NAcc shell (Figure 2d).

Figure 2.

Optical density of dopamine receptor autoradiography in the striatum by neonatal treatment (pooled by sex; a & c) and sex (pooled by treatment; b & d). There were no differences in any region between subjects treated with saline (dark bars) or SKF38393 (light bars). Males (white bars) had significantly higher receptor- and region-specific binding than females (hatched bars; * indicates p<0.05, # indicates p<0.10).

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that exposure to a single manipulation of the dopamine system early in development has the ability to significantly alter the propensity of an adult prairie vole to form a partner preference later in life. As hypothesized, early treatment with the D1 agonist SKF38393 inhibited partner preference formation in both males and females. However, there were no treatment effects on interaction with a novel same-sex conspecific either before or following heterosexual cohabitation. These findings build on previous work showing that D1-like receptors play an inhibitory role in partner preference formation.

A single neonatal treatment with the D1 agonist SKF38393 reduced partner preference formation in adult prairie voles (Figure 1). These results are of particular interest given that acute administration of SKF38393 into the NAc also prevents partner preference formation in adults (Aragona et al., 2006). Following a two-week cohabitation, D1 receptors are upregulated in the shell of the NAc. This increase in receptors is correlated with aggression toward opposite-sex strangers. This aggression may function to prevent the formation of a partner preference for a new individual, and maintain the integrity of the original pair bond. There is also evidence in adult prairie voles that the NAc is responsive to pharmacological treatment, as three days of repeated amphetamine administration increases D1 mRNA and receptors in the NAc of females (Young et al., 2011) and males (Liu et al., 2010), respectively. For these reasons, we hypothesized that the lack of partner preference formation seen in D1 agonist-treated subjects may be due to an upregulation of the D1-like receptors in the NAc. To test this hypothesis, we measured D1 receptors in the striatum of a separate cohort of neonatally treated SKF38393 and saline animals. We hypothesized that D1 receptors would be increased in the SKF38393 subjects, specifically in the NAc shell. The hypothesis was not supported, as there was no effect of early neonatal treatment on D1 receptors in any of the striatal regions examined (Figure 2a). However, this is not completely unsurprising when considering the lack of treatment effects on aggressive behaviors. The upregulation of D1 receptors following partner preference formation is associated with increased aggression toward a novel conspecific (Aragona et al., 2006). We also found no treatment effects on D2 receptor binding in the striatum. There are a number of remaining possible mechanisms for the inhibition of partner preference in SKF38393-treated subjects, including altered synthesis or release of DA. Elucidating the mechanisms of this developmental effect warrants future research. A caveat to interpreting the results of Experiments I and II is that each study was performed on voles from separate institutions and founder colonies. Therefore, it is possible that neonatal treatments may produce different behavioral and molecular outcomes in these two populations. However, we believe this is ruled out by the fact that the colonies show identical and species-typical behaviors with respect to mating, social affiliation, and pair bonding.

Although neonatal treatment did not alter DA receptors in the striatum, we did observe sex differences in receptor binding, and these were region-specific. Males had higher D1 receptor binding in the dorsal striatum and NAc core (Figure 2b), and higher D2-receptor binding in the medial and lateral regions of the NAc shell (Figure 2d). The presence of sex differences is consistent with available literature on DA receptor distributions in prairie voles, although only a limited few regions have been studies in this species. Males have lower D1 receptors in the medial prefrontal cortex than females, but there are no sex differences in D2 receptors (Smeltzer et al., 2006).

Male prairie voles also have less D1 receptor binding in the NAc shell compared to male meadow voles (Aragona et al., 2006). It is relevant to note that both Smeltzer et al. (2006) and Aragona et al. (2006) found significant species differences in DA receptor distributions between prairie voles and non-monogamous vole species, suggesting that available studies on receptor distributions in other laboratory species are unlikely to be appropriate comparisons for prairie voles. Our present findings provide further support for region-specific sex differences in dopamine receptors of prairie voles, but a systematic comparison of D1 and D2 receptor distribution across sexes and species would provide more complete information on the prairie vole DA system.

Partner preference formation was blocked in both males and females treated with the D1 agonist SKF38393. This result is similar to previous work showing that acute SKF38393 inhibits partner preference formation (Aragona et al., 2006). These effects are highly specific, as neonatal exposure to SKF38393 did not alter behavior in any other tests, including elevated plus maze, alloparental care (Hostetler et al., 2010), juvenile affiliation (Hostetler and Bales, unpublished), and intrasexual aggression (Tables 1 and 2). A shortcoming of the current study is that we only examined whether treatments inhibited partner preference formation, but did not look at whether partner preference formation was improved by any of the conditions. For example, it is possible that neonatal exposure to a D2 agonist would facilitate partner preference formation. However, tests for facilitation and inhibition must be performed on separate subjects. Given the numerous behavioral tests each animal received before the partner preference testing, an additional cohort of subjects and stimulus animals is beyond the scope of the current study. Therefore it is difficult to conclude that only a D1 agonist has developmental effects on pair-bonding behavior in this species. Regardless, this and previous research (Hostetler et al., 2010) suggests that the DA receptor system may have broad and significant organizational effects on behavior during development.

The efficacy of DA receptor signaling is high at birth, and declines over the postnatal period (Kim et al., 2002), suggesting that DA receptors are particularly responsive to pharmacological treatments during the first week of life. Our data support this, but understanding the development of this system with a clinical application is of particular relevance. Although we looked at receptor specific manipulations, it would be interesting to explore whether other treatments that are less receptor targeted and more directly relevant to humans may lead to similar effects. For example, cocaine acts as a DA reuptake inhibitor, leading to more available DA in the extracellular space and a corresponding increase in D1 receptor stimulation, leading to potentially similar effects on social behavior as our SKF38393 treated animals. Johns et al. (1998) found that chronic exposure to cocaine over the gestational period leads to alterations of social and aggressive behaviors in adult rats. Our research has shown that a single manipulation of the DA system can have long-term effects on social behavior during the neonatal period, modeling the late prenatal period in humans. This significant effect of a single injection suggests that future research should explore the effects of both acute and chronic developmental exposure of cocaine and other dopaminergic drugs on adult social behaviors in the prairie vole. The present findings indicate that the prairie vole is an excellent animal model for understanding the effects of early dopaminergic manipulations on the development of selective social behavior.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH MH073022 (to KLB) and NSF CAREER 0953106 (to BJA).

We thank Julie Van Westerhuyzen and Cindy Clayton D.V.M. for animal assitance. This research was supported by NIH MH073022 (to KLB and C. Sue Carter) and NSF CAREER 0953106 (to BJA).

References

- Aragona BJ, Liu Y, Curtis T, Stephan FK, Wang ZX. A critical role for nucleus accumbens dopamine in partner-preference formation in male prairie voles. J Neurosci. 2003;23:3483–3490. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03483.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aragona BJ, Liu Y, Yu YJ, Curtis JT, Detwiler JM, Insel TR, Wang ZX. Nucleus accumbens dopamine differentially mediates the formation and maintenance of monogamous pair bonds. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:133–139. doi: 10.1038/nn1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bales KL, Carter CS. Sex differences and developmental effects of oxytocin on aggression and social behavior in prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster) Horm Behav. 2003a;44:178–184. doi: 10.1016/s0018-506x(03)00154-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bales KL, Carter CS. Developmental exposure to oxytocin facilitates partner preferences in male prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster) Behav Neurosci. 2003b;117:854–859. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.117.4.854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bales KL, van Westerhuyzen JA, Lewis-Reese AD, Grotte ND, Lanter JA, Carter CS. Oxytocin has dose-dependent developmental effects on pair-bonding and alloparental care in female prairie voles. Horm Behav. 2007;52:274–279. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowler CM, Cushing BS, Carter CS. Social factors regulate female-female aggression and afiliation in prairie voles. Physiol Behav. 2002;76:559–566. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(02)00755-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter CS. Developmental consequences of oxytocin. Physiol Behav. 2003;79:383–397. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(03)00151-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter CS, Getz LL. Monogamy and the prairie vole. Sci Am. 1993;268:100–106. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0693-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter CS, Getz LL, Gavish L, McDermott JL, Arnold P. Male-related pheromones and the activation of female reproduction in the prairie vole (Microtus ochrogaster) Biol Reprod. 1980;23:1038–045. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod23.5.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter CS, Boone EM, Bales KL. Early experience and the developmental programming of oxytocin and vasopressin. In: Bridges RS, editor. Neurobiology of the Parental Brain. New York: Academic Press; 2008. pp. 417–434. [Google Scholar]

- Carter CS, Boone EM, Pournajafi-Nazarloo H, Bales KL. Consequences of early experiences and exposure to oxytocin and vasopressin are sexually dimorphic. Dev Neurosci. 2009;31:332–341. doi: 10.1159/000216544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVries AC, Carter CS. Sex differences in temporal parameters of partner preference in prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster) Can J Zoolog. 1999;77:885–889. [Google Scholar]

- Getz LL. Aggressive behavior of the meadow and prairie voles. J Mammal. 1962;43:351–358. [Google Scholar]

- Getz LL, Carter CS, Gavish L. The mating system of the prairie vole Microtus ochrogaster: field and laboratory evidence for pair-bonding. Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 1981;8:189–194. [Google Scholar]

- Gingrich B, Liu Y, Cascio C, Wang ZX, Insel TR. Dopamine D2 receptors in the nucleus accumbens are important for social attachment in female prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster) Behav Neurosci. 2000;114:173–183. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.114.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper SJ, Batzli GO. Are staged dyadic encounters useful for studying aggressive behavior of arvicoline rodents? Can Journal Zoolog. 1997;75:1051–1058. [Google Scholar]

- Hostetler CM, Harkey SL, Bales KL. D2 antagonist during development decreases anxiety and infanticidal behavior in adult female prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster) Behav Brain Res. 2010;210:127–130. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns JM, Noonan LR, Zimmerman LI, McMillen BA, Means LW, Walker CH, Lubin DA, Meter KE, Nelson CJ, Pedersen CA, Mason GA, Lauder JM. Chronic cocaine treatment alters social/aggressive behavior in Sprague-Dawley rat dams and in their prenatally exposed offspring. Ann N Y Acad Sci USA. 1998;846:399–404. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DS, Froelick GJ, Palmiter RD. Dopamine-dependent desensitization of dopaminergic signaling in the developing mouse striatum. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9841–9849. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-22-09841.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JW, Kirkpatrick B. Social isolation in animals models of relevance to neuropsychiatric disorders. Biol Psychiat. 1996;40:918–922. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00546-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Wang ZX. Nucleus accumbens oxytocin and dopamine interact to regulate pair bond formation in female prairie voles. Neuroscience. 2003;121:537–544. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00555-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Aragona BJ, Young KA, Dietz DM, Kabbaj M, Mazei-Robison M, Nestler EJ, Wang Z. Nucleus accumbens dopamine mediates amphetamine-induced impairment of social bonding in a monogamous rodent species. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:1217–1222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911998107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeltzer MD, Curtis JT, Aragona BJ, Wang Z. Dopamine, oxytocin, and vasopressin receptor binding in the medial prefrontal cortex of monogamous and promiscuous voles. Neurosci Lett. 2006;394:146–151. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stribley JM, Carter CS. Developmental exposure to vasopressin increases aggression in adult prairie voles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:12601–12604. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usuda I, Tanaka K, Chiba T. Efferent projections of the nucleus accumbens in the rat with special reference to subdivision of the nucleus: biotinylated dextran amine study. Brain Res. 1998;797:73–93. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00359-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voorn P, Vanderschuren L, Groenewegen H, Robbins T, Pennartz C. Putting a spin on the dorsal-ventral divide of the striatum. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:468–474. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZX, Yu GZ, Cascio C, Liu Y, Gingrich B, Insel TR. Dopamine D2 receptor-mediated regulation of partner preferences in female prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster): A mechanism for pair bonding? Behav Neurosci. 1999;113:602–611. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.113.3.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JR, Catania KC, Carter CS. Development of partner preferences in female prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster): The role of social and sexual experience. Horm Behav. 1992;26:339–349. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(92)90004-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JR, Insel TR, Harbaugh CR, Carter CS. Oxytocin centrally administered facilitates formation of a partner preference in female prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster) J Neuroendocrinol. 1994;6:247–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1994.tb00579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winslow JT, Hastings N, Carter CS, Harbaugh CR, Insel TR. A role for central vasopressin in pair bonding in monogamous prairie voles. Nature. 1993;365:545–548. doi: 10.1038/365545a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young KA, Liu Y, Gobrogge KL, Dietz DM, Wang H, Kabbaj M, Wang Z. Amphetamine alters behavior and mesocorticolimbic dopamine receptor expression in the monogamous female prairie vole. Brain Res. 2011;1367:213–222. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.09.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]