Abstract

The α5β1 integrin heterodimer regulates many processes that contribute to embryonic development and angiogenesis, in both physiological and pathological contexts. As one of the major adhesion complexes on endothelial cells, it plays a vital role in adhesion and migration along the extracellular matrix. We recently showed that angiogenesis is modulated by syntaxin 6, a Golgi- and endosome-localized t-SNARE, and that it does so by regulating the post-Golgi trafficking of VEGFR2. Here we show that syntaxin 6 is also required for α5β1 integrin-mediated adhesion of endothelial cells to, and migration along, fibronectin. We demonstrate that syntaxin 6 and α5β1 integrin colocalize in EEA1-containing early endosomes, and that functional inhibition of syntaxin 6 leads to misrouting of β1 integrin to the degradation pathway (late endosomes and lysosomes) rather transport along recycling pathway from early endosomes; an increase in the pool of ubiquitinylated α5 integrin and its lysosome-dependent degradation; reduced cell spreading on fibronectin; decreased Rac1 activation; and altered Rac1 localization. Collectively, our data show that functional syntaxin 6 is required for the regulation of α5β1-mediated endothelial cell movement on fibronectin. These syntaxin 6-regulated membrane trafficking events control outside-in signaling via haptotactic and chemotactic mechanisms.

Keywords: Adhesion, Cell Migration, Endosomes, Integrin, Intracellular Trafficking, Endothelial Cells, Syntaxin 6, α5β1 Integrin, Angiogenesis

Introduction

Adhesion molecules present on the endothelial cell (EC)2 surface are vital regulators of vascular homeostasis and angiogenesis. Integrins are heterodimeric cell-adhesion receptors for extracellular matrix proteins, and are composed of noncovalently bound α and β subunits (1). During embryonic vascular development, as well as during tumor angiogenesis, the extracellular matrix protein fibronectin serves as an adhesive support and signals through α5β1 integrin to regulate the spreading, migration, and contractility of ECs (1–3). Integrins do not have intrinsic enzymatic activity; their ability to transduce signals depends on recruitment of cytoplasmic linker and signaling proteins, and on the assembly of focal adhesions. Hence the processes that regulate integrin turnover at the cell surface may have implications for the regulation of angiogenesis in the context of therapies.

The levels of α5β1 integrin on the cell surface are maintained by recycling of endocytosed complexes back to the plasma membrane (PM). Internalization of the α5β1 integrin complexes occurs via both clathrin-dependent and clathrin-independent endocytic pathways (4). Subsequently, these complexes traffic to early endosomes (EEs) and then to the perinuclear recycling compartment, from which they are recycled to the PM (5–7). This transport requires Rab11 and the activity of PKB/GSK3b (5). Binding of fibronectin to the α5β1 integrin triggers endocytosis that does not involve integrin recycling; in this case the integrin complexes move from the EEs into the multivesicular endosomes for degradation (8). This phenomenon highlights the importance of α5β1 integrin trafficking at the EE compartment in regulating integrin levels at the PM.

Members of the SNARE family of proteins participate in vesicular fusion events during the intracellular transport of cargo molecules from a donor vesicle to a target membrane along the endocytic and secretory transport pathways (9, 10). As each SNARE has a precise subcellular distribution, it has been suggested that selective interactions between SNAREs contribute to the specificity of membrane exchanges between intracellular compartments. This concept has been documented by in vitro and permeabilized cell studies (11, 12). SNAREs are operationally divided into two groups: those found primarily on the transport vesicle, known as v-SNAREs (or VAMPs), and those found primarily on the target membrane, called t-SNAREs (syntaxins and SNAPs) (9, 10). The demonstration that VAMPs and SNAPs are involved in α5β1 integrin trafficking suggested that SNARE proteins more generally play roles in the regulation of integrin trafficking (6, 13–16). Recently, we showed that the functional t-SNARE syntaxin 6 is required for the post-Golgi trafficking of VEGFR2/KDR/Flk-1 in vitro, and for VEGF-induced angiogenesis both in vitro and in vivo (17).

In epithelial cells and fibroblasts, syntaxin 6 localizes not only to the Golgi apparatus, but also to EEs, where it interacts with early endosome antigen 1 (EEA1) (17–20). The EE is one of the major vesicular compartments from which integrins are sorted into the recycling and degradative (endo-lysosomal) pathways (8, 21). In the current study, we show that syntaxin 6 is present at the EEs within human ECs, and that it colocalizes with α5β1 integrin at these locations. We investigated the possibility that EE-localized syntaxin 6 regulates endocytic sorting of α5β1 integrin complexes and, thereby, surface integrin-mediated EC migration. We found that when syntaxin 6 function was inhibited, EC adhesion to fibronectin was decreased. Consistent with these findings, trafficking of α5β1 integrin complexes from the EEs to the PM was impaired, and more of the complexes were transported to the late endosomes (LEs) and lysosomes for degradation. As a result of the decrease in PM levels of α5β1 integrin, the integrin-dependent signaling associated with cell spreading and migration was severely compromised. Our results demonstrate, for the first time, that syntaxin 6 regulates the movement of ECs along fibronectin by facilitating endocytic, PM-targeted sorting of the α5β1 integrin complex.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

The antibodies (Ab) used in this study were obtained from the following companies and institutions: the anti-β1 integrin mouse monoclonal antibody (mAb; MAB1981) and anti-α5 rabbit polyclonal Ab (AB1928) used in immunofluorescence assays, Millipore-Chemicon; the anti-syntaxin 6 (610636) and anti-β1 integrin (for immunoblotting) mAbs, BD Transduction Laboratories (NJ); the P5D2 mAb against human β1-integrin developed by Dr. Elizabeth A. Wayner (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center), the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank developed under the auspices of the NICHD and maintained by The University of Iowa; Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies, Invitrogen and Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR); FITC-conjugated secondary antibodies, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.; anti-integrin β1 (clone P4C10) and anti-integrin β3 (clone B3A) mAbs for blocking, Chemicon (Millipore, MA); heterodimeric antibodies against αvβ3 (clone LM609) and α5β1 (clone JBS5), Chemicon International (Temecula, CA); and mouse anti-human CD29 mAb (clone HUTS-21) and anti-focal adhesion kinase (FAK) mouse mAb, BD Biosciences (San Diego, CA).

SuperSignal West Femto chemiluminescence reagents were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. FuGENE 6 transfection reagent was obtained from Roche Diagnostics. Matrices such as rat tail Collagen type I, fibronectin, and vitronectin were obtained from BD Biosciences, whereas Laminin-1 (from Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm mouse sarcoma) was procured from Sigma. The MTT assay kit (30-1010K) was obtained from ATCC. Vectashield mounting medium was obtained from Vector Laboratories, Inc. (CA). All other reagents were purchased from Sigma, unless stated otherwise. The plasmid encoding, lgp120 fused to GFP (GFP-lgp120) was provided by Dr. Jennifer Lippincott-Schwartz (NIH) (22), HA-tagged ubiquitin was a gift from Dr. Peter Snyder (University of Iowa), and α5-integrin fused to GFP (α5-GFP-integrin) was kindly provided by Dr. Alan F. Horwitz (University of Virginia) (23).

Cell Culture

Primary human umbilical vein ECs (HUVECs) were obtained from Lonza (Walkersville, MD), and cultures were maintained on collagen-coated plates in complete medium (endothelial-cell basal medium containing supplements from Lonza). HUVECs were used only between passages 3 and 7. Most of the experiments were carried out with HUVECs cultured on fibronectin (10 μg/ml)-coated surfaces.

Adenoviral Infections, siRNAs

Recombinant adenoviruses expressing the cytosolic domains of syntaxin 6 and syntaxin 16 (designated syntaxin 6-cyto and syntaxin 16-cyto, respectively) were used as described previously (17, 19). Except as noted, cells were infected with the indicated adenovirus (titer ∼1.5 × 107 pfu/ml), at a multiplicity of infection of 1:75, in serum-free culture medium. The virus-containing medium was replaced 12 h later with normal medium supplemented with 10% FBS. The cells were used in experiments 12–24 h later.

RNAi-mediated knockdown was performed using Silencer Select pre-designed siRNAs against human syntaxin 6 (siSTX6; 5′-GCAACUGAAUUGAGUAUAA-3′) and human syntaxin 16 (siSTX16; 5′-CAGCGAUUGGUGUGACAAA-3′), as described previously (17). HUVECs were electroporated with STX6- or STX16-specific siRNA oligonucleotides, using the HUVEC Nucleofector Kit (Ambion, Inc., Austin, TX) and the protocols recommended by Amaxa Biosystems (Gaithersburg, MD). The extent of protein knockdown was determined by immunoblotting and immunofluorescence assay 72 h after electroporation.

Adhesion Assay

24-well cell culture dishes were coated with 10 μg/ml of collagen (heterotrimer composed of two α1 chains and one α2 chain), fibronectin, vitronectin, and laminin-1 (is a heterotrimer, composed of α1β1γ1 chain) overnight at 4 °C, and blocked with 2% heat-denatured BSA in PBS for 1 h. 24-h following infection with syntaxin-cyto, cells were harvested by trypsinization and collected by centrifugation in the presence of soybean trypsin inhibitor (20 μg/ml). Cells were allowed to adhere to dishes for different time periods at 37 °C in adhesion buffer (HEPES-buffered Hanks' balanced salt solution containing 1% bovine serum albumin, 2 mmol/liter of MgCl2, 2 mmol/liter of CaCl2, and 0.2 mmol/liter of MnCl2). In the integrin-blocking experiments, cells were suspended with antibodies against either β1 (P4C10; 50 μg/ml) or β3 (B3A; 50 μg/ml) integrin subunits and, intergrin heterodimers, either α5β1 (JBS5; 50 μg/ml) or αvβ3 (LM609; 50 μg/ml), and then allowed to adhere for different times at 37 °C. Nonadherent cells were removed by washing each well four times with adhesion buffer. Adherent cells were then fixed for 15 min, using 3.7% paraformaldehyde in PBS, and stained with a 2% crystal violet solution. After extensive washing in water to remove excess crystal violet, plates were dried overnight. Crystal violet was extracted by incubating the plates in 10% acetic acid for 15 min, after which absorbance at 562 nm was measured as an indicator of the number of cells bound. Each experiment was performed in triplicate (triplicate samples per condition). The data are presented as the percentage of adhesion exhibited by the positive control (adhesion medium alone) ± S.D.

Immunofluorescence Assay and Image Analysis

Microscopy and image analysis were performed using procedures described previously (17). Briefly, cells were grown on acid-washed glass coverslips. They were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in Dulbecco's modified phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 25 min at room temperature (RT), quenched with 100 mm glycine in PBS for 15 min at RT and washed with PBS. The cells were then permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 2 min at RT, blocked with PBS containing 5% glycine and 5% normal goat or donkey serum for 60 min, and incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. Slides were incubated for 1 h in a 1:100 dilution of either Alexa Fluor 488- or Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated secondary Ab, and mounted using Vectashield mounting medium containing DAPI.

Fluorescent images were acquired using a Leica spinning-disk confocal microscope equipped with a Hamamatsu EM-CCD digital camera (Hamamatsu Photonics) and “Metamorph” image acquisition and processing software (Molecular Devices Corp., Downingtown, PA). All images were acquired using a ×63, 1.3 NA objective. In any given experiment, all photomicrographs were exposed and processed identically for a given fluorophore. Images were corrected for background fluorescence using unlabeled specimens. For double labeling experiments, control samples were labeled identically with the individual fluorophores and exposed identically to the dual-labeled samples at each wavelength to verify that there was no crossover between emission channels at the exposure settings.

Immunoblotting and Immunoprecipitation

For immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation studies, cells were washed twice in ice-cold PBS and lysed in RIPA buffer supplemented with inhibitors of proteases and phosphatases as described previously (17). Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and then immunoblotted. Ab binding was visualized using the ECL reagent. For immunoprecipitation studies, cells were lysed in RIPA buffer containing a protease and phosphatase inhibitor mixture. Lysates were precleared with uncoupled protein A or G beads, and incubated for 3 h at 4 °C with Ab-coupled beads. Immune complexes were washed with lysis buffer and then subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

Integrin Recycling and Degradation Assay

To measure recycling of the surface pool of α5β1 integrin, we covalently labeled cell surface proteins using a membrane-impermeant biotinylation reagent (NHS-SS-biotin; Pierce) as described previously (17, 24). Samples were then incubated at 16 °C for an additional 30 min, to allow internalized α5β1 integrin to accumulate in EEs. Biotin remaining at the cell surface was removed by reduction with sodium 2-mercaptoethanesulfonate (MesNa). MesNa was quenched by the addition of 20 mm iodoacetamide for 10 min. The cells were washed twice in ice-cold PBS. Intracellular, biotin-labeled α5β1 integrin complexes were further chased at 37 °C, to allow integrins to recycle to the PM. In some experiments, the extent of α5β1 recycling was assessed after each time point of the 37 °C chase; in this case, cells were immediately returned to ice at the time point, and biotin was removed from the recycling pool by reduction with MesNa. In other experiments, the biotin-removal step was not undertaken, and the levels of biotinylated α5β1 integrin were determined using a capture ELISA assay.

Capture ELISA

Maxisorb 96-well plates (Invitrogen) were coated overnight with 5 μg/ml of the appropriate anti-α5 integrin Ab in 0.05 m Na2CO3 (pH 9.6) at 4 °C, and blocked in PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T) with 5% BSA for 1 h at RT. α5 integrin was captured by overnight incubation of 50 μl of cell lysate at 4 °C. Unbound material was removed by extensive washing with PBS-T, after which streptavidin-conjugated horseradish peroxidase (Amersham Biosciences) in PBS-T containing 1% BSA was placed into each well; samples were then incubated for 1 h at 4 °C. Following subsequent washing, biotinylated integrins were detected using a chromogenic reaction with ortho-phenylenediamine.

Endocytic Trafficking of β1 Integrin

Endocytic trafficking of β1 integrin from the cell surface was followed using anti-β1 integrin Ab (clone P5D2), as described previously with some modifications (25). HUVECs were maintained at 10 °C (a temperature at which endocytosis does not occur) (26) with 10 μg/ml of Ab in HMEM buffer (pH 7.4) (HEPES acid, 13.8 mm; NaCl, 137 mm; KCl, 5.4 mm; glucose, 5.5 mm; glutamine, 2.0 mm; KH2PO4, 0.4 mm; Na2HPO4, 0.18 mm; CaCl2, 1.25 mm; MgSO4, 0.08 mm) for 30 min. Samples were then incubated at 16 °C for 30 min, in HMEM buffer to allow the internalized Ab·β1 integrin complex to accumulate in EEs (17). Subsequently, samples were moved to a cold station maintained at 10 °C, and the remaining surface-bound Ab was removed by an acid wash (three washes with ice-cold 50 mm glycine in HMEM buffer, pH 2.5, and two washes with HMEM buffers, pH 7.5). The cells were then subjected to a chase of varying length at 37 °C, in HMEM buffer. At each of several time points, the cells were moved to a 10 °C cold station and washed with acid to remove any Ab that may have recycled to the surface during the chase. The intracellular distribution of the Ab·β1 integrin complex was assessed by fixing and permeabilizing cells, and labeling them with appropriate primary and secondary antibodies and then processing them for fluorescence microscopy.

Cell Migration Assay

Harvested cells (2 × 104) were replated in triplicates onto the upper chamber of a Transwell filter with 8-μm pores (6.5 mm, polycarbonate, Costar) coated on the lower side with 20 μg/ml of fibronectin (coating was done overnight at 4 °C in tissue culture hood), and the chamber was placed in serum-free DMEM. After 4–6 h, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Non-migrated cells on the upper side of the filter were removed with a cotton swab, and cells on the underside of the filter were stained with 2% crystal violet in 10% ethanol. After extensive washing in water to remove excess crystal violet, filters were dried overnight. The number of migrated cells was determined by eluting the crystal violet dye from the stained cells on the underside of the filter in 250 μl of 10% acetic acid (for 15 min) followed by measuring OD at 562 nm. In parallel, cells were also separately plated in triplicates to transwell filters not coated with fibronectin for estimating the total number of attached cells. Relative cell migration was determined by the number of the migrated cells normalized to the total number of the cells adhering to transwell filters.

Cell Spreading Assay

Cells were trypsinized and replated onto coverslips precoated with 20 μg/ml of either fibronectin or collagen (type I) or, laminin-1 or vitronectin at a concentration of 20,000 cells/well. The cells were allowed to spread for different times, after which they were fixed and labeled with 0.2 units/ml of Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated phalloidin and 1 mg/ml of Hoechst (Sigma) for 1 h. Cell surface boundaries were outlined for ≥100 cells (chosen randomly) for each time point, and Metamorph software was used to measure the surface area of each cell.

Rac Activation Assay

The levels of Rac1-GTP were measured by affinity precipitation using the GST-Cdc42/Rac interactive binding domain of PAK1, as described previously (27). In brief, cells were lysed in buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, 10 mm MgCl2, 1% Nonidet P-40, 5% glycerol, 1 mm EDTA (pH 8), 1 mm PMSF, and protease inhibitor mixture. Lysates were incubated with 30 μg of GST-Pak1-protein binding domain protein immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose (Amersham Biosciences, Inc.) beads, for 1 h at 4 °C. Specifically bound GTP-Rac1 was detected by immunoblotting with anti-Rac1 antibody.

Statistical Analysis

All values are expressed as mean ± S.D. Statistical significance was determined using a two-sided Student's t test, run on GraphPad Prism version 4.0 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA); unless stated otherwise, a value of p < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Functional Syntaxin 6 Is Essential for Adhesion between Endothelial Cells and Fibronectin

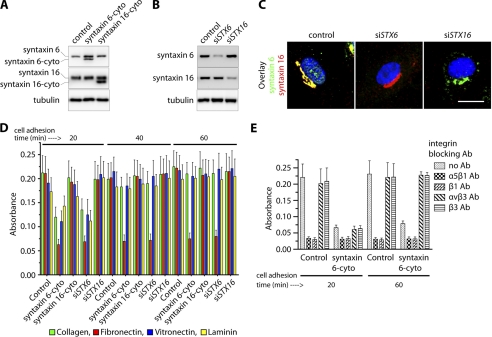

In a recent study we demonstrated that syntaxin 6 plays a role in regulating VEGF-induced EC migration and angiogenesis (17). Cell adhesion to the extracellular matrix is a prominent haptotactic mechanism by which cells migrate (28). In this study, we investigated whether syntaxin 6-regulated trafficking events contribute to adhesion between ECs and the extracellular matrix by two methods that reduce syntaxin 6 or syntaxin 16 function in HUVECs: (i) expression of the inhibitory cytosolic domains of syntaxin 6 and syntaxin 16 (designated syntaxin 6-cyto and syntaxin 16-cyto) and (ii) application of siRNAs targeting endogenous syntaxin 6 (STX6) and STX16, as syntaxins are tail-anchored proteins with a majority of the polypeptide exposed to the cytosol. The cytosolic part of syntaxin proteins interacts with its counterpartner to form a SNARE complex. The SNARE complex subsequently facilitates the docking and fusion of the two membrane compartments by functioning as a linker. However, the mutant syntaxin, which lacks the carboxyl-terminal hydrophobic region (syntaxin-cyto) essential for localization to intracellular membranes, competes with endogenous syntaxin in binding to its cognate SNARE partner. Thus, mutant syntaxin acts as a dominant-negative syntaxin (29). To inhibit the syntaxin-mediated intracellular vesicular fusion process this approach has been used by several groups including our previously published studies (17, 19, 29–31). Cells were infected with syntaxin 6-cyto or syntaxin 16-cyto, this resulted in expression of the respective protein at detectable levels in ≥95% of the cells by 12 h post-infection; the cells were used in experiments at 12–24 h post-infection (Fig. 1A). In the case of siRNA application, the extent of syntaxin 6 and syntaxin 16 knockdown in cell lysates was ≥80% (Fig. 1B), and the fraction of cells in which protein levels were reduced at least 10-fold was ≥95%, as judged by immunofluorescence analysis (Fig. 1C). Depletion of syntaxin 6 would inhibit cargo delivery from donor to target membrane due to lack of specific SNARE complex formation between donor and target membranes. These loss-of-function approaches, have shown similar effects in terms of syntaxin 6-mediated cargo transport between endosomes and Golgi complex (19, 29, 32).

FIGURE 1.

Inhibition of syntaxin 6 function blocks adhesion of endothelial cells to fibronectin. A and B, uninfected (control), syntaxin 6-cyto-, syntaxin 16-cyto-, siSTX6- or siSTX16-expressing HUVECs were cultured on fibronectin-coated surfaces in complete medium. Western blotting was performed to assess relative levels of endogenous syntaxin 6, syntaxin 16, syntaxin 6-cyto, syntaxin 16-cyto, or tubulin in cell lysates. A representative blot is shown (n = 5 independent experiments). C, HUVECs were transfected with siRNAs against STX6 or STX16. After 72 h of transfection, cells were fixed and co-immunostained using anti-syntaxin 6 and -syntaxin 16 Abs. Fluorescence images of representative cells from randomly chosen fields are shown, and fluorescence (excluding nuclei) was quantified and used to calculate the percentage of cells showing ≥90% reduction in syntaxin 6 or syntaxin 16 relative to untreated (control) cells. D and E, uninfected HUVECs (Control), and HUVECs stably expressing syntaxin 6-cyto, syntaxin 16-cyto, siSTX6, or siSTX16 were trypsinized and seeded in adhesion buffer onto plates coated with extracellular matrix proteins. After the cells were allowed to adhere for 20, 40, and 60 min, nonadherent cells were removed and cells were subjected to fixation and staining with crystal violet. Dye was extracted and absorbance was assessed as an indicator of the number of bound cells. The number of cells bound in the controls was set as basal adhesion (100%). E, control and syntaxin 6-cyto-expressing HUVECs were either left untreated (no Ab) or were pretreated with the indicated integrin blocking Abs for 10 min prior to seeding onto fibronectin-coated plates. Values represent relative change in adhesion normalized to an arbitrary value of 100% for controls. Values in D and E represent mean ± S.D. from four independent experiments; p ≤ 0.003 in D, p ≤ 0.005 in E.

Using these loss-of-function approaches, we found that inhibition of syntaxin 6 function (by either approach) affects adhesion of cells to fibronectin, collagen (type I), laminin-1, and vitronectin to varying extent during the initial 20-min period of adhesion. However, at later time periods (40 and 60 min) only adhesion to fibronectin was affected in cells where syntaxin 6 function was inhibited (Fig. 1D). Among the major integrin subunits present on the vascular EC surface, α5, β1, αv, and β3 are those that mainly bind to fibronectin and vitronectin (33). The inclusion of integrin-blocking Abs against the α5β1 heterodimer and β1 integrin during cell seeding onto the fibronectin matrix inhibited cell adhesion (Fig. 1E). The extent to which α5β1- and β1-targeted integrin Abs blocked cell adhesion (at 20 and 60 min post-seeding) was similar to that observed when syntaxin 6 function was inhibited. Abs against αvβ3 and β3 integrins did not interfere with the adhesion of cells to fibronectin. These results suggest that syntaxin 6 function and the α5β1 integrin dimer are required for EC adhesion to fibronectin.

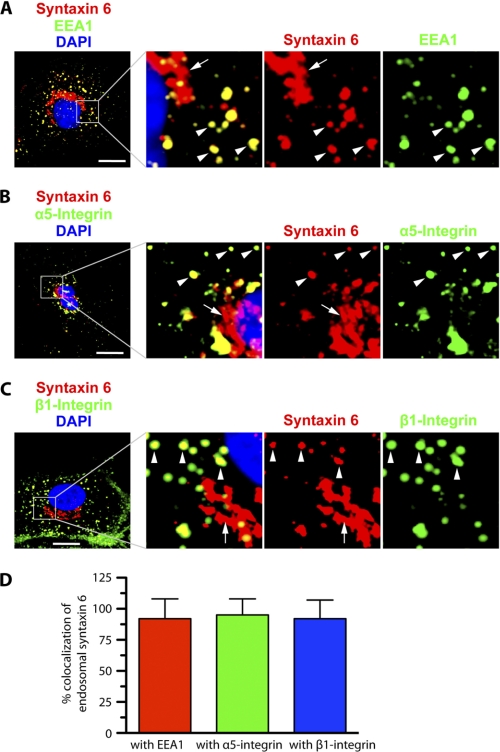

α5β1 Integrin Complexes Colocalize with Syntaxin 6-containing Endosomes

Having implicated syntaxin 6 in the control of cell adhesion mediated by α5β1 integrin complexes, we sought to establish whether syntaxin 6 exerts this control by regulating transport of α5β1 to the PM. In most cell types, syntaxin 6 is most strongly expressed in the Golgi, and it has been implicated in intra-Golgi or post-Golgi membrane trafficking events (17, 19, 29, 32, 34). However, syntaxin 6 is also present in endosomes, where it colocalizes with the EE marker EEA1 (20). Our immunofluorescence-based analysis of HUVECs is consistent with the reports from other studies. In addition to being prominently expressed in the perinuclear Golgi, syntaxin 6 is also found on the endosomes of HUVECs, and ≥90% of the endosome-associated syntaxin 6 colocalizes with EEA1 (Fig. 2A).

FIGURE 2.

Syntaxin 6, α5 integrin, and β1 integrin co-localize at EEA1-positive early endosomes in endothelial cells. HUVECs cultured in complete medium on fibronectin-coated surfaces were fixed, permeabilized, incubated with the indicated primary Abs, incubated with appropriate secondary Abs, and imaged by confocal fluorescence microscopy. A-C, representative confocal z-stacks, with enlarged insets highlighting colocalization between syntaxin 6 and EEA1, integrin α5, and integrin β1. In each case, arrowheads indicate colocalization between endosome-associated syntaxin 6 and each protein; arrows indicate lack of colocalization between Golgi-localized (perinuclear) syntaxin 6 and each protein. Confocal z-planes corresponding to the PM (dorsal- and ventral-most) are not included in B and C to avoid interference of signal from cell surface with signal from intracellular structures. D, signal overlap in images such as those were used to quantitate the extent to which syntaxin 6 was colocalized with each protein within EEs. Values represent mean ± S.D. (n = 50 cells for each condition, from 5 separate experiments; p ≤ 0.05). Scale bar represents 5 μm.

We explored the possibility that syntaxin 6 plays a role in trafficking of the α5 and β1 integrins by performing confocal microscopy-based immunolocalization analysis of α5 and β1 integrin expression with respect to syntaxin 6 expression. The images generated revealed that ≥80% of endosome-localized syntaxin 6 colocalized with the α5 and β1 integrins (Fig. 2, B–D, arrowheads). Our data suggest that α5β1 integrin complexes traffic through syntaxin 6-containing endosomes, and are consistent with the notion that syntaxin 6 regulates this trafficking.

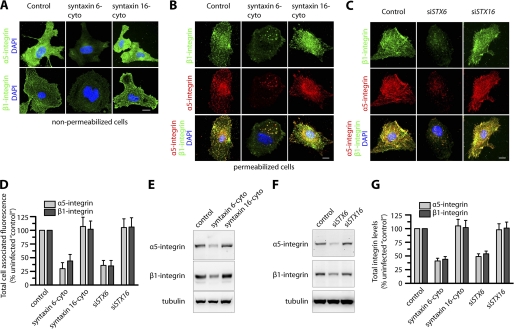

Functional Syntaxin 6 Is Essential for Normal Distribution of α5β1 Integrin in Endothelial Cells

We next investigated if syntaxin 6 or syntaxin 16 plays a role in maintaining the cellular distribution of α5β1 integrin complexes, using both of the approaches described above, and also evaluated the cellular distribution and levels of the α5 and β1 integrins by epifluorescence microscopy and Western blotting (Fig. 3). We selected syntaxin 16 as a control because syntaxin 6 interacts with each other and has also been reported to form SNARE complexes with each other or with other SNAREs and participate in membrane trafficking events among EEs and the Golgi complex (17, 20, 29, 32, 34, 35). The expression of syntaxin 6-cyto significantly reduced cell surface levels of both the α5 and β1 integrins, as revealed by epifluorescence microscopy of fixed nonpermeabilized cells. An examination of permeabilized cells treated with syntaxin 6-cyto revealed that the total cellular levels of the α5 and β1 integrins were also reduced and the distributions of these integrins were altered, with both α5 and β1 accumulating in enlarged intracellular vesicles (Fig. 3B). Quantitation of the epifluorescence signal in cells expressing syntaxin 6-cyto showed 70 and 55% reductions in the levels of α5 and β1 integrin, respectively (Fig. 3D). Western blotting followed by densitometric quantitation of bands revealed that α5 and β1 integrin levels in cell lysates were reduced by 50–60% in the presence of syntaxin 6-cyto, but that they were not significantly affected in cells treated with syntaxin 16-cyto (Fig. 3, E and G). These studies were complemented by analysis of HUVECs expressing siRNAs targeting STX6 and STX16: in syntaxin 6 knockdown cells, the reduction in the levels of α5 and β1 integrins, as well as the changes in their distribution, were similar to those observed in syntaxin 6-cyto-treated cells (Fig. 3, C, D, F, and G); in syntaxin 16 knockdown cells, neither the levels nor cellular distributions of these integrins were affected.

FIGURE 3.

Inhibition of syntaxin 6 function decreases α5β1 integrin levels, both cell surface-localized and total in endothelial cells. Uninfected (Control), syntaxin 6-cyto-, syntaxin 16-cyto-, siSTX6-, or siSTX16-expressing HUVECs were cultured on fibronectin-coated surfaces in complete medium. A, cells were pre-treated with Abs against α5 and β1 integrin at 4 °C prior to fixation and labeling with Alexa 488-labeled secondary Ab. Samples were then imaged by epifluorescence microscopy; representative images show cell surface levels of α5 and β1 integrins. B and C, cells were fixed and permeabilized, labeled with Abs against α5 or β1 integrin, and then labeled with the appropriate fluorescently tagged secondary Ab. Representative images obtained by epifluorescence microscopy show localization of total cell-associated α5 and β1 integrins. D, quantification of total cellular α5 and β1 integrin in syntaxin 6-cyto-, syntaxin 16-cyto-, siSTX6-, or siSTX16-expressing cells. Epifluorescence images were acquired and total cell-associated fluorescence was quantified by image analysis. Values represent relative change in the levels of α5 or β1 integrin normalized to an arbitrary value of 100% for untreated controls. Results are expressed as mean ± S.D. (n = 70 cells for each condition, from 3 separate experiments; p ≤ 0.001). E and F, Western blotting to assess α5 and β1 integrin levels in cell lysates. A representative blot is shown. G, α5 and β1 integrin band densities from E and F were quantified; values represent relative levels of α5 and β1 after normalization to the arbitrary value of 100 for uninfected cells (Control). (mean ± S.D.; n = 3; p ≤ 0.005). Scale bars represent 5 μm.

In addition to α5β1, ECs also express α1β1 and α2β1, which binds to collagen and laminin; αvβ3 and αvβ5 bind to vitronectin; α4β1 binds to fibronectin (36). We further investigated if levels of α1, α2, α4, αv, β1, β3, and β5 integrins were affected by loss of syntaxin 6 function. In syntaxin 6 knockdown cells (but not in syntaxin 16 knockdown cells) the levels of α2 and α4 integrins were increased by 10–12% relative to controls. The levels of other integrins in syntaxin 6 or syntaxin 16 knockdown cells were similar to controls (supplemental Fig. S1). From these results, we conclude that syntaxin 6 (but not syntaxin 16) function is required for maintaining normal cellular levels of the α5 and β1 integrins.

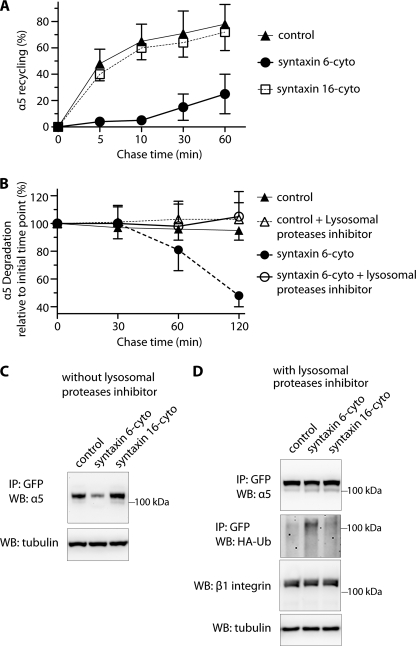

Functional Syntaxin 6 Is Required for α5β1 Integrin Recycling

Having established that α5 and β1 integrins colocalize extensively with endosome-associated syntaxin 6 and that the cell surface levels of these proteins are reduced in the context of disrupted syntaxin 6 function, we next investigated whether syntaxin 6 contributes to endocytic sorting of α5β1 integrin complexes from the EEs. To this end, we assessed the influence of syntaxin 6 and syntaxin 16 inhibition on trafficking of the PM pool of α5β1 integrin along the endocytic recycling pathway. Cells were exposed to biotin and then subjected to a 16 °C temperature block, during which surface-biotinylated integrin were internalized and accumulate in EEs. Residual surface biotin was removed by treatment with MesNa, and then a sample was taken to establish how much of the initial PM-localized pool of α5β1-integrin had been internalized. Cells were then subjected to a 37 °C chase to allow subsequent trafficking from endosomes. After each chase time point, the samples were again treated with MesNa to remove any biotin from previously internalized α5β1 that had recycled back to the cell surface, and the level of biotinylated integrin remaining within the cell was quantified by capture ELISA. The percentage of integrin recycled back to the PM was determined by comparing the levels of biotinylated α5 integrin remaining after the chase to the amount in the pool internalized originally.

In control (uninfected) cells, almost 60% of the internalized α5 integrin was recycled back to the PM after 10 min of chase, and this number increased to nearly 80% by 60 min of chase (Fig. 4A). The same was true in cells with inhibited syntaxin 16 function. In contrast, in the context of syntaxin 6 inhibition, recycling of α5 integrin during the initial 10 min of the chase period was nearly abolished. Although less internalized, biotinylated α5 integrin was present at later time points (60 min of chase), this could have been due either to recycling (and debiotinylation by MesNa treatment) or degradation (Fig. 4A). Because loss of syntaxin 6 function leads to a decrease in the overall levels of α5 integrin as well in the levels associated with the PM (Fig. 3), we predicted that degradation was responsible for the observed reduction after 60 min of chase (Fig. 4A). We tested this possibility by pretreating control (uninfected) and syntaxin 6-cyto expressing cells with leupeptin (lysosomal proteases inhibitor) and then chasing biotinylated, internalized α5 integrin for different time periods, without removing biotin from recycled complexes on the cell surface (no MesNa treatment). Compared with control, internalized, biotinylated α5-integrin was nevertheless, lost at later time points in syntaxin 6-cyto expressing cells, and this outcome was rescued by treatment with an inhibitor of lysosomal proteases (leupeptin; Fig. 4B). Our results suggest that syntaxin 6 plays a role in sorting α5β1 integrin complexes from endosomes toward the recycling pathway, and that in the absence of syntaxin 6, the PM-derived endosomal pool of α5β1 integrin is targeted for degradation in lysosomes.

FIGURE 4.

Inhibition of syntaxin 6 function reduces endocytic recycling of α5 integrin and increases its ubiquitination and degradation in lysosomes. A, uninfected (control) and syntaxin 6-cyto- or syntaxin 16-cyto-infected HUVECs were surface biotinylated. Samples were then incubated at 16 °C for 30 min, to allow biotinylated α5β1 integrin to accumulate in EEs. Biotin remaining at the surface was removed by treatment with MesNa and quenching of MesNa with iodoacetamide (0-min time point); samples were further incubated at 37 °C for the indicated periods and, at each time point shown, subjected to a second MesNa treatment and then assessed for recycling of internalized integrin. After each time point, the cells were lysed and the amount of biotinylated integrin was determined by capture ELISA, using an Ab against α5 integrin. The fraction of internalized integrin recycled back to the PM is expressed as a percentage of surface-labeled protein originally internalized (from the 0-min chase time point). B, uninfected and syntaxin 6-cyto-infected cells were surface biotinylated and assessed for α5 integrin expression as in A, but were not subjected to a second treatment with MesNa. The fraction of internalized integrin remaining (i.e. PM-associated due to recycling + intracellular) after various chase periods is expressed as the percentage of surface-labeled internalized (0-min chase time point). Values in A and B are mean ± S.D. from four independent experiments; p ≤ 0.005 in A, p ≤ 0.05 in B. C and D, uninfected (Control) and syntaxin 6-cyto- or syntaxin 16-cyto-infected HUVECs after 12 h of infection were electroporated with (i) α5-integrin-GFP plasmid (in C) or (ii) a mixture of α5-GFP-integrin and HA-ubiquitin plasmids. After 12 h, the cells were cultured in the presence of 300 μm leupeptin for 12 h (in D). After 24 h of electroporation, cell lysates were prepared and incubated with anti-GFP Ab coupled to beads. Relative levels of α5-GFP-integrin in the cell lysates were determined by immunoprecipitating (IP) with anti-GFP Ab, and immunoblotting (WB) with anti-α5 integrin Ab. Ubiquitination was detected by immunoblotting against anti-HA Ab. Relative enrichment of β1 integrin and tubulin in cell lysates (10% input) was detected using Abs against β1 integrin and tubulin.

For many cell surface receptors, including integrins, ligand binding triggers ubiquitination, which tags them for sorting into the lumen of the multivesicular endosomes, and for subsequent degradation (8, 37, 38). Thus, we next investigated if the reduction of syntaxin 6 function leads to ubiquitination of α5 integrin and its subsequent targeting to lysosomes for degradation. To this end, we expressed α5-GFP-integrin in HUVECs. Like endogenous α5 integrin, α5-GFP-integrin was degraded in cells with reduced syntaxin 6 function (Fig. 4C). To assess the effects of syntaxin 6 inhibition on the ubiquitination status of α5 integrin, we coexpressed GFP-α5 integrin along with HA-tagged ubiquitin in HUVECs pretreated with leupeptin. In control cells, ubiquitination of GFP-α5 integrin was not detected. In contrast, cells in which syntaxin 6 was inhibited the levels of ubiquitinated α5-GFP integrin were markedly increased (Fig. 4D). The preferential increase in ubiquitination of the α5-GFP-integrin was specific to cells expressing syntaxin 6-cyto. Our results suggest that syntaxin 6 prevents ubiquitination of the α5 integrin; the downstream consequences may be similar to the mechanism that leads to ubiquitination of α5β1 integrin in the presence of soluble fibronectin (8).

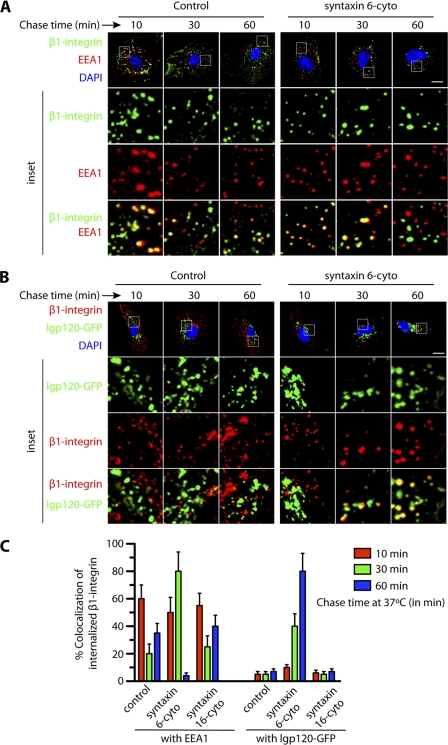

We next examined the itinerary of α5β1 integrin trafficking along the endocytic pathway using an antibody targeting the β1 integrin (25). In control cells, the EE marker EEA1 colocalized with about 60% of the internalized β1 integrin after 10 min of chase, 20% after 30 min of chase, and 40% after 60 min chase. Presumably the drop at 30 min was due to progressive transport and recycling, and the increase at 60 min to re-internalization of recycled receptor (Fig. 5, A and C). Notably, the bulk of integrin heterodimers at the cell surface usually follow the recycling pathway and were not transported toward the lysosomes (39, 40). As expected, we did not observe much colocalization between internalized β1 integrin and GFP-lgp120 (GFP-tagged form of the 120-kDa lysosomal membrane glycoprotein, a marker for lysosomes) (22). In cells expressing syntaxin 6-cyto, colocalization between β1-integrin and GFP-lgp120 was similar to that in controls during the initial 10 min of chase, i.e. <10% (Fig. 5, B and C). However, after a 60-min chase, colocalization in cells expressing syntaxin 6-cyto rose to 80%, whereas colocalization in the control remained at <10%. Moreover, at this time point there was a significant decrease in the colocalization of internalized β1 intergin with EEA1 (Fig. 5, A and C). In cells expressing syntaxin 16-cyto the colocalization of internalized β1 integrin with EEA1 and lgp120 after chase was similar to controls (Fig. 5C). These results suggests that, in the absence of syntaxin 6 function, the endocytic pool of α5β1 integrin complexes are diverted from the recycling pathway toward the LEs and lysosomes for degradation.

FIGURE 5.

Inhibition of syntaxin 6 function leads to change in trafficking of α5β1 integrins from the early endosomes toward the degradation versus recycling pathway. A and B, uninfected (control), syntaxin 6-cyto or syntaxin 16-cyto-infected HUVECs were labeled with anti-β1 integrin Ab at 10 °C, followed by incubation at 16 °C for 30 min to allow internalized Ab-β1 integrin complexes to accumulate in EEs. The remaining surface-bound Ab was removed by washing with low pH buffer. These samples were then subjected to chase at 37 °C for the indicated time periods before being fixed and permeabilized. Intracellular Ab-β1 integrin complexes and EEA1 were detected using the Alexa 488- and Alexa 594-labeled secondary Abs, respectively. Samples were then imaged by confocal fluorescence microscopy, for intracellular localization of the Ab-β1 integrin complexes, EEA1 (early endosomes), and GFP-lgp120 (lysosomes). C, colocalization of Ab-β1 integrin complexes with EEA1 and GFP-lgp120 was quantitated from images such as those shown in A and B. Values represent mean ± S.D. (n = 50 cells for each condition from 5 separate experiments; p ≤ 0.05). Scale bar represents 5 μm.

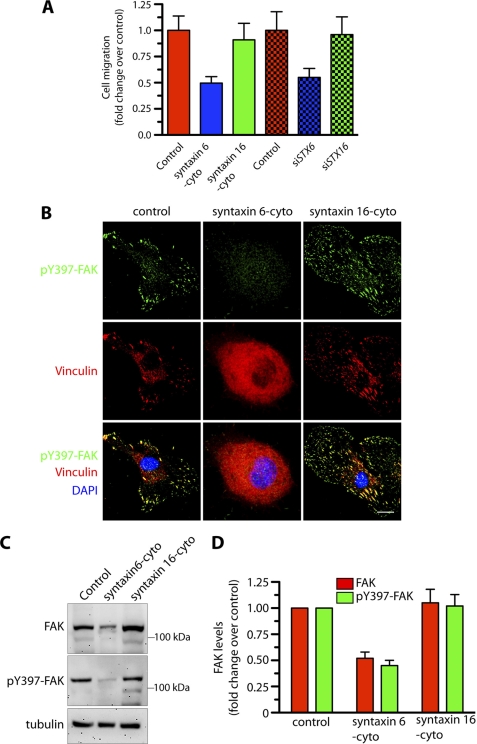

Functional Syntaxin 6 Is Required for Endothelial Cell Migration toward Fibronectin, and for Recruitment of Phospho-FAK and Vinculin to Focal Adhesions

Integrins modulate angiogenesis by facilitating EC haptotaxis, a process defined as directed cell migration toward immobilized extracellular matrix components (41). Thus, we next investigated the possibility that the reduction in PM α5β1 integrin levels resulting from loss of syntaxin 6 function (Fig. 3A) negatively influences the directional migration of EC toward fibronectin. This was indeed the case: the migration of cells expressing syntaxin 6-cyto or siSTX6 toward fibronectin was 1.8–2-fold lower than that of controls, whereas that of cells expressing syntaxin 16-cyto or siSTX16 was not significantly changed (Fig. 6A). At focal adhesions, FAK serves as an important integration point for integrin signaling, and FAK autophosphorylation of tyrosine 397 is required for integrin-stimulated cell migration. In control cells, pFAK and vinculin colocalize at the focal adhesion sites. However, in cells expressing syntaxin 6-cyto, neither pFAK nor vinculin was present at focal adhesion sites (Fig. 6B). Syntaxin 6 inhibition also reduced the total cellular levels of FAK and pFAK by ∼50% (Fig. 6, C and D). The manipulation of syntaxin 16 had no significant effect on these parameters. Our results suggest that functional syntaxin 6 is required to regulate the haptotaxis of ECs toward fibronectin, and that it functions by targeting active FAK to focal adhesions.

FIGURE 6.

Inhibition of syntaxin 6 function in endothelial cells blocks migration and recruitment of active FAK to focal adhesions. Uninfected (control), syntaxin 6-cyto-, syntaxin 16-cyto-, siSTX6-, or siSTX16-expressing HUVECs were grown on fibronectin-coated surfaces were serum starved for 2–3 h before being used for experiments. A, directional migration of HUVECs toward fibronectin in a Boyden chamber assay, with the medium in the lower well lacking serum. The number of migrating cells was normalized to that in uninfected controls. B, cells were stimulated with serum-containing medium for 10 min and then co-stained with Abs against phospho-Tyr397-FAK and vinculin to visualize focal adhesion sites. C, cells treated as in B were used to prepare lysates. Proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-FAK and anti-phospho-Tyr397-FAK Abs. Relative levels of tubulin in cell lysate confirms that protein loading in each well was equal. D, quantification of FAK and pFAK band densities; values represent ratios of pFAK to total FAK after normalization to the arbitrary value of 100 for uninfected HUVECs (control). Values represent mean ± S.D. (n = 3; p ≤ 0.005). Scale bars represent 5 μm.

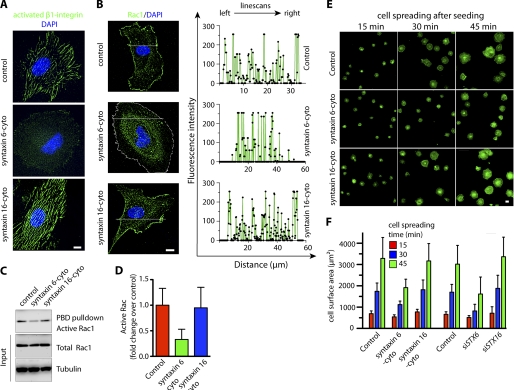

Functional Syntaxin 6 Is Essential for Maintaining β1 Integrin Activation, Rac1 Localization, Rac1 Activation, and Endothelial Cell Spreading on Fibronectin

Activated integrins localize to the leading front of ECs migrating in a Rac1-dependent manner (42). We thus investigated whether functional syntaxin 6 is required to maintain the levels of activated β1 integrin at the cell surface. To assess integrin activation, we labeled fixed nonpermeabilized HUVECs with an Ab that recognizes the active conformation of β1 integrin (clone HUTS-21) (43, 44). In control uninfected HUVECs, active integrin at the cell surface had a striated appearance, as shown previously (45). However, syntaxin 6 inhibition (and not syntaxin 16 inhibition) significantly reduced the levels of activated β1 integrin at the PM (Fig. 7A). β1 Integrin is required for cell adhesion-dependent membrane targeting and activation of Rac1 (Rac1 GTP-loading) (46–48). If syntaxin 6 is important for α5β1-dependent adhesion of cells to fibronectin, then Rac1-GTP (active Rac1) may be reduced in syntaxin 6-inhibited cells. We first assessed the cellular localization of endogenous Rac1. In control (uninfected) cells, the levels of endogenous Rac1 near the cell periphery were high, as revealed by epifluorescence images and analyzing fluorescence pixel intensities from line scans (Fig. 7B). However, when syntaxin 6 function was inhibited, Rac1 was redistributed from the cell periphery to perinuclear locations; quantitation of this effect by analyzing pixel intensities from line scans confirmed that the signal intensity at the cell periphery was significantly reduced (Fig. 7B, line scans). The amount of Rac1-GTP (active Rac1) was assessed by a GST-PAK pulldown assay. Compared with controls, Rac1-GTP in cells treated with syntaxin 6-cyto (but not in those treated with syntaxin 16-cyto) was 3-fold lower than that in control cells (Fig. 7, C and D). However, total levels of Rac1 were similar among control, syntaxin 6-cyto-treated and syntaxin 16-cyto-treated cells. We further investigated if syntaxin 6 plays a role in cell spreading. Cells were allowed to spread on fibronectin following trypsinization. Actin was then labeled with phalloidin, and the cell surface area was calculated from epifluorescence images. Using two syntaxin loss-of-function approaches we show that inhibition of syntaxin 6 (but not that of syntaxin 16) slowed cell spreading at each time point post-seeding (Fig. 7, E and F, supplemental Fig. S4) on fibronectin. However, syntaxin 6 inhibition did not alter cell spreading on other matrices such as collagen, laminin, or vitronectin (supplemental Fig. S2). We further explored the possibility if by rescuing α5β1 integrin levels in syntaxin 6 inhibited cells by lysosomal protease inhibitor, we can also rescue integrin-mediated signaling and cell spreading. Our results show that in syntaxin 6-cyto expressing cells, the inhibition of lysosomal proteases activity restores cellular integrin levels (Fig. 4D), however, it does not restore FAK phosphorylation, Rac1 activation, or cell spreading on fibronectin (supplemental Fig. S3). These experiments indicate that functional syntaxin 6 is required to maintain α5β1 integrin levels, α5β1 integrin-mediated downstream signaling, and facilitates EC spreading on fibronectin.

FIGURE 7.

Inhibition of syntaxin 6 function blocks integrin activation, alters Rac1 distribution, reduces active Rac1, and slows spreading of endothelial cells on fibronectin. Uninfected HUVECs (control), syntaxin 6-cyto- or syntaxin 16-cyto-infected, or siSTX6- or siSTX16-expressing HUVECs were cultured on fibronectin-coated surfaces in complete medium. HUVECs were grown on fibronectin-coated surfaces. A, samples were then labeled with the HUTS21 Ab, which recognizes β1 integrin in its active conformation. B, Rac1 localization was assessed by staining fixed, permeabilized cells with anti-Rac1 Ab. Images were acquired by epifluorescence microscopy, and line scans were generated using Metamorph image analysis software. For clarity of presentation, representative syntaxin 6-cyto-infected cell edge was marked by a white dashed line. C, lysates were prepared and subjected to a GST-PBD pulldown assay, followed by blotting with Rac1 Ab to detect active Rac1. The relative levels of total Rac1 and tubulin in cell lysates (10% input) were detected by immunoblotting with Abs. D, the intensity of the band of active Rac1 was assessed after a GST-PBD pulldown assay and quantitated and normalized to that of the control. Values represent mean ± S.D. (n = 3; p ≤ 0.003). E, cells were trypsinized and then allowed to spread on a fibronectin-coated glass surface at 37 °C for the indicated times. Following fixation, permeabilization, and staining with Alexa 488-labeled phalloidin, the cells were imaged by epifluorescence microscopy. Representative images are shown, representative images of siSTX6- and siSTX16-treated samples are included under supplemental Fig. 4. F, quantitation of the cell surface areas of individual cells, based on epifluorescence images of cells described in E. Values represent mean ± S.D. (cells = 300, from 3 separate experiments; p ≤ 0.003). Scale bars represent 5 μm.

DISCUSSION

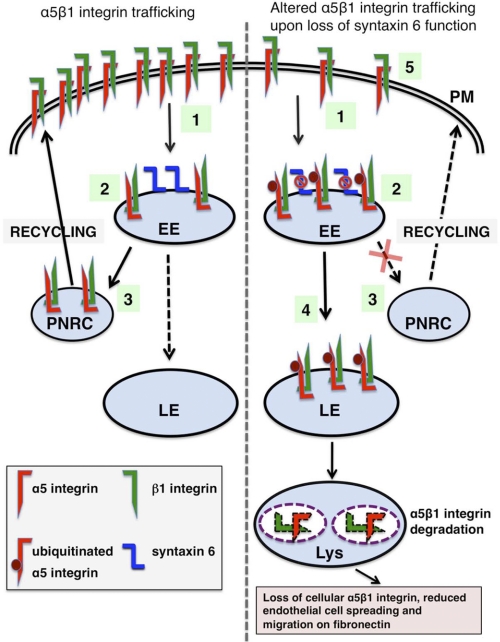

EC haptotaxis is driven by an interaction between cell surface-localized α5β1 integrin complexes and the extracellular matrix protein fibronectin (28). The expression of α5β1 on the PM is regulated by internalization, intracellular transport, and recycling of integrins (4). In particular, EC migration during angiogenesis, under both physiological and pathological conditions, depends on recycling of integrins to the leading edge of the EC (21, 49, 50). Our findings show that in ECs, syntaxin 6 colocalizes with α5β1 integrins at the EEs, and that loss of syntaxin 6 function results in reduced adhesion to the fibronectin matrix. Our results support a model (outlined in Fig. 8) according to which EE-localized syntaxin 6 facilitates recycling of α5β1 integrin complexes to the PM, and syntaxin 6 dysfunction leads to reduced levels of the integrin complex at the cell surface, a failure of integrin transport along the recycling pathway, increased integrin ubiquitination, and increased transport of integrin complexes toward lysosomes for degradation. We further reveal that loss of syntaxin 6 function impairs recruitment of pFAK to focal adhesions, alters Rac1 localization, and decreases Rac activation, and that syntaxin 6 plays a key role in regulating the movement of EC along fibronectin.

FIGURE 8.

Proposed itineraries of α5β1 integrin in endothelial cells with and without syntaxin 6 function. 1, α5 and β1 integrin complexes are co-internalized from the cell surface. 2, the complexes are transported to EEA1-positive EEs. 3, α5β1 complexes are transported through the perinuclear recycling compartment (PNRC) (recycling pathway) for delivery to the PM. Loss of syntaxin 6 function blocks the transport of α5β1 integrin through the recycling pathway. In the absence of syntaxin 6 function: 4, the pool of ubiquitinated α5 integrin within the EE increases, and α5β1 complexes are transported to LEs/lysosomes for degradation; and 5, levels of α5β1 integrin at the cell surface are reduced, leading to impaired cell adhesion, migration, and spreading on fibronectin.

Syntaxins are members of the t-SNARE family, proteins that regulate vesicle fusion (51). Syntaxin 6 is a ubiquitously expressed Golgi- and endosome-localized vesicle fusion protein (17–20). In ECs, syntaxin 6 is required to maintain VEGFR2 levels; its inhibition leads to mistargeting of the Golgi-localized pool of VEGFR2 for degradation, and inhibits VEGF-induced EC migration and angiogenesis (17). In breast cancer cells, syntaxin 6 is required for proper expression of α5 integrin, however, the mechanism by which syntaxin 6 regulates α5 integrin levels was not studied (52). In the current study, we show that syntaxin 6 plays a second important role in ECs, i.e. α5β1 integrin transport from the EEs for recycling to the PM, and that this is crucial for proper migration of ECs along the extracellular matrix. In the present study, we demonstrate that syntaxin 6 function in ECs is required to maintain both total cellular and PM levels of α5β1 integrin, a fact that accounts for the interference of syntaxin 6 with dysfunctional EC binding to and spreading on fibronectin. The α5β1 integrin after internalization from the PM arrive at EEs, from which they are sorted for transport to: (i) the PM, via perinuclear recycling compartments (indirectly), or (iii) LEs and lysosomes (for degradation) (5, 7, 8, 24, 53). Most integrins serve as recycling receptors, and are transported from the EEs via either a Rab4-dependent short loop (EE to PM) or Rab11-dependent long-loop (EE-perinuclear recycling compartment-PM) pathway (21). In this study we show that functional inhibition of syntaxin 6 prevents sorting of α5β1 integrin from the EEs toward the recycling pathway. How syntaxin 6 inhibition interferes with α5β1 recycling could be the focus of a future study. Syntaxin 6 is known to interact with EEA1, a vesicle tethering factor that regulates homotypic fusion between EEs (20, 34). We speculate that syntaxin 6 plays a role in the maintenance of lipid (phosphoinositides or cholesterol) or protein composition and/or domain organization of Rab GTPases on the endosome membrane, and thereby facilitates sorting from the EE. This would be consistent with our previous observation that an elevation in EE cholesterol levels altered Rab4-mediated endocytic recycling (54). Although syntaxin 16 interacts with syntaxin 6, but is a part of a SNARE complex that participates in endosomes to Golgi transport, and moreover, syntaxin 16 does not interact with EEA1, like syntaxin 6 does, this may be the reason why syntaxin 16 did not alter α5β1 integrin trafficking along endocytic recycling pathway (20, 29, 32).

When we looked at the time course of α5β1 integrin trafficking through the endocytic recycling pathway, we observed that syntaxin 6 dysfunction results in a reduction in α5β1 recycling, a consequent delay in transport of the α5β1 integrin from EEs and, eventually, alternate transport toward the LEs/lysosomes for degradation. In syntaxin 6-inhibited cells, we also observed an increase in the pool of ubiquitinated α5β1 when lysosomal protease activity was blocked. Endosomal sorting complex required for transport proteins recognize ubiquitinated α5β1 integrin and target them to multivesicular endosomes for degradation (8). Our results suggest that in ECs, syntaxin 6 protects the cellular α5β1 integrin pool from ubiquitination, and thus from selective targeting to multivesicular endosomes for degradation.

Interactions between endothelial cell surface-associated α5β1 and fibronectin play an important role in regulating integrin-mediated angiogenic signaling (3, 50, 55, 56). In ECs, α5β1 integrin promotes the formation of focal adhesions and efficient signaling through focal adhesion kinase (FAK) (57). FAK activation and its autophosphorylation at Tyr397 is crucial for integrin signaling that promotes EC migration (58). Our data support this model, because syntaxin 6 inhibition reduced the levels of both total and active, cell surface-associated α5β1 integrin, the levels of total and active FAK, the number of focal adhesion sites, and directional migration toward fibronectin. These results agrees with a previous study in breast cancer cells where reduction in syntaxin 6 levels decreased the expression of total FAK (52). Rac1, a member of Rho family of proteins, plays an important role in α5β1-dependent cell spreading, integrin activation, and integrin clustering (50). We show that functional inhibition of syntaxin 6 alters Rac1 localization and reduces Rac1 activation. Our data shows that rescuing α5β1 integrin from degradation in cells lacking functional syntaxin 6 by the lysosomal proteases inhibitor would accumulate integrin in lysosomes, a terminal endocytic compartment from where it may not be able to recycle to the PM to form a signaling competent focal adhesion complex and this may explain why FAK phosphorylation, Rac1 activation, and cell spreading was not be rescued. Based on these results, we speculate that syntaxin 6 facilitates trafficking of the α5β1 integrin complexes through EEs for recycling to the PM, the activation of α5β1 integrin complexes, and α5β1 integrin-dependent signaling via FAK that leads to Rac1 activation and cell spreading.

In summary, we have provided the first demonstration that syntaxin 6 is involved in maintaining cell surface levels of α5β1 integrin complexes. Knowing that these adhesion complexes play a key role in regulating haptotaxis of ECs toward fibronectin, it will be interesting to learn how in vivo manipulation of syntaxin 6 levels in the vasculature affect both physiological and pathological angiogenic events.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Meghan Naber for technical assistance and Dr. Christine Blaumueller for editorial contributions.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants HL089599 from the NHLBI (to A. C.) and CA127958 from the NCI (to A. G.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S5.

- EC

- endothelial cell

- PM

- plasma membrane

- EE

- early endosome

- EEA1

- early endosomal autoantigen 1

- LE

- late endosome

- HUVEC

- human umbilical vein endothelial cell

- Ab

- antibody

- FAK

- focal adhesion kinase

- MesNa

- sodium 2-mercaptoethanesulfonate.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hynes R. O. (2002) Cell 110, 673–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Banerjee E. R., Latchman Y. E., Jiang Y., Priestley G. V., Papayannopoulou T. (2008) Exp. Hematol. 36, 1004–1013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Francis S. E., Goh K. L., Hodivala-Dilke K., Bader B. L., Stark M., Davidson D., Hynes R. O. (2002) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 22, 927–933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Caswell P. T., Vadrevu S., Norman J. C. (2009) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 843–853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Roberts M. S., Woods A. J., Dale T. C., Van Der Sluijs P., Norman J. C. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 1505–1515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gonon E. M., Skalski M., Kean M., Coppolino M. G. (2005) FEBS Lett. 579, 6169–6178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tayeb M. A., Skalski M., Cha M. C., Kean M. J., Scaife M., Coppolino M. G. (2005) Exp. Cell Res. 305, 63–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lobert V. H., Brech A., Pedersen N. M., Wesche J., Oppelt A., Malerød L., Stenmark H. (2010) Dev. Cell 19, 148–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen Y. A., Scheller R. H. (2001) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 98–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hong W. (2005) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1744, 493–517 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McNew J. A., Parlati F., Fukuda R., Johnston R. J., Paz K., Paumet F., Söllner T. H., Rothman J. E. (2000) Nature 407, 153–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Scales S. J., Chen Y. A., Yoo B. Y., Patel S. M., Doung Y. C., Scheller R. H. (2000) Neuron 26, 457–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Luftman K., Hasan N., Day P., Hardee D., Hu C. (2009) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 380, 65–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Skalski M., Yi Q., Kean M. J., Myers D. W., Williams K. C., Burtnik A., Coppolino M. G. (2010) BMC Cell Biol. 11, 62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rapaport D., Lugassy Y., Sprecher E., Horowitz M. (2010) PLoS One 5, e9759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hasan N., Hu C. (2010) Exp. Cell Res. 316, 12–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Manickam V., Tiwari A., Jung J. J., Bhattacharya R., Goel A., Mukhopadhyay D., Choudhury A. (2011) Blood 117, 1425–1435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bock J. B., Klumperman J., Davanger S., Scheller R. H. (1997) Mol. Biol. Cell 8, 1261–1271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Choudhury A., Marks D. L., Proctor K. M., Gould G. W., Pagano R. E. (2006) Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 317–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Simonsen A., Gaullier J. M., D'Arrigo A., Stenmark H. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 28857–28860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Caswell P. T., Norman J. C. (2006) Traffic 7, 14–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Patterson G. H., Lippincott-Schwartz J. (2002) Science 297, 1873–1877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Laukaitis C. M., Webb D. J., Donais K., Horwitz A. F. (2001) J. Cell Biol. 153, 1427–1440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Roberts M., Barry S., Woods A., van der Sluijs P., Norman J. (2001) Curr. Biol. 11, 1392–1402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Teckchandani A., Toida N., Goodchild J., Henderson C., Watts J., Wollscheid B., Cooper J. A. (2009) J. Cell Biol. 186, 99–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sharma D. K., Choudhury A., Singh R. D., Wheatley C. L., Marks D. L., Pagano R. E. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 7564–7572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Scita G., Nordstrom J., Carbone R., Tenca P., Giardina G., Gutkind S., Bjarnegård M., Betsholtz C., Di Fiore P. P. (1999) Nature 401, 290–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Davis G. E., Senger D. R. (2005) Circ. Res. 97, 1093–1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mallard F., Tang B. L., Galli T., Tenza D., Saint-Pol A., Yue X., Antony C., Hong W., Goud B., Johannes L. (2002) J. Cell Biol. 156, 653–664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Perera H. K., Clarke M., Morris N. J., Hong W., Chamberlain L. H., Gould G. W. (2003) Mol. Biol. Cell 14, 2946–2958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Proctor K. M., Miller S. C., Bryant N. J., Gould G. W. (2006) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 347, 433–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ganley I. G., Espinosa E., Pfeffer S. R. (2008) J. Cell Biol. 180, 159–172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hynes R. O. (2007) J. Thromb. Haemost. 5, Suppl. 1, 32–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wendler F., Page L., Urbé S., Tooze S. A. (2001) Mol. Biol. Cell 12, 1699–1709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wang Y., Tai G., Lu L., Johannes L., Hong W., Tang B. L. (2005) Mol. Membr. Biol. 22, 313–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Avraamides C. J., Garmy-Susini B., Varner J. A. (2008) Nat. Rev. Cancer 8, 604–617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Katzmann D. J., Odorizzi G., Emr S. D. (2002) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3, 893–905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Piper R. C., Katzmann D. J. (2007) Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 23, 519–547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bretscher M. S. (1989) EMBO J. 8, 1341–1348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bretscher M. S. (1992) EMBO J. 11, 405–410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lamalice L., Le Boeuf F., Huot J. (2007) Circ. Res. 100, 782–794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Arthur W. T., Quilliam L. A., Cooper J. A. (2004) J. Cell Biol. 167, 111–122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bonauer A., Carmona G., Iwasaki M., Mione M., Koyanagi M., Fischer A., Burchfield J., Fox H., Doebele C., Ohtani K., Chavakis E., Potente M., Tjwa M., Urbich C., Zeiher A. M., Dimmeler S. (2009) Science 324, 1710–1713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Luque A., Gómez M., Puzon W., Takada Y., Sánchez-Madrid F., Cabañas C. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 11067–11075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Carmona G., Göttig S., Orlandi A., Scheele J., Bäuerle T., Jugold M., Kiessling F., Henschler R., Zeiher A. M., Dimmeler S., Chavakis E. (2009) Blood 113, 488–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Del Pozo M. A., Kiosses W. B., Alderson N. B., Meller N., Hahn K. M., Schwartz M. A. (2002) Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 232–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. del Pozo M. A., Price L. S., Alderson N. B., Ren X. D., Schwartz M. A. (2000) EMBO J. 19, 2008–2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Berrier A. L., Martinez R., Bokoch G. M., LaFlamme S. E. (2002) J. Cell Sci. 115, 4285–4291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Byzova T. V., Goldman C. K., Pampori N., Thomas K. A., Bett A., Shattil S. J., Plow E. F. (2000) Mol. Cell 6, 851–860 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mettouchi A., Klein S., Guo W., Lopez-Lago M., Lemichez E., Westwick J. K., Giancotti F. G. (2001) Mol. Cell 8, 115–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Teng F. Y., Wang Y., Tang B. L. (2001) Genome Biol. 2, REVIEWS3012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zhang Y., Shu L., Chen X. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 30689–30698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Skalski M., Coppolino M. G. (2005) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 335, 1199–1210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Choudhury A., Sharma D. K., Marks D. L., Pagano R. E. (2004) Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 4500–4511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kim S., Bell K., Mousa S. A., Varner J. A. (2000) Am. J. Pathol. 156, 1345–1362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Yang J. T., Rayburn H., Hynes R. O. (1993) Development 119, 1093–1105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Schlaepfer D. D., Hunter T. (1998) Trends Cell Biol. 8, 151–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Mitra S. K., Hanson D. A., Schlaepfer D. D. (2005) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 56–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.