Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

An elevated lipid content within skeletal muscle cells is associated with the development of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes mellitus. We hypothesised that in subjects with type 2 diabetes muscle malonyl-CoA (an inhibitor of fatty acid oxidation) would be elevated at baseline in comparison with control subjects and in particular during physiological hyperinsulinaemia with hyperglycaemia. Thus, fatty acids taken up by muscle would be shunted away from oxidation and towards storage (non-oxidative disposal).

Materials and methods

Six control subjects and six subjects with type 2 diabetes were studied after an overnight fast and during a hyperinsulinaemic (0.5 mU kg−1 min−1), hyperglycaemic clamp (with concurrent intra-lipid and heparin infusions) designed to increase muscle malonyl-CoA and inhibit fat oxidation. We used stable isotope methods, femoral arterial and venous catheterisation, and performed muscle biopsies to measure palmitate kinetics across the leg and muscle malonyl-CoA.

Results

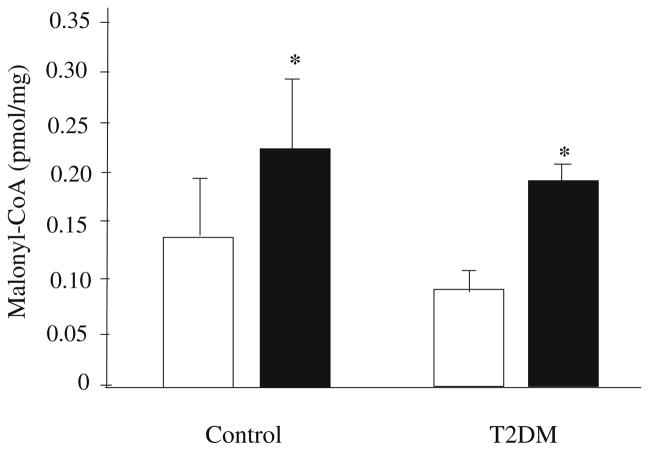

Basal muscle malonyl-CoA concentrations were similar in control and type 2 diabetic subjects and increased (p<0.05) in both groups during the clamp (control, 0.14± 0.05 to 0.24±0.05 pmol/mg; type 2 diabetes, 0.09±0.01 to 0.20±0.02 pmol/mg). Basal palmitate oxidation across the leg was not different between groups at baseline and decreased in both groups during the clamp (p<0.05). Palmitate uptake and non-oxidative disposal were significantly greater in the type 2 diabetic subjects at baseline and during the clamp (p<0.05).

Conclusions/interpretation

Contrary to our hypothesis, the dysregulation of muscle fatty acid metabolism in type 2 diabetes is independent of muscle malonyl-CoA. However, elevated fatty acid uptake in type 2 diabetes may be a key contributing factor to the increase in fatty acids being shunted towards storage within muscle.

Keywords: Fatty acid uptake, Malonyl-CoA, Muscle fatty acid oxidation, Type 2 diabetes

Introduction

The increased prevalence of obesity and insulin resistance is associated with a greater risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus [1]. Although a specific mechanism remains unclear, recent evidence suggests that elevated levels of plasma fatty acids result in a reduction in glucose uptake across the leg [2] and may further lead to the development of insulin resistance [3, 4]. In addition, obesity and type 2 diabetes are associated with metabolic alterations, such as elevated plasma fatty acids [5] and a reduced ability of insulin to suppress lipolysis [6], which lead to the accumulation of intramyocellular lipid [7–9]. This accumulation of lipid within muscle cells has been linked to the development of insulin resistance [3, 10–13]. It has been proposed that elevations in fatty acyl-CoAs can lead to increased intracellular diacylglycerol and ceramide concentrations, which in turn results in the activation of protein kinase C and the subsequent inhibition of insulin receptor tyrosine kinase activity [11, 14–17].

The accumulation of lipids can be achieved either by increased delivery to and uptake of fatty acids by muscle cells and/or by a reduction in fatty acid oxidation. An increase in malonyl-CoA, an allosteric inhibitor of carnitine palmitoyl transferase-1 (CPT-1), blocks the entry of long-chain fatty acyl-CoA into the mitochondria and thus reduces oxidation [18]. We have previously reported a significant increase in the concentration of muscle malonyl-CoA, inhibition of functional CPT-1 activity and fat oxidation, and the partitioning of fatty acids away from oxidation and towards intramuscular esterification following exposure to physiological hyperinsulinaemia with hyperglycaemia in young subjects [19].

On the other hand, recent reports have shown that fatty acid uptake into the muscle of patients with type 2 diabetes is significantly elevated in the postprandial state [20] and that the transport of long-chain fatty acids into giant sarcolemmal vesicles, prepared from obese and type 2 diabetic human skeletal muscle, is increased nearly four-fold [21]. Thus, measuring fatty acid kinetics across the leg in conjunction with measurement of intracellular regulators of fat oxidation (malonyl-CoA) in subjects with type 2 diabetes should help elucidate whether uptake or oxidation plays a predominant role in the accumulation of lipids within muscle.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to test the hypothesis that, at baseline and particularly during physiological hyperglycaemia with hyperinsulinaemia, elevated muscle malonyl-CoA concentrations in type 2 diabetes as compared with control subjects decreases the oxidation of fatty acids in skeletal muscle, thus increasing the availability of fatty acids for shunting towards storage.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

We recruited 12 subjects (nine men and three women) for the study. The characteristics of the subjects are shown in Table 1. Each control subject (n=6) was screened and given an OGTT at the University of Southern California General Clinical Research Center. Patients with type 2 diabetes were eligible for participation if either fasting blood glucose was ≥7.0 mmol/l and/or 2 h blood glucose was ≥11.1 mmol/l following the OGTT and they were on diet treatment alone. The non-diabetic control group and the subjects with type 2 diabetes were sedentary and not participating in any regular exercise programme. They were also closely matched for age, weight and BMI. Controls had a normal OGTT response and all subjects refrained from exercise for at least 24 h before study participation. Prior to participation, all subjects gave written informed consent. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Southern California. The homeostasis model assessment for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was calculated from basal glucose and insulin concentrations as: insulin (mU/l) × glucose (mmol/l)/22.5 [22].

Table 1.

Subject characteristics

| Control (n=6) | T2DM (n=6) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 35±3 | 40±4 |

| Height (m) | 1.70±0.06 | 1.62±0.04 |

| Weight (kg) | 81±6 | 79±6 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27±1 | 30±3 |

| Fat-free mass (kg) | 59±4 | 52±5 |

| Total body fat (%) | 23±1 | 28±2a |

| Leg fat mass (kg) | 2.8±0.3 | 3.6±0.8 |

| Leg fat (%) | 21±1 | 28±2 |

| Leg fat-free mass (kg) | 9.5±0.7 | 8.3±0.9 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/l) | 5.3±0.2 | 4.7±0.3 |

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/l) | 1.3±0.2 | 1.4±0.2 |

| LDL cholesterol (mmol/l) | 3.2±0.2 | 2.4±0.5 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/l) | 3.6±0.7 | 4.4±1.3 |

| HbA1c (%) | ND | 8.7±1.5 |

| HOMA-IR | 1.3±0.31 | 3.7±0.64a |

Values are mean±SEM

T2DM Type 2 diabetes mellitus, ND not determined

Significantly different from controls (p<0.05)

Study protocol

Prior to the study (72 h), the U-13C-palmitate tracer (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Andover, MA, USA) was bound to 5% human albumin with a concentration of approximately 2 μmol/ml. A sample (5 ml) of the tracer was then cultured in the clinical microbiology laboratory at the University of Southern California to check for the presence of bacterial growth prior to infusion. Following admission to the General Clinical Research Center (the evening before the study), subjects were given a dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry scan (QDR 4500W; Hologic, Bedford, MA, USA) to measure body composition and consumed a standardised meal (10 kcal/kg of body weight), after which only ad libitum water was allowed until the end of the experiment.

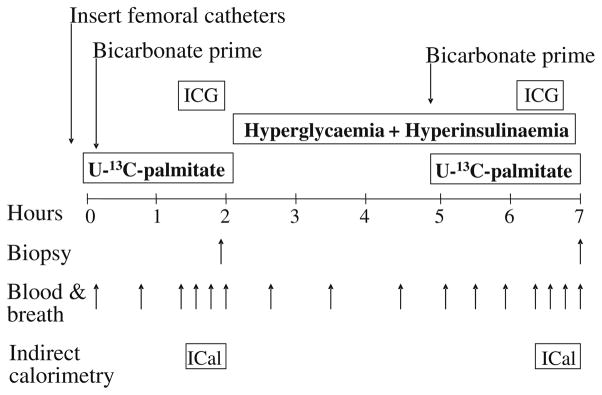

The study began the next morning with the insertion of femoral arterial and venous polyethylene catheters in the leg. The study protocol is shown in Fig. 1. The arterial catheter was also used for the infusion of indocyanine green (Akorn, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA) to measure blood flow. Additional catheters were placed in the forearm vein for systemic isotope infusion and in a contralateral wrist vein, which was heated in order to obtain arterialised blood samples. Background blood and breath samples were obtained, and a 13C-bicarbonate prime of 3 μmol/kg (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Andover, MA, USA) followed by a continuous infusion of U-13C-palmitate (0.04 μmol kg−1 min−1) was initiated (time=0). In addition, open-circuit indirect calorimetry was also used under steady-state conditions to measure the mean volumes of oxygen consumed and carbon dioxide produced over a period of 20–30 min to determine whole-body fat and glucose oxidation. Eighty minutes after the tracer infusion was initiated, an infusion of indocyanine green was initiated to measure blood flow, and four breath and blood samples were obtained at 10-min intervals (approximately 90, 100, 110 and 120 min). To prevent in vitro lipolysis, blood was collected in tubes containing 0.4 mmol/l K3-EDTA. At 120 min, using a 5-mm Bergström biopsy needle (Stille, Stockholm, Sweden), a first skeletal muscle biopsy was taken from the lateral portion of the vastus lateralis muscle, about 20 cm above the knee, using local anaesthesia with 1% lidocaine injected subcutaneously and on the fascia. The muscle sample (125–375 mg) was immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen (i.e. within seconds) and stored at −80°C until analysis.

Fig. 1.

Study design. A basal period was followed by a hyperglycaemic–hyperinsulinaemic clamp. ICG Indocyanine green, ICal indirect calorimetry

Immediately after the first skeletal muscle biopsy, the stable isotope infusion was stopped and a 5-h hyperglycaemic–hyperinsulinaemic clamp was initiated. Plasma insulin concentrations were elevated with a systemic insulin infusion (0.5 mU kg−1 min−1) into the forearm vein, and blood samples (0.5 ml) were taken every 5–10 min to monitor the plasma glucose concentration. A 20% dextrose infusion was also initiated and varied to increase glucose concentration by approximately 2.2 mmol/l above baseline and clamp it at the new concentration until the end of the experiment in both groups. During the infusion period, Intralipid (0.7 ml kg−1 min−1) and heparin (7 U kg−1 h−1) (Baxter, Deerfield, IL, USA) were also infused to prevent the expected decrease in plasma NEFA. The primary rationale for performing the physiological hyperglycaemic-hyperinsulaemic clamp was to increase malonyl-CoA to a similar extent in both groups and to inhibit oxidation of muscle fatty acids. Therefore, both groups were exposed to hyperglycaemia (relative to their baseline value). We have shown previously that this type of clamp significantly increases muscle malonyl-CoA concentrations [19].

Three hours after the beginning of the clamp (time=300 min), a new background femoral blood sample was collected to account for residual palmitate enrichments and the tracer infusion was restarted. Infusion of indo-cyanine green was restarted at 380 min, indirect calorimetry measures were taken, and breath and blood samples were obtained at 390, 400, 410 and 420 min. A final skeletal muscle biopsy was obtained at 420 min.

Isotope analysis

Assessment of plasma arterial and venous palmitate enrichment was determined using the CH3/solid phase extraction method detailed elsewhere [23] and measured using a gas chromatograph-mass spectrometer (6890 Plus GC, 5973N MSD/DS, 7683 autosampler; Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) and by selectively monitoring the ion mass:charge ratio of 272 and 256 [24]. Palmitate concentrations were determined using the external standard approach as detailed elsewhere [24]. To assess whether the dextrose infusion induced significant changes in plasma glucose enrichment, we measured plasma glucose enrichment on its pentaacetate derivative using a gas chromatograph-mass spectrometer as described previously, monitoring m/z 200 and 201 [25]. We measured the enrichment of the first isotopomer (ratio between the m/z 201/200) because any significant changes in glucose enrichment would be reflected mainly by changes in the most abundant isotopomer.

Breath collection bags were used to collect breath samples for the determination of 13CO2 enrichment. Approximately 10 ml of expired air was injected into evacuated tubes for analysis of breath enrichment (atom percentage excess) using a gas chromatograph-combustion isotope ratio mass spectrometer (Finnigan Delta Plus; Finnigan MAT, Bremen, Germany). Blood 13CO2 analysis was performed by injecting 0.5 ml of blood into an evacuated tube containing ~5 μl of 85% phosphoric acid. The liberated 13CO2 in the tube head space was used to measure the enrichment (atom percentage excess).

Kinetic calculations

Whole-body fat and glucose oxidation were calculated from indirect calorimetry data as detailed elsewhere [24, 26]. Triglyceride oxidation was determined by converting fat oxidation to its molar equivalent and multiplying the molar rate of triglyceride oxidation by 3 because each triglyceride molecule is composed of three fatty acids.

The equations used to calculate the fatty acid kinetics across the leg were adapted from Wolfe [24] and Sacchetti et al. [27] and are detailed below:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

In the above, EA and EV are the enrichments of labelled palmitate in the femoral artery and vein respectively, and CA and CV are the concentrations of palmitate in the femoral artery and vein respectively; PF is plasma flow and BF is blood flow across the leg; CaCO2 and CvCO2 are the concentrations of carbon dioxide in the femoral artery and vein respectively, and EvCO2 and EaCO2 are the enrichments of carbon dioxide in the femoral artery and vein, respectively. An acetate correction factor (acf) was used in order to properly account for the fractional recovery of label across the leg [28].

Assays

Measurement of skeletal muscle malonyl-CoA is detailed elsewhere [29, 30] and was modified for human skeletal muscle as described previously [19]. Briefly, all muscle tissue biopsies obtained from the vastus lateralis muscle were immediately frozen (within 5 s of collection) in liquid nitrogen and stored in a freezer at −80° (under liquid nitrogen) until analysed the following morning. Upon analysis, muscle tissue was ground in a freezer at −20° under liquid nitrogen, weighed (132±12 mg), and homogenised in a solution of 6% perchloric acid. The neutralised perchloric acid was added to tritium-labelled acetyl-CoA to measure malonyl-CoA-dependent incorporation of labelled acetyl-CoA into palmitic acid (catalysed by fatty acid synthase) [31].

Insulin concentrations were measured with a commercial radioimmunoassay kit (Diagnostic Products, Los Angeles, CA, USA). Plasma glucose was determined by the glucose oxidase method using a YSI 2700 analyser (Yellow Springs Instruments, Yellow Springs, OH, USA), immediately after each blood draw. Plasma NEFA concentration was determined enzymatically (Wako NEFA; Wako Chemicals, Neuss, Germany). To determine leg blood flow, serum samples were analysed in a spectrophotometer (805 nm) following a continuous infusion of indocyanine green [32, 33]. Glucose uptake across the leg was determined by calculating the product of blood flow and the arterial-venous difference in glucose.

Statistical analysis

All values are expressed as mean±SE. Comparisons between groups at baseline were performed using Student’s t-test and comparisons with the treatment period were performed using analysis of variance with repeated measures, the effects being subject, group (control subjects, subjects with type 2 diabetes) and time (basal, clamp) using JMP statistical software version 4.0.5 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Post hoc testing was performed using Student’s t-test when appropriate. Significance was accepted at p≤0.05.

Results

Subject characteristics

The controls and subjects with type 2 diabetes were matched for age and BMI (Table 1). Although total body fat was significantly greater in the group with type 2 diabetes, no significant differences were observed in body composition across the leg (Table 1). Insulin resistance, as measured by HOMA-IR, was significantly higher in the type 2 diabetes (p<0.05) (Table 1).

Blood and breath enrichments

Blood and breath enrichments are reported in Table 2. Plasma palmitate enrichments were at steady state with no differences between groups. Whole-blood 13CO2 enrichments were not different between groups and decreased significantly to a similar extent during the clamp in the two groups (p<0.05). During the clamp, femoral arterial 13CO2 enrichment was significantly reduced (p<0.05) to a similar extent in the two groups. Basal breath 13CO2 enrichment was not different between groups, and was significantly reduced to a similar extent during the clamp. Glucose enrichment was not different between groups at baseline and did not change with dextrose infusion in either group.

Table 2.

13C Glucose, palmitate and CO2 enrichments

| 13C enrichments (%) | Basal

|

Clamp

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | T2DM | Control | T2DM | |

| Femoral arterial glucose | 10.6±0.1 | 10.9±0.1 | 10.9±0.2 | 10.8±0.1 |

| Femoral arterial palmitate | 2.1±0.3 | 2.0±0.2 | 1.6±0.3 | 1.8±0.2 |

| Femoral venous palmitate | 1.4±0.2 | 1.2±0.1 | 1.0±0.1 | 1.1±0.1 |

| Femoral arterial CO2 | 0.038±0.005 | 0.044±0.003 | 0.013±0.002a | 0.014±0.003a |

| Femoral venous CO2 | 0.036±0.004 | 0.041±0.003 | 0.012±0.002a | 0.013±0.003a |

| Breath CO2 | 0.043±0.005 | 0.049±0.003 | 0.014±0.003a | 0.018±0.003a |

Enrichments for 13C palmitate and glucose are the tracer-to-tracee ratio and atom percentage excess for CO2; values are mean±SEM

T2DM Type 2 diabetes mellitus

Significantly different from basal values (p<0.05)

Substrate and palmitate kinetics

Glucose and insulin data are shown in Table 3. Arterial glucose concentrations were significantly higher in subjects with type 2 diabetes at baseline and during the clamp (group effect; p=0.02). Basal NEFA and insulin concentrations were significantly higher in type 2 diabetic patients (p<0.05). During the clamp, arterial glucose, plasma NEFA and insulin increased significantly in both groups, but plasma insulin was significantly lower in subjects with type 2 diabetes than in healthy controls (p<0.05). Basal glucose uptake was not different between groups, although there was a trend for uptake to be higher in the control group (p=0.09), and increased significantly to a similar extent in the two groups during the clamp (p<0.05).

Table 3.

Substrate and palmitate kinetics across the leg

| Basal

|

Clamp

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | T2DM | Control | T2DM | |

| Femoral arterial glucose (mmol/l) | 5.4±0.2 | 7.6±1.3b | 8.3±0.2a | 10.7±0.3a,b |

| Glucose uptake (μmol min−1 kg FFM−1) | 4.2±0.4 | 3.1±1.2 | 23.1±9.5a | 19.9±5.9a |

| Plasma insulin (pmol/l) | 33±7 | 63±12b | 243±24a | 143±30a |

| Plasma NEFA (μmol/l) | 475±63 | 708±32b | 1052±188a | 956±142 |

| Femoral arterial palmitate (nmol/ml) | 128±28 | 211±56b | 141±27 | 194±61b |

| Femoral venous palmitate (nmol/ml) | 133±14 | 219±24b | 136±10 | 196±27b |

| Blood flow (ml min−1 100 ml leg−1) | 3.2±0.5 | 4.5±0.5 | 4.2±1.0 | 4.6±0.7 |

| Palmitate delivery to leg | 237±59 | 583±10b | 349±88 | 495±64b |

| Palmitate fractional extraction (%) | 34±6 | 40±3 | 36±3 | 42±2 |

| Femoral arterial CO2 (μmol/ml) | 22±1 | 22±1 | 20±1a | 21±1 |

| Femoral venous CO2 (μmol/ml) | 24±1 | 25±1 | 22±1a | 22±2a |

| Palmitate uptake oxidised (%) | 21±7 | 15±5 | 6±3a | 1±0.3a |

| Palmitate oxidation | 12±2 | 34±14 | 5±2a | 2±1a |

| Palmitate non-oxidative disposal | 55±13 | 190±37b | 118±35c | 201±24b |

Palmitate kinetic rates are in nmol min−1 100 g leg FFM−1 unless indicated otherwise; values are mean±SEM

T2DM Type 2 diabetes mellitus, FFM fat-free mass

Significantly different from basal values (p<0.05)

Significantly different from controls (p<0.05)

p=0.08 compared with basal condition

Basal and clamp blood flows were not different between groups. Arterial palmitate concentrations were significantly higher in type 2 diabetes at baseline and during the clamp (p<0.05, group effect) (Table 3). Palmitate delivery to the leg was significantly greater under basal conditions and during the clamp in type 2 diabetes compared with controls (p<0.05, group effect).

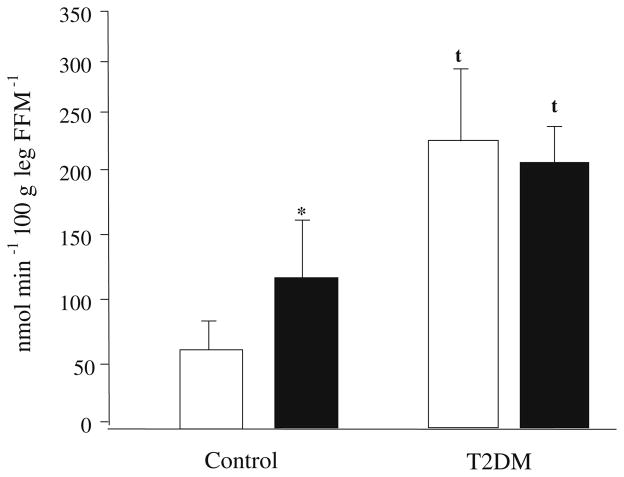

Palmitate uptake across the leg was significantly greater in the group with type 2 diabetes than in controls (Fig. 2) at baseline and during clamp (p<0.001, group effect). Palmitate uptake increased significantly during the clamp in the control group only (p≤0.05). The basal percentage of palmitate uptake that was oxidised and palmitate oxidation across the leg were not significantly different between groups, but both were significantly reduced during the clamp period in both groups (Table 3) (p<0.05). The rate of palmitate shunted towards storage (non-oxidative disposal of palmitate across the leg) was also significantly higher in subjects with type 2 diabetes compared with controls under basal conditions and during the clamp (p=0.01, group effect) (Table 3). During the clamp period, the rate of non-oxidative disposal of palmitate increased in the controls (p=0.08). The rate of non-oxidative disposal of palmitate did not change during the clamp in type 2 diabetes, but remained elevated (i.e. significantly higher than the uptake in the control group).

Fig. 2.

Palmitate uptake across the leg in controls and patients with type 2 diabetes (T2DM) under basal (open bars) and clamp (closed bars) conditions. FFM Fat-free mass. Kinetic rates are mean±SEM. *p≤0.05 for difference from basal values; tp≤0.05 for difference from healthy controls

Whole-body fat and glucose oxidation

Whole-body substrate oxidation and palmitate kinetic rates are shown in Table 4. The respiratory quotient was significantly lower under basal conditions (by 7%) and during the clamp (by 16%) in type 2 diabetes compared with controls (p<0.05). Whole-body fat oxidation was 30% higher under basal conditions and 90% higher during the clamp in type 2 diabetic subjects than in controls (p<0.05). Furthermore, whole-body fat oxidation decreased significantly during the clamp in both groups (p<0.05). Whole-body carbohydrate oxidation increased significantly during the clamp in both groups (p<0.05), and was significantly greater in the controls under both conditions (p<0.05). Basal whole body plasma fatty acid oxidation, measured from the tracer data, was not significantly different between groups and significantly decreased during the clamp in both groups (p<0.05).

Table 4.

Whole-body substrate oxidation rates and palmitate kinetics

| Basal

|

Clamp

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | T2DM | Control | T2DM | |

| Respiratory quotient | 0.81±0.01 | 0.75±0.01a | 0.96±0.03b | 0.84±0.03a,b |

| Total fat oxidation | 2.7±0.2 | 3.8±0.2a | 0.2±0.7b | 2.2±0.6a,b |

| Total carbohydrate oxidation | 6.7±0.6 | 2.2±1.1a | 18.2±1.2b | 8.8±2.5a,b |

| Whole body plasma fat oxidation | 1.8±0.3 | 2.1±0.5 | 1.2±0.5b | 0.7±0.1b |

| Palmitate rate of appearance | 2.8±0.4 | 3.3±0.5 | 3.9±0.6 | 3.7±0.6 |

Values are mean±SEM; kinetic rates are in μmol min−1 kg−1, palmitate rate of appearance (endogenous + exogenous) is in μmol min−1 kg fat-free mass−1

T2DM Type 2 diabetes mellitus

Significantly different from controls (p<0.05)

Significantly different from basal values (p<0.05)

Muscle malonyl-CoA

Basal skeletal muscle malonyl-CoA concentration was not different between controls and subjects with type 2 diabetes (Fig. 3). Skeletal muscle malonyl-CoA concentration increased significantly during the clamp in both controls (0.14±0.05 to 0.24±0.05 pmol/mg) and patients with type 2 diabetes (0.09±0.01 to 0.20±0.02 pmol/mg) (p<0.05). However, there were no differences between groups in the concentration of malonyl-CoA following the clamp (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Skeletal muscle malonyl-CoA concentration in controls and patients with type 2 diabetes (T2DM). Malonyl-CoA concentration increased significantly from basal (open bars) to clamp conditions (closed bars) in both groups. Values are mean±SEM. *p≤0.05 for difference from basal values

Discussion

The major and novel finding of this study is that we did not find any postabsorptive differences in skeletal muscle malonyl-CoA concentrations between the patients with type 2 diabetes and the non-diabetic controls. In addition, in contrast to what we had originally hypothesised, malonyl-CoA concentrations increased to the same extent during the physiological hyperglycaemic–hyperinsulinaemic clamp both in patients with type 2 diabetes and in controls, with no significant differences between the groups. In agreement with the malonyl-CoA data, we found no basal differences in palmitate oxidation across the leg or in the percentage of palmitate uptake oxidised between patients with type 2 diabetes and non-diabetic controls. During the clamp, when the malonyl-CoA concentrations were elevated, palmitate oxidation was significantly decreased to the same extent in both groups. However, palmitate uptake and non-oxidative disposal of palmitate across the leg were significantly higher in subjects with type 2 diabetes during both the postabsorptive period and during the clamp. We have previously reported a significant increase in skeletal muscle malonyl-CoA concentration in healthy individuals after infusion of glucose at a high rate [19]. Smaller increases in skeletal muscle malonyl-CoA concentration have been observed following a euglycaemic-hyperinsulinaemic clamp in healthy individuals [34] and in patients with type 2 diabetes [35]. However, since glucose is the primary contributor to muscle malonyl-CoA, we cannot rule out the possibility that more moderate hyperglycaemia may produce different results. In any event, our study is the first to specifically address the potential role of malonyl-CoA in muscle fatty acid kinetics in type 2 diabetes and it clearly indicates that muscle malonyl-CoA concentrations are not abnormally elevated in individuals with type 2 diabetes during either fasting or postprandial conditions. Thus, we can safely state that the dysregulation of muscle fatty acid metabolism in type 2 diabetes is independent of muscle malonyl-CoA concentrations.

An increase in fatty acid delivery and uptake could also contribute to the excess lipid accumulation in skeletal muscle of patients with type 2 diabetes. In the present study, we observed significantly greater rates of postabsorptive palmitate delivery and uptake across the leg in type 2 diabetes compared with the non-diabetic controls, which is similar to recent data obtained in the postprandial state [20]. In addition, we also found that the rate of post-absorptive non-oxidative disposal of palmitate (i.e. fatty acids shunted towards storage and away from oxidation) was also significantly increased in patients with type 2 diabetes. Our data are also in agreement with a recent study in which elevated rates of fatty acid transport along with increased intramyocellular lipid and FAT/CD36 in obese and type 2 diabetes subjects were reported in giant sarcolemmal vesicles [21]. In addition, the increased rates of palmitate uptake and non-oxidative disposal in type 2 diabetes remained elevated during hyperglycaemia with hyperinsulinaemia. Palmitate uptake increased during the clamp in the control group but not in the group with type 2 diabetes, even though palmitate uptake during the clamp was still elevated over basal control values. This may have been due to the individuals with type 2 diabetes having a higher level of upregulation of basal fatty acid transport that is not further influenced by insulin stimulation [21]. A limitation of the fatty acid tracer data is that the measurement of fatty acid kinetics across the leg includes not only the primary component of the leg (i.e. muscle) but also contributions from fat and bone. We did not find significant differences in leg composition between the group with type 2 diabetes and the non-diabetic control group. However, subjects with type 2 diabetes did have 0.8 kg more fat in their legs than did the control group. Nevertheless, we are confident that our findings of greater than threefold higher fatty acid uptake and non-oxidative disposal are truly representative of muscle, since muscle accounted for at least 70–75% of the leg and we are not aware of any differences in rates of fatty acid uptake between fat and muscle. Although our data suggest a role for elevated fatty acid uptake in the accumulation of lipid within muscle cells of patients with type 2 diabetes, future studies are needed to determine specifically whether the elevated fatty acid uptake causes increased intramyocellular lipid.

We also found some differences between groups in insulin values during the clamp despite identical infusion rates of insulin. The lower insulin concentration in our group with type 2 diabetes was most likely due to reduced endogenous insulin production in this group in response to the hyperglycaemic clamp (i.e. beta cell dysfunction). Furthermore, the lack of an increase in palmitate uptake during the clamp in the group with type 2 diabetes may have been due to the smaller increment in insulin concentrations. However, since glucose uptake in the subjects with type 2 diabetes was not different from that in the control group (despite the former having lower insulin concentrations) it is likely that glucose uptake was maximal at the insulin concentration obtained in the type 2 diabetes group, and probably aided by the mass effect produced by the higher blood glucose concentrations. The malonyl-CoA data also support this conclusion since malonyl-CoA increased to a similar extent during the clamp in the two groups and malonyl-CoA production is primarily derived from cellular glucose metabolism.

Dysregulation in fatty acid metabolism is well-known in type 2 diabetes as several groups have reported elevations in plasma fatty acid levels, reduced skeletal muscle mitochondrial content and total oxidative capacity, and enhanced fatty acid transporters in type 2 diabetes [3, 6, 11, 20, 21, 36–38]. Interestingly, some studies have reported significantly lower rates of whole-body fat oxidation in individuals with type 2 diabetes [39] and in extremely obese individuals compared with controls [40]. In contrast, previous studies have also reported whole-body fat oxidation, measured by indirect calorimetry, to be higher under basal and insulin-stimulated conditions in obese individuals compared with healthy controls [41, 42], which is in agreement with the findings of the present investigation. Thus, the dysregulation of fat metabolism in type 2 diabetes appears to be primarily centred on elevated fatty acid concentrations and/or uptake, reduced mitochondrial content and oxidative capacity, and the accumulation of lipid within muscle cells. Interestingly, our femoral vein 13CO2 enrichments were significantly lower than the breath 13CO2 enrichments. This suggests that fat oxidation during hyperglycaemia and hyperinsulinaemia was higher in other tissues, such as liver and adipose, and that its regulation may be tissue-specific. On the other hand, others have reported lower rates of fatty acid uptake under postabsorptive conditions in patients with type 2 diabetes [43, 44]. The discrepancy between our findings, as well as those of Bonen et al. [21], and the other studies [43, 44] is probably due to differences in study design and subject characteristics. For example, Blaak et al. [43] reported no differences in plasma NEFA and palmitate concentrations between controls and obese subjects with type 2 diabetes. In addition, fatty acid uptake was measured across the forearm rather than the leg. The second study measured uptake at the whole-body level [44]. Thus, it appears that both increased delivery and uptake of fatty acids by skeletal muscle and mitochondrial dysfunction may contribute to the dysregulation of muscle fatty acid metabolism in type 2 diabetes.

In summary, human skeletal muscle malonyl-CoA concentrations are not abnormally elevated in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and are significantly increased to the same extent following physiological hyperglycaemia with hyperinsulinaemia both in subjects with type 2 diabetes and in non-diabetic controls. Postabsorptive palmitate oxidation across the leg was not different from controls in our subjects with type 2 diabetes; however, palmitate uptake and non-oxidative disposal of palmitate (shunting of fatty acids towards storage within the muscle) were significantly higher. Palmitate oxidation significantly decreased during the clamp in both groups, whereas palmitate uptake and non-oxidative disposal continued to be higher in subjects with type 2 diabetes. We conclude that, contrary to our hypothesis, the dysregulation of muscle fatty acid metabolism in type 2 diabetes is independent of muscle malonyl-CoA. However, elevated fatty acid uptake in type 2 diabetes may be a key contributor to the increase in fatty acids shunted towards storage within muscle. Further studies are warranted to address this hypothesis directly.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the study volunteers for their patience and dedication and all the nurses and personnel of the General Clinical Research Center of the University of Southern California for their help with the conduct of the clinical portion of this study. We also wish to thank K. E. Yarasheski for kindly providing13CO2 analysis for blood and breath samples at the Washington University Medical School Mass Spectrometry Resource Center. This study was supported by the Zumberge Research and Innovation Fund; grant M01-RR-43 from the General Clinical Research Branch, NCRR, NIH; grant S10 RR16650 from the Shared Instrumentation Grant Program, National Center for Research Resources, NIH; grant R01 AG18311 from the National Institute on Aging, NIH; and grant NIH-NCRR-00954 (Washington University Medical School Mass Spectrometry Resource Center).

Abbreviation

- CPT-1

carnitine palmitoyl transferase-1

Contributor Information

J. A. Bell, Department of Kinesiology, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA

E. Volpi, Department of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA

S. Fujita, Department of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA

J. G. Cadenas, Department of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA

B. B. Rasmussen, Email: blrasmus@utmb.edu, Department of Physical Therapy, Division of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Texas Medical Branch, Sealy Center on Aging and Stark Diabetes Center, 301 University Boulevard, Galveston, TX 77555-1144, USA

References

- 1.DeFronzo RA. Insulin resistance: a multifaceted syndrome responsible for NIDDM, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidaemia and atherosclerosis. Netherlands J Med. 1997;50:191–197. doi: 10.1016/s0300-2977(97)00012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shah P, Vella A, Basu A, et al. Elevated free fatty acids impair glucose metabolism in women: decreased stimulation of muscle glucose uptake and suppression of splanchnic glucose production during combined hyperinsulinemia and hyperglycemia. Diabetes. 2003;52:38–42. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boden G, Lebed B, Schatz M, Homko C, Lemieux S. Effects of acute changes of plasma free fatty acids on intra-myocellular fat content and insulin resistance in healthy subjects. Diabetes. 2001;50:1612–1617. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.7.1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Itan SI, Ruderman NB, Schmieder F, Boden G. Lipid-induced insulin resistance in human muscle is associated with changes in diacylglycerol, protein kinase C, and IkappaB-alpha. Diabetes. 2002;51:2005–2011. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.7.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nielsen S, Guo Z, Johnson CM, Hensrud DD, Jensen MD. Splanchnic lipolysis in human obesity [see comment] J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1582–1588. doi: 10.1172/JCI21047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Basu A, Basu R, Shah P, Vella A, Rizza RA, Jensen MD. Systemic and regional free fatty acid metabolism in type 2 diabetes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2001;280:E1000–E1006. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.280.6.E1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goodpaster BH, Theriault R, Watkins SC, Kelley DE. Intramuscular lipid content is increased in obesity and decreased by weight loss. Metab Clin Exp. 2000;49:467–472. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(00)80010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelley DE, Goodpaster B, Wing RR, Simoneau JA. Skeletal muscle fatty acid metabolism in association with insulin resistance, obesity, and weight loss. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:E1130–E1141. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1999.277.6.E1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mandarino LJ, Consoli A, Jain A, Kelley DE. Interaction of carbohydrate and fat fuels in human skeletal muscle: impact of obesity and NIDDM. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:E463–E470. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1996.270.3.E463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelley DE, Goodpaster BH. Skeletal muscle triglyceride. An aspect of regional adiposity and insulin resistance. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:933–941. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.5.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pan DA, Lillioja S, Kriketos AD, et al. Skeletal muscle triglyceride levels are inversely related to insulin action. Diabetes. 1997;46:983–988. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.6.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmitz-Peiffer C, Browne CL, Oakes ND, et al. Alterations in the expression and cellular localization of protein kinase C isozymes epsilon and theta are associated with insulin resistance in skeletal muscle of the high-fat-fed rat. Diabetes. 1997;46:169–178. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.2.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooney GJ, Thompson AL, Furler SM, Ye J, Kraegen EW. Muscle long-chain acyl CoA esters and insulin resistance. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;967:196–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodpaster BH, Thaete FL, Simoneau JA, Kelley DE. Subcutaneous abdominal fat and thigh muscle composition predict insulin sensitivity independently of visceral fat. Diabetes. 1997;46:1579–1585. doi: 10.2337/diacare.46.10.1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krssak M, Falk Petersen K, Dresner A, et al. Intra-myocellular lipid concentrations are correlated with insulin sensitivity in humans: a 1H NMR spectroscopy study. Diabetologia. 1999;42:113–116. doi: 10.1007/s001250051123. [erratum: Diabetologia 42:386] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ellis BA, Poynten A, Lowy AJ, et al. Long-chain acyl-CoA esters as indicators of lipid metabolism and insulin sensitivity in rat and human muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2000;279:E554–E560. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2000.279.3.E554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lowell BB, Shulman GI. Mitochondrial dysfunction and type 2 diabetes. Science. 2005;307:384–387. doi: 10.1126/science.1104343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGarry JD. Malonyl-CoA and carnitine palmitoyltransferase I: an expanding partnership. Biochem Soc Trans. 1995;23:481–485. doi: 10.1042/bst0230481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rasmussen BB, Holmback UC, Volpi E, Morio-Liondore B, Paddon-Jones D, Wolfe RR. Malonyl coenzyme A and the regulation of functional carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1 activity and fat oxidation in human skeletal muscle [see comment] J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1687–1693. doi: 10.1172/JCI15715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ravikumar B, Carey PE, Snaar JE. Real-time assessment of postprandial fat storage in liver and skeletal muscle in health and type 2 diabetes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;288:E789–E797. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00557.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bonen A, Parolin ML, Steinberg GR, et al. Triacylglycerol accumulation in human obesity and type 2 diabetes is associated with increased rates of skeletal muscle fatty acid transport and increased sarcolemmal FAT/CD36. FASEB J. 2004;18:1144–1146. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1065fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wallace TM, Levy JC, Matthews DR. Use and abuse of HOMA modeling. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1487–1495. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.6.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patterson BW, Zhao G, Elias N, Hachey DL, Klein S. Validation of a new procedure to determine plasma fatty acid concentration and isotopic enrichment. J Lipid Res. 1999;40:2118–2124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wolfe RR. Radioactive and stable isotope tracers in biomedicine. Wiley-Liss; New York: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sacchetti M, Saltin B, Osada T, van Hall G. Intramuscular fatty acid metabolism in contracting and non-contracting human skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2002;540:387–395. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frayn KN. Calculation of substrate oxidation rates in vivo from gaseous exchange. J Appl Physiol Resp Environ Exerc Physiol. 1983;55:628–634. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1983.55.2.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sacchetti M, Saltin B, Olsen D, van Hall G. High triacylglycerol turnover rate in human skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2004;561.3:883–891. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.075135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Hall G, Bulow J, Sacchetti M, Al Mulla N, Lyngso D, Simonsen L. Regional fat metabolism in human splanchnic and adipose tissues: the effect of exercise. J Physiol. 2002;543:1033–1046. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.022392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saha AK, Vavvas D, Kurowski TG, et al. Malonyl-CoA regulation in skeletal muscle: its link to cell citrate and the glucose-fatty acid cycle. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:E641–E648. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1997.272.4.E641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Winder WW, Arogyasami J, Elayan IM, Cartmill D. Time course of exercise-induced decline in malonyl-CoA in different muscle types. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:E266–E271. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1990.259.2.E266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mills SE, Foster DW, McGarry JD. Interaction of malonyl-CoA and related compounds with mitochondria from different rat tissues. Relationship between ligand binding and inhibition of carnitine palmitoyltransferase I. Biochem J. 1983;214:83–91. doi: 10.1042/bj2140083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jorfeldt L, Juhlin-Dannfelt A. The influence of ethanol on splanchnic and skeletal muscle metabolism in man. Metab Clin Exp. 1978;27:97–106. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(78)90128-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jorfeldt L, Wahren J. Leg blood flow during exercise in man. Clin Sci. 1971;41:459–473. doi: 10.1042/cs0410459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bavenholm PN, Pigon J, Saha AK, Ruderman NB, Efendic S. Fatty acid oxidation and the regulation of malonyl-CoA in human muscle. Diabetes. 2000;49:1078–1083. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.7.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bavenholm PN, Kuhl J, Pigon J, Saha AK, Ruderman NB, Efendic S. Insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes: association with truncal obesity, impaired fitness, and atypical malonyl coenzyme A regulation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:82–87. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020330. [erratum: J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88:2036] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simoneau JA, Veerkamp JH, Turcotte LP, Kelley DE. Markers of capacity to utilise fatty acids in human skeletal muscle: relation to insulin resistance and obesity and effects of weight loss. FASEB J. 1999;13:2051–2060. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.14.2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simoneau JA, Kelley DE. Altered glycolytic and oxidative capacities of skeletal muscle contribute to insulin resistance in NIDDM. J Appl Physiol. 1997;83:166–171. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.83.1.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kelley DE, He J, Menshikova EV, Ritov VB. Dysfunction of mitochondria in human skeletal muscle in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2002;51:2944–2950. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.10.2944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kelley DE, Simoneau JA. Impaired free fatty acid utilization by skeletal muscle in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:2349–2356. doi: 10.1172/JCI117600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hulver MW, Berggren JR, Cortright RN, et al. Skeletal muscle lipid metabolism with obesity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;284:E741–E747. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00514.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Golay A, Felber JP, Meyer HU, Curchod B, Maeder E, Jequier E. Study on lipid metabolism in obesity diabetes. Metab Clin Exp. 1984;33:111–116. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(84)90121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Felber JP, Ferrannini E, Golay A, et al. Role of lipid oxidation in pathogenesis of insulin resistance of obesity and type II diabetes. Diabetes. 1987;36:1341–1350. doi: 10.2337/diab.36.11.1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blaak EE, Wagenmakers AJ, Glatz JF, et al. Plasma NEFA utilization and fatty acid-binding protein content are diminished in type 2 diabetic muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2000;279:E146–E154. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2000.279.1.E146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mensink M, Blaak EE, van Baak MA, Wagenmakers AJ, Saris WH. Plasma free fatty acid uptake and oxidation are already diminished in subjects at high risk for developing type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2001;50:2548–2554. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.11.2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]