Abstract

The complete mechanism of labor induction in eutherian mammals remains unclear. Although important roles for the fetus and placenta in triggering labor have been proposed, no gene has been shown to be required in the fetus/placenta for labor induction. Here we show that Nrk, an X-linked gene encoding a Ser/Thr kinase of the germinal center kinase family, is essential in the fetus/placenta for labor in mice. Nrk was specifically expressed in the spongiotrophoblast layer, a fetus-derived region of the placenta, and Nrk disruption caused dysregulated overgrowth of the layer. Due to preferential inactivation of the paternally derived X chromosome in placenta, Nrk heterozygous mutant placentas exhibited a similar defect to that in Nrk-null tissues when the wild-type allele was paternally derived. However, the phenotype was weaker than in Nrk-null placentas due to leaky Nrk expression from the inactivated X chromosome. Crossing of Nrk-null females to wild-type and Nrk-null males, as well as uterine transfer of Nrk-null fetuses to wild-type females, revealed that pregnant mice exhibit a severe defect in delivery when all fetuses/placentas are Nrk-null. In addition, Nrk was not expressed in female reproductive tissues such as the uterus and ovary, as well as the fetal amnion and yolk sac, in pregnant mice. Progesterone and estrogen levels in the maternal circulation and placenta, which control the timing of labor, were unaffected upon Nrk disruption. We thus provide evidence for a novel labor-inducing fetoplacental signal that depends on the X chromosome and possibly arises from the placenta.

Keywords: Development, Gene Knockout, Mouse Genetics, Reproduction, Serine Threonine Protein Kinase, X Inactivation, Labor, Obstetrics, Parturition, Placenta

Introduction

In the gestation of eutherian mammals, the onset of labor is strictly controlled so that offspring are safely delivered at an appropriate stage of development. In humans, preterm labor, defined as labor at <37 weeks of gestation, accounts for a large proportion of the deaths and permanent disabilities among newborns (1), underscoring the physiological and medical importance of regulating the timing of labor. In many mammalian species, a decline in the maternal level of circulating progesterone, referred to as progesterone withdrawal, is a prerequisite for labor initiation (2, 3). Conversely, the maternal blood level of estrogen, which induces uterine contraction, is shown to increase in late gestation in several species (2, 4). However, the complete mechanism of labor induction remains unclear.

The fetus and placenta are believed to play critical roles in labor induction. Before the Common Era, the Greek scientist Hippocrates described that a baby may decide the timing of its own birth (4). It is now suggested in several species that labor-inducing signals originate from the fetus or placenta and are transmitted to the mother (4, 5). In sheep, there is evidence that the fetal hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis involving corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH),3 adrenocorticotropin, and cortisol induces the conversion of progesterone to estrogen in the placenta near term. In primates, CRH is secreted from the placenta and eventually induces the secretion from the fetal adrenal gland of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, a steroid that is converted to estrogen in the placenta. In either case, placenta-derived estrogen is transported to and acts on the maternal uterus. In mice, however, CRH knock-out dams carrying CRH knock-out fetuses exhibit normal delivery (6). The lung surfactant protein-A (SP-A), which is secreted from fetal lung and activates amniotic fluid macrophages to induce an inflammatory response in utero, has also been proposed as a fetal hormone inducing labor in mice (7). Again, however, SP-A knock-out dams carrying SP-A knock-out fetuses deliver normally (8). These observations argue against indispensable roles for fetal CRH and SP-A in labor induction at least in mice. Although knock-out mouse studies have identified ∼10 genes that are essential for labor, all of them are required in the dam and not in the fetus or placenta (9, 10). Therefore, genetic evidence for the requirement of a fetoplacental factor in labor induction is lacking.

Nrk (Nik-related kinase), also named NESK (Nik-like embryo-specific kinase), is a Ser/Thr kinase encoded in the X chromosome (Xq22.3 in humans and X 53.0 cM in mice) (11, 12). It belongs to the germinal center kinase family, which is conserved among eukaryotes and plays essential roles in various aspects of development (13, 14). In mice, Nrk mRNA is detected in the fetus (predominantly in skeletal muscle) but not in any adult tissues examined (11, 12). Although overexpression studies in cultured mammalian cells suggest that Nrk possibly participates in JNK signaling (12), apoptosis (15), and F-actin organization (16), its physiological role has been totally unknown. To elucidate it, we here generated and studied Nrk knock-out mice.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animal Experiments

All animal experiments were approved by and performed under the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Research Advisory Committee of Tokyo Institute of Technology. Female mice found to have copulation plugs at 9–11 a.m. were considered to be at 0.5 days postcoitum (dpc) at noon of that day.

Derivation and Genotyping of Mutant Mice

The Nrk genomic locus was cloned from a 129/Sv mouse genomic library (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) using a 5′ region of Nrk cDNA as a probe. The gene targeting vector was constructed using the plasmid pPGKneolox2DTA (17) and contains a neo expression cassette flanked by 1.1-kb SpeI-BamHI and 4.0-kb XhoI-XbaI genomic sequences derived from the cloned Nrk locus. This vector replaces a 1.1-kb genomic fragment containing Nrk exon 1 with a neo cassette upon homologous recombination. The construct was electroporated into 129/S4-derived ES cells (17), and colonies were selected with G418. Homologous recombination events were screened by PCR using primers corresponding to the neo gene and a genomic sequence outside the targeting construct. Southern blotting, ES cell culture, and blastocyst injection were performed according to standard procedures. PCR genotyping of mice was performed on yolk sac and tail biopsy samples as described (17), using the following combination of primers: F, 5′-CTCTCCCGAACCACAAACCC-3′; R, 5′-CAGGTACCCATGCGCTAGAC-3′; and neo, 5′-GCTCGAATCAAGCTGATCCGG-3′. PCR genotyping of the Sry gene was performed as described (18).

Anti-Nrk Antibody

A cDNA for an internal region of mouse Nrk protein (amino acid residues 776–1083), not conserved in other germinal center kinase family kinases, was cloned into the plasmid pGEX6P-2 (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) to generate a GST fusion construct. The fusion protein was purified from Escherichia coli cells using glutathione-Sepharose affinity beads (GE Healthcare), and 200 μg of the protein was used to immunize each of two rabbits.

Histology and in Situ Hybridization

Placentas were dissected from pregnant mice and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. The tissues were gradually dehydrated in ethanol and embedded in paraffin. Sections were cut at 7 μm and subjected to H&E staining or in situ hybridization by standard procedures. For in situ hybridization, antisense and sense RNA probes for mouse trophoblast-specific protein-α and Nrk mRNAs (nucleotide 169–385 and 1263–2070 from the translation initiation sites, respectively) were labeled with digoxigenin-conjugated UTP (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland), and hybridized probes were detected by incubating the tissue sections with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-digoxigenin antibody (Roche Diagnostics) followed by incubation with nitro blue tetrazolium chloride (Roche Diagnostics) and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate (Roche Diagnostics).

Immunofluorescence

After fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 5 h at 4 °C, placentas were cryoprotected with 30% sucrose in PBS, embedded in the Tissue-Tek OCT compound (Sakura Fine-technical, Tokyo, Japan), and sectioned at 10 μm using a cryostat. Sections were re-fixed, permeabilized in 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS, treated with 2 m HCl and 0.1% Triton X-100 for 1 h at 37 °C, and stained with anti-Nrk (1:100) or anti-Ki67 (1:100, Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO) antibody together with Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated phalloidin (1:100, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The secondary antibody was Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibody (1:500, Invitrogen). Fluorescent images were captured with a laser-scanning confocal microscope (Axiovert 200M, Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

RT-PCR

Total RNAs from mouse placentas were isolated using an ISOGEN RNA extraction kit (Nippon Gene, Tokyo, Japan). Human placenta was obtained at delivery, and poly(A)+ RNA was isolated as described (19). First-strand cDNAs were synthesized from 1 μg of RNAs using a ReverTra Ace-α kit (TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan) and used as templates for PCR. Primer sequences were: 5′-CGAAGACCATTCCGGCAGATTC-3′ and 5′-CTCAAAAGCCACAGAAGACGGTATG-3′ for mouse Nrk, and 5′-ATCTGGGCCACCTGCCGGAT-3′ and 5′-CCGCTGACCAGGGGGACTCA-3′ for human Nrk.

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblotting

Placentas, uteri, ovaries, and fetal membranes (amnion and yolk sac) were sonicated using a Sonifier 250 (Branson, Danbury, CT) for 10–60 s in 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 140 mm NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.1% SDS, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm PMSF, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, and 1 μg/ml pepstatin A. After centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C, the supernatants were either directly used for immunoblotting (70 μg of proteins) with anti-Nrk (1:500) and anti-α-tubulin (1:20,000, Sigma) antibodies or immunoprecipitated with 3 μl of anti-Nrk antibody coupled to protein A-Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare). The immunoprecipitates were used for immunoblotting. The secondary antibodies were peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG and anti-rabbit IgG antibodies (GE Healthcare). Blots were detected using ECL Western blotting Detection Reagents (GE Healthcare).

Uterine Transfer of Mouse Embryos

Isolation and uterine transfer of mouse embryos were performed as described (18). Briefly, eight-cell-stage embryos were isolated from the oviducts of pregnant mice at ∼2.5 dpc and incubated in Brinster's BMOC-3 medium (Invitrogen) for ∼24 h at 37 °C. The embryos (blastocysts) were transferred to the uteri of pseudo-pregnant WT Slc:ICR mice (Sankyo Labo Service, Tokyo, Japan) at 2.5 dpc after mating with vasectomized mice.

Measurement of Hormone Levels

Blood was collected from the abdominal aorta of mice, and EDTA was added to a final concentration of 3 mm. The blood was centrifuged at 2,000 g for 20 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant (i.e. the plasma) was recovered. Placentas were sonicated in ethanol using a Sonifier 250 and centrifuged at 700 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatants were evaporated and re-suspended in the assay buffer. The plasma concentrations of progesterone and estradiol were measured by LC-MS/MS at ASKA Pharma Medical (Kawasaki, Japan) (20, 21) and confirmed using ELISA kits (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI). The placental levels of progesterone and estradiol were measured using the ELISA kits.

Statistical Analysis

The Student's t test was used for statistical analysis.

RESULTS

Generation of Nrk-null Mice

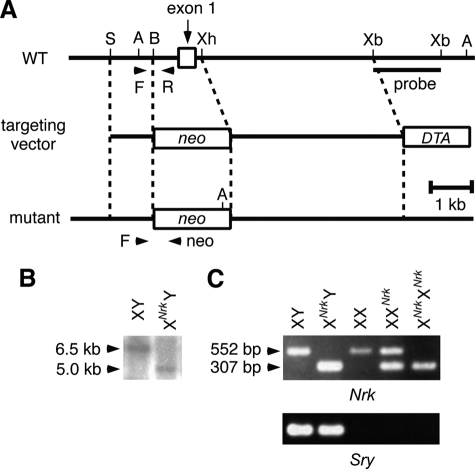

The first exon of Nrk was replaced by the neo cassette in 129/S4 mouse ES cells (Fig. 1A). Although the ES cell line was male harboring a single X chromosome, hemizygous Nrk-null ES cells grew normally and derived germ line chimeras when injected into mouse blastocysts. Chimeric mice were obtained from two Nrk-null ES cell clones, and mice derived from the two mutant clones exhibited the same phenotypes in this study.

FIGURE 1.

Generation of Nrk-null mice. A, schematic structure of the Nrk targeting vector, as well as of the WT and Nrk-null alleles. Arrowheads (F, R, and neo) indicate the positions of PCR primers used for genotyping in C. DTA, diphtheria toxin A gene; neo, neo-resistance gene; A, AccI; B, BamHI; S, SpeI; Xb, XbaI; Xh, XhoI. The position of the probe used for Southern blotting in B is also indicated. B, genomic DNAs from WT and XNrkY mouse ES cells were digested with AccI and examined by Southern blotting using the XbaI-XbaI fragment within intron 1 as a probe. The WT and mutant alleles yielded 6.5- and 5.0-kb fragments, respectively. C, PCR genotyping using tail DNAs from XY, XNrkY, XX, XXNrk, and XNrkXNrk mice as templates (top). This PCR amplified 552- and 307-bp fragments from the WT and mutant alleles, respectively. The sex of mice was confirmed by PCR of the Sry gene in the male-specific Y chromosome (bottom).

Backcrossing of the chimeric mice to C57BL/6J mice (>11 generations) resulted in the production of healthy XNrkY males and XXNrk females (XNrk designates an X chromosome carrying the Nrk mutation; the maternally derived X chromosome is designated first), intercrossing of which generated healthy XNrkXNrk females. However, although apparently normal Nrk-null (XNrkY and XNrkXNrk) offspring were recovered at the Mendelian ratio at birth, their ratio was lower than expected at ∼2 weeks of age (supplemental Table S1). These results suggested neonatal death of a population of Nrk-null mice, the reason for which is currently unknown. Nrk-null mice that survived the neonatal period appeared normal and were fertile, indicating that Nrk is not necessarily required for embryogenesis and postnatal life in mice.

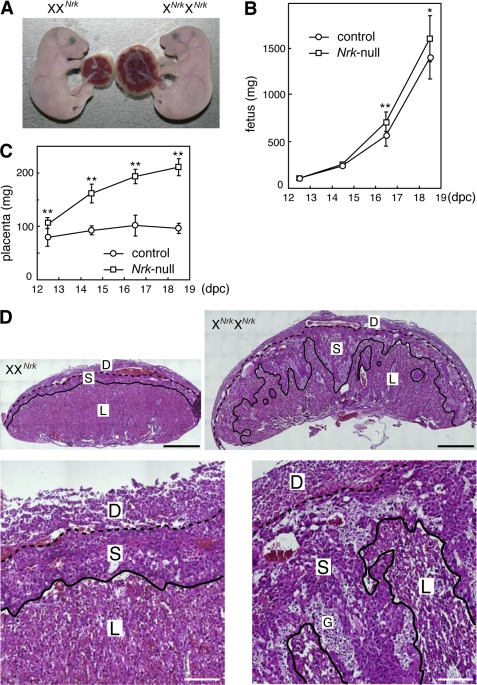

Nrk Is Required for Placental Development

Nrk-null fetuses were mostly normal at 18.5 dpc (Fig. 2A), although their weight was slightly, but statistically significantly, higher than that of WT and XXNrk fetuses at late gestation (Fig. 2B). In contrast, their accompanied placentas were significantly larger (∼2.4-fold in weight) than control placentas at 18.5 dpc (Fig. 2A). The difference in placental size was detectable at 12.5 dpc and became greater at later gestation periods (Fig. 2C). The mouse placenta is mainly composed of the decidual, spongiotrophoblast, and labyrinth layers (22, 23). Although the decidual layer is maternally derived, the other two are of fetal origin. Histological analysis showed that in Nrk-null placenta, the spongiotrophoblast layer is larger and invades into the labyrinth layer (Fig. 2D).

FIGURE 2.

Nrk is required for placental development. A, control (XXNrk) and Nrk-null (XNrkXNrk) fetuses and placentas at 18.5 dpc. B and C, the weight of control (XY, XX, or XXNrk) and Nrk-null (XNrkY or XNrkXNrk) fetuses (B) and placentas (C) at 12.5–18.5 dpc. The mean ± S.D. are shown (n = 5 for 12.5 dpc, n > 15 for 14.5–18.5 dpc). p < 0.05 (*) and 0.005 (**). D, H&E staining of control (XXNrk) and Nrk-null (XNrkXNrk) placentas at 18.5 dpc at low (top) and high (bottom) magnification. D, decidual layer; S, spongiotrophoblast layer; L, labyrinth layer; G, glycogen cells in the spongiotrophoblast layer. The three layers are divided by broken and solid lines. Bars, 1 mm (top) and 200 μm (bottom).

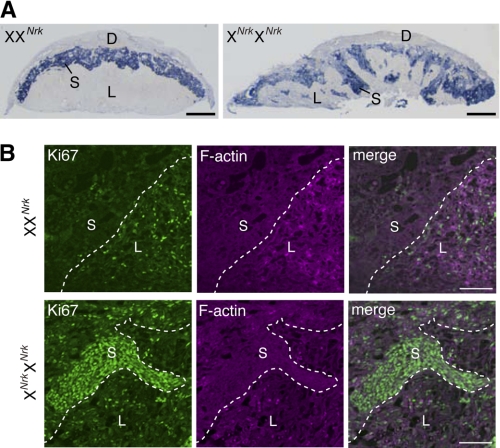

Nrk Terminates the Proliferation of Spongiotrophoblasts

In situ hybridization analysis of placental sections for trophoblast-specific protein-α, a marker for the spongiotrophoblast layer (24), confirmed that the Nrk-null spongiotrophoblast layer is enlarged and protruding into the labyrinth layer at 18.5 dpc (Fig. 3A). Immunofluorescence staining for Ki67 protein, a marker for proliferating cells (25), detected Ki67-positive cells in the spongiotrophoblast layer of Nrk-null, but not WT, placentas at 14.5 dpc (Fig. 3B). Particularly, cells that are invading into the labyrinth layer were strongly stained. In the labyrinth layer, the proportion of Ki67-positive cells was comparable between WT and Nrk-null tissues (Fig. 3B). In contrast, the TUNEL assay in placental sections showed no sign of reduced apoptosis levels in Nrk-null tissues (data not shown). These results suggested that Nrk disruption leads to overproliferation of the spongiotrophoblast layer cells (i.e. spongiotrophoblasts as well as glycogen cells, which are believed to be a subtype of spongiotrophoblast (23)).

FIGURE 3.

Nrk terminates the proliferation of spongiotrophoblasts. A, in situ hybridization analysis of trophoblast-specific protein-α mRNA in control (XXNrk) and Nrk-null (XNrkXNrk) placentas at 18.5 dpc. B, immunofluorescence staining of Ki67 protein in control (XXNrk) and Nrk-null (XNrkXNrk) placentas at 14.5 dpc. Cryosections were stained with anti-Ki67 antibody (green) and phalloidin (magenta). Merged images are also shown (right). D, decidual layer; S, spongiotrophoblast layer; L, labyrinth layer. Bars, 1 mm (A) and 100 μm (B).

In cultured cells, Nrk overexpression is reported to induce actin polymerization (16). However, phalloidin staining showed the level of F-actin in Nrk-null spongiotrophoblast layers to be comparable to that in WT tissues (Fig. 3B, see also Fig. 4D below). Overexpressed Nrk in cultured cells is also reported to activate the JNK pathway (12). Immunoblotting of placental lysates for Thr183/Tyr185-phosphorylated JNK, however, detected no significant difference in the level of JNK phosphorylation between WT and Nrk-null tissues (data not shown).

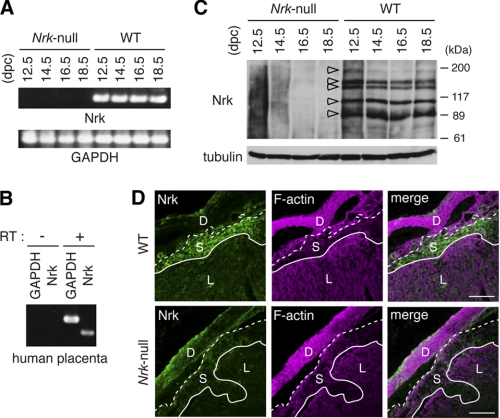

FIGURE 4.

Nrk is expressed in placenta. A, RT-PCR analysis of Nrk mRNA in mouse placenta at indicated gestation periods (top). GAPDH mRNA was also examined (bottom). B, RT-PCR analysis of Nrk mRNA in human placenta, using RT-treated (+) or untreated (−) human placenta RNAs as templates. C, immunoprecipitation/immunoblot analysis of Nrk protein with anti-Nrk antibody in mouse placenta at indicated gestation periods (top). Open arrowheads indicate bands representing Nrk proteins. Placental lysates were also blotted with anti-α-tubulin antibody (bottom). D, immunofluorescence staining of Nrk protein in mouse placenta. Cryosections of WT and Nrk-null (XNrkXNrk) placentas were stained with anti-Nrk antibody (green) and phalloidin (magenta). Merged images are also shown (right). D, decidual layer; S, spongiotrophoblast layer; L, labyrinth layer. Bars, 200 μm.

Nrk Is Expressed in the Placenta

Because Nrk expression has not been tested in the placenta, we examined it at the mRNA and protein levels. RT-PCR analysis showed Nrk mRNA expression in WT, but not Nrk-null, mouse placentas at 12.5–18.5 dpc (Fig. 4A). RT-PCR also showed that Nrk is expressed in human placenta obtained at delivery (Fig. 4B). Immunoprecipitation of mouse placental lysates with anti-Nrk antibody, followed by immunoblotting of the precipitates with the same antibody, detected five (∼180-, 140-, 130-, 110-, and 90-kDa) bands in WT, but not Nrk-null, tissues at 12.5–18.5 dpc (Fig. 4C, open arrowheads). Because mouse Nrk is a 1455-amino acid protein of 167 kDa, the ∼180-kDa band probably represents the full-length version. Because the germinal center kinase family kinases (26–28), including Nrk expressed ectopically in cultured cells (15), undergo caspase-mediated cleavage, the smaller bands possibly represent proteolytically processed forms. Immunostaining of placental sections with anti-Nrk antibody (Fig. 4D), but not a pre-immune serum (data not shown), detected Nrk protein in the spongiotrophoblast layer of WT, but not Nrk-null, placentas. This indicated that specific Nrk expression occurs in the spongiotrophoblast layer. This expression pattern was confirmed at the mRNA level by in situ hybridization (see Fig. 5C below).

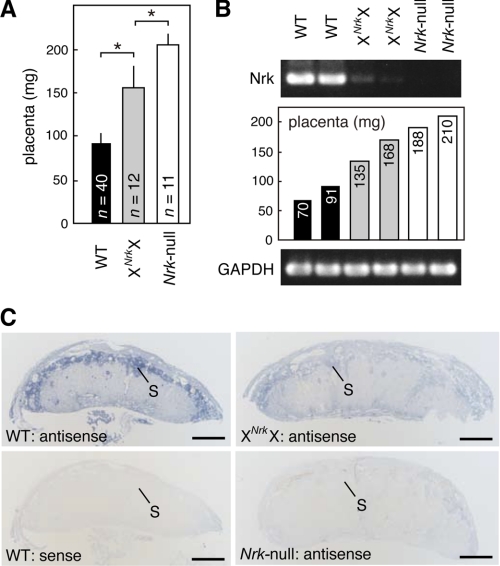

FIGURE 5.

Paternally derived Nrk is preferentially but incompletely inactivated in placenta. A, the weight of WT (XY or XX), XNrkX, and Nrk-null (XNrkY) placentas at 18.5 dpc. The mean ± S.D. values are shown. Numbers (n) of placentas examined are indicated. *, p < 0.0001. B, RT-PCR analysis of Nrk mRNA in XNrkX placentas at 18.5 dpc (top). The weight of each placenta is shown (middle). C, in situ hybridization analysis of Nrk mRNA in WT (XX), XNrkX, and Nrk-null (XNrkY) placentas at 18.5 dpc. S, spongiotrophoblast layer. Bars, 1 mm.

Paternally Derived Nrk Is Preferentially but Incompletely Inactivated in the Female Placenta

In the female mouse placenta, the paternally derived X chromosome undergoes preferential inactivation (29, 30). We therefore examined whether paternally derived Nrk is functionally inactivated in XNrkX placentas obtained by crossing XXNrk females to WT males. When isolated at 18.5 dpc, XNrkX placentas harboring paternal WT Nrk were larger (∼1.7-fold heavier) than WT littermate tissues (Fig. 5A; see also supplemental Fig. S1A), with overgrowth of the spongiotrophoblast layer being observed in Nrk-null tissues (supplemental Fig. S1, B and C). These results suggested that paternal Nrk is preferentially inactivated in the female placenta. However, XNrkX placentas were not as large as Nrk-null placentas, which were ∼2.2-fold heavier than WT tissues (Fig. 5A, see also Fig. 2C).

Since some X-linked genes have been shown to partially escape silencing in the inactive X chromosome (31, 32), Nrk mRNA expression was examined in XNrkX placentas at 18.5 dpc. RT-PCR analysis detected a significantly lower level of Nrk expression in XNrkX placentas (n = 7 from five litters) than in WT placentas (n = 8 from five litters) (Fig. 5B and data not shown). By in situ hybridization, the spongiotrophoblast layer was specifically stained for Nrk mRNA in WT, but not Nrk-null, placentas (Fig. 5C). Consistent with the results of the RT-PCR experiments in Fig. 5B, a low level of Nrk staining was detected in the spongiotrophoblast layer in XNrkX placentas (Fig. 5C). These results suggested that the weak phenotype in XNrkX placentas is due to limited Nrk expression from the paternally derived WT X chromosome.

Fetoplacental Nrk Is Required for Labor

When XXNrk females were mated to XNrkY males, both normal (XY and XXNrk) and Nrk-null offspring were delivered at term (∼19 dpc) (supplemental Table S1), indicating that when accompanied by normal littermates, Nrk-null offspring were delivered normally. Therefore, the large size of Nrk-null placentas does not physically interfere with delivery. In the Nrk-null intercross (XNrkY x XNrkXNrk), however, normal labor was observed only once in 56 cases (Fig. 6A). In 19 cases, Nrk-null dams died without delivery, but with dead fetuses in utero, at 20–22 dpc. In 29 cases, they exhibited delayed delivery of all dead offspring at 20–22 dpc. In seven cases, they initiated delivery of 1–3 live offspring at ∼20–21 dpc, but the rest of the offspring were delivered dead subsequently. The death of the fetuses was probably secondary to delayed delivery, because all the Nrk-null fetuses were alive and appeared normal at 19.5 dpc in the Nrk-null intercross (data not shown). In this experiment, not only the dams but also all the fetuses and placentas were Nrk-null, indicating that either maternal or fetoplacental Nrk is required for labor. We then mated Nrk-null (XNrkXNrk) females to WT males, giving rise to XNrkY and XNrkX fetuses/placentas in utero. As shown in Fig. 6A, Nrk-null dams successfully gave birth in 11 of 17 cases and failed in six cases. This partial defect suggested that maternal Nrk is not essential, whereas placental rather than fetal Nrk is responsible, for labor induction (see “Discussion”).

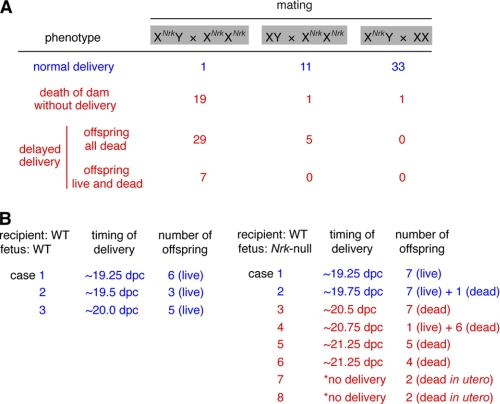

FIGURE 6.

Fetoplacental Nrk is required for labor. A, labor phenotype in WT and Nrk-null dams mated to WT or Nrk-null male mice. Numbers of cases of normal (blue) and failed (red) labor are indicated. B, timing of delivery and number of offspring in recipient WT dams transplanted with WT or Nrk-null blastocysts. *, dams did not deliver offspring and were dissected at 22.75 dpc to examine fetuses in utero.

To further examine the requirement for fetoplacental Nrk in labor, we transplanted Nrk-null fetuses into WT dams. Eight-cell-stage Nrk-null embryos, derived from the Nrk-null intercross, were isolated at ∼2.5 dpc, cultured for ∼24 h in vitro to allow development to blastocysts, and transferred to the uteri of pseudo-pregnant WT mice (9–11 blastocysts per recipient). As a control, recipients that received WT blastocysts delivered live offspring normally at term (by 20.0 dpc for pseudo-pregnant mice) (Fig. 6B). By contrast, six of eight recipients that received Nrk-null blastocysts exhibited a delayed delivery of dead offspring (Fig. 6B), indicating that fetoplacental Nrk is mainly responsible for labor induction. However, two recipients delivered live Nrk-null offspring at term (Fig. 6B). The reason for this is unclear, but it is unlikely that maternal Nrk compensated for the loss-of-function of fetoplacental Nrk, because Nrk is not expressed in any adult tissues tested in mice (11, 12) (see also Fig. 7 below).

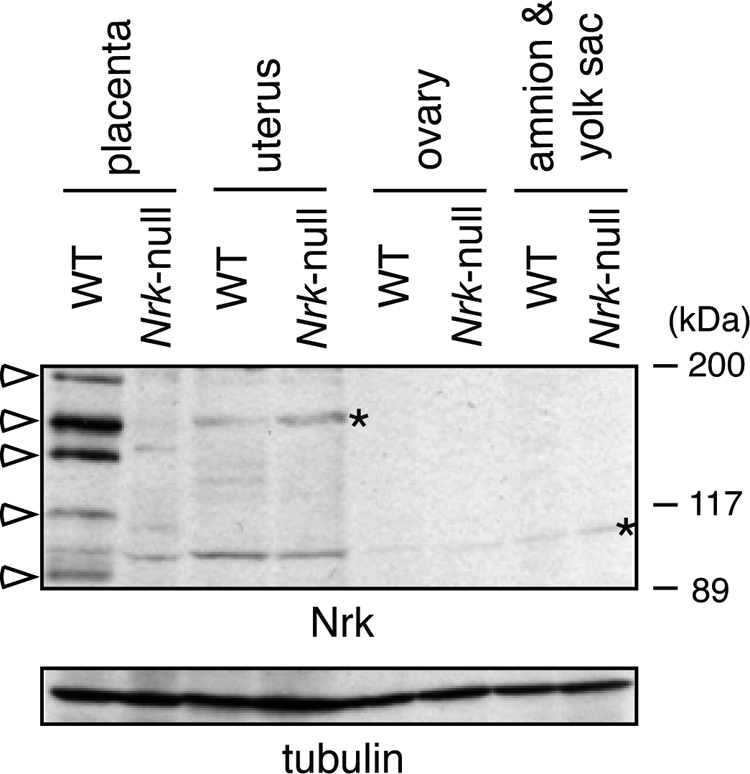

FIGURE 7.

Nrk is not expressed in reproductive tissues other than placenta. Immunoblot analysis of Nrk protein with anti-Nrk antibody in the lysates of WT and Nrk-null mouse reproductive tissues at 18.5 dpc (top) is shown. The lysates were also blotted with anti-α-tubulin antibody (bottom). Open arrowheads and asterisks indicate Nrk and nonspecific bands, respectively.

Nrk Is Not Expressed in Reproductive Tissues Other Than the Placenta

Nrk expression in female reproductive tissues has not been tested. We therefore performed immunoblot analysis of Nrk protein in the WT and Nrk-null uterus and ovary, as well as fetal membranes, including the amnion and yolk sac, in pregnant mice at 18.5 dpc. When lysates of these tissues, containing the same amount of total proteins, were blotted with anti-Nrk antibody, only nonspecific bands, which were also detected in Nrk-null tissues, were detected in the WT uterus, ovary, and fetal membranes (Fig. 7, asterisks) in an experimental condition where placental Nrk was clearly detected (Fig. 7, open arrowheads).

Nrk Controls Neither Progesterone Withdrawal nor Estrogen Drive

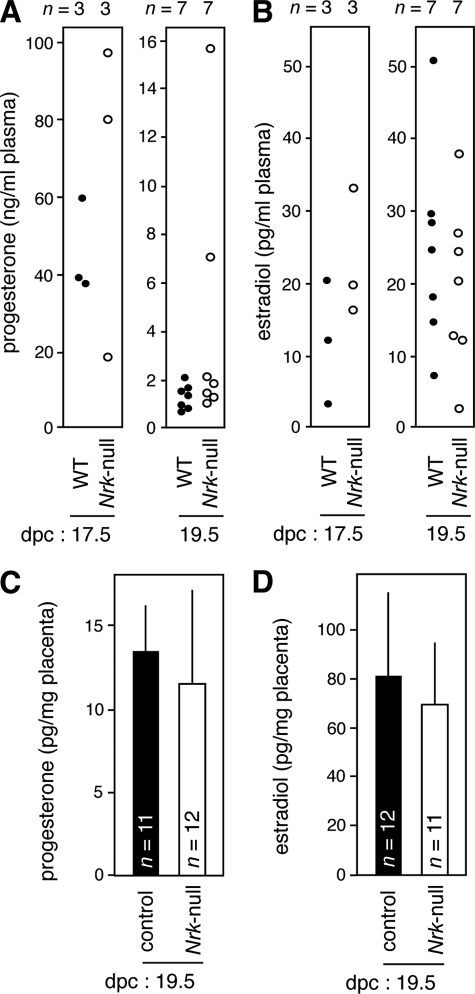

To examine whether the labor defect in Nrk-null mice is due to a dysregulated level of progesterone or estrogen, we measured the concentration of these hormones in the plasma of Nrk-null dams mated to Nrk-null males. Measurements using LC-MS/MS (20, 21) (Fig. 8A) and ELISA (data not shown) both showed that similar in WT dams carrying WT fetuses, a drastic decrease in the progesterone level was observed in Nrk-null dams carrying Nrk-null fetuses: whereas the level ranged between ∼20 and ∼100 ng/ml at 17.5 dpc, it ranged between ∼1 and ∼2 ng/ml in five of seven mice at 19.5 dpc. In two cases, the level was irregularly high but not as high as that at 17.5 dpc. These progesterone levels were consistent with those previously reported in pregnant mice (33, 34). The plasma estradiol level was also comparable between the WT and Nrk-null conditions at 17.5 and 19.5 dpc (ranging from ∼3 to ∼ 50 pg/ml) (Fig. 8B). The estrogen levels were consistent with those reported in mice (33, 34) and, as shown previously (34), not elevated at 19.5 dpc compared with that at 17.5 dpc. We also measured the levels of these hormones in the placenta using ELISA. The levels of progesterone (Fig. 8C) and estradiol (Fig. 8D) were similar between control (XY and XXNrk) and Nrk-null placentas at 19.5 dpc. These results suggested that the labor defect in the absence of Nrk is not primarily due to a failure in progesterone withdrawal or estrogen drive.

FIGURE 8.

Nrk does not regulate the levels of progesterone and estrogen. A and B, the levels of progesterone (A) and estradiol (B) in the plasma of dams were measured at 17.5 and 19.5 dpc using LC-MS/MS. WT, WT dams with WT fetuses; Nrk-null, Nrk-null dams with Nrk-null fetuses. Each dot represents a single plasma sample. Numbers (n) of samples examined are indicated (top). p = 0.48 (A, 17.5 dpc), 0.16 (A, 19.5 dpc), 0.19 (B, 17.5 dpc), 0.47 (B, 19.5 dpc). C and D, the levels of progesterone (C) and estradiol (D) in control (XY or XXNrk) and Nrk-null (XNrkY or XNrkXNrk) placentas were measured at 19.5 dpc using ELISA. The mean ± S.D. values are shown. Numbers (n) of placentas examined are indicated. p = 0.33 (C) and 0.37 (D).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we show that Nrk is expressed in the spongiotrophoblast layer, a fetus-derived region in the placenta, and is required for its development. We also show that fetoplacental Nrk is required for labor of the dam, providing the first genetic evidence for fetoplacental induction of labor. Collectively, we suggest a novel, X-linked and protein kinase-mediated signaling for labor induction, which is possibly derived from the placenta.

Role of Nrk in Placental Development

In the fetus, Nrk is shown to be expressed predominantly in the skeletal muscle (11). In contrast to the drastic morphological defect in Nrk-null placentas, however, embryonic development appeared mostly normal in Nrk-null mice (Fig. 2). Although Nrk-null fetuses were slightly larger than WT fetuses (Fig. 2) and a population of Nrk-null mice died neonatally (supplemental Table S1) for unknown reasons, those that survived the neonatal stage were apparently normal and fertile. In addition, Nrk is not expressed in any adult tissues tested in mice (11, 12) (Fig. 7). Thus, the predominant Nrk-null phenotype in the placenta and Nrk expression pattern suggest that Nrk plays a major role in the placenta. Because Nrk was restrictedly expressed in the spongiotrophoblast layer (Figs. 4 and 5), which was specifically overgrown in Nrk-null placentas (Figs. 2 and 3), Nrk negatively regulates the proliferation of spongiotrophoblasts in a cell-autonomous fashion. Currently, it is unknown whether the large fetal size and neonatal death of Nrk-null mice is secondary to the placental defect.

In experiments using cultured mammalian cells in which Nrk was ectopically expressed, Nrk has been reported to activate the JNK pathway (12), promote apoptosis in a kinase-independent manner (15), and regulate the actin cytoskeleton by phosphorylating an actin-depolymerizing protein, cofilin (16). However, we failed to find changes in the levels of JNK phosphorylation, TUNEL staining, and phalloidin staining in Nrk-null placentas (Figs. 3 and 4, and data not shown). Further study is necessary to understand the molecular mechanism underlying the regulation of spongiotrophoblasts by Nrk. However, the same phenotype (i.e. placentomegaly caused by the protrusion of overproliferated spongiotrophoblasts into the labyrinth layer) was previously reported for mice lacking the X-linked homeobox gene Esx1 (35) and mice cloned from somatic cells (36). Therefore, Nrk and Esx1 may participate in the same signaling pathway that regulates placental development. In addition, Nrk expression may be reduced in the placenta of mice generated by somatic cell cloning, a possibility consistent with specific down-regulation of a number of X-linked genes in the cloned mouse embryo (37).

Inactivation of Paternally Derived Nrk in Placenta

In eutherian mammals, including mice, the paternally derived X chromosome is preferentially inactivated in the female placenta (29, 30). Therefore, female placentas heterozygous for mutations in X-linked genes such as Esx1 (35) and Cited1 (38) exhibit the same phenotype as placentas null for the genes when WT alleles are paternally derived. Consistently, XNrkX placentas also exhibited the phenotype observed in Nrk-null tissues (Fig. 5 and supplemental Fig. S1). Interestingly, however, the phenotype was milder than that in Nrk-null tissues. Concomitantly, a slight amount of Nrk mRNA was detected in XNrkX placentas. These results indicate that the phenotype is ameliorated in XNrkX placentas by a partial escape of the paternally derived Nrk from X inactivation. No such amelioration was reported in the Esx1 and Cited1 heterozygous mutant mice (35, 38). Our results thus present the first case in which a partial escape of an X-linked gene from paternal X inactivation generates a functional gene product in the placenta.

Role of Nrk in Labor

Pregnant mice exhibited a severe defect in labor when all the fetuses and placentas were Nrk-null in utero (Fig. 6). Together with the finding that Nrk is not expressed in any adult tissues examined (11, 12) (Fig. 7), these results suggest that Nrk in the fetus or placenta is required for labor of the dam. The drastic placental, but not fetal, phenotype upon Nrk disruption suggests a role for placental, rather than fetal, Nrk in labor induction. The skeletal muscle-specific Nrk expression in the fetus (11) may also argue against a role for fetal Nrk in the process. This possibility is further supported by the following observation. When Nrk-null females were mated to WT males and carried XNrkY and XNrkX fetuses/placentas in utero, they completed labor normally in eleven cases and failed to do so in six cases (Fig. 6). This partial defect can be explained if placental Nrk, which is weakly expressed in XNrkX placentas, is responsible for labor induction. If maternal Nrk is responsible, Nrk-null dams in this experiment would also exhibit a labor defect in most cases as when crossed to Nrk-null males. If fetal Nrk is responsible, normal labor would be expected in most cases, because XNrkX fetuses express Nrk (paternal and maternal X chromosomes are randomly inactivated in the fetus). Finally, if placental Nrk is responsible, Nrk-null dams would or would not exhibit a defect depending on the intrauterine number of XNrkX placentas expressing a low level of Nrk: when the number of XNrkX placentas is high, the total placental level of Nrk expression may exceed the threshold required for labor induction, whereas when the number is low, the total Nrk level may be below the threshold. In addition, because the levels of overgrowth and Nrk mRNA expression varied considerably in different XNrkX placentas (Fig. 5), the total placental Nrk level would also be affected by the degree of escape of WT Nrk from X inactivation in individual XNrkX placentas. Collectively, we suggest that Nrk in the placental spongiotrophoblast layer plays a critical role in labor induction.

A possible mechanism for Nrk-mediated labor induction is that Nrk promotes the production of an unidentified soluble factor that is secreted from the placenta and acts on the dam. Because our knowledge of the molecular function of Nrk is limited (12, 15, 16), further study is necessary to understand the role of Nrk in labor induction. Nrk-null mice will provide a powerful tool for elucidating the precise mechanism of this feto-maternal interaction. The mechanisms of labor induction differ considerably between species, including humans, sheep, and mice (4, 9). Therefore, it is also important to know whether Nrk participates in the labor induction of other eutherian mammals. We, however, found the levels of progesterone and estrogen to be unaffected in Nrk-null dams carrying Nrk-null fetuses (Fig. 8). These results suggest that Nrk does not act upstream of the actions of these hormones in labor. In contrast to many mammalian species, including mice, humans maintain a high maternal level of circulating progesterone throughout pregnancy (2, 3). The observation that Nrk does not participate in progesterone withdrawal, which does not occur in humans, together with the expression of Nrk mRNA in the human placenta (Fig. 4), suggest that Nrk-mediated signaling may also operate in human labor. Nrk therefore serves as a potential target to therapeutically control human labor.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Y. Sugimoto and I. Kii for discussions, M. Makita and R. Udagawa for help with gene targeting in ES cells, S. Honma for help with LC-MS/MS, and M. Tamai for help with keeping the mice.

This work was supported by Grants-in-aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan (Grants 21025011 and 21113505 to M. K.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Fig. S1 and Table S1.

- CRH

- corticotropin-releasing hormone

- dpc

- days postcoitum

- SP-A

- surfactant protein-A

- Nrk

- Nik-related kinase.

REFERENCES

- 1. Muglia L. J., Katz M. (2010) N. Engl. J. Med. 362, 529–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mesiano S., Welsh T. N. (2007) Semin Cell Dev. Biol. 18, 321–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vidaeff A. C., Ramin S. M. (2008) Curr. Med. Chem. 15, 614–619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nathanielsz P. W. (1996) Am. Sci. 84, 562–569 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mendelson C. R. (2009) Mol. Endocrinol. 23, 947–954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Muglia L., Jacobson L., Dikkes P., Majzoub J. A. (1995) Nature 373, 427–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Condon J. C., Jeyasuria P., Faust J. M., Mendelson C. R. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 4978–4983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Korfhagen T. R., Bruno M. D., Ross G. F., Huelsman K. M., Ikegami M., Jobe A. H., Wert S. E., Stripp B. R., Morris R. E., Glasser S. W., Bachurski C. J., Iwamoto H. S., Whitsett J. A. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 9594–9599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mitchell B. F., Taggart M. J. (2009) Am. J. Physiol. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 297, R525-R545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ratajczak C. K., Muglia L. J. (2008) Pediatr. Res. 64, 581–589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kanai-Azuma M., Kanai Y., Okamoto M., Hayashi Y., Yonekawa H., Yazaki K. (1999) Mech. Dev. 89, 155–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nakano K., Yamauchi J., Nakagawa K., Itoh H., Kitamura N. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 20533–20539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kyriakis J. M. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 5259–5262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dan I., Watanabe N. M., Kusumi A. (2001) Trends Cell Biol. 11, 220–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kakinuma H., Inomata H., Kitamura N. (2005) Cell. Signal. 17, 1439–1448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nakano K., Kanai-Azuma M., Kanai Y., Moriyama K., Yazaki K., Hayashi Y., Kitamura N. (2003) Exp. Cell Res. 287, 219–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Komada M., Soriano P. (1999) Genes Dev. 13, 1475–1485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hogan B., Beddington R., Constantini F., Lacy E. (1994) Manipulating the Mouse Embryo: A Laboratory Manual, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 19. Miyazawa K., Tsubouchi H., Naka D., Takahashi K., Okigaki M., Arakaki N., Nakayama H., Hirono S., Sakiyama O., Takahashi K., Gohda E., Daikuhara Y., Kitamura N. (1989) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 163, 967–973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kutsukake N., Ikeda K., Honma S., Teramoto M., Mori Y., Hayasaka I., Yamamoto R., Ishida T., Yoshikawa Y., Hasegawa T. (2009) Am. J. Primatol. 71, 696–706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Arai S., Miyashiro Y., Shibata Y., Kashiwagi B., Tomaru Y., Kobayashi M., Watanabe Y., Honma S., Suzuki K. (2010) Steroids 75, 13–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rossant J., Cross J. C. (2001) Nat. Rev. Genet 2, 538–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cross J. C. (2005) Placenta 26, S3-S9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lescisin K. R., Varmuza S., Rossant J. (1988) Genes Dev. 2, 1639–1646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Scholzen T., Gerdes J. (2000) J. Cell Physiol. 182, 311–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Graves J. D., Gotoh Y., Draves K. E., Ambrose D., Han D. K., Wright M., Chernoff J., Clark E. A., Krebs E. G. (1998) EMBO J. 17, 2224–2234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chen Y. R., Meyer C. F., Ahmed B., Yao Z., Tan T. H. (1999) Oncogene 18, 7370–7377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sabourin L. A., Tamai K., Seale P., Wagner J., Rudnicki M. A. (2000) Mol. Cell Biol. 20, 684–696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Reik W., Lewis A. (2005) Nat. Rev. Genet. 6, 403–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hemberger M. (2007) Cell Mol. Life Sci. 64, 2422–2436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Huynh K. D., Lee J. T. (2003) Nature 426, 857–862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Carrel L., Willard H. F. (2005) Nature 434, 400–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sugimoto Y., Yamasaki A., Segi E., Tsuboi K., Aze Y., Nishimura T., Oida H., Yoshida N., Tanaka T., Katsuyama M., Hasumoto K., Murata T., Hirata M., Ushikubi F., Negishi M., Ichikawa A., Narumiya S. (1997) Science 277, 681–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zeng Z., Velarde M. C., Simmen F. A., Simmen R. C. (2008) Biol. Reprod. 78, 1029–1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Li Y., Behringer R. R. (1998) Nat. Genet. 20, 309–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tanaka S., Oda M., Toyoshima Y., Wakayama T., Tanaka M., Yoshida N., Hattori N., Ohgane J., Yanagimachi R., Shiota K. (2001) Biol. Reprod. 65, 1813–1821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Inoue K., Kohda T., Sugimoto M., Sado T., Ogonuki N., Matoba S., Shiura H., Ikeda R., Mochida K., Fujii T., Sawai K., Otte A. P., Tian X. C., Yang X., Ishino F., Abe K., Ogura A. (2010) Science 330, 496–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rodriguez T. A., Sparrow D. B., Scott A. N., Withington S. L., Preis J. I., Michalicek J., Clements M., Tsang T. E., Shioda T., Beddington R. S., Dunwoodie S. L. (2004) Mol. Cell Biol. 24, 228–244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.