Go home and die.” Until recently, that advice constituted the extent of end-of-life care that patients with incurable diseases could expect in Rwanda. As in much of the developing world, palliative care was virtually nonexistent in the tiny Africa nation, condemning those with terminal illnesses to meet their end in isolation and pain.

Now, however, the country has committed to provide all Rwandans living with incurable illnesses, as well as their families and caregivers, with high-quality, affordable palliative care services to meet their physical, psychological, social and spiritual needs by 2020 — one of the first such policies in sub-Saharan Africa and the developing world.

But fulfilling this promise will require a paradigm shift in how the entire country approaches incurable illness to overhaul policies restricting opioid prescriptions and misconceptions about palliative care among medical professionals and the public.

“At the moment, morphine is still not readily available throughout the country, and there’s no one to guide Rwanda through all the procedures and regulatory processes that need to be gone through to quantify the amount of morphine needed, procure it and ensure the necessary safeguards are in place to make sure its not misused or abused,” says Christian Stengel, chief of the Rwanda-based HIV/AIDS clinical services program run by IntraHealth International, a public health nonprofit that delivers palliative care services and is assisting the roll out of the new policy. “There’s a lot of suffering and it’s not visible, all for want of drugs we take for granted in the developed world.”

Strong painkillers such as morphine are unavailable in more than 150 countries around the world, despite being on the World Health Organization’s list of essential medicines. The lack of availability is not because morphine is costly or difficult to acquire, but because developing nations such as Rwanda are so concerned about illicit use and the potential for addiction that they make it almost impossible for doctors to give it to patients.

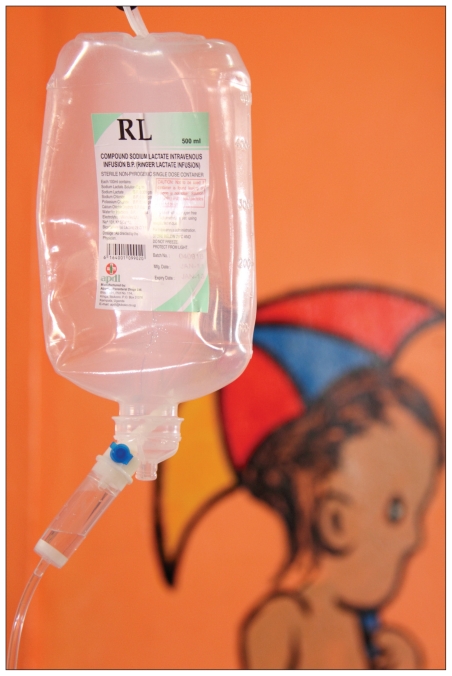

Without ready access to morphine, physicians at Rwanda’s first pediatric palliative care unit in Kibagabaga Hospital are often limited to providing counselling and basic primary care, such as hydration, to patients at end-of-life.

Image courtesy of Lauren Vogel

“Here, if you want to use morphine the procedure is so long even for one amp, and imagine if you need ten, so we try our best to relieve pain using codeine, ibuprofen, paracetamol, and when the severe pain comes we maximize the dose and give it every 30 minutes or 15 minutes, according to the half-life of the drug,” says Dr. Christian Ntizimira, director of Kibagabaga Hospital in Kigali and Rwanda’s only palliative care specialist.

More frequently, patients with incurable chronic diseases are just discharged by medical officers and told to go home because there is nothing to be done, he explains.

Meeting the pain relief needs of the population will require building a legal framework for narcotics from the ground up, says Minister of Health Dr. Agnes Binagwaho. “Who will get access to the narcotics, how do you report daily, weekly and monthly, and what happens when you’re missing narcotics? We need a system set in place to answer these questions so the health workers know what the expectation is, and everyone is protected.”

Just getting the drugs into Rwanda will be a big enough hurdle, involving quantifying how much morphine is needed and making a request to the International Narcotics Control Board, says Crystal Milligan, program manager of IntraHealth’s HIV/AIDS clinical services program in Rwanda. “That alone could take five months.”

Meanwhile, resistance has been dwindling among top officials following a field trip to a palliative care centre in neighbouring Uganda, where the government has relaxed laws to allow health workers greater access to opioids, Milligan says. “They could see for themselves that the system was working, despite not being strictly controlled.”

Education and training for government, health workers and the public will be another key component to achieving the country’s goals for end of life care, says Ntizimira, who opened Rwanda’s first pediatric palliative care unit at Kibagabaga in 2009 and first adult unit in 2010. “Ignorance of palliative care is still our weakness. Most of our staff was shocked to hear there was something to be done when there was nothing to do, and still most people think palliative care is just throwing people in a bed and waiting for them to die.”

A recent assessment conducted by IntraHealth found that only 50% of health workers in Rwanda could define palliative care accurately (www.intrahealth.org/page/rwanda-launches-national-palliative-care-policy).

Although some Rwandan health facilities have since incorporated palliative care services such as pain management and bereavement support, only recently have health centres started to designate specific palliative care units for patients in need of continuous support.

Many of these have sprung up in an “ad hoc way,” and without a national policy for palliative care the government could not ensure the regular supply of resources to these programs, nor could it guarantee standards for care, beginning with adequate pre-service and in-service training for health workers, Stengel says.

But whatever Rwandans may have lacked in awareness of palliative care, they’re now making up for it in enthusiasm for the new policy, says Milligan. “Everybody is really opening up to this idea, and the will is there at all levels of government and the health system to make this vision a reality.”