Abstract

Biopolymers are important substrates for heterotrophic bacteria in oligotrophic freshwater environments, but information on bacterial growth kinetics with biopolymers is scarce. The objective of this study was to characterize bacterial biopolymer utilization in these environments by assessing the growth kinetics of Flavobacterium johnsoniae strain A3, which is specialized in utilizing biopolymers at μg liter−1 levels. Growth of strain A3 with amylopectin, xyloglucan, gelatin, maltose, or fructose at 0 to 200 μg C liter−1 in tap water followed Monod or Teissier kinetics, whereas growth with laminarin followed Teissier kinetics. Classification of the specific affinity of strain A3 for the tested substrates resulted in the following affinity order: laminarin (7.9 × 10−2 liter·μg−1 of C·h−1) ≫ maltose > amylopectin ≈ gelatin ≈ xyloglucan > fructose (0.69 × 10−2 liter·μg−1 of C·h−1). No specific affinity could be determined for proline, but it appeared to be high. Extracellular degradation controlled growth with amylopectin, xyloglucan, or gelatin but not with laminarin, which could explain the higher affinity for laminarin. The main degradation products were oligosaccharides or oligopeptides, because only some individual monosaccharides and amino acids promoted growth. A higher yield and a lower ATP cell−1 level was achieved at ≤10 μg C liter−1 than at >10 μg C liter−1 with every substrate except gelatin. The high specific affinities of strain A3 for different biopolymers confirm that some representatives of the classes Cytophagia-Flavobacteria are highly adapted to growth with these compounds at μg liter−1 levels and support the hypothesis that Cytophagia-Flavobacteria play an important role in biopolymer degradation in (ultra)oligotrophic freshwater environments.

INTRODUCTION

High-molecular-weight (HMW) compounds such as polysaccharides and proteins originating from phytoplankton and bacteria usually occur at concentrations in the μg liter−1 range in oligotrophic aquatic environments (8, 34, 36, 38, 54). These biopolymers are considered to be important sources of carbon and energy for the heterotrophic bacteria in these ecosystems (2, 19). Low-molecular-weight (LMW) compounds (e.g., amino acids and monosaccharides) can diffuse directly into the cell, whereas biopolymers generally require extracellular enzymatic degradation and can be utilized only by bacteria that are capable of producing specific extracellular enzymes (4, 41).

Representatives of the classes Cytophagia-Flavobacteria seem to play a central role in the degradation of biopolymers in marine and freshwater environments (20, 24). A high abundance of Cytophagia-Flavobacteria was observed before and during phytoplankton blooms, when phytoplankton cells release large amounts of biopolymers (17, 18, 58). Furthermore, Cytophagia-Flavobacteria dominated the total bacterial community in culture-independent studies where natural bacterioplankton collected from aquatic environments was exposed to polymers such as starch, chitin, and bovine serum albumin (12, 39). Whole-genome sequencing of biopolymer-degrading bacterial isolates is increasingly applied to identify genes involved in biopolymer utilization processes (24, 32). These genome-based studies contribute to the enzymatic characterization of biopolymer-degrading bacterial strains. However, knowledge of nutritional versatility and growth kinetics is still essential for determining the role of these bacteria in the degradation of specific organic compounds in the environment. In contrast to the amount of kinetic data available in literature on oligotrophic aquatic bacteria consuming LMW compounds (9, 10, 27, 42, 48, 52), information on kinetic parameters of oligotrophic aquatic bacteria consuming HMW compounds is scarce.

In a recent study, Flavobacterium johnsoniae strain A3 was isolated from tap water supplemented with 100 μg of polysaccharide carbon liter−1 and a river water inoculum (40). Strain A3 is particularly proficient in the utilization of a diverse group of oligo- and polysaccharides at μg liter−1 levels in natural and treated water. Consequently, strain A3 may be a suitable model organism to study bacterial utilization of biopolymers in (ultra)oligotrophic freshwater environments. The genome of strain A3 has not been sequenced, but genome sequence information has recently been obtained for biopolymer-degrading F. johnsoniae strain UW101 and has allowed identification of proteins involved in biopolymer utilization (32). However, growth of strain UW101 with biopolymers has been demonstrated only at g liter−1 levels (7, 32). Thus, whether the genome sequence data of strain UW101 can be used to elucidate the biopolymer utilization systems of strain A3 depends on the ability of strain UW101 to utilize biopolymers at μg liter−1 levels.

The objective of our study was to characterize biopolymer utilization in oligotrophic freshwater environments by (i) assessing the kinetics and physiology of F. johnsoniae strain A3 during its growth with selected biopolymers at μg liter−1 levels in tap water and (ii) comparing the putative biopolymer utilization systems of F. johnsoniae strains A3 and UW101 and their abilities to utilize selected biopolymers at μg liter−1 levels.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Assessment of growth of F. johnsoniae strain A3 with peptides and proteins.

The ability of strain A3 to utilize peptides and proteins was assessed using a mixture of five oligopeptides (l-alanyl-l-alanine, l-alanyl-l-glutamine, glycyl-l-aspartate, l-glutamyl-l-glutamate, glycyl-l-leucyl-l-tyrosine), three polypeptides (poly-dl-alanine, poly-l-aspartate, poly-l-glutamate), and three proteins (casein, gelatin, lectin) at a concentration of 10 μg C liter−1 per compound in tap water (Table 1). Furthermore, the compounds included in the peptide-protein mixture and 14 amino acids were also tested as individual growth substrate for strain A3 at 10 μg C liter−1 (Table 1). Tap water (600 ml), prepared from anaerobic groundwater by aeration and rapid sand filtration and containing 1.9 mg dissolved organic carbon (DOC) liter−1, was collected and pasteurized for 30 min at 60°C in Pyrex glass Erlenmeyer flasks, which had been cleaned as previously described (44). The peptide-protein mixture and the individual compounds were added from solutions separately prepared in Milli-Q ultrapure water (Millipore) and heated for 30 min at 60°C. The tap water samples were supplemented with an excess of NO3− and PO43− and inoculated with 50 to 200 CFU ml−1 of strain A3 (50 to 150 μl of inoculum) precultured as previously described (40). All samples were prepared in duplicate flasks and incubated without shaking at 15°C until maximum colony counts (Nmax) were reached. Colony counts of strain A3 were determined daily or every other day using triplicate Lab-Lemco agar (LLA) streak-plates (Oxoid), which were incubated for 3 days at 25°C.

Table 1.

Amino acids, peptides, and proteins tested as growth substrates for strain A3 in tap water at 15°Ca

| Amino acid | Peptides and proteins |

|---|---|

| l-Alanine | l-Alanyl-l-alanine |

| l-Aspartate | l-Alanyl-l-glutamine |

| l-Glutamine | Glycyl-l-aspartate |

| l-Glutamate | l-Glutamyl-l-glutamate |

| Glycine | Glycyl-l-leucyl-l-tyrosine |

| l-Isoleucine | Poly-dl-alanineb |

| l-Leucine | Poly-l-aspartateb |

| l-Lysine | Poly-l-glutamateb |

| dl-Phenylalanine | Caseinc |

| l-Proline | Gelatinc |

| dl-Serine | Lectinc |

| l-Threonine | |

| l-Tyrosine | |

| l-Valine |

All compounds were tested individually; the peptides and proteins were also tested simultaneously as constituents of the peptide-and-protein mixture.

Molecular masses: poly-dl-alanine, 1 to 5 kDa; poly-l-aspartate, 5 to 15 kDa; and poly-l-glutamate, 3 to 15 kDa (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany).

Casein sodium salt from bovine milk; gelatin from bovine skin, type B; and lectin from Canavalia ensiformis (jack bean) (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany).

Estimation of growth kinetics and yields of F. johnsoniae strain A3.

Growth kinetics of strain A3 were determined with fructose, maltose, laminarin (from Laminaria digitata [Sigma-Aldrich, Germany]), xyloglucan (from tamarind seeds [Megazyme, Ireland]), amylopectin (from corn [Sigma-Aldrich, Germany]), gelatin, or proline as the growth substrate at 0, 1.0, 2.5, 5.0, 7.5, 10, 25, 50, 100, and 200 μg C liter−1 in tap water. In addition, the growth rate of strain A3 was determined with laminaribiose, laminaripentaose (both from Megazyme, Ireland), lectin, or casein at 5 μg C liter−1 and with alanine or glutamate at 100 μg C liter−1. Duplicate sample flasks were supplemented with substrate, inoculated with precultured strain A3, and incubated without shaking at 15°C until Nmax values were reached (40). The incubation period varied from 7 days (laminarin; 200 μg C liter−1) to 28 days (proline; 200 μg C liter−1). During the incubation period, the total ATP concentration was measured once or twice per day using a bioluminescence assay as described previously (53). When the maximum growth level was (about to be) reached based on the ATP concentration measured, the total direct cell (TDC) count was determined using acridine orange (22) and epifluorescence microscopy (DMRXA [Leica, The Netherlands]). Depending on the type of substrate and the added substrate concentration, the colony count was determined one to four times per day using the method described above. The mean plating efficiency and standard error of the mean were estimated from the ratios between Nmax and TDC for a total of 53 samples. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to test whether the 53 Nmax/TDC ratios were normally distributed (α level of significance = 0.05). Subsequently, the 95% confidence interval of the mean plating efficiency was calculated to determine with 95% certainty whether the mean plating efficiency was significantly different from 100%. The validity of using batch cultures for determining the growth kinetics of strain A3 is shown in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material.

The yield Y (CFU μg−1 of C) of strain A3 with each of the tested substrates was calculated from the linear relationship between the Nmax value of strain A3 and substrate concentration. The growth rate V (h−1) of strain A3 during the exponential growth phase at the various substrate concentrations was calculated using the following equation:

| (1) |

where N2 and N1 are the colony counts at time points t2 and t1. The relationship between the growth rate of strain A3 and the substrate concentration was modeled according to Monod kinetics or Teissier kinetics. The Monod model (33) can be written as follows:

| (2) |

and the Teissier model (43) can be written as follows:

| (3) |

In equations 2 and 3, V and Vmax are the observed and maximum growth rates (h−1) and S is the substrate concentration (μg C liter−1). In each of the seven experiments conducted to determine the growth kinetics of strain A3 (i.e., one experiment per substrate), limited growth of strain A3 with the indigenous compounds in the blank (i.e., tap water) was observed. It was assumed that these indigenous compounds were utilized simultaneously with the substrate added to the tap water. Consequently, S in equations 2 and 3 is ΔS + Sb, with ΔS representing the added substrate concentration and Sb the apparent indigenous substrate concentration, which was calculated from the Nmax of strain A3 in the blank and its average yield of 1.43 (± 0.13) × 107 CFU μg−1 of C at ≤10 μg of added substrate C liter−1. Ks is the saturation constant and represents S when V is Vmax, whereas Ks′ is the apparent saturation constant and equals Ks/ln 2 (1, 3). The Vmax/Ks ratio (liter μg−1 of C·h−1) is defined as the specific affinity of strain A3 for the substrate tested.

Assessment of growth of F. johnsoniae strain UW101 at low substrate concentrations.

F. johnsoniae strain UW101 (ATCC 17061) was obtained from LGC Standards, United Kingdom. Strain UW101 was precultured in a previously described mineral salts medium (40) supplemented with 100 μg of laminarin C liter−1 and 100 μg of NO3− N liter−1. The preculture was incubated at 15°C and stored at 4°C when the stationary growth phase was reached. Subsequently, growth of strain UW101 was tested at 10 μg C liter−1 of the following individual organic compounds: amylopectin, xyloglucan, pectin, laminarin, maltose, glucose, fructose, casein, gelatin, and lectin. Tap water samples and pasteurized solutions of the individual compounds were prepared as described above. Duplicate sample flasks were incubated at 15°C after inoculation with strain UW101. The colony count of strain UW101 was determined using LLA plates according to the method described above for strain A3.

RESULTS

Utilization of amino acids, peptides, and proteins by F. johnsoniae strain A3.

Strain A3 can utilize various oligo- and polysaccharides (40). In the present study, the ability of strain A3 to utilize amino acids, peptides, and proteins was investigated. Of the 14 individually tested amino acids, alanine, glutamate, glutamine, isoleucine, proline, and threonine were utilized by strain A3, but the Nmax values and growth rates reached with isoleucine and threonine were considerably lower than with alanine, glutamine, glutamate, and proline (Table 2). Strain A3 reached an Nmax value of 8.1 (± 0.09) × 105 CFU ml−1 in tap water supplemented with a mixture of 11 oligo- and polypeptides and proteins at 10 μg C liter−1 per compound, as compared to an Nmax value of 6.4 (± 0.1) × 103 CFU ml−1 in the blank. The dipeptides l-alanyl-l-analine (Ala-Ala), l-alanyl-l-glutamine (Ala-Gln), and l-glutamyl-l-glutamate (Glu-Glu) and the proteins casein, gelatin, and lectin promoted growth of strain A3 when tested individually at 10 μg C liter−1 (Table 2). The growth rate of strain A3 with casein, gelatin, Glu-Glu, or Ala-Gln at 10 μg C liter−1 was higher than that with the individually growth-promoting amino acids. These results imply that strain A3 preferentially utilizes growth-promoting oligopeptides and proteins instead of individually growth-promoting amino acids.

Table 2.

Maximum colony counts (Nmax) and growth rates (V) of F. johnsoniae strain A3 in tap water supplemented with individual amino acids, peptides, and proteins at 10 μg C liter−1

| Amino acid, peptide, or protein | Nmax (×105 CFU ml−1 ± SD) | V (h−1)c |

|---|---|---|

| Amino acids | ||

| Blank Ia | 0.04 (± 0.004) | 0.017 |

| Ala | 0.8 (± 0.01) | 0.029 |

| Asp | NGb | NG |

| Gln | 1.1 (± 0.07) | 0.039 |

| Glu | 1.1 (± 0.05) | 0.038 |

| Gly | NG | NG |

| Ile | 0.5 (± 0.1) | 0.019 |

| Leu | NG | NG |

| Lys | NG | NG |

| Phe | NG | NG |

| Pro | 1.1 (± 0.1) | 0.039 |

| Ser | NG | NG |

| Thr | 0.4 (± 0.2) | 0.016 |

| Tyr | NG | NG |

| Val | NG | NG |

| Peptides and proteins | ||

| Blank IIa | 0.03 (± 0.002) | 0.013 |

| Ala-Ala | 0.6 (± 0.01) | 0.022 |

| Ala-Gln | 1.1 (± 0.2) | 0.046 |

| Gly-Asp | NG | NG |

| Glu-Glu | 1.1 (± 0.01) | 0.081 |

| Gly-Leu-Tyr | NG | NG |

| Poly-Ala | NG | NG |

| Poly-Asp | NG | NG |

| Poly-Glu | NG | NG |

| Casein | 1.3 (± 0.1) | 0.081 |

| Gelatin | 1.2 (± 0.02) | 0.081 |

| Lectin | 1.1 (± 0.06) | 0.034 |

Blank I (i.e., tap water in duplicate flasks) was included in the series of individually tested amino acids, and blank II in the series of individually tested peptides and proteins.

NG, growth not different from growth in the blank.

Standard deviation ≤0.005 h−1 for all V values determined.

Growth kinetics of strain A3 with carbohydrates and proteins.

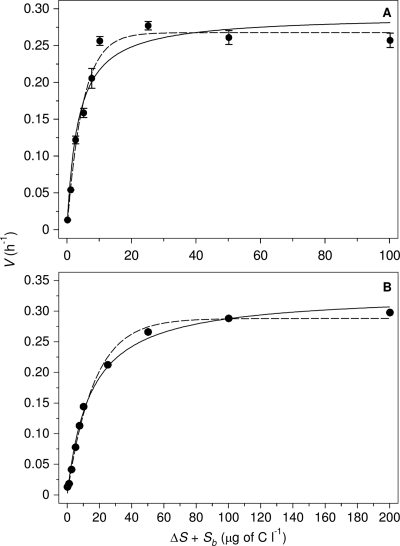

The growth kinetic parameters of strain A3 for each substrate tested were derived from the relationship between the growth rate of strain A3 and the substrate concentration. The data obtained for growth of strain A3 with laminarin fitted best to the Teissier model (Fig. 1 A), whereas growth with fructose, maltose (Fig. 1B), xyloglucan, amylopectin, or gelatin could be equally well described by Monod or Teissier kinetics. The order of the substrates based on the specific affinity (Vmax/Ks ratio) of strain A3 was as follows: laminarin ≫ maltose > amylopectin ≈ gelatin ≈ xyloglucan > fructose (Table 3). A particularly high specific affinity of 7.9 × 10−2 liter·μg−1 of C·h−1 was obtained for laminarin, and the specific affinities of strain A3 for xyloglucan, amylopectin, gelatin, and maltose ranged from approximately 1.1 × 10−2 to 2.3 × 10−2 liter·μg−1 of C·h−1. Strain A3 is clearly adapted to growth with these substrates at μg C liter−1 levels. The Vmax of strain A3 with fructose was comparable to the Vmax with amylopectin and xyloglucan, but fructose did not promote growth of strain A3 at 2.5 and 5.0 μg C liter−1, in contrast to the other substrates tested. As a result, the highest Ks value and lowest specific affinity were observed for fructose, demonstrating that strain A3 has a lower specific affinity for this monosaccharide than for the other carbohydrates tested.

Fig. 1.

Growth rate V (h−1) of F. johnsoniae strain A3 at 15°C in relation to the concentration ΔS of laminarin (A) and maltose (B) added to pasteurized tap water with an apparent indigenous substrate concentration Sb of 0.2 (± 0.00) μg biopolymer C equivalents liter−1. Data modeled according to Monod kinetics (solid line) and Teissier kinetics (dashed line). Error bars represent standard deviation of V in duplicate flasks. In panel B, error bars are not visible because the standard deviation was ≤0.005 h−1 for all V values determined.

Table 3.

Kinetic parameters of F. johnsoniae strain A3 for various substrates tested at 15°C

| Substrate | Kinetic model | Kinetic parameter |

R2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vmax (h−1)a | Ks (μg C liter−1 ± SD) | Specific affinity (×10−2 liter·μg−1 of C·h−1 ± SD) | |||

| Fructose | Monod | 0.22 | 34.4 (± 1.1) | 0.69 (± 0.01) | 0.99 |

| Teissier | 0.19 | 24.0 (± 0.6) | 0.81 (± 0.01) | 0.99 | |

| Maltose | Monod | 0.33 | 14.4 (± 0.1) | 2.3 (± 0.002) | 0.99 |

| Teissier | 0.29 | 11.5 (± 0.1) | 2.5 (± 0.02) | 1.00 | |

| Laminarin | Monod | 0.29 | 3.4 (± 0.3) | 8.5 (± 0.5) | 0.95 |

| Teissier | 0.27 | 3.4 (± 0.2) | 7.9 (± 0.01) | 0.98 | |

| Amylopectin | Monod | 0.23 | 17.0 (± 0.2) | 1.4 (± 0.01) | 0.99 |

| Teissier | 0.20 | 14.3 (± 1.3) | 1.4 (± 0.05) | 0.98 | |

| Xyloglucan | Monod | 0.24 | 21.8 (± 1.4) | 1.1 (± 0.05) | 0.99 |

| Teissier | 0.21 | 17.8 (± 0.8) | 1.2 (± 0.04) | 0.99 | |

| Proline | NDb | 0.019 | <2.5b | >0.76b | |

| Gelatin | Monod | 0.22 | 18.5 (± 0.1) | 1.2 (± 0.01) | 0.99 |

| Teissier | 0.19 | 14.5 (± 0.04) | 1.3 (± 0.01) | 1.00 | |

Standard deviation ≤0.005 h−1 for all Vmax values determined.

Actual Ks and specific affinity could not be determined (ND), because Vmax had already been reached at the lowest ΔS of 2.5 μg C liter−1.

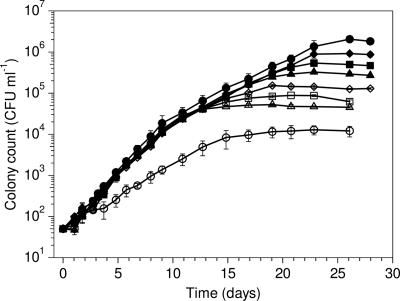

The Ks value and specific affinity for proline could not be calculated, because the growth rate of strain A3 was the same at all substrate concentrations (2.5 to 200 μg C liter−1) and growth was not tested at <2.5 μg C liter−1 (Fig. 2). Apparently, strain A3 already attained its Vmax at 2.5 μg proline C liter−1, which implies that its Ks value with proline is lower than 2.5 μg C liter−1. In addition, the growth curves revealed that the exponential growth of strain A3 in tap water with proline at 10, 25, 50, 100, and 200 μg C liter−1 occurred in two phases (Fig. 2). During the first exponential growth phase (day 0 until day 9), strain A3 grew at a higher rate than during the second exponential growth phase (day 10 until stationary phase). The growth rate of strain A3 in tap water supplemented with proline was 0.039 (± 0.001) h−1 during the first exponential growth phase and equaled the sum of the actual growth rate with this amino acid during the second exponential growth phase (0.019 ± 0.001 h−1) and the growth rate in the blank (0.022 ± 0.001 h−1). These results suggest simultaneous uptake of the added proline and the indigenous organic compounds present in the tap water during the first phase of exponential growth. The same phenomenon occurred when strain A3 was grown in tap water supplemented with alanine or glutamate at 100 μg C liter−1 (growth curves not shown). The actual growth rates of strain A3 with alanine or glutamate at 100 μg C liter−1 (0.015 ± 0.001 h−1 and 0.020 ± 0.000 h−1) were comparable to those observed at 10 μg C liter−1 (0.012 ± 0.001 h−1 and 0.021 ± 0.001 h−1; calculated from data in Table 2), indicating that strain A3 grew at its Vmax at both concentrations.

Fig. 2.

Growth of F. johnsoniae strain A3 at 15°C in tap water supplemented with proline at various concentrations. Symbols: ○, blank, no proline added; ▵, 2.5 μg proline C liter−1 added; □, 5.0 μg proline C liter−1 added; ⋄, 10 μg proline C liter−1 added; ▴, 25 μg proline C liter−1 added; ▪, 50 μg proline C liter−1 added; ⧫, 100 μg proline C liter−1 added; •, 200 μg proline C liter−1 added. Error bars indicate standard deviation of colony count in duplicate flasks.

The nature of the compounds produced by strain A3 upon extracellular degradation of laminarin was assessed by testing its growth with laminaripentaose or laminaribiose at 5 μg C liter−1 in tap water (Sb of 0.6 ± 0.05 μg biopolymer C equivalents liter−1). Laminaripentaose promoted growth of strain A3 at a slightly higher rate (0.18 ± 0.002 h−1) than laminarin (0.16 ± 0.003 h−1), but laminaribiose was not utilized by strain A3. Thus, strain A3 appears to produce laminari-oligosaccharides larger than laminaribiose upon laminarin degradation. To obtain more data about the specific affinity of strain A3 for individual proteins other than gelatin, growth of strain A3 with casein or lectin was also tested at 5 μg C liter−1 in tap water. The growth rate of strain A3 with casein (0.046 ± 0.000 h−1) was nearly the same as that with gelatin (0.045 ± 0.000 h−1), whereas the growth of strain A3 with lectin was almost twice as slow (0.026 ± 0.001 h−1). The nearly identical growth rates of strain A3 with casein and gelatin at 5 μg C liter−1 and at 10 μg C liter−1 (0.081 h−1; Table 2) suggest that the specific affinities for casein and gelatin approximate each other. Strain A3 seems to have a lower specific affinity for lectin than for casein and gelatin, because the growth rates with lectin at 5 μg C liter−1 and 10 μg C liter−1 (0.034 h−1; Table 2) were lower than with the other two proteins.

Yields of strain A3 with carbohydrates and proteins.

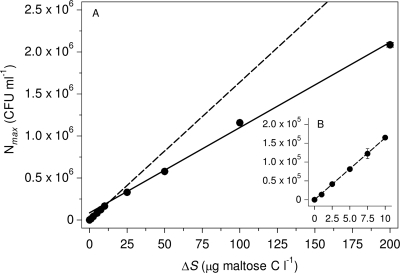

Plotting the Nmax value of strain A3 as a function of maltose concentration revealed two linear relationships (Fig. 3). The first relationship is valid for ΔS values of ≤10 μg C liter−1 and the second for >10 μg C liter−1. This phenomenon was also observed with the other individual substrates tested, except gelatin. Consequently, the yields (expressed in CFU μg−1 of C) of strain A3 estimated with maltose, laminarin, amylopectin, xyloglucan, and proline are higher at ΔS values of ≤10 μg C liter−1 than at ΔS values of >10 μg C liter−1 (Table 4).

Fig. 3.

Maximum colony count (Nmax) of F. johnsoniae strain A3 at 15°C in relation to the concentration ΔS of maltose added to pasteurized tap water. (A) Dashed line represents the linear relationship between Nmax and ΔS when <10 μg C liter−1. Solid line shows the linear relationship between Nmax and ΔS when >10 μg C liter−1. Error bars indicate standard deviation of Nmax in duplicate flasks. (B) Data points of the linear relationship between Nmax and substrate concentration ΔS when <10 μg C liter−1.

Table 4.

Yields of F. johnsoniae strain A3 with various individual substrates tested at 15°C

| Substrate | Yield |

|

|---|---|---|

| ΔS range (μg C liter−1) | Y (×107 CFU μg−1 of C ± SD) | |

| Fructose | 0–10 | --a |

| 10–200 | 0.93 (± 0.02) | |

| Maltose | 0–10 | 1.65 (± 0.03) |

| 10–200 | 1.01 (± 0.02) | |

| Laminarin | 0–10 | 1.30 (± 0.04) |

| 10–200 | 0.75 (± 0.01) | |

| Amylopectin | 0–10 | 1.47 (± 0.03) |

| 10–100 | 0.98 (± 0.10) | |

| Xyloglucan | 0–10 | 1.45 (± 0.01) |

| 10–100 | 0.89 (± 0.02) | |

| Proline | 0–10 | 1.42 (± 0.03) |

| 10–200 | 0.99 (± 0.03) | |

| Gelatin | 0–200 | 1.31 (± 0.07) |

—, no linear relationship between Nmax and ΔS when <10 μg C liter−1.

The 53 Nmax/TDC ratios used to calculate the mean plating efficiency came from a normal distribution (P = 0.30). The mean plating efficiency of strain A3 was 101.9% (SEM 1%; n = 53) with a 95% confidence interval from 99.8% to 103.8% efficiency. This 95% confidence interval includes 100%, and therefore it can be assumed with 95% certainty that the mean plating efficiency did not differ from 100% and that each cell of strain A3 formed a colony. Thus, the lower yield for ΔS values of >10 μg C liter−1 did not result from a lower plating efficiency.

Two average yields were calculated from the yields obtained with the seven individually tested substrates: (i) Ymean of 1.43 (± 0.13) × 107 CFU μg−1 of C, when the Nmax of strain A3 is ≤1.5 × 105 CFU liter−1 and thus represents a concentration of ≤10 μg biopolymer C liter−1; and (ii) Ymean of 0.98 (± 0.17) × 107 CFU μg−1 of C, when the Nmax of strain A3 is > 1.5 × 105 CFU ml−1 and indicates the presence of > 10 μg biopolymer C liter−1.

Growth of F. johnsoniae strain UW101 at μg liter−1 levels.

Of the 10 carbohydrates and proteins tested, only laminarin and maltose promoted growth of strain UW101 at 10 μg C liter−1. Strain UW101 attained a higher growth rate with laminarin (0.16 ± 0.001 h−1) than with maltose (0.07 ± 0.000 h−1), but its Nmax value with laminarin (5.9 [± 0.3] × 104 CFU ml−1) was the same as with maltose (6.2 [± 0.1] × 104 CFU ml−1). These growth parameters are significantly lower than the growth rate and Nmax value reached by strain A3 when it was grown with laminarin (0.26 ± 0.001 h−1; 1.6 [± 0.1] × 105 CFU ml−1) or maltose at 10 μg C liter−1 (0.16 ± 0.002 h−1; 1.7 [± 0.0] × 105 CFU ml−1). In addition, unlike strain A3, strain UW101 did not grow in the blank during the incubation period. Hence, strain UW101 seems less well adapted to oligotrophic conditions than strain A3.

DISCUSSION

Biopolymer utilization by F. johnsoniae strains A3 and UW101.

The growth rates of strain A3 with proline, glutamine, glutamate, or alanine at 10 and 100 μg C liter−1 in the present study were nearly identical to the growth rate of the strain (0.016 ± 0.000 h−1) with a mixture of 20 different amino acids (10 μg C liter−1 per compound) in a previous study (40). The higher growth rates of strain A3 with Ala-Gln, Glu-Glu, casein, gelatin, and lectin than with the amino acid mixture and the individually growth-promoting amino acids indicate the preference of strain A3 for utilizing oligopeptides and proteins as a source of energy and carbon. Casein, gelatin, and lectin, which were utilized by strain A3 at 10 and 5 μg C liter−1, differ in amino acid composition and sequence. The main constituents (>10% wt/wt) in casein are glutamate, leucine, and proline; gelatin is rich in glycine, proline, hydroxyproline, and alanine; and aspartate and serine are predominant in lectin (14, 15, 28). In addition, more than 10 other types of amino acids are present in each of the three proteins at concentrations varying from 0.5 to 10%. The fact that strain A3 can utilize various complex proteins but only a limited number of individual amino acids as a sole energy source demonstrates that oligopeptides are the main extracellular products of protein degradation by the microorganism. These findings are consistent with previous observations indicating that strain A3 preferentially utilizes oligo- and polysaccharides instead of monosaccharides and produces oligosaccharides upon extracellular polysaccharide degradation that are not hydrolyzed before uptake into the cytoplasm (40). A comparable biopolymer degradation strategy has been suggested for Flavobacterium sp. strain S12 (45). Furthermore, the growth of strain A3 with the amino acid mixture and with the individual proteins suggests that amino acids and oligopeptides not serving as an individual energy source are utilized as a carbon source in the presence of an appropriate energy source(s).

Like strain A3, F. johnsoniae strain UW101 can degrade laminarin, amylopectin, pectin, xylan, xyloglucan, gelatin, and casein (7, 32). Genome sequence analysis has demonstrated that strain UW101 possesses proteins to bind specific biopolymers (e.g., α/β-glucans, hemicelluloses, chitin, pectins, peptides) to its outer membrane and outer membrane-associated enzymes to degrade the bound biopolymers into oligomers that pass the outer membrane via oligomer-specific porins (32). Based on its metabolic capacities, it seems likely that strain A3 has also included outer membrane-associated binding proteins and enzymes and oligomer-specific porins in its biopolymer utilization systems. However, growth of strain UW101 with the aforementioned biopolymers has been demonstrated only at high substrate concentrations of 5 or 10 g of biopolymer liter−1 (7, 32). In the present study, it was shown that strain UW101 utilized only maltose and laminarin of the 10 carbohydrates and proteins tested at 10 μg C liter−1, whereas strain A3 utilized all 10 compounds, except glucose (Table 2) (40). Moreover, strain UW101 grew at significantly low rates with maltose and laminarin at 10 μg C liter−1 compared with strain A3. The Nmax values reached by strain UW101 when grown with these compounds were almost thrice lower than those of strain A3, which suggests that cells of strain UW101 were larger than those of strain A3 during growth at μg C liter−1 levels. These physiological differences between strains UW101 and A3 and their relatively low 16S rRNA gene similarity of 97% reduce the extent to which the whole-genome sequence data of strain UW101 can be used to elucidate biopolymer utilization by strain A3. Growth experiments with biopolymer-degrading bacteria at μg C liter−1 levels clearly provide essential information in addition to genome sequence information.

Growth kinetics of F. johnsoniae strain A3 for biopolymers.

The Monod model is based on the theory that a single rate-limiting, saturation kinetics-exhibiting transport system at the cytoplasmic membrane controls bacterial growth (33), whereas the Teissier model assumes growth to depend on diffusion-controlled substrate supply through the outer membrane (43). However, the mathematical difference between these models is small at low substrate concentrations (26), which could explain why both were applicable to the growth of strain A3 with fructose, maltose, xyloglucan, amylopectin, and gelatin. The similarity of the two specific affinities obtained for growth of strain A3 with laminarin demonstrates that, despite the better fit of the growth data to the Teissier model, the Monod model could also be applied. The growth kinetic parameters of strain A3 have been determined by assuming that ΔS was utilized simultaneously with Sb. Simultaneous utilization is expected when ΔS values are close to Sb, but sequential utilization seems more likely when ΔS is high (i.e., the added substrate is used preferentially) (48). However, the specific affinities of strain A3 did not significantly change when preferential utilization of the added substrate at ΔS values of ≥25 μg C liter−1 was assumed (data not shown; P < 0.01, t test), which indicates that the low apparent Sb (0.2 to 2 biopolymer C equivalents liter−1) did not significantly contribute to these high substrate concentrations.

The lower specific affinity of strain A3 for fructose than for the polysaccharides and gelatin confirms that strain A3 is specialized in biopolymer utilization at μg C liter−1 levels. Few data are available on the growth kinetics of other biopolymer-consuming, oligotrophic bacteria for comparison with the growth kinetic parameters of strain A3. The high specific affinity of strain A3 for laminarin (7.9 × 10−2 liter·μg−1 of C·h−1) is close to the specific affinities reported for growth of Flavobacterium sp. strain S12 with maltodextrins (7.1 × 10−2 to 8.3 × 10−2 liter·μg−1 of C·h−1) and to the specific affinity observed for growth of Flavobacterium sp. strain 166 with starch (6.9 × 10−2 liter·μg−1 of C·h−1) (45, 49). Higher specific affinities have been reported only for Aeromonas hydrophila M800 grown with either oleate (11 × 10−2 liter·μg−1 of C·h−1) or arginine (28 × 10−2 liter·μg−1 of C·h−1) and for Polaromonas strain P315 grown with acetate (25 × 10−2 liter·μg−1 of C·h−1) (30, 47). In review studies on other oligotrophic bacteria consuming LMW compounds, the highest reported specific affinity was 1.2 × 10−2 liter·μg−1 of C·h−1 for the marine bacterium Cycloclasticus oligotrophus grown with toluene (recalculated from a specific affinity of 47.4 liter·mg−1 of cells·h−1) (9–11, 42). Hence, the higher specific affinities of strain A3 for laminarin, maltose, gelatin, and amylopectin, along with those of strains S12, 166, M800, and P315, confirm that these strains are adapted to oligotrophic conditions.

Extracellular degradation is the first process in biopolymer utilization and could control bacterial growth with biopolymers (5, 31). The slightly higher growth rate of strain A3 with laminaripentaose (0.18 ± 0.002 h−1) than with laminarin (0.16 ± 0.003 h−1) at 5 μg C liter−1 indicates that extracellular degradation of laminarin was not rate limiting. However, the lower specific affinity of strain A3 for amylopectin than for laminarin and the higher specific affinity for maltose than for amylopectin reveal that extracellular degradation was rate limiting in amylopectin utilization by strain A3. The 104- to 5 × 105-kDa and extensively branched amylopectin molecule is clearly more difficult to degrade than the 5- to 6-kDa linear laminarin molecule (6, 37). In contrast to amylopectin, maltose can diffuse directly through the outer membrane of strain A3 via nonspecific porins and probably also via a maltodextrin-specific porin for amylopectin degradation products (35). The lower specific affinity of strain A3 for maltose than for laminarin suggests that maltose was transported across the cytoplasmic membrane at a lower rate than the oligosaccharides produced upon laminarin degradation, which were presumably larger than laminaribiose. Like Flavobacterium sp. strain S12, strain A3 may degrade amylopectin into maltodextrins instead of maltose (45), but additional research would be needed to assess if strain A3 has higher specific affinities for maltodextrins than for maltose.

Strain A3 has nearly the same specific affinity for xyloglucan as for amylopectin, despite the lower molecular mass of xyloglucan (200 kDa). The multiple types of monosaccharides and glycosidic linkages in xyloglucan probably complicate its degradation and utilization by strain A3 (56). Nevertheless, the specific affinity of strain A3 for xyloglucan is still significantly higher than for fructose, which promoted growth of strain A3 at μg C liter−1 levels, in contrast to eight other individually tested monosaccharides (40). These eight individual monosaccharides were probably not taken up into its cytoplasm, and thus it seems likely that transport across the cytoplasmic membrane controlled the growth of strain A3 with fructose.

The apparently lower specific affinity of strain A3 for lectin than for casein and gelatin may be attributed to the fact that strain A3 cannot utilize the main amino acid constituents in lectin (e.g., aspartate and serine) as a sole energy source, in contrast to some of the main amino acid constituents in casein and/or gelatin (e.g., proline and glutamate) (Table 2). Consequently, it may be more difficult for strain A3 to degrade lectin into oligopeptides from which energy can be obtained. The lowest Ks of strain A3 (<2.5 μg C liter−1) was observed for growth with proline, but the Vmax of strain A3 with proline (0.019 h−1) was significantly lower than with the other substrates tested.

As mentioned in the first section of this discussion, the growth rates of strain A3 with proline, glutamine, glutamate, or alanine at 10 and 100 μg C liter−1 were comparable to its growth rate of 0.016 ± 0.000 h−1 with a mixture of 20 different amino acids (10 μg C liter−1 per compound) (40). However, in the presence of a mixture of 6 carbohydrates (10 μg C liter−1 per compound) that promoted the growth of strain A3 at a rate of 0.29 ± 0.003 h−1, the amino acid mixture was utilized simultaneously with the carbohydrate mixture, indicating that the amino acids may have served as carbon sources (40). These observations suggest that metabolism in the cytoplasm was the rate-determining step in the growth of strain A3 with the aforementioned individual amino acids and the amino acid mixture.

Overall, the kinetic parameters determined in the present study demonstrate that strain A3 has high-affinity, high-capacity utilization systems for polysaccharides and proteins as individual energy sources, and a high-affinity, low-capacity utilization system that saturates at very low substrate concentrations for proline as the energy source.

Yields of F. johnsoniae strain A3 with biopolymers.

The average cell yield of strain A3 with maltose, laminarin, amylopectin, and xyloglucan was 1.6 times higher at ≤10 μg C liter−1 (1.47 × 107 CFU μg−1 of C) than at >10 μg C liter−1 (0.91 × 107 CFU μg−1 of C). The cell yields of Flavobacterium sp. strain S12 with maltose at ≤5 μg C liter−1 and with maltopentoase and maltohexaose at ≤10 μg C liter−1 were also higher than those obtained at >5 or 10 μg C liter−1 (45). From the ATP levels measured at the maximum growth level of strain A3 with maltose, laminarin, amylopectin, and xyloglucan (data not shown), the average ATP level cell−1 of strain A3 was calculated. The ATP level cell−1 was 2.5 times lower at ≤10 μg C liter−1 (0.061 ± 0.01 fg cell−1) than at >10 μg C liter−1 (0.16 ± 0.04 fg cell−1). Thus, the ATP level cell−1 had increased more than the cell yield had decreased at >10 μg C liter−1. It has been hypothesized that oligotrophic bacteria can release excess substrate C by overflow metabolism to prevent too-high internal carbon concentrations (10, 25). However, to our knowledge, there are no supporting data for this hypothesis and consequently it is unclear whether the higher ATP level cell−1 and lower cell yield at >10 μg C liter−1 can be attributed to overflow metabolism. Another explanation is that strain A3 formed smaller cells and maintained a more than proportionally lower ATP level cell−1 during growth at ≤10 μg C liter−1 than at >10 μg C liter−1. The larger surface area-to-volume ratio of small cells should provide strain A3 with a greater ability to compete for substrates in natural aquatic environments, because compounds can diffuse more efficiently into (e.g., nutrients and oxygen) and out of (e.g., waste, extracellular enzymes) the cell (25, 57). The strategy to maintain a lower ATP level cell−1 when grown under C-limiting batch conditions has been demonstrated for other heterotrophic bacteria (23).

It has also been reported that heterotrophic bacteria growing with glucose and an excess of nitrogen and phosphorus can accumulate glycogen as an energy reserve, for which additional ATP is required (55). Hence, the higher ATP level cell−1 and lower cell yield of strain A3 with maltose, laminarin, amylopectin, and xyloglucan at >10 μg C liter−1 may also suggest that a certain amount of carbohydrate was converted into glycogen or another energy reserve. Bacteria generally do not convert proteins into energy reserve polymers (i.e., polysaccharides and lipids) (13), which could explain why strain A3 displayed only one cell yield and one ATP level cell−1 with gelatin (0.086 ± 0.001 fg CFU−1 at ≤10 μg C liter−1; 0.087 ± 0.01 fg CFU−1 at >10 μg C liter−1). Elucidation of the relationship between substrate concentration and cell properties (e.g., size, ATP content, glycogen content) of strain A3 during growth with polysaccharides or proteins would have required research beyond the scope of our study.

Biopolymer utilization in the oligotrophic freshwater environment.

It has been suggested that growth kinetics of oligotrophic bacteria should be assessed under mixed-substrate conditions, because natural oligotrophic environments contain complex mixtures of compounds (16, 27). Indeed, heterotrophic bacteria can utilize multiple LMW energy and carbon sources simultaneously and at lower threshold concentrations than during growth with single substrates (21, 27, 29). Furthermore, a variety of heterotrophic bacteria (including strain A3) can utilize LMW organic compounds that individually do not serve as the energy source when growth-promoting organic compounds are present (40, 47, 50, 52). The growth kinetic parameters of strain A3 with biopolymers have been determined only in the presence of a few μg liter−1 of indigenous substrates in the blank and not in the presence of other added substrates. Nevertheless, the specific affinities obtained for strain A3 under these conditions still clearly demonstrate that strain A3 is highly proficient in the utilization of biopolymers under (ultra)oligotrophic conditions. The results of our study prove that biopolymers promote the growth of heterotrophic bacteria at a few μg C liter−1 in (ultra)oligotrophic freshwater environments and that strain A3 is a suitable model organism to study the bacterial utilization of biopolymers at low concentrations in these environments.

Strain A3 can also take up amino acids with high affinity at μg C liter−1 levels, but representatives of Pseudomonas, Aeromonas, and Klebsiella species have this ability as well (46, 50–52). Apparently, amino acid utilization at low concentrations is relatively common among oligotrophic freshwater bacteria. Biopolymer utilization in oligotrophic freshwater environments, however, seems to be dominated by Cytophagia-Flavobacteria (20, 24, 40). The high specific affinities of strain A3 for different biopolymers confirm that some planktonic Cytophagia-Flavobacteria are highly adapted to growth with these compounds at μg liter−1 levels and support the hypothesis that Cytophagia-Flavobacteria play an important role in the degradation of biopolymers in (ultra)oligotrophic freshwater environments (24). Assessment of the role of attached heterotrophic bacteria in the degradation of biopolymers in these environments requires further investigation.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by SenterNovem and the Joint Research Program of the Water Supply Companies in the Netherlands and conducted within the framework of the NOM project “Breakthrough in the biological stability of drinking water” (project number IS 054040).

We thank Ton Braat for skillful technical assistance and Hauke Smidt and Marco Dignum for valuable discussions.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 29 July 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Aguiar W. B., Faria L. F. F., Couto M. A. P. G., Araujo O. Q. F., Pereira N. 2002. Growth model and prediction of oxygen transfer rate for xylitol production from d-xylose from C. guilliermondii. Biochem. Eng. J. 12:49–59 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Amon R. M. W., Benner R. 1996. Bacterial utilization of different size classes of dissolved organic matter. Limnol. Oceanogr. 41:41–51 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Andrade C. M., Aguiar W. B., Antranikian G. 2001. Physiological aspects involved in production of xylanolytic enzymes by deep-sea hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrodictium abyssi. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 91–93:655–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Arnosti C. 2003. Microbial extracellular enzymes and their role in dissolved organic matter cycling, p. 315–342 In Findley S. E. G., Sinsabaugh R. L. (ed.), Aquatic ecosystems: interactivity of dissolved organic matter. Elsevier Science, San Diego, CA [Google Scholar]

- 5. Arnosti C. 2004. Speed pumps and barricades in the carbon cycle: substrate structural effects on carbon cycling. Mar. Chem. 92:263–273 [Google Scholar]

- 6. BeMiller J. N., Whistler R. L. 1996. Carbohydrates, p. 157–223 In Fennema O. R. (ed.), Food chemistry, 3rd ed. Marcel Dekker Inc., New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bernadet J.-F., Bowman J. P. 2006. The genus Flavobacterium, p. 481–531 In Dworkin M., Falkow S., Rosenberg E., Schleifer K.-H., Stackebrandt E. (ed.), The prokaryotes. Springer, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bertilsson S., Jones J. B., Jr 2003. Supply of dissolved organic matter to aquatic ecosystems: autochthonous sources, p. 315–342 In Findley S. E. G., Sinsabaugh R. L. (ed.), Aquatic ecosystems: interactivity of dissolved organic matter. Elsevier Science, San Diego, CA [Google Scholar]

- 9. Button D. K. 1985. Kinetics of nutrient-limited transport and microbial growth. Microbiol. Rev. 49:270–297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Button D. K. 1998. Nutrient uptake by microorganisms according to kinetic parameters from theory as related to cytoarchitecture. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:636–645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Button D. K., Robertson B. R., Lepp P. W., Schmidt T. M. 1998. A small, dilute-cytoplasm, high-affinity, novel bacterium isolated by extinction culture and having kinetic constants compatible with growth at ambient concentrations of dissolved nutrients in seawater. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:4467–4476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cottrell M. T., Kirchman D. L. 2000. Natural assemblages of marine proteobacteria and members of the Cytophaga-Flavobacter cluster consuming low- and high-molecular-weight dissolved organic matter. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:1692–1697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dawes E. A., Senior P. J. 1973. The role and regulation of energy reserve polymers in micro-organisms. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 10:135–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Eastoe J. E. 1955. The amino acid composition of mammalian collagen and gelatin. Biochem. J. 61:589–600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Edelman G. M., et al. 1972. The covalent and three-dimensional structure of concanavalin A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 69:2580–2584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Egli T. 1995. The ecological and physiological significance of the growth of heterotrophic microorganisms with mixtures of substrates. Adv. Microb. Ecol. 14:305–386 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Eiler A., Bertilsson S. 2004. Composition of freshwater bacterial communities associated with cyanobacterial blooms in four Swedish lakes. Environ. Microbiol. 6:1228–1243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Eiler A., Bertilsson S. 2007. Flavobacteria blooms in four eutrophic lakes: linking population dynamics of freshwater bacterioplankton to resource availability. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:3511–3518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Elifantz H., Malmstrom R. R., Cottrell M. T., Kirchman D. L. 2005. Assimilation of polysaccharides and glucose by major bacterial groups in the Delaware estuary. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:7799–7805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Glöckner F. O., Fuchs B. M., Amann R. 1999. Bacterioplankton compositions of lakes and oceans: a first comparison based on fluorescence in situ hybridization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:3721–3726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Harder W., Dijkhuizen L. 1982. Strategies of mixed substrate utilization in microorganisms. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 297:459–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hobbie J. E., Daley R. J., Jasper S. 1977. Use of nuclepore filters for counting bacteria by fluorescence microscopy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 33:1225–1228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Karl D. M. 1980. Cellular nucleotide measurements and application in microbial ecology. Microbiol. Rev. 44:739–796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kirchman D. L. 2002. The ecology of Cytophaga-Flavobacteria in aquatic environments. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 39:91–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Koch A. L. 1996. What size should a bacterium be? A question of scale. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 50:317–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Konak A. R. 1974. Derivation of a generalised Monod equation and its application. J. Appl. Chem. Biotechnol. 24:453–455 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kovarova-Kovar K., Egli T. 1998. Growth kinetics of suspended microbial cells: from single-substrate-controlled growth to mixed-substrate kinetics. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:646–666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lauer B. H., Baker B. E. 1977. Amino acid composition of casein isolated from the milks of different species. Can. J. Zool. 55:231–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lendenmann U., Snozzi M., Egli T. 1996. Kinetics of the simultaneous utilization of sugar mixtures by Escherichia coli in continuous culture. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:1493–1499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Magic-Knevez A., van der Kooij D. 2006. Nutritional versatility of two Polaromonas related bacteria isolated from biological granular activated carbon filters, p. 303–311 In Gimbel R., Graham N. J. D., Collins M. R. (ed.), Recent progress in slow sand and alternative biofiltration processes. IWA Publishing, London, UK [Google Scholar]

- 31. Maxham J. V., Maier W. J. 1978. Bacterial growth on organic polymers. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 20:865–898 [Google Scholar]

- 32. McBride M. J., et al. 2009. Novel features of the polysaccharide-digesting gliding bacterium Flavobacterium johnsoniae as revealed by genome sequence analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:6864–6875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Monod J. 1949. The growth of bacterial cultures. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 9:371–394 [Google Scholar]

- 34. Münster U. 1993. Concentrations and fluxes of organic carbon substrates in the aquatic environment. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 63:243–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nikaido H. 2003. Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability revisited. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67:593–656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ortega-Retuerta E., Reche I., Pulido-Villena E., Agustí S., Duarte C. M. 2009. Uncoupled distributions of transparent exopolymer particles (TEP) and dissolved carbohydrates in the Southern Ocean. Mar. Chem. 115:59–65 [Google Scholar]

- 37. Painter T. J. 1983. Structural evolution of glycans in algae. Pure Appl. Chem. 55:677–694 [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pakulski J. D., Benner R. 1994. Abundance and distribution of carbohydrates in the ocean. Limnol. Oceanogr. 39:930–940 [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pinhassi J., et al. 1999. Coupling between bacterioplankton species composition, population dynamics, and organic matter degradation. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 17:13–26 [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sack E. L. W., J. van der Wielen P. W. J., van der Kooij D. 2010. Utilization of oligo- and polysaccharides at microgram-per-litre levels in freshwater by Flavobacterium johnsoniae. J. Appl. Microbiol. 108:1430–1440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Salyers A. A., Reeves A., D'Elia J. 1996. Solving the problem of how to eat something as big as yourself: diverse bacterial strategies for degrading polysaccharides. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 17:470–476 [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schut F., et al. 1993. Isolation of typical marine bacteria by dilution culture: growth, maintenance, and characteristics of isolates under laboratory conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:2150–2160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Teissier G. 1942. Growth of bacterial populations and the available substrate concentration. Rev. Sci. 3208:209–214(In French.) [Google Scholar]

- 44. van der Kooij D. 1992. Assimilable organic carbon as an indicator of bacterial regrowth. J. Am. Water Works Assoc. 84:57–65 [Google Scholar]

- 45. van der Kooij D., Hijnen W. A. M. 1985. Determination of the concentration of maltose- and starch-like compounds in drinking water by growth measurements with a well-defined strain of a Flavobacterium species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 49:765–771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. van der Kooij D., Hijnen W. A. M. 1988. Multiplication of a Klebsiella pneumoniae strain in water at low concentrations of substrates. Water Sci. Technol. 20:117–123 [Google Scholar]

- 47. van der Kooij D., Hijnen W. A. M. 1988. Nutritional versatility and growth kinetics of an Aeromonas hydrophila strain isolated from drinking water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 54:2842–2851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. van der Kooij D., Hijnen W. A. M. 1984. Substrate utilization by an oxalate-consuming Spirillum species in relation to its growth in ozonated Water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 47:551–559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. van der Kooij D., Hijnen W. A. M. 1981. Utilization of low concentrations of starch by a Flavobacterium species isolated from tap water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 41:216–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. van der Kooij D., Oranje J. P., Hijnen W. A. M. 1982. Growth of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in tap water in relation to utilization of substrates at concentrations of a few micrograms per liter. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 44:1086–1095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. van der Kooij D., Visser A., Hijnen W. A. M. 1980. Growth of Aeromonas hydrophila at low concentrations of substrates added to tap water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 39:1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. van der Kooij D., Visser A., Oranje J. P. 1982. Multiplication of fluorescent pseudomonads at low substrate concentrations in tap water. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 48:229–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. van der Wielen P. W. J. J., van der Kooij D. 2010. Effect of water composition, distance and season on the adenosine triphosphate concentration in unchlorinated drinking water in the Netherlands. Water Res. 44:4860–4867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Volk C. J., Volk C. B., Kaplan L. A. 1997. Chemical composition of biodegradable dissolved organic matter in streamwater. Limnol. Oceanogr. 42:39–44 [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wilson W. A., et al. 2010. Regulation of glycogen metabolism in yeast and bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 34:952–985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. York W. S., Harvey L. K., Guillen R., Albersheim P., Darvill A. G. 1993. Structural analysis of tamarind seed xyloglucan oligosaccharides using beta-galactosidase digestion and spectroscopic methods. Carbohydr. Res. 248:285–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Young K. D. 2007. Bacterial morphology: why have different shapes? Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 10:596–600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Zeder M., Peter S., Shabarova T., Pernthaler J. 2009. A small population of planktonic Flavobacteria with disproportionally high growth during the spring phytoplankton bloom in a prealpine lake. Environ. Microbiol. 11:2676–2686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.