Abstract

Objective

To compare the relative effectiveness of systemic corticosteroids plus immunosuppression when indicated (systemic therapy) versus fluocinolone acetonide implant (implant therapy) for non-infectious intermediate, posterior or panuveitis (uveitis).

Design

Randomized controlled parallel superiority trial.

Participants

Patients with active/recently active uveitis.

Methods

Participants were randomized (allocation ratio 1:1) to systemic or implant therapy at 23 centers (three countries). Implant-assigned participants with bilateral uveitis were assigned to have each eye that warranted study treatment implanted. Treatment-outcome associations were analyzed by assigned treatment for all eyes with uveitis.

Main Outcome Measures

Masked examiners measured the primary outcome: change in best-corrected visual acuity from baseline. Secondary outcomes included patient-reported quality of life (QoL), ophthalmologist-graded uveitis activity, and local and systemic complications of uveitis or therapy. Reading Center graders and glaucoma specialists assessing ocular complications were masked. Participants, ophthalmologists, and coordinators were unmasked.

Results

Among 255 patients randomized to implant and systemic therapy (479 eyes with uveitis), evaluating changes from baseline to 24 months, the implant and systemic therapy groups respectively had +6.0 vs. +3.2 letters' improvement in visual acuity (p=0.16, 95% confidence interval on difference in improvement between groups: −1.2 to +6.7 letters, positive values favoring implant), +11.4 vs. +6.8 units' vision-related QoL improvement (p=0.043), +0.02 vs. −0.02 change in EuroQol-EQ5D health utility (p=0.060), and 12% vs. 29% had active uveitis (p=0.001). Over 24 months, implant-assigned eyes had a higher risk of cataract surgery (80%, hazard ratio (HR) = 3.3, p<0.0001), treatment for elevated intraocular pressure (61%, HR=4.2, p<0.0001), and glaucoma (17%, HR = 4.2, p=0.0008). Systemic-assigned patients had more prescription-requiring infections (0.60 vs. 0.36/person-year, p=0.034), without notable long-term consequences; systemic adverse outcomes otherwise were unusual in both groups, with minimal differences between groups.

Conclusion

In each treatment group, mean visual acuity improved over 24 months, with neither approach superior to a degree detectable with the study's power. Therefore, the specific advantages and disadvantages identified should dictate selection between the alternative treatments in consideration of individual patients' particular circumstances. Systemic therapy with aggressive use of corticosteroid-sparing immunosuppression was well-tolerated, suggesting that this approach is reasonably safe for local and systemic inflammatory disorders.

Introduction

Uveitis (intraocular inflammation) is an important cause of visual impairment.1;2 Intermediate, posterior, and panuveitis3;4 are the forms of uveitis most likely to cause vision loss.5;6 Because of its earlier onset, uveitis results in a longer duration of blindness and more economic cost per case than more common age-related ocular diseases.7

Systemic corticosteroids (supplemented, when indicated, by corticosteroid-sparing immunosuppressive drugs) have been the mainstay of treatment for chronic, vision-threatening cases of uveitis, based on their established advantages over alternative approaches, as was affirmed by an expert panel review of the subject conducted in 2000.8 In 2005, the United States Food and Drug Administration approved a surgically-placed intravitreal fluocinolone acetonide implant for treatment of intermediate, posterior, and panuveitis. The implant delivers corticosteroid intravitreally for approximately 3 years with minimal systemic absorption.9–11 The relative effectiveness and risk(s) of these alternative treatments require further characterization.

Here we report the primary 24-month results of a randomized, controlled comparative effectiveness trial to evaluate whether fluocinolone acetonide implant or systemic therapy for non-infectious intermediate, posterior, or panuveitis is superior. The study's aims were to compare visual outcomes, control of inflammation, incidences of local ocular and systemic complications of disease or therapy, and vision-related and general quality of life.

Methods

Study Design

The Multicenter Uveitis Steroid Treatment (MUST) Trial is a randomized (allocation ratio 1:1), partially masked, 23-center parallel treatment comparative effectiveness superiority trial (clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT00132691). A previous report details the design and outcome definitions used.12 All patients provided written informed consent; all governing institutional review boards provided approval.

The protocol was modified during early enrollment, broadening eligibility to improve recruitment and make results more generalizable (see Appendix 2, available at http://aaojournal.org).

Enrollment of Participants, Data Collection, and Follow-up

Eligible patients were age 13 years or older and had non-infectious intermediate, posterior or panuveitis in one or both eyes (active within ≤60 days) for which systemic corticosteroids were indicated. Patients requiring systemic therapy for non-ocular indications were excluded (see additionally Appendix 3). Eligible patients enrolled at 23 uveitis centers in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia. Patients completed study visits at baseline, one month, three months, and then every three months for at least 24 months (contiguous visit windows).

Random Treatment Assignment

Patients were randomized to implant or systemic therapy; patients with bilateral uveitis were assigned to receive implants in each eye meeting eligibility criteria. Randomization (1:1 ratio) was by variable length, permuted blocks within two strata (clinical center, intermediate vs. posterior or panuveitis), with assignments produced by Stata 11.0 (StataCorp. 2009, Stata Statistical Software: Release 11, College Station, TX: StataCorp LP). After data entry confirmed a subject's eligibility and stratum, the study website revealed the next treatment assignment.

Treatment

Implant therapy began by using topical, periocular, and/or systemic corticosteroids to suppress any anterior chamber inflammation. Surgical fluocinolone acetonide implant (0.59 mg, Bausch & Lomb, Rochester, NY) placement followed in the first eye within 28 days of randomization, and in the second eye (if indicated) within 28 additional days. Study-certified surgeons placed implants using a recommended technique.10;13 The protocol dictated tapering and discontinuation of any systemic corticosteroids and immunosuppressive drugs initially in use following implant placement. Re-implantation was specified for re-activations, but best medical judgment was permitted for initial failure to control inflammation, treatment-limiting toxicity, or incidence of systemic disease requiring systemic therapy. Second eyes for which implantation was not indicated could be managed using non-systemic treatments.12

Systemic therapy followed expert panel guidelines.8 Most cases had active inflammation at baseline and received 1 mg/kg/day up to 60 mg/day of prednisone until either the uveitis was controlled or four weeks had elapsed. After achieving control, prednisone was tapered per study guidelines. Cases already suppressed at baseline began by tapering from their initial prednisone dose. Immunosuppression was indicated for: 1) failure to initially control inflammation using corticosteroids; 2) corticosteroid-sparing in cases consistently reactivating prior to reaching a prednisone dose of 10 mg/day; and 3) specific high risk uveitis syndromes.8 When indicated, clinicians selected the approved immunosuppressant most suitable for each patient; administration and monitoring for toxicity followed guidelines.8

Uveitis experts regularly monitored treatment regimens for protocol compliance at site visits.

Outcomes and Masking

Study-certified visual acuity examiners measured best-corrected visual acuity as the number of letters read from standard logarithmic visual acuity charts;14 change in this measure from baseline to 24 months was the primary outcome. Other important outcomes reported here include visual field sensitivity (the mean deviation statistic15), clinically graded uveitis activity/control, ocular and systemic complications of uveitis or its treatment, and patient-reported vision- and general health-related quality of life and health utility (using the NEI-VFQ,16 SF-36,17;18 and EuroQol19 instruments respectively). In phakic eyes, cataract was graded by biomicroscopy; among eyes free of cataract at baseline, incident cataract was identified if biomicroscopy confirmed a cataract at two consecutive visits. All outcomes specifically reported herein were pre-specified by the protocol and tracked prospectively.

Other than at the 1 and 3 month visits, when post-operative signs were expected to be visible, visual acuity examiners were masked. A glaucoma specialist reviewed visual field, clinical data, and fundus photographs to diagnose glaucoma. A second glaucoma specialist independently confirmed all cases and a 32% random subset of non-cases; disagreements were adjudicated by consensus. Reading Center image evaluations for ocular sequelae of uveitis and of therapy, and glaucoma assessments all were masked. Patients, clinicians and coordinators were not masked.12

Sample Size Determination

Assuming bilateral disease in 67% of patients, a between eye correlation of 0.4, a standard deviation of 16 letters' change over two years, and a two-sided type 1 error rate of 0.05, a sample size of 250 provided 91% power (assuming 10% crossover) to detect a treatment difference of 7.5 standard ETDRS letters' change in visual acuity from baseline to 24 months, a difference similar to that which drove widespread use of expensive new retinal treatments in other trials which tested them.20;21 One interim analysis using the O'Brien-Fleming α-spending function22;23 was conducted; the nominal type 1 error rate was 0.049 for the final analysis.

Statistical Analyses

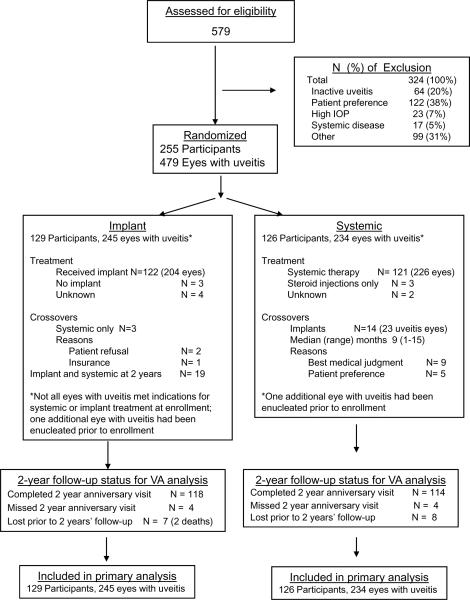

Analyses were conducted “as randomized.” Because all uveitic eyes (regardless of severity) are affected by systemic treatment, the primary analyses evaluated the ocular outcomes of all eyes having uveitis at enrollment in relation to treatment assignment, which included a small number of eyes with uveitis for which clinicians thought implant therapy was not indicated (Figure 1), given that outcomes of such eyes might have been affected by systemic therapy vs. lack of study therapy in the implant arm. Longitudinal models estimated parameters using generalized estimating equations (GEE).24 For visual acuity, a saturated means model (including indicators for each visit and each visit-by-treatment interactions) adjusting for stratification by uveitis type (intermediate versus posterior/panuvetis) was used; a Toeplitz covariance structure accounted for longitudinal, within eye correlation. All available visit information was incorporated into the model, with missing data indicators used to maintain the data structure. Other analyses for measured outcomes used the same mean structure with a Toeplitz, unstructured, or exchangeable covariance matrix. Event-time analyses were used to compare the incidence of adverse ocular and systemic outcomes. Analyses were conducted by the Statistical Analysis Committee (see Credit Roster, Appendix 1).

Figure 1.

CONSORT Diagram. VA=visual acuity; IOP=intraocular pressure

Robust standard errors were computed for all models. The bootstrap was used to calculate standard error, confidence intervals, and p values for outcomes where two eyes of the same individual were at risk (e.g., visual acuity in uveitic eyes). Bootstrap sampling was stratified by treatment group, unilateral vs. bilateral uveitis, and uveitis stratum (intermediate vs. posterior or panuveitis) with 5000 replicates. For analysis of sustained visual acuity impairment (defined as impairment at consecutive assessments) and similar outcomes, missing data were accommodated via multiple imputation.25 All reported confidence intervals and p-values are nominal and not adjusted for multiple comparisons. Statistical analyses used SAS (SAS/STAT User's Guide, Version 9.1, Cary, NC:SAS Institute), Stata 11, and R (The R Project for Statistical Computing, Version 2.11.1, http://www.r-project.org/, accessed July 14, 2011).

Results

Between December 2005 and December 2008, 255 patients (479 eyes with uveitis) were enrolled. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were distributed similarly between groups (see Table 1, available at http://aaojournal.org), with the following exceptions. Patients in the implant group were more likely to be osteopenic or osteoporotic (45% and 9% respectively) than patients in the systemic group (34% and 6% respectively). Eyes with uveitis in the implant group had poorer visual field sensitivity than those in the systemic group (median −5.7 dB vs −3.8 dB respectively); however, the two groups did not differ substantially in baseline visual acuity (median=68, interquartile range (IQR): 46–79) vs. 71 (IQR: 53–81) letters read respectively). The degree of uveitis activity at baseline was about the same in the two groups.

In the implant and systemic groups respectively 122/129 (95%) and 121/126 (96%) received their assigned therapies (Figure 1); 3 eyes of 2 patients required re-implantation within 24 months. In the systemic therapy group, 104 (86%) received corticosteroid-sparing immunosuppressive drugs as part of their treatment.

Among patients randomized, 232 (435 eyes with uveitis; 91%) completed visual acuity measurement at the 24 month follow-up visit. Overall, 4415 of 4790 study visits (92%) were completed for the primary outcome through 24 months.

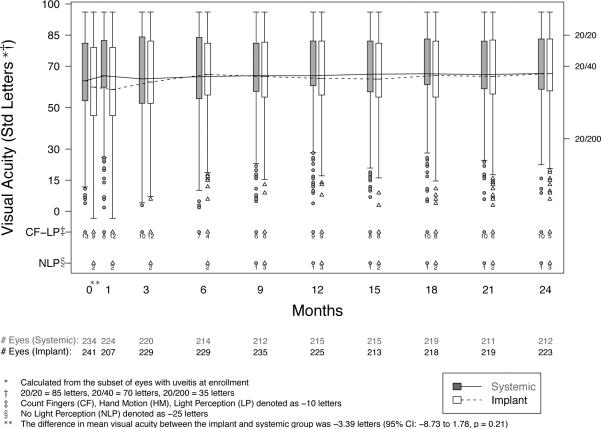

Visual Function

Both the implant and systemic groups experienced improvement of best-corrected visual acuity during follow-up—respectively a mean improvement from baseline in the respective groups of 5.9 vs. 2.0 letters (5 letters=1 Snellen-equivalent line) at 6 months, 4.6 vs. 3.3 letters at 12 months, and 6.0 vs. 3.2 letters at 24 months (Table 2 and Figure 2). There was no statistically significant difference between the treatment groups in their improvement in visual acuity at 24 months (p=0.16). By 24 months 21% vs. 13% of eyes with uveitis assigned to implant or systemic therapy, respectively, had gained at least 15 letters (3 lines) of visual acuity (p=0.065). Excluding eyes with visual acuity 20/40 or better at baseline, the mean improvement by 24 months was 12.9 and 9.3 letters, in the implant and systemic groups respectively (p=0.25). By-patient analyses evaluating the better and the worse eye also produced similar results. Visual acuity outcomes of each treatment group were similar regardless of phakic vs. pseudophakic or aphakic status at baseline (p=0.68 for lens status-treatment interaction).

Table 2.

Change in visual acuity over time for the implant and systemic treatment arms during the initial 2 years of follow-up (as-randomized analysis).

| Sample Size* | Estimate Mean(SE§) | Estimated Mean Change from Enrollment(SE§) | Estimated Treatment Effect† (95% CI§) | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Implant | Systemic | Implant | Systemic | Implant:Systemic | |||

| Primary Outcome: Visual acuity (letters read) | E= | ||||||

| Enrollment | 475 | 61.0(2.5) | 64.4(2.5) | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| 6 months | 443 | 66.9(2.3) | 66.4(2.6) | 5.88(1.07) | 1.97(1.14) | 3.91 (0.87, 7.02) | 0.014 |

| 12 months | 437 | 65.6(2.4) | 67.7(2.6) | 4.61(1.38) | 3.33(1.23) | 1.29 (−2.32, 5.01) | 0.49 |

| 24 months | 435 | 67.0(2.4) | 67.6(2.6) | 6.03(1.41) | 3.23(1.41) | 2.79 (−1.16, 6.68) | 0.16 |

|

| |||||||

| Visual acuity (letters read by the better eye) | N= | ||||||

| Enrollment | 254 | 71.3(2.3) | 75.4(2.0) | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| 6 months | 236 | 74.5(2.0) | 76.8(2.2) | 3.19(1.13) | 1.43(0.97) | 1.76 (−1.16, 4.68) | 0.24 |

| 12 months | 234 | 74.6(2.0) | 77.1(2.3) | 3.30(1.28) | 1.67(1.06) | 1.63 (−1.64, 4.89) | 0.33 |

| 24 months | 232 | 75.2(2.1} | 77.3(2.2) | 3.90(1.29) | 1.92(1.12) | 1.98 (−1.38, 5.35) | 0.25 |

Sample size = the number of eyes (E) or individuals (N) with data available at each visit.

SE = standard error, CI = confidence interval.

At each of the follow-up time points, the treatment effect is the model-based comparison of within treatment group change from enrollment (the difference of differences). A positive number favors implant.

Figure 2.

Distribution of visual acuity from baseline to 24 months in eyes with intermediate, posterior, or panuveitis assigned to implant or systemic therapy. CI=confidence interval

Overall visual field sensitivity, reduced in both groups at baseline (median mean deviation= −5.7 dB vs. −3.8 dB respectively), did not change appreciably in either group over 24 months (see Figure 3, available at http://aaojournal.org).

Uveitis Activity and Macular Edema

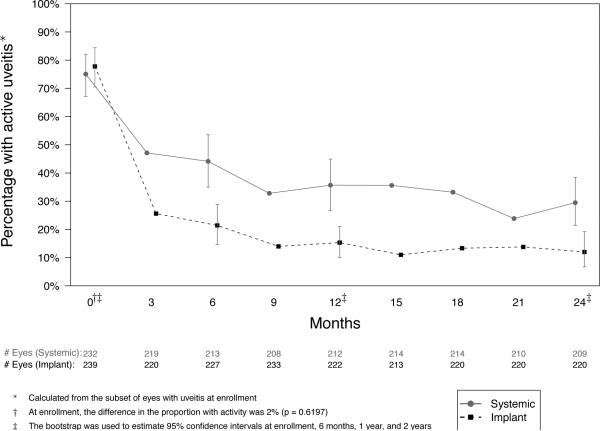

Most eyes with active uveitis at baseline were controlled within nine months in both groups. However, in the implant group, control of uveitis was more frequent (88% vs. 71% controlled at 24 months, p=0.001, Table 3, Figure 4), and the rate of achieving a two-step improvement in vitreous haze4 was more favorable (hazard ratio (HR)=1.47, p=0.014).

Table 3.

Proportion with active uveitis and with macular edema over time for the implant and systemic treatment arms during the initial 2 years of follow-up (as-randomized analysis).

| Sample Size* | Estimated Proportion with Condition (95%CI§) | Ratio of Odds Compared to Baseline Odds of Having Condition (95% CI) | Estimated Treatment Effect† (95% CI) | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Implant | Systemic | Implant | Systemic | Implant: Systemic | |||

| Uveitis Activity,% active | E= | ||||||

| 78% | 75% | ||||||

| Enrollment | 471 | (70%, 85%) | (67%, 83%) | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| 21% | 44% | 0.08 | 0.26 | 0.30 | |||

| 6 months | 440 | (14%, 29%) | (35%, 54%) | (0.04, 0.12) | (0.16, 0.41) | (0.15, 0.57) | < 0.001 |

| 15% | 36% | 0.05 | 0.18 | 0.28 | |||

| 12 months | 434 | (10%, 22%) | (26%, 45%) | (0.02, 0.09) | (0.11, 0.30) | (0.13, 0.56) | 0.001 |

| 12% | 29% | 0.04 | 0.14 | 0.29 | |||

| 24 months | 429 | (6%, 20%) | (21%, 39%) | (0.02, 0.07) | (0.08, 0.23) | (0.13, 0.60) | 0.001 |

|

| |||||||

| Macular edema, % | E= | ||||||

| 41% | 39% | ||||||

| Enrollment | 436 | (32%, 51%) | (32%, 51%) | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| 20% | 34% | 0.36 | 0.79 | 0.45 | |||

| 6 months | 398 | (13%, 28%) | (13%, 28%) | (0.23, 0.51) | (0.56, 1.11) | (0.27, 0.74) | 0.002 |

| 21% | 29% | 0.39 | 0.63 | 0.61 | |||

| 12 months | 385 | (14%, 29%) | (14%, 29%) | (0.25, 0.55) | (0.43, 0.90) | (0.35, 1.04) | 0.067 |

| 22% | 30% | 0.41 | 0.67 | 0.61 | |||

| 24 months | 403 | (14%, 30%) | (14%, 30%) | (0.26, 0.60) | (0.46, 0.96) | (0.34, 1.03) | 0.071 |

Sample size: the number of eyes with uveitis with available data at each visit.

CI = confidence interval, OR = odds ratio.

At each of the follow-up time points, is the ratio of odds ratios, with 95% CI. An odds ratio less than 1 favors implant.

Figure 4.

Percentage with active inflammation from baseline to 24 months in eyes with intermediate, posterior, or panuveitis assigned to implant or systemic therapy.

The proportion of eyes having macular edema (Stratus OCT-3 center point macular thickness ≥240μm)12 was similar for the two treatment groups at baseline. By six months, fewer had macular edema in the implant than the systemic group (20% vs. 34%, as opposed to 41% vs. 39% respectively at baseline (p<0.001 for comparison of change from baseline between groups). However, the proportions with macular edema by 24 months (22% vs. 30%) did not represent a substantial difference in change from baseline between groups (p=0.071).

Ocular and Systemic Complications

Relative to the systemic group, the implant group had a more than four-fold higher rate of (first) incidence of intraocular pressure (IOP) elevation of 10 mmHg or more, absolute IOP of 30 mmHg or more, and of needing medical and surgical treatments for elevated IOP (Table 4). Despite frequent medical and surgical intervention, glaucoma developed within 24 months in 17% vs. 4.0% (HR = 4.2, p=0.001) of uveitic eyes respectively. Among those at risk, the implant group also experienced higher cumulative 24 month risk of both cataract (91% vs 45%) and cataract surgery (80% vs 31%). These differences were consistent with respectively with the higher incidence of diminished visual acuity in the implant group, and the lack of a sustained impact of such diminution on the average visual acuity over time (Figure 2) in the two groups. Regarding potential complications of implant surgery, transient vitreous hemorrhage occurred more frequently in the implant group (16% vs. 5% by 24 months, HR=3.6, p=0.002), but the risks of ocular hypotony, retinal detachment and infectious endophthalmitis were low, without significant differences between groups.

Table 4.

Incidence of ocular complications of uveitis or its treatment for the two treatment groups,among eyes at risk at baseline.*

| Implant Therapy | Systemic Therapy | Hazard Ratio | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # Eyes at risk | Cumulative % with event by 2 years (95% CI) | # Eyes at risk | Cumulative % with event by 2 years (95% CI) | Implant/Systemic (95% CI) | ||

| Intraocular Pressure (IOP) events | ||||||

| IOP ≥ 30 mmHg | 234 | 32.8 (27.1, 39.2) | 229 | 6.3 (3.7, 10.3) | 6.08 (3.32, 11.15) | <.0001 |

| IOP ≥24 mmHg | 234 | 53.1 (46.9, 59.7) | 228 | 18.7 (14.2, 24.5) | 3.59 (2.34, 5.50) | <.0001 |

| IOP ≥ 10 mmHg increase from baseline | 235 | 51.8 (45.5, 58.3) | 230 | 15.5 (11.4, 20.9) | 4.28 (2.78, 6.58) | <.0001 |

| Glaucoma and IOP-lowering treatment | ||||||

| Glaucoma | 212 | 16.5 (12.1, 22.2) | 202 | 4.0 (2.0, 7.8) | 4.19 (1.82, 9.63) | 0.0008 |

| Use of any IOP-lowering therapy | 201 | 61.1 (54.3, 67.8) | 203 | 20.1 (15.1, 26.3) | 4.16 (2.67, 6.47) | <.0001 |

| IOP-lowering surgery | 233 | 26.2 (21.0, 32.4) | 226 | 3.7 (1.9, 7.2) | 8.40 (3.39, 20.82) | <.0001 |

| Cataract | ||||||

| Incident Cataract | 54 | 90.7 (81.3, 96.6) | 50 | 44.9 (32.3, 59.8) | 4.12 (2.21, 7.67) | <.0001 |

| Cataract Surgery | 140 | 80.4 (73.3, 86.6) | 125 | 31.3 (23.9, 40.4) | 3.33 (2.20, 5.04) | <.0001 |

| Visual acuity worse than 20/40 | ||||||

| First visit with a reduced acuity | 112 | 57.7 (48.2, 67.3) | 117 | 35.6 (26.4, 44.8) | 1.91 (1.26, 2.88) | 0.0021 |

| Reduced for two consecutive visits | 112 | 31.2 (22.3, 40.1) | 117 | 19.8 (12.2, 27.3) | 1.68 (0.97, 2.90) | 0.060 |

| Visual acuity 20/200 or wors | ||||||

| First visit with a reduced acuity | 196 | 13.0 (8.2, 17.8) | 193 | 9.9 (5.6, 14.1) | 1.31 (0.68, 2.49) | 0.41 |

| Potential complications of implant surgery | ||||||

| IOP < 6 mmHg (hypotony) | 228 | 8.4 (5.4, 12.8) | 218 | 6.1 (3.6, 10.2) | 1.46 (0.60, 3.54) | 0.41 |

| Vitreous hemorrhage | 236 | 15.7 (11.6, 21.0) | 230 | 4.9 (2.7, 8.6) | 3.57 (1.60, 7.96) | 0.0019 |

| Endophthalmitis | 237 | 1.3 (0.4, 4.0) | 230 | 0 | Not estimable | |

| Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment | 236 | 2.1 (0.9, 5.0) | 230 | 0.44 (0.1, 3.1) | 4.91 (0.57, 42.56) | 0.15 |

| Implant extrusion | 204 | 0 | 231 | 0 | Not estimable | |

Adverse systemic events were infrequent in both groups. In an analysis permitting multiple events per patient, the risk of a systemic infection requiring prescription therapy was lower in the implant than the systemic group (0.36 vs. 0.60 events/person-year, p=0.034), but the risk of hospitalization did not differ substantially (0.13 vs. 0.17 hospitalizations/person-year respectively, p=0.35). Inspection of adverse event reports suggested that the infections in question did not result in long-term unfavorable outcomes. In the 24-month analyses (Table 5), the rate of measured hypertension (systolic>140 mmHg or diastolic>90 mmHg at any visit) was lower in the implant group (13% vs. 27%, HR=0.44, p=0.030), but the rate of anti-hypertensive treatment initiation did not differ substantially (5% vs. 11%, HR=0.40, p=0.13). The incidence of other adverse systemic outcomes—including hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, osteoporosis, fractures, and blood count/chemistry abnormalities—was not statistically distinguishable between groups. Weight was stable over time in both groups (Table 6).

Table 5.

Incidence of systemic complications for the two treatment groups, among patients at risk at baseline.*

| Implant Therapy | Systemic Therapy | Hazard Ratio | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #Patients at risk | Cumulative % with event by 2 years (95% CI)‖ | #Patients at risk | Cumulative % with event by 2 years (95% CI)‖ | Impant/Systemic (95% CI)‖ | ||

| Potential complications of corticosteroid therapy‖ | ||||||

| Hyperlipidemia (LDL ≥160 mg/mL) | 97 | 9.8 (5.2, 18.0) | 104 | 11.0 (6.3, 19.1) | 0.91 (039, 2.15) | 0.84 |

| Hyperlipidemia diagnosis requiring treatment | 90 | 1.1(0.2, 7.7) | 86 | 6.0(2.5, 13.8) | 0.19(002, 1.65) | 0.13 |

| Hypertension | ||||||

| Measured SBP≥160 and/or DBP≥100 | 111 | 2.9(0.9, 8.6) | 109 | 10.3(5.8, 17.8) | 0.25 (007, 0.89) | 0.030 |

| Measured SBP≥140 and/or DBP≥90 | 81 | 12.9(7.2, 22.6) | 89 | 26.9(18.4, 37.1) | 0.44 (0.21, 0.92) | 0.030 |

| Hypertension diagnosis requiring treatment | 88 | 4.6(1.8, 11.9) | 88 | 10.5(5.6, 19.3) | 0.40(0.13, 1.29) | 0.13 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 105 | 1.0(0.1, 6.6) | 114 | 3.6(1.4, 9.4) | 0.26 (0.03, 2.44) | 0.24 |

| Bone | ||||||

| Osteopenia | 52 | 25.5(15.7, 39.9) | 63 | 13.0(6.7, 24.4) | 1.98(0.83, 4.70) | 0.12 |

| Osteoporosis | 107 | 4.8(2.0, 11.2) | 108 | 5.0(2.1, 11.6) | 0.95(0, 28, 3.25) | 0.93 |

| Fractures | 125 | 4.1(1.7, 9.5) | 124 | 8.4(4.6, 15.0) | 0.47(0.16, 1.35) | 0.16 |

| Potential complications of immunosuppressive therapy | ||||||

| White blood cell count ≤ 2500 cells/μL | 121 | 0.8(0.1, 5.8) | 120 | 2.6(0.8, 7.7) | 0.33(0.03, 3.15) | 0.34 |

| Platelet count ≤ 100,000/μL | 120 | 2.6(0.8, 7.8) | 118 | 1.7(0.4, 6.6) | 1.43(0.24, 8.35) | 0.69 |

| Hemoglobin ≤10 g/dL | 121 | 0.9(0.1, 6.0) | 118 | 1.8(0.4, 7.0) | 0.88(0.09, 9.00) | 0.92 |

| Elevated liver enzymes¶ | 120 | 5.2(2.4, 11.3) | 120 | 0.9(0.1, 6.0) | 6.45(0.88, 47.2) | 0.066 |

| Elevated creatinine† | 122 | 10.1(5.9, 17.1) | 120 | 5.2(2.4, 11.2) | 2.11(0.80, 5.60) | 0.13 |

| Cancer diagnosis | 126 | 0.8(0.1, 5.5) | 124 | 3.2(1.0, 10.1) | 0.34(0.04, 3.20) | 0.34 |

| Death | 126 | 1.6(0.4, 6.3) | 124 | 0 | Not estimable | |

Patients with prevalent complications or missing data at enrollment were excluded from the risk set; the table only assesses first events, not multiple events.

Hazard ratios are adjusted for bilateral disease and uveitis stratum.

LDL = low density lipoprotein; SBP = systolic blood pressure; DBP = diastolic blood pressure; % = percent; CI = confidence interval.

Eleveated liver enzyme is defined as twice the upper limit of normal for aspartate aminotransferase and/or alanine aminotransferase.

Elevated creatinine is defined as > 1.5 mg/dL and/or > 30% increase from baseline.

Table 6.

Change in Quality of Life (QoL) and weight over time for the implant and systemic treatment arms during the initial 2 years of follow-up (as-randomized analysis).

| Sample Size* | Estimated Mean ‖(SE §) | Estimated Mean Change from Enrollment(SE) | Estimated Treatment Effect † (95% CI§) | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Implant | Systemic | Implant | Systemic | Implant: Systemic | |||

| Vision-related QoL | |||||||

| VFQ-25 (Overall Composite Score) | N= | ||||||

| Enrollment | 255 | 60.6(2.4) | 64.9(2.5) | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| 6 months | 233 | 71.4(2.4) | 66.3(2.5) | 10.77(1.31) | 1.41(1.38) | 9.37 (5.64, 13.09) | <0.001 |

| 12 months | 235 | 72.7(2.5) | 69.7(2.5) | 12.13(1.60) | 4.86(13.8) | 7.27 (3.11, 11.42) | 0.001 |

| 24 months | 232 | 72.1(2.5) | 71.7(2.6) | 11.44(1.67) | 6.80(1.58) | 4.64(0.14, 9.15) | 0.043 |

| Generic health-related QoL | |||||||

| SF-36 (Mental Component Summary Score) | N= | ||||||

| Enrollment | 255 | 47.5(1.3) | 48.3(1.2) | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| 6 months | 236 | 51.1(1.12) | 45.5(1.4) | 3.58(1.12) | −2.75(1.14) | 6.33 (3.19, 9.47) | <0.001 |

| 12 months | 234 | 51.0(1.1) | 46.5(1.3) | 3.52(10.5) | −1.81(1.11) | 5.33 (2.33, 8.33) | 0.001 |

| 24 months | 232 | 50.0(L2) | 47.2(1.4) | 2.55(1.11) | −1.07(1.15) | 3.62(0.49, 6.76) | 0.023 |

| SF-36 (Physical Component Summary Score) | N= | ||||||

| Enrollment | 255 | 46.5(1.2) | 48.4(1.1} | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| 6 months | 236 | 46.4(1.2) | 46.6(1.1) | −0.07 (0.73) | −1.81 (0.67) | 1.73 (−0.21, 3.67) | 0.079 |

| 12 months | 234 | 47.5(1.2) | 46.6(1.1} | 1.02 (0.78) | −1.87 (0.87) | 2.89(0.60, 5.18) | 0.013 |

| 24 months | 232 | 47.6(1.2) | 46.6(1.1) | 1.15 (0.83) | −1.79 (0.90) | 2.95 (0.54, 5.36) | 0.016 |

| Health utility | |||||||

| EuroQol (Visual Analog Scale) | N= | ||||||

| Enrollment | 253 | 72.71.9) | 74.3(2.0) | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| 6 months | 233 | 75.0(2.1} | 72.5(2.0) | 2.34(1.61) | −1.85(1.90) | 4.19 (−0.69, 9.07) | 0.092 |

| 12 months | 234 | 77.31.9) | 71.3(2.2) | 4.66(1.36) | −3.00(1.78) | 7.65 (3.26, 12.05) | 0.001 |

| 24 months | 232 | 78.0(1.8) | 73.4(1.9) | 5.29(1.28) | −0.88(1.88) | 6.17 (1.87, 10.47) | 0.005 |

| EuroQol (EQ-5D HealthUtility Index) | N = | ||||||

| Enrollment | 254 | 0.81(0.02) | 0.83(0.02) | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| 6 months | 236 | 0.83(0.02) | 0.82(0.02) | 0.01(0.01) | −0.01(0.02) | 0.03(−0.02, 0.07) | 0.25 |

| 12 months | 235 | 0.83(0.02) | 0.80(0.02) | 0.02(0.02) | −0.03(0.02) | 0.05(0.00, 0.10) | 0.041 |

| 24 months | 232 | 0.84(0.02) | 0.81(0.02) | 0.02(0.02) | −0.02(0.02) | 0.04 (−0.01, 0.09) | 0.060 |

|

| |||||||

| Weight (kg) | N= | ||||||

| Enrollment | 255 | 87.8(26) | 86.0(27) | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| 6 months | 231 | 88.2(2.7) | 87.0(2.7) | 0.40(0.54) | 0.96(0.75) | −0.56 (−2.38, 1.26) | 0.54 |

| 12 months | 229 | 87.4(2.7) | 86.4(2.7) | −0.38(0.70) | 0.38 (0.81) | −0.76 (−2.87, 1.34) | 0.48 |

Serious adverse event reporting gave results similar to the prospectively ascertained ocular and systemic adverse outcomes.

Quality of Life

Changes from baseline to 24 months in generic health-related quality of life and health utility scores favored implant therapy (Table 6), but the magnitude of differences in improvement between groups was less than or equal to the threshold of previously reported minimally important differences.26–28 During the first six months, vision-related quality of life improved by 9.4 (out of 100) units more in the implant than the systemic group (p<0.0001). By 24 months both groups had improved, leaving a modest 4.6 unit advantage for the implant group (p=0.04), on the order of the reported minimally important difference (4–6 units).27 A sensitivity analysis evaluating the percentage of individuals with a minimally important improvement26–28 did not differ significantly for any of the quality of life metrics (results not shown).

Discussion

Over 24 months following randomization of patients with non-infectious intermediate, posterior and panuveitis to implant or systemic therapy, on average, both groups had substantial improvement in visual acuity to a degree that was not significantly different (other than a small visual acuity improvement advantage in the implant group at six months). On average, the implant group improved by 2.8 letters more (95% Confidence Interval: −1.2 to 6.7 letters, with positive numbers favoring implant). Visual field sensitivity remained stably reduced in both groups. Many eyes required cataract surgery and other interventions, especially in the implant group; visual results may have been different if such treatments had not been available.

Our results indicate that both approaches are successful in controlling inflammation in the majority of cases, but that the implant achieves inflammatory control both faster and more often. We expected more uveitis activity early on in the systemic group, during the period when the minimal suppressive prednisone dose had to be determined empirically by tapering corticosteroids to the point of relapse. However, on average, the implant group showed better control of inflammation throughout follow-up, not just early on. Superiority of implant therapy for controlling inflammation was consistent with two small series in which implant therapy succeeded in controlling inflammation that had not responded to systemic therapy11;29 and a smaller trial in which systemic therapy was maintained for six months and then withdrawn.13 Longer follow-up will be needed to determine if superiority in controlling inflammation will result in better longer-term visual outcomes, as is widely assumed, and has been confirmed for two forms of uveitis in which it has been analyzed.30;31

Quality of life outcomes suggested a clinically important advantage in vision-related quality of life for the implant group at six months, but narrowed to a small difference on the order of the minimally clinically important difference27 by 24 months, paralleling improvement in visual acuity and vitreous haze. The implant group also had statistically better general self-reported quality of life outcomes, but the extent of the differences were marginal with respect to previously reported minimal clinically relevant differences.26;28

Ocular complications of uveitis or treatment were more common in the implant group, which underwent many more cataract and glaucoma surgeries than the systemic group, consistent with results of the implant drug licensing trials.9;13;32 Nearly all phakic eyes receiving implant therapy can be expected to require cataract surgery, and about 25% of implant-treated eyes will require glaucoma surgery over 24 months. Despite IOP management, an important minority developed frank glaucomatous changes, mostly in the implant group, with visual field loss. Complications directly attributable to surgical implant placement were infrequent, consistent with others' experience; the absolute risk of endophthalmitis and of retinal detachment was low or zero in both groups.9;13;32

In contrast, systemic therapy (in which corticosteroid-sparing immunosuppressive therapy was used to minimize ongoing use of corticosteroids for the large majority of patients) was associated with relatively little additional systemic morbidity compared with implant therapy. Elevated blood pressure measurements during the trial were more frequent in the systemic group, but the proportion diagnosed with and treated for hypertension was small in both groups, and did not differ significantly. Infections requiring treatment were more common in the systemic group—a difference which may have resulted from immunosuppression or from bias in that clinicians might have been more likely to treat infections aggressively in patients on immunosuppressive therapy (or both). No other differences that were statistically significant or large in magnitude were observed, despite prospectively tracking potential complications of systemic corticosteroid therapy, including changes in body weight, incidence of diabetes, and changes in bone mineral density. These observations suggest that systemic therapy does not commonly induce morbidity when corticosteroid-sparing therapy is used aggressively to limit the duration of prednisone doses greater than 10 mg/day. Meta-analyses from other disease states also suggest that maintenance therapy with lower doses of prednisone is associated with relatively little morbidity.33;34 (Maintenance therapy with doses of prednisone exceeding 10 mg/day, not studied in this trial, clearly are associated with substantial morbidity8).

Strengths of the study included its randomized trial methodology to compare active treatments, and robust methods for ascertaining important clinical outcomes. The protocol was implemented successfully with acceptable adherence to treatment assignment and good follow-up. It is unlikely that the limited number of treatment crossovers obscured real differences in the primary outcome given the study power. Masking of participants and clinicians was not implemented because of ethical and feasibility constraints; the lack of masked ascertainment of self-reported quality of life and clinically evaluated uveitis activity potentially could have affected these outcomes.35

In addition to the primary visual acuity outcome, we provide results on several pre-specified secondary outcomes, to better evaluate the comparative effectiveness of the alternative treatment approaches. Because multiple comparisons increase the probability of a false positive result, caution is needed in interpreting these secondary results.36 In this study, the large differences observed in uveitis activity and the risk of local complications would be statistically significant even had we applied aggressive adjustment for multiple comparisons (e.g., Bonferroni correction). However, the differences observed in most quality of life comparisons were small enough to be susceptible to false positive results, which should be taken into account (along with the consistency of the quality of life results observed and their small effect sizes) in interpreting those results.

In summary, objective visual outcomes for intermediate, posterior and panuveitis improved over 24 months in both the implant and systemic treatment groups. Neither approach was determined to be superior, with a range of plausible differences between groups from a 1.2 letter advantage for systemic therapy to a 6.7 letter advantage for implant therapy. Both approaches usually succeeded in controlling ocular inflammation, but implant therapy gained control faster and more often, consistent with ongoing delivery of substantial dose corticosteroid therapy. At 24 months, implant therapy was associated with small improvements in vision-related and general quality of life compared with systemic therapy, and a higher risk of local adverse events (typically manageable with additional surgery). Implant therapy did not substantially reduce the risk of systemic adverse events, which were generally low in both groups.

Our results indicate that both treatments are associated with improvement over 24 months for the majority of cases, without clear evidence indicating substantially superior overall effectiveness of either approach. Therefore, the choice of treatment for a specific patient should be based on the importance of the advantages and disadvantages identified with the alternative treatments in that patient's particular clinical circumstances. Additional follow-up will be valuable to determine whether better control of uveitis with implant therapy over time eventually results in objective visual benefit; further exploration of the factors associated with vision loss and glaucoma development also will be initiated to better guide such decisions.

The systemic therapy approach we studied (using corticosteroid-sparing immunosuppressive drugs to avoid use of long-term, high-dose systemic corticosteroids) is widely used for systemic and local inflammatory diseases. Our results, in a population with a low risk of systemic adverse events on the basis of their disease, provide reassurance that this strategy for management of systemic and local inflammatory diseases is not associated with a high risk of systemic complications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This study is supported by National Eye Institute Cooperative Agreements U10EY014655 (Dr. Jabs), U10EY014660 (Dr. Holbrook), and U10EY014656 (Dr. Altaweel). Bausch & Lomb provided support to the study in the form of donation of fluocinolone implants for patients randomized to implant therapy who were uninsured or otherwise unable to pay for implants, or were located at a site where implants could not be purchased (e.g., in the United Kingdom). Additional support was provided by Research to Prevent Blindness and the Paul and Evanina Mackall Foundation. A representative of the National Eye Institute participated in the conduct of the study, including the study design and the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data, as well as in the review and approval of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Kempen is a consultant for Alcon Laboratories, Allergan Pharmaceutical Corporation, Lux Biosciences, Inc., and Sanofi Pasteur SA. Dr. Jabs is a consultant for Abbott Laboratories, Alcon Laboratories, Allergan Pharmaceutical Corporation, Corcept Therapeutics, GenenTech, Inc., Genzyme Corporation, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis Pharmaceutical Corp., Roche Pharmaceuticals, and Applied Genetic Technologies Corporation (AGTC). Dr. Louis is a consultant for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Medtronic, Inc., and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). Dr. Thorne is a consultant for Heron Evidence, Ltd. Drs. Altaweel, Holbrook, and Sugar have no conflicts of interest.

Off label use of drugs: adalimumab, azathioprine, cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide, daclizumab, infliximab, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, rituximab, tacrolimus.

Supplemental Material: This article contains online-only material. The following should appear online-only: Appendices 1–3, Table 1, Figure 3.

Reference List

- 1.ten Doesschate J. Causes of blindness in The Netherlands. Doc Ophthalmol. 1982;52:279–85. doi: 10.1007/BF01675857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Volume One: The 1983 Report of the National Advisory Eye Council. National Institutes of Health, Public Health Service, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Bethesda, MD: 1983. [Accessed June 24, 2011]. Vision Research-A National Plan: 1983–1987; p. 13. Available at: http://ia700402.us.archive.org/34/items/visionresearchna01nati/visionresearchna01n ati.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bloch-Michel E, Nussenblatt RB. International Uveitis Study Group recommendations for the evaluation of intraocular inflammatory disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 1987;103:234–5. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)74235-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group Standardization of uveitis nomenclature for reporting clinical data: results of the First International Workshop. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:509–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.03.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Durrani OM, Tehrani NN, Marr JE, et al. Degree, duration, and causes of visual loss in uveitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88:1159–62. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2003.037226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rothova A, Suttorp-van Schulten MS, Frits Treffers W, Kijlstra A. Causes and frequency of blindness in patients with intraocular inflammatory disease. Br J Ophthalmol. 1996;80:332–6. doi: 10.1136/bjo.80.4.332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Durrani OM, Meads CA, Murray PI. Uveitis: a potentially blinding disease. Ophthalmologica. 2004;218:223–36. doi: 10.1159/000078612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jabs DA, Rosenbaum JT, Foster CS, et al. Guidelines for the use of immunosuppressive drugs in patients with ocular inflammatory disorders: recommendations of an expert panel. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;130:492–513. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00659-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Callanan DG, Jaffe GJ, Martin DF, et al. Treatment of posterior uveitis with a fluocinolone acetonide implant: three-year clinical trial results. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:1191–201. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.9.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jaffe GJ, Martin D, Callanan D, et al. Fluocinolone Acetonide Uveitis Study Group Fluocinolone acetonide implant (Retisert) for noninfectious posterior uveitis: thirty-four-week results of a multicenter randomized clinical study. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1020–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaffe GJ, Ben Nun J, Guo H, et al. Fluocinolone acetonide sustained drug delivery device to treat severe uveitis. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:2024–33. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00466-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Multicenter Uveitis Steroid Treatment Trial Research Group The Multicenter Uveitis Steroid Treatment Trial: rationale, design, and baseline characteristics. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;149:550–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pavesio C, Zierhut M, Bairi K, et al. Fluocinolone Acetonide Study Group Evaluation of an intravitreal fluocinolone acetonide implant versus standard systemic therapy in noninfectious posterior uveitis. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:567–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferris FL, III, Bailey I. Standardizing the measurement of visual acuity for clinical research studies: guidelines from the Eye Care Technology Forum. Ophthalmology. 1996;103:181–2. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(96)30742-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bengtsson B, Heijl A. Comparing significance and magnitude of glaucomatous visual field defects using the SITA and Full Threshold strategies. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 1999;77:143–6. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.1999.770205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mangione CM, Lee PP, Gutierrez PR, et al. National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire Field Test Investigators Development of the 25-item National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1050–8. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.7.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brazier JE, Harper R, Jones NM, et al. Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire: new outcome measure for primary care. BMJ. 1992;305:160–4. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jenkinson C, Wright L, Coulter A. Criterion validity and reliability of the SF-36 in a population sample. Qual Life Res. 1994;3:7–12. doi: 10.1007/BF00647843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.EuroQol Group EuroQol--a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199–208. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gragoudas ES, Adamis AP, Cunningham ET, Jr, et al. VEGF Inhibition Study in Ocular Neovascularization Clinical Trial Group Pegaptanib for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2805–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verteporfin in Photodynamic Therapy (VIP) Study Group Photodynamic therapy of subfoveal choroidal neovascularization in pathologic myopia with verteporfin: 1-year results of a randomized clinical trial--VIP report no. 1. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:841–52. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(01)00544-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ellenberg SS, Fleming TR, DeMets DL. Data Monitoring Committees in Clinical Trials: A Practical Perspective. Wiley; Chichester, UK: 2002. pp. 126–128. [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Brien PC, Fleming TR. A multiple testing procedure for clinical trials. Biometrics. 1979;35:549–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42:121–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Little RJ, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. 2nd ed. Wiley; Hoboken, NJ: 2002. pp. 85–89. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hays RD, Morales LS. The RAND-36 measure of health-related quality of life. Ann Med. 2001;33:350–7. doi: 10.3109/07853890109002089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suner IJ, Kokame GT, Yu E, et al. Responsiveness of NEI VFQ-25 to changes in visual acuity in neovascular AMD: validation studies from two phase 3 clinical trials. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:3629–35. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-3225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pickard AS, Neary MP, Cella D. Health Qual Life Outcomes [serial online] Vol. 5. 2007. [Accessed June 24, 2011]. Estimation of minimally important differences in EQ-5D utility and VAS scores in cancer; p. 70. Available at: http://www.hqlo.com/content/5/1/70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jaffe GJ, McCallum RM, Branchaud B, et al. Long-term follow-up results of a pilot trial of a fluocinolone acetonide implant to treat posterior uveitis. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:1192–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kacmaz RO, Kempen JH, Newcomb C, et al. Systemic Immunosuppressive Therapy for Eye Diseases Cohort Study Group Ocular inflammation in Behçet disease: incidence of ocular complications and of loss of visual acuity. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146:828–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thorne JE, Woreta F, Kedhar SR, et al. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis: incidence of ocular complications and visual acuity loss. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143:840–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldstein DA, Godfrey DG, Hall A, et al. Intraocular pressure in patients with uveitis treated with fluocinolone acetonide implants. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125:1478–85. doi: 10.1001/archopht.125.11.ecs70063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Da Silva JA, Jacobs JW, Kirwan JR, et al. Safety of low dose glucocorticoid treatment in rheumatoid arthritis: published evidence and prospective trial data. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:285–93. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.038638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ravindran V, Rachapalli S, Choy EH. Safety of medium- to long-term glucocorticoid therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48:807–11. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wise RA, Bartlett SJ, Brown ED, et al. American Lung Association Asthma Clinical Research Centers Randomized trial of the effect of drug presentation on asthma outcomes: the American Lung Association Asthma Clinical Research Centers. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:436–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.05.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang R, Lagakos SW, Ware JH, et al. Statistics in medicine--reporting of subgroup analyses in clinical trials. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2189–94. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr077003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.