Abstract

Objective: To determine the long term relative survival of all patients who had surgery for abdominal aortic aneurysm in Western Australia during 1985-94.

Design: Population based study.

Setting: Western Australia.

Subjects: All patients who had had surgery for abdominal aortic aneurysm in Western Australia during 1985-94.

Main outcome measures: Morbidity and mortality data of patients admitted and surgically treated for abdominal aortic aneurysm in Western Australia during 1985-94. Elective, ruptured, and acute non-ruptured cases were analysed separately. Independent analyses for sex and patients aged 80 years or more were also undertaken. Postoperative (>30 days) relative survival was assessed against age and sex matched controls.

Results: Overall, 1475 (1257 men, 218 women) cases were identified. The crude five year survival after elective surgery, including deaths within 30 days of surgery, was 79% for both men and women. When compared with a matched population the five year relative survival after elective surgery was 94.9% (95% confidence interval 89.9% to 99.9%) for men but only 88.0% (76.3% to 99.7%) for women. The five year relative survival of those aged 80 years and over was good: 116.6% (89.1% to 144.0%) compared with 92.4% (87.7% to 97.0%) for those under 80 years of age (men and women combined). Cardiovascular disease caused 57.8% of the 341 deaths after 30 days.

Conclusion: In a condition such as abdominal aortic aneurysm, which occurs in elderly patients, relative survival is more clinically meaningful than crude survival. The five year relative survival in cases of elective and ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm was better in men than in women. This is probably because of greater comorbidity in women with abdominal aortic aneurysm and this deserves more attention in the future. The long term survival outcome in octogenarians supports surgery in selected cases.

Key messages

Background mortality for conditions such as abdominal aortic aneurysm in elderly patients needs to be taken into account when assessing long term survival after surgery

Relative survival methodology can correct for background mortality

The five year relative survival for patients surviving beyond 30 days of elective surgery for abdominal aortic aneurysm was 95% for men and 88% for women

For octogenarians, five year survival after elective surgery was greater than that expected of an age matched population

Age over 80 years should not preclude consideration for elective surgery for abdominal aortic aneurysm

Introduction

Surgeons place much emphasis on the 30 day case fatality rates after surgery for abdominal aortic aneurysm, and there is much literature on the topic.1–3 Long term survival, particularly in a condition that affects elderly patients with significant comorbidity, is equally important yet infrequently reported. Data on long term survival are especially important if population screening and endoluminal grafting of abdominal aortic aneurysms are introduced, as the diagnostic rate and intervention rate for abdominal aortic aneurysm may increase.

At least 20 publications in English report a diverse range of five year survival rates after surgery for abdominal aortic aneurysm. As with case fatality rates the results depend on several factors including source of data (institutional versus population based), period studied (1970s versus 1990s), patient characteristics such as age, sex, and admission status (elective, ruptured, acute non-ruptured), and methods of analysis. Clinicians caring for patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm are usually familiar with the immediate case fatality rate after surgery for the condition, but are unlikely to be confident about quoting the expected five year survival to their patients. This information may influence the referral practices of physicians and general practitioners.

We aimed to establish the five year relative survival in all patients who were surgically treated for abdominal aortic aneurysm in Western Australia during 1985-94. Western Australia is an ideal location for the study of long term outcomes after surgery because it has a database of linked hospital and vital records that provides complete information on its population, it has a geographically isolated population, and tertiary health services are centralised. Our study is one of the largest population based studies of surgery for abdominal aortic aneurysm and shows the influence of admission status, age, and sex on relative survival after surgery for abdominal aortic aneurysm.

Subjects and methods

Selection of patients

The Western Australia linked database consists of hospital morbidity data, birth and death records, mental health services’ data, cancer registrations, and midwives’ notifications for the population of Western Australia from 1980.4 In our study the database was used to link hospital records for all patients who had had surgery for abdominal aortic aneurysm during 1985-94. All morbidity records with a patient admission date before 1988 were selected using the combined ICD-9 (international classification of diseases, 9th revision) diagnosis codes (441.30 or 441.40) and ICPM (international classification of procedures in medicine) procedure code (58.53).5,6 Patients admitted during 1988-94 were selected using the combined ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes (441.30 or 441.40) and ICD-9-CM procedure code (38.44).7,8 The anonymised data file for our study was obtained from the Western Australia database and was current on 20 November 1996.

Our study population was divided into three groups based on admission status and procedure code: patients admitted for elective surgery, those undergoing surgery for ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm, and those admitted to hospital as an emergency without mention of rupture, but who underwent surgery for abdominal aortic aneurysm (acute non-ruptured). Validation of 10% of records failed to identify any errors in this method of classification. The acute non-ruptured group was studied separately as there is evidence that the mortality rate in this group differs from that in elective cases.9–12 Surgery for abdominal aortic aneurysm (without evidence of rupture) was the primary procedure in 94% (241/257) of cases within this group; the remaining 16 (6%) cases included additional procedures described elsewhere.9 Patients were restricted to those aged 55 years and over because cases of abdominal aortic aneurysm under this age were rare (n=30, 2% of total) and may have been atypical.13

Relative survival

The concept of relative survival was described in the 1960s14 and its application to survival of cancer patients developed in the 1980s.15,16 Relative survival is the ratio of the survival observed in patients to the survival of a population similar to the patient group regarding calendar period, geographical location, age, and sex. Although relative survival is a ratio of two proportions, not a rate, rate is often used in this context.

In those patients who survived the repair procedure for more than 30 days, long term relative survival was estimated with the use of a computer program developed by the Mayo Clinic17 using the Hakulinen method.15,18 The program was modified to include yearly life table data for the Western Australian population in 1980-96, as supplied by the Australian Bureau of Statistics, and estimates the expected survival based on population hazard rates. Differences between the survival estimates of the observed cases and the expected population were determined by a one sample log rank test.17 The influence of patient admission status (elective, ruptured, and acute non-ruptured), sex, and age on the outcomes was examined separately.

The index admission for each patient was defined as the hospital episode in which the repair procedure was first carried out. The exact date of the procedure was not available from the morbidity discharge records. Therefore, survival time was calculated from the date of admission for patients admitted for rupture. For those admitted as an elective or acute non-ruptured case, survival time was calculated from a date two days after the date of admission because standard practice in some hospitals involved admission two days before surgery. Case fatality was calculated from the number of deaths occurring within 30 days from the estimated date of surgery. Survival time in patients who remained alive during the study period was censored at 31 December 1995.

Results

Table 1 summarises the case fatality at 30 days and five years in men and women. The expected five year survival in Western Australia for men and women respectively was 93.6% and 96.4% at 60 years, 79.5% and 90.2% at 70 years, and 59.7% and 73.9% at 80 years.

Table 1.

Deaths from abdominal aortic aneurysm at 30 days and 5 years in men and women by admission status in Western Australia, 1985-94. Values are numbers (percentages)

| Admission status | Men (n=1257)

|

Women (n=218)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No operated on | 30 days | 5 years | No operated on | 30 days | 5 years | ||

| Ruptured* | 242 | 84 (34.7) | 117 (48.3) | 41 | 18 (43.9) | 29 (70.7) | |

| Elective | 796 | 35 (4.4) | 167 (21.0) | 139 | 5 (3.6) | 28 (20.1) | |

| Acute non-ruptured | 219 | 16 (7.3) | 75 (34.2) | 38 | 7 (18.4) | 14 (36.8) | |

283 cases undergoing surgery for rupture represent only 32.4% of all ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms (n=873) during study period; remainder died before admission (n=379) or after admission but without surgery (n=211).9

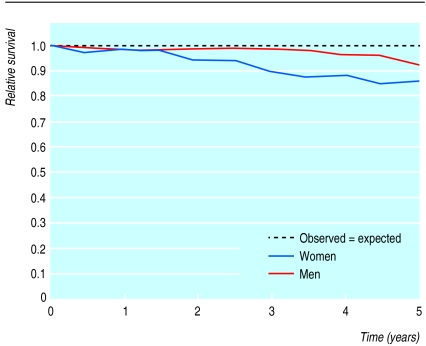

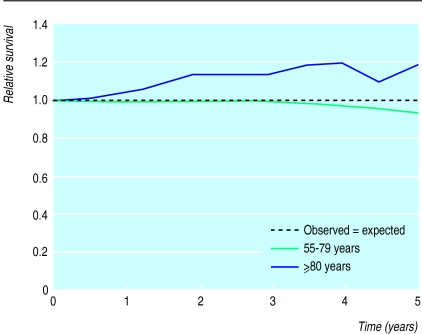

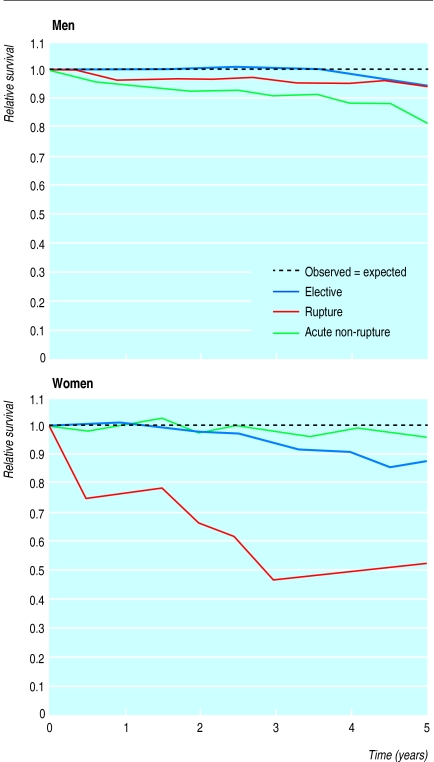

Figures 1 to 3 give the results of the relative survival analysis; deaths occurring within 30 days of surgery are excluded. Figure 1 combines elective and emergency cases and shows the poor relative survival of women compared with men. After elective surgery the survival of women but not men was significantly worse (P=0.003 versus P=0.149, log rank test) than that of the expected group (fig 2). The survival curve for patients less than 80 years of age was significantly less (P<0.001) than the expected group, but the curve for the octogenarians rose (fig 3) as their survival was better than that expected in the matched population (P=0.048).

Figure 1.

Relative survival of men and women, excluding 30 day mortality, who had surgery for abdominal aortic aneurysm in Western Australia during 1985-94

| 1 year | 5 years | |

| Men: | ||

| No at risk | 1059 | 352 |

| Relative survival (%) (95% CI) | 98.5 (97.1 to 99.9) | 92.3 (88.2 to 96.5) |

| Women: | ||

| No at risk | 179 | 61 |

| Relative survival (%) (95% CI) | 98.4 (95.3 to 101.6) | 85.8 (76.2 to 95.5) |

Figure 3.

Relative survival of all patients aged less than 80 years (693 men, 117 women) or 80 years and over (68 men, 17 women) who had elective surgery for abdominal aortic aneurysm in Western Australia during 1985-94

| 1 year | 5 years | |

| 55-79 years: | ||

| No at risk | 781 | 239 |

| Relative survival (%) (95% CI) | 99.6 (98.2 to 100.1) | 92.4 (87.7 to 97.0) |

| ⩾80 years: | ||

| No at risk | 79 | 11 |

| Relative survival (%) (95% CI) | 103.7 (97.6 to 109.8) | 116.6 (89.1 to 144.0) |

Figure 2.

Relative survival of men and women, excluding 30 day mortality, admitted for elective, rupture, and non-rupture surgery for abdominal aortic aneurysm in Western Australia during 1985-94

| Men | Women | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 year | 5 years | 1 year | 5 years | ||

| Ruptured: | |||||

| No at risk | 146 | 54 | 17 | 5 | |

| Relative survival (%) (95% CI) | 96.9 (92.6 to 101.2) | 95.0 (84.1 to 105.8) | 77.0 (58.3 to 95.6) | 52.3 (22.5 to 82.1) | |

| Acute non-ruptured: | |||||

| No at risk | 185 | 84 | 30 | 20 | |

| Relative survival (%) (95% CI) | 95.2 (91.1 to 99.3) | 82.3 (72.8 to 91.8) | 100.7 (94.2 to 104.0) | 96.0 (76.4 to 115.5) | |

| Elective: | |||||

| No at risk | 728 | 214 | 132 | 36 | |

| Relative survival (%) (95% CI) | 99.7 (98.1 to 101.2) | 94.9 (89.8 to 99.9) | 101.6 (99.5 to 103.1) | 88.0 (76.3 to 99.7) | |

The primary cause of death for all cases (n=341) dying more than 30 days after surgery for abdominal aortic aneurysm was: ischaemic heart disease (n=124, 36.4%), stroke (n=22, 6.5%), other cardiovascular disease (n=51, 15.0%), malignant disease (n=87, 25.5%), respiratory disease (n=29, 8.5%), and other causes (n=28, 8.1%).

Discussion

Over the past 15 years published reports on the five year survival after surgery for abdominal aortic aneurysm have included at least four multicentre,3,10,19,20 three population based,21–23 and several institutional studies.1,2,24–28 Based on these reports, the range of crude five year survival after elective surgery would seem to be about 60-80%. Although most reports include an expected survival in a matched population, they do not provide enough detail for relative survival to be calculated accurately. In abdominal aortic aneurysm, which usually occurs in elderly patients with substantial comorbidity, relative survival as well as crude survival is clinically meaningful. Furthermore, institutional data are subject to bias,12 which may be minimised by the use of a community based study design. Our study addresses these problems by providing relative survival analysis of population based data.

Sometimes the quality of administrative data is questioned, but from our experience the Western Australia core datasets are of a high standard. In the case of the hospital morbidity data system, 21 different quality checks are built into the provision of data from hospitals, and there are periodic audits of random selections of hospital assigned codes. By September 1996, the proportions of invalid links (false positives) and missed links (false negatives) were both estimated at 0.11%.

Although a perceived limitation of the Western Australia linked database may be that it does not detect deaths outside Western Australia, the mortality data are more than 99% complete. Estimations of census data supplied by the Australian Bureau of Statistics show that only 1.7% of the population over 18 years of age leave Western Australia permanently each year. Allowing for deaths and greater residential stability in an older age group with a significant medical history, it is estimated that less than 1% of the patients in this study were lost to follow up due to migration. The number of deaths occurring outside Western Australia is therefore very small and unlikely to influence the observed five year survival. Apart from the reliability of a database, various methodological factors (such as the inclusion or exclusion of deaths within 30 days of surgery and whether the acute non-ruptured cases were combined with elective cases) can also influence the results and make comparisons between studies difficult.

Five year relative survival was estimated for those patients who survived beyond 30 days of the initial procedure (figs 1–3). As the crude case fatality within 30 days may be substantial, particularly in ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm, this has been provided in Table 1. Figure 1 highlights the poor outcome in women compared with men. Although combining all cases provides a useful overview, the clinical differences between elective, ruptured, and acute non-ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm are such that their survival needs to be examined separately (fig 2).

Elective surgery—

In terms of clinical management it is information about five year survival after elective surgery that is most useful, particularly for clinicians considering referral of a patient for surgery. It is likely that for most men the chance of surviving five years after surgery equal to 95% of that expected for their age would be acceptable. They and their doctors would be more concerned about the 4% mortality within 30 days of surgery (table 1). These data support a policy of elective surgery given the cumulative risk of rupture of an abdominal aortic aneurysm (>5 cm in diameter), and the case fatality from rupture is 80%.9,29 Although we do not address quality of life there is evidence that patients undergoing elective surgery for repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm retain good quality of life.30 The results in women are more difficult to interpret because of small numbers. Their relative survival after elective surgery seems to be worse than in men (fig 2). A recent population based study found that women were less likely than men to survive to discharge after both elective and emergency surgery for abdominal aortic aneurysm.31 Evidence from screening studies suggests that women with abdominal aortic aneurysm are more likely to have been smokers than men with the condition.32 This may contribute to greater cardiovascular comorbidity and consequently poorer five year survival and needs to be considered in the follow up of women with abdominal aortic aneurysm.

Emergency cases

—Acute non-ruptured cases present several problems in the analysis of outcome after surgery. Although cases in our group were heterogeneous, we believed they were sufficiently distinct from both elective and ruptured cases to be analysed separately.9 In men the crude 30 day and five year case fatality seems to lie between the elective and ruptured cases (table 1). This has been previously reported.1,10,27 The relative survival at five years for men in the acute non-ruptured group was only 82.3%, presumably reflecting other disease that may have resulted in admission.

Any survival after rupture of an abdominal aortic aneurysm is a bonus although quality of life may be variable. The five year relative survival of 95% in men after rupture is tempered by the observation that 80% die before admission to hospital or within 30 days of surgery9; that is, this is a highly selected group with only the fittest patients surviving beyond 30 days. As with the elective cases the outcome in women was worse than in men especially after rupture. The high 30 day case fatality in acute non-ruptured cases in women may explain the good five year relative survival.

Influence of age—

We examined the relative survival after elective surgery for abdominal aortic aneurysm in octogenarians because of several reports advocating surgery in this age group.26,28 Surgery for abdominal aortic aneurysm in octogenarians is often reluctantly undertaken because even if they survive the operation, long term survival would not justify such major surgery in an elderly person. The relative survival of octogenarians undergoing elective surgery (n=85) was better than those aged less than 80 years (fig 3). Clearly all these cases were highly selected, but these data indicate that reasonable longevity (albeit of unknown quality) can be expected after elective surgery for abdominal aortic aneurysm in selected patients aged 80 or more years.

The management of abdominal aortic aneurysm seems to produce better short and long term results in men compared with women. Because of increasing awareness of abdominal aortic aneurysm in otherwise healthy men the rate of detection and treatment within this group has increased over the past decade.9 This may not be occurring to the same extent in women, and it is possible that the rate of detection has tended to be greatest for women with other medical conditions and comorbidity—that is, case selection has contributed to the poor long term outcome in women. If the current randomised controlled trials of screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm in elderly men show screening to be beneficial, the outlook for men with the condition should remain satisfactory. The situation for women is not so favourable: they are not being assessed in screening trials because of the low prevalence of abdominal aortic aneurysm, they may be less likely to undergo elective surgery than men,31 and they do worse than men after surgery for abdominal aortic aneurysm. Our study suggests that the clinical management of abdominal aortic aneurysm in women needs more attention.

Acknowledgments

We thank the extramural unit of the Western Australia data linkage project for their expertise, and Ms Jilda Hyndman of the state health department for advice on the hospital morbidity database.

Footnotes

Funding: National Health and Medical Research Council.

Conflict of interest: None.

References

- 1.Olsen PS, Schroeder T, Agerskov K, Roder O, Sorensen S, Perko M, et al. Surgery for abdominal aortic aneurysms: a survey of 656 patients. J Cardiovasc Surg. 1991;32:636–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stonebridge PA, Callam MJ, Bradbury AW, Murie JA, Jenkins AM, Ruckley CV. Comparison of long-term survival after successful repair of ruptured and non-ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. Br J Surg. 1993;80:585–586. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800800511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnston KW the Canadian Society for Vascular Surgery Aneurysm Study Group. Nonruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm: six-year follow-up results from the multicentre prospective Canadian aneurysm study. J Vasc Surg. 1994;20:163–170. doi: 10.1016/0741-5214(94)90002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Semmens JB, Lawrence-Brown MMD, Fletcher DR, Rouse IR, Holman CDJ. The quality of surgical care project: a model to evaluate surgical outcomes in Western Australia using population-based record linkage. Aust NZ J Surg. 1998;68:397–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1998.tb04786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.International Classification of Diseases. Manual of the international statistical classification of diseases, injuries, and causes of death. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 6.International Classification of Procedures in Medicine. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Official National Coding Centre Australian version of ICD-9-CM. Tabular list of diseases, 1st ed. Sydney: National Coding Centre, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Sydney; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Official NCC Australian Version of ICD-9-CM. Tabular list (annotated) and index of procedures, 1st ed. Sydney: National Coding Centre, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Sydney; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Semmens JB, Norman PE, Lawrence-Brown MMD, Bass AJ, Holman CDJ. A population-based record linkage study: the incidence of abdominal aortic aneurysms in Western Australia for 1985-94. Br J Surg. 1998;85:648–652. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soreide O, Lillestol J, Christensen O, Grimsgaard C, Myhre HO, Solheim K, et al. Abdominal aortic aneurysms: survival analysis of four hundred and thirty-four patients. Surgery. 1982;91:188–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas PRS, Stewart RD. Abdominal aortic aneurysm. Br J Surg. 1988;75:733–736. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800750804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campbell W. Mortality statistics for elective aortic aneurysms. Eur J Vasc Surg. 1991;5:111–113. doi: 10.1016/s0950-821x(05)80673-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muluk SC, Gertler JP, Brewster DC, Cambria RP, LaMuraglia GM, Moncure AC, et al. Presentation and patterns of aortic aneurysms in young patients. J Vasc Surg. 1994;20:880–888. doi: 10.1016/0741-5214(94)90224-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ederer F, Axtell LM, Cutler SJ. The relative survival rate: a statistical methodology. Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1961;6:101–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hakulinen T. Cancer survival corrected for heterogeneity in patient withdrawal. Biometrics. 1982;38:933–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Esteve J, Benhamou E, Croasdale M, Raymond L. Relative survival and the estimation of net survival: elements for further discussion. Stats Med. 1990;9:529–538. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780090506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Therneau T, Sicks J, Bergstralh E, Offord J. Expected survival based on hazard rates. Rochester, Minnesota: Mayo Clinic; 1994. Technical report number 52. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hakulinen T, Tenkanen L, Abeywickrama KH, Paivarinta L. Testing equality of relative survival patterns based on aggregated data. Biometrics. 1987;43:313–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feinglass J, Cowper D, Dunlop D, Slavensky R, Martin GJ, Pearce WH. Late survival risk factors for abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: experience from fourteen department of veterans affairs hospitals. Surgery. 1995;118:16–24. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(05)80004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koskas F, Kieffer E. Long-term survival after elective repair of infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm: results of a prospective multicentric study. Ann Vasc Surg. 1997;11:473–481. doi: 10.1007/s100169900078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roger VL, Ballard DJ, Hallet JW, Osmundson PJ, Puetz PA, Gersh BJ. Influence of coronary artery disease on morbidity and mortality after abdominal aortic aneurysmectomy: a population-based study, 1971-1987. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1989;14:1245–1252. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(89)90423-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bowers D, Cave WS. Aneurysms of the abdominal aorta: a 20-year study. J Roy Soc Med. 1985;78:812–820. doi: 10.1177/014107688507801005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hallet JW, Naessens JM, Ballard DJ. Early and late outcome of surgical repair for small abdominal aortic aneuyrsms: a population-based analysis. J Vasc Surg. 1993;18:684–691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reigel MM, Hollier LH, Kazmier FJ, O’Brien PC, Pairolero PC, Cherry Jr KJ, et al. Late survival in abdominal aortic aneurysm patients: the role of the selective myocardial revascularization on the basis of clinical symptoms. J Vasc Surg. 1987;5:222–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bernstein EF, Dilley RB, Randolph HFI. The improving outlook for patients over 70 years of age with abdominal aortic aneurysms. Ann Surg. 1988;207:318–322. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198803000-00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paty PSK, Lloyd WE, Chang BB, Darling RC, Leather RP, Shah DM. Aortic replacement for abdominal aortic aneurysm in elderly patients. Am J Surg. 1993;166:191–193. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)81054-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aune S, Amundsen SR, Evjensvold J, Trippestad A. Operative mortality and long-term relative survival of patients operated on for asymptomatic abdominal aortic aneurysm. Eur J Endovasc Surg. 1995;9:293–298. doi: 10.1016/s1078-5884(05)80133-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Hara PJ, Hertzer NR, Krajewski LP. Ten year experience with abdominal aortic aneurysm repair in octogenarians: early results and late outcome. J Vasc Surg. 1995;21:830–838. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(05)80015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Limet R, Sakalihassan N, Albert A. Determination of the expansion rate and incidence of rupture of abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 1991;14:540–548. doi: 10.1067/mva.1991.30047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Magee TR, Scott DJ, Dunkley A, St Johnston J, Campbell WP, Baird RN, et al. Quality of life following surgery for abdominal aortic aneurysm. Br J Surg. 1992;79:1014–1016. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800791009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Katz DJ, Stanley JC, Zelenock MD. Gender differences in abdominal aortic aneurysm prevalence, treatment, and outcome. J Vasc Surg. 1997;25:561–568. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(97)70268-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pleumeekers H, Hoes A, Van Der Does E, van Urk H, Hofman A, de Jong PTVM, et al. Aneurysms of the abdominal aorta in older adults. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142:1291–1299. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]