Abstract

Although best known for its ability to cause severe pneumonia in people whose immune defenses are weakened, Legionella pneumophila and Legionella longbeachae are two species of a large genus of bacteria that are ubiquitous in nature, where they parasitize protozoa. Adaptation to the host environment and exploitation of host cell functions are critical for the success of these intracellular pathogens. The establishment and publication of the complete genome sequences of L. pneumophila and L. longbeachae isolates paved the way for major breakthroughs in understanding the biology of these organisms. In this review we present the knowledge gained from the analyses and comparison of the complete genome sequences of different L. pneumophila and L. longbeachae strains. Emphasis is given on putative virulence and Legionella life cycle related functions, such as the identification of an extended array of eukaryotic like proteins, many of which have been shown to modulate host cell functions to the pathogen’s advantage. Surprisingly, many of the eukaryotic domain proteins identified in L. pneumophila as well as many substrates of the Dot/Icm type IV secretion system essential for intracellular replication are different between these two species, although they cause the same disease. Finally, evolutionary aspects regarding the eukaryotic like proteins in Legionella are discussed.

Keywords: Legionella pneumophila, Legionella longbeachae, evolution, comparative genomics, eukaryotic like proteins, virulence

Introduction

Genomics has the potential to provide an in depth understanding of the genetics, biochemistry, physiology, and pathogenesis of a microorganism. Furthermore comparative genomics, functional genomics, and related technologies, are helping to unravel the molecular basis of the pathogenesis, evolution, and phenotypic differences among different species, strains, or clones and to uncover potential virulence genes. Knowledge of the genomes provides the basis for the application of new powerful approaches for the understanding of the biology of the organisms studied.

Although Legionella are mainly environmental bacteria, several species are pathogenic to humans, in particular Legionella pneumophila (Fraser et al., 1977; Mcdade et al., 1977) and Legionella longbeachae (Mckinney et al., 1981). Legionnaires’ disease has emerged in the second half of the twentieth century partly due to human alterations of the environment. The development of artificial water systems in the last decades like air conditioning systems, cooling towers, showers, and other aerosolizing devices has allowed Legionella to gain access to the human respiratory system. When inhaled in contaminated aerosols, pathogenic Legionella can reach the alveoli of the lung where they are subsequently engulfed by macrophages. In contrast to most bacteria, which are destroyed, some Legionella species can multiply within the phagosome and eventually kill the macrophage, resulting in a severe, often fatal pneumonia called legionellosis or Legionnaires’ disease (mortality rate of 5–20%; up to 50% in nosocomial infections; Steinert et al., 2002; Marrie, 2008; Whiley and Bentham, 2011). To replicate intracellularly L. pneumophila manipulates host cellular processes using bacterial proteins that are delivered into the cytosolic compartment of the host cell by a specialized type IV secretion system called Dot/Icm. The proteins delivered by the Dot/Icm system target host factors implicated in controlling membrane transport in eukaryotic cells, which enables L. pneumophila to create an endoplasmic reticulum-like vacuole that supports intracellular replication in both protozoan and mammalian host cells (for a review see Hubber and Roy, 2010).

An interesting epidemiological observation is, that among the over 50 Legionella species described today, strains belonging to the species L. pneumophila are responsible for over 90% of the legionellosis cases worldwide and strains belonging to the species L. longbeachae are responsible for about 5% of human legionellosis cases worldwide (Yu et al., 2002). Surprisingly, this distribution is very different in Australia and New Zealand where L. pneumophila accounts for “only” 45.7% of the cases but L. longbeachae is implicated in 30.4% of the human cases. Furthermore, among the strains causing Legionnaires’ disease, L. pneumophila serogroup 1 (Sg1) alone is responsible for over 85% of cases (Yu et al., 2002; Doleans et al., 2004) despite the description of 15 different Sg within this species. In addition, the characterization of over 400 different L. pneumophila Sg1 strains has shown that only a minority among these is responsible for causing most of the human disease (Edelstein and Metlay, 2009). Some of these clones are distributed worldwide like L. pneumophila strain Paris (Cazalet et al., 2008) others have a more restricted geographical distribution, like the recently described endemic clone, prevalent in Ontario, Canada (Tijet et al., 2010). For the species L. longbeachae two serogroups are described to date (Bibb et al., 1981; Mckinney et al., 1981). L. longbeachae Sg1 is predominant in human disease as it causes up to 95% of the cases of legionellosis worldwide and most outbreaks and sporadic cases in Australia (Anonymous, 1997; Montanaro-Punzengruber et al., 1999). The two main human pathogenic Legionella species, L. pneumophila and L. longbeachae cause the same disease and symptoms in humans (Amodeo et al., 2009), however, there exist major differences between both species in niche adaptation and host susceptibility.

-

(i)

They are found in different environmental niches, as L. pneumophila is mainly found in natural and artificial water circuits and L. longbeachae is principally found in soil and therefore associated with gardening and use of potting compost (O’Connor et al., 2007). However, although less common, the isolation of L. pneumophila from potting soil in Europe has also been reported (Casati et al., 2009; Velonakis et al., 2009). Human infection due to L. longbeachae is particularly common in Australia but cases have been documented also in other countries like the USA, Japan, Spain, England, or Germany (MMWR, 2000; Garcia et al., 2004; Kubota et al., 2007; Kumpers et al., 2008; Pravinkumar et al., 2010).

-

(ii)

As described for other Legionella species, person to person transmission of L. longbeachae has not been documented, however, the primary transmission mode seems to be inhalation of dust from contaminated compost or soil that contains the organism (Steele et al., 1990; MMWR, 2000; O’Connor et al., 2007).

-

(iii)

Furthermore, for L. pneumophila a biphasic life cycle was observed in vitro and in vivo as exponential phase bacteria do not express virulence factors and are unable to replicate intracellularly. The ability of L. pneumophila to replicate intracellularly is triggered at the post-exponential phase by a complex regulatory cascade (Molofsky and Swanson, 2004; Sahr et al., 2009). In contrast, less is known on the L. longbeachae intracellular life cycle and its virulence factors. It was recently shown that unlike L. pneumophila the ability of L. longbeachae to replicate intracellularly is independent of the bacterial growth phase (Asare and Abu Kwaik, 2007) and that phagosome biogenesis is different. Like L. pneumophila, the L. longbeachae phagosome is surrounded by endoplasmic reticulum and does not mature to a phagolysosome; however it acquires early and late endosomal markers (Asare and Abu Kwaik, 2007).

-

(iv)

Another interesting difference between these two species is their ability to colonize the lungs of mice. While only A/J mice are permissive for replication of L. pneumophila, A/J, C57BL/6, and BALB/c mice are all permissive for replication of L. longbeachae (Asare et al., 2007; Gobin et al., 2009). Resistance of C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice to L. pneumophila has been attributed to polymorphisms in Nod-like receptor apoptosis inhibitory protein 5 (naip5) allele that recognizes the C-terminus of flagellin (Wright et al., 2003; Molofsky et al., 2006; Ren et al., 2006; Lightfield et al., 2008). The current model is that L. pneumophila replication is restricted due to flagellin dependent caspase-1 activation through Naip5-Ipaf and early macrophage cell death by pyroptosis. However, although depletion or inhibition of caspase-1 activity leads to decreased targeting of bacteria to lysosomes, the mechanism of caspase-1-dependent restriction of L. pneumophila replication in macrophages and in vivo is not fully understood (Schuelein et al., 2011).

In the last years, six genomes of different L. pneumophila strains (Paris, Lens, Philadelphia, Corby, Alcoy, and 130b (Cazalet et al., 2004; Chien et al., 2004; Steinert et al., 2007; D’Auria et al., 2010; Schroeder et al., 2010) have been published. The genome sequences of all but strain 130b were completely finished. Furthermore, the sequencing and analysis of four genomes of L. longbeachae have been carried out recently (Cazalet et al., 2010). L. longbeachae strain NSW150 of Sg1 isolated in Australia from a patient was sequenced completely, and for the remaining three strains (ATCC33462, Sg1 isolated from a human lung, C-4E7 and 98072, both of Sg2 isolated from patients) a draft genome sequence was reported. A fifth L. longbeachae strain (D-4968 of Sg1, isolated in the US from a patient) was recently sequenced and the analysis of the genome sequences assembled into 89 contigs was reported (Kozak et al., 2010).

Here we will describe what we learned from the analysis and comparison of the sequenced Legionella strains. We will discuss their general characteristics and then highlight the specific features or common traits with respect to the different ecological niches and the differences in host susceptibility of these two Legionella species. Emphasis will be put on putative virulence and Legionella life cycle related functions. In the last part we will analyze and discuss the possible evolution of the identified virulence factors. Finally, future perspectives in Legionella genomics are presented.

General Features of the L. pneumophila and L. longbeachae Genomes

Legionella pneumophila and L. longbeachae each have a single, circular chromosome with a size of 3.3–3.5 Mega bases (Mb) for L. pneumophila and 3.9–4.1 Mb for L. longbeachae. For both the average G + C content is 38% (Tables 1). The L. pneumophila strains Paris and Lens each contain different plasmids, 131.9 kb and 59.8 kb in size, respectively. In strain Philadelphia-1, 130b, Alcoy, and Corby no plasmid was identified. The L. longbeachae strains NSW10 and D-4986 carry highly similar plasmids of about 70 kb and DNA identity of 99%, strains C-4E7 and 98072 also contain each a highly similar plasmid of 133.8 kb in size. Thus similar plasmids circulate among L. longbeachae strains, but they seem to be different from those found in L. pneumophila.

Table 1.

General features of the sequenced Legionella genomes.

| A. Complete and draft genomes of L. pneumophila obtained by classical or new generation sequencing | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. pneumophila | ||||||

| Paris | Lens | Philadelphia | Corby | Alcoy | 130bc | |

| Chromosome size (kb)a | 3504 (131.9)b | 3345 (59.8) | 3397 | 3576 | 3516 | 3490 |

| G + C content (%) | 38.3 (37.4) | 38.4 (38) | 38.3 | 38 | 38.4 | 38.2 |

| No. of genesa | 3123 (142) | 2980 (60) | 3031 | 3237 | 3197 | 3288 |

| No. of protein coding genesa | 3078 (140) | 2921 (60) | 2999 | 3193 | 3097 | 3141 |

| Percentage of CDS (%) | 87.9 | 88.0 | 90.2 | 86.8 | 86.0 | 87.9 |

| No. of specific genes | 225 | 181 | 213 | 144 | 182 | 386c |

| No. of 16S/23S/5S | 03/03/03 | 03/03/03 | 03/03/03 | 03/03/03 | 03/03/03 | ND |

| No. transfer RNA | 44 | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 | 42 |

| Plasmids | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| B. Complete and draft genomes of L. longbeachae obtained by classical or new generation sequencing | ||||||

| L. longbeachae | ||||||

| NSW 150 | D-4968 | ATCC33462 | 98072 | C-4E7 | ||

| Chromosome size (Kb) | 4077 (71) | 4016 (70) | 4096 | 4018 (133.8) | 3979 (133.8) | |

| G + C content (%) | 37.1 (38.2) | 37.0 | 37.0 | 37.0 (37.8) | 37 (37.8) | |

| No. of genes | 3660 (75) | 3557 (61) | – | – | – | |

| No. of 16S/23S/5S | 04/04/04 | 04/04/04 | 04/04/04 | 04/04/04 | 04/04/04 | |

| No. of contigs > 0.5–300 kb | Complete | 13 | 64 | 65 | 63 | |

| N50 contig size* | Complete | – | 138 kb | 129 kb | 134 kb | |

| Percentage of coverage** | 100% | 96.3 | 96.3 | 93.4 | 93.1 | |

| Number of SNP with NSW150 | 0 | 1900 | 1611 | 16 853 | 16 820 | |

| Plasmids | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

aUpdated annotation; CDS, coding sequence; bdata from plasmids in parenthesis; cThe 130b sequence is not a manually corrected and finished assembly, thus the high number of specific genes might be due to not corrected sequencing errors; ND, not determined; *N50 contig size, calculated by ordering all contig sizes and adding the lengths (starting from the longest contig) until the summed length exceeds 50% of the total length of all contigs (half of all bases reside in a contiguous sequence of the given size or more); SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; **for SNP detection; – not determined.

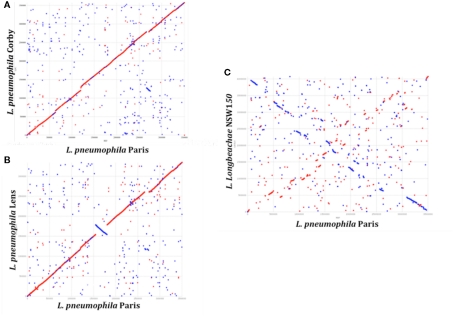

A total of ∼3000 and 3500 protein-encoding genes are predicted in the L. pneumophila and L. longbeachae genomes, respectively. No function could be predicted for about 40% of these genes and about 20% are unique to the genus Legionella. Comparative analysis of the genome structure of the L. pneumophila genomes showed high colinearity, with only few translocations, duplications, deletions, or inversions (Figures 1A,B) and identified between 6 and 11% of genes as specific to each L. pneumophila strain. Principally, the genomes contain three large plasticity zones, where the synteny is disrupted: a 260-kb inversion in strain Lens with respect to strains Paris and Philadelphia-1, a 130-kb fragment which is inserted in a different genomic location in strains Paris and Philadelphia-1 and the about 50 kb chromosomal region carrying the Lvh type IV secretion system, previously described in strain Philadelphia-1 (Segal et al., 1999). Furthermore, deletions and insertions of several smaller regions were identified in each strain, as well as regions with variable gene content. In contrast, comparison of the completed chromosome sequences of L. pneumophila and L. longbeachae shows that the two Legionella species have a significantly different genome organization (Figure 1C). Moreover only about 65% of the L. longbeachae genes are orthologous to L. pneumophila genes, whereas about 34% of all genes are specific to L. longbeachae with respect to L. pneumophila Paris, Lens, Philadelphia, and Corby (defined by less than 30% amino acid identity over 80% of the length of the smallest protein).

Figure 1.

Synteny plot of the chromosomes of L. pneumophila strains Paris, Lens, Corby, and L. longbeachae NSW150. The plot was created using the mummer software package. (A) Synteny plot of the chromosomes of strains L. pneumophila Paris and Corby (B) and strains L. pneumophila Paris and Lens and (C) strains L. pneumophila Paris and L. longbeachae NSW150. Inversions between the genomic sequences are represented in blue. Genome-wide synteny is disrupted by a 260 kb inversion (blue) and a 130 kb plasticity zone between strain L. pneumophila Paris and Lens. In contrast, synteny between L. pneumophila and L. longbeachae is highly conserved.

Analysis of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) revealed a very low SNP number of less than 0.4% among the four L. longbeachae genomes, which is significantly lower than the polymorphism of about 2% between L. pneumophila Sg1 strains Paris and Philadelphia (Table 1). Comparison of the two L. longbeachae Sg1 genomes (NSW150, ATCC33462) identified 1611 SNPs of which 1426 are located in only seven chromosomal regions mainly encoding putative mobile elements, whereas the remaining 185 SNPs were evenly distributed around the chromosome. A similar number of about 1900 SNPs were identified when comparing strains NSW150 to strain D-4968 (Table 1). In contrast, the SNP number between two strains of different Sg was higher, with about 16000 SNPs present between Sg1 and Sg2 strains (Table 1). This low SNP number and relatively homogeneous distribution of the SNPs around the chromosome suggest recent expansion for the species L. longbeachae (Cazalet et al., 2010). The sequences and their analysis are accessible at http://genolist.pasteur.fr/LegioList/.

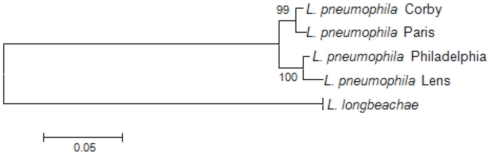

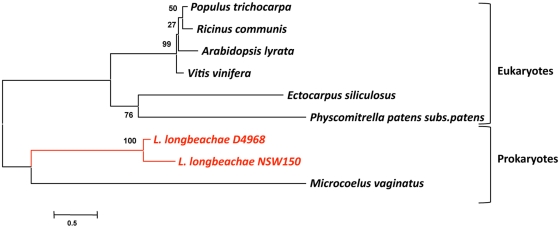

To investigate the phylogenetic relationship among the L. pneumophila and L. longbeachae strains we here used the nucleotide sequence of recN (recombination and repair protein-encoding gene) aligned based on the protein alignment. Based on an analysis of 32 protein-encoding genes widely distributed among bacterial genomes, RecN was described as the gene with the greatest potential for predicting genome relatedness at the genus or subgenus level (Zeigler, 2003). As depicted in Figure 2, the phylogenetic relationship among the four L. pneumophila strains is very high, and L. longbeachae is clearly more distant.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree showing the relationship of the sequenced L. pneumophila and L. longbeachae strains based on the recN sequence. The tree was constructed using the recN sequences of each genome and the Neighbor joining method in MEGA. L. longbeachae is indicated without strain designation, as the RecN sequence of all sequenced strains is identical and thus only one representative strain is indicated on the tree. Numbers at branching nodes are percentages of 1000 bootstrap replicates.

Diversity in Secretion Systems and Their Substrates may Contribute to Differences in Intracellular Trafficking and Niche Adaptation

The capacity of pathogens like Legionella to infect eukaryotic cells is intimately linked to the ability to manipulate host cell functions to establish an intracellular niche for their replication. Essential for the ability of Legionella to subvert host functions are its different secretion systems. The two major ones, known to be involved in virulence of L. pneumophila are the Dot/Icm type IV secretion system (T4BSS) and the Lsp type II secretion system (T2SS; Marra et al., 1992; Berger and Isberg, 1993; Rossier and Cianciotto, 2001).

For L. pneumophila type II protein secretion is critical for infection of amebae, macrophages and mice. Analyses of the L. longbeachae genome sequences showed, that it contains all genes to encode a functional Lsp type II secretion machinery (Cazalet et al., 2010; Kozak et al., 2010). Several studies, including the analysis of the L. pneumophila type II secretome indicated that L. pneumophila encodes at least 25 type II secreted substrates (Debroy et al., 2006; Cianciotto, 2009). Although this experimentally defined repertoire of type II secretion-dependent proteins is the largest known in bacteria, it may contain even more than 60 proteins as 35 additional proteins with a signal sequence were identified by in silico analyses (Cianciotto, 2009). A search for homologs of these substrates in the L. longbeachae genome sequences revealed that 9 (36%) of the 25 type II secretion system substrates described for L. pneumophila are absent from L. longbeachae (Table 2). For example the phospholipase C encoded by plcA and the chiA-encoded chitinase, which was shown to promote L. pneumophila persistence in the lungs of A/J mice are not present in L. longbeachae (Debroy et al., 2006). Thus over a third of the T2SS substrates seem to differ between L. pneumophila and L. longbeachae, a feature probably related to the different ecological niches occupied, but also to different virulence properties in the hosts.

Table 2.

Distribution of type II secretion-dependent proteins of L. pneumophila in L. longbeachae.

| L. pneumophila | L. longbeachae | Name | Product | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phila | Paris | Lens | Corby | Alcoy | 130b* | NSW | D-4968 | ||

| lpg0467 | lpp0532 | lpl0508 | lpc2877 | lpa00713 | lpw05741 | llo2721 | llb2607 | proA | Zinc metalloprotease, promotes amebal infection |

| lpg1119 | lpp1120 | lpl1124 | lpc0577 | lpa01742 | – | llo1016 | llb0700 | map | Tartrate-sensitive acid phosphatase |

| lpg2343 | lpp2291 | lpl2264 | lpc1811 | lpa03353 | lpw25361 | llo2819 | llb2504 | plaA | Lysophospholipase A |

| lpg2837 | lpp2894 | lpl2749 | lpc3121 | lpa04118 | lpw30971 | llo0210 | llb1661 | plaC | Glycerophospholipid:cholestrol transferase |

| lpg0502 | lpp0565 | lpl0541 | lpc2843 | lpa00759 | lpw05821 | – | – | plcA | Phospholipase C |

| lpg0745 | lpp0810 | lpl0781 | lpc2548 | lpa01148 | lpw08251 | llo2076 | llb3335 | lipA | Mono- and triacylglycerol lipase |

| lpg1157 | lpp1159 | lpl1164 | lpc0620 | lpa01801 | lpw12111 | llo2433 | llb2928 | lipB | Triacylglycerol lipase |

| lpg2848 | lpp2906 | lpl2760 | lpc3133 | lpa04141 | lpw31111 | llo0201 | llb1671 | srnA | Type 2 ribonuclease, promotes amebal infection |

| lpg1116 | lpp1117 | lpl1121 | lpc0574 | lpa01738 | lpw11641 | – | – | chiA | Chitinase, promotes lung infection |

| lpg2814 | lpp2866 | lpl2729 | lpc3100 | lpa04088 | lpw30701 | llo0255 | llb1611 | lapA | Leucine, phenylalanine, and tyrosine aminopeptidase |

| lpg0032 | lpp0031 | lpl0032 | lpc0032 | lpa00041 | lpw00321 | – | – | lapB | Lysine and arginine aminopeptidase |

| lpg0264 | lpp0335 | lpl0316 | lpc0340 | lpa00461 | lpw03521 | llo3103 | llb2271 | Weakly similar to bacterial amidase | |

| lpg2622 | lpp2675 | lpl2547 | lpc0519 | lpa03836 | lpw28341 | – | – | Weakly similar to bacterial cysteine protease | |

| lpg1918 | lpp1893 | lpl1882 | lpc1372 | lpa02774 | lpw19571 | llo3308 | llb2032 | celA | Endoglucanase |

| lpg2999 | lpp3071 | lpl2927 | lpc3315 | lpa04395 | lpw32851 | – | – | Predicted astacin-like zink endopeptidase | |

| lpg2644 | lpp2697 | lpl2569 | lpc0495 | lpa03870 | – | – | – | Some similarity to collagen like protein | |

| lpg1809 | lpp1772 | lpl1773 | lpc1253 | lpa02614 | lpw18401 | llo1104 | llb0603 | Unknown | |

| lpg1385 | lpp1340 | lpl1336 | lpc0801 | lpa02037 | lpw13951 | llo1474 | llb0177 | Unknown | |

| lpg0873 | lpp0936 | lpl0906 | lpc2419 | lpa01320 | lpw09571 | llo2475 | llb2883 | Unknown | |

| lpg0189 | lpp0250 | lpl0249 | lpc0269 | lpa00360 | lpw02811 | – | – | Unknown | |

| lpg0956 | lpp1018 | lpl0958 | lpc2331 | lpa01443 | lpw10421 | llo1935 | llb3498 | Unknown | |

| lpg2689 | lpp2743 | lpl2616 | lpc0447 | lpa03925 | lpw29431 | llo0361 | llb1497 | icmX | Linked to Dot/Icm type IV secretion genes |

| lpg1244 | lpp0181 | lpl0163 | – | – | lpw01541 | – | – | lvrE | Linked to Lvh type IV secretion genes |

| lpg1832 | lpp1795 | lpl1796 | lpc1276 | lpa02647 | lpw18641 | llo1152 | llb0546 | Weakly similar to VirK | |

| lpg1962 | lpp1946 | lpl1936 | lpc1440 | lpa02861 | lpw20131 | – | – | Putative peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase | |

| lpg0422 | lpp0489 | lpl0465 | lpc2921 | lpa0657 | lpw05041 | llo2801 | llb2523 | gamA | Glucoamylase |

Substrates in this list are according to Cianciotto (2009); *strain 130b is not a finished sequence and not manually curated. Thus absence of a substrate can also be due to gaps in the sequence; – means not present; NSW means L. longbeachae NSW150.

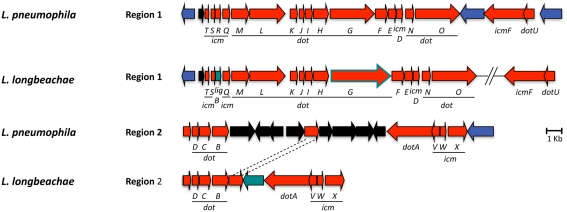

Indispensible for replication of L. pneumophila in the eukaryotic host cells is the Dot/Icm T4SS (Nagai and Kubori, 2011), which translocate a large repertoire of bacterial effectors into the host cell. These effectors modulate multiple host cell processes and in particular, redirect trafficking of the L. pneumophila phagosome and mediate its conversion into an ER-derived organelle competent for intracellular bacterial replication (Shin and Roy, 2008; Cianciotto, 2009). The Dot/Icm system is conserved in L. longbeachae with a similar gene organization and protein identities of 47–92% with respect to L. pneumophila (Figure 3). This is similar to what has been reported previously for other Legionella species (Morozova et al., 2004). The only major differences identified are that in L. longbeachae the icmR gene is replaced by the ligB gene, however, the encoded proteins have been shown to perform similar functions (Feldman and Segal, 2004; Feldman et al., 2005) and that the DotG/IcmE protein of L. longbeachae (1525 aa) is 477 amino acids larger than that of L. pneumophila (1048 aa; Cazalet et al., 2010). DotG of L. pneumophila is part of the core transmembrane complex of the secretion system and is composed of three domains: a transmembrane N-terminal domain, a central region composed of 42 repeats of 10 amino acid and a C-terminal region homologous to VirB10. In contrast, the central region of L. longbeachae DotG is composed of approximately 90 repeats. Among the many VirB10 homologs present in bacteria, the Coxiella DotG and the Helicobacter pylori Cag7 are the only ones, which also have multiple repeats of 10 aa (Segal et al., 2005). It will be challenging to understand the impact of this modification on the function of the type IV secretion system. A L. longbeachae T4SS mutant obtained by deleting the dotA gene is strongly attenuated for intracellular growth in Acanthamoeba castellanii and human macrophages (Cazalet et al., 2010, and unpublished data), is outcompeted by the wild type strain 24 and 72 h after infection of lungs of A/J mice and is also dramatically attenuated for replication in lungs of A/J mice upon single infections (Cazalet et al., 2010). Thus, similar to what is seen for L. pneumophila, the Dot/Icm T4SS of L. longbeachae is also central for its pathogenesis and the capacity to replicate in eukaryotic host cells.

Figure 3.

Alignment of the chromosomal regions of L. pneumophila and L. longbeachae coding the Dot/Icm type 4 secretion system genes. The comparison shows that all genes are highly conserved (47–92% identity) between L. pneumophila Paris and L. longbeachae. Red arrows, genes conserved between L. pneumophila and L. longbeachae (>47% identity); black arrows, L. pneumophila specific genes compared to L. longbeachae (<35% identity); blue arrows, genes conserved between L. pneumophila and L. longbeachae but located in different places of the genome; green arrows, L. longbeachae specific genes compared to L. pneumophila. Red arrow boxed in green depicts dotG. N-terminal and C-terminal parts of dotG are highly conserved while the central part composed of repeated sequences differs between L. pneumophila and L. longbeachae.

This T4SS is crucial for intracellular replication for Legionella as it secretes an exceptionally large number of proteins into the host cell. Using different methods, 275 substrates have been shown to be translocated in the host cell in a Dot/Icm T4SS dependent manner (Campodonico et al., 2005; De Felipe et al., 2005, 2008; Shohdy et al., 2005; Burstein et al., 2009; Heidtman et al., 2009; Zhu et al., 2011). Table 3 shows the distribution of the 275 Dot/Icm substrates identified in L. pneumophila strain Philadelphia and their distribution in the six L. pneumophila and five L. longbeachae genomes sequenced. Their conservation among different L. pneumophila strains is very high, as over 80% of the substrates are present in all L. pneumophila strains analyzed here. In contrast, the search for homologs of these L. pneumophila Dot/Icm substrates in L. longbeachae showed that even more pronounced differences are present than in the repertoire of type II secreted substrates. Only 98 of these 275 L. pneumophila Dot/Icm substrates have homologs in the L. longbeachae genomes (Table 3). However, the repertoire of L. longbeachae substrates seems also to be quite large, as a search for proteins that encode eukaryotic like domains and contain the secretion signal described by Nagai et al. (2005) and the additional criteria defined by Kubori et al. (2008) predicted 51 putative Dot/Icm substrates specific for L. longbeachae NSW150 (Cazalet et al., 2010) indicating that at least over 140 proteins might be secreted by the Dot/Icm T4SS of L. longbeachae. A similar number of L. longbeachae specific putative eukaryotic like proteins and effectors was predicted for strain D-4968 (Kozak et al., 2010). Examples of effector proteins conserved between the two species are RalF, VipA, VipF, SidC, SidE, SidJ, YlfA LepA, and LepB, which contribute to trafficking or recruitment and retention of vesicles to L. pneumophila (Nagai et al., 2002; Chen et al., 2004; Luo and Isberg, 2004; Campodonico et al., 2005; Shohdy et al., 2005; Liu and Luo, 2007). It is interesting to note that homologs of SidM/DrrA and SidD are absent from L. longbeachae but a homolog of LepB is present. For L. pneumophila it was shown that SidM/DrrA, SidD, and LepB act in cooperation to manipulate Rab1 activity in the host cell. DrrA/SidM possesses three domains, an N-terminal AMP-transfer domain (AT), a nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) domain in the central part and a phosphatidylinositol-4-Phosphate binding domain (P4M) in its C-terminal part. After association of DrrA/SidM with the membrane of the Legionella-containing vacuole (LCV) via P4M (Brombacher et al., 2009), it recruits Rab1 via the GEF domain and catalyzes the GDP–GTP exchange (Ingmundson et al., 2007; Machner and Isberg, 2007). Rab1 is then adenylated by the AT domain leading to inhibition of GAP-catalyzed Rab1-deactivation (Müller et al., 2010). LepB cannot bind AMPylated Rab1 (Ingmundson et al., 2007). Recently it was shown that SidD deAMPylates Rab1 and enables LepB to bind Rab1 to promote its GTP–GDP exchange (Neunuebel et al., 2011; Tan and Luo, 2011). One might assume that other proteins of L. longbeachae not yet identified may perform the functions of DrrA/SidM and SidD. Another interesting observation is, that all except four of the effector proteins of L. pneumophila that are conserved in L. longbeachae are also conserved in all sequenced L. pneumophila genomes (Table 3).

Table 3.

Distribution of 275 Dot/Icm substrates identified in strain L. pneumophila Philadelphia in the 5 sequenced L. pneumophila and 5 sequenced L. longbeachae strains.

| L. pneumophila | L. longbeachae | Name | Product | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phila | Paris | Lens | Corby | Alcoy | 130b | NSW 150 | D-4968 | AT | 98072 | C-4E7 | ||

| lpg0008 | lpp0008 | lpl0008 | lpc0009 | lpa0011 | lpw00071 | – | – | − | − | − | ravA | Unknown |

| lpg0012 | lpp0012 | lpl0012 | lpc0013 | lpa0016 | lpw00111 | – | – | − | − | − | cegC1 | Ankyrin |

| lpg0021 | lpp0021 | lpl0022 | lpc0022 | lpa0030 | lpw00221 | llo0047 | llb1841 | + | + | + | – | Unknown |

| lpg0030 | lpp0030 | lpl0031 | lpc0031 | lpa0040 | lpw00311 | – | – | − | − | − | ravB | Unknown |

| lpg0038 | lpp0037 | lpl0038 | lpc0039 | lpa0049 | lpw00381 | – | – | − | − | − | ankQ/legA10 | Ankyrin repeat |

| lpg0041 | – | – | lpc0042 | lpa0056 | – | – | – | − | − | − | – | Putative metalloprotease |

| lpg0045 | lpp0046 | lpl0044 | lpc0047 | lpa0060 | lpw00441 | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg0046 | lpp0047 | lpl0045 | lpc0048 | lpa0062 | lpw00451 | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg0059 | lpp0062 | lpl0061 | lpc0068 | lpa0085 | lpw00621 | – | – | − | − | − | ceg2 | Unknown |

| lpg0080 | lpp0094 | – | – | lpa3018 | lpw00781 | – | – | − | − | − | ceg3 | Unknown |

| lpg0081 | lpp0095 | – | – | – | lpw00791 | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg0090 | lpp0104 | lpl0089 | lpc0109 | lpa0132 | lpw00881 | – | – | − | − | − | lem1 | Unknown |

| lpg0096 | lpp0110 | lpl0096 | lpc0115 | lpa0145 | lpw00961 | llo1322 | llb0347 | + | + | + | ceg4 | Unknown |

| lpg0103 | lpp0117 | lpl0103 | lpc0122 | lpa0152 | lpw01031 | llo3312 | llb2028 | + | + | + | vipF | N-terminal acetyl-transferase, GNAT |

| lpg0126 | lpp0140 | lpl0125 | lpc0146 | lpa0185 | lpw01261 | – | – | − | − | − | cegC2 | Ninein |

| lpg0130 | lpp0145 | lpl0130 | lpc0151 | lpa0194 | lpw01311 | llo3270 | llb2073 | + | + | + | – | Unknown |

| lpg0135 | lpp0150 | lpl0135 | lpc0156 | lpa0204 | lpw01361 | llo2439 | llb2921 | + | + | + | sdhB | Unknown |

| lpg0160 | lpp0224 | lpl0224 | lpc0242 | lpa0322 | lpw02541 | – | – | − | − | − | ravD | Unknown |

| lpg0170 | lpp0232 | lpl0233 | lpc0251 | lpa0335 | lpw02641 | llo1378 | llb0280 | + | + | + | ravC | Unknown |

| lpg0171 | lpp0233 | lpl0234 | – | – | lpw02651 | – | – | − | − | − | legU1 | F-box motif |

| lpg0172 | lpp0234 | – | lpc0253 | lpa0339 | lpw02661 | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg0181 | lpp0245 | lpl0244 | lpc0265 | lpa0388 | lpw02761 | llo2453 | llb2907 | + | + | + | – | Unknown |

| lpg0191 | lpp0251 | – | – | – | lpw02821 | – | – | − | − | − | ceg5 | Unknown |

| lpg0195 | lpp0253 | lpl0251 | lpc0272 | lpa0339 | lpw02851 | – | – | − | − | − | ravE | Unknown |

| lpg0196 | lpp0254 | lpl0252 | – | – | lpw02861 | llo2549 | llb2798 | + | + | + | ravF | Unknown |

| lpg0210 | lpp0269 | lpl0264 | lpc0285 | lpa0388 | lpw02981 | – | – | − | − | − | ravG | Unknown |

| lpg0227 | lpp0286 | lpl0281 | lpc0303 | lpa0412 | lpw03151 | llo2491 | llb2864 | + | + | + | ceg7 | Unknown |

| lpg0234 | lpp0304 | lpl0288 | lpc0309 | lpa0419 | lpw03221 | llo0425 | llb1431 | + | + | + | sidE/laiD | Unknown |

| lpg0240 | lpp0310 | lpl0294 | lpc0316 | lpa0428 | lpw03291 | llo1601 | llb0040 | + | + | + | ceg8 | Unknown |

| lpg0246 | lpp0316 | lpl0300 | lpc0323 | lpa0436 | lpw03361 | – | – | − | − | − | ceg9 | Unknown |

| lpg0257 | lpp0327 | lpl0310 | lpc0334 | lpa0450 | lpw03461 | llo2362 | llb3009 | + | + | + | sdeA | Multidrug resistance protein |

| lpg0260 | lpp0332 | lpl0313 | lpc0337 | lpa0456 | lpw03491 | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg0275 | lpp0349 | lpl0327 | lpc0351/3529 | lpa0477 | lpw03641 | – | – | − | − | − | sdbA | Unknown |

| lpg0276 | lpp0350 | lpl0328 | lpc0353 | lpa0479 | lpw03651 | llo0327 | llb1533 | + | + | + | legG2 | Ras guanine nucleotide exchange factor |

| lpg0284 | lpp0360 | lpl0336 | lpc0361 | lpa0490 | lpw03741 | – | – | − | − | − | ceg10 | Unknown |

| lpg0285 | lpp0361 | lpl0337 | lpc0362 | lpa0492 | lpw03751 | – | – | − | − | − | lem2 | Unknown |

| lpg0294 | lpp0372 | lpl0347 | lpc0373 | lpa0508 | lpw03861 | llo0464 | llb1386 | + | + | + | – | Unknown |

| lpg0364 | lpp0429 | lpl0405 | lpc2980 | lpa0578 | lpw04431 | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg0365 | lpp0430 | lpl0406 | lpc2979 | lpa0580 | lpw04441 | llo0525 | llb1334 | + | + | + | – | Unknown |

| lpg0375 | lpp0442 | lpl0418 | lpc2968 | lpa0596 | – | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg0376 | lpp0443 | lpl0419 | lpc2967 | lpa0597 | lpw04591 | llo0548 | llb1307 | + | + | + | sdhA | GRIP, coiled-coil |

| lpg0390 | lpp0457 | lpl0433 | lpc2954 | lpa0613 | lpw04721 | – | – | − | − | − | vipA | Unknown |

| lpg0401 | lpp0468 | lpl0444 | lpc2942 | lpa0629 | lpw04831 | llo2582 | llb2763 | + | + | + | legA7/ceg11 | Unknown |

| lpg0402 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | − | − | − | ankY/legA9 | Ankyrin, STPK |

| lpg0403 | lpp0469 | lpl0445 | lpc2941 | lpa0630 | lpw04841 | – | – | − | − | − | ankG/ankZ/legA7 | Ankyrin |

| lpg0405 | lpp0471 | lpl0447 | lpc2939 | lpa0633 | lpw04861 | llo2845 | llb2472 | + | + | + | – | Spectrin domain |

| lpg0422 | lpp0489 | lpl0465 | lpc2921 | lpa0657 | lpw05041 | llo2801 | llb2523 | + | + | + | legY | Putative Glucan 1,4-alpha-glucosidase |

| lpg0436 | lpp0503 | lpl0479 | lpc2906 | lpa0673 | lpw05181 | – | – | − | − | − | ankJ/legA11 | Ankyrin |

| lpg0437 | lpp0504 | lpl0480 | lpc2905 | lpa0674 | lpw05191 | – | – | − | − | − | ceg14 | Unknown |

| lpg0439 | lpp0505 | lpl0481 | lpc2904 | lpa0678 | lpw05201 | llo2983 | llb2392 | + | + | + | ceg15 | Unknown |

| lpg0483 | lpp0547 | lpl0523 | lpc2861 | lpa0739 | lpw05631 | llo2705 | llb2623 | + | + | + | ankC/legA12 | Ankyrin |

| lpg0515 | lpp0578 | lpl0554 | lpc2829 | lpa0776 | lpw05951 | llo3224 | llb2129 | + | + | + | legD2 | Phytanoyl-CoA dioxygenase domain |

| lpg0518 | lpp0581 | lpl0557 | lpc2826 | lpa0781 | lpw05981 | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg0519 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | − | − | − | ceg17 | Unknown |

| lpg0621 | lpp0675 | lpl0658 | lpc2673 | lpa0975 | lpw06951 | – | – | − | − | − | sidA | Unknown |

| lpg0634 | lpp0688 | lpl0671 | lpc2660 | lpa0996 | lpw07081 | llo2574 | llb2771 | + | + | + | – | Unknown |

| lpg0642 | lpp0696/97 | lpl0679 | lpc2651 | lpa1005 | lpw07161 | – | – | − | − | − | wipB | Unknown |

| lpg0695 | lpp0750 | lpl0732 | lpc2599 | lpa1082 | lpw07721 | – | – | − | − | − | ankN/ankX legA8 | Ankyrin |

| lpg0696 | lpp0751 | lpl0733 | lpc2598 | lpa1084 | lpw07731 | – | – | − | − | − | lem3 | Unknown |

| lpg0716 | lpp0782 | lpl0753 | lpc2577 | lpa1108 | lpw07931 | – | – | − | + | + | – | Unknown |

| lpg0733 | lpp0799 | lpl0770 | lpc2559 | lpa1135 | lpw08111 | llo0831 | llb0892 | + | + | + | ravH | Unknown |

| lpg0796 | lpp0859 | – | – | – | – | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg0898 | lpp0959 | lpl0929 | lpc2395 | lpa1360 | lpw09801 | – | – | − | − | − | ceg18 | Unknown |

| lpg0926 | lpp0988 | lpl0957 | lpc2365 | lpa1397 | lpw10111 | – | – | − | − | − | ravI | Unknown |

| lpg0940 | lpp1002 | lpl0971 | lpc2349 | lpa1415 | lpw10251 | – | – | − | − | − | lidA | Unknown |

| lpg0944 | lpp1006 | – | lpc2345 | lpa1421 | – | – | – | − | − | − | ravJ | Unknown |

| lpg0945 | lpp1007 | lpl1579 | lpc2344 | lpa1423 | lpw10311 | – | – | − | − | − | legL1 | LLR |

| lpg0963 | lpp1025 | lpl0992 | lpc2324 | lpa1453 | lpw10491 | llo0934 | llb0782 | + | + | + | – | Unknown |

| lpg0967 | lpp1029 | – | lpc2320 | lpa1459 | lpw10531 | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg0968 | lpp1030 | lpl0997 | lpc2319 | lpa1460 | lpw10541 | – | – | − | − | − | sidK | Unknown |

| lpg0969 | lpp1031 | lpl0998 | lpc2318 | lpa1461 | lpw10551 | llo3265 | llb2078 | + | + | + | ravK | Unknown |

| lpg1083 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg1101 | lpp1101 | lpl1100 | lpc2154* | lpa1709 | lpw11451 | – | – | − | − | − | lem4 | Unknown |

| lpg1106 | lpp1105 | lpl1105 | lpc2149 | lpa1719 | lpw11501 | llo1414 | llb0239/40 | + | + | + | – | Unknown |

| lpg1108 | lpp1108 | lpl1108 | lpc2146 | lpa1724 | lpw11531 | llo3030 | llb2350 | + | + | + | ravL | Unknown |

| lpg1109 | lpp1109 | – | lpc2145 | lpa1725 | – | – | – | − | − | − | ravM | Unknown |

| lpg1110 | lpp1111 | lpl1114 | lpc2142 | lpa1728 | lpw11571 | – | – | − | − | − | lem5 | Unknown |

| lpg1111 | lpp1112 | lpl1115 | lpc2141 | lpa1730 | lpw11581 | llo3126 | llb2244 | + | + | + | ravN | Unknown |

| lpg1120 | – | – | – | – | lpw11681 | – | – | − | − | − | lem6 | Unknown |

| lpg1121 | lpp1121 | lpl1126 | lpc0578 | lpa1743 | lpw11691 | llo1321 | llb0348 | + | + | + | ceg19 | Unknown |

| lpg1124 | lpp1125 | lpl1129 | lpc0582 | lpa1748 | lpw11741 | llo3206 | llb2150 | + | + | + | – | Unknown |

| lpg1129 | lpp1130 | – | – | – | lpw11801 | – | – | − | − | − | ravO | Unknown |

| lpg1137 | lpp1139 | lpl1144 | lpc0601 | lpa1776 | lpw11901 | llo2404 | llb2962 | + | + | + | – | Unknown |

| lpg1144 | lpp1146 | lpl1150 | lpc0607 | lpa1785 | lpw11971 | – | – | − | − | − | cegC3 | Unknown |

| lpg1145 | lpp1147 | lpl1151 | lpc0608 | lpa1787 | lpw11981 | – | – | − | − | − | lem7 | Unknown |

| lpg1147 | lpp1149 | lpl1153 | lpc0610 | lpa1789 | lpw12001 | – | – | − | − | − | – | GCN5-related N-acetyltransferase |

| lpg1148 | lpp1150 | lpl1154 | lpc0611 | lpa1790 | lpw12011 | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg1152 | lpp1154 | lpl1159 | lpc0615 | lpa1795 | lpw12061 | – | – | − | − | − | ravP | Unknown |

| lpg1154 | lpp1156 | lpl1161 | lpc0617 | lpa1797 | lpw12081 | llo2487 | llb2868 | + | + | + | ravQ | Unknown |

| lpg1158 | lpp1160 | lpl1165* | lpc0621 | lpa1802 | lpw12121 | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg1166 | lpp1168 | lpl1174 | lpc0631 | lpa1819 | lpw12211 | llo1034 | llb0680 | + | + | + | ravR | Unknown |

| lpg1171 | lpp1173 | lpl1179 | lpc0637 | lpa1826 | – | – | – | − | − | − | – | Spectrin domain |

| lpg1183 | lpp1186 | lpl1192 | lpc0650 | lpa1839 | lpw12401 | llo2390 | llb2978 | + | + | + | ravS | Unknown |

| lpg1227 | lpp1235 | lpl1235 | lpc0696 | lpa1899 | lpw12861 | – | – | − | − | − | vpdB | Unknown |

| lpg1273 | lpp1236 | lpl1236 | lpc0698 | lpa1901 | lpw12871 | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg1290 | lpp1253 | – | – | – | – | – | – | − | − | − | lem8 | Unknown |

| lpg1312 | – | – | – | – | lpw13261 | – | – | − | − | − | legC1 | Unknown |

| lpg1316 | – | – | – | – | – | llo1389 | llb0269 | + | + | + | ravT | Unknown |

| lpg1317 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | − | − | − | ravW | Unknown |

| lpg1328 | lpp1283 | lpl1282 | lpc0743 | lpa1958 | – | – | – | − | − | − | legT | Thaumatin domain |

| lpg1355 | lpp1309 | – | – | – | – | – | – | − | − | − | sidG | Coiled-coil |

| lpg1426 | lpp1381 | lpl1377 | lpc0842 | lpa2090 | lpw14431 | llo1791 | llb3606 | + | + | + | vpdC | Patatin domain |

| lpg1449 | lpp1404 | – | – | – | lpw14671 | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg1453 | lpp1409 | lpl1591 | lpc0868 | lpa2119 | lpw14711 | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg1483 | lpp1439 | lpl1545 | lpc0898 | lpa2161 | lpw15031 | llo1682 | llb3727 | + | + | + | legK1 | STPK |

| lpg1484 | lpp1440 | lpl1544 | lpc0899 | lpa2162 | lpw15041 | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg1488 | lpp1444 | lpl1540 | lpc0903* | lpa2168 | lpw15081 | – | – | − | − | − | lgt3/legc5 | Coiled-coil |

| lpg1489 | lpp1445 | lpl1539 | lpc0905 | lpa2169 | lpw15091 | – | – | − | − | − | ravX | Unknown |

| lpg1491 | lpp1447 | – | – | – | – | – | – | − | − | − | lem9 | Unknown |

| lpg1496 | lpp1453 | lpl1530 | lpc0915 | lpa2185 | lpw15181 | – | – | − | − | − | lem10 | Unknown |

| lpg1551 | lpp1508 | lpl1475 | lpc0972 | lpa2253 | – | – | – | − | − | − | ravY | Unknown |

| lpg1578 | lpp4178 | lpl4143 | lpc1002 | lpa2292 | lpw16011 | llo1503 | llb0148 | + | + | + | – | Unknown |

| lpg1588 | lpp1546 | lpl1437 | lpc1013 | lpa2305 | lpw16131 | – | – | − | − | − | legC6 | Coiled–coil |

| lpg1598 | lpp1556 | lpl1427 | lpc1025 | lpa2317 | lpw16231 | – | – | − | − | − | lem11 | Unknown |

| lpg1602 | lpp1567 | lpl1423/26* | lpc1028 | lpa2318 | lpw16241 | – | – | − | − | − | legL2 | LRR |

| lpg1621 | lpp1591 | lpl1402 | lpc1048 | lpa2346 | lpw16461 | llo1014 | llb0702 | + | + | + | ceg23 | Unknown |

| lpg1625 | lpp1595 | lpl1398 | lpc1052 | lpa2350 | lpw16511 | llo0719 | llb1016 | + | + | + | lem23 | Unknown |

| lpg1639 | lpp1609 | lpl1387 | lpc1068 | lpa2367 | lpw16651 | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg1642 | lpp1612a/b | lpl1384 | lpc1071 | lpa2371 | lpw16681 | – | – | − | − | − | sidB | Putative hydrolase |

| lpg1654 | lpp1625 | – | lpc1084 | lpa2390 | – | llo0791 | llb0935 | + | + | + | – | Unknown |

| lpg1660 | lpp1631 | lpl1625 | lpc1090 | lpa2398 | lpw16861 | – | – | − | − | − | legL3 | LRR |

| lpg1661 | lpp1632 | lpl1626 | lpc1091 | lpa2399 | lpw16871 | llo1691 | llb3715 | + | + | + | – | Putative N-acetyl transferase |

| lpg1666 | lpp1637 | lpl1631 | lpc1096 | lpa2408 | lpw16921 | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg1667 | lpp1638 | lpl1632 | lpc1097 | lpa2409 | lpw16931 | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg1670 | lpp1642 | lpl1635 | lpc1101 | lpa2413 | lpw16971 | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg1683 | – | – | lpc1114 | lpa2431 | – | llo2508 | llb2843 | + | + | + | ravZ | Unknown |

| lpg1684 | – | – | lpc1115 | lpa2432 | – | llo2267 | llb3113 | + | + | + | – | Unknown |

| lpg1685 | – | – | lpc1116 | lpa2433 | – | llo3208 | llb2147 | + | + | + | – | Unknown |

| lpg1687 | lpp1656 | lpl1650 | lpc1118 | lpa2437 | lpw17121 | – | – | − | − | − | mavA | Unknown |

| lpg1689 | lpp1658 | lpl1652 | lpc1120 | lpa2439 | lpw17141 | llo1697 | llb3708 | + | + | + | – | Unknown |

| lpg1692 | – | – | lpc1123 | lpa2442 | – | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg1701 | lpp1666 | lpl1660 | lpc1130 | lpa2455 | lpw17231 | – | – | − | − | − | ppeA/legC3 | Coiled-coil |

| lpg1702 | lpp1667 | lpl1661 | lpc1131 | lpa2456 | lpw17241 | – | – | − | − | − | ppeB | Unknown |

| lpg1716 | lpp1681 | lpl1675 | lpc1146 | lpa2474 | lpw17391 | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg1717 | lpp1682 | – | – | – | lpw17401 | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg1718 | lpp1683 | lpl1682 | lpc1152 | lpa2484 | lpw17411 | – | – | − | − | − | ankI/legAS4 | Ankyrin |

| lpg1751 | lpp1715 | lpl1715 | lpc1191 | lpa2538 | lpw17761 | llo2314 | llb3061 | + | + | + | – | Unknown |

| lpg1752 | lpp1716 | lpl1716 | lpc1192 | lpa2539 | lpw17771 | llo2315 | llb3060 | + | + | + | – | Unknown |

| lpg1776 | lpp1740 | lpl1740 | lpc1217 | lpa2570 | lpw18031 | llo1437 | llb0214* | + | + | + | – | Unknown |

| lpg1797 | – | – | lpc1239 | lpa2599 | lpw32931 | – | – | − | − | − | rvfA | Unknown |

| lpg1798 | lpp1761 | lpl1761 | lpc1241 | lpa2600 | lpw18281 | llo0991 | llb0731 | + | + | + | marB | Unknown |

| lpg1803 | lpp1766 | lpl1766 | lpc1246 | lpa2606 | lpw18331 | llo2611 | llb2729 | + | + | + | – | Unknown |

| lpg1836 | lpp1799 | lpl1800 | lpc1280 | lpa2652 | lpw18691 | – | – | − | − | − | ceg25 | Unknown |

| lpg1851 | lpp1818 | lpl1817 | lpc1296 | lpa2675 | lpw18871 | llo1047 | llb0666 | + | + | + | lem14 | Unknown |

| lpg1884 | lpp1848 | lpl1845 | lpc1331 | lpa2714 | lpw19161 | – | – | − | − | − | ylfB/legC2 | Coiled-coil |

| lpg1888 | lpp1855 | lpl1850 | lpc1336 | lpa2723 | lpw19211 | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg1890 | – | lpl1852 | lpc1338 | lpa2726 | lpw19231 | – | – | − | − | − | legLC8 | LRR, coiled-coil |

| lpg1907 | lpp1882 | lpl1871 | lpc1361 | lpa2762 | lpw19461 | llo1240 | llb0452 | + | + | + | – | Unknown |

| lpg1924 | lpp1899 | lpl1888 | lpc1378 | lpa2783 | lpw19631 | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg1933 | lpp1914 | lpl1903 | lpc1406 | lpa2811 | lpw19721 | – | – | − | − | − | lem15 | Unknown |

| lpg1947 | lpp1930 | lpl1917* | – | lpa2835 | lpw19951 | – | – | − | − | − | lem16 | Spectrin domain |

| lpg1948 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | − | − | − | legLC4 | LRR, coiled-coil |

| lpg1949 | lpp1931 | lpl1918 | lpc1422 | lpa2837 | lpw19961 | – | – | − | − | − | lem17 | Unknown |

| lpg1950 | lpp1932 | lpl1919 | lpc1423 | lpa2838 | lpw19971 | llo1397 | llb0259 | + | + | + | ralF | Sec7 domain |

| lpg1953 | lpp1935 | lpl1922 | lpc1426 | lpa2842 | lpw20041 | – | – | − | − | − | legC4 | Coiled-coil |

| lpg1958 | lpp1940 | – | – | – | – | – | – | − | − | − | legL5 | LRR |

| lpg1959 | lpp1941 | – | – | lpa2857 | lpw20101 | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg1960 | lpp1942 | lpl1934* | lpc1437 | lpa2859 | lpw20111 | llo0565 | llb1288 | + | + | + | lirA | Unknown |

| lpg1962 | lpp1946 | lpl1936 | lpc1440 | lpa2861 | lpw20131 | – | – | − | − | − | lirB | Rotamase |

| lpg1963 | – | – | lpc1441/42 | lpa2863 | – | – | – | − | − | − | pieA/lirC | Unknown |

| lpg1964 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | − | − | − | pieB/lirD | Unknown |

| lpg1965 | – | – | lpc1443/45 | lpa2865 | lpw20141 | – | – | − | − | − | pieC/lirE | Unknown |

| lpg1966 | lpp1947 | – | lpc1446 | lpa2867 | lpw20151 | – | – | − | − | − | pieD/lirF | Unknown |

| lpg1969 | lpp1952 | lpl1941 | lpc1452 | lpa2874 | lpw20201 | llo3131 | llb2239 | + | + | + | pieE | Unknown |

| lpg1972 | lpp1955 | lpl1950 | lpc1459 | lpa2884 | lpw20291 | – | – | − | − | − | pieF | Unknown |

| lpg1975 | lpp1959 | lpl1953 | lpc1462 | lpa2889(1) | lpw20351 | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg1976 | lpp1959 | lpl1953 | lpc1462 | lpa2889(2) | lpw20351 | – | – | − | − | − | pieG/legG1 | Regulator of chromosome condensation |

| lpg1978 | lpp1961 | lpl1955 | lpc1464 | lpa2892 | lpw20371 | – | – | − | − | − | setA | Putative Glyosyltransferase |

| lpg1986 | lpp1967 | lpl1961 | lpc1469 | lpa2898 | lpw20431 | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg2050 | lpp2033 | lpl2028 | lpc1536 | lpa2992 | lpw21141 | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg2131 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | − | − | − | legA6 | Unknown |

| lpg2137 | lpp2076 | lpl2066 | lpc1586 | lpa3060 | lpw23101 | – | – | − | − | − | legK2 | STPK |

| lpg2144 | lpp2082 | lpl2072 | lpc1593 | lpa3071 | lpw23181 | – | – | − | − | − | ankB/legAU13/ceg27 | Ankyrin, F-box |

| lpg2147 | lpp2086 | lpl2075 | lpc1596 | lpa3076 | lpw23211 | – | – | − | − | − | mavC | Unknown |

| lpg2148 | lpp2087 | lpl2076 | lpc1597 | lpa3077 | lpw23221 | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg2149 | lpp2088 | lpl2077 | lpc1598 | lpa3078 | lpw23231 | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg2153 | lpp2092 | lpl2081 | lpc1602 | lpa3083 | lpw23271 | – | – | − | − | − | sdeC | Unknown |

| lpg2154 | lpp2093 | lpl2082 | lpc1603 | lpa3086 | lpw23281 | llo3097 | llb2278 | + | + | + | sdeC | Unknown |

| lpg2155 | lpp2094 | lpl2083 | lpc1604 | lpa3087 | lpw23291 | llo3096 | llb2279 | + | + | + | sidJ | Unknown |

| lpg2156 | lpp2095 | lpl2084 | lpc1605 | lpa3088 | lpw23301 | llo3095 | llb2280 | + | + | +? | sdeB | Unknown |

| lpg2157 | lpp2096 | lpl2085 | lpc1618 | lpa3037 | lpw23331 | – | – | − | − | − | sdeC | Unknown |

| lpg2166 | lpp2104 | lpl2093 | lpc1626 | lpa3107 | lpw23451 | llo2398 | llb2969 | + | + | + | lem19 | Unknown |

| lpg2160 | lpp2099 | lpl2088 | lpc1621 | lpa3100 | lpw23361 | llo2645 | llb2690 | + | + | + | – | Unknown |

| lpg2176 | lpp2128 | lpl2102 | lpc1635 | lpa3118 | lpw23561 | – | – | – | – | – | legS2 | Sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase |

| lpg2199 | lpp2149 | lpl2123 | lpc1663 | lpa3157 | lpw23811 | – | – | – | – | – | cegC4 | Unknown |

| lpg2200 | lpp2150 | lpl2124 | lpc1664 | lpa3158 | lpw23821 | – | – | – | – | – | cegC4 | Unknown |

| lpg2215 | lpp2166 | lpl2140 | lpc1680 | lpa3179 | lpw24011 | – | – | – | – | – | legA2 | Ankyrin |

| lpg2216 | lpp2167 | lpl2141 | lpc1681 | lpa3180 | lpw24021 | – | – | – | – | – | lem20 | Unknown |

| lpg2222 | lpp2174 | lpl2147 | lpc1689 | lpa3191 | lpw24081 | llo1443 | llb0208 | + | + | + | lpnE | Putative beta-lactamase (SEL1 domain) |

| lpg2223 | lpp2175 | lpl2149* | lpc1691 | lpa3196 | lpw24091 | – | – | – | – | – | – | Unknown |

| lpg2224 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ppgA | Regulator of chromosome condensation |

| lpg2239 | lpp2192 | – | – | – | lpw24261 | – | – | – | – | – | – | Unknown |

| lpg2248 | lpp2202 | lpl2174 | lpc1717 | lpa3237 | lpw24371 | – | – | – | – | – | lem21 | Unknown |

| lpg2271 | lpp2225 | lpl2197 | lpc1740 | lpa3268 | lpw24611 | llo2530 | llb2821 | + | + | + | – | Unknown |

| lpg2298 | lpp2246 | lpl2217 | lpc1763 | lpa3296 | lpw24841 | llo1707 | llb3696 | + | + | + | ylfA/legC7 | Coiled-coil |

| lpg2300 | lpp2248 | lpl2219 | lpc1765 | lpa3298 | lpw24871 | llo0584 | llb1266 | + | + | + | ankH/legA3, ankW | Ankyrin, NfkappaB inhibitor |

| lpg2311 | lpp2259 | lpl2230 | lpc1776 | lpa3312 | lpw24981 | – | – | − | − | − | ceg28 | Unknown |

| lpg2322 | lpp2270 | lpl2242 | lpc1789 | lpa3328 | lpw25121 | llo0570 | llb1282 | + | + | + | ankK/legA5 | Ankyrin |

| lpg2327 | lpp2275 | lpl2247 | lpc1794 | lpa3335 | lpw25181 | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg2328 | lpp2276 | lpl2248 | lpc1795 | lpa3336 | lpw25191 | – | – | − | − | − | lem22 | Unknown |

| lpg2344 | lpp2292 | lpl2265 | lpc1812 | lpa3355 | lpw25371 | – | – | − | − | − | mavE | Unknown |

| lpg2351 | lpp2300 | lpl2273 | lpc1820 | lpa3367 | lpw25461 | llo2850 | llb2466 | + | + | + | mavF | Unknown |

| lpg2359 | lpp2308 | lpl2281 | lpc1828 | lpa3376 | lpw25561 | llo2856 | llb2460 | + | + | + | – | Unknown |

| lpg2370 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | − | − | − | – | HipA fragment |

| lpg2372 | lpp3009 | – | lpc3248 | lpa4300 | – | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg2382 | lpp2444 | lpl2300 | lpc2108 | lpa3446 | lpw25841 | llo1576 | llb0071 | + | + | + | – | Unknown |

| lpg2391 | lpp2458 | lpl2315 | lpc2086 | lpa3485 | lpw26021 | – | – | − | − | − | sdbC | Unknown |

| lpg2392 | lpp2459 | lpl2316 | lpc2085 | lpa3486 | lpw26041 | – | – | − | − | − | legL6 | LRR |

| lpg2400 | – | lpl2323 | – | – | lpw26121 | – | – | − | − | − | legL6 | LRR |

| lpg2406 | lpp2472 | lpl2329 | lpc2070 | lpa3506 | lpw26191 | llo2172 | llb3225 | + | + | + | lem23 | Unknown |

| lpg2407 | lpp2474 | – | lpc2069 | lpa3507 | – | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg2409 | lpp2476 | lpl2332 | lpc2067 | lpa3511 | lpw26241 | – | – | − | − | − | ceg29 | Unknown |

| lpg2410 | lpp2479 | lpl2334 | lpc2065 | lpa3513 | lpw26261 | – | – | − | − | − | vpdA | Patatin domain |

| lpg2411 | lpp2480 | lpl2335 | lpc2064 | lpa3515 | lpw26281 | llo2227 | llb3158 | + | + | + | lem24 | Unknown |

| – | lpp2486 | – | – | – | – | − | − | – | F-box | |||

| lpg2416 | – | lpl2339 | lpc2057 | lpa3527 | lpw26351 | – | – | − | − | − | legA1 | Unknown |

| lpg2420 | – | lpl2343 | lpc2056 | lpa3529 | lpw26391 | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg2422 | lpp2487 | lpl2345 | lpc2055 | lpa3530 | lpw26401 | llo1650 | llb3763/64 | + | + | + | lem25 | Unknown |

| lpg2424 | lpp2489 | lpl2347 | lpc2053 | lpa3532 | lpw26421 | – | – | − | − | − | mavG | Unknown |

| lpg2425 | lpp2491 | lpl2348 | lpc2051 | lpa3537 | lpw26431 | – | – | − | − | − | mavH | Unknown |

| lpg2433 | lpp2500 | lpl2353 | lpc2043 | lpa3548 | lpw26521 | – | – | − | − | − | ceg30 | Unknown |

| lpg2434 | lpp2501 | lpl2355 | lpc2042 | lpa3550 | lpw26531 | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg2443 | lpp2510 | lpl2363 | lpc2033 | lpa3562 | – | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg2444 | lpp2511 | lpl2364 | lpc2032 | lpa3563 | lpw26641 | – | – | − | − | − | mavI | Unknown |

| lpg2452 | lpp2517 | lpl2370 | lpc2026 | lpa3574 | lpw26701 | – | – | − | − | − | ankF/legA14/ceg31 | Ankyrin |

| lpg2456 | lpp2522 | lpl2375 | lpc2020 | lpa3583 | lpw26751 | llo0365 | llb1493 | + | + | + | ankD/legA15 | Ankyrin |

| lpg2461 | lpp2527 | lpl2380 | lpc2015 | lpa3589 | lpw26801 | llo1991 | llb3433 | + | + | + | – | Unknown |

| lpg2464 | – | lpl2384 | – | – | lpw26851 | – | – | − | − | − | sidM/drrA | Unknown |

| lpg2465 | – | lpl2385 | – | – | lpw26861 | – | – | − | − | − | sidD | Unknown |

| lpg2490 | lpp2555 | lpl2411 | lpc1987 | lpa3628 | lpw27131 | – | – | − | − | − | lepB | Coiled-coil, Rab1 GAP |

| lpg2482 | lpp2546 | lpl2402 | lpc1996 | lpa3615 | lpw27041 | – | – | − | − | − | sdbB | Unknown |

| lpg2498 | lpp2566 | lpl2420 | lpc1975 | lpa3646 | lpw27241 | – | – | − | − | − | mavJ | Unknown |

| lpg2504 | lpp2572 | lpl2426 | lpc1967 | lpa3658 | lpw27301 | llo2525 | llb2826 | + | + | + | sidI/ceg32 | Unknown |

| lpg2505 | lpp2573 | lpl2427 | lpc1966 | lpa3659 | lpw27311 | llo2526 | llb2825 | + | + | + | – | Unknown |

| lpg2508 | lpp2576 | lpl2430 | lpc1962/63* | lpa3666 | lpw27341 | – | – | − | − | − | sdjA | Unknown |

| lpg2509 | lpp2577 | lpl2431 | lpc1961 | lpa3667 | lpw27351 | llo3097 | llb2278 | + | + | + | sdeD | Unknown |

| lpg2510 | lpp2578 | lpl2432 | lpc1960 | lpa3668 | – | llo3098 | llb2276 | + | + | + | sdcA | Unknown |

| lpg2511 | lpp2579 | lpl2433 | lpc1959 | lpa3669 | lpw27371 | – | – | − | − | − | sidC | PI(4)P binding domain |

| lpg2523 | – | – | – | – | lpw27501 | – | – | − | − | − | lem26 | Unknown |

| lpg2525 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | − | − | − | mavK | Unknown |

| lpg2526 | lpp2591 | lpl2446 | lpc1946 | lpa3687 | lpw27521 | – | – | − | − | − | mavL | Unknown |

| lpg2527 | lpp2592 | lpl2447 | lpc1944 | lpa3688 | lpw27531 | llo3335 | llb2002 | + | + | + | – | Unknown |

| lpg2529 | lpp2594 | lpl2449 | lpc1942 | lpa3692 | lpw27551 | llo2238 | llb3146 | + | + | + | lem27 | Unknown |

| lpg2538 | lpp2604 | lpl2459 | lpc1930 | lpa3706 | lpw27671 | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg2539 | lpp2605 | lpl2460 | lpc1929 | lpa3707 | lpw27681 | llo1348 | llb0317 | + | + | + | – | Unknown |

| lpg2541 | lpp2607 | lpl2462 | lpc1927 | lpa3710 | lpw27701 | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg2546 | lpp2615 | – | lpc1919 | lpa3727 | lpw27791 | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg2552 | lpp2622 | lpl2473 | lpc1911 | lpa3738 | lpw27871 | llo1062 | llb0648 | + | + | + | – | Unknown |

| lpg2555 | lpp2625 | lpl2480 | lpc1908 | lpa3743 | lpw27901 | llo2220 | llb3170 | + | + | + | – | Unknown |

| lpg2556 | lpp2626 | lpl2481 | lpc1906 | lpa3745 | lpw27911 | llo2218 | llb3172 | + | + | + | legK3 | STPK |

| lpg2577 | lpp2629 | lpl2499 | lpc0570 | lpa3768 | lpw28241 | – | – | − | − | − | mavM | Unknown |

| lpg2584 | lpp2637 | lpl2507 | lpc0561 | lpa3779 | lpw28321 | – | – | − | − | − | sidF | Unknown |

| lpg2588 | lpp2641 | lpl2511 | lpc0557 | lpa3784 | lpw28361 | llo2622 | llb2718 | + | + | + | legS1 | Unknown |

| lpg2591 | lpp2644 | lpl2514 | lpc0551 | lpa3790 | lpw28391 | llo0626 | llb1219 | + | + | + | ceg33 | Unknown |

| lpg2603 | lpp2656 | lpl2526 | lpc0539 | lpa3807 | lpw28521 | – | – | − | − | − | lem28 | Unknown |

| lpg2628 | lpp2681 | lpl2553 | lpc0513 | lpa3846 | lpw28781 | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg2637 | lpp2690 | lpl2562 | lpc0503 | lpa3859 | lpw28871 | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg2638 | lpp2691 | lpl2563 | lpc0502 | lpa3861 | lpw28891 | llo2645 | llb2690 | + | + | + | mavV | Unknown |

| lpg2692 | lpp2746 | lpl2619 | lpc0444 | lpa3929 | lpw29461 | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg2694 | lpp2748 | lpl2621 | lpc0442 | lpa3931 | lpw29481 | – | – | − | − | − | legD1 | Phyhd1 protein |

| lpg2718 | lpp2775 | lpl2646 | lpc0415 | lpa3966 | lpw29771 | – | – | − | − | − | wipA | Unknown |

| lpg2720 | lpp2777 | lpl2648 | lpc0413 | lpa3968 | lpw29791 | – | – | − | − | − | legN | cAMP-binding protein |

| lpg2744 | lpp2800 | lpl2669 | lpc0386 | lpa4004 | lpw30031 | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg2745 | lpp2801 | lpl2670 | lpc0385 | lpa4005 | lpw30041 | llo0308 | llb1553 | + | + | + | – | Unknown |

| lpg2793 | lpp2839 | lpl2708 | lpc3079 | lpa4063 | lpw30471 | – | – | − | − | − | lepA | Effector protein A |

| lpg2804 | lpp2850 | lpl2719 | lpc3090 | lpa4076 | lpw30591 | llo0267 | llb1598 | + | + | + | lem29 | Unknown |

| lpg2815 | lpp2867 | lpl2730 | lpc3101 | lpa4089 | lpw30711 | llo0254 | llb1612 | + | + | + | mavN | Unknown |

| lpg2826 | – | lpl2741 | lpc3113 | lpa4104 | lpw30831 | – | – | − | − | − | ceg34 | Unknown |

| lpg2828 | lpp2882 | lpl2743 | lpc3115 | lpa4109 | lpw30851 | llo0783 | llb0944 | + | + | + | – | Unknown |

| lpg2829 | lpp2883/86* | – | – | – | lpw30861 | – | – | − | − | − | sidH | Unknown |

| lpg2830 | lpp2887 | – | – | – | lpw30881 | – | – | − | − | − | lubX/legU2 | U-box motif |

| lpg2831 | lpp2888 | – | – | – | lpw30891 | – | – | − | − | − | VipD | Patatin-like phopholipase |

| lpg2832 | lpp2889 | lpl2744 | lpc3116 | lpa4110 | lpw30921 | llo0214 | llb1656 | + | + | + | – | Putative hydrolase |

| lpg2844 | lpp2903 | lpl2756 | lpc3128 | lpa4133 | – | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg2862 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | − | − | − | Lgt2/legC8 | Coiled-coil |

| lpg2874 | lpp2933 | lpl2787 | lpc3160 | lpa4176 | lpw31411 | – | – | – | – | – | – | Unknown |

| lpg2879 | lpp2938 | lpl2792 | lpc3165 | lpa4186 | lpw31471 | llo0192 | llb1681 | + | + | + | – | Unknown |

| lpg2884 | lpp2943 | lpl2797 | lpc3170 | lpa4193 | lpw31531 | llo0197 | llb1676 | + | + | + | – | Unknown |

| lpg2885 | lpp2944 | lpl2798 | lpc3171 | – | lpw31541 | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg2888 | lpp2947 | lpl2801 | lpc3174 | lpa4199 | lpw31571 | llo0200 | llb1672 | + | + | + | – | Unknown |

| lpg2912 | lpp2980 | lpl2830 | lpc3214 | lpa4255 | lpw31931 | – | – | − | − | − | – | Unknown |

| lpg2936 | lpp3004 | lpl2865 | lpc3243 | lpa4293 | lpw32251 | llo0081 | llb1804 | + | + | + | – | rRNA small subunit methyltransferase E |

| lpg2975 | lpp3047 | lpl2904 | lpc3290 | lpa4358 | −? | llo3405 | llb1930 | + | + | + | – | Unknown |

| lpg2999 | lpp3071 | lpl2927 | lpc3315 | lpa4395 | lpw32851 | – | – | − | − | − | legP | Astacin protease |

| lpg3000 | lpp3072 | lpl2928 | lpc3316 | lpa4397 | lpw32861 | llo3444 | llb1887 | + | + | + | – | Unknown |

List of substrates is based on Isberg et al. (2009), De Felipe et al. (2008), Ninio et al. (2009), Zhu et al. (2011); AT = ATCC33462; *pseudogene, +? or −? strains 130b, C-4E7 and 98072 are not a finished sequence and not manually curated. Thus absence of a substrate can also be due to gaps in the sequence; shaded in gray, substrates conserved in all L. pneumophila and L. longbeachae genomes.

Taken together the T2SS Lsp and the T4SS Dot/Icm are highly conserved between L. pneumophila and L. longbeachae. However, more than a third of the known L. pneumophila type II- and over 70% of type IV-dependent substrates differ between both species. These species specific, secreted effectors might be implicated in the different niche adaptations and host susceptibilities. Most interestingly, of the 98 L. pneumophila substrates conserved in L. longbeachae 87 are also present in all L. pneumophila strains sequenced to date. Thus, these 87 Dot/Icm substrates might be essential for intracellular replication of Legionella and represent a minimal toolkit for intracellular replication that has been acquired before the divergence of the two species.

Molecular Mimicry is a Major Virulence Strategy of L. pneumophila and L. longbeachae

The L. pneumophila genome sequence analysis has revealed that many of the predicted or experimentally verified Dot/Icm secreted substrates are proteins similar to eukaryotic proteins or contain motifs mainly or only found in eukaryotic proteins (Cazalet et al., 2004; De Felipe et al., 2005). Thus comparative genomics suggested that L. pneumophila encodes specific virulence factors that have evolved during its evolution with eukaryotic host cells such as fresh-water ameba (Cazalet et al., 2004). The protein-motifs predominantly found in eukaryotes, which were identified in the L. pneumophila genomes are ankyrin repeats, SEL1 (TPR), Set domain, Sec7, serine threonine kinase domains (STPK), U-box, and F-box motifs. Examples for eukaryotic like proteins of L. pneumophila are two secreted apyrases, a sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase and sphingosine kinase, eukaryotic like glycoamylase, cytokinin oxidase, zinc metalloprotease, or an RNA binding precursor (Cazalet et al., 2004; De Felipe et al., 2005; Bruggemann et al., 2006). Function prediction based on similarity searches suggested that many of these proteins are implicated in modulating host cell functions to the pathogens advantage (Cazalet et al., 2004). Recent functional studies confirm these predictions.

As a first example, it was shown that L. pneumophila is able to interfere with the host ubiquitination pathway. The L. pneumophila U-box containing protein LubX was shown to be a secreted effector of the Dot/Icm secretion system that mediates polyubiquitination of a host kinase Clk1 (Kubori et al., 2008). Recently, LubX was described as the first example of an effector protein, which targets and regulates another effector within host cells, as it functions as an E3 ubiquitin ligase that hijacks the host proteasome to specifically target the bacterial effector protein SidH for degradation. Delayed delivery of LubX to the host cytoplasm leads to the shutdown of SidH within the host cells at later stages of infection. This demonstrates a sophisticated level of co-evolution between eukaryotic cells and L. pneumophila involving an effector that functions as a key regulator to temporally coordinate the function of a cognate effector protein (Kubori et al., 2010; Luo, 2011). Furthermore, AnkB/Lpp2028, one of the three F-box proteins of L. pneumophila, was shown to be a T4SS effector that is implicated in virulence of L. pneumophila and in recruiting ubiquitinated proteins to the LCV (Al-Khodor et al., 2008; Price et al., 2009; Habyarimana et al., 2010; Lomma et al., 2010).

A second example is the apyrases (Lpg1905 and Lpg0971) encoded in the L. pneumophila genomes. Indeed, both are secreted enzymes important for intracellular replication of L. pneumophila. Lpg1905 is a novel prokaryotic ecto-NTPDase, similar to CD39/NTPDase1, which is characterized by the presence of five apyrase-conserved regions and enhances the replication of L. pneumophila in eukaryotic cells (Sansom et al., 2007). Apart from ATP and ADP, Lpg1905 also cleaves GTP and GDP with similar efficiency to ATP and ADP, respectively (Sansom et al., 2008). A third example is a L. pneumophila homolog of the highly conserved eukaryotic enzyme sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase (Spl). In eukaryotes, SPL is an enzyme that catalyzes the irreversible cleavage of sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P). S1P is implicated in various physiological processes like cell survival, apoptosis, proliferation, migration, differentiation, platelet aggregation, angiogenesis, lymphocyte trafficking and development. Despite the fact that the function of the L. pneumophila Spl remains actually unknown, the hypothesis is that it plays a role in autophagy and/or apoptosis (Cazalet et al., 2004; Bruggemann et al., 2006). Recently it has been shown that the L. pneumophila Spl is a secreted effector of the Dot/Icm T4SS, that it is able to complement the sphingosine-sensitive phenotype of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Moreover, L. pneumophila Spl co-localizes to the host cell mitochondria (Degtyar et al., 2009).

Taken together, the many different functional studies undertaken based on the results of the genome sequence analyses deciphering the roles of the eukaryotic like proteins have clearly established that they are secreted virulence factors that are involved in host cell adhesion, formation of the LCV, modulation of host cell functions, induction of apoptosis and egress of Legionella (Nora et al., 2009; Hubber and Roy, 2010). Most of these effector proteins are expressed at different stages of the intracellular life cycle of L. pneumophila (Bruggemann et al., 2006) and are delivered to the host cell by the Dot/Icm T4SS. Thus molecular mimicry of eukaryotic proteins is a major virulence strategy of L. pneumophila.

As expected, eukaryotic like proteins and proteins encoding domains mainly found in eukaryotic proteins are also present in the L. longbeachae genomes. However, between the two species a considerable diversity in the repertoire of these proteins exists. For example Spl, LubX, the three L. pneumophila F-box proteins, and the homolog of one (Lpg1905) of the two apyrases are missing in all sequenced L. longbeachae genomes. In contrast a glycoamylase (Herrmann et al., 2011) and an uridine kinase homolog are present also in L. longbeachae (Cazalet et al., 2010; Kozak et al., 2010; Table 3). However, other proteins encoded by the L. longbeachae genome contain U-box and F-box domains and might therefore fulfill similar functions. Thus, although the specific proteins may not be conserved, the eukaryotic like protein–protein interaction domains found in L. pneumophila are also present in L. longbeachae.

The differences in trafficking between L. longbeachae and L. pneumophila mentioned above might be related to specific effectors encoded by L. longbeachae. A search for such specific putative effectors of L. longbeachae identified several proteins that might contribute to these differences like a family of Ras-related small GTPases (Cazalet et al., 2010; Kozak et al., 2010). These proteins may be involved in vesicular trafficking and thus may account at least partly for the specificities of the L. longbeachae life cycle. L. pneumophila is also known to exploit monophosphorylated host phosphoinositides (PI) to anchor the effector proteins SidC, SidM/DrrA, LpnE, and LidA to the membrane of the replication vacuole (Machner and Isberg, 2006; Murata et al., 2006; Weber et al., 2006, 2009; Newton et al., 2007; Brombacher et al., 2009). L. longbeachae may employ an additional strategy to interfere with the host PI as a homolog of the mammalian PI metabolizing enzyme phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase was identified in its genome. One could speculate that this protein allows direct modulation of the host cell PI levels.

Interestingly, although 23 of the 29 ankyrin proteins identified in the L. pneumophila strains are absent from the L. longbeachae genome, L. longbeachae encodes a total of 23 specific ankyrin repeat proteins (Table 3). For example, L. pneumophila AnkX/AnkN that was shown to interfere with microtubule-dependent vesicular transport is missing in L. longbeachae (Pan et al., 2008). However, L. longbeachae encodes a putative tubulin–tyrosine ligase (TTL). TTL catalyzes the ATP-dependent post-translational addition of a tyrosine to the carboxy terminal end of detyrosinated alpha-tubulin. Although the exact physiological function of alpha-tubulin has so far not been established, it has been linked to altered microtubule structure and function (Eiserich et al., 1999). Thus this protein might take over this function in L. longbeachae.

Legionella longbeachae is the first bacterial genome encoding a protein containing an Src Homology 2 (SH2) domain. SH2 domains, in eukaryotes, have regulatory functions in various intracellular signaling cascades. Furthermore, L. longbeachae encodes two proteins with pentatricopeptide repeat (PPR) domains. This family seems to be greatly expanded in plants, where they appear to play essential roles in organellar RNA metabolism (Lurin et al., 2004; Nakamura et al., 2004; Schmitz-Linneweber and Small, 2008). Only 12 bacterial PPR domain proteins have been identified to date, all encoded by two species, the plant pathogens Ralstonia solanacearum and the facultative photosynthetic bacterium Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Thus, genome analysis revealed a particular feature of the Legionella genomes, the presence of many eukaryotic like proteins and protein domains, some of which are common to the two Legionella species, others which are specific and may thus account for the species specific features in intracellular trafficking and niche adaptation in the environment.

Surface Structures – A Clue to Mouse Susceptibility to Infection with Legionella

Despite the presence of many different species of Legionella in aquatic reservoirs, the vast majority of human disease is caused by a single serogroup (Sg) of a single species, namely L. pneumophila Sg1, which is responsible for about 84% of all cases worldwide (Yu et al., 2002). Similar results are obtained for L. longbeachae. Two serogroups are described, but L. longbeachae Sg1 is predominant in human disease. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is the basis for the classification of serogroups but it is also a major immunodominant antigen of L. pneumophila and L. longbeachae. Interestingly, it has also been shown that membrane vesicles shed by virulent L. pneumophila containing LPS are sufficient to inhibit phagosome–lysosome fusion (Fernandez-Moreira et al., 2006). Results obtained from large-scale genome comparisons of L. pneumophila suggested that LPS of Sg1 itself might be implicated in the predominance of Sg1 strains in human disease compared to other serogroups of L. pneumophila and other Legionella species (Cazalet et al., 2008). A comparative search for LPS coding regions in the genome of L. longbeachae NSW 150 identified two gene clusters encoding proteins that could be involved in production of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and/or capsule. Neither shared homology with the L. pneumophila LPS biosynthesis gene cluster suggesting considerable differences in this major immunodominant antigen between the two Legionella species. However, homologs of L. pneumophila lipidA biosynthesis genes (LpxA, LpxB, LpxD, and WaaM) are present. Electron microscopy also demonstrated that, in contrast to L. pneumophila, L. longbeachae produces a capsule-like structure, suggesting that one of the aforementioned gene cluster encodes LPS and the other the capsule (Cazalet et al., 2010).

As mentioned in the introduction, only A/J mice are permissive for replication of L. pneumophila, in contrast A/J, C57BL/6, and BALB/c mice are all permissive for replication of L. longbeachae. In C57BL/6 mice cytosolic flagellin of L. pneumophila triggers Naip5-dependent caspase-1 activation and subsequent proinflammatory cell death by pyroptosis rendering them resistant to infection (Diez et al., 2003; Wright et al., 2003; Molofsky et al., 2006; Ren et al., 2006; Zamboni et al., 2006; Lamkanfi et al., 2007; Lightfield et al., 2008). Genome analysis shed light on the reasons for these differences. L. longbeachae does not carry any flagellar biosynthesis genes except the sigma factor FliA, the regulator FleN, the two-component system FleR/FleS and the flagellar basal body rod modification protein FlgD (Cazalet et al., 2010; Kozak et al., 2010). Analysis of the genome sequences of strains L. longbeachae D-4968, ATCC33642, 98072, and C-4E7 as well as a PCR-based screening of 50 L. longbeachae isolates belonging to both serogroups by Kozak et al. (2010) and of 15 additional isolates by Cazalet et al. (2010) did not detect flagellar genes in any isolate confirming that L. longbeachae, in contrast to L. pneumophila does not synthesize flagella. Interestingly, all genes bordering flagellar gene clusters are conserved between L. longbeachae and L. pneumophila, suggesting deletion of these regions from the L. longbeachae genome. This result suggests, that L. longbeachae fails to activate caspase-1 due to the lack of flagellin, which may also partly explain the differences in mouse susceptibility to L. pneumophila and L. longbeachae infection. The putative L. longbeachae capsule may also contribute to this difference.

Quite interestingly, although L. longbeachae does not encode flagella, it encodes a putative chemotaxis system. Chemotaxis enables bacteria to find favorable conditions by migrating toward higher concentrations of attractants. In many bacteria, the chemotactic response is mediated by a two-component signal transduction pathway, comprising a histidine kinase CheA and a response regulator CheY. Homologs of this regulatory system are present in the L. longbeachae genomes sequenced (Cazalet et al., 2010; Kozak et al., 2010). Furthermore, two homologs of the “adaptor” protein CheW that associate with CheA or cytoplasmic chemosensory receptors are present. Ligand-binding to receptors regulates the autophosphorylation activity of CheA in these complexes. The CheA phosphoryl group is subsequently transferred to CheY, which then diffuses away to the flagellum where it modulates motor rotation. Adaptation to continuous stimulation is mediated by a methyltransferase CheR. Together, these proteins represent an evolutionarily conserved core of the chemotaxis pathway, common to many bacteria and archea (Kentner and Sourjik, 2006; Hazelbauer et al., 2008). Homologs of all these proteins are present in the L. longbeachae genomes (Cazalet et al., 2010; Kozak et al., 2010) and a similar chemotaxis system is present in Legionella drancourtii LLAP12 (La Scola et al., 2004) but it is absent from L. pneumophila. The flanking genomic regions are highly conserved among L. longbeachae and all L. pneumophila strains sequenced, suggesting that L. pneumophila, although it encodes flagella has lost the chemotaxis system encoding genes by deletion events.

Thus these two species differ markedly in their surface structures. L. longbeachae encodes a capsule-like structure, synthesizes a very different LPS, does not synthesize flagella but encodes a chemotaxis system. These differences in surface structures seem to be due to deletion events leading to the loss of flagella in L. longbeachae and the loss of chemotaxis in L. pneumophila leading in part to the adaptation to their different main niches, soil, and water.

Evolution of Eukaryotic Effectors – Acquisition by Horizontal Gene Transfer from Eukaryotes?

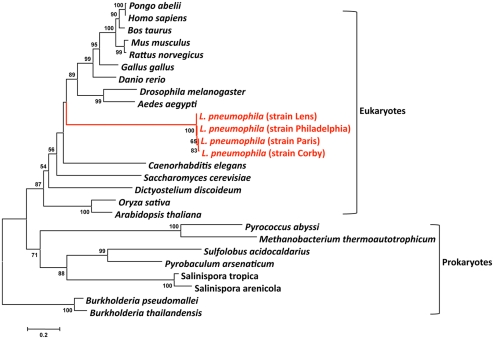

Human to human transmission of Legionella has never been reported. Thus humans have been inconsequential in the evolution of these bacteria. However, Legionella have co-evolved with fresh-water protozoa allowing the adaptation to eukaryotic cells. The idea that protozoa are training grounds for intracellular pathogens was born with the finding by Rowbotham (1980) that Legionella has the ability to multiply intracellularly. This lead to a new percept in microbiology: bacteria parasitize protozoa and can utilize the same process to infect humans. Indeed, the long co-evolution of Legionella with protozoa is reflected in its genome by the presence of eukaryotic like genes, many of which are clearly virulence factors used by L. pneumophila to subvert host functions. These genes may have been acquired either through horizontal gene transfer (HGT) from the host cells (e.g., aquatic protozoa) or from bacteria or may have evolved by convergent evolution. Recently it has been reported that L. drancourtii a relative of L. pneumophila has acquired a sterol reductase gene from the Acanthamoeba polyphaga Mimivirus genome, a virus that grows in ameba (Moliner et al., 2009). Thus, the acquisition of some of the eukaryotic like genes of L. pneumophila by HGT from protozoa is plausible. ralF was the first gene suggested to have been acquired by L. pneumophila from eukaryotes by HGT, as RalF carries a eukaryotic Sec 7 domain (Nagai et al., 2002). In order to study the evolutionary origin of eukaryotic L. pneumophila genes, we have undertaken a phylogenetic analysis of the eukaryote-like sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase of L. pneumophila that is encoded by lpp2128 described earlier. The phylogenetic analyses shown in Figure 4 revealed that it was most likely acquired from a eukaryotic organism early during Legionella evolution (Degtyar et al., 2009; Nora et al., 2009) as the Lpp2128 protein sequence of L. pneumophila clearly falls into the eukaryotic clade of SPL sequences.

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic tree of a multiple sequence comparison of sphingosine-phosphate lyase proteins present in eukaryotic and prokaryotic genomes. Phylogenetic reconstruction was done with MEGA using the Neighbor-Joining method. Numbers indicate bootstrap values after 1000 bootstrap replicates. The red lines indicate the L. pneumophila sequences that are embedded in the eukaryotic clade. The bar at the bottom represents the estimated evolutionary distance.