Abstract

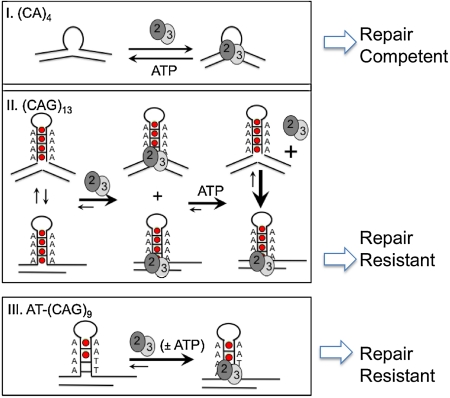

Insertion and deletion of small heteroduplex loops are common mutations in DNA, but why some loops are prone to mutation and others are efficiently repaired is unknown. Here we report that the mismatch recognition complex, MSH2/MSH3, discriminates between a repair-competent and a repair-resistant loop by sensing the conformational dynamics of their junctions. MSH2/MSH3 binds, bends, and dissociates from repair-competent loops to signal downstream repair. Repair-resistant Cytosine-Adenine-Guanine (CAG) loops adopt a unique DNA junction that traps nucleotide-bound MSH2/MSH3, and inhibits its dissociation from the DNA. We envision that junction dynamics is an active participant and a conformational regulator of repair signaling, and governs whether a loop is removed by MSH2/MSH3 or escapes to become a precursor for mutation.

Keywords: DNA repair, mismatch repair, smFRET, trinucelotide expansion

Insertion or deletion of small extrahelical loops is one of the most common mutations in human cancers (1–3), but the mechanism by which they occur is unknown. Small loops, bulges, or kinked DNA occur frequently in DNA, and provide signals for p53 recognition (4–7), recombination (8, 9), and/or most often removal by the mismatch repair system (10–14). Two heterodimeric mismatch recognition complexes, MSH2/MSH6 and MSH2/MSH3, operate in mammals with distinct, but overlapping specificities (12–14). The crystal structure (15–18), Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) (19), and single molecule fluorescence resonant energy transfer (smFRET) (19, 20) confirm that MSH2/MSH6 and Escherichia coli (MutS) preferentially bind single base mismatches or two base pair bulges. MSH2/MSH3 can recognize some base-base mismatches (21), but has a higher apparent affinity and specificity for small DNA loops composed of 2–13 bases (12–14, 22–24). Thus, defects in repair mediated by MSH2/MSH3 are poised to be a major source of insertion-deletion mutations.

The mechanism by which MSH2/MSH3 discriminates between repair-competent and repair-resistant loops (24–26), however remains enigmatic. A small (CA)4 loop of DNA can be faithfully repaired by MSH2/MSH3 both in vitro (24, 26) and in vivo (25, 27, 28). In contrast, hydrogen bonded CAG hairpin loops are not excised, and confer genomic instability through insertion and amplification of CAG repetitive tracts (29–31). Although (CA)4 loops and CAG hairpins both harbor three-way junctions, MSH2/MSH3 interacts with them distinctly (24, 26). Why one template is repaired better than the other is not known, but the consequence is remarkable: Inefficient repair of CAG loops results in mutations that underlie more than 20 hereditary neurodegenerative or neuromuscular diseases (30–33).

Here, we address the underlying basis for discriminating repair-competent and repair-resistant DNA loops by MSH2/MSH3. We find that MSH2/MSH3 binds with similar affinity to a repair-competent (CA)4 loop and to repair-resistant CAG hairpins. However, the three-way hairpin junction adopts a conformational state that traps nucleotide-bound MSH2/MSH3, and inhibits its dissociation from the hairpin. The biochemical and smFRET results imply that repair-resistant CAG hairpins provide a unique but nonproductive binding site for nucleotide-bound MSH2/MSH3, which fails to effectively couple DNA binding with downstream repair signaling. We envision that conformational regulation of small loop repair occurs at the level of the junction dynamics.

Results

Conformational Integrity of MSH2/MSH3 and the DNA “Junction” Templates.

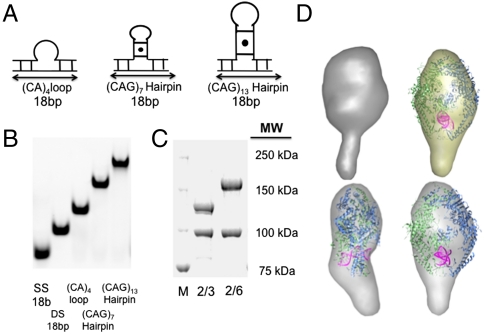

We characterized the DNA-binding affinity and nucleotide binding properties of MSH2/MSH3 bound to looped templates, either a (CA)4 loop or CAG hairpin loops of either 7 or 13 ((CAG)7 and (CAG)13) triplet repeats (Fig. 1A). Both loop and hairpin templates were constructed from two single-stranded oligonucleotides (Fig. 1A). Neither the (CA)4 loop nor the CAG stem had complementary sequences within the duplex portion of the template. Thus, the junction templates folded into stable extrahelical loops, which have been previously characterized in solution (26, 31). Folding of the CAG loops creates A/A mismatches every third base pair in the stem, for a total of three mismatches in the (CAG)7 template or a total of six mismatches in the (CAG)13 template. DNA templates were analyzed by gel electrophoresis to (i) ensure the absence of any traces of single-stranded DNA and (ii) that the DNA loops were intact, as judged by an increase in the loop size and gel mobility (Fig. 1B). Unless specifically noted, all DNA templates were synthesized containing a duplex base of 18 bases (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Conformational Integrity of Mismatch Recognition Complexes and DNA templates. (A) Schematic structure of the three-way junction DNA templates. The (CA)4 loop and CAG hairpins are centrally located in the upper unlabeled strand. The duplex base comprising eighteen base pairs, which were labeled at the 5′ end with Cy3 and at the 5′ end with Cy5 for smFRET experiments, or with a 5′ fluorescein for the FA experiments. (B) The purified templates resolved on native polyacrylamide gels and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. SS is the 18nuc single strand DNA that is the complementary strand for the looped templates, DS is the 18 bp homoduplex DNA, and the heteroduplex looped substrates are as labeled. (C) Resolution of purified human MSH2/MSH3 (middle lane) and MSH2/MSH6 (right lane) proteins by SDS-PAGE. The size markers (right) indicate the molecular weights. (D) SAXS structure of MSH2/MSH3 protein alone (top, left) or in the presence of the (CA)4 loop (top, right) overlaid on the crystal structure of human MSH2/MSH6 bound to a G-T mispaired base (11). View of the MSH2/MSH3-(CA)4 loop complex from front (bottom, right) and side (bottom, left).

The purified human MSH2/MSH3 protein (hereafter referred to as MSH2/MSH3) was also of high quality (Fig. 1C). The full-length MSH2/MSH3 was expressed and copurified as a heterodimer, and each subunit, when resolved by PAGE, migrated as a single band according to the expected molecular mass (Fig. 1C). To further test the conformational integrity of the protein, we visualized full-length MSH2/MSH3 using small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) (34, 35)(Fig. 1D). Interestingly, the high-resolution SAXS structure revealed that the N-terminal portion of the MSH3 subunit formed an unfolded “panhandle” structure, which extended beyond the heterodimeric interface of MSH2/MSH3. The handle undergoes a visible broadening and conformational change upon binding the (CA)4 loop. But otherwise, the DNA-bound heterodimeric portion of human MSH2/MSH3 was similar in conformation to that of the human MSH2/MSH6 bound to template containing a G-T mispaired base (16). Using these well characterized materials, we tested whether there were biochemical or conformational differences, which segregated with the repair-competent or repair-deficient nature of looped templates.

MSH2/MSH3 Binds Nucleotides with High Affinity at both Repair-Competent and Repair-Resistant Templates.

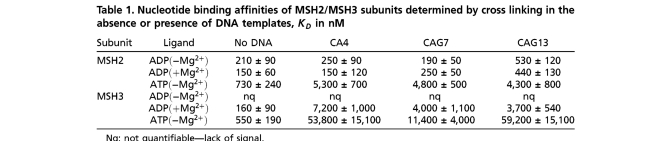

We observed little difference in nucleotide affinity when MSH2/MSH3 was prebound to repair-resistant (CAG)7 hairpin and (CAG)13 templates, or to a (CA)4 loop, which is a good substrate for MSH2/MSH3 in vitro (22, 24, 26) and in vivo (27, 28). As measured by UV-cross-linking (Fig. S1), the affinity of ADP or ATP to either subunit of DNA-bound MSH2/MSH3 was substantially weaker when MSH2/MSH3 was bound to DNA (Table 1). However, the reduction in nucleotide affinity for MSH2/MSH3 did not display striking differences among (CAG)7, (CAG)13, and the (CA)4 loop templates (Table 1).

Table 1.

Nucleotide binding affinities of MSH2/MSH3 subunits determined by cross linking in the absence or presence of DNA templates, KD in nM

Nq: not quantifiable—lack of signal.

MSH2/MSH3 Binds with Similar Affinity to the Repair-Competent (CA)4 Loop and to the Repair-Resistant CAG Hairpins.

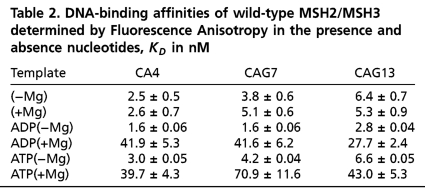

To test whether nucleotide binding to MSH2/MSH3 altered its association with DNA, we labeled each DNA template with fluorescein at the 5′-end of the bottom strand, and measured the DNA-binding affinity by fluorescence anisotropy (FA). In the absence of bound nucleotide, the apparent affinity of MSH2/MSH3 for both the (CA)4 loop and hairpin templates was in the low nanomolar range (Table 2), and was in good agreement with previous measurements (24, 26, 31). The presence of magnesium decreased the affinity of ATP-bound MSH2/MSH3 to any template by about 10-fold, but, in general, DNA binding of ADP- or ATP-bound MSH2/MSH3 did not distinguish repair-competent (CA)4 loop from the repair-resistant (CAG)7 hairpin or (CAG)13 hairpin.

Table 2.

DNA-binding affinities of wild-type MSH2/MSH3 determined by Fluorescence Anisotropy in the presence and absence nucleotides, KD in nM

MSH2/MSH3 Stabilizes a High FRET State When Bound to the Repair-Competent (CA)4 Loop.

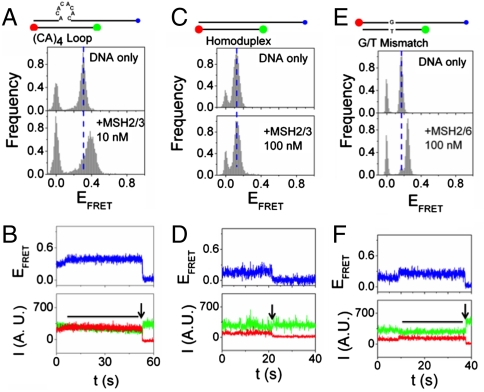

The (CA)4 loop differs structurally from the (CAG)13 DNA in that the latter forms a hairpin comprising G-C hydrogen bonded base pairs and A/A mispaired bases every third nucleotide in the stem (24, 26). To test for conformation differences between the two templates, we measured the protein-induced DNA conformational dynamics using smFRET. We prepared DNA substrates, which were identical to those used in the biochemical DNA-binding experiments, except that the bottom strand of 18 nucleotides was labeled with Cy3 (on the 5′ end, green ball) and Cy5 (on the 3′ end, red ball) (Fig. 2 A, C, E). Thus, for each template used in the smFRET experiments, the local environment of the fluorophores was identical. For both templates, the top strand at the 3′ end contains a poly-dT extension and a biotin tag for immobilization on streptavidin coated cover slips for observation (Fig. 2 A, C, E, blue ball). The extension was designed to prevent potential interaction of the fluorophores with the streptavidin surface. The smFRET was used to probe proximity between the Cy3 and Cy5 tags and the conformational dynamics of the DNA.

Fig. 2.

Binding of MSH2/MSH3 and MSH2/MSH6 to their preferred repair substrates increases FRET efficiency. The dynamics of different substrate molecules in the presence of or in the absence of added MSH2/MSH3. (A) smFRET efficiencies for MSH2/MSH3 binding to the (CA)4 loop substrate without (top) or with (bottom) MSH2/MSH3. The schematic of the labeled substrates: green ball is Cy3 label; red ball is Cy5 label (bottom); blue ball is biotin label. The protein concentration is indicated. (B) The time traces of representative donor fluorescence (green, Cy3) and acceptor fluorescence (red, Cy5). The black line indicates the time of the (CA)4 loop in the high FRET state. Time of acceptor photobleaching is indicated by black arrow. (upper) Blue traces are the corresponding FRET efficiencies. (C, D) Same as (A, B) for homoduplex substrate. (E, F) Same as (A, B) for binding of MSH2/MSH6 to a G/T mismatched substrate.

We determined the FRET efficiency (EFRET) values for hundreds of individual molecules. In the absence of protein, the distribution of EFRET for (CA)4 substrates was a single narrow peak at EFRET ∼ 0.31 (Fig. 2A, DNA only; the peak at EFRET = 0 represents substrates with an inactive acceptor). In addition to the EFRET population distribution, we followed the dynamics of each individual FRET pair by plotting time traces of donor (Cy3) and acceptor (Cy5) emission. However, there were no observable transitions within our time resolution. To determine that the transitions were fast but not absent, we measured the recovery rate of the acceptor dye intensity from the transitions to nonfluorescent states in the presence of 2-mercaptoethanol. We compared results for the (CA)4 loop relative to the homoduplex DNA (with an identical local environment of the fluorescent dyes). The recovery of the intensity for (CA)4 loop was an order of magnitude faster then the homoduplex DNA (Fig. S2). The recovery is facilitated by close proximity (2–3 nm or closer) of the donor and acceptor. Thus, the ends of the CA4 loop substrate came into close proximity confirming that there were conformational fluctuations, even though they were not observable within our time resolution.

Addition of MSH2/MSH3 to the (CA)4 loop template, in the absence of nucleotides, led to the appearance of a new EFRET peak (bound state, “high FRET”) at EFRET ∼ 0.4 (Fig. 2A, +MSH2/MSH3). The population in the high FRET state increased with protein until the entire population had shifted to EFRET ∼ 0.4 (Fig. 2A, +MSH2/MSH3). Consistent with high affinity binding (Table 2), the high FRET state saturated at a protein concentration in the nanomolar range (Fig. 2A, +MSH2/MSH3). Thus, MSH2/MSH3 formed a stable complex with the repair-competent (CA)4 loop template in which the two ends of the heteroduplex loop were positioned more closely, suggestive of bending.

To monitor the conformational dynamics of the transitions, we followed individual Cy3 (green) and Cy5 (red) emission traces for the MSH2/MSH3-(CA)4 loop complex (Fig. 2B, the calculated FRET efficiency curves are displayed in blue). The observation time was limited typically to less than 60 s by photodestruction of the acceptor (indicated by black arrows, Fig. 2B). The single molecule traces did not vary significantly (Fig. 2B). A few traces captured conformational transitions (Fig. 2B, blue trace) consistent with detection of a protein-binding event (Fig. 2B, blue trace). However, there were no observable dynamics within our time resolution (Fig. 2B, black line), and the lifetime of the average transition was longer than our maximum observation time (Fig. S2). Similar results were obtained when MSH2/MSH3 bound to a comparably labeled A2 bulge, which is also a template for MSH2/MSH3-dependent repair (Fig. S3).

We evaluated additional control DNA templates. MSH2/MSH3 has weak affinity and rapidly dissociates from homoduplex DNA (24, 26, 31). Consistent with these properties, no high smFRET population was observable when MSH2/MSH3 was added to homoduplex DNA, even at very high protein concentration (Fig. 2 C and D). Both MutS and MSH2/MSH6 bend G-T mismatched DNA at the site of the mismatch (15, 16, 18). Thus, we purified MSH2/MSH6 and added it to a comparably labeled G-T base mismatch template. Indeed, for an MSH2/MSH6 complex, we observed a high FRET shift, (Fig. 2E), which was similar in magnitude to that induced by MSH2/MSH3 on the (CA)4 loop (Fig. 2C). The single molecule traces indicated that the high FRET state was stable (black horizontal line, Fig. 2F). MSH2/MSH6 does not bind to the (CA)4 loop (26, 31), and no high smFRET population was observable when MSH2/MSH6 was added to that template, even at very high protein concentration. Thus, MSH2/MSH6 and MSH2/MSH3 complexes displayed similar transitions when bound to their preferred repair-competent templates with an estimated bending angle of 40 to 45° (Fig. S4).

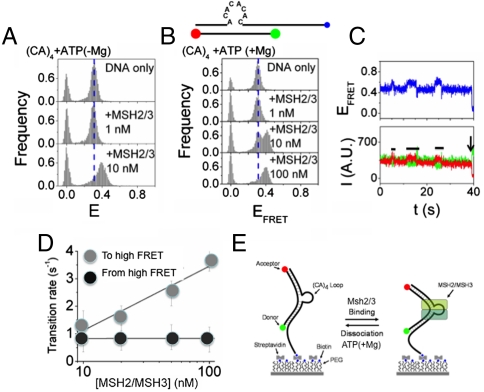

Nucleotide Binding Increases the Dissociation of MSH2/MSH3 from the (CA)4 Loop Under Hydrolytic Conditions.

MSH2/MSH6 and MSH2/MSH3 couple DNA binding and ATP hydrolysis to initiate downstream repair (11–13). Thus, we tested the effects of ATP binding and hydrolysis on the conformational dynamics of the MSH2/MSH3-bound (CA)4 substrate. ATP was added to a complex containing MSH2/MSH3-bound (CA)4 loop DNA in the presence (+Mg) or absence (-Mg) of magnesium, and distribution of smFRET efficiencies was measured under both hydrolyzing and nonhydrolyzing conditions (Fig. 3). Induction of the high FRET state by DNA-bound MSH2/MSH3 was independent of both magnesium (Fig. S5) and nucleotide binding (Fig. 2A and Fig. 3 A and B). ATP(+Mg) binding weakened the affinity of MSH2/MSH3 for the (CA)4 DNA (Table 2), and more nucleotide-bound MSH2/MSH3 was required to saturate the high FRET shift (Fig. 3B) relative to the absence of nucleotide (Fig. S5). However, ATP binding, under hydrolytic conditions, resulted in a striking alteration in the dynamics of MSH2/MSH3 binding (compare Fig. 2B and Fig. 3C). Multiple transitions between high FRET states and low FRET states were obvious in the single molecule traces, and the lifetime of nucleotide-bound MSH2/MSH3 on the (CA)4 loop dropped from minutes (Fig. 2B) to seconds (Fig. 3C). Similar results were obtained when ADP(+Mg) was the added nucleotide (Fig. S6). Thus, MSH2/MSH3 binding was sufficient to stabilize the high FRET state, and binding of ATP or ADP under hydrolytic conditions increased dissociation of MSH2/MSH3 from the (CA)4 loop.

Fig. 3.

ATP increases dissociation of MSH2/MSH3 from a (CA)4 loop substrate. FRET efficiency histograms for MSH2/MSH3 binding to the (CA)4 substrate at different protein concentrations in the presence of 100 μM ATP (A) without MgCl2 and (B) with 5 mM MgCl2. The MSH2/MSH3 concentration is indicated. (C) The dynamics of the (CA)4 substrate upon MSH2/MSH3 binding in (B). The time traces of representative donor fluorescence (green, Cy3) and acceptor fluorescence (red, Cy5). The black line indicates the time of the (CA)4 loop in the high FRET state. Time of acceptor photobleaching is indicated by black arrow. (upper) Blue traces are the corresponding FRET efficiencies. (D) Time traces like the one shown in (C) analyzed in a two state system using a Hidden Markov Model (36) to determine the average transition rates from initial to high and high to initial FRET states. The transition rates from the initial to high FRET states depends on protein concentration (gray balls), while the transition rates from high to initial FRET state were independent of the protein concentration (black balls). (E) Model for conformational dynamics observed for MSH2/MSH3 binding to (CA)4 loop substrate: MSH2/MSH3 binds to the a high FRET state of the (CA)4 loop, while addition of ATP or ADP under hydrolytic conditions increases dissociation of MSH2/MSH3 from the (CA)4 loop. The high FRET state is indicated as a bent structure.

To determine the binding and dissociation kinetics, we applied a hidden Markov model (36) to hundreds of time traces for several MSH2/MSH3 concentrations to generate robust measures of the average transition times (Fig. 3D). We found that the transition rate to the high FRET state increased with protein concentration, but the transition rate back to the initial FRET state was independent of protein concentration. Collectively, these findings indicated that the shift to the high FRET state depended on MSH2/MSH3 binding to the (CA)4 loop, while the reverse transition rate arose from MSH2/MSH3 dissociation (Fig. 3E).

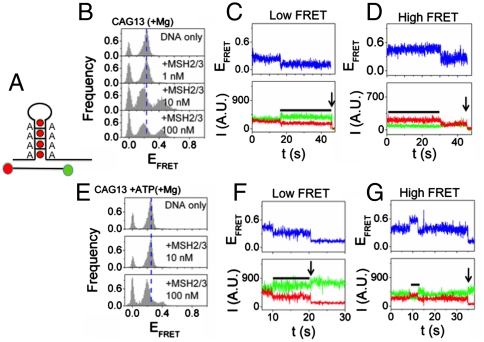

Binding of MSH2/MSH3 to the Repair-Deficient (CAG)13 Hairpin Results in the Appearance of a Unique Conformational Population.

Both the (CAG)13 hairpin and the (CA)4 loops bind well to MSH2/MSH3 (Table 2), but only the (CA)4 loop is accurately excised and repaired in vitro (24, 26) and in vivo (27, 28). Therefore, we tested whether the conformational dynamics of the (CAG)13 hairpin might be relevant to its repair-deficient nature.

The (CAG)13 hairpin DNA (Fig. 4A) displayed a relatively broad distribution of FRET efficiency, around EFRET ∼ 0.3 (Fig. 4B, DNA only). Remarkably, binding of MSH2/MSH3 to the (CAG)13 hairpin resulted in two new FRET populations (Fig. 4B, +MSH2/MSH3), one of which was similar to that observed from the (CA)4 loop. The high and a low FRET distributions of the (CAG)13 hairpin, around EFRET ∼ 0.43 and EFRET ∼ 0.20, respectively, had the same dependence on MSH2/MSH3 concentration (Fig. 4B, +MSH2/MSH3). Each FRET state was stable, with an average lifetime longer than 30 s (Fig. 4 C and D). Thus, in contrast to (CA)4 loops, the MSH2/MSH3-bound (CAG)13 hairpin adopted two conformational populations in which and the majority of the ends (65%) had moved apart.

Fig. 4.

Repair-resistant (CAG)13 template traps nucleotide-bound MSH2/MSH3 in the low FRET state. (A) A fold back loop of CAG DNA forms with A/A mispaired base every three nucleotides. Green ball is Cy3 label; Red ball is Cy5 label (bottom). (B) FRET efficiency for MSH2/MSH3 binding to the (CAG)13 hairpin in the absence of nucleotides. The FRET efficiency histograms indicate that MSH2/MSH3 binding induces a high FRET state and a low FRET state relative to the substrate alone. Individual time traces of the low (C) and high (D) FRET states. The time traces of representative donor fluorescence (green, Cy3) and acceptor fluorescence (red, Cy5). Black bars indicate the binding event, and the arrows indicate photo bleaching of the acceptor dye. (E) Addition of ATP to (B) strongly reduces the relative abundance of the high FRET state compared to the low FRET state. (F) The individual time traces indicate that the low FRET state remains stable and (G) the time in the high FRET state is shorter in the presence of ATP relative to its absence (D).

Surprisingly, the high FRET state (35% of ends) largely disappeared when (CAG)13-bound MSH2/MSH3 was occupied with nucleotide (Fig. 4E, +MSH2/MSH3). Under hydrolytic conditions, addition of ATP to (CAG)13-bound MSH2/MSH3 shifted the equilibrium populations towards the low FRET state (compare Fig. 4 B and E). Analysis of the single molecule traces indicated that ATP(+Mg) occupancy of MSH2/MSH3 significantly shortened the average lifetime for the high FRET state to around 5–10 s (Fig. 4G, horizontal black line). Under the same conditions, the low FRET state was stable, and dissociation was rarely observed (Fig. 4F). Under hydrolytic conditions, the FRET efficiencies for ATP(+Mg) were similar to those of ADP(+Mg) (Fig. S7). Thus, the repair-deficient (CAG)13 template differed from the repair-competent (CA)4 loop: nucleotide occupancy of MSH2/MSH3 promoted its dissociation from the high FRET state and the nucleotide-bound MSH2/MSH3 was, instead, trapped in the low FRET state.

The differential dynamics between the repair-resistant (CAG)13 hairpin and the repair-competent (CA)4 loop templates were striking. The shift to the low FRET state could not be explained by differential affinity of nucleotide-bound MSH2/MSH3: the biochemical data indicated that nucleotide binding and DNA-binding affinity of MSH2/MSH3 to the (CAG)13 hairpin and the (CA)4 loop were similar (Table 1). The differences in MSH2/MSH3-induced DNA conformational dynamics could also not be explained by oligomerization of MSH2/MSH3 on the DNA templates. We have previously reported that the stoichiometry of MSH2/MSH3 on both the (CA)4 loop and the (CAG)13 hairpin is one heterodimer per DNA molecule as measured by sedimentation equilibrium analysis (31). Thus, models in which the low and high FRET states were stabilized by two or more MSH2/MSH3 heterodimers were unlikely.

However, two models seemed plausible. The low and high FRET states could arise if two distinct nucleotide-bound forms of MSH2/MSH3 were able to bind to the (CAG)13 hairpin, and induce distinct conformations. Alternatively, the low and high FRET states might arise if (CAG)13 template itself formed two major DNA conformations that were able to bind MSH2/MSH3. In either case, the ratio of MSH2/MSH3 and (CAG)13 template would be 1∶1. We considered both possibilities.

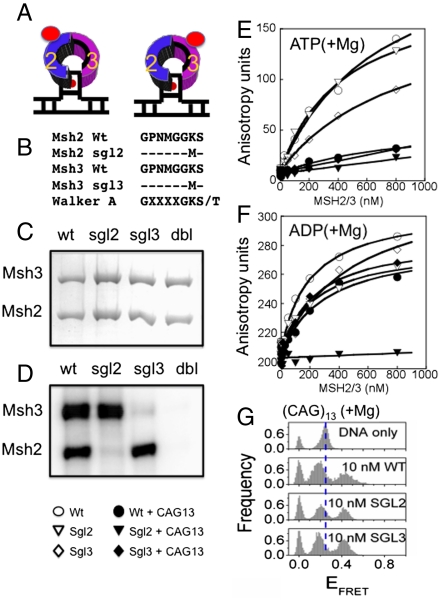

The High and Low FRET States of the (CAG)13 Hairpin Loop Do Not Arise from Binding of Distinct Nucleotide-Bound Forms of MSH2/MSH3.

Different from MSH2/MSH6, the MSH2 and MSH3 subunits of MSH2/MSH3 bind nucleotides stochastically (26), and efficient hydrolysis results in formation of ADP-MSH2/MSH3-empty and empty-MSH2/MSH3-ADP in solution. Only ADP-MSH2/MSH3-empty stably binds to the (CA)4 loop DNA (26). However, it was possible that the altered conformation of the (CAG)13 hairpin template permitted binding of both ADP-bound forms of MSH2/MSH3 (Fig. 5A). In such a model, binding of the two distinct ADP-bound forms of MSH2/MSH3 to the (CAG)13 templates would result in the high and low FRET states.

Fig. 5.

A (CAG)13 hairpin binds only one nucleotide-bound MSH2/MSH3 complex, but displays both high and low FRET states. (A) Schematic diagram of two possible MSH2/MSH3-(CAG)13 hairpin complexes with nucleotide bound in either the MSH2 or MSH3 subunit. (B) Sequences of the mutant MSH2 and MSH3 subunits aligned with the canonical Walker A box sequence motif of the wt MSH2/MSH3. The conserved Lysine residue has been replaced with a methionine in the mutant proteins to destroy the ATP binding pocket. (C) Resolution of the wild-type and mutant MSH2/MSH3 on denaturing gels. Wt, wild-type MSH2/MSH3 subunits, sgl2, Walker A box mutations in the MSH2 subunit only, sgl3, Walker A box in the MSH3 subunit only, dbl, Walker A motif mutations in both subunits. (D) Binding of [α-32P]-ATP to wild-type and mutant MSH2/MSH3 proteins analyzed by UV-cross-linking followed by resolution on denaturing gel. Only intact nucleotide binding sites bind ATP efficiently. (E) Fluorescence anisotropy measurements of Bodipy-labeled ATP binding to both wild-type and mutant MSH2/MSH3-(CAG)13 hairpin complexes. (F) Mutation of the Walker (A) box in the MSH2 subunit only inhibits binding of Bodipy labeled ADP to a MSH2/MSH3-(CAG)13 hairpin complex. (G) Association of nucleotide-bound wild-type and mutant MSH2/MSH3 to the (CAG)13 templates result in high and low FRET states. ATP is retained poorly in the MSH3 subunit when bound to DNA (18). Thus, sgl3 and wild type in the presence of nucleotides are similar, and sgl2 in the presence of nucleotides is the same as wt without bound nucleotides. ATP is 100 μM.

To test this hypothesis, we created mutants of MSH2/MSH3 in which only one of the Walker motifs was competent to bind nucleotides (Fig. 5B). We changed the critical lysine of the Walker A sites (GGKST/S) to a methionine in one, the other, or both of the ATP binding sites. These mutants are referred to as sgl2 (mutation in MSH2 only), sgl3 (mutation in MSH3 only), or dbl (both subunits mutated) (Fig. 5B), depending on the site(s) of the amino acid change. The amino acid substitutions had no effect on the expression of the protein relative to the WT protein, and each subunit was expressed at stoichiometric levels (Fig. 5C). Thus, we purified each mutant MSH2/MSH3 heterodimeric complex and characterized its behavior with respect to DNA and nucleotide binding.

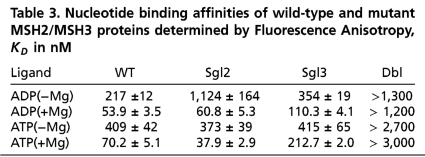

The mutant MSH2/MSH3 proteins had the expected nucleotide binding properties. As judged by X-linking, neither [α-32P]-ADP nor [α-32P]-ATP(+Mg) bound to the MSH2/MSH3 dbl (Fig. 5D, lanes 4), while sgl2 and sgl3 bound nucleotides only in their intact site (Fig. 5D, lanes 2 and 3) and wt MSH2/MSH3 bound both sites equally (Fig. 5D, lanes 1), as measured by anisotropy, both sgl2 and sgl3 bound ADP with equivalent affinity as WT MSH2/MSH3 (Table 3). Thus, mutation in one site did not influence the nucleotide affinity in the other. Consequently, each mutant MSH2/MSH3 heterodimer was able to form a single nucleotide-bound complex, which varied only in the nucleotide-bound subunit.

Table 3.

Nucleotide binding affinities of wild-type and mutant MSH2/MSH3 proteins determined by Fluorescence Anisotropy, KD in nM

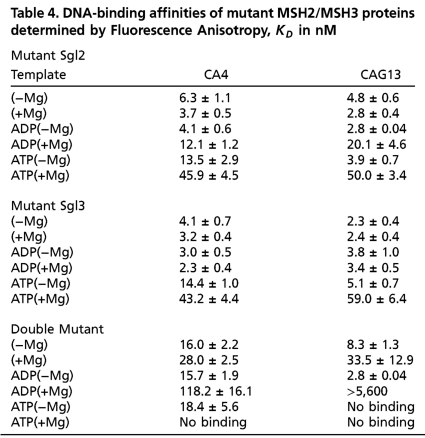

We next tested how well the mutant MSH2/MSH3 proteins could bind to DNA, by measuring FA of labeled DNA substrates (Table 4). With the exception of dbl, wt and mutant MSH2/MSH3 had good affinity for the (CAG)13 hairpin in the presence of nucleotide (Table 4). We measured nucleotide affinity for the DNA-bound wt and MSH2/MSH3 mutants using fluorescently labeled ATP and ADP (Fig. 5 E and F). ATP bound well to the MSH2 or MSH3 subunit of wt, sgl2, or sgl3 as free heterodimers (Fig. 5E, open symbols), but none of these ATP-bound complexes adopted a stable ATP-bound state on the (CAG)13 hairpin DNA (Fig. 5E, closed symbols). ADP(+Mg) retained high affinity for (CAG)13-bound wt and sgl3, but had little affinity for the (CAG)13-bound sgl2 mutant (Fig. 5F, solid inverted triangles). Thus, nucleotide-bound MSH2/MSH3 associated to the (CAG)13 hairpin only when nucleotide occupied the MSH2 subunit and the MSH3 subunit was empty (sgl3), yet both high and low FRET states were observed (Fig. 5G). These experiments argued against a model where the high and low FRET states arose from binding of two distinct nucleotide-bound MSH2/MSH3 complexes to the (CAG)13 hairpin.

Table 4.

DNA-binding affinities of mutant MSH2/MSH3 proteins determined by Fluorescence Anisotropy, KD in nM

The Repair-Resistant (CAG)13 Template Traps MSH2/MSH3 in the Low FRET State.

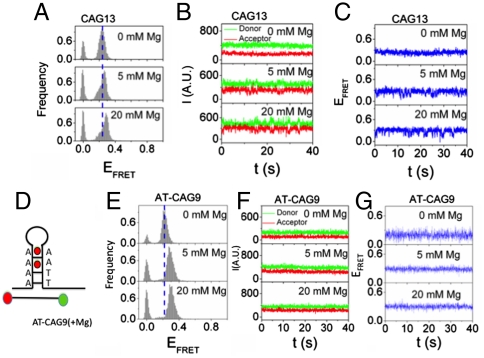

The experimental results raised the possibility that the (CAG)13 template adopted more than one DNA conformation for binding of ADP-MSH2/MSH3-empty. Indeed, in the absence of protein, by increasing MgCl2 concentrations, we could resolve the broad FRET efficiency peak at EFRET ∼ 0.24 into two closely spaced DNA populations around EFRET ∼ 0.24 and EFRET ∼ 0.21 (Fig. 6A). The single molecule traces indicated that these two DNA populations were rapidly interconverting (Fig. 6 B and C). The (CAG)13 DNA can be characterized as a three-way DNA junction with two homoduplex and one heteroduplex arm (the (CAG)13 stem). Perfectly paired three-way DNA junctions form a single stable conformation (37). Thus, we hypothesized that the unpaired A-A mispaired bases in the stem of a (CAG)7 or (CAG)13 loops might allow rearrangement of the junction into two major conformational populations of the DNA. If the (CAG)13 DNA intrinsically adopted high and low FRET states, then MSH2/MSH3 might preferentially bind to one.

Fig. 6.

The (CAG)13 loop intrinsically adopts more than one conformational state in the absence of protein. (A) The FRET efficiency histograms of the (CAG)13 substrate in the absence of protein. Increasing MgCl2 concentration resolves the presence of two FRET states. (B) Few transitions are observed within the time resolution for concentrations below 5 mM MgCl2, but become more apparent at 20 mM MgCl2. (C) Blue trace is the corresponding FRET efficiency. (D) A schematic of the sequence changes at the junction of the AT(CAG)9 template. The two A-A mismatches closest to the junction in the (CAG)13 substrate have been replaced by A-T pairs. (E) Conformation of AT-(CAG)9 substrate at different MgCl2 concentrations. In the absence of protein, the substrate exists in a single conformation. Addition of MgCl2 increases the shift towards higher FRET values, (F, G) but the individual time traces are not dynamic. (F) The time traces of representative donor fluorescence (green, Cy3) and acceptor fluorescence (red, Cy5), and (G) the blue traces are the corresponding efficiencies.

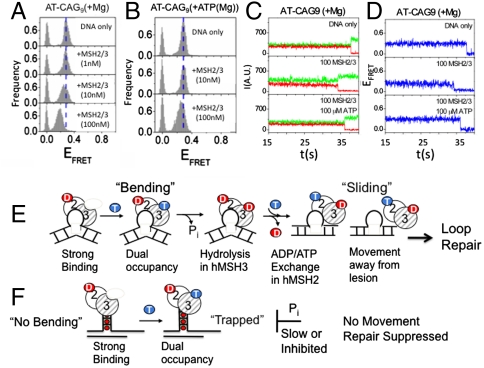

To test this idea, we stabilized the junction by converting the two A-A pairs closest to the junction of the (CAG)13 hairpin template into A-T pairs (AT-(CAG)9) (Fig. 6D). Introduction of the two A-T pairs at the base of the junction “locked” it into a single narrow distribution, which did not show two populations upon increasing MgCl2 (Fig. 6E). Moreover, AT-(CAG)9 adopted a single stable state as shown in the single molecule traces (Fig. 6 F and G). We next added MSH2/MSH3 to the AT-(CAG)9, DNA, and tested whether MSH2/MSH3 would promote the high and low FRET conformations. Remarkably, binding of MSH2/MSH3 to the AT-(CAG)9, resulted in only a low FRET conformational population (Fig. 7A). Adding ATP and MSH2/MSH3, under hydrolyzing conditions, lowered the affinity of MSH2/MSH3 to the AT-(CAG)9 hairpin (and reduced the shift) (Fig. 7B) but did not alter the overall conformation of the (CAG)13 hairpins. Furthermore, MSH2-MSH3 binding did not increase the dynamics of AT-(CAG)9; few conformation transitions were observed even when MSH2/MSH3 was in the nucleotide-bound state (Fig. 7 C and D). Thus, MSH2/MSH3 bound stably to the AT-(CAG)9 junction and did not dissociate readily from the low FRET conformation. When bound to MSH2/MSH3, the AT-(CAG)9 hairpin adopted a single stable low FRET state, which was not observed for the (CA)4 loop template under any condition tested.

Fig. 7.

The junction of the AT-(CAG)9 hairpin adopts only one stable three-way junction, from which MSH2/MSH3 does not dissociate. (A) The FRET efficiencies for binding of MSH2/MSH3 to the AT-(CAG)9 substrate in the presence of (+MgCl2) results in a single low-FRET population. (B) The FRET efficiency histograms for AT-(CAG)9 in the presence of ATP under hydrolytic conditions. The affinity of nucleotide-bound MSH2/MSH3 for the AT-(CAG)9 substrate (+MgCl2) is reduced, but binding results in the same low FRET state as observed in the absence of nucleotides. (C) The individual time traces of the AT-(CAG)9 substrate alone (top), AT-(CAG)9 bound to MSH2/MSH3 (middle), and AT-(CAG)9 bound to MSH2/MSH3 at the indicated concentrations in the presence of ATP (+Mg) (100 μM) (bottom). All traces are similar and display no dynamics. (C) The time traces of representative donor fluorescence (green, Cy3) and acceptor fluorescence (red, Cy5), and (D) the blue traces are the corresponding FRET efficiencies. (E) Proposed model for conformational regulation of loop repair by MSH2/MSH3 at three-way DNA junctions. The conformational flexibility of the substrate determines the possible binding modes of MSH2/MSH3. (F) Binding of MSH2/MSH3 to a (CA)4 loop binds, bends DNA. Upon downstream nucleotide hydrolysis and exchange, MSH2/MSH3 adopts a doubly bound form which is verify and to leave the lesion to signal downstream repair by the MMR machinery. (G) The straightened (CAG)13 hairpin junction traps nucleotide-bound MSH2/MSH3 in a nonproductive complex, which cannot leave the lesion to initiate efficient repair by the MMR pathway. Successful mismatch repair couples DNA binding and ATP hydrolysis. Trapping does not allow processing of ATP in the MSH3 subunit, and prevent ADP/ATP exchange needed to leave the site. Circles with 2 and 3 represent the MSH2/MSH3 heterodimer. Red ball are ADP and blue balls are ATP.

Discussion

How insertion and deletion mutations arise in the genome and why some loops are repaired better than others are unknown. Here, we show that MSH2/MSH3 discriminates between a repair-competent and a repair-resistant loop by sensing the conformational dynamics of their three-way junctions. We propose that the conformational properties of the substrate junction govern whether a loop is removed or becomes precursor for mutation. We find the repair-competent (CA)4 substrate is intrinsically a flexible hinge with dynamics that are faster than our time resolution. MSH2/MSH3 binds and stabilizes the bent state (Fig. 7E, bending), presumably to verify the lesion. Upon nucleotide binding, the enzyme undergoes a series of rapid nucleotide-dependent steps and eventually dissociates to signal downstream repair (Fig. 7E, sliding). Indeed, the smFRET results imply that the substrate dynamics induced by nucleotide-bound MSH2/MSH3 at the (CA)4 loop have a nonexponential dwell-time distribution consistent with the presence of more than one kinetic step (Fig. S8). Rapid association and dissociation poises the protein complex to verify and move away from the lesion and to initiate interactions necessary for downstream signaling.

The repair-resistant (CAG)13 junction intrinsically adopts discrete conformational states as indicated by the two-state-FRET distribution (most noticeable at high MgCl2 concentrations) (Figs. 4 and 6). Unliganded MSH2/MSH3 recognizes both of these conformational states with similar affinity and further separates them. MSH2/MSH3 can convert some of the hairpin junctions into a repair-competent bent state. However, upon nucleotide binding, MSH2/MSH3 dissociates from the bent state and, instead is trapped by a junction configuration from which it cannot dissociate (Fig. 7F, trapped). The nucleotide-bound protein becomes “stuck” on the lesion, and likely cannot carry out the steps leading to ADP/ATP exchange, which is critical for dissociation and downstream repair. These findings imply that the repair-resistant CAG hairpins provide a unique but nonproductive binding site for nucleotide-bound MSH2/MSH3, which fails to effectively couple DNA binding with ATP hydrolysis.

The AT-(CAG)9, junction differs by only two nucleotides relative to the (CAG)13 hairpin, but only one intrinsic conformation is available for MSH2/MSH3 binding. Similar to the repair-resistant (CAG)13 hairpin loop, MSH2/MSH3 cannot convert the AT-(CAG)9 into a bent state, rather, the template exists in a single junction conformation, which captures MSH2/MSH3. The residence of MSH2/MSH3 on the AT-(CAG)9, is long lived, whether or not the protein complex is bound with nucleotides (Fig. 7 C and D). Thus, dynamics of the junction is an active participant in directing loop conformation. We envision that conformational regulation of small loop repair occurs at the level of the junction dynamics.

This mechanism has strong mechanistic implications for a second class of mismatch repair deficits. Mutations in the MMR (Mismatch Repair) machinery lead to an increase in spontaneous mutation rate, which is typically referred to as a mutator phenotype (1–3). For example, about 15% of patients with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer have widespread genome instability, characterized by single base changes or changes in copy number at repetitive tracts (1–3). The mutational spectrum in this class of MMR deficits reflects the inability of the mutated MMR machinery to correct postreplicative errors throughout the genome (1–3). Our data provide a plausible mechanism for a second class of MMR defects in which the lesion itself prevents its processing by the normal repair machinery (32). Defective repair arises when the repair-resistant loops trap the MMR proteins during recognition of the lesion and they remain uncorrected. The resulting insertion and deletion mutations, in this case, will be “site-specific” in that they are limited to particular locations where the repair-resistant lesions reside. The properties of trinucleotide expansion characterize this type of mutation.

We do not as yet know whether the unusual junction dynamics provides a general mechanism underlying all “class two” insertion/deletion mutations or whether the unusual dynamics are restricted to only some junctions. However, our results provide, at the structural level, a glimpse into why some loops are recognized differently by MSH2/MSH3 and imply that the junction dynamics is at least one component in a complex process that leads to mutation.

Integration of our biochemical and smFRET data clarifies two key issues bearing on the expansion mutation. First, the role of MSH2/MSH3 ATP hydrolysis activity in causing expansion has been unclear. A G674A Walker A site mutation in the MSH2 subunit suppresses CTG (Cytosine-thymine-guanine) expansion in mice (38), and prevents GAA (Guanine-adenine-adenine) deletion in yeast (39), implying that ATP hydrolysis in the MSH2 subunit is a requisite step in expansion. However, we observe in our biochemical measurements that the G674A Walker A site mutant in the MSH2 subunit binds ATP poorly, if at all, in the context of MSH2/MSH3 (Fig. S9). Thus, the G674A Walker A site mutation does not block hydrolysis per se, but failure to bind ATP in the MSH2 subunit prevents formation of ADP-bound MSH2/MSH3, the major lesion-binding form (26).

While ATP hydrolysis is reduced in MSH2/MSH3-bound CAG hairpin (31, 40), the apparent nucleotide affinity and the kcat/KM for ATP hydrolysis are similar for MSH2/MSH3 when bound to a repair-competent (CA)4 loop and the repair-resistant (CAG)13 hairpin (31, 40). Thus, a second issue is the extent to which the recognition properties of MSH2/MSH3 differ between these two types of loops. smFRET resolves discrete populations, and our data provide definitive evidence that MSH2/MSH3 captures a distinct conformation of the (CAG)13 hairpin, which significantly lengthens the lifetime of bound protein relative to repair-competent (CA)4 loop. Because MSH2/MSH3 binds with equal apparent affinity to the (CA)4 and the CAG hairpin templates, the kcat/KM is expected to be similar, but the altered recognition properties of MSH2/MSH3 on the low FRET population cannot be resolved in bulk measurements (40). The time scale of the changes requires sensitive, high-resolution techniques to observe them. Because DNA binding inhibits ATP hydrolysis for MSH2/MSH6 (41, 42) and MSH2/MSH3 (31, 40), the longer lifetime of the MSH2/MSH3 on the repair-resistant template implies a reduction of ATP binding and/or hydrolytic activity in the straightened conformation (31). Collectively, our proposed model provides a basis for how an intact MMR complex can become inefficient when bound to particular types of loops. The junction dynamics are poised to be a pivot point for coupling DNA loop binding and ATP hydrolysis by an intact MSH2/MSH3 to outcomes of mutation or repair.

Methods

Detailed methods are provided as SI Methods.

Protein Purification.

His-tagged human MSH2/MSH3 and MSH2/MSH3 was overexpressed in SF9 insect cells using a pFastBac dual expression system (GIBCO-BRL) and purified as described previously (24, 26).

Nucleotides and Oligonucleotides.

Oligonucleotides used in the binding studies were obtained from Operon or IDT, SI Methods. Fluorescently labeled oligos were labeled at the 5′ end with fluoresceine for single label experiments. Nucleotides of the highest grade were purchased from Sigma. [α32P]-ATP was purchased from Perkin Elmer, and [α32P]-ADP was derived by incubation of [α32P]-ATP with hexokinase. All preparations of nucleotides used contained less than 1% contamination of other nucleotides.

UV-Cross-Linking, DNA, Nucleotide Binding, Fluorescence Anisotropy.

Experiments were performed as described previously (26).

SAXS.

Data were collected at the SIBYLS (beamline 12.3.1), and analyzed with the automated pipeline described previously (34). The Atsas program suite (35) and GASBOR (43) were used to extract shapes from SAXS scattering curves (see SI Methods for more details).

Single Molecule FRET.

The single molecule FRET experiments were performed on a prism-type total internal reflection microscope which features 532 nm excitation from a Nd:YAG laser (50 mW, CrystaLaser), as previously described (44, 45).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

This work was supported by the Mayo Foundation, the National Institutes of Health Grants NS40738 (C.T.M.), GM066359 (C.T.M.), NS062384 (to C.T.M.), and CA092584 (C.T.M.), NS060115 (to C.T.M.) and National Science Foundation PHY-0748642 (I.R.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

See Author Summary on page 17247.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1105461108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Fishel R. The selection for mismatch repair defects in hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer: revising the mutator hypothesis. Cancer Res. 2001;61:7369–7374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peltomaki P. Deficient DNA mismatch repair: a common etiologic factor for colon cancer. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:735–740. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.7.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wei K, Kucherlapati R, Edelmann W. Mouse models for human DNA mismatch-repair gene defects. Trends Mol Med. 2002;8:346–353. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(02)02359-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Y-H, Griffith J. The effects of bulge composition and flanking sequence on the kinking of DNA by bulged bases. Biochemistry. 1991;30:1359–1363. doi: 10.1021/bi00219a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Y-H, Barker P, Griffith JD. Visualization of diagnostic heteroduplex DNAs from cystic fibrosis deletion heterozygotes provides an estimate of the kinking of DNA by bulged bases. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:4911–4915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee S, Elenbaas B, Levine A, Griffith JD. p53 and its 14 kDa C terminal domain recognize primary DNA damage in the form of insertion/deletion mismatches. Cell. 1995;81:1013–1020. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Degtyareva N, Subramanian D, Griffith JD. Analysis of the binding of p53 to DNAs containing mismatched and bulged bases. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:8778–8784. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006795200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Y-H, Bortner C, Griffith JD. RecA binding to bulge and mismatch containing DNA: certain single base mismatches provide signals for RecA binding equal to multiple base bulges. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:17571–17577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Subramanian D, Griffith JD. Interactions between p53, hMSH2-hMSH6 and HMG I(Y) on Holliday Junctions and Bulged Bases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:2427–2434. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.11.2427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fishel R, Ewel A, Lee S, Lescoe MK, Griffith JD. Binding of mismatches microsatellite DNA sequences by the human MSH2 protein. Science. 1994;266:1403–1405. doi: 10.1126/science.7973733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gradia S, et al. hMSH2-hMSH6 forms a hydrolysis-independent sliding clamp on mismatched DNA. Mol Cell. 1999;3:255–261. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80316-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iyer RR, Pluciennik A, Burdett V, Modrich PL. DNA mismatch repair: functions and mechanisms. Chem Rev. 2006;106:302–323. doi: 10.1021/cr0404794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kunkel TA, Erie DA. DNA mismatch repair. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005;74:681–710. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schofield MJ, Hsieh P. DNA mismatch repair: molecular mechanisms and biological function. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2003;57:579–608. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Obmolova G, Ban C, Hsieh P, Yang W. Crystal structures of mismatch repair protein MutS and its complex with a substrate DNA. Nature. 2000;407:703–710. doi: 10.1038/35037509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lamers MH, et al. The crystal structure of DNA mismatch repair protein MutS binding to a GxT mismatch. Nature. 2000;407:711–717. doi: 10.1038/35037523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alani E, et al. Crystal structure and biochemical analysis of the MutS.ADP.beryllium fluoride complex suggests a conserved mechanism for ATP interactions in mismatch repair. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:16088–16094. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M213193200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Warren JJ, et al. Structure of the human MutSalpha DNA lesion recognition complex. Mol Cell. 2007;26:579–592. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tessmer I, et al. Mechanism of MutS searching for DNA mismatches and signaling repair. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:36646–36654. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805712200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sass LE, Lanyi C, Weninger K, Erie DA. Single-molecule FRET TACKLE reveals highly dynamic mismatched DNA-MutS complexes. Biochemistry. 2010;49:3174–3190. doi: 10.1021/bi901871u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harrington JM, Kolodner RD. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Msh2-Msh3 acts in repair of base-base mispairs. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:6546–6554. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00855-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palombo F, et al. hMutSbeta, a heterodimer of hMSH2 and hMSH3, binds to insertion/deletion loops in DNA. Curr Biol. 1996;6:1181–1184. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)70685-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Acharya S, et al. hMSH2 forms specific mispair-binding complexes with hMSH3 and hMSH6. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13629–13634. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilson T, Guerrette S, Fishel R. Dissociation of mismatch recognition and ATPase activity by hMSH2-hMSH3. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:21659–21664. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bill CA, Taghian DG, Duran WA, Nickoloff JA. Repair bias of large loop mismatches during recombination in mammalian cells depends on loop length and structure. Mutat Res. 2001;485:255–265. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(01)00065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Owen BA, Lang WH, McMurray CT. The nucleotide binding dynamics of human MSH2-MSH3 are lesion dependent. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:550–557. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Genschel J, Littman SJ, Drummond JT, Modrich P. Isolation of MutSbeta from human cells and comparison of the mismatch repair specificities of MutSbeta and MutSalpha. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:19895–19901. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.31.19895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marsischky GT, Filosi N, Kane MF, Kolodner RD. Redundancy of Saccharomyces cerevisiae MSH3 and MSH6 in MSH2-dependent mismatch repair. Genes Dev. 1996;10:407–420. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.4.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miret JJ, Pessoa-Brandao L, Lahue RS. Instability of CAG and CTG trinucleotide repeats in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:3382–3387. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.6.3382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McMurray CT. Trinucelotide repeat instability during human devlopment. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:786–799. doi: 10.1038/nrg2828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Owen BA, et al. (CAG)(n)-hairpin DNA binds to Msh2-Msh3 and changes properties of mismatch recognition. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:663–670. doi: 10.1038/nsmb965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McMurray CT. Hijacking of the mismatch repair system to cause CAG expansion and cell death in neurodegenerative disease. DNA Repair. 2008;7:1121–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2008.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brouwer JR, Willemsen R, Oostra BA. Microsatellite repeat instability and neurological disease. Bioessays. 2009;31:71–83.28. doi: 10.1002/bies.080122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hura GL, et al. Robust, high-throughput solution structural analyses by small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) Nat Methods. 2009;6:606–612. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Konarev PV, Petoukhov MV, Volkov VV, Svergun DI. ATSAS 2.1, a program package for small-angle scattering data analysis. J Appl Crystallogr. 2006;39:277–286. doi: 10.1107/S0021889812007662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McKinney SA, Joo C, Ha T. Analysis of single-molecule FRET trajectories using hidden Markov modeling. Biophys J. 2006;91:1941–1951. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.082487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duckett DR, Lilley DM. The three-way DNA junction is a Y-shaped molecule in which there is no helix-helix stacking. EMBO J. 1990;9:1659–1664. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08286.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tome S, et al. MSH2 ATPase domain mutation affects CTG*CAG repeat instability in transgenic mice. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000482. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim H-M, et al. Chromosome fragility at GAA tracts in yeast depends on repeat orientation and requires mismatch repair. EMBO J. 2008;27:2896–2906. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tian L, et al. Mismatch recognition protein MutSbeta does not hijack (CAG)n hairpin repair in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:20452–20456. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C109.014977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mazur DJ, Mendillo ML, Kolodner RD. Inhibition of Msh6 ATPase activity by mispaired DNA induces a Msh2(ATP)-Msh6(ATP) state capable of hydrolysis-independent movement along DNA. Mol Cell. 2006;22:39–49. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Antony E, Hingorani MM. Mismatch recognition-coupled stabilization of Msh2-Msh6 in an ATP-bound state at the initiation of DNA repair. Biochemistry. 2003;42:7682–7693. doi: 10.1021/bi034602h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Svergun DI, Petoukhov MV, Koch MH. Determination of domain structure of proteins from X-ray solution scattering. Biophys J. 2001;80:2946–2953. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76260-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rasnik I, McKinney SA, Ha T. Nonblinking and long-lasting single-molecule fluorescence imaging. Nat Methods. 2006;11:891–893. doi: 10.1038/nmeth934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Myong S, Rasnik I, Joo C, Lohman TM, Ha T. Repetitive shuttling of a motor protein on DNA. Nature. 2005;437:1321–1325. doi: 10.1038/nature04049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]