Abstract

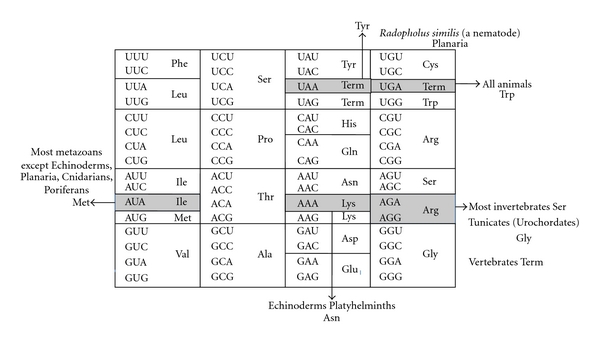

In animal mitochondria, six codons have been known as nonuniversal genetic codes, which vary in the course of animal evolution. They are UGA (termination codon in the universal genetic code changes to Trp codon in all animal mitochondria), AUA (Ile to Met in most metazoan mitochondria), AAA (Lys to Asn in echinoderm and some platyhelminth mitochondria), AGA/AGG (Arg to Ser in most invertebrate, Arg to Gly in tunicate, and Arg to termination in vertebrate mitochondria), and UAA (termination to Tyr in a planaria and a nematode mitochondria, but conclusive evidence is lacking in this case). We have elucidated that the anticodons of tRNAs deciphering these nonuniversal codons (tRNATrp for UGA, tRNAMet for AUA, tRNAAsn for AAA, and tRNASer and tRNAGly for AGA/AGG) are all modified; tRNATrp has 5-carboxymethylaminomethyluridine or 5-taurinomethyluridine, tRNAMet has 5-formylcytidine or 5-taurinomethyluridine, tRNASer has 7-methylguanosine and tRNAGly has 5-taurinomethyluridine in their anticodon wobble position, and tRNAAsn has pseudouridine in the anticodon second position. This review aims to clarify the structural relationship between these nonuniversal codons and the corresponding tRNA anticodons including modified nucleosides and to speculate on the possible mechanisms for explaining the evolutional changes of these nonuniversal codons in the course of animal evolution.

1. Introduction

Up to now six codons have been known which are deciphered by the corresponding tRNAs as amino acids different from those assigned by the universal genetic code in animal mitochondria (Figure 1) [1]. UGA termination codon in the universal genetic code is deciphered to Trp in all animal mitochondria, AUA Ile to Met in most metazoan except echinoderm, planarian, cnidarian, placozoan and poriferan mitochondria, AAA Lys to Asn in echinoderm and some platyhelminth mitochondria, and AGA/AGG Arg to Ser in most invertebrate mitochondria, Gly in tunicate (urochordata) mitochondria, and termination codon in vertebrate mitochondria. UAA termination codon was assumed to be a Tyr codon in a planaria [2] and a nematode mitochondria [3], but there is neither structural information on mt tRNATyr that decodes the UAA codon, nor information about the mitochondrial (mt) release factor relevant to this phenomenon. Thus, this issue is no more discussed here.

Figure 1.

Universal genetic code (inside the box) and variations in animal mt genetic code (outside). Term: termination codon.

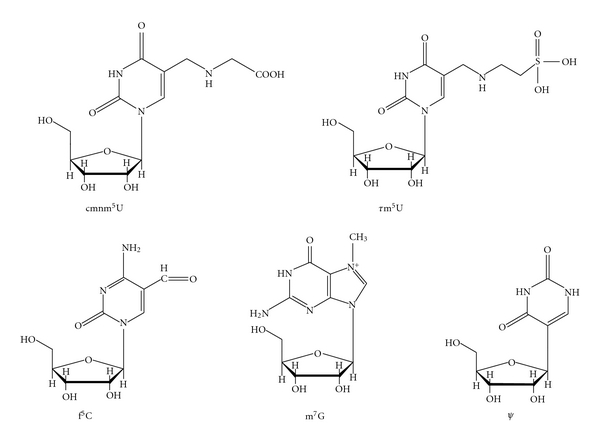

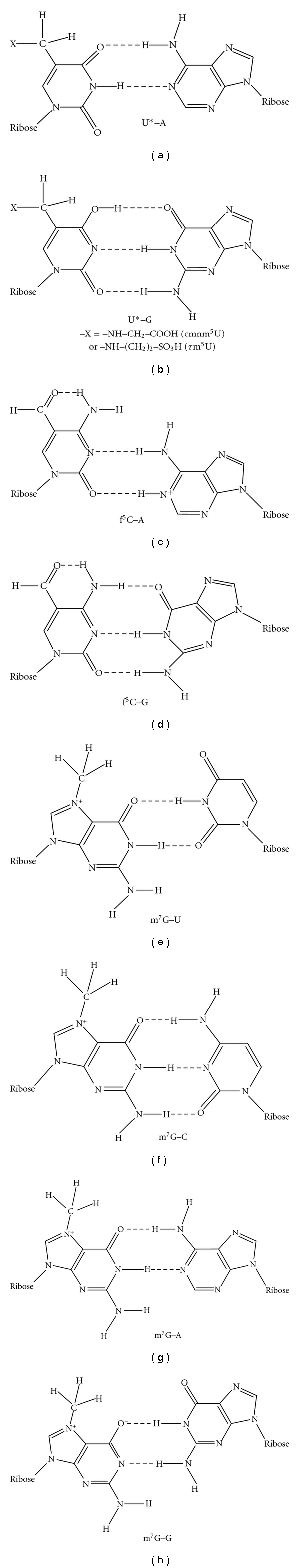

The codon-amino acid correspondence was first deduced by comparison of mt DNA sequence containing the codon with amino acid sequence of the corresponding protein [4]. Since mt proteins exist in a small number (in most cases, 13) and which are encoded by a small sized mt DNA (16,500 bp in the case of human mitochondria) [5], the correspondence can be unambiguously accomplished. In the next step, in order to analyze the molecular mechanism of the codon change, the corresponding tRNA sequence was analyzed especially focused on the anticodon sequence [6]. It is an advantageous point for analysis of mt tRNAs that in metazoan mitochondria, tRNA genes are restricted to 22~24 species on the mt genomes, and that tRNAs are not imported from the cytoplasm in almost all metazoan mitochondria [7] except for a few cases such as in Cnidaria. As the results, several modified nucleosides such as 5-carboxymethylaminomethyl(2-thio)uridine(cmnm5(s2)U), 5-taurinomethyl(2-thio)uridine (τm5(s2)U), 5-formylcytidine(f5C), 7-methylguanosine(m7G) in the anticodon first position, and pseudouridine (Ψ) in the anticodon second position were found to be involved in the genetic code variations (Figure 2), in which τm5(s2)U [8] and f5C [9] are novel modified nucleosides found by our group. Thus, an expanded wobble rule was established in which cmnm5(s2)U, τm5U, and f5C at the anticodon first position pair with A or G in the codon third position, and m7G pairs with all nucleotides in the codon third position [10, 11] (Figure 3). It was speculated that unmodified G in the anticodon first position should pair with C, U, and A in the codon third position in the case of fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster tRNASerGCU for decoding AGU/AGC/AGA codons [11], and Ψ in the anticodon second position strengthens the pairing interaction with A in the codon second position in the case of echinoderm tRNAAsnGΨU for decoding AAA codon [12]. In the third step, the wobble pairings as inferred from the above-expanded wobble rule were confirmed by an in vitro translation system of animal mitochondria, in which in vitro translation was performed by E. coli or bovine mt translation system using synthetic polyribonucleotide made of a series of nonuniversal codon as a messenger, and incorporation of a certain amino acid corresponding to the nonuniversal codon was identified [13, 14]. In the forth step, the wobble pairings were confirmed by an in vitro experiment, in which natural mRNA including a specific codon which was replaced with a certain nonuniversal codon was translated in vitro, and the mRNA activity was detected by enzymatic activity if the mRNA encodes a certain enzyme such as dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) (Hanada, T., Suzuki, T. and Watanabe, K., unpublished results).

Figure 2.

Chemical structures of modified nucleosides located at the anticodon wobble position (cmnm5U, τm5U, f5C, and m7G) and the second position (Ψ) of mt tRNAs.

Figure 3.

Possible scheme of base pairing between modified nucleosides at the anticodon wobble position and nucleosides at the codon third position in animal mitochondrial translation systems. These structures are only schematic drawing of base-pairing and do not show precise dimension of each nucleoside.

In this review, we summarize mostly the results obtained in the second step, together with a few cases in the third step, and inquire into the nature of codon-anticodon interaction in the mt translation process and the relationship between nonuniversal genetic code and modified nucleoside in the tRNA anticodon deciphering the codon, during the course of animal evolution. These studies may lead to the understanding as to how the genetic code evolves and how mt tRNAs keep up with the genetic code variations by providing modification at the anticodon of tRNAs.

It is also important to consider the involvement of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase (aaRS) in the recognition of tRNA, especially in the case when aaRS recognizes the anticodon region of tRNA as the identity determinant. Since a few cases have been known about the animal mt aaRSs, some discussions will be added in the applicable sections, about the recognition mechanisms of aaRSs toward the corresponding tRNAs involved in the genetic code variations.

2. Genetic Code Variations and the Anticodon Structure of the Corresponding tRNA

2.1. cmnm5(s2)U for Decoding UGA/UGG Codons

In mitochondria of all animal phyla, UGA is read as Trp instead of termination codon in the universal genetic code [4, 6]. In the protostome (nematode and probably platyhelminth) mitochondria, the anticodon first position (wobble position) is modified to 5-carboxymethylaminomethyluridine (cmnm5U) or 5-carboxymethylaminomethyl-2-thiouridine (cmnm5s2U) [15, 16]. Therefore, the modification of U to cmnm5(s2)U in the anticodon first position in tRNATrpUCA may restrict the base pairing only with purine nucleosides (A/G, symbolized by R) at the codon third position (Figures 3(a) and 3(b)), which would overcome the competition with mitochondrial release factor. Thus, UGA codon is read as Trp. It is known that unmodified uridine (U) at the wobble position recognizes all four nucleosides (A/G/U/C, symbolized by N) at the codon third position [17]; thus, in mitochondria all four codon boxes are mostly read by the respective single tRNAs with unmodified U at the anticodon wobble position (see Figure 1).

cmnm5U was first found in yeast mitochondria [18]. This modified uridine is similar in the chemical structure with cmnm5Um (5-carboxymethylaminomethyl-O-2′-methyluridine) in Escherichia coli tRNALeu4 [19] and mnm5U in E. coli tRNAArg and is considered to fix its conformation by interresidual hydrogen bonding. The mnm5U possesses the same side chain at position 5 of uracil base as mnm5s2U in tRNAGlu, which enables to take “rigid” conformation for the construction of the C3′-endo form.

In the in vitro translation system using MS2 RNA as a messenger, tRNALeu4 having cmnm5Um and tRNALeu5 having 2′-O-methylcytidine (Cm) at the anticodon first position, both recognized UUA and UUG codons, but not UUU and UUC codons at all [20]. It was clarified by NMR analysis that the orthodox C3′-endo-G− form of both cmnm5Um and Cm are very stable. It is considered that the posttranscriptional modification to form cmnm5Um and Cm fixes their conformations very rigid, which regulates not to recognize the UUU/UUC codons [21].

In summary, in the tRNAs recognizing A- or G-ending codons by dividing 2:2 in the codon box, U and C (in the case of f5C, see Section 2.3) at the anticodon first position are modified by introducing side chains to position 5 of the nucleobase, 2-thiolation at position 2 of the nucleobase, or methylation at position 2 of the ribose moiety. By combining these modifications, the conformation of the nucleoside becomes more rigid and which guarantees the precise recognition toward NNA/NNG codons (Figures 3(a) and 3(b)) [22].

2.2. τm5U for Decoding UGA/UGG and AGA/AGG Codons

In the tunicate (ascidian) and vertebrate mitochondria, the anticodon first letter of tRNATrp is modified to 5-taurinomethyuridine (τm5U) ([8, 23]). The same position of ascidian Halocynthia roretzi mt tRNAGly is also occupied by τm5U [23]. That τm5U recognizes only A- and G-ending codons (Figures 3(a) and 3(b)) were verified in two ways. Yasukawa et al. examined the translation activity of human tRNALeuUAA possessing τm5U (at that time it was an unknown modified uridine (U*) [24], and later it was elucidated to be τm5U [8]) in a bovine mitochondrial in vitro translation system using synthetic mRNAs possessing 30 triplet repeats for the Leu codons UUA and UUG, as well as UUC as a negative control [24, 25]. They showed clearly that wild-type tRNALeuUAA translated both poly(UUA)30 and poly(UUG)30 to poly(Leu) efficiently, but scarcely translated poly(UUU)30 or poly(UUC)30.

Kurata et al. measured the decoding activity of E. coli tRNALeuUAA possessing τm5U, cmnm5U, or unmodified U (negative control) in the anticodon wobble position which was constructed by using molecular surgery technique [26] in E. coli S30 in vitro cell-free system with synthetic oligoribonucleotides including UUN codon as messengers [27]. They clearly demonstrated that tRNALeuUAA possessing either τm5U or cmnm5U in the anticodon wobble position could translate UUA/UUG-containing messengers efficiently but could translate neither UUU- nor UUC-containing messenger. The tRNALeuUAA with unmodified U34 efficiently translated the UUA codon, but decoding of the UUG codon was approximately one third the activity of decoding UUA. However, this tRNALeuUAA could not translate either UUU or UUC in consistent with the results obtained for mitochondrial translation [28]. Thus, either τm5U- or cmnm5U-modification was proved to be essential for restricting the base-pairing to the purine-ending codons (Figures 3(a) and 3(b)).

The conformation of τm5U has not been analyzed, but it can be speculated that it is very similar to that of cmnm5U, because only their side chains at position 5 of the uridine base are different; glycine and taurine are linked to 5-methyluridine in cmnm5U and τm5U, respectively (Figure 2). As described above, the modified uridine possessing the side chain at position 5 of uridine base which is linked through a methylene group takes very rigid conformation, which enables base pair with G as well as A in the codon third position.

Mitochondrial glycyl-tRNA synthetase (GlyRS) has scarcely been studied at the molecular level. It is suggested that a tunicate (Ciona intestinalis) genome encodes single GlyRS gene responsible for synthesis of both cytoplasmic and mt GlyRSs (Yokobori et al., unpublished results). Kondow et al. elucidated that a tunicate (H. roretzi) mt tRNAGlyτm5UCU is glycylated in vivo [29]. These results strongly suggest that tunicate mt GlyRS is possible to recognize tRNAGlyτm5UCU possessing τm5U34.

2.3. f5C for Decoding AUA Codon

5-formylcytidine (f5C) occurs at the anticodon wobble position of tRNAMet of most invertebrate (fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster [12], squid, Loligo bleekeri [30], and nematode, Ascaris suum [31]), and vertebrate (bovine, Bos taurus [9]) mitochondria, where AUA codon is read as Met instead of Ile [1, 5]. However, in echinoderm [32], some platyhelminth (such as planaria), cnidarian, placozoan, and poriferan mitochondria, AUA codon is read as Ile, like universal genetic code. In the former case, it is considered that f5C34 of tRNAMet could restrict the base pair with A and G in the codon third letter (Figures 3(c) and 3(d)), but in the latter case, the wobble nucleoside of tRNAIle is G34, so that this tRNA would translate AUA codon as not Met, but Ile.

By constructing an in vitro translation system from bovine liver mitochondria, Takemoto et al. examined the decoding properties of the native mt tRNAMet carrying f5C in the anticodon compared to a transcript that lacks the modification [14]. The native mt Met-tRNAMet could recognize both AUG and AUA codons as Met, but the corresponding synthetic tRNAMet lacking f5C (anticodon CAU) recognized only the AUG codon in both the codon-dependent ribosomal binding and in vitro translation assays. Furthermore, the E. coli elongator tRNAMetm with the anticodon ac4CAU (ac4C=4-acetylcytidine) and the bovine cytoplasmic initiator tRNAMet (anticodon CAU) translated only the AUG codon for Met on mt ribosome. The codon recognition patterns of these tRNAs were the same on E. coli ribosomes. These results demonstrate that the f5C modification in mt tRNAMet plays a crucial role in decoding the nonuniversal AUA codon as Met, and that the genetic code variation is compensated by a change in the tRNA anticodon, not by a change in the ribosome.

Conformation analysis of f5C by 500-MHz NMR showed that the nucleoside takes a very rigid C3'-endo-anti form [33]. This feature may be advantageous for the decoding properties of tRNAMet, because a very rigid pyrimidine in the first position of the anticodon cannot form base pairs with U and C in the codon third position [34, 35], so that the tRNAMet cannot decode the AUU and AUC Ile codons. In addition, it is to be anticipated that the stability conferred by a rigid ribose moiety in the first anticodon nucleotide will to some extent be propagated to the second and third anticodon residues. This would result in greater overall stability of the stacked anticodon bases, and thus of codon-anticodon pairings.

It is apparent that f5C can interact in the expected manner with G of the AUG Met codon (Figure 3(d)), reflecting the finding that the conformation of f5C is similar to that of cytidine [33]. In order to read the AUA Met codon, the intriguing possibility exists that f5C pairs with A in the AUA Met codon by protonation (Figure 3(c)). The protonation of A at N-1 in an A-C pair at pH values above the pK of the monomer has been demonstrated in oligoribonucleotide duplexes [36]. In addition, A was found to adopt a pK of 6.5 in the active site of a Pb-dependent ribozyme [37].

Human mt MetRS has been studied by Spremulli's group [38]. They found that the enzyme recognizes the anticodon region of tRNAMet as an identity determinant and aminoacylates both human mt tRNAMetCAU transcript and bovine tRNAMetf5CAU with similar KM (0.15∼0.16 μM) and kcat (0.02 s−1) values. As the nucleotide sequences of human and bovine mt tRNAsMetCAU are almost identical to each other with 5 nucleotide differences at positions 16, 27, 50, 56, and 60, and it has turned out that human mt tRNAsMetCAU also possesses f5C at the anticodon wobble position [39] these kinetic data clearly demonstrate that human mt MetRS recognizes the substrate tRNAMetCAU irrespective of the presence or absence of f5C34.

2.4. m7G and Unmodified G Which Decodes AGA or AGG Codon in Most Invertebrates

AGA and AGG codons are read as Ser in most metazoan mitochondria [32]. Matsuyama et al. found that 7-methylguanosine (m7G) is present at the wobble position of tRNASerGCU in most invertebrate mitochondria [10]. Therefore, the anticodon m7GCU of tRNASerGCU is most likely responsible for reading all four AGN codons as Ser (Figures 3(e)–3(h)) [10]. On the other hand, the AGG codon is absent from some metazoan mitochondria, such as fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster mitochondria (Table 1), and the anticodon wobble position of tRNASerGCU is unmodified G [12]. In this case, the unmodified GCU anticodon of tRNASerGCU seems to read the three codons AGU, AGC, and AGA as Ser. Therefore, it is summarized that G34 of Drosophila tRNASerGCU base pairs with only U, C, and A in the third letter of Ser codon, and in most invertebrate mt tRNAsSerGCU, it is prerequisite for G34 to be modified to m7G for recognizing G in the third letter of Ser codon.

Table 1.

Relationship between the genetic code variations and modified nucleosides in the anticodon of the corresponding tRNAs in the animal phlyla.

(a) UGA codon.

| Animal phyla | UGA specificity | Anticodon |

|---|---|---|

| Vertebrata | Trp | τm5UCA(a) |

| Tunicata (Urochordata) | Trp | τm5UCA(b) |

| Cephalochordata | Trp | (TCA) |

| Echinodermata | Trp | (TCA) |

| Arthropoda | Trp | U*CA(c) |

| Most invertebrate phyla | Trp | cmnm5(s2)UCA(d) |

| Platyhelminthes | Trp | (TCA) |

| Cnidaria, Placozoa, Porifera | Trp | (TCA) |

(b) AUA codon.

| Animal phyla | AUA specificity | Anticodon |

|---|---|---|

| Vertebrata | Met | f5CAU(e) |

| Tunicata (Urochordata) | Met | τm5UAU(f) |

| Cephalochordata | Met | (CAT) |

| Echinodermata | Ile | (GAT) |

| Arthropoda | Met | f5CAU(g) |

| Most invertebrate phyla | Met | f5CAU(h, i) |

| Platyhelminthes | ||

| Most (Echinostomida, Trematoda) | Met | (CAT) |

| Rhabditiophora, Planaria | Ile | (GAT) |

| Cnidaria | Ile | —(j) |

| Placozoa | Ile | (GAT) |

| Porifera | Ile | (CAT)(k) |

(c) AAA codon.

| Animal phyla | AAA specificity | Anticodon |

|---|---|---|

| Vertebrata | Lys | (CTT) |

| Tunicata (Urochordata) | Lys | (TTT) |

| Cephalochordata | Lys | (TTT) |

| Echinodermata | Asn | GΨU(l) |

| Arthropoda | Lys | CUU(m)/(TTT) |

| Most invertebrate phyla | Lys | (CTT/TTT) |

| Platyhelminthes | Asn | (GTT) |

| Cnidaria | Lys | —(j) |

| Placozoa | Lys | (TTT) |

| Porifera | Lys | (TTT) |

(d) AGA/AGG codons.

| Animal phyla | AGA/AGG specificity | Anticodon |

|---|---|---|

| Vertebrata | Term. | None |

| Tunicata (Urochordata) | Gly | τm5UCU(n) |

| Cephalochordata | Ser | (GCT) |

| Echinodermata | Ser | m7GCU(o) |

| Arthropoda | ||

| Most Arthropods | Ser | (GCT/TCT) |

| Drosophila melanogaster | Ser(p) | GCU(q) |

| Most invertebrate phyla | Ser | m7GCU(r) |

| Platyhelminthes | Ser | (GCT/TCT) |

| Cnidaria | Arg | —(j) |

| Placozoa | Arg | (TCT) |

| Porifera | Arg | (TCT) |

In case that only the tRNA gene sequences are known, the anticodon sequences at DNA level are shown in parentheses. (a)Homo sapiens (Suzuki et al. [39]) (b)Halocynthia roretzi (Suzuki et al. [23]) (c)Drosophila melanogaster (Tomita et al. [12]). U* is an unkown modified uridine. (d)Ascaris suum (Sakurai et al. [15]) (e)Bos taurus (Moriya et al. [9]) (f)Halocynthia roretzi (Suzuki et al. [23]) (g)Drosophila melanogaster (Tomita et al. [12]) (h)Loligo bleekeri (Tomita et al. [30]) (i)Ascaris suum (Watanabe al. [31]) (j)Corresponding tRNA gene is not encoded in the mitochondrial genome. The tRNA decoding this codon is presumed to be imported from cytoplasm [40]. (k)Poriferan mt genomes encode three tRNA genes with anticodon CAT at DNA level. One of these tRNA is thought to be tRNAIleLAU gene (L is the modified C (lysidine) found at the anticodon first position of most bacterial tRNAIle decoding AUA codon) [41]. (l)Asterias amurensis (Tomita et al. [42]) (m)Drosohila melanogaster (Tomita et al. [12]) (n)Halocynthia roretzi (Kondow et al. [29], Suzuki et al. [23]) (o)Asterias amurensis (Matsuyama et al. [10]) (p)No AGG codon appears in the D. melanogaster mitochondrial genome. (q)Drosophila melanogaster (Tomita et al. [12]) (r)Loligo bleekeri (Tomita et al. [11]).

The purine-purine base pairing is well discussed by Murphy and Ramakrishnan for I-A pair [43]. They reported the crystal structure of I-C and I-A base pairs in the context of the ribosomal decoding center, clearly showing that the I-A base pair is of an Ianti -Aanti conformation, as predicted by Crick [44] although the distance between C1-C1 of I and A residues is broader than the usual one. Owing to this observation, G-A and also m7G-A base pairs in question would be possible to take a similar structure as that of I-A base pair (Figure 3(g)). Since m7G can form a structure in which a proton is cleaved from HN1 and O6 becomes O− (but G cannot form the structure), m7G-G base pair can be formed in which m7G moves to the minor groove side in the context of the ribosomal decoding center (Figure 3(h)) [45]. Such base pair stacks well on the neighboring second base pair of codon-anticodon pairing, so that the whole interaction would be stabilized [46]. This speculation must be confirmed experimentally, the simplest way of which would be to use an in vitro translation system.

The recognition mechanism of bovine mt SerRS toward tRNASer has been elucidated well by biochemical [47, 48] as well as X-ray crystallographic studies [49]. Both results clearly demonstrated that the anticodon region of tRNASer is not involved in the identity determinant for bovine mt SerRS. Thus, it can be concluded that the presence or absence of τm5U in the anticodon wobble position has no influence on the recognition of SerRS toward tRNASer.

2.5. Ψ in the Anticodon Second Position of tRNAAsnGUU Responsible for Decoding AAA Codon

In echinoderm [32] and some platyhelminth mitochondria [50], not only the usual Asn codons AAU and AAC, but also the usual Lys codon AAA, are read as Asn by a single mt tRNAAsn with the anticodon GUU. Tomita et al. elucidated that starfish mt tRNAAsn possesses the anticodon GΨU, whose second position is modified to pseudouridine (Ψ) [42]. In contrast, mt tRNALys, corresponding to another Lys codon, AAG, has the anticodon CUU. Mt tRNAs possessing anticodons closely related to that of tRNAAsn, but responsible for decoding only two codons each (tRNAHis, tRNAAsp, and tRNATyr) (see Figure 1), were found to possess unmodified U35 in all cases, suggesting the importance of Ψ35 in tRNAAsn for decoding the AAU, AAC, and AAA codons. Experiments with an E. coli in vitro translation system confirmed that tRNAAsnGΨU has about two-fold higher translational efficiency than tRNAAsnGUU [42], in which tRNAAsnGΨU was constructed by chemical synthesis and ligation, and tRNAAsnGUU was obtained by in vitro run-off transcription. It is exceptional that modification at the anticodon second nucleoside is involved in the codon-anticodon interaction efficiency.

There is a report that Ψ within the base-paired region at position 35 in a model for the codon-anticodon interaction in tRNATyr increases the Tm by several degrees [51]. This is also supporting evidence for the above-mentioned phenomenon.

3. Relationship between Modified Nucleosides and Genetic Code Variations in the Course of Animal Evolution

In considering the evolution of the genetic code, there are so far two main hypotheses, the “codon-capture” hypothesis based on directional mutation pressure proposed by Osawa and Jukes [52], and the “ambiguous intermediate” hypothesis proposed by Schultz and Yarus [53]. Codon capture hypothesis proposes temporary disappearance of a sense codon (or stop codon) from coding frames by conversion to another synonymous codon, followed by loss of the corresponding tRNA that translates the codon. (For a stop codon, the release factor (RF) must change simultaneously so as not to recognize the stop codon.) This change may be caused by directional mutation pressure acting on genome (AT or GC pressure), changes of RF, or genome economization, which will produce an “unassigned codon.” The codon reappears later by the conversion of another codon caused by directional mutation pressure and emergence of a tRNA (or RF) that translates (or recognizes) the reappeared codon with a different assignment, Thus, the codon is reassigned or captured. In the “ambiguous intermediate” hypothesis, it is presumed that reassignment of codons is facilitated by a translationally ambiguous intermediate where the transitional codon is read simultaneously as two different amino acids by two tRNAs, one cognate and the other near cognate. There has been little experimental evidence in support of the presence of these tRNAs that decode a single codon as two different amino acids simultaneously. Simulation study on codon reassignment [54]suggested that the pathway of codon reassignment in favor of either “codon capture” or “ambiguous codon” depends on the initial conditions such as genome size and number of codons in interest.

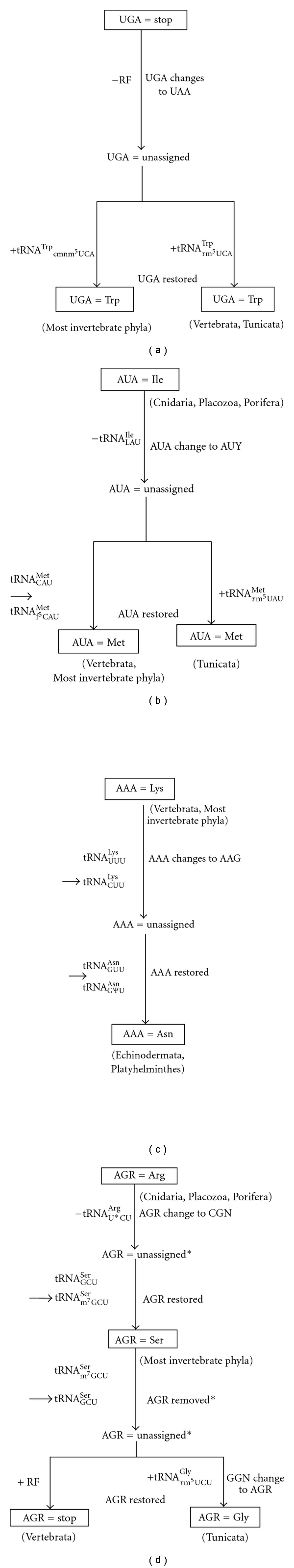

We adopt here the former hypothesis essentially to explain the genetic code variations of animal mitochondria, because the characteristics of the animal mitochondrial genome such as AT richness and genome economization would be suitable for the adoption of the codon-capture hypothesis. The hypothesis would nicely fit in explaining the UGA codon change in animal mitochondria. There has been so far no report of a release factor recognizing UGA codon [55, 56]. Such a release factor corresponding to eubacterial RF2 was probably lost in the animal mt system, so that the UGA codon became unassigned. When the anticodon wobble position of tRNATrp changed from C to modified U (U*: cmnm5(s2)U or τm5U), and a part of the Trp UGG codon in reading frames was changed to UGA by AT pressure, the UGA codon was captured by tRNATrpU*CA and read as Trp (Figure 4(a)). Why lower animals use cmnm5(s2)U for U*, whereas higher animals use τm5U instead of cmnm5(s2)U (Table 1(a)), and from which stage of animals conversion of cmnm5(s2)U to τm5U occurs remain to be clarified.

Figure 4.

Schematic drawings showing the possible evolutionary changes of UGA (a), AUA (b), AAA (c), and AGR (d) codons in animal mitochondrial genomes. * In order to exclude too complicated situations, simple formulas were adopted for the process of the possible evolutionary changes of AGR codons in this figure. For details, see Text.

To explain the evolutionary change of other nonuniversal codons in metazoan mitochondria, in addition to AT pressure, the genome economization effect (especially, that tRNA genes are restricted to 22~24 species, and that tRNAs are not imported from the cytoplasm in almost all metazoan mitochondria [7] except for a few cases in Cnidaria and so on) should be taken into consideration. At the same time, we should include the idea of competition between two different tRNAs toward a certain codon, to explain the role of modified nucleoside in the anticodon region of tRNA. Namely, any codon can be read by the corresponding tRNA, but if a competitor tRNA or a release factor arises that has stronger affinity toward the codon than does the original tRNA, the codon will then be read by the competitor.

The AUA codon is read as Ile in cnidarian, placozoan, poriferan, some platyhelminths, and echinoderm mitochondria, but it is read as Met in most metazoan mitochondria (Table 1(b)). f5C in most metazoan mitochondria [8, 9, 12, 31] and τm5U in tunicate mitochondria [23] found at the wobble position of tRNAMet may be important for understanding the codon reassignment from AUA-Ile to AUA-Met. Since the interaction between tRNAIleGAU and AUA on the ribosome might be more unstable than that between the tRNAIleGAU and AUY codons, when tRNAMet acquired the capacity to decode AUA by 5′-formylation of C or 5′-taurinometylaton of U at the wobble position, tRNAMetf5CAU or tRNAMetτm5UAU may have prevailed over tRNAIleGAU in the interaction with the AUA codon. Thus, the reassignment of Ile to Met could have easily occurred (Figure 4(b)). In echinoderm mitochondria, f5C or τm5U modification was lost in tRNAMet, so that AUA is read as Ile by tNAIleGAU because the competitor tRNA was lost. Why most metazoan tRNAsMet possess f5C modification, but only tunicates tRNAMet possess τm5U modification is also to be solved.

The AAA codon is read as Lys in most metazoan mitochondria, but only in some platyhelminth and echinoderm mitochondria is read as Asn (Table 1(c)). In this case, pseudouridylation at the second position of the anticodon of tRNAAsn [42] was critical for the codon reassignment (Figure 4(c)). The interaction between tRNAAsnGΨU and AAA may have prevailed over that between tRNALysUUU or tRNALysCUU (in various metazoan mitochondria such as those of echinoderms and fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster) and AAA. It is interesting observation that echinoderm and a part of platyhelminth mitochondria use AUA as a universal Ile codon and AAA as a nonuniversal Asn codon, while all the other animal mitochondria use AUA as a nonuniversal Met codon, and AAA as a universal Lys codon. This should be clarified in the relationship between genetic code change and animal evolution.

AGR codons are used as Ser codons in most invertebrate mitochondria, Gly codons in tunicate mitochondria and termination codons in vertebrate mitochondria (Table 1(d)). The scenario for this codon change would be as follows (Figure 4(d)). In the evolutionary process from Cnidaria, Placozoa, and Porifera to higher invertebrates, tRNAArgU*CU to decode AGR codons as Arg disappeared from the mt genome, because of the reduction in genome size (in Cnidaria, most of tRNA genes are absent from the mt genome and most tRNAs are thought to be imported from the cytoplasm [40], but, in most higher animal mitochondria, import of tRNA has not been reported [7]). This has created a situation in which AGR codons cannot be translated. Since the AGR-Arg sites in the mitochondrial genomes of Protista such as Trypanosoma are mostly replaced with CGN-Arg codons and partially by a few other codons throughout metazoan mitochondria [57], AGR codons were converted mainly to CGN upon the deletion of tRNAArgU*CU, so that AGR codons became unassigned (first step). Once the anticodon wobble position (G34) of tRNASerGCU was modified to m7G, all four AGN codons became ready to be decoded as Ser [10, 11]. AGR codons pairing with this tRNASerm7GCU then appeared in reading frames because of the mutation of AGY-Ser codons or other codons to AGR codons, and they were captured by Ser (second step). In ancestors of tunicates and vertebrates, demethylation of m7G of mt tRNASerm7GCU may have occurred, so the resulting mt tRNASerGCU no longer reads the AGG codon. Strong selective constraints resulting from the lost translation of AGG caused the AGG codon to change mainly to AGY or other codons, so that the AGG codon became unassigned (third step). After tunicates were separated from vertebrate ancestors, a fourth event may have occurred; the mt tRNAGlyUCC gene was duplicated in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) (in fact, the ascidian mt genome has two tRNAGly genes [58]), and the anticodon of one species of tRNAGlyUCC was converted from TCC to TCT because of AT pressure, resulting in tRNAGlyUCU, which might have occurred in tunicate mt genomes. Then, the anticodon wobble position of tRNAGlyUCU must have been modified to τm5U (tRNAGlyτm5UCU; ([8, 23]) so as to decode AGR codons. At the same time, AT pressure caused GGN codons to change to AGR codons. Since the interaction of tRNAGlyτm5UCU with AGR is stronger than that of tRNASerGCU with AGR, AGR codons are captured by tRNAGlyτm5UCU, resulting in the translation of AGR codons as Gly [59]. The low GC content of the cytochrome oxydase subunit I region in ascidian (tunicate) mitochondria in comparison to that of vertebrates is consistent with the speculation that AT pressure occurred on the tunicate mt genome. In the ancestors of vertebrate mitochondria, AGR codons may have appeared in the reading frames by the deletion of U from the UAG termination codon [57], concomitantly with a functional change in the vertebrate RF so as to recognize AGR codons (a possible candidate for an mt RF capable of recognizing AGR codons was reported [56]). The RF prevails over tRNASerGCU in decoding the AGA codon and, thus, changes AGR codons to termination codons (Figure 4(d)) [57]. Why m7G- and τm5U-modifications have become to be used in most metazoan and tunicate mitochondria, respectively, for decoding AGR codons are intriguing problems, which should be pursued in future.

4. Conclusion

The concept of the universal genetic code was forced to change since the discovery of nonuniversal codon in human mitochondria [4, 5], and it was known that not only mitochondria but also usual cellular systems (nuclear genomes) contain the nonuniversal genetic codes [60]. Nowadays, it is widely accepted that the genetic code is not universal but is changeable depending on the lineage of organisms [61]. Especially, it should be mentioned that animal mt genomes contain several variations in the genetic code, and the nonuniversal genetic codes are decoded by tRNAs which possess modified nucleosides in their anticodon first or second positions.

In animal mt genetic code, variations occur only in the 2 codon boxes where one family box is divided 2 : 2 (which may be easily understandable), and only purine-ending codon(s) are the target for codon reassignment (Figure 1). The questions may arise as to why no codon changes has occurred in two codon boxes of His(CAY)-Gln(CAR) and/or Asp(GAY)-Glu(GAR) and why pyrimidine-ending codon(s) (NNY) do not become the target for codon reassignment. For the former question, such cases may be found in future [61] and for the latter question, it may be because it is difficult to provide any modified nucleoside in the tRNA anticodon wobble position which can decode purine-ending codons (NNR) and one or both of pyrimidine-ending codons (NNY).

The way of codon-anticodon interaction in the decoding process of the nonuniversal genetic code follows the base-pairing rule based on the physiochemical property of nucleosides. It is the future problems to be answered why various modified nucleosides such as cmnm5(s2)U, τm5U, f5C, m7G, and Ψ have been selected as the key molecules for decoding the nonuniversal genetic code and how these modified nucleosides have been distributed among various animal mitochondria.

The genetic code consists of interaction between codon and anticodon of tRNA, and inspections of genetic code changes in animal mitochondria in which considerable number of changes occur in various animal lineages will lead to the elucidation of the basic principle of origin and evolution of the genetic code. It is expected that these studies will shed light on a way to approach the origin of life.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Professors Hiroyuki Hori and Kazuyuki Takai, Faculty of Engineering, Ehime University, Japan, for their kind instruction and discussion on the base-pairing property of m7G. This work was supported by grants in aid for scientific research (C) from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS).

References

- 1.Watanabe K. Unique features of animal mitochondrial translation systems: the non-universal genetic code, unusual features of the translational apparatus and their relevance to human mitochondrial diseases. Proceedings of the Japan Academy B. 2010;86(1):11–39. doi: 10.2183/pjab.86.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bessho Y, Ohama T, Osawa S. Planarian mitochondria II. The unique genetic code as deduced from cytochrome c oxydase subunit I gene sequence. Journal of Molecular Evolution. 1992;34(4):331–335. doi: 10.1007/BF00160240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacob JEM, Vanholme B, Van Leeuwen T, Gheysen G. A unique genetic code change in the mitochondrial genome of the parasitic nematode Radopholus similis. BMC Research Notes. 2009;2, article 192 doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-2-192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barrell BG, Bankier AT, Drouin J. A different genetic code in human mitochondria. Nature. 1979;282:189–194. doi: 10.1038/282189a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson S, Bankier AT, Barrell BG, et al. Sequence and organization of the human mitochondrial genome. Nature. 1981;290(5806):457–465. doi: 10.1038/290457a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watanabe K, Osawa S. tRNA sequences and variations in the genetic code. In: Söll D, RajBhandary UL, editors. tRNA: Structure, Biosynthesis and Function. Washington, DC, USA: ASM Press; 1995. pp. 215–250. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roe BA, Wong JFH, Chen EY, Armstrong PA. Sequence analysis of mammalian mitochondrial tRNAs.. In: Walton AG, editor. In: Recombinant DNA: Proceedings of the 3rd Cleveland Symposium on Macromolecules; June 1981; Cleveland, Ohio, USA. Elsevier; pp. 167–176. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suzuki T, Suzuki T, Wada T, Saigo K, Watanabe K. Taurine as a constituent of mitochondrial tRNAs: new insights into the functions of taurine and human mitochondrial diseases. The EMBO Journal. 2002;21(23):6581–6589. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moriya J, Yokogawa T, Wakita K, et al. A novel modified nucleoside found at the first position of the anticodon of methionine tRNA from bovine liver mitochondria. Biochemistry. 1994;33(8):2234–2239. doi: 10.1021/bi00174a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsuyama S, Ueda T, Crain PF, McCloskey JA, Watanabe K. A novel wobble rule found in starfish mitochondria. Presence of 7-methylguanosine at the anticodon wobble position expands decoding capability of tRNA. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273(6):3363–3368. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.6.3363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tomita K, Ueda T, Watanabe K. 7-Methylguanosine at the anticodon wobble position of squid mitochondrial tRNASerGCU: molecular basis for assignment of AGA/AGG codons as serine in invertebrate mitochondria. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1998;1399(1):78–82. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(98)00099-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tomita K, Ueda T, Ishiwa S, Crain PF, McCloskey JA, Watanabe K. Codon reading patterns in Drosophila melanogaster mitochondria based on their tRNA sequences: a unique wobble rule in animal mitochondria. Nucleic Acids Research. 1999;27(21):4291–4297. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.21.4291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanada T, Suzuki T, Yokogawa T, Takemoto-Hori C, Sprinzl M, Watanabe K. Translation ability of mitochondrial tRNAsSer with unusual secondary structures in an in vitro translation system of bovine mitochondria. Genes to Cells. 2001;6(12):1019–1030. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2001.00491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takemoto C, Spremulli LL, Benkowski LA, Ueda T, Yokogawa T, Watanabe K. Unconventional decoding of the AUA codon as methionine by mitochondrial tRNAMet with the anticodon f5CAU as revealed with a mitochondrial in vitro translation system. Nucleic Acids Research. 2009;37(5):1616–1627. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sakurai M, Ohtsuki T, Suzuki T, Watanabe K. Unusual usage of wobble modifications in mitochondrial tRNAs of the nematode Ascaris suum. FEBS Letters. 2005;579(13):2767–2772. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sakurai M, Ohtsuki T, Watanabe K. Modification at position 9 with 1-methyladenosine is crucial for structure and function of nematode mitochondrial tRNAs lacking the entire T-arm. Nucleic Acids Research. 2005;33(5):1653–1661. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andachi Y, Yamao F, Muto A, Osawa S. Codon recognition patterns as deduced from sequences of the complete set of transfer RNA species in Mycoplasma capricolum: resemblance to mitochondria. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1989;209(1):37–54. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90168-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin RP, Sibler A-P, Gehrke CW, et al. 5-[[(Carboxymethyl)amino]methyl]uridine is found in the anticodon of yeast mitochondrial tRNAs recognizing two-codon families ending in a purine. Biochemistry. 1990;29(4):956–959. doi: 10.1021/bi00456a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sekine M, Peshakova LS, Hata T, Yokoyama S, Miyazawa T. Novel method for regioselective 2’-O-methylation and its application to the synthesis of 2’-O-methyl-5-[[(carboxymethyl)- amino]methyl]uridine. Journal of Organic Chemistry. 1987;52(22):5060–5061. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takai K, Horie N, Yamaizumi Z, Nishimura S, Miyazawa T, Yokoyama S. Recognition of UUN codons by two leucine tRNA species from Escherichia coli. FEBS Letters. 1994;344(1):31–34. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00354-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horie N, Yamaizumi Z, Kuchino Y, et al. Modified nucleosides in the first positions of the anticodons of tRNA4Leu and tRNA5Leu from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1999;38(1):207–217. doi: 10.1021/bi981865g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yokoyama S, Nishimura S. Modified nucleosides and codon reognition. In: Söll D, RajBhandary UL, editors. tRNA: Structure, Biosynthesis and Function. Washington, DC, USA: ASM Press; 1995. pp. 207–223. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suzuki T, Miyauchi K, Suzuki T, et al. Taurine-containing uridine modifications in tRNA anticodons are required to decipher non-universal genetic codes in ascidian mitochondria. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011;286(41):35494–35498. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.279810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yasukawa T, Suzuki T, Ohta S, Watanabe K. Wobble modification defect suppresses translational activity of tRNAs with MERRF and MELAS mutations. Mitochondrion. 2002;2(1-2):129–141. doi: 10.1016/s1567-7249(02)00033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yasukawa T, Suzuki T, Ishii N, Ohta S, Watanabe K. Wobble modification defect in tRNA disturbs codon-anticodon interaction in a mitochondrial disease. The EMBO Journal. 2001;20(17):4794–4802. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.17.4794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suzuki T, Ueda T, Watanabe K. The “polysemous” codon—a codon with multiple amino acid assignment caused by dual specificity of tRNA identity. The EMBO Journal. 1997;16(5):1122–1134. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.5.1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kurata S, Weixlbaumer A, Ohtsuki T, et al. Modified uridines with C5-methylene substituents at the first position of the tRNA anticodon stabilize U·G wobble pairing during decoding. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283(27):18801–18811. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800233200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kirino Y, Yasukawa T, Ohta S, et al. Codon-specific translational defect caused by a wobble modification deficiency in mutant tRNA from a human mitochondrial disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101(42):15070–15075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405173101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kondow A, Suzuki T, Yokobori S, Ueda T, Watanabe K. An extra tRNAGly(U∗CU) found in ascidian mitochondria responsible for decoding non-universal codons AGA/AGG as glycine. Nucleic Acids Research. 1999;27(12):2554–2559. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.12.2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tomita K, Ueda T, Watanabe K. 5-formylcytidine (f5C) found at the wobble position of the anticodon of squid mitochondrial tRNAMetCAU. Nucleic Acids Symposium Series. 1997;(37):197–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watanabe Y, Tsurui H, Ueda T, et al. Primary and higher order structures of nematode (Ascaris suum) mitochondrial tRNAs lacking either the T or D stem. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269(36):22902–22906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Himeno H, Masaki H, Kawai T, et al. Unusual genetic codes and a novel gene structure for tRNASerAGY in starfish mitochondrial DNA. Gene. 1987;56(2-3):219–230. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90139-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kawai G, Yokogawa T, Nishikawa K, et al. Conformational properties of a novel modified nucleoside, 5-formylcytidine, found at the first position of the anticodon of bovine mitochondrial tRNAMet. Nucleosides and Nucleotides. 1994;13(5):1189–1199. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yokoyama S, Watanabe T, Murao K, et al. Molecular mechanism of codon recognition by tRNA species with modified uridine in the first position of the anticodon. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1985;82(15):4905–4909. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.15.4905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kawai G, Hashizume T, Yasuda M, Miyazawa T, McCloskey JA, Yokoyama S. Conformational rigidity of N4-acetyl-2’-O-methylcytidine found in tRNA of extremely thermophilic archaebacteria (Archaea) Nucleosides and Nucleotides. 1992;11(2–4):759–771. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang S, Gao H, Gaffney BL, Jones RA. Nitrogen-15-labeled oligodeoxynucleotides. 3. Protonation of the adenine N1 in the A·C and A·G mispairs of the duplexes {d[CG(15N1)AGAATTCCCG]}2 and {d[CGGGAATTC(15N1)ACG]}2. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1991;113(14):5486–5489. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Canny MD, Jucker FM, Kellogg E, Khvorova A, Jayasena SD, Pardi A. Fast cleavage kinetics of a natural hammerhead ribozyme. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2004;126(35):10848–10849. doi: 10.1021/ja046848v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spencer AC, Heck A, Takeuchi N, Watanabe K, Spremulli LL. Characterization of the human mitochondrial methionyl-tRNA synthetase. Biochemistry. 2004;43(30):9743–9754. doi: 10.1021/bi049639w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suzuki T, Nagano A, Suzuki T. Human mitochondrial diseases caused by lack of taurine modification in mitochondrial tRNAs. WIREs RNA. 2011;2(3):376–386. doi: 10.1002/wrna.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beagley CT, Okimoto R, Wolstenholme DR. The mitochondrial genome of the sea anemone Metridium senile (Cnidaria): introns, a paucity of tRNA genes, and a near-standard genetic code. Genetics. 1998;148(3):1091–1108. doi: 10.1093/genetics/148.3.1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lavrov DV, Forget L, Kelly M, Lang BF. Mitochondrial genomes of two demosponges provide insights into an early stage of animal evolution. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2005;22(5):1231–1239. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tomita K, Ueda T, Watanabe K. The presence of pseudouridine in the anticodon alters the genetic code: a possible mechanism for assignment of the AAA lysine codon as asparagine in echinoderm mitochondria. Nucleic Acids Research. 1999;27(7):1683–1689. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.7.1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murphy FV, IV, Ramakrishnan V. Structure of a purine-purine wobble base pair in the decoding center of the ribosome. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 2004;11(12):1251–1252. doi: 10.1038/nsmb866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Crick FHC. Codon-anticodon pairing: the wobble hypothesis. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1966;19(2):548–555. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(66)80022-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takai K. Classification of the possible pairs between the first anticodon and the third codon positions based on a simple model assuming two geometries with which the pairing effectively potentiates the decoding complex. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 2006;242:564–580. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mizuno H, Sundaralingam M. Stacking of Crick Wobble pair and Watson-Crick pair: stability rules of G-U pairs at ends of helical stems in tRNAs and the relation to codon-anticodon Wobble interaction. Nucleic Acids Research. 1978;5(11):4451–4461. doi: 10.1093/nar/5.11.4451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yokogawa T, Shimada N, Takeuchi N, et al. Characterization and tRNA recognition of mammalian mitochondrial seryl-tRNA synthetase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(26):19913–19920. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M908473199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shimada N, Suzuki T, Watanabe K. Dual mode recognition of two isoacceptor tRNAs by mammalian mitochondrial seryl-tRNA synthetase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(50):46770–46778. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105150200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chimnaronk S, Jeppesen MG, Suzuki T, Nyborg J, Watanabe K. Dual-mode recognition of noncanonical tRNAsSer by seryl-tRNA synthetase in mammalian mitochondria. The EMBO Journal. 2005;24(19):3369–3379. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Telford MJ, Herniou EA, Russell RB, Littlewood DTJ. Changes in mitochondrial genetic codes as phylogenetic characters: two examples from the flatworms. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97(21):11359–11364. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.21.11359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Davis DR. Biophysical and conformational properties of modified nucleosides in RNA(nuclear magnetic resonance studies) In: Grosjean H, Benne R, editors. Modification and Editing of RNA. Washington, DC, USA: ASM Press; 1998. pp. 103–112. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Osawa S, Jukes TH. Codon reassignment (codon capture) in evolution. Journal of Molecular Evolution. 1989;28(4):271–278. doi: 10.1007/BF02103422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schultz DW, Yarus M. Transfer RNA mutation and the malleability of the genetic code. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1994;235(5):1377–1380. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sengupta S, Yang X, Higgs PG. The mechanisms of codon reassignments in mitochondrial genetic codes. Journal of Molecular Evolution. 2007;64(6):662–688. doi: 10.1007/s00239-006-0284-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee CC, Timms KM, Trotman CNA, Tate WP. Isolation of a rat mitochondrial release factor. Accommodation of the changed genetic code for termination. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1987;262(8):3548–3552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Soleimanpour-Lichaei HR, Kuhl I, Gaisne M, et al. mtRF1a is a human mitochondrial translation release factor decoding the major termination codons UAA and UAG. Molecular Cell. 2007;27(5):745–757. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Osawa S, Ohama T, Jukes TH, Watanabe K. Evolution of the mitochondrial genetic code I. Origin of AGR serine and stop codons in metazoan mitochondria. Journal of Molecular Evolution. 1989;29(3):202–207. doi: 10.1007/BF02100203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yokobori S, Ueda T, Feldmaier-Fuchs G, et al. Complete DNA sequence of the mitochondrial genome of the ascidian Halocynthia roretzi (Chordata, Urochordata) Genetics. 1999;153(4):1851–1862. doi: 10.1093/genetics/153.4.1851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yokobori S, Ueda T, Watanabe K. Codons AGA and AGG are read as glycine in ascidian mitochondria. Journal of Molecular Evolution. 1993;36(1):1–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02407301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yamao F, Muto A, Kawaguchi Y, et al. UGA is read as tryptophan tRNAs in Mycoplasma capricolum. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1985;82(8):2306–2309. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.8.2306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Osawa S. Evolution of the Genetic Code. New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]