INTRODUCTION

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a chronic cholestatic syndrome with autoimmune features and is associated with other immunological diseases such as autoimmune pancreatitis and inflammatory bowel disease. In addition to primary biliary cirrhosis, PSC is one of the most common chronic cholestatic liver diseases.1

The diagnosis of PSC is a challenge because patients are asymptomatic or display unspecific symptoms. Patients experience fatigue, pruritus, and jaundice. In addition, symptom onset is not associated with age. The diagnosis of PSC is typically achieved after a complication such as cholangitis or hepatic dysfunction occurs. Patients may experience periods of remission. Laboratory tests show cholestatic profiles with high levels of alkaline phosphatases (APs), gamma-glutamyltransferases (GGTs) and, occasionally, greater bilirubin levels. Definitive diagnosis is achieved using imaging methods to assist in the differential diagnosis.2

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC) has been considered the gold-standard diagnostic method for PSC.1 However, ERC has its inherent risks such as acute pancreatitis, cholangitis, and duodenum perforation.3 Moreover, in a patient with biliary chronic disease, the loss of the Oddi sphincter barrier may lead to acute complications and chronic problems such as recurrent cholangitis, liver abscesses, and reduced liver function.4

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is an attractive option for PSC diagnosis. Many studies have reported that MRI has similar sensitivity to ERC for PSC and has the remarkable advantages of being less invasive and less likely to cause complications.5

In this case report, we present two patients with PSC who had serious complications after ERC with recurrent cholangitis and are on the waiting list for a liver transplant.

CASE 1: A 51-year-old male patient with a previous diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and complaints of chronic fatigue and pruritus was referred to our hospital. Liver function tests showed normal transaminase levels and a two-fold increase in the alkaline phosphatase and gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase levels. A cholangio-NMR (c-NMR) study showed a pattern of stenosis and dilation that suggested a diagnosis of primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) (Figure 1). The patient underwent ERCP with papillotomy, which confirmed this diagnosis. After three days, the patient presented with a fever, leukocytosis, and chills. He developed multiple intra-hepatic abscesses. Acute cholangitis was diagnosed and successfully treated with long-term IV antibiotics.

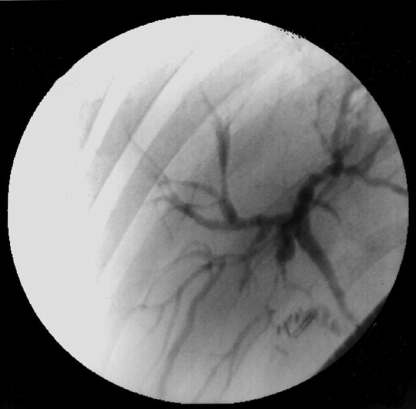

Figure 1.

Cholangio-NMR showing intrahepatic bile-duct strictures that are consistent with a diagnosis of PSC.

After three years, the patient experienced three more episodes of cholangitis, which were treated with IV antibiotics. He is currently on daily prophylactic treatment with ciprofloxacin and remains asymptomatic.

CASE 2: A 39-year-old woman started having diarrhea, hepatomegaly, jaundice, and elevated canalicular enzymes seven years ago. An ERCP with papillotomy was performed, and the findings strongly supported the diagnosis of PSC (Figure 2). Since then, the patient has experienced at least four major attacks of acute cholangitis that necessitated inpatient treatment. She is currently receiving prophylactic ciprofloxacin daily and is asymptomatic. However, she developed hepatic cirrhosis with portal hypertension. Three months ago, she experienced upper gastrointestinal bleeding due to esophageal varices. Liver transplantation has been indicated, and her current MELD score is 17.

Figure 2.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography showing intra- and extrahepatic bile-duct strictures and dilations.

DISCUSSION

The etiology of PSC remains elusive. PSC is related to other autoimmune diseases, such as IBD and autoimmune pancreatitis (AP). Genetic studies have demonstrated the expression of the haplotypes HLA A1-B8-DR3, DR-6, and DR-2 in some cases of PSC. HLA DR-4 expression is related to protective effects that are not specific for PSC. The lack of specificity of these markers remains a challenge in PSC diagnosis.6

PSC affects more men than women (2∶1). Early clinical findings are nonspecific. Fatigue, anorexia, and arthralgia are common symptoms. Jaundice and pruritus are not rare and are troublesome for the patients.2

Laboratory tests have shown a typical cholestatic profile with elevated alkaline phosphatase and gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase levels. Occasionally, slight elevations of transaminases and bilirubin have been noted. Several auto-antibody studies have indicated elevated p-ANCA and anti-nuclear antibodies. However, elevated auto-antibodies are unspecific for PCS. 2,6

Imaging studies are fundamental to the investigation of any cholestatic disease. The intra- and extra-hepatic biliary tree must be thoroughly examined to achieve a differential diagnosis.1,2,5 In the past, ERCP and percutaneous cholangiography have been widely used. ERCP is considered the gold-standard diagnostic technique for PSC because the documentation of detailed biliary anatomy that is achieved with this method is informative. However, ERCP is associated with complications, including biliary contamination, cholangitis and pancreatitis.7 New conservative methods to assess biliary anatomy such as endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and cholangio-NMR jeopardize the former pivotal role of ERCP as the gold-standard technique for the diagnosis of PSC. Ciorcilan et al. have analyzed the ERCP-associated complications in patients with cholestatic diseases and have concluded that this method is indicated only when diagnosis is not possible with EUS or cholangio-NMR or in patients that require therapeutic intervention.8

Some studies have shown that ERCP may be dangerous for patients with PSC.9,10 In patients with PSC, liver function may be impaired after ERCP. Beuers et al. have demonstrated that cholestasis worsened after ERCP in 53% of patients with PSC. A bilirubin level that exceeds 1.0 mg/dl in elderly patients is a risk factor for complications.4

In recent years, cholangio-NMR has undergone a significant technical evolution and is a preferred tool to investigate cholestatic disease. Vitellas et al. have compared the efficacies of ERCP and cholangio-NMR in the diagnosis of PSC and concluded that c-NMR defines peripheral biliary lesions more effectively than ERCP.11 Textor et al. have concluded that the sensitivity and specificity of c-NMR are similar to those of ERCP in the diagnosis of PSC and has fewer complications than ERCP.12

Talwalkar et al. have performed a prospective analysis of cost-effectiveness and concluded that c-NMR is more valuable than ERCP as a diagnostic procedure for cholestatic diseases.13 However, ERCP remains a valuable therapeutic method to manipulate the biliary tree (removal of sludge and stones and the dilation of the duct).

The cases described in the current report emphasize a rare but potentially dangerous complication following ERCP in patients with PSC: acute and recurrent cholangitis (RC). Nevertheless, there are other similar clinical complications. Analysis of liver transplantation explants showed that bacteriobilia is more frequent in patients with PSC than in patients with PBC.14 Moreover, ERCP increases colonization by pathogenic flora, which may originate from the endoscope itself.15 Furthermore, when performing ERCP in patients with cholestatic disease, a wide papillotomy may be necessary for complete contrast wash-out of the biliary tree. Afterward, duodenal-biliary reflux may occur, leading to chronic biliary contamination.16,17

These data support the idea that chronic cholangitis is similar to the recurrent events of acute cholangitis and may lead to the deterioration of global liver function in patients with cholestatic diseases. Therefore, the contamination of a diseased biliary tree should be avoided whenever possible.

ERCP with papillotomy may complicate cholestatic liver disease. Because other non-invasive tests such as cholangio-NMR are currently widely available, we believe that ERCP has a limited role in the diagnosis of PSC and should be indicated only for therapeutic purposes in patients with PSC.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Angulo P, Lindor KD. Primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology. 1999;30:325–32. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300101. 10.1002/hep.510300101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schrumpf E, Boberg KM. Primary sclerosing cholangitis: challenges of a new millenium. Dig Liver Dis. 2000;32:753–5. doi: 10.1016/s1590-8658(00)80350-3. 10.1016/S1590-8658(00)80350-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moff SL, Kamel IR, Eustace J, Lawler LP, Kantsevoy S, Kalloo AN, et al. Diagnosis of primary sclerosing cholangitis: a blinded comparative study using magnetic resonance cholangiography and endoscopic retrograde cholangiography. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:219–23. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.12.034. 10.1016/j.gie.2005.12.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beuers U, Spengler U, Sackmann M, Paumgartner G, Sauerbruch T. Deterioration of cholestasis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiography in advanced primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Hepatol. 1992;15:140–3. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(92)90026-l. 10.1016/0168-8278(92)90026-L [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Angulo P, Pearce DH, Johnson CD, Henry JJ, LaRusso NF, Petersen BT, et al. Magnetic resonance cholangiography in patients with biliary disease: its role in primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Hepatol. 2000;33:520–7. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0641.2000.033004520.x. 10.1034/j.1600-0641.2000.033004520.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maggs JR, Chapman RW. Sclerosing cholangitis. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2007;23:310–6. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32805867e6. 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32805867e6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ang TL, Fock KM, Ng TM, Teo EK, Chua TS, Tan JY. Clinical profile of primary sclerosing cholangitis in Singapore. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:908–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2002.02835.x. 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2002.02835.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ciocirlan M, Ponchon T. Diagnostic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Endoscopy. 2004;36:137–46. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-814181. 10.1055/s-2004-814181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Enns R, Eloubeidi MA, Mergener K, Jowell PS, Branch MS, Baillie J. Predictors of successful clinical and laboratory outcomes in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis undergoing endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Can J Gastroenterol. 2003;17:243–8. doi: 10.1155/2003/475603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christensen M, Hendel HW, Rasmussen V, Hojgaard L, Schulze S, Rosenberg J. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography causes reduced myocardial blood flow. Endoscopy. 2002;34:797–800. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-34270. 10.1055/s-2002-34270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vitellas KM, El-Dieb A, Vaswani KK, Bennett WF, Tzalonikou M, Mabee C, et al. MR cholangiopancreatography in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis: interobserver variability and comparison with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:399–407. doi: 10.2214/ajr.179.2.1790399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Textor HJ, Flacke S, Pauleit D, Keller E, Neubrand M, Terjung B, et al. Three-dimensional magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography with respiratory triggering in the diagnosis of primary sclerosing cholangitis: comparison with endoscopic retrograde cholangiography. Endoscopy. 2002;34:984–90. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-35830. 10.1055/s-2002-35830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Talwalkar JA, Angulo P, Johnson CD, Petersen BT, Lindor KD. Cost-minimization analysis of MRC versus ERCP for the diagnosis of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology. 2004;40:39–45. doi: 10.1002/hep.20287. 10.1002/hep.20287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosch T, Triptrap A, Born P, Ott R, Weigert N, Frimberger E, et al. Bacteriobilia in percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage: occurrence over time and clinical sequelae. A prospective observational study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:1162–8. doi: 10.1080/00365520310003549. 10.1080/00365520310003549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pohl J, Ring A, Stremmel W, Stiehl A. The role of dominant stenoses in bacterial infections of bile ducts in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:69–74. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200601000-00012. 10.1097/00042737-200601000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bordas JM, Elizalde I, Llach J, Mondelo F, Bataller R, Teres J. Biliary reflux due to sphincter of Oddi ablation: a new pathogenetic explanation for long-term major biliary symptoms after endoscopic-sphincterotomy. Endoscopy. 1996;28:642. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1005568. 10.1055/s-2007-1005568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mandryka Y, Klimczak J, Duszewski M, Kondras M, Modzelewski B. [Bile duct infections as a late complication after endoscopic sphincterotomy] Pol Merkur Lekarski. 2006;21:525–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]