Abstract

Catalytically generated acyl azoliums I and their α,β-unsaturated counterparts II are thought to be key reactive intermediates in a rapidly growing number of transformations promoted by N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) catalysts.[1] Acyl azoliums are invoked in the postulated catalytic cycles of nearly all of the new NHC-catalyzed reactions of α-functionalized aldehydes reported since 2004, in which they are generally assumed to possess the reactivity of an activated carboxylic acid, that is, analogous to an activated ester.[2] In NHC-catalyzed processes, they are most often obtained through internal redox reactions of functionalized aldehydes but have also been prepared by oxidations of the Breslow intermediates[3] or additions to ketenes.[4] Acyl azoliums I are important intermediates in thiamine pyrophosphate (ThPP) dependent enzymatic reactions.[5] Townsend et al. have recently proposed that unsaturated acyl azolium III is the key intermediate in clavulanic acid biosynthesis;[6] despite careful efforts, III or its analogues II have never been characterized or independently synthesized. Here, we document the observation and characterization of α,β-unsaturated acyl azoliums 1 and 2 (Scheme 1) and demonstrate that their corresponding hemiacetals (1′ and 2”) are the kinetically important intermediates in both their acylation and annulation reactions.

Keywords: acyl azolium, N-heterocyclic carbenes, organocatalysis, reaction mechanisms, redox reactions

Simple acyl azoliums prepared under stoichiometric conditions were extensively studied in a seminal work by Breslow[7] and continued by Daigo,[8] White and Ingraham,[9] Bruice,[10] Lienhard,[11] and Owen.[12] These investigations revealed the unique and rich chemistry of acyl azoliums, including their remarkable reluctance to acylate amines[12, 13] and high preference for reactions with water or alcohols. Despite the more than 120 publications since 2004 that feature acyl azoliums, including the rediscovery of their unusual chemoselectivity, there have been no reports of the isolation, detection, or properties of novel acyl azoliums thought to be generated under catalytic conditions.[14]

Even at high catalyst loadings, most NHC-catalyzed reactions do not give any detectable intermediates that can be observed with conventional techniques such as UV, IR, NMR spectroscopy,[15] or MS methods.[16] For example, no intermediates could be observed during the redox esterification of cinnamaldehyde, even when the reaction was run with high catalyst loadings or in the absence of base to ensure slow reaction. This is consistent with NMR studies of the redox esterification of ynals by Zeitler, in which the postulated α,β-unsaturated acyl azolium II was not observed.[17]

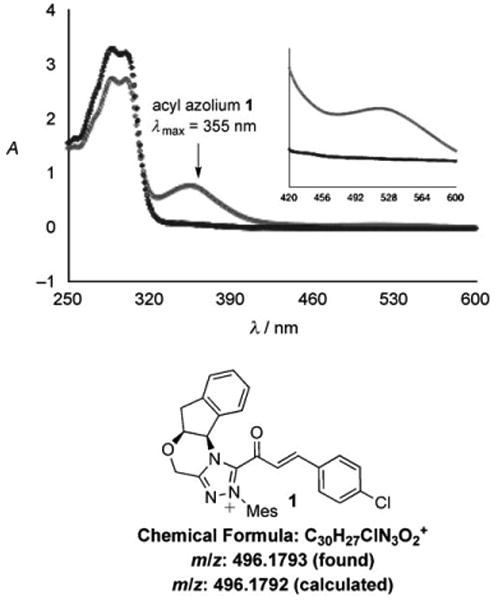

Our recent studies of reactions of ynals catalyzed by azolium salts revealed that the rate-limiting step of the catalytic cycle occurs after the formation of the acyl azolium.[18] These findings strongly suggested that generation of substantial amounts of the α,β-unsaturated acyl azolium intermediate should be possible in the absence of a nucleophile. Careful preparation of a mixture of triazolium 3 and para-chlorophenyl ynal 4 in anhydrous CDCl3 gives a clear solution (Figure 1). Upon addition of NaOAc, the solution rapidly becomes yellow, and turns deep red within 20 minutes. The color change was monitored by UV/Vis spectroscopy, and we observed a maximum absorption at 355 nm, with a significantly smaller absorption at 520 nm, for the solution containing acyl azolium 1 (Figure 2). Townsend et al. have speculated that the related protein-bound species III (Scheme 1) has a characteristic UV/Vis absorption at 310– 320 nm.[6a] Our mixture was further investigated by electrospray ionization–high resolution mass spectrometry (ESI-HRMS), which verified the molecular formula of 1 (Figure 2).

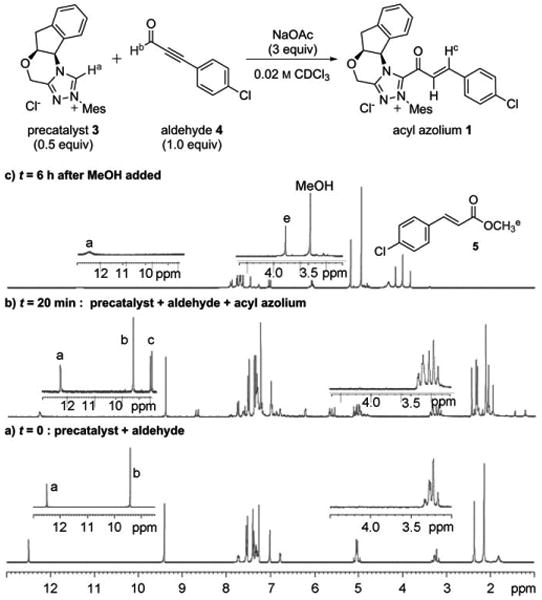

Figure 1.

1H NMR investigation of α,β-unsaturated acyl azolium 1 generated from 3 and 4, and its methanolysis to 5 (the labeled H atoms correlate to the indicated signals in the spectra).

Figure 2.

UV/Vis and ESI-HRMS characterizations of 1. Black: precatalyst + aldehyde; gray: acyl azolium.

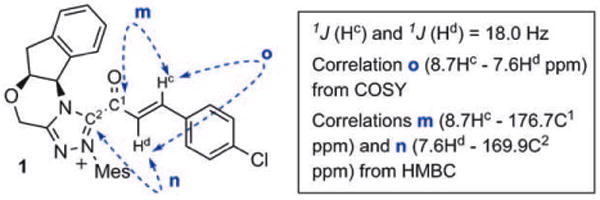

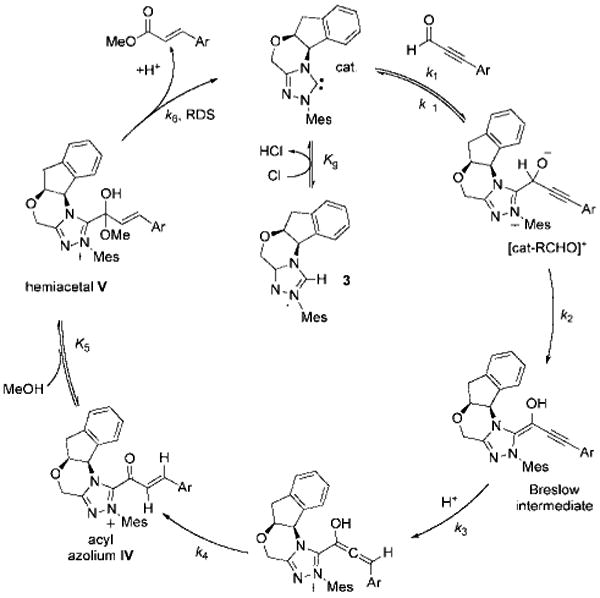

Scheme 1.

Various acyl azoliums and the hemiacetals.

To confirm the formation of 1, the reaction was monitored by 1H NMR spectroscopy. Figure 1 shows the 1H NMR spectra of the region from δ = 1.0–13.0 ppm before (Figure 1a) and after (Figure 1b) treatment of the mixture of azolium 3 and aldehyde 4 with NaOAc. A new product, characterized by doublets at δ = 8.7 ppm (1J =18.0 Hz) and at δ = 7.6 ppm (1J = 18.0 Hz), which is consistent with the expected acyl azolium 1, was detected and grew in intensity over time, reaching a maximum of 30% conversion after about 40 minutes. This new product immediately disappeared upon the addition of MeOH (Figure 1c), cleanly forming the corresponding unsaturated ester 5 and regenerating the protonated triazolium 3 (C-2 proton peak at δ = 12.1 ppm) [19]

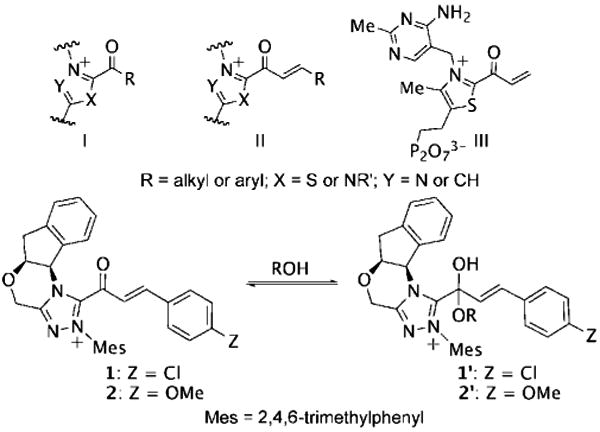

Although this solution could be filtered away from undissolved NaOAc or stored for several hours in the NMR tube, acyl azolium 1 was exceedingly prone to hydrolysis to give para-chlorocinnamic acid; all attempts to isolate 1 in pure form were unsuccessful. However, this intermediate was successfully characterized by COSY, HSQC, and HMBC NMR experiments that were performed on the mixture (see the Supporting Information for spectra and details). Correlation spectroscopy (Figure 3) clearly showed the bond between the acyl group containing an α,β-unsaturated moiety and the triazolium, and ruled out a triazole adduct, which we had previously observed in prior attempts at detecting catalytically generated acyl azoliums with non-anhydrous conditions.[20] 1H NMR experiments were also repeated with para-methoxyphenyl ynal, which led to the formation of acyl azolium 2 with higher conversion (about 50%) relative to that of the aldehyde, but was much more susceptible to hydrolysis (see the Supporting Information).

Figure 3.

Key NMR correlation assignments of acyl azolium 1.

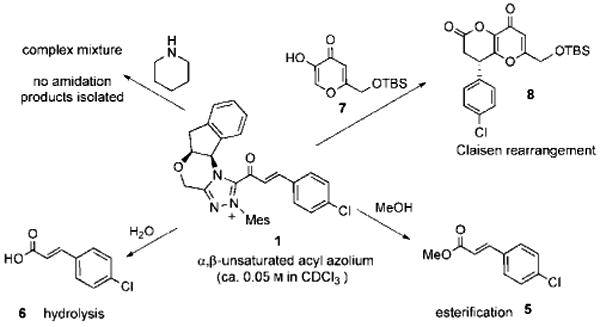

The reactivity of 1, generated in this pseudo-stoichiometric fashion, paralleled the chemistry observed under catalytic conditions (Scheme 2). It reacts instantaneously with water or MeOH to give acid 6 or ester 5, but only a complex, unidentifiable mixture was obtained when 1 was treated with piperidine, an observation consistent with the known chemistry of saturated acyl azoliums and the reluctance of NHC-catalyzed acylations to deliver amide products in the absence of a suitable co-catalyst.[8, 12, 13] The addition of the kojic acid derivative 7 gives annulation product 8 through a mechanism that we believed to be a Coates–Claisen rearrangement from a hemiacetal intermediate (Scheme 3). Very recent related works by Lupton,[21] Xiao,[22] and Studer,[23] however, invoked a direct 1,4-addition of a nucleophile to the α,β-unsaturated acyl azolium.

Scheme 2.

Reactions of a catalytically generated acyl azolium with various nucleophiles.

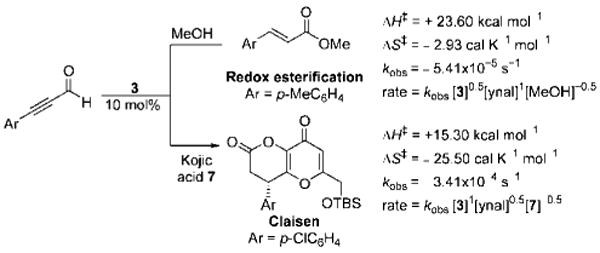

Scheme 3.

Activation parameters, rate constants, and rate laws comparison between NHC-catalyzed redox and Claisen reactions.

With the role of the acyl azolium 1 in both the annulation and acylation chemistry established, we sought to further clarify the mechanistic pathways and chemical properties of α,β-unsaturated acyl azoliums by kinetic investigations. In NHC-catalyzed reactions, kinetic studies are often complicated by the complex reaction mechanism and catalyst inhibition events.[15c] Our recent finding that ynals are sufficiently reactive under NHC-catalyzed reactions in the absence of added base[24] simplified the reaction systems and allowed determination of the rate laws and activation parameters for both the esterification and annulation pathways.

This observed rate equation of the redox esterifications reaction is first order in aldehyde, partial order in the triazolium precatalyst, and partial negative order in MeOH (Scheme 3). The negative order in the nucleophile is initially surprising as we had expected that turnover of the acyl azolium to the ester and the NHC would be the rate-determining step. The negative order could be attributed to catalyst inhibition events. The inhibitory effects of the nucleophile were also observed even in the presence of base; the exact nature of this inhibition is not entirely clear.[25] Nonetheless, we were able to rationalize this observed partial rate orders with the derived rate law (see the Supporting Information). From the experimental rate law, we performed an Eyring analysis, which revealed an activation enthalpy (ΔH⧧) of +23.60 kcal mol−1 and an activation entropy (ΔS⧧) of −2.93 calK−1 mol−1 for the redox esterification reaction.[26] These activation parameters can be contrasted to those of our recent studies on Coates–Claisen reactions[27] of ynals and enols, in which a large negative ΔS⧧, a lower ΔH⧧, and higher reaction rates with electron-deficient ynals were observed (Scheme 3).

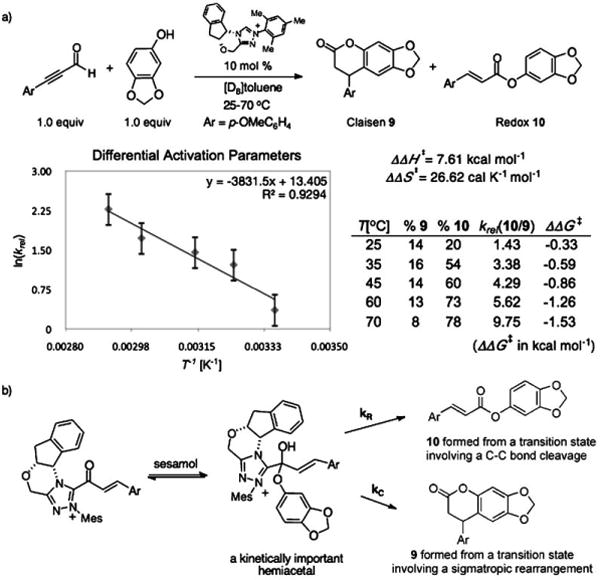

With the role of α,β-unsaturated acyl azolium in the catalytic cycle involving 3 and ynals established, we postulated that the mode of reactivity of NHC-catalyzed reactions of ynals and nucleophilic partner is governed by the pathways available to the corresponding hemiacetal (1′ or 2′) derived from the α,β-unsaturated acyl azolium (1 or 2). To investigate this hypothesis, we undertook the measurement of the difference in the activation parameters (ΔΔH⧧ and ΔΔS⧧)[28] between the Claisen and the redox reactions from the reaction of an ynal with sesamol—a reactant that could undergo both reactions (Scheme 4). We measured a ΔΔH⧧ of 7.61 kcal mol−1 and a ΔΔS⧧ of 26.62 calK−1mol−1 from an Eyring analysis of the product ratio (krel = %10/%9) at five temperatures (see the Supporting Information). These values parallel the data obtained from the rate measurements of the independent processes (Scheme 3) and substantiates our postulate for the role of the kinetically important hemiacetal in the catalytic cycle of both the annulation and esterification reactions. The activation parameters of the competing processes arising for the same hemiacetal intermediate determine the reaction outcome.

Scheme 4.

a) Differential activation parameters measurement from a competition experiment and b) the mechanistic rationale.

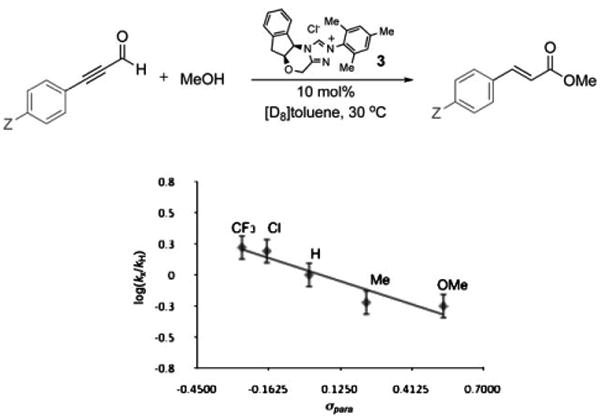

Confirmation of the involvement of hemiacetal V as the final intermediate in the catalytic cycle of the esterification reaction was obtained by linear free-energy relationship analysis.[29] The Hammett plot revealed that electron-rich ynals underwent esterification faster than their more electrophilic counterparts (Figure 4), an observation consistent with a mechanism featuring the breakdown of hemiacetal V as the rate-limiting step in the catalytic cycle (Scheme 5). This intermediate, which we cannot detect, must be in rapid equilibrium with unsaturated acyl azolium IV (i.e. the keto form). Although the equilibrium favors the α,β-unsaturated acyl azolium, the reaction is governed by the kinetic profile of the pathways available to the hemiacetal. Electron-with-drawing groups on the acyl azolium stabilize the hemiacetal and decrease the rate of ester formation. This is consistent with the negative ρ value (albeit small) from the Hammett plot for redox esterification reactions (Figure 4), as well as the previous observation that electron-deficient ynals underwent faster Claisen reaction as these compounds have a higher proportion of the hemiacetal intermediate required for the Claisen rearrangement. This finding also corresponds with the studies of Breslow,[7] Daigo,[8] and Owen,[12] who have studied the reactions of simpler acyl azoliums generated under stoichiometric conditions and found the hemiacetal to be kinetically relevant. Our work demonstrates that the unusual reactivities and kinetics observed under catalytic conditions are governed by the unique properties of the catalytically generated α,β-unsaturated acyl azoliums rather than by any of the prior C–C bond formations or protonation steps[30] involved in its formation.

Figure 4.

Linear free-energy relationship (Hammett study) for NHC-catalyzed redox reaction with para-substituted ynals: ρ = − 0.69 (Z = CF3, Cl, H, Me, or OMe as indicated in the plot). γ= −0.6901 x+0.0326, R2= 0.903.

Scheme 5.

Breakdown of hemiacetal V is the rate-limiting step in NHC-catalyzed redox esterifications of ynals.

In summary, we have successfully generated and characterized the acyl azolium intermediates key to the reactions of N-heterocyclic carbenes and α-functionalized aldehydes. The confirmation that this intermediate is involved in both NHC-catalyzed acylation and annulation reactions has allowed us to demonstrate that a common intermediate, hemiacetal V, is the kinetically important species in both of these processes. These studies reveal the origin of the unique reactivities and selectivities observed in NHC-catalyzed reactions and confirm that NHC-catalyzed annulation reactions of α,β-unsaturated acyl azoliums proceed through a Coates–Claisen reaction rather than a direct Michael addition. Our kinetics investigations provide a rate law (see the Supporting Information) that rationalizes the observed kinetics of both the esterifications and annulation pathways and considers the catalyst generation and inhibition processes that are the origin of the unexpected rate orders in the nucleophiles. These observations will serve as a guideline for future mechanistic investigations and identification of new reactions proceeding through catalytically generated acyl azoliums.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

We are grateful to NIGMS (National Institutes of Health, GM-079339), the National Science Foundation (CHE-0449587), Bristol Myers Squibb, and ETH Zurich for support of this research. We thank Darko Santrac for a preliminary study, and NMR and MS services (ETHZ) for spectroscopic data.

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/anie.201005352.

Contributor Information

Jessada Mahatthananchai, Laboratory for Organic Chemistry, Department of Chemistry and Applied Biosciences, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) Zurich, Wolfgang-Pauli-Strasse 10, 8093 Zurich (Switzerland).

Dr. Pinguan Zheng, Department of Chemistry, University of Pennsylvania, 231 South 34th Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104 (USA)

Prof. Dr. Jeffrey W. Bode, Laboratory for Organic Chemistry, Department of Chemistry and Applied Biosciences, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) Zurich, Wolfgang-Pauli-Strasse 10, 8093 Zurich (Switzerland).

References

- 1.a) Moore JL, Rovis T. In: Topics in Current Chemistry. List B, editor. Vol. 291. Springer; Berlin: 2009. pp. 77–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Enders D, Niemeier O, Henseler A. Chem Rev. 2007;107:5606–5655. doi: 10.1021/cr068372z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Zeitler K. Angew Chem. 2005;117:7674–7678. [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:7506–7510. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Enders D, Balensiefer T. Acc Chem Res. 2004;37:534–541. doi: 10.1021/ar030050j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Chiang PC, Bode JW. In: N-Heterocyclic Carbenes: From Laboratory Curiosities to Efficient Synthetic Tools. Díez-González S, editor. Royal Society of Chemistry; Cambridge: 2010. pp. 399–435. [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Sohn SS, Rosen EL, Bode JW. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:14370–14371. doi: 10.1021/ja044714b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Reynolds NT, Read de Alaniz J, Rovis T. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:9518–9519. doi: 10.1021/ja046991o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Chow KYK, Bode JW. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:8126–8127. doi: 10.1021/ja047407e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Burstein C, Glorius F. Angew Chem. 2004;116:6331–6334. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:6205–6208. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Guin J, De Sarkar S, Grimme S, Studer A. Angew Chem. 2008;120:8855–8858. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:8727–8730. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Maki BE, Chan A, Phillips EM, Scheidt KA. Org Lett. 2007;9:371–374. doi: 10.1021/ol062940f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Inoue H, Higashiura K. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1980:549–550. [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Zhang YR, He L, Wu X, Shao PL, Ye S. Org Lett. 2008;10:277–280. doi: 10.1021/ol702759b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Duguet N, Campbell CD, Slawin AMZ, Smith AD. Org Biomol Chem. 2008;6:1108–1113. doi: 10.1039/b800857b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Wang XN, Lv H, Huang XL, Ye S. Org Biomol Chem. 2009;7:346–350. doi: 10.1039/b815139c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Kluger R, Tittmann K. Chem Rev. 2008;108:1797–1833. doi: 10.1021/cr068444m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Frank R, Leeper F, Luisi B. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:892–905. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-6423-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Merski M, Townsend CA. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:15750–15751. doi: 10.1021/ja076704r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Khaleeli N, Li R, Townsend CA. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:9223–9224. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breslow R, McNelis E. J Am Chem Soc. 1960;82:2394–2395. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daigo K, Reed LJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1962;84:659–662. [Google Scholar]

- 9.White FG, Ingraham LL. J Am Chem Soc. 1962;84:3109–3111. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruice TC, Kundu NG. J Am Chem Soc. 1966;88:4097–4098. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lienhard GE. J Am Chem Soc. 1966;88:5642–5649. doi: 10.1021/ja00969a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.a) Owen TC, Richards A. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:2520–2521. [Google Scholar]; b) Owen TC, Harris JN. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:6136–6137. [Google Scholar]

- 13.a) Movassaghi M, Schmidt MA. Org Lett. 2005;7:2453–2456. doi: 10.1021/ol050773y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Bode JW, Sohn SS. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:13798–13799. doi: 10.1021/ja0768136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Vora HU, Rovis T. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:13796–13797. doi: 10.1021/ja0764052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) De Sarkar S, Grimme S, Studer A. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:1190–1191. doi: 10.1021/ja910540j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.a) Grasa GA, Kissling RM, Nolan SP. Org Lett. 2002;4:3583–3586. doi: 10.1021/ol0264760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Sohn SS, Bode JW. Org Lett. 2005;7:3873–3876. doi: 10.1021/ol051269w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) He M, Bode JW. Org Lett. 2005;7:3131–3134. doi: 10.1021/ol051234w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Sohn SS, Bode JW. Angew Chem. 2006;118:6167–6170. [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:6021–6024. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Suzuki Y, Muramatsu K, Yamauchi K, Morie Y, Sato M. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:302–310. [Google Scholar]; f) Burstein C, Tschan S, Xie X, Glorius F. Synthesis. 2006:2418–2439. [Google Scholar]; g) Chiang PC, Kim Y, Bode JW. Chem Commun. 2009:4566–4568. doi: 10.1039/b909360e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Lathrop SP, Rovis T. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:13628–13630. doi: 10.1021/ja905342e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Maki BE, Chan A, Phillips EM, Scheidt KA. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:3102–3109. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2008.10.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j) De Sarkar S, Studer A. Org Lett. 2010;12:1992–1995. doi: 10.1021/ol1004643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Breslow R, Kim R. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:699–702.Chen YT, Barletta GL, Haghjoo K, Cheng JT, Jordan F. J Org Chem. 1994;59:7714–7722.White MJ, Leeper FJ. J Org Chem. 2001;66:5124–5131. doi: 10.1021/jo010244h.Pignataro L, Papalia T, Slawin AMZ, Goldup SM. Org Lett. 2009;11:1643–1646. doi: 10.1021/ol900257t. e) a recent NMR study of the Breslow intermediate revealed a structure other than that expected and commonly formulated: Berkessel A, Elfert S, Etzenbach-Effers K, Teles JH. Angew Chem. 2010;122:7063–7063. doi: 10.1002/anie.200907275.Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:7120–7124. doi: 10.1002/anie.200907275.

- 16.Schrader W, Handayani PP, Burstein C, Glorius F. Chem Commun. 2007:716–718. doi: 10.1039/b613862d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zeitler first invoked the intermediacy of α,β-unsaturated acyl azoliums in the NHC-catalyzed redox esterification of ynals to give (E)-α,β-unsaturated esters. Zeitler K. Org Lett. 2006;8:637–640. doi: 10.1021/ol052826h.

- 18.Our recently reported NHC-catalyzed Coates–Claisen reaction also features α,β-unsaturated acyl azoliums as important intermediate in the catalytic cyle. Kaeobamrung J, Mahatthananchai J, Zheng P, Bode JW. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:8810–8812. doi: 10.1021/ja103631u.

- 19.a) Harris TK, Washabaugh MW. Biochemistry. 1995;34:14001–14011. doi: 10.1021/bi00043a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Harris TK, Washabaugh MW. Biochemistry. 1995;34:13994–14000. doi: 10.1021/bi00043a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Washabaugh MW, Jencks WP. Biochemistry. 1988;27:5044–5053. doi: 10.1021/bi00414a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carboxylic acids appear to form adducts with triazolium salt 3 through an addition to C-2. This is similar to the behavior of other triazolium salts, see: Enders D, Breuer K, Raabe G, Runsink J, Teles JH, Melder JP, Ebel K, Brode S. Angew Chem. 1995;107:1119–1122.Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1995;34:1021–1023.Vora HU, Rovis T. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:2860–2861. doi: 10.1021/ja910281s.. The formation of the carboxylic acid is suppressed by employing activated molecular sieves

- 21.Ryan SJ, Candish L, Lupton DW. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:14176–14177. doi: 10.1021/ja905501z.; b) this processes was characterized as a rearrangement in a most recent report: Candish L, Lupton DW. Org Lett. 2010;12:4836–4839. doi: 10.1021/ol101983h.

- 22.Zhu ZQ, Xiao JC. Adv Synth Catal. 2010;352:2455–2458. [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Sarkar S, Studer A. Angew Chem. 2010;122:9452–9455. [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:9266–9269. doi: 10.1002/anie.201004593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The discussion regarding NHC-catalyzed reaction without added base has been reported in Ref. [18]. Our current understanding is that the counter anion serves the role of base in generating a trace amount of the active NHC species, which initiates the catalytic cycle.

- 25.For various discussions regarding the interaction of NHCs and protic nucleophiles, see: Kamber NE, Jeong W, Waymouth RM, Pratt RC, Lohmeijer BGG, Hedrick JL. Chem Rev. 2007;107:5813–5840. doi: 10.1021/cr068415b.Schmidt MA, Müller P, Movassaghi M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;49:4316–4318.Kuhn N, Mallah E, Maichle-Möβmer C, Steimann M. Z Naturforsch B. 2009;64:835–839.Myles L, Gore R, Spulak M, Gathergood N, Connon SJ. Green Chem. 2010;12:1157–1162.

- 26.The observed non-integral rate orders may be attributed to an inhibition event. The rationalization of the observed rate law is discussed in the rate law derivation (see the Supporting Information). From the derivation, the rate law may be reformulated as: rate = kobs[ynal]1[precatalyst 3]1[MeOH]0. This reformulation changes the activation entropy for the redox esterification reaction to + 3.95 calK−1 mol−1 while the activation enthalpy remains unchanged. In any case, the change in ΔS⧧ does not affect the interpretation of the proposed mechanism.

- 27.Coates RM, Rogers BD, Hobbs SJ, Curran DP, Peck DR. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:1160–1170. [Google Scholar]

- 28.For a similar approach to the measurements of the difference in the activation parameters between two competing pathways, see: Nigam M, Platz MS, Showalter BM, Toscano JP, Johnson R, Abbot SC, Kirchhoff MM. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:8055–8059.

- 29.Hansch C, Leo A, Taft RW. Chem Rev. 1991;91:165–195. [Google Scholar]

- 30.The redox reaction–protonation step is excluded from being rate limiting based on isotopic labeling experiments, which show no kinetic isotope effect for protonation (see the Supporting Information).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.