Abstract

Malarial parasites have evolved resistance to all previously used therapies, and recent evidence suggests emerging resistance to the first-line artemisinins. To identify antimalarials with novel mechanisms of action, we have developed a high-throughput screen targeting the apicoplast organelle of Plasmodium falciparum. Antibiotics known to interfere with this organelle, such as azithromycin, exhibit an unusual phenotype whereby the progeny of drug-treated parasites die. Our screen exploits this phenomenon by assaying for “delayed death” compounds that exhibit a higher potency after two cycles of intraerythrocytic development compared to one. We report a primary assay employing parasites with an integrated copy of a firefly luciferase reporter gene and a secondary flow cytometry-based assay using a nucleic acid stain paired with a mitochondrial vital dye. Screening of the U.S. National Institutes of Health Clinical Collection identified known and novel antimalarials including kitasamycin. This inexpensive macrolide, used for agricultural applications, exhibited an in vitro IC50 in the 50 nM range, comparable to the 30 nM activity of our control drug, azithromycin. Imaging and pharmacologic studies confirmed kitasamycin action against the apicoplast, and in vivo activity was observed in a murine malaria model. These assays provide the foundation for high-throughput campaigns to identify novel chemotypes for combination therapies to treat multidrug-resistant malaria.—Ekland, E. H., Schneider, J., Fidock, D. A. Identifying apicoplast-targeting antimalarials using high-throughput compatible approaches.

Keywords: Plasmodium falciparum, delayed death, drug discovery

Despite recent advances in antimalarial control efforts, Plasmodium falciparum parasites continue to inflict a staggering burden, infecting nearly 225 million people and causing >780,000 deaths annually (1). Parasite acquisition of resistance to chloroquine and other 4-aminoquinoline-based antimalarials, as well as to the antifolate combination sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine, has resulted in near-universal reliance on artemisinin-based combination therapies to achieve high rates of clinical cure (2, 3). However, studies have recently provided evidence that strains of P. falciparum in Western Cambodia are being cleared at a slower rate following treatment with the artemisinin derivative artesunate, suggesting that clinical treatment failures might be forthcoming (4, 5). These observations emphasize the need to identify new antimalarial chemotypes for which there are no preexisting mechanisms of resistance.

P. falciparum parasites are single-celled Apicomplexan protozoa with a complex life cycle including both human and mosquito hosts. Malarial parasites complete the sexual phase of their life cycle in Anopheles mosquitoes, which subsequently transmit a small inoculum of malarial sporozoites to humans when they take a blood meal. The sporozoites rapidly migrate from the skin to the liver, where they replicate inside hepatocytes to form thousands of parasites per infected cell (6). After 6–7 d, merozoites egress from the ruptured hepatocytes to initiate a blood stage infection. The asexual erythrocytic cycle lasts 48 h, during which the parasites progress through ring, trophozoite, and schizont stages, culminating in the rupture of infected erythrocytes and the release of new merozoites (6, 7). It is during the blood stage infection that patients begin to experience symptoms, and most antimalarials target this stage of the parasite life cycle. Intraerythrocytic P. falciparum parasites can be propagated in vitro, making them amenable to high-throughput screens (HTS; refs. 8–11).

Malarial parasites, and most other Apicomplexans, posses an unusual organelle termed the apicoplast (12, 13). This organelle is thought to be a vestigial, nonphotosynthetic remnant of a chloroplast, derived from a red alga that resided symbiotically within a protozoan ancestor of the Apicomplexa (14). Chloroplasts themselves evolved through an earlier endosymbiotic relationship between photosynthetic cyanobacteria and eukaryotic host cells (13). The apicoplast possesses a cryptic 35-kb cyanobacterial genome (most of the ∼500 genes required for its function have been transferred to the protozoan host nucleus), is bounded by 4 membrane layers, and houses biosynthetic processes commonly found in chloroplasts. These include the production of heme and iron-sulfur clusters, the type II fatty acid synthesis pathway, and the nonmevalonate pathway for isoprenoid synthesis (13, 15).

The apicoplast is essential for Plasmodium blood-stage survival. A number of antibiotics, including azithromycin, doxycycline, and clindamycin, kill these parasites by interfering specifically with the prokaryote-derived translation machinery encoded by the apicoplast genome (16–19). Classic antimalarials (for example, chloroquine and sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine that interfere with heme detoxification and folate biosynthesis, respectively), typically kill parasites in the first generation. Interestingly, the apicoplast-specific antibiotics exhibit an unusual “delayed death” phenotype in which the progeny of the treated parasites die, rather than the treated parasites themselves (17, 20). The potential for identifying novel apicoplast-specific inhibitors is illustrated by the recent finding that mupirocin demonstrates delayed death activity by inhibiting an isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase that is encoded in the nucleus but required in the apicoplast (21).

All of the drugs currently known to interfere with the apicoplast are antibiotics that serendipitously were discovered to have antimalarial activity. The assay described herein leverages the delayed death phenotype to enrich for potent, Plasmodium-specific compounds that target the apicoplast. Scaling up our screen should identify new classes of antimalarials that are not subject to preexisting mechanisms of resistance in endemic settings. In addition, the identification of novel delayed death inhibitors will be valuable in helping to elucidate the cellular and biochemical basis of the delayed death phenotype.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Parasite strains and propagation

Nonrecombinant P. falciparum lines (3D7, Dd2, and 7G8) and the rodent Plasmodium yoelii nigeriensis N67 strain were obtained from MR4 (http://www.mr4.org). Luciferase-expressing 3D7-HLH and Dd2-HLH parasites were generated using the Bxb1 mycobacterial integrase system as described previously (22, 23). These parasites express firefly luciferase under the regulatory control of hrp3 and hrp2 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions respectively, with this reporter integrated into the nonessential cg6 gene (22). These lines express 2 selectable markers, human dihydrofolate reductase and blasticidin-S deaminase. Long-term cultures were maintained in 1 nM WR99210 (Jacobus Pharmaceuticals, Princeton, NJ, USA) and 0.5 μg/ml blasticidin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) to ensure that the luciferase locus was not lost. Drug selection was removed 1 wk before setting up assays to ensure optimal parasite growth. Azithromycin-resistant Dd2 and 7G8 lines have been previously reported (18).

P. falciparum parasites were cultured at 4% hematocrit in human red blood cells diluted in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 5 mg/ml Albumax (Gibco), 50 μg/ml hypoxanthine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), 2.4 mg/ml Na2CO3 (Gibco), 25 mM HEPES, and 10 ng/ml gentamicin (Gibco). Parasites were incubated at 37°C in plates in a humidified chamber (Billups-Rothenberg, Del Mar, CA, USA), gassed with 5%CO2/5%O2/90%N2.

P. yoelii parasites were expanded in CD1 outbred mice (Charles River, Wilmington, MA, USA). When the parasitemia reached ∼5%, the blood was harvested, diluted in an equal volume of Glycerolyte 57 (Fenwal, Lake Zurich, IL, USA), and cryopreserved in 200-μl aliquots at −140°C. A fresh vial was thawed and inoculated into donor mice at the initiation of each experiment.

Comparison of [3H]hypoxanthine, SYBR, and luciferase assays

Two fast acting drugs, artesunate (Guilin Pharmaceutical Company, Guangxi, China) and chloroquine HCl [Clinical Center–Pharmacy Dept., U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH), Bethesda, MD, USA], and 2 delayed death-inducing drugs, azithromycin (Zithromax; Pfizer, New York, NY, USA) and doxycycline (Sigma-Aldrich), were used for comparative purposes. Drug assays were optimized to work in 30-μl culture volumes in 384-well clear bottom plates (Greiner Bio-one, Monroe, NC, USA). Liquid dispensing was performed using a Precision-2000 microplate pipetting system (BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA). Drugs were diluted in the plate to a 2× concentration in 15 μl of RPMI culture medium, followed by the addition of 15 μl of parasites per well (2% final hematocrit).

[3H]hypoxanthine (Hxt) assays were conducted as described previously (18) with minor modifications. Dd2 or 3D7 parasites were cultured in low-Hxt (2.5 μg/ml) medium for 48 or 96 h, at which point we added 10 μl of [3H]-Hxt diluted in culture medium (0.125 μCi/well). After a further 24 h, plates were frozen overnight; the lysates were harvested onto glass fiber filter mats (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA); and the amount of incorporated radiolabel was measured using a Wallac Microbeta (PerkinElmer) liquid scintillation counter.

SYBR Green-I (SYBR; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) assays were executed in the same manner, except that wells received 10 μl of RPMI without [3H]-Hxt at 48 or 96 h. After 24 h, we added 15 μl of 3× SYBR in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.16% w/v saponin, and 1.6% v/v Triton X-100) to each well before freezing. Samples were thawed for 2 h before measuring fluorescence on a Victor3 microplate reader (PerkinElmer) using a 485-nm excitation filter and a 535-nm emission filter.

Luciferase assays followed the same protocol outlined for the SYBR assays, except that we used 3D7-HLH or Dd2-HLH luciferase-expressing parasites. At the end of the assay, the parasites were frozen at −80°C. After thawing, each well received 15 μl of 3× Luciferin lysis buffer (15 mM DTT, 0.6 mM coenzyme A, 0.45 mM ATP, 0.42 mg/mL luciferin, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Tris Base, 10 mM Tris-HCl, and 0.03% Triton X-100). The samples were read for 3 s each using the luminescence settings on the Victor3 microplate reader.

For these assays, Prism software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA) was used to derive IC50 values by nonlinear curve fitting. Every plate in every assay contained control wells with no drug to establish the maximal signal for each plate. For the purposes of fitting curves to the data on a logarithmic scale, this zero drug concentration was assigned a concentration 2 dilutions below the last actual dilution in the series.

Optimization of luciferase assays for quantitative HTS

During further optimization, we observed that freeze-thawing was not required. Furthermore, initiating assays at 0.1 or 0.05% parasitemia rendered it unnecessary to add extra medium at 48 h or 96 h, respectively (Supplemental Fig. S1; data not shown). Comparisons between 96- and 120-h assays revealed the former to be sufficient to detect delayed death (Supplemental Fig. S1B).

The NIH Clinical Collection compounds were tested in seven 5-fold dilutions, (final concentration range of 50 μM to 3.2 nM). We used a 0.1% starting parasitemia for the 48-h assays and a 0.05% starting parasitemia for the 96-h assays, both at a 2% hematocrit. Chambers were gassed daily, but no other manipulations were performed for the duration of the assay. Plates were stored at −80°C after either 48 or 96 h and then analyzed as described above. Data points were uploaded to the Collaborative Drug Discovery website (http://www.collaborativedrug.com), and IC50 values were calculated by nonlinear curve fitting, using a Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm to fit a Hill equation to the dose-response data.

Flow cytometric evaluation of parasitemias

For the flow cytometry-based validation screen, P. falciparum drug assays were conducted in flat-bottom 96-well plates in a 200 μl culture volume, 1% hematocrit, and 0.2% starting parasitemias. After 48 and 96 h, 20-μl samples were harvested and stained for 30 min at 37°C with 50 μl of 2.5× SYBR plus 150 nM MitoTracker Deep Red (MTDR; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) diluted in culture medium. Samples were washed in saline dextrose (0.9% NaCl, 5% dextrose) and centrifuged for 1 min at 400 g in a swing-bucket rotor. Excess stain was removed, and the samples were resuspended in 100 μl of complete medium. Samples were collected on a 2-laser cytometer (Accuri Cytometers, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) equipped with a 96-well plate sampler, with ≥1000 parasitized erythrocytes collected per control untreated sample.

For P. yoelii assays, we sampled 1 μl of blood from the tail vein of infected mice. Blood was diluted in 30 μl of citrate:phosphate:dextrose (diluted 1:10 in culture medium; Sigma-Aldrich) in 96-well plates. P. yoelii-infected cells were stained as for P. falciparum (see above).

The conditions listed above were optimized to minimize background staining in uninfected mice while achieving saturating staining of the parasites in mice with parasitemias up to 20%. At higher parasitemias, SYBR and MTDR may not achieve saturation, leading to variable staining. Under other experimental conditions (e.g., using purified parasites, larger sample volumes, or sampling from mice with parasitemias >20%), we recommend titrating the amount of stain to ensure saturating conditions.

Microscopy-based assays

Parasites expressing GFP targeted to the apicoplast (3D7 ACP(L)-GFP; ref. 24) were kindly provided by Geoff McFadden (University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia). These parasites were cultured for 96 h in 1 ml of culture medium in 24-well plates (Costar, Corning, NY, USA). Assays were initiated at a 0.3% starting parasitemia and a 2% hematocrit. Cultures contained drugs at twice their IC50 value (final concentrations of 50 nM azithromycin, 20 nM BMS-388891, 1.5 μM clarithromycin, 1 μM doxycycline, or 120 nM kitasamycin). BMS-388891 was kindly provided by Wesley C. Van Voorhis and Michael H. Gelb (University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA). Kitasamycin (Sequoia Research Products, Pangbourne, UK) and clarithromycin (Sigma-Aldrich) were purchased. At 72 h, half of the medium was removed and replaced with fresh medium containing drug. On d 4, 30 μl of culture was harvested from each well and washed in phenol red-free RPMI medium (Gibco). Cells were resuspended in 300 μl of the same medium containing 1 μg/ml Hoechst 33342 (Sigma-Aldrich) and 20 nM MitoTracker Red FM (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA). Cells were allowed to adhere for 15 min at 37°C on poly-d-lysine-coated glass-bottom culture dishes (MatTek, Ashland, MA, USA). The medium was then exchanged with fresh phenol red-free RPMI containing 5 mg/ml Albumax. Microscopy images were collected on an Eclipse Ti inverted microscope (Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY, USA) using the NIS-Elements software (Nikon).

In vivo assays

Six- to 8-wk-old CD1 mice were infected with 107 P. yoelii nigeriensis parasites by intraperitoneal injection. After 2 h, groups of 5 mice were injected intraperitoneally with 25 μl azithromycin or kitasamycin. Mice received 50 mg/kg or 5 mg/kg of each drug. Azithromycin was suspended in 80% saline dextrose, 20% DMSO. Kitasamycin was suspended in 20% saline dextrose, 80% DMSO. Control mice were injected with 20% saline dextrose, 80% DMSO. Mice received repeat doses once daily for the next 3 d. On d 4 postinfection, we assayed 1 μl of blood and determined parasitemias by flow cytometry. Percentage inhibition for each treated mouse was calculated relative to the average parasitemia of the control mice. Rodent experiments were conducted in fully accredited animal facilities and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of Columbia University.

Statistics

For drug assays, the same starting parasite population was used for each of the different experimental conditions, and differences in IC50 values were tested for significance using paired t tests. Values are presented as means ± se.

RESULTS

A luciferase-based primary screen for detecting delayed death antimalarials

Traditionally, parasite drug susceptibility assays have used the incorporation of tritiated-hypoxanthine ([3H]-Hxt) to measure parasite survival (25). However, several nonradioactive methods for measuring parasite growth have recently been used in large-scale screens for antimalarial compounds (8, 9, 26). These assays have estimated erythrocytic parasitemias based on the activity of endogenous enzymes, such as P. falciparum lactate dehydrogenase (PfLDH; ref. 8), or the use of dyes such as SYBR-green I (SYBR) and DAPI that fluoresce when intercalated with nucleic acids (11, 26).

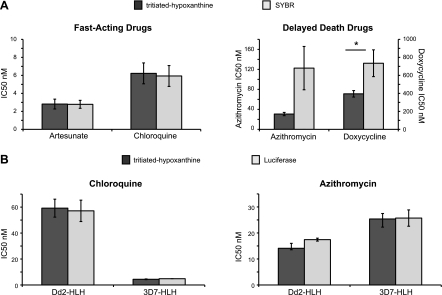

We initially compared SYBR to [3H]-Hxt for quantifying parasite growth. P. falciparum 3D7 parasites were exposed to drug dilution series for 2 generations (96 h), after which we added medium containing [3H]-Hxt (or plain medium for the SYBR assay). One day later (120 h total), the cultures were harvested, and parasite survival was evaluated. The concentration at which parasite growth was inhibited by 50% (IC50) was calculated by nonlinear regression curve fitting. When testing fast-acting drugs, like chloroquine or artesunate, SYBR and [3H]-Hxt generated IC50 values in the same range (artesunate: 2.8±0.4 nM with SYBR vs. 2.8±0.5 nM with [3H]-Hxt; chloroquine: 5.9±1.2 nM with SYBR vs. 6.2±1.2 nM with [3H]-Hxt; calculated from 6 independent experiments; Fig. 1A). However, when assaying delayed death-inducing drugs, such as azithromycin or doxycycline, SYBR generated IC50 values that were skewed considerably higher (azithromycin: 123±43 nM with SYBR vs. 31±3 nM with [3H]-Hxt; doxycycline: 730±150 nM with SYBR vs. 390±36 nM with [3H]-Hxt; 6 independent experiments; Fig. 1A). With these delayed death-inducing drugs, SYBR also provided only a 2- to 3-fold signal to noise ratio with poor quality dose-response curves and a Z′ factor of 0.05 ± 0.36. The poor resolving capacity of the SYBR assay is consistent with the observation that parasites treated with delayed death inhibitors continue to develop during the second generation and can form multinucleated schizonts (16, 17). There is thus a substantial amount of nucleic acid produced before the parasites arrest late in the second cycle of growth. Studies using PfLDH as a marker of cell death also generated higher than expected IC50 values for slow-acting drugs (data not shown), perhaps reflecting a long half-life for PfLDH in the culture supernatants.

Figure 1.

Robust detection of delayed death antimalarial activity using a luciferase reporter assay. P. falciparum asexual blood stage parasites (3D7 strain) were treated with fast-acting drugs (artesunate or chloroquine) or delayed-death drugs (azithromycin or doxycycline) for 96 h, at which point they received medium with or without [3H]-Hxt. After 24 h, drug assays were harvested, and parasite growth was assessed based on either [3H]-Hxt incorporation, nucleic acid content as measured by SYBR-green I (SYBR) fluorescence, or luciferase luminescence. A) SYBR generated comparable IC50 values to [3H]-Hxt incorporation when tested on fast-acting drugs, but produced elevated and more variable IC50 values when assessing delayed death drugs (average of 6 independent experiments, P=0.07 for azithromycin, P=0.03 for doxycycline, paired t test). *P < 0.05. B) Luciferase assays were conducted with either a chloroquine-resistant strain (Dd2-HLH) or a sensitive strain (3D7-HLH). Luciferase activity and [3H]-Hxt incorporation methods generated comparable IC50 values with no statistically significant difference observable for either strain with either drug after 6 independent repeats (paired t test).

As a high-throughput compatible alternative, we measured parasite viability using parasites with an integrated copy of firefly luciferase (23). This method generated IC50 values similar to the [3H]-Hxt assay for both fast- and slow-acting drugs when using either a chloroquine-resistant strain (Dd2-HLH) or a chloroquine-sensitive strain (3D7-HLH): for Dd2-HLH: chloroquine, 57 ± 8.2 nM with luciferase vs. 59 ± 6.9 nM with [3H]-Hxt; azithromycin, 17.4 ± 0.6 nM with luciferase vs. 14.1 ± 1.9 nM with [3H]-Hxt; calculated from 4 independent experiments; and for 3D7-HLH: chloroquine, 4.8 ± 0.1 nM with luciferase vs. 4.4 ± 0.3 nM with [3H]-Hxt; azithromycin, 25.7 ± 3.1 nM with luciferase vs. 25.4 ± 2.1 nM with [3H]-Hxt (4 independent experiments; Fig. 1B).

To model HTS conditions, the assay was optimized to sustain parasite growth in a 30-μl culture volume in 384-well plates, with no medium changes. Using a 2% hematocrit with a 0.05% starting parasitemia for a 120-h assay generated highly reproducible results. At higher parasitemias, the parasites exhausted the medium and frequently crashed, leading to variability (Supplemental Fig. S1A). We also determined that the IC50 values generated by the luciferase assay at 96 h were equivalent to those generated at 120 h, allowing us to reduce the assay length (Supplemental Fig. S1B). In 3 pilot runs, the optimized 96-h luciferase assay generated a signal to noise ratio of 51 ± 17 and a Z′ factor of 0.71 ± 0.07. Our baseline for complete parasite killing was established using parasites that had been treated with 6 μM azithromycin.

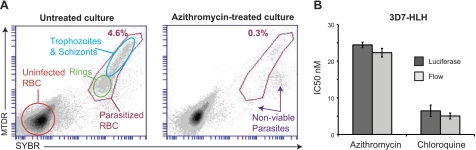

Flow cytometric evaluation of delayed death-inducing compounds

A number of flow cytometry protocols have been described for detecting parasitized erythrocytes based on nucleic acid content (27–29). Many of these protocols require multistep procedures, such as permeabilizing the parasite membrane, and do not readily identify live cells. To develop a simple, medium-throughput, flow cytometry-based assay that would distinguish viable from nonviable cells, we tested several stain combinations including YOYO-1, acridine orange, DRAQ5, and SYTO-61 (data not shown). Results showed that SYBR in conjunction with MTDR provided an excellent combination (Fig. 2A). Both dyes are membrane permeable and rapidly stain parasites within erythrocytes (which lack nuclei or mitochondria). MitoTracker dyes are only retained within active mitochondria and clearly differentiate between viable and nonviable intracellular parasites. This stain combination also allowed ring-stage parasites to be distinguished from later stages (Fig. 2A; Supplemental Fig. S2). The flow cytometry-based assay generated IC50 values comparable to the luciferase assay for the slow- and fast-acting drugs azithromycin and chloroquine, respectively (azithromycin: 24.5±0.7 nM with luciferase vs. 22.3±1.2 nM with flow cytometry; chloroquine: 6.4±1.5 nM with luciferase vs. 5.0±0.8 nM with flow cytometry; calculated from 4 independent experiments; Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Flow cytometry-based determination of antimalarial activity. A) 3D7 parasites were stained with SYBR, which becomes highly fluorescent when intercalated with nucleic acids, and MTDR, which is retained in metabolically active mitochondria. Uninfected erythrocytes contain no nucleus, RNA, or mitochondria and thus exhibit only background levels of staining (orange circle). Untreated samples reached 4.6% parasitemia (red gate) by 96 h. Parasites can readily be gated into early (ring, green oval) and late (trophozoite/schizont, blue oval) stages with this stain combination (see also Supplemental Fig. S2). Cultures treated with 125 nM azithromycin exhibited a population of nonviable parasites that stained positive for SYBR but exhibited low to negative MTDR signal. RBC, red blood cell. B) Flow-based drug assays, using the combination of MTDR and SYBR, generated comparable IC50 values to luciferase assays, with no statistical difference observed after 4 experiments (paired t test).

Validation screen

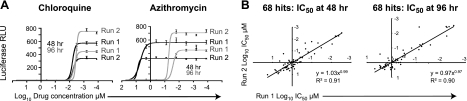

We defined compounds that induce delayed death as those that exhibited at least a 10-fold increase in potency when incubation time was increased from 1 to 2 generations of intraerythrocytic development (from 48 to 96 h). As a proof of principle, we tested the NIH Clinical Collection, a library of 446 clinically investigated compounds. These were subjected to a quantitative HTS, such that each compound was assayed at 7 concentrations diluted in 5-fold increments, starting from 50 μM and ending at 3.2 nM. Quantitative HTS has much lower false positive and false negative rates than single concentration screens (30), and this method allowed us to calculate IC50 values for each compound. Collaborative Drug Discovery online software was used to derive IC50 values by curve fitting. Hits were defined as compounds with an IC50 value ≤ 2 μM and ≥90% growth inhibition at 10 μM. Each plate included 8 control wells with no drug that were averaged to define a maximal growth signal. Each plate additionally contained dilution series for azithromycin, which targets the apicoplast 50S ribosomal subunit (18), and chloroquine, which interferes with heme detoxification in the parasite's digestive vacuole (31). These control dilutions generated highly replicable data in each plate (chloroquine IC50: 48-h run 1=7.8±3.2 nM, run 2=6.3±1.9 nM; 96-h run 1=4.4±0.5 nM, run 2=3.7±0.4 nM; azithromycin IC50: 48-h run 1=5400±400 nM, run 2=7000±500 nM; 96-h run 1=26±1 nM, run 2=50±4 nM; data represent mean IC50 values from 10 plates; Fig. 3A). As an additional control, we added the antibiotic doxycycline directly to an empty well in one of the library plates, so that it would be handled in exactly the same manner as the other library compounds. Doxycycline is a tetracycline derivative, clinically approved for antimalarial therapy, that blocks apicoplast function apparently by binding the apicoplast-encoded 30S ribosomal subunit and inhibiting protein translation (16). The full library was screened twice at 48 and 96 h, using the 3D7-HLH line. The combined assays yielded 68 hits with IC50 values below 2 μM, with a high degree of correlation between the 2 runs (48 h: y=1.03x0.99, R2=0.91; 96 h: y=0.97x0.97, R2=0.90; Fig. 3B). The identities and analysis of the raw data from these 68 hits are available through Collaborative Drug Discovery's public access database.

Figure 3.

Screening of the NIH Clinical Collection library. This library was screened in 2 independent runs over 48 or 96 h. A) Each of the ten 384-well plates in the assay contained a titration series for the control drugs chloroquine and azithromycin. Means ± se and a best-fit curve of the luminescence (RLU, relative light units) are plotted as a function of drug concentration. Note that while chloroquine exhibited very similar dose-response profiles at 48 and 96 h, azithromycin exhibited a large gain in potency at 96 h. B) Sixty-eight compounds exhibited an IC50 value of <2 μM in one of the two screens. IC50 values for these compounds are plotted for the first vs. the second run. Assays revealed high levels of correlation (R2=0.9 for both 48 and 96 h time points).

Ten compounds exhibited antimalarial activity in the low or subnanomolar range by 48 h (Supplemental Table S1). Two of these, artemether and artesunate, are artemisinin derivatives in clinical use; these represent the only known fast-acting antimalarials in the collection. The remaining 8 compounds are cytotoxic and have been employed as antineoplastic agents. When comparing the 48 and 96 h IC50 values, 7 compounds exhibited at least a 10-fold increase in potency in the second generation, meeting our criteria for delayed death. These compounds were validated both by luciferase and by flow cytometry secondary assays. One compound was the test drug doxycycline. Three others (clarithromycin, kitasamycin, and telithromycin) are macrolide or ketolide antibiotics, structurally related to our reference drug, azithromycin. While the antimalarial activity of telithromycin has previously been described (32), kitasamycin and clarithromycin are novel antimalarials and were further investigated. Kitasamycin was the more potent, with an IC50 value of 50 ± 4 nM, while clarithromycin exhibited an IC50 of 810 ± 60 nM. Another initial hit, oxiconazole nitrate, failed to demonstrate an increased potency at 96 h on retesting, with IC50 values of 700 ± 70 and 530 ± 30 nM at 48 h and 96 h, respectively. The 2 remaining compounds (RU 24969 and fluphenazine hydrochloride) failed to demonstrate measurable activity at <2 μM on retesting. Oxiconazole nitrate and RU-24969 demonstrated poor solubility in aqueous solutions, while fluphenazine hydrochloride exhibited poor solubility in the solvent DMSO. The tendency of poorly soluble compounds to produce false positives or false negatives has been well documented (33) and is an intrinsic source of potential error in any bioassay.

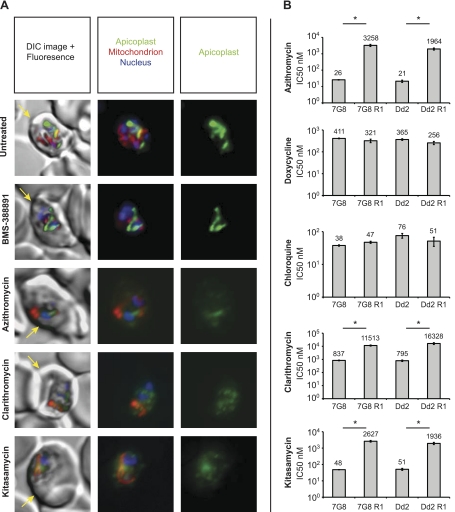

Confirmation of kitasamycin and clarithromycin action on the parasite apicoplast

To test whether kitasamycin and clarithromycin interfere with the apicoplast, we examined their effect on the morphology of this organelle. Parasites expressing GFP targeted to the apicoplast by the acyl-carrier-protein leader sequence [ACP(L)-GFP] (24) were treated for 96 h at twice the IC50 concentration of the tested compounds. As controls, we used azithromycin and BMS-388891, a protein farnesyl transferase inhibitor (34) that is not expected to interfere with the apicoplast. Chloroquine was not included as a control as viable parasites were no longer detectable by 96 h at twice its IC50 concentration. At 96 h, the apicoplasts from wild-type trophozoites had developed into elongated, branched structures (Fig. 4A). Only a few BMS-388891-treated parasites remained by 96 h; however, the apicoplasts in the surviving trophozoites looked elongated, as in the wild-type parasites (Fig. 4A). Parasites treated with azithromycin lacked a defined apicoplast structure (Fig. 4A). Instead the ACP(L)-GFP signal was present in diffuse, punctate foci throughout the cytoplasm, as has been observed with azithromycin-treated Plasmodium berghei rodent malarial parasites (12). The mitochondria in these parasites, however, still looked intact. Parasites treated with either kitasamycin or clarithromycin showed clear evidence of apicoplast disruption, recapitulating the phenotype of the azithromycin-treated parasites (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

Kitasamycin and clarithromycin mode of action. A) Parasites expressing apicoplast-targeted GFP were treated for 96 h at 2× the IC50 value for each compound. Parasites were then stained with MitoTracker Red FM and the nuclear dye Hoechst 33342. Erythrocyte peripheries were visible by differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy (yellow arrow). All of the parasites showed defined nuclei (blue) and mitochondria (red). Untreated parasites and parasites treated with the control compound BMS-388891 possessed intact, elongated apicoplasts (green). Parasites treated with azithromycin, clarithromycin, and kitasamycin exhibited disrupted apicoplasts, with the GFP distributed in a diffuse punctate pattern. B) Azithromycin-resistant parasites (7G8 R1 and Dd2 R1) and their macrolide-sensitive parental lines (7G8 and Dd2) were subjected to 96-h drug assays with the indicated compounds. Resistant and parental lines exhibited statistically significant differences in IC50 values when treated with azithromycin (7G8: P=0.02; Dd2: P=0.04), clarithromycin (7G8: P=0.01; Dd2: P<0.05), and kitasamycin (7G8: P=0.01; Dd2: P<0.01; paired t test, average of 4 experiments). *P < 0.05.

As an additional validation of target specificity, we tested the activity of kitasamycin and clarithromycin on 2 previously selected azithromycin-resistant P. falciparum lines (7G8 R1 and Dd2 R1). These mutant lines harbor a single point mutation in the apicoplast-encoded ribosomal protein L4 that is thought to block access of the drug to the 50S large ribosomal subunit (18). Both lines exhibited cross-resistance to kitasamycin and clarithromycin (Fig. 4B), indicating that these macrolides are in fact targeting the apicoplast translation machinery. As controls, we also tested these lines with doxycycline and chloroquine. Doxycycline interferes with translation in the apicoplast (16), as does azithromycin, but it belongs to the structurally unrelated tetracyclines that bind to the 30S subunit of prokaryotic ribosomes (35). Resistant lines and wild-type parental controls exhibited similar IC50 values when tested against these drugs (Fig. 4B), confirming that the resistance phenotype was specific to the macrolides.

Kitasamycin suppresses rodent malaria parasites in vivo

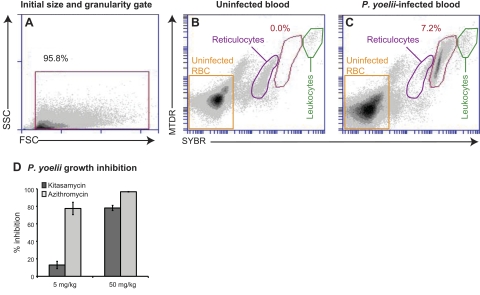

Kitasamycin has proven efficacy as an orally administered antibiotic in human clinical trials (36) and is widely used as an antibiotic in livestock (37). Given its in vitro efficacy against P. falciparum, we decided to test this agent in vivo against the rodent malaria parasite P. yoelii. Assessing parasitemias in primary blood samples by flow cytometry presents additional challenges because of the presence of nucleated leukocytes and RNA-containing reticulocytes. We evaluated several previously published techniques for assessing in vivo parasitemias, including the use of acridine orange that emits at different wavelengths when bound to RNA vs. DNA (27), dihydroethidine that is converted to ethidium in metabolically active cells (38), and RNase that eliminates background reticulocyte staining (28, 29). The most robust results were obtained using SYBR and MTDR, which rapidly stained samples and clearly detected parasitized erythrocytes (Fig. 5A–C). Leukocytes stained brightly with both reagents and were readily gated out, whereas the reticulocytes exhibited fainter staining (Fig. 5B, C). SYBR fluoresces when bound to RNA but is 1 to 2 orders of magnitude more sensitive for detecting dsDNA (39), presumably contributing to its ability to resolve infected erythrocytes from reticulocytes.

Figure 5.

Kitasamycin antimalarial efficacy in vivo. CD1 outbred mice were infected with P. yoelii parasites and treated with drug once daily, starting 2 h after the initial inoculation. At 4 d postinfection, blood samples were recovered and stained with SYBR and MTDR, and the parasitemias were determined by flow cytometry. A) Flow samples were initially gated on forward-scatter (FSC) and side-scatter (SSC) to eliminate debris. B, C) Primary uninfected (B) and infected (C) blood samples contained reticulocytes (purple gate) and leukocytes (green gate), which could be gated out based on their lower (reticulocytes) or higher (leukocytes) levels of staining relative to parasitized erythrocytes (red gate). Percentage of parasitemia is indicated in each panel. P. yoelii infects reticulocytes; therefore, this population is depleted in the infected mice. D) Mean ± se percentage growth inhibition observed with kitasamycin or azithromycin relative to mice treated with vehicle alone (assays conducted on 3 separate occasions, with 5 mice/treatment group).

Following the guidelines of the Peter's 4-d suppressive test (40), mice were infected with 107 P. yoelii parasites and 2 h later were treated with the first dose of kitasamycin or azithromycin. Mice (5/condition) received a single dose of compound daily for the next 3 d. On d 4 postinfection, parasitemias were assessed by flow cytometry. Kitasamycin suppressed parasite growth by 13 ± 4% at 5 mg/kg and 78 ± 7% at 50 mg/kg (Fig. 5D), although it did not achieve the same level of efficacy as azithromycin (78±3% at 5 mg/kg and 97±0.2% at 50 mg/kg). These data demonstrate the capacity of our assay to detect novel apicoplast-specific antimalarials with the potential for in vivo efficacy.

DISCUSSION

Currently, there are very few novel antimalarials in clinical trials that could replace the artemisinin therapies, should highly resistant parasites emerge and spread globally (41). Anticipating a long-term need for new antimalarials, we set out to develop an HTS capable of identifying compounds with a distinct mode of action from therapies used in current or previous global control efforts. The apicoplast was selected as an attractive target, as it is essential for survival and houses several biosynthetic pathways that are distinct from mammalian cells (14). These pathways include fatty acid synthesis through a type II (FAS-II) process involving 4 distinct enzymes during acyl chain elongation, unlike the multifunctional single (FAS-I) polypeptide employed by humans (42–44), as well as mevalonate-independent synthesis of isoprenoids, which serve as precursors for the synthesis of ubiquinones and dolichols and which also act as prosthetic groups for protein modifications such as prenylation (14, 45). Other processes located in the apicoplast include heme synthesis and iron-sulfur complex assembly (14).

Antibiotics known to interfere with the apicoplast ribosome have been demonstrated to be effective antimalarial agents. Doxycycline and clindamycin are both recommended by the WHO as second-line treatments for malaria when paired with fast-acting partners such as artesunate or quinine (46), while azithromycin is currently in clinical trials for intermittent preventive treatment (IPT) in pregnant women (47–49). Doxycycline is also employed as a first-line prophylactic agent on its own (50). Because of their slow mode of action, antibiotics need to be paired with fast-acting drugs to achieve rapid parasite clearance in acute infections; however, this is not as essential for applications such as prophylaxis and IPT. There are currently no reported cases of resistance to these drugs in malaria-endemic regions. Recent studies have confirmed that these antibiotics also inhibit the apicoplast in developing liver stages (12, 51). Of particular interest, mice infected with liver stages of the rodent malaria parasite P. berghei treated with clindamycin or azithromycin were protected against subsequent challenge with wild-type sporozoites (51). These studies suggest that apicoplast inhibitors can block parasites from progressing to fulminant blood stage infection while allowing the development of protective immunity against the intrahepatic parasite, creating new opportunities for antimalarial prophylaxis. Furthermore, the apicoplast has also been found to be metabolically active in female gametocytes, indicating that apicoplast inhibition may also be effective in reducing parasite transmission to Anopheles vectors (12, 52). Despite their potential advantages, antibiotics have primarily been used as second-line antimalarials and in focused therapies, such as for individuals with severe malaria (53), for IPT in pregnancy (48), and as prophylaxis in travelers (50). One concern with using antibiotics for antimalarial campaigns is that their widespread employment might select for resistant bacteria, undermining their primary clinical application. The development of potent compounds specifically intended for utilization as antimalarials would circumvent this issue.

While the screen was developed with the intention of discovering P. falciparum-specific antimicrobials, agents that also demonstrate antibacterial properties remain interesting. A number of publications have highlighted the potential benefits of using antibiotic-based combination therapies for clinical applications, including IPT and the treatment of severe malaria (48, 53). In resource-limited health care settings, bacterial septicemia can be misdiagnosed as severe malaria, and even when severe malaria is correctly diagnosed, concomitant bacterial infections can be common (53–55). In these scenarios, the antibacterial effects of an antibiotic-based combination therapy may have as great a therapeutic effect as the antimalarial effect. For both IPT and severe cerebral malaria, drug therapies are administered to a limited population in a controlled setting, helping to reduce the risk of selecting for bacterial resistance.

It is worth noting that not all inhibitors of processes inside the apicoplast are slow acting. Examples include clodinafop, which inhibits the plastid enzyme acetyl-CoA carboxylase, involved in FAS-II initiation (15), and fosmidomycin, which inhibits 1-deoxy-d-xylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase, involved in isoprenoids biosynthesis (45, 56). While these agents would not show differential activity between 48 and 96 h, they would still be identified by our assay and could be developed as antimalarials.

The ability of the assay reported herein to detect delayed death-inducing antimalarials under HTS conditions was confirmed by the NIH Clinical Collection library screen, which identified both known and novel antimalarials. Furthermore, the validation experiments using the ACP(L)-GFP parasites and the azithromycin-resistant parasites confirmed that the assay enriches for compounds specifically targeting the apicoplast. One of these compounds, kitasamycin, demonstrated efficacy in an in vivo rodent malaria model. While both of the novel antimalarials identified in this screen were antibiotics, the NIH library is limited to compounds that have been tested clinically. We predict that screens of unbiased libraries of small molecules or natural products can identify Plasmodium-specific compounds that target the apicoplast, introducing whole new classes of drugs for use as antimalarials.

The development of this HTS required the modification and refinement of a number of techniques with applications beyond their use for HTS. Both the 3D7 and Dd2 luciferase-expressing lines provide a robust, highly replicable, and nonradioactive means for assessing parasite viability, with a 20-fold higher signal to noise ratio than SYBR. The luciferase-based delayed death screen could potentially be used for other Apicomplexan parasites, such as Toxoplasma gondii, which are amenable to genetic manipulation. We also detail a simple and robust flow cytometry method for both in vitro and in vivo applications that requires no prior genetic modifications.

We envision that any delayed death-inducing drugs developed out of this screen would eventually be partnered with fast acting antimalarials capable of rapidly clearing parasites from the blood. The importance of using multidrug combination therapies to reduce the risk of antimalarial resistance has been broadly accepted within the malaria community. Currently, global antimalarial therapy programs rely heavily on a single class of compounds, the artemisinins, for which resistance may already be emerging. The artemisinins are paired with partner drugs that have known limitations including previously documented resistance (sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine, mefloquine, amodiaquine, and piperaquine; refs. 25, 57), serious side effects (mefloquine and amodiaquine; ref. 58), and suboptimal dosing regimens (lumefantrine; ref. 59). There is thus a need to develop effective partner drugs to protect primary therapeutic agents. We think that delayed death-inducing compounds could fill this important niche.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Marcus Lee, Rich Eastman, Rebecca Muhle, Lindsie Goss, and Philipp Heinrich for experimental, technical, and computational assistance. The authors also thank Bamini Jayabalasingham and Andrea Ecker for constructive comments on the manuscript. The authors are grateful to Wesley C. Van Voorhis and Michael H. Gelb (University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA) for providing BMS-388891.

This work was funded in part by the U.S. National Insitutes of Health (R21 NS059500 to D.A.F.), including support as a competitive revision application funded by the American Recovery and Investment Act of 2009. E.H.E. gratefully acknowledges support from the Life Sciences Research Foundation as a Hoffmann-La Roche Fellow.

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

REFERENCES

- 1. Aregawi M., Cibulskis R., Kita Y., Otten M., Williams R. (2010) World Malaria Report 2010, p. xii, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland [Google Scholar]

- 2. Plowe C. V. (2009) The evolution of drug-resistant malaria. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 103(Suppl. 1), S11–S14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Eastman R. T., Fidock D. A. (2009) Artemisinin-based combination therapies: a vital tool in efforts to eliminate malaria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7, 864–874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Noedl H., Se Y., Schaecher K., Smith B. L., Socheat D., Fukuda M. M. (2008) Evidence of artemisinin-resistant malaria in western Cambodia. N. Engl. J. Med. 359, 2619–2620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dondorp A. M., Nosten F., Yi P., Das D., Phyo A. P., Tarning J., Lwin K. M., Ariey F., Hanpithakpong W., Lee S. J., Ringwald P., Silamut K., Imwong M., Chotivanich K., Lim P., Herdman T., An S. S., Yeung S., Singhasivanon P., Day N. P. J., Lindegardh N., Socheat D., White N. J. (2009) Artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. N. Engl. J. Med. 361, 455–467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Silvie O., Mota M. M., Matuschewski K., Prudencio M. (2008) Interactions of the malaria parasite and its mammalian host. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 11, 352–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Greenwood B. M., Fidock D. A., Kyle D. E., Kappe S. H., Alonso P. L., Collins F. H., Duffy P. E. (2008) Malaria: progress, perils, and prospects for eradication. J. Clin. Invest. 118, 1266–1276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gamo F.-J., Sanz L. M., Vidal J., de Cozar C., Alvarez E., Lavandera J.-L., Vanderwall D. E., Green D. V. S., Kumar V., Hasan S., Brown J. R., Peishoff C. E., Cardon L. R., Garcia-Bustos J. F. (2010) Thousands of chemical starting points for antimalarial lead identification. Nature 465, 305–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Guiguemde W. A., Shelat A. A., Bouck D., Duffy S., Crowther G. J., Davis P. H., Smithson D. C., Connelly M., Clark J., Zhu F., Jiménez-Díaz M. B., Martinez M. S., Wilson E. B., Tripathi A. K., Gut J., Sharlow E. R., Bathurst I., El Mazouni F., Fowble J. W., Forquer I., McGinley P. L., Castro S., Angulo-Barturen I., Ferrer S., Rosenthal P. J., Derisi J. L., Sullivan D. J., Lazo J. S., Roos D. S., Riscoe M. K., Phillips M. A., Rathod P. K., Van Voorhis W. C., Avery V. M., Guy R. K. (2010) Chemical genetics of Plasmodium falciparum. Nature 465, 311–315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rottmann M., McNamara C., Yeung B. K., Lee M. C., Zou B., Russell B., Seitz P., Plouffe D. M., Dharia N. V., Tan J., Cohen S. B., Spencer K. R., Gonzalez-Paez G. E., Lakshminarayana S. B., Goh A., Suwanarusk R., Jegla T., Schmitt E. K., Beck H. P., Brun R., Nosten F., Renia L., Dartois V., Keller T. H., Fidock D. A., Winzeler E. A., Diagana T. T. (2010) Spiroindolones, a potent compound class for the treatment of malaria. Science 329, 1175–1180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Baniecki M. L., Wirth D. F., Clardy J. (2007) High-throughput Plasmodium falciparum growth assay for malaria drug discovery. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51, 716–723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stanway R. R., Witt T., Zobiak B., Aepfelbacher M., Heussler V. T. (2009) GFP-targeting allows visualization of the apicoplast throughout the life cycle of live malaria parasites. Biol. Cell 101, 415–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kalanon M., McFadden G. I. (2010) Malaria, Plasmodium falciparum and its apicoplast. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 38, 775–782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ralph S. A., van Dooren G. G., Waller R. F., Crawford M. J., Fraunholz M. J., Foth B. J., Tonkin C. J., Roos D. S., McFadden G. I. (2004) Tropical infectious diseases: metabolic maps and functions of the Plasmodium falciparum apicoplast. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2, 203–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zuther E., Johnson J. J., Haselkorn R., McLeod R., Gornicki P. (1999) Growth of Toxoplasma gondii is inhibited by aryloxyphenoxypropionate herbicides targeting acetyl-CoA carboxylase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96, 13387–13392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dahl E. L., Shock J. L., Shenai B. R., Gut J., Derisi J. L., Rosenthal P. J. (2006) Tetracyclines specifically target the apicoplast of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50, 3124–3131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Goodman C. D., Su V., McFadden G. I. (2007) The effects of anti-bacterials on the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 152, 181–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sidhu A. B. S., Sun Q., Nkrumah L. J., Dunne M. W., Sacchettini J. C., Fidock D. A. (2007) In vitro efficacy, resistance selection, and structural modeling studies implicate the malarial parasite apicoplast as the target of azithromycin. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 2494–2504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dharia N. V., Plouffe D., Bopp S. E., Gonzalez-Paez G. E., Lucas C., Salas C., Soberon V., Bursulaya B., Kochel T. J., Bacon D. J., Winzeler E. A. (2010) Genome scanning of Amazonian Plasmodium falciparum shows subtelomeric instability and clindamycin-resistant parasites. Genome Res. 20, 1534–1544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dahl E. L., Rosenthal P. J. (2008) Apicoplast translation, transcription and genome replication: targets for antimalarial antibiotics. Trends Parasitol. 24, 279–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Istvan E. S., Dharia N. V., Bopp S. E., Gluzman I., Winzeler E. A., Goldberg D. E. (2011) Validation of isoleucine utilization targets in Plasmodium falciparum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108, 1627–1632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nkrumah L. J., Muhle R. A., Moura P. A., Ghosh P., Hatfull G. F., Jacobs W. R., Fidock D. A. (2006) Efficient site-specific integration in Plasmodium falciparum chromosomes mediated by mycobacteriophage Bxb1 integrase. Nat. Meth. 3, 615–621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Muhle R. A., Adjalley S., Falkard B., Nkrumah L. J., Muhle M. E., Fidock D. A. (2009) A var gene promoter implicated in severe malaria nucleates silencing and is regulated by 3′ untranslated region and intronic cis-elements. Int. J. Parasitol. 39, 1425–1439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Waller R. F., Reed M. B., Cowman A. F., McFadden G. I. (2000) Protein trafficking to the plastid of Plasmodium falciparum is via the secretory pathway. EMBO J. 19, 1794–1802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ekland E. H., Fidock D. A. (2008) In vitro evaluations of antimalarial drugs and their relevance to clinical outcomes. Int. J. Parasitol. 38, 743–747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Plouffe D., Brinker A., McNamara C., Henson K., Kato N., Kuhen K., Nagle A., Adrián F., Matzen J. T., Anderson P., Nam T.-G., Gray N. S., Chatterjee A., Janes J., Yan S. F., Trager R., Caldwell J. S., Schultz P. G., Zhou Y., Winzeler E. A. (2008) In silico activity profiling reveals the mechanism of action of antimalarials discovered in a high-throughput screen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105, 9059–9064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bhakdi S. C., Sratongno P., Chimma P., Rungruang T., Chuncharunee A., Neumann H. P., Malasit P., Pattanapanyasat K. (2007) Re-evaluating acridine orange for rapid flow cytometric enumeration of parasitemia in malaria-infected rodents. Cytometry A 71, 662–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jimenez-Diaz M. B., Rullas J., Mulet T., Fernandez L., Bravo C., Gargallo-Viola D., Angulo-Barturen I. (2005) Improvement of detection specificity of Plasmodium-infected murine erythrocytes by flow cytometry using autofluorescence and YOYO-1. Cytometry A 67, 27–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Xie L., Li Q., Johnson J., Zhang J., Milhous W., Kyle D. (2007) Development and validation of flow cytometric measurement for parasitaemia using autofluorescence and YOYO-1 in rodent malaria. Parasitology 134, 1151–1162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Inglese J., Auld D. S., Jadhav A., Johnson R. L., Simeonov A., Yasgar A., Zheng W., Austin C. P. (2006) Quantitative high-throughput screening: a titration-based approach that efficiently identifies biological activities in large chemical libraries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103, 11473–11478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vinetz J. M., Clain J., Bounkeua V., Eastman R. T., Fidock D. A. (2011) Chemotherapy of malaria. In Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (Brunton L., Chabner B., Knollman B. eds) pp. 1383–1418, McGraw Hill Medical, New York [Google Scholar]

- 32. Barthel D., Schlitzer M., Pradel G. (2008) Telithromycin and quinupristin-dalfopristin induce delayed death in Plasmodium falciparum. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52, 774–777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Di L., Kerns E. H. (2006) Biological assay challenges from compound solubility: strategies for bioassay optimization. Drug Discov. Today 11, 446–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nallan L., Bauer K. D., Bendale P., Rivas K., Yokoyama K., Hornéy C. P., Pendyala P. R., Floyd D., Lombardo L. J., Williams D. K., Hamilton A., Sebti S., Windsor W. T., Weber P. C., Buckner F. S., Chakrabarti D., Gelb M. H., Van Voorhis W. C. (2005) Protein farnesyltransferase inhibitors exhibit potent antimalarial activity. J. Med. Chem. 48, 3704–3713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Carter A. P., Clemons W. M., Brodersen D. E., Morgan-Warren R. J., Wimberly B. T., Ramakrishnan V. (2000) Functional insights from the structure of the 30S ribosomal subunit and its interactions with antibiotics. Nature 407, 340–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Janbon M., Bertrand A., Pourquier M. (1963) Kitasamycin: experimental in vitro studies and first clinical results. Gaz. Med. Fr. 70(Suppl.), 9–21 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Barton M. D. (2000) Antibiotic use in animal feed and its impact on human health. Nutr. Res. Rev. 13, 279–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Van der Heyde H. C., Elloso M. M., vande Waa J., Schell K., Weidanz W. P. (1995) Use of hydroethidine and flow cytometry to assess the effects of leukocytes on the malarial parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 2, 417–425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tuma R. S., Beaudet M. P., Jin X., Jones L. J., Cheung C. Y., Yue S., Singer V. L. (1999) Characterization of SYBR Gold nucleic acid gel stain: a dye optimized for use with 300-nm ultraviolet transilluminators. Anal. Biochem. 268, 278–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Peters W. (1965) Drug resistance in Plasmodium berghei Vincke and Lips, 1948. I. Chloroquine resistance. Exp. Parasitol. 17, 80–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wells T. N., Poll E. M. (2010) When is enough enough? The need for a robust pipeline of high-quality antimalarials. Discov. Med. 9, 389–398 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kuo M. R., Morbidoni H. R., Alland D., Sneddon S. F., Gourlie B. B., Staveski M. M., Leonard L., Gregory J. S., Janjigian A. D., Yee C., Kreiswirth B., Iwamoto H., Perozzo R., Jacobs J. W. R., Sacchettini J. C., Fidock D. A. (2003) Targeting tuberculosis and malaria through inhibition of enoyl reductase: compound activity and structural data. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 20851–20859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. McLeod R., Muench S. P., Rafferty J. B., Kyle D. E., Mui E. J., Kirisits M. J., Mack D. G., Roberts C. W., Samuel B. U., Lyons R. E., Dorris M., Milhous W. K., Rice D. W. (2001) Triclosan inhibits the growth of Plasmodium falciparum and Toxoplasma gondii by inhibition of apicomplexan Fab I. Int. J. Parasitol. 31, 109–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Waller R. F., Keeling P. J., Donald R. G., Striepen B., Handman E., Lang-Unnasch N., Cowman A. F., Besra G. S., Roos D. S., McFadden G. I. (1998) Nuclear-encoded proteins target to the plastid in Toxoplasma gondii and Plasmodium falciparum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95, 12352–12357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jomaa H., Wiesner J., Sanderbrand S., Altincicek B., Weidemeyer C., Hintz M., Turbachova I., Eberl M., Zeidler J., Lichtenthaler H. K., Soldati D., Beck E. (1999) Inhibitors of the nonmevalonate pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis as antimalarial drugs. Science 285, 1573–1576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Olumese P. (2010) Guidelines for the Treatment of Malaria. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kalilani L., Mofolo I., Chaponda M., Rogerson S. J., Alker A. P., Kwiek J. J., Meshnick S. R. (2007) A randomized controlled pilot trial of azithromycin or artesunate added to sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine as treatment for malaria in pregnant women. PLoS One 2, e1166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chico R. M., Pittrof R., Greenwood B., Chandramohan D. (2008) Azithromycin-chloroquine and the intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy. Malar. J. 7, 255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Luntamo M., Kulmala T., Mbewe B., Cheung Y. B., Maleta K., Ashorn P. (2010) Effect of repeated treatment of pregnant women with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine and azithromycin on preterm delivery in Malawi: a randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 83, 1212–1220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tan K. R., Magill A. J., Parise M. E., Arguin P. M. (2011) Doxycycline for malaria chemoprophylaxis and treatment: report from the CDC expert meeting on malaria chemoprophylaxis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 84, 517–531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Friesen J., Silvie O., Putrianti E. D., Hafalla J. C., Matuschewski K., Borrmann S. (2010) Natural immunization against malaria: causal prophylaxis with antibiotics. Sci. Transl. Med. 2, 40ra49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Okamoto N., Spurck T. P., Goodman C. D., McFadden G. I. (2009) Apicoplast and mitochondrion in gametocytogenesis of Plasmodium falciparum. Eukaryot. Cell. 8, 128–132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Noedl H. (2009) ABC - antibiotics-based combinations for the treatment of severe malaria? Trends Parasitol. 25, 540–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Berkley J., Mwarumba S., Bramham K., Lowe B., Marsh K. (1999) Bacteraemia complicating severe malaria in children. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 93, 283–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Berkley J. A., Lowe B. S., Mwangi I., Williams T., Bauni E., Mwarumba S., Ngetsa C., Slack M. P., Njenga S., Hart C. A., Maitland K., English M., Marsh K., Scott J. A. (2005) Bacteremia among children admitted to a rural hospital in Kenya. N. Engl. J. Med. 352, 39–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Dharia N. V., Sidhu A. B., Cassera M. B., Westenberger S. J., Bopp S. E., Eastman R. T., Plouffe D., Batalov S., Park D. J., Volkman S. K., Wirth D. F., Zhou Y., Fidock D. A., Winzeler E. A. (2009) Use of high-density tiling microarrays to identify mutations globally and elucidate mechanisms of drug resistance in Plasmodium falciparum. Genome Biol. 10, R21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Eastman R. T., Dharia N. V., Winzeler E. A., Fidock D. A. (2011) Piperaquine resistance is associated with a copy number variation on chromosome 5 in drug-pressured Plasmodium falciparum parasites. [Epub ahead of print] Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. PMID: 21576453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. AlKadi H. O. (2007) Antimalarial drug toxicity: a review. Chemotherapy 53, 385–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Schoepflin S., Lin E., Kiniboro B., DaRe J. T., Mehlotra R. K., Zimmerman P. A., Mueller I., Felger I. (2010) Treatment with coartem (artemether-lumefantrine) in Papua New Guinea. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 82, 529–534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.