Abstract

With the aid of an efficient, precise, and almost error-free DNA repair system, Deinococcus radiodurans can survive hundreds of double strand breaks inflicted by high doses of irradiation or desiccation. The RecA of Deinococcus radiodurans (DrRecA) plays a central role both in the early phase of repair by an extended synthesis-dependent strand annealing process and in the later more general homologous recombination phase. Both roles likely require DrRecA filament formation on duplex DNA. We have developed single-molecule tethered particle motion (TPM) experiments to study the assembly dynamics of RecA proteins on individual duplex DNA molecules by observing changes in DNA tether length resulting from RecA binding. We demonstrate that DrRecA nucleation on dsDNA is much faster than Escherichia coli (Ec) RecA protein, but the extension is slower. This combination of attributes would tend to increase the number and decrease the length of DrRecA filaments relative to those of EcRecA, a feature that may reflect the requirement to repair hundreds of genomic double strand breaks concurrently in irradiated Deinococcus cells.

Deinococcus radiodurans is a bacterium that can survive extraordinary doses of ionizing radiation1. DNA damage inflicted by ionizing radiation, even when it includes hundreds of double strand breaks, is repaired within a few hours. The extreme radio-resistance appears to be an adaptation to frequent desiccation1-2. Double strand breaks accumulate during dehydration, and radiation-sensitive mutants of Deinococcus radiodurans are also sensitive to desiccation2.

Many hypotheses have been proposed to explain the high efficiency repair, including a ring-like condensed chromosome structure that could restrict fragment DNA diffusion3-5, a high Mn2+ concentration that can scavenge hydroxyl radicals6, an enhanced capacity for replication fork repair7, and the presence of multiple genome copies to facilitate recombinational DNA repair3,8. Mechanisms that reduce protein oxidation have emerged as major contributors to extreme radiation resistance, with possible contributions from novel adaptations of DNA repair systems9-10

Repair of the Deinococcus radiodurans genome after irradiation is strikingly robust, and its mechanism has been studied for decades1,11-15. Zahradka et al.14 proposed that Deinococcus radiodurans uses overlapping homologies as both primer and template for DNA polymerase to elongate single strand overhangs, which enables the fragments to anneal to form double strands with high precision. This early phase of extended synthesis-dependent strand annealing (ESDSA) assembles the fragments into much larger chromosomal segments. In a second phase, the double strand DNA segment is then collected into intact circular chromosomes by homologous recombination mediated by RecA13-14.

The bacterial RecA protein plays an essential role in recombination and repair pathways7,16-19. RecA is found in all bacteria excepting a few endosymbiotic Buchnera species with reduced genomes20. Formation of a RecA nucleoprotein filament is a prerequisite for RecA function, and occurs in two steps16,21-22. The first step is nucleation, in which a RecA oligomer consisting of about 6 RecA subunits binds to DNA. This is then followed by a unidirectional filament extension that proceeds from 5′ to 3′ on single-stranded DNA (ssDNA). For the well-studied E. coli RecA (EcRecA) the nucleation step is normally rate-limiting21. When individual RecA molecules assemble on DNA, the DNA is stretched and underwound to form a nucleoprotein filament with its rigidity and end-to-end length increased23.

RecA promotes recombination in a wide range of physiological contexts, depending on the lifestyle of a given bacterial species1. Reactions can include the repair of stalled replication forks17,24-27, conjugational recombination28, reactions associated with antigenic variation29-30, and genome reconstitution after severe irradiation1. It has been postulated that RecA protein encoded by a given bacterial species will exhibit properties reflecting the dominant DNA repair scenario encountered by that species1,16. With respect to DNA repair, Escherichia coli and Deinococcus radiodurans provide examples of widely divergent lifestyles. E. coli, a gut bacterium, is normally shielded from environmental radiation and its RecA protein (EcRecA) must primarily deal with replication fork repair. Estimates of fork repair frequency vary, but the highest reported rates in a laboratory environment are no more than once per cell per generation7,17,31. D. radiodurans has evolved to survive severe desiccation, an adaptation that also confers resistance to extraordinary levels of ionizing radiation2. Both desiccation and ionizing radiation can leave the cell with hundreds of DNA double strand breaks2, a crisis that the Deinococcus RecA protein (DrRecA) appears to handle efficiently.

RecA protein has proven indispensable for complete chromosome repair in D. radiodurans13,15,32-33. RecA plays a role in both of the two central processes of genome reconstitution in D. radiodurans13-15. The ESDSA phase may be initiated in part by DrRecA binding to the end of double strand DNA to partially unwind the DNA and provide a substrate for an exonuclease like RecJ13,15. In the second phase, RecA-dependent homologous recombination is promoted to link many large DNA fragments produced by ESDSA into an intact circular chromosome13-14. The pathway of strand exchange in D. radiodurans is also started by forming RecA filaments on dsDNA and then targeting homologous ssDNA34. As a result, unlike E. coli19-20, the functional RecA filament for D. radiodurans is most often formed on dsDNA. Therefore, how DrRecA forms nucleoprotein filaments on dsDNA is of substantial interest.

Here, we used a single-molecule approach to examine RecA filament formation. We immobilized one end of dsDNA on a surface and attached the other end to a bead. The approach takes advantage of the properties of RecA, in which binding to dsDNA leads to a 1.5 fold increase in length and an increase in filament stiffness35-36. This in turn leads to a measurable change in the bead’s Brownian motion (BM). The method of tethered particle motion (TPM) has been widely used in single-molecule studies, addressing problems such as the size of a loop formed by a repressor37-38, the folding and unfolding state of G-quadruplex39, and translocation on DNA by polymerases40 and RecBCD helicase/nuclease41. By dissecting how the RecA/dsDNA filament is formed, we hope to shed light on RecA adaptations to different repair contexts.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Single-molecule experiments

Duplex DNA with lengths of 99 bp, 186 bp, 382 bp, 427 bp, and 537 bp were prepared by PCR reaction with a 5′-digoxigenin labeled primer, and a 5′-biotin labeled primer using pBR322 templates. PCR products were gel purified. Slides and streptavidin-labeled beads (200 nm, Bangs labs) were prepared as described previously39,42. Individual dsDNA molecules were tethered on the antidigoxigenin-labeled slide and the other end of the DNA molecules were attached to streptavidin-labeled beads for visualization. Nonspecific interaction between the beads and the slide surface is reduced by using BSA (Calbiochem) as a carrier protein included in all buffers.

For the Brownian motion (BM) dependence of various duplex DNA lengths (Figure 1b), DNA with specific lengths (1 nM molecules), RecA (2 μM), and ATPγS (2 mM, containing <10% ADP, Roche) were incubated for more than 2 hours at room temperature to ensure the DNA molecules were fully coated by RecA molecules. More than 100 tethers were collected (both for dsDNA and RecA-dsDNA) with each tether’s BM values derived by analyzing the standard deviation of 500 constructive frames (30 Hz). The error bars indicate standard deviation.

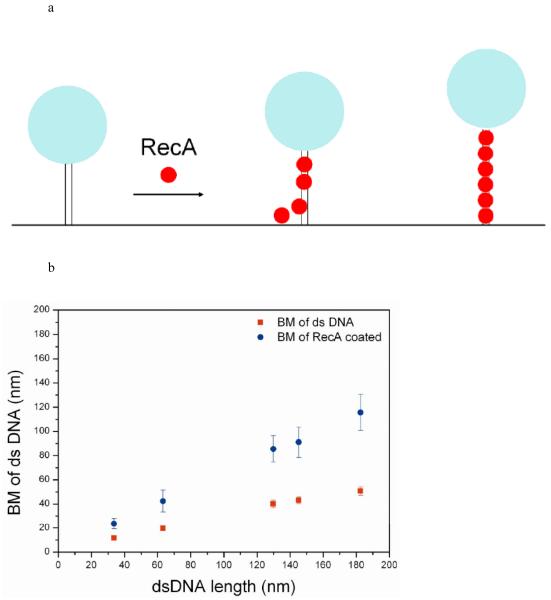

Figure 1.

Observation of RecA assembly along a single duplex DNA molecule using TPM experiments. (a) Changes in bead Brownian motion amplitude reflect the real-time dynamics of RecA nucleation and extension processes. (b) The amplitude of bead’s BM is found to be proportional to bare DNA length (■) within the DNA size studied. The stable extended EcRecA/dsDNA filaments in the presence of the non-hydrolyzable ATP analog, ATPγS (● ), shows a similar linear DNA length dependence, but with a larger slope. Each point contains data from more than 200 tethers and error bars indicate standard deviation. (c) Representative time traces of RecA assembly on a single 382 bp duplex DNA molecule in Buffer B at pH 6.16 and 2 mM ATP. The left column contains traces of EcRecA and the right column for DrRecA. The gray bar designates the time of RecA addition and system re-stabilization (~9-11 s). The recordings were continuous during the buffer change, so the same DNA tethers were monitored throughout the reaction. Time between RecA flow in and Brownian motion change is regarded as nucleation time (the blue line was fit with moving average adjoining 20 points). The phase in which the bead BM showed continuous rise is defined as extension and is fitted with the method described in statistic analysis. We defined the final BM plateau as the maximum BM achieved. BM values of the plateau were collected and the histogram shown beside each time trace. The blue line of the final part indicates the BM of the Gaussian peak.

For real-time RecA nucleation and extension observations, the 382 bp and 186 bp duplex DNA molecules were used for EcRecA and DrRecA respectively unless indicated otherwise. EcRecA was purchased from New England Biolab without further purification, and DrRecA was purified as previously described43. To initiate the reaction, 1000 frames (about 33 s) were recorded to establish the BM of the unbound dsDNA before flowing in a 40 μl mixture of RecA (2 μM) with specific nucleotides (ATP, or ATPγS, 2 mM, Sigma). When ATP was used, an ATP regenerating system (10 units/ml pyruvate kinase and 3 mM phosphoenolpyruvate, Sigma) was included. All reactions were carried out at 22°C. Two experiments indicated were carried out using the same buffer condition as a previous report44 (Buffer A, pH 6.20, 1 mM Mg(OAc)2, 20 mM MES, 20 % sucrose, 30 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5 mM ATP, but with 1 mg/ml BSA added to avoid nonspecific interaction). Except for the experiment with DrRecA at pH 6.46, which contained a different buffer (Buffer C, 20 mM ACES, 5 % glycerol, 10 mM Mg(OAc)2, 3 mM potassium glutamate, 1 mM DTT and 1 mg/ml BSA), all reactions were carried out in Buffer B, containing 25 mM MES, 5 % glycerol, 10 mM Mg(OAc)2, 3 mM potassium glutamate, 1 mM DTT and 1 mg/ml BSA at indicated pH.

For the experiment showing that the BM distribution of EcRecA and DrRecA changes with time (from 0 hour to 30 hours), DrRecA and EcRecA were both studied with 382 bp dsDNA at pH 6.06, in Buffer B but with 4 mM ATP and 0.2 mM ATPγS mixed. More than 100 tethers were collected at each time (0 hr, 1 hr, 5 hr, 10 hr and 30 hr) with each tether’s BM values derived by analyzing the standard deviation of 500 constructive frames (30 Hz).

Statistical analysis

The microscope setup and imaging acquisition were described as previously reported39,42. The image was captured at 33 ms per frame. The effect of thermal drift was excluded by measuring tethering bead positions relative to beads pre-fixed on the slide. To ensure that there is only one DNA molecule attached to each bead, only the beads with symmetrical BM (x/y ratio between 0.9 – 1.1) were analyzed. Therefore, the standard deviation based on Y is the same as that based on X. For time-course measurements, 40 consecutive frames (1.3 seconds) were used to calculate the x standard deviation of the bead distribution, which in turn reflects the amplitude of BM of the DNA tethers. Using more frame numbers does not alter the value. These time-courses were then used to determine the nucleation time, extension rates and maximum BM of RecA assembly along duplex DNA.

For nucleation, the intrinsic uncertainty of naked dsDNA’s BM constrained our resolution. The BM distribution of naked dsDNA for 33 seconds showed that we cannot distinguish BM changes associated with less than 12 or 6 RecA subunits bound for the 382 bp and 186 bp dsDNAs, respectively.

The averaged nucleation times were derived from exponential fitting with Origin 8. Figure 2a, 2b and 2c were the best fitting derived from the formula: y= y0+A*exp (−t/τ), and all exhibited a very small y0 (<1% max value of y). The fitted nucleation times were similar to those fitted by the formula: y= A*exp (−t/τ) and the maximum likelihood estimation (see Supplementary Information S1b for more detail).

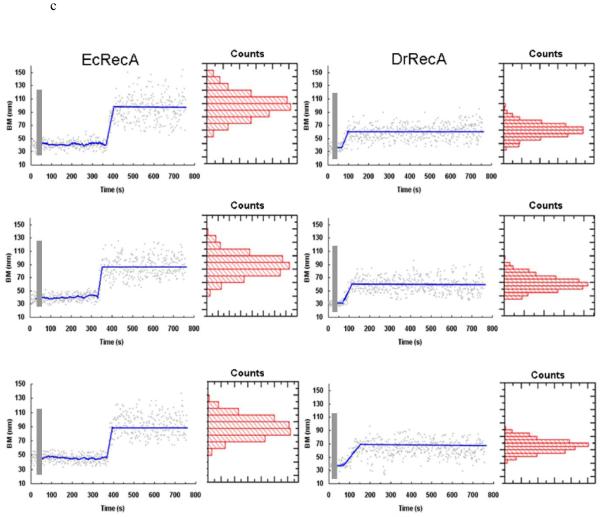

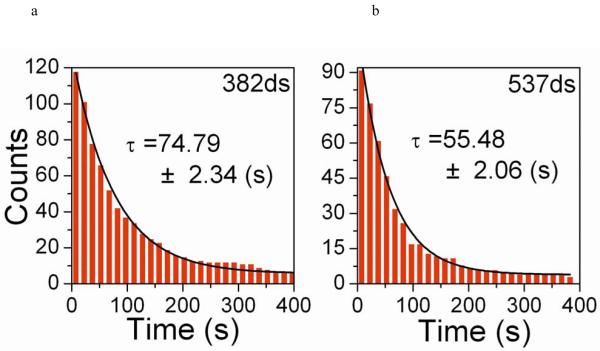

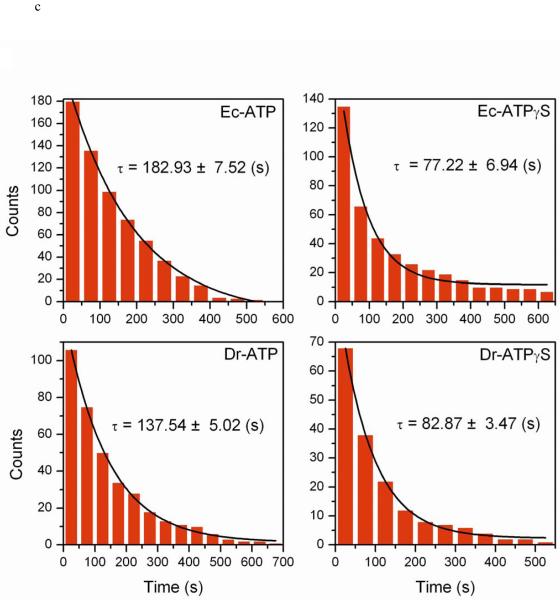

Figure 2.

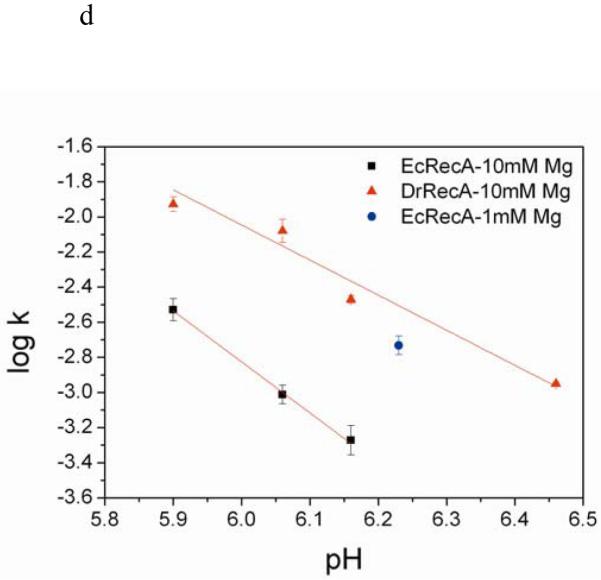

Measured nucleation times using TPM. Nucleation times from individual time courses were binned into a cumulative plot and fitted by a single exponential. (a) EcRecA nucleation with 382 bp dsDNA under the same buffer condition as Galletto et al44 (Buffer A). The fitted time is 74.79 ± 2.34 s, N=118. (b) EcRecA nucleation with 537bp dsDNA under the same buffer condition as Galletto et al (Buffer A). The fitted time is 55.48 ± 2.06 s, N=91. (c) Nucleation time for EcRecA and DrRecA with 382 bp dsDNA in the presence of different nucleotide, ATP and ATPγS. EcRecA was under buffer of pH 6.06 Buffer B and 2 mM ATP (or ATPγS). The nucleation time is 182.92 ± 7.52 s, N=180 with ATP, and 77.22 ± 6.94 s, N=135 with ATPγS. DrRecA was using buffer of pH 6.46 Buffer C and 2 mM ATP (or ATPγS). The nucleation time is 137.54 ± 5.02 s, N=106 with ATP and 82.87 ± 3.47 s, N=68 with ATPγS. (d) Nucleation rate (with unit of bp−1 min−1) of EcRecA (■) and DrRecA (▲ ) under Buffer B using ATP at different pH. The slopes of these two lines are −2.90 and −2.0 for EcRecA and DrRecA respectively. The nucleation rate of EcRecA shown in Figure 2a is also shown in this figure to provide a direct comparison (● ). The data reported were from the analysis of nucleation times of more than 100 tethers, and the error bars reflected the deviation using either a single exponential fitting or the maximum likelihood estimation (see Supplementary Information 1b for more detail).

We defined the time from the moment we flowed RecA in to the moment the BM began to continuously rise, distinguished from the intrinsic uncertainty of the BM derived from naked dsDNA, as the nucleation time. The nucleation times of many tethers were collected in a cumulative histogram and then fitted with a single exponential to derive the average nucleation time. Varying the bin size of the cumulative plot changes the value only within fitting error. Earlier studies established that EcRecA forms a stable nucleus on DNA when ~ 6 RecA subunits are assembled22,44, so our nucleation time also includes a minimal degree of extension as well due to the resolution discussed above. However, if the extension time of 6-12 RecA is taken into account using the previously reported EcRecA extension rates22,44,49-50 (or using our determined rates in this work), it also only changes the nucleation time value within the fitting error.

Considering how much time it takes for RecA to fully coat the nucleoprotein filament, we can directly compare the extension rate of EcRecA with that of DrRecA. Figure S2 showed extension rate distributions calculated from dividing the number of RecA (one third of nucleotides) by the extension duration time. We also used a linear fitting to the continuously increasing BM time-course (the slope) to calculate the extension rates (Figure S2). Both analyses returned a similar distribution within our resolution. We thus report the fitted slopes of the continuous BM rise segments in the reaction traces as extension rates. Conversion factors relating BM to the number of bound RecA subunits for various DNA lengths were obtained by dividing the number of bound RecA subunits at saturation (equal to one third of the base pairs in the duplex DNA molecule) into the BM difference observed between the BM of naked dsDNA and the final (maximum) BM observed in Figure 1b (Figure S3). Since the size of DrRecA is similar to EcRecA and both of them formed similar filaments at the end (see further discussion in Figure 5), this factor was used for both EcRecA and DrRecA.

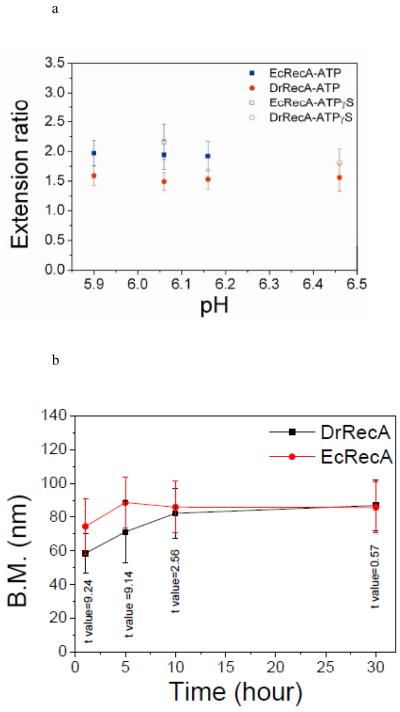

Figure 5.

The maximum amplitude of bead BM upon RecA assembly. (a) The extension ratio provides a direct comparison between different DNA length observations of EcRecA and DrRecA: ■, EcRecA with ATP.●, DrRecA with ATP. □, EcRecA with ATPγS. ○, DrRecA with ATPγS. Error bars indicate standard deviation. (b) Extended time observation of BM of EcRecA and DrRecA filaments. Experiments of DrRecA and EcRecA were both done with the 382 bp dsDNA with Buffer B at pH 6.06 with 4 mM ATP and 0.2 mM ATPγS. More than 100 tethers were collected at each time (0 hr, 1 hr, 5 hr, 10 hr and 30 hr) to analyze their BM. T values are labeled at indicated time.

Slopes defined could vary, depending on the exact starting and end point of the fitting region, but all rates showed variation no larger than 0.31 RecA/s (after unit conversion), which is within the bin size (0.5 RecA/s) of the rate distribution.

For the maximum BM achieved, the plateau BM values of every single trace were fitted with a Gaussian and we regarded the peak as the maximum BM achieved for each tether.

Electron microscopy

A modified Alcian method was used to visualize RecA filaments. Activated grids were prepared as previously described45. EcRecA or DrRecA protein (0.8 μM) was preincubated with 12 μM (in nucleotides) Nb.BsmI nicked circular double-stranded M13mp18 DNA in pH 6.06, Buffer B for 10 minutes at room temperature. An ATP regeneration system of 10 units/ml creatine phosphokinase and 12 mM phosphocreatine were also included in the incubation. ATP was added to 0.8 mM and the reaction was incubated for another 15 min. ATPγS was then added to 0.8 mM to stabilize the filaments, followed by 5 min incubation.

The reaction mixture described above was diluted two-fold with 200 mM ammonium acetate, 10 mM MES pH 6.06, and 10% w/v glycerol and adsorbed to an activated carbon grid (Alcian grid) for 3 min. The grid was then touched to a drop of the above buffer, followed by floating on a second drop of the buffer for 1 min. The sample was then stained by touching to a drop of 5% uranyl acetate followed by floating on a fresh drop of 5% uranyl acetate solution for 30 s. Finally, the grid was washed by touching to a drop of double distilled water followed by successive immersion in two 10-ml beakers of double distilled water. After the sample was dried, it was rotary-shadowed with platinum. This protocol is designed for visualization of complete reaction mixtures, and no attempt was made to remove unreacted material. Although this approach should yield results that provide insight into reaction components, it does lead to samples with a high background of unreacted proteins.

Imaging and photography were carried out with a TECNAI G2 12 Twin Electron Microscope (FEI Co.) equipped with a GATAN 890 CCD camera. Digital images of the nucleoprotein filaments were taken at 15,000 X magnification. Filament fragment lengths (protein coated regions of DNA) were measured using the MetaMorph analysis software. Circular DNA molecules that contained protein were measured and analyzed, a total of 28 from EcRecA and 27 from DrRecA samples. Each filament fragment was measured 3 times, and the average length was calculated. The 500 nm scale bar was used as a standard to calculate the number of pixels per nm. Each nucleoprotein fragment length, originally measured by MetaMorph in pixels, was thus converted to nm.

RESULTS

RecA assembly dynamics studied by TPM experiments

When RecA recombinases form nucleoprotein filaments on duplex DNA, the DNA within the filaments is underwound and the end-to-end distance of DNA increases approximately 50%36,46. In addition to increasing the DNA length, binding of RecA also stiffens DNA, resulting in a more rigid DNA-RecA complex23. The persistence length is increased from the ~50 nm typical of duplex DNA to the 464 nm measured for RecA nucleoprotein filaments47. We have devised a tethered particle motion (TPM) approach for the examination of RecA filament formation at the single-molecule level.

In the TPM measurement, individual duplex DNA molecules were immobilized on the glass surface through a digoxigenin/anti-digoxigenin linkage. The distal end of the DNA was linked to a streptavidin-labeled bead visible by differential interference contrast (DIC) light microscopy (Figure 1a). In solution, the segment of DNA between the bead and the surface attachment acts as a flexible tether that constrains the bead BM to a small region above the glass surface. Changes in the length and rigidity of the DNA tether results in a change in the spatial extent of bead BM. This change of bead motion can be measured to nanometer precision using digital image processing techniques that determine the standard deviation of the bead centroid position in light microscope recordings39,41-42,48. Figure 1b shows that the bead BM before and after EcRecA coating is distinguishable for a series of lengths of dsDNA.

Typical time-courses of EcRecA assembly on a 382 bp duplex DNA are shown in the left column of Figure 1c. After a 1,000-frames (33 s) recording of the BM of dsDNA tethers, a mixture of EcRecA and ATP (or ATPγS) was introduced in the reaction chamber, as shown in the gray bar, with a deadtime of about 10 seconds due to focus re-stabilization. The same DNA tether was recorded to monitor the RecA assembly process. In Figure 1c, the DNA tether length stayed constant until reaching a point where an obvious, continuous increase in BM was observed. The DNA tether length then stayed constant at the higher BM amplitude, consistent with the BM value we measured for fully coated EcRecA-dsDNA filaments in Figure 1b.

We define the dwell time between the RecA introduction and the time where apparent BM change occurred as the nucleation time, the continuous BM increase region as the DNA extension caused by RecA assembly, and the high BM value where DNA tether length stayed constant as the maximum BM achieved. For the study described below, experiments and analysis were first done with EcRecA, and results were compared with previous reports to validate the TPM experiments. We then applied this method to study DrRecA filament formation. Finally, we confirmed these results with electron microscopic studies.

DrRecA nucleates faster than EcRecA on dsDNA

The time from the moment RecA was added to the reaction (flowed in) to the moment a continuous increase in BM was observed that could be distinguished from the intrinsic uncertainty of naked dsDNA was defined as the nucleation time. The nucleation times of many tethers were collected in a cumulative histogram and then fitted with a single exponential to derive the average nucleation time (Figure 2).

We first did a series of experiments to verify that TPM methods are capable of monitoring the nucleation time of RecA. First, longer dsDNA molecules provide more sites for nucleation and would thus reduce the nucleation time. EcRecA assembly was studied using 382 bp (Figure 2a) and 537 bp (Figure 2b) dsDNAs under the same buffer condition. A shorter nucleation time was indeed observed for longer DNA but with a similar nucleation rate (nucleation events per bp of DNA per minute). Second, previous reports documented that EcRecA nucleates faster in the presence of ATPγS than in the presence of ATP 44,50-51. The faster nucleation is thought to result from the higher affinity of RecA protein for ATPγS44. Using the 382 bp dsDNA, we determined that the nucleation time is indeed shorter in the presence of ATPγS than in the presence of ATP (Figure 2c). Third, we also examined the pH dependence on the nucleation rate of EcRecA proteins (Figure2d, ■). EcRecA nucleation on fully dsDNA became slower at higher pHs (> 6.5)21,51, with a slope of −3.03. This is consistent with the studies done by Pugh and Cox21, which showed that EcRecA takes up three protons during nucleation21. Finally, the nucleation rate at 1 mM Mg2+ (Figure 2d, ● ) was faster than that at 10 mM Mg2+ (■). This result is again consistent with the notion that RecA binding to dsDNA is inversely proportional to the DNA stability53. Applying force by stretching DNA54, increasing temperature53, or decreasing cation concentration53 weakens the thermal stability of dsDNA, and thus facilitates RecA binding and augments the RecA nucleation rate.

EcRecA nucleation rates determined using the 382 bp dsDNA (Figure 2a) have buffer conditions similar to those used in an earlier report using much longer DNAs44, but the nucleation rate was somewhat higher than those previously reported44,50. Knowing that TPM experiments accurately describe RecA assembly behaviors as listed above, the current reported nucleation rates actually reflect the improved sensitivity and resolution in the TPM experimental design. The spatial resolution of earlier studies is in the range of hundreds of nanometers, because of the long DNA molecules used (lambda DNA, 48 Kbp) and the diffraction limit posted by fluorescence imaging44,50. Moreover, as observed by Hilario et al., small amounts of detached RecA during repetitive translation of the DNA filament between reaction channel and observation channel may also exert a small delay on nucleation time55. Using much shorter DNAs (hundreds of basepairs), TPM experiments offer improved sensitivity and higher resolution, so the RecA nucleation time can be determined more accurately.

We next examined the nucleation process of DrRecA on dsDNA. Experiments with the DrRecA using the 382 bp dsDNA indicated that nucleation was too fast to accurately determine the nucleation time at lower pH, mainly due to the 10 second dead time for instrument re-stabilization after introducing RecA. Since the nucleation time depends on the number of available nucleation sites (the DNA length) and pH, the work with DrRecA thus required a higher pH or a shorter DNA to slow down the nucleation process. Experiments were first done at a pH of 6.46. We then extended these measurements to lower pHs by using shorter DNA molecules. As with the EcRecA44,50-51, the DrRecA also nucleates faster in the presence of ATPγS than in the presence of ATP (Figure 2c). The inverse DNA length dependence of nucleation times also holds for DrRecA (Figure S1a). DrRecA nucleation rates were determined with a shorter DNA of 186 bp duplex at the same pHs used for the EcRecA. All nucleation rates are reported in terms of nucleation events per basepair per minute (bp−1min−1) for direct comparison between EcRecA and DrRecA (Table 1). DrRecA exhibited a much faster nucleation rate than EcRecA at the various pHs we examined. Moreover, the pH-dependence studies of DrRecA imply that DrRecA takes up about two protons during nucleation (Figure 2d, ▲ , slope of −1.93). The difference of one proton taken up during nucleation between EcRecA and DrRecA (3 for EcRecA and 2 for DrRecA) increases the difference between nucleation rates even more at higher pHs. Since the DNA we used is short (hundreds of basepairs), it was not feasible to measure the slow nucleation rates at higher pHs within the experimental time scale. Thus, real-time TPM detection is only carried out at lower pHs. Strand exchange is promoted over the pH range of 6.0-8.452, and results here permit an estimation of nucleation rates at higher pH (the condition where strand exchange happens with optimal efficiency) by extrapolation of the measurements in Figure 2d.

Table 1.

Direct comparison between DrRecA and EcRecA at a series of different pHs. All rates are shown with the unit of per base pair per minute for direct comparison.

| Nucleation rate under ATP (bp−1min−1) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 5.90 | 6.06 | 6.16 | 6.46 |

| DrRecA | 1.30×10−2 | 9.24×10−3 | 3.51×10−3 | 1.14×10−3 |

| EcRecA | 2.68×10−3 | 8.59×10−4 | 4.41×10−4 | |

DrRecA extends its filaments more slowly than EcRecA

The continuous BM increase in Figure 1c represents the extension process of RecA assembly. We calculated the extension rates based on two different methods: the dwell time required for full filament assembly and the linear fitting of the continuously increasing BM time-course (the slope), as shown in Supplemental Figure S2. Both analyses returned with a similar extension rate distribution within our experimental resolution. In addition, the extension rates determined here for EcRecA are consistent with what has been previously reported44. We thus used the slope of the linear phase corresponding to the continuous BM rise to define extension rates for purposes of this study. Even though we cannot completely exclude potential error associated with the slope fitting, particularly the possibility that the relation between RecA binding and the observed BM is not perfectly linear, the slopes of all BM increases were linear within the experimental limits of these observations, and any nonlinearity is thus small and constrained by those limits..

Slopes defined could vary, depending on the exact starting and end point of the fitting region, but all rates showed variation no larger than 0.31 RecA/s (after unit conversion), which is within the bin size (0.5 RecA/s) of rate distribution. There are a few factors that might lead to an overestimation. We cannot entirely exclude the possibility of multiple nucleation events occurring during the extension process. However, the typical nucleation times (e.g., see Figure 1c) were long enough for EcRecA that multiple nucleations are considered unlikely, except in cases where one nucleation event in the middle of the DNA stimulates a second event at the same site. The slow nucleation of EcRecA onto dsDNA was previously shown to be tightly linked to DNA underwinding21,51, such that any structural perturbation or feature that rendered the DNA easier to unwind also facilitated nucleation. For example, nucleation events on a linear duplex DNA are thus most likely to occur at DNA ends where the strands are more readily separated and at regions of high A/T content in the sequence. In our experiments, DNA ends are attached to a bead or the slide, thus the potential for perturbation is somewhat different. Once a filament segment has been nucleated at a position in the DNA interior, the DNA within the filament is underwound, and winding of the DNA immediately adjacent to the filament should be affected. Thus, the nucleating end of one filament may represent an enhanced nucleation site for another nucleation event, adjacent to the first filament and sometimes oriented in the opposite direction. This second event would thus complete the binding of the DNA. Two nearly simultaneous nucleation events would give rise to a doubling of the observed slope of BM increase, and lead to an overestimation of the normal rate by a factor of two. On the other hand, if there were pauses between two separate extension phases on one DNA molecule that could not be distinguished within our experimental resolution, these pauses could lead to a small underestimation of the rate.

Although with limitations above, extension rates of EcRecA derived from our experiments were all within the range of rates that have been reported44,49-50. Varying the buffer conditions does not significantly alter the extension rates (Figure S4), as we expected that extension is relatively independent of the salt condition and pH value based on earlier published results.

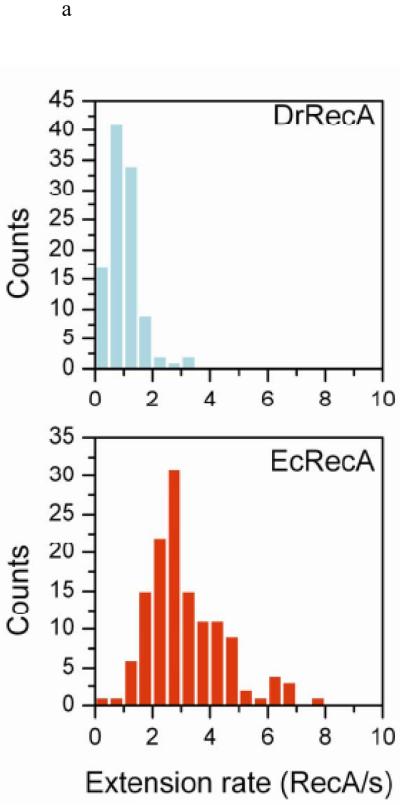

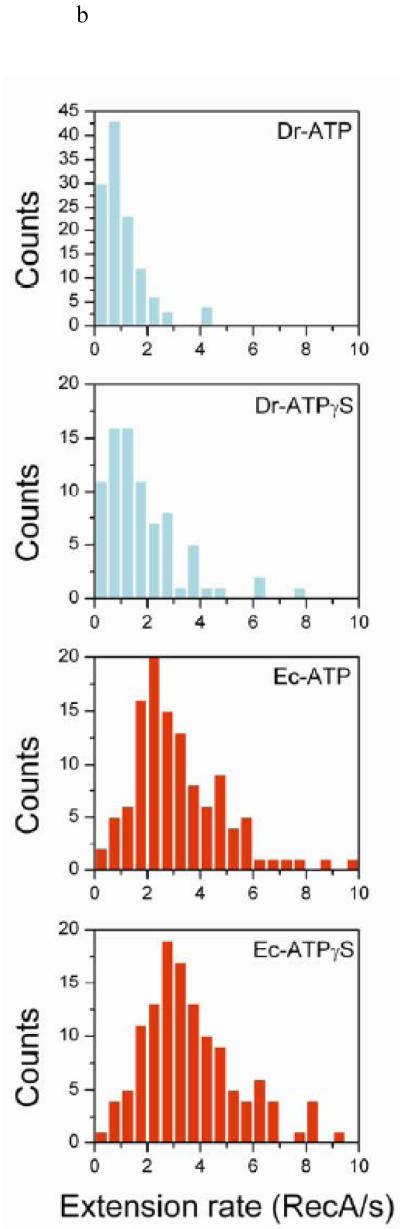

Extension rates were next examined for DrRecA. The extension rate distribution also shows negligible variation at different pHs (Figure S5), consistent with what is shown for EcRecA. To exclude any influence of DNA length and pH, we directly compared extension rates between EcRecA and DrRecA under the same pH (pH 6.16, with ATP) with the same length of dsDNA (382 bp). Figure 3a shows that DrRecA extends more slowly than EcRecA. Experiments were also done with ATPγS to test if the extension process was affected by ATP hydrolysis. Since DrRecA nucleates faster with ATPγS (Figure 2c), an accurate measurement must be done at higher pH. However, EcRecA nucleates too slowly for real-time observation at the same high pH condition for direct comparison. Therefore, considering that the extension rate distribution is independent of pH, we measured the rate distributions for filament extension with ATP or ATPγS at pH 6.06 for EcRecA and 6.46 for DrRecA. In Figure 3b, we show that the extension rate distributions changed very little for ATP and ATPγS, and EcRecA has faster extension rates than DrRecA in both nucleotide states. This confirms that DrRecA exhibits a slower extension rate than EcRecA and this rate is independent of ATP hydrolysis.

Figure 3.

The extension rates observation. (a) Rate distribution of DrRecA and EcRecA with 382 bp dsDNA under pH 6.16 Buffer B and 2mM ATP (N=106 for DrRecA, N=135 for EcRecA). (b) Rate distribution of DrRecA and EcRecA with ATP and ATPγS using 382 bp dsDNA. EcRecA was studied in Buffer B at pH 6.06 and with 2 mM ATP (or ATPγS), and DrRecA was studied in Buffer C at pH 6.46 and 2 mM ATP (or ATPγS).

DrRecA forms a filament with one or more gaps

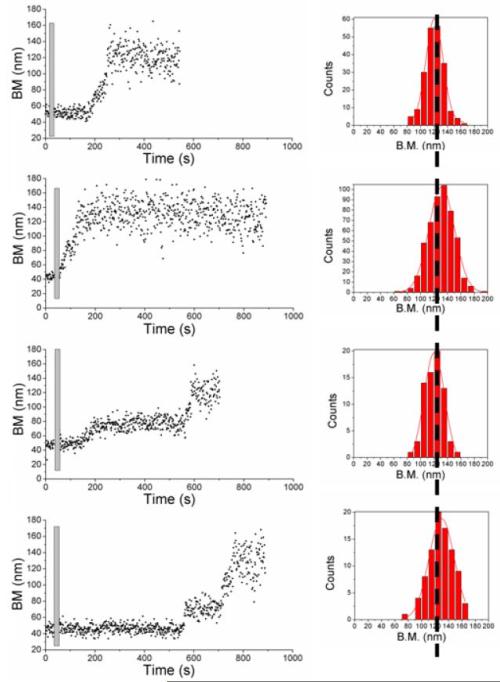

RecA nucleoprotein filament formation starts when RecA nucleates on any site along dsDNA, followed by extension. If RecA nucleates in the middle of dsDNA but another nucleation event does not happen until the first filament extends unidirectionally along one strand to one or the other end, then a two step extension might be observed. A small number of apparent two-step-extension events were observed in our experiments, with the frequency of such events increasing for longer dsDNA molecules. Even with the longest DNA used in our experiment, the fraction of two step events was small (about 10 %). A few exemplary time traces with EcRecA and ATPγS assembled on a 537 bp dsDNA are presented in Figure 4. Even though the filaments can form in more than one way, the maximum BM achieved in Figure 4 are similar for different tethers under the same experimental conditions.

Figure 4.

The final BM achieved is a characteristic factor. Four traces of EcRecA with 537 bp dsDNA in Buffer B at pH 6.16, and with 2 mM ATPγS were shown. Histograms in the right column are the final BM achieved for each experiment. The results from panels (a) to (d) show that no matter how the RecA filament forms, the final BM achieved did not vary (histograms on the right column).

Therefore, the maximum BM achieved can thus be regarded as a characteristic of RecA nucleoprotein filaments. However, due to the different lengths of dsDNA used in this work, we cannot directly compare the maximum BM for different DNAs. Instead, the ratio of the final and initial BM offers a direct comparison of various filaments, such as EcRecA and DrRecA. Figure 5a shows the extension ratio of EcRecA (■) and DrRecA (● ) at different pHs. Even though the extension ratio changes slightly at different pHs, DrRecA always showed a slightly lower extension ratio than that of EcRecA. To determine if this resulted from the higher rates of ATP hydrolysis of DrRecA, experiments in the presence of ATPγS were done (Figure 5a, ○ and □ for ATPγS). Figure 5a showed that even with ATPγS, EcRecA still has a higher extension ratio than DrRecA, suggesting that this effect is not mainly caused by ATP hydrolysis. The slightly larger extension ratio seen with ATPγS than that with ATP might be due to a less extended RecA-dsDNA filament in the presence of ATP, consistent with previous studies56.

The smaller maximum BM observed for DrRecA may have two possible causes. First, DrRecA may form a somewhat more compact filament than EcRecA, which also results in a smaller observed BM. Second, a filament with one or more gaps that break up its continuity could also lead to a smaller BM. Considering the faster nucleation but slower extension rates of DrRecA, a filament with multiple nucleation events to form short RecA patches along DNA is possible. Since one RecA occupies three nucleotides36, there must be gap between two RecA patches and the gap size depends on the size of extension oligomer. If DrRecA extended by the addition of monomeric subunits, then the maximum gap size is two basepairs, which is too small for us to detect. Therefore, if the smaller BM observed for DrRecA was caused by many gaps within the RecA filament, then it also suggested that DrRecA extended by addition of multimeric DrRecA units. Electron microscopic images of DrRecA published to date have not produced evidence of a more compact filament than EcRecA43. A fast nucleation followed by slow extension, especially extension by means of the addition of multimers, does produce a less continuous filament for Rad5157. All of these observations suggest that the somewhat lower BM reflects the formation of DrRecA filaments with one or more gaps of significant size.

If the lower BM simply reflects a more compact filament, then the length of the filament and the observed BM should not change with time. However, if filaments typically include one or more gaps, a slow redistribution of RecA subunits with time could generate a more continuous filament with a correspondingly slow increase in BM. We followed the BM values of both EcRecA and DrRecA filaments using 382 bp DNA substrates at various time points that are long enough for RecA dissociation and binding to occur. The reaction was done in a mixture of ATP and ATPγS, with ATP concentration 20 times higher than ATPγS. The high concentration of ATP enabled us to provide enough time for RecA binding and limited dissociation. The accompanying low concentration of ATPγS avoided RecA disassembly after long time observation. Figure 5b shows the BM distribution of EcRecA and DrRecA assembled on the 382 bp dsDNA at different times. The BM for the DrRecA filaments increased slowly, and exhibited essentially the same BM distribution as EcRecA after 30 hours. A t-test was done as a confirmation that the BM distribution of EcRecA and DrRecA were different at first but the same at the end of observation. This slow increase in BM suggests that DrRecA filaments might contain gaps initially, and DrRecA redistribution allows gap removal and the formation of continuous filaments at later times.

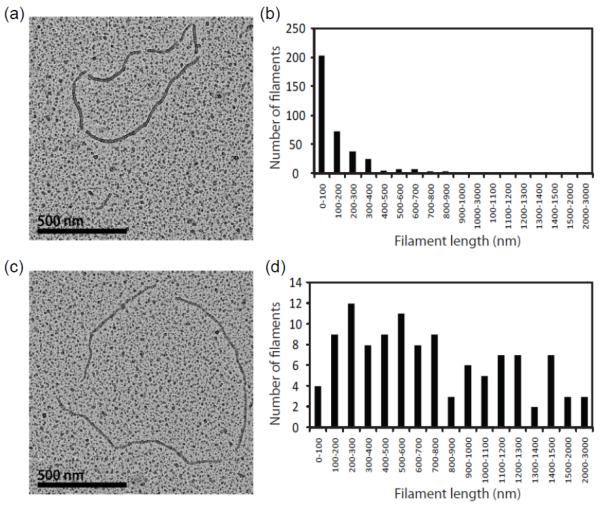

We also used electron microscopy to examine nucleation and extension by DrRecA or EcRecA on dsDNA under very similar reaction conditions. The faster nucleation and slower extension of DrRecA protein filaments should result in larger numbers of shorter filaments; the filaments formed by EcRecA should be longer because of its slow nucleation and fast extension. This would be especially evident under conditions in which RecA protein was present in sub-saturating amounts relative to available DNA binding sites. We also expected a higher number of discontinuities (gaps) in the DrRecA protein samples than the EcRecA samples. The protein concentration used in these experiments was enough to bind approximately 40% of the available DNA binding sites in the relaxed circular dsDNA. Representative DrRecA and EcRecA nucleoprotein filaments, observed by EM, are shown in Figure 6a and 6c, respectively. Among the 27 DrRecA-dsDNA molecules analyzed, we counted a total of 368 nucleoprotein fragments and on average 14 gaps per DNA molecule. The DrRecA fragments were mostly short (mean of 151.6 nm), with only one filament segment measuring more than 1000 nm (Figure 6b). Among the 28 EcRecA-dsDNA molecules analyzed, approximately 4 gaps were found in each molecule. This resulted in 113 fragments that were relatively long, varying in size from 31.64 nm to 2,599 nm (Figure 6d). The average EcRecA filament segment length was 745.6 nm, almost five times longer than the average DrRecA filament segment.

Figure 6.

DrRecA formed more gaps and much shorter nucleoprotein filaments than EcRecA as visualized by electron microscopy. Reactions were carried out as described under Materials and Methods. (A) A representative circular dsDNA bound by DrRecA containing 6 gaps and 6 nucleoprotein filaments. (B) Quantification of 27 circular dsDNA molecules bound by DrRecA shows that DrRecA forms a total of 368 short filaments within that population, most of which are very short. (C) A representative circular dsDNA bound by EcRecA containing 3 gaps and 3 nucleoprotein filaments. (D) Quantification of 28 circular dsDNA molecule bound by EcRecA shows that EcRecA forms 113 nucleoprotein filaments that vary from short to very long, up to 2599 nm.

DISCUSSION

We have examined the process of RecA binding to dsDNA with a single-molecule approach, observing the Brownian motion of a bead connected to one tethered dsDNA. As seen in past studies, the nucleation rate limits the overall rate of RecA filament formation53,58. Our work with the EcRecA protein demonstrates that the TPM method produces the same dependences of nucleation and extension rates on pH as previously documented. The absolute rates of nucleation we observed are somewhat faster than previously reported, likely due to the greater resolution of the present method. Most importantly, we demonstrate that the DrRecA protein exhibits important differences from the EcRecA in binding to dsDNA, nucleating faster, extending slower and resulting in a less continuous RecA filament than the typical RecA protein, E.coli RecA. The overall conclusions derived from the new TPM method were supported by the results of electron microscopy experiments done in parallel.

The RecA proteins derived from different bacterial species tend to exhibit little obvious variation, forming similar filaments on DNA and carrying out a similar set of reactions1,16. Adaptations to different cellular DNA repair contexts are likely to be found in the details, particularly the details of filament formation, kinetics, and stability. The parameters we define here for the formation of DrRecA filaments on DNA may reveal some information about how the RecA protein of Deinococcus radiodurans operates in an environment requiring the repair of many double strand breaks at one time. Fast nucleation and slow extension make sense in this context, potentially leading to many shorter filaments (rather than a few long ones) and a more productive deployment of the protein for repair.

As with any experimental approach, including single-molecule approaches, our method has some limitations. The nucleation rate may be slightly faster than we report, since we cannot detect fewer than 12 or 6 bound RecA subunits depending on DNA substrate and conditions. We also cannot entirely exclude the occurrence of multiple nucleation events that would lead to a higher apparent extension rate. However, the error in this case should be no more than a factor of 2. The limitations are the same for any RecA protein that might be examined, so that comparisons still provide useful information, especially when qualitatively discussing the properties of two different RecA proteins.

The apparently fast nucleation observed for DrRecA must be embedded in its structure. We note that the last few amino acids of C terminal domain of EcRecA show a high density of negative charges16,18,45. A faster binding for RecA to dsDNA can be facilitated by removing these negatively charged residues or stabilizing these negatively charged residues with protons at low pH59-60. The C terminal domain of DrRecA possesses fewer negative charges61, a structure that might contribute to the more rapid nucleation. Moreover, the nucleation rate changes less as a function of pH. With our short dsDNA, we cannot directly provide the nucleation rate at high pHs. However, by extrapolating the rate from our experiments, we can suggest that even under high pH (7.5-8.5), that nucleation would occur rapidly (in the several seconds to a few minutes range) for DrRecA nucleating on dsDNA fragments generated by radiation (20-30 kb)13-14 to form a filament. The results are also consistent with the lack of EcRecA binding seen at high pH21,51, which facilitates the strand exchange process by not blocking dsDNA with bound RecA. In contrast, DrRecA can easily bind to dsDNA even at high pH, as noted previously34. We speculate that the slower filament extension reaction may reflect the presence of 12 extra residues in the N-terminal domain of DrRecA relative to EcRecA61. The N-terminal domain packs against part of the core of the adjacent RecA subunit in a RecA filament16, and the N-terminal domain must undergo a change of conformation or orientation in the process of filament assembly that may affect extension rates.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Mr. Wayne Mah and Axel Brilot for initial pilot work.

This work is supported by National Science Council (NSC) of Taiwan to HWL, and by the United States National Institutes of Health (NIH grant GM32335) to MMC.

Glossary

- Ec

Escherichia coli

- Dr

Deinococcus radiodurans

- BM

Brownian motion

- TPM

tethered particle motion

- ssDNA

single-stranded DNA

- dsDNA

double-stranded DNA

Footnotes

Supporting Information

This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cox MM, Battista JR. Deinococcus radiodurans - The consummate survivor. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2005;3:882–892. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mattimore V, Battista JR. Radioresistance of Deinococcus radiodurans: Functions necessary to survive ionizing radiation are also necessary to survive prolonged desiccation. J. Bacteriol. 1996;178:633–637. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.3.633-637.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levin-Zaidman S, Englander J, Shimoni E, Sharma AK, Minton KW, Minsky A. Ringlike structure of the Deinococcus radiodurans genome: A key to radioresistance? Science. 2003;299:254–256. doi: 10.1126/science.1077865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Englander J, Klein E, Brumfeld V, Sharma AK, Doherty AJ, Minsky A. DNA toroids: Framework for DNA repair in Deinococcus radiodurans and in germinating bacterial spores. J. Bacteriol. 2004;186:5973–5977. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.18.5973-5977.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zimmerman JM, Battista JR. A ring-like nucleoid is not necessary for radioresistance in the Deinococcaceae. Bmc Microbiol. 2005;5:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-5-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daly MJ, Gaidamakova EK, Matrosova VY, Zhai M, Venkateswaran A, Hess M, Omelchenko MV, Kostandarithes HM, Makarova KS, Wackett LP, Fredrickson JK, Ghosal D. Accumulation of Mn(II) in, Deinococcus radiodurans facilitates gamma-radiation resistance. Science. 2004;306:1025–1028. doi: 10.1126/science.1103185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cox MM. Recombinational DNA repair of damaged replication forks in Escherichia coli: Questions. Ann. Rev. Genet. 2001;35:53–82. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.35.102401.090016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Minton KW. Repair of ionizing-radiation damage in the radiation resistant bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans. Mutat. Res.DNA Repair. 1996;363:1–7. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(95)00014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slade D, Radman M. Oxidative Stress Resistance in Deinococcus radiodurans. Microbio. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2011;75:133–191. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00015-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daly MJ, Gaidamakova EK, Matrosova VY, Kiang JG, Fukumoto R, Lee DY, Wehr NB, Viteri GA, Berlett BS, Levine RL. Small-Molecule Antioxidant Proteome-Shields in Deinococcus radiodurans. Plos One. 2010;5:e12570. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Battista JR, Earl AM, Park MJ. Why is Deinococcus radiodurans so resistant to ionizing radiation? Trends Microbiol. 1999;7:362–365. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(99)01566-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daly MJ, Minton KW. An alternative pathway of recombination of chromosomal fragments precedes recA-dependent recombination in the radioresistant bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans. J. Bacteriol. 1996;178:4461–4471. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.15.4461-4471.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slade D, Lindner AB, Paul G, Radman M. Recombination and Replication in DNA Repair of Heavily Irradiated Deinococcus radiodurans. Cell. 2009;136:1044–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zahradka K, Slade D, Bailone A, Sommer S, Averbeck D, Patranovic M, Lindner AB, Radman M. Reassembly of shattered chromosomes in Deinococcus radiodurans. Nature. 2006;443:569–573. doi: 10.1038/nature05160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bentchikou E, Servant P, Coste G, Sommer S. A major role of the RecFOR pathway in DNA double-strand-break repair through ESDSA in Deinococcus radiodurans. Plos Genet. 2010;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000774. 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lusetti SL, Cox MM. The bacterial REcA protein and the recombinational DNA repair of stalled replication forks. Ann. Rev. Biochem. 2002;71:71–100. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.083101.133940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cox MM. The nonmutagenic repair of broken replication forks via recombination. Mutat. Res. 2002;510:107–120. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(02)00256-7. 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cox MM. Regulation of bacterial RecA protein function. Crit. Rev. in Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2007;42:41–63. doi: 10.1080/10409230701260258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cox MM. Motoring along with the bacterial RecA protein. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:127–138. doi: 10.1038/nrm2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cox MM. The bacterial RecA protein as a motor protein. Ann. Rev. Microbiol. 2003;57:551–577. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pugh BF, Cox MM. General mechanism for RecA protein-binding to duplex DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 1988;203:479–493. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joo C, Mckinney SA, Nakamura M, Rasnik I, Myong S, Ha T. Real-time observation of RecA filament dynamics with single monomer resolution. Cell. 2006;126:515–527. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hegner M, Smith SB, Bustamante C. Polymerization and mechanical properties of single RecA-DNA filaments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:10109–10114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cox MM. Recombinational DNA repair in bacteria and the RecA protein. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 2000;63:311–366. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60726-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Michel B. Replication fork arrest and DNA recombination. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2000;25:173–178. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01560-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Michel B, Grompone G, Flores MJ, Bidnenko V. Multiple pathways process stalled replication forks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:12783–12788. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401586101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Michel B, Boubakri H, Baharoglu Z, LeMasson M, Lestini R. Recombination proteins and rescue of arrested replication forks. DNA Repair. 2007;6:967–980. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clark AJ, Sandler SJ. Homologous genetic-recombination- the pieces begin to fall into place. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 1994;20:125–142. doi: 10.3109/10408419409113552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koomey M, Gotschlich EC, Robbins K, Bergstrom S, Swanson J. Effects of RecA mutations on pilus antigenic variation and phase-transitions in Neisseria-Gonorrhoeae. Genetics. 1987;117:391–398. doi: 10.1093/genetics/117.3.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sechman EV, Kline KA, Seifert HS. Loss of both Holliday junction processing pathways is synthetically lethal in the presence of gonococcal pilin antigenic variation. Mol. Microbiol. 2006;61:185–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05213.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cox MM. A broadening view of recombinational DNA repair in bacteria. Genes to Cells. 1998;3:65–78. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1998.00175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carroll JD, Daly MJ, Minton KW. Expression of recA in Deinococcus radiodurans. J. Bacteriol. 1996;178:130–135. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.1.130-135.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Daly MJ, Ling OY, Fuchs P, Minton KW. In-vivo damage and recA-dependent repair of plasmid and chromosomal DNA in the radiaton-resistant bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans. J. Bacteriol. 1994;176:3508–3517. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.12.3508-3517.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim JI, Cox MM. The RecA proteins of Deinococcus radiodurans and Escherichia coli promote DNA strand exchange via inverse pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:7917–7921. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122218499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Story RM, Weber IT, Steitz TA. The structure of the Escherichia coli RecA protein monomer and polymer. Nature. 1992;355:318–325. doi: 10.1038/355318a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen ZC, Yang HJ, Pavletich NP. Mechanism of homologous recombination from the RecA-ssDNA/dsDNA structures. Nature. 2008;453:483–489. doi: 10.1038/nature06971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wong OK, Guthold M, Erie D, Gelles J. Multiple conformations of lactose repressor-DNA looped complexes revealed by single molecule techniques. Faseb J. 2000;14:766. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wong OK, Guthold M, Erie DA, Gelles J. Interconvertible lac repressor-DNA loops revealed by single-molecule experiments. Plos Biol. 2008;6:2028–2042. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chu JF, Chang TC, Li HW. Single-molecule TPM studies on the conversion of human telomeric DNA. Biophys. J. 2010;98:1608–1616. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.12.4328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schafer DA, Gelles J, Sheetz MP, Landick R. Transcription by single molecules of RNA polymerase observed by light microscopy. Nature. 1991;352:444–448. doi: 10.1038/352444a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dohoney KM, Gelles J. chi-Sequence recognition and DNA translocation by single RecBCD helicase/nuclease molecules. Nature. 2001;409:370–374. doi: 10.1038/35053124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fan HF, Li HW. Studying RecBCD Helicase Translocation Along chi-DNA Using Tethered Particle Motion with a Stretching Force. Biophys. J. 2009;96:1875–1883. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.11.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim JI, Cox MM. RecA protein from the extremely radioresistant bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans: expression, purification, and characterization. J. Bacteriol. 2002;184:1649–1660. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.6.1649-1660.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Galletto R, Amitani I, Baskin RJ, Kowalczykowski SC. Direct observation of individual RecA filaments assembling on single DNA molecules. Nature. 2006;443:875–878. doi: 10.1038/nature05197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lusetti SL, Wood EA, Fleming CD, Modica MJ, Korth J, Abbott L, Dwyer DW, Roca AI, Inman RB, Cox MM. C-terminal deletions of the Escherichia coli RecA protein - Characterization of in vivo and in vitro effects. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:16372–16380. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212917200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Story RM, Steitz TA. Structure if the RecA protein-ADP complex. Nature. 1992;355:374–376. doi: 10.1038/355374a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sheridan SD, Yu X, Roth R, Heuser JE, Sehorn MG, Sung P, Egelman EH, Bishop DK. A comparative analysis of Dmc1 and Rad51 nucleoprotein filaments. Nucleic Acid Res. 2008;36:4057–4066. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yin H, Landick R, Gelles J. Tethered particle motion method for studying transcript elongation by a single RNA-polymerase molecule. Biophys. J. 1994;67:2468–2478. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80735-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van der Heijden T, van Noort J, van Leest H, Kanaar R, Wyman C, Dekker N, Dekker C. Torque-limited RecA polymerization on dsDNA. Nuc. Acids Res. 2005;33:2099–2105. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shivashankar GV, Feingold M, Krichevsky O, Libchaber A. RecA polymerization on double-stranded DNA by using single-molecule manipulation: The role of ATP hydrolysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:7916–7921. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.7916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pugh BF, Cox MM. Stable binding of RecA protein to duplex DNA-unraveling a paradox. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:1326–1336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Muench KA, Bryant FR. An obligatory pH-mediated isomerization on the Asn-160 RecA protein promoted DNA strand exchange reaction pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:11560–11566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kowalczykowski SC, Clow J, Krupp RA. Properties of the duplex DNA-dependent ATPase activity of Escherichia coli RecA protein and its role in branch migration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1987;84:3127–3131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.10.3127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Strick T, Allemand JF, Croquette V, Bensimon D. Twisting and stretching single DNA molecules. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2000;74:115–140. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(00)00018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hilario J, Amitani I, Baskin RJ, Kowalczykowski SC. Direct imaging of human Rad51 nucleoprotein dynamics on individual DNA molecules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:361–368. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811965106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pugh BF, Schutte BC, Cox MM. Extent of duplex DNA underwinding induced by RecA protein binding in the presence of ATP. J. Mol. Biol. 1989;205:487–492. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90219-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van der Heijden T, Seidel R, Modesti M, Kanaar R, Wyman C, Dekker C. Real-time assembly and disassembly of human RAD51 filaments on individual DNA molecules. Nuc. Acids Res. 2007;35:5646–5657. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Roca AI, Cox MM. RecA protein: Structure, function, and role in recombinational DNA repair. Prog. Nucl. Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 1997;56:129–223. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)61005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Benedict RC, Kowalczykowski SC. Increase of the DNA strand assimilation activity of RecA protein by removal of the C-terminus and structure function studies of the resulting protein fragment. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:15513–15520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tateishi S, Horii T, Ogawa T, Ogawa H. C-Terminal truncated Escherichia coli RecA protein RecA5327 has enhanced binding affinities to single stranded and double stranded DNAs. J. Mol. Biol. 1992;223:115–129. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90720-5. 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rajan R, Bell CE. Crystal structure of RecA from Deinococcus radiodurans: Insights into the structural basis of extreme radioresistance. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;344:951–963. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.09.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.