Abstract

This study evaluated the antilipogenic and anti-inflammatory effects of Codonopsis lanceolata (C. lanceolata) root extract in mice with alcohol-induced fatty liver and elucidated its underlying molecular mechanisms. Ethanol was introduced into the liquid diet by mixing it with distilled water at 5% (wt/v), providing 36% of the energy, for nine weeks. Among the three different fractions prepared from the C. lanceolata root, the C. lanceolata methanol extract (CME) exhibited the most remarkable attenuation of alcohol-induced fatty liver with respect to various parameters such as hepatic free fatty acid concentration, body weight loss, and hepatic accumulations of triglyceride and cholesterol. The hepatic gene and protein expression levels were analysed via RT-PCR and Western blotting, respectively. CME feeding significantly restored the ethanol-induced downregulation of the adiponectin receptor (adipoR) 1 and of adipoR2, along with their downstream molecules. Furthermore, the study data showed that CME feeding dramatically reversed ethanol-induced hepatic upregulation of toll-like receptor- (TLR-) mediated signaling cascade molecules. These results indicate that the beneficial effects of CME against alcoholic fatty livers of mice appear to be with adenosine- and adiponectin-mediated regulation of hepatic steatosis and TLR-mediated modulation of hepatic proinflammatory responses.

1. Introduction

Fatty liver is the most common and earliest response of the liver to heavy alcohol consumption and may develop into alcoholic hepatitis and fibrosis [1]. It has been traditionally held that, during alcohol metabolism, the increase in the cellular NADH concentration generated by alcohol and aldehyde dehydrogenases impairs β-oxidation and tricarboxylic acid cycle activity in the liver, which in turn leads to severe FFA overload and enhanced synthesis of triacylglycerol in the liver [2]. More recently, two transcription factors, the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) α and PPARγ, have been discovered as new mechanisms that control hepatic fatty acid oxidation and synthesis, respectively [3, 4]. Ethanol feeding impairs fatty acid catabolism in the liver partly by blocking PPARα-mediated responses in C57BL/6J mice. In the meantime, dietary supplementation of ethanol-fed animals with a PPARα agonist induces the expression of PPARα target genes and stimulates the rate of fatty acid β-oxidation, which prevents alcoholic fatty liver [5]. In contrast to PPARα, hepatic PPARγ contributes to triglyceride homeostasis, which regulates both triglyceride clearance from the circulation and the lipogenic program [6]. Ethanol increases the mRNA expressions of PPARγ and lipid synthetic enzymes, ATP citrate lyase (ACL), and fatty acid synthase (FAS) in mice liver [1].

Ethanol is well known to stimulate increased extracellular adenosine concentration through its action on the nucleoside transporter. Ethanol ingestion increases purine release into the bloodstream and urine in normal volunteers [7–9] and into the extracellular space in liver slices obtained from mice [10, 11]. Extracellular adenosine regulates various physical processes [12], including hepatic fibrosis [10, 11], ureagenesis [13, 14], and glycogen metabolism [15, 16], as well as peripheral lipid metabolism [17, 18]. These physiological effects of adenosine are mediated by a family of four G-protein-coupled receptors: A1, A2A, A2B, and A3 (A1R, A2AR, A2BR, and A3R), each of which has a unique pharmacological profile, tissue distribution, and effector coupling [19]. Recently, Peng et al. reported that ethanol-mediated increases in extracellular adenosine, which act via adenosine A1R and A2BR, link the ingestion and metabolism of ethanol to the development of hepatic steatosis. Thus, they suggested that targeting adenosine receptors may be effective in the prevention of alcohol-induced fatty liver [1].

Although fatty liver was thought to be relatively benign, more recent studies show that fat accumulation makes the liver more susceptible to injury from other agents such as drugs and toxins, especially endotoxins [20], which are believed to be involved in the pathogenesis of alcoholic hepatitis and fibrosis [21, 22]. Alcohol consumption induces a state of a “leaky gut” that increases plasma and liver endotoxin levels and leads to the production of the tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) by Kupffer cells via the toll-like receptor (TLR) 4, which is known to mediate lipopolysaccharide- (LPS-) induced signal transduction and to eventually contribute to liver injury [23]. Ethanol-fed mice exhibited an oxidative stress that was dependent on the upregulation of multiple TLRs (TLR1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 8, and 9) in the liver and was sensitive to liver inflammation induced by multiple bacterial products recognized by the TLRs [24].

Codonopsis lanceolata (C. lanceolata), which belongs to the Campanulaceae family, is a perennial herb that grows naturally in moist places in woods, low mountains, and hills [25]. It is commonly found in East Asia, particularly in China [25]. C. lanceolata, which is composed of various active components including tannins, saponins, polyphenolics, alkaloids, essential oils, and steroids, has long been prescribed in traditional folk medicine in Korea, Japan, and China [26–28]. The dried roots of C. lanceolata have been used as a traditional remedy for lung inflammatory diseases such as asthma, tonsillitis, and pharyngitis. The total methanol extracts of the fresh leaves or roots of C. lanceolata significantly suppress the production of TNFα and nitric oxide, the expression of interleukin (IL)-3 and IL-6, and LPS-mediated phagocytic uptake in RAW 264.7 cells [28]. In a rat model, C. lanceolata water extract significantly improved the hepatic accumulation of triglyceride and cholesterol induced by a high-fat diet [29]. Although the lipid-lowering effect of C. lanceolata extract has been demonstrated in a rodent model with diet-induced obesity, the protective effects of this plant against alcoholic fatty liver diseases have not yet been explored. In this study, the potent bioactivities of the C. lanceolata methanol extract that can be used as natural compound or pharmaceutical supplements for the prevention and/or treatment of alcoholic fatty liver were demonstrated. The mechanisms by which the C. lanceolata methanol extract performs its antilipogenic and anti-inflammatory actions were investigated in the hepatic tissues of mice with chronic ethanol consumption.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of C. lanceolata Extract

C. lanceolata, which is cultivated in Gangwon-do, Korea, was purchased and freeze dried. Freshly dried material was ground into fine powder in an electric grinder and stored in dessicator. 200 g plant powder was refluxed with 95% methyl alcohol (MeOH) in a round bottom flask on a water bath for 3 h. Crude MeOH extract was filtered out and evaporated to dryness for the preparation of the C. lanceolata methanol extract (CME). The residual methanol extract was again refluxed with distilled water for 5 h and filtered. The filtrate, thus obtained, was again added with ethanol at the ratio of 1 : 4 and then stirred for 1 h at 4°C. Following their centrifugation at 5,000 ×g for 30 min at 4°C, the supernatant was concentrated in a rotary vacuum evaporator and freeze dried for the preparation of the C. lanceolata ethanol supernatant (CES), and the pellets were air dried and freeze dried for the preparation of the C. lanceolata ethanol precipitate (CEP). The yields of these three extracts were 3.84% (CME), 5.05% (CES), and 3.30% (CEP) of the wet C. lanceolata root, respectively.

2.2. Animals and Diets

Specific pathogen-free male C57BL/6N mice (eight weeks old) were purchased (Orient, Gyeonggi-do, Korea) and acclimatized to the authors' animal facility for one week prior to the experimentation. The mice were kept individually in sterilized animal quarters with controlled temperature (at 21 ± 2°C) and humidity (at 50 ± 5%) and with 12 h light and dark cycles and were allowed free access to standard chow and tap water during the acclimatization period. The animals were then randomly divided into five groups (n = 8) and fed the normal diet (ND), the ethanol diet (ED), the CME-supplemented ethanol diet (MED), the CES-supplemented ethanol diet (ESD), or the CEP-supplemented ethanol diet (EPD) for nine weeks. The mice in the ED group consumed a liquid diet wherein ethanol provided 36% of the energy, as described by Lieber et al. [30]. Ethanol was introduced into the diet by gradually mixing it with distilled water, from 0% (wt/v) to 5% (wt/v), over a one-week period for adaptation, and was provided at 5% (wt/v) for the next eight weeks. The ND mice received the same diet but with isocaloric amounts of dextrin-maltose instead of ethanol, and the MED, ESD, and EPD mice were fed the ethanol diet that contained 0.091% (wt/v) CME, CES, and CEP, respectively. The compositions of the experimental diets are given in Table 1. The ND, MED, DES, and EPD mice were pair fed so that their consumption would be isocalorically equivalent to the consumption on the previous day of the ED mice that were individually paired with them. The animals that were used in this study were treated in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, Commission on Life Sciences, National Research Council, 1996), as approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Yonsei University.

Table 1.

Compositions of experimental diets.

| Ingredient | ND | ED | MED | ESD | EPD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| g/L | |||||

| Casein | 41.4 | 41.40 | 41.40 | 41.40 | 41.40 |

| L-cystine | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| DL-methionine | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 |

| Corn oil | 8.50 | 8.50 | 8.50 | 8.50 | 8.50 |

| Olive oil | 28.40 | 28.40 | 28.40 | 28.40 | 28.40 |

| Safflower oil | 2.70 | 2.70 | 2.70 | 2.70 | 2.70 |

| Dextrine-maltose1 | 115.20 | 25.60 | 25.60 | 25.60 | 25.60 |

| Vitamin mix (AIN-76G)2 | 2.50 | 2.50 | 2.50 | 2.50 | 2.50 |

| Mineral mix (AIN-76G)3 | 8.75 | 8.75 | 8.75 | 8.75 | 8.75 |

| Choline bitartrate | 0.53 | 0.53 | 0.53 | 0.53 | 0.53 |

| Cellulose | 10.00 | 10.00 | 10.00 | 10.00 | 10.00 |

| Xanthan gum | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 |

| Ethanol | 50.00 | 50.00 | 50.00 | 50.00 | |

| CME | 0.91 | ||||

| CES | 0.91 | ||||

| CEP | 0.91 | ||||

| Water | 778.22 | 817.82 | 816.91 | 816.91 | 816.91 |

|

| |||||

| Total | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 |

1Dextrin : maltose = 80 : 20.

2Vitamin mixture (g/kg mix); thiamin · HCl 0.6; riboflavin 0.6; nicotinamide 25; pyridoxine· HCl 0.7; nicotinic acid 3; D-calcium pantothenate 1.6; folic acid 0.2; D-biotin 0.02; cyanocobalamin (vitamin B12) 0.001; retinyl palmitate (250,000 IU/gm) 1.6; DL-α- tocopherol acetate (250 IU/gm) 20; cholecalciferol (vitamin D3) 0.25; menaquinone (vitamin K2) 0.05; sucrose, finely powdered 972.9.

3AIN-76 Mineral mixture (g/kg mix); CaHPO4 500; NaCl 74; K2H6O7H2O 220; K2SO4 52; MgO 24; MnCO3 3.57; Fe (C6H5O7) · 6H2O 6; ZnCO3 1.6; CuCO3 0.3; KIO3 0.01; Na2SeO3 · 5H2O 0.01; CrK (SO4)2 0.55; sucrose, finely powdered 118.

2.3. Histological Examination

The liver tissue specimens were fixed in 10% buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin, cut at thicknesses of 5 μm, and later stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for the histological examination of fat droplets.

2.4. Biochemical Assays

The serum concentrations of total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triglyceride, and free fatty acid were determined using commercial kits (BioClinical System, Gyeonggi-do, Korea). Hepatic lipids were extracted through the procedure developed by Folch et al. [31], using a chloroform-methanol mixture (2 : 1, v/v). The dried lipid residues were dissolved in 1 mL of ethanol for the cholesterol and triglyceride measurements. The hepatic cholesterol, triglyceride, and free fatty acid concentrations were analyzed using the same enzymatic kit that was used in the serum analyses. The serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) activities were measured using commercial reagents (Bayer, USA).

2.5. Isolation of Total RNA and Semiquantitative RT-PCR

The total RNA was extracted from the liver using a Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, USA) and was reverse transcribed using the Superscript II kit (Invitrogen, USA) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The primers for the PCR analysis were synthesized by Bioneer (Korea). The forward (F) and reverse (R) primer sequences for the genes that were involved in the experiment are shown in the Supplementary Material available online at doi: 10.1155/2012/141395. The PCR for the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was performed on each sample as an internal positive-control standard. The number of cycles and the annealing temperature were optimized for each primer pair. Amplification of the GAPDH, A1R, A2AR, A2BR, A3R, PPARα, carnitine palmitoyltransferase (CPT-1), microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (MTP), long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (LCAD), medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD), PPARγ, retinoid X receptor (RXR), CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein-α (C/EBPα), lipoprotein lipase (LPL), adipocyte protein 2 or fatty acid binding protein 4 (aP2), FAS, TLRs, LPS binding protein (LBP), cluster of differentiation 14 (CD14), myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 (MyD88), myelin and lymphocyte protein (MAL), TLR adaptor molecule (TRIF), TNF-receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6), interferon regulatory factors (IRFs), nuclear factor kappa B-p50 (p50), p65, interferon α (IFNα), IFNβ, IL-12-p40, chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 2 (CXCL2), adiponectin receptor 1 (adipoR1), adipoR2, silent-mating-type information regulation 2 homolog 1 (SIRT1), peroxisome proliferative activated receptor gamma coactivator 1 alpha (PGC1α), and sterol regulatory element binding transcription factor 1 (SREBP-1c) was initiated via 5 min of denaturation at 94°C for 1 cycle, followed by 30 or 35 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 55 or 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min and via 10 min of incubation at 72°C. The sequences of the primer pairs and PCR conditions (annealing temperatures, cycles, and product sizes) that were used in the RT-PCR experiments are shown in the Supplementary Material. The PCR products were then separated in a 2% agarose gel and visualized in a gel documentation system (Alpha Innotech, USA). The intensity of the bands on the gels was converted into a digital image with a gel analyzer.

2.6. Western Blot Analysis

For the Western blot studies, protein extracts were obtained from the mice livers using a commercial lysis buffer (Intron, USA) that contained a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, USA). The protein concentrations were determined with the Bio-rad protein assay kit (Bio-rad, USA). The Western blot analysis was performed with antibodies that were specific to AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), phospho-AMPK (Thr 72), Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC), phospho-ACC (Ser 79) (Cell Signaling, USA), and β-actin (Santa Cruz, USA). After the SDS-PAGE at 10% acrylamide concentrations, the proteins were transferred to the nitrocellulose membrane, blocked with 5% skim milk in a Tris-buffered saline/Tween buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.05% Tween 20), and incubated with appropriate antibodies overnight. The blots were washed extensively, incubated with a horseradish-peroxidase-linked anti-rabbit or -mouse Ig (Santa Cruz, USA), and washed again. The detection was carried out with the ECL Western blotting kit (Animal Genetics, Korea), after which the blots were exposed to an X-ray film (Agfa, Belgium).

2.7. Statistical Analysis

The results of the body weight gain, liver weight, and serum and hepatic biochemistries were expressed as the mean values ± SEM of the eight mice in each group. The results of the semiquantitative RT-PCR and Western blot were expressed as the mean values ± SEM of the three independent experiments in which the RNA and protein samples from the eight mice were used, respectively. The analysis of the variance (ANOVA) and the Duncan's multiple range method were used to compare significant differences among the groups. The level of significance was set at P < 0.05 for all the statistical tests.

3. Results

3.1. Body Weight Gain and Blood Biochemistries

The nine-week body weight gain of the mice in the ED group was 51% lower than the value for the pair fed ND mice. The animals that were fed the MED (43% greater) or the ESD (41% greater) exhibited significantly greater body weight gains than the ED mice, whereas the mice that were fed the EPD did not recover the weight they lost from ethanol consumption (Table 2).

Table 2.

Body weight gain and serum biochemistries of mice fed experimental diets.

| ND | ED | MED | ESD | EPD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight gain (g/9 weeks) | 10.9 ± 0.4a1 | 5.3 ± 0.8c | 7.6 ± 0.7b | 7.5 ± 0.6b | 4.6 ± 0.6c |

| Triglyceride (mmol/L) | 0.78 ± 0.01b | 0.81 ± 0.02ab | 0.74 ± 0.03b | 0.86 ± 0.02a | 0.75 ± 0.02b |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 2.17 ± 0.19b | 2.15 ± 0.13b | 1.96 ± 0.13b | 2.65 ± 0.18a | 2.23 ± 0.10a |

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 0.88 ± 0.04b | 1.10 ± 0.10a | 1.17 ± 0.06a | 1.04 ± 0.08ab | 1.09 ± 0.06ab |

| VLDL + LDL cholesterol (mmol/L)2 | 1.29 ± 0.19ab | 1.06 ± 0.15b | 0.79 ± 0.12b | 1.60 ± 0.21a | 1.14 ± 0.15ab |

| Atherogenic index3 | 1.52 ± 0.25a | 1.07 ± 0.21ab | 0.70 ± 0.13b | 1.65 ± 0.21a | 1.12 ± 0.10ab |

| Free fatty acid (μEq/L) | 808 ± 31b | 990 ± 27a | 848 ± 36b | 1074 ± 52a | 883 ± 32b |

| ALT (IU/ml) | 6.87 ± 0.42c | 21.2 ± 0.89a | 17.5 ± 0.53b | 21.3 ± 0.78a | 21.2 ± 1.04a |

| AST (IU/ml) | 17.63 ± 1.63b | 22.3 ± 2.05a | 17.4 ± 1.05b | 24.6 ± 1.04a | 24.9 ± 0.98a |

1Each value is expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 8). Means with different letters within a row are significantly different (P < 0.05).

2VLDL + LDL cholesterol (mmol/L) = Total cholesterol − HDL cholesterol.

3Atherogenic index = (Total cholesterol − HDL cholesterol)/ HDL cholesterol.

Compared to the values for the ED mice, the mice that were fed the MED exhibited significantly lower levels of serum FFA (17% reduction) and lower activities of serum ALT (17% reduction) and AST (22% reduction). They also demonstrated a tendency towards decreasing serum triglyceride, total cholesterol, VLDL + LDL cholesterol, and atherogenic indices, albeit at statistically insignificant levels than those for the mice that were fed the ED. In contrast, the ESD or EPD failed to improve both the lipid levels and enzyme activities in the blood of the mice with chronic ethanol consumption (Table 2).

3.2. Liver Weight and Hepatic Lipid Levels

Histological analysis of the livers with H&E staining revealed prominent lipid accumulation in the livers of the ED fed mice whereas lipid droplets were rare in the livers of the MED, ESD, and EPD-fed mice (Figure 1). ED feeding of the mice for nine weeks resulted in more significant increases in the relative weight of their livers (by 8%) and in the hepatic levels of their triglycerides (43% increase), cholesterol (36% increase), and FFA (52% increase) than in the ND group (Figure 1). The MED or ESD significantly improved the ethanol-induced enlargement of the liver (the relative liver weight was 7% or 6% lower, resp.). The MED, ESD, or EPD significantly reversed the ethanol-induced hepatic accumulations of triglycerides (18%, 11%, and 18% reductions, resp.), cholesterol (22%, 12%, and 18% reductions, resp.), and FFA (29%, 14%, and 22% reductions, resp.). The triglyceride and cholesterol levels in the liver were lowest after the MED consumption among the diets that were supplemented with different fractions of the C. lanceolata root, but the differences between the diets were not statistically significant. The MED group exhibited the most prominent and the most significant improvement in the reduction of the hepatic FFA accumulation, better than did the ESD and EPD groups (P < 0.05) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Codonopsis lanceolata extracts substantially reduces alcohol-induced liver steatosis. (a) Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections of representative liver samples of the treated groups (100×). (b) Changes in the liver-to-body weight ratio. Hepatic triglyceride, free fatty acid, and cholesterol levels are shown in (c, d, and e). The data are expressed as means ± SEM (n = 8). a,b,c,dMeans not sharing a common letter are significantly different (P < 0.05).

3.3. Regulation of Adenosine Receptor-Mediated Signaling Molecules

MED feeding significantly reversed the ethanol-induced upregulation of the A1R and A2BR genes in the livers of the mice and restored the ethanol-induced downregulation of the PPARα, CPT-1, MTP, LCAD, and MCAD genes in the livers of the mice (Figures 2(a) and 2(b)). The supplementation of the ethanol diet with CME significantly blunted the upregulation of these transcription factors and of their target genes due to ethanol.

Figure 2.

mRNA expression of the hepatic genes that are involved in fatty acid oxidation or adipogenesis. The left panel shows an RT-PCR analysis of (a) A1R, A2AR, A2BR, and A3R (b) PPARα, CPT-1, MTP, LCAD, and MCAD and (c) PPARγ, RXR, C/EBPα, LPL, aP2, and FAS expression. The images show the representative agarose gel electrophoresis of the PCR products. The right panel shows the relative expressions of (a) A1R, A2AR, A2BR, and A3R (b) PPARα, CPT-1, MTP, LCAD, and MCAD and (c) PPARγ, RXR, C/EBPα, LPL, aP2, and FAS levels. The data were normalized to the GAPDH levels, and all the expression levels that are displayed are relative to the ND. The results that are shown represent the means ± SEM of the three independent experiments in which RNA samples from eight mice were used. a,b,cMeans not sharing a common letter are significantly different (P < 0.05).

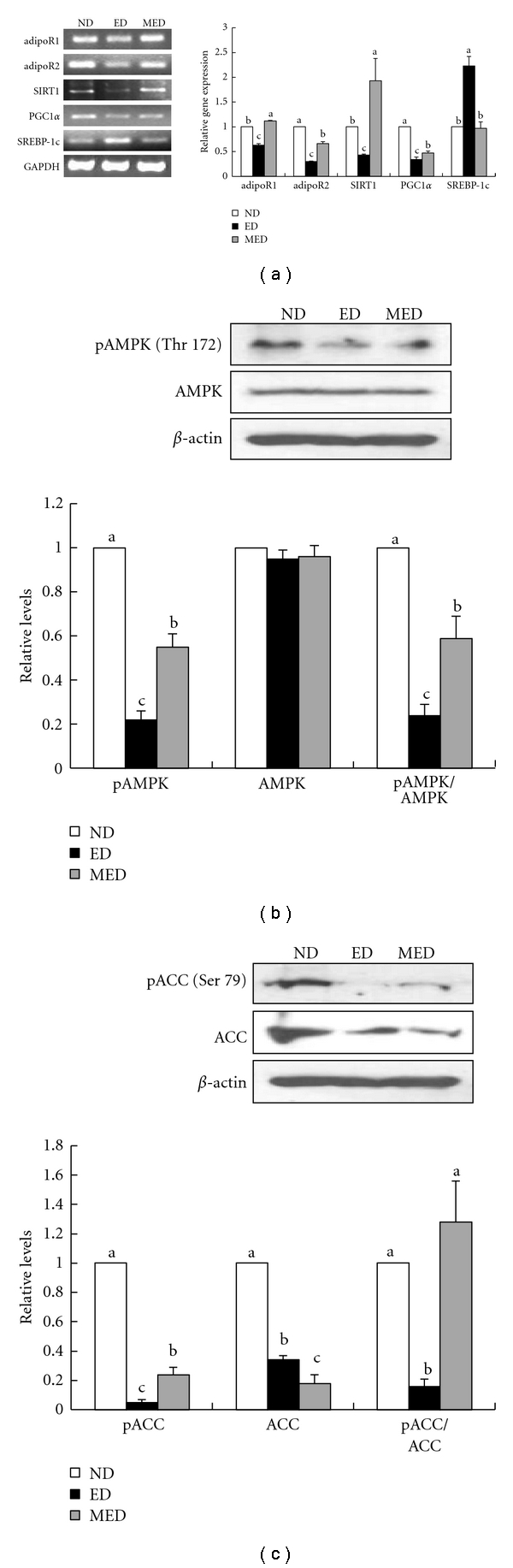

3.4. Regulation of Adiponectin Receptor-Mediated Signaling Molecules

Chronic ethanol ingestion led to more significant decreases in the hepatic expression of the adipoR1 and adipoR2 genes than in the ND mice, and MED feeding significantly restored these ethanol-induced changes in the adiponectin receptor genes. Similarly, the MED feeding significantly reversed the marked decreases in the mRNA levels of the hepatic SIRT1 and PGC1α, which were induced by ethanol feeding. In addition, the MED efficiently counteracted the ethanol-induced upregulation of the SREBP-1c gene (higher 57% reduction than in the ED mice, P < 0.05) (Figure 3). The MED significantly blunted the downregulation of the phospho-AMPK/total AMPK (146% increase) ratio and of the phospho-ACC/total ACC ratio (700% increase), which were caused by chronic ethanol ingestion, in the livers of the mice (Figures 3(b) and 3(c)).

Figure 3.

Alcohol-induced liver adiponectin receptors and involved genes in mRNA or protein expression. (a) The left panel shows the results of the RT-PCR analysis of adipoR1, adipoR2, SRIT1, PGC1α, and SREBP-1c expressions. The images show the representative agarose gel electrophoresis of the PCR products. The right panel shows the relative expressions of the adipoR1, adipoR2, SRIT1, PGC1α, and SREBP-1c levels. The data were normalized to the GAPDH levels, and all the expression levels that are shown are relative to the ND. (b) The upper panel shows the results of the Western blot analysis of the phosphorylated and total AMPK. The images show representative Western blotting images. The bottom panel shows the relative expressions of those levels and the ratios of the phosphorylated protein level to the total protein level. (c) The upper panel shows the results of the Western blot analysis of the phosphorylated and total ACC. The images show representative Western blotting images. The bottom panel shows the relative expressions of those levels and the ratios of the phosphorylated protein level to the total protein level. These results represent the means ± SEM of the three independent experiments in which RNA or protein samples from eight mice were used. a,b,cMeans not sharing a common letter are significantly different (P < 0.05).

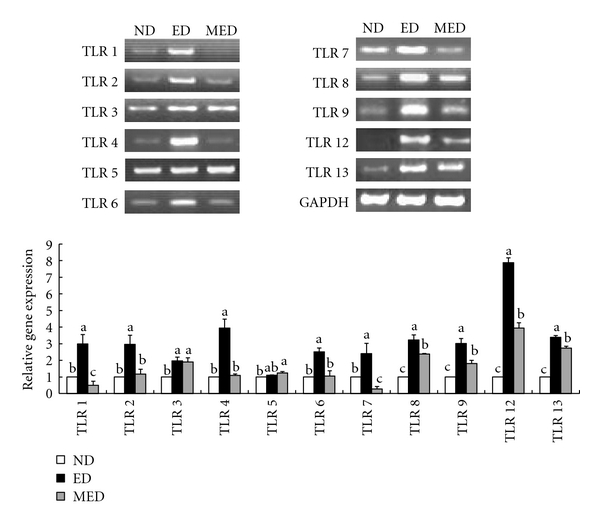

3.5. Regulation of TLRs-Mediated Signaling Molecules

The hepatic expression of the TLR mRNAs was measured after nine weeks of ethanol exposure. More significant increases in the TLR1, TLR2, TLR3, TLR4, TLR6, TLR7, TLR8, TLR9, TLR12, and TLR13 mRNA levels were observed in the livers of the ethanol-fed control mice than of the pair fed ND mice. The MED significantly alleviated the ethanol-induced upregulation of the hepatic TLR1, TLR2, TLR4, TLR6, TLR7, TLR8, TLR9, TLR12, and TLR13 gene expressions. The hepatic TLR3, which was upregulated by the ethanol feeding, and the hepatic TLR5, which was unaffected by the ethanol feeding, did not respond to the MED feeding (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Alcohol-induced liver TLR mRNA expression. The upper panel shows the results of the RT-PCR analysis of the TLR1~9, 12, and 13 expressions. The images show the representative agarose gel electrophoresis of the PCR products. The bottom panel shows the relative expressions of the TLR1~9, 12, and 13 levels. The data were normalized to the GAPDH levels, and all the expression levels that are shown are relative to the ND. The results that are shown represent the means ± SEM of the three independent experiments in which RNA samples from eight mice were used. a, b, cMeans not sharing a common letter are significantly different (P < 0.05).

After endotoxin bound itself to the LPS-binding protein (LBP), it associates in the portal blood with the CD14 prior to its binding to TLR4 and all the TLRs that were recruited by MyD88, MAL, TRIF, and TRAF6 for their proinflammatory signaling. The mRNA levels of the LBP and CD14, as well as of the adaptor molecules of the TLRs (MyD88, MAL, TRIF, and TRAF6), all more significantly increased in the livers of the ED mice than of the ND mice, whereas the MED feeding led to more significant decreases in the hepatic mRNA levels of the LBP, CD14, MyD88, MAL, TRIF, and TRAF6 than in the ED mice (Figure 5(a)). Among the extremely significant recent discoveries on TLR signaling is that the MyD88-dependent pathway also activates some IRFs, such as IRF1, 3, 5, and 7. In this study, the mRNA levels of the IRF1, 3, 5, and 7 genes more significantly increased in the livers of the ED mice than of the ND mice and these ethanol-induced upregulations of the hepatic IRFs were significantly reversed by the MED feeding (Figure 5(b)). The RT-PCR analysis of the hepatic mRNAs of NFκB (p50 and p65) and of its target cytokine genes such as TNFα, IL-6, IFNα, IFNβ, IL-12-p40, and CXCL2 was performed next. The MED feeding significantly downregulated the expressions of the p50, p65, TNFα, IL-6, IFNα, IFNβ, IL-12-p40, and CXCL2 genes compared to the ED mice (Figure 5(c)).

Figure 5.

mRNA expressions of the hepatic genes that were involved in the inflammation. The left panel shows the results of the RT-PCR analysis of the (a) LBP, CD14, MyD88, MAL, TRIF, and TRAF6, (b) IRF1, IRF3, IRF5, and IRF7, and (c) p50, p65, TNFα, IL-6, IFNα, IFNβ, IL-12-p40, and CXCL2 expressions. The images show the representative agarose gel electrophoresis of the PCR products. The right panel shows the relative expressions of the (a) LBP, CD14, MyD88, MAL, TRIF, and TRAF6, (b) IRF1, IRF3, IRF5, and IRF7, and (c) p50, p65, TNFα, IL-6, IFNα, IFNβ, IL-12-p40, and CXCL2 levels. The data were normalized to the GAPDH levels, and all the expression levels that are shown are relative to the ND. The results that are shown represent the means ± SEM of the three independent experiments in which RNA samples from eight mice were used. a, b, cMeans not sharing a common letter are significantly different (P < 0.05).

4. Discussion

The authors' previous study showed that the supplementation of the Lieber-DeCarli ethanol diet with C. lanceolata water extract (5 mg/L of a liquid diet) showed a significant improvement in the amount of weight that was gained and in the hepatic lipid levels (in the press). In this study, the effects of three different fractions of C. lanceolata roots, which were prepared using different solvents, on the protection from alcoholic fatty liver were tested. Several studies have demonstrated that the protective effects of various plant extracts from alcoholic liver injury in animals, such as of fenugreek seed (Trigonella foenum fraecum) methanol extract [32], and hot water extracts of avaram leaves (Cassia auriculata) [33] and green tea (Camellia sinensis) [34] were manifested at dosages of between 200 and 500 mg/kg of body weight. Based on these studies, C. lanceolata root fractions were added to a liquid diet at 0.091% (wt/v), which is equivalent to a daily intake of 300 mg/kg of body weight, assuming that a mouse weighs 30 g and consumes 10 ml of a liquid diet per day.

Among the three different fractions that were prepared from the C. lanceolata root, CME exhibited the most remarkable attenuation of alcohol-induced fatty liver in terms of various parameters. For example, CME more significantly reduced the serum ALT and AST activities and the hepatic FFA concentration in the mice that were fed ethanol than did CES or CEP. Besides, alcohol-induced body weight loss and hepatic accumulations of triglycerides and cholesterol more significantly improved in mice that were supplemented with CME than in animals that were supplemented with ESD or EPD, although the difference was statistically insignificant. Therefore, CME appeared to be the most potent, among the fractions that were obtained from the C. lanceolata root, in protecting animals from alcohol-induced hepatic accumulation of lipids. Further investigated were the underlying mechanisms of CME against hepatic steatosis induced by chronic ethanol administration. The ethanol-induced elevation of the plasma HDL cholesterol concentration, as observed in the current study, has been suggested as a cardioprotective response in animals chronically loaded with ethanol [35]. The elevated HDL concentration and the reduced LDL concentration, which are characteristic of the lipoprotein pattern in chronic alcoholics, could well explain the reduced risk of coronary heart disease in alcoholics [36].

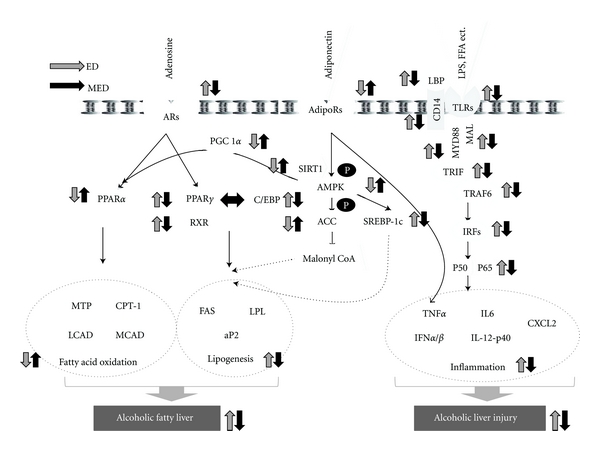

In this present study, the mRNA expression of the hepatic A2BR and A1R was markedly elevated by chronic ethanol feeding. Furthermore, the expression of PPARα and of its target genes, such as CPT-1, MTP, LCAD, and MCAD, all significantly decreased, whereas the expression of PPARγ and of its target genes, such as RXR, C/EBP, LPL, aP2, and FAS, all significantly increased in the livers of the ethanol-fed ED mice than of the ND mice (Figure 6). These results are in accordance with recent findings from experiments with mice that adenosine generated by ethanol metabolism plays an important role in ethanol-induced hepatic steatosis via A1R and A2BR, which leads to the upregulation of PPARγ and the downregulation of PPARα, respectively [1]. It was observed that CME supplementation reversed ethanol-induced elevation of the expressions of A2BR, A1R, PPARγ, and their target genes in the liver tissues of mice. These results suggest that CME ameliorates hepatic steatosis in mice, at least partly by modulating adenosine-receptor-mediated signaling molecules that are responsible for fatty acid oxidation and lipogenesis.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram illustrating the antilipogenic and anti-inflammatory activities of Codonopsis lanceolata in the liver of mice with chronic ethanol consumption. Adapted from Peng [1], You and Rogers [37, 51]. The arrows denote the direction of the responses to altered conditions with ED feeding relative to ND feeding (gray arrows), and with MED feeding relative to ED feeding (black arrows).

Adiponectin stimulates hepatic AMPK, which, in turn, phosphorylates ACC on Ser-79 and attenuates ACC activity. Inhibition of ACC directly reduces lipid synthesis and indirectly enhances fatty acid oxidation by blocking the production of malonyl-CoA, an allosteric inhibitor of CPT-1 [37]. Activation of AMPK by adiponectin in the liver also leads to decreased mRNA and protein expression of SREBP-1c [38–41], which results in decreased hepatic lipid synthesis. Adiponectin is also known to stimulate the activities of both PGC1α and PPARα, which mainly control the transcription of a panel of genes that encode fatty acid oxidation enzymes [42, 43]. As a result, adiponectin-mediated AMPK activation favors lipid catabolism and opposes lipid deposition in the liver [44–49]. Chronic ethanol administration is known to significantly decrease the plasma adiponectin level in mice [50]. In this study, more significant decreases in the mRNA levels of AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 were observed in the livers of the ED mice than of the pair fed ND mice. These alcohol-induced reductions in the hepatic AdipoRs expression appear to have been associated with the subsequent decreases in the phosphorylation of AMPK and ACC as their phosphorylations in the liver more significantly decreased in the ED mice than in the ND mice (Figure 6).

Besides, the hepatic mRNA levels of SIRT1, PGC1α, SREBP-1c, PPARα, and CPT1 were also more significantly reduced in the ED mice than in the ND mice (Figure 6). SIRT1 has been gaining recognition as one of the critical agents in the mediation of adiponectin signaling to AMPK [37], which is the central mechanism in the regulation of lipid metabolism [52–55]. Although PGC1α was initially identified as a coactivator of PPARγ, it has subsequently been shown to serve as a cofactor of several other transcription factors, including PPARα [56, 57]. Treatment with adiponectin restored the ethanol-inhibited PGC1α/PPARα activity in cultured hepatic cells and in animal livers, which suggests that the stimulation of adiponectin-SIRT1 signaling may serve as an effective therapeutic strategy for treating or preventing human alcoholic fatty liver [38–40]. In this study, CME significantly restored the ethanol-induced downregulation of adiponectin-mediated signaling molecules, including adipoR1, adipoR2, pAMPK/AMPK, pACC/ACC, SIRT1, and PGC1α, which led to increased fatty acid oxidation and decreased lipogenesis in the livers of the mice.

It was recently shown that innate immune cells recognize conserved pathogen-associated molecular patterns through pattern recognition receptors, among which the family of TLRs occupies an important place [24]. LBP, which is present in normal serum, recognizes and binds to LPS with high affinity through its lipid moiety [58, 59]. LPS-LBP complexes then activate cells through the second glycoprotein, the membrane-bound CD14, to produce inflammatory mediators [60–62] in the presence of only a functional TLR4 [63]. Although LPS was not detected in the blood, more significant increases in the mRNA levels of LBP and CD14 were observed in the livers of the ED mice than of the ND mice (Figure 6). TLRs have a TIR domain that initiates the signaling cascade through TIR adapters, such as MyD88 [64], Mal [65, 66], and TRIF, which interact with TRAF6, the downstream adaptor. TRAF6 activates the IRFs, which leads to NF-κB activation and induction of the expressions of proinflammatory cytokines [67], such as of TNFα, IL-6, IFNα, and IFNβ.

It was demonstrated that chronic ethanol feeding induces hepatic steatosis and clear upregulation of TLR1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 12, and 13 in the liver. These findings are supported by previous reports that ethanol-fed mice exhibited hepatic inflammation that was dependent on the upregulation of multiple TLRs in the liver [24]. The expressions of the MyD88, MAL, TRIF, TRAF6, IRF1, 3, 5, and 7 genes, along with the mRNA levels of NFκB and proinflammatory cytokines, were all more significantly elevated in the livers of the ED mice than of the ND mice (Figure 6). These results are also in accordance with previous observations that MyD88 is required for the development of fibrosis [68], a predisposing condition for hepatocellular cancer development, and that IRF7 expression more significantly increased in the livers of alcohol-fed MyD88-deficient mice than of pair fed control mice [69]. These results suggest that chronic ethanol intake may activate TLR-mediated proinflammatory signaling cascades. The study data show that these hepatic inductions of TLR-mediated signaling cascade molecules, which involve both MyD88-dependent and -independent pathways, along with their target proinflammatory cytokine genes, such as TNFα, IL-6, IFNα, IFNβ, IL-12-p40, and CSCL2, due to ethanol feeding were all dramatically reversed with CME supplementation.

Taken together, these beneficial effects of CME against alcoholic fatty livers in mice appear to have occurred with adenosine- and adiponectin-mediated regulations of hepatic steatosis and TLR-mediated modulation of hepatic proinflammatory responses, since ethanol-induced changes in the expression of the molecules that are involved in these three signaling pathways were all significantly reversed with CME feeding. Although alcoholic fatty liver is a major risk factor for advanced liver injuries such as steatohepatitis, fibrosis, and cirrhosis [51], previous studies have mostly focused on the antilipogenic or -inflammatory activity alone, but not in combination, of a compound and extracts. For example, Kumar et al. evaluated the effect of the Cassia auriculata leaf extract on lipid metabolism in alcohol-induced hepatic steatosis [33]. Resveratrol prevents the development of hepatic steatosis induced by alcohol, by restoring the inhibited hepatic SIRT1-AMPK signaling system [70]. This study demonstrated that both lipogenesis and inflammation are associated with the development of alcoholic fatty liver and that CME has both antilipogenic and anti-inflammatory effects through coordinated multiple signaling pathways. Although much further study is required concerning the exact identities of the chemical constituents of the C. lanceolata methanol extract that are responsible for the findings described herein, the results of this study provide some insights on the basic mechanism that underlies the therapeutic effect of the extract on mice hepatic tissues after chronic ethanol feeding.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1: List of primer sequences and PCR conditions.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the BioGreen 21 Program of the Rural Development Administration (Code no. 20080401034049) and in part by a grant of the Korea Healthcare Technology R&D Project, Ministry for Health & Welfare Affairs (Code no. A085136) of the Republic of Korea.

References

- 1.Peng Z, Borea PA, Varani K, et al. Adenosine signaling contributes to ethanol-induced fatty liver in mice. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2009;119(3):582–594. doi: 10.1172/JCI37409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crabb DW. Recent developments in alcoholism: the liver. Recent Developments in Alcoholism. 1993;11:207–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crabb DW, Liangpunsakul S. Alcohol and lipid metabolism. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2006;21(supplement 3):S56–S60. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsukamoto H, She H, Hazra S, Cheng J, Wang J. Fat paradox of steatohepatitis. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2008;23(supplement 1):S104–S107. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fischer M, You M, Matsumoto M, Crabb DW. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) agonist treatment reverses PPARα dysfunction and abnormalities in hepatic lipid metabolism in ethanol-fed mice. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(30):7997–8004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302140200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gavrilova O, Haluzik M, Matsusue K, et al. Liver peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ contributes to hepatic steatosis, triglyceride clearance, and regulation of body fat mass. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(36):34268–34276. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300043200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nagy LE, Diamond I, Casso DJ, Franklin C, Gordon AS. Ethanol increases extracellular adenosine by inhibiting adenosine uptake via the nucleoside transporter. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1990;265(4):1946–1951. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Puig JG, Fox IH. Ethanol-induced activation of adenine nucleotide turnover. Evidence for a role of acetate. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1984;74(3):936–941. doi: 10.1172/JCI111512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagy LE. Ethanol metabolism and inhibition of nucleoside uptake lead to increased extracellular adenosine in hepatocytes. American Journal of Physiology. 1992;262(5):C1175–C1180. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1992.262.5.C1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan ES, Montesinos MC, Fernandez P, et al. Adenosine A2A receptors play a role in the pathogenesis of hepatic cirrhosis. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2006;148(8):1144–1155. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peng Z, Fernandez P, Wilder T, et al. Ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) -mediated extracellular adenosine production plays a critical role in hepatic fibrosis. FASEB Journal. 2008;22(7):2263–2272. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-100685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fredholm BB. Adenosine, an endogenous distress signal, modulates tissue damage and repair. Cell Death and Differentiation. 2007;14(7):1315–1323. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guinzberg R, Laguna I, Zentella A, Guzman R, Piña E. Effect of adenosine and inosine on ureagenesis in hepatocytes. Biochemical Journal. 1987;245(2):371–374. doi: 10.1042/bj2450371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guinzberg R, Diaz-Cruz A, Uribe S, Pina E. Inhibition of adenosine mediated responses in isolated hepatocytes by depolarizing concentrations of K+ Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1993;197(1):229–234. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tinton SA, Lefebvre VH, Cousin OC, Buc-Calderon PM. Cytolytic effects and biochemical changes induced by extracellular ATP to isolated hepatocytes. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1993;1176(1-2):1–6. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(93)90169-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonzalez-Benitez E, Guinzberg R, Diaz-Cruz A, Pina E. Regulation of glycogen metabolism in hepatocytes through adenosine receptors. Role of Ca2+ and cAMP. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2002;437(3):105–111. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01299-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dhalla AK, Santikul M, Smith M, Wong MY, Shryock JC, Belardinelli L. Antilipolytic activity of a novel partial A1 adenosine receptor agonist devoid of cardiovascular effects: comparison with nicotinic acid. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2007;321(1):327–333. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.114421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dhalla AK, Wong MY, Voshol PJ, Belardinelli L, Reaven GM. A1 adenosine receptor partial agonist lowers plasma FFA and improves insulin resistance induced by high-fat diet in rodents. American Journal of Physiology. 2007;292(5):E1358–E1363. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00573.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klaasse EC, Ijzerman AP, de Grip WJ, Beukers MW. Internalization and desensitization of adenosine receptors. Purinergic Signalling. 2008;4(1):21–37. doi: 10.1007/s11302-007-9086-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhagwandeen BS, Apte M, Manwarring L, Dickeson J. Endotoxin induced hepatic necrosis in rats on an alcohol diet. Journal of Pathology. 1987;152(1):47–53. doi: 10.1002/path.1711520107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang SQ, Lin HZ, Lane MD, Clemens M, Diehl AM. Obesity increases sensitivity to endotoxin liver injury: implications for the pathogenesis of steatohepatitis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94(6):2557–2562. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diehl AM. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: implications for alcoholic liver disease pathogenesis. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2001;25(5, supplement ISBRA):8S–14S. doi: 10.1097/00000374-200105051-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cubero FJ, Nieto N. Kupffer cells and alcoholic liver disease. Revista Espanola de Enfermedades Digestivas. 2006;98(6):460–472. doi: 10.4321/s1130-01082006000600007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gustot T, Lemmers A, Moreno C, et al. Differential liver sensitization to Toll-like receptor pathways in mice with alcoholic fatty liver. Hepatology. 2006;43(5):989–1000. doi: 10.1002/hep.21138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guo WL, Gong L, Ding ZF, et al. Genomic instability in phenotypically normal regenerants of medicinal plant Codonopsis lanceolata benth. et hook. f., as revealed by ISSR and RAPD markers. Plant Cell Reports. 2006;25(9):896–906. doi: 10.1007/s00299-006-0131-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee KT, Choi J, Jung WT, Nam JH, Jung HJ, Park HJ. Structure of a new echinocystic acid bisdesmoside isolated from Codonopsis lanceolata roots and the cytotoxic activity of prosapogenins. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2002;50(15):4190–4193. doi: 10.1021/jf011647l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee KW, Jung HJ, Park HJ, Kim DG, Lee JY, Lee KT. β-D-xylopyranosyl-(1 → 3)-β-D-glucuronopyranosyl echinocystic acid isolated from the roots of Codonopsis lanceolata induces caspase-dependent apoptosis in human acute promyelocytic leukemia HL-60 cells. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2005;28(5):854–859. doi: 10.1248/bpb.28.854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee YG, Kim JY, Lee JY, et al. Regulatory effects of Codonopsis lanceolata on macrophage-mediated immune responses. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2007;112(1):180–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Han EG, Moon HG, Cho SY. Effect of Codonopsis lanceolata water extract on the levels of lipid in rats fed high fat diet. Journal of the Korean Society of Food Science and Nutrition. 1998;27:940–944. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lieber CS, DeCarli LM, Sorrell MF. Experimental methods of ethanol administration. Hepatology. 1989;10(4):501–510. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840100417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Folch J, Lees M, Stanley GHS. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1957;226(1):497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaviarasan S, Viswanathan P, Anuradha CV. Fenugreek seed (Trigonella foenum graecum) polyphenols inhibit ethanol-induced collagen and lipid accumulation in rat liver. Cell Biology and Toxicology. 2007;23(6):373–383. doi: 10.1007/s10565-007-9000-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kumar RS, Ponmozhi M, Viswanathan P, Nalini N. Effect of Cassia auriculata leaf extract on lipids in rats with alcoholic liver injury. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2002;11(2):157–163. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-6047.2002.00286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arteel GE, Uesugi T, Bevan LN, et al. Green tea extract protects against early alcohol-induced liver injury in rats. Biological Chemistry. 2002;383(3-4):663–670. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Emeson EE, Vlasios M, Todd S, Majid T. Chronic alcohol feeding inhibits atherogenesis in C57BL/6 hyperlipidemic mice. American Journal of Pathology. 1995;147(6):1749–1758. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Szabo G. Consequences of alcohol consumption on host defence. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 1999;34(6):830–841. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/34.6.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rogers CQ, Ajmo JM, You M. Adiponectin and alcoholic fatty liver disease. IUBMB Life. 2008;60(12):790–797. doi: 10.1002/iub.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shklyaev S, Aslanidi G, Tennant M, et al. Sustained peripheral expression of transgene adiponectin offsets the development of diet-induced obesity in rats. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(2):14217–14222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2333912100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamauchi T, Nio Y, Maki T, et al. Targeted disruption of AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 causes abrogation of adiponectin binding and metabolic actions. Nature Medicine. 2007;13(3):332–339. doi: 10.1038/nm1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamauchi T, Kamon J, Ito Y, et al. Cloning of adiponectin receptors that mediate antidiabetic metabolic effects. Nature. 2003;423(6941):762–769. doi: 10.1038/nature01705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mao X, Kikani CK, Riojas RA, et al. APPL1 binds to adiponectin receptors and mediates adiponectin signalling and function. Nature Cell Biology. 2006;8(5):516–523. doi: 10.1038/ncb1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.You M, Considine RV, Leone TC, Kelly DP, Crabb DW. Role of adiponectin in the protective action of dietary saturated fat against alcoholic fatty liver in mice. Hepatology. 2005;42(3):568–577. doi: 10.1002/hep.20821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jay MA, Ren J. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) in metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Current Diabetes Reviews. 2007;3(1):33–39. doi: 10.2174/157339907779802067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kadowaki T, Yamauchi T, Kubota N. The physiological and pathophysiological role of adiponectin and adiponectin receptors in the peripheral tissues and CNS. FEBS Letters. 2008;582(1):74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.11.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kadowaki T, Yamauchi T, Kubota N, Hara K, Ueki K, Tobe K. Adiponectin and adiponectin receptors in insulin resistance, diabetes, and the metabolic syndrome. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2006;116(7):1784–1792. doi: 10.1172/JCI29126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kadowaki T, Yamauchi T. Adiponectin and adiponectin receptors. Endocrine Reviews. 2005;26(3):439–451. doi: 10.1210/er.2005-0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Méndez-Sánchez N, Chavez-Tapia NC, Zamora-Valdés D, Uribe M. Adiponectin, structure, function and pathophysiological implications in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Mini-Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry. 2006;6(6):651–656. doi: 10.2174/138955706777435689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Misra P. AMP activated protein kinase: a next generation target for total metabolic control. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets. 2008;12(1):91–100. doi: 10.1517/14728222.12.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Browning JD, Horton JD. Molecular mediators of hepatic steatosis and liver injury. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2004;114(2):147–152. doi: 10.1172/JCI22422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xu A, Wang Y, Keshaw H, Xu LY, Lam KS, Cooper GJ. The fat-derived hormone adiponectin alleviates alcoholic and nonalcoholic fatty liver diseases in mice. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2003;112(1):91–100. doi: 10.1172/JCI17797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.You M, Rogers CQ. Adiponectin: a key adipokine in alcoholic fatty liver. Experimental Biology and Medicine. 2009;234(8):850–859. doi: 10.3181/0902-MR-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hou X, Xu S, Maitland-Toolan KA, et al. SIRT1 regulates hepatocyte lipid metabolism through activating AMP-activated protein kinase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283(29):20015–20026. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802187200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lan F, Cacicedo JM, Ruderman N, Ido Y. SIRT1 modulation of the acetylation status, cytosolic localization, and activity of LKB1: possible role in AMP-activated protein kinase activation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283(41):27628–27635. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805711200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Suchankova G, Nelson LE, Gerhart-Hines Z, et al. Concurrent regulation of AMP-activated protein kinase and SIRT1 in mammalian cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2009;378(4):836–841. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.11.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fulco M, Sartorelli V. Comparing and contrasting the roles of AMPK and SIRT1 in metabolic tissues. Cell Cycle. 2008;7(23):3669–3679. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.23.7164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Puigserver P, Spiegelman BM. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator 1α (PGC-1 α): transcriptional coactivator and metabolic regulator. Endocrine Reviews. 2003;24(1):78–90. doi: 10.1210/er.2002-0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vega RB, Huss JM, Kelly DP. The coactivator PGC-1 cooperates with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α in transcriptional control of nuclear genes encoding mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation enzymes. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2000;20(5):1868–1876. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.5.1868-1876.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schumann RR, Leong SR, Flaggs GW, et al. Structure and function of lipopolysaccharide binding protein. Science. 1990;249(4975):1429–1431. doi: 10.1126/science.2402637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Su GL, Simmons RL, Wang SC. Lipopolysaccharide binding protein participation in cellular activation by LPS. Critical Reviews in Immunology. 1995;15(3-4):201–214. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v15.i3-4.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ulevitch RJ, Tobias PS. Receptor-dependent mechanisms of cell stimulation by bacterial endotoxin. Annual Review of Immunology. 1995;13:437–457. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.002253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Martin TR, Mongovin SM, Tobias PS, et al. The CD14 differentiation antigen mediates the development of endotoxin responsiveness during differentiation of mononuclear phagocytes. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 1994;56(1):1–9. doi: 10.1002/jlb.56.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wright SD, Ramos RA, Tobias PS, Ulevitch RJ, Mathison JC. CD14, a receptor for complexes of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and LPS binding protein. Science. 1990;249(4975):1431–1433. doi: 10.1126/science.1698311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Su GL, Klein RD, Aminlari A, et al. Kupffer cell activation by lipopolysaccharide in rats: role for lipopolysaccharide binding protein and Toll-like receptor 4. Hepatology. 2000;31(4):932–936. doi: 10.1053/he.2000.5634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Medzhitov R, Preston-Hurlburt P, Kopp E, et al. MyD88 is an adaptor protein in the hToll/IL-1 receptor family signaling pathways. Molecular Cell. 1998;2(2):253–258. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80136-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fitzgerald KA, Palsson-Mcdermott EM, Bowie AG, et al. Mal (MyD88-adapter-like) is required for Toll-like recepfor-4 signal transduction. Nature. 2001;413(6851):78–83. doi: 10.1038/35092578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Horng T, Barton GM, Medzhitov R. TIRAP: an adapter molecule in the Toll signaling pathway. Nature Immunology. 2001;2(9):835–841. doi: 10.1038/ni0901-835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Takaoka A, Yanai H, Kondo S, et al. Integral role of IRF-5 in the gene induction programme activated by Toll-like receptors. Nature. 2005;434(2):243–249. doi: 10.1038/nature03308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Seki E, de Minicis S, Österreicher CH, et al. TLR4 enhances TGF-β signaling and hepatic fibrosis. Nature Medicine. 2007;13(11):1324–1332. doi: 10.1038/nm1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hritz I, Mandrekar P, Velayudham A, et al. The critical role of Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 in alcoholic liver disease is independent of the common TLR adapter MyD88. Hepatology. 2008;48(4):1224–1231. doi: 10.1002/hep.22470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ajmo JM, Liang X, Rogers CQ, Pennock B, You M. Resveratrol alleviates alcoholic fatty liver in mice. American Journal of Physiology. 2008;295(4):G833–G842. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90358.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1: List of primer sequences and PCR conditions.