Abstract

Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors have emerged as a new class of anticancer drugs, with one synthetic compound, SAHA (vorinostat, Zolinza®; 1), and one natural product, FK228 (depsipeptide, romidepsin, Istodax®; 2), approved by FDA for clinical use. Our studies of FK228 biosynthesis in Chromobacterium violaceum No. 968 led to the identification of a cryptic biosynthetic gene cluster in the genome of Burkholderia thailandensis E264. Genome mining and genetic manipulation of this gene cluster further led to the discovery of two new products, thailandepsin A (6) and thailandepsin B (7). HDAC inhibition assays showed that thailandepsins have selective inhibition profiles different from that of FK228, with comparable inhibitory activities to those of FK228 toward human HDAC1, HDAC2, HDAC3, HDAC6, HDAC7 and HDAC9, but weaker inhibitory activities than FK228 toward HDAC4 and HDAC8, the later of which could be beneficial. NCI-60 anticancer screening assays showed that thailandepsins possess broad-spectrum antiproliferative activities with GI50 for over 90% of the tested cell lines at low nanomolar concentrations, and potent cytotoxic activities towards certain types of cell lines, particularly for those derived from colon, melanoma, ovarian and renal cancers. Thailandepsins thus represent new naturally produced HDAC inhibitors that are promising for anticancer drug development.

Keywords: Antiproliferation, Burkholderia thailandensis, genome mining, histone deacetylase inhibitor, thailandepsins

Epigenetic abnormalities participate with genetic mutations to cause cancer,1 and consequently epigenetic intervention of cancer has emerged as a promising avenue toward cancer therapy. Selective inhibition of histone deacetylases (HDACs) by small molecules often leads to a cascade of chromatin remodeling, tumor suppressor gene reactivation, apoptosis, and regression of cancer.2 HDAC inhibitors have thus gained much attention in recent years as a new class of anticancer agents.2–6 One synthetic HDAC inhibitor, SAHA (vorinostat, Zolinza®; 1), and one natural product HDAC inhibitor, FK228 (depsipepide, romidepsin, Istodax®; 2), have already been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma,7, 8 and many more HDAC inhibitors (mostly synthetic molecules) are in various stages of preclinical or clinical trials as single agents or in combination with other chemotherapy drugs, for diverse cancer types.5, 9, 10

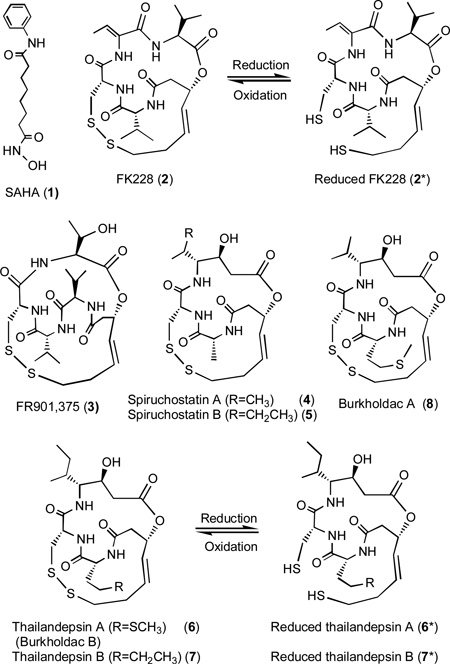

FK228 is produced by Chromobacterium violaceum No. 968.11, 12 It belongs to a small family of natural products that also includes FR901,375 (3),13 spiruchostatins A (4) and B (5),14 thailandepsins A (6) and B (7) discovered by us (15 and this article; 15 is a US patent application filed on August 19, 2010 and published online on March 10, 2011, with a priority date of August 19, 2009), and burkholdacs A (8) and B (identical to 6) reported recently by Biggins et al. (appeared online on February 26, 2011).16 All members of this family of natural products are produced by rare Gram-negative bacteria, and each of them contains a signature disulfide bond that is known or presumed to mediate its anticancer activity via reduction of the disulfide bond to generate a free thiol group (“warhead”) that chelates a Zn2+ in the catalytic center of Class I and Class II HDACs, thereby inhibiting the enzyme activities.17 The biosynthesis of FK228 is proposed to follow a widely accepted “assembly-line” mechanism18–20 in which simple building blocks (amino acids, amino acid derivatives and short carboxylic acids from primary metabolism) are assembled step-wise by seven modules of a hybrid nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS)-polyketide synthase (PKS) multifunctional pathway to afford a linear intermediate, which is subsequently cyclized by a terminal thioesterase (TE) domain to form an immediate FK228 precursor.21 An FAD-dependent oxidoreductase is responsible for a disulfide bond formation as the final step of FK228 biosynthesis.22

Historically natural products have made tremendous contributions to human medicines.23, 24 Despite the controversial downsizing of natural product-based drug discovery efforts by the pharmaceutical industry in the past two decades, there has been a sign of renaissance of natural product discovery activities in recent years, largely due to new technology advances and unmet need of new drugs for chronic and emerging diseases.20, 25 Genome mining, which takes advantage of the rapid growth of microbial genome sequence information and in-depth understanding of natural product biosynthetic logics, has emerged as an effective new approach for the discovery of molecules encoded in cryptic biosynthetic gene clusters.26, 27

In this article we report the discovery of two FK228-analogues, 6 and 7, from the fermentation broth of a genome-sequenced bacterium, by a combination of several enabling technologies including genome mining and metabolic profiling. Enzyme inhibition assays showed that 6 and 7 are potent inhibitors of human HDACs. NCI-60 anticancer screening28, 29 demonstrated broad-spectrum antiproliferative activities of 6 and 7 against an array of human cancer cell lines. Therefore 6 and 7 represent new naturally produced HDAC inhibitors that are promising for anticancer drug development.

Results and Discussion

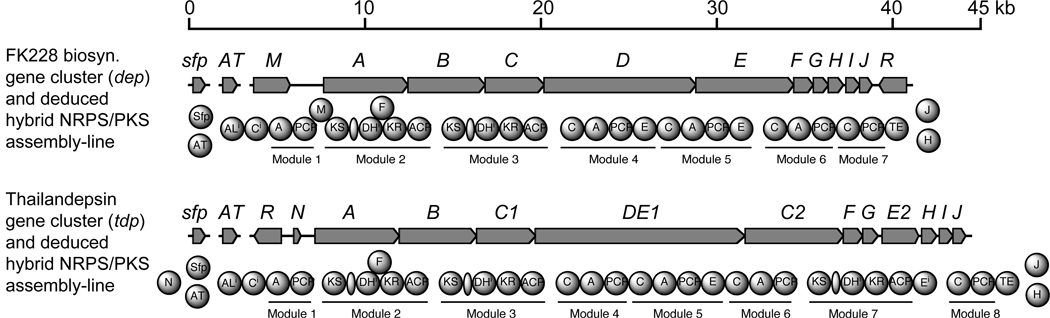

Identification of a cryptic biosynthetic gene cluster

The goal of our research is to explore naturally produced, and biologically or chemically engineered members of the FK228-family of HDAC inhibitors as new anticancer agents. To this end, we have cloned and characterized a biosynthetic gene cluster (designated dep for depsipeptide FK228) and three discrete genes collectively responsible for FK228 biosynthesis in C. violaceum.21, 30, 31 Those studies provided us the first-hand opportunity to identify a cryptic biosynthetic gene cluster (designated tdp for thailandepsins) in the published genome of Burkholderia thailandensis E264 (GenBank accession no. CP000085 and CP000086)32 (Figure 1). The genes and their deduced proteins of this tdp gene cluster exhibit a significant overall similarity to those of the dep gene cluster (Table 1). In particular, the deduced products of eight genes (tdpA, tdpB, tdpC1, tdpF, tdpG, tdpH, tdpI, and tdpJ) share 67%/80% or higher sequence identity/similarity with their respective counterparts from the FK228 biosynthetic pathway. Like the dep gene cluster, this tdp gene cluster does not contain any gene that encodes a phosphopantetheinyltransferase (PPTase) necessary for posttranslational modification of carrier proteins33 or an acyltransferase (AT) necessary for in trans complementing the three “AT-less” PKS modules34 on TdpB, TdpC1 and TdpC2 proteins. A thorough search of the B. thailandensis genome found multiple candidate genes that may encode the missing PPTase or AT activity; experimental verification of the responsible gene (tentatively named tdp_sfp or tdp_AT) is in progress. A few differences between the two parallel gene clusters are identified as follows: (i) unlike depR which is located downstream of the dep gene cluster and encodes an OxyR-type transcriptional activator, tdpR is located upstream of the tdp gene cluster and encodes a putative AraC-type transcriptional regulator. These two deduced regulatory proteins do not have notable sequence homology; (ii) there is no depM-equivalent in the tdp gene cluster; (iii) there are two copies of a depC-like gene in the tdp gene cluster, the second copy is fused to DNA encoding a likely inactive epimerase (E) domain and is located after tdpDE1; (iv) a depE-like gene in the tdp gene cluster is split into two parts, the first part is fused to the end of tdpD, and the second part is transposed to a downstream location between tdpG and tdpH; (v) unlike pseudogene “depN”, the deduced protein of tdpN appears to be a functional peptidyl carrier protein (PCP) with a critical serine residue for phosphopantetheinylation.

Figure 1. Comparison of two homologous biosynthetic gene clusters and discrete genes necessary for the biosynthesis of FK228 (2) or thailandepsins A (6) and B (7).

Each gene cluster is depicted in a row, under which is the deduced respective modular biosynthetic pathway. A, ACP, AL, AT, C, DH, E, KR, KS, PCP and TE are standard abbreviations of the nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) or polyketide synthase (PKS) domain names whose full name and respective function can be found in Fischbach et al.18 Sfp and AT are the generic protein names of their respective genes defined in the main text.

Table 1.

Comparison of two homologous biosynthetic gene clusters and their associated discrete genes necessary for product biosynthesis.

| Thailandepsin biosynthetic (tdp) gene cluster |

FK228 biosynthetic (dep) gene cluster21, 30, 31 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genea | Proteinb | Geneb | Proteinb | Percentage Ident./simil. btw prot. seq. |

Confirmed or deduced protein functionc |

| tdp_sfp (multiple candidates) (discrete)d | Tdp_Sfp |

dep_sfp (discrete)d |

Dep_Sfp | -- | Phosphopantetheinyl transferase (PPTase) |

| tdp_AT (multiple candidates) (discrete)d | Tdp_AT |

dep_fabD1 dep_fabD2 (discrete)d |

Dep_FabD1 Dep_FabD2 |

-- | Acyltransferase, malonyl CoA-specific (AT) |

| BTH_I2369 | TdpR | -- | -- | -- | AraC-type transcriptional regulator |

| -- | -- | depM | DepM | -- | Aminotransferase |

| BTH_I2368 | TdpN | -- | -- | -- | Type II peptidyl carrier protein (PCP) |

| BTH_I2367 | TdpA | depA | DepA | 74% / 83% | NRPS (1 module) |

| BTH_I2366 | TdpB | depB | DepB | 78% / 86% | PKS (1 module) |

| BTH_I2365 | TdpC1 | depC | DepC | 76% / 84% | PKS (1 module) |

| BTH_I2364 | TdpDE1 | ||||

| -1st module | depD | DepD | 56% / 67% | NRPS (1 module) | |

| -2nd module | depE | DepE | 39% / 52% | NRPS (1 module) | |

| BTH_I2363 | TdpC2 | depC | DepC | 39% / 50% | PKS (1 module) |

| BTH_I2362 | TdpF | depF | DepF | 88% / 93% | FadE2-like acyl-CoA dehydrogenase |

| BTH_I2361 | TdpG | depG | DepG | 75% / 84% | Phosphotransferase |

| BTH_I2360 | TdpE2 | depE | DepE | 31% / 49% | NRPS (partial module) |

| BTH_I2359 | TdpH | depH | DepH | 72% / 84% | FAD-dependent disulfide oxidoreductase |

| BTH_I2358 | TdpI | depI | DepI | 74% / 84% | Esterase/Lipase |

| BTH_I2357 | TdpJ | depJ | DepJ | 67% / 80% | Type II thioesterase |

| -- | -- | depR | DepR | -- | OxyR-type transcriptional regulator |

Gene annotations from the GenBank;

Gene/protein names designated by the authors;

Standard abbreviations: NRPS, nonribosomal peptide synthetase; PKS, polyketide synthase;

Detached from the perspective gene cluster;

--: not available

Using the FK228 biosynthetic pathway as a reference,21 we dissected the domain and module organization of six deduced NRPS- and PKS-type enzymes (TdpA, TdpB, TdpC1, TdpDE1, TdpC2 and TdpE2) encoded by the tdp gene cluster and proposed a hybrid NRPS-PKS biosynthetic pathway model which also includes three discrete enzymes (AT, TdpF and TdpH) (Figure S1). This proposed pathway contains eight NRPS/PKS modules responsible for seven consecutive steps of building block polymerization that results in a full-length linear intermediate installed on a PCP domain in the last module. A terminal TE domain is predicted to cleave off the intermediate and subsequently cyclize it into a macrolactam intermediate. Finally an FAD-dependent oxidoreductase (TdpH) is predicted to catalyze a disulfide bond formation as the final step of the biosynthesis of 6 and 7.

We initially predicted the putative chemical structures of compounds that may be produced by the proposed biosynthetic pathway. The predicted structures (Figure S1) were slightly different from the experimentally determined ones (6 and 7), reflecting the power and yet limitation of in silico analysis.

Discovery of thailandepsins A (6) and B (7)

We executed a series of experiments to purify and identify two new bacterial products, named thailandepsin A (6) and thailandepsin B (7), from the fermentation culture of B. thailandensis E264.

First we identified by semi-quantitative reverse transcription (RT)-PCR method several cultivation conditions in which the cryptic tdp gene cluster is highly expressed (Figure S2a). We found that two representative structural genes, tdpA and tdpJ, are expressed at significant levels at 30°C in five (M1, M2, M3, M8 and M9) of the nine production media tested (Table S1) at the 24-h time point, with the highest level in M9, a modified minimal medium. Furthermore, we found that tdpA is expressed at significant levels in the five identified media at all four time points examined, with the highest level in M9 at about 24 h (Figure S2b); the level of tdpA expression begins to decrease after 24 h but persists beyond 72 h. Medium M9 was thus selected as the optimal medium for subsequent bacterial fermentation.

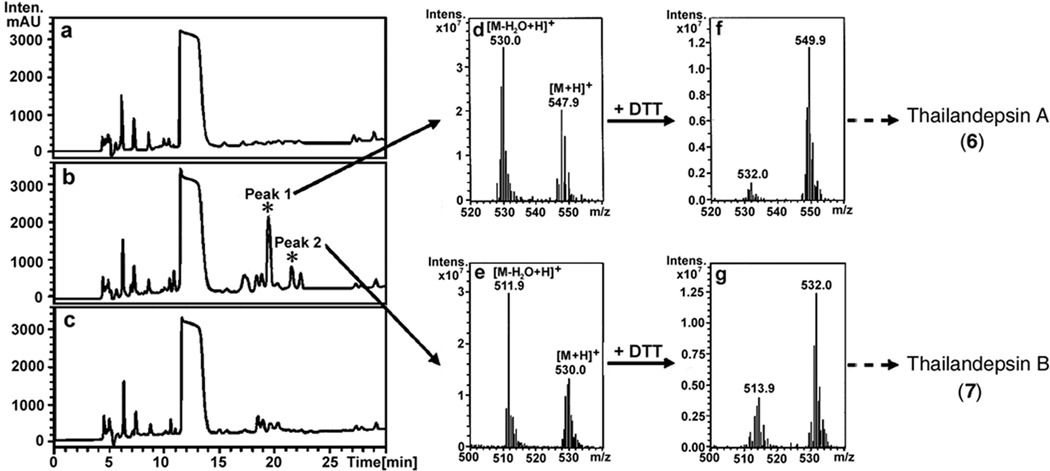

We then created a gene-deletion mutant (BthΔtdpAB) and detected metabolic profiling differences between the wild type strain (BthWT) and the mutant strain of B. thailandensis E264. We employed a well-established multiplex PCR method22, 35 to create the mutant strain in which a critical segment of the tdpAB adjoining region was permanently deleted (Figure S2c). This deletion truncated a part of the adenylation (A) domain and the entire PCP domain of the NRPS module on TdpA and a part of the ketoacyl synthase (KS) domain of the PKS module on TdpB of the thailandepsin biosynthetic pathway (Figure S1). As a result, not only three critical catalytic domains of the pathway have been impaired or deleted by the gene deletion event but also the protein-protein communication between TdpA and TdpB was disrupted. It is thus certain that the entire biosynthetic pathway must have been disabled. Subsequently both BthWT and BthΔtdpAB strains were cultivated in M9. Organic extracts of both bacterial cultures and a medium control were analyzed by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and detected the disappearance of several HPLC peaks in the BthΔtdpAB sample (Figure 2c vs. 2b). We anticipated that the corresponding peaks in the BthWT sample could be the target compounds produced by the cryptic tdp gene cluster. Those peaks were collected and examined by electrospray ionization (ESI)-LC-MS.

Figure 2. Metabolic profiling of the wild type strain (BthWT) and BthΔtdpAB mutant strain of B. thailandensis E264.

Panels a, b and c are the HPLC traces of extract of the medium control, BthWT strain or BthΔtdpAB strain, respectively. Panels d and e are ESI-LC-MS spectra of the HPLC Peak 1 and Peak 2 of the BthWT sample (Panel b). Panels f and g are ESI-LC-MS spectra of the reduced HPLC Peak 1 and Peak 2 of the BthWT sample (Panel b), showing a +2 m/z shift of every ion signal.

Importantly we observed critical chemical properties of the putative target compounds. The material of peak 1 from HPLC yielded a pair of ion signals of 547.9/530.0 m/z (Figure 2d), and the material of peak 2 sample yielded 530.0/511.9 m/z (Figure 2e). It is believed that the higher m/z signal from each pair is the protonated adduct of a target molecule [M + H]+ and the lower m/z signal is the protonated adduct of a respective target molecule with a H2O molecule removed (dehydrated; [M − H2O + H]+) by heat/electrovoltage (eV) during ESI-LC-MS. Interestingly, when the materials of HPLC peaks were first reduced with DTT and then subjected to ESI-LC-MS analysis, both samples generated ion signals with a +2 m/z mass shift, a polarity shift (more hydrophilic, as judged by an earlier elution time), and a change of the relative abundance of parental molecule/dehydrated derivative (Figure 2f and 2g). Those observations strongly suggested that we had identified two target compounds that are most likely produced by the cryptic tdp gene cluster in B. thailandensis under the fermentation conditions tested, and those compounds probably contain a disulfide bond (thus existing as a prodrug) which can be reduced/activated by DTT in the same way as FK228 by DTT.

Finally we fermented the BthWT strain in large volume in M9, and subsequently purified and identified the target compounds 6 and 7 by natural product chemistry methods including organic extraction, gravity chromatography, preparative HPLC, amino acid analysis, MS, NMR, degradation analysis, and chemical derivatization (see Supporting Information - SI).

Thailandepsins A (6) and B (7) are new FK228-class natural products

Compounds 6 and 7 are new chemical entities with distinctive features that belong to the FK228-class of natural products. Both 6 and 7 are bicyclic depsipeptides that contain a 15-membered macrolactam ring and a second 15-membered ring with a signature disulfide bond, whereas FK228 contains a 16-membered macrolactam ring and a 15-membered side ring with a signature disulfide bond. Like FK228,17, 21 the disulfide bond in 6 and 7 is predicted to be reduced inside mammalian cells to generate free thiol groups, of which one thiol group interacts with the Zn2+ inside the catalytic pocket of human HDACs, thus inhibiting the enzyme’s activity, as illustrated by molecular modeling (Figure S8).

From a biosynthetic point of view, it is apparent that both 6 and 7 are composed of building blocks of short carboxylic acids, amino acids or amino acid derivatives, consistent with the proposed model of a hybrid PKS-NRPS biosynthetic pathway (Figure S1). Compound 6 differs from 7 by having a methionine (Met) moiety where 7 has a norleucine (NLeu) moiety. According to a comprehensive database of nonribosomal peptides,36 the simultaneous presence of cysteine (Cys) and Met, two proteogenic amino acids that contain a thiol function, in nonribosomally synthesized 6, is unprecedented, and 7 appears to be the first natural product reported to contain a nonproteogenic NLeu building block. Overall, 6 and 7 are structurally more similar to 4 and 5 than to 2. In particular, 6 and 7 only differ from 5 at the Met/NLeu position where 5 has an alanine (Ala) moiety.

HDAC inhibitory activities of thailandepsins A (6) and B (7), compared to FK228 (2)

Because of a striking structural similarity between 6/7 and 2, we predicted that both 6 and 7 would likely also possess HDAC inhibitory and antiproliferative activities. To test this hypothesis, the inhibitory potency of both the oxidized form (natural, prodrug form with a disulfide bond) and the reduced form (activated form with two free thiol groups, indicated by *) of 2 (as a reference compound), 6 and 7 against recombinant human class I HDACs [HDAC1, HDAC2, HDAC3 (in complex with N-CoR2) and HDAC8], class IIa HDACs (HDAC4, HDAC7 and HDAC9) and class IIb HDAC6 was determined by a two-step fluorogenic assay.37 All HDAC dose-response curves were bundled for each compound individually (Figure S3a and S3b), and the IC50 values in µM are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

The calculated IC50 value of each compound vs. each HDAC in µM concentration.

| Enzyme | HDAC1 | HDAC2 | HDAC3 | HDAC4 | HDAC6 | HDAC7 | HDAC8 | HDAC9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibitor | ||||||||

| 2 | 6.7 | 1.5 | 0.018 | >50 | 12 | >50 | >50 | >50 |

| 2* | 0.0053 | 0.0039 | 0.0053 | 0.47 | 0.33 | 3.2 | 0.026 | 12 |

| 6 | 7.5 | 39 | 0.087 | >50 | 9.9 | >50 | >50 | >50 |

| 6* | 0.014 | 0.0035 | 0.0048 | 42 | 0.38 | 11 | 1.2 | 12 |

| 7 | 7.7 | 4.5 | 0.023 | 22 | 11 | 27 | 30 | >50 |

| 7* | 0.0065 | 0.0067 | 0.0094 | 18 | 0.61 | 24 | 1.0 | 30 |

Compounds were reduced/activated prior to being assayed.

Each of the three compounds in its reduced/activated form (2*, 6*, 7*) is a much more potent HDAC inhibitor than its natural/oxidized prodrug form (2, 6, 7). These observations are in agreement with a previous report that an enhanced inhibitory effect of the reference compound 2 was detected after being reduced with DTT and assayed against HDAC1, HDAC2, HDAC4 and HDAC6.17

Reduced thailandepsins 6* and 7* exhibited a similar ranking of inhibitory potency against human HDACs: HDAC1, HDAC2 and HDAC3 are strongly inhibited at low nanomolar concentrations; inhibition of the distantly related HDAC8 is about 80–350 times weaker than the inhibition of HDAC1–3; HDAC6 is still strongly inhibited but the potency of 2*, 6* or 7* towards HDAC6 is about 30–100 times less than to HDAC1–3; HDAC4, HDAC7 and HDAC9 are the least inhibited with IC50 values 3–4 orders of magnitude higher than those for HDAC1–3. It is apparent that all three activated compounds are more potent toward Class I HDACs than toward Class II HDACs. Thus Class I HDACs, particularly HDAC1–3, are the primary targets of inhibition by those natural products.

Interestingly there are significant differential inhibitory effects among 2*, 6* and 7* on HDAC4 and HDAC8. Both 6* and 7* are 40–90 fold less potent against HDAC4 or HDAC8 than 2*. This difference could be beneficial for drug development. Studies have shown the involvement of HDAC4 in multiple vital cellular regulation mechanisms.38–41 Although HDAC8 is a member of class I HDACs but by sequence comparison it is far away from the other members (Figure S7), therefore HDAC8 may presumably play a very different biological role than the other members of class I HDACs. Since the toxicity of HDAC inhibitors is often a bigger concern than potency in drug development, and 6* and 7* are much less inhibitory than 2* against HDAC4 and HDAC8, 6* and 7* may exhibit favorable anticancer or cytotoxicity profiles.

Surprisingly FK228 and thailandepsins in their natural/oxidized prodrug form (2, 6 and 7) appeared unexpectedly to be strong inhibitors of the HDAC3/N-CoR2 complex with IC50 values ranging from 18 to 87 nM, whereas they are 80–450 times less active against the closely related HDAC1 and HDAC2. To exclude the potential influence of traces of thiol 2* on enzyme inhibition, a series of dose-response curves of 2 in the presence of different concentrations of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was carried out against HDAC3/N-CoR2 (Figure S3c). Increasing concentrations of the oxidizing agent up to 1.0 mM resulted in decreasing levels of enzyme activity of the HDAC3/N-CoR2 complex in the absence of 2. However when assayed with 2, the IC50 values of 2 remained similarly low (Table 3), indicating that the oxidized form of 2 indeed has pronounced inhibitory activity against the HDAC3/N-CoR2 complex, perhaps by a different mode of action. This seemingly increased susceptibility of HDAC3 might be influenced by its complex with co-repressor N-CoR2. Guenther et. al.42 have shown that HDAC3 is completely inactive on its own but is activated by forming a stable complex with the nuclear hormone receptor co-repressor N-CoR2. Therefore, N-CoR2 is required both for activation of HDAC3 and for its recruitment of other nuclear repressors. It is speculated that the FK228-family of HDAC inhibitors may display their effects either through binding outside of the active site of HDAC3 to its complex with N-CoR2 or by interfering directly with the interaction between HDAC3 and N-CoR2, yielding inactive uncomplexed HDAC3. The concept of disturbing the formation of the HDAC3/N-CoR2 complex could open new routes to selective inhibitors against HDAC3, since the ability of N-CoR2 to activate HDAC is specific to HDAC3.42

Table 3.

The influence of different H2O2 concentrations on the potency of FK228 (2) against HDAC3/N-CoR2.

| Compound | H2O2 [mM] |

Enzyme activity [%] |

IC50 [µM] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.018 |

| 2 | 0.2 | 70.8 | 0.020 |

| 2 | 0.4 | 68.9 | 0.039 |

| 2 | 1.0 | 57.3 | 0.041 |

In vitro antiproliferative/cytotoxic activities of thailandepsin A (6) and thailandepsin B (7)

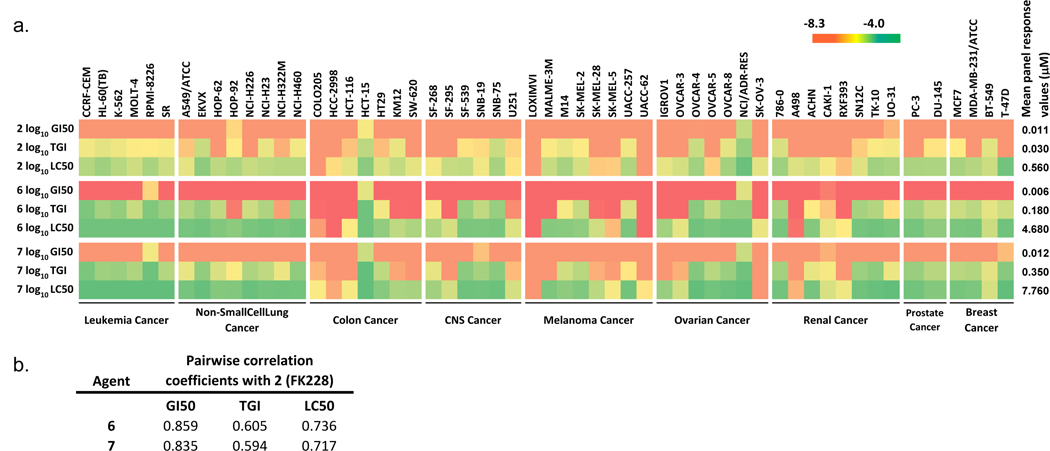

Compounds 6 and 7 were submitted to the US National Cancer Institute (NCI)’s Developmental Therapeutics Program (DTP) on August 12, 2009 for screening against the NCI-60 human cancer cell lines,28, 29 and were accepted by assigning entry numbers NSC D751510 and NSC D751511, respectively. Both compounds exhibited broad-spectrum antiproliferative activities similar to 2, with GI50 for over 90% of the tested cell lines at low nanomolar concentrations (Figure 3a). Differential activities towards specific cell lines were observed at the TGI and LC50 level, particularly for those derived from colon, melanoma and renal cancers, while leukemia cell lines were generally less sensitive. Matrix Compare analysis showed close correlation in antiproliferation profile between 6, 7 and 2, with Pearson correlation coefficient above 0.7 across the GI50 and LC50 levels (Figure 3b). Overall, 2 is slightly more potent at the TGI and LC50 levels in most cell lines, consistent with its slightly more potent in vitro HDAC inhibitory activity compared with 6 and 7 (Table 2). However, 6 is more potent than 2 or 7 in most cell lines at the GI50 level, and in certain cell lines at the TGI and LC50 levels (colon cancer HCC-2998, melanoma LOXIMVI and UACC-62, and renal cancers A498 and RXF393).

Figure 3. In vitro antiproliferative/cytotoxic activities of thailandepsins A (6) and B (7) in comparison with FK228 (2).

(a) Heat map representation of antiproliferative/cytotoxic activities50 of 6 and 7 across NCI-60 cell lines, with higher activity (lower index value) in warmer (darker if printed in black-white) color. GI50, growth-inhibition indicator; TGI, cytostatic effect indicator; LC50, cytotoxic effect indicator. Compound concentration in M was converted to log10 value for continuous color scale transformation. Mean panel response values were expressed in µM. (b) Statistics comparison of antiproliferation/cytotoxicity profile between 2, 6, and 7 across NCI-60 cell lines.

Further in vivo toxicities and efficacies of 6 and 7 are being evaluated in the mouse xenograft models. It remains interesting to see whether 6 and/or 7 could advance to clinical trials or how far they could proceed in the drug development pipeline. For the immediate future, 6 and 7 could be used as valuable epigenetic-intervening reagents for research on cancer or other human diseases.

During the preparation and journal review process43 of this article, Biggins et al. published a rapid communication of two compounds (named burkholdac A and burkholdac B) discovered from the same bacterial strain produced by the same gene cluster but using a different technical approach.16 Burkholdac B is identical to 6, while burkholdac A (8) and 7 are different minor products related to 6. Compound 7 is newly reported in this article.

Experimental Section

Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, and Reagents

Burkholderia thailandensis E264 (ATCC 700388), a Gram-negative β-proteobacterium strain originally isolated from a rice paddy in central Thailand,44 was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). This bacterial strain was cultured in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium or LB agar supplemented with 50 µg/ml apramycin (Am; this bacterial strain is naturally resistant to up to 200 µg/ml of Am) at 30–37°C overnight for seed culture and for genetic and molecular manipulations. Other general molecular biological procedures were as described in 21, 45 or in reagent supplier’s instruction.

RT-PCR detection of gene expression conditions

RT-PCR for the detection of gene expression conditions of tdpA and tdpJ was performed as described in SI.

Construction of a targeted gene-deletion mutant of B. thailandensis E264

A detailed description of the creation of a BthΔtdpAB mutant is described in SI.

Metabolic profiling by LC-MS

B. thailandensis E264 wild type (BthWT) strain and the BthΔtdpAB mutant strain were cultivated side by side in 50 ml of Medium 9 (M9 in Table S1) supplemented with 1% (w/v) of XAD16 resin and 1% (w/v) of Diaion HP-20 resin (Sigma-Aldrich) at 30°C for 3 days. A blank M9 was set up as medium reference. At the end of fermentation, resin and cell debris were collected and lyophilized to dryness, and the dry mass was extracted three times with 5 ml of ethyl acetate and pooled. A 100-µl aliquot of the ethyl acetate extract was analyzed by HPLC, using an Eclipse XBD C18 column (5 µm particle size, 4.6 × 250 mm; from Agilent) and a gradient elution from 20% to 100% of acetonitrile/water (v/v) in 30 min. Flow rate was set at 1 ml/min and UV signal was monitored at 200 nm. Peaks of interest from the BthWT sample were manually collected, dried and redissolved in acetonitrile. A 20-µl aliquot of such sample was re-analyzed by LC-MS (1100 series LC/MSD Trap mass spectrometer from Agilent). In addition, an equal volume of the sample was reduced with 50 mM DTT at room temperature and re-analyzed by LC-MS.

Purification and identification of thailandepsins A (6) and B (7)

A detailed description of natural product purification and identification is described in SI.

Fluorogenic assays of HDAC inhibition activities

Trypsin (from bovine pancreas), DMSO and Pluronic were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Germany). All reactions were performed in FB-188 buffer (15 mM Tris, 50 mM KH2PO4/K2HPO4, 250 mM NaCl, 250 µM EDTA, pH 8.0; from Roth, Germany) supplemented with 0.001% (v/v) Pluronic. The recombinant human HDACs were purchased from BPS Bioscience Inc. (San Diego, CA) and diluted in corresponding buffers. Compounds (2, 6 and 7) were dissolved in DMSO; half of each was then reduced by tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrocloride (TCEP) (CalBioChem, Germany) in a molar ratio of 1:1.5 for 20 min at ambient temperature prior to being assayed. The two-step fluorogenic assay was performed in 96-well half-area microplates (Greiner Bio-One, Germany) in a total volume of 100 µl according to Wegener et al.37 In principle, an ε-acetylated lysine substrate is first deacetylated by an HDAC in a reaction which is subsequently quenched by SAHA (kindly provided by Dr. A. Schwienhorst). Trypsin then is added to the reaction to cleave the detectable 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin (AMC; excitation at 390 nm, emission at 460 nm) off the deacetylated lysine. Fluorogenic signals were detected with a Polarstar fluorescence plate reader (BMG). Blank reactions showed that both DMSO and TCEP inhibit the investigated HDAC activities less than 3% at the highest compound concentration used. Therefore the influence of solvent or reducing agent on the enzyme activity could be neglected.

Boc-L-Lys(ε-acetyl)-AMC was a suitable substrate (20 µM working concentration) for HDAC1, HDAC2 and HDAC6. Boc-L-Lys(ε-trifluoroacetyl)-AMC was successfully used (at 20 µM working concentration) for assaying HDAC3, HDAC4, HDAC7, HDAC8 and HDAC9. Both substrates were purchased from Bachem (Weil am Rhein, Germany). Analysis of the data and calculation of the IC50 values was accomplished using a four-parameter logistic model protocol as previously described.46 For nonlinear fits the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm was applied.47, 48

The NCI-60 anticancer drug screen and COMPARE analysis

Details of the NCI-60 screening protocol are described online (http://www.dtp.nci.nih.gov/branches/btb/ivclsp.html). Screening experiments were conducted using five serial concentrations from 10−4 to 10−8 M of each compound. To compare the holistic antiproliferative activities between 2, 6 and 7, the mean values of the GI50, TGI or LC50 data across all NCI-60 cell lines were calculated from duplicated screening experiments performed for 6 and 7 in the present study, and five historically screening experiments that had been conducted for 2 by the NCI Developmental Therapeutics Program. Mean-graph signatures for all three agents were generated following the procedures described online (http://dtp.nci.nih.gov/docs/compare/COMPARE_methodology.html), and were used for a matrix COMPARE analysis.49

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We thank D. DeShazer (Walter Reed Army Medical Center) and H. Schweizer (Colorado State University) for providing vector tools, K. Nithipatikom (Medical College of Wisconsin) for assistance with HR-MS analysis, H. Foersterling (University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee) for assistance with NMR analysis, the NCI Developmental Therapeutics Program for conducting NCI-60 anticancer screening, M. Kunkel (NCI-DTP) for assistance with the COMPARE analysis of NCI-60 data, and D. Newman (NCI-DTP) for critical reading of this manuscript. This work was supported by a Research Growth Initiative Award from the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee and an NIH/NCI grant R01 CA152212 (both to Y.-Q.C). D.W. also acknowledges the NIH/NCI Intramural Research Program of the Center for Cancer Research for a fellowship support.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available

This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References and Notes

- 1.Jones PA, Baylin SB. Cell. 2007;128:683–692. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yoo CB, Jones PA. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006;5:37–50. doi: 10.1038/nrd1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolden JE, Peart MJ, Johnstone RW. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006;5:769–784. doi: 10.1038/nrd2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bots M, Johnstone RW. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009;15:3970–3977. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lane AA, Chabner BA. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;27:5459–5468. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schrump DS. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009;15:3947–3957. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.FDA. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2010;102:219. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mann BS, Johnson JR, Cohen MH, Justice R, Pazdur R. Oncologist. 2007;12:1247–1252. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-10-1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang H, Dymock BW. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2009;19:1727–1757. doi: 10.1517/13543770903393789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma X, Ezzeldin HH, Diasio RB. Drugs. 2009;69:1911–1934. doi: 10.2165/11315680-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okuhara M, Goto T, Hori Y, Fujita T, Ueda H, Shigeematsu N. 4,977. U.S. Patent. 1990;138

- 12.Ueda H, Nakajima H, Hori Y, Fujita T, Nishimura M, Goto T, Okuhara M. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 1994;47:301–310. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.47.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Masakuni O, Toshio G, Takashi F, Yasuhiro H, Hirotsugu U. 3,141. Japan Patent. 1991;296(A)

- 14.Masuoka Y, Nagai A, Shin-ya K, Furihata K, Nagai K, Suzuki K, Hayakawa Y, Seto H. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:41–44. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng Y-Q, Wang C. Histone deacetylase inhibitors and uses thereof. 20110060021. U.S. Patent Application. 2011

- 16.Biggins JB, Gleber CD, Brady SF. Org. Lett. 2011;13:1536–1539. doi: 10.1021/ol200225v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Furumai R, Matsuyama A, Kobashi N, Lee KH, Nishiyama M, Nakajima H, Tanaka A, Komatsu Y, Nishino N, Yoshida M, Horinouchi S. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4916–4921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fischbach MA, Walsh CT. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:3468–3496. doi: 10.1021/cr0503097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Finking R, Marahiel MA. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2004;58:453–488. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.58.030603.123615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walsh CT, Fischbach MA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:2469–2493. doi: 10.1021/ja909118a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheng Y-Q, Yang M, Matter AM. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007;73:3460–3469. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01751-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang C, Wesener SR, Zhang H, Cheng Y-Q. Chem. Biol. 2009;16:585–593. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newman DJ, Cragg GM. J. Nat. Prod. 2007;70:461–477. doi: 10.1021/np068054v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cragg GM, Grothaus PG, Newman DJ. Chem. Rev. 2009;109:3012–3043. doi: 10.1021/cr900019j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baltz RH. SIM News. 2005:186–196. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li MH, Ung PM, Zajkowski J, Garneau-Tsodikova S, Sherman DH. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:185. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corre C, Challis GL. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2009;26:977–986. doi: 10.1039/b713024b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shoemaker RH. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2006;6:813–823. doi: 10.1038/nrc1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Monga M, Sausville EA. Leukemia. 2002;16:520–526. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Potharla VY, Wesener SR, Cheng Y-Q. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011;77:1508–1511. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01512-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wesener SR, Potharla WY, Cheng Y-Q. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011;77:1501–1507. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01513-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim HS, Schell MA, Yu Y, Ulrich RL, Sarria SH, Nierman WC. BMC Genomics. 2005;6:174. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-6-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lambalot RH, Gehring AM, Flugel RS, Zuber P, LaCelle M, Marahiel MA, Reid R, Khosla C, Walsh CT. Chem. Biol. 1996;3:923–936. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(96)90181-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheng Y-Q, Tang GL, Shen B. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:3149–3154. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0537286100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choi KH, Schweizer HP. BMC Microbiol. 2005;5:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-5-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caboche S, Leclere V, Pupin M, Kucherov G, Jacques P. J. Bacteriol. 2010;192:5143–5150. doi: 10.1128/JB.00315-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wegener D, Hildmann C, Riester D, Schwienhorst A. Anal. Biochem. 2003;321:202–208. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(03)00426-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bertos NR, Wang AH, Yang XJ. Biochem. Cell. Biol. 2001;79:243–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao X, Sternsdorf T, Bolger TA, Evans RM, Yao T. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:8456–8464. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.19.8456-8464.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vega RB, Matsuda K, Oh J, Barbosa AC, Yang X, Meadows E, McAnally J, Pomajzl C, Shelton JM, Richardson JA, Karsenty G, Olson EN. Cell. 2004;119:555–566. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cadot B, Brunetti M, Coppari S, Fedeli S, de Rinaldis E, Dello Russo C, Gallinari P, De Francesco R, Steinkuhler C, Filocamo G. Cancer Res. 2009;69:6074–6082. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guenther MG, Barak O, Lazar MA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:6091–6101. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.18.6091-6101.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.A version of this paper had been submitted to another ACS journal for consideration on February 15, 2011, but after consideration it was decided that J. Nat. Prod. would be a more appropriate journal for publication of our results.

- 44.Brett PJ, DeShazer D, Woods DE. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1998;48(Pt 1):317–320. doi: 10.1099/00207713-48-1-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sambrook J, Russell DW. Molecular Cloning: a laboratory manual. 3rd ed. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Volund A. Biometrics. 1978;34:357–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marquardt DM. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 1963;11:431–441. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Levenberg K. Quarterly Appl. Math. 1944;2:164–168. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Paull KD, Shoemaker RH, Hodes L, Monks A, Scudiero DA, Rubinstein L, Plowman J, Boyd MR. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1989;81:1088–1092. doi: 10.1093/jnci/81.14.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Holbeck SL, Collins JM, Doroshow JH. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2010;9:1451–1460. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.