Abstract

Objective To investigate the risk of early childhood cancers associated with the mother’s exposure to radiofrequency from and proximity to macrocell mobile phone base stations (masts) during pregnancy.

Design Case-control study.

Setting Cancer registry and national birth register data in Great Britain.

Participants 1397 cases of cancer in children aged 0-4 from national cancer registry 1999-2001 and 5588 birth controls from national birth register, individually matched by sex and date of birth (four controls per case).

Main outcome measures Incidence of cancers of the brain and central nervous system, leukaemia, and non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas, and all cancers combined, adjusted for small area measures of education level, socioeconomic deprivation, population density, and population mixing.

Results Mean distance of registered address at birth from a macrocell base station, based on a national database of 76 890 base station antennas in 1996-2001, was similar for cases and controls (1107 (SD 1131) m v 1073 (SD 1130) m, P=0.31), as was total power output of base stations within 700 m of the address (2.89 (SD 5.9) kW v 3.00 (SD 6.0) kW, P=0.54) and modelled power density (−30.3 (SD 21.7) dBm v −29.7 (SD 21.5) dBm, P=0.41). For modelled power density at the address at birth, compared with the lowest exposure category the adjusted odds ratios were 1.01 (95% confidence interval 0.87 to 1.18) in the intermediate and 1.02 (0.88 to 1.20) in the highest exposure category for all cancers (P=0.79 for trend), 0.97 (0.69 to 1.37) and 0.76 (0.51 to 1.12), respectively, for brain and central nervous system cancers (P=0.33 for trend), and 1.16 (0.90 to 1.48) and 1.03 (0.79 to 1.34) for leukaemia and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (P=0.51 for trend).

Conclusions There is no association between risk of early childhood cancers and estimates of the mother’s exposure to mobile phone base stations during pregnancy.

Introduction

Use of mobile (cellular) phones has increased markedly in recent years. In the United Kingdom, the number of mobile connections has risen from just under nine million in 1997 to almost 74 million in 2007, and there are over four billion connections worldwide. Alongside the well recognised benefits of mobile phones,1 questions have been raised about possible health effects, including incidence of brain and other cancers, especially after prolonged use.1 2 3 In addition there have been suggestions of an increased risk of neurological conditions such as migraine and vertigo.4 There have also been concerns about possible developmental and other health effects associated with exposures to mobile phone base stations (masts),5 6 and surveys of the general public indicate high levels of concern about the potential risks of living near mobile phone base stations.7 8 The few reports of apparent cancer clusters near a mobile phone base station9 10 11 are difficult to interpret because of small numbers and possible selection and reporting biases.12 13 Also, there is no known radiobiological explanation,14 though low level exposures from base stations are widespread 15 and more or less continuous, and it is possible that cumulative exposures are important.16

Particular concerns have been raised about exposures of young children to mobile telephony, as the developing brain and other tissues might be more susceptible than in adults to potential effects of low level exposures to radiofrequency electromagnetic fields.17 We carried out a case-control study of early childhood cancers and estimated maternal exposures to radiofrequency during pregnancy from macrocell base stations in Great Britain.

Methods

Selection of cases and controls

We obtained data on all registered cases of cancer in children aged 0-4 in Great Britain in 1999-2001. We included brain and central nervous system (ICD (international classification of disease, tenth revision) codes C71-C72), leukaemia and non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas (C91-95, C82-85), and all cancers combined (C00-C96). From a total of 1926 cases, we obtained coordinates for the registered address at birth for 1792 (93%) using ADDRESS-POINT (1 m accuracy)18 and for 38 (2%) from the postcode centroid, which typically represents about 12 homes. We excluded 96 cases (5%) with no valid birth address or postcode. For 433 cases (22%), exposure data (based on birth address) were unavailable for the pregnancy period, leaving 1397 (73%) for study. We obtained four controls per case (5588 (90%) with complete addresses from 6222 randomly selected) from the national register of all births in Great Britain, individually matched to the cases by sex and date of birth.

Data on mobile phone base stations

The four national mobile phone operators (Vodafone, O2, Orange, and T-Mobile) provided data on all 81 781 antennas (Global System for Mobile communications 900 and 1800) for the period 1 January 1996 to 31 December 2001. The data included site identifier, coordinates (to an accuracy of about 10 m), start and decommission dates (month, year), number of antennas per base station, antenna orientation (azimuth), type (sectoral, omni-directional), height above ground level, total (electrical and mechanical) tilt, lateral and vertical beam width (degrees), total power output (effective isotropic radiated power), and frequency (MHz). As start and decommission dates were unavailable for one operator, we assumed those base stations were operational throughout the study period. For one operator, macrocells and microcells were not separately delimited; 4891 (6%) antennas were identified as microcells (by use of discriminant analysis based on height, equivalently isotropic radiated power, frequency, and percentage of urban land within 500 m of the antenna site) and were excluded. For the remaining 76 890 antennas, 66 790 (87%) had complete data, 5081 (7%) had missing data on tilt, beam widths, or frequency (replaced by company specific medians), and 5019 (7%) had missing data on height or effective isotropic radiated power, which we imputed from a regression model calibrated using antennas with complete data.

Exposure assessment

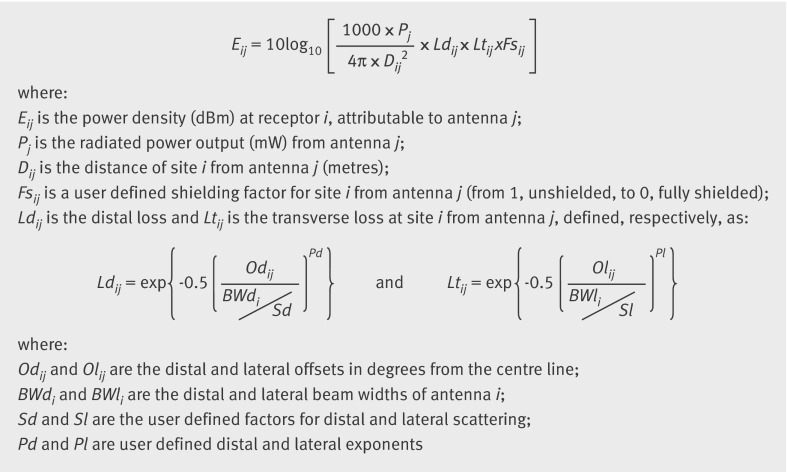

We estimated three exposure metrics for the birth address of each case and control. First was the distance (m) from the nearest mobile phone base station. Second was the total power output (kW) from summation across all base stations within 700 m (because power density at ground level typically peaks at a distance of 200-500 m from the base station, and then falls off rapidly with distance19 20). Finally, we computed modelled power density (dBm) at each birth address for base stations within 1400 m, using a purpose designed propagation model. This took the form of the equation in the figure. Exposures beyond 1400 m were considered to be at background levels.

Derivation of modelled power density

We used measurements from two field campaigns, in a rural and urban area, to set values for the user defined parameters in the power density model. Geographic coordinates of each measurement location (1 m accuracy) were obtained with the global positioning system. Data on surface height and distance and azimuth (compass direction) to the base station were derived in a geographical information system (ArcGIS). The rural survey comprised 151 sites (1510 antenna specific measurements) around a group of four base stations in an isolated and relatively flat rural location near Bowes, County Durham; the urban survey covered 50 sites (658 antenna specific measurements) in Cheltenham, Gloucestershire. Measurements were made of field strength in the broadcast control channel (BCCH) carrier frequency for each base station, which provides a temporally stable signal proportional to total power output, with a Narda SRM 3000 spectrum analyser and isotropic probe (a technical appendix is available from the authors). Zero values were set to −70 dBm, the limit of detection of the measurements using the settings we applied in the field.

Model parameters were optimised by a path following search technique, in which the settings were sought that gave the maximum R2 and minimum root mean squared error (RMSE) while satisfying the criteria that the regression slope was 0.8-<1.2 and the fractional bias was −0.2-<0.2. Different parameter settings were found to be necessary for urban and rural areas: R2 for measured versus modelled power densities was 0.57 for the 1510 antenna specific rural measurements (0.65 for total power density at the 151 sites) and 0.30 (0.40) for the urban area (see fig A on bmj.com).

The models were validated with data from two further surveys, following the same measurement protocol. Data for validation of the rural model were collected from 145 sites along transects radiating from five groups of base stations (1044 antenna specific readings) in locations across Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire. Urban validation was done with measurements at 13 sites (234 antenna specific measurements) in Banbury, Oxfordshire. Comparison of the antenna specific measurements with modelled estimates gave R2=0.56 for the rural sites and 0.24 for the urban area. Comparisons using all the data from all four surveys (calibration and validation) gave R2=0.64 at the antenna level and 0.62 at site level.

Further fieldwork was undertaken to assess the performance of the model in “real world” settings. Total power densities across all frequencies used for Global System for Mobile communications 900 and 1800 were measured at 620 locations across the country by geometric averaging of 64 sweeps of the frequency range with the Narda spectrum analyser. The locations were selected in a random stratified framework to represent urban, suburban, and rural areas and different micro-environments, from open to densely cluttered by buildings or vegetation. Fig B on bmj.com shows boxplots of measured power density at these locations.

Spearman’s r correlation between measured and modelled power density was 0.66. The correlation of measured power density with distance from nearest base station was −0.72 and 0.66 with total power output.

Statistical methods

Statistical analyses were carried out in the statistical package R21 with conditional logistic regression. The three exposure metrics estimated at the birth address for each case and control were time averaged across monthly estimates for the duration of the pregnancy (assumed to be nine months) because exposures in utero might be the most relevant period for early onset childhood leukaemia22 (when the birth occurred after the 15th of the month, the birth month was included in the nine month period). The temporal resolution of the exposure data was not considered sufficient to allow reliable estimates for shorter periods, such as month of birth, and because among the 1397 affected children, 528 (38%) moved residence between birth and diagnosis, analyses for exposure periods that extended beyond birth were not considered meaningful. Each exposure metric was divided into three categories: we used thirds (based on values for all cases and controls) for distance from nearest base station and modelled power density; for total power output, because of the large number (58%) of cases and controls with no base stations within 700 metres, we used a zero group together with two equal sized groups for non-zero values. We also carried out regression analyses using continuous measures of the exposure metrics.

We present unadjusted analyses and analyses after sequential adjustment for the main potential sociodemographic confounders affecting the geographical distribution of brain cancer and leukaemia,23 24 measured at small area (census output area) level and categorised into fifths. These comprised the percentage of population with education to degree level or higher and Carstairs score (a composite area deprivation measure25) and the population density and population mixing (percentage inward migration to the output area over the previous year). Potential confounding data were all sourced from the 2001 census. We report 95% confidence intervals and two sided P values, with no correction for multiple testing.

Results

Of the 1397 cases, there were 251 brain and central nervous system cancers and 527 cases of leukaemia and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Mean age at diagnosis was 2.0 (SD 1.2) years. The mean distance of registered address at birth from a base station was 1107 (SD 1131) m for cases and 1073 (SD 1130) m for controls (P=0.31); the mean total power output of base stations within 700 m was 2.89 (SD 5.9) kW for cases and 3.00 (SD 6.0) kW for controls (P=0.54); and the mean modelled power density was −30.3 (SD 21.7) dBm for cases and −29.7 (SD 21.5) dBm for controls (P=0.41) (table 1). Mean values of the sociodemographic measures were similar for cases and controls (see table A on bmj.com). Total power output and modelled power density were positively correlated (Spearman’s r=0.62), and they were inversely correlated with distance from nearest base station (r=−0.82 and −0.74, respectively). Correlations between the exposure metrics and sociodemographic measures ranged up to│0.36│(distance and population density) (see table B on bmj.com). Spearman’s correlations between estimated exposures of cases in the nine months before and nine months after birth (based on birth address) were 0.95, 0.96, and 0.94 for distance, total power output, and modelled power density, respectively. Mean distance of birth address from nearest FM, television, and VHF broadcast antennas in England and Wales was similar for cases and controls (see table C on bmj.com).

Table 1.

Mean (SD) of exposure metrics for cases (children aged 0-4 with specified cancer) and controls matched for sex and age by cancer site

| Cancer | Distance from nearest base station (m) | Total power output within 700 m (kW) | Modelled power density (dBm) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | P | Mean (SD) | P | Mean (SD) | P | |||

| All | ||||||||

| Cases (n=1397) | 1107 (1131) | 0.31 | 2.89 (5.9) | 0.54 | −30.3 (21.7) | 0.41 | ||

| Controls (n=5588) | 1073 (1130) | 3.00 (6.0) | −29.7 (21.5) | |||||

| Brain and central nervous system | ||||||||

| Cases (n=251) | 1006 (746) | 0.27 | 2.48 (5.6) | 0.25 | −30.9 (21.3) | 0.31 | ||

| Controls (n=1004) | 1068 (998) | 2.94 (5.9) | −29.4 (21.3) | |||||

| Leukaemia and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | ||||||||

| Cases (n=527) | 1154 (1294) | 0.20 | 2.94 (6.1) | 0.84 | −30.8 (22.1) | 0.56 | ||

| Controls (n=2108) | 1076 (1069) | 2.88 (5.9) | −30.2 (21.7) | |||||

Table 2 shows the results for the categorical analyses and table 3 for the continuous analyses. We found no association between mobile phone base stations and risk of cancer. In the fully adjusted analyses, for modelled power density at birth address, compared with the lowest exposure category, the odds ratio for brain and central nervous system cancer was 0.97 (95% confidence interval 0.69 to 1.37) in the intermediate and 0.76 (0.51 to 1.12) in the highest exposure category (P=0.33 for trend); for leukaemia and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, odds ratios were 1.16 (0.90 to 1.48) and 1.03 (0.79 to 1.34), respectively (P=0.51 for trend) (table 2).

Table 2.

Odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) for categories of three exposure metrics by site of cancer in children aged 0-4

| Exposure category* | Distance from nearest base station (m) | Total power output (kW) | Modelled power density (dBm) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Unadjusted | Adjusted† | Adjusted‡ | Cases | Unadjusted | Adjusted† | Adjusted‡ | Cases | Unadjusted | Adjusted† | Adjusted‡ | |||

| All cancers | ||||||||||||||

| Lowest | 484 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 808 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 482 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Intermediate | 448 | 0.91 (0.79 to 1.05) | 0.92 (0.80 to 1.07) | 0.93 (0.80 to 1.08) | 298 | 1.00 (0.86 to 1.16) | 1.01 (0.87 to 1.17) | 1.01 (0.87 to 1.18) | 456 | 0.97 (0.84 to 1.12) | 1.00 (0.86 to 1.16) | 1.01 (0.87 to 1.18) | ||

| Highest | 465 | 0.95 (0.82 to 1.10) | 0.98 (0.84 to 1.14) | 1.00 (0.85 to 1.17) | 291 | 0.97 (0.83 to 1.13) | 1.00 (0.8 to 1.17) | 1.03 (0.87 to 1.21) | 459 | 0.98 (0.85 to 1.13) | 1.00 (0.86 to 1.17) | 1.02 (0.88 to 1.20) | ||

| P (trend) | — | 0.39 | 0. 64 | 0.85 | — | 0.68 | 0.98 | 0.75 | — | 0.70 | 0.99 | 0.79 | ||

| Brain and central nervous system | ||||||||||||||

| Lowest | 85 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 150 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 93 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Intermediate | 85 | 0.93 (0.67 to 1.29) | 0.94 (0.67 to 1.31) | 0.95 (0.67 to 1.34) | 56 | 1.03 (0.73 to 1.45) | 1.03 (0.72 to 1.46) | 1.02 (0.72 to 1.46) | 80 | 0.99 (0.71 to 1.37) | 1.00 (0.71 to 1.40) | 0.97 (0.69 to 1.37) | ||

| Highest | 81 | 0.93 (0.66 to 1.31) | 0.94 (0.65 to 1.36) | 0.95 (0.65 to 1.38) | 45 | 0.84 (0.58 to 1.21) | 0.84 (0.56 to 1.27) | 0.83 (0.54 to 1.25) | 78 | 0.78 (0.55 to 1.12) | 0.77 (0.53 to 1.12) | 0.76 (0.51 to 1.12) | ||

| P (trend) | — | 0.64 | 0.73 | 0.75 | — | 0.34 | 0.41 | 0.36 | — | 0.35 | 0.39 | 0.33 | ||

| Leukaemia and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | ||||||||||||||

| Lowest | 182 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 305 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 179 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Intermediate | 167 | 0.94 (0.75 to 1.19) | 0.96 (0.76 to 1.22) | 0.99 (0.78 to 1.27) | 112 | 1.04 (0.82 to 1.33) | 1.05 (0.82 to 1.34) | 1.08 (0.84 to 1.38) | 179 | 1.07 (0.85 to 1.35) | 1.11 (0.87 to 1.41) | 1.16 (0.90 to 1.48) | ||

| Highest | 178 | 0.98 (0.78 to 1.24) | 1.00 (0.78 to 1.28) | 1.05 (0.81 to 1.35) | 110 | 1.02 (0.80 to 1.31) | 1.04 (0.80 to 1.35) | 1.08 (0.8 to 1.42) | 169 | 0.98 (0.77 to 1.25) | 0.99 (0.77 to 1.28) | 1.03 (0.79 to 1.34) | ||

| P (trend) | — | 0.82 | 0.95 | 0.75 | — | 0.87 | 0.80 | 0.58 | — | 0.88 | 0.74 | 0.51 | ||

*For distance (m): lowest= ≥1071.8, intermediate=612.1-1071.7, highest=0-612.0; for total power output (kW): lowest= 0, intermediate= 0.001-4.742, highest=≥4.743; for modelled power density (dBm): lowest= −70-−26.4659, intermediate= −26.4658-−17.6966; highest= ≥−17.6965 (equivalent to lowest= 0-0.002256, intermediate=0.002257-0.016996, highest= ≥0.016997 in mW/m2).

†Percentage of population with education to degree level or higher and Carstairs deprivation score.

‡Percentage of population with education to degree level or higher, Carstairs deprivation score, population density, and population mixing.

Table 3.

Odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) for 15th to 85th centile change in continuous measures of three exposure metrics by site of cancer in children aged 0-4

| No of cases | Distance from nearest base station (for decrease of 1212 m) | Total power output (for increase of 6.75 kW) | Modelled power density (for increase of 57.2 dBm) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted* | Adjusted† | Unadjusted | Adjusted* | Adjusted† | Unadjusted | Adjusted* | Adjusted† | |||

| All cancers | |||||||||||

| 1397 | 0.97 (0.91 to 1.03) | 0.98 (0.92 to 1.04) | 0.99 (0.93 to 1.06) | 0.98 (0.92 to 1.05) | 0.99 (0.92 to 1.07) | 1.00 (0.93 to 1.08) | 0.93 (0.80 to 1.10) | 0.96 (0.82 to 1.13) | 0.98 (0.83 to 1.17) | ||

| Brain and central nervous system | |||||||||||

| 251 | 1.09 (0.91 to 1.32) | 1.12 (0.92 to 1.38) | 1.12 (0.91 to 1.39) | 0.91 (0.76 to 1.08) | 0.90 (0.74 to 1.09) | 0.89 (0.73 to 1.09) | 0.83 (0.57 to 1.20) | 0.83 (0.57 to 1.25) | 0.82 (0.55 to 1.22) | ||

| Leukaemia and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | |||||||||||

| 527 | 0.93 (0.85 to 1.03) | 0.94 (0.85 to 1.04) | 0.97 (0.87 to 1.08) | 1.01 (0.91 to 1.13) | 1.02 (0.90 to 1.14) | 1.03 (0.91 to 1.16) | 0.93 (0.72 to 1.20) | 0.94 (0.73 to 1.22) | 1.00 (0.75 to 1.31) | ||

*Percentage of population with education to degree level or higher and Carstairs deprivation score.

†Percentage of population with education to degree level or higher, Carstairs deprivation score, population density, and population mixing.

In analyses of the exposure metrics as continuous variables, for brain and central nervous system cancer, fully adjusted odds ratios for a 15th to 85th centile difference in the exposure variable ranged from 0.82 (0.55 to 1.22; modelled power density) to 1.12 (0.91 to 1.39; distance); and for leukaemia and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, from 0.97 (0.87 to 1.08; distance) to 1.03 (0.91 to 1.16; total power output) (table 3). Addition of a quadratic term to the continuous exposure models was of borderline significance (P=0.05) for brain and central nervous system cancer, for which risk was lower with higher estimated levels of exposure.

Discussion

In this systematic national investigation we found no association between risk of cancer in young children and estimated exposures to radiofrequency from mobile phone base stations during pregnancy.

Comparison with other studies

To date, there is no convincing or consistent evidence from cellular or animal studies to suggest that exposure to radiofrequency electromagnetic fields is associated with brain tumours or risk of other cancers26 27.Furthermore, uptake of mobile telephony has not been mirrored by trends in the incidence of brain tumours or acoustic neuromas.4 28 Radiofrequency exposures in the general population from mobile phone base stations are extremely low, in the order 1000 to 10 000 times lower than values in the guidelines of the International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection (ICNIRP).29 For example, in the 900 MHz frequency band, the reference level (based on heating effects) is 36.6 dBm (4.5W/m2; dBm=10*log10 mW/m2), which compares with a median modelled power density among controls in our study of −4.9 dBm (0.32 mW/m2) and maximum modelled power density of 9.4 dBm (8.6 mW/m2). For comparison, estimated power density at a distance of 18 m from a 100 W incandescent light bulb is −2.22 dBm (0.6 mW/m2).30 It has been estimated that one day’s exposure from a base station at an incident level of 1-2 V/m (about 4.2-10 dBm or 2-10 mW/m2) corresponds to about the first 4 seconds of local exposure to the head and about 30 minutes of whole body exposure arising from the use of a mobile phone.14 15 Even at low levels of exposure, however, there are theoretical concerns about the effects on children because of relatively greater dose (per kg body mass), the potential greater susceptibility of children compared with adults,17 and potential effects of lifelong, cumulative exposures.16 17 For these reasons, in the UK it has been recommended that exposure of children to mobile telephony should be minimised.1

The few previous reports of excess risks of cancer near mobile phone base stations were based on apparent clusters of small numbers of affected people living nearby.9 10 11 Such reports of individual clusters are difficult to evaluate as they are subject to possible selection and reporting biases. Problems include “boundary shrinkage,” whereby estimates of risk are exaggerated by choice of areas/time periods/demographic strata for study, variable ascertainment or duplication of cases, denominator errors, and publication bias.12 There are also reports of weak31 32 33 34 35 36 37 and inconsistent38 39 40 41 geographical associations between risk of leukaemia (including childhood leukaemia) and proximity to radio and television broadcast antennas, another source of low level radiofrequency exposures to the population. Two recent case-control studies—which used propagation models to estimate total radiofrequency exposure from radio and television transmitters at the home address of each child36 37 41—found no association with childhood leukaemia, though one study did report an excess risk of lymphocytic leukaemia associated with peak exposures.37

Strengths and limitations of study

Major strengths of our study include its size and national coverage, hence avoiding selection and reporting effects (bias) in the choice of cases and areas for study. Our use of modelling and validation represents an advance on the assessment of exposure for studying risk of cancer near mobile phone base stations because previous studies relied on distance measures only.9 10 11 In comparison with purely distance based methods, modelled estimates of exposure are able to take into account the characteristics of and contribution from multiple transmitters.42 Also, because we focused on early childhood cancers, we avoided problems of long latency that affect interpretation of mobile phone studies in adults.2

Our focus on early childhood cancers, however, meant that we did not include longer term or other potential health effects that have been associated with mobile telephony.1 3 4 6 We assumed that radiofrequency exposures from mobile phone base stations estimated at registered birth address are representative of true individual exposures during pregnancy. We were unable to account for any attenuation of radiofrequency exposures within the home nor could we obtain personal measurements of individual exposures of the mothers from mobile phone base stations43 as cases and controls were identified from national registers, without individual contact. In addition, our models did not include information on other sources of radiofrequency exposure, such as from microcells or picocells, cordless phone base stations, maternal use of mobile/DECT phones during pregnancy, or radio and television transmitters (though distance from nearest radio and television transmitters was similar for cases and controls). Neither were we able to take account of migration of the mother during pregnancy.44 Despite the large study size, such potential misclassification of exposure and migratory effects could have reduced the ability of the study to detect any true excess in risk. In addition, we were unable to investigate possible health effects from exposures to mobile phone base stations after birth; whereas we had address at birth and diagnosis for cases, data on controls, obtained from the national births register, were available only at birth. Based on birth address, correlations of the exposure metrics in the nine months before and after birth were high (≥0.94), but this does not take account of migration before or after birth. The focus on prenatal exposures could be an important limitation to the extent that postnatal exposures might be relevant to the incidence of early childhood cancers.22

Conclusions and policy implications

In summary, we found no association between risk of childhood cancers and mobile phone base station exposures during pregnancy. The results of our study should help to place any future reports of cancer clusters near mobile phone base stations in a wider public health context.

What is already known on this topic

Previous reports of apparent cancer clusters near mobile phone base stations are difficult to interpret because of small numbers and possible selection and reporting biases

There is no known radiobiological explanation for such cancer excesses

What this study adds

This study used national registers of cancers and births and available data on macrocell mobile phone base stations, thus avoiding selection and reporting biases

There was no association between risk of early childhood cancers and estimates of exposure to mobile phone base stations during pregnancy

We are grateful to Les Barclay, David Bacon, and Michael Willis who advised on exposure aspects of the study; Clair Chilvers for advice on study design; Margaret Douglass, Peter Hambly, Catherine Keshishian and Chloe Morris for their help with data extraction and checking; Nirupa Dattani, Gloria Brackett, Nicola Cooper (Office for National Statistics), Ian Brown (General Register Office Scotland), Fiona Campbell, and Lesley Bhatti (Scottish Information and Statistics Division) for their help with checking cancer cases, obtaining birth controls, and data linkage.

Contributors: PE and DJB conceived the study and obtained funding. DJB was responsible for the fieldwork. LB and KdH carried out the geographical information system analysis. MBT was responsible for the data extractions, linkage, and checking. JB and MBT carried out the data analysis under the supervision of NB, DJB, and PE. PE, MT, JB, KdH, and DJB interpreted the results and drafted the paper. All authors approve the final draft of the paper. PE is guarantor.

Funding: The study was funded through the UK Mobile Telecommunications Health Research (MTHR) Programme (www.mthr.org.uk), an independent body set up to provide funding for research into the possible health effects of mobile telecommunications. The MTHR is jointly funded by the UK Department of Health and the mobile telecommunications industry. Members of the independent MTHR programme management committee approved the study design and commented on a draft manuscript. Data collection and analysis, interpretation of data, and the decision to submit the paper for publication were the sole responsibility of the authors.

Competing interests: MBT, JB, LB, KdH, and NB declare that the answers to the questions on the Unified Competing interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_discolure.pdf are all No and therefore declare that they have no conflicts of interest. PE and DJB obtained funding in support of this work from MTHR. PE was a member of the MTHR programme management committee.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the St Mary’s NHS Trust local research ethics committee.

Data sharing: A technical appendix describing the derivation of modelled power density in more detail is available from the corresponding author.

Cite this as: BMJ 2010;340:c3077

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Table A Descriptive statistics for sociodemographic measures

Table B Correlations (Spearman’s) between exposure metrics and sociodemographic indicators

Table C Mean (SD) distance to nearest radio and TV masts, England and Wales

Fig A Scattergrams of measured and modelled total power density (dBm)

Fig B Boxplots and histogram of measured power density

References

- 1.Independent Expert Group on Mobile Phones. Mobile phones and health. 2000. www.iegmp.org.uk/report/text.htm.

- 2.Kundi M. The controversy about a possible relationship between mobile phone use and cancer. Environ Health Perspect 2009;117:316-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khurance VG, Teo C, Kindi M, Hardell L, Carlberg M. Cell phones and brain tumors: a review including the long-term epidemiologic data. Surg Neurol 2009;72:205-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schüz J, Waldemar G, Olsen JH, Johansen C. Risks for central nervous system diseases among mobile phone subscribers: a Danish retrospective cohort study. PLoS One 2009;4:e4389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Otitoloju AA, Obe IA, Adewale OA, Otubanjo OA, Osunkalu VO. Preliminary study on the induction of sperm head abnormalities in mice, Mus musculus, exposed to radiofrequency radiations from global system for mobile communication base stations. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol 2010;84:51-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kundi M, Hutter HP. Mobile phone base stations—effects on well-being and health. Pathophysiol 2009;16:123-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blettner M, Schlehofer B, Breckenkamp J, Kowall B, Schmiedel S, Reis U, et al. Mobile phone base stations and adverse health effects: phase 1 of a population-based, cross sectional study in Germany. Occup Environ Med 2009;66:118-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siegrist M, Earle TC, Gutscher H, Keller C. Perception of mobile phone and base station risks. Risk Anal 2005;25:1253-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eger H, Hagen KU, Lucas B, Vogel P, Voit H. Einfluss der räumlichen Nähe von Mobilfunksendeanlagen auf die Krebsinzidenz. Umwelt Medizin Gesellschaft 2004;17:326-32. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolf R, Wolf D. Increased incidence of cancer near a cell-phone transmitter station. Int J Cancer Prevention 2004;1:1-19. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oberfeld G. Umweltepidemiologische Untersuchung der Krebsinzidenz in den Gemeinden Hausmannstätten & Vasoldsberg. Das Land Steiermark. 2008. www.der-mast-muss-weg.de/pdf/studien/OBERFELD_2008_1_16.pdf.

- 12.Elliott P, Wartenberg D. Spatial epidemiology: current approaches and future challenges. Environ Health Perspect 2004;112:998-1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schüz J, Lagorio S, Bersani F. Electromagnetic fields and epidemiology: an overview inspired by the fourth course at the International School of Bioelectromagnetics. Bioelectromagnetics 2009;30:511-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neubauer G, Feychting M, Hamnerius Y, Kheifets L, Kuster N, Ruiz I, et al. Feasibility of future epidemiological studies on possible health effects of mobile phone base stations. Bioelectromagnetics 2007;28:224-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Regel S, Roosli M, Negovetic S, Schuderer J, Berdinas V, Huss A, et al. Effects of UMTS base station like exposure on well-being and cognitive performance. Environ Health Perspect 2006;114:1270-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krewski D, Glickman BW, Habash RW, Habbick B, Lotz WG, Mandeville R, et al. Recent advances in research on radiofrequency fields and health: 2001-2003. J Toxicol Environ Health Part B Crit Rev 2007;10:287-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kheifets L, Repacholi M, Saunders R, van Deven E. The sensitivity of children to electromagnetic fields. Pediatrics 2005;116:e303-e13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ordnance Survey. Address-point. 2010. www.ordnancesurvey.co.uk/oswebsite/products/addresspoint/.

- 19.Mann SM, Cooper TG, Allen SG, Blackwell RP, Lowe AJ. Exposure to radiowaves near mobile phone base stations. NRPB report R321. Stationery Office, 2000.

- 20.Schüz J, Mann S. A discussion of potential exposure metrics for use in epidemiological studies on human exposure to radiowaves from mobile phone base stations. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol 2000;10:600-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.R Foundation for Statistical Computing. The R Project for Statistical Computing. 2010. www.r-project.org/.

- 22.Belson M, Kingsley B, Holmes A. Risk factors for acute leukemia in children: a review. Environ Health Perspect 2007;115:138-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eaton N, Shaddick G, Dolk H, Elliott P. Small-area study of the incidence of neoplasms of the brain and central nervous system among adults in the West Midlands region, 1974-86. Small Area Health Statistics Unit. Br J Cancer 1997;75:1080-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodrigues L, Hills M, McGale P, Elliott P. Socioeconomic factors in relation to childhood leukaemia and non-Hodgkin lymphomas: an analysis based on small area statistics for census tracts. In: Draper G, ed. The geographical epidemiology of childhood leukaemia and non-Hodgkin lymphomas in Great Britain, 1966-83. Studies in Medical and Population Subjects No 53. HMSO, 1991:47-56.

- 25.Carstairs V, Morris R. Deprivation: explaining differences in mortality between Scotland and England and Wales. BMJ 1989;299:886-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements. Biologic effects of modulated radiofrequency fields. CRP, 2003.

- 27.National Radiological Protection Board. Review of the scientific evidence for limiting exposure to electromagnetic fields (0-300 GHz). Doc NRPB 2004;15:1-227. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nelson PD, Toledano MB, McConville J, Quinn MJ, Cooper N, Elliott P. Trends in acoustic neuroma and cellular phones: is there a link? Neurology 2006;66:284-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.International Commission on Non-ionizing Radiation Protection. Guidelines for limiting exposure to time-varying electric, magnetic and electromagnetic fields (up to 300GHz). Health Phys 1998;74:494-522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adair RK. Environmental objections to the PAVE PAWS radar system, a scientific review. Radiat Res 2003:159;128-43. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Maskarinec G, Cooper J, Swygert L. Investigation of increased incidence in childhood leukemia near radio towers in Hawaii: preliminary observations. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol 1994;13:33-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dolk H, Shaddick G, Walls P, Grundy C, Thakrar B, Kleinschmidt I, et al. Cancer incidence near radio and television transmitters in Great Britain, I. Sutton Coldfield transmitter. Am J Epidemiol 1997;145:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hocking B, Gordon JR, Grain HL, Hatfield GE. Cancer incidence and mortality and proximity to TV towers. Med J Aust 1996;165:601-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Michelozzi P, Capon A, Kirchmayer U, Forastiere F, Biggeri A, Barca A, et al. Adult and childhood leukemia near a high-power radio station in Rome, Italy. Am J Epidemiol 2002;155:1096-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park SK, Ha M, Im HJ. Ecological study on residences in the vicinity of AM radio broadcasting towers and cancer death: preliminary observation in Korea. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2004;77:387-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ha M, Im H, Lee M, Kim HJ, Kim BC, Gimm YM, et al. Radio-frequency radiation exposure from AM radio transmitters and childhood leukemia and brain cancer. Am J Epidemiol 2007;166:270-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ha M, Im H, Kim BC, Gimm YM, Pack JK. Five authors reply [letter]. Am J Epidemiol 2008;167:884-5. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dolk H, Elliott P, Shaddick G, Walls P, Thrakrar B. Cancer incidence near radio and television transmitters in Great Britain. II. All high power transmitters. Am J Epidemiol 1997;145:10-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McKenzie DR, Yin Y, Morrell S. Childhood incidence of acute lymphoblastic leukemia and exposure to broadcast radiation in Sydney—a second look. Aust N Z J Public Health 1998;22:360-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cooper D, Hemmings K, Saunders P. Re: Cancer incidence near radio and television transmitters in Great Britain. I. Sutton Coldfield transmitter; II. All high power transmitters. Am J Epidemiol 2001;153:202-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Merzenich H, Schmiedel S, Bennack S, Brüggemeyer H, Philipp J, Blettner M, et al. Childhood leukemia in relation to radio frequency electromagnetic fields in the vicinity of television and radio broadcast transmitters. Am J Epidemiol 2008;168:1169-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schmiedel S, Brüggemeyer H, Philipp J, Wendler J, Merzenich H, Schüz J. An evaluation of exposure metrics in an epidemiologic study on radio and television broadcast transmitters and the risk of childhood leukemia. Bioelectromagnetics 2009;30:81-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berg-Beckhoff G, Blettner M, Kowall B, Breckenkamp J, Schlehofer B, Schmiedel S, et al. Mobile phone base stations and adverse health effects: phase 2 of a cross-sectional study with measured radio frequency electromagnetic fields. Occup Environ Med 2009;66:124-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Canfield M, Ramadhani T, Langlois P, Waller D. Residential mobility patterns and exposure misclassification in epidemiologic studies of birth defects. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 2006;16:538-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table A Descriptive statistics for sociodemographic measures

Table B Correlations (Spearman’s) between exposure metrics and sociodemographic indicators

Table C Mean (SD) distance to nearest radio and TV masts, England and Wales

Fig A Scattergrams of measured and modelled total power density (dBm)

Fig B Boxplots and histogram of measured power density