Abstract

Perceptual learning is an important means for the brain to maintain its agility in a dynamic environment. Top-down focal attention, which selects task-relevant stimuli against competing ones in the background, is known to control and select what is learned in adults. Still unknown, is whether the adult brain is able to learn highly visible information beyond the focus of top-down attention. If it is, we should be able to reveal a purely stimulus-driven perceptual learning occurring in functions that are largely determined by the early cortical level, where top-down attention modulation is weak. Such an automatic, stimulus-driven learning mechanism is commonly assumed to operate only in the juvenile brain. We performed perceptual training to reduce sensory eye dominance (SED), a function that taps on the eye-of-origin information represented in the early visual cortex. Two retinal locations were simultaneously stimulated with suprathreshold, dichoptic orthogonal gratings. At each location, monocular cueing triggered perception of the grating images of the weak eye and suppression of the strong eye. Observers attended only to one location and performed orientation discrimination of the gratings seen by the weak eye, while ignoring the highly visible gratings at the second, unattended, location. We found SED was not only reduced at the attended location, but also at the unattended location. Furthermore, other untrained visual functions mediated by higher cortical levels improved. An automatic, stimulus-driven learning mechanism causes synaptic alterations in the early cortical level, with a far-reaching impact on the later cortical levels.

Keywords: Adult cortical plasticity, Attention-gated learning, Binocular rivalry, Boundary contour, Interocular imbalance, Ocular dominance, Stereopsis, Stimulus-driven learning

1. Introduction

The investigation capitalizes on our recent study that used a push-pull training protocol to reduce human observer’s sensory eye dominance (SED1), which is largely caused by an unbalanced interocular inhibition (Ooi and He, 2001; Schor, 1991; Xu et al., 2010a). Binocular vision such as stereopsis and binocular competition are adversely affected when the interocular inhibition is unbalanced (Schor, 1991; Xu et al., 2010a). For example, when the two eyes are stimulated with a pair of dichoptic orthogonal gratings, the grating presented to the strong eye receives less inhibition and is more likely to be perceived (dominant). For the two eyes to have equal chance of seeing its image (50% predominance), either the contrast of the grating in the strong eye has to be reduced, or the contrast of the grating in the weak eye is increased. We define the contrast value of the grating at this point of neutrality as the “balance contrast”.

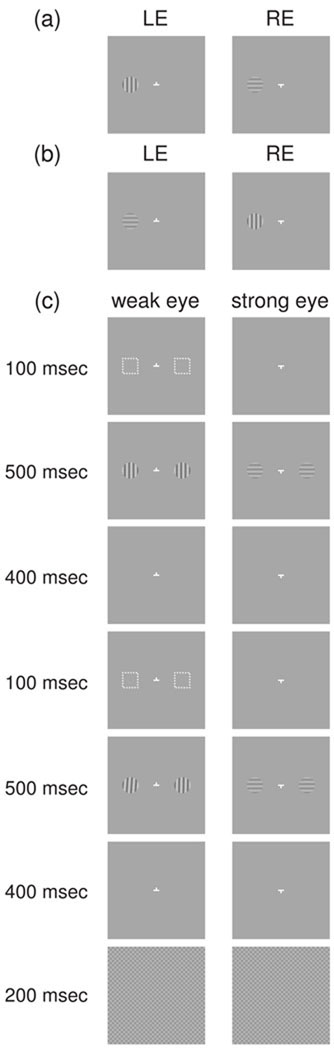

We can psychophysically quantify SED by obtaining each eye’s balance contrast using the procedure shown in figure 1a (Xu et al., 2010a). The two eyes view a briefly presented pair of dichoptic vertical and horizontal gratings. The observer reports which grating is perceived (dominant). To find the point of neutrality, the contrast of the horizontal grating, say, in the right eye (RE) is fixed while the contrast of the vertical grating in the left eye (LE) is adjusted. The LE’s balance contrast is obtained when its image has 50% predominance. Then to obtain the RE’s balance contrast the gratings in the two eyes are switched and the entire procedure is repeated (figure 1b). The difference between the LE and RE’s balance contrast values is the SED, with the eye having the larger balance contrast being the weak eye at the tested retinal location.

Figure 1.

Stimuli for measuring the balance contrast and the push-pull training. (a) and (b) Orthogonal gratings used to measure the balance contrast in the LE and RE, respectively. (c) For the training, two retinal locations, one for the attended and the other for the unattended condition, are simultaneously stimulated. At each location, a cue (white rectangular frame) attracts transient attention to the weak eye, causing its (vertical and near-vertical) gratings to be perceived while the (horizontal) gratings in the strong eye are suppressed. The observer discriminates the orientation of the gratings seen by the weak eye at the attended location.

SED can be reduced using a push-pull perceptual training protocol (figure 1c) (Xu et al., 2010a). In the training, the weak eye was presented with a monocular cue (rectangular frame) to attract transient (bottom-up) attention to it, prior to stimulation by a pair of dichoptic orthogonal gratings (please refer only to the left side of each half-image for now). The transient attention deployed to the weak eye caused its vertical grating image to be seen (push) while the horizontal grating image in the strong eye was suppressed (pull) (Ooi and He, 1999). Shortly after, a second round of cueing and binocular stimulation was repeated. The observer reported if the orientation of the dominant grating disc seen in the first, or second interval, was oriented more to the counterclockwise orientation. Repetitions of such a training sequence led to perceptual learning, which we evaluated by measuring the weak eye’s balance contrast with a grating stimulus that had the same orientation as the training stimuli (figure 1a). We found the balance contrast shifted toward the balance point after the training, indicating a learning effect in reducing SED. We also measured the balance contrast with a grating stimulus in the weak eye whose orientation was orthogonal to the training gratings (figure 1b), but found no reliable learning effect. This indicates the perceptual learning that reduces SED is specific to the orientation and eye-of-origin of the training stimuli.

Perceptual learning probably involves processes distributed over a large span of the cortical network (Crist et al., 1997; Fahle, 1997, 2009; Harauzov et al., 2010; Hua et al., 2010; Karni and Sagi, 1991; Sagi and Tanne, 1994; Sasaki, Nanez, Watanabe, 2010; Schoups et al., 1995; Shiu and Pashler, 1992; Spang et al, 2010; Xiao, et al, 2008; Zhang et al, 2010). But of significance, our psychophysical findings suggest the perceptual learning described above is largely due to early cortical plasticity, particularly, with respect to the eye-of-origin information. This is because the eye-of-origin signal is very likely coded by monocular cortical neurons that are found abundantly in area V1 and less so in the extrastriate cortices (Maunsell and Van Essen, 1983). Here, we capitalize on the modulation of the eye-of-origin signal by the interocular inhibitory mechanism to reveal perceptual learning beyond the focus of top-down visual attention (Ahissar and Hochstein, 1993; Bar and Biederman, 1998; Fahle, 2009; Chun and Jiang, 2003; Frenkel et al, 2006; Godde, et al, 2000; Gutnisk et al, 2009; Paffen et al., 2008; Rosenthal and Humphreys, 2010; Sasaki et al., 2010; Schoups et al., 2001; Seitz et al., 2009; Turk-Browne et al, 2009; Watanabe et al., 2001, 2002; Zhang and Kourtzi, 2010). In our paradigm (figure 1c), two sets of push-pull training stimuli are implemented simultaneously at two different retinal locations with locally large SED. The observer attends to one set of stimulation and performs an orientation discrimination task, while ignoring the other set (Posner, 1980). If perceptual learning can occur beyond the focus of top-down visual attention, a reduction in SED will be found not only at the attended location but also at the unattended location. Confirming this prediction, we found a significant reduction in SED at both the unattended and attended training locations. Furthermore, the perceptual learning leads to improvements in binocular visual functions that were not trained (boundary contour based SED, dynamics of binocular rivalry, and stereopsis).

2. Material and methods

2.1 Apparatus

A Macintosh computer running MATLAB and Psychophysics Toolbox (Brainard, 1997; Pelli, 1997) generated the stimuli on a flat-screen CRT monitor (1280 × 1024 pixels @ 100 Hz). A mirror haploscopic system attached to a chin-and-head rest aided fusion from a viewing distance of 85 cm.

2.2 Observers

Six naïve observers (ages 27–35) with clinically normal binocular vision and informed consent were tested. All observers had normal or corrected-to-normal visual acuity (at least 20/20), clinically acceptable fixation disparity (≤8.6 arc min), central stereopsis (≤20 arc sec), and passed the Keystone vision-screening test.

2.3 General stimuli and procedures for conducting the perceptual learning study

We first measured local SED with dichoptic vertical and horizontal grating discs (1.25o) at eight concentric retinal locations 2° from the fovea (0°, 45°, 90°, 135°, 180°, 225°, 270°, and 315°). Two locations with the largest SED were chosen for the training, one for the attended and the other for the unattended condition (the two locations had 4° spatial separation for four observers and 2.8° separation for two observers). During the 10-day Push-Pull training phase, two pairs of orthogonal grating discs (vertical/horizontal) simultaneously stimulated these two retinal locations (figure 1c). While both retinal locations received the same sequence of stimulation (cue, stimulus-1, cue, stimulus-2, mask), the observers were instructed to only attend to one location. They discriminated the grating orientation of the stimuli at the attended location (vertical vs. near-vertical), and ignored the stimulation at the unattended location. SED at the training locations were measured before each day’s training session to monitor the learning progress. To further assess the learning effect, we made the following measurements at the two training locations in the pre- and post-training phases: boundary contour (BC)-based SED, dynamics of interocular dominance and suppression, stereo threshold and monocular contrast thresholds. The specific stimulation procedures for the training and various measurements are detailed below in sections 2.4–2.5.

2.4 Push-pull training protocol at the attended and unattended retinal locations

The two retinal locations chosen for training were randomly assigned to the attended and unattended conditions, which were implemented simultaneously (figure 1c). A trial began with fixation at the nonius target. Then, at each retinal location, a transient attention cue (1.25°x1.25° frame with dash outline, width=0.1°, 1.56 log unit, 70 cd/m2) was presented monocularly to the weak eye for 100 msec (Ooi and He, 1999). After a 100 msec cue-lead-time, a pair of dichoptic horizontal and vertical gratings (500 msec, 1.25°, 3cpd, 35 cd/m2) was presented. The same 100 msec cue was presented again 400 msec later, followed by a 100 msec cue-lead-time, and the presentation of a second pair of dichoptic gratings (500 msec). The grating orientation shown to the weak eye in this second presentation had a slightly different orientation from the grating in the first presentation. Four hundred msec after the dichoptic grating presentation a binocular checkerboard sinusoidal grating mask (200 msec, 7.5°x7.5°, 3 cpd, 35 cd/m2, 1.5 log unit) terminated the trial. The contrast values of the dichoptic gratings were those that led to the points of neutrality in the RE and LE with the interocular imbalance test. During the trial, the observer was instructed to attend only to one retinal location (attended condition) and ignore the stimulation at the other location (unattended condition).

Before commencing the proper training phase, we determined for each observer that the cue successfully suppressed the grating viewed by the strong eye. For the stimulation at the attended location, the observer reported by key press whether the first or second interval’s grating had a slight counterclockwise orientation, and an audio feedback was given. Fifty such trials were run for each experimental block to obtain the orientation discrimination threshold using the QUEST procedure. Twelve blocks were performed during each training day.

2.5 Specific stimuli and procedures for measuring the various visual functions

2.5.1 Interocular imbalance test to measure SED at 8 different retinal locations

The stimulus comprised a pair of dichoptic vertical and horizontal sinusoidal grating discs (3 cpd, 1.25°, 35 cd/m2) (figure 1a and 1b). The contrast of the horizontal grating was fixed (1.5 log unit) while the contrast of the vertical grating was varied (0–1.99 log unit). A trial began with central fixation on the nonius target (0.45°x0.45°, line width=0.1°, 70 cd/m2), followed by the presentation of the dichoptic orthogonal grating discs (500 msec), and terminated with a 200 msec mask (7.5°x7.5° checkerboard sinusoidal grating, 3 cpd, 35 cd/m2, 1.5 log unit). The observer responded to his/her percept, vertical or horizontal, by key presses. If a mixture of vertical and horizontal orientation was seen, the observer would respond to the predominant orientation seen. The vertical grating contrast was adjusted after each trial using the QUEST procedure (50 trials/block) until the observer obtained equal chance of seeing the vertical and horizontal gratings, i.e., the point of neutrality. Each block was repeated twice. When the vertical grating was presented to the LE we refer to its contrast at neutrality as the LE’s balance contrast. The grating discs were then switched between the eyes to obtain the RE’s balance contrast. The difference between the LE and RE balance contrast is the SED.

In the pre-training phase, SED was measured at eight concentric retinal locations (0°, 45°, 90°, 135°, 180°, 225°, 270°, and 315°) 2° from the fovea. Thus, a total of 16 stimulus combinations (8 locations x 2 eyes), in a randomized testing order, were run. From the eight retinal locations tested, two locations with the largest SED (~ 0.3–0.4 log unit) were chosen for the training. During the training-phase, the SED at the two training-locations were measured with horizontal and vertical gratings before each day’s training session.

2.5.2 Boundary contour (BC)-based SED

We adapted a stimulus from Xu et al. (2010b) to reveal the contribution of the boundary contour to SED. The stimulus comprised a pair of dichoptic vertical (1.8 log unit) and horizontal (1.2 log unit) sinusoidal grating discs (3 cpd, 1.25°, 35 cd/m2), each surrounded by vertical grating (3 cpd, 7.5°x7.5°, 1.8 log unit, 35 cd/m2) (figure 3a). The disc with the vertical grating in one half-image had a variable phase-shift (0–180 degrees) relative to the larger vertical grating surround. A trial began with central fixation on the nonius target (0.45°x0.45°, line width=0.1°, 70 cd/m2) and the presentation of the dichoptic stimulus (500 msec), followed by a 200 msec mask (7.5°x7.5° checkerboard sinusoidal grating, 3 cpd, 35 cd/m2, 1.8 log unit). The observer responded to his/her percept, vertical or horizontal, by key presses. If a mixture of vertical and horizontal orientation was seen, the observer would respond to the predominant orientation seen. The relative phase-shift of the vertical grating disc was adjusted after each trial (step size = 14 degree phase-shift) using the staircase procedure until the observer obtained an equal chance of seeing the vertical and horizontal gratings, i.e., the point of neutrality. Each block of trials (~50–60 trials) comprised 30 reversals, with the last 26 reversals taken as the average threshold. When the vertical grating disc was presented to the LE we refer to its phase-shift at the point of neutrality as the LE’s balance phase-shift. The grating half-images were then switched between the eyes to obtain the RE’s balance phase-shift. The difference in the balance phase-shift between the LE and RE defines the BC-based SED. We tested 4 stimulus combinations [2 locations (attended + unattended) x 2 eyes]. Each combination was repeated twice. The order of testing was randomized.

Figure 3.

Boundary contour-based SED. (a) Stimulus with vertical grating surrounding the vertical and horizontal grating discs. The spatial phase of the vertical grating disc relative to the vertical surround is shifted to obtain the point of neutrality. (b) Similar to (a) except that the gratings are oriented 45° and 135° and the point of neutrality is obtained from the relative phase shift of the 135° grating disc. (c) The BC-based SED is significantly reduced after the training at the attended location but not at the unattended location, with both stimuli (a) and (b).

Separately, the BC-based SED was tested using 45° (1.2 log unit) and 135° (1.8 log unit) grating discs (1.25°, 3 cpd, 35 cd/m2, 500 msec), each surrounded by 135° grating (3 cpd, 7.5°x7.5°, 1.8 log unit, 35 cd/m2) (figure 3b). The staircase method was used, and the phase-shift of the 135° grating disc relative to the 135° surround grating was adjusted after each trial (step size=14 degree phase-shift) until the point of neutrality was obtained for each eye.

2.5.3 Dynamics of interocular dominance and suppression

The stimulus comprised a pair of dichoptic vertical and horizontal grating discs (1.25°, 3 cpd, 35 cd/m2, 1.5 log unit) surrounded by a 7.5°x7.5° gray square (35 cd/m2) (similar to figure 1a and 1b). A trial began with central fixation on the nonius target (0.45°x0.45°, line width=0.1°, 70 cd/m2) and the presentation of the dichoptic orthogonal gratings (30 sec), followed by a 1 sec mask (7.5°x7.5° checkerboard sinusoidal grating, 3 cpd, 35 cd/m2, 1.5 log unit). The observer’s task was to report (track) his/her instantaneous percept of the binocular competitive stimulus over the 30 sec stimulus presentation duration. Depending on the percept, vertical, horizontal, or a mixture of both, he/she would depress the appropriate key until the next percept took over.

Two grating orientation conditions were conducted: “same grating” vs. “orthogonal grating”. The same grating condition had the stimulus grating orientation presented to each eye been the same as the trained grating orientation. The orthogonal grating condition had the grating orientation switched between the two eyes. Altogether, there were 4 stimulus combinations [2 locations (attended + unattended) x 2 conditions (same + orthogonal)]. Each combination was repeated 10 times in a randomized order.

2.5.4 Stereo threshold

A 7.5°x7.5° random-dot stereogram (dot size=0.0132°, 35 cd/m2) with a variable crossed-disparity disc target (1.25°) was used (figure 5a). The contrast of the stereogram was individually selected for each observer, to make the stereo task moderately difficult and to avoid a possible ceiling-effect due to pixel-size constraint. With this criterion, the contrast levels were set at 1.1 log unit for one observer, 1.2 log unit for 3 observers, and 1.3 and 1.5 log units, respectively, for the remaining two observers.

Figure 5.

Transfer of perceptual learning to stereopsis. (a) The random-dot stereogram used for measuring binocular disparity threshold for seeing a disc target in depth. (b) Binocular disparity thresholds are significantly reduced at both the attended and unattended locations after the training.

We used the standard 2AFC method in combination with the staircase procedure to measure stereo disparity threshold. The temporal sequence of stimulus presentation was fixation, interval-1 (200 msec), blank (400 msec), interval-2 (200 msec), blank (400 msec), and random-dot mask (200 msec, 7.5°x7.5°, 35cd/m2). The observer indicated if the crossed-disparity disc was perceived in interval-1 or −2, and an audio feedback was given. Each block comprised 10 reversals (step size = 0.8 arc min, total ~50–60 trials), and the average of the last 8 reversals were taken as the threshold. Each block was repeated 4 times, and measured over two days. The order of testing was “ABBA” for day-1 and “BAAB” for day-2 (“A” = attended condition and “B” = unattended condition).

2.5.5 Monocular contrast threshold

The monocular sinusoidal grating (1.25°, 3 cpd, 35 cd/m2, 500 msec) was either horizontal or vertical for the contrast sensitivity test. The fellow eye viewed a homogeneous field. The test was conducted using a 2AFC method in combination with the QUEST procedure. The 2AFC stimulus presentation sequence was: fixation, interval-1 (500 msec), blank (400 msec), interval-2 (500 msec), blank (400 msec), and mask (7.5°x7.5° checkerboard sinusoidal grating, 3 cpd, 35 cd/m2, 1.5 log unit, 200 msec). The grating was presented at only one interval while the other interval was blank. The observer responded to seeing the grating either in interval-1 or −2 by key press, and an audio feedback was given. The grating contrast was adjusted after each trial (by QUEST) to obtain the threshold. We tested 8 stimulus combinations [2 locations (attended+unattended) x 2 conditions (same + orthogonal) x 2 eyes] in a randomized order. Each stimulus combination was repeated over 2 blocks of trials (50 trials/block).

3. Results

During the training phase, we monitored the observer’s learning progress by measuring his/her balance contrast before each daily training session. In addition, we measured the effect of training on four other visual functions: boundary contour (BC)-based SED, dynamics of interocular dominance and suppression, stereo acuity and monocular contrast thresholds.

3.1 Reduction in SED at both the attended and unattended locations with the trained stimulus feature

The balance contrast was tested with dichoptic gratings whose orientation in each eye was either the same as, or orthogonal to, the orientation of the grating used during the training. To be succinct, we call the former stimulation the “same grating” and the latter the “orthogonal grating”. Figures 2a and 2b plot the interocular balance contrast, which is defined as the difference between the measured balance contrast and 1.5 log unit (contrast of the fixed grating). With the same grating, the mean interocular balance contrast at the attended location (open squares, figure 2a) declines toward the balance point (horizontal dashed line) as the training progresses [slope=−0.0232, R2=0.8683, p<0.001]. But with the orthogonal grating at the attended location, the mean interocular balance contrast (filled squares, figure 1b) only tends slightly toward the balance point [slope=0.0068, R2=0.7749, p<0.001] with a much flatter slope [the interaction effect of 2-orientation vs. 11-training session: F(10, 50)=9.742, p<0.001, 2-way ANOVA with repeated measures]. This finding reconfirms our earlier study (Xu et al., 2010a) that the learning effect is orientation and eye specific, i.e., taps on early cortical plasticity.

Figure 2.

Results of the push-pull training at the attended and unattended locations. (a) The average interocular balance contrast at the attended location obtained, respectively, with grating whose orientation was the same as, or orthogonal to, the grating used in the training. The same interocular balance contrast is the measured contrast in the weak eye minus 1.5 log unit (fixed contrast of grating in the strong eye); whereas the orthogonal interocular balance contrast is the measured contrast in the strong eye minus 1.5 log unit (fixed contrast of grating in the weak eye). The interocular balance contrast reduces significantly with in training, particularly when tested with the same orientation grating. (b) The average interocular balance contrast at the unattended location exhibits a similar trend as that at the attended location. (c) SED, defined as the difference between the same and orthogonal interocular balance contrast reduces significant at both the attended and unattended locations as the training progresses.

Importantly, we found a similar learning effect at the unattended location. The mean interocular balance contrast with the same grating reduces toward the balance point with training (open diamonds, figure 2b) (slope=−0.0146, R2=0.8544, p<0.001). But the mean interocular balance contrast with the orthogonal grating only shows a weak tendency toward the balance point (slope=0.0016, R2=0.133, p=0.270) [interaction effect of 2-orientation vs. 11-training session: F(10, 50)=3.553, p=0.001, 2-way ANOVA with repeated measures].

Figure 2c plots the SED, i.e., the difference between the same grating and orthogonal grating interocular balance contrast values obtained above. Clearly, SED reduces with training at both the attended (slope=−0.0300, R2=0.8968, p<0.001) and unattended locations (slope=−0.0162, R2=0.8136, p<0.001). The slope of the attended condition is significantly steeper than the slope of the unattended condition [F(10, 50)=3.961, p=0.001, 2-way ANOVA with repeated measures]. Altogether, these results reveal SED is significantly reduced at the unattended training location beyond the focus of top-down attention. However, top-down focal attention acts to facilitate perceptual learning as evidenced by the finding at the attended condition (Ahissar and Hochstein, 1993, 1997; Crist et al., 1997).

3.2 Reduction in boundary contour (BC)-based SED only at the attended location

The grating disc stimuli in figure 1a and 1b have similar boundary contour (BC) strength (saliency of the circular disc outline enclosing the grating texture) in each half-image. Thus, the SED obtained from changing the relative grating contrast between the RE and LE mainly reflects the feature-based aspect of SED. We now measured if the SED reduction is associated with a change in the processing of the BC information, which can also affect SED (Ooi and He, 2006; Su et al., 2009, 2010; van Bogaert et al., 2008; Xu et al., 2010b). We used a BC-based SED test (figure 3a), where the BC strength of the vertical grating disc is varied by changing the relative phase-shift between the vertical grating disc and the surrounding vertical grating. Meanwhile, the relative contrast of the dichoptic gratings remains constant. Doing so allows us to obtain the balance phase-shift, i.e., the point of neutrality between the two eyes. We measured the balance phase-shifts before and after the 10-day training period. If the weak eye strengthens after the training and leads to a reduction in BC-based SED, the phase-shift required to reach the point of neutrality will be smaller after, than before, the training.

Figure 3c plots the reduction in BC-based SED, defined as the difference in the amount of phase-shift to reach the point of neutrality before and after training. Thus, a larger angular reduction in phase-shift indicates a larger reduction in BC-based SED. The leftmost bar shows the BC-based SED is significantly reduced at the attended location after the training [t(5)=2.571, p=0.050]. But it decreases little at the unattended retinal location (second bar) [t(5)=0.722, p=0.503]. Comparison between the two locations reveals the reduction in the mean BC-based SED at the attended location is significantly larger [t(5)=3.332, p=0.021]. This result suggests top-down focal attention plays a larger role in perceptual learning of the BC-based mechanism in SED.

We also tested a control condition wherein the dichoptic test stimuli comprised 45° and 135° oriented gratings (figure 3b). Should the learning effect found in figure 3a be contributed by an enhanced BC strength in the weak eye (besides enhanced orientation feature), we would expect to find a similar learning effect with test stimuli whose grating orientations are different from the trained orientations. Confirming this, the result in figure 3c (two right bars) shows a significant reduction in the BC-based SED at the attended location [t(5)=2.601, p=0.048] and an insignificant reduction at the unattended location [t(5)=1.398, p=0.221]. Comparison between the two locations, however, does not reveal a significant difference [t(5)=0.289, p=0.784]. This finding of a learning effect only at the attended location may be attributed to the fact that the BC-based SED is partially mediated by the border ownership selective neurons in the extrastriate cortices (V2 and beyond), which receive robust top-down attention modulation (Qiu et al., 2007; Zhou et al., 2000).

3.3 Learning effect on the dynamics of interocular dominance and suppression: advantage at the attended location with the trained stimulus feature

So far, the measured SEDs are based on a detection task with brief stimulus duration (500 msec) (Xu et al., 2010a). Thus, those measurements mainly reflect the effect of training on the early phase of interocular inhibition. To reveal how the training influences the maintenance of perceptual dominance and its switching frequency, our observers tracked their perceptual dominance while viewing the binocular competitive stimulus (figure 1a and 1b) over an extended duration (30 sec). The grating orientation stimulating the weak (trained) eye was either the same as, or orthogonal to, that during the training. From the data, we calculated the predominance, dominance duration and frequency of dominance. The graphs in the left and right panels of figure 4, respectively, for the attended and unattended conditions, present the mean ratios of the performance of the weak eye to that of the strong eye. A ratio of unity indicates the two eyes performed equally, while a ratio of greater than unity indicates the weak eye performed better for the given stimulus. Figure 4a shows for each condition, the predominance ratio with the same grating stimulus is increased after the training, but do not change much with the orthogonal grating stimulus [F(1,5)=10.991, p=0.021, 3-way ANOVA with repeated measures]. This reconfirms that the learning is specific to the stimulus feature and eye-of-origin. Comparison between the performance with the same grating stimulus reveals a larger predominance ratio in the attended than unattended condition [Main effect of training: F(1,5)=7.295, p=0.043; interaction effect: F(1,5)=6.814, p=0.048, 2-way ANOVA with repeated measures]. Further analysis reveals a significant increase in predominance ratio at the attended location [t(5)=2.786, p=0.039] and a moderate increase at the unattended location [t(5)=2.444, p=0.058]. But for the orthogonal grating stimulus, 2-way ANOVA fails to reveal a reliable impact of the training on the predominance ratio (p>0.3).

Figure 4.

Dynamics of interocular dominance and suppression before (pre) and after (post) the training, measured with gratings whose orientations were either the same as, or orthogonal to, the training gratings. The data are plotted as a ratio of the performance of the weak eye to the strong eye. Thus, a ratio of greater than unity indicates a superior performance in the weak eye for that stimulus. (a) The predominance ratios increase significantly with the same grating after the training at both the attended and unattended locations, indicating an improvement of the weak eye. (b) The trend of the dominance duration ratios is similar to (a). (c) The dominance frequency ratios do not change significantly with training.

The mean dominance duration ratios in figure 4b exhibit a similar trend as the predominance ratios in figure 4a. The dominance duration ratio (weak eye/strong eye) increases after the training with the same grating stimulus, with the larger increase at the attended location [Main effect of training: F(1,5)=7.027, p=0.045; interaction effect between training location and session: F(1,5)=5.307, p=0.069, 2-way ANOVA with repeated measures]. Further analysis reveals a significant increase in the duration ratio at the attended location [t(5)=2.741, p=0.041], and a moderate increase in the ratio at the unattended location [t(5)=2.345, p=0.066] with training. The duration ratios do not change reliably with training with the orthogonal grating stimulus. (Notably, the tracking predominance and duration findings here mirror those found with the interocular imbalance test for SED that uses a detection task. That is, the same eye has the advantage in both the tracking and detection tasks.)

The average dominance frequency ratios in figure 4c do not show any learning effect. A 3-way ANOVA with repeated measures analysis reveals no reliable change in the dominance frequency ratio after the training (p>0.25).

3.4 Perceptual training improves stereo acuity at both the attended and unattended locations

We measured binocular disparity thresholds in the pre- and post-training phases, using a random dot stereogram (figure 5a; an untrained stimulus) at the attended and unattended locations. Similar reductions in stereo thresholds are found at both locations with training [Main effect of the training: F(1,5)=23.656, p=0.005; interaction effect: F(1,5)=0.010, p=0.926, 2-way ANOVA with repeated measures] (figure 5b).

3.5 Monocular contrast threshold: reduction unlikely associated with changes in SED

We measured monocular contrast thresholds in the pre- and post-training phases with horizontal and vertical gratings. Small, but significant reductions in monocular contrast detection thresholds are found after the training at both locations (eye and stimulus) (figure 6) [Main effect of the training: F(1,23)=12.005, p=0.002; interaction effect: F(1,23)=1.609, p=0.217, 2-way ANOVA with repeated measures]. This generalized learning effect is unlikely to be associated with the reduction in SED. For example, had the reduction in monocular contrast thresholds been associated with SED reduction, the contrast threshold reduction in the weak eye would be larger than the contrast threshold reduction in the strong eye.

Figure 6.

Monocular contrast thresholds are significantly reduced after the training at the attended and unattended locations in both the weak and strong eyes. However, these generalized and small reductions are unlikely to be associated with the reduction in SED.

4. Discussion

We found that implementing the push-pull training at both the attended and unattended locations lead to a significant reduction in SED and modifications of other binocular functions. The finding at the unattended location thus reveals a stimulus-driven mechanism for perceptual learning beyond the focus of top-down attention. Focused attention, however, facilitates perceptual learning.

Monocular cueing during the push-pull training (figure 1c) attracts transient, bottom-up attention to the weak eye to cause perceptual dominance of the weak eye at the expense of the strong eye (suppressed) (Xu et al., 2010a; Ooi and He, 1999). The suppression of the strong eye’s signals by the weak eye during the training very likely potentiates the synaptic efficiency of the weak eye’s inhibitory connection that it imposes on the strong eye (channel). At the same time, the failure of the strong eye to suppress the weak eye could depress the synaptic efficiency of the strong eye’s inhibitory connection that it imposes on the weak eye (channel) (Dan and Poo, 2004; Hebb, 1949; Stent, 1973). It is important to emphasize that this plasticity is selectively driven by the binocular competitive stimuli employed in the push-pull training protocol. This is because we previously showed little learning occurred with a push-only training protocol where only the weak eye was stimulated (Xu et al., 2010a).

Overall, our study suggests the plasticity of the interocular inhibitory network and its modification of the eye-of-origin signals is largely stimulus-driven. It is well documented that there is little top-down attention influence on the eye-of-origin information. For instance, it is not possible for us to will ourselves to focus attention on one eye. This is presumably because we have no conscious access to the eye-of-origin information that is explicitly coded by the monocular neurons in the primary visual cortex. We cannot direct attention to say, the RE in the absence of physical stimulation, so that after the onset of a pair of dichoptic orthogonal gratings the image viewed by the “attended” RE prevails. The stimulus-driven learning mechanism found here in the adult binocular visual system might also play a role in shaping the ocular dominance column formation in V1 during early binocular development (Held, 1991; Held and Hein, 1963; Hensch et al., 1998; Huang et al, 1999; Huang et al 2010; LeVay et al., 1980). It would be interesting for future studies to compare the differential development of the ocular dominance columns using the classic monocular deprivation paradigm versus the push-pull paradigm that excites an eye while suppressing the other.

Our study shows the stimulus-driven learning mechanism complements the role of top-down attention in perceptual learning (Ahissar and Hochstein, 1993, 1997; Fahle, 2004; Fiser and Aslin, 2001; Held and Hein, 1963; Lu and Dosher, 2009; Sasaki et al., 2010; Watanabe et al., 2002; Zhang and Kourtzi, 2010). Studies by others have revealed focal attention is critical for perceptual learning (e.g., Ahissar and Hochstein, 1993; Crist et al., 2001; Li et al., 2004; Mukai et al., 2007; Schoups et al., 2001; Shiu and Pashler, 1992). For example, if an observer attends to an orientation feature that is relevant to the perceptual task and ignores other irrelevant features during the training he/she only improves in sensitivity to detect the attended feature (Shiu and Pashler, 1992). Arguably, top-down visual attention is directly deployed to the cortical circuitries that represent global surface, or figure/object, for signal enhancement and selection (Qiu et al., 2007; Duncan, 1984; He and Nakayama, 1995; Reynolds and Chelazzi, 2004). It thus readily lends itself as a “figure/object-based” focal attention to gate perceptual learning of mid- and high-level visual processes (Ahissar and Hochstein, 1993). In contrast, top-down attention only exerts an indirect, and relatively modest influence on the early-level visual processes (e.g., V1), presumably through a feedback network from the extrastriate cortices (Kastner and Ungerleider, 2000; Yoshor et al., 2007). Consistent with this analysis, the facilitated learning effect found at the attended location demonstrates the complementary roles of both types of learning mechanisms (Ahissar and Hochstein, 1993; Sasaki et al., 2010).

Apart from the stimulus-driven learning mechanism, a stimulus-reward pairing learning mechanism (Dayan and Balleine, 2002; Sasaki et al., 2010; Seitz and Dinse, 2007; Seitz et al., 2009) could arguably contribute to the perceptual learning effect at the unattended location. Recent psychophysical studies discovered observers improve their performance in detecting features (e.g., global motion direction) that are irrelevant to the task used in the training (e.g., Seitz et al., 2009; Tsushima et al., 2008; Watanabe et al., 2001, 2002). These findings of task irrelevant perceptual learning (TIPL) provide the first and strongest evidence that top-down attention does not gate all types of perceptual learning (also see Carmel, Khesin, Carrasco, 2010; Gutnisky et al., 2009; Paffen et al., 2008; Polley et al., 2006; Rosenthal and Humphreys, 2010). It is proposed that during a training trial, when a task irrelevant stimulation is paired with reward signals released from the central nervous system, the network that processes the task irrelevant stimulus is modified, thereby driving perceptual learning (Seitz et al., 2009; Seitz and Dinse, 2007). The stimulus-reward pairing learning mechanism could plausibly contribute to the perceptual learning of SED at the unattended location. This is because successful performance in orientation discrimination of the dominant grating discs at the attended location might trigger the reward system, which consequently facilitated the stimulus-driven learning at the unattended location, since the training stimuli were presented simultaneously at the unattended and attended locations. Further studies that use a learning protocol that is capable of dissociating between these two learning mechanisms are needed to test this possibility.

External stimulations are critical for neural wiring during early development before the juvenile animals are fully conscious of their environment (Hubel and Wiesel, 1970), and before they are able to depend on the top-down attention system. At this stage, the juvenile brain depends predominantly on the stimulus-driven learning mechanism for cortical plasticity. It has been assumed that with maturation, the stimulus-driven learning mechanism, which operates automatically (unconsciously), phases off and yields to the attention-gated learning mechanism to select what information is learned. This view is consistent with the empirical findings that top-down attention is required for substantial perceptual learning to occur in adults (e.g., Ahissar and Hochstein, 1993; Shiu and Pashler, 1992). However, a sole dependence on the attention-gated learning mechanism may not be sufficient for the adult sensory system to survive in the dynamic, natural environment where highly visible background information that usually escapes the purview of focal attention can also have a biological significance. Our findings that visual performance at a location beyond the focus of top-down attention improves after that location was repeatedly exposed to highly visible stimuli indicates that the matured brain retains the ability to learn automatically. These considerations strongly suggests that the stimulus-driven learning mechanism plays a significant role in the early visual process where top-down attention modulation is relatively weak and its information content (e.g., eye-of-origin signal) cannot be directly accessed by visual awareness. In adults, both types of learning mechanisms co-exist. Presumably, top-down attention suppresses stimulus-driven learning of highly visible task irrelevant information at the higher cortical levels but does not prevent stimulus-driven learning at the lower cortical level.

5. Conclusions

A number of studies have shown that adult perceptual learning is largely controlled by the top-down attention system. The current study demonstrates that the matured brain also has an alternative, purely stimulus-driven learning mechanism that enables it to automatically learn highly visible information beyond the zone focal attention. The stimulus-driven learning mechanism is prominent at the early visual level where top-down attention modulation is relatively weak.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (EY015804) to TLO and ZJH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

SED: sensory eye dominance

References

- Ahissar M, Hochstein S. Attentional control of early perceptual learning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1993;90:5718–5722. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.12.5718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahissar M, Hochstein S. Task difficulty and the specificity of perceptual learning. Nature. 1997;387:401–406. doi: 10.1038/387401a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar M, Biederman I. Subliminal visual priming. Psychol. Sci. 1998;9:464–469. [Google Scholar]

- Brainard DH. The Psychophysics Toolbox. Spat. Vis. 1997;10:433–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmel D, Khesin A, Carrasco M. Attentional facilitation of perceptual learning without awareness. J Vis. 2010;10(7):357. doi:10.1167/10.7.357. [Google Scholar]

- Chun MM, Jiang Y. Implicit, long-term spatial contextual memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2003;29:224–234. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.29.2.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crist RE, Kapadia MK, Westheimer G, Gilbert CD. Perceptual learning of spatial localization: specificity for orientation, position, and context. J. Neurophysiol. 1997;78:2889–2894. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.6.2889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crist RE, Li W, Gilbert CD. Learning to see: experience and attention in primary visual cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 2001;4:519–525. doi: 10.1038/87470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dan Y, Poo MM. Spike timing-dependent plasticity of neural circuits. Neuron. 2004;44:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayan P, Balleine BW. Reward, motivation, and reinforcement learning. Neuron. 2002;36:285–298. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00963-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan J. Selective attention and the organization of visual information. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 1984;113:501–517. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.113.4.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahle M. Specificity of learning curvature, orientation, and vernier discriminations. Vision Res. 1997;37:1885–1895. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(96)00308-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahle M. Perceptual learning: a case for early selection. J. Vis. 2004;4:879–890. doi: 10.1167/4.10.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahle M. Perceptual learning and sensomotor flexibility: cortical plasticity under attentional control? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 2009;364:313–319. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiser J, Aslin RN. Unsupervised statistical learning of higher-order spatial structures from visual scenes. Psychol. Sci. 2001;12:499–504. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenkel MY, Sawtell NB, Diogo AC, Yoon B, Neve RL, Bear MF. Instructive effect of visual experience in mouse visual cortex. Neuron. 2006;51:339–349. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godde B, Stauffenberg B, Spengler F, Dinse HR. Tactile coactivation-induced changes in spatial discrimination performance. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:1597–1604. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-04-01597.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutnisky DA, Hansen BJ, Iliescu BF, Dragoi V. Attention alters visual plasticity during exposure-based learning. Curr. Biol. 2009;19:555–560. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harauzov A, Spolidoro M, DiCristo G, De Pasquale R, Cancedda L, Pizzorusso T, Viegi A, Berardi N, Maffei L. Reducing intracortical inhibition in the adult visual cortex promotes ocular dominance plasticity. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:361–371. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2233-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He ZJ, Nakayama K. Visual attention to surfaces in three-dimensional space. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1995;92:11155–11159. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.11155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua T, Bao P, Huang C-B, Wang Z, Xu J, Zhou Y, Lu Z-L. Perceptual Learning Improves Contrast Sensitivity of V1 Neurons in Cats. Curr. Biol. 2010;20:887–894. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.03.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebb DO. The organization of behavior. New York: Wiley; 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Held R. Development of binocular vision and stereopsis. In: Regan D, editor. Binocular Vision. London: Macmillan; 1991. pp. 171–178. [Google Scholar]

- Held R, Hein A. Movement-produced stimulation in the development of visually guided behavior. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 1963;56:872–876. doi: 10.1037/h0040546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensch TK, Fagiolini M, Mataga N, Stryker MP, Baekkeskov S, Kash SF. Local GABA circuit control of experience-dependent plasticity in developing visual cortex. Science. 1998;282:1504–1508. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5393.1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubel DH, Wiesel TN. The period of susceptibility to the physiological effects of unilateral eye closure in kittens. J. Physiol. 1970;206:419–436. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1970.sp009022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Z Kirkwood A, Morales B, Pizzorusso T, Porciatti V, Bear MF, Maffei L, Tonegawa S. BDNF is a key regulator of the maturation of inhibition and critical period of mouse visual cortex. Cell. 1999;98:739–755. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81509-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Gu Y, Quinlan EM, Kirkwood A. A refractory period for rejuvenating GABAergic synaptic transmission and ocular dominance plasticity with dark exposure. J Neurosci. 2010;30(49):16636–16642. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4384-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubel DH, Wiesel TN. The period of susceptibility to the physiological effects of unilateral eye closure in kittens. J. Physiol. 1970;206:419–436. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1970.sp009022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karni A, Sagi D. Where practice makes perfect in texture discrimination: evidence for primary visual cortex plasticity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1991;88:4966–4970. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.11.4966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastner S, Ungerleider LG. Mechanisms of visual attention in the human cortex. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2000;23:315–341. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeVay S, Wiesel TN, Hubel DH. The development of ocular dominance columns in normal and visually deprived monkeys. J. Comp. Neurol. 1980;191:1–51. doi: 10.1002/cne.901910102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Piëch V, Gilbert CD. Perceptual learning and top-down influences in primary visual cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 2004;7:651–657. doi: 10.1038/nn1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z-L, Dosher B. Mechanisms of Perceptual Learning. Learning and Perception. 2009;1:19–36. doi: 10.1556/LP.1.2009.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maunsell JH, Van Essen DC. Functional properties of neurons in middle temporal visual area of the macaque monkey. II. Binocular interactions and sensitivity to binocular disparity. J. Neurophysiol. 1983;49:1148–1167. doi: 10.1152/jn.1983.49.5.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukai I, Kim D, Fukunaga M, Japee S, Marrett S, Ungerleider LG. Activations in visual and attention-related areas predict and correlate with the degree of perceptual learning. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:11401–11411. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3002-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooi TL, He ZJ. Binocular rivalry and visual awareness: the role of attention. Perception. 1999;28:551–574. doi: 10.1068/p2923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooi TL, He ZJ. Sensory eye dominance. Optometry. 2001;72:168–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooi TL, He ZJ. Binocular rivalry and surface-boundary processing. Perception. 2006;35:581–603. doi: 10.1068/p5489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paffen CL, Verstraten FA, Vidnyánszky Z. Attention-based perceptual learning increases binocular rivalry suppression of irrelevant visual features. J. Vis. 2008;8 doi: 10.1167/8.4.25. 25.1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelli DG. The VideoToolbox software for visual psychophysics: transforming numbers into movies. Spat. Vis. 1997;10:437–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polley DB, Steinberg EE, Merzenich MM. Perceptual learning directs auditory cortical map reorganization through top-down influences. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:4970–4982. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3771-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner MI. Orienting of attention. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 1980;32:3–25. doi: 10.1080/00335558008248231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu FT, Sugihara T, von der Heydt R. Figure-ground mechanisms provide structure for selective attention. Nat. Neurosci. 2007;10:1492–1499. doi: 10.1038/nn1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds JH, Chelazzi L. Attentional modulation of visual processing. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2004;27:611–647. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.26.041002.131039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal O, Humphreys GW. Perceptual organization without perception. The subliminal learning of global contour. Psychol Sci. 2010;21:1751–1758. doi: 10.1177/0956797610389188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagi D, Tanne D. Perceptual learning: learning to see. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 1994;4:195–199. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(94)90072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki Y, Nanez JE, Watanabe T. Advances in visual perceptual learning and plasticity. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2010;11:53–60. doi: 10.1038/nrn2737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schor CM. Binocular sensory disorders. In: Regan D, editor. Vision and visual dysfunction. Boston: CRC Press; 1991. pp. 179–218. [Google Scholar]

- Schoups AA, Vogels R, Orban GA. Human perceptual learning in identifying the oblique orientation: retinotopy, orientation specificity and monocularity. J. Physiol. 1995;483:797–810. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoups A, Vogels R, Qian N, Orban G. Practising orientation identification improves orientation coding in V1 neurons. Nature. 2001;412:549–553. doi: 10.1038/35087601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seitz AR, Dinse HR. A common framework for perceptual learning. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2007;17:148–153. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seitz AR, Kim D, Watanabe T. Rewards evoke learning of unconsciously processed visual stimuli in adult humans. Neuron. 2009;61:700–707. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiu LP, Pashler H. Improvement in line orientation discrimination is retinally local but dependent on cognitive set. Percept. Psychophys. 1992;52:582–588. doi: 10.3758/bf03206720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spang K, Grimsen C, Herzog MH, Fahle M. Orientation specificity of learning vernier discriminations. Vision Research. 2010;50(4):479–485. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stent GS. A physiological mechanism for Hebb's postulate of learning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1973;70:997–1001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.4.997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Y, He ZJ, Ooi TL. Coexistence of binocular integration and suppression determined by surface border information. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:15990–15995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903697106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su YR, He ZJ, Ooi TL. The magnitude and dynamics of interocular suppression affected by monocular boundary contour and conflicting local features. Vision Res. 2010;50:2037–2047. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turk-Browne NB, Scholl BJ, Chun MM, Johnson MK. Neural evidence of statistical learning: Efficient detection of visual regularities without awareness. J Cogn Neurosci. 2009;21:1934–1945. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsushima Y, Seitz AR, Watanabe T. Task-irrelevant learning occurs only when the irrelevant feature is weak. Curr. Biol. 2008;18:R516–R517. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Bogaert EA, Ooi TL, He ZJ. The monocular-boundary-contour mechanism in binocular surface representation and suppression. Perception. 2008;37:1197–1215. doi: 10.1068/p5986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T, Náñez JE, Sasaki Y. Perceptual learning without perception. Nature. 2001;413:844–848. doi: 10.1038/35101601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T, Náñez JESr, Koyama S, Mukai I, Liederman J, Sasaki Y. Greater plasticity in lower-level than higher-level visual motion processing in a passive perceptual learning task. Nat. Neurosci. 2002;5:1003–1009. doi: 10.1038/nn915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao LQ, Zhang JY, Wang R, Klein SA, Levi DM, Yu C. Complete transfer of perceptual learning across retinal locations enabled by double training. Curr. Biol. 2008;18:1922–1926. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu JP, He ZJ, Ooi TL. Effectively reducing sensory eye dominance with a push-pull perceptual learning protocol. Curr. Biol. 2010a;20:1864–1868. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.09.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu JP, He ZJ, Ooi TL. Surface boundary contour strengthens image dominance in binocular competition. Vision Res. 2010b;50:155–170. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshor D, Ghose GM, Bosking WH, Sun P, Maunsell JH. Spatial attention does not strongly modulate neuronal responses in early human visual cortex. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:13205–13209. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2944-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Kourtzi Z. Learning-dependent plasticity with and without training in the human brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:13503–13508. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002506107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T, Xiao LQ, Klein SA, Levi DM, Yu C. Decoupling location specificity from perceptual learning of orientation discrimination. Vision Res. 2010;50:368–374. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2009.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H, Friedman HS, von der Heydt R. Coding of border ownership in monkey visual cortex. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:6594–6611. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-17-06594.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.