Abstract

OBJECTIVES

To determine the incidence of fecal incontinence (FI) in community-dwelling older adults and identify risk factors associated with incident FI.

DESIGN

Planned secondary analysis of a longitudinal, population-based cohort study.

SETTING

Three rural and two urban Alabama counties (in-home assessments 2000–2005).

PARTICIPANTS

Stratified random sample of 1,000 Medicare beneficiaries: 25% African-American men, 25% white men, 25% African-American women, 25% white women, aged 65 and older. Eligible participants for this analysis were continent at baseline and community-dwelling 4 years later (n =557).

MEASUREMENTS

FI was defined as any loss of control of bowels occurring during the previous year. Independent variables were sociodemographics, Charlson comorbidity counts, self-reported bowel symptoms (chronic diarrhea and constipation), depression, and body mass index (BMI). Multivariable logistic regression models were constructed using incident FI as the dependent variable.

RESULTS

The incidence rate of FI at 4 years was 17% (95% confidence interval (CI) =13.7–20.1), with 6% developing FI at least monthly (95% CI =4.0–8.3). White women were more likely to have incident FI (22%) than African-American women (13%, P =.04); no racial differences were observed in men. Controlling for age, comorbidity count, and BMI, significant independent risk factors for incident FI in women were white race, depression, chronic diarrhea, and urinary incontinence (UI). UI was the only significant risk factor for incident FI in men.

CONCLUSION

The occurrence of new FI is common in men and women aged 65 and older, with a 17% incidence rate over 4 years. FI and UI may share common pathophysiologic mechanisms and need regular assessment in older adults.

Keywords: fecal incontinence, incidence, urinary incontinence, African Americans, gender, functional bowel disorders, epidemiology

Fecal incontinence (FI), commonly defined as the involuntary loss of liquid or solid feces or mucus, is a distressing disorder with a negative effect on quality of life.1,2 Recent data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) from 2005/06 suggest that the U.S. prevalence of FI in community-dwelling adults is 8.3% to 15.3% in adults aged 70 and older.3 These recent NHANES data, based on a sample representative of the U.S. population in terms of age distribution and racial and ethnic diversity, compares with prior estimates of FI prevalence that varied from 2% to 24%.2,4–9

A paucity of data exists for incident FI estimates in community-dwelling populations,10 although there is incidence data for specific cohorts such as postpartum women,11 nursing home residents,12 and stroke survivors.13 Risk factors associated with FI from cross-sectional studies vary in the literature. Epidemiological studies of men and women have shown that FI often exists with other comorbid disorders, pelvic floor disorders, and bowel-related symptoms, such as loose or watery stools and fecal urgency.6–9,14–17 The objectives of this study were to provide estimates of FI incidence in older, community-dwelling adults and to describe risk factors associated with incident FI over a 4-year period as part of a population-based longitudinal cohort study.

METHODS

The University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) Study of Aging initially enrolled 1,000 participants from November 1999 to February 2001 to evaluate mobility in older adults. Details of the background, study design, and recruitment have been previously published.18 In brief, participants were recruited from five counties in west-central Alabama from Medicare beneficiary lists stratified according to sex, race, and urban versus rural settings. To examine differences between African Americans and whites, men and women, and urban and rural residence, the study sample was balanced to represent these groups equally. Thus, the sample included 25% African-American women, 25% African-American men, 25% white women, and 25% white men; within each stratum, participants were selected to be 50% rural and 50% urban. The UAB institutional review board approved the study. All participants provided written informed consent.

The 1,000 initial participants were followed with telephone assessments at 6-month intervals and had a second in-home assessment at 4 years. Participants who were continent of stool at the baseline assessment, remained in the community, and completed a follow-up in-home assessment 4 years later (2004/05) were eligible for this analysis.

During baseline in-home assessments, trained interviewers used a structured questionnaire and asked participants about sociodemographic factors, medical conditions, and activities of daily living (ADLs). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated from weight and height (kg/m2) measurements obtained during the assessment. ADL questions included difficulty with bathing or showering, dressing and undressing, eating, and transferring out of bed or chair and specifically excluded incontinence or toileting.19 ADL scores ranged from 0 to 4, reflecting the number of activities participants reported having any difficulty performing; thus, a score of 4 reflected the highest level of ADL difficulty. Depressive symptoms were assessed according to the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale, on which a score of 5 or greater is used to indicate a positive screen for depressive symptoms.20 Mental status was assessed using the Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE).21 On the MMSE, higher scores represent better mental status, and a score of 23 or less indicates impaired cognition. A co-morbidity count was calculated based on the number of medical conditions included in the Charlson Comorbidity Index that were present, without regard to the severity of the conditions.22 Respondents were asked whether a physician had told them that they had specific medical conditions. The conditions assessed were congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction, valvular heart disease, peripheral arterial disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, kidney failure, liver disease, nonskin cancer, neurological disease, and gastrointestinal disease. A condition was validated if the participant reported taking a medication for the disease or condition, if the primary physician returned a questionnaire indicating that the participant had the condition, or if a hospital discharge summary for a hospitalization in the previous 3 years listed the condition. The comorbidity count ranged from 0 to 12, with higher numbers representing more comorbidities.

Women were asked additional questions about parturition factors, hysterectomy, and use of hormone therapy (including prior and current use). Men were asked additional questions about prostate problems including prostate cancer, benign prostatic hypertrophy or enlarged prostate, and prostatitis. The use of alpha adrenergic blockers was also examined as a potential risk factor in men. Sex-specific information was also verified as above.

In addition to the interview questions, physical performance was assessed using the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB), which included time to walk 9 feet, time to stand up from a firm seat five times with arms folded across the chest, and balance, evaluated according to ability to stand for 10 seconds first with feet together, then semitandem (side of heel of one foot touching the big toe of the other foot), and then tandem (heel of one foot directly in front of and touching the toes of the other foot).23 For each task, scores ranged from 0 to 4, with 4 indicating the best performance. A composite score (0–12) was obtained by summing scores from the individual tasks.

As part of a planned secondary analysis, FI was assessed using the same question at baseline and again at 4 years during the in-home assessments: “In the past year, have you had any loss of control of your bowels, even a small amount that stains or slightly soils your underwear?” At each time, participants reporting any loss of control of bowels in the past year were defined as having FI. Additional questions addressed FI frequency with the following response options: daily, one or more times a week, one or more times a month, and less than one time a month. Participants with a positive response to any loss of control of bowels and a positive response to one or more times a month were defined as having monthly FI. In addition to FI, participants responded to questions on the presence or absence of constipation and chronic diarrhea. Participants were not asked about FI at any other times during the longitudinal study period.

Urinary incontinence (UI) was ascertained using the following questions: “Have you ever leaked even a small amount of urine?” and “How often does this leaking occur?” Participants who reported that they had urine leakage at least monthly were considered to have UI.

Potential risk factors for FI were identified from the baseline data and analyzed separately for men and women. Univariate analyses were conducted to evaluate which factors were correlated with incident FI, using chi-square analyses for categorical variables and analysis of variance for continuous variables. Given the small number of participants with incident FI, a limited number of variables (P≤.05) were entered into a multivariable forward stepwise logistic regression with separate models for comparison of FI frequency. Any FI and monthly FI were entered into separate models according to sex as dependent variables. Variables that were correlated were entered separately while retaining age, BMI, and the comorbidity count. Given that age, BMI, and comorbidity count have been reported as risk factors for FI in other cross-sectional studies, these variables were retained in the final multivariable models for any and monthly FI.3,6–9 The resulting models were evaluated for goodness of fit. STATA 8.2 was used for statistical analyses (Stata Corp., College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Study Sample

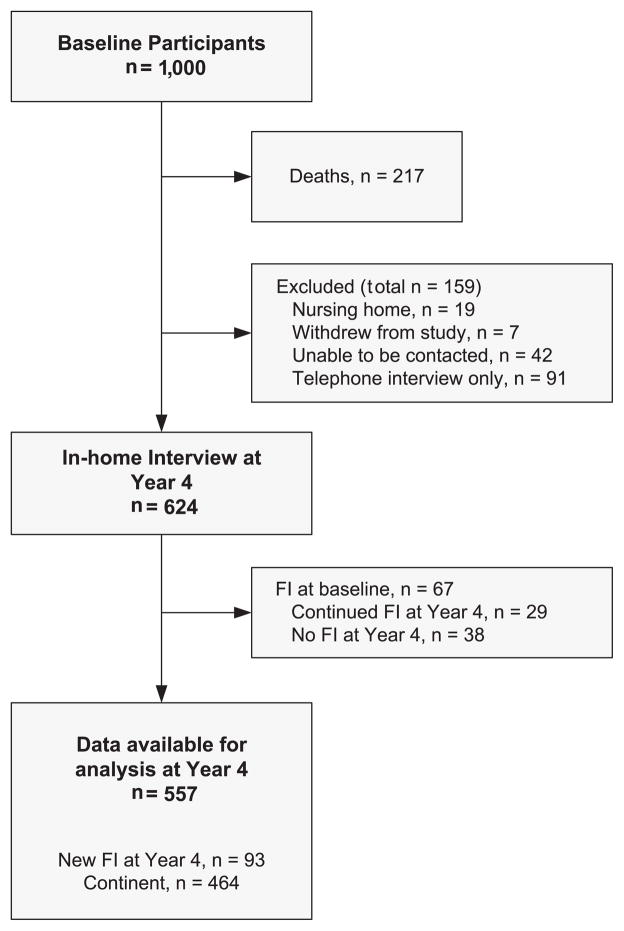

Of the 1,000 participants of the UAB Study of Aging, 217 had died, and 159 were not available for in-home assessment at Year 4 (Figure 1), leaving 624 participants with data on FI at baseline and at 4 years, a response rate of 80%. Overall, 22% of the baseline participants were dead at 4 years (77 women and 140 men, P<.001). Participants who were dead or missing were older at baseline than those with 4-year data on FI (77 vs 74, P<.001) but had no differences in race, baseline FI, or comorbidity counts. Participants who were dead or missing at 4 years were not more likely to have had higher rates of baseline FI than those alive at 4 years (11% vs 14%, P =.10). Only the 557 (297 women and 260 men) who were continent at baseline were included in the analysis of incident FI.

Figure 1.

Participants in the University of Alabama at Birmingham Study of Aging from baseline to 4 years with data on fecal incontinence (FI).

Demographics

The characteristics of the 557 participants according to continence status are shown in Table 1. Mean age was 77.7 ± 5.5 (range 69–89).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Differences Between Women and Men with and without Incident Fecal Incontinence (FI)

| Variable | Women, n =297

|

Men, n =260

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continent n =245 | Incident FI n =52 | P-Value | Continent n =219 | Incident FI n =41 | P-Value | |

| Age, mean ± standard deviation | 78 ± 6 | 78 ± 6 | .52 | 77 ± 6 | 77 ± 6 | .68 |

|

| ||||||

| Race or ethnicity, n (%)

| ||||||

| African American | 124 (51) | 18 (35) | .04 | 108 (49) | 20 (51) | .95 |

|

| ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 121 (49) | 34 (65) | 111 (51) | 21 (49) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Living alone, n (%) | 89 (36) | 23 (44) | .29 | 35 (16) | 11 (27) | .10 |

|

| ||||||

| Education ≥13 years, n (%) | 76 (31) | 12 (23) | .10 | 70 (32) | 17 (41) | .67 |

|

| ||||||

| Rural residence, n (%) | 119 (49) | 28 (54) | .49 | 108 (49) | 52 (34) | .07 |

Incidence of FI

The incidence rate of FI was 17% (95% confidence interval (CI) =13.7–20.1) at 4 years. No statistically significant differences in incident FI were seen in women (18%) and men (16%) (P =.58). The majority of participants with incident FI had FI episodes less than one time per month (64/93; 69%). Monthly or greater FI incidence was 6.3% (95% CI =4.0–8.3), without any significant sex differences (P =.19). The remission rate for participants with any FI during the previous year over the 4 years was 57% (38 of the 67 who were incontinent at baseline).

Risk Factors for Incident FI

For women without FI at baseline, factors predictive of any FI after 4 years according to multivariable analysis (P<.05) were non-Hispanic white ethnicity, Geriatric Depression Scale score greater than 5, UI, and chronic diarrhea (Table 2). Considering incident FI occurring monthly or more at 4 years, only ethnicity and depression remained significant risk factors in multivariable analysis in women (data not shown). For men without FI at baseline, the only risk factor for incident FI occurring annually, or monthly FI, was UI.

Table 2.

Multivariable Logistic Regression Analysis Comparing Risk Factors for Incident Fecal Incontinence (FI) in Women and Men

| Variable | Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) for Any FI | |

|---|---|---|

| Women, n =293 | Men, n =259 | |

| African American | 0.5 (0.2–1.0)* | 0.9 (0.5–1.8) |

| Depression symptoms | 3.2 (1.1–9.1)* | 1.2 (0.2–6.1) |

| Urinary incontinence | 2.0 (1.0–3.9)* | 2.3 (1.1–4.7)* |

| Chronic diarrhea | 3.5 (1.0–12.5)* | 0.9 (0.1–1.1) |

Multivariable logistic regression models controlled for age, comorbidity count, and body mass index.

P<.05.

Variables not significantly related to incident FI in men or women were age, BMI, education, rural residence, living alone, comorbidity score, constipation, SPPB score, and MMSE score. In women, no differences were seen according to parity status, hormone therapy usage, or prior hysterectomy. History of prostate disease, prior prostate surgery, and use of alpha adrenergic blocking medications did not differ in the men with and without incident FI.

DISCUSSION

The Fourth International Consultation on Incontinence concluded that more research is needed to define risk factors for FI in longitudinal studies, as well as cross-sectional studies in different age groups.1 Data on incident FI is scarce in community-dwelling adults, with limited data on racial and ethnic differences.1,4 This 4-year, prospective, longitudinal study in community-dwelling older adults reports on incident FI in a unique population balanced in terms of sex and race. A 4-year incidence rate of 17% was found for FI, with 18% of women and 16% of men reporting incident FI. African-American race was a protective factor for women, even after controlling for differences in sociodemographic characteristics and comorbid disease burden. In women and men, UI was a risk factor for incident FI.

Definitions of FI vary considerably in the literature, with no universally accepted definition.1 In addition, most FI definitions are limited to describing the type of leakage as liquid or solid stool, usually excluding staining or flatal incontinence.24 Few epidemiological studies or cohort studies report a specific time frame or frequency of FI episodes in the definition, even with the use of a questionnaire validated for measuring FI.3,4,8–10,25 Of these studies using validated and time-defined measures, the overall prevalence rate of monthly FI ranges from 3% to 15%.2–4,9 In the NHANES study from 2005/06 that used a validated FI questionnaire in a population representative of the U.S. population in terms of age distribution and racial and ethnic diversity, prevalence of FI increased with age, from 2.6% in people aged 20 to 29 to 15.3% in adults aged 70 and older, without sex differences.3

In the UAB Study of Aging, FI was defined as a positive response to the question, “In the past year, have you had any loss of control of your bowels, even a small amount that stains or slightly soils your underwear?” Thus, the FI definition included staining and seepage but not flatal incontinence. The baseline prevalence and 4-year incidence of any FI in the previous year and monthly FI was comparable with those found in other studies.2–4,8,9 Staining and seepage may be more frequent than the loss of liquid or solid stool, but all types of FI are significantly underreported and negatively affect quality of life.26

Independent risk factors for prevalent FI according to sex in the NHANES cohort and another study examining 10-year FI incidence rates are similar to the risk factors reported in this study and included the presence of loose or watery stools or diarrhea and UI.3,10 In the study reporting 10-year FI incidence rates, the incidence rate was 7% (95% CI =5.0–9.6) from a community-dwelling cohort (aged ≥50) using a similar definition for “any” FI. When comparing this study with the current one, the 15-year difference in age at baseline (50 vs 65) and the 11-year difference in average age of the participants at follow-up (67 ± 9 vs 77.7 ± 65.5) may partially explain the lower FI incidence rates (7% vs 17%).10 Although this study was a postal survey, with a lower response rate (44%) than the response rate for an in-home assessment (nearly 80%), the authors found that diarrhea, incomplete bowel evacuation, and pelvic radiation were risk factors for incident FI without controlling for the effect of functional status or chronic comorbidity.10

Older age has been found to be a significant risk factor for FI in the literature.3,4,8 Similar to other studies in older adults,8 age was not a significant risk factor in the current study, probably because of the sample’s limited age range. Having multiple chronic diseases was a risk factor for prevalent FI in women in the NHANES survey and in the cross-sectional data from this cohort but not for incident FI in the current study.3,6 At baseline, a small number of participants had impaired mental status (defined as a MMSE score <24) and limited mobility (based on the SPPB) and may have limited the ability to detect these variables as potential risk factors for incident FI.

Although no differences were seen according to race or ethnicity in the NHANES data, older African-American women were less likely to have incident FI even after controlling for age, rural residence, education, marital status, and comorbidity counts. This finding was also observed in a younger population of postpartum women with sphincter tears16 but contrasts with another study in which older African Americans were more likely to report prevalent FI.8 It is possible that a reporting bias existed among the African-American women in this cohort, resulting in the lower rates of FI seen at 4 years, although no racial or ethnic differences were seen in incident UI or the prevalence of FI at baseline.6,27 More research is needed to explain the racial and ethnic differences that were found in the older African-American women with FI in the current study.

Of the other risk factors evaluated in this study, the presence of UI was the only factor that was significantly related to incident FI in men and women. It is possible that common pathophysiological mechanisms exist that could explain dual UI and FI in older adults. Urination and defecation involve voluntary control of the urinary and external anal sphincters, and toileting is dependent on mobility. Recent magnetic resonance imaging studies of older adults with urge UI show specific patterns of neurological control in the central nervous system, but little information exists for control of defecation in humans.28 Using behavioral strategies similar to those developed for urinary control, behavioral treatments for FI teach targeted skills to control urgency associated with defecation, along with improving voluntary control of the external anal sphincter and improving stool consistency.1 More information and research is needed on the treatment of dual incontinence with behavioral therapies.

In addition to UI and racial and ethnic differences as risk factors for incident FI, depression and chronic diarrhea were also significant risk factors in older women. Depression is often correlated with UI and FI, but the relationship between cause and effect is not known. It is possible that medications that treat depression may have gastrointestinal side effects and affect the presence of FI, although altering neurotransmitter levels of serotonin and norepinephrine may not physiologically predispose patients to FI or UI. Chronic diarrhea and loose stools have been associated with FI prevalence in cross-sectional studies.2,3

Other studies have prospectively evaluated incident FI and risk factors in nursing home residents27 and those surviving a stroke.12 In 234 nursing home residents, one study found that 20% developed FI, but only 7.5% had persistent FI at 10 months.29 Factors associated with persistent FI at 10 months were UI, poor mobility, and impaired cognition but not age and sex.29 A study of 3,850 nursing home residents found a 1-year incidence rate of 15%.11 Risk factors included impairments in ADLs, dementia, the use of trunk restraints, and African-American race, without differences in age or sex. Given the high rates of FI in nursing home residents (up to 50%) and the dependence of incontinent nursing home residents on toileting assistance, risk factors for incident FI in nursing home residents may differ greatly from those of community-based cohorts.30

Scarce data exist for incident FI in community-dwelling cohorts, and less is known about the natural history of FI from prospective cohort data. The current study adds to the literature on incident FI specifically in community-dwelling older adults enrolled in a population-based longitudinal survey.

Although this study was population based, it may have limited generalizability to the entire U.S. population given that it recruited Medicare beneficiaries from only one state in the South. Overall, the small number of participants found to have incident FI in the previous year (n =93) and monthly or more (n =29) limited the power to detect all potentially important risk factors for FI. Another limitation of this study was the high FI remission rate (57%) from a subset of this cohort (n =64). The FI remission rate is comparable with high remission rates also seen for UI in this cohort at 3 years: 39% for women and 55% for men.27 Further research is needed to understand incontinence remission rates in older adults.

CONCLUSIONS

Four-year incidence of FI in community-dwelling older adults was 18% in women and 16% in men. UI was a risk factor for incident FI in women and men, and treatments such as behavioral therapy aimed at improving UI and FI deserve further attention. More information is needed to explore common pathophysiological mechanisms that may predispose older adults to UI and FI.

Acknowledgments

Sponsor’s Role: The sponsors had no active role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collections, analysis, or manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Geriatrics Society, Chicago, Illinois, May 2009.

Author Contributions: Alayne D. Markland: study concept and design, data analysis, interpretation of data, and manuscript preparation. Patricia S. Goode, Kathryn L. Burgio, and Holly E. Richter: study concept and design, interpretation of data, and critical review of the manuscript. David T. Redden: study concept and design, data analysis, interpretation of data, and critical review of the manuscript. Patricia S. Baker and Richard M. Allman: study concept and design, acquisition of subjects and data, interpretation of data, and critical review of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest: Funded by the National Institute on Aging (R01AG15062) to Richard M. Allman; P30AG031054, the Deep South Resource Center for Minority Aging Research Award; and Department of Veterans Affairs Birmingham/Atlanta Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center for salary support for Alayne D. Markland, Patricia S. Goode, Kathryn L. Burgio, and Richard M. Allman. Dr. Markland was funded by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Rehabilitation Research and Development Career Development Award-2.

References

- 1.Norton C, Whitehead WE, Bliss DZ, et al. Conservative and pharmacological management of faecal incontinence in adults. In: Abrams P, Cardozo L, Khoury S, et al., editors. Incontinence. 4. Paris, France: Health Publications, Ltd; 2009. pp. 1321–1386. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bharucha AE, Zinsmeister AR, Locke GR, et al. Prevalence and burden of fecal incontinence: A population-based study in women. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:42–49. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whitehead WE, Borrud L, Goode PS, et al. Fecal incontinence in U.S. adults: Epidemiology and risk factors. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:512–517. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.04.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Macmillan AK, Merrie AEH, Marshall RJ, et al. The prevalence of fecal incontinence in community-dwelling adults: A systematic review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1341–1349. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0593-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nelson R, Norton N, Cautley E, et al. Community-based prevalence of anal incontinence. JAMA. 1995;274:559–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goode PS, Burgio KL, Halli AD, et al. Prevalence and correlates of fecal incontinence in community-dwelling older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:629–635. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Melville JL, Fan MY, Newton K, et al. Fecal incontinence in US women: A population-based study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:2071–2076. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quander CR, Morris MC, Melson J, et al. Prevalence of and factors associated with fecal incontinence in a large community study of older individuals. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:905–909. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.30511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Varma M, Brown J, Creasman J, et al. Reproductive Risks for Incontinence Study at Kaiser Research G. Fecal incontinence in females older than aged 40 years: Who is at risk? Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;46:841–851. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0535-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rey E, Choung RS, Schleck CD, et al. Onset and risk factors for fecal incontinence in a US community. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:412–419. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borello-France D, Burgio KL, Richter HE, et al. Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Fecal and urinary incontinence in primiparous women. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:863–872. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000232504.32589.3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nelson RL, Furner SE. Risk factors for the development of fecal and urinary incontinence in Wisconsin nursing home residents. Maturitas. 2005;52:26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harari D, Coshall C, Rudd AG, et al. New-onset fecal incontinence after stroke: Prevalence, natural history, risk factors, and impact. Stroke. 2003;34:144–150. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000044169.54676.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Landefeld CS, Bowers BJ, Feld AD, et al. National institutes of health state-of-the-science statement: Prevention of fecal and urinary incontinence in adults. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:449–458. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-6-200803180-00210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bharucha AE, Seide BM, Zinsmeister AR, et al. Relation of bowel habits to fecal incontinence in women. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1470. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01792.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nygaard I, Barber MD, Burgio KL, et al. for the Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Prevalence of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in us women. JAMA. 2008;300:1311–1316. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.11.1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burgio KL, Borello-France D, Richter HE, et al. Risk factors for fecal and urinary incontinence after childbirth: The Childbirth and Pelvic Symptoms Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1998–2004. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baker PS, Bodner EV, Allman RM. Measuring life-space mobility in community-dwelling older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:1610–1614. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katz S, Downs TD, Cash HR, et al. Progress in development of the index of ADL. Gerontologist. 1970;10:20–30. doi: 10.1093/geront/10.1_part_1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yesavage J. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1983;17:37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Charlson ME, Pompeii P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: Association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol. 1994;49:M85–M94. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.2.m85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, et al. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1480–1491. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pretlove S, Radley S, Toozs-Hobson P, et al. Prevalence of anal incontinence according to age and gender: A systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Int Urogynecol J. 2006;17:407. doi: 10.1007/s00192-005-0014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whitehead WE. Diagnosing and managing fecal incontinence: If you don’t ask, they won’t tell. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:126. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goode PS, Burgio KL, Redden DT, et al. Population based study of incidence and predictors of urinary incontinence in black and white older adults. J Urol. 2008;179:1449. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.11.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Griffiths DJ, Tadic SD, Schaefer W, et al. Cerebral control of the lower urinary tract: How age-related changes might predispose to urge incontinence. Neuro-Image. 2009;47:981–986. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.04.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chassagne P, Jego A, Gloc P, et al. Does treatment of constipation improve faecal incontinence in institutionalized elderly patients? Age Ageing. 2000;29:159–164. doi: 10.1093/ageing/29.2.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leung FW, Schnelle JF. Urinary and fecal incontinence in nursing home residents. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2008;33:697–707. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]