Abstract

Helicases are molecular motor proteins that couple NTP hydrolysis to directional movement along nucleic acids. A class of helicases characterized by their ring-shaped hexameric structures translocate processively and unidirectionally along single stranded (ss) DNA to separate the strands of double-stranded (ds) DNA, aiding both in the initiation and fork progression during DNA replication. These replicative ring-shaped helicases are found from virus to human. We review recent biochemical and structural studies that have expanded our understanding on how hexameric helicases use the NTPase reaction to translocate on ssDNA, unwind dsDNA, and how their physical and functional interactions with the DNA polymerase and primase enzymes coordinate replication of the two strands of dsDNA.

Introduction

The genomic DNA in the cell exists in its energetically favorable double stranded (ds) conformation; however, to access the base coding information during DNA replication, repair, and transcription, the dsDNA needs to be separated into its single stranded (ss) DNA components. Helicases are the molecular motor proteins that perform this mechanical task by coupling the thermodynamically spontaneous NTP hydrolysis reaction to directional movement along nucleic acids. In addition to dsDNA unwinding, helicases perform many other nucleic acid remodeling functions that aid in a wide array of biological processes [1–5]. Given the pivotal role that helicases play in nucleic acid metabolism, it is not surprising that mutations in human genes coding for helicases often lead to chromosome instability that result in various forms of cancer and premature ageing. Viruses often encode their own helicases that play a key role in genome replication and packaging/unpackaging and represent prospective targets for developing antiviral therapy.

The large number of helicases identified presently can be classified into various superfamilies based on their amino acid sequence and conserved helicase motifs[4,6]. Although helicases in the same superfamily share similar structures[7], they may have different biochemical properties, such as their choice of nucleic acid substrate (DNA/RNA) and direction of translocation/unwinding (3'→5' or 5'→3'). Hexameric helicases are distinguished by their ring-shaped structure and the presence of a central channel where the nucleic acid binds. The topological linkage of the helicase ring to the nucleic acid decreases the chances of their complete dissociation, which results in high processivity that is critical for DNA replication, transcription, recombination, and viral genome packaging.

In this review, we discuss the most recent hexameric helicase structures and biochemical studies that allow us to understand how this class of helicases translocates on ssDNA or ssRNA and unwinds dsDNA by coupling the reactions of NTP hydrolysis. The replicative helicases work closely with the DNA polymerase and primase enzymes[8–10]. We discuss how the physical and functional couplings of the helicase with the DNA polymerase as well as the primase modulate their enzymatic activities to bring about timely replication of the two strands of the dsDNA. We focus our discussions on bacteriophage T7, T4, and E. coli systems to illustrate the general principles that will guide us in the understanding of more complex eukaryotic enzymes.

Structure and mechanism of NTPase powered translocation on ssDNA

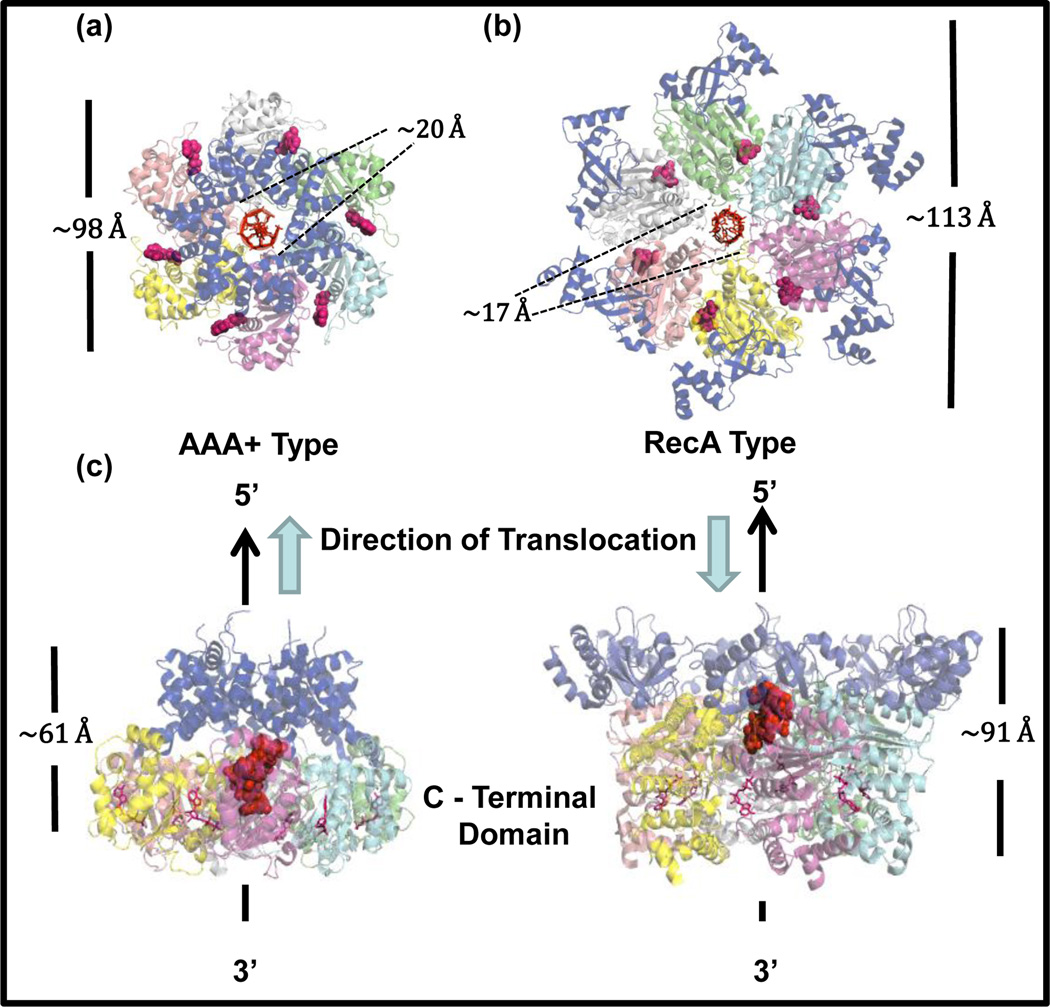

Most hexameric helicases assemble from six identical protein subunits, except for the eukaryotic hexameric helicases that assemble into a hetero-hexamer of Mcm2–7 proteins[11,12]. Electron micrographs and crystal structures of many hexameric helicases are available that show a conserved structure of a ring with an outer diameter of ~120 Ǻ, a long central channel of ~80 Ǻ with an inner diameter of 20–50 Ǻ (Figure 1). The central channel formed by the organization of the six subunits appears to be flexible, which allows hexameric helicases to bind and translocate on both ss and ds nucleic acids. The first structures of the hexameric helicase T7 gp4 bound to dTTP revealed that the NTPase active sites are located at the subunit interfaces[13,14]. This arrangement provided insights into how protein conformational changes from NTP binding and hydrolysis can be transmitted through subunit interfaces to bring about DNA movement. Further detailed mechanistic inferences were made possible by the crystal structure of papilloma virus E1 helicase with ADP and ssDNA bound in the central channel **[15], and more recently by the structure of E coli Rho helicase with ADP․BeF3 and ssRNA bound in the central channel **[16] with both showing extensive structural similarities (Figure 1). These structures have provided a wealth of information on nucleic acid translocation[17], especially because the two helicases move with opposite translocation polarity on ss nucleic acids. The AAA+ family E1 helicase moves along ssDNA in the 3'→5' direction whereas the RecA family Rho helicase moves in the opposite 5'→3' direction. What is surprising is that the ss nucleic acid binds in the central channel with the same polarity in both helicases –the 5’-end of the ss nucleic acid is close to the N-terminal domains in both proteins (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Structure of RecA family and AAA+ family hexameric helicases.

The N-terminal end view of (a) Papillomavirus E1 hexameric helicase (PDB ID: 2GXA) and (b) Rho hexamer (PDB ID: 3ICE). Oligomerization domain of E1 (amino acids 308–378) and the N terminal domain of Rho (amino acids 1–130) are shown in blue. Nucleic acid (DNA for E1 and RNA for Rho) is bound in the central channel of the helicase with its 5’-end oriented towards the N-terminal domain. Each hexamer has 6 nucleotide binding sites at the subunit interfaces. The bound nucleotides (ADP BeF3 in Rho and ADP in E1) are in pink. (c) Side views of E1 (left) and Rho (right). The nucleic acid (in spheres) is in the central channel and its orientation is indicated by the black arrow and Direction of translocation by the thick blue arrows.

One of the most important questions that relates to the mechanism and directionality of translocation by the ring-shaped helicases is the sequence of power strokes that drive the movement of the ring along the nucleic acid strand. Mutant poisoning experiments show severe inhibition of wild-type activity when increasing amount of an inactive mutant is added[18] **[19], **[20]. Such experiments ruled out the random mechanism of NTP firing whereby each subunit independently hydrolyzes NTP to move DNA. The present data support a model where NTP hydrolysis and DNA movement are coordinated among the six subunits.

Rho and E1 crystal structures obtained with ADP․BeF3 (an ATP analog) and ADP, respectively, show that the hexamer is characteristically asymmetric indicating that each subunit interface as well as the NTPase site exists in a unique conformation. This arrangement is consistent with the ordered sequential model proposed from the presteady state kinetic studies of T7 gp4 and Rho wherein each subunit undergoes the NTPase reaction (NTP binding, NTP hydrolysis, Pi release, and NDP release) in an ordered manner around the ring **[19,20]. Thus, at any given time, each subunit would exist in a unique NTP ligation state through coordination in the timing of each step of the NTPase reaction. The presteady state kinetic analysis of T7 gp4 and Rho helicases indicate a phase delay between hydrolysis and Pi release, which results in 2–3 subunits of the hexamer remaining bound to both NDP+Pi **[19,20].

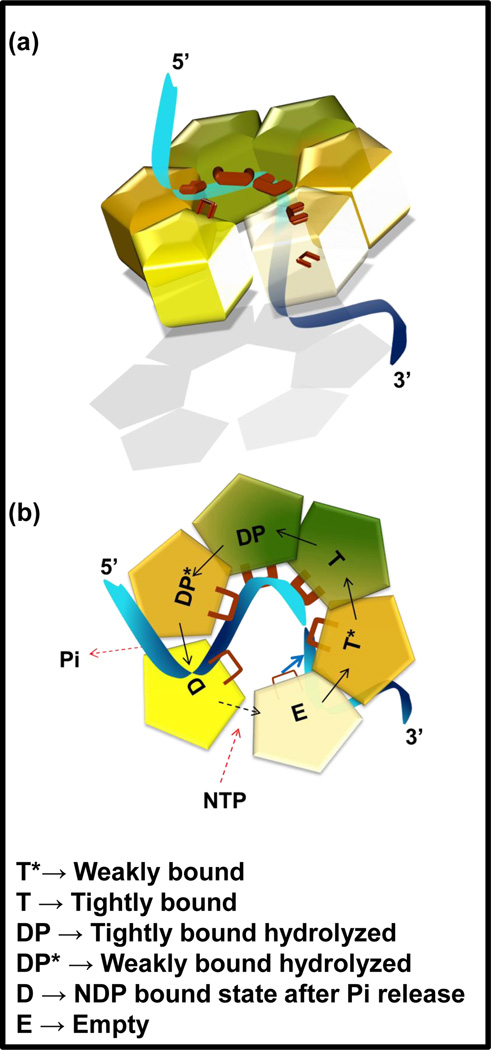

Both biochemical and structural studies are consistent with the following sequence of the NTPase steps: T* (weakly bound NTP-state) → T (tightly bound NTP-state) → DP (tightly bound hydrolyzed state without Pi release) → DP* (weakly bound hydrolyzed state without Pi release) → D (NDP-bound state after Pi release) → E (empty or nucleotide exchange state after NDP release). In the crystal structures of Rho and E1 with ADP․BeF3 and ADP bound, respectively, the distinct states of the active sites are defined by the unique arrangement of the active site amino acids. The ss nucleic acid is bound within the central channel via loops that protrude from each subunit. These loops form a “spiral staircase” in which five consecutive subunits interact with five consecutive nucleotides of the ssDNA in E1 and ssRNA in Rho (Figure 2a). The E and D states bind weakly to the nucleotide as well as to the nucleic acid, the T* and DP* bind with intermediate affinities, and the T and DP states bind with tight affinities. Tight binding of the DNA to the subunits in the T-state and the DP-state is consistent with the protein-DNA binding studies that indicate tight interactions of T7 gp4 and DnaB helicases with ssDNA in the presence of the nonhydrolyzable NTP analog, as well as efficient crosslinking of ssDNA to 1–2 subunits of the hexamer[21–23].

Figure 2. Sequential mechanism of NTP hydrolysis and translocation on single stranded nucleic acid by Rho helicase.

(a) The ss nucleic acid (blue shaded color) is held in place by the DNA binding loops (brown color) projecting out of the hexamer subunits inside the central channel. Five subunits interact with five nucleotides of ss nucleic acid in a spiral staircase fashion. Darker color of subunits and thicker loops indicate tighter interaction with NTP and nucleic acid. (b) Schematic representation of the NTP-ligated states of the subunits in the hexamer during translocation along ss nucleic acid. The solid black arrows indicate the direction of the sequential stages of NTP hydrolysis. In the sequential mechanism shown, the E subunit reels in a nucleotide of the nucleic acid (indicated by solid blue arrow) upon binding a new NTP. At the same time, the D subunit releases a nucleotide of the nucleic acid upon releasing NDP, the T subunit hydrolyzes NTP, and the DP* releases Pi.

Each of the subunits goes through the NTPase reaction steps listed above in a sequential manner around the ring to bring about DNA movement in the central channel. The DNA movement is brought about by the cooperative binding transition of the NTP and the ssDNA nucleotide. In the case of Rho, the E-state subunit at the bottom of the staircase reels in a nucleotide from the 3’-end of ssRNA upon binding NTP and the subunit at the top of the staircase releases an RNA nucleotide (Figure 2b). In case of E1, the E-state subunit at the top of the staircase (near the N-terminal domains) upon NTP binding reels in a nucleotide from the 5’-end of the ssDNA. At the same time, one nucleotide of DNA is released by a subunit at the bottom of the staircase upon release of the hydrolysis product. In this manner, Rho and E1 bind and release nucleotides from opposite sides of the ring to move nucleic acid in opposite directions. In both cases, a single cycle of NTP hydrolysis leads to the movement of one nucleotide of the ss nucleic acid predicting a step size of one nucleotide movement per NTP hydrolyzed. The kinetic pathway of NTP hydrolysis by T7 gp4 and Rho indicate that at low NTP concentration, the slow steps associated with the NTP binding dictate the rate of DNA movement whereas at saturating NTP concentrations, the rate of Pi release dictates the rate of movement **[19,20].

Mechanism of dsDNA unwinding

The ordered sequential mechanism of NTP hydrolysis and movement explains how the hexameric helicase moves along ss nucleic acid. However, to unwind the strands of the dsDNA, the helicase must break the interactions between base pairs that hold the two strands together. Several models of DNA unwinding have been proposed; however, most studies are consistent with the strand exclusion model of unwinding[24–30]. In this model, the hexameric helicase encircles and translocates along one melted strand while excluding the complementary strand from the central channel. The 3'→5' helicase would encircle the 3’-ended strand and exclude the 5’-ended strand whereas the 5'→3' helicase would do the opposite. The strand exclusion mode of DNA binding minimizes immediate reannealing of the DNA strands after they are separated. Many ring-shaped helicases cannot separate the dsDNA in vitro, if the ss-ds junction lacks a noncomplementary ssDNA overhang. In this case, it is proposed that the excluded strand acts as a steric barrier to prevent the helicase from encircling the dsDNA. Whether the excluded strand plays an active role in DNA unwinding is not established. For example, the excluded strand may interact with the outside region of the helicase ring to aid in DNA unwinding by a torsional type mechanism[12] or as recently proposed for the homohexameric MCM helicase, the excluded strand could wrap around the exterior of the protein, stabilizing it in an unwinding mode by protecting the unwound strand and preventing reannealing. [31]

Most ring-shaped helicases rely on loaders to help encircle the DNA[32]. A loader is either a separate protein that interacts with its corresponding helicase and with the DNA (e.g., DnaC for DnaB helicase in E. coli) or helicase’s own specific domain endowed with the loading task (e.g., primase domain in T7 gp4 protein and N-terminal RNA binding domain in Rho). ATP binding/hydrolysis by the loaders is believed to play a crucial part in loading of hexameric helicases. The role of ATPase might be of a gatekeeper at the transition of loading and unwinding. Many eukaryotic hexameric helicases initiate unwinding by first binding to dsDNA at the origin of replication. After origin melting with the help of accessory proteins, these helicases may switch from the dsDNA binding mode to the strand exclusion mode to catalyze replication fork movement.

Hexameric helicases are single-strand translocases and processive translocation on ssDNA has been demonstrated in many helicases [33], *[35]. The hexameric helicases can displace moieties along their path without interacting with them [36,37]. Thus, force production through translocation on ssDNA can be coupled to local base pair separation at the fork junction to bring about dsDNA unwinding. T7 gp4, T4 gp41, E. coli DnaB translocate along ssDNA at a faster rate as compared to their rates of dsDNA strand separation, and moreover the dsDNA strand separation rates depend on the GC content *[38],[39] and on the destabilizing force applied to the unwinding junction in single molecule experiments **[34], *[35,40] (Figure 3b). E.g., T7 gp4 moves with a rate of 130 nt/s along ssDNA at 18°C and its unwinding rate is 3–16 fold slower, depending on the GC content in the dsDNA. Thus, it is harder for the helicase alone to unwind the ds DNA when the two strands have a strong affinity for each other. The dependence of unwinding on DNA stability and force has been explained by insufficient interaction energy of the helicase with the junction base pairs. This raises the question as to whether helicases unwind the strands of the ds DNA by a passive or an active mechanism[41].

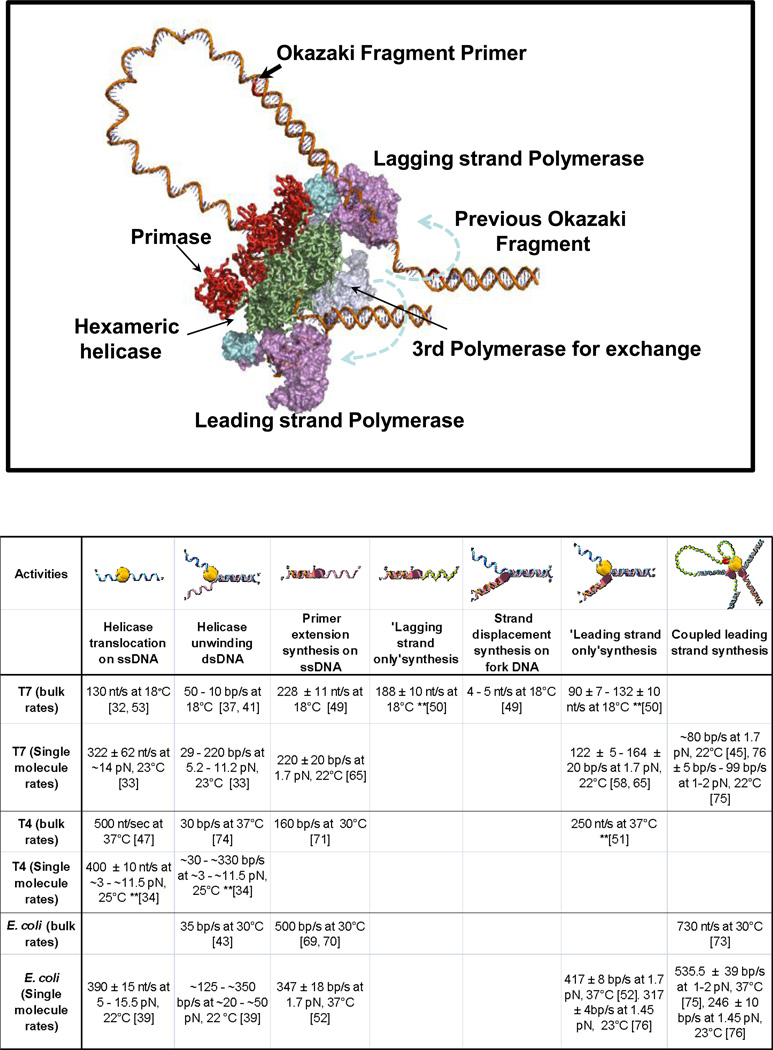

Figure 3. Motors of the replisome: dynamics and interactions.

The replisome is a complex dynamic molecular system which involves a variety of proteins functioning interdependently to ensure efficient synthesis of both leading and lagging strands. A model system of the proteins at the replication fork is depicted using the crystal structures of T7 helicase-primase gp4 (PDB ID: 1Q57) and DNA polymerase gp5 with its processivity factor thioredoxin (PDB ID: 1T7P). The helicase domain is shown in green, primase domain in red, DNA polymerase in purple and thioredoxin in light blue. The 3 rd polymerase proposed by recent studies to be a part of the replisome potentially to increase DNA synthesis processivity or bypass/repair lesions in the DNA, is shown in gray. (b) The rates of the individual motor proteins functioning by themselves or in a complex with other proteins of the replisome.

In the passive mechanism, the helicase translocates along the ssDNA as it is continuously generated by thermal fraying of the dsDNA fork junction, whereas in the active mechanism, the helicase actively disrupts the base pairs at the junction. Typically the free energy of an AT bp is 1.3 kBT and for the GC bp is 2.9 kBT. A passive helicase such as the T4 gp41 has very low destabilization energy of 0.5 kBT/bp *[35] whereas an active helicase such as T7 gp4 and DnaB destabilizes the junction by 1–2 kBT/bp **[34], *[40],[42]. Because 3.4 kBT would be required to achieve the maximal translocation rate, it indicates that T7 gp4 and DnaB unwind by a partially active mechanism. Thus, force production by helicases can vary and might depend on their functions in the cell and by their association with accessory proteins such as the DNA polymerase and primase.

Interactions with the DNA polymerase

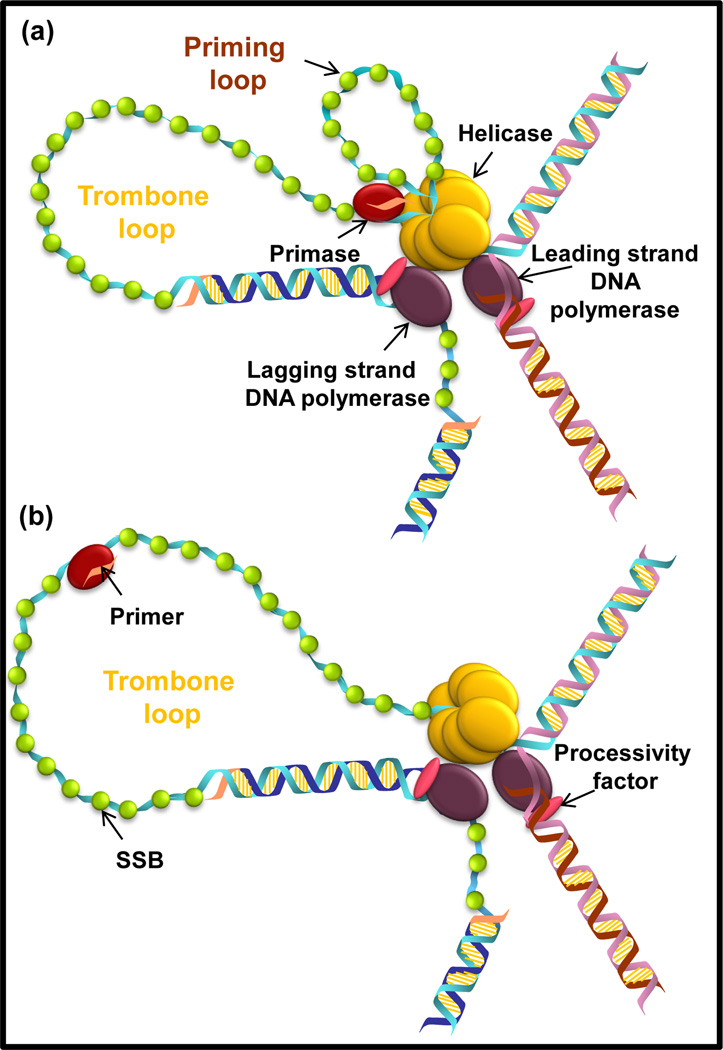

Hexameric helicases play a central role in coordinating leading and lagging strand synthesis (Figure 3a). The replicative helicase interacts with the leading strand polymerase and the primase, and during normal replication where the two strand synthesis are coupled, the helicase also interacts with the lagging strand polymerase. Physical interactions between helicase and polymerase may be direct or indirect. In phage T7, the gp4 helicase interacts directly with the T7 DNA polymerase through the acidic C-terminal tail on the helicase and a basic loop in the DNA polymerase[43]. In the bacterial system, the τ subunit of the clamp loader mediates the interactions between the DnaB helicase and DNA polymerase Pol III[44]. No direct physical interaction has been observed between the phage T4 helicase gp41 and polymerase gp43, but the helicase loader gp59 that interacts with the polymerase, helicase, and primase remains associated with the replication fork[45] and perhaps mediates interactions between the replication proteins; however, this remains to be demonstrated. Physical coupling between leading-lagging strand complexes is demonstrated through recent observations of the replication Trombone loop[45,46] (Figure 3a and 4). Although physically coupled, the two polymerases are not functionally coupled as slowing or blocking lagging strand synthesis does not affect leading strand synthesis [47].

Figure 4. Coupled and uncoupled primosome in the replication machinery.

(a) In the coupled primosome, the primase (in red) is making primer while it is engaged with the leading strand helicase-polymerase. The primase and primer remain bound to the forward moving leading strand replisome until handoff to the lagging polymerase; hence, the nascent ssDNA is looped out into a priming loop. (b) In the uncoupled primosome, the primase dissociates from the leading strand helicase-polymerase after primer synthesis.

Leading strand DNA synthesis requires both physical and functional coupling between the helicase and the leading strand polymerase. The interdependence of the helicase and polymerase is observed both in terms of rate and processivity from studies of T7, T4, E. coli, and human mitochondrial replication proteins[44,48–49], **[50]. A comprehensive list of rates for translocation, unwinding and DNA synthesis is shown in Figure 3b. Both helicase and polymerase are DNA motor proteins, and as individual motors they move efficiently along ssDNA templates. T7 DNA polymerase copies the ssDNA template with rates ~200 nt/s (18°C), and T7 gp4 moves at speeds of 130 nt/s (18°C) along ssDNA[33], **[51]. However, both motors slow down considerably when moving through dsDNA. T7 DNA polymerase cannot efficiently copy the dsDNA by itself **[50], and similarly T7 gp4 unwinds dsDNA with 3–16 fold slower rates depending on the GC content of the dsDNA *[38]. This appears to be a general phenomenon and single molecule studies of T7 gp4, DnaB, and T4 helicases show ~10 times faster translocation on ssDNA as compared to their rates of unwinding dsDNA **[34], *[35,40].

The coupling between helicase and DNA polymerase increases the speed of DNA unwinding-synthesis (Figure 3b). When T7 gp4 is coupled to T7 DNA polymerase, the two motors together move through dsDNA with speeds of ~120 bp/s, which is ~10 times faster than the speed of the helicase alone **[50]. Similar observations have been made in other replication complexes. The DNA unwinding rate by DnaB (30–35 bp/s) is accelerated in the coupled pol III-τ-DnaB complex by 10–20 fold[44], and the unwinding rate of T4 helicase gp41 (30 bp/s) is accelerated ~3 times in the coupled helicase-polymerase system[52]. In addition to the faster speed, the coupled helicase-polymerase is much more processive than the individual motors. The human mitochondrial helicase Twinkle unwinds dsDNA with poor processivity, but the polymerase-helicase can catalyze synthesis of kbp sized dsDNA with a faster rate [49]. The processivity of the leading strand synthesis in E. coli is 8 fold higher than the primer-extension on ssDNA by the DNA polymerase alone [53]. In the absence of the DNA polymerase, T7 gp4 falls off after unwinding ~100 bp on an average *[54] whereas in the presence of the DNA polymerase, it can unwind kbp size DNA **[51]. It is the physical interactions between the helicase and polymerase that increases the processivity as demonstrated in T7 system where the removal of the acidic C-terminal tail of T7 gp4 decreases the unwinding-synthesis processivity[55].

When both motors are moving, the slow motor appears to dictate the speed of DNA unwinding-synthesis. T7 helicase-polymerase moves at the speed limited by the helicase **[50]. Similarly, Pol II and Pol IV slow down fork progression to 1 bp/s and to 10 bp/s, respectively, making DnaB to processively translocate at a speed lower than its measured intrinsic unwinding rate (30 bp/s) [56]. The exact mechanism of functional coupling between helicase and DNA polymerase is not known. Structures of the helicase-polymerase complex are lacking; hence, it is not known how the helicase and polymerase are positioned with respect to each other at the replication fork junction. It is commonly believed that the helicase is the leading motor; thus, the forward steps of the DNA polymerase can increase the helicase’s net forward movement (push) or decrease the helicase’s backward slips (brake). However, it is also possible that the DNA polymerase is the leading motor or that both motors are juxtaposed close to the replication fork junction. When the DNA polymerase is completely blocked as it often happens during replication due to lesions on the DNA, the helicase unwinding becomes uncoupled from the DNA synthesis. The helicase continues to move ahead and unwind the dsDNA, although more slowly at the unassisted rate, creating ss DNA on the leading strand that has been proposed to act as a signal for recruiting the repair machinery. Whether the helicase and polymerase in this situation remain physically coupled is not known.

Recent studies have unraveled interesting dynamic behaviors of the replicating polymerases[9]. DNA polymerases of T4, T7, and E. coli catalyzing leading strand synthesis exchange frequently, in less than one minute, with polymerase molecules from solution *[57,58]. This polymerase exchange process is mediated either by the helicase itself or by the processivity clamp. In T7, the hexameric gp4 helicase loads up additional polymerase molecules via it acidic C-terminal tail and mediates their exchange with the leading strand polymerase, and this has been observed also in real time using fluorescently labeled polymerase *[59]. In T4 and E. coli, active exchange is mediated by the processivity clamp. It is proposed that the dynamic polymerase exchange aids in high DNA synthesis processivity [55] as well as in bypassing or repairing of damaged/blocked DNA without fork collapse. In the latter case, the processivity clamp serves as a molecular “tool belt” and recruits translesion polymerases such as Pol IV and Pol II that exchange with Pol III [56].

Interactions with the primase

During normal DNA replication, the leading strand is copied continuously, while the lagging strand is copied in 1–3 kbp sized Okazaki fragments. Thus, the lagging strand polymerase is continually recycled throughout replication, and the major role of the primase is to supply RNA primers to the recycling polymerase. The primase may also provide primers for restarting leading strand synthesis. In the event of the leading strand polymerase stalling, the E. coli primase DnaG was shown to synthesize RNA primers on the leading strand ahead of a stalled DNA polymerase[60]. It is assumed that leading strand polymerase hops from the blocked site to the new RNA primer site probably by the clamp-clamp loader mechanism as in lagging strand polymerase recycling.

In all cases, the primase is closely associated with the leading strand complex and often complexed with the replicative helicase, under which conditions it makes the RNA primer most efficiently [61]. In T7, the primase and helicase enzymes are fused into one protein in the T7 gp4; and hence, the primase remains physically associated with the leading strand replisome. In T4 and E. coli, the primase is a separate protein that forms a complex with the subunits of the hexameric helicase via its helicase binding domain and hence it can dissociate from the helicase[62]. Up to six primase units can associate with the hexameric helicase[63,64]; however, one or two primase units might be sufficient for primer synthesis. The association of the primase with the helicase greatly increases the priming activity[65]. Conversely, the primase enhances the processivity of the helicase by stabilizing DNA binding and hexamer formation.

Primer synthesis and hand-off to the polymerase are relatively slow processes taking 1–2 seconds which imply that the leading strand synthesis should eventually outrun lagging strand synthesis. However, such uncoupling of synthesis rates of leading and lagging strand during normal replication is not observed. Many solutions to the problem of timely leading and lagging strand synthesis have been proposed. One study has suggested that primer synthesis pauses the T7 replisome[66]. Such strong functional coupling between primase and replisome would provide a solution to timely replication of dsDNA strands; however, two recent studies indicated that the T4 primosome *[67] and T7 replisome **[51] do not pause or slow down when primers are being made. The helicase or the helicase-polymerase continues to unwind the DNA while primers are being made, and when the helicase and primase are physically coupled, the nascent ssDNA forms a priming loop (Figure 4a). The formation of the priming loop is evidence that primers are made independently of ongoing leading and lagging strand synthesis and the newly synthesized primer is kept in close proximity to the replisome for easy handoff to the lagging strand polymerase. By making primers simultaneously with DNA synthesis and hence ahead of time, the delay due to primer synthesis is minimized and keeping the RNA primers in physical proximity to the replicating complex provides a mechanism for efficient use of the primer and hand-off to the polymerase.

Nevertheless, the lagging polymerase has to recycle continually and the problem remains as to how it keeps up with the leading strand polymerase. In addition to solutions such as multiple lagging-strand polymerases working at the same time to complete lagging-strand synthesis[68] or the lagging-strand polymerase jumping to a new primer before completion of the Okazaki fragment thereby leaving gaps[69], recent studies of T7 replication suggests that the leading and lagging strand polymerases can move at different rates **[51]. The leading-strand polymerase moves with a slower overall rate than the lagging-strand polymerase. Although, both strands are copied by polymerases of the same gene product, their kinetic properties can be different depending on their interactions with partner proteins. The leading strand polymerase works with the helicase, and hence its kinetic properties are modified by the helicase, whereas the lagging strand polymerase works by itself, and hence it acts according to its intrinsic kinetic properties. Measurement of DNA synthesis rates using a combination of transient-state kinetics and kinetic modeling methods revealed that the rate of leading strand helicase-polymerase is 30–40% slower than the rate of lagging strand polymerase **[51]. Unless physical coupling between leading-lagging strand polymerase slows the rate of lagging strand polymerase, which is unlikely based on the observations that blocking lagging strand synthesis does not affect leading strand synthesis; the lagging strand polymerase can move a little faster to make the Okazaki fragment sparing enough time to pick up a new primer and initiate another round of Okazaki fragment synthesis.

Future perspectives

Studies of the hexameric helicases in the recent years have provided deeper insights into how the six subunits of the ring coordinate their activities to move single-stranded DNA in the central channel. Such studies need to be extended in the future with structure determinations in the presence of the hydrolysable NTP to catch the helicase subunits in the various NTP-ligation states in the act of binding and hydrolyzing NTP and moving on nucleic acid. Methods that can directly observe NTP hydrolysis and helicase movement in the highest time and spatial resolution will provide the greatest understanding of these molecular machines. From the perspective of understanding how hexameric helicases unwind dsDNA, there is still a lack of a general mechanism that would explain the process at the molecular level and a lack of any structural analysis of hexameric helicases bound to an unwinding substrate. There is very little known about the structure and mechanism of replicative hexameric helicases loading and moving on dsDNA. It is not known how dsDNA interacts with the helicase subunits and if the mechanism of translocation on dsDNA is similar to ssDNA.

Even though helicases are a crucial factor for dsDNA unwinding, they need accessory proteins to carry out their functions efficiently. Hence, studying helicase activities in the context of its interacting partners will define their mechanisms more precisely and provide new insights into DNA replication and reveal how biological motors are coupled. Presently, we are lacking structures of replicative helicases with the accessory partners such as the DNA polymerase and primase bound to the replication fork substrates. Such studies will define the architecture of the polymerase-helicase and polymerase-helicase-primase complexes and provide insights into how the three enzymes of DNA replication are physically and functionally coupled. It is not known how the eukaryotic 3'–5' helicase and the leading strand DNA polymerase both moving on the same strand couple their activities to drive replication fork movement. Similarly, it is not known if the priming loop observed in T7 and T4 systems is a general feature in other replication complexes. The dynamic nature of the helicase-polymerase-primase complex must be defined by physical parameters not only of DNA unwinding and synthesis but those that quantify the periodic changes in protein-DNA and protein-protein interactions as the proteins move to replicate the DNA strands. Such fundamental understanding of the motor proteins of DNA replication is necessary to tease out the timing of events during normal replication and to predict the consequences when replication stalls or when forks collapse. Due to the conserved mechanisms of enzymes of DNA replication, what we learn from one system should be applicable to others. It is an important means of finding the link between the complex human diseases and helicase actions, which in turn would aid in the development of new tools to combat infectious diseases, cancer, and ageing.

Highlights.

The most recent nucleic acid bound structures of two classes of ring-shaped hexameric helicases reveal the mechanism and polarity of translocation along ssDNA

Hexameric helicases unwind dsDNA by an active or a passive mechanism

Replicative helicases mediate physical and functional coupling with the polymerase and primase enzymes that modulates their enzymatic activities

Acknowledgement

We thank past and present members of the Patel lab for their contributions on the work discussed in this review and NIH grant GM55310 for supporting the work on T7 replication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bustamante C, Cheng W, Meija YX. Revisiting the central dogma one molecule at a time. Cell. 2011;144:480–497. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pyle AM. Translocation and unwinding mechanisms of RNA and DNA helicases. Annu Rev Biophys. 2008;37:317–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lohman TM, Tomko EJ, Wu CG. Non-hexameric DNA helicases and translocases: mechanisms and regulation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:391–401. doi: 10.1038/nrm2394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singleton MR, Dillingham MS, Wigley DB. Structure and mechanism of helicases and nucleic acid translocases. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:23–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.052305.115300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel SS, Donmez I. Mechanisms of helicases. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:18265–18268. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R600008200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gorbalenya AE, Koonin EV. Helicases - Amino-Acid-Sequence Comparisons and Structure-Function-Relationships. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 1993;3:419–429. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fairman-Williams ME, Guenther UP, Jankowsky E. SF1 and SF2 helicases: family matters. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2010;20:313–324. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benkovic SJ, Valentine AM, Salinas F. Replisome-mediated DNA replication. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;70:181–208. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Langston LD, Indiani C, O'Donnell M. Whither the replisome: emerging perspectives on the dynamic nature of the DNA replication machinery. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:2686–2691. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.17.9390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamdan SM, Richardson CC. Motors, switches, and contacts in the replisome. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:205–243. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.072407.103248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costa A, Onesti S. Structural biology of MCM helicases. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2009;44:326–342. doi: 10.1080/10409230903186012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patel SS, Picha KM. Structure and function of hexameric helicases. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2000;69:651–697. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singleton MR, Sawaya MR, Ellenberger T, Wigley DB. Crystal structure of T7 gene 4 ring helicase indicates a mechanism for sequential hydrolysis of nucleotides. Cell. 2000;101:589–600. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80871-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sawaya MR, Guo S, Tabor S, Richardson CC, Ellenberger T. Crystal structure of the helicase domain from the replicative helicase-primase of bacteriophage T7. Cell. 1999;99:167–177. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81648-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Enemark EJ, Joshua-Tor L. Mechanism of DNA translocation in a replicative hexameric helicase. Nature. 2006;442:270–275. doi: 10.1038/nature04943. This is the first report of the crystal structure of a ring-shaped 3'–5' hexameric helicase bound to single stranded DNA and six ADP molecules that reveals the coordinated escort mechanism of DNA translocation.

- 16. Thomsen ND, Berger JM. Running in reverse: the structural basis for translocation polarity in hexameric helicases. Cell. 2009;139:523–534. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.043. This paper reports the crystal structure of Rho hexameric helicase bound to single stranded RNA and six ADP․BeF3 and provide further support to the coordinated escort mechanism and compares two helicases of opposite polarity to reveal the molecular basis for the directionality of translocation.

- 17.Patel SS. Structural biology: Steps in the right direction. Nature. 2009;462:581–583. doi: 10.1038/462581a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crampton DJ, Mukherjee S, Richardson CC. DNA-induced switch from independent to sequential dTTP hydrolysis in the bacteriophage T7 DNA helicase. Mol Cell. 2006;21:165–174. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Adelman JL, Jeong YJ, Liao JC, Patel G, Kim DE, Oster G, Patel SS. Mechanochemistry of transcription termination factor Rho. Mol Cell. 2006;22:611–621. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.04.022. The combination of presteady state kinetic analysis and computational modeling of the ATPase steps by Rho reveals 2–3 subunits in the DP-state and supports the sequential model of ATP hydrolysis.

- 20. Liao JC, Jeong YJ, Kim DE, Patel SS, Oster G. Mechanochemistry of t7 DNA helicase. J Mol Biol. 2005;350:452–475. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.04.051. This is the first report of a detailed presteady state kinetic analysis and computational modeling of T7 gp4 hexameric helicase that indicates that all six subunits participate in a sequential dTTP hydrolysis mechanism leading to DNA movement.

- 21.Hingorani MM, Patel SS. Interactions of bacteriophage T7 DNA primase/helicase protein with single-stranded and double-stranded DNAs. Biochemistry. 1993;32:12478–12487. doi: 10.1021/bi00097a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu X, Hingorani MM, Patel SS, Egelman EH. DNA is bound within the central hole to one or two of the six subunits of the T7 DNA helicase. Nature Structural Biology. 1996;3:740–743. doi: 10.1038/nsb0996-740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bujalowski W, Jezewska MJ. Interactions of Escherichia coli primary replicative helicase DnaB protein with single-stranded DNA. The nucleic acid does not wrap around the protein hexamer. Biochemistry. 1995;34:8513–8519. doi: 10.1021/bi00027a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hacker KJ, Johnson KA. A hexameric helicase encircles one DNA strand and excludes the other during DNA unwinding. Biochemistry. 1997;36:14080–14087. doi: 10.1021/bi971644v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahnert P, Patel SS. Asymmetric interactions of hexameric bacteriophage T7 DNA helicase with the 5'- and 3'-tails of the forked DNA substrate. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:32267–32273. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.32267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jezewska MJ, Rajendran S, Bujalowski W. Complex of Escherichia coli primary replicative helicase DnaB protein with a replication fork: recognition and structure. Biochemistry. 1998;37:3116–3136. doi: 10.1021/bi972564u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaplan DL. The 3'-tail of a forked-duplex sterically determines whether one or two DNA strands pass through the central channel of a replication-fork helicase. J Mol Biol. 2000;301:285–299. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaplan DL, Davey MJ, O'Donnell M. Mcm4,6,7 uses a "pump in ring" mechanism to unwind DNA by steric exclusion and actively translocate along a duplex. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:49171–49182. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308074200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galletto R, Jezewska MJ, Bujalowski W. Unzipping mechanism of the double-stranded DNA unwinding by a hexameric helicase: the effect of the 3' arm and the stability of the dsDNA on the unwinding activity of the Escherichia coli DnaB helicase. J Mol Biol. 2004;343:101–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.07.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rothenberg E, Trakselis MA, Bell SD, Ha T. MCM forked substrate specificity involves dynamic interaction with the 5'-tail. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:34229–34234. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706300200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Graham BW, Schauer GD, Leuba SH, Trakselis MA. Steric exclusion and wrapping of the excluded DNA strand occurs along discrete external binding paths during MCM helicase unwinding. Nucleic Acids Research. 2011 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davey MJ, O'Donnell M. Replicative helicase loaders: ring breakers and ring makers. Curr Biol. 2003;13:R594–R596. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00523-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim DE, Narayan M, Patel SS. T7 DNA helicase: a molecular motor that processively and unidirectionally translocates along single-stranded DNA. J Mol Biol. 2002;321:807–819. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00733-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Johnson DS, Bai L, Smith BY, Patel SS, Wang MD. Single-molecule studies reveal dynamics of DNA unwinding by the ring-shaped T7 helicase. Cell. 2007;129:1299–1309. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.038. The single molecule optical trap experiments show that T7 gp4 moves faster on ssDNA and its unwinding rate depends on the dsDNA sequence and destabilizing force applied to the fork junction. Rigorous analysis of the force dependency reveals that T7 gp4 actively displaces the dsDNA strands.

- 35. Lionnet T, Spiering MM, Benkovic SJ, Bensimon D, Croquette V. Real-time observation of bacteriophage T4 gp41 helicase reveals an unwinding mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19790–19795. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709793104. The single molecule magnetic trap experiments measures the translocation rate of T4 helicase on ssDNA and shows that the unwinding rate is force dependent. The data fits to a mechanism whereby T4 helicase unwinds by a passive mechanism.

- 36.Morris PD, Byrd AK, Tackett AJ, Cameron CE, Tanega P, Ott R, Fanning E, Raney KD. Hepatitis C virus NS3 and simian virus 40 T antigen helicases displace streptavidin from 5'-biotinylated oligonucleotides but not from 3'-biotinylated oligonucleotides: evidence for directional bias in translocation on single-stranded DNA. Biochemistry. 2002;41:2372–2378. doi: 10.1021/bi012058b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaplan DL, O'Donnell M. DnaB drives DNA branch migration and dislodges proteins while encircling two DNA strands. Mol Cell. 2002;10:647–657. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00642-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Donmez I, Patel SS. Coupling of DNA unwinding to nucleotide hydrolysis in a ring-shaped helicase. Embo J. 2008;27:1718–1726. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.100. This paper shows that the DNA unwinding rate of T7 gp4 and the corresponsing dTTPase rate decrease with increasing GC content in the dsDNA.

- 39.Galletto R, Jezewska MJ, Bujalowski W. Unzipping mechanism of the double-stranded DNA unwinding by a hexameric helicase: quantitative analysis of the rate of the dsDNA unwinding, processivity and kinetic step-size of the Escherichia coli DnaB helicase using rapid quench-flow method. J Mol Biol. 2004;343:83–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ribeck N, Kaplan DL, Bruck I, Saleh OA. DnaB helicase activity is modulated by DNA geometry and force. Biophys J. 2010;99:2170–2179. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.07.039. This single molecule study shows that DnaB translocates faster on ssDNA and its unwinding rate is dependent on force that supports an active mechanism of unwinding.

- 41.Betterton MD, Julicher F. Opening of nucleic-acid double strands by helicases: active versus passive opening. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2005;71 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.71.011904. 011904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Donmez I, Rajagopal V, Jeong YJ, Patel SS. Nucleic acid unwinding by hepatitis C virus and bacteriophage t7 helicases is sensitive to base pair stability. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:21116–21123. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702136200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee SJ, Marintcheva B, Hamdan SM, Richardson CC. The C-terminal residues of bacteriophage T7 gene 4 helicase-primase coordinate helicase and DNA polymerase activities. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:25841–25849. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604602200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim S, Dallmann HG, McHenry CS, Marians KJ. Coupling of a replicative polymerase and helicase: a tau-DnaB interaction mediates rapid replication fork movement. Cell. 1996;84:643–650. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nossal NG, Makhov AM, Chastain PD, 2nd, Jones CE, Griffith JD. Architecture of the bacteriophage T4 replication complex revealed with nanoscale biopointers. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:1098–1108. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606772200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hamdan SM, Loparo JJ, Takahashi M, Richardson CC, van Oijen AM. Dynamics of DNA replication loops reveal temporal control of lagging-strand synthesis. Nature. 2009;457:336–339. doi: 10.1038/nature07512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McInerney P, O'Donnell M. Functional uncoupling of twin polymerases: mechanism of polymerase dissociation from a lagging-strand block. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:21543–21551. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401649200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dong F, Weitzel SE, von Hippel PH. A coupled complex of T4 DNA replication helicase (gp41) and polymerase (gp43) can perform rapid and processive DNA strand-displacement synthesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93:14456–14461. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Korhonen JA, Pham XH, Pellegrini M, Falkenberg M. Reconstitution of a minimal mtDNA replisome in vitro. EMBO J. 2004;23:2423–2429. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Stano NM, Jeong YJ, Donmez I, Tummalapalli P, Levin MK, Patel SS. DNA synthesis provides the driving force to accelerate DNA unwinding by a helicase. Nature. 2005;435:370–373. doi: 10.1038/nature03615. This study shows that the unwinding rate of T7 gp4 is accelerated by the DNA synthesis activity of the DNA polymerase

- 51. Pandey M, Syed S, Donmez I, Patel G, Ha T, Patel SS. Coordinating DNA replication by means of priming loop and differential synthesis rate. Nature. 2009;462:940–943. doi: 10.1038/nature08611. This paper shows that primer synthesis by T7 gp4 does not slow the T7 replisome and provides evidence for a priming loop. The study shows that the lagging DNA polymerase moves faster than the leading helicase-polymerase complex.

- 52.Delagoutte E, von Hippel PH. Molecular mechanisms of the functional coupling of the helicase (gp41) and polymerase (gp43) of bacteriophage T4 within the DNA replication fork. Biochemistry. 2001;40:4459–4477. doi: 10.1021/bi001306l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tanner NA, Hamdan SM, Jergic S, Loscha KV, Schaeffer PM, Dixon NE, van Oijen AM. Single-molecule studies of fork dynamics in Escherichia coli DNA replication. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:170–176. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Jeong YJ, Levin MK, Patel SS. The DNA-unwinding mechanism of the ring helicase of bacteriophage T7. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:7264–7269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400372101. Epub 2004 May 7263. This paper shows that T7 gp4 moves at a slower speed when unwinding dsDNA as compared to moving on ssDNA.

- 55.Hamdan SM, Johnson DE, Tanner NA, Lee JB, Qimron U, Tabor S, van Oijen AM, Richardson CC. Dynamic DNA helicase-DNA polymerase interactions assure processive replication fork movement. Mol Cell. 2007;27:539–549. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Indiani C, Langston LD, Yurieva O, Goodman MF, O'Donnell M. Translesion DNA polymerases remodel the replisome and alter the speed of the replicative helicase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:6031–6038. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901403106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Yang J, Zhuang Z, Roccasecca RM, Trakselis MA, Benkovic SJ. The dynamic processivity of the T4 DNA polymerase during replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:8289–8294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402625101. This paper shows that the T4 DNA polymerase exchanges frequently with polymerase in solution during processive replication demonstrating the dynamic nature of the replisome.

- 58. Johnson DE, Takahashi M, Hamdan SM, Lee SJ, Richardson CC. Exchange of DNA polymerases at the replication fork of bacteriophage T7. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:5312–5317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701062104. This paper shows the dynamic nature of the polymerase in the T7 replisome.

- 59. Loparo JJ, Kulczyk AW, Richardson CC, van Oijen AM. From the Cover: Simultaneous single-molecule measurements of phage T7 replisome composition and function reveal the mechanism of polymerase exchange. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:3584–3589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018824108. This paper shows polymerase exhange in real time under single molecule conditions.

- 60.Heller RC, Marians KJ. Replication fork reactivation downstream of a blocked nascent leading strand. Nature. 2006;439:557–562. doi: 10.1038/nature04329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Corn JE, Pelton JG, Berger JM. Identification of a DNA primase template tracking site redefines the geometry of primer synthesis. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:163–169. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang G, Klein MG, Tokonzaba E, Zhang Y, Holden LG, Chen XS. The structure of a DnaB-family replicative helicase and its interactions with primase. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:94–100. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yang J, Xi J, Zhuang Z, Benkovic SJ. The oligomeric T4 primase is the functional form during replication. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:25416–25423. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501847200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Norcum MT, Warrington JA, Spiering MM, Ishmael FT, Trakselis MA, Benkovic SJ. Architecture of the bacteriophage T4 primosome: electron microscopy studies of helicase (gp41) and primase (gp61) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:3623–3626. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500713102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Frick DN, Richardson CC. DNA primases. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;70:39–80. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee JB, Hite RK, Hamdan SM, Xie XS, Richardson CC, van Oijen AM. DNA primase acts as a molecular brake in DNA replication. Nature. 2006;439:621–624. doi: 10.1038/nature04317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Manosas M, Spiering MM, Zhuang Z, Benkovic SJ, Croquette V. Coupling DNA unwinding activity with primer synthesis in the bacteriophage T4 primosome. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:904–912. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.236. The single molecule experiments show that primer synthesis does not slow or pause the T4 helicase, and when the primase-helicase are physically coupled, primer synthesis and helicase unwinding result in a priming loop.

- 68.McInerney P, Johnson A, Katz F, O'Donnell M. Characterization of a triple DNA polymerase replisome. Mol Cell. 2007;27:527–538. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yang J, Nelson SW, Benkovic SJ. The control mechanism for lagging strand polymerase recycling during bacteriophage T4 DNA replication. Mol Cell. 2006;21:153–164. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.O'Donnell ME, Kornberg A. Dynamics of DNA polymerase III holoenzyme of Escherichia coli in replication of a multiprimed template. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:12875–12883. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Studwell PS, O'Donnell M. Processive replication is contingent on the exonuclease subunit of DNA polymerase III holoenzyme. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:1171–1178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Spacciapoli P, Nossal NG. Interaction of DNA polymerase and DNA helicase within the bacteriophage T4 DNA replication complex. Leading strand synthesis by the T4 DNA polymerase mutant A737V (tsL141) requires the T4 gene 59 helicase assembly protein. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:447–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.DeLano WL. San Carlos, CA, USA: DeLano Scientific; 2002. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. Edited by; [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mok M, Marians KJ. The Escherichia coli preprimosome and DNA B helicase can form replication forks that move at the same rate. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:16644–16654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Raney KD, Carver TE, Benkovic SJ. Stoichiometry and DNA unwinding by the bacteriophage T4 41:59 helicase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:14074–14081. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.24.14074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tanner NA, van Oijen AM. Single-molecule observation of prokaryotic DNA replication. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;521:397–410. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-815-7_22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yao NY, Georgescu RE, Finkelstein J, O'Donnell ME. Single-molecule analysis reveals that the lagging strand increases replisome processivity but slows replication fork progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:13236–13241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906157106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]