Abstract

Chromosomal inversion polymorphism play a major role in the evolutionary dynamics of populations and species because of their effects on the patterns of genetic variability in the genomic regions within inversions. Though there is compelling evidence for the adaptive character of chromosomal polymorphisms, the mechanisms responsible for their maintenance in natural populations is not fully understood. For this type of analysis, Drosophila subobscura is a good model species as it has a rich and extensively studied chromosomal inversion polymorphism system. Here, we examine the patterns of DNA variation in two natural populations segregating for chromosomal arrangements that differentially affect the surveyed genomic region; in particular, we analyse both nucleotide substitutions and insertion/deletion variations in the genomic region encompassing the odorant-binding protein genes Obp83a and Obp83b (Obp83 region). We show that the two main gene arrangements are genetically differentiated, but are consistent with a monophyletic origin of inversions. Nevertheless, these arrangements interchange some genetic information, likely by gene conversion. We also find that the frequency spectrum-based tests indicate that the pattern of nucleotide variation is not at equilibrium; this feature probably reflects the rapid increase in the frequency of the new gene arrangement promoted by positive selection (that is an adaptive change). Furthermore, a comparative analysis of polymorphism and divergence patterns reveals a relaxation of the functional constraints at the Obp83b gene, which might be associated with particular ecological or demographic features of the Canary island endemic species D. guanche

Keywords: chromosomal gene arrangement, Drosophila subobscura, D. guanche, positive selection, inversion polymorphism, population expansion

Introduction

Chromosomal inversion polymorphism is a common feature in the genus Drosophila, and probably one of the best-studied genetic variation systems in population genetics. Three quarters of the species within the genus harbour polymorphic inversions in natural populations, and 60% of them are paracentric, that is the inversion does not include the centromere (Powell, 1997). There is a strong evidence supporting the adaptive character of the inversion polymorphism (for example Dobzhansky, 1948, 1950; Prevosti et al., 1988; Krimbas and Powell, 1992). The genetic content of the inversion and putative interactions among genes within the inverted fragment likely play a major role on the maintenance of chromosomal polymorphism and on its evolution, although the selective mechanism or mechanisms, nevertheless, is not fully understood (Dobzhansky, 1948, 1950; Puig et al., 2004).

Comparative analyses of nucleotide and chromosomal variation in inverted genomic regions provide valuable insight into the origin, age, fate and evolutionary meaning of inversion polymorphisms. Actually, a number of studies (for example Aguadé, 1988; Rozas and Aguadé, 1990, 1994; Aquadro et al., 1991; Benassi et al., 1993; Popadic et al., 1995; Babcock and Anderson, 1996; Hasson and Eanes, 1996; Rozas et al., 1999; Schaeffer et al., 2003; Nobrega et al., 2008; Kulathinal et al., 2009 and others) have shown extensive genetic differentiation between gene arrangements, a pattern that is consistent with the reduction of recombination levels expected in inversion heterozygotes (Roberts, 1976). Still, there is evidence of genetic exchange (either by gene conversion or double crossover) between gene arrangements (Rozas and Aguadé 1990, 1994; Rozas et al., 1999; Schaeffer and Anderson, 2005).

Drosophila subobscura is a good model species to study the evolutionary forces shaping nucleotide variation in genes included in chromosomal inversions as this species harbours a rich array of chromosomal polymorphisms. For instance, Rozas et al. (1999) analysed the patterns of nucleotide variation in the four major chromosomal arrangements of the O chromosome (Ost, O3+4, O3+4+8 and O3+4+23). These authors analysed the rp49 gene, which localizes within the inversion loop of the different heterokaryotypes, and found that (i) the nucleotide polymorphism patterns were consistent with a monophyletic origin of the inversions, (ii) the restricted genetic exchange between inversions was less pronounced in the central part of the inversions and (iii) nucleotide variation still reflected the selective expansion that followed the origin of the inversions, which allowed age estimation.

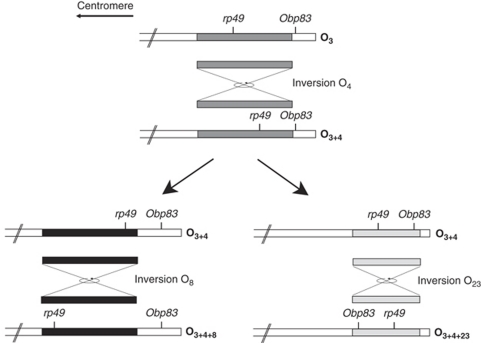

Sánchez-Gracia et al. (2003) analysed the pattern of nucleotide variation in the odorant-binding protein 83 (Obp83) genomic region, which includes the olfactory-specific genes Obp83a and Obp83b, in D. melanogaster. This region is located in the 3R chromosomal arm (Muller element E) and corresponds to the same Muller element as the O chromosome of D. subobscura. Moreover, the chromosomal localization of this region in D. subobscura (band 98D; Figure 1) lies in the small chromosomal fragment affected by inversion 23 (O23), but not by the other inversions studied in Rozas et al. (1999) (Figure 2). Therefore, the Obp83 region can be used as a specific marker of inversion O23 in D. subobscura. Analysis of the patterns of nucleotide polymorphism in this region and comparison with those observed at the rp49 gene might reveal aspects of the evolutionary history of a chromosomal inversion system not apparent in the analysis of Rozas et al. (1999).

Figure 1.

In situ hybridization on an O3+4 polytene chromosome of D. subobscura using the complete Obp83 region as a biotinylated probe. The arrow indicates the hybridization signal.

Figure 2.

Scheme of the location of the Obp83 and rp49 regions (Rozas and Aguadé, 1994) in different chromosomal arrangements of D. subobscura. Shaded bars indicate the regions affected by inversions. O3 refers to a gene arrangement not present in extant populations of D. subobscura.

Here, we study the patterns of nucleotide variation in two gene arrangements from two different populations that are differentiated by chromosomal inversion O23. Furthermore, we introduce a new method to estimate insertion/deletion (InDel) variation and compare deletion–insertion polymorphisms patterns with those estimated by nucleotide substitutions. On the other hand, the Obp83a and Obp83b genes belong to one of the major insect chemosensory multigene families, the OBP gene family (Vieira et al., 2007; Sánchez-Gracia et al., 2009), and originated by tandem gene duplication before the split between Sophophora and Drosophila subgenera (Sánchez-Gracia and Rozas, 2008). Earlier studies across the Drosophila genus indicated that these two genes have been affected by positive selection. Hence, we also examined the nucleotide divergence between D. subobscura and D. guanche, a phylogenetically close species restricted to some isolated gorges of Tenerife Island, Canary Archipelago. Comparative analysis of nucleotide polymorphisms and divergence will allow us to analyse the impact of natural selection on these chemosensory genes.

We find that the pattern of molecular variation in the Obp83 region is highly similar to that observed in the rp49 gene. The region is not at steady-state equilibrium, but instead reflects the expansion process caused by the increase in frequency of the chromosomal inversion. We show that inversion O23 has a monophyletic origin and that the gene arrangements are well differentiated in spite of the existence of some genetic exchange between them. From the patterns and levels of both nucleotide and InDel polymorphisms in the Obp83 region, we estimate the age of inversion O23 is about 0.2–0.3 million years. Interestingly, the patterns of nucleotide and InDel variation are very similar in the two gene arrangements; this feature reveals a linkage effect caused by the close proximity to the breakpoint of inversion 4 (O4). On the other hand, the comparative analysis of polymorphism and divergence patterns exposed differences in the selective constraint levels of the Obp83a and Obp83b genes, likely associated with the endemic nature of D. guanche.

Materials and methods

Fly samples

We sequenced the complete Obp83 region in 29 D. subobscura isochromosomal lines (8 from El Pedroso, Spain and 21 from Bizerte, Tunisia). The chromosomal arrangement of each line was determined earlier (Rozas et al., 1999). We mapped by in situ hybridization the cytological location of the Obp83 region in D. subobscura using a modification of the Montgomery et al. (1987) protocol (Segarra and Aguadé, 1992). We also sequenced the complete Obp83 genomic region in one highly inbred line (after 10 generations of sib mating) of D. guanche (kindly provided by G Periquet).

DNA sequencing

The genomic DNA from the El Pedroso lines was obtained after Kreitman and Aguadé (1986), whereas that from Bizerte and D. guanche was extracted using a modification of protocol 48 from Ashburner (1989). In D. subobscura, an ∼4.5 kb region, including the complete Obp83b coding region and a fraction of the Obp83a gene, was amplified by PCR (Saiki et al., 1988) using oligonucleotides designed in conserved regions among three species of the melanogaster subgroup of Drosophila (Sánchez-Gracia et al., 2003). The 3′ fragment of the Obp83a gene was obtained by the inverse-PCR technique (Ochman et al., 1988). The amplified fragments were cycle sequenced using oligonucleotides designed at intervals of ∼400 nucleotides, and then separated on a Perkin-Elmer (Norwalk, CT) ABI PRISM 3700 automated DNA sequencer following the manufacturer's instructions. For each line, we determined the DNA sequence of both strands (∼6 kb). The new sequence data were deposited in the EMBL, GenBank and DDBJ Nucleotide Sequence Databases under the accession numbers FN650673-FN650701 (D. subobscura) and FM210100 (D. guanche).

Data analysis

The DNA sequences were aligned by the Clustal W programme (Thompson et al., 1994). The initial alignments were further optimized using the MacClade programme, version 3.06 (Maddison and Maddison, 1992). We estimated the maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic tree by PhyML, version 2.4.4 (Guindon and Gascuel, 2003); bootstrap values were based on 1000 replicates. The Obp83 region of D. guanche was used as outgroup for the analysis. The DnaSP programme, version 5.00.7 (Librado and Rozas, 2009), was used to estimate nucleotide diversity, genetic distances and genetic differentiation, to detect putative gene conversion tracts and to conduct neutrality tests. Nucleotide diversity, π, was estimated as the number of nucleotide differences per site (Nei, 1987), whereas pairwise nucleotide divergence, K, was obtained using the Jukes and Cantor (1969) substitution model. We also estimated branch-specific synonymous (dS) and non-synonymous (dN) substitution rates as well as their ratio (ω) by ML using the PAML 4 programme (Yang, 2007). In this work, the term silent nucleotide variation (SIL, indicated as a subscript) is used to describe variation in the non-coding fragment and in the synonymous sites along the coding region. DNA divergence between gene arrangements was calculated as Dxy, the per-site average number of nucleotide substitutions between populations (or chromosomal arrangements), and as Da, the net number of nucleotide substitutions per site between populations (Nei, 1987).

We also used a new method to infer the number of InDel events from the data and to estimate several measures of the level and pattern of InDel polymorphisms (average InDel length, InDel diversity and InDel-based neutrality statistics). We also estimated a neighbour joining tree of the Obp83 region using InDel events information. InDel events were identified using a modification of the Simmons and Ochoterena (2000) method. In brief, we consider InDels with the same 5′ and 3′ termini homologous (that is represent a single mutational event); therefore, InDels of different lengths (even in the same position of the alignment) are treated as different events. For the analysis, we used only InDel events with a maximum overlap of three events in a specific position (Tetraallelic option) (see Librado and Rozas, 2009). InDel estimates were compared with those obtained from nucleotide substitution information. We have implemented this method as a new module in the DnaSP software (Librado and Rozas, 2009).

The proportion of nucleotide diversity attributable to variation between gene arrangements, Fst, was estimated after Hudson et al. (1992). The Snn statistic (Hudson, 2000) was used to test for genetic differentiation; statistical significance was assessed by the permutation test (based on 10 000 replicates).

We applied the McDonald and Kreitman (1991) test (MK test) to examine whether the number of polymorphic and fixed synonymous and non-synonymous substitutions conformed to or deviated from the neutral theoretical expectations. We also estimated Tajima's D (Tajima, 1989), Fu's Fs (Fu, 1997) and R2 (Ramos-Onsins and Rozas, 2002) statistics to test for deviations in the distribution of intraspecific nucleotide variation; the 95% confidence intervals of these statistics were obtained by coalescent (Hudson, 1990) computer simulations with recombination (1000 replicates). We estimated the population recombination parameter C (C=4Nec, where Ne is the effective population size and c is the recombination rate per generation for the complete Obp83 region) using the method described in Hudson (1987). We also estimated the conservative value of CL (Rozas et al., 2001), which represents the minimum value of C compatible (at 5%, under the neutral model) with the minimum number of recombination events RM (Hudson and Kaplan, 1985) inferred in the data. We used the algorithm described in Betran et al. (1997) to identify putative gene conversion tracts in the sample. We estimated the linkage disequilibrium (LD) between pairs of polymorphic sites by the r2 statistic (Hill and Robertson, 1968) and the global level of LD by the ZnS parameter (Kelly, 1997). The statistical significance of ZnS was assessed by coalescent simulations.

We studied the effect of positive selection on particular lineages by contrasting ML estimates of the ω parameter (see above) under different evolutionary models (implemented in PAML 4.3 package; Yang, 2007). In particular, we applied the two tests described in Zhang et al. (2005) to a data file containing the Obp83b coding region of D. subobscura, D. guanche, D. madeirensis, D. persimilis, D. miranda and D. pseudoobscura (data from Sánchez-Gracia and Rozas, 2008). In test 1, the fit to the data of a model that allows only neutral evolving sites in all branches (model M1; Yang et al., 2000) is compared with a model that allows a given proportion of positively selected sites in a particular branch MA model (Yang and Nielsen, 2002; Zhang et al., 2005). In test 2, the M1 model is replaced by a null model (MA in Zhang et al., 2005) that assumes a complete relaxation rather than positive selection (that is dN/dS=1) in the same specified branch. The statistical significance was evaluated by applying the conservative likelihood ratio test, which assumes that twice the log likelihood difference between models follows a χ2 distribution with one degree of freedom (Zhang et al., 2005).

Results

Cytological location of the Obp83 region

In situ hybridization on polytene chromosomes shows a unique signal located on cytological band 98D of the O chromosome of D. subobscura (Figure 1). This chromosomal position lies within paracentric inversion O23, which defines two major recombination-restricted chromosomal groups, the O[3+4] (including O3+4+7 and O3+4+8; 15 sequences) and the O3+4+23 (14 sequences) (Figure 2). All eight lines from El Pedroso harbour the O3+4+7 arrangement.

Overall nucleotide variation

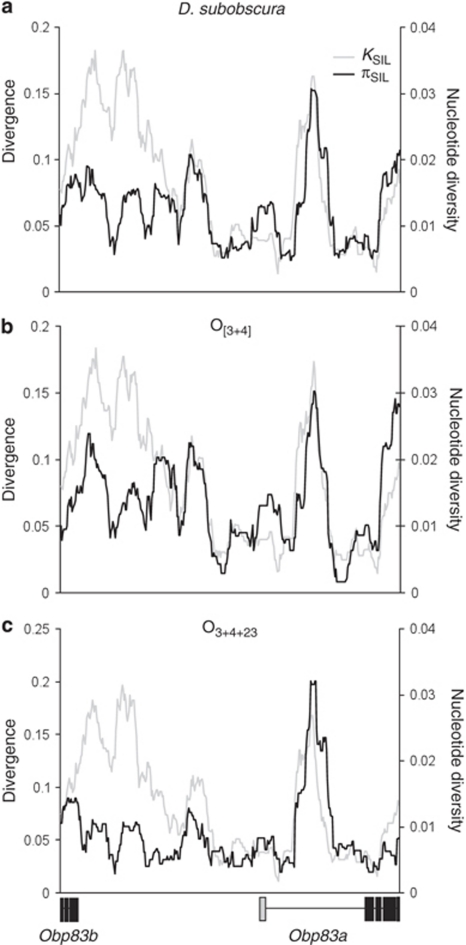

The sequenced Obp83 region extends over 5808 bp (5202 bp if excluding sites with alignment gaps). The genetic structure is the same as that of D. melanogaster; nevertheless, the intergenic region is shorter in D. melanogaster (∼1 kb) than in D. subobscura (∼2.5 kb). Table 1 summarizes the levels of nucleotide polymorphism and divergence in the different functional parts of the Obp83 region. We detected 377 segregating sites (representing a minimum of 394 mutational events) among the 29 lines of D. subobscura; 8 of these polymorphisms are non-synonymous (Supplementary Figure S1). The average nucleotide diversity (πT) is 0.0112. We also inferred a total of 116 InDel events in the complete dataset; 36 were excluded from the analysis as they presented four or more overlapping InDel events. The 80 analysed InDel events have an average length of 4.59 bp and a per-sequence InDel event diversity of 14.6. Figure 3 shows the distribution of silent nucleotide polymorphisms and divergence throughout the Obp83 region. As in D. melanogaster and D. simulans (Sánchez-Gracia et al., 2003; Sánchez-Gracia and Rozas, 2007), the level of silent variation is lower in the Obp83a gene than in Obp83b and intergenic regions (except for a highly variable ∼300-bp fragment in the first intron of the Obp83a gene). Nevertheless, the HKA test does not reject the hypothesis that polymorphism and divergence are correlated, as expected under the neutral model (HKA test, results not shown).

Table 1. Summary of nucleotide variation at the Obp83 region in D. subobscura.

| Obp83a | Intergenic | Obp83b | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silent | ||||

| S | 25 | 219 | 142 | 386 |

| lSIa | 311.58 | 2155 | 2007.47 | 4474.05 |

| πSIL | 0.0120 | 0.0139 | 0.0119 | 0.0129 |

| KSIL | 0.0784 | 0.0982 | 0.0578 | 0.0790 |

| Synonymous | ||||

| S | 14 | 12 | 26 | |

| lSa | 89.58 | — | 106.47 | 196.05 |

| πS | 0.0195 | — | 0.0196 | 0.0196 |

| KS | 0.1351 | — | 0.0924 | 0.0112 |

| Non-coding | ||||

| S | 11 | 219 | 130 | 360 |

| lNCa | 222 | 2155 | 1901 | 4278 |

| πNC | 0.0089 | 0.0139 | 0.0115 | 0.0126 |

| KNC | 0.0565 | 0.0982 | 0.0555 | 0.0773 |

Abbreviations: l, number of sites; π, nucleotide diversity; K, nucleotide divergence between D. subobscura and D. guanche.

Number of sites in polymorphism data set. The SIL, S and NC subscripts indicate silent, synonymous and non-coding positions, respectively.

Figure 3.

Sliding window of silent polymorphism in D. subobscura (black line) and silent divergence between D. subobscura and D. guanche (grey line) in the Obp83 region. (a) Total D. subobscura data; (b) O[3+4] chromosomal arrangement and (c) O3+4+23 chromosomal arrangement.

Polymorphic and fixed (between D. subobscura and D. guanche) synonymous and non-synonymous mutations, however, do not correlate (MK test, P=0.033); the Obp83b gene is responsible for this departure (Obp83b, P=0.004; Obp83a, P=0.851) (Table 2). Nevertheless, the results of the MK test using only nucleotide substitutions fixed in the lineage leading to D. subobscura (using D. pseudoobscura to polarize mutations) were not significant (P=0.330); therefore, the Obp83b gene has evolved neutrally in D. subobscura. We also analysed the patterns of synonymous and non-synonymous substitutions in the Obp83 coding region of D. guanche. The ML analysis at the Obp83b coding region of D. guanche (branch-site approach) indicates that positive selection might act on some codon sites of this gene (test 1 in Zhang et al., 2005; P=0.006). The hypothesis that selective pressure acting on these sites may be relaxed (that is dN/dS=1), however, cannot be rejected (test 2 in Zhang et al., 2005; P=0.329). Consequently, a reduction in functional constraint is the most plausible explanation for the excess of amino-acid replacements observed in D. guanche.

Table 2. McDonald and Kreitman test.

| PS | PNS | FSa | FNSa | P-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O[3+4] | |||||

| Obp83b | 9 | 1 | 8 | 12 | 0.011 |

| Obp83a | 9 | 3 | 8 | 2 | 0.782 |

| O3+4+23 | |||||

| Obp83b | 6 | 1 | 10 | 12 | 0.074 |

| Obp83a | 4 | 4 | 7 | 2 | 0.957 |

| Total | |||||

| Obp83b | 14 | 2 | 8 | 12 | 0.004 |

| Obp83a | 12 | 6 | 7 | 2 | 0.851 |

| Obp83 region | 26 | 7 | 15 | 14 | 0.024 |

Abbreviations: FNS, fixed non-synonymous; FS, fixed synonymous; PNS, polymorphic non-synonymous; PS, polymorphic synonymous.

Substitutions between D. subobscura and D. guanche.

One-tailed Fisher's exact test.

Nucleotide variation and chromosome arrangements

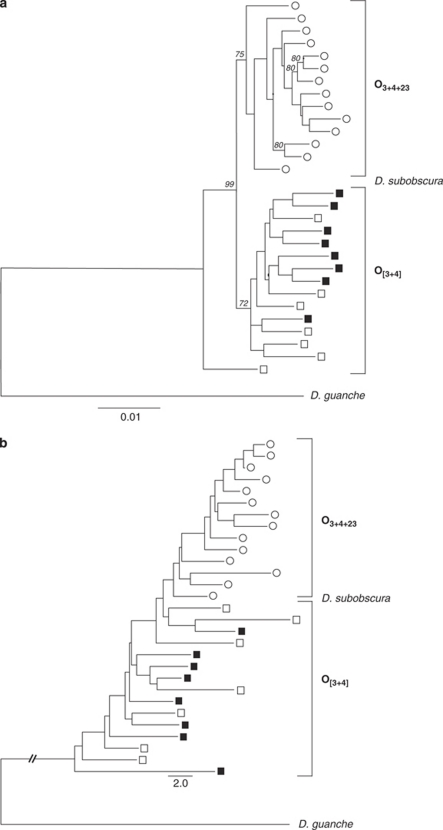

Table 3 summarizes the genetic differentiation between O[3+4] and O3+4+23 classes. The Dxy and Da values (Dxy=0.0125; Da=0.0028) indicate that the two gene arrangements are highly divergent with respect to the intrachromosomal nucleotide diversity levels; even so, there are 50 DNA polymorphisms shared between the arrangements, with no fixed difference between them. The genetic differentiation analyses clearly indicates that the two chromosomal classes are highly differentiated (Snn=0.965; P<0.0001), whereas lines from O[3+4] (the only gene arrangement present in both populations) are not differentiated between El Pedroso and Bizerte populations (Snn=0.700; P=0.082). We also examined whether this number of shared mutations (between arrangements) could have arisen independently in each arrangement (parallel mutations) or whether they might have been incorporated by some recombination mechanisms. Assuming a homogeneous mutation rate across silent sites, our results indicate that this observed number of shared mutations is extremely unlikely under the parallel mutation scenario (the expected number of shared polymorphisms is 2.67±1.6, P<0.001). Therefore, these shared polymorphisms should be explained by recombination between chromosomal classes. The Betran et al. (1997) algorithm allowed us to identify six putative gene conversion tracts, with length sizes ranging from 2 to 397 bp (Supplementary Figure S1); these tracts do not show any significant directionality, and their average lengths are quite similar in both gene arrangements. Interestingly, after removing the strains with the observed gene conversion tracts, some shared polymorphisms still remain, suggesting the existence of additional gene conversion tracts undetected by the Betran et al. (1997) algorithm. The Obp83 region phylogenetic trees exhibit two clearly separated clusters, which correspond to the two chromosomal classes (Figure 4). This feature confirms that the genetic structure observed in the data was mainly caused by the inversion polymorphism (recombination reduction in heterokaryotypes), and not by some form of population differentiation. Markedly, topologies indicate that the O23 chromosomal inversion has a monophyletic origin. There is, nevertheless, a DNA sequence (line TB132) with a basal position in the ML tree. This sequence could have been incorporated by gene conversion information from other chromosomal inversions not surveyed in our study. Markedly, results of the neighbour joining phylogenetic tree using only InDel event genetic information are completely concordant with those of nucleotide substitution: all O3+4+23 lines are grouped in just one cluster. Moreover, the neighbour joining tree also uncovers a relatively more basal position of O[3+4] chromosomes.

Table 3. Genetic differentiation between chromosomal arrangements.

| Shared | Fixed | Dxy | Da | Fst | Snn | ψ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O[3+4]–O3+4+23 | 50***,a | 0 | 0.0125 | 0.0028 | 0.224 | 0.965*** | 0.003 |

Based on the hypergeometric distribution. *** P<0.001.

Figure 4.

(a) ML tree of the Obp83 region. Italic numbers indicate the percentage of bootstrap replicates (1000 replicates) supporting the main nodes (only bootstrap values higher than 70% are shown). (b) Neighbour joining tree of the Obp83 region. Trees were built using either nucleotide substitutions (a) or InDel events (b) information, and rooted with the D. guanche sequence. The scale bars in (a, b) indicate the number of substitutions per site and the number of InDel events, respectively. Lines from Bizerte and El Pedroso populations are depicted in white and black, respectively, whereas those of O[3+4] and O3+4+23 arrangements are represented by a square and a circle, respectively.

Table 4 summarizes the nucleotide polymorphisms of each gene arrangement. The level of silent polymorphism is higher in the O[3+4] than in the O3+4+23 sequences. Nevertheless, the silent diversity profiles along the Obp83 region are similar in the two chromosomal classes and correlate with silent divergence estimates (Figure 3). Interestingly, the per-gene recombination levels (C=424 and C=567 for O[3+4] and O3+4+23, respectively) are much higher than those expected in a region located close to the telomere (Table 4). This high level of recombination is in agreement with the low LD values (Table 4). In fact, the ZnS estimates are highly incompatible (P<0.001), even using the conservative CL values in the coalescent simulations, and the LD patterns noticeably decay with physical distance (Figure 5). Nevertheless, there are differences between gene arrangements: although there is no significant LD polymorphic pair in O[3+4], there are 899 (out 11 628 comparisons; χ2-test) in O3+4+23 (although none was significant when applying the conservative Bonferroni procedure; Weir, 1996), which could be in agreement with the different ages estimates for these two arrangements (Rozas et al., 1999; but also see below).

Table 4. Nucleotide variation, recombination values and neutrality tests at Obp83 region in different gene arrangements.

| O[3+4] | O3+4+23 | |

|---|---|---|

| n | 15 | 14 |

| ηSIL | 296 | 154 |

| lSIL | 4535.12 | 4639.32 |

| πSIL | 0.0141 | 0.0085 |

| KSIL | 0.0795 | 0.0789 |

| Tajima's D | −1.339*** | −0.896** |

| Fu's Fs | −1.273 | −1.917 |

| Ramos-Onsins and Rozas R2 | 0.074*** | 0.087*** |

| C | 424 | 567 |

| CL | 100 | 80 |

| ZnS | 0.0818*** | 0.0820*** |

Abbreviations: n, sample size; ηSIL, number of silent mutations; lSIL, total number of silent sites analysed; πSIL, silent nucleotide diversity; KSIL, silent nucleotide divergence between D. subobscura and D. guanche. P-values are calculated from simulations with recombination (C=CL). **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Figure 5.

LD r2 statistic (Hill and Robertson, 1968) between pairs of polymorphic sites across the Obp83 genomic region in the two chromosomal arrangements. (a) O[3+4] chromosomal arrangement and (b) O3+4+23 chromosomal arrangement. Black line represents the straight-line fit to the plot using least squares regression.

We tested for departures from the standard neutral model using three different types of statistical tests: Tajima's D (Tajima, 1989), Fu's Fs (Fu, 1997) and Ramos and Rozas' R2 (Ramos-Onsins and Rozas, 2002). Both chromosomal arrangements have significant negative Tajima's D and R2 values; the results of Fu's Fs, nevertheless, are not significant using the CL value in the coalescent simulations model (CL=200 and 80 for O[3+4] and O3+4+23, respectively) (Table 4). As gene conversion events might inflate lower values of the statistics, we also conducted the tests after subtracting either nucleotide variants likely incorporated by gene conversion tracts or the complete lines involved; in all cases, the new tests did not change the results (results not shown). All results indicate that nucleotide variation patterns within the gene arrangements are not compatible with those expected for a constant-size population. Noticeably, the deletion–insertion polymorphisms analyses are in agreement with the nucleotide substitution results (Table 5). Our results, therefore, reveal the existence of a recent and severe population-growth event.

Table 5. InDel diversity and neutrality tests at Obp83 region in different gene arrangements.

| O[3+4] | O3+4+23 | |

|---|---|---|

| n | 15 | 14 |

| I | 69 | 33 |

| ΛI | 4.53 | 3.85 |

| πI | 0.0029 | 0.0016 |

| Tajima's D | −1.042** | −0.632 |

| Fu's Fs | −5.130 | −7.190 |

| Ramos-Onsins and Rozas R2 | 0.089** | 0.101* |

Abbreviations: n, sample size; I, number of tetraallelic InDel events; ΛI, average InDel length event; πI, InDel event diversity per site. P-values are calculated from simulations with recombination (C=CL). *0.01<P<0.05, **P<0.01.

We have used DNA polymorphism data to date the origin of inversion O23. For this analysis, we assume that (i) this inversion is monophyletic, (ii) all nucleotide variation within the arrangement originated after the origin of the inversion and (iii) the nucleotide variation within the gene arrangement is not at equilibrium and still reflects the molecular signature of the expansion process. As we have detected transfer of genetic information by gene conversion between arrangements, we subtracted all nucleotide variation likely incorporated by this process. Assuming that the split of D. guanche and D. subobscura occurred 1.8–2.8 million years (Ramos-Onsins and Aguade, 1998), from the per-site silent divergence between these species (KSIL=0.079), we can estimate the per-site and per-year silent nucleotide substitution rates in the Obp83 region (λ=2.19 × 10−8 or 1.41 × 10−8, respectively). After Rozas et al. (1999) and using current silent polymorphism estimates (πSIL=0.0085), the origin of inversion O23 occurred about 0.19 or 0.29 million years. Interestingly, the patterns of InDel diversity are also in full agreement with those based on nucleotide substitution. The number of both InDel events and both InDel diversity is also higher in O[3+4] than in O3+4+23. And, very remarkably, the estimates of the origin of inversion O23 calculated using InDel polymorphism (πI=0.0016) and divergence (KI=0.0166) information (therefore, λI=4.61 × 10−9 or 2.96 × 10−9) are also in agreement (0.17 and 0.27 million years, respectively) with nucleotide substitution estimates.

Discussion

Nucleotide variation and chromosome polymorphism

The cytological location of the Obp83 region in D. subobscura (close to the internal part of one of the breakpoints of inversion O23) provides an opportunity to study the evolutionary consequences of chromosomal polymorphisms by contrasting nucleotide and chromosomal variation. This study has two important features: (i) we surveyed a continuous genomic region of ∼6 kb affected by only a single inversion, which significantly improves the statistical power of the earlier analysis of Rozas et al. (1999) and (ii) we also used InDel variation data, which allows comparison between different markers and, therefore, increases the robustness of evolutionary inferences. We show that gene arrangements are well differentiated, as expected by the suppression of recombination in heterokaryotypes. The high levels of recombination and the low LD values detected in the homokaryotypes clearly indicate that this suppression of recombination between gene arrangements is not caused by the telomere proximity of the Obp83 region. This suppression, however, is not complete; in fact, the number of shared substitutions between arrangements is higher than expected for an independent accumulation of mutations. That is, the reduction in recombination between gene arrangements occurs in spite of some forms of recombination (by double crossing over or gene conversion) between gene arrangements. Actually, we identified several gene conversion tracts between chromosomal classes, a relevant mechanism in the genetic exchange between inversions (Rozas and Aguadé, 1994; Navarro-Sabate et al., 1999; Rozas et al., 1999; Munte et al., 2005). The two highly differentiated clades in phylogenetic trees of the Obp83 region (Figure 4) also reveal that the suppression of recombination is a major mechanism in the evolution of chromosomal inversions; in addition, these trees support the monophyletic origin of this inversion. These results agree with those reported by Rozas et al. (1999) in their analysis of other genomic regions and inversion systems. It should be noted, however, that one of the O[3+4] sequences (line TB132) does not group according to its chromosomal class in the ML tree. This line exhibits a small gene conversion tract, and perhaps might have also incorporated genetic information from other gene arrangements not surveyed in this study. In any case, it is important to note that genomic regions with a stable suppression of recombination might have an important function in evolutionary processes such as speciation; hence, inversions can generate genetically differentiated regions that may contribute to genetic isolation, despite the gene flow caused by hybridization (for example Kulathinal et al., 2009). Indeed, inversions carrying chemosensory system genes (especially in pheromone perception, oviposition sites or food detection) can be good candidates for participation in this process.

A rapid increase in the frequency of an inversion, from its origin (monophyletic) to its current frequency, can leave a recognizable signature in the pattern of DNA molecular diversity for some (relatively short) period of time. This effect, in fact, can be envisaged as a population-growth event (Rogers and Harpending, 1992; Harpending, 1994) and can, therefore, generate star-shaped genealogies. Rozas et al. (1999) found negative Tajima's D values at the rp49 gene in all gene arrangements surveyed. Although the neutral model was not rejected, they found signatures of gene arrangement expansion using the raggedness r statistic in all gene arrangements except O3+4+23. In this context, the R2 and Fs coalescent-based neutrality statistical tests are more powerful to detect population-growth events and are less sensitive to recombination than mismatch distribution-based statistics (Ramos-Onsins and Rozas, 2002; Ramirez-Soriano et al., 2008). In addition, for small sample sizes and high recombination rates, as in our case, the R2 statistic is even more powerful than Fs (Ramos-Onsins and Rozas, 2002). Interestingly, we obtain significant R2 values in the two gene arrangements, as expected in the given population (or chromosomal arrangement, in this case) growth. Noticeably, the analysis using InDel polymorphisms yielded the same conclusion. Therefore, the joint use of nucleotide and InDel polymorphism data makes the analysis much more robust, as it is less affected by putative-specific features of nucleotide substitutions (that is mutation rate or selection coefficient).

Consequently, the surveyed gene arrangements are not at steady-state equilibrium, and the DNA variation pattern still reflects an adaptive increase in frequency driven by positive selection. Nevertheless, the multilocus analysis of Munte et al. (2005) in D. subobscura showed that genetic differentiation between inversions might extend all over the inverted region, therefore, having a relatively homogeneous genetic exchange along the inversion. This feature makes it difficult to identify the putative target of positive selection. Therefore, it is not possible to address this issue by examining a single genomic region. Moreover, current data are uninformative regarding the evolutionary fate of this inversion (that is whether the gene arrangement has reached its frequency equilibrium or if it will continue increasing in frequency until fixed in the population).

In spite of that limitation, under this scenario, we estimate that the O23 inversion originated about 0.2–0.3 million years. As an inversion might need at least 107 generations to reach equilibrium frequency in a species such as D. subobscura (Navarro et al., 2000) (about 2 million years in D. subobscura, assuming five generations per year, Ashburner, 1989; Powell, 1997), these estimates for the origin of the inversion are consistent with the non-equilibrium state of the O3+4+23 chromosomal arrangement. This estimated origin is slightly more recent than those estimated for other inversions of the O chromosome and is in agreement with the evolutionary history of the O chromosome inversions of D. subobscura (Rozas et al., 1999).

Unexpectedly, we also detect the expansion signature in the Obp83 region from O[3+4] samples. Inversion O4 is also a derived inversion (see Figure 2), originating from the O3 arrangement about 0.3–0.5 million years (Rozas et al., 1999), and its nucleotide variation has probably not reached steady-state equilibrium in the population. As the Obp83 region is outside the inverted fragments affecting the O[3+4] and Ost arrangements (that is the genomic region is not within the chromosomal fragment covering inversions 3, 4 and 8; see Rozas et al. 1999), we might expect that nucleotide variation was at equilibrium. Nevertheless, the region is very close to the external part of one breakpoint of inversion O4; therefore, we might expect a reduction of recombination between this inverted fragment and the surveyed region in heterokaryotypes. In this case, the evolutionary fate of the Obp83 region at the O[3+4] might be affected by this partial linkage to the inversion. In fact, assuming complete linkage, we can estimate the age for the origin of inversion O4 using the specific Obp83 evolutionary rates. These estimates are in concordance with that estimated from the rp49 region—a marker located inside the inverted fragment (0.32–0.50 million years; Rozas et al., 1999). Alternatively, the fact that the DNA signature is in both the O[3+4] and the O3+4+23 arrangements might be explained by a demographic event affecting the entire genome. However, results showing that the different inversions have different ages, along with the observation that these ages are in agreement with the genealogical history of D. subobscura inversions (Krimbas and Powell, 1992; Rozas et al., 1999), clearly point to gene arrangement expansion as the most plausible explanation for the data.

Impact of natural selection on the Obp83 genomic region

Estimates of silent nucleotide diversity in the Obp83 region of D. subobscura are higher than those determined in European populations of D. melanogaster and D. simulans (Sánchez-Gracia et al., 2003; Sánchez-Gracia and Rozas, 2007). This high level of DNA variation allowed us to conduct a fine analysis of the functional constraints along the Obp83 region. Overall levels of silent nucleotide variation in the Obp83b gene and intergenic regions are higher than those estimated at the Obp83a gene, with the exception of some parts of the first large intron of this gene (Figure 3). Noticeably, this pattern is equivalent to that observed in D. melanogaster and D. simulans. This heterogeneity in silent variation levels across non-coding regions might result from differences in functional constraints. Moreover, we identified two extremely conserved non-coding regions in the large intron of the Obp83a gene; these regions likely include important regulatory elements and warrant further investigation. As the levels of silent variation in these conserved regions are even lower than those at the synonymous positions in the same gene, we might discard the possibility that putative differences in the local mutation rate are responsible for this effect.

Finally, we also found significant results of the MK test in the Obp83b gene. Navarro-Sabate et al. (2003) also reported significant MK values in the Acph-1 gene when analysing chromosomal inversions of D. subobscura. In the latter study, however, there was an excess of non-synonymous polymorphisms. Our survey instead reveals that the D. guanche lineage—not D. subobscura—is mainly responsible for the departure from the neutral expectations. The excess of amino-acid changes fixed in D. guanche might have been promoted by natural selection favouring mutations that conferred advantages to the new environment occupied by this endemic species. Only under this scenario can the ω ratio be higher than one. Nevertheless, the estimate of the synonymous rate (dS=0.0570) in the Obp83b gene of the D. guanche lineage is higher than that of the non-synonymous rate (dN=0.0285); therefore, we cannot reject the hypothesis that most fixed amino acids in D. guanche were, in fact, nearly neutral substitutions. However, positive selection can act on only a few amino-acid positions; in this case, testing for positive selection using estimates of synonymous and non-synonymous substitutions at the whole gene level would be highly conservative. The results of the branch sites of ML analysis, nevertheless, again point to the relaxation of functional constraints on the Obp83b protein as the most plausible explanation for the observed excess of amino-acid changes in D. guanche (see also Sánchez-Gracia and Rozas, 2008). This excess might be caused by an increase in the fixation probability of nearly neutral mutations (Ohta and Kimura, 1971; Ohta, 1972) expected in species such as D. guanche with small effective population sizes (Llopart and Aguadé, 2000; Perez et al., 2003). Under this hypothesis, an increase of the ω ratio is expected, but never over the neutral rate.

In conclusion, we show that natural selection is a major mechanism driving the evolution of the Obp83 genomic region in these Drosophila species. The patterns of DNA polymorphism in the complete genomic region clearly show the footprint of the selective sweep associated with the rapid increase in frequency of the new gene arrangement. Likewise, features associated with the endemic nature of D. guanche are likely to be involved in the reduction of the effectiveness of natural selection acting on the Obp83b gene in this species.

Acknowledgments

We thank Carmen Segarra for her valuable contribution in performing the in situ hybridization. We also thank Serveis Cientifico-Tècnics, Universitat de Barcelona, for automated sequencing facilities. This work was funded by grants BFU2004-02253 and BFU2007-62927 from the Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia (Spain) and 2005SRG-00166 from Comissió Inter-departamental de Recerca I Innovació Tecnològica (Spain).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on Heredity website (http://www.nature.com/hdy)

Supplementary Material

References

- Aguadé M. Restriction map variation at the Adh locus of Drosophila melanogaster in inverted and noninverted chromosomes. Genetics. 1988;119:135–140. doi: 10.1093/genetics/119.1.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aquadro CF, Weaver AL, Schaeffer SW, Anderson WW. Molecular evolution of inversions in Drosophila pseudoobscura: the amylase gene region. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:305–309. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.1.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner M. Drosophila: A Laboratory Handbook. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: New York; 1989. p. 476. [Google Scholar]

- Babcock CS, Anderson WW. Molecular evolution of the sex-ratio inversion complex in Drosophila pseudoobscura: analysis of the Esterase-5 gene region. Mol Biol Evol. 1996;13:297–308. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benassi V, Aulard S, Mazeau S, Veuille M. Molecular variation of Adh and P6 genes in an African population of Drosophila melanogaster and its relation to chromosomal inversions. Genetics. 1993;134:789–799. doi: 10.1093/genetics/134.3.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betran E, Rozas J, Navarro A, Barbadilla A. The estimation of the number and the length distribution of gene conversion tracts from population DNA sequence data. Genetics. 1997;146:89–99. doi: 10.1093/genetics/146.1.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobzhansky T. Genetics of natural populations. XVIII. Experiments on chormosomes of Drosophila pseudoobscura from differents geographic regions. Genetics. 1948;33:588–602. doi: 10.1093/genetics/33.6.588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobzhansky T. Genetics of natural populations. XIX. Origin of heterosis through natural selection in populations of Drosophila pseudoobscura. Genetics. 1950;35:288–302. doi: 10.1093/genetics/35.3.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu YX. Statistical tests of neutrality of mutations against population growth, hitchhiking and background selection. Genetics. 1997;147:915–925. doi: 10.1093/genetics/147.2.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S, Gascuel O. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst Biol. 2003;52:696–704. doi: 10.1080/10635150390235520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harpending HC. Signature of ancient population growth in a low-resolution mitochondrial DNA mismatch distribution. Hum Biol. 1994;66:591–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasson E, Eanes WF. Contrasting histories of three gene regions associated with In(3L)Payne of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1996;144:1565–1575. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.4.1565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill WG, Robertson A. Linkage disequilibrium in finite populations. Theor Appl Genet. 1968;38:226–231. doi: 10.1007/BF01245622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson RR. Estimating the recombination parameter of a finite population model without selection. Genet Res. 1987;50:245–250. doi: 10.1017/s0016672300023776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson RR.1990Gene genealogies and the coalescent processIn: Antonovics J and Futuyma D (eds).Oxford Surveys in Evolutionary BiologyVol. 7. Oxford University Press: Oxford; 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson RR. A new statistic for detecting genetic differentiation. Genetics. 2000;155:2011–2014. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.4.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson RR, Kaplan NL. Statistical properties of the number of recombination events in the history of a sample of DNA sequences. Genetics. 1985;111:147–164. doi: 10.1093/genetics/111.1.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson RR, Slatkin M, Maddison WP. Estimation of levels of gene flow from DNA sequence data. Genetics. 1992;132:583–589. doi: 10.1093/genetics/132.2.583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jukes TH, Cantor CR.1969Evolution of protein moleculesIn: Munro HN (ed).Mammalian Protein Metabolism Academic Press: New York; 21–123. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JK. A test of neutrality based on interlocus associations. Genetics. 1997;146:1197–1206. doi: 10.1093/genetics/146.3.1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreitman M, Aguadé M. Genetic uniformity in two populations of Drosophila melanogaster as revealed by filter hybridization of four-nucleotide-recognizing restriction enzyme digests. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:3562–3566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.10.3562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krimbas CB, Powell JR. Drosophila Inversion Polymorphism. CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL; 1992. p. 560. [Google Scholar]

- Kulathinal RJ, Stevison LS, Noor MA. The genomics of speciation in Drosophila: diversity, divergence, and introgression estimated using low-coverage genome sequencing. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000550. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Librado P, Rozas J. DnaSP v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1451–1452. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llopart A, Aguadé M. Nucleotide polymorphism at the RpII215 gene in Drosophila subobscura. Weak selection on synonymous mutations. Genetics. 2000;155:1245–1252. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.3.1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddison WP, Maddison DR.1992MacClade: Analysis of Phylogeny and Character EvolutionVersion 3Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA [Google Scholar]

- McDonald JH, Kreitman M. Adaptive protein evolution at the Adh locus in Drosophila. Nature. 1991;351:652–654. doi: 10.1038/351652a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery E, Charlesworth B, Langley CH. A test for the role of natural selection in the stabilization of transposable element copy number in a population of Drosophila melanogaster. Genet Res. 1987;49:31–41. doi: 10.1017/s0016672300026707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munte A, Rozas J, Aguadé M, Segarra C. Chromosomal inversion polymorphism leads to extensive genetic structure: a multilocus survey in Drosophila subobscura. Genetics. 2005;169:1573–1581. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.032748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro A, Barbadilla A, Ruiz A. Effect of inversion polymorphism on the nucleotide variability of linked chromosomal regions. Genetics. 2000;155:685–689. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.2.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-Sabate A, Aguadé M, Segarra C. The relationship between allozyme and chromosomal polymorphism inferred from nucleotide variation at the Acph-1 gene region of Drosophila subobscura. Genetics. 1999;153:871–889. doi: 10.1093/genetics/153.2.871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-Sabate A, Aguadé M, Segarra C. Excess of nonsynonymous polymorphism at Acph-1 in different gene arrangements of Drosophila subobscura. Mol Biol Evol. 2003;20:1833–1843. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nei M. Molecular Evolutionary Genetics. Columbia University Press: New York; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Nobrega C, Khadem M, Aguadé M, Segarra C. Genetic exchange versus genetic differentiation in a medium-sized inversion of Drosophila: the A2/Ast arrangements of Drosophila subobscura. Mol Biol Evol. 2008;25:1534–1543. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochman H, Gerber AS, Hartl DL. Genetic applications of an inverse polymerase chain reaction. Genetics. 1988;120:621–623. doi: 10.1093/genetics/120.3.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta T. Evolutionary rate of cistrons and DNA divergence. J Mol Evol. 1972. pp. 150–157. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ohta T, Kimura M. Behavior of neutral mutants influenced by associated overdominant loci in finite populations. Genetics. 1971;69:247–260. doi: 10.1093/genetics/69.2.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez JA, Munte A, Rozas J, Segarra C, Aguadé M. Nucleotide polymorphism in the RpII215 gene region of the insular species Drosophila guanche: reduced efficacy of weak selection on synonymous variation. Mol Biol Evol. 2003;20:1867–1875. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popadic A, Popadic D, Anderson WW. Interchromosomal exchange of genetic information between gene arrangements on the third chromosome of Drosophila pseudoobscura. Mol Biol Evol. 1995;12:938–943. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell JR. Progress and Prospects in Evolutionary Biology: The Drosophila Model. Oxford University Press: New York; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Prevosti A, Ribo G, Serra L, Aguadé M, Balana J, Monclus M, et al. Colonization of America by Drosophila subobscura: experiment in natural populations that supports the adaptive role of chromosomal-inversion polymorphism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:5597–5600. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.15.5597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puig M, Caceres M, Ruiz A. Silencing of a gene adjacent to the breakpoint of a widespread Drosophila inversion by a transposon-induced antisense RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:9013–9018. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403090101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Soriano A, Ramos-Onsins SE, Rozas J, Calafell F, Navarro A. Statistical power analysis of neutrality tests under demographic expansions, contractions and bottlenecks with recombination. Genetics. 2008;179:555–567. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.083006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Onsins S, Aguadé M. Molecular evolution of the Cecropin multigene family in Drosophila. functional genes vs. pseudogenes. Genetics. 1998;150:157–171. doi: 10.1093/genetics/150.1.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Onsins SE, Rozas J. Statistical properties of new neutrality tests against population growth. Mol Biol Evol. 2002;19:2092–2100. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts PA.1976The genetics of chromosome aberrationIn: Ashburner M and Novitski E (eds).The Genetics and Biology of DrosophilaVol. 1a. Academic Press: London; 67–184. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers AR, Harpending H. Population growth makes waves in the distribution of pairwise genetic differences. Mol Biol Evol. 1992;9:552–569. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozas J, Aguadé M. Evidence of extensive genetic exchange in the rp49 region among polymorphic chromosome inversions in Drosophila subobscura. Genetics. 1990;126:417–426. doi: 10.1093/genetics/126.2.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozas J, Aguadé M. Gene conversion is involved in the transfer of genetic information between naturally occurring inversions of Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11517–11521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozas J, Gullaud M, Blandin G, Aguadé M. DNA variation at the rp49 gene region of Drosophila simulans: evolutionary inferences from an unusual haplotype structure. Genetics. 2001;158:1147–1155. doi: 10.1093/genetics/158.3.1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozas J, Segarra C, Ribo G, Aguadé M. Molecular population Genetics of the rp49 gene region in different chromosomal inversions of Drosophila subobscura. Genetics. 1999;151:189–202. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.1.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saiki RK, Gelfand DH, Stoffel S, Scharf SJ, Higuchi R, Horn GT, et al. Primer-directed enzymatic amplification of DNA with a thermostable DNA polymerase. Science. 1988;239:487–491. doi: 10.1126/science.2448875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Gracia A, Aguade M, Rozas J. Patterns of nucleotide polymorphism and divergence in the odorant-binding protein genes OS-E and OS-F: analysis in the melanogaster species subgroup of Drosophila. Genetics. 2003;165:1279–1288. doi: 10.1093/genetics/165.3.1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Gracia A, Rozas J. Unusual pattern of nucleotide sequence variation at the OS-E and OS-F genomic regions of Drosophila simulans. Genetics. 2007;175:1923–1935. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.068015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Gracia A, Rozas J. Divergent evolution and molecular adaptation in the Drosophila odorant-binding protein family: inferences from sequence variation at the OS-E and OS-F genes. BMC Evol Biol. 2008;8:323. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Gracia A, Vieira FG, Rozas J. Molecular evolution of the major chemosensory gene families in insects. Heredity. 2009;103:208–216. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2009.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer SW, Goetting-Minesky MP, Kovacevic M, Peoples JR, Graybill JL, Miller JM, et al. Evolutionary genomics of inversions in Drosophila pseudoobscura: evidence for epistasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8319–8324. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1432900100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer SW, Anderson WW. Mechanisms of genetic exchange within the chromosomal inversions of Drosophila pseudoobscura. Genetics. 2005;171:1729–1739. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.041947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segarra C, Aguadé M. Molecular organization of the X chromosome in different species of the obscura group of Drosophila. Genetics. 1992;130:513–521. doi: 10.1093/genetics/130.3.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons MP, Ochoterena H. Gaps as characters in sequence-based phylogenetic analyses. Syst Biol. 2000;49:369–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajima F. Statistical method for testing the neutral mutation hypothesis by DNA polymorphism. Genetics. 1989;123:585–595. doi: 10.1093/genetics/123.3.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira FG, Sánchez-Gracia A, Rozas J. Comparative genomic analysis of the odorant-binding protein family in 12 Drosophila genomes: purifying selection and birth-and-death evolution. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R235. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-11-r235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir BS. Genetic Data Analysis II. Sinauer Associates: Sunderland; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1586–1591. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Nielsen R. Codon-substitution models for detecting molecular adaptation at individual sites along specific lineages. Mol Biol Evol. 2002;19:908–917. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Nielsen R, Goldman N, Pedersen AM. Codon-substitution models for heterogeneous selection pressure at amino acid sites. Genetics. 2000;155:431–449. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.1.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Nielsen R, Yang Z. Evaluation of an improved branch-site likelihood method for detecting positive selection at the molecular level. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:2472–2479. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.