Abstract

Background

Allergy, the most common disease of immune dysregulation, has a substantial genetic component that is poorly understood. While complete disruption of TCR signaling causes profound immunodeficiency, little is known about the consequences of inherited genetic variants that cause partial, quantitative decreases in particular TCR signaling pathways, despite their potential to dysregulate immune responses and cause immunopathology.

Objective

To elucidate how an inherited decrease in TCR signaling through CARD11, a critical scaffold protein that signals to NFκB transcription factors, results in spontaneous, selective accumulation of large numbers of Th2 cells.

Methods

‘Unmodulated’ mice carry a Card11 single nucleotide variant (SNV) that decreases but does not abolish TCR/CD28 signaling to induce targets of NFκB. The consequences of this mutation on T cell subset formation in vivo were examined, and its effects within effector versus regulatory subsets were dissected by the adoptive transfer of wild-type cells, and by the examination of Foxp3-deficient unmodulated mice.

Results

Unlike the pathology-free boundary points of complete Card11 sufficiency or deficiency, unmodulated mice develop a specific allergic condition characterized by elevated IgE and dermatitis. The SNV partially decreases both the frequency of Foxp3+ T regulatory (Treg) cells and the efficiency of effector T cell formation in vivo. These intermediate effects combine to cause a gradual, selective expansion of Th2 cells.

Conclusions

Inherited reduction in the efficiency of TCR-NFκB signaling has graded effects on T cell activation and Foxp3+ Treg suppression that result in selective Th2 dysregulation and allergic disease.

Keywords: Card11, genetic variation, TCR signaling, NFκB, Th1/Th2, regulatory T cells, dermatitis, IgE

INTRODUCTION

Atopic dermatitis, rhinitis, asthma, food allergy and anaphylaxis are allergic diseases thought to share immunopathogenic mechanisms. The production of IgE in response to ubiquitous environmental antigens is the best predictor for allergy, and since class switch recombination to IgE depends on production of IL-4 and IL-13 by Th2 cells1, disordered Th2 differentiation is thought to be central to its pathogenesis2. Compared to other isotypes, serum IgE concentrations are normally very low, and IL-4-producing Th2 effector/memory cells are likewise normally infrequent in vivo3. These observations imply that Th2 differentiation is normally kept under tight and specific regulatory control, however the nature of this control and the ways in which it becomes selectively subverted in atopic individuals remain poorly understood4.

The Foxp3+ CD25+ T regulatory (Treg) subset has emerged as an essential mediator of immune regulation and homeostasis5–8 and, upon dysregulation, as a candidate to explain allergy9, 4. Null mutations in FOXP3 block the formation of this subset and result in a rare Mendelian disease known as IPEX syndrome (Immunodysregulation, Polyendocrinopathy, and Enteropathy, X-linked; OMIM #304790)10–12, which includes the clinical and histological hallmarks of severe eczema, food allergy and high levels of plasma IgE13. However, these allergic manifestations arise as part of a distinct genetic syndrome that also comprises severe intestinal inflammation, autoimmune type 1 diabetes, thyroid disease, lymphoproliferation and autoimmune cytopenias, occurring early in life with grave prognosis. Whether impaired regulatory T cell function can also explain the selective Th2 dysregulation and more limited spectrum of pathology that characterises common allergic disease remains unclear.

Single nucleotide variants (SNVs) represent the major form of human genetic variation and typically act singly or in combination to cause partial, quantitative changes in gene product activity (“hypomorphic alleles”), rather than null alleles or “knockouts”14. A great number of genes are required for the events following T cell antigen receptor engagement, and these events govern many critical T cell processes including T cell differentiation, selection, regulatory T cell formation, and peripheral activation and effector formation. It follows that SNVs affecting signaling components downstream of TCR/CD28 represent a likely set of candidates for the genetic predisposition to immunopathology. However, while the consequences of gene knockouts in many TCR signaling components are known, almost nothing is known about the consequences of SNVs causing partial, hypomorphic alleles. A straightforward extrapolation from knockout mutations would predict that partial defects might diminish both T cell activation and Treg function and cancel one another out in a “one step forwards, one step backwards” manner. Nevertheless, the possibility that quantitative variation will have paradoxical outcomes is illustrated by the central TCR signaling component, ZAP-70 tyrosine kinase, where null alleles result in severe immunodeficiency but SNVs that diminish but do not abolish the enzyme’s activity partially decrease thymic Treg formation and negative selection while preserving sufficient T cell activation to cause autoimmunity15–17. If we are to interpret patterns of human genetic variation revealed by genome-wide resequencing and association studies, it will be essential to test experimentally the consequences of graded decreases in different TCR signaling pathways.

Downstream of ZAP-70, TCR signaling events that activate the transcription factor NFκB are essential for T cell activation and Treg formation, and involve numerous genes and proteins. TCR and CD28 signaling activates Protein Kinase C theta to phosphorylate the signaling scaffold protein Card11 (also known as Carma1), which recruits Bcl10 and other proteins to activate the IκB kinase and trigger nuclear translocation of NFκB. Null mutations in Card11 or Bcl10 completely disrupt TCRCD28 signaling to NFκB and abolish T cell activation to cause profound immunodeficiency in the absence of any allergic or autoimmune pathology, despite simultaneously causing a complete absence of Foxp3+ Treg cells18–21. While the effects of complete disruption of TCR-NFκB signaling upon T cell activation cancel out the effects on Foxp3+ Tregs, it is not known how these opposing functions of TCR-NFκB signaling will behave in response to partial defects in the pathway, that are likely to be more common.

Here, we examine the cellular basis of spontaneous skin disease resembling atopic dermatitis and elevated IgE production in mice carrying an SNV in Card11 that decreases TCR-NFκB signaling22. We show that the SNV partially decreases both the frequency of Foxp3+ Tregs and the efficiency of T cell activation and effector cell formation, but that these opposing effects do not cancel one another out. Instead they combine to produce a gradual and selective expansion of Th2 cells and allergic pathology without autoimmunity or generalised inflammation. Our results establish that the TCR-NFκB signaling pathway is sensitive to inherited variation that lowers its activity, manifesting as selective Th2 dysregulation corresponding to the spectrum of common allergic disease.

METHODS

Mice

Foxp3null males on the C57BL/6 background25 were analyzed at 15–25 days of age, while Foxp3+/null carrier females were used for breeding. Unmodulated mice were generated by ENU mutagenesis on the C57BL/6 background and have been described22. Apart from Foxp3null pups, all mice were at least 6 weeks of age at the time of analysis and, as far as possible, mice of different genotypes were age- and sex-matched within experiments, often littermates. Mice were monitored daily for dermatitis, which typically presented as reddening and thickening of the skin on the ear, neck and face, accompanied by scratching of affected areas. All animal procedures were approved by the Australian National University Animal Ethics and Experimentation Committee.

Ex Vivo Stimulation and Intracellular Staining

Lymphocytes from pooled lymph nodes (cervical, inguinal, axillary, brachial), or peripheral blood (briefly pre-treated with tris ammonium chloride buffer to lyse erythrocytes) were suspended in RPMI media containing 10% fetal calf serum (Gibco). Cells were plated at 5 × 105 per well in 96-well tissue culture plates in 200µL of media containing phorbol myristate acetate (50ng/mL, Sigma), ionomycin (500ng/mL, Sigma) and GolgiStop (1/1000, BD) and left to accumulate cytokines for 4 hr at 37°C. Following stimulation, cells were harvested, washed and surface stained for 20 minutes at 4°C with Alexa Fluor 700-conjugated anti-mouse CD4 (clone RM4-5, Biolegend) and Pacific Blue-conjugated anti-mouse CD44 (clone IM7, Biolegend). Cells were fixed and permeablized using the eBioscience intracellular staining kit, and then stained for 20 minutes at 4°C with APC-conjugated anti-mouse IFNγ (clone XMG1.2, eBioscience), PECy7-conjugated anti-mouse IL-4 (clone BVD6-24G2, eBioscience), FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IL-17A (clone TC11-18H10.1, Biolegend), FITC-conjugated anti-mouse Foxp3 (clone FJK-16a, eBioscience), Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated antimouse IRF4 (clone IRF4.3E4, Biolegend) and/or Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated antimouse GATA3 (clone L50-823, BD). After staining, cells were washed and then read on an LSR II flow cytometer (BD). Flowjo software (Treestar) was used for analysis.

IgE ELISA

Plates were coated overnight with 1µg/mL anti-IgE capture Ab (clone R35-72, BD). The capture Ab was removed, plates were blocked with 1% BSA, washed, and then plasma samples (diluted 1:20) and standards were added, followed by a 1hr incubation at 37°C. Plates were then washed and 2µg/mL biotinylated anti-IgE detection Ab (clone R35-118, BD) was added. Binding was detected by subsequent incubation with streptavidin-conjugated alkaline phosphatase (Vector Laboratories), followed by the addition of phosphatase substrate tablets (Sigma) in phosphatase / glycine buffer. Plates were developed for 1hr at 37°C and optical densities at 405 nm were measured using a plate reader (Molecular Devices). IgE quantification was calculated according to calibration curves based on the optical densities for a series of dilutions of a control IgE isotype antibody of known concentration (clone C38-2, BD).

Overnight Stimulation

Splenocytes from Card11unm or wild-type mice were plated at 1 × 106 per well in 96-well tissue culture plates precoated with 1µg/mL anti-mouse CD3 (clone 145-2C11, BD) in 200µL of media containing 10µg/mL soluble antimouse CD28 (clone 37.51, BD). Following stimulation overnight, cells were harvested, washed, surface stained for 20 minutes at 4°C with Alexa Fluor 700-conjugated anti-mouse CD4 (clone RM4-5, Biolegend) and PE-conjugated anti-mouse CD25 (clone PC61, Caltag), and then read on the flow cytometer.

T cell adoptive transfer

Total CD4+ T cells (CD4+), Tregs (CD4+CD25+) or Teffs (CD4+CD25−CD62L+CD44+) were sorted from the spleens of CD45.1 donor mice using a FACS Aria cell sorter (BD). 106 total CD4+ T cells or 105 Tregs or Teffs were suspended in 200µL of PBS and injected intraveneously into the tail veins of recipient mice. Recipient were then monitored for dermatitis, and bled retro-orbitally to monitor the T cell phenotype. CD4+ T cell differentiation was assessed by ex vivo stimulation and intracellular staining (as described), and donor cells were identified by positive staining with PE-conjugated anti-mouse CD45.1 (clone A20, BD).

Statistical analysis

Unpaired t tests were used to compare two groups of data. Where there were more than two groups, one-way ANOVA analysis followed by the Bonferroni selected pairs post-test was applied. The alpha value for significance was set at 0.05. GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software) was used for statistical analysis.

RESULTS

Selective Th2 cell expansion and partial Treg deficiency caused by an inherited reduction in TCR/CD28-NFκB signaling

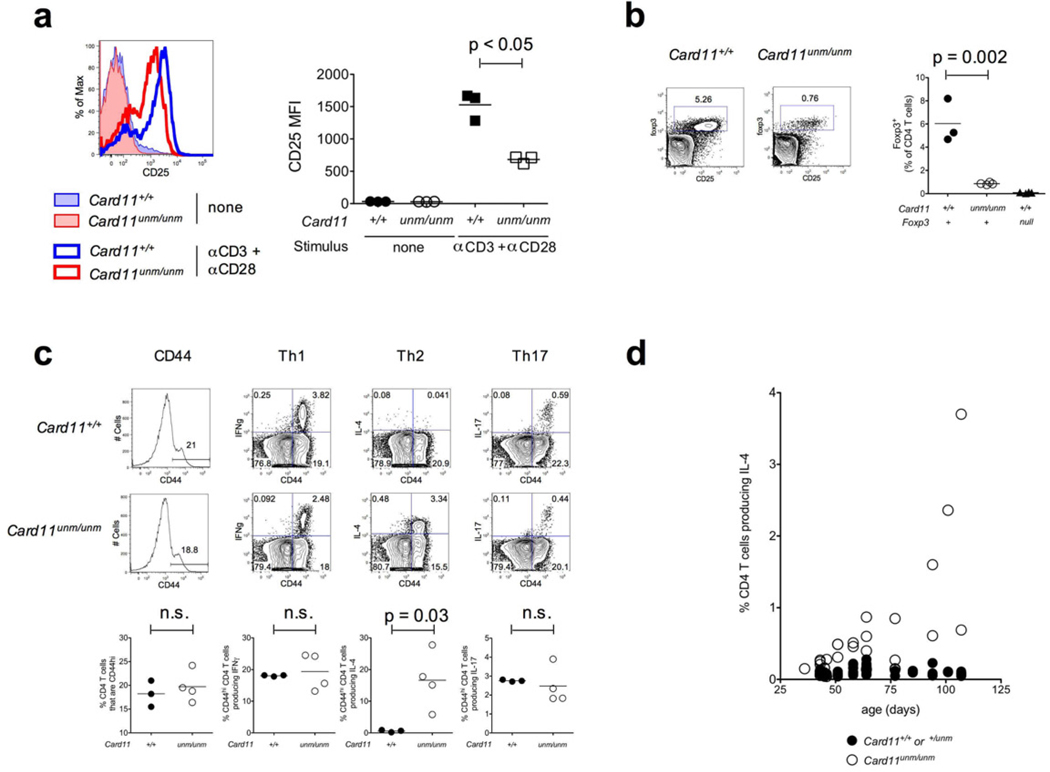

‘Unmodulated’ mice are homozygous for a single nucleotide variant (Card11unm) that causes an amino acid substitution in the coiled-coil domain of Card1122, a critical intracellular scaffolding protein for signaling by TCR and CD28 to activate canonical NFκB transcription factors19, 23, 24. Whereas the Card11-knockout abolishes TCR/CD28 induced expression of NFκB target genes such as Il2ra (encoding CD25)19, 23, 24, the Card11unm mutation is hypomorphic22 and decreases, but does not abolish, signaling through this pathway (Fig. 1a).

Figure 1.

(a) Histograms and plotted median fluorescence intensities (MFIs) of CD25 expression on CD4+ T cells from Card11unm or wild-type mice following overnight CD3+CD28 stimulation. Replicates are from three separate stimulated wells. (b) Treg abundance in lymph nodes from wild-type or Card11unm mice, determined by intracellular staining for Foxp3, gated on CD4+ T cells. (c) Expression of CD44, IFNγ, IL-4 and IL-17 by lymph node CD4+ T cells from Card11unm and wild-type mice after 4 hour ex vivo PMA+ionomycin stimulation and intracellular staining. (d) IL-4-producing CD4+ T cell frequency in blood from Card11unm mice of a range of ages and their wild-type or heterozygous littermates, detected by intracellular staining as above.

Development and thymic selection of conventional CD4+ and CD8+ T cells proceeds normally in unmodulated mice22, 25, whereas the formation of Foxp3+ Tregs is compromised, and these cells occur in the periphery at about one-seventh the frequency found in wild-type controls (Fig. 1b). A decrease in the Foxp3+ Treg frequency is also observed in the thymii of Card11unm mice (Supplementary Fig. 1). The reduction in Treg frequency in Card11unm mice contrasts with the complete absence of this subset in Card11-knockout animals21, consistent with the hypomorphic nature of Card11unm. Foxp3+ Tregs in Card11unm mice express reduced levels of CD25 and CTLA-4 but normal or slightly increased levels of Foxp3, IRF4 and GITR (Supplementary Fig. 1).

In contrast to the massive expansion of activated T cells seen in mice lacking Foxp3+ Treg cells25, Card11unm mice do not develop generalized T cell activation and have no significant elevation in the percentages of CD44hi CD4+ T cells and of CD44hi CD4+ T cells producing IFNγ or IL-17. However, Card11unm mice developed a dramatically increased frequency of IL-4-producing CD4+ T cells (Fig. 1c). The IL-4+ T cell population gradually increases with age, accounting for between 0.5 and 4% of CD4+ T cells in 100 day old mutant animals, but less than 0.1% in control mice (Fig. 1d). These IL-4+ CD4+ T cells express high levels of GATA3, the master transcriptional regulator of Th2 cells (Supplementary Fig. 2). In Card11unm mice carrying an OT-II TCR transgene, an expanded IL-4+ population likewise develops, but this expanded population derives exclusively from CD4+ T cells bearing endogenously-rearranged (Vβ5−) TCRs (Supplementary Fig. 3), suggesting the need for specific antigenic stimulation rather than a generalized T cell activation into Th2 cells.

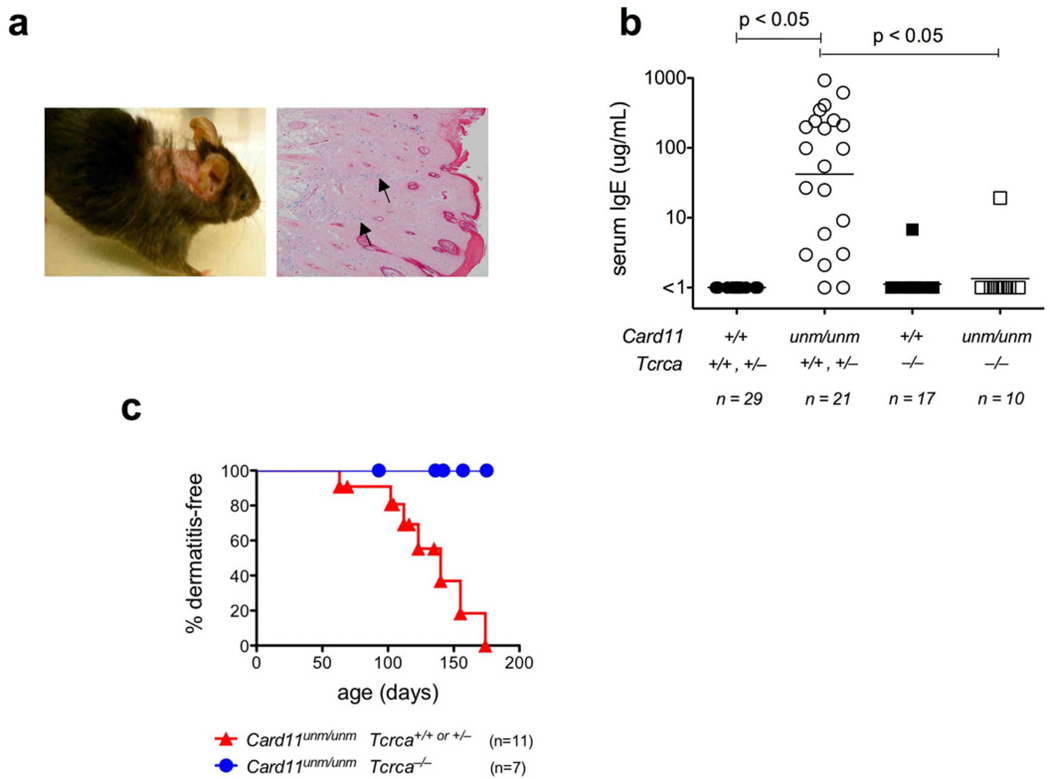

Th2 cell expansion leads to selective allergic disease

The gradual, selective expansion of Th2 cells in Card11unm mice precedes development of allergic disease. This is characterized by a substantial elevation of plasma IgE and erosive dermatitis of the neck and ear with prominent acanthosis, parakeratosis and hyperkeratotic scale, and heavy infiltration by mast cells (Fig. 2a, b). The dermatitis is highly penetrant but of relatively late onset, with median incidence at ~130 days of age (Fig. 2c). However, we could not find evidence of colitis, diabetes or other inflammatory lesions typical of complete Treg cell deficiency. Moreover, in contrast to mice harboring a partial defect in TCR signaling at the more proximal point, ZAP-7017, tests for antinuclear autoantibodies were uniformly negative (data not shown). When crossed to a Tcra null-allele, αβT cell deficiency abolished both excessive IgE production and dermatitis in Card11unm mice (Fig. 2b, c). By contrast, B cell deficiency introduced by crossing to a Cd79a null allele eliminated IgE production but did not prevent dermatitis (data not shown). Hence αβT cells are required to drive elevated IgE production and dermatitis as two independent downstream events.

Figure 2.

(a) Macroscopic appearance and histology of an affected Card11unm mouse, showing pruritic skin lesion and mast cell infiltrates (arrows) revealed by alcian blue staining. (b) Plasma IgE concentrations in αβT cell-sufficient or deficient mice carrying either wild-type or mutant alleles of Card11, quantified by ELISA. (c) Incidence of dermatitis in αβT cell-sufficient or deficient Card11unm mice.

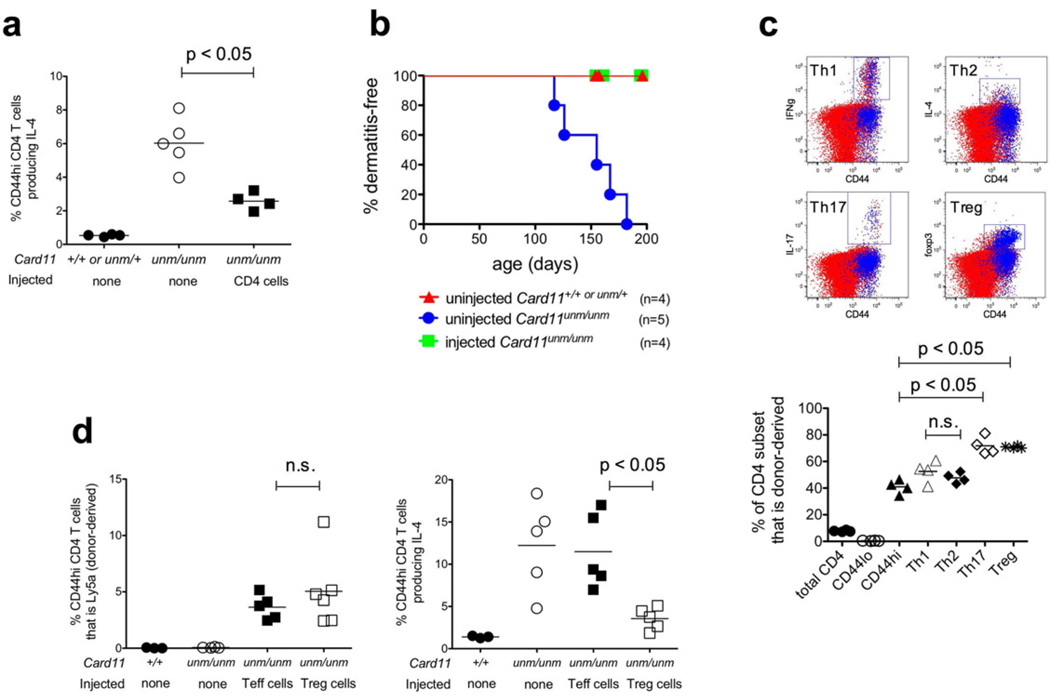

Transfer of wild-type Tregs prevents Th2 expansion

We next investigated whether reduced Treg function is responsible for the Th2 cell expansion in Card11unm mice by reconstituting this subset. First, we adoptively transferred CD4+ T cells that were FACS-sorted from congenically-marked wild-type donors into young Card11unm recipients and monitored them for Th2 cell accumulation and dermatitis. Transfer of 106 unfractionated wild-type CD4+ T cells was sufficient to significantly reduce Th2 cell expansion assessed 10 weeks post-transfer (Fig. 3a). Moreover, whereas all untreated controls succumbed to dermatitis by 150–200 days of age, recipients of wild type CD4+ T cells showed no signs of disease (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

(a) Percentage of IL-4-producing cells among lymph node CD44hi CD4+ T cells, or (b) incidence of dermatitis, in Card11unm mice that were either untreated or injected i.v. with 106 sorted CD4+ T cells from a wild-type Ly5a donor 10 weeks prior, measured as previously. (c) Representative plots (upper) and quantitation (lower) showing the representation of donor- (Ly5a+, shown in blue) and recipient-derived (Ly5b+, shown in red) cells among lymph node CD44lo, CD44hi, Th1, Th2, Th17 or Treg subsets in the recipient mice described in (a). (d) Representation of donor-derived (Ly5a+) cells (left) or total IL-4-producing cells (right) among the CD44hi CD4+ T cell compartment in the peripheral blood of Card11unm mice that were either untreated or injected i.v. with 105 sorted Treg (CD4+CD25+) or Teff (CD4+CD25−CD44hiCD62Llo) cells 10 weeks prior. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

Donor-derived wild-type cells (blue dots in Fig. 3c plots) formed a very low proportion of CD44lo CD4+ T cells in the Card11unm recipients, as expected given that a relatively small number of donor T cells were being diluted into a large recipient population. In contrast, donor-derived cells accounted for ~40% of the CD44hi CD4+ T cell subset (Fig. 3c), representing considerable expansion beyond the 106 input cells and indicating that they had undergone extensive proliferation into effector/memory cells. While normal frequencies of CD44hi T cells are present in unmanipulated Card11unm mice, the repopulation of this subset by wild-type cells could be explained by a relative defect in Card11unm T cell activation or effector/memory cell persistence that becomes apparent under competitive repopulation conditions. Repopulation by wild-type T cells occurred comparably in the Th1 and Th2 subsets of CD44hi CD4+ cells (Fig. 3c). In contrast, repopulation by wild-type cells was more extreme in the Th17 and Treg subsets where donor cells comprised ~70%. Repopulation of the Foxp3+ Treg population by donor cells increased the frequency of Tregs relative to uninjected Card11unm mice, although not to the frequency in wild-type controls (Supplementary Fig. 4).

To test whether the transferred T-effector (‘Teff’) or Treg populations were responsible for the ameliorated Th2 phenotype in the recipient mice, we repeated the transfer experiment using fractionated wild-type Treg (CD4+CD25+) or Teff (CD4+CD25−CD44hiCD62Llo) donor T cells. Following transfer, both populations retained their respective Foxp3+ and Foxp3− phenotypes (not shown), and became similarly engrafted into the recipients’ CD44hi CD4+ T cell compartments (Fig. 3d). Th2 cell accumulation in Card11unm recipients was unaffected by transfer of wild-type Teffs, but it was suppressed by the transfer of wildtype Tregs. Thus, Th2 cells accumulate due to the partial Treg deficiency in Card11unm mice.

Differentiating the effect of decreased TCR-CD28-CARD11-NFκB signaling within Teffector cells from its effect on Tregs

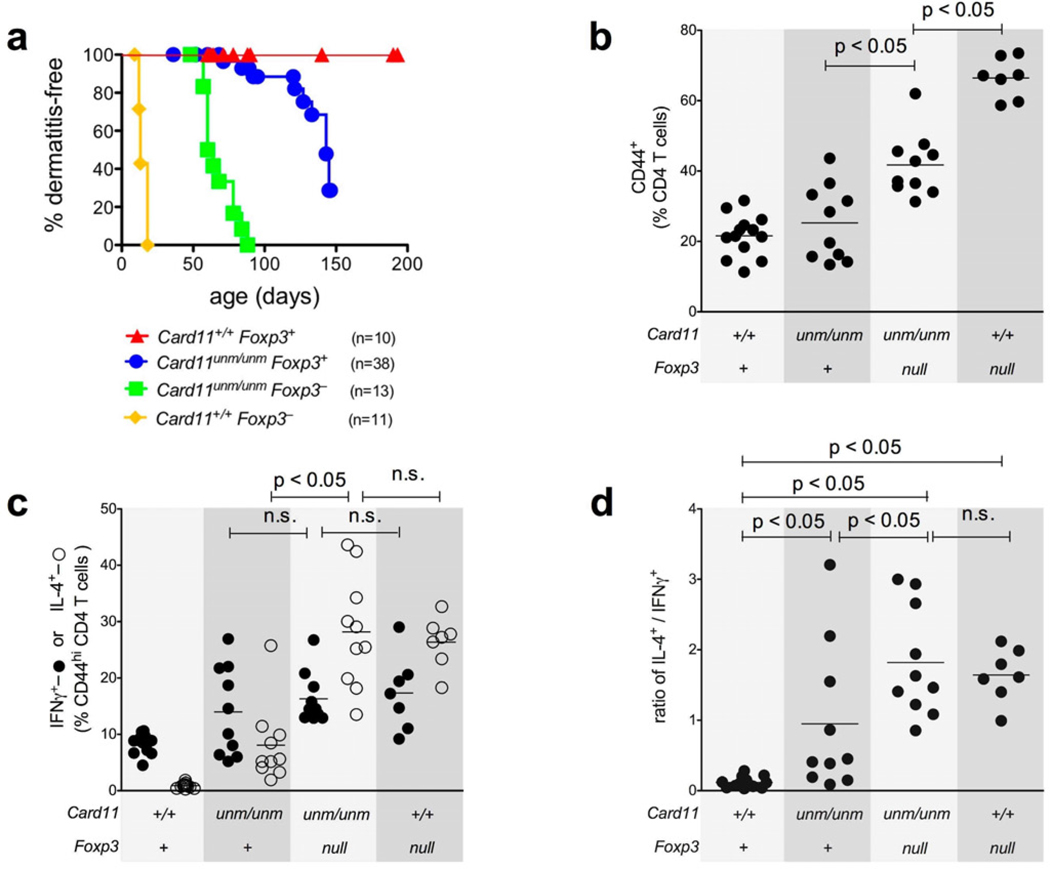

In Foxp3null mice there is massive T cell activation and differentiation into Th1 and Th2 cells, autoimmunity and early lethality, while Card11unm animals have normal proportions of activated T cells with a selectively expanded Th2 population and late-onset allergic disease without autoimmunity. These disparate phenotypes might be explained by the presence of some Treg cells in Card11unm mice, and/or by the decrease in TCR/CD28 signaling for T cell activation and Teff formation caused by Card11unm. To dissect the contributions of these effects, we bred Card11unmFoxp3null double mutants and compared them with single mutant controls in terms of disease severity (measured by dermatitis incidence) and CD4+ T cell activation/differentiation state (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 5).

Figure 4.

(a) Incidence of dermatitis in Card11unmFoxp3null mice compared to single mutant and wild-type controls. (b, c, d) Quantitation of CD4+ T cell expression of CD44, IFNγ, IL-4, or the ratio of IL-4+ cells / IFNγ+ cells from mice of the four genotypes, measured by ex vivo stimulation and intracellular cytokine staining as previously. Data are collated from 4 independent experiments.

The effect of the remaining Treg cells in Card11unm mice was illuminated by comparing the two groups of mice matched for the Card11 defect: Card11unmFoxp3+ mice with a reduced Treg frequency, versus Card11unmFoxp3null mice with complete Treg deficiency. Dermatitis occurred at a younger age in Card11unmFoxp3null double mutants (Fig. 4a, green curve) than in Card11unmFoxp3+ mice (blue curve). Card11unmFoxp3null animals with complete Treg deficiency had a significantly increased proportion of CD44hi T cells (Fig. 4b), and the proportion of CD44hi cells that produced IL-4, but not IFNγ, was also increased. Consequently, although there was some variation between mice, the absence of unmodulated Tregs led to a significant increase in the average ratio of IL-4 to IFNγ producers in Card11unmFoxp3null versus Card11unmFoxp3+ mice (Fig. 4d). These results indicate that the remaining Tregs in Card11unm animals play an active role in restraining T cell cytokine production and delaying disease, but do not account for the Th2 bias as their removal does not normalize this bias but may in fact exaggerate it.

The effect of the Card11unm mutation within Teff cells was illuminated by comparing the two groups of mice with no Treg cells: Card11+Foxp3null mice with normal TCR-NFκB signaling in Teffs, and Card11unmFoxp3null double mutants with lower TCR-NFκB signaling. Whereas Card11+Foxp3null mice developed dermatitis and typical scurfy phenotype by 15 days of age (yellow curve in Fig. 4a), the median onset of dermatitis was delayed to ~70 days of age in Card11unmFoxp3null mice (green curve). Moreover, whereas ~70% of CD4+ T cells were CD44hi in Card11+Foxp3null mice, this was decreased to ~40% in Card11unmFoxp3null mice (Fig. 4b). Despite this amelioration of the generalized T cell activation by Card11unm, the proportion and ratio of CD44hi CD4+ T cells that produced IFNγ or IL-4 did not change between Card11unmFoxp3null and Card11+Foxp3null mice (Fig. 4c). Thus, in the complete absence of Treg cells, Card11unm reduces the efficiency of Teff cell formation but does not change the Th2/Th1 bias of the effectors that form.

These results, together with the cell transfer experiments, indicate that reduced Treg function is sufficient to explain the preferential dysregulation of Th2 cells in Card11unm animals. This is supported by a consideration of Th2:Th1 ratios in mice of the different genotypes (Fig. 4d). Wild-type mice showed a Th1-dominated state with a 1:6 bias of IL-4-producers to IFNγ-producers. In contrast, the Th2:Th1 ratio was significantly shifted towards Th2 in each of the Card11unmFoxp3+, Card11unmFoxp3null and Card11+Foxp3null mice. In other words, a change towards Th2 bias was observed in mice of all three genotypes that have Treg deficits, including completely Treg-deficient mice with wild-type Card11.

DISCUSSION

How can quantitative genetic variation predispose to the selective Th2 dysregulation of allergy? Extrapolating from knockout mutations, partial defects in the complex signaling pathway between the TCR and NFκB might be predicted to diminish both T cell activation and Treg function and cancel one another out in a “one step forwards, one step backwards” manner. However, here we show that an intermediate reduction in TCR-NFκB signaling through Card11 confers partial and non-counterbalancing defects in effector and regulatory T cells, leading to selective Th2 cell expansion and allergic dermatitis. We demonstrate that the selective Th2 dysregulation can be explained as the product of two opposing effects of decreased TCR-NFκB signaling: (1) partial Teff deficiency that has an equal effect slowing the accumulation of Th1, Th2 and Th17 effectors, and (2) partial Treg deficiency, interfering with normal Treg function sufficiently to allow dramatically increased Th2 cell accumulation and dermatitis but preserving enough Treg function to prevent lymphoproliferation, colitis, and autoimmunity. Our results establish that the opposing functions of the TCR/CD28 signaling pathway are prone to imbalance resulting from genetic variation that lowers its activity, with the imbalance presenting as a selective Th2 cell accumulation disease corresponding to the spectrum of common allergy.

Card11unm mice have partial Treg deficiency, which leads to spontaneous Th2 cell expansion and a late-onset allergic disorder comprising selective IgE hyperproduction, mastocytosis and dermatitis (Figs. 1 and 2). Th2 cell formation in Card11unm mice appears to be antigen driven and not a general effect on all CD4+ T cells, since OVA-specific T cells did not adopt a Th2 phenotype (Supplementary Fig. 3). While it will be important to map the specificity of the emergent Th2 cells, this result, together with the size of the response in the absence of active immunization, suggests that Tregs normally actively restrain Th2 differentiation in response to either self-antigens or commensals in the steady state.

Despite their spontaneous disease phenotype, Card11unm mice are protected from the extreme lymphoproliferation, T cell hyperactivation, autoimmunity and early death of Foxp3null mice, because Card11unm reduces the efficiency of effector T cell accumulation and retains some Treg activity (Figs. 3 & 4). This contrasts with the Card11 null-allele which completely abolishes both T cell activation and Treg formation, and has no spontaneous immunopathological consequences19. Our results therefore demonstrate how a partial defect in a pathway with pleiotropic functions - TCR/CD28 signaling to NFκB - can produce an outcome that is shaped by unequal titration of opposing effects and that could not have been predicted from null alleles that completely disrupt the pathway.

Card11 is one of many proteins required for normal TCR-CD28 signaling to activate NFκB transcription factors and promote the activation and differentiation of Teffs and the development and maintenance of Tregs. TCR and CD28 signaling acts through a cascade of tyrosine kinases, adaptor molecules, G-proteins and Phospholipase C-γ 1. These activate Protein Kinase C (PKC)-θ, which then phosphorylates Card11 and triggers an allosteric change that brings together Bcl10, Malt1, TAK1, IKKγ, and other proteins that collectively activate the IκB kinase and trigger nuclear translocation of canonical NFκB transcription factors26. Among the direct target genes activated by NFκB in T cells are Il2, encoding the cytokine and T cell growth factor IL-2, and Il2ra, encoding the alpha chain of the IL-2 receptor. Null mutations in CD2827, 28, PKCθ29, 30 the c-Rel subunit of NFκB31, Il232, 33 and Il2ra33 decrease T cell activation and the frequency of Treg cells and, in the case of Il2 and Il2ra, cause an IPEX-like syndrome of T cell lymphoproliferation, multi-organ inflammation and autoimmunity34, 35. These proteins provide numerous points at which subtle genetic variation could disproportionately reduce Treg relative to Teff function to permit selective Th2 overaccumulation and allergy.

Tregs have been implicated in the regulation of Th2 deviation. Wan and Flavell reported that integration of a luciferase-containing construct into the Foxp3 gene attenuated Foxp3 expression 5–10-fold and led to a spontaneous outbreak of IL-4-producing CD4+ T cells (including the attenuated Foxp3+ cells themselves) and pathology36. In that instance, Th2 pathology was interpreted as being the consequence of conversion of Foxp3+ Tregs into Th2 effector cells that in turn polarized other T cells to Th2. Subsequently, Rudensky and colleagues found that selective inactivation of Irf4 within Foxp3+ cells resulted in spontaneous disease with plasma cell infiltration and selectively increased Th2 cell frequencies and IgE titres37.

Despite the observed Th2 bias, both of these studies describe more severe syndromes of generalized T cell activation and multi-organ inflammation than we observe in Card11unm mice. Moreover, the mechanisms they demonstrate do not appear to account for the Card11unm phenotype, as expression of neither Foxp3 nor Irf4 was decreased in Card11unm Tregs (Supplementary Fig. 1). In contrast, our observation of a Th2 bias in mice with wild-type Teffs but completely lacking Foxp3+ Tregs (Foxp3null mice in Fig. 4c, d) suggests that the Th2 bias in Card11unm mice can be explained by the Treg deficit alone, without the need to invoke particular qualitative defects in Card11unm Tregs or Teffs. This is supported by the observations in Fig. 4c, d that (i) the proportion of activated cells that were of Th2 or Th1 phenotype was similar between Card11+/+Foxp3null and Card11unmFoxp3null mice (arguing against a Teff-intrinsic bias caused by Card11unm), and (ii) the level of Th2 bias was no greater in Card11unmFoxp3+ than Card11unmFoxp3null mice (arguing against a Treg phenotype in Card11unm that is preferentially suppressive of Th1 responses).

The relationship established here between decreased TCR-Card11-NFκB signaling, partial Treg deficiency and selectively dysregulated accumulation of Th2 cells in vivo provides a mechanistic basis to explain the growing number of inverse correlations between Treg numbers and allergy or atopy38–40. Relative deficiency of Tregs in cord blood predicts atopy later in childhood41. Effective therapeutic maneuvers in patients with severe allergy are reported to correlate with increased Treg frequencies42. Our findings invite future studies investigating associations between allergy, Treg frequency and common or family-specific variation in the many genes encoding components of the TCR-CD28-CARD11-NFκB pathway. As a corollary, interventions that enhance TCR-NFκB signaling efficiency may be beneficial in the treatment or prevention of allergy.

Key messages.

-

–

Graded decreases in particular TCR signaling pathways can have paradoxical consequences that need to be tested experimentally to help interpret patterns of human genetic variation revealed by genome-wide resequencing and association studies.

-

–

An inherited decrease in the efficiency of TCR-NFκB signaling causes graded decreases in T cell activation and suppression by Foxp3+ Tregs that do not cancel one another out, but instead result in selective Th2 dysregulation and allergic disease.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank and acknowledge Dr Stephen Daley and Prof Carola Vinuesa for their advice on the manuscript. The research was made possible by funding from the National Health & Medical Research Council and the Australian Research Council.

Funding

The research was funded by the ACT Health & Medical Research Council, the Australian National Health & Medical Research Council, and the Australian Research Council.

Abbreviations

- FACS

Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting

- IgE

Immunoglobulin E

- IPEX

Immunodysregulation, Polyendocrinopathy, and Enteropathy, X-linked

- PKC

Protein Kinase C

- SNV

Single Nucleotide Variant

- TCR

T Cell Receptor

- Th1

T Helper type 1

- Th2

T Helper type 2

- Th17

T Helper type 17

- Treg

T Regulatory

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Coffman RL, Ohara J, Bond MW, Carty J, Zlotnik A, Paul WE. B cell stimulatory factor-1 enhances the IgE response of lipopolysaccharide-activated B cells. J Immunol. 1986;136:4538–4541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu J, Paul WE. CD4 T cells: fates, functions, and faults. Blood. 2008;112:1557–1569. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-078154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geha RS, Jabara HH, Brodeur SR. The regulation of immunoglobulin E class-switch recombination. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:721–732. doi: 10.1038/nri1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Umetsu DT, DeKruyff RH. The regulation of allergy and asthma. Immunol Rev. 2006;212:238–255. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thornton AM, Shevach EM. CD4+CD25+ immunoregulatory T cells suppress polyclonal T cell activation in vitro by inhibiting interleukin 2 production. J Exp Med. 1998;188:287–296. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.2.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakaguchi S. Naturally arising CD4+ regulatory t cells for immunologic self-tolerance and negative control of immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:531–562. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belkaid Y, Piccirillo CA, Mendez S, Shevach EM, Sacks DL. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells control Leishmania major persistence and immunity. Nature. 2002;420:502–507. doi: 10.1038/nature01152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mottet C, Uhlig HH, Powrie F. Cutting edge: cure of colitis by CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2003;170:3939–3943. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.8.3939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin W, Truong N, Grossman WJ, Haribhai D, Williams CB, Wang J, et al. Allergic dysregulation and hyperimmunoglobulinemia E in Foxp3 mutant mice. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:1106–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bennett CL, Christie J, Ramsdell F, Brunkow ME, Ferguson PJ, Whitesell L, et al. The immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked syndrome (IPEX) is caused by mutations of FOXP3. Nat Genet. 2001;27:20–21. doi: 10.1038/83713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wildin RS, Ramsdell F, Peake J, Faravelli F, Casanova JL, Buist N, et al. X-linked neonatal diabetes mellitus, enteropathy and endocrinopathy syndrome is the human equivalent of mouse scurfy. Nat Genet. 2001;27:18–20. doi: 10.1038/83707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brunkow ME, Jeffery EW, Hjerrild KA, Paeper B, Clark LB, Yasayko SA, et al. Disruption of a new forkhead/winged-helix protein, scurfin, results in the fatal lymphoproliferative disorder of the scurfy mouse. Nat Genet. 2001;27:68–73. doi: 10.1038/83784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wildin RS, Smyk-Pearson S, Filipovich AH. Clinical and molecular features of the immunodysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X linked (IPEX) syndrome. J Med Genet. 2002;39:537–545. doi: 10.1136/jmg.39.8.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Birney E, Stamatoyannopoulos JA, Dutta A, Guigo R, Gingeras TR, Margulies EH, et al. Identification and analysis of functional elements in 1% of the human genome by the ENCODE pilot project. Nature. 2007;447:799–816. doi: 10.1038/nature05874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arpaia E, Shahar M, Dadi H, Cohen A, Roifman CM. Defective T cell receptor signaling and CD8+ thymic selection in humans lacking zap-70 kinase. Cell. 1994;76:947–958. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90368-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sakaguchi N, Takahashi T, Hata H, Nomura T, Tagami T, Yamazaki S, et al. Altered thymic T-cell selection due to a mutation of the ZAP-70 gene causes autoimmune arthritis in mice. Nature. 2003;426:454–460. doi: 10.1038/nature02119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siggs OM, Miosge LA, Yates AL, Kucharska EM, Sheahan D, Brdicka T, et al. Opposing functions of the T cell receptor kinase ZAP-70 in immunity and tolerance differentially titrate in response to nucleotide substitutions. Immunity. 2007;27:912–926. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruland J, Duncan GS, Elia A, del Barco Barrantes I, Nguyen L, Plyte S, et al. Bcl10 is a positive regulator of antigen receptor-induced activation of NF-kappaB and neural tube closure. Cell. 2001;104:33–42. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00189-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hara H, Wada T, Bakal C, Kozieradzki I, Suzuki S, Suzuki N, et al. The MAGUK family protein CARD11 is essential for lymphocyte activation. Immunity. 2003;18:763–775. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00148-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Medoff BD, Seed B, Jackobek R, Zora J, Yang Y, Luster AD, et al. CARMA1 is critical for the development of allergic airway inflammation in a murine model of asthma. J Immunol. 2006;176:7272–7277. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.12.7272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Molinero LL, Yang J, Gajewski T, Abraham C, Farrar MA, Alegre ML. CARMA1 controls an early checkpoint in the thymic development of FoxP3+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2009;182:6736–6743. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jun JE, Wilson LE, Vinuesa CG, Lesage S, Blery M, Miosge LA, et al. Identifying the MAGUK protein Carma-1 as a central regulator of humoral immune responses and atopy by genome-wide mouse mutagenesis. Immunity. 2003;18:751–762. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00141-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang D, You Y, Case SM, McAllister-Lucas LM, Wang L, DiStefano PS, et al. A requirement for CARMA1 in TCR-induced NF-kappa B activation. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:830–835. doi: 10.1038/ni824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gaide O, Favier B, Legler DF, Bonnet D, Brissoni B, Valitutti S, et al. CARMA1 is a critical lipid raft-associated regulator of TCR-induced NF-kappa B activation. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:836–843. doi: 10.1038/ni830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fontenot JD, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:330–336. doi: 10.1038/ni904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thome M. CARMA1, BCL-10 and MALT1 in lymphocyte development and activation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:348–359. doi: 10.1038/nri1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Green JM, Noel PJ, Sperling AI, Walunas TL, Gray GS, Bluestone JA, et al. Absence of B7-dependent responses in CD28-deficient mice. Immunity. 1994;1:501–508. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tang Q, Henriksen KJ, Boden EK, Tooley AJ, Ye J, Subudhi SK, et al. Cutting edge: CD28 controls peripheral homeostasis of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2003;171:3348–3352. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.7.3348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pfeifhofer C, Kofler K, Gruber T, Tabrizi NG, Lutz C, Maly K, et al. Protein kinase C theta affects Ca2+ mobilization and NFAT cell activation in primary mouse T cells. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1525–1535. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gupta S, Manicassamy S, Vasu C, Kumar A, Shang W, Sun Z. Differential requirement of PKC-theta in the development and function of natural regulatory T cells. Mol Immunol. 2008;46:213–224. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.08.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Isomura I, Palmer S, Grumont RJ, Bunting K, Hoyne G, Wilkinson N, et al. c-Rel is required for the development of thymic Foxp3+ CD4 regulatory T cells. J Exp Med. 2009;206:3001–3014. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith KA. Interleukin-2: inception, impact, and implications. Science. 1988;240:1169–1176. doi: 10.1126/science.3131876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fontenot JD, Rasmussen JP, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. A function for interleukin 2 in Foxp3-expressing regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1142–1151. doi: 10.1038/ni1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sadlack B, Merz H, Schorle H, Schimpl A, Feller AC, Horak I. Ulcerative colitis-like disease in mice with a disrupted interleukin-2 gene. Cell. 1993;75:253–261. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80067-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caudy AA, Reddy ST, Chatila T, Atkinson JP, Verbsky JW. CD25 deficiency causes an immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linkedlike syndrome, and defective IL-10 expression from CD4 lymphocytes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:482–487. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wan YY, Flavell RA. Regulatory T-cell functions are subverted and converted owing to attenuated Foxp3 expression. Nature. 2007;445:766–770. doi: 10.1038/nature05479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zheng Y, Chaudhry A, Kas A, deRoos P, Kim JM, Chu TT, et al. Regulatory T-cell suppressor program co-opts transcription factor IRF4 to control T(H)2 responses. Nature. 2009;458:351–356. doi: 10.1038/nature07674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Akdis M, Verhagen J, Taylor A, Karamloo F, Karagiannidis C, Crameri R, et al. Immune responses in healthy and allergic individuals are characterized by a fine balance between allergen-specific T regulatory 1 and T helper 2 cells. J Exp Med. 2004;199:1567–1575. doi: 10.1084/jem.20032058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee JH, Yu HH, Wang LC, Yang YH, Lin YT, Chiang BL. The levels of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in paediatric patients with allergic rhinitis and bronchial asthma. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;148:53–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03329.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schaub B, Liu J, Hoppler S, Schleich I, Huehn J, Olek S, et al. Maternal farm exposure modulates neonatal immune mechanisms through regulatory T cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:774–782. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.01.056. e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schaub B, Liu J, Hoppler S, Haug S, Sattler C, Lluis A, et al. Impairment of T-regulatory cells in cord blood of atopic mothers. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:1491–1499. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.04.010. e1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miyara M, Wing K, Sakaguchi S. Therapeutic approaches to allergy and autoimmunity based on FoxP3+ regulatory T-cell activation and expansion. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:749–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.03.001. quiz 56–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.