Abstract

The purpose of this study was the prospective comparison of objective and subjective effects of target volume region of interest (ROI) delineation using mouse–keyboard and pen–tablet user input devices (UIDs). The study was designed as a prospective test/retest sequence, with Wilcoxon signed rank test for matched-pair comparison. Twenty-one physician-observers contoured target volume ROIs on four standardized cases (representative of brain, prostate, lung, and head and neck malignancies) twice: once using QWERTY keyboard/scroll-wheel mouse UID and once with pen–tablet UID (DTX2100, Wacom Technology Corporation, Vancouver, WA, USA). Active task time, ROI manipulation task data, and subjective survey data were collected. One hundred twenty-nine target volume ROI sets were collected, with 62 paired pen–tablet/mouse–keyboard sessions. Active contouring time was reduced using the pen–tablet UID, with mean ± SD active contouring time of 26 ± 23 min, compared with 32 ± 25 with the mouse (p ≤ 0.01). Subjective estimation of time spent was also reduced from 31 ± 26 with mouse to 27 ± 22 min with the pen (p = 0.02). Task analysis showed ROI correction task reduction (p = 0.045) and decreased panning and scrolling tasks (p < 0.01) with the pen–tablet; drawing, window/level changes, and zoom commands were unchanged (p = n.s.) Volumetric analysis demonstrated no detectable differences in ROI volume nor intra- or inter-observer volumetric coverage. Fifty-two of 62 (84%) users preferred the tablet for each contouring task; 5 of 62 (8%) denoted no preference, and 5 of 62 (8%) chose the mouse interface. The pen–tablet UID reduced active contouring time and reduced correction of ROIs, without substantially altering ROI volume/coverage.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10278-010-9341-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: User interface, User–computer interface, Workflow, Workflow reengineering, Radiation oncology, Radiotherapy, Observer variation, Observer performance, Imaging informatics, Human–computer interaction

Introduction

In modern radiotherapy, regions of interest (ROIs) designating tumor volumes for dose prescription are manually defined by human users, introducing possible geometric variability due to variation in target delineation. As the initial step in the treatment planning process, appropriate target delineation is the vital basis of precise treatment delivery. The most conformal radiotherapy plan, delivered with impeccable positional verification, is of little consequence if the prescription ROIs within the treatment planning software do not accurately depict tumor structures in 3D space [1]. Despite this great import, comparatively few data have been generated regarding the strategic optimization of target delineation tasks.

The vast majority of target delineation is performed on computer software developed by radiotherapy manufacturers, performed using standard personal computer hardware and peripheral devices. While these commercial units may have platform-specific modifications with regard to imaging display, key functions, or mouse strokes, almost invariably, treatment planning systems have traditionally utilized a mouse-based user input device (UID) and screen-based display system. The typical computer keyboard–mouse–screen arose as an outgrowth of previous information systems (e.g., typewriting, word and field data entry) and was not initially designed for the manipulation of complex visual datasets. Consequently, while familiar, this ubiquitous system may be suboptimal for specific image-based tasks required for precise target delineation. Previous human–computer interaction have demonstrated that pen–tablet UIDs have demonstrated performance advantages compared to a mouse for tasks resembling target volume delineation [2].

We hypothesized that the use of an improved UID interface would result in the reduction of contouring tasks, faster contouring times, and subjective preference for a tablet–pen interface. Consequently, we have undertaken a prospective, multisite study to investigate the utility of UID modification for target volume delineation.

The specific aims of this study include:

- Examination of the impact of distinct UID (pen–tablet compared to mouse–keyboard) interfaces on ROI delineation tasks, as defined by:

- Task analysis of software-recorded objective inputs

- Analysis of software-recorded objective contouring time and subject-reported contouring duration

- Survey reports of subjective experience and UID preference

Assessment of potential intra- and inter-observer volumetric differentials attributable to said UIDs

Materials and Methods

Research Approval and Study Design

The current study was conducted under the auspices of The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, under IRB no. 20080166E, as an exempt study. All patient DICOM images/files were anonymized to comply with HIPAA-specified requirements. The study was designed as a prospective test/retest sequence, with matched-pair comparison planned for continuous variables for a non-Bonferroni-corrected paired Wilcoxon rank-order test. Power calculations were performed with G*Power 3 statistical software [3] for the parametric equivalent of the paired Wilcoxon signed-rank test (e.g., paired t test, assuming a minimum possible asymptotic relative efficiency of 0.864) [4] using an a priori 1 − β = 0.8, two-tailed α = 0.05, with a specified effect size of 0.8; this resulted in a requisite minimum sample size of 14 observers in each comparison arm.

UID Implementation

At selected institutions (The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX; Netherlands Cancer Institute–Antoni van Leeuwenhoek Hospital, Amsterdam, the Netherlands; Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR; The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX), a commercial UID with a wireless pen and screen display tablet (DTX 2100, Wacom, Inc., Vancouver, WA, USA) interface was installed on an existing radiotherapy treatment planning workstation (Fig. 1). At each radiotherapy workstation, an off-the-shelf commercially available QWERTY keyboard and optical two-button scroll wheel mouse were also in place (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA; Dell Computers, Austin, TX, USA). Individual faculty and residents at each institution were given a 15-min orientation on use of the devices. The pen–tablet and mouse–keyboard UIDs were available for daily radiotherapy plan ROI contouring during an acclimation phase for 3 months thereafter, to minimize the effects of a possible procedural learning curve, before the initiation of the test/retest sequence. Observers were instructed, if possible, to perform all ROI contouring tasks on the same workstation (e.g., using the tablet as a display screen for the mouse–keyboard cases) to minimize differentials attributable to image display parameter variability.

Fig. 1.

UID configuration at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio; mouse–keyboard UID arrangement is shown on the left (a), with pen–tablet UID shown one the right (b)

Case Selection and Target Delineation Software

An expert-selected CT DICOM study case was procured and anonymized [5] for each of the following sites: head and neck, lung, brain, and prostate. Included with each case was a secondary DICOM image set consisting of a fused MRI for the brain and prostate cases and fused PET scan for the head and neck and lung cases. For each image set, a fictional standardized case presentation (representative of common clinical situations) and ROI structure set instructions were created (see Electronic Supplementary Material). Observers were sent to study the documentation which included a standardized case report, description of target volumes to be contoured, and a compact disc (CD) containing reconstructions of 3-mm axial CT images derived from the DICOM file of the standardized case study’s simulation CT to be contoured twice within the Big Brother (BB) target delineation software program. Big Brother [6–8] (J. Duppen et al., Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam, NL) is a self-contained software interface showing axial, sagittal, and coronal reconstructions, along with window/level, slice selection, and ROI contouring tools common to standard radiotherapy treatment planning systems (Fig. 2). Additionally, BB has the capacity to reconstruct fusion datasets of supplementary DICOM-derived images, which were included for each case (e.g., fused MRI images for brain and prostate, PET/CT for lung and head and neck cases). BB consists of a user interface with target delineation features common to most commercial treatment planning systems and collects a wide array of volumetric and target delineation data unobtrusively during the contouring session. BB also collects task-specific contouring data, such as number of ROI drawing tasks (defined as ROI point placement on an axial CT slice using the drawing tool), ROI corrections (designated as erasing, moving, or altering an ROI point on an axial CT slice, or erasing an ROI from an axial slice or image set), window/level changes, zoom, and scrolling/panning commands.

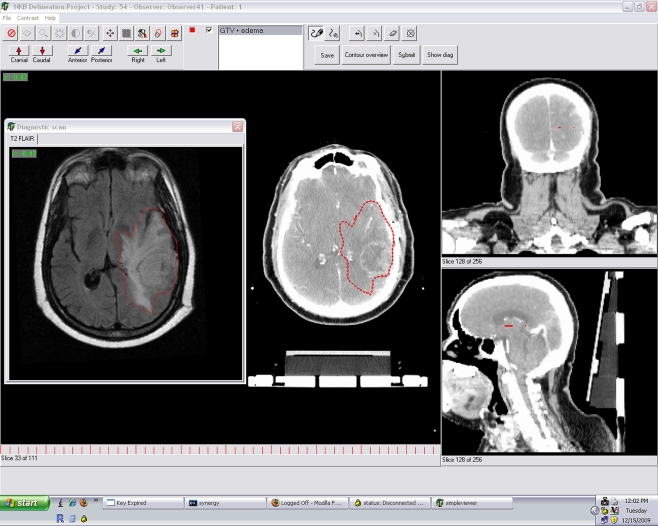

Fig. 2.

Representative screen image from Big Brother software for brain case showing fused MR (superimposed window at left) and representative target volume ROI, outlined in red

Drawing/editing tasks were defined by the GUI such that after the drawing mode was selected (by mouse right click or pen tap), an ROI would be delineated as a continuous series of points on an axial image slice. ROI delineation was initiated with the depression of the left mouse button or touching of the pen tip to the tablet device. The ROI was then drawn as a continuous series of points until right mouse release or lifting of the pen from the tablet. A secondary command/pop-up menu was initiated by right clicking the mouse or depressing a click button on the pen. For all ROI drawing/editing/erasing tasks, left mouse button depression and pen–tablet contact were deemed equivalent inputs, with left mouse release and pen tip lifting likewise correlated. Scrolling functions with the mouse scroll wheel were mapped to bilateral touch strips on either side of the screen of the tablet device. Scrolling/panning commands using the keyboard (PgUp/PgDN) were mapped to touch keys on either side of the screen of the tablet device. After entering a participant ID to unlock each contouring session, the keyboard was not used for pen–tablet contouring. All contours were completed in full-screen mode. Tasks were demarcated as commands initiated by left mouse depression/pen–tablet contact and terminated by left mouse release/pen elevation for drawing/correcting tasks.

Big Brother also collected software-recorded active contouring time, defined as the interval from user login to plan completion, excepting intervals of inactivity >30 s (e.g., if a keystroke, mouse, or pen command has not occurred for 30 s, the interval until the next keystroke/command is not recorded).

Distributed CDs contained an automated HTML link which, after electronic submission of all contouring session ROIs for central review, initiated a subsequent electronic survey.

Target Volume ROI Delineation and Analysis

Observers were invited to contour specified target volume ROIs using standardized instructions using both a standard keyboard–mouse interface and the installed pen–tablet UID. Observers were instructed to use the same workstation or an equivalent model screen–keyboard mouse combination to that on which the pen–tablet UID had been installed. Observers were allowed to contour the cases in any order over a period of 9 months. After the completion of each case, the online survey queried education level, site-specific expertise, contouring difficulty, estimated contouring active time, and device preference for each case.

Survey results, time, and ROI delineation data were collected electronically and centrally reviewed by study coordinators (CDF, CRNR, JCD). Survey results and task measures were tabulated. Data analysis was performed to evaluate potential differences between tablet and pen contouring. Measures evaluated included observer UID preference, total observer-reported contouring time, total software-recorded contouring time (minus pauses of >30 s), total volume (in cm3) of gross tumor volume (GTV) ROIs, and intra-observer GTV ROI volumetric conformation.

Volumetric conformation was assessed using a modification of the van’t Riet et al. [9, 10] conformation number (CN) which was derived as  where CV is the common volume of two observer ROIs and V1 and V2 represent the total volume of a respective ROI. Consequently, a CN = 1 indicates 100% volumetric conformance between ROIs. Intra-observer conformation was assessed using paired pen–tablet ROI volume (in cm3) for V1 and mouse–keyboard ROI volume (in cm3) for V2 for the same observer. Inter-observer agreement was assessed by calculating the mean CN of each observer’s GTV ROI as compared to all other observer GTV ROIs for the specified anatomic site, substratified by UID. Measured values >5SD from the cohort mean were deemed extreme outliers and censored from subsequent analysis.

where CV is the common volume of two observer ROIs and V1 and V2 represent the total volume of a respective ROI. Consequently, a CN = 1 indicates 100% volumetric conformance between ROIs. Intra-observer conformation was assessed using paired pen–tablet ROI volume (in cm3) for V1 and mouse–keyboard ROI volume (in cm3) for V2 for the same observer. Inter-observer agreement was assessed by calculating the mean CN of each observer’s GTV ROI as compared to all other observer GTV ROIs for the specified anatomic site, substratified by UID. Measured values >5SD from the cohort mean were deemed extreme outliers and censored from subsequent analysis.

Results

The self-reported level of training and expertise for all observers is listed in Table 1. A total of 25 individual observers submitted at least one contouring session. However, four observers used only one UID (mouse–keyboard); their results were omitted from all subsequent analyses. From the remaining 21 observers who completed at least one anatomic case with both UIDs, there were 129 submitted contour sets. A total of 124 contours were available from 62 paired sessions (e.g., where both paired mouse–keyboard and pen–tablet contours for a specified organ site) received, with five unpaired case sessions.

Table 1.

Observer-reported position and site-specific expertise

| Cohort | Position | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| All observers | 25 (100) | |

| Residents | 12 (48) | |

| PGY2/R1 | 4 (16) | |

| PGY3/R2 | 2 (8) | |

| PGY4/R3 | 5 (20) | |

| PGY5/R4 | 1 (4) | |

| Faculty/fellows | 13 (52) | |

| Non-expert | 0 (0) | |

| Brain expertise | 2 (8) | |

| Prostate expertise | 4 (16) | |

| Lung expertise | 4 (16) | |

| Head and neck expertise | 3 (12) |

Observers rated the head and neck case as the most difficult, with a majority of responses stating the case was either “Somewhat difficult” or “Difficult”; in contrast, the prostate case was deemed “Somewhat easy” or “Easy” in more than 90% of responses (Table 2).

Table 2.

Number (and percentile responses) to query “Indicate the relative difficulty of the contouring session you just completed,” stratified by anatomic site

| Brain | Head and neck | Lung | Prostate | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of survey responses | 34 | 22 | 32 | 33 | 129 |

| Easy | 5 (15) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 19 (58) | 25 (21) |

| Somewhat easy | 17 (50) | 3 (14) | 7 (22) | 12 (26) | 39 (32) |

| Average | 10 (29) | 6 (27) | 9 (28) | 1 (3) | 26 (22) |

| Somewhat difficult | 2 (6) | 11 (50) | 10 (31) | 1 (3) | 24 (20) |

| Difficult | 0 (0) | 2 (9) | 5 (16) | 0 (0) | 7 (6) |

After completing ROI tasks with both the mouse–keyboard and pen–tablet UIDs, for 62 paired cases, when queried “If you had to choose between using a tablet or mouse for the contouring process on a case similar to the one you just completed, which device would you choose?” 52 of 62 users selected the tablet, 5 of 62 denoted no preference, and 5 of 62 chose the mouse interface.

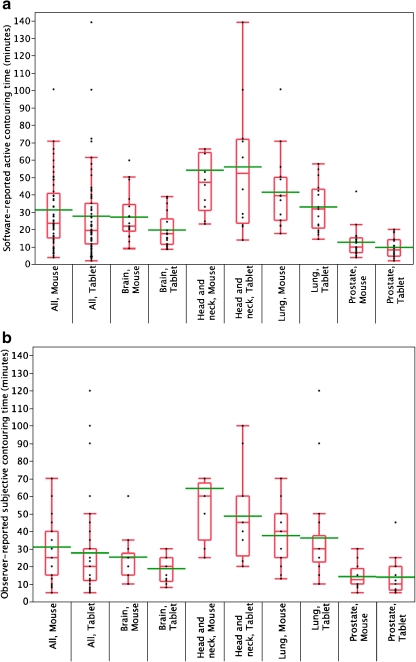

Time parameter analysis revealed a statistically significant reduction in ROI contouring time using the tablet (Fig. 3). The mean ± SD active contouring time with the mouse was 31.7 ± 24.7 min (range 4–145) compared to 26.1 ± 22.5 min (range 2–139) with the tablet (paired Wilcoxon, p ≤ 0.01). The average active contouring time saved with tablet usage was 6.2 min per case (95% CI 2.9–9.8). Likewise, subjective estimation of time spent contouring was reduced using the tablet device, with a mean ± SD observer-reported subjective mouse contouring time of 30.8 ± 25.8 min (range 5–160) for all cases compared to 27.0 ± 21.8 min (range 5–120) for the tablet (paired Wilcoxon, p = 0.02). This resulted in an average perceived reduction in ROI contouring time of 5.5 min (CI 0–10.1 min).

Fig. 3.

Quantile boxplot of distribution of objective (a) and subjective (b) time parameters, substratified by anatomic case and UID. Whiskers represent the 0–100th percentile range, box encompassing 25th and 75th percentiles. Median is indicated by horizontal line within box, with mean line in green

Task analysis (Table 3) revealed the number of ROI drawing tasks to be non-different between mouse and tablet (p = 0.14, n.s.); however, the number of ROI correction tasks was reduced to a statistically detectable degree (p = 0.045), by an average of 8%. The frequency of window/level changes (p = 0.53, n.s.) and image zoom commands (p = 0.72, n.s.) were indistinct between UIDs; however, the frequency of panning/scrolling tasks was reduced by 23% (p < 0.001) with tablet compared to mouse usage.

Table 3.

Mean ± SD, for software-recorded target delineation tasks, in number of tasks

| Task description | Mouse (no. of tasks) | Tablet (no. of tasks) |

|---|---|---|

| Contouring/drawing | 102 ± 89 | 112 ± 101 |

| Correctiona | 127 ± 170 | 98 ± 113 |

| Movement/panning/scrolling/localization | 3,209 ± 2,853 | 2,363 ± 2,041 |

| Window/level/contrast adjustmenta | 952 ± 1,806 | 639 ± 1,319 |

| Zoom | 209 ± 378 | 265 ± 723 |

Matched-pair Wilcoxon test was performed for paired cases

aStatistically significant difference at the p ≤ 0.05 level

Paired GTV ROI volumes for each user were not substantially different (p = 0.29, n.s.) between mouse and tablet sessions (Table 4). Mean intra-observer CN between pen–tablet tasks was 0.77 (CI 0.75–0.80), suggesting that observers were relatively reproducible across UIDs for all cases. Likewise, comparison of inter-observer agreement (Table 4) demonstrated no substantial difference (p = 0.09, n.s.) between input UIDs in terms of group agreement. However, analysis revealed a markedly poorer probability of covering the same voxel(s) as previously contoured, or as contoured by other users, which was noted in both pen–tablet and mouse–keyboard sessions for the head and neck case compared to other tested anatomic sites (Table 4).

Table 4.

Mean volume, intra- and inter-observer conformation number, stratified by anatomic site (95% CI in parentheses)

| GTV ROI volume (cm3, mouse–keyboard) | GTV ROI volume (cm3, pen–tablet) | GTV ROI intra-observer CN | GTV ROI inter-observer CN (mouse–keyboard) | GTV ROI inter-observer CN (pen–tablet) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | – | – | 0.77 (0.75–0.80) | 0.69 (0.65–0.71) | 0.69 (0.64–0.71) |

| Brain | 210.8 (191–228) | 205.7 (191–220) | 0.85 (0.83–0.97) | 0.79 (0.77–0.82) | 0.80 (0.78–0.82) |

| Prostate | 43.4 (39–48) | 43.0 (37–49) | 0.76 (0.72–0.81) | 0.68 (0.66–0.70) | 0.67 (0.64–0.70) |

| Lung | 377.8 (345–409) | 408.3 (373–442) | 0.79 (0.77–0.81) | 0.67 (0.66–69) | 0.66 (0.64–0.68) |

| Head and neck | 20.2 (15–25) | 18.9 (14–24) | 0.61 (0.56–0.66) | 0.47 (0.42–0.52) | 0.47 (0.40–0.54) |

CN = 1 indicates 100% volume overlap, CN = 0 denotes complete disagreement

Discussion

In radiotherapy treatment planning, target delineation is the premise of accurate and precise treatment delivery. Delineating treatment targets within DICOM files is complex, operator-dependent, and critical to the accurate delivery of conformal radiotherapy [11–15]. These variabilities in target volume delineation can be a major primary source of inaccuracy of dose delivery and treatment errors [16]. Consequently, efforts have been made to identify processes in the target delineation process amenable to improvement, such as multimodality image incorporation [8, 17–22], instructional modification [23–25], visual atlas usage [11–15, 26, 27], window-level adjustment [28], auto-segmentation [29, 30], and software-assisted contouring [25]. While specialized data entry mechanism for spatial data is common in other arenas (e.g., video games [31] and virtual simulation workstations [32, 33]), there have been comparatively few efforts to modify ROI definition at the hardware level in radiotherapy.

Previously, ergonomic analysis by Kotani and Horii [2] compared pen–tablet and mouse UIDs, demonstrating improved performance by pen–tablet UID on standardized repetitive computer drawing tasks (e.g., clicking, drag–dropping) and polygon tracing. The same series demonstrated EMG-detected reduction in muscular load to the flexor digitorum superficialis, extensor digitorum, and biceps brachii. Since, in its basic form, ROI outlining approximates polygon tracing as a fine motor task, evaluation of a pen–tablet UID was performed in this study.

The presented data suggest that specific aspects of the target volume ROI delineation process, across a range of tumor types and anatomic sites, are differentially impacted by the transition to a pen–tablet from a mouse–keyboard data entry system.

Both objectively measured active contouring time (e.g., excluding pauses >30 s in length) and subjectively estimated time contouring were reduced by a statistically detectable degree. However, the time savings did not appear to scale with total time required for each task and did not appear directly related to perceived case difficulty (Tables 2 and 3). The use of the pen–tablet UID was associated with a reduced number of corrective actions by individual users as well as reduced panning/scrolling functions, without reducing the frequency of contouring/drawing tasks recorded. Thus, it appears that the use of the pen–tablet results in ROIs that, while containing the same approximate number of drawn points, are less likely to be subsequently corrected than mouse-entered ROIs. The collected data also reveal no statistically detectable difference between pen–tablet and mouse–keyboard entry GTV ROI volume(s) for paired measurements (Table 4). Likewise, intra-observer and inter-observer CN values were roughly comparable to those seen in a previous series [26], suggesting that the ROI volumes designated were only minimally altered in a systematic manner based on data entry UID.

Subjectively, observers overwhelmingly preferred the pen–tablet entry system. Using collected data (Table 2) as an ordinal scale, observers rated cases contoured with the pen–tablet as comparatively easier (paired Wilcoxon signed-rank test, p = 0.04). Also, respondents were surprisingly accurate at time estimation, with a median difference between estimated and actual time spent delineating of <5 min. Consequently, not only was contouring with the pen objectively faster, but observers perceived the interface as faster.

While interest in target volume delineation has expanded in the conformal radiotherapy era, image perception evaluations [34–37], workstation design [38–40], and UID alteration [41, 42] have been less formally addressed than in diagnostic radiology. For example, Weiss et al. performed an evaluation comparing technologies used in diagnostic radiology. They compared QWERTY keyboard scroll wheel mouse to six different alternative UIDs (including five-button mouse, eight-button mouse, gyroscopic mouse, multimedia controller, handheld mouse/keyboard combination UID, and a gaming joystick) and found the standard mouse keyboard UID least favorable. In a similar study, Sherbondy et al. [41] evaluated trackball, pen–tablet, jog–shuttle wheel, and mouse UIDs, finding the pen–tablet UID, in two distinct configurations, to perform faster than the mouse and trackball UIDs, respectively, at a simulated angiography localization task.

However, most literature on UID modification in diagnostic radiology literature focuses on scrolling, ROI localization/identification [41], and annotation [43] rather than target delineation, as in radiotherapy. Dowsett et al. [44] reported a series of two gastro-/esophageal cancer cases, contoured by nine observers across several treatment planning systems (TPS). The treatment planning systems implemented distinct interface UIDs, including mouse–keyboard interface, light pen, and trackball input UIDs. In the Dowsett series, the TPS attached to each input UID was varied such that only a light pen and trackball could be compared on the same treatment planning system. Notably, in the present series, the use of the BB software substantially standardizes the contouring process such that all users were working with a common target delineation platform rather than on their typical institution-specific clinical workstations. Consequently, reflected task time estimates might be different with daily implementation on a commercially available TPS used regularly by the observer(s). More recently, Larsson et al. [45] presented two abstracts comparing mouse–keyboard and the same pen–tablet model in this series using geometric shapes, as well as a lumbar vertebra [45], as contoured by physicians, nurses, radiotherapists/dosimetrists, physicists, and administrative staff. In each case, the authors reported the pen–tablet interface to be faster at drawing tasks. Interestingly, they also observed that radiation oncologists were the slowest performers of ROI contouring tasks. The presented findings of this series, using more elaborate target volume-specific tasks designed to approximate clinical cases, correlate with those observed in simple geometric/anatomical shapes by Larsson et al. Work by Anderlind et al. [46], using a pen UID with haptic feedback, furthermore suggests that the addition of tactile information might even further improve contouring efficiency.

Despite being the largest prospective UID comparison in therapeutic treatment planning, several caveats of this study are apparent; our sample size, though cumulatively robust, was limited to a selected subset of institutions, resulting in potential selection bias. Though multiple cases from distinct anatomic locations and different perceived task difficulty were used, the limited number of cases in each site limits broad applicability. Additionally, the use of non-parametric analyses owing to sample size considerations, the presence of several statistical outliers in the dataset (Figs. 2 and 3), and multiple non-Bonferroni-corrected comparisons, might make excessive generalization of the results erroneous. It is also noteworthy to consider these caveats in light of the large range of contouring times, the presence of several outliers (Fig. 1), and the observations that times for contouring varied substantially for distinct cases (e.g., prostate case contouring was markedly faster than the head and neck case, regardless of device) and that individual users exhibited inter-observer differences in contouring speed severalfold greater than intra-observer UID-associated time improvement.

We did not survey participants for degree of familiarity nor preference with either UID before the study, which might also serve as an unidentified source of bias. By allowing users to contour cases in an order of their choosing, potential learning effects might be obfuscated. Thus, we sought to ascertain if contouring order was systematically by post hoc split-plot ANOVA analysis of active contouring time, UID, and both absolute (e.g., order of submitted contour sets for all four anatomic sites) and relative order (e.g., first or second contour submission for each organ site). In secondary analysis, neither absolute (F test, p = 0.46) nor relative order of completion (F test, p = 0.14) was found to be associated with a paired user difference in active contouring time.

Despite the stated limitations, our data demonstrate that modification of the input UID can detectably alter ROI delineation tasks. Specifically, in the tested cases, pen–tablet use was associated with decrement in active contouring time, perceived contouring time, perceived case difficulty, number of corrective actions, and number of panning functions while leaving ROI drawing and volumetric measures unaltered. In sum, the use of a pen–tablet device resulted in improved efficiency in ROI delineation tasks. These data suggest potentially appreciable savings in terms of physician time commitment. For instance, using the number of conformal/IMRT cases performed annually between 2006 and 2007, derived from site-specific (brain, prostate, head and neck, lung) numbers of conformal radiotherapy cases at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio and using time savings between input UIDs from the current dataset for each anatomic site, an estimated average ± SE of 1,335 ± 916 min (22 ± 15 h) of direct physician work time might have been saved annually from target volume delineation alone (e.g., not including normal structure/OAR ROI input or other time components of the treatment planning process) [47] at a single participating site. Consequently, while time savings are obviously dependent on the number of cases, case mix, case complexity, and departmental size, among other factors, considerable institutional efficiency gains might potentially be realized from input UID optimization, especially given the relative time reimbursement costs for radiation oncologists [48].

Finally, our data point to a need for a more developed analysis of image perception and human–computer interface evaluation specifically evaluating target volume delineation. It is imperative that future studies optimize technical parameters for accurate dose prescription. While this series did not directly evaluate clinical outcomes, it is possible that distinct display or human–computer interfaces might conceivably alter radiotherapy dose prescriptions sufficient to result in clinically meaningful sequelae, though such evaluation would require more robust numbers of cases.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Full case description/instructions for ROI delineation for each of the anatomic sites (brain, prostate, lung, and head and neck) (PDF 126 kb)

Acknowledgments

The corresponding author received research funding through a Resident Research Grant from the Radiological Society of North America Education and Research Foundation (RR0732) and from the National Institutes of Health (National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering [5T32EB000817-04] and National Cancer Institute Clinical Research Loan Repayment Program [L30 CA136381]). Pen–tablet devices were provided as a loan-in-kind for the duration of the study by Wacom, Inc. (Vancouver, WA). These funders had no role in study design, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, nor in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

The following collaborators contributed to the current report: Coen R.N. Rasch, MD, PhD, Joop C. Duppen, Ing., Roel J. Steenbakkers, MD, PhD (Department of Radiation Oncology, Netherlands Cancer Institute-Antoni van Leeuwenhoek Hospital, Amsterdam, NL); Daniel Baseman, MD, Tony Y. Eng, MD, Clifton D. Fuller, MD, Anna M. Harris, MD, William E. Jones, III, MD, Ying Li, MD, PhD, Elizabeth Maani, MD, Dominic D. Nguyen, MD, MBA, Gregory P. Swanson, MD (Department of Radiation Oncology, The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX, USA); Celine Bicquart, MD, Patrick Gagnon, MD, MS, John Holland, MD, Tasha McDonald, MD, Charles R. Thomas, Jr., MD, Samuel J. Wang, MD, PhD, Martin Fuss, MD, PhD (Department of Radiation Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR, USA); Hadley J. Sharp, MD, Michelle Ludwig, MD, David I. Rosenthal, MD (Department of Radiation Oncology, The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA); Aidnag Z. Diaz, MD (Department of Radiation Oncology, Rush University, Chicago, IL, USA); Carlo G.N. Demandante, MD (Radiation Oncology Flight, Wilford Hall Medical Center, Lackland Air Force Base, San Antonio, TX, USA); Ronald Shapiro, MD (Department of Radiation Oncology, Indiana University, Indianapolis, IN, USA).

References

- 1.Rasch C, Steenbakkers R, Herk M. Target definition in prostate, head, and neck. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2005;15:136–145. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kotani K, Horii K. An analysis of muscular load and performance in using a pen–tablet system. J Physiol Anthropol Appl Hum Sci. 2003;22:89–95. doi: 10.2114/jpa.22.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Meth. 2007;39:175–191. doi: 10.3758/BF03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feustal E, Davisson L. The asymptotic relative efficiency of mixed statistical tests. IEEE Trans Inf Theory. 1967;13:247–255. doi: 10.1109/TIT.1967.1053980. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosset A, Spadola L, Ratib O. OsiriX: an open-source software for navigating in multidimensional DICOM images. J Digit Imaging. 2004;17:205–216. doi: 10.1007/s10278-004-1014-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duppen JC, Steenbakkers RJHM, Fitton I, et al. Delineation software for teaching in target volume definition. Radiother Oncol. 2004;73:S437–S438. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steenbakkers R, Duppen J, Fitton I, et al. Observer variation in target volume delineation of lung cancer related to radiation oncologist–computer interaction: a ‘Big Brother’ evaluation. Radiother Oncol. 2005;77:182–190. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2005.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steenbakkers RJ, Duppen JC, Fitton I, et al. Reduction of observer variation using matched CT-PET for lung cancer delineation: a three-dimensional analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64:435–448. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van’t Riet A, Mak AC, Moerland MA, Elders LH, Zee W. A conformation number to quantify the degree of conformality in brachytherapy and external beam irradiation: application to the prostate. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;37:731–736. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(96)00601-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feuvret L, Noel G, Mazeron JJ, Bey P. Conformity index: a review. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64:333–342. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leunens G, Menten J, Weltens C, Verstraete J, Schueren E. Quality assessment of medical decision making in radiation oncology: variability in target volume delineation for brain tumours. Radiother Oncol. 1993;29:169–175. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(93)90243-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeanneret-Sozzi W, Moeckli R, Valley JF, Zouhair A, Ozsahin EM, Mirimanoff RO. The reasons for discrepancies in target volume delineation : a SASRO study on head-and-neck and prostate cancers. Strahlenther Onkol. 2006;182:450–457. doi: 10.1007/s00066-006-1463-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jansen EP, Nijkamp J, Gubanski M, Lind PA, Verheij M. Interobserver variation of clinical target volume delineation in gastric cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;77:1166–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guckenberger M, Pohl F, Baier K, et al. Influence of rectum delineation (rectal volume vs. rectal wall) on IMRT treatment planning of the prostate. Strahlenther Onkol. 2006;182:721–726. doi: 10.1007/s00066-006-1566-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gregoire V, Levendag P, Ang KK, et al. CT-based delineation of lymph node levels and related CTVs in the node-negative neck: DAHANCA, EORTC, GORTEC, NCIC, RTOG consensus guidelines. Radiother Oncol. 2003;69:227–236. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weiss E, Hess CF. The impact of gross tumor volume (GTV) and clinical target volume (CTV) definition on the total accuracy in radiotherapy theoretical aspects and practical experiences. Strahlenther Onkol. 2003;179:21–30. doi: 10.1007/s00066-003-0976-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rasch C, Barillot I, Remeijer P, Touw A, Herk M, Lebesque JV. Definition of the prostate in CT and MRI: a multi-observer study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;43:57–66. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(98)00351-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muijs CT, Schreurs LM, Busz DM, et al. Consequences of additional use of PET information for target volume delineation and radiotherapy dose distribution for esophageal cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2009;93:447–453. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guido A, Fuccio L, Rombi B, et al. Combined 18 F-FDG-PET/CT imaging in radiotherapy target delineation for head-and-neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;73:759–763. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.04.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ford EC, Lavely WC, Frassica DA, et al. Comparison of FDG-PET/CT and CT for delineation of lumpectomy cavity for partial breast irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;71:595–602. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Faria SL, Menard S, Devic S, et al. Impact of FDG-PET/CT on radiotherapy volume delineation in non-small-cell lung cancer and correlation of imaging stage with pathologic findings. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70:1035–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.07.2379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bassi MC, Turri L, Sacchetti G, et al. FDG-PET/CT imaging for staging and target volume delineation in preoperative conformal radiotherapy of rectal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70:1423–1426. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bekelman JE, Wolden S, Lee N. Head-and-neck target delineation among radiation oncology residents after a teaching intervention: a prospective, blinded pilot study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;73:416–423. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tai P, Dyk J, Yu E, Battista J, Stitt L, Coad T. Variability of target volume delineation in cervical esophageal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;42:277–288. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00216-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Castro Pena P, Kirova YM, Campana F, et al. Anatomical, clinical and radiological delineation of target volumes in breast cancer radiotherapy planning: individual variability, questions and answers. Br J Radiol. 2009;82:595–599. doi: 10.1259/bjr/96865511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fuller CD, Nijkamp J, Duppen J, et al: Prospective randomized double-blind pilot study of site-specific consensus atlas implementation for rectal cancer target volume delineation in the cooperative group setting. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2010 (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Szumacher E, Harnett N, Warner S, et al. Effectiveness of educational intervention on the congruence of prostate and rectal contouring as compared with a gold standard in three-dimensional radiotherapy for prostate. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76:379–385. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dalah EZ, Nisbet A, Bradley D. Effect of window level on target volume delineation in treatment planning. Appl Radiat Isotopes. 2010;68:602–604. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Han X, Hoogeman MS, Levendag PC, et al. Atlas-based auto-segmentation of head and neck CT images. Med Image Comput Comput Assist Interv Int Conf Med Image Comput Comput Assist Interv. 2008;11:434–441. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-85990-1_52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sims R, Isambert A, Gregoire V, et al. A pre-clinical assessment of an atlas-based automatic segmentation tool for the head and neck. Radiother Oncol. 2009;93:474–478. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reiner B, Siegel E. The potential for gaming techniques in radiology education and practice. J Am Coll Radiol. 2008;5:110–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ratib O, Valentino DJ, McCoy MJ, Balbona JA, Amato CL, Boots K. Computer-aided design and modeling of workstations and radiology reading rooms for the new millennium. Radiographics. 2000;20:1807–1816. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.20.6.g00nv191807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ng I, Hwang PY, Kumar D, Lee CK, Kockro RA, Sitoh YY. Surgical planning for microsurgical excision of cerebral arterio-venous malformations using virtual reality technology. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2009;151:453–463. doi: 10.1007/s00701-009-0278-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krupinski EA, Berbaum KS. The Medical Image Perception Society update on key issues for image perception research. Radiology. 2009;253:230–233. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2531090237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krupinski EA, Williams MB, Andriole K, et al. Digital radiography image quality: image processing and display. J Am Coll Radiol. 2007;4:389–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krupinski EA, Roehrig H, Dallas W, Fan J. Differential use of image enhancement techniques by experienced and inexperienced observers. J Digit Imaging. 2005;18:311–315. doi: 10.1007/s10278-005-7666-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Manning DJ, Gale A, Krupinski EA. Perception research in medical imaging. Br J Radiol. 2005;78:683–685. doi: 10.1259/bjr/72087985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maes RM. Concerns: choosing a radiology workstation. Radiology. 2008;246:335–336. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2461070734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krupinski EA, Kallergi M. Choosing a radiology workstation: technical and clinical considerations. Radiology. 2007;242:671–682. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2423051403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moise A, Atkins MS, Rohling R. Evaluating different radiology workstation interaction techniques with radiologists and laypersons. J Digit Imaging. 2005;18:116–130. doi: 10.1007/s10278-004-1906-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sherbondy AJ, Holmlund D, Rubin GD, Schraedley PK, Winograd T, Napel S. Alternative input devices for efficient navigation of large CT angiography data sets. Radiology. 2005;234:391–398. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2342032017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weiss DL, Siddiqui KM, Scopelliti J. Radiologist assessment of PACS user interface devices. J Am Coll Radiol. 2006;3:265–273. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2005.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jang SH, Kim WY. Defining a new annotation object for DICOM image: a practical approach. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 2004;28:371–375. doi: 10.1016/j.compmedimag.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dowsett RJ, Galvin JM, Cheng E, et al. Contouring structures for 3-dimensional treatment planning. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1992;22:1083–1088. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(92)90812-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Larsson SN, Stapleton S, Larsson L. A comparison of speed and accuracy of contouring using mouse versus graphics tablet. Clin Oncol. 2007;19:S36–S36. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Anderlind E, Noz ME, Sallnas EL, Lind BK, Maguire GQ., Jr Will haptic feedback speed up medical imaging? An application to radiation treatment planning. Acta Oncol. 2008;47:32–37. doi: 10.1080/02841860701534535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Das IJ, Moskvin V, Johnstone PA. Analysis of treatment planning time among systems and planners for intensity-modulated radiation therapy. J Am Coll Radiol. 2009;6:514–517. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2008.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilson LD, Flynn DF, Haffty BG. Radiation oncology career decision variables for graduating trainees seeking positions in 2003–2004. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;62:519–525. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Full case description/instructions for ROI delineation for each of the anatomic sites (brain, prostate, lung, and head and neck) (PDF 126 kb)