Abstract

The “chromogenome” is defined as the structural and functional status of the genome at any given moment within a eukaryotic cell. This article focuses on recently uncovered relationships between histone chaperones, the posttranslational acetylation of histones, and modulation of the chromogenome. We emphasize those chaperones that function in a replication-independent manner, and for which three-dimensional structural information has been obtained. The emerging links between histone acetylation and chaperone function in both yeast and higher metazoans are discussed, including the importance of nucleosome-free regions. We close by posing many questions pertaining to how the coupled action of histone chaperones and acetylation influences chromogenome structure and function.

Eukaryotic genomes are assembled into chromatin fibers, which are composed of a polymer of nucleosomes and a host of associated non-histone proteins, e.g., architectural proteins, transcription factors, co-activators/repressors, polymerases. Each nucleosome consists of 147 bp of genomic DNA wrapped around an octamer of the four core histones, H2A, H2B, H3, and H4 (Luger et al., 1997; Luger and Richmond, 1998a; Luger and Richmond, 1998b). Spaced arrays of nucleosomes make up the next level of DNA organization in the nucleus. Nucleosomal arrays bound to non-histone proteins are termed chromatin fibers. Nucleosomal arrays and chromatin fibers help condense genomic DNA into chromosomes and serve as barriers to regulatory proteins that must access the condensed DNA sequence.

The properties of nucleosomes, nucleosomal arrays, and chromatin fibers can be modulated in a variety of ways. A prominent example is histone post-translational modifications; the side chains of specific histone residues can be modified in response to specific biological signals, thereby altering function. This article focuses on histone acetylation. This modification can decondense chromatin fibers (Robinson et al., 2008; Shogren-Knaak et al., 2006; Tse et al., 1998; Annunziato and Hansen, 2000), subtly alter nucleosome structure (Bresnick et al., 1991; Oliva et al., 1990; Wang and Hayes, 2008; Widlund et al., 2000), and create binding platforms for specific proteins (Mujtaba et al., 2007). Acetylation also is strongly correlated with transcriptional activation (Shahbazian and Grunstein, 2007). Other post-translational modifications such as histone methylation have equally diverse and potent biological effects (Delcuve et al., 2009; Campos and Reinberg, 2009).

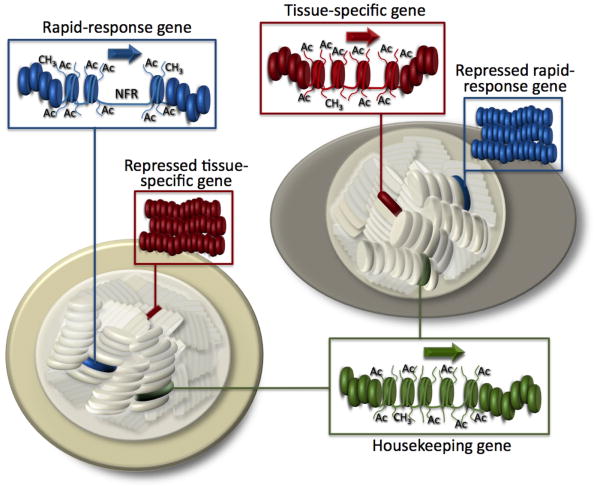

Here we coin the term “chromogenome” to refer to the structural and functional status of the genome at any given moment within a eukaryotic cell. Key features of the chromogenome include the unique 1-, 2-, and 3-dimensional organization of the nucleosomal arrays and chromatin fibers within chromosomes, and the pattern of both inherited modifications (DNA methylation) and rapidly turning over histone post-translational modifications (Fig. 1). At specific promoters and enhancers within a chromogenome, the histone modifications are dynamic and nucleosomes are mobilized via disassembly, reassembly, and sliding. This fluidity of the chromogenome enables rapid changes in gene expression patterns in response to external physiological signals. Changes in chromogenome fluidity are conferred through the action of histone modifying enzymes (Delcuve et al., 2009; Fischle et al., 2003; Peterson and Laniel, 2004), ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling machines (Flaus and Owen-Hughes, 2004), and histone chaperones (Akey and Luger, 2003; Eitoku et al., 2008; Loyola and Almouzni, 2004; Park and Luger, 2008; Polo and Almouzni, 2007). Collectively, these chromatin-modifying proteins promote the unique chromogenome architecture responsible for the transcriptional phenotype of the cell. For example, a resting T-cell and an activated T-cell possess the same genetic information, yet their chromogenomes significantly differ at many key sites that cause functional differences at the cellular level (see Fig. 1). A similar example is a yeast cell in two different metabolic states, e.g., growing on glucose versus galactose (Campbell et al., 2008; Gao et al., 2003). The histone modifications required for these rapid and reversible changes in gene expression, by definition, exclude their classification as “epigenetic” (Berger et al., 2009), as they do not necessarily produce heritable changes in chromatin structure. Therefore the term chromogenome provides us with the language to better describe the dynamic nature of the genomic landscape, and histone post-translational modifications can be considered “chromogenetic” marks.

Figure 1. A Schematic Model depicting the chromogenomes of two distinct cells.

Both cells express housekeeping genes (green), with similar chromatin structure and post-translational, or chromogenetic, modifications. Each cell also expresses specific genes that confer a unique tissue-specific phenotype (red) or response to an environmental stimulus (blue). Nucleosomal histones associated with the rapid-response gene undergo rapid and reversible acetylation, enabling an immediate response to specific stimuli. As such, the highly reversible nature of these chromatin changes are not considered epigenetic, as they are not transmitted to daughter cells.

Histone chaperone proteins are important components of the chromogenome. Chaperones are required to prevent the highly basic core histones from making improper interactions with DNA and other macromolecules prior to assembly into nucleosomes. Core histones are found in complexes with chaperone proteins in cell extracts made from yeast, fly, and vertebrates (reviewed in (Akey and Luger, 2003; Eitoku et al., 2008; Loyola and Almouzni, 2004; Park and Luger, 2008; Polo and Almouzni, 2007). In vivo, different chaperones are specific for the core histone pairs. For example, histones H3 and H4 form complexes with chromatin assembly factor 1 (Verreault et al., 1996), the HIRA/Hir proteins (Kaufman et al., 1998), and Asf1 (English et al., 2005). In contrast, H2A/H2B shows specificity for members of the nucleoplasmin and Nap1 families of chaperone proteins (Akey and Luger, 2003; Zlatanova et al., 2007). Through their ability to mediate both nucleosome assembly and disassembly, histone chaperones influence the structure of the chromatin milieu surrounding genes, and thus contribute a key layer of regulatory control to the chromogenome. Befitting their functional importance, numerous studies have established key roles for histone chaperones in processes that are heavily influenced by the chromogenome landscape, i.e., gene transcription, DNA repair, heterochromatin maintenance, and cell cycle control (reviewed in (De Koning et al., 2007; Eitoku et al., 2008; Rocha and Verreault, 2008)).

The Subunit of the Chromogenome: the Nucleosome

To understand histone chaperone function it is first important to point out several key properties of the nucleosome, the subunit of the chromogenome. The nucleosome is a large protein-DNA complex that is assembled in a stepwise fashion. Of the 147 bp of DNA bound to the nucleosome, the central ∼80 bp of DNA first interacts with the histone (H3-H4)2 tetramer, followed by the deposition of two histone H2A-H2B dimers onto the peripheral ∼2×30 bp of DNA. The histone (H3-H4)2 tetramer is a dimer of two H3-H4 dimers. The interface between the two histone H3-H4 dimers is mediated by numerous salt bridges and hydrogen bonds that are part of a four helix bundle, and hence the (H3-H4)2 tetramer is quite stable. The individual H2A-H2B dimers also are stable, but only very minor H2A-H2B dimer-dimer contacts are made within the nucleosome (Akey and Luger, 2003). Instead, the H2A-H2B dimers are stabilized through interaction with the arm domains of the (H3-H4)2 tetramer. Importantly, the interactions between the H2A-H2B dimers and the (H3-H4)2 tetramer within the nucleosome require the presence of DNA. Thus, enzymes that post-translationally modify histones, energy-dependent remodeling complexes, and histone chaperones all have the potential to modulate nucleosome stability in part by altering the H2A/H2B dimer-H3/H4 tetramer or histone octamer-DNA interactions.

Histone Chaperone Families are Structurally and Functionally Diverse

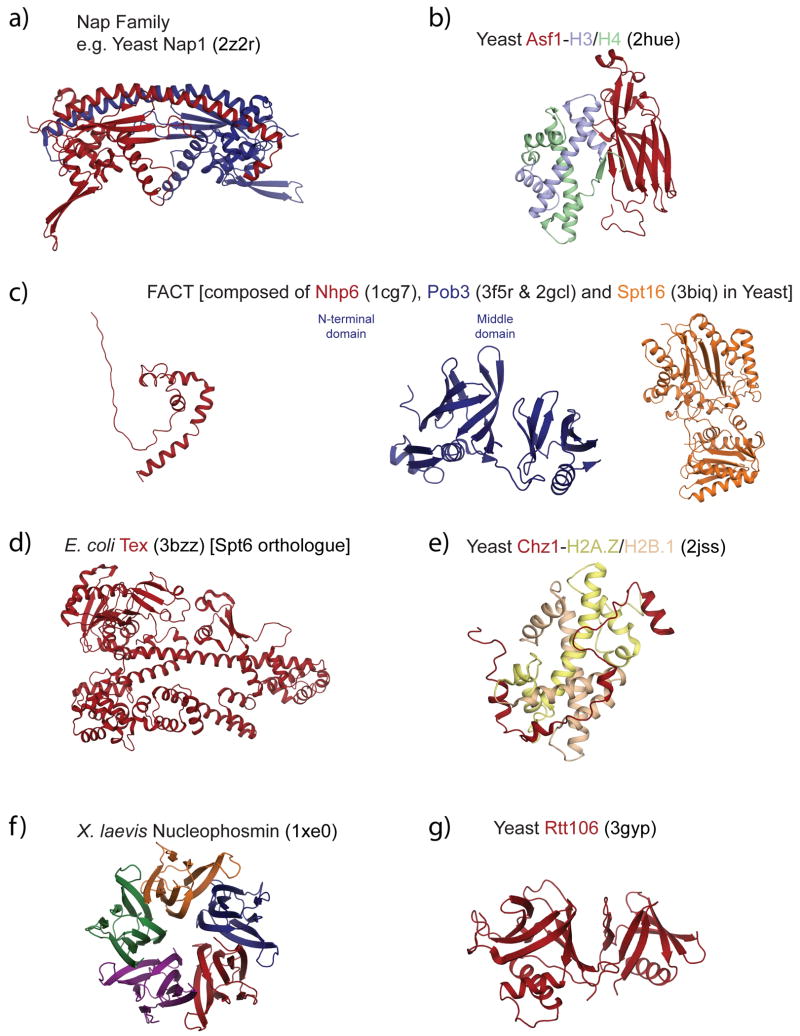

There are many different families of histone chaperones (reviewed in (Eitoku et al., 2008)). Here we discuss those histone chaperones whose structures have been solved (supplemental Table 1; Fig. 2) and that function to influence chromogenome structure and function outside of replication. The overarching theme of this section is that each of the seven families highlighted below has fundamentally different structural features despite having functional properties consistent with being a chaperone. This strongly suggests that there is unexpected diversity of both structure and function among the growing list of proteins labeled histone chaperones.

Figure 2. The different histone chaperone families have completely different tertiary and quaternary structures.

Structures are displayed in ribbon diagrams, using Pymol. Histones H2A, H2B, H3 and H4 are colored in pastel yellow, red, blue and green, respectively. Single chaperone subunits are colored in red, the second subunit in the Nap1 homodimer is colored in blue. Nucleophosmin is a pentamer of five identical subunits. Details and references are given in supplementary table 1.

Nap1 and related proteins

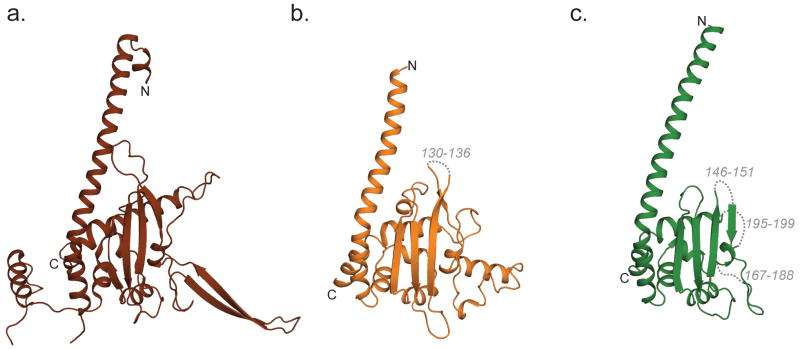

Nap1 is the defining member of a large class of histone chaperones whose representatives are found in all eukaryotes (Park and Luger, 2006a; Zlatanova et al., 2007). These members include Nap1, and the Nap-like proteins including yeast Vps75 and human SET proteins. Yeast Nap1 is a stable homodimer (Fig. 2a) that can further self-associate into large oligomers (McBryant and Peersen, 2004; Park et al., 2008a). The structures of yeast, trypanosome, and plasmodium Nap1, yeast Vps75, and human SET have been solved (Berndsen et al., 2008; Gill et al., 2009; Muto et al., 2007; Park and Luger, 2006b; Park et al., 2008b; Tang et al., 2008b). While the overall fold and distinctive tertiary structure is conserved between the Nap family members (Fig. 3), noticeable differences exist that presumably reflect differences in functional properties.

Figure 3. Structural comparison of Nap1 family members.

All Nap1 family members are obligatory dimers (as seen in Fig. 1a). For ease of comparison, only one chain is shown here. Yeast Nap1 (ScNap1) was submitted to Dali. Yeast Vps75 (ScVps75 and human Set (hsSet) were the two top hits. ScVps75: rmsd = 3.7, Z-score = 12.6, length of alignment = 181, no. res = 205, %id = 14. HsSet: rmsd = 2.5, Z-score = 14.8, length of alignment = 166, no. res = 167, %id = 25. a. ScNap1; Chain A (PDB 2Z2R Residues 82-365) b. ScVps75; Chain B (PDB 3DM7; Residues 12-222) c. hSET; Chain B (PDB 2E50; Residues 24-221)

Yeast has only two Nap1 family members (Nap1 and Vps75; Fig. 3a, b). In contrast, there are at least eight metazoan Nap1 homologues in the protein database. These include Nap1 (also called Nap1L1), Nap1-like 2-6 (Nap1L2-L6), SETα and SETβ (also called TAF-1/SET). Nap1, Nap1L2 and Nap1L4 are all conserved throughout metazoans. Nap1 binds histones H3/H4, H2A/H2B, and linker histone H1 with high affinity in vitro (Andrews et al., 2008), and assembles regularly spaced nucleosomes on circular plasmids (Fujii Nakata et al., 1992; Ito et al., 1996). Nap1-dependent nucleosome disassembly acts to regulate DNA accessibility during transcription in vitro (Levchenko and Jackson, 2004; Lorch et al., 2006; Okuwaki et al., 2005; Park et al., 2005; Sharma and Nyborg, 2008). Nap1 deletion can result in either increases or decreases in histone density (Andrews et al., 2010; Del Rosario and Pemberton, 2008; Walfridsson et al., 2007), depending on the location. Genome-wide expression profiling in S. cerevisiae shows that approximately 10% of genes are regulated by Nap1 (Ohkuni et al., 2003), revealing a potentially prominent role for Nap1 in establishing and regulating the chromogenome in that organism.

Mechanistically, recent in vitro and in vivo results indicate that Nap1 promotes nucleosome assembly through active disassembly of nonproductive histone-DNA interactions (Andrews et al., 2010). Using a rigorous thermodynamic approach, Nap1 was shown to prevent non-nucleosomal H2A-H2B-DNA interactions in vitro, thereby facilitating nucleosome formation. Predictions from in vitro experiments are in perfect accord with results obtained in vivo, where significantly enriched H2A and H2B levels (but not H3 levels) at endogenous genes in a nap1 deletion strain were observed (Andrews et al., 2010). This atypical H2A-H2B-enriched chromatin appears to present a lower barrier for binding of the transcription machinery as genes in the nap1 deletion strain are more permissive to transcriptional activation (Andrews et al., 2010). Although there are many other chaperones expressed in yeast cells, including the Nap1-family member Vps75, this increase in H2A-H2B accumulation is observed in a strain deleted for only NAP1. Thus, preventing non-productive H2A-H2B-DNA complexes is a Nap1-specific property in yeast.

In vivo studies in higher eukaryotes also suggest diverse roles for Nap1-like proteins in regulating the transcription of specific cellular and viral genes (e.g. (Ito et al., 2000; Rehtanz et al., 2004; Rogner et al., 2000; Vardabasso et al., 2008; Wang and Frappier, 2009). Nap1 has been widely associated with gene activation, primarily through its interaction or association with transcriptional activators and coactivators (Attia et al., 2007; Del Rosario and Pemberton, 2008; El Gazzar et al., 2009; Ito et al., 2000; Rehtanz et al., 2004; Sharma and Nyborg, 2008; Shikama et al., 2000; Vardabasso et al., 2008; Walfridsson et al., 2005; Wang and Frappier, 2009). Nap1L2 has been proposed to function in nucleosome assembly (Rodriguez et al., 2000), and deletion of mouse Nap1L2 leads to embryonic lethality, likely through extensive changes in the chromogenome that alter transcriptional profiles in neuronal precursor cells (Attia et al., 2007). This tissue-specific Nap1 protein regulates neuronal differentiation by affecting the histone acetylation patterns of an estimated 3.6% of the expressed genes (Attia et al., 2007). In vitro, Nap1L2 interacts preferentially with acetylated forms of H3/H4 (Attia et al., 2007). The role of Nap1L4 (also termed Nap2) is less well studied (Rodriguez et al., 2000). Human Nap1L3 appears to be expressed in the brain (Shen et al., 2001), and combines structural and functional features of Nap1 and SET.

SET (Fig. 3c) has been suggested to function in multiple critical cellular pathways, including transcription (Gamble et al., 2005; Matsumoto et al., 1995; Miyamoto et al., 2003; Suzuki et al., 2003), replication (Matsumoto et al., 1995), and apoptosis (Fan et al., 2003). The precise function of SET in transcription, however, is controversial, as it has been shown to inhibit transcription by physically blocking acetylation of the histone tails (Seo et al., 2001), but also acts as an activator of transcription on chromatin templates (Gamble et al., 2005). SET can substitute for Nap1 in chromatin assembly and disassembly reactions in vitro (Kawase et al., 1996; Okuwaki et al., 2005), which is not surprising given their structural similarity.

Vps75 is likely the yeast orthologue of SET based on its similar overall structure (Berndsen et al., 2008; Park et al., 2008b; Tang et al., 2008b). Vps75 binds histones in vitro and assembles them into nucleosomes, but unlike Nap1 and SET, it is not efficient at promoting nucleosome disassembly in vitro (Park et al., 2008b; Selth and Svejstrup, 2007). Of particular note (see below), Vps75 forms a complex with and stimulates the activity of the histone acetyltransferase (HAT), Rtt109 (Berndsen et al., 2008; Fillingham et al., 2008; Han et al., 2007; Park et al., 2008b). In vivo, Vps75 also has Rtt109-independent functions in transcription-associated histone exchange that are non-redundant with Nap1 functions (Selth and Svejstrup, 2007; Selth et al., 2009).

Taken together, despite having highly related structures, the Nap1 family members seem to display a wide variety of specific functions related to transcription and modulating the chromogenome.

Asf1

The structure of the yeast Asf1 core domain has been determined alone (Daganzo et al., 2003) and in complex with H3/H4 (Antczak et al., 2006; English et al., 2006; Natsume et al., 2007) (Fig. 2b). H3/H4 bind Asf1 as a heterodimer, not as the heterotetramer present in the nucleosome. Moreover, the H3/H4 heterodimer binds to Asf1 in a way that precludes H3-H4 tetramer formation. This suggests that Asf1-mediated nucleosome assembly occurs through H3/H4 dimer intermediates, for which there is also significant biochemical evidence (English et al., 2005; Tagami et al., 2004)

In yeast, Asf1 impacts the chromogenome by affecting the chromatin structure of specific promoters, the classic example being the PHO5 locus. Deletion of Asf1 results in a failure to evict promoter nucleosomes and create a nucleosome-free region at the PHO5 gene, and a concomitant failure to activate gene expression under inducing conditions (Adkins et al., 2004; Adkins and Tyler, 2006; Korber et al., 2006). Further, Asf1 appears to be involved in global nucleosome disassembly in yeast in vivo (Adkins et al., 2004). Asf1 is also involved in the replication-independent assembly of nucleosomes (Tagami et al., 2004). This pathway involves deposition of histone chaperone-bound H3.3/H4 dimers to form tetramer-DNA complexes followed by deposition of H2A/H2B to complete nucleosome formation. Replication-independent nucleosome assembly occurs outside of S phase and is associated with gene expression (Ahmad and Henikoff, 2002). Asf1 in Drosophila functionally cooperates with the BRM chromatin remodeler (Moshkin et al., 2002), and is also involved in developmental gene expression of NOTCH target genes (Goodfellow et al., 2007; Moshkin et al., 2009). In terms of in vitro mechanism of action, far less is known about Asf1 affects chromogenome structure compared to Nap1. This is generally true for the chaperones discussed below as well.

FACT

FACT is a transcriptional coactivator that has histone chaperone activity (reviewed in (Formosa, 2008; Reinberg and Sims, 2006)). FACT in humans is a heterodimer of Spt16 and Ssrp1, where Spt16 is the histone binding subunit of the complex. In yeast, a third protein, Nhp6 (an HMGB family member) provides DNA and nucleosome binding abilities; this gene is fused to the C-terminus of the Ssrp1 gene in higher organisms. The structure of the N-terminal domain of S. cerevisiae and S. pombe Spt16 reveals distinct N- and C-terminal lobes that collectively show homology to an ancestral aminopeptidase fold (Stuwe et al., 2008; VanDemark et al., 2008) (Fig. 2c). The N-terminal domain binds histones both the H3/H4 core and histone tails (Stuwe et al., 2008) while the Spt16 C-terminal domain is thought to be involved in H2A/H2B dissociation during transcription elongation, consistent with a primary role for Spt16 in the histone chaperone functions of the FACT complex. The structure of Nhp6 in complex with DNA is also known (Masse et al., 2002).

FACT facilitates the exchange of core histones during transcriptional elongation in yeast. Specifically, FACT is thought to bind nucleosomes and cause dissociation of H2A-H2B dimers, thereby relieving a chromatin structure that is repressive to transcriptional elongation (Belotserkovskaya et al., 2003). A role for FACT in promoting a reversible transition between two nucleosomal forms (both of which have a full complement of histones) also has been proposed (Xin et al., 2009). Functionally, FACT may aid in the reassembly of nucleosomes after passage of the transcriptional elongation machinery (Belotserkovskaya et al., 2003; Formosa et al., 2002). Given that most metazoan genes are lengthy, FACT has the potential to have a major effect on the chromogenome acting through its ability to assist RNA Polymerase II (RNAP II) in passing through hundreds to thousands of nucleosomes during transcriptional elongation.

Spt6

As do many other histone chaperones, Spt6 can participate in both nucleosome assembly and disassembly. The Tex protein is the apparent bacterial ortholog of Spt6, and has an elongated helical tertiary structure (Johnson et al., 2008) unlike that of any of the other histone chaperones (Fig. 2d). Spt6 helps repress specific genes (Clark-Adams and Winston, 1987), presumably by facilitating nucleosome assembly on promoters and open reading frames (Adkins and Tyler, 2006; Kaplan et al., 2003). Spt6 co-localizes with active RNA polymerase II and has been shown to be involved in transcriptional elongation (reviewed in (Eitoku et al., 2008); (Roth et al., 2001). Thus, Spt6 also may facilitate transcriptional elongation by disassembly of nucleosomes in front of the polymerase and reassembly of nucleosomes behind the polymerase.

Chz1

Chz1 is a yeast-specific histone chaperone that cooperates with the ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complex Swr1 to facilitate the exchange of normal H2A-H2B dimers in the nucleosome for variant H2A.Z-H2B dimers ((Luk et al., 2007), and references therein). H2A.Z-H2B dimers are found in nucleosomes that flank active promoters in yeast, suggesting a link between Chz1 and transcription. Somewhat surprisingly given their structural dissimilarities, at least some of the functions of Chz1 can be replaced by Nap1 and FACT (Luk et al., 2007). Chz1 is notable in that it lacks detectable secondary structure as a free protein. The histone binding core of yeast Chz1 has been determined in complex with its histone partners (Fig. 2e) (Zhou et al., 2008); however, the structure does not explain the apparent preference of Chz1 for the histone variant H2A.Z/H2B over H2A/H2B. After binding histones Chz1 remains a mostly extended polypeptide chain with short α-helices at each end. As with the Asf1-H3-H4 co-complex, the histones in the Chz1 complex have a similar structure as found in the nucleosome.

Nucleophosmin family and Rtt106

The structures of two functionally less well understood chaperones have been determined (Fig. 2g, f), further emphasizing the structural diversity among the histone chaperone families.

Histone Chaperones and Acetylation

Acetylation

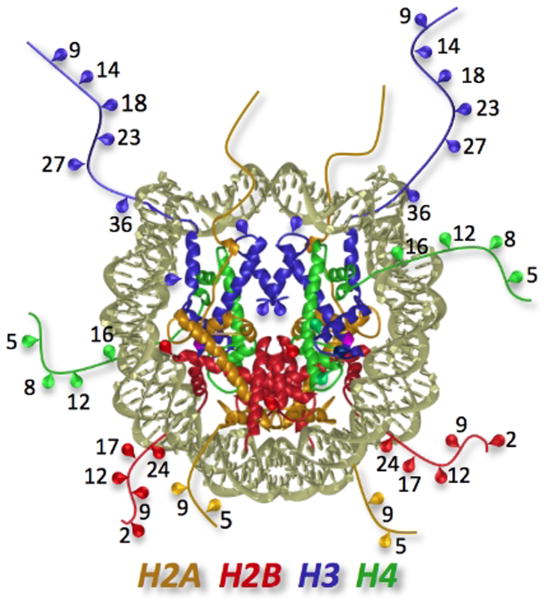

Post-translational modification of histones is one of the defining features of the chromogenome. The many different types of post-translational modifications that can occur on each core histone act to both positively and negatively regulate gene expression (Roth et al., 2001). The acetylation of lysine residues is the best-characterized histone modification associated with gene activation (Shahbazian and Grunstein, 2007). Highly conserved lysine residues present on all four core histones serve as the targets of acetylation. Most of these specific acetylation sites associated with gene activation are found on the amino terminal histone “tails”, e.g., H4K16, H3K9, H3K14 (Fig. 4), while some sites are present on the surface of the structured portion of H3 in the nucleosome core, e.g., H3K56 (Roth et al., 2001). State-of-the-art genome-wide approaches in yeast and multicellular organisms have established elevated levels of acetylated H3 and H4 within the proximal promoter and enhancer regions of active genes (Heintzman et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2005; Millar and Grunstein, 2006; Pokholok et al., 2005; Roh et al., 2006; Roh et al., 2005; Roh et al., 2007; Wang and Hayes, 2008).

Figure 4. Acetylation sites are located on the histone tails and on the structured regions.

The structure of the nucleosome (1aoi) is displayed in ribbon format; histone tails have been extended to their approximate length since they are largely disordered in the crystal structure. Dots indicate lysine residues known to be acetylated.

The molecular mechanism through which histone acetylation influences gene activation depends on the specific combination of modified sites on the surrounding nucleosomes. For example, some acetylated lysine residues serve as binding sites for transcriptional regulatory proteins that carry bromodomains (Mujtaba et al., 2007), providing a mechanism for the binding of bromodomain-bearing proteins to target genes. There is also significant evidence that histone acetylation impacts the physical properties of chromatin. Lysine charge neutralization achieved through histone tail acetylation reduces inter-nucleosomal interactions, resulting in unfolding of the chromatin fiber (Robinson et al., 2008; Shogren-Knaak et al., 2006; Tse et al., 1998; Annunziato and Hansen, 2000). Once unfolded, acetylation weakens the histone tail-DNA interactions, but has little effect on the physical stability of the nucleosome (Bresnick et al., 1991; Oliva et al., 1990; Wang and Hayes, 2008; Widlund et al., 2000). It should be noted though that the various assays employed to measure nucleosome stability measure different interactions within the nucleosome. Finally, as will be discussed below, histone acetylation appears to influence the functions of various chaperones. Taken together, acetylation of specific histone lysine residues can promote gene activation via at least four mechanisms: 1) binding of bromodomain-containing regulatory proteins, 2) relaxation of the chromatin fiber, 3) diminished histone tail-DNA contacts, possibly resulting in increased DNA accessibility, and as will be discussed below, 4) promotion of nucleosome disassembly by histone chaperones.

Connections between Histone Chaperones and Acetylation in Yeast

In yeast, there is emerging evidence linking histone acetylation to histone chaperones. Acetylation is accomplished by histone acetyltransferases (HATs), which are classified into three main families based on sequence similarity: the GNAT, MYST, and p300/CBP families (Sterner and Berger, 2000). The GNAT (Gcn5-related N-acetyltransferases) family includes yeast Gcn5, and human Gcn5L and PCAF (Georgakopoulos and Thireos, 1992; Smith et al., 1998a; Wang et al., 1997), as well as yeast and human Elp3 (Li et al., 2005). Both Gcn5 and Elp3 are found in large multisubunit complexes in vivo. Gcn5 is a subunit of SAGA, a major transcription-related HAT complex that targets histone H3 lysine 9, 14 and 18 (Grant et al., 1999; Kuo et al., 2000), and the related complexes SLIK and ADA (Eberharter et al., 1999; Grant et al., 1997; Marcus et al., 1996; Pray-Grant et al., 2002; Syntichaki and Thireos, 1998; Wang et al., 1998). Elp3 is a subunit of Elongator, a HAT complex originally purified with elongating RNAPII (Otero et al., 1999). Importantly, Elongator disruptions (including ELP3) exacerbate deletions in ASF1 (Li et al., 2009) and FACT (Formosa et al., 2002), or are lethal with NAP1 deletions (Kong et al., 2005). Gcn5 activity is also linked to chaperone functions since mutations in ASF1 (Adkins et al., 2007), and FACT (Biswas et al., 2005; VanDemark et al., 2006), are lethal or a deletion in VPS75 (Fillingham et al., 2008) grows poorly when combined with a GCN5 deletion. In addition, mutations in Gcn5 and Nap1 produce similar changes in histone density at the genome-wide level (Walfridsson et al., 2007).

The MYST family is named after its four founding members: MOZ, Ybf2, Sas2, and TIP60 (for review see (Pillus, 2008)). Esa1 is another MYST family member (Clarke et al., 1999; Smith et al., 1998b). Esa1 is the catalytic subunit of the NuA4 HAT complex (Allard et al., 1999; Galarneau et al., 2000)), and is also found in a subcomplex called Picollo, which is responsible for untargeted acetylation (Boudreault et al., 2003). NuA4 participates in chromatin remodeling and activation of transcription (Nourani et al., 2004), and interacts both physically and genetically with Vps75 and FACT (Formosa et al., 2002; Lin et al., 2008), and genetically with Asf1 (Lin et al., 2008; Mitchell et al., 2008)

The p300/CBP family of HATs is defined by unique structural attributes (Liu et al., 2008), and includes yeast Rtt109 (Bazan, 2008; Tang et al., 2008a). The Nap1 family member Vps75 interacts with Rtt109 in vitro and enhances Rtt109 enzymatic activity (Berndsen et al., 2008; Fillingham et al., 2008; Han et al., 2007; Park et al., 2008b). In vivo, Rtt109 physically interacts with both Vps75 and Asf1 (Collins et al., 2007; Han et al., 2007; Jessulat et al., 2008; Krogan et al., 2006; Tsubota et al., 2007). The Asf1/Rtt109 interaction may lead to acetylation of nucleosomes on H3-K56, whereas Vps75/Rtt109 interactions may acetylate nucleosomes on H3-K9, both of which are modifications associated with transcription. The Asf/Rtt109 interaction plays a role in elongation of RNAPII by increasing the efficiency of transcription (Varv et al., 2010).

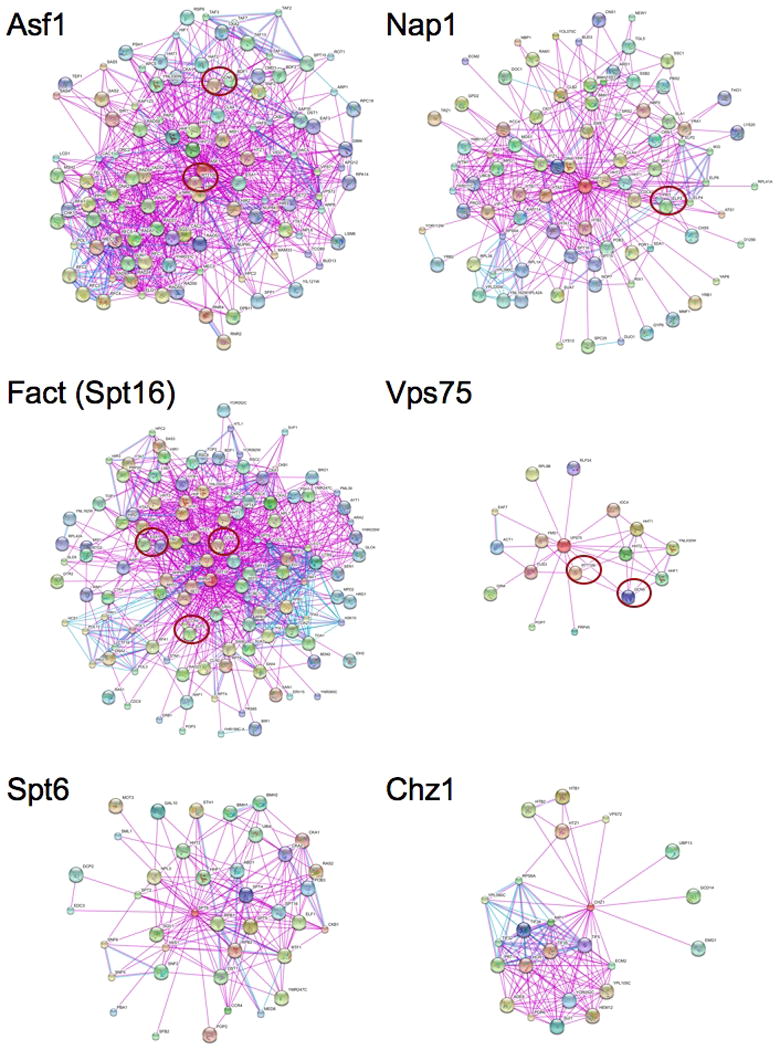

Protein-protein interaction maps for S. cerevisiae histone chaperones further support the view that some chaperones and HATs are functionally linked (Fig. 5) (Jensen et al., 2009). In these maps there are both unique protein-protein interactions observed for each histone chaperone, and shared interactions between chaperones and other proteins. Together, the summed interactions provide a distinctive signature for each chaperone (Supplemental Table 2). This analysis indicates that all families show physical interactions with the core histones, as expected. Rather strikingly, several of the chaperones interact with HATs commonly implicated in the control of gene expression. For example, Nap1 interacts with Elp3; Vps75 with Rtt109 and Gcn5; Asf1 with Rtt109, Gcn5 and Esa1; and FACT with Gcn5, Esa1 and Elp3. As such, these diagrams imply that HAT-mediated histone acetylation and histone chaperone function are functionally linked through specific protein-protein interaction networks. Interestingly, two of the chaperones (Spt6, Chz1) do not interact with any of the HATs, suggesting that there are both acetylation-dependent and -independent families of chaperones. In summary, in vitro biochemical and in vivo genetic experiments both have documented connections between specific histone chaperones and specific HATs in yeast.

Figure 5. Protein-protein interaction maps for several histone chaperones.

The red oval indicates the approximate location of HATs within the maps. Generated using evidence view, with a required confidence of 0.50; custom limit 150. http://string.embl.de. Different line colors represent the types of evidence for the association.

Connections between Chaperones and Histone Acetylation in Higher Metazoans

In multicellular organisms the evidence for physical and functional relationships between histone chaperones and HATs is beginning to emerge, and important parallels with fungal systems have been identified. The histone chaperones and HATs in higher eukaryotes share significant structural conservation with their yeast counterparts. For example, the acetyltransferase domains of the metazoan HATs p300/CBP are structurally homologous with yeast Rtt109 (Tang et al., 2008a). p300/CBP are large (∼300 kDa), homologous coactivators that mediate gene expression throughout Metazoa. The association of p300 at promoters and enhancers throughout the chromogenome is considered a “signature” of transcriptionally active gene loci (Visel et al., 2009). In vitro, p300 recruitment to chromatin-assembled promoter templates correlates with histone acetylation and strong transcriptional activation (An et al., 2002; An and Roeder, 2003; Geiger et al., 2008; Georges et al., 2003; Georges et al., 2002; Ito et al., 2000; Sharma and Nyborg, 2008). Moreover, metazoan Nap1 binds the CH3 domain of p300/CBP (Asahara et al., 2002; Shikama et al., 2000), suggesting a functional relationship between this HAT/chaperone pair as well. This conclusion is further supported by in vitro studies demonstrating an association between Nap1 and p300 HAT activity in modulating nucleosome structure and transcriptional activation (Asahara et al., 2002; Ito et al., 2000; Sharma and Nyborg, 2008; Shikama et al., 2000). Interestingly, metazoan Asf1 functions together with p300/CBP to acetylate the chromogenome on H3-K56 (Das et al., 2009), analogous to the yeast Asf1/Rtt109 complex. Thus, throughout eukaryotes there is growing evidence for evolutionary conservation of specific chaperone/HAT pairs that function in concert for the purposes of modulation of the chromogenome fluidity and transcriptional output.

Chaperones, Acetylation, and Nucleosome-free Regions

Reports of nucleosome-free promoter regions associated with active gene promoters and enhancers have increased dramatically in recent years (Boyle et al., 2008; Erkina et al., 2008; Fu et al., 2008; Heintzman et al., 2007; Mavrich et al., 2008; Petesch and Lis, 2008; Schones et al., 2008; Zhao et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2008). Nucleosomes are intrinsically repressive to transcription, as they restrict the access of regulatory proteins to promoter DNA and thus prevent the assembly of preinitiation complexes. Hence, in some contexts the promoter regions of active genes must exist in a state of reduced nucleosome occupancy to enable assembly of the transcription machinery. As such, mechanisms must exist for the dynamic disassembly of nucleosomes from promoter DNA during the step-wise transition from a silent gene to a transcriptionally active gene. Nucleosome-free regions will locally enhance the access of regulatory proteins to genomic DNA sequences. Nucleosome-free regions can be generated through the evolution of DNA sequences that intrinsically disfavor nucleosome formation [Segal, 2006 #2440; Zhang, 2009 #2479], or through protein-mediated mechanism(s) that promote nucleosome disassembly at the appropriate time. Nucleosome-free regions disrupt the regular spacing of nucleosomal arrays, and destabilize the higher order condensed structures of nucleosomal arrays and chromatin fibers (Hansen, 2002), both of which increase accessibility of specific regions of the chromogenome.

Evidence documenting the existence of nucleosome-free regions has come from analyses of nucleosome positioning at specific genes, as well as high-throughput nucleosome occupancy studies that identified a strong correlation between nucleosome-free promoter regions and active genes (Boyle et al., 2008; Erkina et al., 2008; Fu et al., 2008; Heintzman et al., 2007; Mavrich et al., 2008; Petesch and Lis, 2008; Schones et al., 2008; Schones and Zhao, 2008; Zhao et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2008). Such regions have been documented throughout eukaryotes, from budding and fission yeast to humans (Boeger et al., 2003; Boyle et al., 2008; Fu et al., 2008; Heintzman et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2004; Mavrich et al., 2008; Petesch and Lis, 2008; Schones et al., 2008; Workman, 2006; Wang et al., 2008) Importantly, one of the defining characteristics of nucleosome free regions within the chromogenome is the presence of flanking hyperacetylated nucleosomes (Durrin et al., 1991; Erkina et al., 2008; Fukuda et al., 2006; Heintzman et al., 2007; Roh et al., 2005; Zhao et al., 2005). Moreover, histone hyperacetylation appears to precede the formation of nucleosome-free regions at the promoters of active genes (Erkina and Erkine, 2006; Zhao et al., 2005), suggesting a causal relationship between histone acetylation and formation of nucleosome-free regions during gene activation. These changes in the chromogenome landscape must be finely controlled and involve other factors besides acetylation, as nucleosomes immediately flanking the nucleosome-free regions remain hyperacetylated but stably associated with the DNA (Durrin et al., 1991; Erkina and Erkine, 2006; Erkina et al., 2008; Fukuda et al., 2006; Govind et al., 2007; Heintzman et al., 2007; Reinke and Horz, 2003; Roh et al., 2005; Zhao et al., 2005). These observations suggest that specific nucleosomes can in some way be “primed” for acetylation-coupled disassembly, perhaps through the function of histone chaperones.

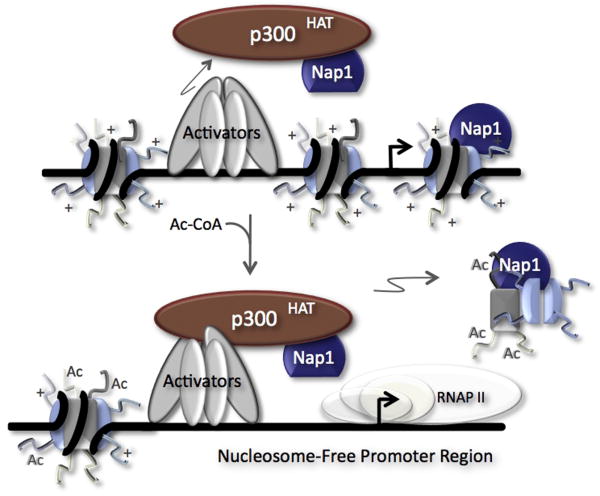

Recent experiments have used a highly purified in vitro model promoter system to demonstrate coupled acetylation- and chaperone-dependent formation of nucleosome-free regions (i.e., histone eviction) on the promoter DNA (Sharma and Nyborg, 2008). An early study showed that Nap1, p300, and Ac-CoA were required for the transfer of H2A-H2B dimers from pre-assembled nucleosomal arrays to Nap1 (Ito et al., 2000), suggesting that histone acetylation by p300 may play a role in Nap1-dependent dimer transfer. In the model promoter system experiments (Sharma and Nyborg, 2008), DNA-bound activators first recruited p300 to the chromatin-assembled promoter template. The addition of Nap1, Ac-CoA and acceptor DNA subsequently resulted in loss of the promoter nucleosomes. Importantly, Nap1 and the HAT activity of p300 were directly required for the eviction of histone octamers from the promoter DNA. Moreover, histone acetylation-coupled nucleosome disassembly did not require ATP, indicating that chromatin remodeling complexes were not involved in the process of nucleosome disassembly (Sharma and Nyborg, 2008). These results provide the strongest in vitro evidence to date linking nucleosome acetylation with histone chaperone function, and specifically suggest a coupled role for histone acetylation and histone chaperone function during generation of nucleosome-free regions and gene activation. A model depicting the role of histone acetylation and Nap1 in promoter nucleosome dynamics is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Model of Acetylation-Dependent Nucleosome Eviction by Nap1.

The binding of transcriptional activators (Tax/CREB) is required for the recruitment of the coactivator and HAT, p300, to the chromatin-assembled model promoter. In the presence of acetyl CoA (Ac-CoA), p300 acetylates the histone H3 tail; a requirement for Nap1-mediated disassembly of nucleosome octamers. Nucleosome eviction exposes the promoter DNA for the binding of the preinitiation complex.

Concluding Perspectives and Questions

Understanding the structure and function of the chromogenome has increased dramatically over the past decade. The atomic structures of canonical, variant, and specifically modified nucleosomes have been determined at very high resolution. The in vitro conformational dynamics of model nucleosomal arrays and chromatin fibers are known, and much has been learned about the complex pattern of nucleosome-nucleosome interactions that mediate fiber condensation. Whole genome analyses of nucleosome positions in vivo, and detailed maps of the location of posttranslational modifications at single nucleosome resolution throughout entire genomes, are now available. With these and many other advances comes the realization that the chromogenome is very dynamic, e.g., the chromatin in the vicinity of genes that are being transcribed is in a state of partial assembly and disassembly to permit transient access of the nuclear machinery while maintaining the chromogenome in a reasonably compacted state. Histone chaperones and histone acetylation appear to be intimately involved in these events. In this regard, while once thought of simply as histone storage proteins, it is now evident that a major function of histone chaperones is to alter the landscape of the chromogenome for specific functional purposes.

Despite the progress made during the last decade toward understanding histone chaperones and post-translational modifications, many key questions remain unanswered:

Why are there so many different classes of chaperones? Have all the classes and isoforms been discovered? Each class has a fundamentally different tertiary structure, seemingly suggesting different specific functions. Yet there appears to be a great deal of redundancy between classes, at least in yeast.

What answers will be obtained when the rigorous mechanistic in vitro analysis of Andrews et al., (2010) is applied to the other histone chaperones? Do all of the histone chaperones affect nucleosome structure by a similar molecular mechanism?

Are certain specifically modified nucleosomes more easily disassembled/assembled by histone chaperones? If so, which specific post-translational modifications are linked to modulation by which specific histone chaperones?

How widespread is the interaction of the different chaperones with the different HATs, and how does the direct physical interaction of histone chaperones with HATs affect enzymatic activity and specificity at promoters and enhancers?

For each histone chaperone class, which specific biological functions are partitioned between which specific family members? Why are some chaperones found at certain genes and others located at others?

At the level of higher order structure, how do the nucleosome-nucleosome interactions that stabilize condensed chromatin affect chaperone function? How do histone chaperones function on unfolded nucleosomal arrays versus condensed chromatin fibers, i.e., what is the affect of linker histone H1 and other chromatin architectural proteins on histone chaperone function? Presumably, histone chaperones act more efficiently in a decondensed environment and histone acetylation helps facilitate this state.

These are just a few of the many questions that highlight just how much is unknown about histone chaperones and acetylation, despite the widespread recent attention chaperone field has received. In view of the emerging data, we anticipate much progress toward answering these questions and gaining a better understanding of the molecular connections between histone post-translational modifications, histone chaperone function, and the fluidity of the chromogenome.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Sheena d'Arcy for preparing figures 1 and 2 and for helpful discussions, and Heather Szerlong for critically reading the manuscript.

Funding: Contract grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health

Contract grant numbers: 2 R01 GM045916, 2 R01 CA055035, 1R01 GM067777, 2 R01 GM061909

Literature Cited

- Adkins MW, Howar SR, Tyler JK. Chromatin Disassembly Mediated by the Histone Chaperone Asf1 Is Essential for Transcriptional Activation of the Yeast PHO5 and PHO8 Genes. Mol Cell. 2004;14(5):657–666. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adkins MW, Tyler JK. Transcriptional activators are dispensable for transcription in the absence of Spt6-mediated chromatin reassembly of promoter regions. Mol Cell. 2006;21(3):405–416. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adkins MW, Williams SK, Linger J, Tyler JK. Chromatin disassembly from the PHO5 promoter is essential for the recruitment of the general transcription machinery and coactivators. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27(18):6372–6382. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00981-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad K, Henikoff S. The histone variant H3.3 marks active chromatin by replication- independent nucleosome assembly. Mol Cell. 2002;9(6):1191–1200. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00542-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akey CW, Luger K. Histone chaperones and nucleosome assembly. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2003;13(1):6–14. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(03)00002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allard S, Utley RT, Savard J, Clarke A, Grant P, Brandl CJ, Pillus L, Workman JL, Cote J. NuA4, an essential transcription adaptor/histone H4 acetyltransferase complex containing Esa1p and the ATM-related cofactor Tra1p. EMBO J. 1999;18(18):5108–5119. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.18.5108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An W, Palhan VB, Karymov MA, Leuba SH, Roeder RG. Selective requirements for histone H3 and H4 N termini in p300- dependent transcriptional activation from chromatin. Mol Cell. 2002;9(4):811–821. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00497-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An W, Roeder RG. Direct association of p300 with unmodified H3 and H4 N termini modulates p300-dependent acetylation and transcription of nucleosomal templates. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(3):1504–1510. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209355200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews AJ, Downing G, Brown K, Park YJ, Luger K. A thermodynamic model for Nap1-histone interactions. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(47):32412–32418. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805918200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews AJ, Xu C, Zevin A, Stargell LA, Luger K. The histone chaperone Nap1 promotes nucleosome assembly by eliminating non-nucleosomal histone DNA interactions. Molecular Cell. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.037. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annunziato AT, Hansen JC. Role of histone acetylation in the assembly and modulation of chromatin structures. Gene Expr. 2000;9(1-2):37–61. doi: 10.3727/000000001783992687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antczak AJ, Tsubota T, Kaufman PD, Berger JM. Structure of the yeast histone H3-ASF1 interaction: implications for chaperone mechanism, species-specific interactions, and epigenetics. BMC Struct Biol. 2006;6:26. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-6-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asahara H, Tartare-Deckert S, Nakagawa T, Ikehara T, Hirose F, Hunter T, Ito T, Montminy M. Dual roles of p300 in chromatin assembly and transcriptional activation in cooperation with nucleosome assembly protein 1 in vitro. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22(9):2974–2983. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.9.2974-2983.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attia M, Rachez C, De Pauw A, Avner P, Rogner UC. Nap1l2 promotes histone acetylation activity during neuronal differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27(17):6093–6102. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00789-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazan JF. An old HAT in human p300/CBP and yeast Rtt109. Cell Cycle. 2008;7(12):1884–1886. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.12.6074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belotserkovskaya R, Oh S, Bondarenko VA, Orphanides G, Studitsky VM, Reinberg D. FACT facilitates transcription-dependent nucleosome alteration. Science. 2003;301(5636):1090–1093. doi: 10.1126/science.1085703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger SL, Kouzarides T, Shiekhattar R, Shilatifard A. An operational definition of epigenetics. Genes Dev. 2009;23(7):781–783. doi: 10.1101/gad.1787609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berndsen CE, Tsubota T, Lindner SE, Lee S, Holton JM, Kaufman PD, Keck JL, Denu JM. Molecular functions of the histone acetyltransferase chaperone complex Rtt109-Vps75. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008 doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas D, Yu Y, Prall M, Formosa T, Stillman DJ. The yeast FACT complex has a role in transcriptional initiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(14):5812–5822. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.14.5812-5822.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeger H, Griesenbeck J, Strattan JS, Kornberg RD. Nucleosomes unfold completely at a transcriptionally active promoter. Mol Cell. 2003;11(6):1587–1598. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00231-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudreault AA, Cronier D, Selleck W, Lacoste N, Utley RT, Allard S, Savard J, Lane WS, Tan S, Cote J. Yeast enhancer of polycomb defines global Esa1-dependent acetylation of chromatin. Genes Dev. 2003;17(11):1415–1428. doi: 10.1101/gad.1056603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle AP, Davis S, Shulha HP, Meltzer P, Margulies EH, Weng Z, Furey TS, Crawford GE. High-resolution mapping and characterization of open chromatin across the genome. Cell. 2008;132(2):311–322. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bresnick EH, John S, Hager GL. Histone hyperacetylation does not alter the positioning or stability of phased nucleosomes on the mouse mammary tumor virus long terminal repeat. Biochemistry. 1991;30(14):3490–3497. doi: 10.1021/bi00228a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell RN, Leverentz MK, Ryan LA, Reece RJ. Metabolic control of transcription: paradigms and lessons from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem J. 2008;414(2):177–187. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos EI, Reinberg D. Histones: annotating chromatin. Annu Rev Genet. 2009;43:559–599. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.032608.103928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark-Adams CD, Winston F. The SPT6 gene is essential for growth and is required for delta-mediated transcription in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7(2):679–686. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.2.679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke AS, Lowell JE, Jacobson SJ, Pillus L. Esa1p is an essential histone acetyltransferase required for cell cycle progression. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19(4):2515–2526. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.4.2515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins SR, Kemmeren P, Zhao XC, Greenblatt JF, Spencer F, Holstege FC, Weissman JS, Krogan NJ. Toward a comprehensive atlas of the physical interactome of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6(3):439–450. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600381-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das C, Lucia MS, Hansen KC, Tyler JK. CBP/p300-mediated acetylation of histone H3 on lysine 56. Nature. 2009 doi: 10.1038/nature07861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Koning L, Corpet A, Haber JE, Almouzni G. Histone chaperones: an escort network regulating histone traffic. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14(11):997–1007. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Rosario BC, Pemberton LF. Nap1 links transcription elongation, chromatin assembly and mRNP biogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2008 doi: 10.1128/MCB.02136-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delcuve GP, Rastegar M, Davie JR. Epigenetic control. J Cell Physiol. 2009;219(2):243–250. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll R, Hudson A, Jackson SP. Yeast Rtt109 promotes genome stability by acetylating histone H3 on lysine 56. Science. 2007;315(5812):649–652. doi: 10.1126/science.1135862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durrin LK, Mann RK, Kayne PS, Grunstein M. Yeast histone H4 N-terminal sequence is required for promoter activation in vivo. Cell. 1991;65(6):1023–1031. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90554-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberharter A, Sterner DE, Schieltz D, Hassan A, Yates JR, 3rd, Berger SL, Workman JL. The ADA complex is a distinct histone acetyltransferase complex in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19(10):6621–6631. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.10.6621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eitoku M, Sato L, Senda T, Horikoshi M. Histone chaperones: 30 years from isolation to elucidation of the mechanisms of nucleosome assembly and disassembly. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:414–444. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7305-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Gazzar M, Liu T, Yoza BK, McCall CE. Dynamic and selective nucleosome repositioning during endotoxin tolerance. J Biol Chem. 2009;285(2):1259–1271. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.067330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English CM, Adkins MW, Carson JJ, Churchill ME, Tyler JK. Structural basis for the histone chaperone activity of Asf1. Cell. 2006;127(3):495–508. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English CM, Maluf NK, Tripet B, Churchill ME, Tyler JK. ASF1 binds to a heterodimer of histones H3 and H4: a two-step mechanism for the assembly of the H3-H4 heterotetramer on DNA. Biochemistry. 2005;44(42):13673–13682. doi: 10.1021/bi051333h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erkina TY, Erkine AM. Displacement of histones at promoters of Saccharomyces cerevisiae heat shock genes is differentially associated with histone H3 acetylation. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26(20):7587–7600. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00666-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erkina TY, Tschetter PA, Erkine AM. Different requirements of the SWI/SNF complex for robust nucleosome displacement at promoters of heat shock factor and Msn2- and Msn4-regulated heat shock genes. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28(4):1207–1217. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01069-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Z, Beresford PJ, Oh DY, Zhang D, Lieberman J. Tumor suppressor NM23-H1 is a granzyme A-activated DNase during CTL-mediated apoptosis, and the nucleosome assembly protein SET is its inhibitor. Cell. 2003;112(5):659–672. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00150-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillingham J, Recht J, Silva AC, Suter B, Emili A, Stagljar I, Krogan NJ, Allis CD, Keogh MC, Greenblatt JF. Chaperone Control of the Activity and Specificity of the Histone H3 Acetyltransferase Rtt109. Mol Cell Biol. 2008 doi: 10.1128/MCB.00182-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischle W, Wang Y, Allis CD. Histone and chromatin cross-talk. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15(2):172–183. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00013-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaus A, Owen-Hughes T. Mechanisms for ATP-dependent chromatin remodelling: farewell to the tuna-can octamer? Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2004;14(2):165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Formosa T. FACT and the reorganized nucleosome. Mol Biosyst. 2008;4(11):1085–1093. doi: 10.1039/b812136b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Formosa T, Ruone S, Adams MD, Olsen AE, Eriksson P, Yu Y, Rhoades AR, Kaufman PD, Stillman DJ. Defects in SPT16 or POB3 (yFACT) in Saccharomyces cerevisiae cause dependence on the Hir/Hpc pathway: polymerase passage may degrade chromatin structure. Genetics. 2002;162(4):1557–1571. doi: 10.1093/genetics/162.4.1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y, Sinha M, Peterson CL, Weng Z. The insulator binding protein CTCF positions 20 nucleosomes around its binding sites across the human genome. PLoS Genet. 2008;4(7):e1000138. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii Nakata T, Ishimi Y, Okuda A, Kikuchi A. Functional analysis of nucleosome assembly protein, NAP-1. The negatively charged COOH-terminal region is not necessary for the intrinsic assembly activity. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(29):20980–20986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda H, Sano N, Muto S, Horikoshi M. Simple histone acetylation plays a complex role in the regulation of gene expression. Brief Funct Genomic Proteomic. 2006;5(3):190–208. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/ell032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galarneau L, Nourani A, Boudreault AA, Zhang Y, Heliot L, Allard S, Savard J, Lane WS, Stillman DJ, Cote J. Multiple links between the NuA4 histone acetyltransferase complex and epigenetic control of transcription. Mol Cell. 2000;5(6):927–937. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80258-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamble MJ, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Freedman LP, Fisher RP. The histone chaperone TAF-I/SET/INHAT is required for transcription in vitro of chromatin templates. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(2):797–807. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.2.797-807.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J, Opiteck GJ, Friedrichs MS, Dongre AR, Hefta SA. Changes in the protein expression of yeast as a function of carbon source. J Proteome Res. 2003;2(6):643–649. doi: 10.1021/pr034038x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger TR, Sharma N, Kim YM, Nyborg JK. The human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 tax protein confers CBP/p300 recruitment and transcriptional activation properties to phosphorylated CREB. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28(4):1383–1392. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01657-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgakopoulos T, Thireos G. Two distinct yeast transcriptional activators require the function of the GCN5 protein to promote normal levels of transcription. EMBO J. 1992;11(11):4145–4152. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05507.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georges SA, Giebler HA, Cole PA, Luger K, Laybourn PJ, Nyborg JK. Tax recruitment of CBP/p300, via the KIX domain, reveals a potent requirement for acetyltransferase activity that is chromatin dependent and histone tail independent. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(10):3392–3404. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.10.3392-3404.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georges SA, Kraus WL, Luger K, Nyborg JK, Laybourn PJ. p300-Mediated Tax Transactivation from Recombinant Chromatin: Histone Tail Deletion Mimics Coactivator Function. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22(1):127–137. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.1.127-137.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill J, Yogavel M, Kumar A, Belrhali H, Jain SK, Rug M, Brown M, Maier AG, Sharma A. Crystal structure of malaria parasite nucleosome assembly protein: distinct modes of protein localization and histone recognition. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(15):10076–10087. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808633200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow H, Krejci A, Moshkin Y, Verrijzer CP, Karch F, Bray SJ. Gene-specific targeting of the histone chaperone asf1 to mediate silencing. Dev Cell. 2007;13(4):593–600. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govind CK, Zhang F, Qiu H, Hofmeyer K, Hinnebusch AG. Gcn5 promotes acetylation, eviction, and methylation of nucleosomes in transcribed coding regions. Mol Cell. 2007;25(1):31–42. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant PA, Duggan L, Cote J, Roberts SM, Brownell JE, Candau R, Ohba R, Owen-Hughes T, Allis CD, Winston F, Berger SL, Workman JL. Yeast Gcn5 functions in two multisubunit complexes to acetylate nucleosomal histones: characterization of an Ada complex and the SAGA (Spt/Ada) complex. Genes Dev. 1997;11(13):1640–1650. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.13.1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant PA, Eberharter A, John S, Cook RG, Turner BM, Workman JL. Expanded lysine acetylation specificity of Gcn5 in native complexes. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(9):5895–5900. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.9.5895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J, Zhou H, Horazdovsky B, Zhang K, Xu RM, Zhang Z. Rtt109 acetylates histone H3 lysine 56 and functions in DNA replication. Science. 2007;315(5812):653–655. doi: 10.1126/science.1133234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen JC. CONFORMATIONAL DYNAMICS OF THE CHROMATIN FIBER IN SOLUTION: Determinants, Mechanisms, and Functions. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2002;31:361–392. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.31.101101.140858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heintzman ND, Stuart RK, Hon G, Fu Y, Ching CW, Hawkins RD, Barrera LO, Van Calcar S, Qu C, Ching KA, Wang W, Weng Z, Green RD, Crawford GE, Ren B. Distinct and predictive chromatin signatures of transcriptional promoters and enhancers in the human genome. Nat Genet. 2007;39(3):311–318. doi: 10.1038/ng1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T, Bulger M, Kobayashi R, Kadonaga JT. Drosophila NAP-1 is a core histone chaperone that functions in ATP-facilitated assembly of regularly spaced nucleosomal arrays. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16(6):3112–3124. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.6.3112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T, Ikehara T, Nakagawa T, Kraus WL, Muramatsu M. p300-mediated acetylation facilitates the transfer of histone H2A-H2B dimers from nucleosomes to a histone chaperone. Genes Dev. 2000;14(15):1899–1907. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen LJ, Kuhn M, Stark M, Chaffron S, Creevey C, Muller J, Doerks T, Julien P, Roth A, Simonovic M, Bork P, von Mering C. STRING 8--a global view on proteins and their functional interactions in 630 organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Database issue):D412–416. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessulat M, Alamgir M, Salsali H, Greenblatt J, Xu J, Golshani A. Interacting proteins Rtt109 and Vps75 affect the efficiency of non-homologous end-joining in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2008;469(2):157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SJ, Close D, Robinson H, Vallet-Gely I, Dove SL, Hill CP. Crystal structure and RNA binding of the Tex protein from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Mol Biol. 2008;377(5):1460–1473. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.01.096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan CD, Laprade L, Winston F. Transcription elongation factors repress transcription initiation from cryptic sites. Science. 2003;301(5636):1096–1099. doi: 10.1126/science.1087374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman PD, Cohen JL, Osley MA. Hir Proteins Are Required for Position-Dependent Gene Silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae in the Absence of Chromatin Assembly Factor I. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4793–4806. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.8.4793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawase H, Okuwaki M, Miyaji M, Ohba R, Handa H, Ishimi Y, Fujii-Nakata T, Kikuchi A, Nagata K. NAP-I is a functional homologue of TAF-I that is required for replication and transcription of the adenovirus genome in a chromatin-like structure. Genes Cells. 1996;1(12):1045–1056. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1996.d01-223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong SE, Kobor MS, Krogan NJ, Somesh BP, Sogaard TM, Greenblatt JF, Svejstrup JQ. Interaction of Fcp1 phosphatase with elongating RNA polymerase II holoenzyme, enzymatic mechanism of action, and genetic interaction with elongator. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(6):4299–4306. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411071200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korber P, Barbaric S, Luckenbach T, Schmid A, Schermer UJ, Blaschke D, Horz W. The histone chaperone Asf1 increases the rate of histone eviction at the yeast PHO5 and PHO8 promoters. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(9):5539–5545. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513340200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogan NJ, Cagney G, Yu H, Zhong G, Guo X, Ignatchenko A, Li J, Pu S, Datta N, Tikuisis AP, Punna T, Peregrin-Alvarez JM, Shales M, Zhang X, Davey M, Robinson MD, Paccanaro A, Bray JE, Sheung A, Beattie B, Richards DP, Canadien V, Lalev A, Mena F, Wong P, Starostine A, Canete MM, Vlasblom J, Wu S, Orsi C, Collins SR, Chandran S, Haw R, Rilstone JJ, Gandi K, Thompson NJ, Musso G, St Onge P, Ghanny S, Lam MH, Butland G, Altaf-Ul AM, Kanaya S, Shilatifard A, O'Shea E, Weissman JS, Ingles CJ, Hughes TR, Parkinson J, Gerstein M, Wodak SJ, Emili A, Greenblatt JF. Global landscape of protein complexes in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature. 2006;440(7084):637–643. doi: 10.1038/nature04670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo MH, vom Baur E, Struhl K, Allis CD. Gcn4 activator targets Gcn5 histone acetyltransferase to specific promoters independently of transcription. Mol Cell. 2000;6(6):1309–1320. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CK, Shibata Y, Rao B, Strahl BD, Lieb JD. Evidence for nucleosome depletion at active regulatory regions genome-wide. Nat Genet. 2004;36(8):900–905. doi: 10.1038/ng1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levchenko V, Jackson V. Histone release during transcription: NAP1 forms a complex with H2A and H2B and facilitates a topologically dependent release of H3 and H4 from the nucleosome. Biochemistry. 2004;43(9):2359–2372. doi: 10.1021/bi035737q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Lu J, Han Q, Zhang G, Huang B. The Elp3 subunit of human Elongator complex is functionally similar to its counterpart in yeast. Mol Genet Genomics. 2005;273(3):264–272. doi: 10.1007/s00438-005-1120-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Fazly AM, Zhou H, Huang S, Zhang Z, Stillman B. The elongator complex interacts with PCNA and modulates transcriptional silencing and sensitivity to DNA damage agents. PLoS Genet. 2009;5(10):e1000684. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin YY, Qi Y, Lu JY, Pan X, Yuan DS, Zhao Y, Bader JS, Boeke JD. A comprehensive synthetic genetic interaction network governing yeast histone acetylation and deacetylation. Genes Dev. 2008;22(15):2062–2074. doi: 10.1101/gad.1679508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CL, Kaplan T, Kim M, Buratowski S, Schreiber SL, Friedman N, Rando OJ. Single-nucleosome mapping of histone modifications in S. cerevisiae. PLoS Biol. 2005;3(10):e328. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Wang L, Zhao K, Thompson PR, Hwang Y, Marmorstein R, Cole PA. The structural basis of protein acetylation by the p300/CBP transcriptional coactivator. Nature. 2008;451(7180):846–850. doi: 10.1038/nature06546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorch Y, Maier-Davis B, Kornberg RD. Chromatin remodeling by nucleosome disassembly in vitro. PNAS. 2006;103(9):3090–3093. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511050103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loyola A, Almouzni G. Histone chaperones, a supporting role in the limelight. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1677(1-3):3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2003.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luger K, Maeder AW, Richmond RK, Sargent DF, Richmond TJ. Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 Å resolution. Nature. 1997;389:251–259. doi: 10.1038/38444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luger K, Richmond TJ. DNA binding within the nucleosome core. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 1998a;8:33–40. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(98)80007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luger K, Richmond TJ. The histone tails of the nucleosome. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1998b;8(2):140–146. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(98)80134-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luk E, Vu ND, Patteson K, Mizuguchi G, Wu WH, Ranjan A, Backus J, Sen S, Lewis M, Bai Y, Wu C. Chz1, a Nuclear Chaperone for Histone H2AZ. Mol Cell. 2007;25(3):357–368. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus GA, Horiuchi J, Silverman N, Guarente L. ADA5/SPT20 links the ADA and SPT genes, which are involved in yeast transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16(6):3197–3205. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.6.3197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masse JE, Wong B, Yen YM, Allain FH, Johnson RC, Feigon J. The S. cerevisiae architectural HMGB protein NHP6A complexed with DNA: DNA and protein conformational changes upon binding. J Mol Biol. 2002;323(2):263–284. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00938-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto K, Okuwaki M, Kawase H, Handa H, Hanaoka F, Nagata K. Stimulation of DNA transcription by the replication factor from the adenovirus genome in a chromatin-like structure. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(16):9645–9650. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.16.9645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavrich TN, Jiang C, Ioshikhes IP, Li X, Venters BJ, Zanton SJ, Tomsho LP, Qi J, Glaser RL, Schuster SC, Gilmour DS, Albert I, Pugh BF. Nucleosome organization in the Drosophila genome. Nature. 2008;453(7193):358–362. doi: 10.1038/nature06929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBryant SJ, Peersen OB. Self-Association of the Yeast Nucleosome Assembly Protein 1. Biochemistry. 2004;43(32):10592–10599. doi: 10.1021/bi035881b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar CB, Grunstein M. Genome-wide patterns of histone modifications in yeast. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7(9):657–666. doi: 10.1038/nrm1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell L, Lambert JP, Gerdes M, Al-Madhoun AS, Skerjanc IS, Figeys D, Baetz K. Functional dissection of the NuA4 histone acetyltransferase reveals its role as a genetic hub and that Eaf1 is essential for complex integrity. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28(7):2244–2256. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01653-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto S, Suzuki T, Muto S, Aizawa K, Kimura A, Mizuno Y, Nagino T, Imai Y, Adachi N, Horikoshi M, Nagai R. Positive and negative regulation of the cardiovascular transcription factor KLF5 by p300 and the oncogenic regulator SET through interaction and acetylation on the DNA-binding domain. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(23):8528–8541. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.23.8528-8541.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moshkin YM, Armstrong JA, Maeda RK, Tamkun JW, Verrijzer P, Kennison JA, Karch F. Histone chaperone ASF1 cooperates with the Brahma chromatin-remodelling machinery. Genes Dev. 2002;16(20):2621–2626. doi: 10.1101/gad.231202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moshkin YM, Kan TW, Goodfellow H, Bezstarosti K, Maeda RK, Pilyugin M, Karch F, Bray SJ, Demmers JA, Verrijzer CP. Histone chaperones ASF1 and NAP1 differentially modulate removal of active histone marks by LID-RPD3 complexes during NOTCH silencing. Mol Cell. 2009;35(6):782–793. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mujtaba S, Zeng L, Zhou MM. Structure and acetyl-lysine recognition of the bromodomain. Oncogene. 2007;26(37):5521–5527. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muto S, Senda M, Akai Y, Sato L, Suzuki T, Nagai R, Senda T, Horikoshi M. Relationship between the structure of SET/TAF-Ibeta/INHAT and its histone chaperone activity. PNAS. 2007;104(11):4285–4290. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603762104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natsume R, Eitoku M, Akai Y, Sano N, Horikoshi M, Senda T. Structure and function of the histone chaperone CIA/ASF1 complexed with histones H3 and H4. Nature. 2007;446(7113):338–341. doi: 10.1038/nature05613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nourani A, Utley RT, Allard S, Cote J. Recruitment of the NuA4 complex poises the PHO5 promoter for chromatin remodeling and activation. EMBO J. 2004;23(13):2597–2607. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkuni K, Shirahige K, Kikuchi A. Genome-wide expression analysis of NAP1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;306(1):5–9. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00907-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuwaki M, Kato K, Shimahara H, Tate S, Nagata K. Assembly and disassembly of nucleosome core particles containing histone variants by human nucleosome assembly protein I. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(23):10639–10651. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.23.10639-10651.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliva R, Bazett-Jones DP, Locklear L, Dixon GH. Histone hyperacetylation can induce unfolding of the nucleosome core particle. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18(9):2739–2747. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.9.2739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otero G, Fellows J, Li Y, de Bizemont T, Dirac AM, Gustafsson CM, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Svejstrup JQ. Elongator, a multisubunit component of a novel RNA polymerase II holoenzyme for transcriptional elongation. Mol Cell. 1999;3(1):109–118. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80179-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park YJ, Chodaparambil JV, Bao Y, McBryant SJ, Luger K. Nucleosome assembly protein 1 exchanges histone H2A-H2B dimers and assists nucleosome sliding. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(3):1817–1825. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411347200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park YJ, Luger K. Structure and function of nucleosome assembly proteins. Biochem Cell Biol. 2006a;84(4):549–558. doi: 10.1139/o06-088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park YJ, Luger K. The structure of nucleosome assembly protein 1. PNAS. 2006b;103(5):1248–1253. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508002103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park YJ, Luger K. Histone chaperones in nucleosome eviction and histone exchange. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park YJ, McBryant SJ, Luger K. A beta-hairpin comprising the nuclear localization sequence sustains the self-associated states of Nucleosome Assembly Protein 1. JMB. 2008a;375:1076–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park YJ, Sudhoff KB, Andrews AJ, Stargell LA, Luger K. Histone chaperone specificity in Rtt109 activation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008b doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson CL, Laniel MA. Histones and histone modifications. Curr Biol. 2004;14(14):R546–551. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petesch SJ, Lis JT. Rapid, transcription-independent loss of nucleosomes over a large chromatin domain at Hsp70 loci. Cell. 2008;134(1):74–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillus L. MYSTs mark chromatin for chromosomal functions. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20(3):326–333. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokholok DK, Harbison CT, Levine S, Cole M, Hannett NM, Lee TI, Bell GW, Walker K, Rolfe PA, Herbolsheimer E, Zeitlinger J, Lewitter F, Gifford DK, Young RA. Genome-wide map of nucleosome acetylation and methylation in yeast. Cell. 2005;122(4):517–527. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polo SE, Almouzni G. DNA damage leaves its mark on chromatin. Cell Cycle. 2007;6(19):2355–2359. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.19.4756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pray-Grant MG, Schieltz D, McMahon SJ, Wood JM, Kennedy EL, Cook RG, Workman JL, Yates JR, 3rd, Grant PA. The novel SLIK histone acetyltransferase complex functions in the yeast retrograde response pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22(24):8774–8786. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.24.8774-8786.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehtanz M, Schmidt HM, Warthorst U, Steger G. Direct interaction between nucleosome assembly protein 1 and the papillomavirus E2 proteins involved in activation of transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(5):2153–2168. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.5.2153-2168.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinberg D, Sims RJ., 3rd de FACTo nucleosome dynamics. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(33):23297–23301. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R600007200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinke H, Horz W. Histones are first hyperacetylated and then lose contact with the activated PHO5 promoter. Mol Cell. 2003;11(6):1599–1607. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00186-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson PJ, An W, Routh A, Martino F, Chapman L, Roeder RG, Rhodes D. 30 nm chromatin fibre decompaction requires both H4-K16 acetylation and linker histone eviction. J Mol Biol. 2008;381(4):816–825. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.04.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha W, Verreault A. Clothing up DNA for all seasons: Histone chaperones and nucleosome assembly pathways. FEBS Lett. 2008;582(14):1938–1949. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez P, Pelletier J, Price GB, Zannis-Hadjopoulos M. NAP-2: histone chaperone function and phosphorylation state through the cell cycle. J Mol Biol. 2000;298(2):225–238. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogner UC, Spyropoulos DD, Le Novere N, Changeux JP, Avner P. Control of neurulation by the nucleosome assembly protein-1-like 2. Nat Genet. 2000;25(4):431–435. doi: 10.1038/78124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roh TY, Cuddapah S, Cui K, Zhao K. The genomic landscape of histone modifications in human T cells. PNAS. 2006;103(43):15782–15787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607617103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roh TY, Cuddapah S, Zhao K. Active chromatin domains are defined by acetylation islands revealed by genome-wide mapping. Genes Dev. 2005;19(5):542–552. doi: 10.1101/gad.1272505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roh TY, Wei G, Farrell CM, Zhao K. Genome-wide prediction of conserved and nonconserved enhancers by histone acetylation patterns. Genome Res. 2007;17(1):74–81. doi: 10.1101/gr.5767907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth SY, Denu JM, Allis CD. Histone acetyltransferases. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;70:81–120. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schones DE, Cui K, Cuddapah S, Roh TY, Barski A, Wang Z, Wei G, Zhao K. Dynamic regulation of nucleosome positioning in the human genome. Cell. 2008;132(5):887–898. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schones DE, Zhao K. Genome-wide approaches to studying chromatin modifications. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9(3):179–191. doi: 10.1038/nrg2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selth L, Svejstrup JQ. Vps75, a new yeast member of the NAP histone chaperone family. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(17):12358–12362. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C700012200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selth LA, Lorch Y, Ocampo-Hafalla MT, Mitter R, Shales M, Krogan NJ, Kornberg RD, Svejstrup JQ. An rtt109-independent role for vps75 in transcription-associated nucleosome dynamics. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29(15):4220–4234. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01882-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo SB, McNamara P, Heo S, Turner A, Lane WS, Chakravarti D. Regulation of histone acetylation and transcription by INHAT, a human cellular complex containing the set oncoprotein. Cell. 2001;104(1):119–130. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00196-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahbazian MD, Grunstein M. Functions of site-specific histone acetylation and deacetylation. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:75–100. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.052705.162114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma N, Nyborg JK. The coactivators CBP/p300 and the histone chaperone NAP1 promote transcription-independent nucleosome eviction at the HTLV-1 promoter. PNAS. 2008;105(23):7959–7963. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800534105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen HH, Huang AM, Hoheisel J, Tsai SF. Identification and characterization of a SET/NAP protein encoded by a brain-specific gene, MB20. Genomics. 2001;71(1):21–33. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shikama N, Chan HM, Krstic-Demonacos M, Smith L, Lee CW, Cairns W, La Thangue NB. Functional interaction between nucleosome assembly proteins and p300/CREB-binding protein family coactivators. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20(23):8933–8943. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.23.8933-8943.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shogren-Knaak M, Ishii H, Sun JM, Pazin MJ, Davie JR, Peterson CL. Histone H4-K16 acetylation controls chromatin structure and protein interactions. Science. 2006;311(5762):844–847. doi: 10.1126/science.1124000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith ER, Belote JM, Schiltz RL, Yang XJ, Moore PA, Berger SL, Nakatani Y, Allis CD. Cloning of Drosophila GCN5: conserved features among metazoan GCN5 family members. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998a;26(12):2948–2954. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.12.2948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]