Abstract

Prion-related disorders (PrDs) are caused by the accumulation of a misfolded and protease-resistant form of the cellular prion, leading to neuronal dysfunction and massive neuronal loss. In humans, PrDs have distinct etiologies including sporadic, infectious and familial forms, which present common clinical features; however, the possible existence of common neuropathogenic events are not known. Several studies suggest that alterations in protein folding and quality control mechanisms at the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) are a common factor involved in PrDs. However, the mechanism underlying ER dysfunction in PrDs remains unknown. We have recently reported that alterations in ER calcium homeostasis are common pathological events observed in both infectious and familial PrD models. Perturbation in calcium homeostasis directly correlated with the occurrence of ER stress and higher susceptibility to protein folding stress. We envision a model where alterations in ER function are central and common events underlying prion pathogenesis, leading to general alterations on protein homeostasis networks.

Key words: prion protein, calcium, endoplasmic reticulum stress, unfolded protein response, chaperones

The presence of abnormal protein inclusion in the brain is a common pathologic feature of many neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer's disease (AD), Parkinson's disease, Huntington's disease, Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and Prionrelated Disorders (PrDs).1 PrDs, also known as transmissible spongiform encephalopathies, are fatal neurodegenerative diseases affecting humans and other mammals, characterized by a spongiform degeneration of the brain and progressive neuronal loss.2 At the biochemical level, PrDs are associated with the accumulation and deposition of the abnormal and misfolded form of the cellular prion protein (PrPC), termed PrPRES (for protease resistant form).3 Depending on its etiology, PrDs can be divided in three main forms, familial, sporadic and infectious.2 Familial PrDs including Creutzfeld-Jackob disease (CJD), fatal familial insomnia (FFI) and Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker syndrome (GSS), are all linked to mutations in the gene encoding PrPC, PRNP and represent approximately 10% of total cases. In humans, the infectious form is very rare and accounts for less than 1% of total cases, highlighting the new variant Creutzfeld-Jackob disease (vCJD). The sporadic CJD underlay around 90% of total PrD cases in humans.2,3 The mechanism triggering the misfolding of PrPC in infectious forms is very unusual. The most accepted “protein-only” hypothesis postulates that infectious prion pathogenicity results from a direct interaction between the infectious/misfolded PrP form, termed PrPRES, and the native folded and fully matured PrPC. This interaction is predicted to induce a conformational change of its primarily α-helical structure to an insoluble β-sheet conformation, a process that occurs cyclically on an autocatalytic manner as we and others have demonstrated.2,4 In PrD familial forms, PrP misfolding occurs due to direct mutations in the PRNP gene. The factors involved in the misfolding of PrP in sporadic cases are still unknown. It is possible that environmental factors, together with specific genetic backgrounds (mutation of genes different of PRNP), or undetected somatic mutations may increase the susceptibility to generate de novo PrPRES in sporadic CJD.

PrP is a membrane attached protein that undergoes post-translational processing in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and Golgi, including the addition of a glycosyl phosphatidyl inositol (GPI) anchor, C- and N-terminal proteolytic processing, formation of one disulphide bond, the addition of N-linked glycosylations.5 After trafficking through the secretory pathway, fully matured PrPC localizes in the outer surface of the plasma membrane in cholesterol-rich lipid domains (lipids rafts), and cycle through the endocytic pathway with a half live of ∼6 hours.5 During the folding process at the ER, around 10% of PrPC is naturally misfolded and eliminated through the ER-associated degradation (ERAD) pathway by proteasomes.6 In the case of the familiar form of PrDs, some PrP mutants are retained and aggregated in the ER and Golgi, where they may exert their pathological effects.7 However, the molecular mechanisms explaining the neurotoxicity of PrP mutants and the factors regulating this process are still elusive. In contrast to PrP mutants linked to familial PrDs, the generation of misfolded PrP in infectious forms of the disease is proposed to occur at the plasma membrane and during its cycling through the endocytic pathway.7,8 However, many studies in infectious PrDs models also have shown the trafficking and accumulation of PrPRES at the cytosol and ER of the infected cells.9–12

Altered ER Homeostasis in Prion-related Disorders

Different stress condition can affect the normal ER homeostasis, interfering with the correct folding of proteins in the ER lumen. This condition, termed “ER stress,” engages a complex integrated signaling cascade known as the unfolded protein response (UPR).13 The UPR aims reestablishing homeostasis by recovering the capacity of the cell to synthesize properly folded proteins at the ER.

Several groups have observed the occurrence of ER stress responses in PrDs including the activation of the UPR transcription factor XBP-1 splicing14 and the action of JNK and ERK.14,15 In human CJD patients and mouse models, the upregulation of several chaperons and foldases such as such as Grp78/BiP, Grp94 and Grp58/ERp57 proteins is observed, suggesting abnormal ER homeostasis.14–20 The levels of ERp57 increase even during the asymptomatic stage of the disease, and it is detected in high levels in brain regions that are more resistant to undergo degeneration in scrapie prion-infected mice.18 Additionally, in studies using Neuro2a neuroblastoma cells we demonstrated that ERp57 operates as a neuroprotective factor against infectious PrPRES neurotoxicity.18 Interestingly, ERp57 co-immunoprecipitates with PrP.18 In addition to these results, a proteomic analysis of postmortem brain samples from patients affected with sporadic CJD demonstrated that ERp57 is highly expressed in the pathology.20 A recent report suggests that the expression of a GSS-linked PrP mutant triggers ER stress in a cellular model.21

Perturbations of ER homeostasis leads to generation of intermediary misfolded forms of PrPC, increasing its susceptibility to be converted into PrPRES in vitro.22–24 This partial misfolding of PrPC, may be reverted by the overexpression of UPR components such as XBP-1, ATF4 and ATF6,23 suggesting that the UPR has an active role in preventing neurodegeneration. In cellular models, ER stress conditions reduce PrP co-translational translocation, favoring accumulation of aggregation-prone cytosolic species, which retain the signal sequence but lack N-glycans and disulfides.24 Inhibition of proteasomes further increases the levels of cytosolic PrP.24 Overexpression of UPR transcription factor XBP1 facilitated ER translocation, suggesting possible neuroprotective effects of this pathway.24 Similarly, other groups have shown that cytosolic accumulation of PrP lead to accumulation PrPRES-like species normally degraded by ERAD, leading to neurotoxicity.10,11,19,25–27 However, exposition of a XBP-1 deficient mouse to scrapie prions did not alter PrP misfolding or pathogenesis,14 neither caspase-12 deficiency (an ER located caspase), modified disease progression on an infectious PrD mouse model.15 Another report suggested that neurodegeneration in PrDs might be dependent on chronic ER stress produced by PrPRES accumulation due to persistent activation of a “preemptive” quality control system (pQC) that aborts the ER translocation of PrP leading to cytosolic accumulation of PrP, resulting in neurotoxicity.19

Abnormal Calcium Homeostasis: A Common Factor in the Pathogenesis of Prions

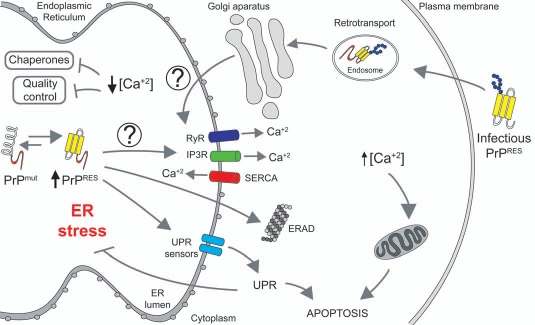

There are many different cellular perturbations that can generate ER stress including expression of mutant proteins, altered protein maturation, abnormal redox status, chaperone inactivation and inhibition of the proteasome or the ERAD pathway. In addition, decreased ER calcium content is an important factor leading to ER stress.28 In neurons, calcium signals play a relevant role as a second messenger, controlling synaptic functions and cell viability. At basal conditions, ER calcium concentrations are close to 300 µM, whereas cytosolic calcium concentrations usually are 5–50 µM.29 Several key ER chaperones require optimal calcium concentrations for their protein folding activity.30 Thus, ER-calcium depletion may inhibit the folding and maturation proteins.31 Besides, sustained increase of cytosolic calcium may also induce mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis via the activation of proteins like calcineurin or by overload of mitochondrial calcium (Fig. 1).32 For this reason, the regulation of specific concentration of calcium in the cytosol and ER lumen are critical for maintain normal cellular functions and protein homeostasis.

Figure 1.

ER stress and altered calcium homeostasis in Prion-related Disorders. Misfolded mutant PrP associated with inherited forms of PrDs accumulate in the ER and may affect the activity of proteins controlling the influx/efflux of calcium (i.e., SERCA, IP3Rs and/or RYRs), decreasing in the long term ER calcium content. This event may alter the activity of several ER chaperones involved in protein folding and quality control mechanisms, generating ER stress. Chronic ER stress will induce sustained activation of the unfolded protein response (UPR), leading to neuronal apoptosis. In contrast, a fraction of the infectious PrP form may be transported from the plasma membrane/endosomes to ER, where it may interact with yet unknown receptors inducing an early and sustained calcium release to the cytoplasm sensitizing cells to mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis.

It has been suggested that synthetic peptides derived from PrP primary sequence may affect calcium homeostasis.33–38 However, these peptides as such have not been observed in PrDs in vivo. Recently, we described the contribution of calcium to the pathogenesis of infectious and familial PrD forms.39 Using purified PrPRES from the brain of scrapie-infected mice we evaluated its impact on ER stress responses and calcium homeostasis. We found that acute exposition of PrPRES of Neuro2a cells induces release of ER-calcium and ER stress, associated with the upregulation of several chaperones and foldases including ERp57, BiP and Grp94. Consistent with these results, cells chronically infected with scrapie prions presented altered ER calcium content. Scrapie infected cells were more susceptible to undergo ER stress-mediated cell death, associated with a stronger UPR activation after exposition of these cells to ER stress-inducing agents.39 We then examined the possible contribution of calcium abnormalities in models of familial PrDs. We generated neuronal cells expressing PrP mutants related to FFI and familial CJD, in addition to a mutant form that is suggested to operate as a misfolded intermediate. Cells expressing mutant PrP were more susceptible to ER stress-inducing agents and presented abnormal ER calcium content.39

It remains to be determined what is the exact mechanism underlying disturbed ER calcium homeostasis and ER stress in PrDs. Interestingly, similar to PrP mutants we observed that a fraction of infectious PrPRES was also locate to the ER.39 One interesting model to test is the possibility that PrP, may interact with proteins that control the levels of calcium like the calcium ATPase SERCA, or the calcium channels IP3 receptors and/or ryanodine receptors as suggested for example in Huntington's disease models.40 Under chronic conditions, this release of calcium may occur slowly, generating in the long term a decrease in the ER steady state calcium levels, generating ER stress. Both, reduction of calcium inside of ER and increase in the cytosol could lead to drastic alterations in protein homeostasis, sensitizing cells to cell death (Fig. 1). In this scenario, the design of small molecules to target calcium handling proteins may represent a novel therapeutic strategy against PrDs and other protein misfolding disorders.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by FONDECYT no. 1100176, Millennium Nucleus no. P07-048-F, FONDAP grant no. 15010006, ICGEB, Alzheimer's Association, Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson's disease (to C.H.), CONICYT Ph.D., fellowship (M.T.); and the NIH grant R01 NS05349 (C.S.).

References

- 1.Matus S, Glimcher LH, Hetz C. Protein folding stress in neurodegenerative diseases: a look into the ER. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2011;23:239–252. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prusiner SB. Prions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:13363–13383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hetz C, Soto C. Protein misfolding and disease: the case of prion disorders. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60:133–143. doi: 10.1007/s000180300009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castilla J, Saa P, Hetz C, Soto C. In vitro generation of infectious scrapie prions. Cell. 2005;121:195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hegde RS, Rane NS. Prion protein trafficking and the development of neurodegeneration. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:337–339. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00143-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yedidia Y, Horonchik L, Tzaban S, Yanai A, Taraboulos A. Proteasomes and ubiquitin are involved in the turnover of the wild-type prion protein. EMBO J. 2001;20:5383–5391. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.19.5383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hetz CA, Soto C. Stressing out the ER: a role of the unfolded protein response in prion-related disorders. Curr Mol Med. 2006;6:37–43. doi: 10.2174/156652406775574578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vey M, Pilkuhn S, Wille H, Nixon R, DeArmond SJ, Smart EJ, et al. Subcellular colocalization of the cellular and scrapie prion proteins in caveolae-like membranous domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14945–14949. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beranger F, Mange A, Goud B, Lehmann S. Stimulation of PrP(C) retrograde transport toward the endoplasmic reticulum increases accumulation of PrP(Sc) in prion-infected cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:38972–38977. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205110200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kristiansen M, Deriziotis P, Dimcheff DE, Jackson GS, Ovaa H, Naumann H, et al. Disease-associated prion protein oligomers inhibit the 26S proteasome. Mol Cell. 2007;26:175–188. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kristiansen M, Messenger MJ, Klohn PC, Brandner S, Wadsworth JD, Collinge J, et al. Disease-related prion protein forms aggresomes in neuronal cells leading to caspase activation and apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:38851–38861. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506600200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taraboulos A, Serban D, Prusiner SB. Scrapie prion proteins accumulate in the cytoplasm of persistently infected cultured cells. J Cell Biol. 1990;110:2117–2132. doi: 10.1083/jcb.110.6.2117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ron D, Walter P. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:519–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hetz C, Lee AH, Gonzalez-Romero D, Thielen P, Castilla J, Soto C, et al. Unfolded protein response transcription factor XBP-1 does not influence prion replication or pathogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:757–762. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711094105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steele AD, Hetz C, Yi CH, Jackson WS, Borkowski AW, Yuan J, et al. Prion pathogenesis is independent of caspase-12. Prion. 2007;1:243–247. doi: 10.4161/pri.1.4.5551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown AR, Rebus S, McKimmie CS, Robertson K, Williams A, Fazakerley JK. Gene expression profiling of the preclinical scrapie-infected hippocampus. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;334:86–95. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.06.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hetz C, Russelakis-Carneiro M, Maundrell K, Castilla J, Soto C. Caspase-12 and endoplasmic reticulum stress mediate neurotoxicity of pathological prion protein. EMBO J. 2003;22:5435–5445. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hetz C, Russelakis-Carneiro M, Walchli S, Carboni S, Vial-Knecht E, Maundrell K, et al. The disulfide isomerase Grp58 is a protective factor against prion neurotoxicity. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2793–2802. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4090-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rane NS, Kang SW, Chakrabarti O, Feigenbaum L, Hegde RS. Reduced translocation of nascent prion protein during ER stress contributes to neurodegeneration. Dev Cell. 2008;15:359–370. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoo BC, Krapfenbauer K, Cairns N, Belay G, Bajo M, Lubec G. Overexpressed protein disulfide isomerase in brains of patients with sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Neurosci Lett. 2002;334:196–200. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)01071-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu K, Wang X, Shi Q, Chen C, Tian C, Li XL, et al. Human prion protein mutants with deleted and inserted octarepeats undergo different pathways to trigger cell apoptosis. J Mol Neurosci. 2010;43:225–234. doi: 10.1007/s12031-010-9387-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Apodaca J, Kim I, Rao H. Cellular tolerance of prion protein PrP in yeast involves proteolysis and the unfolded protein response. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;347:319–326. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.06.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hetz C, Castilla J, Soto C. Perturbation of endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis facilitates prion replication. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:12725–12733. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611909200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orsi A, Fioriti L, Chiesa R, Sitia R. Conditions of endoplasmic reticulum stress favor the accumulation of cytosolic prion protein. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:30431–30438. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605320200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grenier C, Bissonnette C, Volkov L, Roucou X. Molecular morphology and toxicity of cytoplasmic prion protein aggregates in neuronal and non-neuronal cells. J Neurochem. 2006;97:1456–1466. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03837.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma J, Lindquist S. Wild-type PrP and a mutant associated with prion disease are subject to retrograde transport and proteasome degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:14955–14960. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011578098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma J, Lindquist S. Conversion of PrP to a self-perpetuating PrPSc-like conformation in the cytosol. Science. 2002;298:1785–1788. doi: 10.1126/science.1073619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gorlach A, Klappa P, Kietzmann T. The endoplasmic reticulum: folding, calcium homeostasis, signaling and redox control. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:1391–1418. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pozzan T, Rizzuto R, Volpe P, Meldolesi J. Molecular and cellular physiology of intracellular calcium stores. Physiol Rev. 1994;74:595–636. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1994.74.3.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ashby MC, Tepikin AV. ER calcium and the functions of intracellular organelles. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2001;12:11–17. doi: 10.1006/scdb.2000.0212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Corbett EF, Oikawa K, Francois P, Tessier DC, Kay C, Bergeron JJ, et al. Ca2+ regulation of interactions between endoplasmic reticulum chaperones. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:6203–6211. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.10.6203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang HG, Pathan N, Ethell IM, Krajewski S, Yamaguchi Y, Shibasaki F, et al. Ca2+-induced apoptosis through calcineurin dephosphorylation of BAD. Science. 1999;284:339–343. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5412.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agostinho P, Oliveira CR. Involvement of calcineurin in the neurotoxic effects induced by amyloid-beta and prion peptides. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:1189–1196. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ferreiro E, Oliveira CR, Pereira CM. The release of calcium from the endoplasmic reticulum induced by amyloid-beta and prion peptides activates the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;30:331–342. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Florio T, Grimaldi M, Scorziello A, Salmona M, Bugiani O, Tagliavini F, et al. Intracellular calcium rise through L-type calcium channels, as molecular mechanism for prion protein fragment 106–126-induced astroglial proliferation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;228:397–405. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kawahara M, Kuroda Y, Arispe N, Rojas E. Alzheimer's beta-amyloid, human islet amylin and prion protein fragment evoke intracellular free calcium elevations by a common mechanism in a hypothalamic GnRH neuronal cell line. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:14077–14083. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.19.14077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O'Donovan CN, Tobin D, Cotter TG. Prion protein fragment PrP-(106-126) induces apoptosis via mitochondrial disruption in human neuronal SH-SY5Y cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:43516–43523. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103894200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thellung S, Florio T, Villa V, Corsaro A, Arena S, Amico C, et al. Apoptotic cell death and impairment of L-type voltage-sensitive calcium channel activity in rat cerebellar granule cells treated with the prion protein fragment 106–126. Neurobiol Dis. 2000;7:299–309. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2000.0301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Torres M, Castillo K, Armisen R, Stutzin A, Soto C, Hetz C. Prion protein misfolding affects calcium homeostasis and sensitizes cells to endoplasmic reticulum stress. PLoS One. 2010;5:15658. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vidal R, Caballero B, Couve A, Hetz C. Converging pathways in the occurrence of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress in Huntington's disease. Curr Mol Med. 2011;11:1–12. doi: 10.2174/156652411794474419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]