Abstract

β-thalassemia is a disease characterized by anemia and is associated with ineffective erythropoiesis and iron dysregulation resulting in iron overload. The peptide hormone hepcidin regulates iron metabolism, and insufficient hepcidin synthesis is responsible for iron overload in minimally transfused patients with this disease. Understanding the crosstalk between erythropoiesis and iron metabolism is an area of active investigation in which patients with and models of β-thalassemia have provided significant insight. The dependence of erythropoiesis on iron presupposes that iron demand for hemoglobin synthesis is involved in the regulation of iron metabolism. Major advances have been made in understanding iron availability for erythropoiesis and its dysregulation in β-thalassemia. In this review, we describe the clinical characteristics and current therapeutic standard in β-thalassemia, explore the definition of ineffective erythropoiesis, and discuss its role in hepcidin regulation. In preclinical experiments using interventions such as transferrin, hepcidin agonists, and JAK2 inhibitors, we provide evidence of potential new treatment alternatives that elucidate mechanisms by which expanded or ineffective erythropoiesis may regulate iron supply, distribution, and utilization in diseases such as β-thalassemia.

Introduction

Erythroid cells are highly dependent on iron for survival. In light of this dependence, mutual regulation of erythropoiesis and iron metabolism has been proposed. However, how iron demand for erythropoiesis is communicated to the iron regulatory machinery is incompletely understood. In the past few decades, significant progress has been made to advance our understanding of iron metabolism and its regulation. Furthermore, several diseases, β-thalassemia in particular, have provided glimpses of the crosstalk between iron regulation and erythropoiesis. By exploring ineffective erythropoiesis (IE) and its associated dysfunctional iron regulation, this disease may lay the foundation for more completely understanding, diagnosing, and treating patients with different forms of β-thalassemia as well as other anemias or iron overload–related disorders. In this review, we focus on the current state of knowledge on the regulation of iron metabolism and attempt to elucidate the interface between iron regulation and erythropoiesis with the use of evidence in part derived from animal models of β-thalassemia; despite being all nonhuman models of disease, their utility as in vivo tools for experimentation is worthy of note. We discuss potential ways in which this new knowledge can be translated into clinical application for patients with β-thalassemia.

β-thalassemia

Clinical characteristics

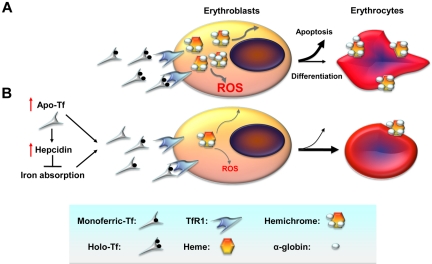

β-thalassemias are caused by mutations in the β-globin gene or its promoter, resulting in reduced or absent β-globin synthesis.1 Patients either homozygous or compound heterozygous for mutation in the β-globin gene present with a broad range of clinical severity; the disease course can be associated with severe transfusion dependency (β-thalassemia major; TM) or relatively less severe anemia (β-thalassemia intermedia, TI). In either clinical syndrome, relative excess of α-globin synthesis leads to formation of hemichromes and increased erythroid precursor apoptosis (Figure 1A), causing IE, extramedullary expansion, and splenomegaly.2 Together with shortened red blood cell (RBC) survival, these abnormalities result in moderate-to-severe anemia.2 Persons with TM require regular RBC transfusions to maintain adequate oxygen delivery to the tissues. Both transfusional iron loading and increased intestinal iron absorption3 contribute to iron overload that, if left untreated, accounts for most of the morbidity and mortality in this disease. Increased iron absorption leads to total saturation of Tf and appearance of non-transferrin bound iron that accumulates, causing parenchymal damage in several different tissues,4 particularly the heart and endocrine organs.

Figure 1.

Cellular mechanisms by which decreased iron uptake into erythroid precursors may promote survival and differentiation. (A) In β-thalassemia, a relative excess of α-globin synthesis leads to formation of hemichromes (α-globin/heme aggregates). Hemichromes are the primary cause of cellular toxicity in β-thalassemia because they precipitate and lodge on erythrocyte membranes, altering their structure. Furthermore, excess heme leads to the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROSs), which induce oxidative stress and cellular damage. In turn, this leads to IE by increasing apoptosis of erythroid precursors and reducing the number of erythrocytes produced as well as their survival in circulation. (B) On the basis of our data, we observe that administration of apo-Tf and increased hepcidin expression lead to decreased serum iron concentration and formation of fewer holo-Tf molecules. This reduces iron delivery to erythroid precursors, reducing heme synthesis and formation of hemichromes. In contrast, decreased iron intake limits hemichrome and ROS formation, ameliorating IE by reducing apoptosis, and improving erythrocyte survival in circulation. TfR1 indicates transferrin receptor 1.

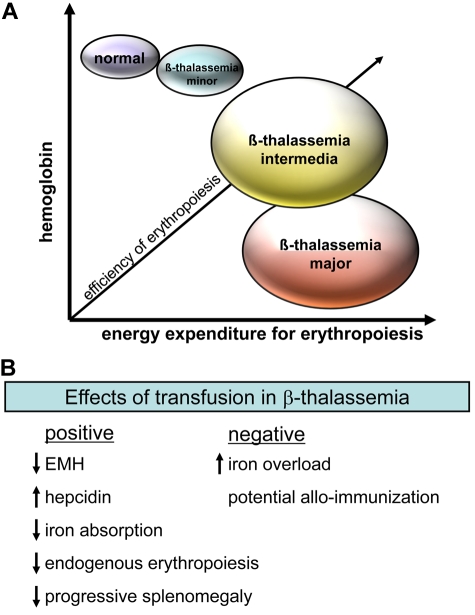

Patients with TI are usually transfusion independent with a clinical course intermediate in severity between TM and asymptomatic heterozygotes (Figure 2A). Coinherited genetic traits that influence the balance of α/β globin synthesis (eg, persistent production of Hb F and coinheritance of α-thalassemia) may ameliorate or exacerbate disease severity in β-thalassemia, resulting in some phenotypic variation. Children with TM usually have the disease diagnosed in infancy when they begin regular transfusions, and they require life-long chelation therapy, typically from the age of 4 years, to counteract the ill effects of consequent iron overload. Patients with TI may maintain Hb concentrations between 6 and 9 g/dL and may be asymptomatic or have manifestations of a hyperhemolytic phenotype with marked EMH, resulting in hepatosplenomegaly and skeletal abnormalities. Persons in this latter group develop more severe iron overload, and many become transfusion dependent in adulthood.5

Figure 2.

Efficiency of erythropoiesis and effect of transfusion in β-thalassemia. (A) Severity of disease depends on both the degree of anemia and the systemic energy expenditure for erythropoiesis. For example, persons for whom the production of 6 g of hemoglobin (Hb) requires expansion of extramedullary erythropoiesis (EMH) in the liver and spleen, resulting in splenomegaly and changes in bone architecture, and the systemic cost of erythropoiesis is high. Although such a person would probably have his or her disease classified as TI, the initiation of chronic transfusion may improve the quality of life in such cases. (B) Transfusion has a significant number of benefits in β-thalassemia, although the consequent iron overload and potential for alloimmunization are debilitating complications.

The clinical consequences of iron overload have been extensively described in TM (Figure 2B) with cardiac complications accounting for > 70% of deaths. The treatment of patients with TM has improved life expectancy in recent decades, with the institution of regular transfusion regimens, rigid compliance with iron chelation therapy, and options for multiple modality treatment.6 Despite this, myocardial disease remains the life-limiting complication of secondary iron overload7 (Figure 2B), almost always resulting from poor compliance with chelation therapy. Iron overload in minimally transfused patients with severe TI usually results from excess iron absorption from the gastrointestinal tract. This slower rate of iron accumulation results in a delay of clinically evident iron overload until the third decade of life.

Because survival and quality of life are better in patients with TI than in patients with TM,8 regular RBC transfusion in patients with TI is generally thought to add no benefit to patients who grow and thrive between the second and third year of life in their absence. Such persons may only require occasional transfusions when stress results in greater RBC destruction or inadequate RBC production. However, some patients with TI may produce some Hb but only with the expenditure of significantly increased physiologic effort, namely expanded yet ineffective erythropoiesis, resulting in significant bony changes and marked hepatosplenomegaly. In these persons, regular transfusion would result in suppression of endogenous erythropoiesis, with improved growth and development and fewer physical changes. The conundrum is finding markers that help clinicians assess and monitor the efficiency of erythropoiesis in any patient with β-thalassemia, allowing for an individualized transfusion regimen.

A complete review of the clinical manifestations of β-thalassemia syndromes is beyond the scope of this article and can be found elsewhere.9

Therapy: standard of care, special situations, and developing alternatives

A complete review of currently available therapeutic options is beyond the scope of this article and can be found on the Thalassemia International Federation Web site (http://www.thalassemia.org.cy) and other resources.

Standard therapy for TM: transfusion.

Transfusion is the main stay of therapy in β-thalassemia, typically initiated in the first 2 years of life in patients with TM. Transfusion in TM corrects anemia, suppresses EMH, inhibits increased intestinal iron absorption, and remains a relatively well-tolerated approach. Transfusions are given on demand when the patient is symptomatic (as is the practice in the developing world where the blood supply is short) or on a chronic transfusion protocol that is designed to maintain a pretransfusion Hb concentration of 9.5-10 g/dL and is typically administered every 2-3 weeks. Chronic or frequent transfusions require chelation to prevent iron overload. Complete reviews on this subject can be found elsewhere.10,11

Standard therapy for TI: transfusion.

No systematic evaluation of treatment in patients with TI has been presented to date, and there is a lack of clear guidelines and less standardized management of these patients (compared with treatment of TM). There are several reasons for this, primarily the marked patient phenotypic variability and the lack of objective clinical criteria for which to design a treatment regimen. Regular monitoring of EMH and spleen size is of primary importance in the decision of whether a patient requires transfusion because splenomegaly/hypersplenism may be the primary cause of worsening anemia. In such cases, splenectomy reestablishes equilibrium and enables patients with TI to remain transfusion independent. Although stable low Hb concentrations are usually found in patients with TI, situations of stress, such as severe infections or surgery, may result in more severe, often symptomatic, anemia requiring occasional RBC transfusion. Because most patients with TI have not received many transfusions, few require chelation therapy. Although the degree of iron overload is not usually severe, variability in the degree of increased intestinal iron absorption requires monitoring of the iron burden by magnetic resonance imaging (as in TM) to determine which patients require chelation.

Additional therapeutic options in special situations.

Splenectomy.

Splenomegaly usually develops in patients with β-thalassemia as a result of multiple transfusions, iron deposition, and some ineffective EMH (especially in patients with TI and inadequately transfused patients with TM). This usually results in hypersplenism, leading to an increase in transfusion requirement. It is for this indication that patients with TM usually undergo splenectomy by the age of 10 or 12 years. This is also considered in patients with TI to correct progressively worsening anemia before starting regular RBC transfusions. Polyvalent pneumococcal vaccine before splenectomy and rapid assessment and prophylactic antibiotics in asplenic patients with nonspecific febrile illness are strongly recommended. Furthermore, a recent study reported that patients with TI who had undergone splenectomy have a significantly higher rate of complications (eg, pulmonary hypertension, heart failure, thrombosis) relative to patients with TI not having undergone splenectomy.12,13 Finally, thrombotic complications were found to occur 4.4 times more frequently in patients with TI who had undergone splenectomy than patients with TM (P < .001).14 Taken together, splenectomy is temporarily effective in partially ameliorating anemia or delaying/lowering transfusion need in TI. Although it is preferred relative to other available options, potentially life-threatening complications may alter the risk-to-benefit assessment of splenectomy as a procedure of choice, especially as alternative therapeutic options become available.

Treatments that modulate the production of Hb F.

Induction of Hb F synthesis can reduce the inappropriately high α/β globin ratio and diminish the severity of β-thalassemia by reducing IE. Several agents, including 5-azacytidine, decytabine, and butyrate derivatives, have been used in clinical studies with less than encouraging outcomes, although increases in Hb F and total Hb levels were observed in patients with TM and with TI. The mechanisms of action of these agents are not yet defined, and their role in β-thalassemia therapy is still being explored in light of its acceptable toxicity profiles adding to their promise as therapeutic agents. Key genes (eg, BCL11 and cMYB) controlling fetal/adult globin switching have been identified and may ultimately serve as direct targets for small molecules that would increase Hb F levels in this patient population.15,16 The efficacy of hydroxyurea in TM or TI is unclear, although it is indicated for patients with TI to reduce extramedullary masses and to treat leg ulcers.17

Novel potential therapeutic alternatives.

Ideally, curative treatments for the symptomatic β-thalassemia syndromes is the goal of management. Currently, allogeneic stem cell transplantation is the only curative therapy that is available. More than 3000 patients, most with TM, have undergone this procedure, with generally good results. However, the lack of suitable stem cell donors and significant patient organ dysfunction make this modality inappropriate for some patients with β-thalassemia. Furthermore, β-globin gene transfer with the use of hematopoietic stem cells18 is in advanced stages of development with clinical trials soon to be under way. Preclinical studies that use lentiviral vector gene transfer in β-thalassemic mice19–21 show the potential of this technique to cure β-thalassemia and other forms of hemoglobinopathy and have led to the first successful treatment of a patient who, 3 years after treatment, is transfusion independent with one-third of myeloid lineage cells expressing vector-encoded β-globin.22

Recently, preclinical evidence of potentially new approaches to treating patients with TI and TM has been reported. The evidence for using Tf, hepcidin agonists, and JAK2 inhibitors is discussed later in this review.

Ineffective erythropoiesis

Important players involved in erythropoiesis

Normal erythropoiesis occurs in the BM where erythroid precursors differentiate and enucleate to produce reticulocytes and mature RBCs. Erythropoietin (EPO) is the master regulator of erythroid development and is mainly mediated by hypoxia-inducible factors that bind the EPO promoter at its hypoxia-response element, thus enhancing its transcription.23 EPO signals through its receptor (EPOR) in immature erythroid cells, and dimerization of EPO-EPOR complex induces phosphorylation and activation of the tyrosine kinase JAK2.24 In turn, the phosphorylated form of JAK2 activates STAT5,25 which modifies the expression of genes involved in proliferation, differentiation, and survival of erythroid precursors.26,27 Erythropoiesis requires the coordinated biosynthesis of heme and globin chains to produce Hb during the differentiation process. Proteins that control iron intake and heme biosynthesis are reviewed in “Coordination of erythroid iron homeostasis, heme metabolism, and globin synthesis.”

Difference between effective and ineffective erythropoiesis

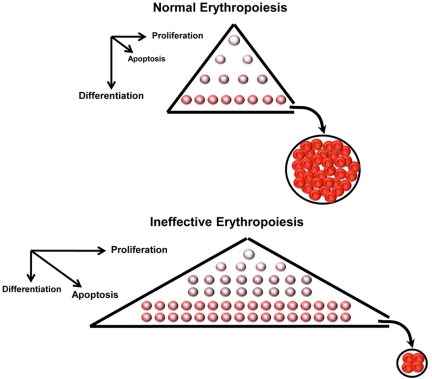

At steady state, the BM maintains a constant number of nucleated erythroid precursors required to produce enough enucleated RBCs to meet oxygen demand in tissues. Blood loss and hemolysis trigger stress erythropoiesis, resulting in increased EPO production, erythroid proliferation, and reticulocytosis to temporarily increase RBC production. In states of IE, erythroid precursors proliferate in greater numbers, but a larger fraction fails to mature (Figure 3). Despite the expanded pool of erythroid progenitors, only a limited number of RBCs is produced, many fewer than the same number of erythroid progenitors would generate under normal circumstances.

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of normal and ineffective erythropoiesis. In normal conditions, erythroblasts generate erythrocytes through a homeostatic balance between proliferation, differentiation, and cell death. In ineffective erythropoiesis, formation of toxic hemichromes leads to apoptosis and cell death of many erythroid precursors, limiting production of erythrocytes. Furthermore, on the basis of several observations (as discussed in the text), we postulate that in β-thalassemia erythroid precursors increase cell proliferation concurrently with reduced cell differentiation. This leads to a net increase in the number of erythroid precursors despite higher rates of apoptosis.

In β-thalassemia, IE is characterized by expansion, limited differentiation, and premature death of erythroid precursors28 (Figure 3), a process probably mediated by factors involved in cell cycle, iron intake, and heme synthesis.29 Anemia results in increased EPO levels, leading to erythroid expansion in BM, promoting homing and proliferation of erythroid precursors in the spleen and liver, and inducing EMH. The imbalance in the production of α- and β-globin chains leads to an excess of heme and α-globin elements accumulating as hemichromes. These are toxic aggregates that increase oxidative stress and cause cell death.28,30 Hemichromes also precipitate on RBC membranes, causing changes in membrane structure, inducing lipid peroxidation,31 and leading to the exposure of the anionic phospholipids that together result in premature RBC clearance from circulation.32

Mouse models of β-thalassemia

Compared with humans, mice harbor 2 different β-globin genes, named βminor and βmajor. The first mouse model of TI has been generated by deletion of the βmajor gene in homozygosity (Hbbth1/th1).33 A second model (Hbbth3/+) involves deletion of both the βminor and βmajor genes in heterozygosity.34,35 Adult Hbbth1/th1 and Hbbth3/+ mice exhibit a degree of disease severity (hepatosplenomegaly, anemia, aberrant erythrocyte morphology) comparable to that of patients with TI.

Available methods for the characterization of IE

Ferrokinetic studies were used to show IE in β-thalassemia > 60 years ago.36,37 Injection of 59Fe into healthy and anemic persons showed that patients with β-thalassemia had increased iron absorption, while the output of 59Fe in circulating RBCs was markedly reduced. Multiple ferrokinetic studies introduced the notion that erythroid cell death was responsible for IE in this disorder.36 Subsequent reports confirmed increased apoptosis of erythroid progenitors, indicating that β-thalassemic erythroid precursors undergo apoptosis at a rate that was 3-4 times normal.38

Studies in patients with β-thalassemia not receiving transfusions show that the rate of iron loading from the gastrointestinal tract is ∼ 3-10 times greater than normal and depends on the severity of the phenotype.4,39 Recent studies in mice suggest that more iron than is needed for making Hb is absorbed in β-thalassemia and that a large fraction of the iron absorbed is not used for erythropoiesis but is directly stored in the liver.40–43 All these observations predict that other factors contribute to IE in β-thalassemia. On the basis of this observation, the proliferation and differentiation of purified erythroid cells derived from animals affected by TI (Hbbth3/+) and TM (Hbbth3/th3) were investigated with the use of various modern assays.28,43 This analysis shows that cell cycle–promoting genes are up-regulated and that cell differentiation genes are decreased, indicating that the imbalance between immature erythroid precursors and RBCs is because of a combination of cell death and reduced cell differentiation in β-thalassemia.

Iron metabolism and regulation

Hepcidin and its regulation

Iron absorption and recycling are regulated by the peptide hormone hepcidin, the main regulator of body iron flows. Hepcidin exerts its function by binding to the only known iron export protein, ferroportin (FPN-1), found on all cells involved in iron metabolism; binding FPN-1 results in its internalization, degradation, and cessation of iron export.44

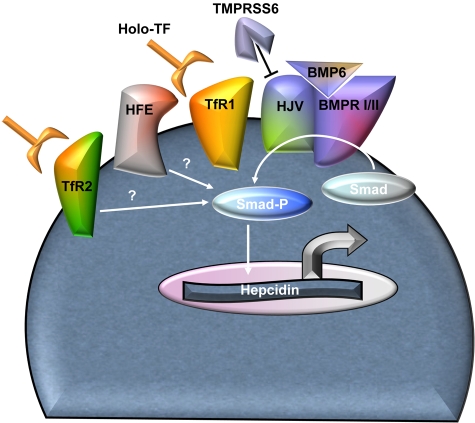

Regulation of hepcidin is influenced by iron, hypoxia, inflammation, and erythropoiesis, possibly through distinct mechanisms. In the recent past, major advances have been made in understanding the molecular mechanism of hepcidin regulation, and a complete review on the subject can be found elsewhere.45 In short, bone morphogenic protein (BMP) pathway plays a central role in hepcidin regulation by iron.46,47 When BMP6 and hemojuvelin (HJV) interact with BMP receptors type I/II, phosphorylation and activation of the SMAD complex results in increased hepcidin expression48 (Figure 4). In addition, holo-Tf regulates hepcidin expression through TfR2 and HFE. Holo-Tf binds both TfR1 and TfR2, although it has a stronger affinity for TfR1. In a proposed model, HFE associates with TfR1 under low iron conditions49 and is displaced when TfR1 binds holo-Tf.50,51 As serum iron and holo-Tf concentrations rise, the ratio of TfR2 to TfR1 expression increases. Together, this leads to TfR2/holo-Tf membrane stabilization52,53 and induces HFE/TfR2 binding and hepcidin expression. Whether this cascade is mediated by the association of HFE or TfR2 or both with the BMP6/HJV complex or by activation of yet known pathways has not been completely characterized. Thus, both TfR2 and HFE/TfR1 complex function as the main holo-Tf sensors,52,54,55 enabling fine-tuning of hepcidin regulation, probably potentiating the BMP signaling pathway as the concentration of holo-Tf increases in response to iron status (Figure 4). Mutations in many of these genes are central to the pathophysiology of hereditary hemochromatoses in which insufficient hepcidin expression is a common feature (reviewed elsewhere56).

Figure 4.

Homeostasis of hepcidin regulation. The schema of hepcidin regulation in hepatocytes as described in the text. The involved proteins enable nuanced regulation of hepcidin expression in light of hepcidin's central role in iron homeostasis. In β-thalassemia, one or multiple mechanisms involved in hepcidin stimulation are altered, resulting in hepcidin suppression relative to the degree expected from concurrent iron overload. The erythroid regulator probably has an effect through one or multiple mechanisms involved in hepcidin regulation. BMPR I/II indicates BMP receptors type I and II; Smad-P, phosphorylated Smad complex; HFE, hemochromatosis protein; and TMPRSS6, transmembrane serine protease matriptase-2.

Finally, although hepcidin expression is decreased as a consequence of iron deficiency, recent studies in both human subjects (with iron refractory iron deficiency anemia) as well as mice (mask phenotype) show that inappropriately high levels of hepcidin expression cause iron deficiency. Mask mice have microcytic anemia because of iron deficiency caused by decreased iron absorption from high hepcidin levels; positional cloning experiments show a splicing error in TMPRSS6.57 Similarly, patients with iron refractory iron deficiency anemia have a mutation in TMPRSS6, resulting in hypochromic microcytic anemia and elevated hepcidin concentrations.58–60 Additional studies suggest that TMPRSS6 normally acts to down-regulate hepcidin expression by cleaving membrane-bound HJV.60 This decreases the amount of membrane-bound HJV and leads to reduced hepcidin expression.61

Holo-transferrin, TfR1, and hepcidin regulation

Iron directed to the erythroid compartment is restricted to Tf-bound iron, and its relationship with TfR1 is a well-described ligand-receptor binding and uptake cascade.62 Tf takes up iron from duodenal enterocytes (when it is absorbed) and from macrophages (when iron is recycled from senescent RBCs). The amount of iron delivered to each erythroid precursor depends on the amount of monoferric- and holo-Tf found in circulation as well as the density of TfR1 on the cell surface. Typically, each erythroid precursor has more than a million TfR1s on its membrane because of its large iron requirement, greater than all other cell types.63 Regulation of TfR1 expression involves iron regulatory proteins (IRPs) that have a high affinity for iron response elements (IREs) present in the mRNA of TfR1 as well as other iron homeostasis-related genes.64

Iron uptake starts when holo-Tf binds TfR1. Under normal circumstances, the affinity of TfR1 for holo-Tf is greater than for monoferric-Tf. However, this greater affinity wanes as the iron supply is diminished.65 Monoferric-Tf is the predominant form of Tf in circulation when Tf saturation is lowered.66 Each molecule of monoferric-Tf delivers less iron to erythroid precursors than holo-Tf.65 This enables a greater number of erythroid precursors to receive a smaller portion of the iron pool to offset developing anemia and is consistent with a low mean cellular volume and mean corpuscular Hb (MCH). What controls this apportioning of iron to erythroid precursors is not completely understood, but the relation between decreased Tf concentration and the regulation of hepcidin expression has recently been further elucidated. In hypotransferrinemic (Trfhpx/hpx) mice, injections of purified human-Tf or serum containing mouse-Tf correct anemia and decrease parenchymal iron overload, providing necessary Tf-iron delivery to the erythron and restoring hepcidin expression.67 Suppression of erythropoiesis and resolution of the anemia after transfusion with washed RBCs (ie, Tf-depleted blood) into Trfhpx/hpx mice also results in increased hepcidin expression. Furthermore, hepcidin expression increases in myeloablated Trfhpx/hpx mice receiving concurrent administration of human-Tf or mouse serum containing-Tf. These observations suggest that (1) hepcidin suppression in Trfhpx/hpx mice results from Tf-restricted erythropoiesis and (2) Tf can stimulate hepcidin in an erythropoiesis-independent manner.67

Erythroid iron intake and the crosstalk between erythropoiesis and iron metabolism

Coordination of erythroid iron homeostasis, heme metabolism, and globin synthesis

Because of the elevated rate of Hb synthesis in erythroid cells and of the toxic nature of free heme, erythroid progenitors must efficiently regulate iron uptake and coordinate the production of all Hb components. Analysis of nonerythroid cells suggests that this is accomplished through the IRP/IRE system; depending on the localization of the IRE, association with an IRP serves 2 distinct functions. Binding to IREs located in the 5′-untranslated region (UTR) of mRNAs blocks initiation of translation by interfering with ribosome assembly, whereas association with IREs at the 3′-UTR stabilizes the mRNA. IREs in the 5′-UTR are seen in mRNAs coding FPN-1, ferritin (an iron storage protein), and aminolevulinic acid synthase 2 (an enzyme that catalyzes the first step of heme biosynthesis), all involved in decreasing the amount of labile cellular iron, whereas IREs in the 3′-UTR are present in mRNAs coding TfR1 (Figure 5) and divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT-1) involved in increasing cytosolic iron. With the use of erythroid cells (primary cells or cell lines) it has been shown that regulation of IRP2, the main IRP in these cells,68,69 is less dependent on iron than on EPO by the JAK2/STAT5 pathway.70 Synthesis of ferritin and aminolevulinic acid synthase 2 is also less responsive to iron levels.71 Moreover, DMT-1 and FPN-1 are mostly synthesized from mRNA sequences that do not contain IREs.72,73 However, the function of FPN-1, as well as FLVCR, a heme exporter,74 in erythropoiesis, is still incompletely characterized and understood, although they may serve to protect erythroid precursors from a deleterious excess of iron and heme. Finally, the second protein that binds holo-Tf, TfR2, is expressed in erythroid cells in a complex with EPOR75 and may represent an important player at the interface between iron and erythropoiesis (Figure 5). However, whether the association between TfR2 and EPOR modulates the synthesis of IRP2 and other iron-related genes or influences iron uptake in the erythron is incompletely understood.

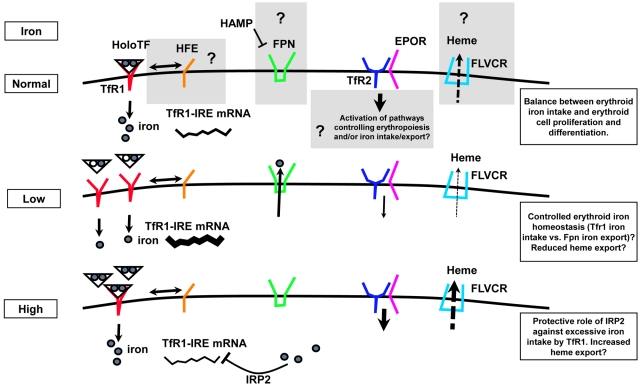

Figure 5.

Model of regulation of erythroid iron intake, cell proliferation, and differentiation. Recent findings indicate that iron-related proteins, previously characterized in the liver, are expressed in erythroid precursors. Although their function is largely uncharacterized in these cells, here we speculate on their potential function. In normal conditions, HFE has the potential to influence TfR1-mediated iron intake, whereas TfR2, binding EPOR, may modulate erythropoiesis, iron metabolism, or both. Under conditions of low iron intake, TfR1 mRNA is stabilized by IRP2 and iron intake increases. Under conditions of high Tf saturation, erythroid iron intake is probably modulated by loss of IRP2 activity, limiting TfR1 synthesis. FPN may export iron to avoid iron toxicity or to further control cellular iron content in normal or other uncharacterized altered physiologic conditions. Furthermore, excess of intracellular heme, potentially toxic, may be prevented by the heme exporter FLVCR (feline leukemia virus C receptor), both under conditions of normal and abnormal erythroid iron intake.

Proposed secreted “erythroid factor(s)” repress hepcidin expression

Prior experiments have shown that phlebotomy, EPO administration, and hemolysis result in decreased hepcidin expression.76–78 Ablation of erythropoiesis prevents hepcidin suppression in these conditions; this effect is independent of anemia or liver iron stores.77,79 These studies further show that demand of erythropoietic iron influences hepcidin expression to a greater degree than anemia or nonhematopoietic iron stores.

Several studies have shown that hepcidin expression is disproportionally low relative to the degree of iron overload in β-thalassemia40,41,80 and indicate that the proposed erythroid factor suppresses hepcidin synthesis.81 Furthermore, the “erythroid regulator” is probably a factor secreted either from immature and proliferating or dying erythroid precursors. If this factor is secreted by immature erythroid precursors, it would be present in all conditions in which erythroid precursor expansion occurs79,82 (eg, after recovery from phlebotomy and transient anemia in blood donors). Twisted gastrulation-1 (TWSG1) has been isolated from immature erythroid precursors in β-thalassemic mice.83 As a small secreted cysteine-rich protein able to influence BMPs signaling,84 the expression of TWSG1 is increased in β-thalassemic mice and represses hepcidin in vitro.83 However, whether this factor is present in other conditions and how efficiently TWSG1 represses hepcidin in physiologic conditions is still unclear.

If the proposed erythroid factor is secreted by dying erythroid precursors, it would be present only in conditions in which large numbers of erythroid precursors undergo apoptosis. Growth differentiation factor-15 (GDF15) has been isolated from the sera of patients with β-thalassemia and other persons exhibiting features of IE, such as myelodysplastic syndromes and congenital dyserythropoietic anemia type I and II, and an inverse correlation with hepcidin levels has been shown.85–87 GDF15 is a member of the TGF-β superfamily of proteins that are known to control cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis in numerous cell types. However, it is possible that in conditions such as β-thalassemia, multiple erythroid factors suppress hepcidin expression.88,89 The mechanisms of action of GDF15 and TWSG1 in repressing hepcidin expression remain undefined but are probably to alter the function of proteins that modulate hepcidin production.

Novel potential therapeutic options and what they show about erythroid regulation of hepcidin

Transferrin reverses ineffective erythropoiesis in β-thalassemic mice

Tf is the main serum iron transporter in all vertebrates; it takes up iron from duodenal enterocytes where iron is absorbed and from macrophages when iron is recycled from senescent RBCs and delivers it to cells by binding TfR1. We hypothesized that insufficient hepcidin secretion and maldistribution of iron in β-thalassemia may result from inadequate circulating Tf to deliver iron for erythropoiesis. This hypothesis is informed by preliminary experiments in Hbbth1/th1 mice that show low non-heme iron in the BM relative to control mice.42 High-dose iron dextran in these mice results in a dose-dependent increase in extramedullary erythropoiesis.39 This increased number of erythroid precursors in the liver and spleen results in more RBCs and more Hb but no improvement in IE.39 Exogenous iron does not trigger a medullary erythroid response and suggests that increased Tf concentration may be necessary to delivery sufficient iron to accommodate the degree of erythoid expansion observed in β-thalassemia without, however, amelioration of the underlined IE and erythroid expansion.

Chronic treatment with apo-Tf injections in Hbbth1/th mice results in increased Hb production, decreased reticulocytosis and serum EPO levels, reversal of splenomegaly, and elevated hepcidin expression.90 Apo-Tf injections reduce hemichrome formation (Figure 1B) and also change the proportion of erythroid precursors to more mature relative to immature precursors, lower the rates of apoptosis in mature erythroid precursors, and reduce the amount of extramedullary erythropoiesis in the liver and spleen in Hbbth1/th1 mice. These findings imply that exogenous apo-Tf restores more normal (less ineffective) erythropoiesis. How additional apo-Tf is able to improve erythropoiesis in Hbbth1/th1 mice is incompletely understood. Although the Hb concentration and the number of RBCs increase after apo-Tf injections, RBCs are smaller and contain less Hb. Similar phenotype-decreased mean cellular volume and MCH with normal Hb values because of increased number of RBCs is observed in TfR+/− mice91 and is reminiscent of iron-deficient erythropoiesis in persons treated with recombinant EPO.92 This “functional iron deficiency,” a term used to describe states of iron-restricted erythropoiesis induced by exogenous EPO, suggests that iron supply is sufficient or insufficient to meet the demands of erythropoiesis, depending on the number of erythroid precursors and may also apply to states of IE with expanded erythropoiesis and elevated endogenous EPO.93 In addition, iron restriction in erythroid precursors may be a compensatory mechanism in conditions with IE such as β-thalassemia in which a reduced cellular iron results in decreased heme synthesis and fewer hemichromes. We propose that expanded erythropoiesis observed in β-thalassemia is limited by the lack of compensatory increase in Tf concentration. In our experiments, the addition of exogenous apo-Tf results in decreased Tf saturation and probably a shift toward more monoferric-Tf molecules with more Tf molecules available to deliver smaller amounts of iron to more erythroid precursors, resulting in further decreased MCH and fewer hemichromes.

The observed response to Tf treatment of Hbbth1/th1and Trfhpx/hpx mice further suggests that IE and Tf-restricted erythropoiesis share many common characteristics. The finding of protoporphyrin in RBCs of patients with β-thalassemia, in whom Tf saturation is an ample 40%, provides evidence that this is the case.94 In fact, older literature estimated that the daily iron requirement in β-thalassemia may be as high as 150 mg, values that could make iron demand by the expanded erythron greater than its available supply95 and possibly trigger hepcidin suppression to stimulate an increase in iron absorption.

Hepcidin agonists or activators of hepcidin expression prevent iron overload and improve erythropoiesis in β-thalassemic mice

On the basis of previous observations, it is possible that in patients with β-thalassemia more iron is absorbed than required for erythropoiesis. Thus, decreasing dietary iron intake or hepcidin administration might prevent iron overload. In fact, Hbbth3/+ mice (another model of TI) avoid iron overload when placed on a low-iron diet or are engineered to overexpress a moderate level of hepcidin.43 Reversal of iron overload results in reduced erythroid iron intake, limiting the synthesis of heme and the formation of hemichromes and ROSs (Figure 1B).43 Because hemichromes and ROSs cause IE in β-thalassemia, iron restriction and decreased erythroid iron intake results in more effective erythropoiesis, normalizes RBC structure and lifespan, increases circulating Hb, and reverses splenomegaly.43,96 Thus, the use of hepcidin agonists or drugs that increase hepcidin expression decreases iron uptake from the diet,43 reduces iron overload, and improves erythropoiesis in TI.

In TM, repeated blood transfusions are the principal cause of iron overload. Despite iron overload, hepcidin concentrations are low; transfusion also suppresses endogenous erythropoiesis and, as a consequence, results in a transient increase in hepcidin.40,97,98 Although intestinal iron absorption contributes part of the total iron load in these patients, hepcidin therapy may be effective in conjunction with transfusion to prevent intestinal iron uptake when endogenous hepcidin falls.

Jak2 inhibitor improves IE, reverses splenomegaly, and lowers transfusion requirements in β-thalassemic mice

In β-thalassemia, steady-state EPO production is increased, resulting in a “physiologic” gain of function of JAK2. As mentioned previously, IE in β-thalassemic mice is characterized by erythroid expansion, limited differentiation, and premature death of erythroid precursors.28,43,96 The persistent phosphorylation of JAK2 leads to an increased number of surviving erythroid precursors in this disorder, contributing to the IE. Therefore, suppression of JAK2 activity may modulate IE. On the basis of this hypothesis, we used a JAK2 inhibitor for 10 days in Hbbth3/+ mice and demonstrate a reduction in splenomegaly (“nonsurgical splenectomy”).28 Patients with β-thalassemia may undergo splenectomy to reduce their transfusion requirements and to limit iron overload. However, splenectomy appears to predispose patients to thrombotic events.43,99,100 Avoiding the need for splenectomy in patients with β-thalassemia may reduce the escalation of the transfusion requirement and may prevent thrombosis in this disorder.13 We also demonstrate that JAK2 inhibitors in β-thalassemic mice decreased the number of cells expressing cell cycle–related genes and partially reversed the IE, ameliorating the ratio between erythroid precursors and enucleated RBCs.28,96 Thus, although a complete understanding of how JAK2 inhibitors achieve this effect is unavailable, modulation of cell cycle and differentiation are probably involved.

On the basis of this compelling preclinical data, we speculate that the administration of JAK2 inhibitors to patients with β-thalassemia who receive chronic transfusions would reverse splenomegaly,28 prevent escalating transfusion requirements, and possibly prevent or delay the need for surgical splenectomy. Finally, JAK2 inhibitors may also lead to decreased expression of TfR1 by acting on the JAK2/STAT5/IRP2 axis30,70,89 and therefore also reduce erythroid iron intake and formation of hemichromes, reversing the erythroid pathology observed in β-thalassemia.

Conclusion

β-thalassemia is a compelling model in which to evaluate mechanisms of the crosstalk between erythropoiesis and iron metabolism because it provides evidence of the proposed erythroid regulator of hepcidin. Decreased hepcidin expression in this condition of concurrent IE and iron overload indicates that the erythroid regulator plays a more substantial role in iron metabolism than the “stores regulator.”

Preclinical data in β-thalassemic mice show that normalizing RBC survival results in less serum EPO that decreases the reticulocyte count, the number of erythroid precursors, and EMH. Thus, it is plausible to expect that the erythroid regulator reflects iron availability relative to the number of erythroid precursors for which iron is apportioned. Despite multiple advances in our understanding of iron regulation over the course of the past decade, the detailed pathophysiologic abnormalities in β-thalassemia remain to be clarified.

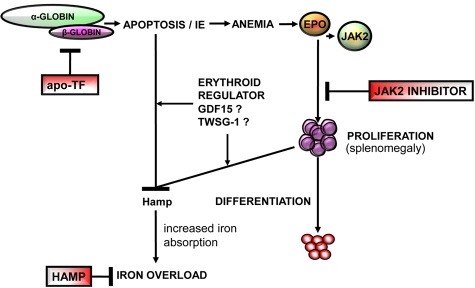

Recently developed novel methods aimed at reducing iron absorption and mechanisms of modifying iron delivery to the erythron have expanded our understanding of this important area of research. Although promising preclinical results cannot be confused with what is currently available for clinical application, apo-Tf, hepcidin agonists, and JAK2 inhibitors may ultimately lead to better management of iron overload, prevent splenomegaly and thrombosis, and reduce transfusion requirements in patients with β-thalassemia (Figure 6). Other developing therapeutic approaches, such as gene therapy, have had recent success.22 Although further experimentation is necessary to transform these preclinical and early clinical results into more standard therapy, a new era of intervention in β-thalassemia appears closer than it has ever been.

Figure 6.

Overview of the pathophysiology of β-thalassemia. This disease is a consequence of insufficient β-globin synthesis, leading to excess heme and α-globin, apoptosis, and anemia. Anemia results from a block of erythroid differentiation, although erythroid proliferation is increased, resulting in IE, hepcidin suppression, and iron overload. The novel therapies discussed in this review, apo-transferrin (apo-Tf), JAK2 inhibitors, and hepcidin agonists (HAMP), have the potential to affect different steps in the pathophysiology of this disease. Furthermore, studies in β-thalassemia might provide information to further understand the physiology of normal erythropoiesis.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Narla Mohandas, DSc, for his continued support and mentorship, and Sujit Sheth, MD, for editing this manuscript.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (1K08HL105682, Y.G.) and (5R01DK090554, S.R.), Cooley's Anemia Foundation (CAF, S.R.), the Children's Cancer and Blood Foundation (CCBF, S.R.), the American Portuguese Biomedical Fund (APBRF, USA)/Inova grant (S.R.), and the Venetian Association for the Fight Against Thalassemia (AVLT, S.R.).

Authorship

Contribution: Y.G. and S.R. wrote and edited the manuscript and designed figures.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Yelena Ginzburg, New York Blood Center, 310 East 67th St, Rm 1-38, New York, NY 10065; e-mail: yginzburg@nybloodcenter.org.

References

- 1.Weatherall DJ. Pathophysiology of thalassaemia. Baillieres Clin Haematol. 1998;11(1):127–146. doi: 10.1016/s0950-3536(98)80072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centis F, Tabellini L, Lucarelli G, et al. The importance of erythroid expansion in determining the extent of apoptosis in erythroid precursors in patients with beta-thalassemia major. Blood. 2000;96(10):3624–3629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olivieri NF. The beta-thalassemias. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(2):99–109. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907083410207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pippard MJ, Callender ST, Warner GT, Weatherall DJ. Iron absorption and loading in beta-thalassaemia intermedia. Lancet. 1979;2(8147):819–821. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(79)92175-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kazazian HH., Jr The thalassemia syndromes: molecular basis and prenatal diagnosis in 1990. Semin Hematol. 1990;27(3):209–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borgna-Pignatti C, Rugolotto S, De Stefano P, et al. Survival and complications in patients with thalassemia major treated with transfusion and deferoxamine. Haematologica. 2004;89(10):1187–1193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olivieri NF, Brittenham GM. Iron-chelating therapy and the treatment of thalassemia. Blood. 1997;89(3):739–761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Camaschella C, Cappellini MD. Thalassemia intermedia. Haematologica. 1995;80(1):58–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cao A, Galanello R. Beta-thalassemia. Genet Med. 2010;12(2):61–76. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181cd68ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neufeld EJ. Oral chelators deferasirox and deferiprone for transfusional iron overload in thalassemia major: new data, new questions. Blood. 2006;107(9):3436–3441. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-002394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cappellini MD, Porter J, El-Beshlawy A, et al. Tailoring iron chelation by iron intake and serum ferritin: the prospective EPIC study of deferasirox in 1744 patients with transfusion-dependent anemias. Haematologica. 2010;95(4):557–566. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.014696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taher AT, Musallam KM, Karimi M, et al. Overview on practices in thalassemia intermedia management aiming for lowering complication rates across a region of endemicity: the OPTIMAL CARE study. Blood. 2010;115(10):1886–1892. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-243154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cappellini MD, Motta I, Musallam KM, Taher AT. Redefining thalassemia as a hypercoagulable state. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1202:231–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taher A, Isma'eel H, Mehio G, et al. Prevalence of thromboembolic events among 8,860 patients with thalassaemia major and intermedia in the Mediterranean area and Iran. Thromb Haemost. 2006;96(4):488–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilber A, Nienhuis AW, Persons DA. Transcriptional regulation of fetal to adult hemoglobin switching: new therapeutic opportunities. Blood. 2011;117(15):3945–3953. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-316893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bauer DE, Orkin SH. Update on fetal hemoglobin gene regulation in hemoglobinopathies. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2011;23(1):1–8. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e3283420fd0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karimi M. Hydroxyurea in the management of thalassemia intermedia. Hemoglobin. 2009;33(Suppl 1):S177–S182. doi: 10.3109/03630260903351809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rivella S, Rachmilewitz E. Future alternative therapies for beta-thalassemia. Expert Rev Hematol. 2009;2(6):685–697. doi: 10.1586/ehm.09.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rivella S, May C, Chadburn A, Riviere I, Sadelain M. A novel murine model of Cooley anemia and its rescue by lentiviral-mediated human beta-globin gene transfer. Blood. 2003;101(8):2932–2939. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Breda L, Gambari R, Rivella S. Gene therapy in thalassemia and hemoglobinopathies. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2009;1(1):e2009008. doi: 10.4084/MJHID.2009.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Breda L, Kleinert DA, Casu C, et al. A preclinical approach for gene therapy of beta-thalassemia. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1202:134–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05594.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cavazzana-Calvo M, Payen E, Negre O, et al. Transfusion independence and HMGA2 activation after gene therapy of human beta-thalassaemia. Nature. 2010;467(7313):318–322. doi: 10.1038/nature09328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Semenza GL, Nejfelt MK, Chi SM, Antonarakis SE. Hypoxia-inducible nuclear factors bind to an enhancer element located 3′ to the human erythropoietin gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88(13):5680–5684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.13.5680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seubert N, Royer Y, Staerk J, et al. Active and inactive orientations of the transmembrane and cytosolic domains of the erythropoietin receptor dimer. Mol Cell. 2003;12(5):1239–1250. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00389-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wojchowski DM, Gregory RC, Miller CP, Pandit AK, Pircher TJ. Signal transduction in the erythropoietin receptor system. Exp Cell Res. 1999;253(1):143–156. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Socolovsky M, Fallon AE, Wang S, Brugnara C, Lodish HF. Fetal anemia and apoptosis of red cell progenitors in Stat5a-/-5b-/- mice: a direct role for Stat5 in Bcl-X(L) induction. Cell. 1999;98(2):181–191. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fang J, Menon M, Kapelle W, et al. EPO modulation of cell-cycle regulatory genes, and cell division, in primary bone marrow erythroblasts. Blood. 2007;110(7):2361–2370. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-063503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Libani IV, Guy EC, Melchiori L, et al. Decreased differentiation of erythroid cells exacerbates ineffective erythropoiesis in beta-thalassemia. Blood. 2008;112(3):875–885. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-126938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rivella S. Ineffective erythropoiesis and thalassemias. Curr Opin Hematol. 2009;16(3):87–194. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e32832990a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Melchiori L, Gardenghi S, Rivella S. Beta-thalassemia: HiJAKing ineffective erythropoiesis and iron overload. Adv Hematol. 2010;2010:938640. doi: 10.1155/2010/938640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cappellini MD, Tavazzi D, Duca L, et al. Metabolic indicators of oxidative stress correlate with haemichrome attachment to membrane, band 3 aggregation and erythrophagocytosis in beta-thalassaemia intermedia. Br J Haematol. 1999;104(3):504–512. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuypers FA, Yuan J, Lewis RA, et al. Membrane phospholipid asymmetry in human thalassemia. Blood. 1998;91(8):3044–3051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Skow LC, Burkhart BA, Johnson FM, et al. A mouse model for beta-thalassemia. Cell. 1983;34(3):1043–1052. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90562-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang B, Kirby S, Lewis J, Detloff PJ, Maeda N, Smithies O. A mouse model for beta 0-thalassemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(25):11608–11612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ciavatta DJ, Ryan TM, Farmer SC, Townes TM. Mouse model of human beta zero thalassemia: targeted deletion of the mouse beta maj- and beta min-globin genes in embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(20):9259–9263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Finch CA, Deubelbeiss K, Cook JD, et al. Ferrokinetics in man. Medicine (Baltimore) 1970;49(1):17–53. doi: 10.1097/00005792-197001000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cazzola M, Finch CA. Iron balance in thalassemia. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1989;309:93–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yuan J, Angelucci E, Lucarelli G, et al. Accelerated programmed cell death (apoptosis) in erythroid precursors of patients with severe beta-thalassemia (Cooley's anemia). Blood. 1993;82(2):374–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fiorelli G, Fargion S, Piperno A, Battafarano N, Cappellini MD. Iron metabolism in thalassemia intermedia. Haematologica. 1990;75(Suppl 5):89–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Origa R, Galanello R, Ganz T, et al. Liver iron concentrations and urinary hepcidin in beta-thalassemia. Haematologica. 2007;92(5):583–588. doi: 10.3324/haematol.10842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gardenghi S, Marongiu MF, Ramos P, et al. Ineffective erythropoiesis in beta-thalassemia is characterized by increased iron absorption mediated by down-regulation of hepcidin and up-regulation of ferroportin. Blood. 2007;109(11):5027–5035. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-048868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ginzburg YZ, Rybicki AC, Suzuka SM, et al. Exogenous iron increases hemoglobin in beta-thalassemic mice. Exp Hematol. 2009;37(2):172–183. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gardenghi S, Ramos P, Marongiu MF, et al. Hepcidin as a therapeutic tool to limit iron overload and improve anemia in beta-thalassemic mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(12):4466–4477. doi: 10.1172/JCI41717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nemeth E, Tuttle MS, Powelson J, et al. Hepcidin regulates cellular iron efflux by binding to ferroportin and inducing its internalization. Science. 2004;306(5704):2090–2093. doi: 10.1126/science.1104742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ganz T, Nemeth E. Hepcidin and disorders of iron metabolism. Annu Rev Med. 2011;62:347–360. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-050109-142444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Truksa J, Peng H, Lee P, Beutler E. Bone morphogenetic proteins 2, 4, and 9 stimulate murine hepcidin 1 expression independently of Hfe, transferrin receptor 2 (Tfr2), and IL-6. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(27):10289–10293. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603124103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Babitt JL, Huang FW, Wrighting DM, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein signaling by hemojuvelin regulates hepcidin expression. Nat Genet. 2006;38(5):531–539. doi: 10.1038/ng1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang RH, Li C, Xu X, et al. A role of SMAD4 in iron metabolism through the positive regulation of hepcidin expression. Cell Metab. 2005;2(6):399–409. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Feder JN, Penny DM, Irrinki A, et al. The hemochromatosis gene product complexes with the transferrin receptor and lowers its affinity for ligand binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(4):1472–1477. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lebron JA, Bennett MJ, Vaughn DE, et al. Crystal structure of the hemochromatosis protein HFE and characterization of its interaction with transferrin receptor. Cell. 1998;93(1):111–123. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81151-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Giannetti AM, Bjorkman PJ. HFE and transferrin directly compete for transferrin receptor in solution and at the cell surface. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(24):25866–25875. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401467200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Robb A, Wessling-Resnick M. Regulation of transferrin receptor 2 protein levels by transferrin. Blood. 2004;104(13):4294–4299. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Johnson MB, Enns CA. Diferric transferrin regulates transferrin receptor 2 protein stability. Blood. 2004;104(13):4287–4293. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Goswami T, Andrews NC. Hereditary hemochromatosis protein, HFE, interaction with transferrin receptor 2 suggests a molecular mechanism for mammalian iron sensing. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(39):28494–28498. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600197200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schmidt PJ, Toran PT, Giannetti AM, Bjorkman PJ, Andrews NC. The transferrin receptor modulates Hfe-dependent regulation of hepcidin expression. Cell Metab. 2008;7(3):205–214. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li H, Ginzburg YZ. Crosstalk between iron metabolism and erythropoiesis. Adv Hematol. 2010;2010:605435. doi: 10.1155/2010/605435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Du X, She E, Gelbart T, et al. The serine protease TMPRSS6 is required to sense iron deficiency. Science. 2008;320(5879):1088–1092. doi: 10.1126/science.1157121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Finberg KE, Heeney MM, Campagna DR, et al. Mutations in TMPRSS6 cause iron-refractory iron deficiency anemia (IRIDA). Nat Genet. 2008;40(5):569–571. doi: 10.1038/ng.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Melis MA, Cau M, Congiu R, et al. A mutation in the TMPRSS6 gene, encoding a transmembrane serine protease that suppresses hepcidin production, in familial iron deficiency anemia refractory to oral iron. Haematologica. 2008;93(10):1473–1479. doi: 10.3324/haematol.13342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Silvestri L, Pagani A, Nai A, De Domenico I, Kaplan J, Camaschella C. The serine protease matriptase-2 (TMPRSS6) inhibits hepcidin activation by cleaving membrane hemojuvelin. Cell Metab. 2008;8(6):502–511. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Babitt JL, Huang FW, Xia Y, Sidis Y, Andrews NC, Lin HY. Modulation of bone morphogenetic protein signaling in vivo regulates systemic iron balance. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(7):1933–1939. doi: 10.1172/JCI31342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Andrews NC. Disorders of iron metabolism. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(26):1986–1995. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912233412607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ponka P, Beaumont C, Richardson DR. Function and regulation of transferrin and ferritin. Semin Hematol. 1998;35(1):35–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rouault TA. The role of iron regulatory proteins in mammalian iron homeostasis and disease. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2(8):406–414. doi: 10.1038/nchembio807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Huebers HA, Csiba E, Huebers E, Finch CA. Competitive advantage of diferric transferrin in delivering iron to reticulocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80(1):300–304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.1.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Huebers HA, Josephson B, Huebers E, Csiba E, Finch CA. Occupancy of the iron binding sites of human transferrin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81(14):4326–4330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.14.4326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bartnikas TB, Andrews NC, Fleming MD. Transferrin is a major determinant of hepcidin expression in hypotransferrinemic mice. Blood. 2011;117(2):630–637. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-287359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Galy B, Ferring D, Minana B, et al. Altered body iron distribution and microcytosis in mice deficient in iron regulatory protein 2 (IRP2). Blood. 2005;106(7):2580–2589. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cooperman SS, Meyron-Holtz EG, Olivierre-Wilson H, Ghosh MC, McConnell JP, Rouault TA. Microcytic anemia, erythropoietic protoporphyria, and neurodegeneration in mice with targeted deletion of iron-regulatory protein 2. Blood. 2005;106(3):1084–1091. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kerenyi MA, Grebien F, Gehart H, et al. Stat5 regulates cellular iron uptake of erythroid cells via IRP-2 and TfR-1. Blood. 2008;112(9):3878–3888. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-138339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schranzhofer M, Schifrer M, Cabrera JA, et al. Remodeling the regulation of iron metabolism during erythroid differentiation to ensure efficient heme biosynthesis. Blood. 2006;107(10):4159–4167. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Canonne-Hergaux F, Zhang AS, Ponka P, Gros P. Characterization of the iron transporter DMT1 (NRAMP2/DCT1) in red blood cells of normal and anemic mk/mk mice. Blood. 2001;98(13):3823–3830. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.13.3823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang DL, Hughes RM, Ollivierre-Wilson H, Ghosh MC, Rouault TA. A ferroportin transcript that lacks an iron-responsive element enables duodenal and erythroid precursor cells to evade translational repression. Cell Metab. 2009;9(5):461–473. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Keel SB, Doty RT, Yang Z, et al. A heme export protein is required for red blood cell differentiation and iron homeostasis. Science. 2008;319(5864):825–828. doi: 10.1126/science.1151133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Forejtnikova H, Vieillevoye M, Zermati Y, et al. Transferrin receptor 2 is a component of the erythropoietin receptor complex and is required for efficient erythropoiesis. Blood. 2010;116(24):5357–5367. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-281360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nicolas G, Viatte L, Bennoun M, Beaumont C, Kahn A, Vaulont S. Hepcidin, a new iron regulatory peptide. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2002;29(3):327–335. doi: 10.1006/bcmd.2002.0573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vokurka M, Krijt J, Sulc K, Necas E. Hepcidin mRNA levels in mouse liver respond to inhibition of erythropoiesis. Physiol Res. 2006;55(6):667–674. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.930841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pinto JP, Ribeiro S, Pontes H, et al. Erythropoietin mediates hepcidin expression in hepatocytes through EPOR signaling and regulation of C/EBPalpha. Blood. 2008;111(12):5727–5733. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-106195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pak M, Lopez MA, Gabayan V, Ganz T, Rivera S. Suppression of hepcidin during anemia requires erythropoietic activity. Blood. 2006;108(12):3730–3735. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-028787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kattamis A, Papassotiriou I, Palaiologou D, et al. The effects of erythropoetic activity and iron burden on hepcidin expression in patients with thalassemia major. Haematologica. 2006;91(6):809–812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Weizer O, Adamsky K, Breda L, et al. Hepcidin expression in cultured liver cells responds differently to iron overloaded sera derived from patients with thalassemia and hemochromatosis [abstract]. Blood. 2004;104(11) Abstract 3196. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Finch C. Regulators of iron balance in humans. Blood. 1994;84(6):1697–1702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tanno T, Porayette P, Sripichai O, et al. Identification of TWSG1 as a second novel erythroid regulator of hepcidin expression in murine and human cells. Blood. 2009;114(1):181–186. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-195503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Vilmos P, Gaudenz K, Hegedus Z, Marsh JL. The Twisted gastrulation family of proteins, together with the IGFBP and CCN families, comprise the TIC superfamily of cysteine rich secreted factors. Mol Pathol. 2001;54(5):317–323. doi: 10.1136/mp.54.5.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tamary H, Shalev H, Perez-Avraham G, et al. Elevated growth differentiation factor 15 expression in patients with congenital dyserythropoietic anemia type I. Blood. 2008;112(13):5241–5244. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-165738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ramirez JM, Schaad O, Durual S, et al. Growth differentiation factor 15 production is necessary for normal erythroid differentiation and is increased in refractory anaemia with ring-sideroblasts. Br J Haematol. 2009;144(2):251–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Casanovas G, Swinkels DW, Altamura S, et al. Growth differentiation factor 15 in patients with congenital dyserythropoietic anaemia (CDA) type II [published online ahead of print April 8, 2011]. J Mol Med. doi: 10.1007/s00109-011-0751-5. doi: 10.1007/s00109-011-0751-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ramos P, Melchiori L, Gardenghi S, et al. Iron metabolism and ineffective erythropoiesis in beta-thalassemia mouse models. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1202:24–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05596.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rivella S, Nemeth E, Miller JL. Crosstalk between erythropoiesis and iron metabolism. Adv Hematol. 2010;2010:317095. doi: 10.1155/2010/317095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Li H, Rybicki AC, Suzuka SM, et al. Transferrin therapy ameliorates disease in beta-thalassemic mice. Nat Med. 2010;16(2):177–182. doi: 10.1038/nm.2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Levy JE, Jin O, Fujiwara Y, Kuo F, Andrews NC. Transferrin receptor is necessary for development of erythrocytes and the nervous system. Nat Genet. 1999;21(4):396–399. doi: 10.1038/7727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Brugnara C, Colella GM, Cremins J, et al. Effects of subcutaneous recombinant human erythropoietin in normal subjects: development of decreased reticulocyte hemoglobin content and iron-deficient erythropoiesis. J Lab Clin Med. 1994;123(5):660–667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cavill I, Macdougall IC. Functional iron deficiency. Blood. 1993;82(4):1377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Pootrakul P, Wattanasaree J, Anuwatanakulchai M, Wasi P. Increased red blood cell protoporphyrin in thalassemia: a result of relative iron deficiency. Am J Clin Pathol. 1984;82(3):289–293. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/82.3.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Beguin Y, Stray SM, Cazzola M, Huebers HA, Finch CA. Ferrokinetic measurement of erythropoiesis. Acta Haematol. 1988;79(3):121–126. doi: 10.1159/000205743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gardenghi S, Grady RW, Rivella S. Anemia, ineffective erythropoiesis, and hepcidin: interacting factors in abnormal iron metabolism leading to iron overload in beta-thalassemia. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2010;24(6):1089–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Tanno T, Bhanu NV, Oneal PA, et al. High levels of GDF15 in thalassemia suppress expression of the iron regulatory protein hepcidin. Nat Med. 2007;13(9):1096–1101. doi: 10.1038/nm1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kearney SL, Nemeth E, Neufeld EJ, et al. Urinary hepcidin in congenital chronic anemias. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48(1):57–63. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Eldor A, Rachmilewitz EA. The hypercoagulable state in thalassemia. Blood. 2002;99(1):36–43. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Taher AT, Otrock ZK, Uthman I, Cappellini MD. Thalassemia and hypercoagulability. Blood Rev. 2008;22(5):283–292. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]